User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Apixaban Reduces Risks for AF Patients with Renal Dysfunction

NEW YORK - In patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and a wide range of renal function, compared to warfarin, treatment with apixaban reduces the risk of cardiovascular events, according to multinational investigators.

As Dr. Ziad Hijazi told Reuters Health by email, "Renal dysfunction is a complex issue in patients with atrial fibrillation when balancing the risk of stroke versus the risk of bleeding."

"This study," he added, "shows that apixaban, compared with warfarin, was associated with a lower risk of stroke, death, and major bleeding, regardless of changes in renal function over time. These findings may aid clinicians in the treatment decision."

In a June 15 online paper in JAMA Cardiology, Dr. Hijazi, of Uppsala University Hospital, Sweden, and colleagues report that they came to this conclusion after examining data from a clinical trial (ARISTOTLE) on more than 16,800 AF patients randomized to apixaban or warfarin.

Over the course of a year, about a quarter (26%) maintained good renal function. Renal function declined in the others, and 13.6% showed a drop of more than 20%. The decline in renal function was more rapid in patients who were older or had comorbidities.

Overall, the risks of stroke or systemic embolism, major bleeding, and mortality were greater in patients with worsening renal function (hazard ratio, 1.53 for stroke or systemic embolism, 1.56 for major bleeding, and 2.31 for mortality).

However, such patients on apixaban, compared with warfarin, consistently demonstrated a lower relative risk of stroke or systemic embolism (HR 0.80), ischemic or unspecified stroke (HR 0.88), and major bleeding (HR 0.76).

In fact, as well as showing benefit in this group of patients, the researchers conclude, "The superior efficacy and safety of apixaban as compared with warfarin were similar in patients with normal, poor, and worsening renal function."

Commenting on the findings by email, cardiologist Dr. Anil Pandit of Scottsdale, Arizona, told Reuters Health, "The study by Hijazi et al answers very important clinical questions regarding safety and efficacy of apixaban in situations of declining renal function, a common phenomenon in a real world scenario."

An earlier meta-analysis, in which Dr. Pandit was involved, found decreased risk of major bleeding with apixaban in mild to moderate renal impairment when compared with other anticoagulants (warfarin, aspirin, and Lovenox) as a group.

"The main criticism of the findings of our meta-analysis was inapplicability in the real world scenario, where subclinical episodes of acute kidney injury and worsening renal failure, may lead to increased anticoagulant effect and bleeding," Dr. Pandit said. This new study "exactly answers this question in a large patient population, providing sustained evidence that apixaban is safe and effective in mild to moderate renal impairment patients."

"However," Dr. Pandit concluded, "one should keep in mind limitations of the retrospective data." He also pointed out that "the efficacy and safety of apixaban is not established in patients with severe renal failure, ... as this group of patients was not studied in the ARISTOTLE trial."

Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer funded the ARISTOTLE trial. Ten coauthors reported disclosures.

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/28LbKlt JAMA Cardiol 2016.

NEW YORK - In patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and a wide range of renal function, compared to warfarin, treatment with apixaban reduces the risk of cardiovascular events, according to multinational investigators.

As Dr. Ziad Hijazi told Reuters Health by email, "Renal dysfunction is a complex issue in patients with atrial fibrillation when balancing the risk of stroke versus the risk of bleeding."

"This study," he added, "shows that apixaban, compared with warfarin, was associated with a lower risk of stroke, death, and major bleeding, regardless of changes in renal function over time. These findings may aid clinicians in the treatment decision."

In a June 15 online paper in JAMA Cardiology, Dr. Hijazi, of Uppsala University Hospital, Sweden, and colleagues report that they came to this conclusion after examining data from a clinical trial (ARISTOTLE) on more than 16,800 AF patients randomized to apixaban or warfarin.

Over the course of a year, about a quarter (26%) maintained good renal function. Renal function declined in the others, and 13.6% showed a drop of more than 20%. The decline in renal function was more rapid in patients who were older or had comorbidities.

Overall, the risks of stroke or systemic embolism, major bleeding, and mortality were greater in patients with worsening renal function (hazard ratio, 1.53 for stroke or systemic embolism, 1.56 for major bleeding, and 2.31 for mortality).

However, such patients on apixaban, compared with warfarin, consistently demonstrated a lower relative risk of stroke or systemic embolism (HR 0.80), ischemic or unspecified stroke (HR 0.88), and major bleeding (HR 0.76).

In fact, as well as showing benefit in this group of patients, the researchers conclude, "The superior efficacy and safety of apixaban as compared with warfarin were similar in patients with normal, poor, and worsening renal function."

Commenting on the findings by email, cardiologist Dr. Anil Pandit of Scottsdale, Arizona, told Reuters Health, "The study by Hijazi et al answers very important clinical questions regarding safety and efficacy of apixaban in situations of declining renal function, a common phenomenon in a real world scenario."

An earlier meta-analysis, in which Dr. Pandit was involved, found decreased risk of major bleeding with apixaban in mild to moderate renal impairment when compared with other anticoagulants (warfarin, aspirin, and Lovenox) as a group.

"The main criticism of the findings of our meta-analysis was inapplicability in the real world scenario, where subclinical episodes of acute kidney injury and worsening renal failure, may lead to increased anticoagulant effect and bleeding," Dr. Pandit said. This new study "exactly answers this question in a large patient population, providing sustained evidence that apixaban is safe and effective in mild to moderate renal impairment patients."

"However," Dr. Pandit concluded, "one should keep in mind limitations of the retrospective data." He also pointed out that "the efficacy and safety of apixaban is not established in patients with severe renal failure, ... as this group of patients was not studied in the ARISTOTLE trial."

Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer funded the ARISTOTLE trial. Ten coauthors reported disclosures.

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/28LbKlt JAMA Cardiol 2016.

NEW YORK - In patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and a wide range of renal function, compared to warfarin, treatment with apixaban reduces the risk of cardiovascular events, according to multinational investigators.

As Dr. Ziad Hijazi told Reuters Health by email, "Renal dysfunction is a complex issue in patients with atrial fibrillation when balancing the risk of stroke versus the risk of bleeding."

"This study," he added, "shows that apixaban, compared with warfarin, was associated with a lower risk of stroke, death, and major bleeding, regardless of changes in renal function over time. These findings may aid clinicians in the treatment decision."

In a June 15 online paper in JAMA Cardiology, Dr. Hijazi, of Uppsala University Hospital, Sweden, and colleagues report that they came to this conclusion after examining data from a clinical trial (ARISTOTLE) on more than 16,800 AF patients randomized to apixaban or warfarin.

Over the course of a year, about a quarter (26%) maintained good renal function. Renal function declined in the others, and 13.6% showed a drop of more than 20%. The decline in renal function was more rapid in patients who were older or had comorbidities.

Overall, the risks of stroke or systemic embolism, major bleeding, and mortality were greater in patients with worsening renal function (hazard ratio, 1.53 for stroke or systemic embolism, 1.56 for major bleeding, and 2.31 for mortality).

However, such patients on apixaban, compared with warfarin, consistently demonstrated a lower relative risk of stroke or systemic embolism (HR 0.80), ischemic or unspecified stroke (HR 0.88), and major bleeding (HR 0.76).

In fact, as well as showing benefit in this group of patients, the researchers conclude, "The superior efficacy and safety of apixaban as compared with warfarin were similar in patients with normal, poor, and worsening renal function."

Commenting on the findings by email, cardiologist Dr. Anil Pandit of Scottsdale, Arizona, told Reuters Health, "The study by Hijazi et al answers very important clinical questions regarding safety and efficacy of apixaban in situations of declining renal function, a common phenomenon in a real world scenario."

An earlier meta-analysis, in which Dr. Pandit was involved, found decreased risk of major bleeding with apixaban in mild to moderate renal impairment when compared with other anticoagulants (warfarin, aspirin, and Lovenox) as a group.

"The main criticism of the findings of our meta-analysis was inapplicability in the real world scenario, where subclinical episodes of acute kidney injury and worsening renal failure, may lead to increased anticoagulant effect and bleeding," Dr. Pandit said. This new study "exactly answers this question in a large patient population, providing sustained evidence that apixaban is safe and effective in mild to moderate renal impairment patients."

"However," Dr. Pandit concluded, "one should keep in mind limitations of the retrospective data." He also pointed out that "the efficacy and safety of apixaban is not established in patients with severe renal failure, ... as this group of patients was not studied in the ARISTOTLE trial."

Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer funded the ARISTOTLE trial. Ten coauthors reported disclosures.

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/28LbKlt JAMA Cardiol 2016.

Interhospital Transfer Handoff Practice Variance at U.S. Tertiary Care Centers

Clinical question: How do interhospital handoff practices differ among U.S. tertiary care centers, and what challenges and innovations have providers encountered?

Background: Little has been studied regarding interhospital transfers. Many centers differ in the processes they follow, and well-delineated national guidelines are lacking. Adverse events occur in up to 30% of transfers. Standardization of these handoffs has been shown to reduce preventable errors and near misses.

Study design: Survey of convenience sample of institutions.

Setting: Transfer center directors from 32 tertiary care centers in the U.S.

Synopsis: The authors surveyed directors of 32 transfer centers between 2013 and 2015. Hospitals were selected from a nationally ranked list as well as those comparable to the authors’ own institutions. The median number of patients transferred per month was 700.

Only 23% of hospitals surveyed identified significant EHR interoperability. Almost all required three-way recorded discussion between transfer center staff and referring and accepting physicians. Only 29% had available objective clinical information to share. Only 23% recorded a three-way nursing handoff, and only 32% used their EHR to document the transfer process and share clinical information among providers.

Innovations included electronic transfer notes, a standardized system of feedback to referring hospitals, automatic internal review for adverse events and delayed transfers, and use of a scorecard with key measures shared with stakeholders.

Barriers noted included complexity, acuity, and lack of continuity. Increased use of EHRs, checklists, and common processes were identified as best practices.

Limitations of the study included reliance on verbal qualitative data, a single investigator doing most of the discussions, and possible sampling bias.

Bottom line: Interhospital transfer practices at academic tertiary care centers vary widely, and optimizing and aligning practices between sending and receiving hospitals may improve efficiency and patient outcomes.

References: Herrigel DJ, Carroll M, Fanning C, Steinberg MB, Parikh A, Usher M. Interhospital transfer handoff practices among US tertiary care centers: a descriptive survey. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(6):413-417.

Clinical question: How do interhospital handoff practices differ among U.S. tertiary care centers, and what challenges and innovations have providers encountered?

Background: Little has been studied regarding interhospital transfers. Many centers differ in the processes they follow, and well-delineated national guidelines are lacking. Adverse events occur in up to 30% of transfers. Standardization of these handoffs has been shown to reduce preventable errors and near misses.

Study design: Survey of convenience sample of institutions.

Setting: Transfer center directors from 32 tertiary care centers in the U.S.

Synopsis: The authors surveyed directors of 32 transfer centers between 2013 and 2015. Hospitals were selected from a nationally ranked list as well as those comparable to the authors’ own institutions. The median number of patients transferred per month was 700.

Only 23% of hospitals surveyed identified significant EHR interoperability. Almost all required three-way recorded discussion between transfer center staff and referring and accepting physicians. Only 29% had available objective clinical information to share. Only 23% recorded a three-way nursing handoff, and only 32% used their EHR to document the transfer process and share clinical information among providers.

Innovations included electronic transfer notes, a standardized system of feedback to referring hospitals, automatic internal review for adverse events and delayed transfers, and use of a scorecard with key measures shared with stakeholders.

Barriers noted included complexity, acuity, and lack of continuity. Increased use of EHRs, checklists, and common processes were identified as best practices.

Limitations of the study included reliance on verbal qualitative data, a single investigator doing most of the discussions, and possible sampling bias.

Bottom line: Interhospital transfer practices at academic tertiary care centers vary widely, and optimizing and aligning practices between sending and receiving hospitals may improve efficiency and patient outcomes.

References: Herrigel DJ, Carroll M, Fanning C, Steinberg MB, Parikh A, Usher M. Interhospital transfer handoff practices among US tertiary care centers: a descriptive survey. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(6):413-417.

Clinical question: How do interhospital handoff practices differ among U.S. tertiary care centers, and what challenges and innovations have providers encountered?

Background: Little has been studied regarding interhospital transfers. Many centers differ in the processes they follow, and well-delineated national guidelines are lacking. Adverse events occur in up to 30% of transfers. Standardization of these handoffs has been shown to reduce preventable errors and near misses.

Study design: Survey of convenience sample of institutions.

Setting: Transfer center directors from 32 tertiary care centers in the U.S.

Synopsis: The authors surveyed directors of 32 transfer centers between 2013 and 2015. Hospitals were selected from a nationally ranked list as well as those comparable to the authors’ own institutions. The median number of patients transferred per month was 700.

Only 23% of hospitals surveyed identified significant EHR interoperability. Almost all required three-way recorded discussion between transfer center staff and referring and accepting physicians. Only 29% had available objective clinical information to share. Only 23% recorded a three-way nursing handoff, and only 32% used their EHR to document the transfer process and share clinical information among providers.

Innovations included electronic transfer notes, a standardized system of feedback to referring hospitals, automatic internal review for adverse events and delayed transfers, and use of a scorecard with key measures shared with stakeholders.

Barriers noted included complexity, acuity, and lack of continuity. Increased use of EHRs, checklists, and common processes were identified as best practices.

Limitations of the study included reliance on verbal qualitative data, a single investigator doing most of the discussions, and possible sampling bias.

Bottom line: Interhospital transfer practices at academic tertiary care centers vary widely, and optimizing and aligning practices between sending and receiving hospitals may improve efficiency and patient outcomes.

References: Herrigel DJ, Carroll M, Fanning C, Steinberg MB, Parikh A, Usher M. Interhospital transfer handoff practices among US tertiary care centers: a descriptive survey. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(6):413-417.

Oral Steroids as Good as NSAIDs for Acute Gout

Clinical question: Are oral steroids as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout?

Background: Two small trials have suggested that oral steroids are as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout. Wider acceptance of steroids as first-line agents for acute gout may require more robust evidence supporting their safety and efficacy.

Study design: Multicenter, double-blind, randomized equivalence trial.

Setting: Four EDs in Hong Kong.

Synopsis: The study included 416 patients presenting to the ED with clinically suspected acute gout who were randomized to treatment with either oral indomethacin or oral prednisolone for five days. A research investigator assessed response to therapy in the ED at 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after administration of the initial dose of medication. Patients then kept pain-assessment diaries for 14 days after discharge from the ED.

Pain scores were assessed using a visual analog scale of 0 mm (no pain) to 100 mm (worst pain the patient had experienced). Clinically significant changes in pain scores were defined as decreases of >13 mm on the visual analog scale.

The number of patients with clinically significant decreases in pain scores did not differ statistically between groups. Both groups had similar reductions in mean pain scores over the course of the study. Patients in the indomethacin group had a statistically significant increase in minor adverse events. No patients in either group had major adverse events.

Bottom line: Oral prednisolone appears to be a safe and effective first-line agent for the treatment of acute gout.

Citation: Rainer TH, Chen CH, Janssens HJEM, et al. Oral prednisolone in the treatment of acute gout. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(7):464-471.

Short Take

Rate Control as Effective as Rhythm Control in Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation

This study randomized patients with postoperative atrial fibrillation to rhythm control (using amiodarone and/or direct current cardioversion) or rate control and found neither treatment strategy has a clinical benefit over the other.

Citation: Gillinov AM, Bagiella E, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Rate control versus rhythm control for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(20):1911-1921.

Clinical question: Are oral steroids as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout?

Background: Two small trials have suggested that oral steroids are as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout. Wider acceptance of steroids as first-line agents for acute gout may require more robust evidence supporting their safety and efficacy.

Study design: Multicenter, double-blind, randomized equivalence trial.

Setting: Four EDs in Hong Kong.

Synopsis: The study included 416 patients presenting to the ED with clinically suspected acute gout who were randomized to treatment with either oral indomethacin or oral prednisolone for five days. A research investigator assessed response to therapy in the ED at 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after administration of the initial dose of medication. Patients then kept pain-assessment diaries for 14 days after discharge from the ED.

Pain scores were assessed using a visual analog scale of 0 mm (no pain) to 100 mm (worst pain the patient had experienced). Clinically significant changes in pain scores were defined as decreases of >13 mm on the visual analog scale.

The number of patients with clinically significant decreases in pain scores did not differ statistically between groups. Both groups had similar reductions in mean pain scores over the course of the study. Patients in the indomethacin group had a statistically significant increase in minor adverse events. No patients in either group had major adverse events.

Bottom line: Oral prednisolone appears to be a safe and effective first-line agent for the treatment of acute gout.

Citation: Rainer TH, Chen CH, Janssens HJEM, et al. Oral prednisolone in the treatment of acute gout. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(7):464-471.

Short Take

Rate Control as Effective as Rhythm Control in Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation

This study randomized patients with postoperative atrial fibrillation to rhythm control (using amiodarone and/or direct current cardioversion) or rate control and found neither treatment strategy has a clinical benefit over the other.

Citation: Gillinov AM, Bagiella E, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Rate control versus rhythm control for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(20):1911-1921.

Clinical question: Are oral steroids as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout?

Background: Two small trials have suggested that oral steroids are as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout. Wider acceptance of steroids as first-line agents for acute gout may require more robust evidence supporting their safety and efficacy.

Study design: Multicenter, double-blind, randomized equivalence trial.

Setting: Four EDs in Hong Kong.

Synopsis: The study included 416 patients presenting to the ED with clinically suspected acute gout who were randomized to treatment with either oral indomethacin or oral prednisolone for five days. A research investigator assessed response to therapy in the ED at 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after administration of the initial dose of medication. Patients then kept pain-assessment diaries for 14 days after discharge from the ED.

Pain scores were assessed using a visual analog scale of 0 mm (no pain) to 100 mm (worst pain the patient had experienced). Clinically significant changes in pain scores were defined as decreases of >13 mm on the visual analog scale.

The number of patients with clinically significant decreases in pain scores did not differ statistically between groups. Both groups had similar reductions in mean pain scores over the course of the study. Patients in the indomethacin group had a statistically significant increase in minor adverse events. No patients in either group had major adverse events.

Bottom line: Oral prednisolone appears to be a safe and effective first-line agent for the treatment of acute gout.

Citation: Rainer TH, Chen CH, Janssens HJEM, et al. Oral prednisolone in the treatment of acute gout. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(7):464-471.

Short Take

Rate Control as Effective as Rhythm Control in Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation

This study randomized patients with postoperative atrial fibrillation to rhythm control (using amiodarone and/or direct current cardioversion) or rate control and found neither treatment strategy has a clinical benefit over the other.

Citation: Gillinov AM, Bagiella E, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Rate control versus rhythm control for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(20):1911-1921.

Who to Blame for Surgical Readmissions?

When too many surgery patients are readmitted, the hospital can be fined by the federal government - but a new study suggests many of those readmissions are not the hospital's fault.

Many readmissions were due to issues like drug abuse or homelessness, the researchers found. Less than one in five patients returned to the hospital due to something doctors could have managed better.

"Very few were due to reasons we could control with better medical care at the index admission," said lead author Dr. Lisa McIntyre, of Harbourview Medical Center in Seattle.

McIntyre and her colleagues noted June 15 in JAMA Surgery that the U.S. government began fining hospitals in 2015 for surgery readmission rates that are higher than expected. Fines were already being imposed since 2012 for readmissions following treatments for various medical conditions.

The researchers studied the medical records of patients who were discharged from their hospital's general surgery department in 2014 or 2015 and readmitted within 30 days.

Out of the 2,100 discharges during that time, there were 173 unplanned readmissions. About 17% of those readmissions were due to injection drug use and about 15% were due to issues like homelessness or difficulty getting to follow-up appointments.

Only about 18% of readmissions - about 2% of all discharges - were due to potentially avoidable problems following surgery.

While the results are only from a single hospital, that hospital is also a safety-net facility for the local area - and McIntyre pointed out that all hospitals have some amount of disadvantaged patients.

"To be able to affect this rate, there are going to need to be new interventions that require money and a more global care package of each individual patient that doesn't stop at discharge," said McIntyre, who is also affiliated with the University of Washington.

Being female, having diabetes, having sepsis upon admission, being in the ICU and being discharged to respite care were all tied to an increased risk of readmission, the researchers found.

The results raise the question of whether readmission rates are valuable measures of surgical quality, write Drs. Alexander Schwed and Christian de Virgilio of the University of California, Los Angeles in an editorial.

Some would argue that readmitting patients is a sound medical decision that is tied to lower risks of death, they write.

"Should such an inexact marker of quality be used to financially penalize hospitals?" they ask. "Health services researchers (need to find) a better marker for surgical quality that is reliably calculable and clinically useful."

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/28Km3aH and http://bit.ly/28Km3Ye JAMA Surgery 2016.

When too many surgery patients are readmitted, the hospital can be fined by the federal government - but a new study suggests many of those readmissions are not the hospital's fault.

Many readmissions were due to issues like drug abuse or homelessness, the researchers found. Less than one in five patients returned to the hospital due to something doctors could have managed better.

"Very few were due to reasons we could control with better medical care at the index admission," said lead author Dr. Lisa McIntyre, of Harbourview Medical Center in Seattle.

McIntyre and her colleagues noted June 15 in JAMA Surgery that the U.S. government began fining hospitals in 2015 for surgery readmission rates that are higher than expected. Fines were already being imposed since 2012 for readmissions following treatments for various medical conditions.

The researchers studied the medical records of patients who were discharged from their hospital's general surgery department in 2014 or 2015 and readmitted within 30 days.

Out of the 2,100 discharges during that time, there were 173 unplanned readmissions. About 17% of those readmissions were due to injection drug use and about 15% were due to issues like homelessness or difficulty getting to follow-up appointments.

Only about 18% of readmissions - about 2% of all discharges - were due to potentially avoidable problems following surgery.

While the results are only from a single hospital, that hospital is also a safety-net facility for the local area - and McIntyre pointed out that all hospitals have some amount of disadvantaged patients.

"To be able to affect this rate, there are going to need to be new interventions that require money and a more global care package of each individual patient that doesn't stop at discharge," said McIntyre, who is also affiliated with the University of Washington.

Being female, having diabetes, having sepsis upon admission, being in the ICU and being discharged to respite care were all tied to an increased risk of readmission, the researchers found.

The results raise the question of whether readmission rates are valuable measures of surgical quality, write Drs. Alexander Schwed and Christian de Virgilio of the University of California, Los Angeles in an editorial.

Some would argue that readmitting patients is a sound medical decision that is tied to lower risks of death, they write.

"Should such an inexact marker of quality be used to financially penalize hospitals?" they ask. "Health services researchers (need to find) a better marker for surgical quality that is reliably calculable and clinically useful."

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/28Km3aH and http://bit.ly/28Km3Ye JAMA Surgery 2016.

When too many surgery patients are readmitted, the hospital can be fined by the federal government - but a new study suggests many of those readmissions are not the hospital's fault.

Many readmissions were due to issues like drug abuse or homelessness, the researchers found. Less than one in five patients returned to the hospital due to something doctors could have managed better.

"Very few were due to reasons we could control with better medical care at the index admission," said lead author Dr. Lisa McIntyre, of Harbourview Medical Center in Seattle.

McIntyre and her colleagues noted June 15 in JAMA Surgery that the U.S. government began fining hospitals in 2015 for surgery readmission rates that are higher than expected. Fines were already being imposed since 2012 for readmissions following treatments for various medical conditions.

The researchers studied the medical records of patients who were discharged from their hospital's general surgery department in 2014 or 2015 and readmitted within 30 days.

Out of the 2,100 discharges during that time, there were 173 unplanned readmissions. About 17% of those readmissions were due to injection drug use and about 15% were due to issues like homelessness or difficulty getting to follow-up appointments.

Only about 18% of readmissions - about 2% of all discharges - were due to potentially avoidable problems following surgery.

While the results are only from a single hospital, that hospital is also a safety-net facility for the local area - and McIntyre pointed out that all hospitals have some amount of disadvantaged patients.

"To be able to affect this rate, there are going to need to be new interventions that require money and a more global care package of each individual patient that doesn't stop at discharge," said McIntyre, who is also affiliated with the University of Washington.

Being female, having diabetes, having sepsis upon admission, being in the ICU and being discharged to respite care were all tied to an increased risk of readmission, the researchers found.

The results raise the question of whether readmission rates are valuable measures of surgical quality, write Drs. Alexander Schwed and Christian de Virgilio of the University of California, Los Angeles in an editorial.

Some would argue that readmitting patients is a sound medical decision that is tied to lower risks of death, they write.

"Should such an inexact marker of quality be used to financially penalize hospitals?" they ask. "Health services researchers (need to find) a better marker for surgical quality that is reliably calculable and clinically useful."

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/28Km3aH and http://bit.ly/28Km3Ye JAMA Surgery 2016.

SHM SPARK Helps Bridge Gap for Hospitalist MOC Exam Prep

SHM SPARK delivers 175 vignette-style, multiple-choice questions that bridge the primary knowledge gaps found within existing MOC exam-preparation products. It offers up to 10.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits of CME. Content areas covered include:

- Palliative care, ethics, and decision making

- Patient safety

- Perioperative care and consultative co-management

- Quality, cost, and clinical reasoning

The Hospitalist recently spoke with three SHM SPARK users about its impact on their exam-preparation efforts: Louis O’Boyle, DO, SFHM, CLHM, medical director of Advanced Inpatient Medicine, a hospitalist management company in Lakeville, Pa.; Timothy Crone, MD, SFHM, medical director of Enterprise Intelligence and Analytics and former vice-chairman of the Department of Hospital Medicine at Cleveland Clinic; and Aroop Pal, MD, FHM, hospitalist, associate professor, and program director of transitions of care services at University of Kansas Medical Center.

Question: Why did you choose to purchase SHM SPARK?

Dr. O’Boyle: I was expecting the FPHM exam to be more challenging than the traditional exam, so I wanted to get as much help as possible, particularly in those areas that are less utilized in day-to-day hospitalist practice. This exam covered the 40% or so that is not covered in a typical review course.

Dr. Crone: I was selected to receive SHM SPARK as a test user, but had I not been, I probably would have purchased it as there was not another single tool that addressed the content gap preparing for the exam that SHM SPARK did. On HMX and in conversations with other hospitalists, I was aware of “collections” of tools, like books and websites, that people had put together to review information not covered in MKSAP or other standard test-prep materials. SHM SPARK brought that content together in a single space, which allowed me to take a systematic approach to reviewing the content areas covered as opposed to a potentially incomplete, piecemeal approach.

Dr. Pal: There are no board review products focused on the 40% of the FPHM exam not based on traditional clinical knowledge. Thus, it made sense to give SHM SPARK a try, especially since it was affordable for members.

Q: During your preparation, what was the most useful aspect of SHM SPARK?

Dr. Crone: I find that working through computer-based questions similar in format to the actual exam is most helpful to me. Both in terms of knowledge acquisition and comfort level with the exam itself, the “context-dependent learning” aspect is important for me. SHM SPARK allowed me to work through its content areas in that way and also helped me identify and correct gaps in my knowledge as opposed to guessing what was important and searching for source material on my own.

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK helped frame how quality and patient safety questions would or could be posed on the FPHM exam. This made it helpful to determine what content is fair game for the exam and the key competencies ABIM was focusing on—especially since traditional board review materials do not cover as much quality-specific content.

Dr. O’Boyle: The most useful aspects were the topics that are not encountered specifically in everyday practice, such as the sections on quality, cost, and clinical reasoning, as well as patient safety.

Q: After taking the exam, in retrospect, how effective was SHM SPARK in preparing you?

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK was valuable to me and worth the time and effort. The board exam itself is a little bit of a blur; if nothing else, it helped me identify areas that I needed more information on and reinforced some knowledge I had prior to taking the exam.

Dr. O’Boyle: The SHM SPARK review absolutely helped me perform well on the sections that were covered. I think it is almost essential to prepare for the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine exam.

Dr. Crone: I passed, so I’d label that effective! In some cases, using SHM SPARK, I scored 90% or better on a first pass on questions with no review; that has not been my experience with MKSAP or Med Study questions. The only recommendation I would have is to make some of the questions a bit more rigorous. However, SHM SPARK clearly met a need nothing else did.

Q: If you were to tell a fellow hospitalist one thing about SHM SPARK, what would it be?

Dr. O’Boyle: I encourage everyone to purchase it. It is an excellent resource guide. The way the exam is currently designed, you may need the additional 40% of exam content covered by SHM SPARK in order to pass. By that, I mean that some of the medical questions were so complicated and cumbersome that they were at the specialist level and not at all representative of what a typical hospitalist routinely encounters, in my opinion. Therefore, knowing this portion of the exam content through SHM SPARK made up for the questions that I felt should not have been fair game. I, for one, would likely not have passed without SHM SPARK.

Dr. Crone: It’s worth the time, effort, and cost. Although much or most of the exam content was couched in a clinical scenario, substantive content existed on the MOC exam around these subject areas. To not use some form of structured approach to covering this material would have been a mistake.

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK is extremely valuable if you plan to take the FPHM exam as it highlights many areas not covered by any other review material. It offers great CME, too! TH

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications specialist.

More Info

For more information about how SHM SPARK can help you master your preparation for the FPHM MOC exam this fall, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/SPARK.

SHM SPARK delivers 175 vignette-style, multiple-choice questions that bridge the primary knowledge gaps found within existing MOC exam-preparation products. It offers up to 10.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits of CME. Content areas covered include:

- Palliative care, ethics, and decision making

- Patient safety

- Perioperative care and consultative co-management

- Quality, cost, and clinical reasoning

The Hospitalist recently spoke with three SHM SPARK users about its impact on their exam-preparation efforts: Louis O’Boyle, DO, SFHM, CLHM, medical director of Advanced Inpatient Medicine, a hospitalist management company in Lakeville, Pa.; Timothy Crone, MD, SFHM, medical director of Enterprise Intelligence and Analytics and former vice-chairman of the Department of Hospital Medicine at Cleveland Clinic; and Aroop Pal, MD, FHM, hospitalist, associate professor, and program director of transitions of care services at University of Kansas Medical Center.

Question: Why did you choose to purchase SHM SPARK?

Dr. O’Boyle: I was expecting the FPHM exam to be more challenging than the traditional exam, so I wanted to get as much help as possible, particularly in those areas that are less utilized in day-to-day hospitalist practice. This exam covered the 40% or so that is not covered in a typical review course.

Dr. Crone: I was selected to receive SHM SPARK as a test user, but had I not been, I probably would have purchased it as there was not another single tool that addressed the content gap preparing for the exam that SHM SPARK did. On HMX and in conversations with other hospitalists, I was aware of “collections” of tools, like books and websites, that people had put together to review information not covered in MKSAP or other standard test-prep materials. SHM SPARK brought that content together in a single space, which allowed me to take a systematic approach to reviewing the content areas covered as opposed to a potentially incomplete, piecemeal approach.

Dr. Pal: There are no board review products focused on the 40% of the FPHM exam not based on traditional clinical knowledge. Thus, it made sense to give SHM SPARK a try, especially since it was affordable for members.

Q: During your preparation, what was the most useful aspect of SHM SPARK?

Dr. Crone: I find that working through computer-based questions similar in format to the actual exam is most helpful to me. Both in terms of knowledge acquisition and comfort level with the exam itself, the “context-dependent learning” aspect is important for me. SHM SPARK allowed me to work through its content areas in that way and also helped me identify and correct gaps in my knowledge as opposed to guessing what was important and searching for source material on my own.

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK helped frame how quality and patient safety questions would or could be posed on the FPHM exam. This made it helpful to determine what content is fair game for the exam and the key competencies ABIM was focusing on—especially since traditional board review materials do not cover as much quality-specific content.

Dr. O’Boyle: The most useful aspects were the topics that are not encountered specifically in everyday practice, such as the sections on quality, cost, and clinical reasoning, as well as patient safety.

Q: After taking the exam, in retrospect, how effective was SHM SPARK in preparing you?

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK was valuable to me and worth the time and effort. The board exam itself is a little bit of a blur; if nothing else, it helped me identify areas that I needed more information on and reinforced some knowledge I had prior to taking the exam.

Dr. O’Boyle: The SHM SPARK review absolutely helped me perform well on the sections that were covered. I think it is almost essential to prepare for the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine exam.

Dr. Crone: I passed, so I’d label that effective! In some cases, using SHM SPARK, I scored 90% or better on a first pass on questions with no review; that has not been my experience with MKSAP or Med Study questions. The only recommendation I would have is to make some of the questions a bit more rigorous. However, SHM SPARK clearly met a need nothing else did.

Q: If you were to tell a fellow hospitalist one thing about SHM SPARK, what would it be?

Dr. O’Boyle: I encourage everyone to purchase it. It is an excellent resource guide. The way the exam is currently designed, you may need the additional 40% of exam content covered by SHM SPARK in order to pass. By that, I mean that some of the medical questions were so complicated and cumbersome that they were at the specialist level and not at all representative of what a typical hospitalist routinely encounters, in my opinion. Therefore, knowing this portion of the exam content through SHM SPARK made up for the questions that I felt should not have been fair game. I, for one, would likely not have passed without SHM SPARK.

Dr. Crone: It’s worth the time, effort, and cost. Although much or most of the exam content was couched in a clinical scenario, substantive content existed on the MOC exam around these subject areas. To not use some form of structured approach to covering this material would have been a mistake.

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK is extremely valuable if you plan to take the FPHM exam as it highlights many areas not covered by any other review material. It offers great CME, too! TH

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications specialist.

More Info

For more information about how SHM SPARK can help you master your preparation for the FPHM MOC exam this fall, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/SPARK.

SHM SPARK delivers 175 vignette-style, multiple-choice questions that bridge the primary knowledge gaps found within existing MOC exam-preparation products. It offers up to 10.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits of CME. Content areas covered include:

- Palliative care, ethics, and decision making

- Patient safety

- Perioperative care and consultative co-management

- Quality, cost, and clinical reasoning

The Hospitalist recently spoke with three SHM SPARK users about its impact on their exam-preparation efforts: Louis O’Boyle, DO, SFHM, CLHM, medical director of Advanced Inpatient Medicine, a hospitalist management company in Lakeville, Pa.; Timothy Crone, MD, SFHM, medical director of Enterprise Intelligence and Analytics and former vice-chairman of the Department of Hospital Medicine at Cleveland Clinic; and Aroop Pal, MD, FHM, hospitalist, associate professor, and program director of transitions of care services at University of Kansas Medical Center.

Question: Why did you choose to purchase SHM SPARK?

Dr. O’Boyle: I was expecting the FPHM exam to be more challenging than the traditional exam, so I wanted to get as much help as possible, particularly in those areas that are less utilized in day-to-day hospitalist practice. This exam covered the 40% or so that is not covered in a typical review course.

Dr. Crone: I was selected to receive SHM SPARK as a test user, but had I not been, I probably would have purchased it as there was not another single tool that addressed the content gap preparing for the exam that SHM SPARK did. On HMX and in conversations with other hospitalists, I was aware of “collections” of tools, like books and websites, that people had put together to review information not covered in MKSAP or other standard test-prep materials. SHM SPARK brought that content together in a single space, which allowed me to take a systematic approach to reviewing the content areas covered as opposed to a potentially incomplete, piecemeal approach.

Dr. Pal: There are no board review products focused on the 40% of the FPHM exam not based on traditional clinical knowledge. Thus, it made sense to give SHM SPARK a try, especially since it was affordable for members.

Q: During your preparation, what was the most useful aspect of SHM SPARK?

Dr. Crone: I find that working through computer-based questions similar in format to the actual exam is most helpful to me. Both in terms of knowledge acquisition and comfort level with the exam itself, the “context-dependent learning” aspect is important for me. SHM SPARK allowed me to work through its content areas in that way and also helped me identify and correct gaps in my knowledge as opposed to guessing what was important and searching for source material on my own.

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK helped frame how quality and patient safety questions would or could be posed on the FPHM exam. This made it helpful to determine what content is fair game for the exam and the key competencies ABIM was focusing on—especially since traditional board review materials do not cover as much quality-specific content.

Dr. O’Boyle: The most useful aspects were the topics that are not encountered specifically in everyday practice, such as the sections on quality, cost, and clinical reasoning, as well as patient safety.

Q: After taking the exam, in retrospect, how effective was SHM SPARK in preparing you?

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK was valuable to me and worth the time and effort. The board exam itself is a little bit of a blur; if nothing else, it helped me identify areas that I needed more information on and reinforced some knowledge I had prior to taking the exam.

Dr. O’Boyle: The SHM SPARK review absolutely helped me perform well on the sections that were covered. I think it is almost essential to prepare for the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine exam.

Dr. Crone: I passed, so I’d label that effective! In some cases, using SHM SPARK, I scored 90% or better on a first pass on questions with no review; that has not been my experience with MKSAP or Med Study questions. The only recommendation I would have is to make some of the questions a bit more rigorous. However, SHM SPARK clearly met a need nothing else did.

Q: If you were to tell a fellow hospitalist one thing about SHM SPARK, what would it be?

Dr. O’Boyle: I encourage everyone to purchase it. It is an excellent resource guide. The way the exam is currently designed, you may need the additional 40% of exam content covered by SHM SPARK in order to pass. By that, I mean that some of the medical questions were so complicated and cumbersome that they were at the specialist level and not at all representative of what a typical hospitalist routinely encounters, in my opinion. Therefore, knowing this portion of the exam content through SHM SPARK made up for the questions that I felt should not have been fair game. I, for one, would likely not have passed without SHM SPARK.

Dr. Crone: It’s worth the time, effort, and cost. Although much or most of the exam content was couched in a clinical scenario, substantive content existed on the MOC exam around these subject areas. To not use some form of structured approach to covering this material would have been a mistake.

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK is extremely valuable if you plan to take the FPHM exam as it highlights many areas not covered by any other review material. It offers great CME, too! TH

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications specialist.

More Info

For more information about how SHM SPARK can help you master your preparation for the FPHM MOC exam this fall, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/SPARK.

Measure Hospitalist Engagement with SHM’s Engagement Benchmarking Service

One of the most important questions for leaders of hospital medicine groups is, “How can I measure the level of engagement of my hospitalists?” Measuring hospitalist engagement can be difficult, and many leaders are not satisfied with the tools they currently have at their disposal.

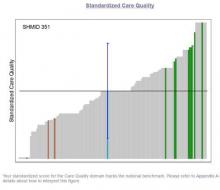

SHM is here to help. SHM developed an Engagement Benchmarking Service to evaluate relationships with leaders, care quality, autonomy, effective motivation, burnout risk, and more. You can see your standardized score in the various domains and where it falls within the national benchmark. This helps you know what is working well and identifies the areas for improvement in your hospital medicine group.

More than 80% of respondents from 2015 indicated that they will utilize the service again and plan to recommend it to a colleague. Help ensure hospitalists are engaged in your HM group by registering now for the next cohort at www.hospitalmedicine.org/pmad3.

One of the most important questions for leaders of hospital medicine groups is, “How can I measure the level of engagement of my hospitalists?” Measuring hospitalist engagement can be difficult, and many leaders are not satisfied with the tools they currently have at their disposal.

SHM is here to help. SHM developed an Engagement Benchmarking Service to evaluate relationships with leaders, care quality, autonomy, effective motivation, burnout risk, and more. You can see your standardized score in the various domains and where it falls within the national benchmark. This helps you know what is working well and identifies the areas for improvement in your hospital medicine group.

More than 80% of respondents from 2015 indicated that they will utilize the service again and plan to recommend it to a colleague. Help ensure hospitalists are engaged in your HM group by registering now for the next cohort at www.hospitalmedicine.org/pmad3.

One of the most important questions for leaders of hospital medicine groups is, “How can I measure the level of engagement of my hospitalists?” Measuring hospitalist engagement can be difficult, and many leaders are not satisfied with the tools they currently have at their disposal.

SHM is here to help. SHM developed an Engagement Benchmarking Service to evaluate relationships with leaders, care quality, autonomy, effective motivation, burnout risk, and more. You can see your standardized score in the various domains and where it falls within the national benchmark. This helps you know what is working well and identifies the areas for improvement in your hospital medicine group.

More than 80% of respondents from 2015 indicated that they will utilize the service again and plan to recommend it to a colleague. Help ensure hospitalists are engaged in your HM group by registering now for the next cohort at www.hospitalmedicine.org/pmad3.

Key Medicare Fund Could Exhaust Reserves in 2028: Trustees

WASHINGTON—The U.S. federal program that pays elderly Americans' hospital bills will exhaust reserves in 2028, two years sooner than last year's estimate, trustees of the program said on Wednesday.

In their annual financial review, the trustees also said that the combined Social Security and disability trust fund reserves are estimated to run out in 2034, the same projection as last year.

The Medicare program's trust fund for hospital care is still scheduled to have sufficient funding 11 years longer than the estimate given before the Affordable Care Act was passed, the trustees said.

They put the shortening of the timeline down to changes in estimates of income and cost, particularly in the near term.

A depletion in funds available for Medicare and Social Security does not mean the programs would suddenly stop. At the current rate of payroll tax collections, Medicare would be able to cover 87 percent of costs in 2028. This would fall to 79 percent by 2043 and then gradually increase.

Social Security would be able to pay about three-quarters of scheduled benefits from 2034 to 2090, the trustees said.

WASHINGTON—The U.S. federal program that pays elderly Americans' hospital bills will exhaust reserves in 2028, two years sooner than last year's estimate, trustees of the program said on Wednesday.

In their annual financial review, the trustees also said that the combined Social Security and disability trust fund reserves are estimated to run out in 2034, the same projection as last year.

The Medicare program's trust fund for hospital care is still scheduled to have sufficient funding 11 years longer than the estimate given before the Affordable Care Act was passed, the trustees said.

They put the shortening of the timeline down to changes in estimates of income and cost, particularly in the near term.

A depletion in funds available for Medicare and Social Security does not mean the programs would suddenly stop. At the current rate of payroll tax collections, Medicare would be able to cover 87 percent of costs in 2028. This would fall to 79 percent by 2043 and then gradually increase.

Social Security would be able to pay about three-quarters of scheduled benefits from 2034 to 2090, the trustees said.

WASHINGTON—The U.S. federal program that pays elderly Americans' hospital bills will exhaust reserves in 2028, two years sooner than last year's estimate, trustees of the program said on Wednesday.

In their annual financial review, the trustees also said that the combined Social Security and disability trust fund reserves are estimated to run out in 2034, the same projection as last year.

The Medicare program's trust fund for hospital care is still scheduled to have sufficient funding 11 years longer than the estimate given before the Affordable Care Act was passed, the trustees said.

They put the shortening of the timeline down to changes in estimates of income and cost, particularly in the near term.

A depletion in funds available for Medicare and Social Security does not mean the programs would suddenly stop. At the current rate of payroll tax collections, Medicare would be able to cover 87 percent of costs in 2028. This would fall to 79 percent by 2043 and then gradually increase.

Social Security would be able to pay about three-quarters of scheduled benefits from 2034 to 2090, the trustees said.

Lesson in Improper Allocations, Unaccounted for NP/PA Contributions

I visited during a hot Florida summer in the mid 1990s and could readily see that the practice was great in most respects. The large multispecialty group had recruited talented hospitalists and had put in place effective operational practices. All seemed to be going well, but inappropriate overhead allocation was undermining the success of their efforts.

The multispecialty group employing the hospitalists used the same formula to allocate overhead to the hospitalists that was in place for other specialties. And compensation was essentially each doctor’s collections minus overhead, leaving the hospitalists with annual compensation much lower than they could reasonably expect. With the group deducting from hospitalist collections the same overhead expenses charged to other specialties, including a share of outpatient buildings, staff, and supplies, the hospitalists were paying a lot for services they weren’t using. This group corrected the errors but not until some talented doctors had resigned because of the compensation formula.

This was a common mistake made by multispecialty groups that employed hospitalists years ago. Today, nearly all such groups assess an appropriately smaller portion of overhead to hospitalists than office-based doctors.

Typical Hospitalist Overhead

It is still tricky to correctly assess and allocate hospitalist overhead. This meaningfully influences the apparent total cost of the program and hence the amount of support paid by the hospital or other entity. (This support is often referred to as a “subsidy,” though I don’t care for that term because of its negative connotation.)

For example, costs for billing and collections services, malpractice insurance, temporary staffing (locums), and an overhead allocation that pays for things like the salaries of medical group administrators and clerical staff may or may not be attributed to the hospitalist budget or “cost center.” This is one of several factors that make it awfully tricky to compare the total costs and/or hospital financial support between different hospitalist groups.

SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report includes detailed instructions regarding which expenses the survey respondents should include as overhead costs, but I think it’s safe to assume that not all responses are fully compliant. I’m confident there is a meaningful amount of “noise” in these figures. Numbers like the median financial support per FTE hospitalist per year ($156,063 in the 2014 report) should only be used as a guideline and not a precise number that might apply in your setting. My reasoning is that the collections rate and compensation amount can vary tremendously from one practice to another and will typically have a far larger influence on the amount of financial support provided by the hospital than which expenses are or aren’t included as overhead. But I am confining this discussion to the latter.

APC Costs: One Factor Driving Increased Support

SHM has been surveying the financial support per physician FTE for about 15 years, and it has shown a steady increase. It was about $60,000 per FTE annually when first surveyed in the late 1990s; it has gone up every survey since. The best explanation for this seems to an increase in hospitalist compensation while production and revenue have remained relatively flat.

There likely are many other factors in play. One important one is physician assistant and nurse practitioner costs. The survey divides the total annual support provided to the whole hospitalist practice by the total number of physician FTEs. NPs and PAs are becoming more common in hospitalist groups; 65% of groups included them in 2014, up from 54% in 2012. Yet the cost of employing them, primarily salary and benefits, appears in the numerator but not the denominator of the support per physician FTE figure.

This means a group that adds NP/PA staffing, which typically requires an accompanying increase in hospital financial support, while maintaining the same number of physician FTEs will show an increase in hospital support per physician FTE. But this fails to capture that the practice’s work product (i.e., patients seen) has increased as a result of increasing its clinical staff.

This is a tricky issue to fix. SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, which manages the survey, is aware of the issue and may make future adjustments to account for it. The best method might be to convert total staffing by physicians and NP/PAs into physician-equivalent FTEs (I described one method for doing this in my August 2009 column titled “Volume Variables”) or some other method that clearly accounts for both physician and NP/PA staffing levels. Other alternatives would be to divide the annual support by the number of billed encounters or some other measure of “work output” or to report percent of the total practice revenue that comes from hospital support versus professional fee collections and other sources.

Why Allocation of NP/PA Costs and FTEs Matter

Another way to think of this issue is that including NP/PA costs but not their work (FTEs) in the financial support per FTE figure overlooks the important work they can do for a hospitalist practice. And it can lead one to conclude hospitals’ costs per clinician FTE are rising faster than is actually the case.

This is only one of the tricky issues in accurately understanding hospitalist overhead and costs to the hospital they serve. TH

I visited during a hot Florida summer in the mid 1990s and could readily see that the practice was great in most respects. The large multispecialty group had recruited talented hospitalists and had put in place effective operational practices. All seemed to be going well, but inappropriate overhead allocation was undermining the success of their efforts.

The multispecialty group employing the hospitalists used the same formula to allocate overhead to the hospitalists that was in place for other specialties. And compensation was essentially each doctor’s collections minus overhead, leaving the hospitalists with annual compensation much lower than they could reasonably expect. With the group deducting from hospitalist collections the same overhead expenses charged to other specialties, including a share of outpatient buildings, staff, and supplies, the hospitalists were paying a lot for services they weren’t using. This group corrected the errors but not until some talented doctors had resigned because of the compensation formula.

This was a common mistake made by multispecialty groups that employed hospitalists years ago. Today, nearly all such groups assess an appropriately smaller portion of overhead to hospitalists than office-based doctors.

Typical Hospitalist Overhead

It is still tricky to correctly assess and allocate hospitalist overhead. This meaningfully influences the apparent total cost of the program and hence the amount of support paid by the hospital or other entity. (This support is often referred to as a “subsidy,” though I don’t care for that term because of its negative connotation.)

For example, costs for billing and collections services, malpractice insurance, temporary staffing (locums), and an overhead allocation that pays for things like the salaries of medical group administrators and clerical staff may or may not be attributed to the hospitalist budget or “cost center.” This is one of several factors that make it awfully tricky to compare the total costs and/or hospital financial support between different hospitalist groups.

SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report includes detailed instructions regarding which expenses the survey respondents should include as overhead costs, but I think it’s safe to assume that not all responses are fully compliant. I’m confident there is a meaningful amount of “noise” in these figures. Numbers like the median financial support per FTE hospitalist per year ($156,063 in the 2014 report) should only be used as a guideline and not a precise number that might apply in your setting. My reasoning is that the collections rate and compensation amount can vary tremendously from one practice to another and will typically have a far larger influence on the amount of financial support provided by the hospital than which expenses are or aren’t included as overhead. But I am confining this discussion to the latter.

APC Costs: One Factor Driving Increased Support

SHM has been surveying the financial support per physician FTE for about 15 years, and it has shown a steady increase. It was about $60,000 per FTE annually when first surveyed in the late 1990s; it has gone up every survey since. The best explanation for this seems to an increase in hospitalist compensation while production and revenue have remained relatively flat.

There likely are many other factors in play. One important one is physician assistant and nurse practitioner costs. The survey divides the total annual support provided to the whole hospitalist practice by the total number of physician FTEs. NPs and PAs are becoming more common in hospitalist groups; 65% of groups included them in 2014, up from 54% in 2012. Yet the cost of employing them, primarily salary and benefits, appears in the numerator but not the denominator of the support per physician FTE figure.

This means a group that adds NP/PA staffing, which typically requires an accompanying increase in hospital financial support, while maintaining the same number of physician FTEs will show an increase in hospital support per physician FTE. But this fails to capture that the practice’s work product (i.e., patients seen) has increased as a result of increasing its clinical staff.

This is a tricky issue to fix. SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, which manages the survey, is aware of the issue and may make future adjustments to account for it. The best method might be to convert total staffing by physicians and NP/PAs into physician-equivalent FTEs (I described one method for doing this in my August 2009 column titled “Volume Variables”) or some other method that clearly accounts for both physician and NP/PA staffing levels. Other alternatives would be to divide the annual support by the number of billed encounters or some other measure of “work output” or to report percent of the total practice revenue that comes from hospital support versus professional fee collections and other sources.

Why Allocation of NP/PA Costs and FTEs Matter

Another way to think of this issue is that including NP/PA costs but not their work (FTEs) in the financial support per FTE figure overlooks the important work they can do for a hospitalist practice. And it can lead one to conclude hospitals’ costs per clinician FTE are rising faster than is actually the case.

This is only one of the tricky issues in accurately understanding hospitalist overhead and costs to the hospital they serve. TH

I visited during a hot Florida summer in the mid 1990s and could readily see that the practice was great in most respects. The large multispecialty group had recruited talented hospitalists and had put in place effective operational practices. All seemed to be going well, but inappropriate overhead allocation was undermining the success of their efforts.

The multispecialty group employing the hospitalists used the same formula to allocate overhead to the hospitalists that was in place for other specialties. And compensation was essentially each doctor’s collections minus overhead, leaving the hospitalists with annual compensation much lower than they could reasonably expect. With the group deducting from hospitalist collections the same overhead expenses charged to other specialties, including a share of outpatient buildings, staff, and supplies, the hospitalists were paying a lot for services they weren’t using. This group corrected the errors but not until some talented doctors had resigned because of the compensation formula.

This was a common mistake made by multispecialty groups that employed hospitalists years ago. Today, nearly all such groups assess an appropriately smaller portion of overhead to hospitalists than office-based doctors.

Typical Hospitalist Overhead

It is still tricky to correctly assess and allocate hospitalist overhead. This meaningfully influences the apparent total cost of the program and hence the amount of support paid by the hospital or other entity. (This support is often referred to as a “subsidy,” though I don’t care for that term because of its negative connotation.)

For example, costs for billing and collections services, malpractice insurance, temporary staffing (locums), and an overhead allocation that pays for things like the salaries of medical group administrators and clerical staff may or may not be attributed to the hospitalist budget or “cost center.” This is one of several factors that make it awfully tricky to compare the total costs and/or hospital financial support between different hospitalist groups.

SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report includes detailed instructions regarding which expenses the survey respondents should include as overhead costs, but I think it’s safe to assume that not all responses are fully compliant. I’m confident there is a meaningful amount of “noise” in these figures. Numbers like the median financial support per FTE hospitalist per year ($156,063 in the 2014 report) should only be used as a guideline and not a precise number that might apply in your setting. My reasoning is that the collections rate and compensation amount can vary tremendously from one practice to another and will typically have a far larger influence on the amount of financial support provided by the hospital than which expenses are or aren’t included as overhead. But I am confining this discussion to the latter.

APC Costs: One Factor Driving Increased Support

SHM has been surveying the financial support per physician FTE for about 15 years, and it has shown a steady increase. It was about $60,000 per FTE annually when first surveyed in the late 1990s; it has gone up every survey since. The best explanation for this seems to an increase in hospitalist compensation while production and revenue have remained relatively flat.

There likely are many other factors in play. One important one is physician assistant and nurse practitioner costs. The survey divides the total annual support provided to the whole hospitalist practice by the total number of physician FTEs. NPs and PAs are becoming more common in hospitalist groups; 65% of groups included them in 2014, up from 54% in 2012. Yet the cost of employing them, primarily salary and benefits, appears in the numerator but not the denominator of the support per physician FTE figure.

This means a group that adds NP/PA staffing, which typically requires an accompanying increase in hospital financial support, while maintaining the same number of physician FTEs will show an increase in hospital support per physician FTE. But this fails to capture that the practice’s work product (i.e., patients seen) has increased as a result of increasing its clinical staff.

This is a tricky issue to fix. SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, which manages the survey, is aware of the issue and may make future adjustments to account for it. The best method might be to convert total staffing by physicians and NP/PAs into physician-equivalent FTEs (I described one method for doing this in my August 2009 column titled “Volume Variables”) or some other method that clearly accounts for both physician and NP/PA staffing levels. Other alternatives would be to divide the annual support by the number of billed encounters or some other measure of “work output” or to report percent of the total practice revenue that comes from hospital support versus professional fee collections and other sources.

Why Allocation of NP/PA Costs and FTEs Matter

Another way to think of this issue is that including NP/PA costs but not their work (FTEs) in the financial support per FTE figure overlooks the important work they can do for a hospitalist practice. And it can lead one to conclude hospitals’ costs per clinician FTE are rising faster than is actually the case.

This is only one of the tricky issues in accurately understanding hospitalist overhead and costs to the hospital they serve. TH

LETTER: Emory Hospital Medicine’s Growth Sparks Establishment of NP, PA Career Track

Due to many reasons, the healthcare paradigm has shifted, dictating alternative staffing models to manage the burgeoning inpatient census of hospital-based physicians. Herein, we will briefly describe the Emory University Division of Hospital Medicine (EDHM) approach to utilizing advanced practice providers (APPs) in the care of inpatients and summarize key components of the program that improve sustainability for providers.

The EDHM in Atlanta matriculated APPs into its service in 2004. Currently, there are 22 APPs across all Emory HM sites. The largest group is at Emory University Hospital Midtown (EUHM).

At EUHM, the addition of a renal service created concern for increased workload for the physicians. APPs were recruited to bridge the gap in 2011. Initially, the role was ill-defined, but over time, with physician and administrative leadership buy-in and support, the role has evolved. Currently at EUHM, APPs are practicing in other HM services, allowing them to practice near or at the top of their scope of practice. The 12 hospitalist APPs at EUHM practice in four roles: nocturnist, frontline provider in the observation unit, dedicated renal service, and generalist on an overflow team.

Along with the rapid growth of APPs on the service came the need for structured leadership, improved onboarding procedures, competency maintenance, advocacy, and professional development activities. Essentially, we needed to create a career track parallel to that of the physicians without compromising the portion of our scopes of our practice that overlap (i.e., patient care) while supporting our regulatory differences.

The professional development plans incorporated findings from APP exit interviews at the University of Maryland Medical Center highlighting the following retention issues:1

- Length of time for credentialing

- Role clarity

- Inadequate clinical orientation

- Feelings of clinical incompetence

- Feelings of isolation

With the instillation of APP leadership, the team created a comprehensive APP program. The Hospital Medicine APP program at EUHM includes the following components:

- APP representation at monthly clinical operation meetings and quarterly education council meetings to ensure that APP competency and regulatory issues are always represented.

- Orientation personally tailored to the APP’s level of clinical expertise, with a post-orientation meeting with leadership and remediation, if needed.

- APP incentives to teach NP or PA students, conduct in-services, join committees, or participate in other leadership opportunities.

- APPs invited to attend and/or present at all divisional small and large group learning opportunities (e.g., Grand Rounds, Lunch and Learn, Journal Club).

- APPs allocated time and space to meet and discuss practice issues.

- Newly developed Mini-Hospitalist Academy, which offers monthly workshops to all hospitalist physicians and APPs, from novice to expert.

- Dedicated APP Ongoing Professional Performance Evaluation (OPPE) program.

- In addition to the annual monetary support offered for educational opportunities, the division offers an annual Faculty Development Award. This award is by application for eligible educational opportunities; APPs are welcome to apply and have consistently been awarded support to pursue myriad opportunities.

This successful APP-physician collaboration is driven by a committed group of professionals who are sensitive to the shifting healthcare paradigm. Our APPs and physicians are constantly adapting their practice so that our collaboration is safe, evidence-based, and professionally fulfilling. TH

Yvonne Brown, DNP, MSN, ACNP-C, FNP-C, nurse practitioner, lead advanced practice provider, Division of Hospital Medicine, Emory Healthcare, Emory University Hospital Midtown, Atlanta

Reference

1. Bahouth MN, Esposito-Herr MB. Orientation program for hospital-based nurse practitioners. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2009;20(1):82-90.

Due to many reasons, the healthcare paradigm has shifted, dictating alternative staffing models to manage the burgeoning inpatient census of hospital-based physicians. Herein, we will briefly describe the Emory University Division of Hospital Medicine (EDHM) approach to utilizing advanced practice providers (APPs) in the care of inpatients and summarize key components of the program that improve sustainability for providers.

The EDHM in Atlanta matriculated APPs into its service in 2004. Currently, there are 22 APPs across all Emory HM sites. The largest group is at Emory University Hospital Midtown (EUHM).

At EUHM, the addition of a renal service created concern for increased workload for the physicians. APPs were recruited to bridge the gap in 2011. Initially, the role was ill-defined, but over time, with physician and administrative leadership buy-in and support, the role has evolved. Currently at EUHM, APPs are practicing in other HM services, allowing them to practice near or at the top of their scope of practice. The 12 hospitalist APPs at EUHM practice in four roles: nocturnist, frontline provider in the observation unit, dedicated renal service, and generalist on an overflow team.

Along with the rapid growth of APPs on the service came the need for structured leadership, improved onboarding procedures, competency maintenance, advocacy, and professional development activities. Essentially, we needed to create a career track parallel to that of the physicians without compromising the portion of our scopes of our practice that overlap (i.e., patient care) while supporting our regulatory differences.

The professional development plans incorporated findings from APP exit interviews at the University of Maryland Medical Center highlighting the following retention issues:1