User login

The vaginal route is the preferred approach for benign hysterectomy. The most recent Cochrane review of surgical approaches to hysterectomy (abdominal, vaginal, and laparoscopic), which involved more than 3,000 women in 27 randomized controlled trials, shows that vaginal hysterectomy results in fewer complications, shorter hospital stay, and faster recovery and return to normal activity (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006 (2):CD003677). The vaginal approach also provides the best cosmetic result with its single and concealed incision.

Despite strong evidence for the greater advantage of the vaginal approach, there has not been any increase in the number of hysterectomies performed vaginally. In the United States, the rate appears to have declined in 15 years from 24% in 1990 to 22% in 2005, and this decline may be continuing (Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;99:229-34 and Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1041-8). According to an analysis of a national database from more than 500 acute care hospitals, the majority of gynecologic surgeons in United States (more than 80%) perform fewer than five vaginal surgeries in a year (Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;116:1341-7).

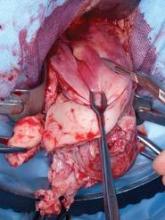

Challenges with exposure, entry into the anterior cul-de-sac, hemostasis, avoidance of ureteral and bladder injury, and removal of the large uterus have been the main stumbling blocks for many surgeons in choosing the vaginal route. I provide, herein, simple techniques, instruments, and devices that can facilitate the performance of the procedure in a safe and efficient manner.

Obtaining exposure

The use of a self-retaining retractor, such as the Magrina-Bookwalter vaginal retractor system (Symmetry Surgical, Nashville, Tenn.) provides consistent and reliable exposure without requiring two surgical assistants at the bedside. Similar to the abdominal self-retractor system, it is attached to the operating table and is designed to fit the contour of the patient’s perineum while in a high lithotomy position. Self-retracting blades of multiple lengths are placed in the four quadrants to maximize room for surgery.

In cases where the introital opening is limited (i.e. = 2.5 cm), such as in nulliparous or menopausal women, a superficial 2- to 3-cm longitudinal incision is performed with bovie cautery in the midline and distal portion of the posterior vaginal wall. This provides additional width to allow placement of the lateral and posterior self-retracting blades.

Additional light from a flexible light source (such as the cystoscopy light) held with a Babcock and a lighted suction irrigator tip (such as Vital Vue, Covidien, Mansfield, Mass.) is extremely helpful in visualization of structures deep within the vagina.

Essential in a vaginal hysterectomy instrument tray are modified deep Deaver retractors that provide additional retraction and visualization particularly in cases of bleeding from pedicles that have retracted to the pelvic sidewall. . A long vaginal pack is also placed to keep loops of bowel out of the operating field. We avoid the use of multiple small sponges that can easily be lost in vaginal cases.

Entry into cul-de-sac

Entry into the anterior cul-de-sac in vaginal hysterectomy can and should be delayed until better descensus of the uterus is obtained. This is achieved with first entering the posterior cul-de-sac, which is often easier to accomplish. To then enter the anterior cul-de-sac, traction is applied posteriorly on the anterior lip of the cervix with the Jacobs tenaculum forceps. The posterior blade is removed to achieve better exposure with a more pronounced angulation of the lower uterine segment.

With ventral traction on the anterior vaginal wall, the bladder is separated from the anterior cervix via sharp dissection with the Mayo curved scissors. The scissor tips are pointed downwards, aimed parallel to the plane of the cervix to reveal the avascular vesicouterine space.

Knowing the anatomy and feel of the tissues is key to mastering entry into the anterior cul-de-sac. Cutting into the cervix will feel tough against the tips of the Metzenbaum scissors, while cutting into the softer beefy-appearing detrusor muscles will manifest with excessive bleeding. The vesicouterine fold is identified as a crescent-shaped peritoneal fold that can be lifted and divided for entry.

In cases where scarring between the bladder and uterus is encountered in patients with multiple previous caesarean sections, dissection is best performed lateral to the midline away from central dense adhesions.

An inability to enter either or both cul-de-sacs should not preclude continuation with the vaginal approach. Securing the uterine arteries can still be accomplished extraperitoneally until better descensus of the uterus is obtained.

Securing vascular pedicles

Achieving hemostasis in vaginal procedures is challenging where there is limited space for placing a suture around the clamp and for securing knots with fingers deep within the vaginal canal. The use of vessel-sealing devices in vaginal hysterectomy overcomes this limitation of tight vaginal access and has proved to be feasible and safe.

Multiple types of energy devices are available, such as PK devices (Gyrus ACMI, Southborough, Mass.), LigaSure instruments (Covidien, Mansfield, Mass.), the Enseal Super Jaw device (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Nokesville, Va.) and Altrus devices (ConMed Electrosurgery, Centennial, Colo.). These devices can be particularly helpful in cases with narrowed introitus and large uterus. The choice of device is surgeon dependent and requires a learning curve.

Gentle traction is placed on the cervix while the device clamp is pushed up against the pedicle, taking care to avoid leaning against any adjacent tissues or retractor blades to avoid thermal injury. Bringing in a suction device quickly dissipates the hot steam that can be generated from the device.

Avoidance of bladder and ureteral injury

Once the vesicouterine space is entered, bladder pillars are gently pushed superiorly and laterally with the index finger to avoid injury during placement of the vessel-sealing clamp. It is imperative that the surgeon is aware of the location of the ureters, which are easily injured, particularly in cases with pelvic prolapse.

The ureters can be palpated with the index finger at 2 o’clock or at 10 o’clock (for the left and right ureter, respectively) against a curved Deaver retractor placed outside the peritoneal cavity on the lateral vaginal wall. Intraoperative cystoscopy should always be performed at the end of the procedure to diagnose inadvertent bladder and ureteral injury.

Removing the Large Uterus

Morcellation can be initiated after the uterine arteries have been sealed and divided on each side. Orientation of the uterus is maintained by placing two Jacobs tenaculi at the 3 o’clock and at 9 o’clock positions on the cervix. The cervix is bivalved to the level of the lower uterine segment.

If the anterior cul-de-sac has not been entered yet, the cervix should be bivalved to a centimeter below the vesicouterine peritoneal fold and morcellation started within the uterus.

Morcellation is performed with a Schroeder tenaculum (Aesculap Inc., Center Valley, Pa.) placed on the myometrium, and a wedge excision is accomplished with a 10 blade. Serial wedges are performed to decompress the uterus. Entry into the anterior cul-de-sac can now be performed easily with better uterine descensus and visualization of the peritoneal fold.

The surgeon should avoid forceful traction on the cervix during morcellation, which can cause the vascular pedicles to avulse.

Depending on the size of the uterus, morcellation can take over an hour. Use of an articulated long scalpel handle (such as the Precise CMK ergonomic knife by LaparoTools, in Metairie, La., which is rounded) can facilitate morcellation with less fatigue.

The surgeon must persist with morcellation as long as descensus of the uterus is continually achieved. An increase in bleeding is encountered when morcellation is near the fundus. At this point, the utero-ovarian pedicles can be identified and secured to finish the procedure.

Mastering the procedure

Simple techniques and new surgical devices are available to facilitate the difficult vaginal hysterectomy. Cases of narrowed introitus, multiple previous caesarean sections, and the large uteri requiring morcellation can be approached vaginally and achieved safely and efficiently with use of the above techniques.

In recognition of the vaginal approach as a minimally invasive procedure, AAGL has provided postgraduate courses in the recent past that incorporate hands-on workshops with the cadaveric model to master the procedure.

Similarly, AAGL has identified five large-volume vaginal centers throughout the country where observership programs are available to practitioners interested in learning the techniques (www.aagl.org). These opportunities allow the surgeon to advance their skills and reincorporate the vaginal hysterectomy into their armamentarium so that patients can benefit from its most minimally invasive approach.

Dr. Kho is associate professor and director of the minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS) fellowship program in the department of medical and surgical gynecology at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, Ariz. She reported that she has no relevant financial disclosures.

The vaginal route is the preferred approach for benign hysterectomy. The most recent Cochrane review of surgical approaches to hysterectomy (abdominal, vaginal, and laparoscopic), which involved more than 3,000 women in 27 randomized controlled trials, shows that vaginal hysterectomy results in fewer complications, shorter hospital stay, and faster recovery and return to normal activity (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006 (2):CD003677). The vaginal approach also provides the best cosmetic result with its single and concealed incision.

Despite strong evidence for the greater advantage of the vaginal approach, there has not been any increase in the number of hysterectomies performed vaginally. In the United States, the rate appears to have declined in 15 years from 24% in 1990 to 22% in 2005, and this decline may be continuing (Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;99:229-34 and Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1041-8). According to an analysis of a national database from more than 500 acute care hospitals, the majority of gynecologic surgeons in United States (more than 80%) perform fewer than five vaginal surgeries in a year (Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;116:1341-7).

Challenges with exposure, entry into the anterior cul-de-sac, hemostasis, avoidance of ureteral and bladder injury, and removal of the large uterus have been the main stumbling blocks for many surgeons in choosing the vaginal route. I provide, herein, simple techniques, instruments, and devices that can facilitate the performance of the procedure in a safe and efficient manner.

Obtaining exposure

The use of a self-retaining retractor, such as the Magrina-Bookwalter vaginal retractor system (Symmetry Surgical, Nashville, Tenn.) provides consistent and reliable exposure without requiring two surgical assistants at the bedside. Similar to the abdominal self-retractor system, it is attached to the operating table and is designed to fit the contour of the patient’s perineum while in a high lithotomy position. Self-retracting blades of multiple lengths are placed in the four quadrants to maximize room for surgery.

In cases where the introital opening is limited (i.e. = 2.5 cm), such as in nulliparous or menopausal women, a superficial 2- to 3-cm longitudinal incision is performed with bovie cautery in the midline and distal portion of the posterior vaginal wall. This provides additional width to allow placement of the lateral and posterior self-retracting blades.

Additional light from a flexible light source (such as the cystoscopy light) held with a Babcock and a lighted suction irrigator tip (such as Vital Vue, Covidien, Mansfield, Mass.) is extremely helpful in visualization of structures deep within the vagina.

Essential in a vaginal hysterectomy instrument tray are modified deep Deaver retractors that provide additional retraction and visualization particularly in cases of bleeding from pedicles that have retracted to the pelvic sidewall. . A long vaginal pack is also placed to keep loops of bowel out of the operating field. We avoid the use of multiple small sponges that can easily be lost in vaginal cases.

Entry into cul-de-sac

Entry into the anterior cul-de-sac in vaginal hysterectomy can and should be delayed until better descensus of the uterus is obtained. This is achieved with first entering the posterior cul-de-sac, which is often easier to accomplish. To then enter the anterior cul-de-sac, traction is applied posteriorly on the anterior lip of the cervix with the Jacobs tenaculum forceps. The posterior blade is removed to achieve better exposure with a more pronounced angulation of the lower uterine segment.

With ventral traction on the anterior vaginal wall, the bladder is separated from the anterior cervix via sharp dissection with the Mayo curved scissors. The scissor tips are pointed downwards, aimed parallel to the plane of the cervix to reveal the avascular vesicouterine space.

Knowing the anatomy and feel of the tissues is key to mastering entry into the anterior cul-de-sac. Cutting into the cervix will feel tough against the tips of the Metzenbaum scissors, while cutting into the softer beefy-appearing detrusor muscles will manifest with excessive bleeding. The vesicouterine fold is identified as a crescent-shaped peritoneal fold that can be lifted and divided for entry.

In cases where scarring between the bladder and uterus is encountered in patients with multiple previous caesarean sections, dissection is best performed lateral to the midline away from central dense adhesions.

An inability to enter either or both cul-de-sacs should not preclude continuation with the vaginal approach. Securing the uterine arteries can still be accomplished extraperitoneally until better descensus of the uterus is obtained.

Securing vascular pedicles

Achieving hemostasis in vaginal procedures is challenging where there is limited space for placing a suture around the clamp and for securing knots with fingers deep within the vaginal canal. The use of vessel-sealing devices in vaginal hysterectomy overcomes this limitation of tight vaginal access and has proved to be feasible and safe.

Multiple types of energy devices are available, such as PK devices (Gyrus ACMI, Southborough, Mass.), LigaSure instruments (Covidien, Mansfield, Mass.), the Enseal Super Jaw device (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Nokesville, Va.) and Altrus devices (ConMed Electrosurgery, Centennial, Colo.). These devices can be particularly helpful in cases with narrowed introitus and large uterus. The choice of device is surgeon dependent and requires a learning curve.

Gentle traction is placed on the cervix while the device clamp is pushed up against the pedicle, taking care to avoid leaning against any adjacent tissues or retractor blades to avoid thermal injury. Bringing in a suction device quickly dissipates the hot steam that can be generated from the device.

Avoidance of bladder and ureteral injury

Once the vesicouterine space is entered, bladder pillars are gently pushed superiorly and laterally with the index finger to avoid injury during placement of the vessel-sealing clamp. It is imperative that the surgeon is aware of the location of the ureters, which are easily injured, particularly in cases with pelvic prolapse.

The ureters can be palpated with the index finger at 2 o’clock or at 10 o’clock (for the left and right ureter, respectively) against a curved Deaver retractor placed outside the peritoneal cavity on the lateral vaginal wall. Intraoperative cystoscopy should always be performed at the end of the procedure to diagnose inadvertent bladder and ureteral injury.

Removing the Large Uterus

Morcellation can be initiated after the uterine arteries have been sealed and divided on each side. Orientation of the uterus is maintained by placing two Jacobs tenaculi at the 3 o’clock and at 9 o’clock positions on the cervix. The cervix is bivalved to the level of the lower uterine segment.

If the anterior cul-de-sac has not been entered yet, the cervix should be bivalved to a centimeter below the vesicouterine peritoneal fold and morcellation started within the uterus.

Morcellation is performed with a Schroeder tenaculum (Aesculap Inc., Center Valley, Pa.) placed on the myometrium, and a wedge excision is accomplished with a 10 blade. Serial wedges are performed to decompress the uterus. Entry into the anterior cul-de-sac can now be performed easily with better uterine descensus and visualization of the peritoneal fold.

The surgeon should avoid forceful traction on the cervix during morcellation, which can cause the vascular pedicles to avulse.

Depending on the size of the uterus, morcellation can take over an hour. Use of an articulated long scalpel handle (such as the Precise CMK ergonomic knife by LaparoTools, in Metairie, La., which is rounded) can facilitate morcellation with less fatigue.

The surgeon must persist with morcellation as long as descensus of the uterus is continually achieved. An increase in bleeding is encountered when morcellation is near the fundus. At this point, the utero-ovarian pedicles can be identified and secured to finish the procedure.

Mastering the procedure

Simple techniques and new surgical devices are available to facilitate the difficult vaginal hysterectomy. Cases of narrowed introitus, multiple previous caesarean sections, and the large uteri requiring morcellation can be approached vaginally and achieved safely and efficiently with use of the above techniques.

In recognition of the vaginal approach as a minimally invasive procedure, AAGL has provided postgraduate courses in the recent past that incorporate hands-on workshops with the cadaveric model to master the procedure.

Similarly, AAGL has identified five large-volume vaginal centers throughout the country where observership programs are available to practitioners interested in learning the techniques (www.aagl.org). These opportunities allow the surgeon to advance their skills and reincorporate the vaginal hysterectomy into their armamentarium so that patients can benefit from its most minimally invasive approach.

Dr. Kho is associate professor and director of the minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS) fellowship program in the department of medical and surgical gynecology at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, Ariz. She reported that she has no relevant financial disclosures.

The vaginal route is the preferred approach for benign hysterectomy. The most recent Cochrane review of surgical approaches to hysterectomy (abdominal, vaginal, and laparoscopic), which involved more than 3,000 women in 27 randomized controlled trials, shows that vaginal hysterectomy results in fewer complications, shorter hospital stay, and faster recovery and return to normal activity (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006 (2):CD003677). The vaginal approach also provides the best cosmetic result with its single and concealed incision.

Despite strong evidence for the greater advantage of the vaginal approach, there has not been any increase in the number of hysterectomies performed vaginally. In the United States, the rate appears to have declined in 15 years from 24% in 1990 to 22% in 2005, and this decline may be continuing (Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;99:229-34 and Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1041-8). According to an analysis of a national database from more than 500 acute care hospitals, the majority of gynecologic surgeons in United States (more than 80%) perform fewer than five vaginal surgeries in a year (Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;116:1341-7).

Challenges with exposure, entry into the anterior cul-de-sac, hemostasis, avoidance of ureteral and bladder injury, and removal of the large uterus have been the main stumbling blocks for many surgeons in choosing the vaginal route. I provide, herein, simple techniques, instruments, and devices that can facilitate the performance of the procedure in a safe and efficient manner.

Obtaining exposure

The use of a self-retaining retractor, such as the Magrina-Bookwalter vaginal retractor system (Symmetry Surgical, Nashville, Tenn.) provides consistent and reliable exposure without requiring two surgical assistants at the bedside. Similar to the abdominal self-retractor system, it is attached to the operating table and is designed to fit the contour of the patient’s perineum while in a high lithotomy position. Self-retracting blades of multiple lengths are placed in the four quadrants to maximize room for surgery.

In cases where the introital opening is limited (i.e. = 2.5 cm), such as in nulliparous or menopausal women, a superficial 2- to 3-cm longitudinal incision is performed with bovie cautery in the midline and distal portion of the posterior vaginal wall. This provides additional width to allow placement of the lateral and posterior self-retracting blades.

Additional light from a flexible light source (such as the cystoscopy light) held with a Babcock and a lighted suction irrigator tip (such as Vital Vue, Covidien, Mansfield, Mass.) is extremely helpful in visualization of structures deep within the vagina.

Essential in a vaginal hysterectomy instrument tray are modified deep Deaver retractors that provide additional retraction and visualization particularly in cases of bleeding from pedicles that have retracted to the pelvic sidewall. . A long vaginal pack is also placed to keep loops of bowel out of the operating field. We avoid the use of multiple small sponges that can easily be lost in vaginal cases.

Entry into cul-de-sac

Entry into the anterior cul-de-sac in vaginal hysterectomy can and should be delayed until better descensus of the uterus is obtained. This is achieved with first entering the posterior cul-de-sac, which is often easier to accomplish. To then enter the anterior cul-de-sac, traction is applied posteriorly on the anterior lip of the cervix with the Jacobs tenaculum forceps. The posterior blade is removed to achieve better exposure with a more pronounced angulation of the lower uterine segment.

With ventral traction on the anterior vaginal wall, the bladder is separated from the anterior cervix via sharp dissection with the Mayo curved scissors. The scissor tips are pointed downwards, aimed parallel to the plane of the cervix to reveal the avascular vesicouterine space.

Knowing the anatomy and feel of the tissues is key to mastering entry into the anterior cul-de-sac. Cutting into the cervix will feel tough against the tips of the Metzenbaum scissors, while cutting into the softer beefy-appearing detrusor muscles will manifest with excessive bleeding. The vesicouterine fold is identified as a crescent-shaped peritoneal fold that can be lifted and divided for entry.

In cases where scarring between the bladder and uterus is encountered in patients with multiple previous caesarean sections, dissection is best performed lateral to the midline away from central dense adhesions.

An inability to enter either or both cul-de-sacs should not preclude continuation with the vaginal approach. Securing the uterine arteries can still be accomplished extraperitoneally until better descensus of the uterus is obtained.

Securing vascular pedicles

Achieving hemostasis in vaginal procedures is challenging where there is limited space for placing a suture around the clamp and for securing knots with fingers deep within the vaginal canal. The use of vessel-sealing devices in vaginal hysterectomy overcomes this limitation of tight vaginal access and has proved to be feasible and safe.

Multiple types of energy devices are available, such as PK devices (Gyrus ACMI, Southborough, Mass.), LigaSure instruments (Covidien, Mansfield, Mass.), the Enseal Super Jaw device (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Nokesville, Va.) and Altrus devices (ConMed Electrosurgery, Centennial, Colo.). These devices can be particularly helpful in cases with narrowed introitus and large uterus. The choice of device is surgeon dependent and requires a learning curve.

Gentle traction is placed on the cervix while the device clamp is pushed up against the pedicle, taking care to avoid leaning against any adjacent tissues or retractor blades to avoid thermal injury. Bringing in a suction device quickly dissipates the hot steam that can be generated from the device.

Avoidance of bladder and ureteral injury

Once the vesicouterine space is entered, bladder pillars are gently pushed superiorly and laterally with the index finger to avoid injury during placement of the vessel-sealing clamp. It is imperative that the surgeon is aware of the location of the ureters, which are easily injured, particularly in cases with pelvic prolapse.

The ureters can be palpated with the index finger at 2 o’clock or at 10 o’clock (for the left and right ureter, respectively) against a curved Deaver retractor placed outside the peritoneal cavity on the lateral vaginal wall. Intraoperative cystoscopy should always be performed at the end of the procedure to diagnose inadvertent bladder and ureteral injury.

Removing the Large Uterus

Morcellation can be initiated after the uterine arteries have been sealed and divided on each side. Orientation of the uterus is maintained by placing two Jacobs tenaculi at the 3 o’clock and at 9 o’clock positions on the cervix. The cervix is bivalved to the level of the lower uterine segment.

If the anterior cul-de-sac has not been entered yet, the cervix should be bivalved to a centimeter below the vesicouterine peritoneal fold and morcellation started within the uterus.

Morcellation is performed with a Schroeder tenaculum (Aesculap Inc., Center Valley, Pa.) placed on the myometrium, and a wedge excision is accomplished with a 10 blade. Serial wedges are performed to decompress the uterus. Entry into the anterior cul-de-sac can now be performed easily with better uterine descensus and visualization of the peritoneal fold.

The surgeon should avoid forceful traction on the cervix during morcellation, which can cause the vascular pedicles to avulse.

Depending on the size of the uterus, morcellation can take over an hour. Use of an articulated long scalpel handle (such as the Precise CMK ergonomic knife by LaparoTools, in Metairie, La., which is rounded) can facilitate morcellation with less fatigue.

The surgeon must persist with morcellation as long as descensus of the uterus is continually achieved. An increase in bleeding is encountered when morcellation is near the fundus. At this point, the utero-ovarian pedicles can be identified and secured to finish the procedure.

Mastering the procedure

Simple techniques and new surgical devices are available to facilitate the difficult vaginal hysterectomy. Cases of narrowed introitus, multiple previous caesarean sections, and the large uteri requiring morcellation can be approached vaginally and achieved safely and efficiently with use of the above techniques.

In recognition of the vaginal approach as a minimally invasive procedure, AAGL has provided postgraduate courses in the recent past that incorporate hands-on workshops with the cadaveric model to master the procedure.

Similarly, AAGL has identified five large-volume vaginal centers throughout the country where observership programs are available to practitioners interested in learning the techniques (www.aagl.org). These opportunities allow the surgeon to advance their skills and reincorporate the vaginal hysterectomy into their armamentarium so that patients can benefit from its most minimally invasive approach.

Dr. Kho is associate professor and director of the minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS) fellowship program in the department of medical and surgical gynecology at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, Ariz. She reported that she has no relevant financial disclosures.