User login

ABSTRACT

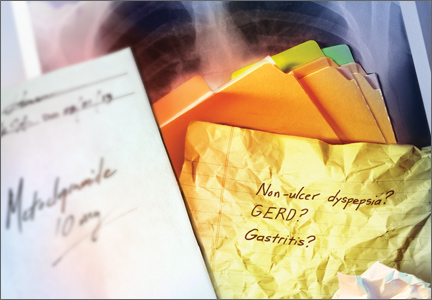

Purpose Primary care physicians sometimes encounter patients with clinical complaints that do not fit into a recognized diagnostic pattern. This study was undertaken to assess the way physicians respond to patients whose symptoms are unusual or unexplained—that is, what approach they take in the absence of a working hypothesis.

Methods We surveyed 130 primary care physicians affiliated with 3 academic centers in Israel, presenting 5 clinical vignettes describing patients who had unusual complaints, no clear diagnosis, and no apparent need for urgent care. We asked physicians to provide the most likely diagnosis for each case and to rate their level of confidence in that diagnosis;respondents were also asked to provide a management strategy for each case and their level of confidence in the chosen approach. Finally, we asked the physicians to estimate how many of their own patients have presentations similar to the individuals in the clinical vignettes.

Results Physicians proposed, on average, 22 diagnoses for each case. Most indicated that they would choose action (testing, consulting, sending the patient to the emergency department, or prescribing) rather than follow-up only (87% vs 13%; P<.01). Respondents’ confidence in the management approach they had chosen for all the cases was higher than their confidence in the diagnoses (5.6 vs 4.3, respectively, on a scale of1-10; P<.001). Physicians estimated that 10% to 20% of the patients they see in their practice have unusual or unexplained symptoms that are difficult to diagnose.

Conclusion Uncertain diagnosis is a regular challenge for primary care physicians. In such cases, we found that physicians prefer a workup to follow-up, an inclination consistent with“action bias.”

Physicians in primary care sometimes encounter patients with clinical complaints that do not fit into a recognized diagnostic pattern.1 There are varying reports of the prevalence of such cases, ranging from ≤10% when stringent definitions of medically unexplained symptoms are used2 to as high as 40% to 60% of visits.3,4 Unexplained complaints, which may or may not be related to psychiatric disorders, can significantly contribute to high consumption of health care resources.5 Uncertain diagnoses are associated with increased testing6 and false-positive results, which often lead to more tests and complications.7

When physicians face medically unexplained symptoms, their behavior often differs from the watchful waiting approach some recommend.6 This behavior has been attributed to various factors, such as fear of litigation, greater concern about omission than commission, and perception of patient expectations.5 A study involving young patients suggested bias toward intervention for common pediatric diagnoses.8 Using a similar design of physician responses to clinical vignettes,we sought to evaluate a potential bias toward action, such as testing or referral, for patients with unexplained medical complaints.

Methods

Over several months, 2 of us (AK, IG) identified 60 patients in our practices who had(1) unusual medical complaints, (2) no clear diagnosis, and (3) no apparent need for urgent care. After careful consideration, our team selected 5 cases that best fit the above criteria and reflected the widest spectrum of clinical presentations encountered in primary care settings. After removing identifying patient information, we wrote each case up as a clinical vignette, then presented all 5 cases to primary care physicians affiliated with 3 major academic centers. For each case, respondents were asked to provide:

- the most likely diagnosis and their level of confidence in that diagnosis (on a scale of 1 [no confidence] to 10 [complete confidence])

- a management strategy (testing, consulting with a specialist, referral to the emergency department [ED], prescribing medication, or follow-up only) and their level of confidence in that choice.

Physicians were asked to estimate the frequency of such cases in their practice, as well.

Preparation of the data (cleaning, sorting, and filtering) was carried out using JMPv9.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and analyses were conducted with SPSS v19.0 (IBM,Chicago, Ill). We used descriptive statistics to represent the data and chi-square and ANOVA to compare physicians’ decisions(action vs follow-up). Nonparametric tests were used to compare levels of confidence for diagnosis and management.

Results

We surveyed a convenience sample of 130 primary care physicians affiliated with academic medical centers, 100 of whom responded. Most respondents (62%) were female, and 86% were certified in family medicine. The average age was 45 years (range 30-68 years),with a mean time out of medical school of 17 years (range 1-26 years). Respondents were born in 14 different countries and had undergone medical training in Europe, the United States, or Israel. The diagnoses and management approaches selected for each clinical vignette are presented in TABLE 1. For each case, an average of 22 diagnoses (range 18-25) were proposed. Most physicians (87%; P<.01) indicated that they would choose some type of action (testing, consulting, sending the patient to the ED,or prescribing medication) rather than follow-up alone (TABLE 2). Respondents were able to choose multiple management There appears to be a stronger perceived need to “do something” than to engage in watchful waiting and follow-up.strategies. For all 5 cases, the physicians had more confidence in their patient management approach than in their diagnosis (5.6 vs 4.3;P<.001). On average, men had higher levels of confidence than women for both diagnosis and management (P<.05). Other demographic characteristics, including age, experience, certification, and site of training, were not predictive of confidence level. Respondents estimated that 10% to 20% of their own patients present with unusual and unexplained symptoms, like the patients in the clinical vignettes.

Discussion

Patients with undiagnosed signs and/or symptoms present a significant challenge in primary care. In such cases, physicians prefer a work-up to follow-up, with a confidence level in their management strategy that is higher than for their diagnostic hypotheses. There appears to be a stronger perceived need to “do something” than to engage in watchful waiting and follow-up.

Symptoms subside without treatment. Notably, in all the cases that formed the basis for the clinical vignettes used in our survey, the patients’ complaints eventually subsided, with no specific therapy. In some cases of unclear diagnosis, an active work-up may be justified; in others, watchful waiting before testing for unexplained complaints may be preferable.

Action bias. The preference for action over inaction in all the cases presented suggests what has been described as “action bias.”9 The term is derived from sports; in soccer penalty kicks, for example, it applies to goalkeepers who jump before they can see the kick direction and miss.10 According to the norm theory,11 such errors of commission derive from players’ perception that they are expected to act.10 Conversely, in instances in which inaction is the norm, an omission bias prevails, as people tend to judge acts that are harmful as worse than omissions that are even more harmful.10 In medicine, action bias has been found to influence clinical practice and contribute to overuse of both diagnostic testing and procedures.12-14

Gender difference. Gender has been shown to affect self-perception in cognitive bias.15 In a study of confidence levels among undergraduate students, overconfidence was found to be more prevalent among males than females, particularly for incorrect answers.16 This observation may relate to the gender differences in our study in physicians facing diagnostic uncertainty.

Study limitations. Our research was limited by the nature and type of our sample, but because the inclination to act was found in both immigrant and native practitioners, the observation of action bias could be generalizable to all primary care physicians. The clinical vignettes we chose may not be representative of commonly seen cases of medically unexplained symptoms. Also, our questionnaire was not tested beyond at face validity. It is possible, too, that nonresponders would be less inclined to action in the face of uncertainty. With the high (77%) response rate to our survey, however, their inclusion would be unlikely to strikingly alter the results.

Another limitation inherent to the design of our study is that physicians may respond to vignettes in a way that is substantially different than their response in actual practice. In a practice setting, physicians are able to listen to a full narrative and apply various doctor-patient communication tools, which are especially important in the context of unexplained complaints.17 On the other hand, the artificial setting may reduce the fear of litigation. Our observation of greater confidence in the need for action than for the diagnostic hypothesis is consistent with testing overuse in field studies.6 The fact that our survey went only to physicians affiliated with academic centers is another potential limitation, although it is not clear whether these clinicians differ from nonacademic physicians in their approach to unexplained complaints. Finally, the design of this study did not allow us to explore the reasons for action bias, a task that might be addressed in focus groups or interviews.

A closer look at bias. Our findings suggest a need for more in-depth research on potential biases that drive medical overuse, as part of an overall strategy to improve physicians’approach to medically unexplained symptoms.17 Remedies may require training, practice and failure feedback, quality improvement tools, and innovative management strategies.1,18 Uncertain diagnosis appears to be a frequent challenge in primary care settings. Inthe face of uncertainty, weighing the potential harms of overtesting vs follow-up and facilitating an informed decision-making process with the patient may lead to a reduction inaction bias,19 and thus, in the increased testing and higher health care consumption that often result.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mayer Brezis, MD, Center for Clinical Quality & Safety, Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, 91120 Jerusalem, Israel; [email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Steven R. Simon, MD, MPH, for his help with the preparation of this manuscript.

1. Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: an epidemiological study in seven specialities. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:361-367.

2. Swanson LM, Hamilton JC, Feldman MD. Physician-based estimates of medically unexplained symptoms: a comparison of four case definitions. Fam Pract. 2010;27:487-493.

3. Thomas KB. Temporarily dependent patient in general practice. BMJ. 1974;1:625-626.

4. Jones R, Barraclough K, Dowrick C. When no diagnostic label is applied. BMJ. 2010;340:1302-1304.

5. Todd JW. Wasted resources. Investigations. Lancet. 1984;2:1146-1147.

6. van der Weijden T, van Velsen M, Dinant GJ, et al. Unexplained complaints in general practice: prevalence, patients’ expectations, and professionals’ test-ordering behavior. Med Decis Making. 2003;23:226-231.

7. Brody H. From an ethics of rationing to an ethics of waste avoidance. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1949-1951.

8. Ayanian JZ, Berwick DM. Do physicians have a bias toward action? A classic study revisited. Med Decis Making. 1991;11:154-158.

9. Patt A, Zeckhauser R. Action bias and environmental decisions. J Risk Uncertain. 2000;21:45-72.

10. Bar-Eli M, Azar OH, Ritov I, et al. Action bias among elite soccer goalkeepers: the case of penalty kicks. J Econ Psychol. 2007;28:606-621.

11. Kahneman D, Miller DT. Norm theory: comparing reality to its alternatives. Psychol Rev. 1986;93:136-153.

12. Doust J, Del Mar C. Why do doctors use treatments that do not work? BMJ. 2004;328:474-475.

13. Scott IA. Errors in clinical reasoning: causes and remedial strategies. BMJ. 2009;338:22-25.

14. Cohain JS. Is action bias one of the numerous causes of ‘unnecaesareans’? Midwif Dig. 2009;19:495-499.

15. Beyer S, Bowden EM. Gender differences in self-perceptions: convergent evidence from three measures of accuracy and bias. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1997;23:157-172.

16. Lundeberg MA, Fox PW, Punccohar J. Highly confident but wrong: gender differences and similarities in confidence judgments. J Educ Psychol. 1994;86:114-121.

17. Heijmans M, Olde Hartman TC, van Weel-Baumgarten E, et al. Experts’ opinions on the management of medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. A qualitative analysis of narrative reviews and scientific editorials. Fam Pract. 2011;28:444-455.

18. Croskerry P, Norman G. Overconfidence in clinical decision making. Am J Med. 2008;121(5 suppl):S24-S29.

19. Feinstein AR. The ‘chagrin factor’ and qualitative decision analysis. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1257-1259.

Mayer Brezis; MD; MPH; action bias; unexplained complaints; management strategies

ABSTRACT

Purpose Primary care physicians sometimes encounter patients with clinical complaints that do not fit into a recognized diagnostic pattern. This study was undertaken to assess the way physicians respond to patients whose symptoms are unusual or unexplained—that is, what approach they take in the absence of a working hypothesis.

Methods We surveyed 130 primary care physicians affiliated with 3 academic centers in Israel, presenting 5 clinical vignettes describing patients who had unusual complaints, no clear diagnosis, and no apparent need for urgent care. We asked physicians to provide the most likely diagnosis for each case and to rate their level of confidence in that diagnosis;respondents were also asked to provide a management strategy for each case and their level of confidence in the chosen approach. Finally, we asked the physicians to estimate how many of their own patients have presentations similar to the individuals in the clinical vignettes.

Results Physicians proposed, on average, 22 diagnoses for each case. Most indicated that they would choose action (testing, consulting, sending the patient to the emergency department, or prescribing) rather than follow-up only (87% vs 13%; P<.01). Respondents’ confidence in the management approach they had chosen for all the cases was higher than their confidence in the diagnoses (5.6 vs 4.3, respectively, on a scale of1-10; P<.001). Physicians estimated that 10% to 20% of the patients they see in their practice have unusual or unexplained symptoms that are difficult to diagnose.

Conclusion Uncertain diagnosis is a regular challenge for primary care physicians. In such cases, we found that physicians prefer a workup to follow-up, an inclination consistent with“action bias.”

Physicians in primary care sometimes encounter patients with clinical complaints that do not fit into a recognized diagnostic pattern.1 There are varying reports of the prevalence of such cases, ranging from ≤10% when stringent definitions of medically unexplained symptoms are used2 to as high as 40% to 60% of visits.3,4 Unexplained complaints, which may or may not be related to psychiatric disorders, can significantly contribute to high consumption of health care resources.5 Uncertain diagnoses are associated with increased testing6 and false-positive results, which often lead to more tests and complications.7

When physicians face medically unexplained symptoms, their behavior often differs from the watchful waiting approach some recommend.6 This behavior has been attributed to various factors, such as fear of litigation, greater concern about omission than commission, and perception of patient expectations.5 A study involving young patients suggested bias toward intervention for common pediatric diagnoses.8 Using a similar design of physician responses to clinical vignettes,we sought to evaluate a potential bias toward action, such as testing or referral, for patients with unexplained medical complaints.

Methods

Over several months, 2 of us (AK, IG) identified 60 patients in our practices who had(1) unusual medical complaints, (2) no clear diagnosis, and (3) no apparent need for urgent care. After careful consideration, our team selected 5 cases that best fit the above criteria and reflected the widest spectrum of clinical presentations encountered in primary care settings. After removing identifying patient information, we wrote each case up as a clinical vignette, then presented all 5 cases to primary care physicians affiliated with 3 major academic centers. For each case, respondents were asked to provide:

- the most likely diagnosis and their level of confidence in that diagnosis (on a scale of 1 [no confidence] to 10 [complete confidence])

- a management strategy (testing, consulting with a specialist, referral to the emergency department [ED], prescribing medication, or follow-up only) and their level of confidence in that choice.

Physicians were asked to estimate the frequency of such cases in their practice, as well.

Preparation of the data (cleaning, sorting, and filtering) was carried out using JMPv9.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and analyses were conducted with SPSS v19.0 (IBM,Chicago, Ill). We used descriptive statistics to represent the data and chi-square and ANOVA to compare physicians’ decisions(action vs follow-up). Nonparametric tests were used to compare levels of confidence for diagnosis and management.

Results

We surveyed a convenience sample of 130 primary care physicians affiliated with academic medical centers, 100 of whom responded. Most respondents (62%) were female, and 86% were certified in family medicine. The average age was 45 years (range 30-68 years),with a mean time out of medical school of 17 years (range 1-26 years). Respondents were born in 14 different countries and had undergone medical training in Europe, the United States, or Israel. The diagnoses and management approaches selected for each clinical vignette are presented in TABLE 1. For each case, an average of 22 diagnoses (range 18-25) were proposed. Most physicians (87%; P<.01) indicated that they would choose some type of action (testing, consulting, sending the patient to the ED,or prescribing medication) rather than follow-up alone (TABLE 2). Respondents were able to choose multiple management There appears to be a stronger perceived need to “do something” than to engage in watchful waiting and follow-up.strategies. For all 5 cases, the physicians had more confidence in their patient management approach than in their diagnosis (5.6 vs 4.3;P<.001). On average, men had higher levels of confidence than women for both diagnosis and management (P<.05). Other demographic characteristics, including age, experience, certification, and site of training, were not predictive of confidence level. Respondents estimated that 10% to 20% of their own patients present with unusual and unexplained symptoms, like the patients in the clinical vignettes.

Discussion

Patients with undiagnosed signs and/or symptoms present a significant challenge in primary care. In such cases, physicians prefer a work-up to follow-up, with a confidence level in their management strategy that is higher than for their diagnostic hypotheses. There appears to be a stronger perceived need to “do something” than to engage in watchful waiting and follow-up.

Symptoms subside without treatment. Notably, in all the cases that formed the basis for the clinical vignettes used in our survey, the patients’ complaints eventually subsided, with no specific therapy. In some cases of unclear diagnosis, an active work-up may be justified; in others, watchful waiting before testing for unexplained complaints may be preferable.

Action bias. The preference for action over inaction in all the cases presented suggests what has been described as “action bias.”9 The term is derived from sports; in soccer penalty kicks, for example, it applies to goalkeepers who jump before they can see the kick direction and miss.10 According to the norm theory,11 such errors of commission derive from players’ perception that they are expected to act.10 Conversely, in instances in which inaction is the norm, an omission bias prevails, as people tend to judge acts that are harmful as worse than omissions that are even more harmful.10 In medicine, action bias has been found to influence clinical practice and contribute to overuse of both diagnostic testing and procedures.12-14

Gender difference. Gender has been shown to affect self-perception in cognitive bias.15 In a study of confidence levels among undergraduate students, overconfidence was found to be more prevalent among males than females, particularly for incorrect answers.16 This observation may relate to the gender differences in our study in physicians facing diagnostic uncertainty.

Study limitations. Our research was limited by the nature and type of our sample, but because the inclination to act was found in both immigrant and native practitioners, the observation of action bias could be generalizable to all primary care physicians. The clinical vignettes we chose may not be representative of commonly seen cases of medically unexplained symptoms. Also, our questionnaire was not tested beyond at face validity. It is possible, too, that nonresponders would be less inclined to action in the face of uncertainty. With the high (77%) response rate to our survey, however, their inclusion would be unlikely to strikingly alter the results.

Another limitation inherent to the design of our study is that physicians may respond to vignettes in a way that is substantially different than their response in actual practice. In a practice setting, physicians are able to listen to a full narrative and apply various doctor-patient communication tools, which are especially important in the context of unexplained complaints.17 On the other hand, the artificial setting may reduce the fear of litigation. Our observation of greater confidence in the need for action than for the diagnostic hypothesis is consistent with testing overuse in field studies.6 The fact that our survey went only to physicians affiliated with academic centers is another potential limitation, although it is not clear whether these clinicians differ from nonacademic physicians in their approach to unexplained complaints. Finally, the design of this study did not allow us to explore the reasons for action bias, a task that might be addressed in focus groups or interviews.

A closer look at bias. Our findings suggest a need for more in-depth research on potential biases that drive medical overuse, as part of an overall strategy to improve physicians’approach to medically unexplained symptoms.17 Remedies may require training, practice and failure feedback, quality improvement tools, and innovative management strategies.1,18 Uncertain diagnosis appears to be a frequent challenge in primary care settings. Inthe face of uncertainty, weighing the potential harms of overtesting vs follow-up and facilitating an informed decision-making process with the patient may lead to a reduction inaction bias,19 and thus, in the increased testing and higher health care consumption that often result.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mayer Brezis, MD, Center for Clinical Quality & Safety, Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, 91120 Jerusalem, Israel; [email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Steven R. Simon, MD, MPH, for his help with the preparation of this manuscript.

ABSTRACT

Purpose Primary care physicians sometimes encounter patients with clinical complaints that do not fit into a recognized diagnostic pattern. This study was undertaken to assess the way physicians respond to patients whose symptoms are unusual or unexplained—that is, what approach they take in the absence of a working hypothesis.

Methods We surveyed 130 primary care physicians affiliated with 3 academic centers in Israel, presenting 5 clinical vignettes describing patients who had unusual complaints, no clear diagnosis, and no apparent need for urgent care. We asked physicians to provide the most likely diagnosis for each case and to rate their level of confidence in that diagnosis;respondents were also asked to provide a management strategy for each case and their level of confidence in the chosen approach. Finally, we asked the physicians to estimate how many of their own patients have presentations similar to the individuals in the clinical vignettes.

Results Physicians proposed, on average, 22 diagnoses for each case. Most indicated that they would choose action (testing, consulting, sending the patient to the emergency department, or prescribing) rather than follow-up only (87% vs 13%; P<.01). Respondents’ confidence in the management approach they had chosen for all the cases was higher than their confidence in the diagnoses (5.6 vs 4.3, respectively, on a scale of1-10; P<.001). Physicians estimated that 10% to 20% of the patients they see in their practice have unusual or unexplained symptoms that are difficult to diagnose.

Conclusion Uncertain diagnosis is a regular challenge for primary care physicians. In such cases, we found that physicians prefer a workup to follow-up, an inclination consistent with“action bias.”

Physicians in primary care sometimes encounter patients with clinical complaints that do not fit into a recognized diagnostic pattern.1 There are varying reports of the prevalence of such cases, ranging from ≤10% when stringent definitions of medically unexplained symptoms are used2 to as high as 40% to 60% of visits.3,4 Unexplained complaints, which may or may not be related to psychiatric disorders, can significantly contribute to high consumption of health care resources.5 Uncertain diagnoses are associated with increased testing6 and false-positive results, which often lead to more tests and complications.7

When physicians face medically unexplained symptoms, their behavior often differs from the watchful waiting approach some recommend.6 This behavior has been attributed to various factors, such as fear of litigation, greater concern about omission than commission, and perception of patient expectations.5 A study involving young patients suggested bias toward intervention for common pediatric diagnoses.8 Using a similar design of physician responses to clinical vignettes,we sought to evaluate a potential bias toward action, such as testing or referral, for patients with unexplained medical complaints.

Methods

Over several months, 2 of us (AK, IG) identified 60 patients in our practices who had(1) unusual medical complaints, (2) no clear diagnosis, and (3) no apparent need for urgent care. After careful consideration, our team selected 5 cases that best fit the above criteria and reflected the widest spectrum of clinical presentations encountered in primary care settings. After removing identifying patient information, we wrote each case up as a clinical vignette, then presented all 5 cases to primary care physicians affiliated with 3 major academic centers. For each case, respondents were asked to provide:

- the most likely diagnosis and their level of confidence in that diagnosis (on a scale of 1 [no confidence] to 10 [complete confidence])

- a management strategy (testing, consulting with a specialist, referral to the emergency department [ED], prescribing medication, or follow-up only) and their level of confidence in that choice.

Physicians were asked to estimate the frequency of such cases in their practice, as well.

Preparation of the data (cleaning, sorting, and filtering) was carried out using JMPv9.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and analyses were conducted with SPSS v19.0 (IBM,Chicago, Ill). We used descriptive statistics to represent the data and chi-square and ANOVA to compare physicians’ decisions(action vs follow-up). Nonparametric tests were used to compare levels of confidence for diagnosis and management.

Results

We surveyed a convenience sample of 130 primary care physicians affiliated with academic medical centers, 100 of whom responded. Most respondents (62%) were female, and 86% were certified in family medicine. The average age was 45 years (range 30-68 years),with a mean time out of medical school of 17 years (range 1-26 years). Respondents were born in 14 different countries and had undergone medical training in Europe, the United States, or Israel. The diagnoses and management approaches selected for each clinical vignette are presented in TABLE 1. For each case, an average of 22 diagnoses (range 18-25) were proposed. Most physicians (87%; P<.01) indicated that they would choose some type of action (testing, consulting, sending the patient to the ED,or prescribing medication) rather than follow-up alone (TABLE 2). Respondents were able to choose multiple management There appears to be a stronger perceived need to “do something” than to engage in watchful waiting and follow-up.strategies. For all 5 cases, the physicians had more confidence in their patient management approach than in their diagnosis (5.6 vs 4.3;P<.001). On average, men had higher levels of confidence than women for both diagnosis and management (P<.05). Other demographic characteristics, including age, experience, certification, and site of training, were not predictive of confidence level. Respondents estimated that 10% to 20% of their own patients present with unusual and unexplained symptoms, like the patients in the clinical vignettes.

Discussion

Patients with undiagnosed signs and/or symptoms present a significant challenge in primary care. In such cases, physicians prefer a work-up to follow-up, with a confidence level in their management strategy that is higher than for their diagnostic hypotheses. There appears to be a stronger perceived need to “do something” than to engage in watchful waiting and follow-up.

Symptoms subside without treatment. Notably, in all the cases that formed the basis for the clinical vignettes used in our survey, the patients’ complaints eventually subsided, with no specific therapy. In some cases of unclear diagnosis, an active work-up may be justified; in others, watchful waiting before testing for unexplained complaints may be preferable.

Action bias. The preference for action over inaction in all the cases presented suggests what has been described as “action bias.”9 The term is derived from sports; in soccer penalty kicks, for example, it applies to goalkeepers who jump before they can see the kick direction and miss.10 According to the norm theory,11 such errors of commission derive from players’ perception that they are expected to act.10 Conversely, in instances in which inaction is the norm, an omission bias prevails, as people tend to judge acts that are harmful as worse than omissions that are even more harmful.10 In medicine, action bias has been found to influence clinical practice and contribute to overuse of both diagnostic testing and procedures.12-14

Gender difference. Gender has been shown to affect self-perception in cognitive bias.15 In a study of confidence levels among undergraduate students, overconfidence was found to be more prevalent among males than females, particularly for incorrect answers.16 This observation may relate to the gender differences in our study in physicians facing diagnostic uncertainty.

Study limitations. Our research was limited by the nature and type of our sample, but because the inclination to act was found in both immigrant and native practitioners, the observation of action bias could be generalizable to all primary care physicians. The clinical vignettes we chose may not be representative of commonly seen cases of medically unexplained symptoms. Also, our questionnaire was not tested beyond at face validity. It is possible, too, that nonresponders would be less inclined to action in the face of uncertainty. With the high (77%) response rate to our survey, however, their inclusion would be unlikely to strikingly alter the results.

Another limitation inherent to the design of our study is that physicians may respond to vignettes in a way that is substantially different than their response in actual practice. In a practice setting, physicians are able to listen to a full narrative and apply various doctor-patient communication tools, which are especially important in the context of unexplained complaints.17 On the other hand, the artificial setting may reduce the fear of litigation. Our observation of greater confidence in the need for action than for the diagnostic hypothesis is consistent with testing overuse in field studies.6 The fact that our survey went only to physicians affiliated with academic centers is another potential limitation, although it is not clear whether these clinicians differ from nonacademic physicians in their approach to unexplained complaints. Finally, the design of this study did not allow us to explore the reasons for action bias, a task that might be addressed in focus groups or interviews.

A closer look at bias. Our findings suggest a need for more in-depth research on potential biases that drive medical overuse, as part of an overall strategy to improve physicians’approach to medically unexplained symptoms.17 Remedies may require training, practice and failure feedback, quality improvement tools, and innovative management strategies.1,18 Uncertain diagnosis appears to be a frequent challenge in primary care settings. Inthe face of uncertainty, weighing the potential harms of overtesting vs follow-up and facilitating an informed decision-making process with the patient may lead to a reduction inaction bias,19 and thus, in the increased testing and higher health care consumption that often result.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mayer Brezis, MD, Center for Clinical Quality & Safety, Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, 91120 Jerusalem, Israel; [email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Steven R. Simon, MD, MPH, for his help with the preparation of this manuscript.

1. Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: an epidemiological study in seven specialities. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:361-367.

2. Swanson LM, Hamilton JC, Feldman MD. Physician-based estimates of medically unexplained symptoms: a comparison of four case definitions. Fam Pract. 2010;27:487-493.

3. Thomas KB. Temporarily dependent patient in general practice. BMJ. 1974;1:625-626.

4. Jones R, Barraclough K, Dowrick C. When no diagnostic label is applied. BMJ. 2010;340:1302-1304.

5. Todd JW. Wasted resources. Investigations. Lancet. 1984;2:1146-1147.

6. van der Weijden T, van Velsen M, Dinant GJ, et al. Unexplained complaints in general practice: prevalence, patients’ expectations, and professionals’ test-ordering behavior. Med Decis Making. 2003;23:226-231.

7. Brody H. From an ethics of rationing to an ethics of waste avoidance. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1949-1951.

8. Ayanian JZ, Berwick DM. Do physicians have a bias toward action? A classic study revisited. Med Decis Making. 1991;11:154-158.

9. Patt A, Zeckhauser R. Action bias and environmental decisions. J Risk Uncertain. 2000;21:45-72.

10. Bar-Eli M, Azar OH, Ritov I, et al. Action bias among elite soccer goalkeepers: the case of penalty kicks. J Econ Psychol. 2007;28:606-621.

11. Kahneman D, Miller DT. Norm theory: comparing reality to its alternatives. Psychol Rev. 1986;93:136-153.

12. Doust J, Del Mar C. Why do doctors use treatments that do not work? BMJ. 2004;328:474-475.

13. Scott IA. Errors in clinical reasoning: causes and remedial strategies. BMJ. 2009;338:22-25.

14. Cohain JS. Is action bias one of the numerous causes of ‘unnecaesareans’? Midwif Dig. 2009;19:495-499.

15. Beyer S, Bowden EM. Gender differences in self-perceptions: convergent evidence from three measures of accuracy and bias. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1997;23:157-172.

16. Lundeberg MA, Fox PW, Punccohar J. Highly confident but wrong: gender differences and similarities in confidence judgments. J Educ Psychol. 1994;86:114-121.

17. Heijmans M, Olde Hartman TC, van Weel-Baumgarten E, et al. Experts’ opinions on the management of medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. A qualitative analysis of narrative reviews and scientific editorials. Fam Pract. 2011;28:444-455.

18. Croskerry P, Norman G. Overconfidence in clinical decision making. Am J Med. 2008;121(5 suppl):S24-S29.

19. Feinstein AR. The ‘chagrin factor’ and qualitative decision analysis. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1257-1259.

1. Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: an epidemiological study in seven specialities. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:361-367.

2. Swanson LM, Hamilton JC, Feldman MD. Physician-based estimates of medically unexplained symptoms: a comparison of four case definitions. Fam Pract. 2010;27:487-493.

3. Thomas KB. Temporarily dependent patient in general practice. BMJ. 1974;1:625-626.

4. Jones R, Barraclough K, Dowrick C. When no diagnostic label is applied. BMJ. 2010;340:1302-1304.

5. Todd JW. Wasted resources. Investigations. Lancet. 1984;2:1146-1147.

6. van der Weijden T, van Velsen M, Dinant GJ, et al. Unexplained complaints in general practice: prevalence, patients’ expectations, and professionals’ test-ordering behavior. Med Decis Making. 2003;23:226-231.

7. Brody H. From an ethics of rationing to an ethics of waste avoidance. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1949-1951.

8. Ayanian JZ, Berwick DM. Do physicians have a bias toward action? A classic study revisited. Med Decis Making. 1991;11:154-158.

9. Patt A, Zeckhauser R. Action bias and environmental decisions. J Risk Uncertain. 2000;21:45-72.

10. Bar-Eli M, Azar OH, Ritov I, et al. Action bias among elite soccer goalkeepers: the case of penalty kicks. J Econ Psychol. 2007;28:606-621.

11. Kahneman D, Miller DT. Norm theory: comparing reality to its alternatives. Psychol Rev. 1986;93:136-153.

12. Doust J, Del Mar C. Why do doctors use treatments that do not work? BMJ. 2004;328:474-475.

13. Scott IA. Errors in clinical reasoning: causes and remedial strategies. BMJ. 2009;338:22-25.

14. Cohain JS. Is action bias one of the numerous causes of ‘unnecaesareans’? Midwif Dig. 2009;19:495-499.

15. Beyer S, Bowden EM. Gender differences in self-perceptions: convergent evidence from three measures of accuracy and bias. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1997;23:157-172.

16. Lundeberg MA, Fox PW, Punccohar J. Highly confident but wrong: gender differences and similarities in confidence judgments. J Educ Psychol. 1994;86:114-121.

17. Heijmans M, Olde Hartman TC, van Weel-Baumgarten E, et al. Experts’ opinions on the management of medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. A qualitative analysis of narrative reviews and scientific editorials. Fam Pract. 2011;28:444-455.

18. Croskerry P, Norman G. Overconfidence in clinical decision making. Am J Med. 2008;121(5 suppl):S24-S29.

19. Feinstein AR. The ‘chagrin factor’ and qualitative decision analysis. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1257-1259.

Mayer Brezis; MD; MPH; action bias; unexplained complaints; management strategies

Mayer Brezis; MD; MPH; action bias; unexplained complaints; management strategies