User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

When does benign shyness become social anxiety, a treatable disorder?

Since the appearance of social anxiety disorder (SAD) in the DSM-III in 1980, research on its prevalence, characteristics, and treatment have grown (Box 11,2). In addition to the name, the definition of SAD has changed over the years; as a result, its prevalence has increased in recent cohort studies. This has led to debate over whether the experience of shyness is being over-pathologized, or whether SAD has been underdiagnosed in earlier decades. Those who argue that shyness is being over-pathologized note that it is a normal human experience that has evolutionary functions (eg, preventing engagement in harmful social relationships3). Others argue that a high degree of shyness is not beneficial in terms of evolution because it causes the individual to be shunned, so to speak, by society.4

Why worry about ‘over-pathologizing’?

The medicalization of shyness might be a reflection of Western societal values of assertiveness and gregariousness; other societies that value modesty and reticence do not over-pathologize shyness.5 It is important not to assume that someone who is shy necessarily has a “pathologic” level of social anxiety, especially because some people who are shy view that condition as a positive quality, much like sensitivity and conscientiousness.5

The broader issue of what constitutes a mental disorder arises in this debate. A “disorder” is a socially constructed label that describes a set of symptoms occurring together and its associated behaviors, not a real entity with etiological homogeneity.6 Labeling emotional problems “disordered” assumes that happiness is the natural homeostatic state, and distressing emotional states are abnormal and need to be changed.7 A diagnostic label can help improve communication and understand maladaptive behaviors; if that label is reified, however, it can lead to assumptions that the etiology, course, and treatment response are known. Proponents of the diagnostic psychiatric nomenclature have acknowledged the dangers of over-pathologizing normal experiences of living (such as fear) by way of diagnostic labeling.8

Determining when shyness becomes a clinically significant problem—what we call SAD here—demands a delicate distinction that has important implications for treatment. On one hand, if shyness is over-pathologized, persons who neither desire nor need treatment might be subjected to unnecessary and costly intervention. On the other hand, if SAD is underdiagnosed, some persons will not receive treatment that might be beneficial to them.

In this article, we review the similarities and differences between shyness and SAD, and provide recommendations for determining when shyness becomes a more clinically significant problem. We also highlight the importance of this distinction as it pertains to management, and provide suggestions for treatment approaches.

SAD: Definition, prevalence

SAD is defined as a significant fear of embarrassment or humiliation in social or performance-based situations, to a point at which the affected person often avoids these situations or endures them only with a high level of distress9 (Table 1, and Box 2). SAD can be distinguished from other anxiety disorders based on the source and content of the fear (ie, the source being social interaction or performance situations, and the content being a fear that one will show a behavior that will cause embarrassment). SAD also should be distinguished from autism spectrum disorders, in which persons have limited social communication capabilities and inadequate age-appropriate social relationships.

SAD is most highly comorbid with mood and anxiety disorders, with rates of at least 30% in clinical samples.10 The disorder also is highly comorbid with avoidant personality disorder—to a point at which it is argued that they are one and the same disorder.11

As with other psychiatric disorders, anxiety must cause significant impairment or distress. What constitutes significant impairment or distress is subjective, and the arbitrary nature of this criterion can influence estimates of the prevalence of SAD. For example, prevalence ranges as widely as 1.9% to 20.4% when different cut-offs are used for distress ratings and the number of impaired domains.12

The prevalence of SAD varies from 1 epidemiological study to another (ie, the Epidemiological Catchment Area [ECA] Study and the National Comorbidity Survey [NCS])—in part, a consequence of the differing definitions of significant impairment or distress. The ECA study assessed the clinical significance of each symptom in anxiety disorders; the NCS assessed overall clinical significance of the disorder. When the clinical significance criterion was applied at the symptom level to the NCS dataset (as was done in the ECA study), 1-year prevalence decreased by 50% (from 7.4% to 3.7%).13 The manner in which significant impairment or distress is defined (ie, conservatively or liberally) impacts whether social anxiety symptoms are classified as disordered or non-disordered.

Shyness: Definition, prevalence

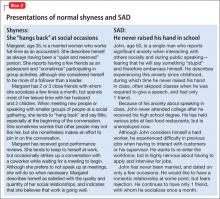

Shyness often refers to 1) anxiety, inhibition, reticence, or a combination of these findings, in social and interpersonal situations, and 2) a fear of negative evaluation by others.14 It is a normal facet of personality that combines the experience of social anxiety and inhibited behavior,15 and also has been described as a stable temperament.16 Shyness is common; in the NCS study,17 26% of women and 19% of men characterized themselves as “very shy”; in the NCS Adolescent study,18 nearly 50% of adolescents self-identified as shy.

Persons who are shy tend to self-report greater social anxiety and embarrassment in social situations than non-shy persons do; they also might experience greater autonomic reactivity—especially blushing—in social or performance situations.15 Furthermore, shy persons are more likely to have axis I comorbidity and traits of introversion and neuroticism, compared with non-shy persons.14

Research suggests that temperament and behavioral inhibition are risk factors for mood and anxiety disorders, and appear to have a particularly strong relationship with SAD.19 A recent prospective study showed that shyness tends to increase steeply in toddlerhood, then stabilizes in childhood. Shyness in childhood—but not toddlerhood—is predictive of anxiety, depression, and poorer social skills in adolescence.20

A qualitative, or just quantitative, difference?

It is clear that SAD and shyness share several features—including anxiety and embarrassment—in social interactions. This raises a question: Are SAD and shyness distinct qualitatively, or do they represent points along a continuum, with SAD being an extreme form of shyness?

Continuum hypothesis. Support for the continuum hypothesis includes evidence that SAD and shyness share several features, including autonomic arousal, deficits in social skills (eg, aversion of gaze, difficulty initiating and maintaining conversation), avoidance of social situations, and fear of negative evaluation.21,22 In addition, both shyness and SAD are highly heritable,23 and mothers of shy children have a significantly higher rate of SAD than non-shy children do.24 No familial or genetic studies have compared heritability and familial aggregation in shyness and SAD.

According to the continuum hypothesis, if SAD is an extreme form of shyness, all (or nearly all) persons who have a diagnosis of SAD also would be characterized as shy. However, only approximately one-half of such persons report having been shy in childhood.17 Less than one-quarter of shy persons meet criteria for SAD.14,18 Because many persons who are shy do not meet criteria for SAD, and many who have SAD were not considered shy earlier in life, it has been suggested that this supports a qualitative distinction.

Qualitative distinctiveness. Despite having similarities, several features distinguish the experience of SAD from that of shyness. Compared with shyness, a SAD diagnosis is associated with:

- greater comorbidity

- greater severity of avoidance and impairment

- poorer quality of life.18,21,25

Studies that compared SAD, shyness without SAD, and non-shyness have shown that the shyness without SAD group more closely resembles the non-shy group than the SAD group—particularly with regard to impairment, presence of substance use, and other behavioral problems.18,25

Given the evidence, experts have concluded that shyness and a SAD diagnosis are overlapping yet different constructs that encapsulate qualitative and quantitative differences.25 There is a spectrum of shyness that ranges from a normative level to a higher level that overlaps the experience of SAD, but the 2 states represent different constructs.25

Guidance for making an assessment. Because of similarities in anxiety, embarrassment, and other symptoms in social situations, the best way to determine whether shyness crosses the line into a clinically significant problem is to assess the severity of the anxiety and associated degree of impairment and distress. More severe anxiety paired with distress about having anxiety and significant impairment in multiple areas of functioning might indicate more problematic social anxiety—a diagnosis of SAD—not just “normal” shyness.

It is important to take into account the environmental and cultural context of a patient’s distress and impairment because these features might fall within a normal range, given immediate circumstances (such as speaking in front of a large audience when one is not normally called on to do so, to a degree that does not interfere with general social functioning6).

What is considered a normative range depends on the developmental stage:

- Among children, a greater level of shyness might be considered more normative when it manifests during developmental stages in which separation anxiety appears.

- Among adolescents, a greater level of shyness might be considered normative especially during early adolescence (when social relationships become more important), and during times of transition (ie, entering high school).

- In adulthood, a greater level of normative shyness or social anxiety might be present during a major life change (eg, beginning to date again after the loss of a lengthy marriage or romantic relationship).

Assessment tools

Assessment tools can help you differentiate normal shyness from SAD. Several empirically-validated rating scales exist, including clinician-rated and self-report scales.

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale26 rates the severity of fear and avoidance in a variety of social interaction and performance-based situations. However, it was developed primarily as a clinician-rated scale and might be more burdensome to complete in practice. In addition, it does not provide cut-offs to indicate when more clinically significant anxiety might be likely.

Clinically Useful Social Anxiety Disorder Outcome Scale (CUSADOS)27 and Mini-Social Phobia Inventory (Mini-SPIN)28 are brief self-report scales that provide cut-offs to suggest further assessment is warranted. A cut-off score of 16 on the CUSADOS suggests the presence of SAD with 73% diagnostic efficiency.

One disadvantage to relying on a rating scale alone is the narrow focus on symptoms. Given that shyness and SAD share similar symptoms, it is necessary to assess the degree of impairment related to these symptoms to determine whether the problem is clinically significant. The overly narrow focus on symptoms utilized by the biomedical approach has been criticized for contributing to the medicalization of normal shyness.5

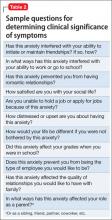

Diagnostic interviews, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders29 include sections on SAD that assess avoidance and impairment/distress associated with anxiety. Because these interviews may increase the time burden during an office visit, there are several general questions outside of a structured interview that you can ask, such as: “Has this anxiety interfered with your ability to initiate or maintain friendships? If so, how?” (Table 2). Persons with clinically significant social anxiety, rather than shyness, tend to report greater effects on their relationships and on work or school performance, as well as greater distress about having that anxiety.

Treatment approaches based on distinctions

Exercise care in making the distinction between normal shyness and dysfunctional and impairing levels of anxiety characteristic of SAD, because persons who display normal shyness but who are overdiagnosed might feel stigmatized by a diagnostic label.5 Also, overpathologizing shyness takes what is a social problem out of context, and could promote treatment strategies that might not be helpful or effective.30

Unnecessary diagnosis might lead to unnecessary treatment, such as prescribing an antidepressant or benzodiazepine. Avoiding such a situation is important, because of the side effects associated with medication and the potential for dependence and withdrawal effects with benzodiazepines.

Persons who exhibit normal shyness do not require medical treatment and, often, do not want it. However, some people may be interested in improving their ability to function in social interactions. Self-help approaches or brief psychotherapy (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) should be the first step—and might be all that is necessary.

The opposite side of the problem. Under-recognition of clinically significant social anxiety can lead to under-treatment, which is common even in patients with a SAD diagnosis.31 Treatment options include CBT, medication, and CBT combined with medication (Table 3):

- several studies have demonstrated the short- and long-term efficacy of CBT alone for SAD

- medication alone has been efficacious in the short-term, but less efficacious than CBT in the long-term

- combined treatment also has been shown to be more efficacious than CBT or medication alone in the short-term

- there is evidence to suggest that CBT alone is more efficacious in the long-term compared with combined treatment.a

CBT is recommended as an appropriate first-line option, especially for mild and moderate SAD; it is the preferred initial treatment option of the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). For more severe presentations (such as the presence of comorbidity) or when a patient did not respond to an adequate course of CBT, combined treatment might be an option—the goal being to taper the medication and continue CBT as a longer-term treatment. Research has shown that continuing CBT while discontinuing medication helps prevent relapse.32,33

Appropriate pharmacotherapy options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.34 Increasingly, benzodiazepines are considered less desirable; they are not recommended for routine use in SAD in the NICE guidelines. Those guidelines call for continuing pharmacotherapy for 6 months when a patient responds to treatment within 3 months, then discontinuing medication with the aid of CBT.

Bottom Line

The severity of anxiety and associated impairment and distress are the main variables that differentiate normal shyness and clinically significant social anxiety. Taking care not to over-pathologize normal shyness and common social anxiety concerns or underdiagnose severe, impairing social anxiety disorder has important implications for treatment—and for whether a patient needs treatment at all.

Related Resources

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment, and treatment of social anxiety disorder. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/cg159.

• Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, eds. Social anxiety: clinical, developmental, and social perspectives, 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 2010.

• The Shyness Institute. www.shyness.com.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax Clonazepam • Klonopin Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox Paroxetine • Paxil Phenelzine • Nardil

Sertraline • Zoloft Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

Kristy L. Dalrymple, PhD, discusses, treating social anxiety disorder. Dr. Dalrymple is Staff Psychologist, Department of Psychiatry, Rhode Island Hospital, and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

1. Bruce LC, Coles ME, Heimberg RG. Social phobia and social anxiety disorder: effect of disorder name on recommendation for treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):538.

2. Bögels SM, Alden L, Beidel DC, et al. Social anxiety disorder: questions and answers for the DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:168-189.

3. Wakefield JC, Horwitz AV, Schmitz MF. Are we overpathologizing the socially anxious? Social phobia from a harmful dysfunction perspective. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(6):317-319.

4. Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Justifying the diagnostic status of social phobia: a reply to Wakefield, Horwitz, and Schmitz. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(6):320-323.

5. Scott S. The medicalisation of shyness: from social misfits to social fitness. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2006;28(2):133-153.

6. Wakefield JC. The DSM-5 debate over the bereavement exclusion: psychiatric diagnosis and the future of empirically supported treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013; 33(7):825-845.

7. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: the process and practice of mindful change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012.

8. Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA, eds. A research agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2002.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

10. Dalrymple KL, Zimmerman M. Does comorbid social anxiety disorder impact the clinical presentation of principal major depressive disorder? J Affect Disord. 2007;100:241-247.

11. Dalrymple KL. Issues and controversies surrounding the diagnosis and treatment of social anxiety disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(8):993-1008.

12. Furmark T, Tillfors M, Everz PO, et al. Social phobia in the general population: prevalence and sociodemographic profile. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:416-424.

13. Narrow WE, Rae DS, Robins LN, et al. Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 surveys’ estimates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:115-123.

14. Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC. Shyness: relationship to social phobia and other psychiatric disorders. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:209-221.

15. Hofmann SG, Moscovitch DA, Hyo-Jin K. Autonomic correlates of social anxiety and embarrassment in shy and non-shy individuals. Int J Psychophysiology. 2006;61:134-142.

16. Kagan J. Temperamental contributions to affective and behavioral profiles in childhood. In: Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, eds. From social anxiety to social phobia: multiple perspectives. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001:216-234.

17. Cox BJ, MacPherson PS, Enns MW. Psychiatric correlates of childhood shyness in a nationally representative sample. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1019-1027.

18. Burstein M, Ameli-Grillon L, Merikangas KR. Shyness versus social phobia in US youth. Pediatrics. 2011;128:917-925.

19. Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Micco J, Henin A, et al. Behavioral inhibition. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:357-367.

20. Karevold E, Ystrom E, Coplan RJ, et al. A prospective longitudinal study of shyness from infancy to adolescence: stability, age-related changes, and prediction of socio-emotional functioning. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012; 40:1167-1177.

21. Chavira DA, Stein MB, Malcarne VL. Scrutinizing the relationship between shyness and social phobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2002;16:585-598.

22. Schneier FR, Blanco C, Antia SX, et al. The social anxiety spectrum. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002;25:757-774.

23. Stein MB, Chavira DA, Jang KL. Bringing up bashful baby: developmental pathways to social phobia. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2001;24:797-818.

24. Cooper PJ, Eke M. Childhood shyness and maternal social phobia: a community study. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:439-443.

25. Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC, et al. Differentiating social phobia from shyness. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:469-476.

26. Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141-173.

27. Dalrymple, KL, Martinez J, Tepe E, et al. A clinically useful social anxiety disorder outcome scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(7):758-765.

28. Connor KM, Kobak KA, Churchill LE, et al. Mini-SPIN: a brief screening assessment for generalized social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14(2):137-140.

29. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997.

30. Conrad P. Medicalization and social control. Ann Rev Sociology. 1992;18:209-232.

31. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I. Clinician recognition of anxiety disorders in depressed outpatients. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:325-333.

32. Gelernter CS, Uhde TW, Cimbolic P, et al. Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:938-945.

33. Otto MW, Smits JA, Reese HE. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 5):34-41.

34. Blanco C, Bragdon LB, Schneier FR, et al. The evidence-based pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:235-249.

Since the appearance of social anxiety disorder (SAD) in the DSM-III in 1980, research on its prevalence, characteristics, and treatment have grown (Box 11,2). In addition to the name, the definition of SAD has changed over the years; as a result, its prevalence has increased in recent cohort studies. This has led to debate over whether the experience of shyness is being over-pathologized, or whether SAD has been underdiagnosed in earlier decades. Those who argue that shyness is being over-pathologized note that it is a normal human experience that has evolutionary functions (eg, preventing engagement in harmful social relationships3). Others argue that a high degree of shyness is not beneficial in terms of evolution because it causes the individual to be shunned, so to speak, by society.4

Why worry about ‘over-pathologizing’?

The medicalization of shyness might be a reflection of Western societal values of assertiveness and gregariousness; other societies that value modesty and reticence do not over-pathologize shyness.5 It is important not to assume that someone who is shy necessarily has a “pathologic” level of social anxiety, especially because some people who are shy view that condition as a positive quality, much like sensitivity and conscientiousness.5

The broader issue of what constitutes a mental disorder arises in this debate. A “disorder” is a socially constructed label that describes a set of symptoms occurring together and its associated behaviors, not a real entity with etiological homogeneity.6 Labeling emotional problems “disordered” assumes that happiness is the natural homeostatic state, and distressing emotional states are abnormal and need to be changed.7 A diagnostic label can help improve communication and understand maladaptive behaviors; if that label is reified, however, it can lead to assumptions that the etiology, course, and treatment response are known. Proponents of the diagnostic psychiatric nomenclature have acknowledged the dangers of over-pathologizing normal experiences of living (such as fear) by way of diagnostic labeling.8

Determining when shyness becomes a clinically significant problem—what we call SAD here—demands a delicate distinction that has important implications for treatment. On one hand, if shyness is over-pathologized, persons who neither desire nor need treatment might be subjected to unnecessary and costly intervention. On the other hand, if SAD is underdiagnosed, some persons will not receive treatment that might be beneficial to them.

In this article, we review the similarities and differences between shyness and SAD, and provide recommendations for determining when shyness becomes a more clinically significant problem. We also highlight the importance of this distinction as it pertains to management, and provide suggestions for treatment approaches.

SAD: Definition, prevalence

SAD is defined as a significant fear of embarrassment or humiliation in social or performance-based situations, to a point at which the affected person often avoids these situations or endures them only with a high level of distress9 (Table 1, and Box 2). SAD can be distinguished from other anxiety disorders based on the source and content of the fear (ie, the source being social interaction or performance situations, and the content being a fear that one will show a behavior that will cause embarrassment). SAD also should be distinguished from autism spectrum disorders, in which persons have limited social communication capabilities and inadequate age-appropriate social relationships.

SAD is most highly comorbid with mood and anxiety disorders, with rates of at least 30% in clinical samples.10 The disorder also is highly comorbid with avoidant personality disorder—to a point at which it is argued that they are one and the same disorder.11

As with other psychiatric disorders, anxiety must cause significant impairment or distress. What constitutes significant impairment or distress is subjective, and the arbitrary nature of this criterion can influence estimates of the prevalence of SAD. For example, prevalence ranges as widely as 1.9% to 20.4% when different cut-offs are used for distress ratings and the number of impaired domains.12

The prevalence of SAD varies from 1 epidemiological study to another (ie, the Epidemiological Catchment Area [ECA] Study and the National Comorbidity Survey [NCS])—in part, a consequence of the differing definitions of significant impairment or distress. The ECA study assessed the clinical significance of each symptom in anxiety disorders; the NCS assessed overall clinical significance of the disorder. When the clinical significance criterion was applied at the symptom level to the NCS dataset (as was done in the ECA study), 1-year prevalence decreased by 50% (from 7.4% to 3.7%).13 The manner in which significant impairment or distress is defined (ie, conservatively or liberally) impacts whether social anxiety symptoms are classified as disordered or non-disordered.

Shyness: Definition, prevalence

Shyness often refers to 1) anxiety, inhibition, reticence, or a combination of these findings, in social and interpersonal situations, and 2) a fear of negative evaluation by others.14 It is a normal facet of personality that combines the experience of social anxiety and inhibited behavior,15 and also has been described as a stable temperament.16 Shyness is common; in the NCS study,17 26% of women and 19% of men characterized themselves as “very shy”; in the NCS Adolescent study,18 nearly 50% of adolescents self-identified as shy.

Persons who are shy tend to self-report greater social anxiety and embarrassment in social situations than non-shy persons do; they also might experience greater autonomic reactivity—especially blushing—in social or performance situations.15 Furthermore, shy persons are more likely to have axis I comorbidity and traits of introversion and neuroticism, compared with non-shy persons.14

Research suggests that temperament and behavioral inhibition are risk factors for mood and anxiety disorders, and appear to have a particularly strong relationship with SAD.19 A recent prospective study showed that shyness tends to increase steeply in toddlerhood, then stabilizes in childhood. Shyness in childhood—but not toddlerhood—is predictive of anxiety, depression, and poorer social skills in adolescence.20

A qualitative, or just quantitative, difference?

It is clear that SAD and shyness share several features—including anxiety and embarrassment—in social interactions. This raises a question: Are SAD and shyness distinct qualitatively, or do they represent points along a continuum, with SAD being an extreme form of shyness?

Continuum hypothesis. Support for the continuum hypothesis includes evidence that SAD and shyness share several features, including autonomic arousal, deficits in social skills (eg, aversion of gaze, difficulty initiating and maintaining conversation), avoidance of social situations, and fear of negative evaluation.21,22 In addition, both shyness and SAD are highly heritable,23 and mothers of shy children have a significantly higher rate of SAD than non-shy children do.24 No familial or genetic studies have compared heritability and familial aggregation in shyness and SAD.

According to the continuum hypothesis, if SAD is an extreme form of shyness, all (or nearly all) persons who have a diagnosis of SAD also would be characterized as shy. However, only approximately one-half of such persons report having been shy in childhood.17 Less than one-quarter of shy persons meet criteria for SAD.14,18 Because many persons who are shy do not meet criteria for SAD, and many who have SAD were not considered shy earlier in life, it has been suggested that this supports a qualitative distinction.

Qualitative distinctiveness. Despite having similarities, several features distinguish the experience of SAD from that of shyness. Compared with shyness, a SAD diagnosis is associated with:

- greater comorbidity

- greater severity of avoidance and impairment

- poorer quality of life.18,21,25

Studies that compared SAD, shyness without SAD, and non-shyness have shown that the shyness without SAD group more closely resembles the non-shy group than the SAD group—particularly with regard to impairment, presence of substance use, and other behavioral problems.18,25

Given the evidence, experts have concluded that shyness and a SAD diagnosis are overlapping yet different constructs that encapsulate qualitative and quantitative differences.25 There is a spectrum of shyness that ranges from a normative level to a higher level that overlaps the experience of SAD, but the 2 states represent different constructs.25

Guidance for making an assessment. Because of similarities in anxiety, embarrassment, and other symptoms in social situations, the best way to determine whether shyness crosses the line into a clinically significant problem is to assess the severity of the anxiety and associated degree of impairment and distress. More severe anxiety paired with distress about having anxiety and significant impairment in multiple areas of functioning might indicate more problematic social anxiety—a diagnosis of SAD—not just “normal” shyness.

It is important to take into account the environmental and cultural context of a patient’s distress and impairment because these features might fall within a normal range, given immediate circumstances (such as speaking in front of a large audience when one is not normally called on to do so, to a degree that does not interfere with general social functioning6).

What is considered a normative range depends on the developmental stage:

- Among children, a greater level of shyness might be considered more normative when it manifests during developmental stages in which separation anxiety appears.

- Among adolescents, a greater level of shyness might be considered normative especially during early adolescence (when social relationships become more important), and during times of transition (ie, entering high school).

- In adulthood, a greater level of normative shyness or social anxiety might be present during a major life change (eg, beginning to date again after the loss of a lengthy marriage or romantic relationship).

Assessment tools

Assessment tools can help you differentiate normal shyness from SAD. Several empirically-validated rating scales exist, including clinician-rated and self-report scales.

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale26 rates the severity of fear and avoidance in a variety of social interaction and performance-based situations. However, it was developed primarily as a clinician-rated scale and might be more burdensome to complete in practice. In addition, it does not provide cut-offs to indicate when more clinically significant anxiety might be likely.

Clinically Useful Social Anxiety Disorder Outcome Scale (CUSADOS)27 and Mini-Social Phobia Inventory (Mini-SPIN)28 are brief self-report scales that provide cut-offs to suggest further assessment is warranted. A cut-off score of 16 on the CUSADOS suggests the presence of SAD with 73% diagnostic efficiency.

One disadvantage to relying on a rating scale alone is the narrow focus on symptoms. Given that shyness and SAD share similar symptoms, it is necessary to assess the degree of impairment related to these symptoms to determine whether the problem is clinically significant. The overly narrow focus on symptoms utilized by the biomedical approach has been criticized for contributing to the medicalization of normal shyness.5

Diagnostic interviews, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders29 include sections on SAD that assess avoidance and impairment/distress associated with anxiety. Because these interviews may increase the time burden during an office visit, there are several general questions outside of a structured interview that you can ask, such as: “Has this anxiety interfered with your ability to initiate or maintain friendships? If so, how?” (Table 2). Persons with clinically significant social anxiety, rather than shyness, tend to report greater effects on their relationships and on work or school performance, as well as greater distress about having that anxiety.

Treatment approaches based on distinctions

Exercise care in making the distinction between normal shyness and dysfunctional and impairing levels of anxiety characteristic of SAD, because persons who display normal shyness but who are overdiagnosed might feel stigmatized by a diagnostic label.5 Also, overpathologizing shyness takes what is a social problem out of context, and could promote treatment strategies that might not be helpful or effective.30

Unnecessary diagnosis might lead to unnecessary treatment, such as prescribing an antidepressant or benzodiazepine. Avoiding such a situation is important, because of the side effects associated with medication and the potential for dependence and withdrawal effects with benzodiazepines.

Persons who exhibit normal shyness do not require medical treatment and, often, do not want it. However, some people may be interested in improving their ability to function in social interactions. Self-help approaches or brief psychotherapy (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) should be the first step—and might be all that is necessary.

The opposite side of the problem. Under-recognition of clinically significant social anxiety can lead to under-treatment, which is common even in patients with a SAD diagnosis.31 Treatment options include CBT, medication, and CBT combined with medication (Table 3):

- several studies have demonstrated the short- and long-term efficacy of CBT alone for SAD

- medication alone has been efficacious in the short-term, but less efficacious than CBT in the long-term

- combined treatment also has been shown to be more efficacious than CBT or medication alone in the short-term

- there is evidence to suggest that CBT alone is more efficacious in the long-term compared with combined treatment.a

CBT is recommended as an appropriate first-line option, especially for mild and moderate SAD; it is the preferred initial treatment option of the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). For more severe presentations (such as the presence of comorbidity) or when a patient did not respond to an adequate course of CBT, combined treatment might be an option—the goal being to taper the medication and continue CBT as a longer-term treatment. Research has shown that continuing CBT while discontinuing medication helps prevent relapse.32,33

Appropriate pharmacotherapy options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.34 Increasingly, benzodiazepines are considered less desirable; they are not recommended for routine use in SAD in the NICE guidelines. Those guidelines call for continuing pharmacotherapy for 6 months when a patient responds to treatment within 3 months, then discontinuing medication with the aid of CBT.

Bottom Line

The severity of anxiety and associated impairment and distress are the main variables that differentiate normal shyness and clinically significant social anxiety. Taking care not to over-pathologize normal shyness and common social anxiety concerns or underdiagnose severe, impairing social anxiety disorder has important implications for treatment—and for whether a patient needs treatment at all.

Related Resources

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment, and treatment of social anxiety disorder. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/cg159.

• Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, eds. Social anxiety: clinical, developmental, and social perspectives, 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 2010.

• The Shyness Institute. www.shyness.com.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax Clonazepam • Klonopin Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox Paroxetine • Paxil Phenelzine • Nardil

Sertraline • Zoloft Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

Kristy L. Dalrymple, PhD, discusses, treating social anxiety disorder. Dr. Dalrymple is Staff Psychologist, Department of Psychiatry, Rhode Island Hospital, and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

Since the appearance of social anxiety disorder (SAD) in the DSM-III in 1980, research on its prevalence, characteristics, and treatment have grown (Box 11,2). In addition to the name, the definition of SAD has changed over the years; as a result, its prevalence has increased in recent cohort studies. This has led to debate over whether the experience of shyness is being over-pathologized, or whether SAD has been underdiagnosed in earlier decades. Those who argue that shyness is being over-pathologized note that it is a normal human experience that has evolutionary functions (eg, preventing engagement in harmful social relationships3). Others argue that a high degree of shyness is not beneficial in terms of evolution because it causes the individual to be shunned, so to speak, by society.4

Why worry about ‘over-pathologizing’?

The medicalization of shyness might be a reflection of Western societal values of assertiveness and gregariousness; other societies that value modesty and reticence do not over-pathologize shyness.5 It is important not to assume that someone who is shy necessarily has a “pathologic” level of social anxiety, especially because some people who are shy view that condition as a positive quality, much like sensitivity and conscientiousness.5

The broader issue of what constitutes a mental disorder arises in this debate. A “disorder” is a socially constructed label that describes a set of symptoms occurring together and its associated behaviors, not a real entity with etiological homogeneity.6 Labeling emotional problems “disordered” assumes that happiness is the natural homeostatic state, and distressing emotional states are abnormal and need to be changed.7 A diagnostic label can help improve communication and understand maladaptive behaviors; if that label is reified, however, it can lead to assumptions that the etiology, course, and treatment response are known. Proponents of the diagnostic psychiatric nomenclature have acknowledged the dangers of over-pathologizing normal experiences of living (such as fear) by way of diagnostic labeling.8

Determining when shyness becomes a clinically significant problem—what we call SAD here—demands a delicate distinction that has important implications for treatment. On one hand, if shyness is over-pathologized, persons who neither desire nor need treatment might be subjected to unnecessary and costly intervention. On the other hand, if SAD is underdiagnosed, some persons will not receive treatment that might be beneficial to them.

In this article, we review the similarities and differences between shyness and SAD, and provide recommendations for determining when shyness becomes a more clinically significant problem. We also highlight the importance of this distinction as it pertains to management, and provide suggestions for treatment approaches.

SAD: Definition, prevalence

SAD is defined as a significant fear of embarrassment or humiliation in social or performance-based situations, to a point at which the affected person often avoids these situations or endures them only with a high level of distress9 (Table 1, and Box 2). SAD can be distinguished from other anxiety disorders based on the source and content of the fear (ie, the source being social interaction or performance situations, and the content being a fear that one will show a behavior that will cause embarrassment). SAD also should be distinguished from autism spectrum disorders, in which persons have limited social communication capabilities and inadequate age-appropriate social relationships.

SAD is most highly comorbid with mood and anxiety disorders, with rates of at least 30% in clinical samples.10 The disorder also is highly comorbid with avoidant personality disorder—to a point at which it is argued that they are one and the same disorder.11

As with other psychiatric disorders, anxiety must cause significant impairment or distress. What constitutes significant impairment or distress is subjective, and the arbitrary nature of this criterion can influence estimates of the prevalence of SAD. For example, prevalence ranges as widely as 1.9% to 20.4% when different cut-offs are used for distress ratings and the number of impaired domains.12

The prevalence of SAD varies from 1 epidemiological study to another (ie, the Epidemiological Catchment Area [ECA] Study and the National Comorbidity Survey [NCS])—in part, a consequence of the differing definitions of significant impairment or distress. The ECA study assessed the clinical significance of each symptom in anxiety disorders; the NCS assessed overall clinical significance of the disorder. When the clinical significance criterion was applied at the symptom level to the NCS dataset (as was done in the ECA study), 1-year prevalence decreased by 50% (from 7.4% to 3.7%).13 The manner in which significant impairment or distress is defined (ie, conservatively or liberally) impacts whether social anxiety symptoms are classified as disordered or non-disordered.

Shyness: Definition, prevalence

Shyness often refers to 1) anxiety, inhibition, reticence, or a combination of these findings, in social and interpersonal situations, and 2) a fear of negative evaluation by others.14 It is a normal facet of personality that combines the experience of social anxiety and inhibited behavior,15 and also has been described as a stable temperament.16 Shyness is common; in the NCS study,17 26% of women and 19% of men characterized themselves as “very shy”; in the NCS Adolescent study,18 nearly 50% of adolescents self-identified as shy.

Persons who are shy tend to self-report greater social anxiety and embarrassment in social situations than non-shy persons do; they also might experience greater autonomic reactivity—especially blushing—in social or performance situations.15 Furthermore, shy persons are more likely to have axis I comorbidity and traits of introversion and neuroticism, compared with non-shy persons.14

Research suggests that temperament and behavioral inhibition are risk factors for mood and anxiety disorders, and appear to have a particularly strong relationship with SAD.19 A recent prospective study showed that shyness tends to increase steeply in toddlerhood, then stabilizes in childhood. Shyness in childhood—but not toddlerhood—is predictive of anxiety, depression, and poorer social skills in adolescence.20

A qualitative, or just quantitative, difference?

It is clear that SAD and shyness share several features—including anxiety and embarrassment—in social interactions. This raises a question: Are SAD and shyness distinct qualitatively, or do they represent points along a continuum, with SAD being an extreme form of shyness?

Continuum hypothesis. Support for the continuum hypothesis includes evidence that SAD and shyness share several features, including autonomic arousal, deficits in social skills (eg, aversion of gaze, difficulty initiating and maintaining conversation), avoidance of social situations, and fear of negative evaluation.21,22 In addition, both shyness and SAD are highly heritable,23 and mothers of shy children have a significantly higher rate of SAD than non-shy children do.24 No familial or genetic studies have compared heritability and familial aggregation in shyness and SAD.

According to the continuum hypothesis, if SAD is an extreme form of shyness, all (or nearly all) persons who have a diagnosis of SAD also would be characterized as shy. However, only approximately one-half of such persons report having been shy in childhood.17 Less than one-quarter of shy persons meet criteria for SAD.14,18 Because many persons who are shy do not meet criteria for SAD, and many who have SAD were not considered shy earlier in life, it has been suggested that this supports a qualitative distinction.

Qualitative distinctiveness. Despite having similarities, several features distinguish the experience of SAD from that of shyness. Compared with shyness, a SAD diagnosis is associated with:

- greater comorbidity

- greater severity of avoidance and impairment

- poorer quality of life.18,21,25

Studies that compared SAD, shyness without SAD, and non-shyness have shown that the shyness without SAD group more closely resembles the non-shy group than the SAD group—particularly with regard to impairment, presence of substance use, and other behavioral problems.18,25

Given the evidence, experts have concluded that shyness and a SAD diagnosis are overlapping yet different constructs that encapsulate qualitative and quantitative differences.25 There is a spectrum of shyness that ranges from a normative level to a higher level that overlaps the experience of SAD, but the 2 states represent different constructs.25

Guidance for making an assessment. Because of similarities in anxiety, embarrassment, and other symptoms in social situations, the best way to determine whether shyness crosses the line into a clinically significant problem is to assess the severity of the anxiety and associated degree of impairment and distress. More severe anxiety paired with distress about having anxiety and significant impairment in multiple areas of functioning might indicate more problematic social anxiety—a diagnosis of SAD—not just “normal” shyness.

It is important to take into account the environmental and cultural context of a patient’s distress and impairment because these features might fall within a normal range, given immediate circumstances (such as speaking in front of a large audience when one is not normally called on to do so, to a degree that does not interfere with general social functioning6).

What is considered a normative range depends on the developmental stage:

- Among children, a greater level of shyness might be considered more normative when it manifests during developmental stages in which separation anxiety appears.

- Among adolescents, a greater level of shyness might be considered normative especially during early adolescence (when social relationships become more important), and during times of transition (ie, entering high school).

- In adulthood, a greater level of normative shyness or social anxiety might be present during a major life change (eg, beginning to date again after the loss of a lengthy marriage or romantic relationship).

Assessment tools

Assessment tools can help you differentiate normal shyness from SAD. Several empirically-validated rating scales exist, including clinician-rated and self-report scales.

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale26 rates the severity of fear and avoidance in a variety of social interaction and performance-based situations. However, it was developed primarily as a clinician-rated scale and might be more burdensome to complete in practice. In addition, it does not provide cut-offs to indicate when more clinically significant anxiety might be likely.

Clinically Useful Social Anxiety Disorder Outcome Scale (CUSADOS)27 and Mini-Social Phobia Inventory (Mini-SPIN)28 are brief self-report scales that provide cut-offs to suggest further assessment is warranted. A cut-off score of 16 on the CUSADOS suggests the presence of SAD with 73% diagnostic efficiency.

One disadvantage to relying on a rating scale alone is the narrow focus on symptoms. Given that shyness and SAD share similar symptoms, it is necessary to assess the degree of impairment related to these symptoms to determine whether the problem is clinically significant. The overly narrow focus on symptoms utilized by the biomedical approach has been criticized for contributing to the medicalization of normal shyness.5

Diagnostic interviews, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders29 include sections on SAD that assess avoidance and impairment/distress associated with anxiety. Because these interviews may increase the time burden during an office visit, there are several general questions outside of a structured interview that you can ask, such as: “Has this anxiety interfered with your ability to initiate or maintain friendships? If so, how?” (Table 2). Persons with clinically significant social anxiety, rather than shyness, tend to report greater effects on their relationships and on work or school performance, as well as greater distress about having that anxiety.

Treatment approaches based on distinctions

Exercise care in making the distinction between normal shyness and dysfunctional and impairing levels of anxiety characteristic of SAD, because persons who display normal shyness but who are overdiagnosed might feel stigmatized by a diagnostic label.5 Also, overpathologizing shyness takes what is a social problem out of context, and could promote treatment strategies that might not be helpful or effective.30

Unnecessary diagnosis might lead to unnecessary treatment, such as prescribing an antidepressant or benzodiazepine. Avoiding such a situation is important, because of the side effects associated with medication and the potential for dependence and withdrawal effects with benzodiazepines.

Persons who exhibit normal shyness do not require medical treatment and, often, do not want it. However, some people may be interested in improving their ability to function in social interactions. Self-help approaches or brief psychotherapy (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) should be the first step—and might be all that is necessary.

The opposite side of the problem. Under-recognition of clinically significant social anxiety can lead to under-treatment, which is common even in patients with a SAD diagnosis.31 Treatment options include CBT, medication, and CBT combined with medication (Table 3):

- several studies have demonstrated the short- and long-term efficacy of CBT alone for SAD

- medication alone has been efficacious in the short-term, but less efficacious than CBT in the long-term

- combined treatment also has been shown to be more efficacious than CBT or medication alone in the short-term

- there is evidence to suggest that CBT alone is more efficacious in the long-term compared with combined treatment.a

CBT is recommended as an appropriate first-line option, especially for mild and moderate SAD; it is the preferred initial treatment option of the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). For more severe presentations (such as the presence of comorbidity) or when a patient did not respond to an adequate course of CBT, combined treatment might be an option—the goal being to taper the medication and continue CBT as a longer-term treatment. Research has shown that continuing CBT while discontinuing medication helps prevent relapse.32,33

Appropriate pharmacotherapy options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.34 Increasingly, benzodiazepines are considered less desirable; they are not recommended for routine use in SAD in the NICE guidelines. Those guidelines call for continuing pharmacotherapy for 6 months when a patient responds to treatment within 3 months, then discontinuing medication with the aid of CBT.

Bottom Line

The severity of anxiety and associated impairment and distress are the main variables that differentiate normal shyness and clinically significant social anxiety. Taking care not to over-pathologize normal shyness and common social anxiety concerns or underdiagnose severe, impairing social anxiety disorder has important implications for treatment—and for whether a patient needs treatment at all.

Related Resources

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment, and treatment of social anxiety disorder. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/cg159.

• Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, eds. Social anxiety: clinical, developmental, and social perspectives, 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 2010.

• The Shyness Institute. www.shyness.com.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax Clonazepam • Klonopin Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox Paroxetine • Paxil Phenelzine • Nardil

Sertraline • Zoloft Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

Kristy L. Dalrymple, PhD, discusses, treating social anxiety disorder. Dr. Dalrymple is Staff Psychologist, Department of Psychiatry, Rhode Island Hospital, and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

1. Bruce LC, Coles ME, Heimberg RG. Social phobia and social anxiety disorder: effect of disorder name on recommendation for treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):538.

2. Bögels SM, Alden L, Beidel DC, et al. Social anxiety disorder: questions and answers for the DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:168-189.

3. Wakefield JC, Horwitz AV, Schmitz MF. Are we overpathologizing the socially anxious? Social phobia from a harmful dysfunction perspective. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(6):317-319.

4. Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Justifying the diagnostic status of social phobia: a reply to Wakefield, Horwitz, and Schmitz. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(6):320-323.

5. Scott S. The medicalisation of shyness: from social misfits to social fitness. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2006;28(2):133-153.

6. Wakefield JC. The DSM-5 debate over the bereavement exclusion: psychiatric diagnosis and the future of empirically supported treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013; 33(7):825-845.

7. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: the process and practice of mindful change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012.

8. Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA, eds. A research agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2002.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

10. Dalrymple KL, Zimmerman M. Does comorbid social anxiety disorder impact the clinical presentation of principal major depressive disorder? J Affect Disord. 2007;100:241-247.

11. Dalrymple KL. Issues and controversies surrounding the diagnosis and treatment of social anxiety disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(8):993-1008.

12. Furmark T, Tillfors M, Everz PO, et al. Social phobia in the general population: prevalence and sociodemographic profile. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:416-424.

13. Narrow WE, Rae DS, Robins LN, et al. Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 surveys’ estimates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:115-123.

14. Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC. Shyness: relationship to social phobia and other psychiatric disorders. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:209-221.

15. Hofmann SG, Moscovitch DA, Hyo-Jin K. Autonomic correlates of social anxiety and embarrassment in shy and non-shy individuals. Int J Psychophysiology. 2006;61:134-142.

16. Kagan J. Temperamental contributions to affective and behavioral profiles in childhood. In: Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, eds. From social anxiety to social phobia: multiple perspectives. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001:216-234.

17. Cox BJ, MacPherson PS, Enns MW. Psychiatric correlates of childhood shyness in a nationally representative sample. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1019-1027.

18. Burstein M, Ameli-Grillon L, Merikangas KR. Shyness versus social phobia in US youth. Pediatrics. 2011;128:917-925.

19. Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Micco J, Henin A, et al. Behavioral inhibition. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:357-367.

20. Karevold E, Ystrom E, Coplan RJ, et al. A prospective longitudinal study of shyness from infancy to adolescence: stability, age-related changes, and prediction of socio-emotional functioning. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012; 40:1167-1177.

21. Chavira DA, Stein MB, Malcarne VL. Scrutinizing the relationship between shyness and social phobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2002;16:585-598.

22. Schneier FR, Blanco C, Antia SX, et al. The social anxiety spectrum. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002;25:757-774.

23. Stein MB, Chavira DA, Jang KL. Bringing up bashful baby: developmental pathways to social phobia. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2001;24:797-818.

24. Cooper PJ, Eke M. Childhood shyness and maternal social phobia: a community study. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:439-443.

25. Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC, et al. Differentiating social phobia from shyness. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:469-476.

26. Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141-173.

27. Dalrymple, KL, Martinez J, Tepe E, et al. A clinically useful social anxiety disorder outcome scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(7):758-765.

28. Connor KM, Kobak KA, Churchill LE, et al. Mini-SPIN: a brief screening assessment for generalized social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14(2):137-140.

29. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997.

30. Conrad P. Medicalization and social control. Ann Rev Sociology. 1992;18:209-232.

31. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I. Clinician recognition of anxiety disorders in depressed outpatients. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:325-333.

32. Gelernter CS, Uhde TW, Cimbolic P, et al. Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:938-945.

33. Otto MW, Smits JA, Reese HE. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 5):34-41.

34. Blanco C, Bragdon LB, Schneier FR, et al. The evidence-based pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:235-249.

1. Bruce LC, Coles ME, Heimberg RG. Social phobia and social anxiety disorder: effect of disorder name on recommendation for treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):538.

2. Bögels SM, Alden L, Beidel DC, et al. Social anxiety disorder: questions and answers for the DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:168-189.

3. Wakefield JC, Horwitz AV, Schmitz MF. Are we overpathologizing the socially anxious? Social phobia from a harmful dysfunction perspective. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(6):317-319.

4. Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Justifying the diagnostic status of social phobia: a reply to Wakefield, Horwitz, and Schmitz. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(6):320-323.

5. Scott S. The medicalisation of shyness: from social misfits to social fitness. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2006;28(2):133-153.

6. Wakefield JC. The DSM-5 debate over the bereavement exclusion: psychiatric diagnosis and the future of empirically supported treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013; 33(7):825-845.

7. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: the process and practice of mindful change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012.

8. Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA, eds. A research agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2002.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

10. Dalrymple KL, Zimmerman M. Does comorbid social anxiety disorder impact the clinical presentation of principal major depressive disorder? J Affect Disord. 2007;100:241-247.

11. Dalrymple KL. Issues and controversies surrounding the diagnosis and treatment of social anxiety disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(8):993-1008.

12. Furmark T, Tillfors M, Everz PO, et al. Social phobia in the general population: prevalence and sociodemographic profile. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:416-424.

13. Narrow WE, Rae DS, Robins LN, et al. Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 surveys’ estimates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:115-123.

14. Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC. Shyness: relationship to social phobia and other psychiatric disorders. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:209-221.

15. Hofmann SG, Moscovitch DA, Hyo-Jin K. Autonomic correlates of social anxiety and embarrassment in shy and non-shy individuals. Int J Psychophysiology. 2006;61:134-142.

16. Kagan J. Temperamental contributions to affective and behavioral profiles in childhood. In: Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, eds. From social anxiety to social phobia: multiple perspectives. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001:216-234.

17. Cox BJ, MacPherson PS, Enns MW. Psychiatric correlates of childhood shyness in a nationally representative sample. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1019-1027.

18. Burstein M, Ameli-Grillon L, Merikangas KR. Shyness versus social phobia in US youth. Pediatrics. 2011;128:917-925.

19. Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Micco J, Henin A, et al. Behavioral inhibition. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:357-367.

20. Karevold E, Ystrom E, Coplan RJ, et al. A prospective longitudinal study of shyness from infancy to adolescence: stability, age-related changes, and prediction of socio-emotional functioning. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012; 40:1167-1177.

21. Chavira DA, Stein MB, Malcarne VL. Scrutinizing the relationship between shyness and social phobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2002;16:585-598.

22. Schneier FR, Blanco C, Antia SX, et al. The social anxiety spectrum. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002;25:757-774.

23. Stein MB, Chavira DA, Jang KL. Bringing up bashful baby: developmental pathways to social phobia. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2001;24:797-818.

24. Cooper PJ, Eke M. Childhood shyness and maternal social phobia: a community study. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:439-443.

25. Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC, et al. Differentiating social phobia from shyness. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:469-476.

26. Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141-173.

27. Dalrymple, KL, Martinez J, Tepe E, et al. A clinically useful social anxiety disorder outcome scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(7):758-765.

28. Connor KM, Kobak KA, Churchill LE, et al. Mini-SPIN: a brief screening assessment for generalized social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14(2):137-140.

29. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997.

30. Conrad P. Medicalization and social control. Ann Rev Sociology. 1992;18:209-232.

31. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I. Clinician recognition of anxiety disorders in depressed outpatients. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:325-333.

32. Gelernter CS, Uhde TW, Cimbolic P, et al. Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:938-945.

33. Otto MW, Smits JA, Reese HE. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 5):34-41.

34. Blanco C, Bragdon LB, Schneier FR, et al. The evidence-based pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:235-249.

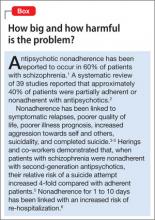

Overcoming medication nonadherence in schizophrenia: Strategies that can reduce harm

Medication nonadherence is a common problem when treating patients with schizophrenia that can worsen prognosis and lead to sub-optimal treatment outcomes. In this article, we discuss common reasons for nonadherence and describe evidence-based treatments intended to increase adherence and improve outcomes (Box).1-6

Common reasons for nonadherence

The primary predictor of future nonadherence is a history of nonadherence. It is important to understand patients’ reasons for nonadherence so that practical and evidence-based solutions can be implemented into the treatment plans of individual patients.

The 2009 Expert Consensus Guidelines on Adherence Problems in Patients with Serious and Persistent Mental Illness divided variables related to nonadherence into 3 categories:

- those that lie within the patient (intrinsic)

- those that are related to the patient’s relationship with healthcare providers, family, or caregivers (extrinsic)

- those that are related to the healthcare delivery system (extrinsic).7

Among intrinsic variables, studies have shown a correlation between nonadherence and education level, lower socioeconomic status, homelessness, and male sex.7 (The Expert Consensus Guidelines considered homelessness to be an intrinsic factor because it was used as a demographic variable in the studies.)

Cognitive and negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia are an intrinsic risk factor for nonadherence because patients might not remember when or how to take medication.7 In a study by Freudenreich and co-workers8 of 81 outpatients who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, the presence of negative symptoms predicted a negative attitude toward psychotropic medications. Poor insight might be the result of cognitive dysfunction associated with schizophrenia, and often is due to a lack of awareness of the importance of taking medications.

Limited insight into the need for treatment can be problematic early in the course of the illness when it may be directly related to positive symptoms. Perkins and colleagues9 demonstrated that patients recovering from a first psychotic episode who had limited insight into their illness and lacked desire to seek treatment were less adherent with medication. In another study, 5% of psychiatrists surveyed thought that many of their patients with schizophrenia were nonadherent because those patients did not believe that medications were effective or useful.10

Comorbid substance abuse disorders can contribute to medication nonadherence. In an analysis of 6,731 patients with schizophrenia, Novick and co-workers reported that alcohol dependence and substance abuse in the previous month predicted medication nonadherence.11 Hunt and colleagues demonstrated that, among 99 nonadherent patients with schizophrenia, time to first readmission was shorter for patients with comorbid substance abuse disorders compared with patients who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia only. Over the 4-year study period, the 28 patients who had a dual diagnosis (schizophrenia and substance abuse) accounted for 57% of all hospital readmissions.12

Several variables that affect medication adherence are related to the patient’s relationship with healthcare providers, family, caregivers, and the service delivery system.7 These include:

- the perceived stigma of being given a diagnosis of a serious mental illness

- adverse effects related to medications

- poor social and family support

- difficulty gaining access to mental health services.7,10

Societal stigma associated with seeking treatment from a mental health professional may contribute to nonadherence in some patients. In 1 study,13 36% of people surveyed would not want to work closely with a person who has a serious mental illness.

Adverse effects contribute significantly to nonadherence

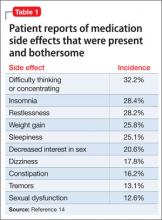

Limited treatment options (which may be expensive) can make it difficult to manage the adverse effects of antipsychotics. In a cross-sectional survey of 876 patients, investigators reported that: 1) <50% of patients were adherent with medication, and 2) 80% experienced ≥1 side effect that was reported to be “somewhat bothersome” in self-ratings (Table 1).14 Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and agitation were most strongly associated with nonadherence; weight gain, akathisia, and sexual dysfunction also were associated with nonadherence.14 This study did not distinguish adverse effects associated with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) from those associated with second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), even though 71.7% of patients studied were taking an SGA.

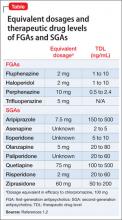

A meta-analysis by Leucht and co-workers15 compared 15 antipsychotics (the FGAs haloperidol and chlorpromazine and 13 SGAs) for efficacy and tolerability in schizophrenia. Haloperidol had the highest rate of discontinuation for any

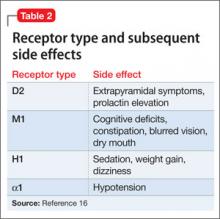

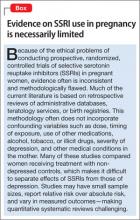

Antipsychotic binding affinities to dopamine 2 (D2), serotonin 2A (5-HT2A), histamine (H1), and other receptors have an impact on a medication’s side-effect profile. Because of individual patient characteristics, you might be faced with choosing a medication that has a lower risk of EPS but a higher risk of weight gain and metabolic complications—or the inverse. Understanding binding affinities, side-effect profiles, and how to minimize or utilize adverse effects (ie, giving a drug that is approved to treat schizophrenia and is associated with weight gain to a patient with schizophrenia who has lost weight) may lead to greater adherence (Table 216 and Table 317).

Adequate support is essential

The therapeutic alliance plays a key role in patients’ attitudes toward taking medication. Magura and colleagues18 found that one-third of psychiatric patients (13% of whom had a diagnosis of schizophrenia) reported that their psychiatrist did not spend enough time with them explaining side effects, and felt “rushed.”

Patients with schizophrenia often require access to social support systems provided by family members, friends, and community agencies that provide case management and attendant care services. Patients who are adherent to medication tend to have greater perceived family involvement in medication treatment, and tend to have been raised in a family that had more of a positive attitude toward medication.19

In our practice, we have observed that recent state and federal budget cuts have resulted in patients having greater difficulty gaining access to case management and attendant care services, which then leads to increased rates of medication nonadherence. Be aware that variables such as limited office hours, financial hardship, and cultural and language barriers can compromise a patient’s ability to seek and continue care.

In the following section, we lay out techniques for improving adherence in patients with schizophrenia.

Employ general and specific strategies to boost adherence

How can you raise medication adherence concerns with patients, keeping in mind that they often overestimate their adherence?

Ask. Some clinicians ask questions such as “Are you taking your medication?”, although a more effective approach might be to ask how the patient is taking his (her) medication. Asking questions such as “When do you take your medication?” and “In the past week, how many doses do you think you missed?” might be more effective ways to inquire about adherence.7

The Expert Consensus Guidelines recommend asking patients about medication adherence monthly for those who are stable, doing well, and believed to be adherent. For those who are new to a practice or who are not doing well, inquire about medication adherence at least weekly.7

In our practice, patients who are unstable but do not require inpatient hospitalization typically are seen more often in the clinic, or are referred to intensive outpatient or partial hospitalization programs. If an unstable patient is unable to come in for more frequent appointments, we arrange phone conferences between her and her provider. If a patient is not doing well and has a case manager, we often ask that case manager to visit the patient, in person, more often than he (she) would otherwise.

Take a nonjudgmental approach when raising these issues with patients. Questions such as “We all forget to take our medication sometimes; do you?” help to normalize nonadherence, and improve the therapeutic alliance, and might result in the patient being more honest with the clinician.7 Because patients may be apprehensive about discussing adverse events, clinicians must be proactive about improving the therapeutic alliance and making patients feel comfortable when discussing sensitive topics. Clinicians should try to convey the idea that, although adherence is a concern, so is quality of life. A clinicians’ willingness to take a flexible approach that is nonpunitive nor authoritarian can aid the therapeutic alliance and improve overall adherence.

Be sensitive to financial, cultural, and language variables that can affect access to care. The Expert Consensus Guidelines recommend asking patients if they can afford their medication. In our practice, we have seen patients with schizophrenia discharged from the hospital only to be readmitted 1 month later because they could not afford to fill their prescriptions.

It is important to have translation services available, in person or by phone, for patients who do not speak English. Furthermore, it is important to understand the limitations that your practice might place on access to care. Ask patients if they have ever had trouble making an appointment when they needed to be seen, or if they called the office with a question and did not receive an answer in a timely fashion; doing so allows you to assess the practice’s ability to meet patients’ needs and helps you build a therapeutic alliance.

Make objective assessments. It is important for practitioners to not base their assessment of medication adherence solely on subjective findings. Asking patients to bring in their medication bottles for pill counts and checking with the patients’ pharmacies for information about refill frequency can provide some objective data. Electronic monitoring systems use microprocessors inserted into bottle caps to record the occurrence and timing of each bottle opening. Studies show that these electronic monitoring systems are the gold standard for determining medication adherence and could be used in cases where it is unclear if the patient is taking his (her) medication.7,20 Such systems have successfully monitored medication adherence in clinical trials, but their use in clinical practice is complicated by ethical and legal considerations and cost issues.