User login

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

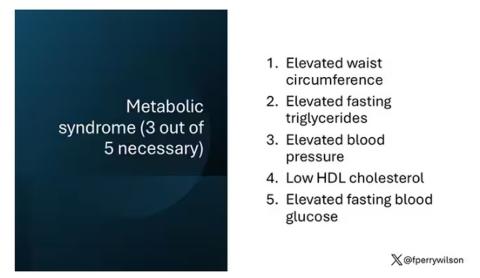

One out of three American adults — about 100 million people in this country — have the metabolic syndrome. I’m showing you the official criteria here, but essentially this is a syndrome of insulin resistance and visceral adiposity that predisposes us to a host of chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and even dementia.

The metabolic syndrome is, fundamentally, a lifestyle disease. There is a direct line between our dietary habits and the wide availability of carbohydrate-rich, highly processed foods, and the rise in the syndrome in the population.

A saying I learned from one of my epidemiology teachers comes to mind: “Lifestyle diseases require lifestyle reinterventions.” But you know what? I’m not so sure anymore.

I’ve been around long enough to see multiple dietary fads come and go with varying efficacy. I grew up in the low-fat era, probably the most detrimental time to our national health as food manufacturers started replacing fats with carbohydrates, driving much of the problem we’re faced with today.

But I was also around for the Atkins diet and the low-carb craze — a healthier approach, all things being equal. And I’ve seen variants of these: the paleo diet (essentially a low-carb, high-protein diet based on minimally processed foods) and the Mediterranean diet, which sought to replace some percentage of fats with healthier fats.

And, of course, there is time-restricted eating.

Time-restricted eating, a variant of intermittent fasting, has the advantage of being very simple. No cookbooks, no recipes. Eat what you want — but limit it to certain hours in the day, ideally a window of less than 10 hours, such as 8 a.m. to 6 p.m.

When it comes to weight loss, the diets that work tend to work because they reduce calorie intake. I know, people will get angry about this, but thermodynamics is not just a good idea, it’s the law.

But weight loss is not the only reason we need to eat healthier. What we eat can impact our health in multiple ways; certain foods lead to more atherosclerosis, more inflammation, increased strain on the kidney and liver, and can affect our glucose homeostasis.

So I was really interested when I saw this article, “Time-Restricted Eating in Adults With Metabolic Syndrome,” appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine October 1, which examined the effect of time-restricted eating on the metabolic syndrome itself. Could this lifestyle intervention cure this lifestyle disease?

In the study, 108 individuals, all of whom had the metabolic syndrome but not full-blown diabetes, were randomized to usual care — basically, nutrition education — vs time-restricted eating. In that group, participants were instructed to reduce their window of eating by at least 4 hours to achieve an 8- to 10-hour eating window. The groups were followed for 3 months.

Now, before we get to the results, it’s important to remember that the success of a lifestyle intervention trial is quite dependent on how well people adhere to the lifestyle intervention. Time-restricted eating is not as easy as taking a pill once a day.

The researchers had participants log their consumption using a smartphone app to confirm whether they were adhering to that restricted eating window.

Broadly speaking, they did. At baseline, both groups had an eating window of about 14 hours a day — think 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. The intervention group reduced that to just under 10 hours, with 10% of days falling outside of the target window.

Lifestyle change achieved, the primary outcome was the change in hemoglobin A1c at 3 months. A1c integrates the serum glucose over time and is thus a good indicator of the success of the intervention in terms of insulin resistance. But the effect was, honestly, disappointing.

Technically, the time-restricted-eating group had a greater A1c change than the control group — by 0.1 percentage points. On average, they went from a baseline A1c of 5.87 to a 3-month A1c of 5.75.

Other metabolic syndrome markers were equally lackluster: no difference in fasting glucose, mean glucose, or fasting insulin.

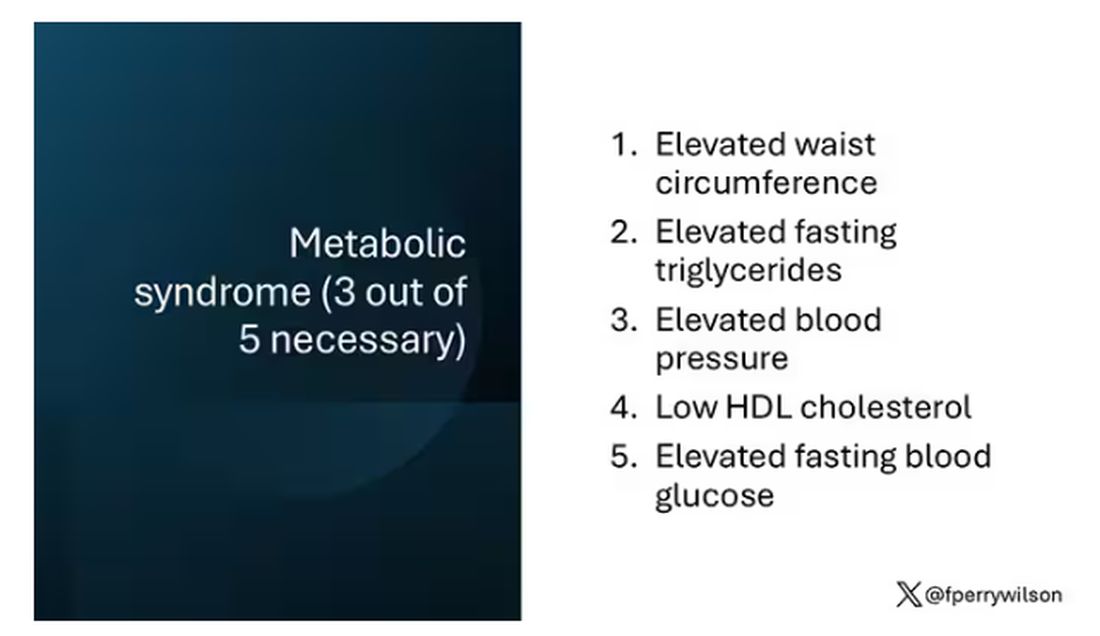

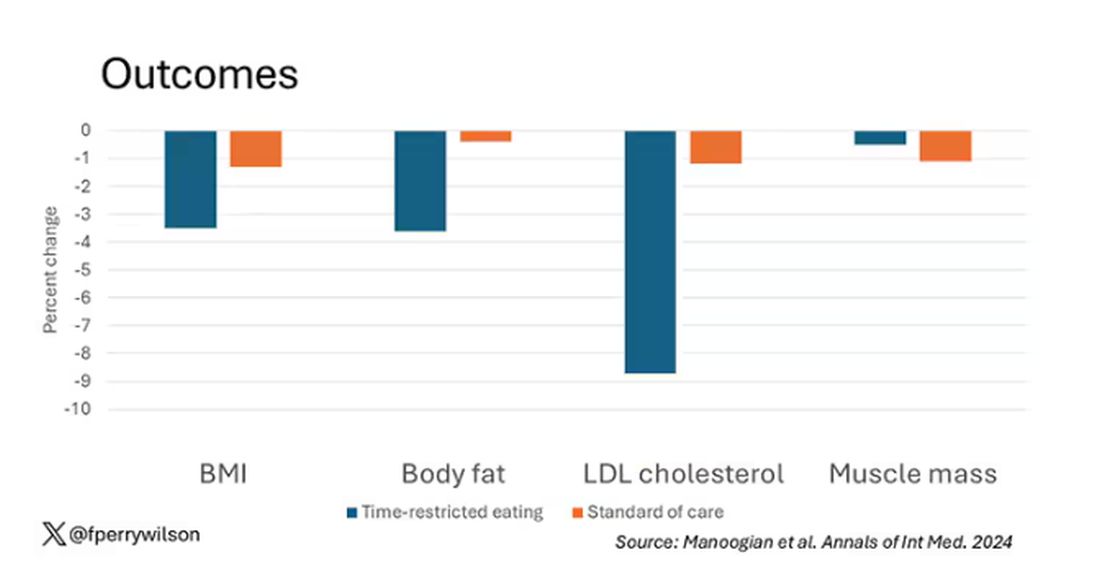

There was some weight change. The control group, which got that dietary education, lost 1.5% of body weight over the 3 months. The time-restricted-eating group lost 3.3% — about 7 pounds, which is reasonable.

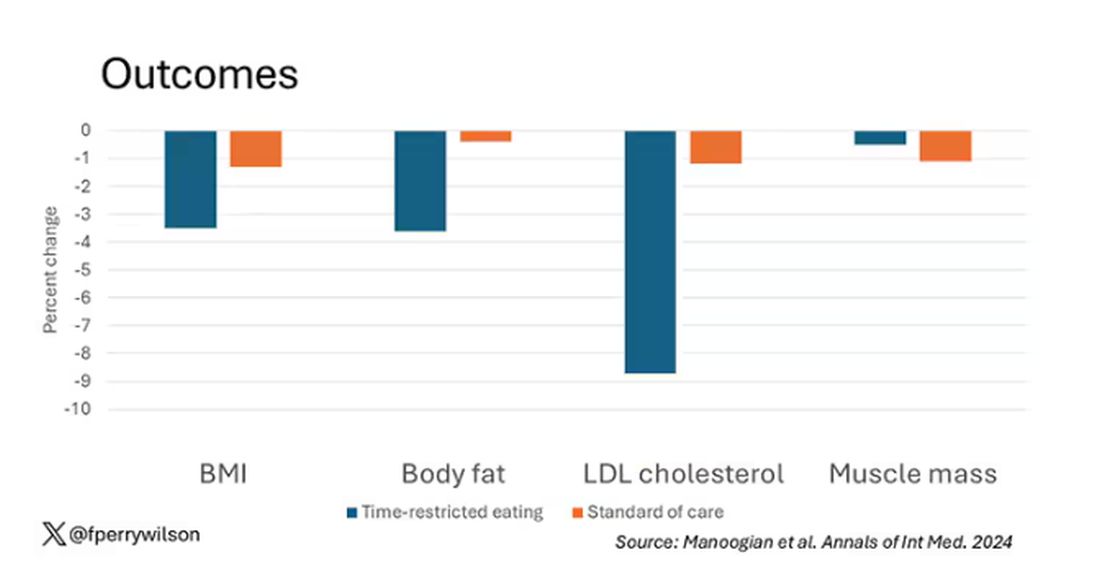

With that weight loss came statistically significant, albeit modest improvements in BMI, body fat percentage, and LDL cholesterol.

Of interest, despite the larger weight loss in the intermittent-fasting group, there was no difference in muscle mass loss, which is encouraging.

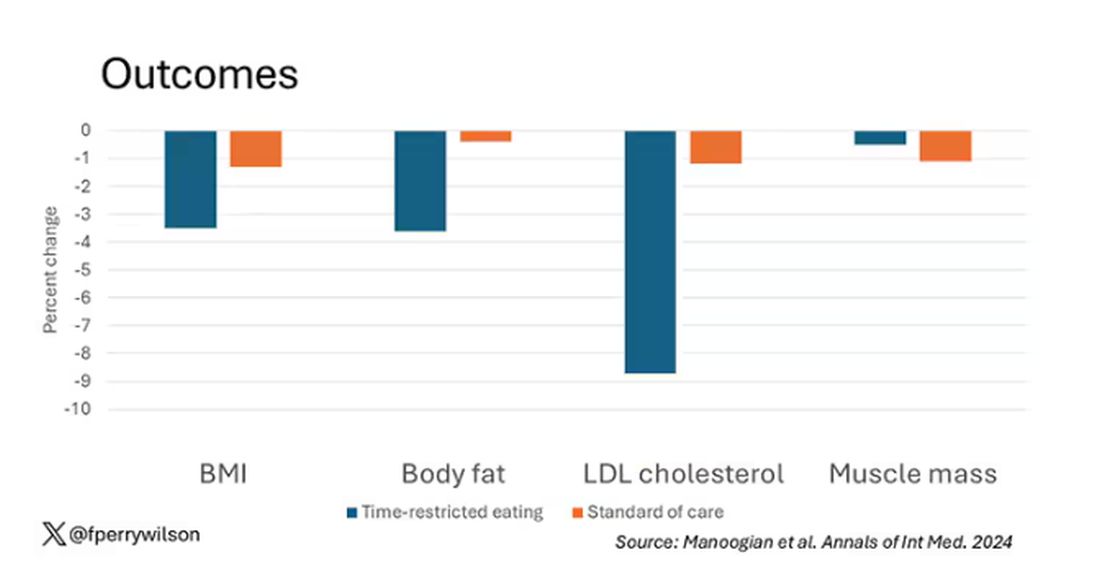

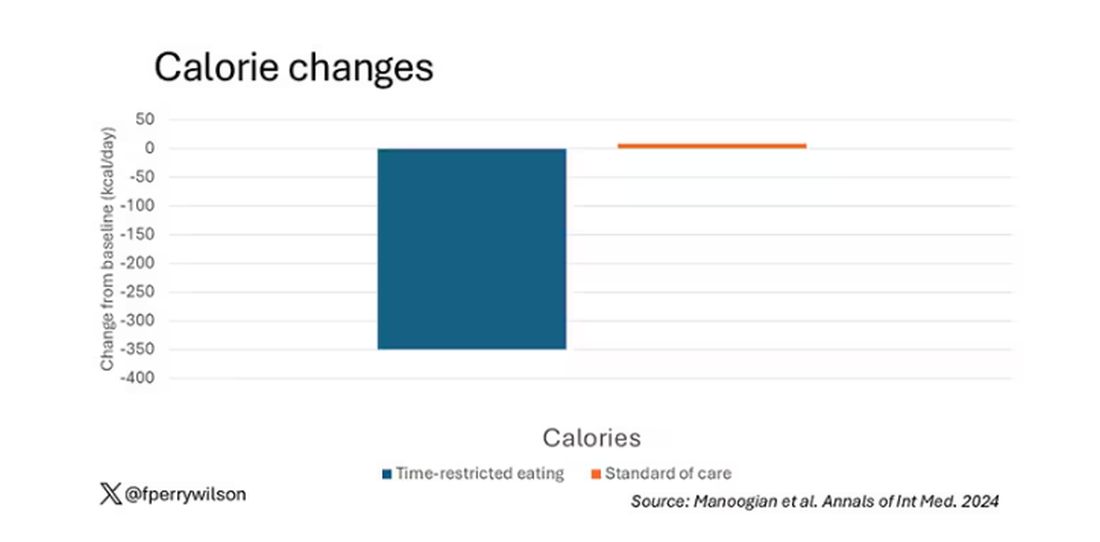

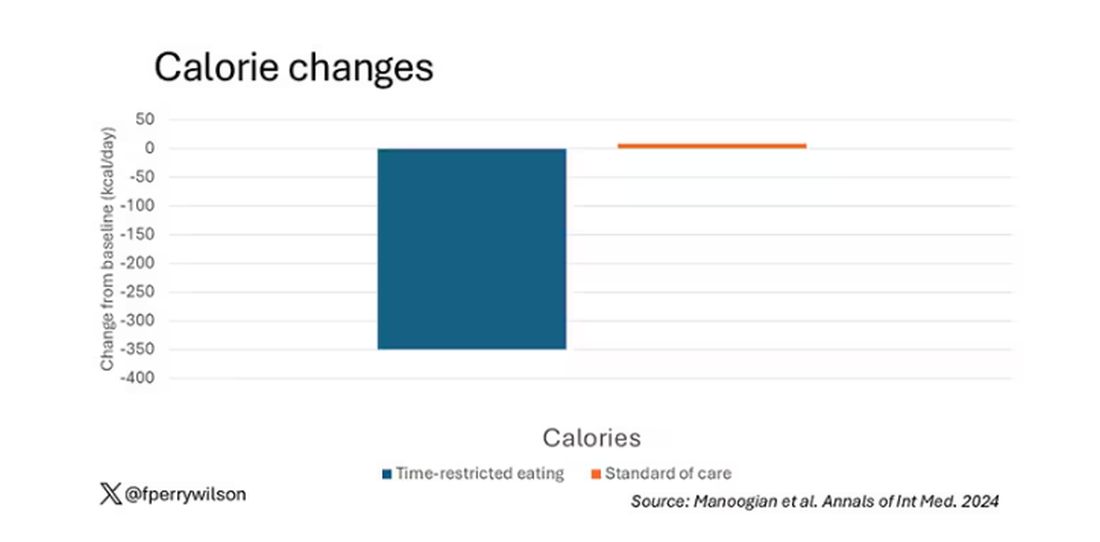

Taken together, we can say that, yes, it seems like time-restricted eating can help people lose some weight. This is essentially due to the fact that people eat fewer calories when they do time-restricted eating, as you can see here.

But, in the end, this trial examined whether this relatively straightforward lifestyle intervention would move the needle in terms of metabolic syndrome, and the data are not very compelling for that.

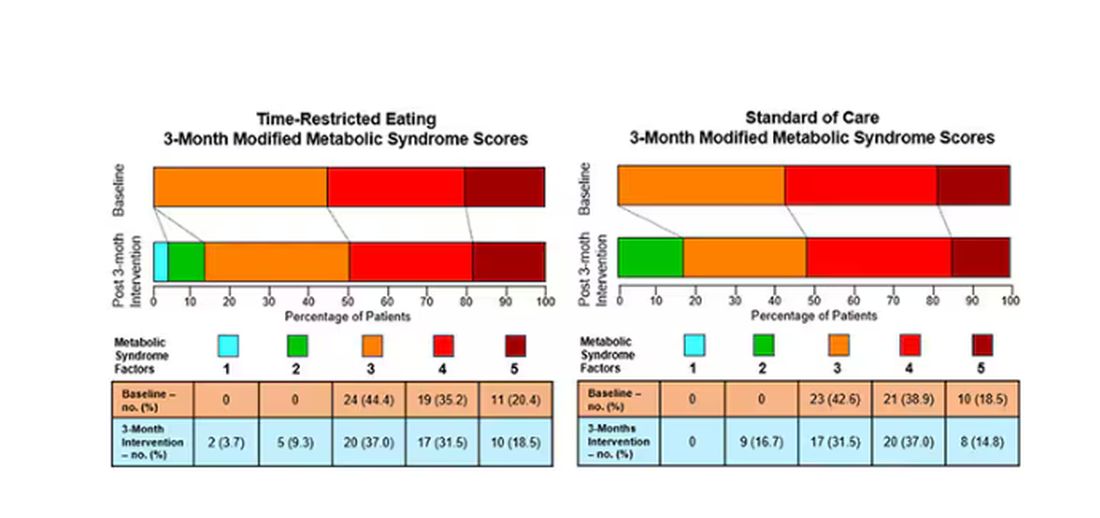

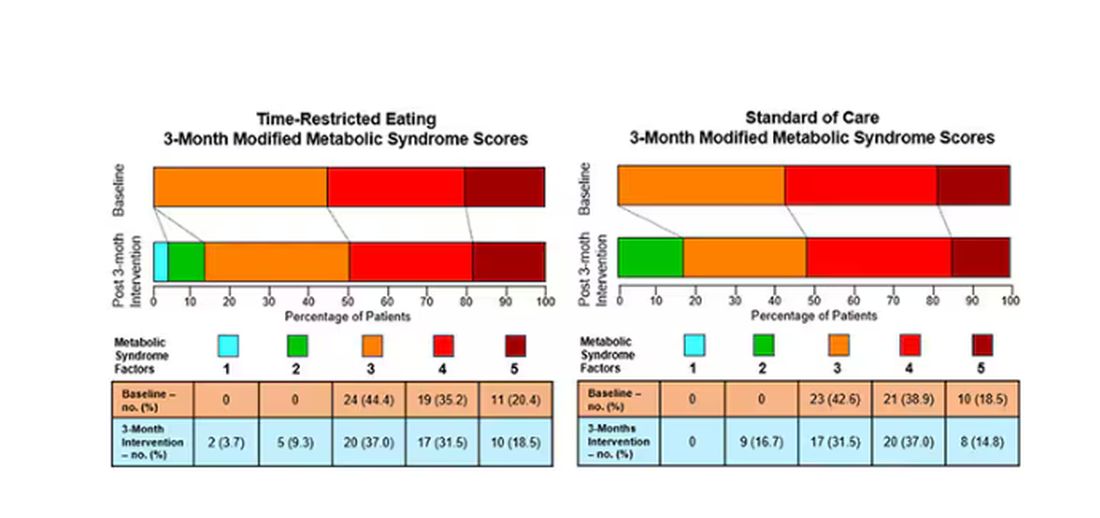

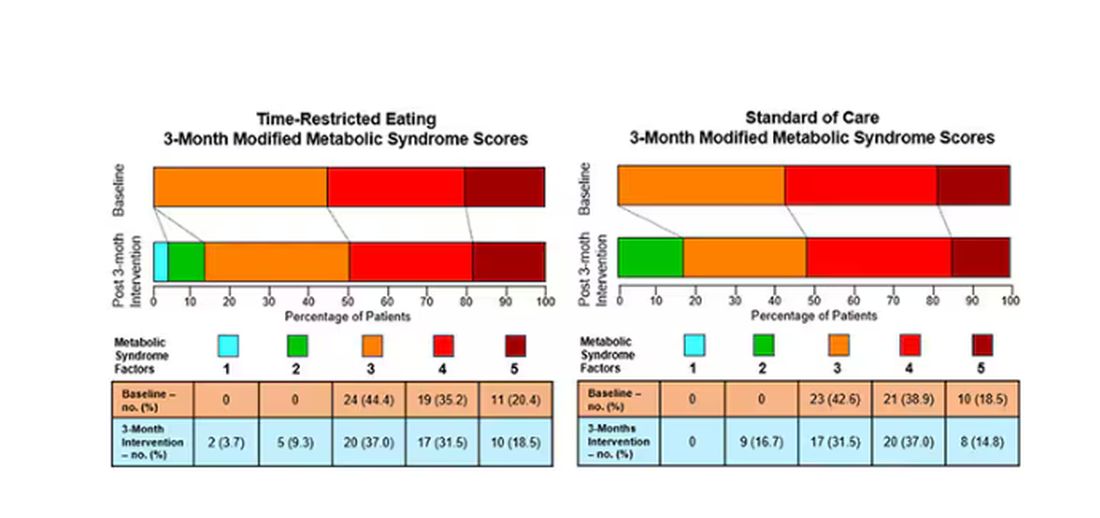

This graph shows how many of those five factors for metabolic syndrome the individuals in this trial had from the start to the end. You see that, over the 3 months, seven people in the time-restricted-eating group moved from having three criteria to two or one — being “cured” of metabolic syndrome, if you will. Nine people in the standard group were cured by that definition. Remember, they had to have at least three to have the syndrome and thus be eligible for the trial.

So If it just leads to weight loss by forcing people to consume less calories, then we need to acknowledge that we probably have better methods to achieve this same end. Ten years ago, I would have said that lifestyle change is the only way to end the epidemic of the metabolic syndrome in this country. Today, well, we live in a world of GLP-1 weight loss drugs. It is simply a different world now. Yes, they are expensive. Yes, they have side effects. But we need to evaluate them against the comparison. And so far, lifestyle changes alone are really no comparison.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

One out of three American adults — about 100 million people in this country — have the metabolic syndrome. I’m showing you the official criteria here, but essentially this is a syndrome of insulin resistance and visceral adiposity that predisposes us to a host of chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and even dementia.

The metabolic syndrome is, fundamentally, a lifestyle disease. There is a direct line between our dietary habits and the wide availability of carbohydrate-rich, highly processed foods, and the rise in the syndrome in the population.

A saying I learned from one of my epidemiology teachers comes to mind: “Lifestyle diseases require lifestyle reinterventions.” But you know what? I’m not so sure anymore.

I’ve been around long enough to see multiple dietary fads come and go with varying efficacy. I grew up in the low-fat era, probably the most detrimental time to our national health as food manufacturers started replacing fats with carbohydrates, driving much of the problem we’re faced with today.

But I was also around for the Atkins diet and the low-carb craze — a healthier approach, all things being equal. And I’ve seen variants of these: the paleo diet (essentially a low-carb, high-protein diet based on minimally processed foods) and the Mediterranean diet, which sought to replace some percentage of fats with healthier fats.

And, of course, there is time-restricted eating.

Time-restricted eating, a variant of intermittent fasting, has the advantage of being very simple. No cookbooks, no recipes. Eat what you want — but limit it to certain hours in the day, ideally a window of less than 10 hours, such as 8 a.m. to 6 p.m.

When it comes to weight loss, the diets that work tend to work because they reduce calorie intake. I know, people will get angry about this, but thermodynamics is not just a good idea, it’s the law.

But weight loss is not the only reason we need to eat healthier. What we eat can impact our health in multiple ways; certain foods lead to more atherosclerosis, more inflammation, increased strain on the kidney and liver, and can affect our glucose homeostasis.

So I was really interested when I saw this article, “Time-Restricted Eating in Adults With Metabolic Syndrome,” appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine October 1, which examined the effect of time-restricted eating on the metabolic syndrome itself. Could this lifestyle intervention cure this lifestyle disease?

In the study, 108 individuals, all of whom had the metabolic syndrome but not full-blown diabetes, were randomized to usual care — basically, nutrition education — vs time-restricted eating. In that group, participants were instructed to reduce their window of eating by at least 4 hours to achieve an 8- to 10-hour eating window. The groups were followed for 3 months.

Now, before we get to the results, it’s important to remember that the success of a lifestyle intervention trial is quite dependent on how well people adhere to the lifestyle intervention. Time-restricted eating is not as easy as taking a pill once a day.

The researchers had participants log their consumption using a smartphone app to confirm whether they were adhering to that restricted eating window.

Broadly speaking, they did. At baseline, both groups had an eating window of about 14 hours a day — think 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. The intervention group reduced that to just under 10 hours, with 10% of days falling outside of the target window.

Lifestyle change achieved, the primary outcome was the change in hemoglobin A1c at 3 months. A1c integrates the serum glucose over time and is thus a good indicator of the success of the intervention in terms of insulin resistance. But the effect was, honestly, disappointing.

Technically, the time-restricted-eating group had a greater A1c change than the control group — by 0.1 percentage points. On average, they went from a baseline A1c of 5.87 to a 3-month A1c of 5.75.

Other metabolic syndrome markers were equally lackluster: no difference in fasting glucose, mean glucose, or fasting insulin.

There was some weight change. The control group, which got that dietary education, lost 1.5% of body weight over the 3 months. The time-restricted-eating group lost 3.3% — about 7 pounds, which is reasonable.

With that weight loss came statistically significant, albeit modest improvements in BMI, body fat percentage, and LDL cholesterol.

Of interest, despite the larger weight loss in the intermittent-fasting group, there was no difference in muscle mass loss, which is encouraging.

Taken together, we can say that, yes, it seems like time-restricted eating can help people lose some weight. This is essentially due to the fact that people eat fewer calories when they do time-restricted eating, as you can see here.

But, in the end, this trial examined whether this relatively straightforward lifestyle intervention would move the needle in terms of metabolic syndrome, and the data are not very compelling for that.

This graph shows how many of those five factors for metabolic syndrome the individuals in this trial had from the start to the end. You see that, over the 3 months, seven people in the time-restricted-eating group moved from having three criteria to two or one — being “cured” of metabolic syndrome, if you will. Nine people in the standard group were cured by that definition. Remember, they had to have at least three to have the syndrome and thus be eligible for the trial.

So If it just leads to weight loss by forcing people to consume less calories, then we need to acknowledge that we probably have better methods to achieve this same end. Ten years ago, I would have said that lifestyle change is the only way to end the epidemic of the metabolic syndrome in this country. Today, well, we live in a world of GLP-1 weight loss drugs. It is simply a different world now. Yes, they are expensive. Yes, they have side effects. But we need to evaluate them against the comparison. And so far, lifestyle changes alone are really no comparison.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

One out of three American adults — about 100 million people in this country — have the metabolic syndrome. I’m showing you the official criteria here, but essentially this is a syndrome of insulin resistance and visceral adiposity that predisposes us to a host of chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and even dementia.

The metabolic syndrome is, fundamentally, a lifestyle disease. There is a direct line between our dietary habits and the wide availability of carbohydrate-rich, highly processed foods, and the rise in the syndrome in the population.

A saying I learned from one of my epidemiology teachers comes to mind: “Lifestyle diseases require lifestyle reinterventions.” But you know what? I’m not so sure anymore.

I’ve been around long enough to see multiple dietary fads come and go with varying efficacy. I grew up in the low-fat era, probably the most detrimental time to our national health as food manufacturers started replacing fats with carbohydrates, driving much of the problem we’re faced with today.

But I was also around for the Atkins diet and the low-carb craze — a healthier approach, all things being equal. And I’ve seen variants of these: the paleo diet (essentially a low-carb, high-protein diet based on minimally processed foods) and the Mediterranean diet, which sought to replace some percentage of fats with healthier fats.

And, of course, there is time-restricted eating.

Time-restricted eating, a variant of intermittent fasting, has the advantage of being very simple. No cookbooks, no recipes. Eat what you want — but limit it to certain hours in the day, ideally a window of less than 10 hours, such as 8 a.m. to 6 p.m.

When it comes to weight loss, the diets that work tend to work because they reduce calorie intake. I know, people will get angry about this, but thermodynamics is not just a good idea, it’s the law.

But weight loss is not the only reason we need to eat healthier. What we eat can impact our health in multiple ways; certain foods lead to more atherosclerosis, more inflammation, increased strain on the kidney and liver, and can affect our glucose homeostasis.

So I was really interested when I saw this article, “Time-Restricted Eating in Adults With Metabolic Syndrome,” appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine October 1, which examined the effect of time-restricted eating on the metabolic syndrome itself. Could this lifestyle intervention cure this lifestyle disease?

In the study, 108 individuals, all of whom had the metabolic syndrome but not full-blown diabetes, were randomized to usual care — basically, nutrition education — vs time-restricted eating. In that group, participants were instructed to reduce their window of eating by at least 4 hours to achieve an 8- to 10-hour eating window. The groups were followed for 3 months.

Now, before we get to the results, it’s important to remember that the success of a lifestyle intervention trial is quite dependent on how well people adhere to the lifestyle intervention. Time-restricted eating is not as easy as taking a pill once a day.

The researchers had participants log their consumption using a smartphone app to confirm whether they were adhering to that restricted eating window.

Broadly speaking, they did. At baseline, both groups had an eating window of about 14 hours a day — think 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. The intervention group reduced that to just under 10 hours, with 10% of days falling outside of the target window.

Lifestyle change achieved, the primary outcome was the change in hemoglobin A1c at 3 months. A1c integrates the serum glucose over time and is thus a good indicator of the success of the intervention in terms of insulin resistance. But the effect was, honestly, disappointing.

Technically, the time-restricted-eating group had a greater A1c change than the control group — by 0.1 percentage points. On average, they went from a baseline A1c of 5.87 to a 3-month A1c of 5.75.

Other metabolic syndrome markers were equally lackluster: no difference in fasting glucose, mean glucose, or fasting insulin.

There was some weight change. The control group, which got that dietary education, lost 1.5% of body weight over the 3 months. The time-restricted-eating group lost 3.3% — about 7 pounds, which is reasonable.

With that weight loss came statistically significant, albeit modest improvements in BMI, body fat percentage, and LDL cholesterol.

Of interest, despite the larger weight loss in the intermittent-fasting group, there was no difference in muscle mass loss, which is encouraging.

Taken together, we can say that, yes, it seems like time-restricted eating can help people lose some weight. This is essentially due to the fact that people eat fewer calories when they do time-restricted eating, as you can see here.

But, in the end, this trial examined whether this relatively straightforward lifestyle intervention would move the needle in terms of metabolic syndrome, and the data are not very compelling for that.

This graph shows how many of those five factors for metabolic syndrome the individuals in this trial had from the start to the end. You see that, over the 3 months, seven people in the time-restricted-eating group moved from having three criteria to two or one — being “cured” of metabolic syndrome, if you will. Nine people in the standard group were cured by that definition. Remember, they had to have at least three to have the syndrome and thus be eligible for the trial.

So If it just leads to weight loss by forcing people to consume less calories, then we need to acknowledge that we probably have better methods to achieve this same end. Ten years ago, I would have said that lifestyle change is the only way to end the epidemic of the metabolic syndrome in this country. Today, well, we live in a world of GLP-1 weight loss drugs. It is simply a different world now. Yes, they are expensive. Yes, they have side effects. But we need to evaluate them against the comparison. And so far, lifestyle changes alone are really no comparison.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.