User login

Hearing a diagnosis of cancer is one of the most significant moments of a patient’s life and informing a patient of her diagnosis is an emotionally and technically challenging task for an obstetrician gynecologist who is frequently on the front line of making this diagnosis. In this column, we will explore some patient-centered strategies to perform this difficult task well so that patients come away informed but with the highest chance for positive emotional adjustment.

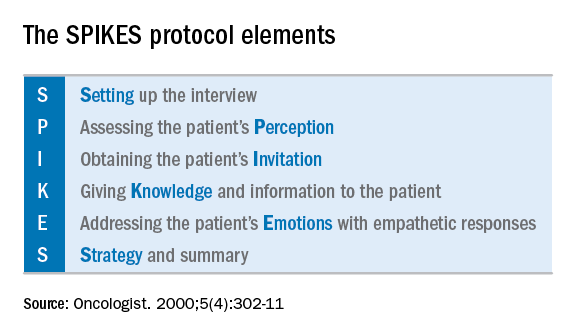

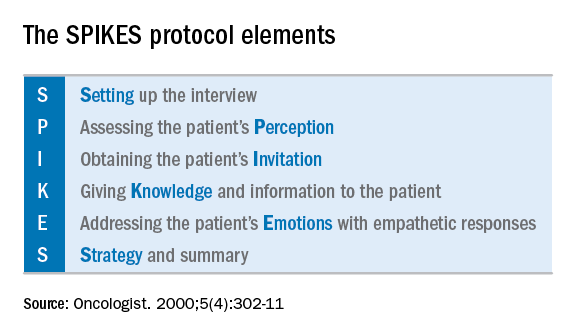

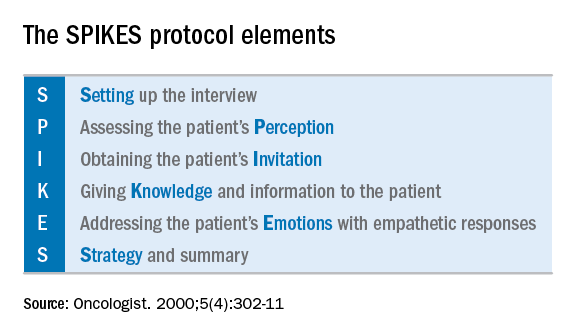

Fewer than 10% of physicians report receiving formal training in techniques of breaking bad news. For the majority of clinicians concerns are centered on being honest and not taking away hope, and in responding to a patient’s emotions.1 The SPIKES approach was developed to arm physicians with strategies to discuss a cancer diagnosis with their patients. This approach includes six key elements to incorporate during the encounter. These strategies are not meant to be formulaic but rather consistent principles that can be adjusted for individual patient needs.

Setting up the discussion

Breaking bad news should not be a one-size-fits-all approach. Age, educational level, culture, religion, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic opportunities each affects what and how patients may want to have this kind of information communicated to them. So how do you know how best to deliver a patient-centered approach for your patient? I recommend this simple strategy: Ask her. When ordering a test or performing a biopsy, let the patient know then why you are ordering the test and inform her of the possibility that the results may show cancer. Ask her how she would like for you to communicate that result. Would she like to be called by phone, the benefit of which is quick dissemination of information? Or would she like to receive the information face to face in the office? Research supports that most patients prefer to learn the result in the office.2 If so, I recommend scheduling a follow-up appointment in advance to prevent delays. Ask her if she would like a family member or a supportive friend to be present for the conveying of results so that she will have time to make these arrangements. Ask her if she would prefer for an alternate person to be provided with the results on her behalf.

When preparing to speak with the patient, it is valuable to mentally rehearse the words that you’ll use. Arrange for privacy and manage time constraints and interruptions (silence pagers and phones, ensure there is adequate time allocated in the schedule). Sit down to deliver the news and make a connection with eye contact and, if appropriate, touch.

Assessing the patient’s perception. Before you tell, ask. For example, “what is your understanding about why we did the biopsy?” This will guide you in where her head and heart are and can ensure you meet her wherever she is.

Obtaining the patient’s invitation. Ask the patient what she would like to be told and how much information. What would she like you to focus on? What does she not want to hear?

Giving knowledge and information to the patient. Especially now, it is important to avoid jargon and use nontechnical terms. However, do not shy away from using specific words like “cancer” by substituting them for more vague and confusing terms such as “malignancy” or “tumor.” It is important to find the balance between expressing information without being overly emotive, while avoiding excessive bluntness. Word choice is critical. Communication styles in the breaking of bad news can be separated broadly into three styles: disease centered, emotion centered, and patient-centered.3 The patient-centered approach is achieved by balancing emotional connection, information sharing, nondominance, and conveying hope. (For example, “I have some disappointing news to share. Shall we talk about the next steps in treatment? I understand this is that this is difficult for you.”) In general, this approach is most valued by patients and is associated with better information recall.

Addressing the patient’s emotions with empathetic responses. It is important that physicians take a moment to pause after communicating the test result. Even if prepared, most patients will still have a moment of shock, and their minds will likely spin through a multitude of thoughts preventing them from being able to “hear” and focus on the subsequent information. This is a moment to reflect on her reactions, her body language, and nonverbal communications to guide you on how to approach the rest of the encounter. Offer her your comfort and condolence in whichever way feels appropriate for you and her.

Beware of your own inclinations to “soften the blow.” It is a natural, compassionate instinct to follow-up giving a bad piece of information by balancing a good piece of information. For example, after just telling a woman that she has endometrial cancer, following with a statement such as “but it’s just stage 1 and is curable with surgery.” While this certainly may have immediate comforting effects, it has a couple of unintended consequences. First, it can result in difficulties later adjusting to a change in diagnosis when more information comes in (for example, upstaging after surgery or imaging). It is better to be honest and tell patients only what you know for sure in these immediate first moments of diagnosis when complete information is lacking. A more general statement such as “for most women, this is found at an early stage and is highly treatable” may be more appropriate and still provide some comfort. Second, attempts to soften the blow with a qualifying statement of positivity, such as “this is a good kind of cancer to have” might be interpreted by some patients as failing to acknowledge their devastation. She may feel that you are minimizing her condition and not allowing her to grieve or be distressed.

Strategy and summary. Patients who leave the encounter with some kind of plan for the future feel less distressed and anxious. The direction at this point of the encounter should be led by the patient. What are her greatest concerns (such as mortality, loss of fertility, time off work for treatment), and what does she want to know right now? Most patients express a desire to know more about treatment or prognosis.2,4 Unfortunately, it often is not possible to furnish this yet, particularly if this falls into the realm of a subspecialist, and prognostication typically requires more information than a provider has at initial diagnosis. However, leaving these questions unanswered is likely to result in a patient feeling helpless. For example, if an ob.gyn. discovers an apparent advanced ovarian cancer on a CT scan, tell her that, despite its apparent advanced case, it is usually treatable and that a gynecologic oncologist will discuss those best treatment options with her. Assure her that you will expeditiously refer her to a specialist who will provide her with those specifics.

The aftermath

That interval between initial diagnosis and specialist consultation is extraordinarily difficult and a high anxiety time. It is not unreasonable, in such cases, to recommend the patient to reputable online information sources, such as the Society of Gynecologic Oncology or American Cancer Society websites so that she and her family can do some research prior to that visit in order to prepare them better and give them a sense of understanding in their disease.

It is a particularly compassionate touch to reach out to the patient in the days following her cancer diagnosis, even if she has moved on to a specialist. Patients often tell me that they felt enormous reassurance and appreciation when their ob.gyn. reached out to them to “check on how they are doing.” This can usually reasonably be done by phone. This second contact serves another critical purpose: it allows for repetition of the diagnosis and initial plan, and the ability to fill in the blanks of what the patient may have missed during the prior visit, if her mind was, naturally, elsewhere. It also, quite simply, shows that you care.

Ultimately, none of us can break bad news perfectly every time. We all need to be insightful with each of these encounters as to what we did well, what we did not, and how we can adjust in the future. With respect to the SPIKES approach, patients report that physicians struggle most with the “perception,” “invitation,” and “strategy and summary” components.5 Our objective should be keeping the patient’s needs in mind, rather than our own, to maximize the chance of doing a good job. If this task is done well, not only are patients more likely to have positive emotional adjustments to their diagnosis but also more adherence with future therapies.4 In the end, it is the patient who has the final say on whether it was done well or not.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reports no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Baile WF et al. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-11.

2. Girgis A et al. Behav Med. 1999 Summer;25(2):69-77.

3. Schmid MM et al. Patient Educ Couns. 2005 Sep;58(3):244-51.

4. Girgis A et al. J Clin Oncol. 1995 Sep;13(9):2449-56.

5. Marscholiek P et al. J Cancer Educ. 2018 Feb 5. doi: 10.1007/s13187-017-1315-3.

Hearing a diagnosis of cancer is one of the most significant moments of a patient’s life and informing a patient of her diagnosis is an emotionally and technically challenging task for an obstetrician gynecologist who is frequently on the front line of making this diagnosis. In this column, we will explore some patient-centered strategies to perform this difficult task well so that patients come away informed but with the highest chance for positive emotional adjustment.

Fewer than 10% of physicians report receiving formal training in techniques of breaking bad news. For the majority of clinicians concerns are centered on being honest and not taking away hope, and in responding to a patient’s emotions.1 The SPIKES approach was developed to arm physicians with strategies to discuss a cancer diagnosis with their patients. This approach includes six key elements to incorporate during the encounter. These strategies are not meant to be formulaic but rather consistent principles that can be adjusted for individual patient needs.

Setting up the discussion

Breaking bad news should not be a one-size-fits-all approach. Age, educational level, culture, religion, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic opportunities each affects what and how patients may want to have this kind of information communicated to them. So how do you know how best to deliver a patient-centered approach for your patient? I recommend this simple strategy: Ask her. When ordering a test or performing a biopsy, let the patient know then why you are ordering the test and inform her of the possibility that the results may show cancer. Ask her how she would like for you to communicate that result. Would she like to be called by phone, the benefit of which is quick dissemination of information? Or would she like to receive the information face to face in the office? Research supports that most patients prefer to learn the result in the office.2 If so, I recommend scheduling a follow-up appointment in advance to prevent delays. Ask her if she would like a family member or a supportive friend to be present for the conveying of results so that she will have time to make these arrangements. Ask her if she would prefer for an alternate person to be provided with the results on her behalf.

When preparing to speak with the patient, it is valuable to mentally rehearse the words that you’ll use. Arrange for privacy and manage time constraints and interruptions (silence pagers and phones, ensure there is adequate time allocated in the schedule). Sit down to deliver the news and make a connection with eye contact and, if appropriate, touch.

Assessing the patient’s perception. Before you tell, ask. For example, “what is your understanding about why we did the biopsy?” This will guide you in where her head and heart are and can ensure you meet her wherever she is.

Obtaining the patient’s invitation. Ask the patient what she would like to be told and how much information. What would she like you to focus on? What does she not want to hear?

Giving knowledge and information to the patient. Especially now, it is important to avoid jargon and use nontechnical terms. However, do not shy away from using specific words like “cancer” by substituting them for more vague and confusing terms such as “malignancy” or “tumor.” It is important to find the balance between expressing information without being overly emotive, while avoiding excessive bluntness. Word choice is critical. Communication styles in the breaking of bad news can be separated broadly into three styles: disease centered, emotion centered, and patient-centered.3 The patient-centered approach is achieved by balancing emotional connection, information sharing, nondominance, and conveying hope. (For example, “I have some disappointing news to share. Shall we talk about the next steps in treatment? I understand this is that this is difficult for you.”) In general, this approach is most valued by patients and is associated with better information recall.

Addressing the patient’s emotions with empathetic responses. It is important that physicians take a moment to pause after communicating the test result. Even if prepared, most patients will still have a moment of shock, and their minds will likely spin through a multitude of thoughts preventing them from being able to “hear” and focus on the subsequent information. This is a moment to reflect on her reactions, her body language, and nonverbal communications to guide you on how to approach the rest of the encounter. Offer her your comfort and condolence in whichever way feels appropriate for you and her.

Beware of your own inclinations to “soften the blow.” It is a natural, compassionate instinct to follow-up giving a bad piece of information by balancing a good piece of information. For example, after just telling a woman that she has endometrial cancer, following with a statement such as “but it’s just stage 1 and is curable with surgery.” While this certainly may have immediate comforting effects, it has a couple of unintended consequences. First, it can result in difficulties later adjusting to a change in diagnosis when more information comes in (for example, upstaging after surgery or imaging). It is better to be honest and tell patients only what you know for sure in these immediate first moments of diagnosis when complete information is lacking. A more general statement such as “for most women, this is found at an early stage and is highly treatable” may be more appropriate and still provide some comfort. Second, attempts to soften the blow with a qualifying statement of positivity, such as “this is a good kind of cancer to have” might be interpreted by some patients as failing to acknowledge their devastation. She may feel that you are minimizing her condition and not allowing her to grieve or be distressed.

Strategy and summary. Patients who leave the encounter with some kind of plan for the future feel less distressed and anxious. The direction at this point of the encounter should be led by the patient. What are her greatest concerns (such as mortality, loss of fertility, time off work for treatment), and what does she want to know right now? Most patients express a desire to know more about treatment or prognosis.2,4 Unfortunately, it often is not possible to furnish this yet, particularly if this falls into the realm of a subspecialist, and prognostication typically requires more information than a provider has at initial diagnosis. However, leaving these questions unanswered is likely to result in a patient feeling helpless. For example, if an ob.gyn. discovers an apparent advanced ovarian cancer on a CT scan, tell her that, despite its apparent advanced case, it is usually treatable and that a gynecologic oncologist will discuss those best treatment options with her. Assure her that you will expeditiously refer her to a specialist who will provide her with those specifics.

The aftermath

That interval between initial diagnosis and specialist consultation is extraordinarily difficult and a high anxiety time. It is not unreasonable, in such cases, to recommend the patient to reputable online information sources, such as the Society of Gynecologic Oncology or American Cancer Society websites so that she and her family can do some research prior to that visit in order to prepare them better and give them a sense of understanding in their disease.

It is a particularly compassionate touch to reach out to the patient in the days following her cancer diagnosis, even if she has moved on to a specialist. Patients often tell me that they felt enormous reassurance and appreciation when their ob.gyn. reached out to them to “check on how they are doing.” This can usually reasonably be done by phone. This second contact serves another critical purpose: it allows for repetition of the diagnosis and initial plan, and the ability to fill in the blanks of what the patient may have missed during the prior visit, if her mind was, naturally, elsewhere. It also, quite simply, shows that you care.

Ultimately, none of us can break bad news perfectly every time. We all need to be insightful with each of these encounters as to what we did well, what we did not, and how we can adjust in the future. With respect to the SPIKES approach, patients report that physicians struggle most with the “perception,” “invitation,” and “strategy and summary” components.5 Our objective should be keeping the patient’s needs in mind, rather than our own, to maximize the chance of doing a good job. If this task is done well, not only are patients more likely to have positive emotional adjustments to their diagnosis but also more adherence with future therapies.4 In the end, it is the patient who has the final say on whether it was done well or not.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reports no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Baile WF et al. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-11.

2. Girgis A et al. Behav Med. 1999 Summer;25(2):69-77.

3. Schmid MM et al. Patient Educ Couns. 2005 Sep;58(3):244-51.

4. Girgis A et al. J Clin Oncol. 1995 Sep;13(9):2449-56.

5. Marscholiek P et al. J Cancer Educ. 2018 Feb 5. doi: 10.1007/s13187-017-1315-3.

Hearing a diagnosis of cancer is one of the most significant moments of a patient’s life and informing a patient of her diagnosis is an emotionally and technically challenging task for an obstetrician gynecologist who is frequently on the front line of making this diagnosis. In this column, we will explore some patient-centered strategies to perform this difficult task well so that patients come away informed but with the highest chance for positive emotional adjustment.

Fewer than 10% of physicians report receiving formal training in techniques of breaking bad news. For the majority of clinicians concerns are centered on being honest and not taking away hope, and in responding to a patient’s emotions.1 The SPIKES approach was developed to arm physicians with strategies to discuss a cancer diagnosis with their patients. This approach includes six key elements to incorporate during the encounter. These strategies are not meant to be formulaic but rather consistent principles that can be adjusted for individual patient needs.

Setting up the discussion

Breaking bad news should not be a one-size-fits-all approach. Age, educational level, culture, religion, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic opportunities each affects what and how patients may want to have this kind of information communicated to them. So how do you know how best to deliver a patient-centered approach for your patient? I recommend this simple strategy: Ask her. When ordering a test or performing a biopsy, let the patient know then why you are ordering the test and inform her of the possibility that the results may show cancer. Ask her how she would like for you to communicate that result. Would she like to be called by phone, the benefit of which is quick dissemination of information? Or would she like to receive the information face to face in the office? Research supports that most patients prefer to learn the result in the office.2 If so, I recommend scheduling a follow-up appointment in advance to prevent delays. Ask her if she would like a family member or a supportive friend to be present for the conveying of results so that she will have time to make these arrangements. Ask her if she would prefer for an alternate person to be provided with the results on her behalf.

When preparing to speak with the patient, it is valuable to mentally rehearse the words that you’ll use. Arrange for privacy and manage time constraints and interruptions (silence pagers and phones, ensure there is adequate time allocated in the schedule). Sit down to deliver the news and make a connection with eye contact and, if appropriate, touch.

Assessing the patient’s perception. Before you tell, ask. For example, “what is your understanding about why we did the biopsy?” This will guide you in where her head and heart are and can ensure you meet her wherever she is.

Obtaining the patient’s invitation. Ask the patient what she would like to be told and how much information. What would she like you to focus on? What does she not want to hear?

Giving knowledge and information to the patient. Especially now, it is important to avoid jargon and use nontechnical terms. However, do not shy away from using specific words like “cancer” by substituting them for more vague and confusing terms such as “malignancy” or “tumor.” It is important to find the balance between expressing information without being overly emotive, while avoiding excessive bluntness. Word choice is critical. Communication styles in the breaking of bad news can be separated broadly into three styles: disease centered, emotion centered, and patient-centered.3 The patient-centered approach is achieved by balancing emotional connection, information sharing, nondominance, and conveying hope. (For example, “I have some disappointing news to share. Shall we talk about the next steps in treatment? I understand this is that this is difficult for you.”) In general, this approach is most valued by patients and is associated with better information recall.

Addressing the patient’s emotions with empathetic responses. It is important that physicians take a moment to pause after communicating the test result. Even if prepared, most patients will still have a moment of shock, and their minds will likely spin through a multitude of thoughts preventing them from being able to “hear” and focus on the subsequent information. This is a moment to reflect on her reactions, her body language, and nonverbal communications to guide you on how to approach the rest of the encounter. Offer her your comfort and condolence in whichever way feels appropriate for you and her.

Beware of your own inclinations to “soften the blow.” It is a natural, compassionate instinct to follow-up giving a bad piece of information by balancing a good piece of information. For example, after just telling a woman that she has endometrial cancer, following with a statement such as “but it’s just stage 1 and is curable with surgery.” While this certainly may have immediate comforting effects, it has a couple of unintended consequences. First, it can result in difficulties later adjusting to a change in diagnosis when more information comes in (for example, upstaging after surgery or imaging). It is better to be honest and tell patients only what you know for sure in these immediate first moments of diagnosis when complete information is lacking. A more general statement such as “for most women, this is found at an early stage and is highly treatable” may be more appropriate and still provide some comfort. Second, attempts to soften the blow with a qualifying statement of positivity, such as “this is a good kind of cancer to have” might be interpreted by some patients as failing to acknowledge their devastation. She may feel that you are minimizing her condition and not allowing her to grieve or be distressed.

Strategy and summary. Patients who leave the encounter with some kind of plan for the future feel less distressed and anxious. The direction at this point of the encounter should be led by the patient. What are her greatest concerns (such as mortality, loss of fertility, time off work for treatment), and what does she want to know right now? Most patients express a desire to know more about treatment or prognosis.2,4 Unfortunately, it often is not possible to furnish this yet, particularly if this falls into the realm of a subspecialist, and prognostication typically requires more information than a provider has at initial diagnosis. However, leaving these questions unanswered is likely to result in a patient feeling helpless. For example, if an ob.gyn. discovers an apparent advanced ovarian cancer on a CT scan, tell her that, despite its apparent advanced case, it is usually treatable and that a gynecologic oncologist will discuss those best treatment options with her. Assure her that you will expeditiously refer her to a specialist who will provide her with those specifics.

The aftermath

That interval between initial diagnosis and specialist consultation is extraordinarily difficult and a high anxiety time. It is not unreasonable, in such cases, to recommend the patient to reputable online information sources, such as the Society of Gynecologic Oncology or American Cancer Society websites so that she and her family can do some research prior to that visit in order to prepare them better and give them a sense of understanding in their disease.

It is a particularly compassionate touch to reach out to the patient in the days following her cancer diagnosis, even if she has moved on to a specialist. Patients often tell me that they felt enormous reassurance and appreciation when their ob.gyn. reached out to them to “check on how they are doing.” This can usually reasonably be done by phone. This second contact serves another critical purpose: it allows for repetition of the diagnosis and initial plan, and the ability to fill in the blanks of what the patient may have missed during the prior visit, if her mind was, naturally, elsewhere. It also, quite simply, shows that you care.

Ultimately, none of us can break bad news perfectly every time. We all need to be insightful with each of these encounters as to what we did well, what we did not, and how we can adjust in the future. With respect to the SPIKES approach, patients report that physicians struggle most with the “perception,” “invitation,” and “strategy and summary” components.5 Our objective should be keeping the patient’s needs in mind, rather than our own, to maximize the chance of doing a good job. If this task is done well, not only are patients more likely to have positive emotional adjustments to their diagnosis but also more adherence with future therapies.4 In the end, it is the patient who has the final say on whether it was done well or not.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reports no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Baile WF et al. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-11.

2. Girgis A et al. Behav Med. 1999 Summer;25(2):69-77.

3. Schmid MM et al. Patient Educ Couns. 2005 Sep;58(3):244-51.

4. Girgis A et al. J Clin Oncol. 1995 Sep;13(9):2449-56.

5. Marscholiek P et al. J Cancer Educ. 2018 Feb 5. doi: 10.1007/s13187-017-1315-3.