User login

Dear Dr. Mossman,

All the psychiatrists at our clinic agree: It is hard to remember when our patients who take an antipsychotic are due for metabolic monitoring, and it’s even harder to get many of them to follow through with timely blood tests. For many, stopping their medication would be a bad idea. If we keep a patient on an antipsychotic and a metabolic problem results, how serious is our malpractice liability risk?

Submitted by “Dr. V”

Antipsychotics, the mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia,1 put patients at risk of gaining weight and developing metabolic syndrome, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.2 Second-generation antipsychotics are the biggest offenders, but taking a first-generation antipsychotic also can lead to these adverse effects.3

Most psychiatrists are aware of these risks and prefer that their patients do not experience them. However, many psychiatrists neglect proper monitoring or, like Dr. V, find it hard to ensure it happens and thus worry about clinical deterioration if patients stop taking an antipsychotic.4 If you are in the same situation as Dr. V, what medicolegal risks are you facing?

To answer this question, we will:

- review the clinical guidelines and standards for monitoring metabolic effects of antipsychotics

- examine how well (or poorly) physicians adhere to these standards

- discuss what “standard of care” means and how a practice guideline affects the standard effects

- propose how psychiatrists can do better at policing the metabolic effects of antipsychotics.

I’ll be watching you: Following guidelines

Several medical specialty societies have published guidelines for monitoring the metabolic effects of antipsychotics.5-8 These guidelines instruct physicians to obtain a thorough personal and family history; consider metabolic risks when starting a medication; and monitor weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and lipids at various intervals. They also advise referral for management of detected metabolic problems.

Although the recommendations seem clear, many physicians don’t follow them. A 2012 meta-analysis of 48 studies, covering >200,000 antipsychotic-treated patients, showed that baseline measurements of cholesterol, glucose, and weight occurred in <50% of cases.9 A more recent review found that, among adults with a serious mental illness, the rate of lipid testing varied from 6% to 85% and for glucose monitoring, between 18% and 75%.10 In the first years after antipsychotic monitoring guidelines were established, they had only a modest impact on practice,9,11 and some studies showed the guidelines made no difference at all.12-14

Monitoring compliance varies with the type of insurance coverage patients have but remains suboptimal among the commercially insured,11 Medicaid patients,14-16 and veterans.17,18 Studies on antipsychotic treatment in children, adolescents, patients with dementia, and patients with an intellectual disability show insufficient monitoring as well.9,14,17,19-21 The reasons for these gaps are manifold, but one commonly cited factor is uncertainty about whether the psychiatrist or primary care physician should handle monitoring.22

Every claim you stake: The ‘standard of care’

In a medical malpractice case, the party claiming injury must show that the accused physician failed to follow “the generally recognized practices and procedures which would be exercised by ordinary competent practitioners in a defendant doctor’s field of medicine under the same or similar circumstances.”23 In the studies mentioned above,9-14 a large fraction of psychiatrists—many of whom, we can presume, are “competent practitioners”—don’t follow the antipsychotic monitoring guidelines in actual practice. Could failing to follow those guidelines still be the basis for a successful lawsuit?

The answer seems to be ‘yes.’ Published legal decisions describe malpractice lawsuits alleging physicians’ failure to follow antipsychotic guidelines,24,25 and online advertisements show that attorneys believe such cases can generate a payout.26,27 This may seem odd, given what studies say about psychiatrists’ monitoring practices. But determining the “standard of care” in a malpractice case is not an empirical question; it is a legal matter that is decided based on the testimony of expert witnesses.28 Here, customary practice matters, but it’s not the whole story.

Although the standard of care against which courts measure a physician’s actions “is that of a reasonably prudent practitioner …, The degree of care actually practiced by members of the profession is only some evidence of what is reasonably prudent—it is not dispositive.”29 To support their opinion concerning the standard of care, testifying medical witnesses sometimes use practice guidelines. In this case, an explanation of why a particular guideline was chosen is crucial.30

Using guidelines to establish the standard is controversial. On one hand, using guidelines in malpractice litigation allows for some consistency about expectations of practitioners.31,32 Although guidelines are not identical to evidenced-based medicine, they generally reflect an evidence-based expert consensus about sound medical practice. If a hospital uses a guideline to train its employees, the guideline provides the courts with clear information on what should have happened.33,34 Laws in some states allow clinicians to invoke their adherence to a guideline in defense against malpractice claims.35

On the other hand, critics contend that guidelines may not set an accurate standard for the quality of care, nor do they necessarily reflect a proper balance of the conflicting interests of patients and the health care system.36 The American Psychiatric Association states that its practice guidelines “are not intended to serve or be construed as a ‘standard of medical care.’”37

Conformity is not the only measure of prudent practice, and following guidelines does not immunize a clinician from lawsuit if a particular clinical situation demands a different course of action.32 Guidelines can be costly to implement,36 compliance with guidelines generally is low,35 and national guidelines do not necessarily improve the quality of care.38 Last, relying on guidelines to determine the standard of care might stifle innovation or development of alternate approaches by silencing viewpoints.39,40 Table 133-35,39,41 (page 60)summarizes variables that make a guideline more indicative of the standard of care.

Every step you take: Better monitoring

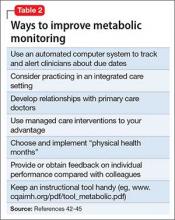

Medical professionals often are slow to update their practice to reflect new knowledge about optimal treatment. But practice guidelines influence the court’s views about the standard of care, and Dr. V’s question shows that he and his colleagues agree that metabolic status needs to be better monitored when patients take antipsychotic drugs. The following discussion and Table 242-45 offer suggestions for how psychiatrists and their practice settings could better accomplish this.

Electronic health records (EHRs). Monitoring health indices often is the largest hurdle that health care professionals face.46 However, large health care systems with EHRs are in a good position to develop and implement automated computer routines that track which patients need monitoring and note due dates, abnormal results, and management interventions.42 Some studies suggest that monitoring rates in both inpatient47 and outpatient48 settings improve with built-in EHR reminders. However, if a system uses too many reminders, the resulting “alert fatigue” will limit their value.22 Providing individual feedback about monitoring practices may enhance physicians’ buy-in to reminder systems.48

Integrated care systems can improve patient outcomes, particularly antipsychotic monitoring. Advantages include shared funding streams, a unified medical record, coordinated scheduling of psychiatric and primary care appointments, and addressing blood-draw refusals.43 More frequent primary care visits make antipsychotic monitoring more likely.11 Ultimately, integrated care could resolve problems related to determining which clinicians are responsible for monitoring and managing adverse metabolic effects.

Third-party payers. Managed care interventions also could improve monitoring rates.44 Prior authorization often requires physicians to obtain appropriate lab work. Insurers might contact physicians with educational interventions, including free webinars, provider alerts, and letters about monitoring rates in their region. Some insurers also provide disease management programs for patients and their caregivers.

Individual and small group practices. Psychiatrists who practice outside a large health care system might designate 2 months each year as “physical health months.” In the “Let’s Get Physical” program,45 physicians were given longer appointment times during these months to address metabolic monitoring, provide education about managing side effects of medication, and encourage better diets and exercise.

Overall, the best techniques might be those implicit to good doctoring: clear and open communication with patients, effective patient education, respect of informed consent, and thorough follow-up.49

1. Mossman D, Steinberg JL. Promoting, prescribing, and pushing pills: understanding the lessons of antipsychotic drug litigation. Michigan St U J Med & Law. 2009;13:263-334.

2. Nasrallah HA, Newcomer JW. Atypical antipsychotics and metabolic dysregulation: evaluating the risk/benefit equation and improving the standard of care. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(5 suppl 1):S7-S14.

3. De Hert M, Schreurs V, Sweers K, et al. Typical and atypical antipsychotics differentially affect long-term incidence rates of the metabolic syndrome in first-episode patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective chart review. Schizophr Res. 2008;101(1-3):295-303.

4. Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG. Clinical handbook of psychiatry and the law. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

5. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):267-272.

6. Pappadopulos E, Macintyre JC II, Crismon ML, et al. Treatment recommendations for the use of antipsychotics for aggressive youth (TRAAY). Part II. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(2):145-161.

7. Pringsheim T, Panagiotopoulos C, Davidson J, et al; CAMESA guideline group. Evidence-based recommendations for monitoring safety of second generation antipsychotics in children and youth [Erratum in: J Can Acad Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(3):1-2]. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(3):218-233.

8. Gleason MM, Egger HL, Emslie GJ, et al. Psychopharmacological treatment for very young children: contexts and guidelines. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(12):1532-1572.

9. Mitchell AJ, Delaffon V, Vancampfort D, et al. Guideline concordant monitoring of metabolic risk in people treated with antipsychotic medication: systematic review and meta-analysis of screening practices. Psychol Med. 2012;42(1):125-147.

10. Baller JB, McGinty EE, Azrin ST, et al. Screening for cardiovascular risk factors in adults with serious mental illness: a review of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:55.

11. Haupt DW, Rosenblatt LC, Kim E, et al. Prevalence and predictors of lipid monitoring in commercially insured patients treated with second-generation antipsychotic agents. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(3):345-353.

12. Dhamane AD, Martin BC, Brixner DI, et al. Metabolic monitoring of patients prescribed second-generation antipsychotics. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(5):360-374.

13. Morrato EH, Newcomer JW, Kamat S, et al. Metabolic screening after the American Diabetes Association’s consensus statement on antipsychotic drugs and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(6):1037-1042.

14. Morrato EH, Druss B, Hartung DM, et al. Metabolic testing rates in 3 state Medicaid programs after FDA warnings and ADA/APA recommendations for second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):17-24.

15. Moeller KE, Rigler SK, Mayorga A, et al. Quality of monitoring for metabolic effects associated with second generation antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia on public insurance. Schizophr Res. 2011;126(1-3):117-123.

16. Barnett M, VonMuenster S, Wehring H, et al. Assessment of monitoring for glucose and lipid dysregulation in adult Medi-Cal patients newly started on antipsychotics. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):9-18.

17. Mittal D, Li C, Viverito K, et al. Monitoring for metabolic side effects among outpatients with dementia receiving antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(9):1147-1153.

18. Hsu C, Ried LD, Bengtson MA, et al. Metabolic monitoring in veterans with schizophrenia-related disorders and treated with second-generation antipsychotics: findings from a Veterans Affairs-based population. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(3):393-400.

19. Raebel MA, Penfold R, McMahon AW, et al. Adherence to guidelines for glucose assessment in starting second-generation antipsychotics. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1308-e1314.

20. Connolly JG, Toomey TJ, Schneeweiss MC. Metabolic monitoring for youths initiating use of second-generation antipsychotics, 2003-2011. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(6):604-609.

21. Teeluckdharry S, Sharma S, O’Rourke E, et al. Monitoring metabolic side effects of atypical antipsychotics in people with an intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil. 2013;17(3):223-235.

22. Lee J, Dalack GW, Casher MI, et al. Persistence of metabolic monitoring for psychiatry inpatients treated with second-generation antipsychotics utilizing a computer-based intervention. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(2):209-213.

23. McCourt v Abernathy, 457 SE2d 603 (SC 1995).

24. Schultz v AstraZeneca Pharma LP, LEXIS 94534, 2006 WL 3797932, (ND Cal 2006).

25. Redmond v AstraZeneca Pharma LP, 492 F Supp 2d 575 (SD Miss 2007).

26. Goguen D. Risperdal, Seroquel, Symbyax, Zyprexa, and other antipsychotic drugs. http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/risperdal-seroquel-symbyax-zyprexa-antipsychotics-29866.html. Accessed April 4, 2016.

27. FreeAdvice staff. Risperdal medical malpractice lawsuits: Risperdal injury lawyer explains what you need to know. http://injury-law.freeadvice.com/injury-law/drug-toxic_chemicals/risperdal.htm. Accessed April 4, 2016.

28. Lewis MK, Gohagan JK, Merenstein DJ. The locality rule and the physician’s dilemma: local medical practices vs the national standard of care. JAMA. 2007;297(23):2633-2637.

29. Harris v Groth, 99 Wn2d 438, 663 P2d 113 (1983).

30. Moffett P, Moore G. The standard of care: legal history and definitions: the bad and good news. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(1):109-112.

31. Taylor C. The use of clinical practice guidelines in determining standard of care. J Legal Med. 2014;35(2):273-290.

32. Bal BS, Brenner LH. Medicolegal sidebar: the law and social values: conformity to norms. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(5):1555-1559.

33. Recupero PR. Clinical practice guidelines as learned treatises: understanding their use as evidence in the courtroom. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(3):290-301.

34. Price v Cleveland Clinic Found, 515 NE2d 931 (Ohio Ct App 1986).

35. Zonana H. Commentary: when is a practice guideline only a guideline? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(3):302-305.

36. Guillod O. Clinical guidelines and professional liability: a short comment from the legal side. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2010;72(3):133-136; discussion 136-137.

37. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the psychiatric evaluation of adults. 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2016.

38. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839-E842.

39. Vermaas AM. Liability in relation to the use of professional medical guidelines. Med Law. 2003;22(2):233-238.

40. Strauss DC, Thomas JM. What does the medical profession mean by “standard of care?”. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):e192-e193.

41. Kozlick D. Clinical practice guidelines and the legal standard of care: warnings, predictions, and interdisciplinary encounters. Health Law J. 2011;19:125-151.

42. Owen RR, Drummond KL, Viverito KM, et al. Monitoring and managing metabolic effects of antipsychotics: a cluster randomized trial of an intervention combining evidence-based quality improvement and external facilitation. Implement Sci. 2013;8:120.

43. Ruiz LM, Damron M, Jones KB, et al. Antipsychotic use and metabolic monitoring in individuals with developmental disabilities served in a Medicaid medical home [published online January 27, 2016]. J Autism Dev Disord. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2712-x.

44. Edelsohn GA, Parthasarathy M, Terhorst L, et al. Measurement of metabolic monitoring in youth and adult Medicaid recipients prescribed antipsychotics. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(9):769-77,777a-777cc.

45. Wilson E, Randall C, Patterson S, et al. Monitoring and management of metabolic abnormalities: mixed-method evaluation of a successful intervention. Australas Psychiatry. 2014;22(3):248-253.

46. Cohn TA, Sernyak MJ. Metabolic monitoring for patients treated with antipsychotic medications. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(8):492-501.

47. DelMonte MT, Bostwick JR, Bess JD, et al. Evaluation of a computer-based intervention to enhance metabolic monitoring in psychiatry inpatients treated with second-generation antipsychotics. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37(6):668-673.

48. Lai CL, Chan HY, Pan YJ, et al. The effectiveness of a computer reminder system for laboratory monitoring of metabolic syndrome in schizophrenic outpatients using second-generation antipsychotics. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(1):25-29.

49. Bailey RK, Adams JB, Unger DM. Atypical antipsychotics: a case study in new era risk management. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12(4):253-258.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

All the psychiatrists at our clinic agree: It is hard to remember when our patients who take an antipsychotic are due for metabolic monitoring, and it’s even harder to get many of them to follow through with timely blood tests. For many, stopping their medication would be a bad idea. If we keep a patient on an antipsychotic and a metabolic problem results, how serious is our malpractice liability risk?

Submitted by “Dr. V”

Antipsychotics, the mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia,1 put patients at risk of gaining weight and developing metabolic syndrome, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.2 Second-generation antipsychotics are the biggest offenders, but taking a first-generation antipsychotic also can lead to these adverse effects.3

Most psychiatrists are aware of these risks and prefer that their patients do not experience them. However, many psychiatrists neglect proper monitoring or, like Dr. V, find it hard to ensure it happens and thus worry about clinical deterioration if patients stop taking an antipsychotic.4 If you are in the same situation as Dr. V, what medicolegal risks are you facing?

To answer this question, we will:

- review the clinical guidelines and standards for monitoring metabolic effects of antipsychotics

- examine how well (or poorly) physicians adhere to these standards

- discuss what “standard of care” means and how a practice guideline affects the standard effects

- propose how psychiatrists can do better at policing the metabolic effects of antipsychotics.

I’ll be watching you: Following guidelines

Several medical specialty societies have published guidelines for monitoring the metabolic effects of antipsychotics.5-8 These guidelines instruct physicians to obtain a thorough personal and family history; consider metabolic risks when starting a medication; and monitor weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and lipids at various intervals. They also advise referral for management of detected metabolic problems.

Although the recommendations seem clear, many physicians don’t follow them. A 2012 meta-analysis of 48 studies, covering >200,000 antipsychotic-treated patients, showed that baseline measurements of cholesterol, glucose, and weight occurred in <50% of cases.9 A more recent review found that, among adults with a serious mental illness, the rate of lipid testing varied from 6% to 85% and for glucose monitoring, between 18% and 75%.10 In the first years after antipsychotic monitoring guidelines were established, they had only a modest impact on practice,9,11 and some studies showed the guidelines made no difference at all.12-14

Monitoring compliance varies with the type of insurance coverage patients have but remains suboptimal among the commercially insured,11 Medicaid patients,14-16 and veterans.17,18 Studies on antipsychotic treatment in children, adolescents, patients with dementia, and patients with an intellectual disability show insufficient monitoring as well.9,14,17,19-21 The reasons for these gaps are manifold, but one commonly cited factor is uncertainty about whether the psychiatrist or primary care physician should handle monitoring.22

Every claim you stake: The ‘standard of care’

In a medical malpractice case, the party claiming injury must show that the accused physician failed to follow “the generally recognized practices and procedures which would be exercised by ordinary competent practitioners in a defendant doctor’s field of medicine under the same or similar circumstances.”23 In the studies mentioned above,9-14 a large fraction of psychiatrists—many of whom, we can presume, are “competent practitioners”—don’t follow the antipsychotic monitoring guidelines in actual practice. Could failing to follow those guidelines still be the basis for a successful lawsuit?

The answer seems to be ‘yes.’ Published legal decisions describe malpractice lawsuits alleging physicians’ failure to follow antipsychotic guidelines,24,25 and online advertisements show that attorneys believe such cases can generate a payout.26,27 This may seem odd, given what studies say about psychiatrists’ monitoring practices. But determining the “standard of care” in a malpractice case is not an empirical question; it is a legal matter that is decided based on the testimony of expert witnesses.28 Here, customary practice matters, but it’s not the whole story.

Although the standard of care against which courts measure a physician’s actions “is that of a reasonably prudent practitioner …, The degree of care actually practiced by members of the profession is only some evidence of what is reasonably prudent—it is not dispositive.”29 To support their opinion concerning the standard of care, testifying medical witnesses sometimes use practice guidelines. In this case, an explanation of why a particular guideline was chosen is crucial.30

Using guidelines to establish the standard is controversial. On one hand, using guidelines in malpractice litigation allows for some consistency about expectations of practitioners.31,32 Although guidelines are not identical to evidenced-based medicine, they generally reflect an evidence-based expert consensus about sound medical practice. If a hospital uses a guideline to train its employees, the guideline provides the courts with clear information on what should have happened.33,34 Laws in some states allow clinicians to invoke their adherence to a guideline in defense against malpractice claims.35

On the other hand, critics contend that guidelines may not set an accurate standard for the quality of care, nor do they necessarily reflect a proper balance of the conflicting interests of patients and the health care system.36 The American Psychiatric Association states that its practice guidelines “are not intended to serve or be construed as a ‘standard of medical care.’”37

Conformity is not the only measure of prudent practice, and following guidelines does not immunize a clinician from lawsuit if a particular clinical situation demands a different course of action.32 Guidelines can be costly to implement,36 compliance with guidelines generally is low,35 and national guidelines do not necessarily improve the quality of care.38 Last, relying on guidelines to determine the standard of care might stifle innovation or development of alternate approaches by silencing viewpoints.39,40 Table 133-35,39,41 (page 60)summarizes variables that make a guideline more indicative of the standard of care.

Every step you take: Better monitoring

Medical professionals often are slow to update their practice to reflect new knowledge about optimal treatment. But practice guidelines influence the court’s views about the standard of care, and Dr. V’s question shows that he and his colleagues agree that metabolic status needs to be better monitored when patients take antipsychotic drugs. The following discussion and Table 242-45 offer suggestions for how psychiatrists and their practice settings could better accomplish this.

Electronic health records (EHRs). Monitoring health indices often is the largest hurdle that health care professionals face.46 However, large health care systems with EHRs are in a good position to develop and implement automated computer routines that track which patients need monitoring and note due dates, abnormal results, and management interventions.42 Some studies suggest that monitoring rates in both inpatient47 and outpatient48 settings improve with built-in EHR reminders. However, if a system uses too many reminders, the resulting “alert fatigue” will limit their value.22 Providing individual feedback about monitoring practices may enhance physicians’ buy-in to reminder systems.48

Integrated care systems can improve patient outcomes, particularly antipsychotic monitoring. Advantages include shared funding streams, a unified medical record, coordinated scheduling of psychiatric and primary care appointments, and addressing blood-draw refusals.43 More frequent primary care visits make antipsychotic monitoring more likely.11 Ultimately, integrated care could resolve problems related to determining which clinicians are responsible for monitoring and managing adverse metabolic effects.

Third-party payers. Managed care interventions also could improve monitoring rates.44 Prior authorization often requires physicians to obtain appropriate lab work. Insurers might contact physicians with educational interventions, including free webinars, provider alerts, and letters about monitoring rates in their region. Some insurers also provide disease management programs for patients and their caregivers.

Individual and small group practices. Psychiatrists who practice outside a large health care system might designate 2 months each year as “physical health months.” In the “Let’s Get Physical” program,45 physicians were given longer appointment times during these months to address metabolic monitoring, provide education about managing side effects of medication, and encourage better diets and exercise.

Overall, the best techniques might be those implicit to good doctoring: clear and open communication with patients, effective patient education, respect of informed consent, and thorough follow-up.49

Dear Dr. Mossman,

All the psychiatrists at our clinic agree: It is hard to remember when our patients who take an antipsychotic are due for metabolic monitoring, and it’s even harder to get many of them to follow through with timely blood tests. For many, stopping their medication would be a bad idea. If we keep a patient on an antipsychotic and a metabolic problem results, how serious is our malpractice liability risk?

Submitted by “Dr. V”

Antipsychotics, the mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia,1 put patients at risk of gaining weight and developing metabolic syndrome, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.2 Second-generation antipsychotics are the biggest offenders, but taking a first-generation antipsychotic also can lead to these adverse effects.3

Most psychiatrists are aware of these risks and prefer that their patients do not experience them. However, many psychiatrists neglect proper monitoring or, like Dr. V, find it hard to ensure it happens and thus worry about clinical deterioration if patients stop taking an antipsychotic.4 If you are in the same situation as Dr. V, what medicolegal risks are you facing?

To answer this question, we will:

- review the clinical guidelines and standards for monitoring metabolic effects of antipsychotics

- examine how well (or poorly) physicians adhere to these standards

- discuss what “standard of care” means and how a practice guideline affects the standard effects

- propose how psychiatrists can do better at policing the metabolic effects of antipsychotics.

I’ll be watching you: Following guidelines

Several medical specialty societies have published guidelines for monitoring the metabolic effects of antipsychotics.5-8 These guidelines instruct physicians to obtain a thorough personal and family history; consider metabolic risks when starting a medication; and monitor weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and lipids at various intervals. They also advise referral for management of detected metabolic problems.

Although the recommendations seem clear, many physicians don’t follow them. A 2012 meta-analysis of 48 studies, covering >200,000 antipsychotic-treated patients, showed that baseline measurements of cholesterol, glucose, and weight occurred in <50% of cases.9 A more recent review found that, among adults with a serious mental illness, the rate of lipid testing varied from 6% to 85% and for glucose monitoring, between 18% and 75%.10 In the first years after antipsychotic monitoring guidelines were established, they had only a modest impact on practice,9,11 and some studies showed the guidelines made no difference at all.12-14

Monitoring compliance varies with the type of insurance coverage patients have but remains suboptimal among the commercially insured,11 Medicaid patients,14-16 and veterans.17,18 Studies on antipsychotic treatment in children, adolescents, patients with dementia, and patients with an intellectual disability show insufficient monitoring as well.9,14,17,19-21 The reasons for these gaps are manifold, but one commonly cited factor is uncertainty about whether the psychiatrist or primary care physician should handle monitoring.22

Every claim you stake: The ‘standard of care’

In a medical malpractice case, the party claiming injury must show that the accused physician failed to follow “the generally recognized practices and procedures which would be exercised by ordinary competent practitioners in a defendant doctor’s field of medicine under the same or similar circumstances.”23 In the studies mentioned above,9-14 a large fraction of psychiatrists—many of whom, we can presume, are “competent practitioners”—don’t follow the antipsychotic monitoring guidelines in actual practice. Could failing to follow those guidelines still be the basis for a successful lawsuit?

The answer seems to be ‘yes.’ Published legal decisions describe malpractice lawsuits alleging physicians’ failure to follow antipsychotic guidelines,24,25 and online advertisements show that attorneys believe such cases can generate a payout.26,27 This may seem odd, given what studies say about psychiatrists’ monitoring practices. But determining the “standard of care” in a malpractice case is not an empirical question; it is a legal matter that is decided based on the testimony of expert witnesses.28 Here, customary practice matters, but it’s not the whole story.

Although the standard of care against which courts measure a physician’s actions “is that of a reasonably prudent practitioner …, The degree of care actually practiced by members of the profession is only some evidence of what is reasonably prudent—it is not dispositive.”29 To support their opinion concerning the standard of care, testifying medical witnesses sometimes use practice guidelines. In this case, an explanation of why a particular guideline was chosen is crucial.30

Using guidelines to establish the standard is controversial. On one hand, using guidelines in malpractice litigation allows for some consistency about expectations of practitioners.31,32 Although guidelines are not identical to evidenced-based medicine, they generally reflect an evidence-based expert consensus about sound medical practice. If a hospital uses a guideline to train its employees, the guideline provides the courts with clear information on what should have happened.33,34 Laws in some states allow clinicians to invoke their adherence to a guideline in defense against malpractice claims.35

On the other hand, critics contend that guidelines may not set an accurate standard for the quality of care, nor do they necessarily reflect a proper balance of the conflicting interests of patients and the health care system.36 The American Psychiatric Association states that its practice guidelines “are not intended to serve or be construed as a ‘standard of medical care.’”37

Conformity is not the only measure of prudent practice, and following guidelines does not immunize a clinician from lawsuit if a particular clinical situation demands a different course of action.32 Guidelines can be costly to implement,36 compliance with guidelines generally is low,35 and national guidelines do not necessarily improve the quality of care.38 Last, relying on guidelines to determine the standard of care might stifle innovation or development of alternate approaches by silencing viewpoints.39,40 Table 133-35,39,41 (page 60)summarizes variables that make a guideline more indicative of the standard of care.

Every step you take: Better monitoring

Medical professionals often are slow to update their practice to reflect new knowledge about optimal treatment. But practice guidelines influence the court’s views about the standard of care, and Dr. V’s question shows that he and his colleagues agree that metabolic status needs to be better monitored when patients take antipsychotic drugs. The following discussion and Table 242-45 offer suggestions for how psychiatrists and their practice settings could better accomplish this.

Electronic health records (EHRs). Monitoring health indices often is the largest hurdle that health care professionals face.46 However, large health care systems with EHRs are in a good position to develop and implement automated computer routines that track which patients need monitoring and note due dates, abnormal results, and management interventions.42 Some studies suggest that monitoring rates in both inpatient47 and outpatient48 settings improve with built-in EHR reminders. However, if a system uses too many reminders, the resulting “alert fatigue” will limit their value.22 Providing individual feedback about monitoring practices may enhance physicians’ buy-in to reminder systems.48

Integrated care systems can improve patient outcomes, particularly antipsychotic monitoring. Advantages include shared funding streams, a unified medical record, coordinated scheduling of psychiatric and primary care appointments, and addressing blood-draw refusals.43 More frequent primary care visits make antipsychotic monitoring more likely.11 Ultimately, integrated care could resolve problems related to determining which clinicians are responsible for monitoring and managing adverse metabolic effects.

Third-party payers. Managed care interventions also could improve monitoring rates.44 Prior authorization often requires physicians to obtain appropriate lab work. Insurers might contact physicians with educational interventions, including free webinars, provider alerts, and letters about monitoring rates in their region. Some insurers also provide disease management programs for patients and their caregivers.

Individual and small group practices. Psychiatrists who practice outside a large health care system might designate 2 months each year as “physical health months.” In the “Let’s Get Physical” program,45 physicians were given longer appointment times during these months to address metabolic monitoring, provide education about managing side effects of medication, and encourage better diets and exercise.

Overall, the best techniques might be those implicit to good doctoring: clear and open communication with patients, effective patient education, respect of informed consent, and thorough follow-up.49

1. Mossman D, Steinberg JL. Promoting, prescribing, and pushing pills: understanding the lessons of antipsychotic drug litigation. Michigan St U J Med & Law. 2009;13:263-334.

2. Nasrallah HA, Newcomer JW. Atypical antipsychotics and metabolic dysregulation: evaluating the risk/benefit equation and improving the standard of care. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(5 suppl 1):S7-S14.

3. De Hert M, Schreurs V, Sweers K, et al. Typical and atypical antipsychotics differentially affect long-term incidence rates of the metabolic syndrome in first-episode patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective chart review. Schizophr Res. 2008;101(1-3):295-303.

4. Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG. Clinical handbook of psychiatry and the law. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

5. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):267-272.

6. Pappadopulos E, Macintyre JC II, Crismon ML, et al. Treatment recommendations for the use of antipsychotics for aggressive youth (TRAAY). Part II. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(2):145-161.

7. Pringsheim T, Panagiotopoulos C, Davidson J, et al; CAMESA guideline group. Evidence-based recommendations for monitoring safety of second generation antipsychotics in children and youth [Erratum in: J Can Acad Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(3):1-2]. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(3):218-233.

8. Gleason MM, Egger HL, Emslie GJ, et al. Psychopharmacological treatment for very young children: contexts and guidelines. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(12):1532-1572.

9. Mitchell AJ, Delaffon V, Vancampfort D, et al. Guideline concordant monitoring of metabolic risk in people treated with antipsychotic medication: systematic review and meta-analysis of screening practices. Psychol Med. 2012;42(1):125-147.

10. Baller JB, McGinty EE, Azrin ST, et al. Screening for cardiovascular risk factors in adults with serious mental illness: a review of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:55.

11. Haupt DW, Rosenblatt LC, Kim E, et al. Prevalence and predictors of lipid monitoring in commercially insured patients treated with second-generation antipsychotic agents. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(3):345-353.

12. Dhamane AD, Martin BC, Brixner DI, et al. Metabolic monitoring of patients prescribed second-generation antipsychotics. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(5):360-374.

13. Morrato EH, Newcomer JW, Kamat S, et al. Metabolic screening after the American Diabetes Association’s consensus statement on antipsychotic drugs and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(6):1037-1042.

14. Morrato EH, Druss B, Hartung DM, et al. Metabolic testing rates in 3 state Medicaid programs after FDA warnings and ADA/APA recommendations for second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):17-24.

15. Moeller KE, Rigler SK, Mayorga A, et al. Quality of monitoring for metabolic effects associated with second generation antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia on public insurance. Schizophr Res. 2011;126(1-3):117-123.

16. Barnett M, VonMuenster S, Wehring H, et al. Assessment of monitoring for glucose and lipid dysregulation in adult Medi-Cal patients newly started on antipsychotics. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):9-18.

17. Mittal D, Li C, Viverito K, et al. Monitoring for metabolic side effects among outpatients with dementia receiving antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(9):1147-1153.

18. Hsu C, Ried LD, Bengtson MA, et al. Metabolic monitoring in veterans with schizophrenia-related disorders and treated with second-generation antipsychotics: findings from a Veterans Affairs-based population. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(3):393-400.

19. Raebel MA, Penfold R, McMahon AW, et al. Adherence to guidelines for glucose assessment in starting second-generation antipsychotics. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1308-e1314.

20. Connolly JG, Toomey TJ, Schneeweiss MC. Metabolic monitoring for youths initiating use of second-generation antipsychotics, 2003-2011. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(6):604-609.

21. Teeluckdharry S, Sharma S, O’Rourke E, et al. Monitoring metabolic side effects of atypical antipsychotics in people with an intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil. 2013;17(3):223-235.

22. Lee J, Dalack GW, Casher MI, et al. Persistence of metabolic monitoring for psychiatry inpatients treated with second-generation antipsychotics utilizing a computer-based intervention. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(2):209-213.

23. McCourt v Abernathy, 457 SE2d 603 (SC 1995).

24. Schultz v AstraZeneca Pharma LP, LEXIS 94534, 2006 WL 3797932, (ND Cal 2006).

25. Redmond v AstraZeneca Pharma LP, 492 F Supp 2d 575 (SD Miss 2007).

26. Goguen D. Risperdal, Seroquel, Symbyax, Zyprexa, and other antipsychotic drugs. http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/risperdal-seroquel-symbyax-zyprexa-antipsychotics-29866.html. Accessed April 4, 2016.

27. FreeAdvice staff. Risperdal medical malpractice lawsuits: Risperdal injury lawyer explains what you need to know. http://injury-law.freeadvice.com/injury-law/drug-toxic_chemicals/risperdal.htm. Accessed April 4, 2016.

28. Lewis MK, Gohagan JK, Merenstein DJ. The locality rule and the physician’s dilemma: local medical practices vs the national standard of care. JAMA. 2007;297(23):2633-2637.

29. Harris v Groth, 99 Wn2d 438, 663 P2d 113 (1983).

30. Moffett P, Moore G. The standard of care: legal history and definitions: the bad and good news. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(1):109-112.

31. Taylor C. The use of clinical practice guidelines in determining standard of care. J Legal Med. 2014;35(2):273-290.

32. Bal BS, Brenner LH. Medicolegal sidebar: the law and social values: conformity to norms. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(5):1555-1559.

33. Recupero PR. Clinical practice guidelines as learned treatises: understanding their use as evidence in the courtroom. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(3):290-301.

34. Price v Cleveland Clinic Found, 515 NE2d 931 (Ohio Ct App 1986).

35. Zonana H. Commentary: when is a practice guideline only a guideline? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(3):302-305.

36. Guillod O. Clinical guidelines and professional liability: a short comment from the legal side. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2010;72(3):133-136; discussion 136-137.

37. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the psychiatric evaluation of adults. 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2016.

38. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839-E842.

39. Vermaas AM. Liability in relation to the use of professional medical guidelines. Med Law. 2003;22(2):233-238.

40. Strauss DC, Thomas JM. What does the medical profession mean by “standard of care?”. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):e192-e193.

41. Kozlick D. Clinical practice guidelines and the legal standard of care: warnings, predictions, and interdisciplinary encounters. Health Law J. 2011;19:125-151.

42. Owen RR, Drummond KL, Viverito KM, et al. Monitoring and managing metabolic effects of antipsychotics: a cluster randomized trial of an intervention combining evidence-based quality improvement and external facilitation. Implement Sci. 2013;8:120.

43. Ruiz LM, Damron M, Jones KB, et al. Antipsychotic use and metabolic monitoring in individuals with developmental disabilities served in a Medicaid medical home [published online January 27, 2016]. J Autism Dev Disord. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2712-x.

44. Edelsohn GA, Parthasarathy M, Terhorst L, et al. Measurement of metabolic monitoring in youth and adult Medicaid recipients prescribed antipsychotics. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(9):769-77,777a-777cc.

45. Wilson E, Randall C, Patterson S, et al. Monitoring and management of metabolic abnormalities: mixed-method evaluation of a successful intervention. Australas Psychiatry. 2014;22(3):248-253.

46. Cohn TA, Sernyak MJ. Metabolic monitoring for patients treated with antipsychotic medications. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(8):492-501.

47. DelMonte MT, Bostwick JR, Bess JD, et al. Evaluation of a computer-based intervention to enhance metabolic monitoring in psychiatry inpatients treated with second-generation antipsychotics. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37(6):668-673.

48. Lai CL, Chan HY, Pan YJ, et al. The effectiveness of a computer reminder system for laboratory monitoring of metabolic syndrome in schizophrenic outpatients using second-generation antipsychotics. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(1):25-29.

49. Bailey RK, Adams JB, Unger DM. Atypical antipsychotics: a case study in new era risk management. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12(4):253-258.

1. Mossman D, Steinberg JL. Promoting, prescribing, and pushing pills: understanding the lessons of antipsychotic drug litigation. Michigan St U J Med & Law. 2009;13:263-334.

2. Nasrallah HA, Newcomer JW. Atypical antipsychotics and metabolic dysregulation: evaluating the risk/benefit equation and improving the standard of care. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(5 suppl 1):S7-S14.

3. De Hert M, Schreurs V, Sweers K, et al. Typical and atypical antipsychotics differentially affect long-term incidence rates of the metabolic syndrome in first-episode patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective chart review. Schizophr Res. 2008;101(1-3):295-303.

4. Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG. Clinical handbook of psychiatry and the law. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

5. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):267-272.

6. Pappadopulos E, Macintyre JC II, Crismon ML, et al. Treatment recommendations for the use of antipsychotics for aggressive youth (TRAAY). Part II. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(2):145-161.

7. Pringsheim T, Panagiotopoulos C, Davidson J, et al; CAMESA guideline group. Evidence-based recommendations for monitoring safety of second generation antipsychotics in children and youth [Erratum in: J Can Acad Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(3):1-2]. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(3):218-233.

8. Gleason MM, Egger HL, Emslie GJ, et al. Psychopharmacological treatment for very young children: contexts and guidelines. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(12):1532-1572.

9. Mitchell AJ, Delaffon V, Vancampfort D, et al. Guideline concordant monitoring of metabolic risk in people treated with antipsychotic medication: systematic review and meta-analysis of screening practices. Psychol Med. 2012;42(1):125-147.

10. Baller JB, McGinty EE, Azrin ST, et al. Screening for cardiovascular risk factors in adults with serious mental illness: a review of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:55.

11. Haupt DW, Rosenblatt LC, Kim E, et al. Prevalence and predictors of lipid monitoring in commercially insured patients treated with second-generation antipsychotic agents. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(3):345-353.

12. Dhamane AD, Martin BC, Brixner DI, et al. Metabolic monitoring of patients prescribed second-generation antipsychotics. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(5):360-374.

13. Morrato EH, Newcomer JW, Kamat S, et al. Metabolic screening after the American Diabetes Association’s consensus statement on antipsychotic drugs and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(6):1037-1042.

14. Morrato EH, Druss B, Hartung DM, et al. Metabolic testing rates in 3 state Medicaid programs after FDA warnings and ADA/APA recommendations for second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):17-24.

15. Moeller KE, Rigler SK, Mayorga A, et al. Quality of monitoring for metabolic effects associated with second generation antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia on public insurance. Schizophr Res. 2011;126(1-3):117-123.

16. Barnett M, VonMuenster S, Wehring H, et al. Assessment of monitoring for glucose and lipid dysregulation in adult Medi-Cal patients newly started on antipsychotics. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):9-18.

17. Mittal D, Li C, Viverito K, et al. Monitoring for metabolic side effects among outpatients with dementia receiving antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(9):1147-1153.

18. Hsu C, Ried LD, Bengtson MA, et al. Metabolic monitoring in veterans with schizophrenia-related disorders and treated with second-generation antipsychotics: findings from a Veterans Affairs-based population. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(3):393-400.

19. Raebel MA, Penfold R, McMahon AW, et al. Adherence to guidelines for glucose assessment in starting second-generation antipsychotics. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1308-e1314.

20. Connolly JG, Toomey TJ, Schneeweiss MC. Metabolic monitoring for youths initiating use of second-generation antipsychotics, 2003-2011. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(6):604-609.

21. Teeluckdharry S, Sharma S, O’Rourke E, et al. Monitoring metabolic side effects of atypical antipsychotics in people with an intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil. 2013;17(3):223-235.

22. Lee J, Dalack GW, Casher MI, et al. Persistence of metabolic monitoring for psychiatry inpatients treated with second-generation antipsychotics utilizing a computer-based intervention. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(2):209-213.

23. McCourt v Abernathy, 457 SE2d 603 (SC 1995).

24. Schultz v AstraZeneca Pharma LP, LEXIS 94534, 2006 WL 3797932, (ND Cal 2006).

25. Redmond v AstraZeneca Pharma LP, 492 F Supp 2d 575 (SD Miss 2007).

26. Goguen D. Risperdal, Seroquel, Symbyax, Zyprexa, and other antipsychotic drugs. http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/risperdal-seroquel-symbyax-zyprexa-antipsychotics-29866.html. Accessed April 4, 2016.

27. FreeAdvice staff. Risperdal medical malpractice lawsuits: Risperdal injury lawyer explains what you need to know. http://injury-law.freeadvice.com/injury-law/drug-toxic_chemicals/risperdal.htm. Accessed April 4, 2016.

28. Lewis MK, Gohagan JK, Merenstein DJ. The locality rule and the physician’s dilemma: local medical practices vs the national standard of care. JAMA. 2007;297(23):2633-2637.

29. Harris v Groth, 99 Wn2d 438, 663 P2d 113 (1983).

30. Moffett P, Moore G. The standard of care: legal history and definitions: the bad and good news. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(1):109-112.

31. Taylor C. The use of clinical practice guidelines in determining standard of care. J Legal Med. 2014;35(2):273-290.

32. Bal BS, Brenner LH. Medicolegal sidebar: the law and social values: conformity to norms. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(5):1555-1559.

33. Recupero PR. Clinical practice guidelines as learned treatises: understanding their use as evidence in the courtroom. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(3):290-301.

34. Price v Cleveland Clinic Found, 515 NE2d 931 (Ohio Ct App 1986).

35. Zonana H. Commentary: when is a practice guideline only a guideline? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(3):302-305.

36. Guillod O. Clinical guidelines and professional liability: a short comment from the legal side. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2010;72(3):133-136; discussion 136-137.

37. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the psychiatric evaluation of adults. 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2016.

38. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839-E842.

39. Vermaas AM. Liability in relation to the use of professional medical guidelines. Med Law. 2003;22(2):233-238.

40. Strauss DC, Thomas JM. What does the medical profession mean by “standard of care?”. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):e192-e193.

41. Kozlick D. Clinical practice guidelines and the legal standard of care: warnings, predictions, and interdisciplinary encounters. Health Law J. 2011;19:125-151.

42. Owen RR, Drummond KL, Viverito KM, et al. Monitoring and managing metabolic effects of antipsychotics: a cluster randomized trial of an intervention combining evidence-based quality improvement and external facilitation. Implement Sci. 2013;8:120.

43. Ruiz LM, Damron M, Jones KB, et al. Antipsychotic use and metabolic monitoring in individuals with developmental disabilities served in a Medicaid medical home [published online January 27, 2016]. J Autism Dev Disord. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2712-x.

44. Edelsohn GA, Parthasarathy M, Terhorst L, et al. Measurement of metabolic monitoring in youth and adult Medicaid recipients prescribed antipsychotics. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(9):769-77,777a-777cc.

45. Wilson E, Randall C, Patterson S, et al. Monitoring and management of metabolic abnormalities: mixed-method evaluation of a successful intervention. Australas Psychiatry. 2014;22(3):248-253.

46. Cohn TA, Sernyak MJ. Metabolic monitoring for patients treated with antipsychotic medications. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(8):492-501.

47. DelMonte MT, Bostwick JR, Bess JD, et al. Evaluation of a computer-based intervention to enhance metabolic monitoring in psychiatry inpatients treated with second-generation antipsychotics. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37(6):668-673.

48. Lai CL, Chan HY, Pan YJ, et al. The effectiveness of a computer reminder system for laboratory monitoring of metabolic syndrome in schizophrenic outpatients using second-generation antipsychotics. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(1):25-29.

49. Bailey RK, Adams JB, Unger DM. Atypical antipsychotics: a case study in new era risk management. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12(4):253-258.