User login

The rate of inpatient admissions among adults aged 65 years and older has decreased by approximately 25% since 2000.1,2 This long-term trend raises important questions about inpatient-related spending in the traditional Medicare program for hospitals and providers who treat beneficiaries after a hospitalization. As traditional Medicare’s most expensive sector (accounting for 21% of all Medicare spending3), reducing hospitalizations is often championed as an opportunity to moderate Medicare spending growth.

Medicare’s ability to achieve significant savings from declining inpatient use may be tempered by a shift toward more expensive hospitalizations. If marginal hospitalizations among healthier beneficiaries are avoided, then the remaining inpatient users may be sicker and have greater spending per hospitalization and greater need for follow-up services. This study examines trends in Medicare spending related to episodes initiated by an inpatient stay because of its importance to overall Medicare spending and the implications for several Medicare value-based payment initiatives. In care models seeking to contain spending at a population level, such as accountable care organizations and managed care plans, reducing inpatient use and associated services may have the largest impact in curbing overall spending growth per beneficiary. Other models focused on spending at an episode level, including bundled payment initiatives, may face challenges if inpatient episodes become more expensive over time.

As Medicare shifts toward value-based payments, hospitalists and other hospital leaders are often involved in redesigning care delivery models for the hospital or accountable care organization (eg, through readmission reduction initiatives, post–acute care coordination, and bundled-care delivery programs). Not all savings strategies rely on providers to change how services are delivered; Medicare can modify payment rates, such as Affordable Care Act provisions that slowed how quickly Medicare payment rates increased.4 For clinicians to navigate the shift toward new payment models, it is important to recognize how each of these elements—declining hospital admissions, spending per inpatient episode, and payment rates—affect spending trends for inpatient services and associated care. Previous articles on overall Medicare inpatient spending have examined inpatient stays alone5 or focused mainly on spending per episode6,7 without quantifying how these elements contributed to overall episode-related Medicare spending per beneficiary. This article addresses this gap by demonstrating how inpatient-related spending trends reflect each component.

This study examined trends in Medicare’s spending on inpatient episodes during the years 2009 to 2017. We described changes in the volume and spending on inpatient-initiated episodes across several dimensions, including beneficiary-level and hospitalization-level factors. We examined whether declines in spending associated with fewer inpatient-initiated episodes have been offset by increased spending per episode and how spending would have differed without changes in Medicare payment rates.

Episode Definition

We constructed an episode measure that captured traditional Medicare spending for 30 days prior to hospital admission, hospitalization duration, and 90 days following hospital discharge (additional details in the Appendix).

Any acute hospitalization triggered a new episode, with one exception: if a beneficiary was discharged and readmitted within 90 days for the same diagnosis-related group (DRG), then the readmission did not trigger a new episode. The spending for that readmission was attributed to the prior hospital stay. In effect, the annual number of episodes is equivalent to the annual number of hospital admissions minus subsequent rehospitalizations for the same DRG. Neither observation stays nor hospitalizations in inpatient rehabilitation, psychiatric, or long-term facilities were considered acute hospital admissions.

We assigned claims from noninpatient sectors to an episode based on whether the claim start date fell within the episode window. All traditional Medicare sectors were measured, including outpatient services, physician claims, post–acute care services, and Medicare Part D prescription drug events.

Our analysis aimed to measure all spending related to inpatient episodes without double-counting spending for overlapping episodes. If episodes overlapped, then spending for overlapping days was weighted to be evenly divided across episodes.

Outcome Measures

The study’s main outcomes summarized episode trends across the entire traditional Medicare population, including beneficiaries without an episode, in annual mean number of episodes per beneficiary and annual mean episode-related spending per beneficiary. The denominator of these measures is person-years, or total number of beneficiary months with Medicare Part A and B coverage divided by 12. The annual mean number of episodes per beneficiary is the total number of episodes initiated in a calendar year divided by person-years. The annual mean episode-related spending per beneficiary is the total amount of spending attributed to episodes divided by person-years. We also measured annual mean spending per episode, or total amount of spending attributed to episodes divided by the total number of episodes.

Medicare annually updates each sector’s payment rates for several factors, including inflation. We constructed an index for each sector to adjust for these annual payment rate changes. We also accounted for sequestration measures in effect since April 2013 that reduced Medicare payments to all sectors by 2%. We report our spending measures twice, with and without adjusting for changes in payment rates. Adjusted numbers reflect payment rates in effect in 2015.

Analysis Approach

We present annual trends on changes in the number of inpatient episodes per beneficiary, mean episode-related spending per beneficiary, and mean spending per episode. To quantify how changes in episode-related spending per beneficiary reflect changes in the number of episodes per beneficiary vs changes in spending per episode, we modified an approach implemented by Rosen and colleagues.8

To better understand which beneficiaries have declining inpatient use, we performed stratified analyses describing changes in the number of episodes per beneficiary between 2009 and 2017, spending per episode, and total episode-related spending per beneficiary. We report these measures for several subpopulations defined by age, sex, race, dual-eligible status, and whether the beneficiary used long-term nursing home services during the episode’s calendar year. Descriptive statistics also detail how these measures changed between 2009 and 2017 for episodes stratified by characteristics of the index hospital stay: planned vs unplanned, medical vs surgical, and any use of intensive care unit (ICU) or coronary care unit services. We also stratify study measures by whether an episode included any use of post–acute care services (skilled nursing facility, home health, or inpatient rehabilitation facility use). Finally, we aggregate the episodes into major diagnostic categories (MDCs) based on the index hospital stay’s DRG to report study outcomes by condition. Because of a shift in coding hospitalizations for pneumonia as sepsis,9,10 we exclude these two diseases from their respective MDCs and analyze them jointly as a unique category.

RESULTS

Changes in Number of Inpatient Episodes and Related Spending

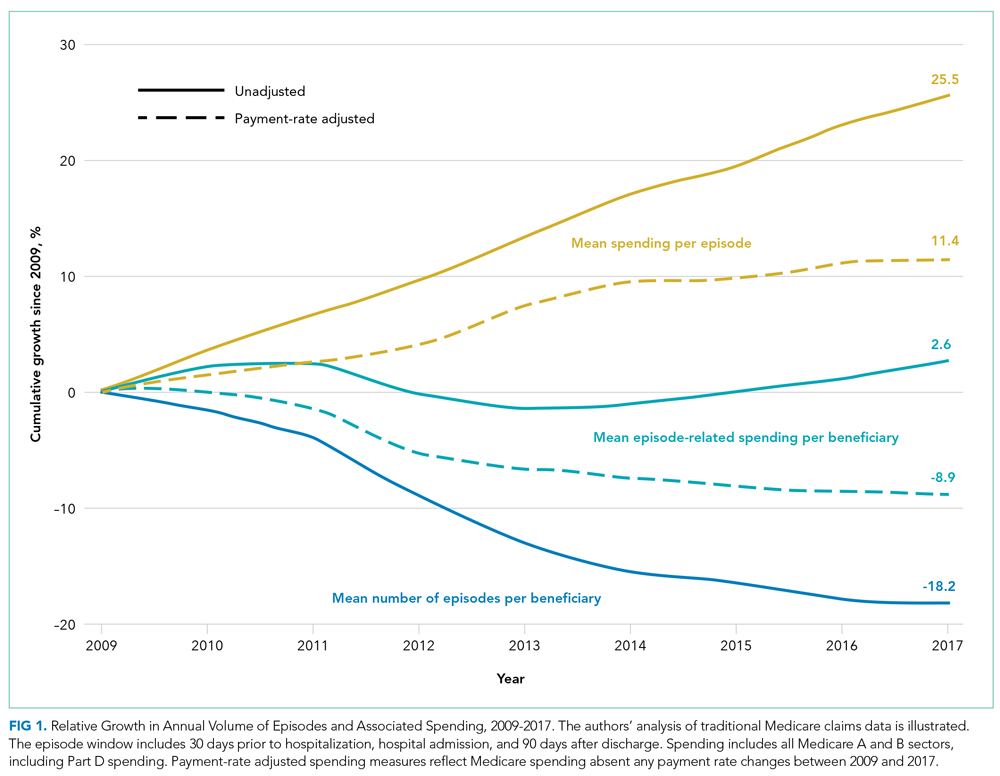

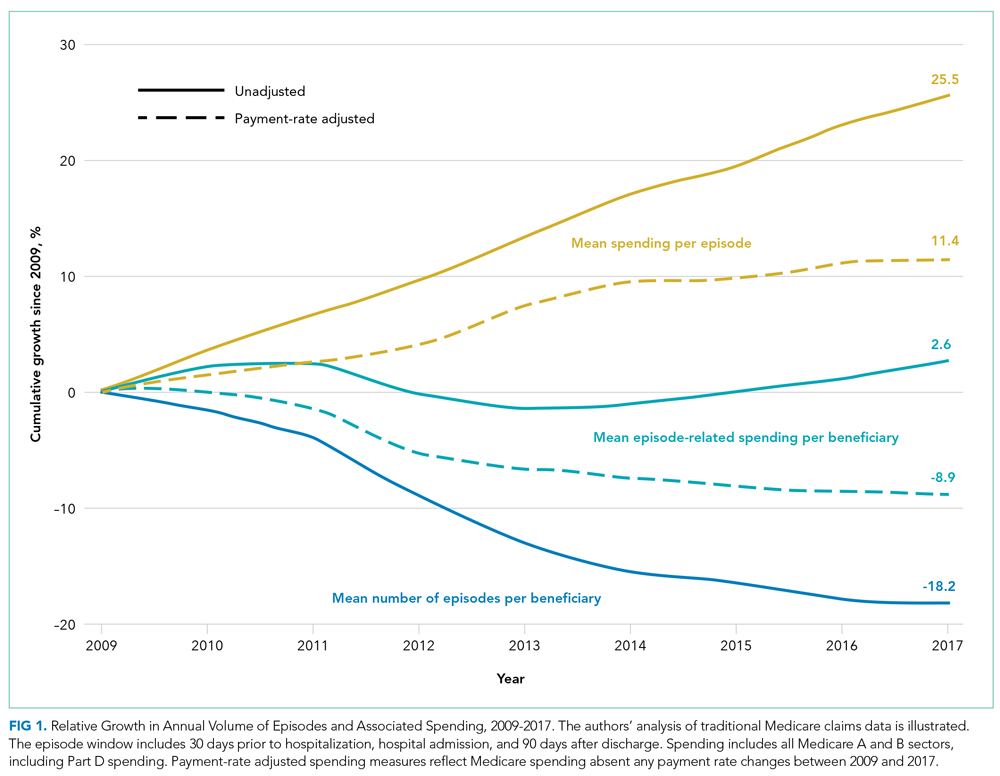

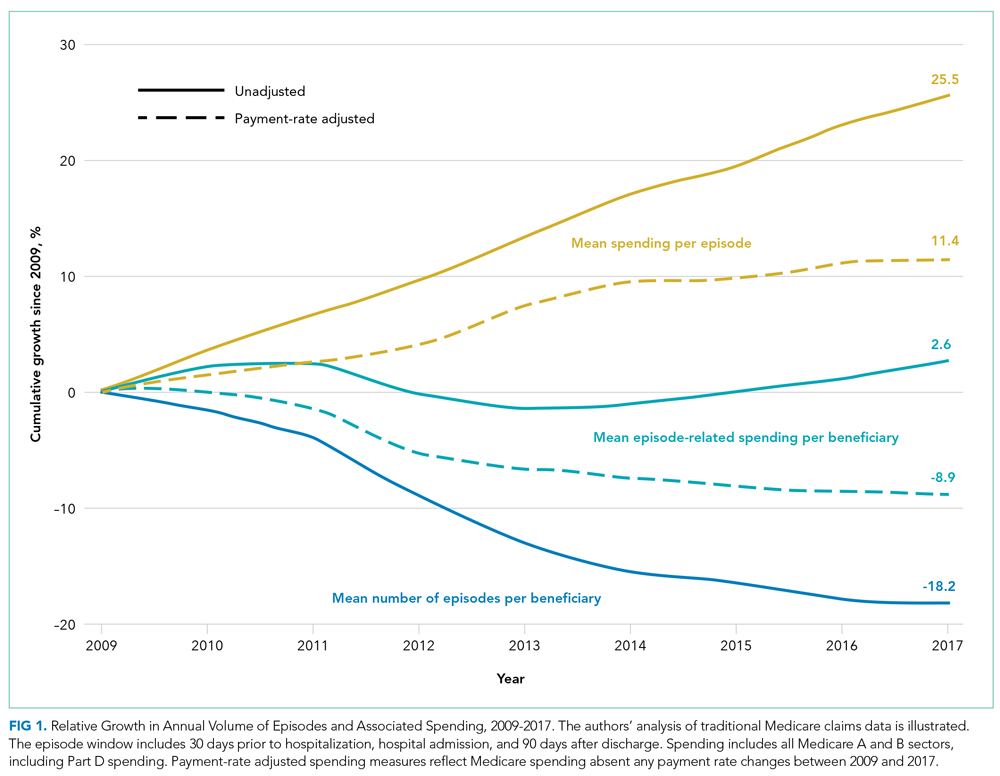

From 2009 to 2017, the number of inpatient episodes per 1000 traditional Medicare beneficiaries declined from 326 to 267 (Table 1), or a relative decline of 18.2% (Figure 1). The total volume of inpatient episodes declined by only 13.4%, from 10.2 million to 8.8 million, reflecting that the size of the traditional Medicare population grew during these years. Over the same years, mean payment-rate–adjusted spending per episode increased 11.4% from $20,891 to $23,273.

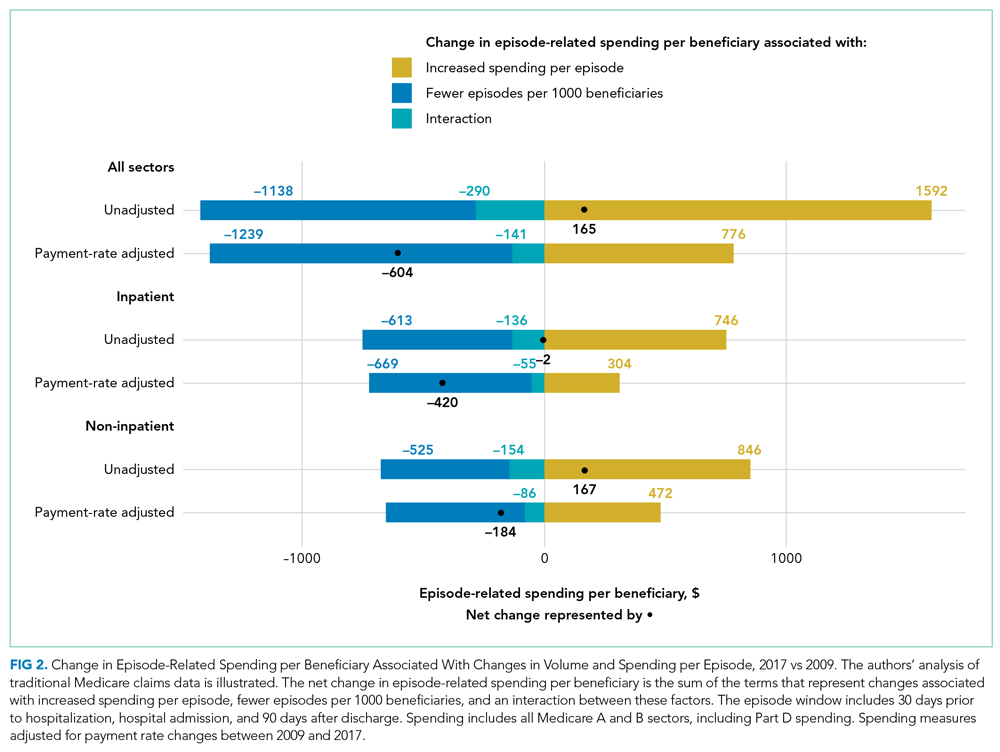

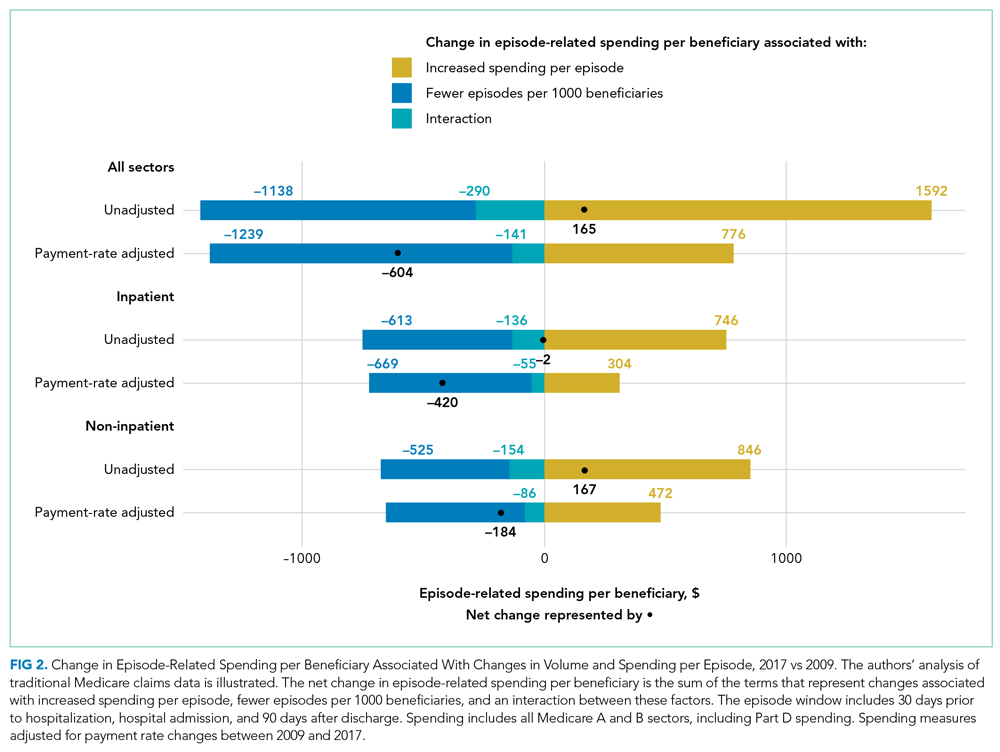

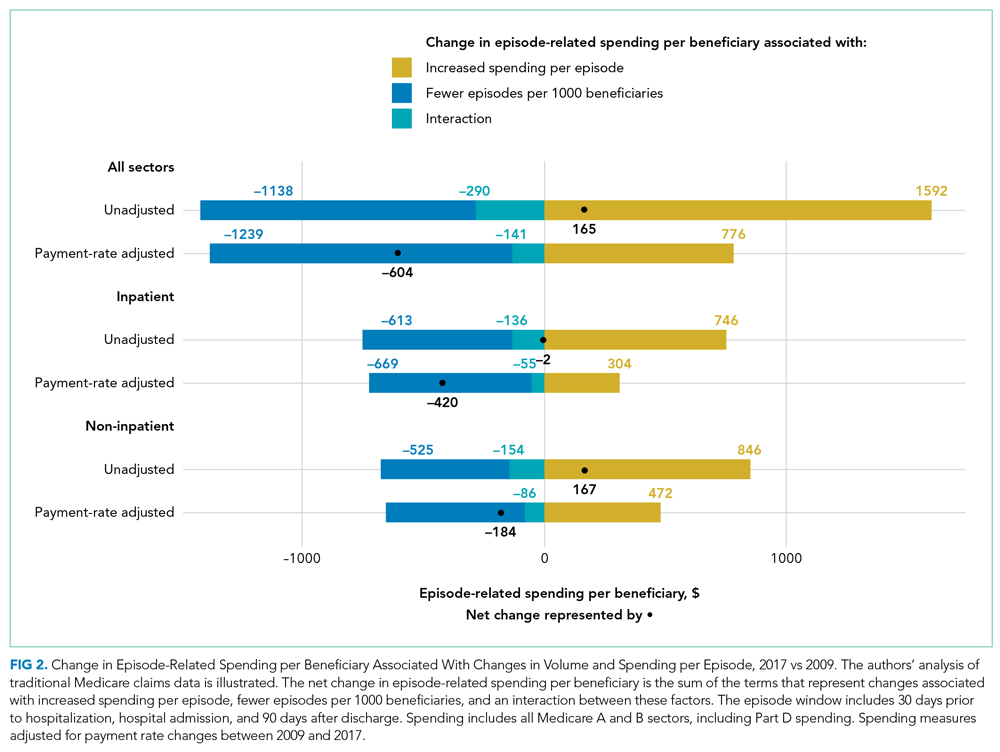

When considering overall episode-related spending, the large decline in the volume of episodes outweighed increased spending per episode: the mean amount of episode-related Medicare spending per beneficiary decreased 8.9% from $6810 to $6206 (Table 1), or a net change of $604 (Figure 2). This net change reflects decreased spending due to fewer episodes per beneficiary ($1239 reduction in episode-related spending) offset by increased spending per episode (translating to a $776 increase in episode-related spending per beneficiary).

When these estimates are calculated separately for the inpatient sector and all other sectors, the inpatient sector experienced small increases in spending associated with greater spending per episode ($304) compared with noninpatient sectors ($472). Accordingly, the inpatient sector had a larger net decline in episode-related spending per beneficiary ($420) than noninpatient sectors ($184) after taking into account declining episode volume.

As expected, episode-related spending increased more when measures were not adjusted for annual payment rate increases. Without such adjustment, mean spending per episode increased 25.5%, and episode-related spending per beneficiary was nearly flat (2.6% between 2009 and 2017 [Figure 1]). The decline in unadjusted spending associated with fewer episodes ($1138) was offset by the spending increase associated with higher spending per episode ($1592) (Figure 2).

Analyses Stratified by Beneficiary Characteristics

Every population examined had declines in the number of inpatient episodes, even beneficiaries with more frequent inpatient use (Table 2). Among Medicare beneficiaries aged 85 years and older, the mean number of episodes per 1000 beneficiaries declined by 12.7%, from 524 to 457. Populations with less frequent inpatient use often experienced larger relative declines in number of episodes than populations with more frequent inpatient use. For example, the mean number of episodes per 1000 beneficiaries decreased by 17.7% for beneficiaries without nursing home use (306 to 252), as compared with an 8.1% decline for beneficiaries with nursing home use (from 888 to 816). In contrast, populations with less frequent inpatient use had larger relative increases in spending per episode with adjustment for payment rate changes. For example, spending per episode increased by 13.1% for beneficiaries aged 65 to 74 years ($20,904 to $23,644), but only by 8.6% for beneficiaries 85 years and older ($20,384 to $22,138).

Analyses Stratified by Service Use Characteristics

Some types of inpatient episodes had larger declines in the number of episodes, including episodes with planned admissions for the index hospital stay (28.8% decline from 68 to 48 episodes per 1000 beneficiaries) and episodes without post–acute care use (23.9% decline from 169 to 129 episodes per 1000 beneficiaries) (Appendix Table). In contrast, declines in the number of episodes were similar for index hospital admissions that did or did not involve ICU use (17.8% and 18.3% reduction in mean number of episodes per 1000 beneficiaries, respectively) or that included a surgical procedure or not (17.1% versus 18.6%, respectively). Several types of inpatient episodes had larger increases in spending per episode, such as a 15.1% increase for planned admissions and a 13.2% increase for hospitalizations without ICU use.

According to diagnosis information for an episode’s index hospital stay, inpatient episodes related to conditions affecting the circulatory system had the largest decline in mean number of episodes, decreasing by 31.8% from 78 to 53 episodes per 1000 beneficiaries (Appendix Table). Episodes for other diseases had much smaller declines in volume. Admissions for diagnoses of pneumonia or sepsis had notable increases in the volume of episodes, increasing by 20.7% from 25 to 30 admissions per 1000 beneficiaries.

DISCUSSION

Medicare spending per beneficiary on inpatient episodes, including services provided pre- and post hospitalization, declined by 8.9% from 2009 to 2017 after adjusting for payment rate changes. This decline reflects two components. First, the number of episodes per 1000 beneficiaries declined by 18.2%. Although the extent of this decrease varied across populations, every group examined had declines in inpatient use. In particular, hospitalizations for conditions affecting the circulatory system, such as heart attacks and cardiac procedures, decreased. Second, as inpatient volume declined, spending per episode increased by 11.4% to an average of $23,273 in 2017. This increase in spending per episode offset how much overall Medicare spending on episode-related care declined.

Medicare is increasingly challenging hospitals to demonstrate the value of inpatient services and associated treatment, which requires hospital leaders to recognize how their facilities’ spending trends relate to these national patterns. Understanding how much national episode-related spending has decreased over time with declining inpatient volume can help an accountable care organization evaluate whether it is feasible to achieve significant savings by reducing hospitalizations. Bundled payment providers focused on managing spending per episode can benefit from identifying which types of hospitalizations have increased spending per episode, especially for certain diagnoses.

These results also highlight the continued importance of a perennial factor in Medicare spending: payment rates. If Medicare payment rates had not increased over our study period, Medicare spending per inpatient episode would have increased by only 11%. Actual Medicare spending per episode increased by 25%, demonstrating that over half of the relative increase in spending per episode reflected increases in Medicare’s payment rates.

Increased spending per episode, even after adjustment for payment rate changes, suggests that services provided during an episode have increased in intensity or shifted toward higher-cost treatments.

When interpreting these trends, several points are notable. The underlying health of the Medicare population may contribute to declining inpatient use but is difficult to quantify. The observed decline in cardiac-related hospitalizations is consistent with evidence that the impact of ischemic heart disease, the leading source of disease or injury in the US population, has dramatically declined over recent decades15 and that the Medicare program has experienced large declines in overall spending and use related to cardiac conditions.16-18

Other potential factors include a shift toward hospitals treating Medicare beneficiaries as outpatients during an observation stay instead of admitting them as inpatients. Observation stays have increased as traditional Medicare implemented measures to penalize readmissions and limit payments for short inpatient stays.19-21 Even so, the increase in observation stays would have to be at least three times as large as described in other work to fully substitute for the decrease in inpatient stays: between the years 2007 and 2018, the number of observation stays per 1000 beneficiaries increased by only 26 stays, whereas the number of hospitalizations per 1000 beneficiaries decreased by 83 hospitalizations.20

Outpatient services may also broaden treatment availability in alternative settings or enable beneficiaries to avoid inpatient treatment with appropriate preventative care.22-27 These considerations are even more relevant as the COVID-19 pandemic spurred reduced admissions and shifted acute services outside of hospitals.28,29 Some services, such as elective surgeries, have probably shifted from an inpatient to an outpatient setting, which would be consistent with our finding that there are larger relative declines in planned hospitalizations. Although this analysis does not capture spending for outpatient services that are not linked to an inpatient admission, prior work demonstrates that annual growth in total Medicare spending per beneficiary (episode related or not) has recently declined for the inpatient sector but increased for outpatient and physician sectors.30 By offering other outpatient services, hospitals may be able to recoup some declining inpatient revenues. However, outpatient services are reimbursed at a lower rate than inpatient services, suggesting these trends may create financial pressure for hospitals.

There are several limitations to our analysis. First, our analysis is not designed to uncover the reason for the shift away from inpatient services nor to analyze how it has affected beneficiaries’ overall quality of care.

CONCLUSION

Over an 8-year period, Medicare spending per beneficiary on inpatient episodes, including all services immediately preceding and following hospitalizations, declined by 8.9% after taking into account payment rate increases. This broad shift away from inpatient services among all Medicare beneficiaries suggests policymakers should aim for payment policies that balance financial sustainability for hospitals and associated facilities with more efficient use of inpatient and related services.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sunita Thapa, Lucas Stewart, Christine Lai, and Liliana Podczerwinski for contributions in data analysis and manuscript preparation.

1. Sun R, Karaca Z, Wong HS. Trends in hospital inpatient stays by age and payer, 2000-2015: Statistical Brief #235. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006.

2. HCUP Fast Stats - trends in inpatient stays. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). April 2021. Accessed August 29, 2021. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/faststats/national/inpatienttrends.jsp

3. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Section 1: National health care and Medicare spending. In: A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program. June 2018. Accessed August 13, 2021. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/jun18_databooksec1_sec.pdf

4. Buntin MB, Graves JA. How the ACA dented the cost curve. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(3):403-412. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01478

5. Krumholz HM, Nuti SV, Downing NS, Normand SLT, Wang Y. Mortality, hospitalizations, and expenditures for the Medicare population aged 65 years or older, 1999-2013. JAMA. 2015;314(4):355-365. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.8035

6. Chen LM, Norton EC, Banerjee M, Regenbogen SE, Cain-Nielsen AH, Birkmeyer JD. Spending on care after surgery driven by choice of care settings instead of intensity of services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):83-90. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0668

7. Ibrahim AM, Nuliyalu U, Lawton EJ, et al. Evaluation of US hospital episode spending for acute inpatient conditions after the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2023926. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.23926

8. Rosen A, Aizcorbe A, Ryu AJ, Nestoriak N, Cutler DM, Chernew ME. Policy makers will need a way to update bundled payments that reflects highly skewed spending growth of various care episodes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(5):944-951. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1246

9. Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB. Association of diagnostic coding with trends in hospitalizations and mortality of patients with pneumonia, 2003-2009. JAMA. 2012;307(13):1405-1413. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.384

10. Buntin MB, Lai C, Podczerwinski L, Poon S, Wallis C. Changing diagnosis patterns are increasing Medicare spending for inpatient hospital services. The Commonwealth Fund. April 28, 2021. Accessed August 13, 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/apr/changing-diagnosis-patterns-are-increasing-medicare-spending-inpatient

11. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Hospital inpatient and outpatient services. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. . March 2018. Accessed August 13, 2021. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_ch3_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

12. Ody C, Msall L, Dafny LS, Grabowski DC, Cutler DM. Decreases In readmissions credited to Medicare’s program to reduce hospital readmissions have been overstated. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(1):36-43. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05178

13. Dharmarajan K, Qin L, Lin Z, et al. Declining admission rates and thirty-day readmission rates positively associated even though patients grew sicker over time. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1294-1302. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1614

14. Sjoding MW, Prescott HC, Wunsch H, Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR. Longitudinal changes in ICU admissions among elderly patients in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1353-1360. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001664

15. Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591-608. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.13805

16. Cutler DM, Ghosh K, Messer KL, Raghunathan TE, Stewart ST, Rosen AB. Explaining the slowdown in medical spending growth among the elderly, 1999-2012. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(2):222-229. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05372

17. Ward MJ, Kripalani S, Zhu Y, et al. Incidence of emergency department visits for ST-elevation myocardial infarction in a recent six-year period in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(2):167-170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.10.020

18. Keohane LM, Gambrel RJ, Freed SS, Stevenson D, Buntin MB. Understanding trends in Medicare spending, 2007-2014. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(5):3507-3527. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12845

19. Nuckols TK, Fingar KR, Barrett M, Steiner CA, Stocks C, Owens PL. The shifting landscape in utilization of inpatient, observation, and emergency department services across payers. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):443-446. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2751

20. Poon SJ, Wallis CJ, Lai P, Podczerwinski L, Buntin MB. Medicare two-midnight rule accelerated shift to observation stays. Health Affairs. In press.

21. Sheehy AM, Kaiksow F, Powell WR, et al. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program and observation hospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(7):409-411. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3634

22. Culler SD, Parchman ML, Przybylski M. Factors related to potentially preventable hospitalizations among the elderly. Med Care. 1998;36(6):804-817. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199806000-00004

23. Kozak LJ, Hall MJ, Owings MF. Trends in avoidable hospitalizations, 1980-1998. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(2):225-232. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.20.2.225

24. Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Perloe M, et al. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: frequency, causes, and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):627-635. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02768.x

25. Konetzka RT, Karon SL, Potter DEB. Users of Medicaid home and community-based services are especially vulnerable to costly avoidable hospital admissions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1167-1175. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0902

26. Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JPW, et al. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1879-1885. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10059

27. Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and causes of readmissions in a national cohort of general medicine patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):484-493. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7863

28. Birkmeyer JD, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

29. Nundy S, Patel KK. Hospital-at-home to support COVID-19 surge—time to bring down the walls? JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(5):e200504. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0504

30. Keohane LM, Stevenson DG, Freed S, Thapa S, Stewart L, Buntin MB. Trends in Medicare fee-for-service spending growth for dual-eligible beneficiaries, 2007–15. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(8):1265-1273. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0143

31. Freed M, Biniek JF, Damico A, Neuman T. Medicare Advantage in 2021: enrollment update and key trends. June 21, 2021. Accessed August 13, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-in-2021-enrollment-update-and-key-trends/

32. Li Q, Rahman M, Gozalo P, Keohane LM, Gold MR, Trivedi AN. Regional variations: the use of hospitals, home health, and skilled nursing in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(8):1274-1281. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0147

The rate of inpatient admissions among adults aged 65 years and older has decreased by approximately 25% since 2000.1,2 This long-term trend raises important questions about inpatient-related spending in the traditional Medicare program for hospitals and providers who treat beneficiaries after a hospitalization. As traditional Medicare’s most expensive sector (accounting for 21% of all Medicare spending3), reducing hospitalizations is often championed as an opportunity to moderate Medicare spending growth.

Medicare’s ability to achieve significant savings from declining inpatient use may be tempered by a shift toward more expensive hospitalizations. If marginal hospitalizations among healthier beneficiaries are avoided, then the remaining inpatient users may be sicker and have greater spending per hospitalization and greater need for follow-up services. This study examines trends in Medicare spending related to episodes initiated by an inpatient stay because of its importance to overall Medicare spending and the implications for several Medicare value-based payment initiatives. In care models seeking to contain spending at a population level, such as accountable care organizations and managed care plans, reducing inpatient use and associated services may have the largest impact in curbing overall spending growth per beneficiary. Other models focused on spending at an episode level, including bundled payment initiatives, may face challenges if inpatient episodes become more expensive over time.

As Medicare shifts toward value-based payments, hospitalists and other hospital leaders are often involved in redesigning care delivery models for the hospital or accountable care organization (eg, through readmission reduction initiatives, post–acute care coordination, and bundled-care delivery programs). Not all savings strategies rely on providers to change how services are delivered; Medicare can modify payment rates, such as Affordable Care Act provisions that slowed how quickly Medicare payment rates increased.4 For clinicians to navigate the shift toward new payment models, it is important to recognize how each of these elements—declining hospital admissions, spending per inpatient episode, and payment rates—affect spending trends for inpatient services and associated care. Previous articles on overall Medicare inpatient spending have examined inpatient stays alone5 or focused mainly on spending per episode6,7 without quantifying how these elements contributed to overall episode-related Medicare spending per beneficiary. This article addresses this gap by demonstrating how inpatient-related spending trends reflect each component.

This study examined trends in Medicare’s spending on inpatient episodes during the years 2009 to 2017. We described changes in the volume and spending on inpatient-initiated episodes across several dimensions, including beneficiary-level and hospitalization-level factors. We examined whether declines in spending associated with fewer inpatient-initiated episodes have been offset by increased spending per episode and how spending would have differed without changes in Medicare payment rates.

Episode Definition

We constructed an episode measure that captured traditional Medicare spending for 30 days prior to hospital admission, hospitalization duration, and 90 days following hospital discharge (additional details in the Appendix).

Any acute hospitalization triggered a new episode, with one exception: if a beneficiary was discharged and readmitted within 90 days for the same diagnosis-related group (DRG), then the readmission did not trigger a new episode. The spending for that readmission was attributed to the prior hospital stay. In effect, the annual number of episodes is equivalent to the annual number of hospital admissions minus subsequent rehospitalizations for the same DRG. Neither observation stays nor hospitalizations in inpatient rehabilitation, psychiatric, or long-term facilities were considered acute hospital admissions.

We assigned claims from noninpatient sectors to an episode based on whether the claim start date fell within the episode window. All traditional Medicare sectors were measured, including outpatient services, physician claims, post–acute care services, and Medicare Part D prescription drug events.

Our analysis aimed to measure all spending related to inpatient episodes without double-counting spending for overlapping episodes. If episodes overlapped, then spending for overlapping days was weighted to be evenly divided across episodes.

Outcome Measures

The study’s main outcomes summarized episode trends across the entire traditional Medicare population, including beneficiaries without an episode, in annual mean number of episodes per beneficiary and annual mean episode-related spending per beneficiary. The denominator of these measures is person-years, or total number of beneficiary months with Medicare Part A and B coverage divided by 12. The annual mean number of episodes per beneficiary is the total number of episodes initiated in a calendar year divided by person-years. The annual mean episode-related spending per beneficiary is the total amount of spending attributed to episodes divided by person-years. We also measured annual mean spending per episode, or total amount of spending attributed to episodes divided by the total number of episodes.

Medicare annually updates each sector’s payment rates for several factors, including inflation. We constructed an index for each sector to adjust for these annual payment rate changes. We also accounted for sequestration measures in effect since April 2013 that reduced Medicare payments to all sectors by 2%. We report our spending measures twice, with and without adjusting for changes in payment rates. Adjusted numbers reflect payment rates in effect in 2015.

Analysis Approach

We present annual trends on changes in the number of inpatient episodes per beneficiary, mean episode-related spending per beneficiary, and mean spending per episode. To quantify how changes in episode-related spending per beneficiary reflect changes in the number of episodes per beneficiary vs changes in spending per episode, we modified an approach implemented by Rosen and colleagues.8

To better understand which beneficiaries have declining inpatient use, we performed stratified analyses describing changes in the number of episodes per beneficiary between 2009 and 2017, spending per episode, and total episode-related spending per beneficiary. We report these measures for several subpopulations defined by age, sex, race, dual-eligible status, and whether the beneficiary used long-term nursing home services during the episode’s calendar year. Descriptive statistics also detail how these measures changed between 2009 and 2017 for episodes stratified by characteristics of the index hospital stay: planned vs unplanned, medical vs surgical, and any use of intensive care unit (ICU) or coronary care unit services. We also stratify study measures by whether an episode included any use of post–acute care services (skilled nursing facility, home health, or inpatient rehabilitation facility use). Finally, we aggregate the episodes into major diagnostic categories (MDCs) based on the index hospital stay’s DRG to report study outcomes by condition. Because of a shift in coding hospitalizations for pneumonia as sepsis,9,10 we exclude these two diseases from their respective MDCs and analyze them jointly as a unique category.

RESULTS

Changes in Number of Inpatient Episodes and Related Spending

From 2009 to 2017, the number of inpatient episodes per 1000 traditional Medicare beneficiaries declined from 326 to 267 (Table 1), or a relative decline of 18.2% (Figure 1). The total volume of inpatient episodes declined by only 13.4%, from 10.2 million to 8.8 million, reflecting that the size of the traditional Medicare population grew during these years. Over the same years, mean payment-rate–adjusted spending per episode increased 11.4% from $20,891 to $23,273.

When considering overall episode-related spending, the large decline in the volume of episodes outweighed increased spending per episode: the mean amount of episode-related Medicare spending per beneficiary decreased 8.9% from $6810 to $6206 (Table 1), or a net change of $604 (Figure 2). This net change reflects decreased spending due to fewer episodes per beneficiary ($1239 reduction in episode-related spending) offset by increased spending per episode (translating to a $776 increase in episode-related spending per beneficiary).

When these estimates are calculated separately for the inpatient sector and all other sectors, the inpatient sector experienced small increases in spending associated with greater spending per episode ($304) compared with noninpatient sectors ($472). Accordingly, the inpatient sector had a larger net decline in episode-related spending per beneficiary ($420) than noninpatient sectors ($184) after taking into account declining episode volume.

As expected, episode-related spending increased more when measures were not adjusted for annual payment rate increases. Without such adjustment, mean spending per episode increased 25.5%, and episode-related spending per beneficiary was nearly flat (2.6% between 2009 and 2017 [Figure 1]). The decline in unadjusted spending associated with fewer episodes ($1138) was offset by the spending increase associated with higher spending per episode ($1592) (Figure 2).

Analyses Stratified by Beneficiary Characteristics

Every population examined had declines in the number of inpatient episodes, even beneficiaries with more frequent inpatient use (Table 2). Among Medicare beneficiaries aged 85 years and older, the mean number of episodes per 1000 beneficiaries declined by 12.7%, from 524 to 457. Populations with less frequent inpatient use often experienced larger relative declines in number of episodes than populations with more frequent inpatient use. For example, the mean number of episodes per 1000 beneficiaries decreased by 17.7% for beneficiaries without nursing home use (306 to 252), as compared with an 8.1% decline for beneficiaries with nursing home use (from 888 to 816). In contrast, populations with less frequent inpatient use had larger relative increases in spending per episode with adjustment for payment rate changes. For example, spending per episode increased by 13.1% for beneficiaries aged 65 to 74 years ($20,904 to $23,644), but only by 8.6% for beneficiaries 85 years and older ($20,384 to $22,138).

Analyses Stratified by Service Use Characteristics

Some types of inpatient episodes had larger declines in the number of episodes, including episodes with planned admissions for the index hospital stay (28.8% decline from 68 to 48 episodes per 1000 beneficiaries) and episodes without post–acute care use (23.9% decline from 169 to 129 episodes per 1000 beneficiaries) (Appendix Table). In contrast, declines in the number of episodes were similar for index hospital admissions that did or did not involve ICU use (17.8% and 18.3% reduction in mean number of episodes per 1000 beneficiaries, respectively) or that included a surgical procedure or not (17.1% versus 18.6%, respectively). Several types of inpatient episodes had larger increases in spending per episode, such as a 15.1% increase for planned admissions and a 13.2% increase for hospitalizations without ICU use.

According to diagnosis information for an episode’s index hospital stay, inpatient episodes related to conditions affecting the circulatory system had the largest decline in mean number of episodes, decreasing by 31.8% from 78 to 53 episodes per 1000 beneficiaries (Appendix Table). Episodes for other diseases had much smaller declines in volume. Admissions for diagnoses of pneumonia or sepsis had notable increases in the volume of episodes, increasing by 20.7% from 25 to 30 admissions per 1000 beneficiaries.

DISCUSSION

Medicare spending per beneficiary on inpatient episodes, including services provided pre- and post hospitalization, declined by 8.9% from 2009 to 2017 after adjusting for payment rate changes. This decline reflects two components. First, the number of episodes per 1000 beneficiaries declined by 18.2%. Although the extent of this decrease varied across populations, every group examined had declines in inpatient use. In particular, hospitalizations for conditions affecting the circulatory system, such as heart attacks and cardiac procedures, decreased. Second, as inpatient volume declined, spending per episode increased by 11.4% to an average of $23,273 in 2017. This increase in spending per episode offset how much overall Medicare spending on episode-related care declined.

Medicare is increasingly challenging hospitals to demonstrate the value of inpatient services and associated treatment, which requires hospital leaders to recognize how their facilities’ spending trends relate to these national patterns. Understanding how much national episode-related spending has decreased over time with declining inpatient volume can help an accountable care organization evaluate whether it is feasible to achieve significant savings by reducing hospitalizations. Bundled payment providers focused on managing spending per episode can benefit from identifying which types of hospitalizations have increased spending per episode, especially for certain diagnoses.

These results also highlight the continued importance of a perennial factor in Medicare spending: payment rates. If Medicare payment rates had not increased over our study period, Medicare spending per inpatient episode would have increased by only 11%. Actual Medicare spending per episode increased by 25%, demonstrating that over half of the relative increase in spending per episode reflected increases in Medicare’s payment rates.

Increased spending per episode, even after adjustment for payment rate changes, suggests that services provided during an episode have increased in intensity or shifted toward higher-cost treatments.

When interpreting these trends, several points are notable. The underlying health of the Medicare population may contribute to declining inpatient use but is difficult to quantify. The observed decline in cardiac-related hospitalizations is consistent with evidence that the impact of ischemic heart disease, the leading source of disease or injury in the US population, has dramatically declined over recent decades15 and that the Medicare program has experienced large declines in overall spending and use related to cardiac conditions.16-18

Other potential factors include a shift toward hospitals treating Medicare beneficiaries as outpatients during an observation stay instead of admitting them as inpatients. Observation stays have increased as traditional Medicare implemented measures to penalize readmissions and limit payments for short inpatient stays.19-21 Even so, the increase in observation stays would have to be at least three times as large as described in other work to fully substitute for the decrease in inpatient stays: between the years 2007 and 2018, the number of observation stays per 1000 beneficiaries increased by only 26 stays, whereas the number of hospitalizations per 1000 beneficiaries decreased by 83 hospitalizations.20

Outpatient services may also broaden treatment availability in alternative settings or enable beneficiaries to avoid inpatient treatment with appropriate preventative care.22-27 These considerations are even more relevant as the COVID-19 pandemic spurred reduced admissions and shifted acute services outside of hospitals.28,29 Some services, such as elective surgeries, have probably shifted from an inpatient to an outpatient setting, which would be consistent with our finding that there are larger relative declines in planned hospitalizations. Although this analysis does not capture spending for outpatient services that are not linked to an inpatient admission, prior work demonstrates that annual growth in total Medicare spending per beneficiary (episode related or not) has recently declined for the inpatient sector but increased for outpatient and physician sectors.30 By offering other outpatient services, hospitals may be able to recoup some declining inpatient revenues. However, outpatient services are reimbursed at a lower rate than inpatient services, suggesting these trends may create financial pressure for hospitals.

There are several limitations to our analysis. First, our analysis is not designed to uncover the reason for the shift away from inpatient services nor to analyze how it has affected beneficiaries’ overall quality of care.

CONCLUSION

Over an 8-year period, Medicare spending per beneficiary on inpatient episodes, including all services immediately preceding and following hospitalizations, declined by 8.9% after taking into account payment rate increases. This broad shift away from inpatient services among all Medicare beneficiaries suggests policymakers should aim for payment policies that balance financial sustainability for hospitals and associated facilities with more efficient use of inpatient and related services.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sunita Thapa, Lucas Stewart, Christine Lai, and Liliana Podczerwinski for contributions in data analysis and manuscript preparation.

The rate of inpatient admissions among adults aged 65 years and older has decreased by approximately 25% since 2000.1,2 This long-term trend raises important questions about inpatient-related spending in the traditional Medicare program for hospitals and providers who treat beneficiaries after a hospitalization. As traditional Medicare’s most expensive sector (accounting for 21% of all Medicare spending3), reducing hospitalizations is often championed as an opportunity to moderate Medicare spending growth.

Medicare’s ability to achieve significant savings from declining inpatient use may be tempered by a shift toward more expensive hospitalizations. If marginal hospitalizations among healthier beneficiaries are avoided, then the remaining inpatient users may be sicker and have greater spending per hospitalization and greater need for follow-up services. This study examines trends in Medicare spending related to episodes initiated by an inpatient stay because of its importance to overall Medicare spending and the implications for several Medicare value-based payment initiatives. In care models seeking to contain spending at a population level, such as accountable care organizations and managed care plans, reducing inpatient use and associated services may have the largest impact in curbing overall spending growth per beneficiary. Other models focused on spending at an episode level, including bundled payment initiatives, may face challenges if inpatient episodes become more expensive over time.

As Medicare shifts toward value-based payments, hospitalists and other hospital leaders are often involved in redesigning care delivery models for the hospital or accountable care organization (eg, through readmission reduction initiatives, post–acute care coordination, and bundled-care delivery programs). Not all savings strategies rely on providers to change how services are delivered; Medicare can modify payment rates, such as Affordable Care Act provisions that slowed how quickly Medicare payment rates increased.4 For clinicians to navigate the shift toward new payment models, it is important to recognize how each of these elements—declining hospital admissions, spending per inpatient episode, and payment rates—affect spending trends for inpatient services and associated care. Previous articles on overall Medicare inpatient spending have examined inpatient stays alone5 or focused mainly on spending per episode6,7 without quantifying how these elements contributed to overall episode-related Medicare spending per beneficiary. This article addresses this gap by demonstrating how inpatient-related spending trends reflect each component.

This study examined trends in Medicare’s spending on inpatient episodes during the years 2009 to 2017. We described changes in the volume and spending on inpatient-initiated episodes across several dimensions, including beneficiary-level and hospitalization-level factors. We examined whether declines in spending associated with fewer inpatient-initiated episodes have been offset by increased spending per episode and how spending would have differed without changes in Medicare payment rates.

Episode Definition

We constructed an episode measure that captured traditional Medicare spending for 30 days prior to hospital admission, hospitalization duration, and 90 days following hospital discharge (additional details in the Appendix).

Any acute hospitalization triggered a new episode, with one exception: if a beneficiary was discharged and readmitted within 90 days for the same diagnosis-related group (DRG), then the readmission did not trigger a new episode. The spending for that readmission was attributed to the prior hospital stay. In effect, the annual number of episodes is equivalent to the annual number of hospital admissions minus subsequent rehospitalizations for the same DRG. Neither observation stays nor hospitalizations in inpatient rehabilitation, psychiatric, or long-term facilities were considered acute hospital admissions.

We assigned claims from noninpatient sectors to an episode based on whether the claim start date fell within the episode window. All traditional Medicare sectors were measured, including outpatient services, physician claims, post–acute care services, and Medicare Part D prescription drug events.

Our analysis aimed to measure all spending related to inpatient episodes without double-counting spending for overlapping episodes. If episodes overlapped, then spending for overlapping days was weighted to be evenly divided across episodes.

Outcome Measures

The study’s main outcomes summarized episode trends across the entire traditional Medicare population, including beneficiaries without an episode, in annual mean number of episodes per beneficiary and annual mean episode-related spending per beneficiary. The denominator of these measures is person-years, or total number of beneficiary months with Medicare Part A and B coverage divided by 12. The annual mean number of episodes per beneficiary is the total number of episodes initiated in a calendar year divided by person-years. The annual mean episode-related spending per beneficiary is the total amount of spending attributed to episodes divided by person-years. We also measured annual mean spending per episode, or total amount of spending attributed to episodes divided by the total number of episodes.

Medicare annually updates each sector’s payment rates for several factors, including inflation. We constructed an index for each sector to adjust for these annual payment rate changes. We also accounted for sequestration measures in effect since April 2013 that reduced Medicare payments to all sectors by 2%. We report our spending measures twice, with and without adjusting for changes in payment rates. Adjusted numbers reflect payment rates in effect in 2015.

Analysis Approach

We present annual trends on changes in the number of inpatient episodes per beneficiary, mean episode-related spending per beneficiary, and mean spending per episode. To quantify how changes in episode-related spending per beneficiary reflect changes in the number of episodes per beneficiary vs changes in spending per episode, we modified an approach implemented by Rosen and colleagues.8

To better understand which beneficiaries have declining inpatient use, we performed stratified analyses describing changes in the number of episodes per beneficiary between 2009 and 2017, spending per episode, and total episode-related spending per beneficiary. We report these measures for several subpopulations defined by age, sex, race, dual-eligible status, and whether the beneficiary used long-term nursing home services during the episode’s calendar year. Descriptive statistics also detail how these measures changed between 2009 and 2017 for episodes stratified by characteristics of the index hospital stay: planned vs unplanned, medical vs surgical, and any use of intensive care unit (ICU) or coronary care unit services. We also stratify study measures by whether an episode included any use of post–acute care services (skilled nursing facility, home health, or inpatient rehabilitation facility use). Finally, we aggregate the episodes into major diagnostic categories (MDCs) based on the index hospital stay’s DRG to report study outcomes by condition. Because of a shift in coding hospitalizations for pneumonia as sepsis,9,10 we exclude these two diseases from their respective MDCs and analyze them jointly as a unique category.

RESULTS

Changes in Number of Inpatient Episodes and Related Spending

From 2009 to 2017, the number of inpatient episodes per 1000 traditional Medicare beneficiaries declined from 326 to 267 (Table 1), or a relative decline of 18.2% (Figure 1). The total volume of inpatient episodes declined by only 13.4%, from 10.2 million to 8.8 million, reflecting that the size of the traditional Medicare population grew during these years. Over the same years, mean payment-rate–adjusted spending per episode increased 11.4% from $20,891 to $23,273.

When considering overall episode-related spending, the large decline in the volume of episodes outweighed increased spending per episode: the mean amount of episode-related Medicare spending per beneficiary decreased 8.9% from $6810 to $6206 (Table 1), or a net change of $604 (Figure 2). This net change reflects decreased spending due to fewer episodes per beneficiary ($1239 reduction in episode-related spending) offset by increased spending per episode (translating to a $776 increase in episode-related spending per beneficiary).

When these estimates are calculated separately for the inpatient sector and all other sectors, the inpatient sector experienced small increases in spending associated with greater spending per episode ($304) compared with noninpatient sectors ($472). Accordingly, the inpatient sector had a larger net decline in episode-related spending per beneficiary ($420) than noninpatient sectors ($184) after taking into account declining episode volume.

As expected, episode-related spending increased more when measures were not adjusted for annual payment rate increases. Without such adjustment, mean spending per episode increased 25.5%, and episode-related spending per beneficiary was nearly flat (2.6% between 2009 and 2017 [Figure 1]). The decline in unadjusted spending associated with fewer episodes ($1138) was offset by the spending increase associated with higher spending per episode ($1592) (Figure 2).

Analyses Stratified by Beneficiary Characteristics

Every population examined had declines in the number of inpatient episodes, even beneficiaries with more frequent inpatient use (Table 2). Among Medicare beneficiaries aged 85 years and older, the mean number of episodes per 1000 beneficiaries declined by 12.7%, from 524 to 457. Populations with less frequent inpatient use often experienced larger relative declines in number of episodes than populations with more frequent inpatient use. For example, the mean number of episodes per 1000 beneficiaries decreased by 17.7% for beneficiaries without nursing home use (306 to 252), as compared with an 8.1% decline for beneficiaries with nursing home use (from 888 to 816). In contrast, populations with less frequent inpatient use had larger relative increases in spending per episode with adjustment for payment rate changes. For example, spending per episode increased by 13.1% for beneficiaries aged 65 to 74 years ($20,904 to $23,644), but only by 8.6% for beneficiaries 85 years and older ($20,384 to $22,138).

Analyses Stratified by Service Use Characteristics

Some types of inpatient episodes had larger declines in the number of episodes, including episodes with planned admissions for the index hospital stay (28.8% decline from 68 to 48 episodes per 1000 beneficiaries) and episodes without post–acute care use (23.9% decline from 169 to 129 episodes per 1000 beneficiaries) (Appendix Table). In contrast, declines in the number of episodes were similar for index hospital admissions that did or did not involve ICU use (17.8% and 18.3% reduction in mean number of episodes per 1000 beneficiaries, respectively) or that included a surgical procedure or not (17.1% versus 18.6%, respectively). Several types of inpatient episodes had larger increases in spending per episode, such as a 15.1% increase for planned admissions and a 13.2% increase for hospitalizations without ICU use.

According to diagnosis information for an episode’s index hospital stay, inpatient episodes related to conditions affecting the circulatory system had the largest decline in mean number of episodes, decreasing by 31.8% from 78 to 53 episodes per 1000 beneficiaries (Appendix Table). Episodes for other diseases had much smaller declines in volume. Admissions for diagnoses of pneumonia or sepsis had notable increases in the volume of episodes, increasing by 20.7% from 25 to 30 admissions per 1000 beneficiaries.

DISCUSSION

Medicare spending per beneficiary on inpatient episodes, including services provided pre- and post hospitalization, declined by 8.9% from 2009 to 2017 after adjusting for payment rate changes. This decline reflects two components. First, the number of episodes per 1000 beneficiaries declined by 18.2%. Although the extent of this decrease varied across populations, every group examined had declines in inpatient use. In particular, hospitalizations for conditions affecting the circulatory system, such as heart attacks and cardiac procedures, decreased. Second, as inpatient volume declined, spending per episode increased by 11.4% to an average of $23,273 in 2017. This increase in spending per episode offset how much overall Medicare spending on episode-related care declined.

Medicare is increasingly challenging hospitals to demonstrate the value of inpatient services and associated treatment, which requires hospital leaders to recognize how their facilities’ spending trends relate to these national patterns. Understanding how much national episode-related spending has decreased over time with declining inpatient volume can help an accountable care organization evaluate whether it is feasible to achieve significant savings by reducing hospitalizations. Bundled payment providers focused on managing spending per episode can benefit from identifying which types of hospitalizations have increased spending per episode, especially for certain diagnoses.

These results also highlight the continued importance of a perennial factor in Medicare spending: payment rates. If Medicare payment rates had not increased over our study period, Medicare spending per inpatient episode would have increased by only 11%. Actual Medicare spending per episode increased by 25%, demonstrating that over half of the relative increase in spending per episode reflected increases in Medicare’s payment rates.

Increased spending per episode, even after adjustment for payment rate changes, suggests that services provided during an episode have increased in intensity or shifted toward higher-cost treatments.

When interpreting these trends, several points are notable. The underlying health of the Medicare population may contribute to declining inpatient use but is difficult to quantify. The observed decline in cardiac-related hospitalizations is consistent with evidence that the impact of ischemic heart disease, the leading source of disease or injury in the US population, has dramatically declined over recent decades15 and that the Medicare program has experienced large declines in overall spending and use related to cardiac conditions.16-18

Other potential factors include a shift toward hospitals treating Medicare beneficiaries as outpatients during an observation stay instead of admitting them as inpatients. Observation stays have increased as traditional Medicare implemented measures to penalize readmissions and limit payments for short inpatient stays.19-21 Even so, the increase in observation stays would have to be at least three times as large as described in other work to fully substitute for the decrease in inpatient stays: between the years 2007 and 2018, the number of observation stays per 1000 beneficiaries increased by only 26 stays, whereas the number of hospitalizations per 1000 beneficiaries decreased by 83 hospitalizations.20

Outpatient services may also broaden treatment availability in alternative settings or enable beneficiaries to avoid inpatient treatment with appropriate preventative care.22-27 These considerations are even more relevant as the COVID-19 pandemic spurred reduced admissions and shifted acute services outside of hospitals.28,29 Some services, such as elective surgeries, have probably shifted from an inpatient to an outpatient setting, which would be consistent with our finding that there are larger relative declines in planned hospitalizations. Although this analysis does not capture spending for outpatient services that are not linked to an inpatient admission, prior work demonstrates that annual growth in total Medicare spending per beneficiary (episode related or not) has recently declined for the inpatient sector but increased for outpatient and physician sectors.30 By offering other outpatient services, hospitals may be able to recoup some declining inpatient revenues. However, outpatient services are reimbursed at a lower rate than inpatient services, suggesting these trends may create financial pressure for hospitals.

There are several limitations to our analysis. First, our analysis is not designed to uncover the reason for the shift away from inpatient services nor to analyze how it has affected beneficiaries’ overall quality of care.

CONCLUSION

Over an 8-year period, Medicare spending per beneficiary on inpatient episodes, including all services immediately preceding and following hospitalizations, declined by 8.9% after taking into account payment rate increases. This broad shift away from inpatient services among all Medicare beneficiaries suggests policymakers should aim for payment policies that balance financial sustainability for hospitals and associated facilities with more efficient use of inpatient and related services.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sunita Thapa, Lucas Stewart, Christine Lai, and Liliana Podczerwinski for contributions in data analysis and manuscript preparation.

1. Sun R, Karaca Z, Wong HS. Trends in hospital inpatient stays by age and payer, 2000-2015: Statistical Brief #235. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006.

2. HCUP Fast Stats - trends in inpatient stays. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). April 2021. Accessed August 29, 2021. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/faststats/national/inpatienttrends.jsp

3. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Section 1: National health care and Medicare spending. In: A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program. June 2018. Accessed August 13, 2021. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/jun18_databooksec1_sec.pdf

4. Buntin MB, Graves JA. How the ACA dented the cost curve. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(3):403-412. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01478

5. Krumholz HM, Nuti SV, Downing NS, Normand SLT, Wang Y. Mortality, hospitalizations, and expenditures for the Medicare population aged 65 years or older, 1999-2013. JAMA. 2015;314(4):355-365. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.8035

6. Chen LM, Norton EC, Banerjee M, Regenbogen SE, Cain-Nielsen AH, Birkmeyer JD. Spending on care after surgery driven by choice of care settings instead of intensity of services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):83-90. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0668

7. Ibrahim AM, Nuliyalu U, Lawton EJ, et al. Evaluation of US hospital episode spending for acute inpatient conditions after the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2023926. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.23926

8. Rosen A, Aizcorbe A, Ryu AJ, Nestoriak N, Cutler DM, Chernew ME. Policy makers will need a way to update bundled payments that reflects highly skewed spending growth of various care episodes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(5):944-951. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1246

9. Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB. Association of diagnostic coding with trends in hospitalizations and mortality of patients with pneumonia, 2003-2009. JAMA. 2012;307(13):1405-1413. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.384

10. Buntin MB, Lai C, Podczerwinski L, Poon S, Wallis C. Changing diagnosis patterns are increasing Medicare spending for inpatient hospital services. The Commonwealth Fund. April 28, 2021. Accessed August 13, 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/apr/changing-diagnosis-patterns-are-increasing-medicare-spending-inpatient

11. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Hospital inpatient and outpatient services. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. . March 2018. Accessed August 13, 2021. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_ch3_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

12. Ody C, Msall L, Dafny LS, Grabowski DC, Cutler DM. Decreases In readmissions credited to Medicare’s program to reduce hospital readmissions have been overstated. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(1):36-43. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05178

13. Dharmarajan K, Qin L, Lin Z, et al. Declining admission rates and thirty-day readmission rates positively associated even though patients grew sicker over time. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1294-1302. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1614

14. Sjoding MW, Prescott HC, Wunsch H, Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR. Longitudinal changes in ICU admissions among elderly patients in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1353-1360. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001664

15. Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591-608. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.13805

16. Cutler DM, Ghosh K, Messer KL, Raghunathan TE, Stewart ST, Rosen AB. Explaining the slowdown in medical spending growth among the elderly, 1999-2012. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(2):222-229. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05372

17. Ward MJ, Kripalani S, Zhu Y, et al. Incidence of emergency department visits for ST-elevation myocardial infarction in a recent six-year period in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(2):167-170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.10.020

18. Keohane LM, Gambrel RJ, Freed SS, Stevenson D, Buntin MB. Understanding trends in Medicare spending, 2007-2014. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(5):3507-3527. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12845

19. Nuckols TK, Fingar KR, Barrett M, Steiner CA, Stocks C, Owens PL. The shifting landscape in utilization of inpatient, observation, and emergency department services across payers. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):443-446. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2751

20. Poon SJ, Wallis CJ, Lai P, Podczerwinski L, Buntin MB. Medicare two-midnight rule accelerated shift to observation stays. Health Affairs. In press.

21. Sheehy AM, Kaiksow F, Powell WR, et al. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program and observation hospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(7):409-411. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3634

22. Culler SD, Parchman ML, Przybylski M. Factors related to potentially preventable hospitalizations among the elderly. Med Care. 1998;36(6):804-817. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199806000-00004

23. Kozak LJ, Hall MJ, Owings MF. Trends in avoidable hospitalizations, 1980-1998. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(2):225-232. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.20.2.225

24. Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Perloe M, et al. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: frequency, causes, and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):627-635. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02768.x

25. Konetzka RT, Karon SL, Potter DEB. Users of Medicaid home and community-based services are especially vulnerable to costly avoidable hospital admissions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1167-1175. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0902

26. Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JPW, et al. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1879-1885. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10059

27. Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and causes of readmissions in a national cohort of general medicine patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):484-493. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7863

28. Birkmeyer JD, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

29. Nundy S, Patel KK. Hospital-at-home to support COVID-19 surge—time to bring down the walls? JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(5):e200504. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0504

30. Keohane LM, Stevenson DG, Freed S, Thapa S, Stewart L, Buntin MB. Trends in Medicare fee-for-service spending growth for dual-eligible beneficiaries, 2007–15. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(8):1265-1273. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0143

31. Freed M, Biniek JF, Damico A, Neuman T. Medicare Advantage in 2021: enrollment update and key trends. June 21, 2021. Accessed August 13, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-in-2021-enrollment-update-and-key-trends/

32. Li Q, Rahman M, Gozalo P, Keohane LM, Gold MR, Trivedi AN. Regional variations: the use of hospitals, home health, and skilled nursing in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(8):1274-1281. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0147

1. Sun R, Karaca Z, Wong HS. Trends in hospital inpatient stays by age and payer, 2000-2015: Statistical Brief #235. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006.

2. HCUP Fast Stats - trends in inpatient stays. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). April 2021. Accessed August 29, 2021. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/faststats/national/inpatienttrends.jsp

3. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Section 1: National health care and Medicare spending. In: A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program. June 2018. Accessed August 13, 2021. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/jun18_databooksec1_sec.pdf

4. Buntin MB, Graves JA. How the ACA dented the cost curve. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(3):403-412. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01478

5. Krumholz HM, Nuti SV, Downing NS, Normand SLT, Wang Y. Mortality, hospitalizations, and expenditures for the Medicare population aged 65 years or older, 1999-2013. JAMA. 2015;314(4):355-365. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.8035

6. Chen LM, Norton EC, Banerjee M, Regenbogen SE, Cain-Nielsen AH, Birkmeyer JD. Spending on care after surgery driven by choice of care settings instead of intensity of services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):83-90. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0668

7. Ibrahim AM, Nuliyalu U, Lawton EJ, et al. Evaluation of US hospital episode spending for acute inpatient conditions after the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2023926. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.23926

8. Rosen A, Aizcorbe A, Ryu AJ, Nestoriak N, Cutler DM, Chernew ME. Policy makers will need a way to update bundled payments that reflects highly skewed spending growth of various care episodes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(5):944-951. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1246

9. Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB. Association of diagnostic coding with trends in hospitalizations and mortality of patients with pneumonia, 2003-2009. JAMA. 2012;307(13):1405-1413. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.384

10. Buntin MB, Lai C, Podczerwinski L, Poon S, Wallis C. Changing diagnosis patterns are increasing Medicare spending for inpatient hospital services. The Commonwealth Fund. April 28, 2021. Accessed August 13, 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/apr/changing-diagnosis-patterns-are-increasing-medicare-spending-inpatient

11. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Hospital inpatient and outpatient services. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. . March 2018. Accessed August 13, 2021. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_ch3_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

12. Ody C, Msall L, Dafny LS, Grabowski DC, Cutler DM. Decreases In readmissions credited to Medicare’s program to reduce hospital readmissions have been overstated. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(1):36-43. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05178

13. Dharmarajan K, Qin L, Lin Z, et al. Declining admission rates and thirty-day readmission rates positively associated even though patients grew sicker over time. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1294-1302. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1614

14. Sjoding MW, Prescott HC, Wunsch H, Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR. Longitudinal changes in ICU admissions among elderly patients in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1353-1360. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001664

15. Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591-608. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.13805

16. Cutler DM, Ghosh K, Messer KL, Raghunathan TE, Stewart ST, Rosen AB. Explaining the slowdown in medical spending growth among the elderly, 1999-2012. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(2):222-229. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05372

17. Ward MJ, Kripalani S, Zhu Y, et al. Incidence of emergency department visits for ST-elevation myocardial infarction in a recent six-year period in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(2):167-170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.10.020

18. Keohane LM, Gambrel RJ, Freed SS, Stevenson D, Buntin MB. Understanding trends in Medicare spending, 2007-2014. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(5):3507-3527. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12845

19. Nuckols TK, Fingar KR, Barrett M, Steiner CA, Stocks C, Owens PL. The shifting landscape in utilization of inpatient, observation, and emergency department services across payers. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):443-446. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2751

20. Poon SJ, Wallis CJ, Lai P, Podczerwinski L, Buntin MB. Medicare two-midnight rule accelerated shift to observation stays. Health Affairs. In press.

21. Sheehy AM, Kaiksow F, Powell WR, et al. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program and observation hospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(7):409-411. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3634

22. Culler SD, Parchman ML, Przybylski M. Factors related to potentially preventable hospitalizations among the elderly. Med Care. 1998;36(6):804-817. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199806000-00004

23. Kozak LJ, Hall MJ, Owings MF. Trends in avoidable hospitalizations, 1980-1998. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(2):225-232. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.20.2.225

24. Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Perloe M, et al. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: frequency, causes, and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):627-635. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02768.x

25. Konetzka RT, Karon SL, Potter DEB. Users of Medicaid home and community-based services are especially vulnerable to costly avoidable hospital admissions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1167-1175. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0902

26. Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JPW, et al. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1879-1885. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10059

27. Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and causes of readmissions in a national cohort of general medicine patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):484-493. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7863

28. Birkmeyer JD, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

29. Nundy S, Patel KK. Hospital-at-home to support COVID-19 surge—time to bring down the walls? JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(5):e200504. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0504

30. Keohane LM, Stevenson DG, Freed S, Thapa S, Stewart L, Buntin MB. Trends in Medicare fee-for-service spending growth for dual-eligible beneficiaries, 2007–15. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(8):1265-1273. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0143

31. Freed M, Biniek JF, Damico A, Neuman T. Medicare Advantage in 2021: enrollment update and key trends. June 21, 2021. Accessed August 13, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-in-2021-enrollment-update-and-key-trends/

32. Li Q, Rahman M, Gozalo P, Keohane LM, Gold MR, Trivedi AN. Regional variations: the use of hospitals, home health, and skilled nursing in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(8):1274-1281. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0147

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine