User login

In the rush to curtail abortion, states adopt a jumbled stew of definitions for human life

As life-preserving medical technology advanced in the second half of the 20th century, doctors and families were faced with a thorny decision, one with weighty legal and moral implications: How should we define when life ends? Cardiopulmonary bypass machines could keep the blood pumping and ventilators could maintain breathing long after a patient’s natural ability to perform those vital functions had ceased.

After decades of deliberations involving physicians, bioethicists, attorneys, and theologians, a U.S. presidential commission in 1981 settled on a scientifically derived dividing line between life and death that has endured, more or less, ever since: A person was considered dead when the entire brain – including the brain stem, its most primitive portion – was no longer functioning, even if other vital functions could be maintained indefinitely through artificial life support.

In the decades since, the committee’s criteria have served as a foundation for laws in most states adopting brain death as a standard for legal death.

Now, with the overturning of Roe v. Wade and dozens of states rushing to impose abortion restrictions, At conception, the hint of a heartbeat, a first breath, the ability to survive outside the womb with the help of the latest technology?

That we’ve been able to devise and apply uniform clinical standards for when life ends, but not when it begins, is due largely to the legal and political maelstrom around abortion. And in the 2 months since the U.S. Supreme Court issued its opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, eliminating a longstanding federal right to abortion, state legislators are eagerly bounding into that void, looking to codify into law assorted definitions of life that carry profound repercussions for abortion rights, birth control, and assisted reproduction, as well as civil and criminal law.

“The court said that when life begins is up to whoever is running your state – whether they are wrong or not, or you agree with them or not,” said Mary Ziegler, a law professor at the University of California, Davis, who has written several books on the history of abortion.

Unlike the debate over death, which delved into exquisite medical and scientific detail, the legislative scramble to determine when life’s building blocks reach a threshold that warrants government protection as human life has generally ignored the input of mainstream medical professionals.

Instead, red states across much of the South and portions of the Midwest are adopting language drafted by elected officials that is informed by conservative Christian doctrine, often with little scientific underpinning.

A handful of Republican-led states, including Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, and Oklahoma, have passed laws declaring that life begins at fertilization, a contention that opens the door to a host of pregnancy-related litigation. This includes wrongful death lawsuits brought on behalf of the estate of an embryo by disgruntled ex-partners against physicians and women who end a pregnancy or even miscarry. (One such lawsuit is underway in Arizona. Another reached the Alabama Supreme Court.)

In Kentucky, the law outlawing abortion uses morally explosive terms to define pregnancy as “the human female reproductive condition of having a living unborn human being within her body throughout the entire embryonic and fetal stages of the unborn child from fertilization to full gestation and childbirth.”

Several other states, including Georgia, have adopted measures equating life with the point at which an embryo’s nascent cardiac activity can be detected by an ultrasound, at around 6 weeks of gestation. Many such laws mischaracterize the flickering electrical impulses detectable at that stage as a heartbeat, including in Georgia, whose Department of Revenue recently announced that “any unborn child with a detectable human heartbeat” can be claimed as a dependent.

The Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade that established a constitutional right to abortion did not define a moment when life begins. The opinion, written by Justice Harry Blackmun, observed that the Constitution does not provide a definition of “person,” though it extends protections to those born or naturalized in the United States. The court majority made note of the many disparate views among religions and scientists on when life begins, and concluded it was not up to the states to adopt one theory of life.

Instead, Roe created a framework intended to balance a pregnant woman’s right to make decisions about her body with a public interest in protecting potential human life. That decision and a key ruling that followed generally recognized a woman’s right to abortion up to the point medical professionals judge a fetus viable to survive outside the uterus, at about 24 weeks of gestation.

In decisively overturning Roe in June, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority drew on legal arguments that have shaped another contentious end-of-life issue. The legal standard employed in Dobbs – that there is no right to abortion in the federal Constitution and that states can decide on their own – is the same rationale used in 1997 when the Supreme Court said terminally ill people did not have a constitutional right to medically assisted death. That decision, Washington v. Glucksberg, is mentioned 15 times in the majority opinion for Dobbs and a concurrence by Justice Clarence Thomas.

Often, the same groups that have led the fight to outlaw abortion have also challenged medical aid-in-dying laws. Even after Dobbs, so-called right-to-die laws remain far less common than those codifying state abortion rights. Ten states allow physicians to prescribe lethal doses of medicine for terminally ill patients. Doctors are still prohibited from administering the drugs.

James Bopp, general counsel for the National Right to Life Committee who has been central to the efforts to outlaw abortion, said that both abortion and medically assisted death, which he refers to as physician-assisted suicide, endanger society.

“Every individual human life has inherent value and is sacred,” said Mr. Bopp. “The government has the duty to protect that life.”

Both issues raise profound societal questions: Can the government keep a patient on life support against his wishes, or force a woman to give birth? Can states bar their own residents from going to other states to end a pregnancy, or prohibit out-of-state patients from coming in to seek medically assisted death? And who gets to decide, particularly if the answer imposes a singular religious viewpoint?

Just as there are legal implications that flow from determining a person’s death, from organ donation to inheritance, the implied rights held by a legally recognized zygote are potentially vast. Will death certificates be issued for every lost pregnancy? Will miscarriages be investigated? When will Social Security numbers be issued? How will census counts be tallied and congressional districts drawn?

Medical professionals and bioethicists caution that both the beginning and end of life are complicated biological processes that are not defined by a single identifiable moment – and are ill suited to the political arena.

“Unfortunately, biological occurrences are not events, they are processes,” said David Magnus, PhD, director of the Stanford (Calif.) Center for Biomedical Ethics.

Moreover, asking doctors “What is life?” or “What is death?” may miss the point, said Dr. Magnus: “Medicine can answer the question ‘When does a biological organism cease to exist?’ But they can’t answer the question ‘When does a person begin or end?’ because those are metaphysical issues.”

Ben Sarbey, a doctoral candidate in the department of philosophy at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who studies medical ethics, echoed that perspective, recounting the Paradox of the Heap, a thought experiment that involves placing grains of sand one on top of the next. The philosophical quandary is this: At what point do those grains of sand become something more – a heap?

“We’re going to have a rough time placing a dividing line that this counts as a person and this does not count as a person,” he said. “Many things count as life – a sperm counts as life, a person in a persistent vegetative state counts as life – but does that constitute a person that we should be protecting?”

Even as debate over the court’s abortion decision percolates, the 1981 federal statute that grew out of the presidential committee’s findings, the Uniform Determination of Death Act, is also under review. In 2022, the Uniform Law Commission, a nonpartisan group of legal experts that drafts laws intended for adoption in multiple states, has taken up the work to revisit the definition of death.

The group will consider sharpening the medical standards for brain death in light of advances in the understanding of brain function. And they will look to address lingering questions raised in recent years as families and religious groups have waged heated legal battles over terminating artificial life support for patients with no brain wave activity.

Mr. Bopp, with the National Right to Life Committee, is among those serving on advisory panels for the effort, along with an array of doctors, philosophers, and medical ethicists. The concept of “personhood” that infuses the antiabortion movement’s broader push for fetal rights is expected to be an underlying topic, albeit in mirror image: When does a life form cease being a person?

Dr. Magnus, who is also serving on an advisory panel, has no doubt the commission will reach a consensus, a sober resolution rooted in science. What’s less clear, he said, is whether in today’s political environment that updated definition will hold the same sway, an enduring legal standard embraced across states.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

As life-preserving medical technology advanced in the second half of the 20th century, doctors and families were faced with a thorny decision, one with weighty legal and moral implications: How should we define when life ends? Cardiopulmonary bypass machines could keep the blood pumping and ventilators could maintain breathing long after a patient’s natural ability to perform those vital functions had ceased.

After decades of deliberations involving physicians, bioethicists, attorneys, and theologians, a U.S. presidential commission in 1981 settled on a scientifically derived dividing line between life and death that has endured, more or less, ever since: A person was considered dead when the entire brain – including the brain stem, its most primitive portion – was no longer functioning, even if other vital functions could be maintained indefinitely through artificial life support.

In the decades since, the committee’s criteria have served as a foundation for laws in most states adopting brain death as a standard for legal death.

Now, with the overturning of Roe v. Wade and dozens of states rushing to impose abortion restrictions, At conception, the hint of a heartbeat, a first breath, the ability to survive outside the womb with the help of the latest technology?

That we’ve been able to devise and apply uniform clinical standards for when life ends, but not when it begins, is due largely to the legal and political maelstrom around abortion. And in the 2 months since the U.S. Supreme Court issued its opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, eliminating a longstanding federal right to abortion, state legislators are eagerly bounding into that void, looking to codify into law assorted definitions of life that carry profound repercussions for abortion rights, birth control, and assisted reproduction, as well as civil and criminal law.

“The court said that when life begins is up to whoever is running your state – whether they are wrong or not, or you agree with them or not,” said Mary Ziegler, a law professor at the University of California, Davis, who has written several books on the history of abortion.

Unlike the debate over death, which delved into exquisite medical and scientific detail, the legislative scramble to determine when life’s building blocks reach a threshold that warrants government protection as human life has generally ignored the input of mainstream medical professionals.

Instead, red states across much of the South and portions of the Midwest are adopting language drafted by elected officials that is informed by conservative Christian doctrine, often with little scientific underpinning.

A handful of Republican-led states, including Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, and Oklahoma, have passed laws declaring that life begins at fertilization, a contention that opens the door to a host of pregnancy-related litigation. This includes wrongful death lawsuits brought on behalf of the estate of an embryo by disgruntled ex-partners against physicians and women who end a pregnancy or even miscarry. (One such lawsuit is underway in Arizona. Another reached the Alabama Supreme Court.)

In Kentucky, the law outlawing abortion uses morally explosive terms to define pregnancy as “the human female reproductive condition of having a living unborn human being within her body throughout the entire embryonic and fetal stages of the unborn child from fertilization to full gestation and childbirth.”

Several other states, including Georgia, have adopted measures equating life with the point at which an embryo’s nascent cardiac activity can be detected by an ultrasound, at around 6 weeks of gestation. Many such laws mischaracterize the flickering electrical impulses detectable at that stage as a heartbeat, including in Georgia, whose Department of Revenue recently announced that “any unborn child with a detectable human heartbeat” can be claimed as a dependent.

The Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade that established a constitutional right to abortion did not define a moment when life begins. The opinion, written by Justice Harry Blackmun, observed that the Constitution does not provide a definition of “person,” though it extends protections to those born or naturalized in the United States. The court majority made note of the many disparate views among religions and scientists on when life begins, and concluded it was not up to the states to adopt one theory of life.

Instead, Roe created a framework intended to balance a pregnant woman’s right to make decisions about her body with a public interest in protecting potential human life. That decision and a key ruling that followed generally recognized a woman’s right to abortion up to the point medical professionals judge a fetus viable to survive outside the uterus, at about 24 weeks of gestation.

In decisively overturning Roe in June, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority drew on legal arguments that have shaped another contentious end-of-life issue. The legal standard employed in Dobbs – that there is no right to abortion in the federal Constitution and that states can decide on their own – is the same rationale used in 1997 when the Supreme Court said terminally ill people did not have a constitutional right to medically assisted death. That decision, Washington v. Glucksberg, is mentioned 15 times in the majority opinion for Dobbs and a concurrence by Justice Clarence Thomas.

Often, the same groups that have led the fight to outlaw abortion have also challenged medical aid-in-dying laws. Even after Dobbs, so-called right-to-die laws remain far less common than those codifying state abortion rights. Ten states allow physicians to prescribe lethal doses of medicine for terminally ill patients. Doctors are still prohibited from administering the drugs.

James Bopp, general counsel for the National Right to Life Committee who has been central to the efforts to outlaw abortion, said that both abortion and medically assisted death, which he refers to as physician-assisted suicide, endanger society.

“Every individual human life has inherent value and is sacred,” said Mr. Bopp. “The government has the duty to protect that life.”

Both issues raise profound societal questions: Can the government keep a patient on life support against his wishes, or force a woman to give birth? Can states bar their own residents from going to other states to end a pregnancy, or prohibit out-of-state patients from coming in to seek medically assisted death? And who gets to decide, particularly if the answer imposes a singular religious viewpoint?

Just as there are legal implications that flow from determining a person’s death, from organ donation to inheritance, the implied rights held by a legally recognized zygote are potentially vast. Will death certificates be issued for every lost pregnancy? Will miscarriages be investigated? When will Social Security numbers be issued? How will census counts be tallied and congressional districts drawn?

Medical professionals and bioethicists caution that both the beginning and end of life are complicated biological processes that are not defined by a single identifiable moment – and are ill suited to the political arena.

“Unfortunately, biological occurrences are not events, they are processes,” said David Magnus, PhD, director of the Stanford (Calif.) Center for Biomedical Ethics.

Moreover, asking doctors “What is life?” or “What is death?” may miss the point, said Dr. Magnus: “Medicine can answer the question ‘When does a biological organism cease to exist?’ But they can’t answer the question ‘When does a person begin or end?’ because those are metaphysical issues.”

Ben Sarbey, a doctoral candidate in the department of philosophy at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who studies medical ethics, echoed that perspective, recounting the Paradox of the Heap, a thought experiment that involves placing grains of sand one on top of the next. The philosophical quandary is this: At what point do those grains of sand become something more – a heap?

“We’re going to have a rough time placing a dividing line that this counts as a person and this does not count as a person,” he said. “Many things count as life – a sperm counts as life, a person in a persistent vegetative state counts as life – but does that constitute a person that we should be protecting?”

Even as debate over the court’s abortion decision percolates, the 1981 federal statute that grew out of the presidential committee’s findings, the Uniform Determination of Death Act, is also under review. In 2022, the Uniform Law Commission, a nonpartisan group of legal experts that drafts laws intended for adoption in multiple states, has taken up the work to revisit the definition of death.

The group will consider sharpening the medical standards for brain death in light of advances in the understanding of brain function. And they will look to address lingering questions raised in recent years as families and religious groups have waged heated legal battles over terminating artificial life support for patients with no brain wave activity.

Mr. Bopp, with the National Right to Life Committee, is among those serving on advisory panels for the effort, along with an array of doctors, philosophers, and medical ethicists. The concept of “personhood” that infuses the antiabortion movement’s broader push for fetal rights is expected to be an underlying topic, albeit in mirror image: When does a life form cease being a person?

Dr. Magnus, who is also serving on an advisory panel, has no doubt the commission will reach a consensus, a sober resolution rooted in science. What’s less clear, he said, is whether in today’s political environment that updated definition will hold the same sway, an enduring legal standard embraced across states.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

As life-preserving medical technology advanced in the second half of the 20th century, doctors and families were faced with a thorny decision, one with weighty legal and moral implications: How should we define when life ends? Cardiopulmonary bypass machines could keep the blood pumping and ventilators could maintain breathing long after a patient’s natural ability to perform those vital functions had ceased.

After decades of deliberations involving physicians, bioethicists, attorneys, and theologians, a U.S. presidential commission in 1981 settled on a scientifically derived dividing line between life and death that has endured, more or less, ever since: A person was considered dead when the entire brain – including the brain stem, its most primitive portion – was no longer functioning, even if other vital functions could be maintained indefinitely through artificial life support.

In the decades since, the committee’s criteria have served as a foundation for laws in most states adopting brain death as a standard for legal death.

Now, with the overturning of Roe v. Wade and dozens of states rushing to impose abortion restrictions, At conception, the hint of a heartbeat, a first breath, the ability to survive outside the womb with the help of the latest technology?

That we’ve been able to devise and apply uniform clinical standards for when life ends, but not when it begins, is due largely to the legal and political maelstrom around abortion. And in the 2 months since the U.S. Supreme Court issued its opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, eliminating a longstanding federal right to abortion, state legislators are eagerly bounding into that void, looking to codify into law assorted definitions of life that carry profound repercussions for abortion rights, birth control, and assisted reproduction, as well as civil and criminal law.

“The court said that when life begins is up to whoever is running your state – whether they are wrong or not, or you agree with them or not,” said Mary Ziegler, a law professor at the University of California, Davis, who has written several books on the history of abortion.

Unlike the debate over death, which delved into exquisite medical and scientific detail, the legislative scramble to determine when life’s building blocks reach a threshold that warrants government protection as human life has generally ignored the input of mainstream medical professionals.

Instead, red states across much of the South and portions of the Midwest are adopting language drafted by elected officials that is informed by conservative Christian doctrine, often with little scientific underpinning.

A handful of Republican-led states, including Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, and Oklahoma, have passed laws declaring that life begins at fertilization, a contention that opens the door to a host of pregnancy-related litigation. This includes wrongful death lawsuits brought on behalf of the estate of an embryo by disgruntled ex-partners against physicians and women who end a pregnancy or even miscarry. (One such lawsuit is underway in Arizona. Another reached the Alabama Supreme Court.)

In Kentucky, the law outlawing abortion uses morally explosive terms to define pregnancy as “the human female reproductive condition of having a living unborn human being within her body throughout the entire embryonic and fetal stages of the unborn child from fertilization to full gestation and childbirth.”

Several other states, including Georgia, have adopted measures equating life with the point at which an embryo’s nascent cardiac activity can be detected by an ultrasound, at around 6 weeks of gestation. Many such laws mischaracterize the flickering electrical impulses detectable at that stage as a heartbeat, including in Georgia, whose Department of Revenue recently announced that “any unborn child with a detectable human heartbeat” can be claimed as a dependent.

The Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade that established a constitutional right to abortion did not define a moment when life begins. The opinion, written by Justice Harry Blackmun, observed that the Constitution does not provide a definition of “person,” though it extends protections to those born or naturalized in the United States. The court majority made note of the many disparate views among religions and scientists on when life begins, and concluded it was not up to the states to adopt one theory of life.

Instead, Roe created a framework intended to balance a pregnant woman’s right to make decisions about her body with a public interest in protecting potential human life. That decision and a key ruling that followed generally recognized a woman’s right to abortion up to the point medical professionals judge a fetus viable to survive outside the uterus, at about 24 weeks of gestation.

In decisively overturning Roe in June, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority drew on legal arguments that have shaped another contentious end-of-life issue. The legal standard employed in Dobbs – that there is no right to abortion in the federal Constitution and that states can decide on their own – is the same rationale used in 1997 when the Supreme Court said terminally ill people did not have a constitutional right to medically assisted death. That decision, Washington v. Glucksberg, is mentioned 15 times in the majority opinion for Dobbs and a concurrence by Justice Clarence Thomas.

Often, the same groups that have led the fight to outlaw abortion have also challenged medical aid-in-dying laws. Even after Dobbs, so-called right-to-die laws remain far less common than those codifying state abortion rights. Ten states allow physicians to prescribe lethal doses of medicine for terminally ill patients. Doctors are still prohibited from administering the drugs.

James Bopp, general counsel for the National Right to Life Committee who has been central to the efforts to outlaw abortion, said that both abortion and medically assisted death, which he refers to as physician-assisted suicide, endanger society.

“Every individual human life has inherent value and is sacred,” said Mr. Bopp. “The government has the duty to protect that life.”

Both issues raise profound societal questions: Can the government keep a patient on life support against his wishes, or force a woman to give birth? Can states bar their own residents from going to other states to end a pregnancy, or prohibit out-of-state patients from coming in to seek medically assisted death? And who gets to decide, particularly if the answer imposes a singular religious viewpoint?

Just as there are legal implications that flow from determining a person’s death, from organ donation to inheritance, the implied rights held by a legally recognized zygote are potentially vast. Will death certificates be issued for every lost pregnancy? Will miscarriages be investigated? When will Social Security numbers be issued? How will census counts be tallied and congressional districts drawn?

Medical professionals and bioethicists caution that both the beginning and end of life are complicated biological processes that are not defined by a single identifiable moment – and are ill suited to the political arena.

“Unfortunately, biological occurrences are not events, they are processes,” said David Magnus, PhD, director of the Stanford (Calif.) Center for Biomedical Ethics.

Moreover, asking doctors “What is life?” or “What is death?” may miss the point, said Dr. Magnus: “Medicine can answer the question ‘When does a biological organism cease to exist?’ But they can’t answer the question ‘When does a person begin or end?’ because those are metaphysical issues.”

Ben Sarbey, a doctoral candidate in the department of philosophy at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who studies medical ethics, echoed that perspective, recounting the Paradox of the Heap, a thought experiment that involves placing grains of sand one on top of the next. The philosophical quandary is this: At what point do those grains of sand become something more – a heap?

“We’re going to have a rough time placing a dividing line that this counts as a person and this does not count as a person,” he said. “Many things count as life – a sperm counts as life, a person in a persistent vegetative state counts as life – but does that constitute a person that we should be protecting?”

Even as debate over the court’s abortion decision percolates, the 1981 federal statute that grew out of the presidential committee’s findings, the Uniform Determination of Death Act, is also under review. In 2022, the Uniform Law Commission, a nonpartisan group of legal experts that drafts laws intended for adoption in multiple states, has taken up the work to revisit the definition of death.

The group will consider sharpening the medical standards for brain death in light of advances in the understanding of brain function. And they will look to address lingering questions raised in recent years as families and religious groups have waged heated legal battles over terminating artificial life support for patients with no brain wave activity.

Mr. Bopp, with the National Right to Life Committee, is among those serving on advisory panels for the effort, along with an array of doctors, philosophers, and medical ethicists. The concept of “personhood” that infuses the antiabortion movement’s broader push for fetal rights is expected to be an underlying topic, albeit in mirror image: When does a life form cease being a person?

Dr. Magnus, who is also serving on an advisory panel, has no doubt the commission will reach a consensus, a sober resolution rooted in science. What’s less clear, he said, is whether in today’s political environment that updated definition will hold the same sway, an enduring legal standard embraced across states.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

New ovulatory disorder classifications from FIGO replace 50-year-old system

The first major revision in the systematic description of ovulatory disorders in nearly 50 years has been proposed by a consensus of experts organized by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

“The FIGO HyPO-P system for the classification of ovulatory disorders is submitted for consideration as a worldwide standard,” according to the writing committee, who published their methodology and their proposed applications in the International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The classification system was created to replace the much-modified World Health Organization system first described in 1973. Since that time, many modifications have been proposed to accommodate advances in imaging and new information about underlying pathologies, but there has been no subsequent authoritative reference with these modifications or any other newer organizing system.

The new consensus was developed under the aegis of FIGO, but the development group consisted of representatives from national organizations and the major subspecialty societies. Recognized experts in ovulatory disorders and representatives from lay advocacy organizations also participated.

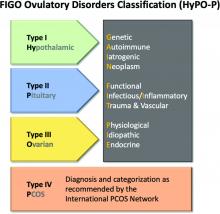

The HyPO-P system is based largely on anatomy. The acronym refers to ovulatory disorders related to the hypothalamus (type I), the pituitary (type II), and the ovary (type III).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common ovulatory disorders, was given a separate category (type IV) because of its complexity as well as the fact that PCOS is a heterogeneous systemic disorder with manifestations not limited to an impact on ovarian function.

As the first level of classification, three of the four primary categories (I-III) focus attention on the dominant anatomic source of the change in ovulatory function. The original WHO classification system identified as many as seven major groups, but they were based primarily on assays for gonadotropins and estradiol.

The new system “provides a different structure for determining the diagnosis. Blood tests are not a necessary first step,” explained Malcolm G. Munro, MD, clinical professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Munro was the first author of the publication.

The classification system “is not as focused on the specific steps for investigation of ovulatory dysfunction as much as it explains how to structure an investigation of the girl or woman with an ovulatory disorder and then how to characterize the underlying cause,” Dr. Munro said in an interview. “It is designed to allow everyone, whether clinicians, researchers, or patients, to speak the same language.”

New system employs four categories

The four primary categories provide just the first level of classification. The next step is encapsulated in the GAIN-FIT-PIE acronym, which frames the presumed or documented categories of etiologies for the primary categories. GAIN stands for genetic, autoimmune, iatrogenic, or neoplasm etiologies. FIT stands for functional, infectious/inflammatory, or trauma and vascular etiologies. PIE stands for physiological, idiopathic, and endocrine etiologies.

By this methodology, a patient with irregular menses, galactorrhea, and elevated prolactin and an MRI showing a pituitary tumor would be identified a type 2-N, signifying pituitary (type 2) involvement with a neoplasm (N).

A third level of classification permits specific diagnostic entities to be named, allowing the patient in the example above to receive a diagnosis of a prolactin-secreting adenoma.

Not all etiologies can be identified with current diagnostic studies, even assuming clinicians have access to the resources, such as advanced imaging, that will increase diagnostic yield. As a result, the authors acknowledged that the classification system will be “aspirational” in at least some patients, but the structure of this system is expected to lead to greater precision in understanding the causes and defining features of ovulatory disorders, which, in turn, might facilitate new research initiatives.

In the published report, diagnostic protocols based on symptoms were described as being “beyond the spectrum” of this initial description. Rather, Dr. Munro explained that the most important contribution of this new classification system are standardization and communication. The system will be amenable for educating trainees and patients, for communicating between clinicians, and as a framework for research where investigators focus on more homogeneous populations of patients.

“There are many causes of ovulatory disorders that are not related to ovarian function. This is one message. Another is that ovulatory disorders are not binary. They occur on a spectrum. These range from transient instances of delayed or failed ovulation to chronic anovulation,” he said.

The new system is “ a welcome update,” according to Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, both in Orlando.

Dr. Trolice pointed to the clinical value of placing PCOS in a separate category. He noted that it affects 8%-13% of women, making it the most common single cause of ovulatory dysfunction.

“Another area that required clarification from prior WHO classifications was hyperprolactinemia, which is now placed in the type II category,” Dr. Trolice said in an interview.

Better terminology can help address a complex set of disorders with multiple causes and variable manifestations.

“In the evaluation of ovulation dysfunction, it is important to remember that regular menstrual intervals do not ensure ovulation,” Dr. Trolice pointed out. Even though a serum progesterone level of higher than 3 ng/mL is one of the simplest laboratory markers for ovulation, this level, he noted, “can vary through the luteal phase and even throughout the day.”

The proposed classification system, while providing a framework for describing ovulatory disorders, is designed to be adaptable, permitting advances in the understanding of the causes of ovulatory dysfunction, in the diagnosis of the causes, and in the treatments to be incorporated.

“No system should be considered permanent,” according to Dr. Munro and his coauthors. “Review and careful modification and revision should be carried out regularly.”

Dr. Munro reports financial relationships with AbbVie, American Regent, Daiichi Sankyo, Hologic, Myovant, and Pharmacosmos. Dr. Trolice reports no potential conflicts of interest.

The first major revision in the systematic description of ovulatory disorders in nearly 50 years has been proposed by a consensus of experts organized by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

“The FIGO HyPO-P system for the classification of ovulatory disorders is submitted for consideration as a worldwide standard,” according to the writing committee, who published their methodology and their proposed applications in the International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The classification system was created to replace the much-modified World Health Organization system first described in 1973. Since that time, many modifications have been proposed to accommodate advances in imaging and new information about underlying pathologies, but there has been no subsequent authoritative reference with these modifications or any other newer organizing system.

The new consensus was developed under the aegis of FIGO, but the development group consisted of representatives from national organizations and the major subspecialty societies. Recognized experts in ovulatory disorders and representatives from lay advocacy organizations also participated.

The HyPO-P system is based largely on anatomy. The acronym refers to ovulatory disorders related to the hypothalamus (type I), the pituitary (type II), and the ovary (type III).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common ovulatory disorders, was given a separate category (type IV) because of its complexity as well as the fact that PCOS is a heterogeneous systemic disorder with manifestations not limited to an impact on ovarian function.

As the first level of classification, three of the four primary categories (I-III) focus attention on the dominant anatomic source of the change in ovulatory function. The original WHO classification system identified as many as seven major groups, but they were based primarily on assays for gonadotropins and estradiol.

The new system “provides a different structure for determining the diagnosis. Blood tests are not a necessary first step,” explained Malcolm G. Munro, MD, clinical professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Munro was the first author of the publication.

The classification system “is not as focused on the specific steps for investigation of ovulatory dysfunction as much as it explains how to structure an investigation of the girl or woman with an ovulatory disorder and then how to characterize the underlying cause,” Dr. Munro said in an interview. “It is designed to allow everyone, whether clinicians, researchers, or patients, to speak the same language.”

New system employs four categories

The four primary categories provide just the first level of classification. The next step is encapsulated in the GAIN-FIT-PIE acronym, which frames the presumed or documented categories of etiologies for the primary categories. GAIN stands for genetic, autoimmune, iatrogenic, or neoplasm etiologies. FIT stands for functional, infectious/inflammatory, or trauma and vascular etiologies. PIE stands for physiological, idiopathic, and endocrine etiologies.

By this methodology, a patient with irregular menses, galactorrhea, and elevated prolactin and an MRI showing a pituitary tumor would be identified a type 2-N, signifying pituitary (type 2) involvement with a neoplasm (N).

A third level of classification permits specific diagnostic entities to be named, allowing the patient in the example above to receive a diagnosis of a prolactin-secreting adenoma.

Not all etiologies can be identified with current diagnostic studies, even assuming clinicians have access to the resources, such as advanced imaging, that will increase diagnostic yield. As a result, the authors acknowledged that the classification system will be “aspirational” in at least some patients, but the structure of this system is expected to lead to greater precision in understanding the causes and defining features of ovulatory disorders, which, in turn, might facilitate new research initiatives.

In the published report, diagnostic protocols based on symptoms were described as being “beyond the spectrum” of this initial description. Rather, Dr. Munro explained that the most important contribution of this new classification system are standardization and communication. The system will be amenable for educating trainees and patients, for communicating between clinicians, and as a framework for research where investigators focus on more homogeneous populations of patients.

“There are many causes of ovulatory disorders that are not related to ovarian function. This is one message. Another is that ovulatory disorders are not binary. They occur on a spectrum. These range from transient instances of delayed or failed ovulation to chronic anovulation,” he said.

The new system is “ a welcome update,” according to Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, both in Orlando.

Dr. Trolice pointed to the clinical value of placing PCOS in a separate category. He noted that it affects 8%-13% of women, making it the most common single cause of ovulatory dysfunction.

“Another area that required clarification from prior WHO classifications was hyperprolactinemia, which is now placed in the type II category,” Dr. Trolice said in an interview.

Better terminology can help address a complex set of disorders with multiple causes and variable manifestations.

“In the evaluation of ovulation dysfunction, it is important to remember that regular menstrual intervals do not ensure ovulation,” Dr. Trolice pointed out. Even though a serum progesterone level of higher than 3 ng/mL is one of the simplest laboratory markers for ovulation, this level, he noted, “can vary through the luteal phase and even throughout the day.”

The proposed classification system, while providing a framework for describing ovulatory disorders, is designed to be adaptable, permitting advances in the understanding of the causes of ovulatory dysfunction, in the diagnosis of the causes, and in the treatments to be incorporated.

“No system should be considered permanent,” according to Dr. Munro and his coauthors. “Review and careful modification and revision should be carried out regularly.”

Dr. Munro reports financial relationships with AbbVie, American Regent, Daiichi Sankyo, Hologic, Myovant, and Pharmacosmos. Dr. Trolice reports no potential conflicts of interest.

The first major revision in the systematic description of ovulatory disorders in nearly 50 years has been proposed by a consensus of experts organized by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

“The FIGO HyPO-P system for the classification of ovulatory disorders is submitted for consideration as a worldwide standard,” according to the writing committee, who published their methodology and their proposed applications in the International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The classification system was created to replace the much-modified World Health Organization system first described in 1973. Since that time, many modifications have been proposed to accommodate advances in imaging and new information about underlying pathologies, but there has been no subsequent authoritative reference with these modifications or any other newer organizing system.

The new consensus was developed under the aegis of FIGO, but the development group consisted of representatives from national organizations and the major subspecialty societies. Recognized experts in ovulatory disorders and representatives from lay advocacy organizations also participated.

The HyPO-P system is based largely on anatomy. The acronym refers to ovulatory disorders related to the hypothalamus (type I), the pituitary (type II), and the ovary (type III).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common ovulatory disorders, was given a separate category (type IV) because of its complexity as well as the fact that PCOS is a heterogeneous systemic disorder with manifestations not limited to an impact on ovarian function.

As the first level of classification, three of the four primary categories (I-III) focus attention on the dominant anatomic source of the change in ovulatory function. The original WHO classification system identified as many as seven major groups, but they were based primarily on assays for gonadotropins and estradiol.

The new system “provides a different structure for determining the diagnosis. Blood tests are not a necessary first step,” explained Malcolm G. Munro, MD, clinical professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Munro was the first author of the publication.

The classification system “is not as focused on the specific steps for investigation of ovulatory dysfunction as much as it explains how to structure an investigation of the girl or woman with an ovulatory disorder and then how to characterize the underlying cause,” Dr. Munro said in an interview. “It is designed to allow everyone, whether clinicians, researchers, or patients, to speak the same language.”

New system employs four categories

The four primary categories provide just the first level of classification. The next step is encapsulated in the GAIN-FIT-PIE acronym, which frames the presumed or documented categories of etiologies for the primary categories. GAIN stands for genetic, autoimmune, iatrogenic, or neoplasm etiologies. FIT stands for functional, infectious/inflammatory, or trauma and vascular etiologies. PIE stands for physiological, idiopathic, and endocrine etiologies.

By this methodology, a patient with irregular menses, galactorrhea, and elevated prolactin and an MRI showing a pituitary tumor would be identified a type 2-N, signifying pituitary (type 2) involvement with a neoplasm (N).

A third level of classification permits specific diagnostic entities to be named, allowing the patient in the example above to receive a diagnosis of a prolactin-secreting adenoma.

Not all etiologies can be identified with current diagnostic studies, even assuming clinicians have access to the resources, such as advanced imaging, that will increase diagnostic yield. As a result, the authors acknowledged that the classification system will be “aspirational” in at least some patients, but the structure of this system is expected to lead to greater precision in understanding the causes and defining features of ovulatory disorders, which, in turn, might facilitate new research initiatives.

In the published report, diagnostic protocols based on symptoms were described as being “beyond the spectrum” of this initial description. Rather, Dr. Munro explained that the most important contribution of this new classification system are standardization and communication. The system will be amenable for educating trainees and patients, for communicating between clinicians, and as a framework for research where investigators focus on more homogeneous populations of patients.

“There are many causes of ovulatory disorders that are not related to ovarian function. This is one message. Another is that ovulatory disorders are not binary. They occur on a spectrum. These range from transient instances of delayed or failed ovulation to chronic anovulation,” he said.

The new system is “ a welcome update,” according to Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, both in Orlando.

Dr. Trolice pointed to the clinical value of placing PCOS in a separate category. He noted that it affects 8%-13% of women, making it the most common single cause of ovulatory dysfunction.

“Another area that required clarification from prior WHO classifications was hyperprolactinemia, which is now placed in the type II category,” Dr. Trolice said in an interview.

Better terminology can help address a complex set of disorders with multiple causes and variable manifestations.

“In the evaluation of ovulation dysfunction, it is important to remember that regular menstrual intervals do not ensure ovulation,” Dr. Trolice pointed out. Even though a serum progesterone level of higher than 3 ng/mL is one of the simplest laboratory markers for ovulation, this level, he noted, “can vary through the luteal phase and even throughout the day.”

The proposed classification system, while providing a framework for describing ovulatory disorders, is designed to be adaptable, permitting advances in the understanding of the causes of ovulatory dysfunction, in the diagnosis of the causes, and in the treatments to be incorporated.

“No system should be considered permanent,” according to Dr. Munro and his coauthors. “Review and careful modification and revision should be carried out regularly.”

Dr. Munro reports financial relationships with AbbVie, American Regent, Daiichi Sankyo, Hologic, Myovant, and Pharmacosmos. Dr. Trolice reports no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GYNECOLOGY AND OBSTETRICS

State of the science in PCOS: Emerging neuroendocrine involvement driving research

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) affects an estimated 8%-13% of women, and yet “it has been quite a black box for many years,” as Margo Hudson, MD, an assistant professor of endocrinology, diabetes, and hypertension at Harvard Medical School, Boston, puts it. That black box encompasses not only uncertainty about the etiology and pathophysiology of the condition but even what constitutes a diagnosis.

Even the international guidelines on PCOS management endorsed by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine – a document developed over 15 months with the input of 37 medical organizations covering 71 countries – notes that PCOS diagnosis is “controversial and assessment and management are inconsistent.” The result, the guidelines note, is that “the needs of women with PCOS are not being adequately met.”

One of the earliest diagnostic criteria, defined in 1990 by the National Institutes of Health, required only hyperandrogenism and irregular menstruation. Then the 2003 Rotterdam Criteria added presence of polycystic ovaries on ultrasound as a third criterion. Then the Androgen Excess Society determined that PCOS required presence of hyperandrogenism with either polycystic ovaries or oligo/amenorrhea anovulation. Yet the Endocrine Society notes that excess androgen levels are seen in 60%-80% of those with PCOS, suggesting it’s not an essential requirement for diagnosis, leaving most to diagnose it in people who have two of the three key criteria. The only real agreement on diagnosis is the need to eliminate other potential diagnoses first, making PCOS always a diagnosis of exclusion.

Further, though PCOS is known as the leading cause of infertility in women, it is more than a reproductive condition, with metabolic and psychological features as well. Then there is the range of comorbidities, none of which occur in all patients with PCOS but all of which occur in a majority and which are themselves interrelated. Insulin resistance is a common feature, occurring in 50%-70% of people with PCOS. Accordingly, metabolic syndrome occurs in at least a third of people with PCOS and type 2 diabetes prevalence is higher in those with PCOS as well.

Obesity occurs in an estimated 80% of women with PCOS in the United States, though it affects only about 50% of women with PCOS outside the United States, and those with PCOS have an increased risk of hypertension. Mood disorders, particularly anxiety and depression but also, to a lesser extent, bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, are more likely in people with PCOS. And given that these comorbidities are all cardiovascular risk factors, it’s unsurprising that recent studies are finding those with PCOS to be at greater risk for cardiometabolic disease and major cardiovascular events.

“The reality is that PCOS is a heterogenous entity. It’s not one thing – it’s a syndrome,” Lubna Pal, MBBS, a professor of ob.gyn. and director of the PCOS Program at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. A whole host of factors are likely playing a role in the causes of PCOS, and those factors interact differently within different people. “We’re looking at things like lipid metabolism, fetal origins, the gut microbiome, genetics, epigenetics, and then dietary and environmental factors,” Nichole Tyson, MD, division chief of pediatric and adolescent gynecology and a clinical associate professor at Stanford (Calif.) Medicine Children’s Health, said in an interview. And most studies have identified associations that may or may not be causal. Take, for example, endocrine disruptors. BPA levels have been shown to be higher in women with PCOS than women without, but that correlation may or may not be related to the etiology of the condition.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

In trying to understand the pathophysiology of the condition, much of the latest research has zeroed in on potential mechanisms in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. “A consistent feature of PCOS is disordered gonadotropin secretion with elevated mean LH [luteinizing hormone], low or low normal FSH [follicle-stimulating hormone], and a persistently rapid frequency of GnRH [gonadotropin-releasing hormone] pulse secretion,” wrote authors of a scientific statement on aspects of PCOS.

“I think the balance is heading more to central neurologic control of the reproductive system and that disturbances there impact the GnRH cells in the hypothalamus, which then go on to give us the findings that we can measure peripherally with the LH-FSH ratio,” Dr. Hudson said in an interview.

The increased LH levels are thought to be a major driver of increased androgen levels. Current thinking suggests that the primary driver of increased LH is GnRH pulsatility, supported not only by human studies but by animal models as well. This leads to the question of what drives GnRH dysregulation. One hypothesis posits that GABA neurons play a role here, given findings that GABA levels in cerebrospinal fluid were higher in women with PCOS than those with normal ovulation.

But the culprit garnering the most attention is kisspeptin, a protein encoded by the KISS1 gene that stimulates GnRH neurons and has been linked to regulation of LH and FSH secretion. Kisspeptin, along with neurokinin B and dynorphin, is part of the triumvirate that comprises KNDy neurons, also recently implicated in menopausal vasomotor symptoms. Multiple systematic reviewsand meta-analyses have found a correlation between higher kisspeptin levels in the blood and higher circulating LH levels, regardless of body mass index. While kisspeptin is expressed in several tissues, including liver, pancreas, gonad, and adipose, it’s neural kisspeptin signaling that appears most likely to play a role in activating GnRH hormones and disrupting normal function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.

But as noted, in at least one systematic review of kisspeptin and PCOS, “findings from animal studies suggest that kisspeptin levels are not increased in all subtypes of PCOS.” And another review found “altered” levels of kisspeptin levels in non-PCOS patients who had obesity, potentially raising questions about any associations between kisspeptin and obesity or insulin resistance.

Remaining chicken-and-egg questions

A hallmark of PCOS has long been, and continues to be, the string of chicken-or-egg questions that plague understanding of it. One of these is how depression and anxiety fit into the etiology of PCOS. Exploring the role of specific neurons that may overstimulate GnRH pulsatility may hold clues to a common underlying mechanism for the involvement of depression and anxiety in patients with PCOS, Dr. Hudson speculated. While previous assumptions often attributed depression and anxiety in PCOS to the symptoms – such as thin scalp hair and increased facial hair, excess weight, acne, and irregular periods – Dr. Hudson pointed out that women can address many of these symptoms with laser hair removal, weight loss, acne treatment, and similar interventions, yet they still have a lot of underlying mental health issues.

It’s also unclear whether metabolic factors so common with PCOS, particularly insulin resistance and obesity, are a result of the condition or are contributors to it. Is insulin resistance contributing to dysregulation in the neurons that interferes with normal functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis? Is abnormal functioning along this axis contributing to insulin resistance? Or neither? Or both? Or does it depend? The authors of one paper wrote that “insulin may play both direct and indirect roles in the pathogenesis of androgen excess in PCOS,” since insulin can “stimulate ovarian androgen production” and “enhance ovarian growth and follicular cyst formation in rats.”

Dr. Pal noted that “obesity itself can evolve into a PCOS-like picture,” raising questions about whether obesity or insulin resistance might be part of the causal pathway to PCOS, or whether either can trigger its development in those genetically predisposed.

“Obesity does appear to exacerbate many aspects of the PCOS phenotype, particularly those risk factors related to metabolic syndrome,” wrote the authors of a scientific statement on aspects of PCOS, but they add that “it is currently debated whether obesity per se can cause PCOS.” While massive weight loss in those with PCOS and obesity has improved multiple reproductive and metabolic issues, it hasn’t resolved all of them, they write.

Dr. Hudson said she expects there’s “some degree of appetite dysregulation and metabolic dysregulation” that contributes, but then there are other women who don’t have much of an appetite or overeat and still struggle with their weight. Evidence has also found insulin resistance in women of normal weight with PCOS. “There may be some kind of metabolic dysregulation that they have at some level, and others are clearly bothered by overeating,” Dr. Hudson said.

Similarly, it’s not clear whether the recent discovery of increased cardiovascular risks in people with PCOS is a result of the comorbidities so common with PCOS, such as obesity, or whether an underlying mechanism links the cardiovascular risk and the dysregulation of hormones. Dr. Pal would argue that, again, it’s probably both, depending on the patient.

Then there is the key feature of hyperandrogenemia. “An outstanding debate is whether the elevated androgens in PCOS women are merely a downstream endocrine response to hyperactive GnRH and LH secretion driving the ovary, or do the elevated androgens themselves act in the brain (or pituitary) during development and/or adulthood to sculpt and maintain the hypersecretion of GnRH and LH?” wrote Eulalia A. Coutinho, PhD, and Alexander S. Kauffman, PhD, in a 2019 review of the brain’s role in PCOS.

These problems may be bidirectional or part of various feedback loops. Sleep apnea is more common in people with PCOS, Dr. Tyson noted, but sleep apnea is also linked to cardiovascular, metabolic, and depression risks, and depression can play a role in obesity, which increases the risk of obstructive sleep apnea. “So you’re in this vicious cycle,” Dr. Tyson said. That’s why she also believes it’s important to change the dialogue and perspective on PCOS, to reduce the stigma attached to it, and work with patients to empower them in treating its symptoms and reducing their risk of comorbidities.

Recent and upcoming changes in treatment

Current treatment of PCOS already changes according to the symptoms posing the greatest problems at each stage of a person’s life, Dr. Hudson said. Younger women tend to be more bothered about the cosmetic effects of PCOS, including hair growth patterns and acne, but as they grow out of adolescence and into their 20s and 30s, infertility becomes a bigger concern for many. Then, as they start approaching menopause, metabolic and cardiovascular issues take the lead, with more of a focus on lipids, diabetes risk, and heart health.

In some ways, management of PCOS hasn’t changed much in the past several decades, except in an increased awareness of the metabolic and cardiovascular risks, which has led to more frequent screening to catch potential conditions earlier in life. What has changed, however, is improvements in the treatments used for symptoms, such as expanded bariatric surgery options and GLP-1 agonists for treating obesity. Other examples include better options for menstrual management, such as new progesterone IUDs, and optimized fertility treatments, Dr. Tyson said.

“I think with more of these large-scale studies about the pathophysiology of PCOS and how it may look in different people and the different outcomes, we may be able to tailor our treatments even further,” Dr. Tyson said. She emphasized the importance of identifying the condition early, particularly in adolescents, even if it’s identifying young people at risk for the condition rather than actually having it yet.

Early identification “gives us this chance to do a lot of preventative care and motivate older teens to have a great lifestyle, work on their diet and exercise, and manage cardiovascular” risk factors, Dr. Tyson said.

“What we do know and recognize is that there’s so many spokes to this PCOS wheel that there really should be a multidisciplinary approach to care,” Dr. Tyson said. “When I think about who would be the real doctors for patients with PCOS, these would be gynecologists, endocrinologists, dermatologists, nutritionists, psychologists, sleep specialists, and primary care at a minimum.”

Dr. Pal worries that the label of PCOS leaves it in the laps of ob.gyns. whereas, “if it was called something else, everybody would be involved in being vigilant and managing those patients.” She frequently reiterated that the label of PCOS is less important than ensuring clinicians treat the symptoms that most bother the patient.

And even if kisspeptin does play a causal role in PCOS for some patients, it’s only a subset of individuals with PCOS who would benefit from therapies developed to target it. Given the complexity of the syndrome and its many manifestations, a “galaxy of pathways” are involved in different potential subtypes of the condition. “You can’t treat PCOS as one entity,” Dr. Pal said.

Still, Dr. Hudson is optimistic that the research into potential neuroendocrine contributions to PCOS will yield therapies that go beyond just managing symptoms.

“There aren’t a lot of treatments available yet, but there may be some on the horizon,” Dr. Hudson said. “We’re still in this very primitive stage in terms of therapeutics, where we’re only addressing specific symptoms, and we haven’t been able to really address the underlying cause because we haven’t understood it as well and because we don’t have therapies that can target it,” Dr. Hudson said. “But once there are therapies developed that will target some of these central mechanisms, I think it will change completely the approach to treating PCOS for patients.”

This story was updated on Sept. 6, 2022.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) affects an estimated 8%-13% of women, and yet “it has been quite a black box for many years,” as Margo Hudson, MD, an assistant professor of endocrinology, diabetes, and hypertension at Harvard Medical School, Boston, puts it. That black box encompasses not only uncertainty about the etiology and pathophysiology of the condition but even what constitutes a diagnosis.

Even the international guidelines on PCOS management endorsed by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine – a document developed over 15 months with the input of 37 medical organizations covering 71 countries – notes that PCOS diagnosis is “controversial and assessment and management are inconsistent.” The result, the guidelines note, is that “the needs of women with PCOS are not being adequately met.”

One of the earliest diagnostic criteria, defined in 1990 by the National Institutes of Health, required only hyperandrogenism and irregular menstruation. Then the 2003 Rotterdam Criteria added presence of polycystic ovaries on ultrasound as a third criterion. Then the Androgen Excess Society determined that PCOS required presence of hyperandrogenism with either polycystic ovaries or oligo/amenorrhea anovulation. Yet the Endocrine Society notes that excess androgen levels are seen in 60%-80% of those with PCOS, suggesting it’s not an essential requirement for diagnosis, leaving most to diagnose it in people who have two of the three key criteria. The only real agreement on diagnosis is the need to eliminate other potential diagnoses first, making PCOS always a diagnosis of exclusion.

Further, though PCOS is known as the leading cause of infertility in women, it is more than a reproductive condition, with metabolic and psychological features as well. Then there is the range of comorbidities, none of which occur in all patients with PCOS but all of which occur in a majority and which are themselves interrelated. Insulin resistance is a common feature, occurring in 50%-70% of people with PCOS. Accordingly, metabolic syndrome occurs in at least a third of people with PCOS and type 2 diabetes prevalence is higher in those with PCOS as well.

Obesity occurs in an estimated 80% of women with PCOS in the United States, though it affects only about 50% of women with PCOS outside the United States, and those with PCOS have an increased risk of hypertension. Mood disorders, particularly anxiety and depression but also, to a lesser extent, bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, are more likely in people with PCOS. And given that these comorbidities are all cardiovascular risk factors, it’s unsurprising that recent studies are finding those with PCOS to be at greater risk for cardiometabolic disease and major cardiovascular events.

“The reality is that PCOS is a heterogenous entity. It’s not one thing – it’s a syndrome,” Lubna Pal, MBBS, a professor of ob.gyn. and director of the PCOS Program at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. A whole host of factors are likely playing a role in the causes of PCOS, and those factors interact differently within different people. “We’re looking at things like lipid metabolism, fetal origins, the gut microbiome, genetics, epigenetics, and then dietary and environmental factors,” Nichole Tyson, MD, division chief of pediatric and adolescent gynecology and a clinical associate professor at Stanford (Calif.) Medicine Children’s Health, said in an interview. And most studies have identified associations that may or may not be causal. Take, for example, endocrine disruptors. BPA levels have been shown to be higher in women with PCOS than women without, but that correlation may or may not be related to the etiology of the condition.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

In trying to understand the pathophysiology of the condition, much of the latest research has zeroed in on potential mechanisms in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. “A consistent feature of PCOS is disordered gonadotropin secretion with elevated mean LH [luteinizing hormone], low or low normal FSH [follicle-stimulating hormone], and a persistently rapid frequency of GnRH [gonadotropin-releasing hormone] pulse secretion,” wrote authors of a scientific statement on aspects of PCOS.

“I think the balance is heading more to central neurologic control of the reproductive system and that disturbances there impact the GnRH cells in the hypothalamus, which then go on to give us the findings that we can measure peripherally with the LH-FSH ratio,” Dr. Hudson said in an interview.

The increased LH levels are thought to be a major driver of increased androgen levels. Current thinking suggests that the primary driver of increased LH is GnRH pulsatility, supported not only by human studies but by animal models as well. This leads to the question of what drives GnRH dysregulation. One hypothesis posits that GABA neurons play a role here, given findings that GABA levels in cerebrospinal fluid were higher in women with PCOS than those with normal ovulation.

But the culprit garnering the most attention is kisspeptin, a protein encoded by the KISS1 gene that stimulates GnRH neurons and has been linked to regulation of LH and FSH secretion. Kisspeptin, along with neurokinin B and dynorphin, is part of the triumvirate that comprises KNDy neurons, also recently implicated in menopausal vasomotor symptoms. Multiple systematic reviewsand meta-analyses have found a correlation between higher kisspeptin levels in the blood and higher circulating LH levels, regardless of body mass index. While kisspeptin is expressed in several tissues, including liver, pancreas, gonad, and adipose, it’s neural kisspeptin signaling that appears most likely to play a role in activating GnRH hormones and disrupting normal function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.

But as noted, in at least one systematic review of kisspeptin and PCOS, “findings from animal studies suggest that kisspeptin levels are not increased in all subtypes of PCOS.” And another review found “altered” levels of kisspeptin levels in non-PCOS patients who had obesity, potentially raising questions about any associations between kisspeptin and obesity or insulin resistance.

Remaining chicken-and-egg questions

A hallmark of PCOS has long been, and continues to be, the string of chicken-or-egg questions that plague understanding of it. One of these is how depression and anxiety fit into the etiology of PCOS. Exploring the role of specific neurons that may overstimulate GnRH pulsatility may hold clues to a common underlying mechanism for the involvement of depression and anxiety in patients with PCOS, Dr. Hudson speculated. While previous assumptions often attributed depression and anxiety in PCOS to the symptoms – such as thin scalp hair and increased facial hair, excess weight, acne, and irregular periods – Dr. Hudson pointed out that women can address many of these symptoms with laser hair removal, weight loss, acne treatment, and similar interventions, yet they still have a lot of underlying mental health issues.

It’s also unclear whether metabolic factors so common with PCOS, particularly insulin resistance and obesity, are a result of the condition or are contributors to it. Is insulin resistance contributing to dysregulation in the neurons that interferes with normal functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis? Is abnormal functioning along this axis contributing to insulin resistance? Or neither? Or both? Or does it depend? The authors of one paper wrote that “insulin may play both direct and indirect roles in the pathogenesis of androgen excess in PCOS,” since insulin can “stimulate ovarian androgen production” and “enhance ovarian growth and follicular cyst formation in rats.”

Dr. Pal noted that “obesity itself can evolve into a PCOS-like picture,” raising questions about whether obesity or insulin resistance might be part of the causal pathway to PCOS, or whether either can trigger its development in those genetically predisposed.

“Obesity does appear to exacerbate many aspects of the PCOS phenotype, particularly those risk factors related to metabolic syndrome,” wrote the authors of a scientific statement on aspects of PCOS, but they add that “it is currently debated whether obesity per se can cause PCOS.” While massive weight loss in those with PCOS and obesity has improved multiple reproductive and metabolic issues, it hasn’t resolved all of them, they write.

Dr. Hudson said she expects there’s “some degree of appetite dysregulation and metabolic dysregulation” that contributes, but then there are other women who don’t have much of an appetite or overeat and still struggle with their weight. Evidence has also found insulin resistance in women of normal weight with PCOS. “There may be some kind of metabolic dysregulation that they have at some level, and others are clearly bothered by overeating,” Dr. Hudson said.

Similarly, it’s not clear whether the recent discovery of increased cardiovascular risks in people with PCOS is a result of the comorbidities so common with PCOS, such as obesity, or whether an underlying mechanism links the cardiovascular risk and the dysregulation of hormones. Dr. Pal would argue that, again, it’s probably both, depending on the patient.

Then there is the key feature of hyperandrogenemia. “An outstanding debate is whether the elevated androgens in PCOS women are merely a downstream endocrine response to hyperactive GnRH and LH secretion driving the ovary, or do the elevated androgens themselves act in the brain (or pituitary) during development and/or adulthood to sculpt and maintain the hypersecretion of GnRH and LH?” wrote Eulalia A. Coutinho, PhD, and Alexander S. Kauffman, PhD, in a 2019 review of the brain’s role in PCOS.

These problems may be bidirectional or part of various feedback loops. Sleep apnea is more common in people with PCOS, Dr. Tyson noted, but sleep apnea is also linked to cardiovascular, metabolic, and depression risks, and depression can play a role in obesity, which increases the risk of obstructive sleep apnea. “So you’re in this vicious cycle,” Dr. Tyson said. That’s why she also believes it’s important to change the dialogue and perspective on PCOS, to reduce the stigma attached to it, and work with patients to empower them in treating its symptoms and reducing their risk of comorbidities.

Recent and upcoming changes in treatment

Current treatment of PCOS already changes according to the symptoms posing the greatest problems at each stage of a person’s life, Dr. Hudson said. Younger women tend to be more bothered about the cosmetic effects of PCOS, including hair growth patterns and acne, but as they grow out of adolescence and into their 20s and 30s, infertility becomes a bigger concern for many. Then, as they start approaching menopause, metabolic and cardiovascular issues take the lead, with more of a focus on lipids, diabetes risk, and heart health.

In some ways, management of PCOS hasn’t changed much in the past several decades, except in an increased awareness of the metabolic and cardiovascular risks, which has led to more frequent screening to catch potential conditions earlier in life. What has changed, however, is improvements in the treatments used for symptoms, such as expanded bariatric surgery options and GLP-1 agonists for treating obesity. Other examples include better options for menstrual management, such as new progesterone IUDs, and optimized fertility treatments, Dr. Tyson said.

“I think with more of these large-scale studies about the pathophysiology of PCOS and how it may look in different people and the different outcomes, we may be able to tailor our treatments even further,” Dr. Tyson said. She emphasized the importance of identifying the condition early, particularly in adolescents, even if it’s identifying young people at risk for the condition rather than actually having it yet.

Early identification “gives us this chance to do a lot of preventative care and motivate older teens to have a great lifestyle, work on their diet and exercise, and manage cardiovascular” risk factors, Dr. Tyson said.

“What we do know and recognize is that there’s so many spokes to this PCOS wheel that there really should be a multidisciplinary approach to care,” Dr. Tyson said. “When I think about who would be the real doctors for patients with PCOS, these would be gynecologists, endocrinologists, dermatologists, nutritionists, psychologists, sleep specialists, and primary care at a minimum.”

Dr. Pal worries that the label of PCOS leaves it in the laps of ob.gyns. whereas, “if it was called something else, everybody would be involved in being vigilant and managing those patients.” She frequently reiterated that the label of PCOS is less important than ensuring clinicians treat the symptoms that most bother the patient.

And even if kisspeptin does play a causal role in PCOS for some patients, it’s only a subset of individuals with PCOS who would benefit from therapies developed to target it. Given the complexity of the syndrome and its many manifestations, a “galaxy of pathways” are involved in different potential subtypes of the condition. “You can’t treat PCOS as one entity,” Dr. Pal said.

Still, Dr. Hudson is optimistic that the research into potential neuroendocrine contributions to PCOS will yield therapies that go beyond just managing symptoms.

“There aren’t a lot of treatments available yet, but there may be some on the horizon,” Dr. Hudson said. “We’re still in this very primitive stage in terms of therapeutics, where we’re only addressing specific symptoms, and we haven’t been able to really address the underlying cause because we haven’t understood it as well and because we don’t have therapies that can target it,” Dr. Hudson said. “But once there are therapies developed that will target some of these central mechanisms, I think it will change completely the approach to treating PCOS for patients.”

This story was updated on Sept. 6, 2022.