User login

Acute Kidney Injury Implicated in Multiple Organ Failure

CHICAGO – Early kidney failure was associated with a 19-fold increased risk of multiple organ failure and a sixfold higher risk of death in a retrospective analysis of 1,273 trauma cases.

The study was done at the Rocky Mountain Regional Trauma Center of the University of Colorado at Denver to learn more about the epidemiology of acute kidney injury and its role in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and subsequent multiple organ failure (MOF).

"Of the four major organ systems involved, the kidneys are often overlooked as MOF development has been thought to occur sequentially, being initiated by the lungs," Dr. Max V. Wohlauer said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

He noted that postinjury MOF death rates remain high at 60%, "despite widespread availability [of] renal replacement therapy," and that therefore the prevention of early acute kidney injury could help to reduce complications and death rates in the critically ill.

Conceptually, MOF occurs as patients are resuscitated into a state of early systemic hyperinflammation, explained Dr. Wohlauer, who is now at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle. Although a mild response may be beneficial and will resolve in most patients as they recover, a massive traumatic insult can overwhelm a patient’s response to resuscitation, precipitating early organ failure.

"As neutrophil mediated ischemia-reperfusion injury is thought to be the driving factor in the development of ARDS, recent investigation highlights the critical function of the neutrophils in acute kidney injury as well," Dr. Wohlauer said. "Indeed, emerging evidence indicates that there is a direct contribution of the inflamed, injured kidney in the development of ARDS and MOF. Recent research has shown that acute kidney injury leads to increased vascular permeability and both cellular and soluble inflammation in the lungs, and that acute kidney injury–mediated lung dysfunction begins within hours."

Of the 1,273 patients the study evaluated, 21% went on to develop MOF with an overall mortality of 8%. Early acute kidney injury was detected in only 2% of the patients, but was associated with a 78% MOF rate and a 27% death rate, higher rates than isolated cardiac, liver, or lung dysfunction, Dr. Wohlauer reported. (See box.) The study defined acute kidney injury as an acute increase in creatinine greater than 1.8 mg/dL. Renal replacement therapy was mostly ineffective in these patients, he said.

The most important independent predictors of early acute kidney failure were shock, day 1 crystalloid count, day 2 base deficit, and a need for blood transfusion in the first 12 hours, according to Dr. Wohlauer. "Most patients who developed early kidney injury culminated in full-blown MOF, whereas only 34% of the lung failure cases evolved to ... full MOF," he said.

Dr. Mitchell Jay Cohen of San Francisco General Hospital noted that no consensus exists in the hospital on the definition of acute kidney injury, and that nephrology uses different definitions. "Can you identify a group of patients with acute kidney failure [who] don’t go on to develop multiple organ failure, and what distinguishes these two groups?"

Dr. Wohlauer noted that the renal component of the Denver Postinjury MOF Scale score (creatinine greater than 1.8 mg/dL) correlated strongly with the development of MOF, but that patients with acute kidney injury using the RIFLE (Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, End-Stage Renal Disease) criteria did not go on to develop subsequent MOF.

"We’re suggesting that a creatinine of 1.8 is a severe insult to the kidney, and by the time that occurs [on day 2], a lot of the injury and inflammation has already occurred and we’re pedaling backwards to catch up," he said.

"When it comes to postinjury acute kidney injury, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure," Dr. Wohlauer said. He noted that conservative strategies, including judicious use of IV contrast and rational use of hypotensive resuscitation, may help prevent early acute kidney injury and ensuing MOF.

"Once acute kidney injury had reared its ugly head, renal replacement therapy did very little to alter the progression of disease," he said.

Dr. Wohlauer said he had no conflicts to disclose. The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health.

CHICAGO – Early kidney failure was associated with a 19-fold increased risk of multiple organ failure and a sixfold higher risk of death in a retrospective analysis of 1,273 trauma cases.

The study was done at the Rocky Mountain Regional Trauma Center of the University of Colorado at Denver to learn more about the epidemiology of acute kidney injury and its role in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and subsequent multiple organ failure (MOF).

"Of the four major organ systems involved, the kidneys are often overlooked as MOF development has been thought to occur sequentially, being initiated by the lungs," Dr. Max V. Wohlauer said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

He noted that postinjury MOF death rates remain high at 60%, "despite widespread availability [of] renal replacement therapy," and that therefore the prevention of early acute kidney injury could help to reduce complications and death rates in the critically ill.

Conceptually, MOF occurs as patients are resuscitated into a state of early systemic hyperinflammation, explained Dr. Wohlauer, who is now at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle. Although a mild response may be beneficial and will resolve in most patients as they recover, a massive traumatic insult can overwhelm a patient’s response to resuscitation, precipitating early organ failure.

"As neutrophil mediated ischemia-reperfusion injury is thought to be the driving factor in the development of ARDS, recent investigation highlights the critical function of the neutrophils in acute kidney injury as well," Dr. Wohlauer said. "Indeed, emerging evidence indicates that there is a direct contribution of the inflamed, injured kidney in the development of ARDS and MOF. Recent research has shown that acute kidney injury leads to increased vascular permeability and both cellular and soluble inflammation in the lungs, and that acute kidney injury–mediated lung dysfunction begins within hours."

Of the 1,273 patients the study evaluated, 21% went on to develop MOF with an overall mortality of 8%. Early acute kidney injury was detected in only 2% of the patients, but was associated with a 78% MOF rate and a 27% death rate, higher rates than isolated cardiac, liver, or lung dysfunction, Dr. Wohlauer reported. (See box.) The study defined acute kidney injury as an acute increase in creatinine greater than 1.8 mg/dL. Renal replacement therapy was mostly ineffective in these patients, he said.

The most important independent predictors of early acute kidney failure were shock, day 1 crystalloid count, day 2 base deficit, and a need for blood transfusion in the first 12 hours, according to Dr. Wohlauer. "Most patients who developed early kidney injury culminated in full-blown MOF, whereas only 34% of the lung failure cases evolved to ... full MOF," he said.

Dr. Mitchell Jay Cohen of San Francisco General Hospital noted that no consensus exists in the hospital on the definition of acute kidney injury, and that nephrology uses different definitions. "Can you identify a group of patients with acute kidney failure [who] don’t go on to develop multiple organ failure, and what distinguishes these two groups?"

Dr. Wohlauer noted that the renal component of the Denver Postinjury MOF Scale score (creatinine greater than 1.8 mg/dL) correlated strongly with the development of MOF, but that patients with acute kidney injury using the RIFLE (Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, End-Stage Renal Disease) criteria did not go on to develop subsequent MOF.

"We’re suggesting that a creatinine of 1.8 is a severe insult to the kidney, and by the time that occurs [on day 2], a lot of the injury and inflammation has already occurred and we’re pedaling backwards to catch up," he said.

"When it comes to postinjury acute kidney injury, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure," Dr. Wohlauer said. He noted that conservative strategies, including judicious use of IV contrast and rational use of hypotensive resuscitation, may help prevent early acute kidney injury and ensuing MOF.

"Once acute kidney injury had reared its ugly head, renal replacement therapy did very little to alter the progression of disease," he said.

Dr. Wohlauer said he had no conflicts to disclose. The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health.

CHICAGO – Early kidney failure was associated with a 19-fold increased risk of multiple organ failure and a sixfold higher risk of death in a retrospective analysis of 1,273 trauma cases.

The study was done at the Rocky Mountain Regional Trauma Center of the University of Colorado at Denver to learn more about the epidemiology of acute kidney injury and its role in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and subsequent multiple organ failure (MOF).

"Of the four major organ systems involved, the kidneys are often overlooked as MOF development has been thought to occur sequentially, being initiated by the lungs," Dr. Max V. Wohlauer said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

He noted that postinjury MOF death rates remain high at 60%, "despite widespread availability [of] renal replacement therapy," and that therefore the prevention of early acute kidney injury could help to reduce complications and death rates in the critically ill.

Conceptually, MOF occurs as patients are resuscitated into a state of early systemic hyperinflammation, explained Dr. Wohlauer, who is now at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle. Although a mild response may be beneficial and will resolve in most patients as they recover, a massive traumatic insult can overwhelm a patient’s response to resuscitation, precipitating early organ failure.

"As neutrophil mediated ischemia-reperfusion injury is thought to be the driving factor in the development of ARDS, recent investigation highlights the critical function of the neutrophils in acute kidney injury as well," Dr. Wohlauer said. "Indeed, emerging evidence indicates that there is a direct contribution of the inflamed, injured kidney in the development of ARDS and MOF. Recent research has shown that acute kidney injury leads to increased vascular permeability and both cellular and soluble inflammation in the lungs, and that acute kidney injury–mediated lung dysfunction begins within hours."

Of the 1,273 patients the study evaluated, 21% went on to develop MOF with an overall mortality of 8%. Early acute kidney injury was detected in only 2% of the patients, but was associated with a 78% MOF rate and a 27% death rate, higher rates than isolated cardiac, liver, or lung dysfunction, Dr. Wohlauer reported. (See box.) The study defined acute kidney injury as an acute increase in creatinine greater than 1.8 mg/dL. Renal replacement therapy was mostly ineffective in these patients, he said.

The most important independent predictors of early acute kidney failure were shock, day 1 crystalloid count, day 2 base deficit, and a need for blood transfusion in the first 12 hours, according to Dr. Wohlauer. "Most patients who developed early kidney injury culminated in full-blown MOF, whereas only 34% of the lung failure cases evolved to ... full MOF," he said.

Dr. Mitchell Jay Cohen of San Francisco General Hospital noted that no consensus exists in the hospital on the definition of acute kidney injury, and that nephrology uses different definitions. "Can you identify a group of patients with acute kidney failure [who] don’t go on to develop multiple organ failure, and what distinguishes these two groups?"

Dr. Wohlauer noted that the renal component of the Denver Postinjury MOF Scale score (creatinine greater than 1.8 mg/dL) correlated strongly with the development of MOF, but that patients with acute kidney injury using the RIFLE (Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, End-Stage Renal Disease) criteria did not go on to develop subsequent MOF.

"We’re suggesting that a creatinine of 1.8 is a severe insult to the kidney, and by the time that occurs [on day 2], a lot of the injury and inflammation has already occurred and we’re pedaling backwards to catch up," he said.

"When it comes to postinjury acute kidney injury, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure," Dr. Wohlauer said. He noted that conservative strategies, including judicious use of IV contrast and rational use of hypotensive resuscitation, may help prevent early acute kidney injury and ensuing MOF.

"Once acute kidney injury had reared its ugly head, renal replacement therapy did very little to alter the progression of disease," he said.

Dr. Wohlauer said he had no conflicts to disclose. The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE SURGERY OF TRAUMA

'Play or Pay' Underwrites Trauma Costs in Mississippi

CHICAGO – With reimbursements declining, finding the money to sustain trauma centers is becoming even more crucial for hospitals and the trauma surgeons who staff them, but a Mississippi "play or pay" policy for trauma centers could be a model for other states, according to a recent study.

"The ‘play or pay’ policy in Mississippi was associated with an increase in trauma system participation, and it created increased access for Mississippians, particularly in the southern part of the state," Dr. Ben L. Zarzaur said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Dr. Zarzaur presented an analysis of the state’s "play or pay" program based on 2,815 trauma admissions to the Presley Memorial Trauma Center in Memphis, a level I trauma center that covers southwestern Tennessee and northern Mississippi. Although Mississippi has had a fund for trauma centers for most of the last decade, the Mississippi Trauma Care System Fund underwent a major change in 2008 when the state implemented a "play or pay" policy.

He noted that readiness costs for level I trauma centers were about $2.7 million a year in 2004 (Am. J. Surg. 2004;187:7-13). Under "play or pay," hospitals now either establish a trauma center at a level that the state deems sufficient, or they pay into the fund.

"Fundamentally, 'play or pay' is a social contract with citizens and patients of the most important type."

For example, a hospital with a level III center that the state says should be a level II facility would pay $423,500, and fees can range up to $1.5 million, according to Dr. Zarzaur, a surgeon at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, and the Presley Memorial Trauma Center. Out-of-state trauma centers may participate if an independent review team determines that they comply with Mississippi regulations.

About 15% of the Trauma Care System Fund comes from these hospital fees, said Dr. John Porter of Jackson, Miss., an attendee at the paper presentation and a policy author and trauma surgeon at the University of Mississippi, Oxford, which has the only in-state level I center. The fund had accumulated more than $24 million through 2010, Dr. Zarzaur said. Funding also comes from motor vehicle fees and fines.

Before the policy was enacted in July 2008, 70 of 107 hospitals had trauma centers and two level I centers served the state, Dr. Zarzaur said. Today, 85 of 106 hospitals have trauma centers and a third level I center (the University of South Alabama in neighboring Mobile) has joined the program. "There was also an increase in level II centers in the southern part of the state, which had previously been underserved," Dr. Zarzaur noted.

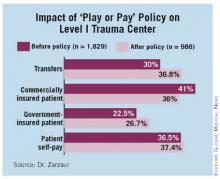

The study found a shift in the payer mix after the policy was put in place, despite similar patient demographics, injury severity, and mortality. Associated with this change in payer mix was an increase in transfers from referring facilities, Dr. Zarzaur said. Among residents of Mississippi, "there was a decrease in the number of commercially insured patients and an increase in government-insured as well as self-pay patients, but there was no similar change in the Tennessee cohort," he said.

Overall, commercially insured patients made up 41% of patients admitted from Mississippi before the policy, compared with 36% since. The ratio of reimbursements to charges declined under the policy to 0.22, compared with 0.26 previously, with a ratio of 1 indicating profit, Dr. Zarzaur said.

At Presley, reimbursements for all patients decreased slightly for the entire cohort, Dr. Zarzaur said. Although that was more pronounced for Mississippians, "play or pay" made up for it. "Funds received from the Trauma Care System Fund almost completely offset this unfavorable change in payer mix," Dr. Zarzaur said.

Discussion leader Dr. David B. Hoyt, professor emeritus of surgery at the University of California, Irvine, and executive director of the American College of Surgeons, applauded the concept. "Fundamentally, ‘play or pay’ is a social contract with citizens and patients of the most important type: It legislates our responsibility to a safety net and allows hospitals to participate either directly or through financial support," he said.

He also noted that California tried to employ a similar funding scheme but abandoned it. "There’s a lesson in this about the persistence and the timing of a policy development that has implications for the AAST and the ACS Committee on Trauma," he said. "This is probably one of best ideas that will come forth as we consider ideas for refinancing our health system."

Dr. Zarzaur said he had no financial conflicts to disclose.

CHICAGO – With reimbursements declining, finding the money to sustain trauma centers is becoming even more crucial for hospitals and the trauma surgeons who staff them, but a Mississippi "play or pay" policy for trauma centers could be a model for other states, according to a recent study.

"The ‘play or pay’ policy in Mississippi was associated with an increase in trauma system participation, and it created increased access for Mississippians, particularly in the southern part of the state," Dr. Ben L. Zarzaur said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Dr. Zarzaur presented an analysis of the state’s "play or pay" program based on 2,815 trauma admissions to the Presley Memorial Trauma Center in Memphis, a level I trauma center that covers southwestern Tennessee and northern Mississippi. Although Mississippi has had a fund for trauma centers for most of the last decade, the Mississippi Trauma Care System Fund underwent a major change in 2008 when the state implemented a "play or pay" policy.

He noted that readiness costs for level I trauma centers were about $2.7 million a year in 2004 (Am. J. Surg. 2004;187:7-13). Under "play or pay," hospitals now either establish a trauma center at a level that the state deems sufficient, or they pay into the fund.

"Fundamentally, 'play or pay' is a social contract with citizens and patients of the most important type."

For example, a hospital with a level III center that the state says should be a level II facility would pay $423,500, and fees can range up to $1.5 million, according to Dr. Zarzaur, a surgeon at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, and the Presley Memorial Trauma Center. Out-of-state trauma centers may participate if an independent review team determines that they comply with Mississippi regulations.

About 15% of the Trauma Care System Fund comes from these hospital fees, said Dr. John Porter of Jackson, Miss., an attendee at the paper presentation and a policy author and trauma surgeon at the University of Mississippi, Oxford, which has the only in-state level I center. The fund had accumulated more than $24 million through 2010, Dr. Zarzaur said. Funding also comes from motor vehicle fees and fines.

Before the policy was enacted in July 2008, 70 of 107 hospitals had trauma centers and two level I centers served the state, Dr. Zarzaur said. Today, 85 of 106 hospitals have trauma centers and a third level I center (the University of South Alabama in neighboring Mobile) has joined the program. "There was also an increase in level II centers in the southern part of the state, which had previously been underserved," Dr. Zarzaur noted.

The study found a shift in the payer mix after the policy was put in place, despite similar patient demographics, injury severity, and mortality. Associated with this change in payer mix was an increase in transfers from referring facilities, Dr. Zarzaur said. Among residents of Mississippi, "there was a decrease in the number of commercially insured patients and an increase in government-insured as well as self-pay patients, but there was no similar change in the Tennessee cohort," he said.

Overall, commercially insured patients made up 41% of patients admitted from Mississippi before the policy, compared with 36% since. The ratio of reimbursements to charges declined under the policy to 0.22, compared with 0.26 previously, with a ratio of 1 indicating profit, Dr. Zarzaur said.

At Presley, reimbursements for all patients decreased slightly for the entire cohort, Dr. Zarzaur said. Although that was more pronounced for Mississippians, "play or pay" made up for it. "Funds received from the Trauma Care System Fund almost completely offset this unfavorable change in payer mix," Dr. Zarzaur said.

Discussion leader Dr. David B. Hoyt, professor emeritus of surgery at the University of California, Irvine, and executive director of the American College of Surgeons, applauded the concept. "Fundamentally, ‘play or pay’ is a social contract with citizens and patients of the most important type: It legislates our responsibility to a safety net and allows hospitals to participate either directly or through financial support," he said.

He also noted that California tried to employ a similar funding scheme but abandoned it. "There’s a lesson in this about the persistence and the timing of a policy development that has implications for the AAST and the ACS Committee on Trauma," he said. "This is probably one of best ideas that will come forth as we consider ideas for refinancing our health system."

Dr. Zarzaur said he had no financial conflicts to disclose.

CHICAGO – With reimbursements declining, finding the money to sustain trauma centers is becoming even more crucial for hospitals and the trauma surgeons who staff them, but a Mississippi "play or pay" policy for trauma centers could be a model for other states, according to a recent study.

"The ‘play or pay’ policy in Mississippi was associated with an increase in trauma system participation, and it created increased access for Mississippians, particularly in the southern part of the state," Dr. Ben L. Zarzaur said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Dr. Zarzaur presented an analysis of the state’s "play or pay" program based on 2,815 trauma admissions to the Presley Memorial Trauma Center in Memphis, a level I trauma center that covers southwestern Tennessee and northern Mississippi. Although Mississippi has had a fund for trauma centers for most of the last decade, the Mississippi Trauma Care System Fund underwent a major change in 2008 when the state implemented a "play or pay" policy.

He noted that readiness costs for level I trauma centers were about $2.7 million a year in 2004 (Am. J. Surg. 2004;187:7-13). Under "play or pay," hospitals now either establish a trauma center at a level that the state deems sufficient, or they pay into the fund.

"Fundamentally, 'play or pay' is a social contract with citizens and patients of the most important type."

For example, a hospital with a level III center that the state says should be a level II facility would pay $423,500, and fees can range up to $1.5 million, according to Dr. Zarzaur, a surgeon at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, and the Presley Memorial Trauma Center. Out-of-state trauma centers may participate if an independent review team determines that they comply with Mississippi regulations.

About 15% of the Trauma Care System Fund comes from these hospital fees, said Dr. John Porter of Jackson, Miss., an attendee at the paper presentation and a policy author and trauma surgeon at the University of Mississippi, Oxford, which has the only in-state level I center. The fund had accumulated more than $24 million through 2010, Dr. Zarzaur said. Funding also comes from motor vehicle fees and fines.

Before the policy was enacted in July 2008, 70 of 107 hospitals had trauma centers and two level I centers served the state, Dr. Zarzaur said. Today, 85 of 106 hospitals have trauma centers and a third level I center (the University of South Alabama in neighboring Mobile) has joined the program. "There was also an increase in level II centers in the southern part of the state, which had previously been underserved," Dr. Zarzaur noted.

The study found a shift in the payer mix after the policy was put in place, despite similar patient demographics, injury severity, and mortality. Associated with this change in payer mix was an increase in transfers from referring facilities, Dr. Zarzaur said. Among residents of Mississippi, "there was a decrease in the number of commercially insured patients and an increase in government-insured as well as self-pay patients, but there was no similar change in the Tennessee cohort," he said.

Overall, commercially insured patients made up 41% of patients admitted from Mississippi before the policy, compared with 36% since. The ratio of reimbursements to charges declined under the policy to 0.22, compared with 0.26 previously, with a ratio of 1 indicating profit, Dr. Zarzaur said.

At Presley, reimbursements for all patients decreased slightly for the entire cohort, Dr. Zarzaur said. Although that was more pronounced for Mississippians, "play or pay" made up for it. "Funds received from the Trauma Care System Fund almost completely offset this unfavorable change in payer mix," Dr. Zarzaur said.

Discussion leader Dr. David B. Hoyt, professor emeritus of surgery at the University of California, Irvine, and executive director of the American College of Surgeons, applauded the concept. "Fundamentally, ‘play or pay’ is a social contract with citizens and patients of the most important type: It legislates our responsibility to a safety net and allows hospitals to participate either directly or through financial support," he said.

He also noted that California tried to employ a similar funding scheme but abandoned it. "There’s a lesson in this about the persistence and the timing of a policy development that has implications for the AAST and the ACS Committee on Trauma," he said. "This is probably one of best ideas that will come forth as we consider ideas for refinancing our health system."

Dr. Zarzaur said he had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE SURGERY OF TRAUMA

Trauma Funding Cuts May Jeopardize Care of Immigrants

CHICAGO – Funding sources to cover care for undocumented immigrants have pulled back since 2008 and will continue to do so after the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act takes full effect. Although the legislation strives to provide nearly universal health insurance coverage by 2014, undocumented immigrants are not included, and one hospital’s experience with dwindling reimbursement portends a cloudy future for paying for care in this patient population.

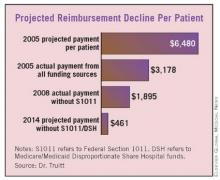

Even when the Affordable Care Act takes full effect, about 22 million people will still lack coverage – 10-15 million of whom will be undocumented immigrants, according to Dr. Michael S. Truitt of Methodist Dallas Medical Center. The Affordable Care Act will cut Medicare/Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) funds by about 75% between 2014 and 2019.

"We have serious and specific concerns about how the cut in DSH funding could affect trauma centers and safety net hospitals," Dr. Truitt said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. "On a per-patient basis at our institution, projected payments decrease from $6,480 in 2005 to $461 in 2014."

He presented a study that evaluated retrospectively 183,000 visits to his hospital’s emergency department from 2005 to 2008. Of those, 6,691 were undocumented immigrants, and about 20% of their visits were trauma related, he said.

The study focused on the four main funding mechanisms for the care of undocumented immigrants in Texas: self-payment; the Texas Driver Responsibility Program (DRP), which uses motor vehicle fines; federal Section 1011 funds; and DSH funds.

The state DRP program distributes $70 million to $90 million to Texas hospitals annually, Dr. Truitt said, but even that has been problematic. "Significantly more has been collected each year and earmarked for trauma, but disbursement from the state has not always been consistent," he said.

Section 1011 distributed about $1 billion from 2005 to 2008, one-third of which went to the eight states bordering Mexico, but that program has been unfunded since 2008, according to Dr. Truitt. Medicare/Medicaid DSH funds distributed $19.1 billion to U.S. hospitals in 2009, but these funds are used to subsidize numerous programs and are not specific to care of indigent trauma patients.

From May 2005 to May 2008, Methodist Dallas Medical Center actually collected about $4.2 million from these varied sources for uncompensated undocumented immigrant trauma care – about $4.9 million less than the hospital’s usual fees, Dr. Truitt said. These funds were shared by the hospital, ED physicians, and trauma surgeons, he noted.

"In the end, this may be just another call for fiscal responsibility on the part of trauma centers to reduce unnecessary charges and waste, such as robust use of CT scans, laboratory tests, etc. – not just for the undocumented immigrant trauma patients, but for all compensated and uncompensated patients," said Dr. Thomas Esposito of Loyola University, Chicago. He asked whether the authors had any suggestions for alternative funding sources, and whether states and trauma systems should take it upon themselves to establish or increase revenue from sources similar to the Texas Driver Responsibility Program.

Dr. Truitt called on policy makers to prioritize funding for trauma centers and safety net hospitals. "If it’s a federal responsibility, so be it, but it should be supported by a program that is not subject to the political winds. If it’s a state responsibility, the states should have the authority to collect these funds and ensure they are disbursed to the intended recipients expeditiously and consistently."

Dr. Truitt and his colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Funding sources to cover care for undocumented immigrants have pulled back since 2008 and will continue to do so after the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act takes full effect. Although the legislation strives to provide nearly universal health insurance coverage by 2014, undocumented immigrants are not included, and one hospital’s experience with dwindling reimbursement portends a cloudy future for paying for care in this patient population.

Even when the Affordable Care Act takes full effect, about 22 million people will still lack coverage – 10-15 million of whom will be undocumented immigrants, according to Dr. Michael S. Truitt of Methodist Dallas Medical Center. The Affordable Care Act will cut Medicare/Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) funds by about 75% between 2014 and 2019.

"We have serious and specific concerns about how the cut in DSH funding could affect trauma centers and safety net hospitals," Dr. Truitt said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. "On a per-patient basis at our institution, projected payments decrease from $6,480 in 2005 to $461 in 2014."

He presented a study that evaluated retrospectively 183,000 visits to his hospital’s emergency department from 2005 to 2008. Of those, 6,691 were undocumented immigrants, and about 20% of their visits were trauma related, he said.

The study focused on the four main funding mechanisms for the care of undocumented immigrants in Texas: self-payment; the Texas Driver Responsibility Program (DRP), which uses motor vehicle fines; federal Section 1011 funds; and DSH funds.

The state DRP program distributes $70 million to $90 million to Texas hospitals annually, Dr. Truitt said, but even that has been problematic. "Significantly more has been collected each year and earmarked for trauma, but disbursement from the state has not always been consistent," he said.

Section 1011 distributed about $1 billion from 2005 to 2008, one-third of which went to the eight states bordering Mexico, but that program has been unfunded since 2008, according to Dr. Truitt. Medicare/Medicaid DSH funds distributed $19.1 billion to U.S. hospitals in 2009, but these funds are used to subsidize numerous programs and are not specific to care of indigent trauma patients.

From May 2005 to May 2008, Methodist Dallas Medical Center actually collected about $4.2 million from these varied sources for uncompensated undocumented immigrant trauma care – about $4.9 million less than the hospital’s usual fees, Dr. Truitt said. These funds were shared by the hospital, ED physicians, and trauma surgeons, he noted.

"In the end, this may be just another call for fiscal responsibility on the part of trauma centers to reduce unnecessary charges and waste, such as robust use of CT scans, laboratory tests, etc. – not just for the undocumented immigrant trauma patients, but for all compensated and uncompensated patients," said Dr. Thomas Esposito of Loyola University, Chicago. He asked whether the authors had any suggestions for alternative funding sources, and whether states and trauma systems should take it upon themselves to establish or increase revenue from sources similar to the Texas Driver Responsibility Program.

Dr. Truitt called on policy makers to prioritize funding for trauma centers and safety net hospitals. "If it’s a federal responsibility, so be it, but it should be supported by a program that is not subject to the political winds. If it’s a state responsibility, the states should have the authority to collect these funds and ensure they are disbursed to the intended recipients expeditiously and consistently."

Dr. Truitt and his colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Funding sources to cover care for undocumented immigrants have pulled back since 2008 and will continue to do so after the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act takes full effect. Although the legislation strives to provide nearly universal health insurance coverage by 2014, undocumented immigrants are not included, and one hospital’s experience with dwindling reimbursement portends a cloudy future for paying for care in this patient population.

Even when the Affordable Care Act takes full effect, about 22 million people will still lack coverage – 10-15 million of whom will be undocumented immigrants, according to Dr. Michael S. Truitt of Methodist Dallas Medical Center. The Affordable Care Act will cut Medicare/Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) funds by about 75% between 2014 and 2019.

"We have serious and specific concerns about how the cut in DSH funding could affect trauma centers and safety net hospitals," Dr. Truitt said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. "On a per-patient basis at our institution, projected payments decrease from $6,480 in 2005 to $461 in 2014."

He presented a study that evaluated retrospectively 183,000 visits to his hospital’s emergency department from 2005 to 2008. Of those, 6,691 were undocumented immigrants, and about 20% of their visits were trauma related, he said.

The study focused on the four main funding mechanisms for the care of undocumented immigrants in Texas: self-payment; the Texas Driver Responsibility Program (DRP), which uses motor vehicle fines; federal Section 1011 funds; and DSH funds.

The state DRP program distributes $70 million to $90 million to Texas hospitals annually, Dr. Truitt said, but even that has been problematic. "Significantly more has been collected each year and earmarked for trauma, but disbursement from the state has not always been consistent," he said.

Section 1011 distributed about $1 billion from 2005 to 2008, one-third of which went to the eight states bordering Mexico, but that program has been unfunded since 2008, according to Dr. Truitt. Medicare/Medicaid DSH funds distributed $19.1 billion to U.S. hospitals in 2009, but these funds are used to subsidize numerous programs and are not specific to care of indigent trauma patients.

From May 2005 to May 2008, Methodist Dallas Medical Center actually collected about $4.2 million from these varied sources for uncompensated undocumented immigrant trauma care – about $4.9 million less than the hospital’s usual fees, Dr. Truitt said. These funds were shared by the hospital, ED physicians, and trauma surgeons, he noted.

"In the end, this may be just another call for fiscal responsibility on the part of trauma centers to reduce unnecessary charges and waste, such as robust use of CT scans, laboratory tests, etc. – not just for the undocumented immigrant trauma patients, but for all compensated and uncompensated patients," said Dr. Thomas Esposito of Loyola University, Chicago. He asked whether the authors had any suggestions for alternative funding sources, and whether states and trauma systems should take it upon themselves to establish or increase revenue from sources similar to the Texas Driver Responsibility Program.

Dr. Truitt called on policy makers to prioritize funding for trauma centers and safety net hospitals. "If it’s a federal responsibility, so be it, but it should be supported by a program that is not subject to the political winds. If it’s a state responsibility, the states should have the authority to collect these funds and ensure they are disbursed to the intended recipients expeditiously and consistently."

Dr. Truitt and his colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE SURGERY OF TRAUMA

Survival Trends Promising in Geriatric Trauma Patients

CHICAGO – Long-term survival in severely injured geriatric trauma patients may not be as poor as once thought, according to a study at a level 1 trauma center in Pennsylvania that followed these patients for up to 10 years after discharge.

The retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma showed an overall death rate of 33% in elderly patients with brain injury, and almost two-thirds of the patients who survived their initial hospitalization were alive at the conclusion of the study, according to Dr. Ulunna Ofurum of St. Luke’s Hospital in Bethlehem, Pa.

Dr. Ofurum and her colleagues undertook their study to learn whether aggressive care in this population was futile. Trauma patients aged 65 and older with an Injury Severity Score of 30 or higher were assigned to two groups based on the presence or absence of brain injury, with an Abbreviated Injury Scale score of 3 or higher as the cutoff. The Social Security Death Index database was used to determine survival status.

"The initial drop in survivorship was most pronounced in the patients with severe head injury," she said. Overall, 97 of the 145 patients survived hospital discharge, but nearly a third died after hospital discharge. That left 65 for analysis of current living status, Dr. Ofurum said. Of those, 52 patients in the head-injured group had a median survival of 33 months, and 13 of the patients without head injury had a median survival of 49 months.

Of the 65 who were still alive when the study ended, 47 were contacted by phone to determine their living arrangements. Overall, 31 (65%) were at home, 11 (23%) were in skilled nursing facilities, four (8%) were at assisted living centers, and one (2%) was in a rehabilitation center.

"The most significant finding of this study is that severely injured geriatric trauma patients who survive their hospitalization have appreciable long-term survival and that a surprising number return home," Dr. Ofurum said. "This study showed that the 5-year survival is almost 20%, which is similar to that of many cancer diagnoses."

She noted that she and her coinvestigators did not apply a uniform approach to the resuscitation variable in all geriatric trauma patients; instead, they used a case-by-case approach. "There is a preselection bias for patients with the most devastating injuries, as we tend not to treat them," she said.

Dr. Ofurum acknowledged some limitations of the study, including its retrospective nature, the small sample size, and the lack of data on cause of death, comorbidities, and survivors’ functional status.

"However, in our practice, it’s been noted that about one-third of deaths that occur in geriatric trauma patients are associated with immediate withdrawal of care," she said. This makes managing complications critical in this patient group. "When patients have complications such as renal failure, families may tend to withdraw care," she said.

With the exponential growth of the elderly population, this and similar studies are notable, said discussion leader Dr. Roxie Albrecht of the University of Oklahoma in Oklahoma City. "Studies such as this do give us a glimmer of hope that not every patient over the age of 65 has the Grim Reaper standing over them, predicting that they will either die in the hospital or never return to their prehospital living status," she said. She noted that the St. Luke’s study is consistent with other reports on elderly trauma (J. Trauma 1998;44:618-23; J. Trauma 2002;52:242-6).

Dr. Ofurum had no conflicts to disclose.

CHICAGO – Long-term survival in severely injured geriatric trauma patients may not be as poor as once thought, according to a study at a level 1 trauma center in Pennsylvania that followed these patients for up to 10 years after discharge.

The retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma showed an overall death rate of 33% in elderly patients with brain injury, and almost two-thirds of the patients who survived their initial hospitalization were alive at the conclusion of the study, according to Dr. Ulunna Ofurum of St. Luke’s Hospital in Bethlehem, Pa.

Dr. Ofurum and her colleagues undertook their study to learn whether aggressive care in this population was futile. Trauma patients aged 65 and older with an Injury Severity Score of 30 or higher were assigned to two groups based on the presence or absence of brain injury, with an Abbreviated Injury Scale score of 3 or higher as the cutoff. The Social Security Death Index database was used to determine survival status.

"The initial drop in survivorship was most pronounced in the patients with severe head injury," she said. Overall, 97 of the 145 patients survived hospital discharge, but nearly a third died after hospital discharge. That left 65 for analysis of current living status, Dr. Ofurum said. Of those, 52 patients in the head-injured group had a median survival of 33 months, and 13 of the patients without head injury had a median survival of 49 months.

Of the 65 who were still alive when the study ended, 47 were contacted by phone to determine their living arrangements. Overall, 31 (65%) were at home, 11 (23%) were in skilled nursing facilities, four (8%) were at assisted living centers, and one (2%) was in a rehabilitation center.

"The most significant finding of this study is that severely injured geriatric trauma patients who survive their hospitalization have appreciable long-term survival and that a surprising number return home," Dr. Ofurum said. "This study showed that the 5-year survival is almost 20%, which is similar to that of many cancer diagnoses."

She noted that she and her coinvestigators did not apply a uniform approach to the resuscitation variable in all geriatric trauma patients; instead, they used a case-by-case approach. "There is a preselection bias for patients with the most devastating injuries, as we tend not to treat them," she said.

Dr. Ofurum acknowledged some limitations of the study, including its retrospective nature, the small sample size, and the lack of data on cause of death, comorbidities, and survivors’ functional status.

"However, in our practice, it’s been noted that about one-third of deaths that occur in geriatric trauma patients are associated with immediate withdrawal of care," she said. This makes managing complications critical in this patient group. "When patients have complications such as renal failure, families may tend to withdraw care," she said.

With the exponential growth of the elderly population, this and similar studies are notable, said discussion leader Dr. Roxie Albrecht of the University of Oklahoma in Oklahoma City. "Studies such as this do give us a glimmer of hope that not every patient over the age of 65 has the Grim Reaper standing over them, predicting that they will either die in the hospital or never return to their prehospital living status," she said. She noted that the St. Luke’s study is consistent with other reports on elderly trauma (J. Trauma 1998;44:618-23; J. Trauma 2002;52:242-6).

Dr. Ofurum had no conflicts to disclose.

CHICAGO – Long-term survival in severely injured geriatric trauma patients may not be as poor as once thought, according to a study at a level 1 trauma center in Pennsylvania that followed these patients for up to 10 years after discharge.

The retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma showed an overall death rate of 33% in elderly patients with brain injury, and almost two-thirds of the patients who survived their initial hospitalization were alive at the conclusion of the study, according to Dr. Ulunna Ofurum of St. Luke’s Hospital in Bethlehem, Pa.

Dr. Ofurum and her colleagues undertook their study to learn whether aggressive care in this population was futile. Trauma patients aged 65 and older with an Injury Severity Score of 30 or higher were assigned to two groups based on the presence or absence of brain injury, with an Abbreviated Injury Scale score of 3 or higher as the cutoff. The Social Security Death Index database was used to determine survival status.

"The initial drop in survivorship was most pronounced in the patients with severe head injury," she said. Overall, 97 of the 145 patients survived hospital discharge, but nearly a third died after hospital discharge. That left 65 for analysis of current living status, Dr. Ofurum said. Of those, 52 patients in the head-injured group had a median survival of 33 months, and 13 of the patients without head injury had a median survival of 49 months.

Of the 65 who were still alive when the study ended, 47 were contacted by phone to determine their living arrangements. Overall, 31 (65%) were at home, 11 (23%) were in skilled nursing facilities, four (8%) were at assisted living centers, and one (2%) was in a rehabilitation center.

"The most significant finding of this study is that severely injured geriatric trauma patients who survive their hospitalization have appreciable long-term survival and that a surprising number return home," Dr. Ofurum said. "This study showed that the 5-year survival is almost 20%, which is similar to that of many cancer diagnoses."

She noted that she and her coinvestigators did not apply a uniform approach to the resuscitation variable in all geriatric trauma patients; instead, they used a case-by-case approach. "There is a preselection bias for patients with the most devastating injuries, as we tend not to treat them," she said.

Dr. Ofurum acknowledged some limitations of the study, including its retrospective nature, the small sample size, and the lack of data on cause of death, comorbidities, and survivors’ functional status.

"However, in our practice, it’s been noted that about one-third of deaths that occur in geriatric trauma patients are associated with immediate withdrawal of care," she said. This makes managing complications critical in this patient group. "When patients have complications such as renal failure, families may tend to withdraw care," she said.

With the exponential growth of the elderly population, this and similar studies are notable, said discussion leader Dr. Roxie Albrecht of the University of Oklahoma in Oklahoma City. "Studies such as this do give us a glimmer of hope that not every patient over the age of 65 has the Grim Reaper standing over them, predicting that they will either die in the hospital or never return to their prehospital living status," she said. She noted that the St. Luke’s study is consistent with other reports on elderly trauma (J. Trauma 1998;44:618-23; J. Trauma 2002;52:242-6).

Dr. Ofurum had no conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE SURGERY OF TRAUMA

Major Finding: Long-term survival in geriatric trauma patients may not be as poor as once thought. Almost two-thirds of the patients who survived their initial hospitalization were alive at the conclusion of the study.

Data Source: A 10-year retrospective study of 145 severely injured geriatric trauma patients at a level 1 trauma center.

Disclosures: Dr. Ofurum had no conflicts to disclose.

Doubt Cast on Protocol for VAP Resolution

CHICAGO – Use of the Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score to guide therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients has had mixed results, and a recent study has raised further questions about whether CPIS can accurately determine resolution of the infection in critically injured trauma ICU patients.

"Using CPIS to determine the appropriate duration of antimicrobial therapy in trauma patients could potentially be harmful by unnecessarily prolonging exposure to antibiotics," Dr. Nancy A. Parks said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. It could also lead to undertreatment, resulting in relapse, she noted.

Conventional diagnosis of ventilator-assisted pneumonia (VAP) has been based on a CPIS of 6 or higher, but her 6-year study of 1,028 critically ill patients diagnosed with VAP showed resolution of VAP in patients with higher CPIS scores.

Dr. Parks, of the Elvis Presley Memorial Trauma Center in Memphis, cited previously published work that questioned the ability of the CPIS to help differentiate the infection of VAP from posttraumatic systemic inflammatory response syndrome (J. Trauma 2006;60:523-8). While this study explored the efficacy of CPIS for initiating antibiotic therapy, it left unanswered the question of whether CPIS could help determine when to end therapy.

Dr. Parks and her coinvestigators answered that in the negative.

Their protocol to confirm VAP involved using bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in patients with a clinical suspicion of VAP based on three of four elements in the CPIS: body temperature, white cell count, purulent secretions, or new or changing infiltrate on chest x-ray. The investigators started patients on antibiotics empirically, then adjusted treatment if BAL effluent was 105 colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter or higher. The investigators considered VAP resolved if repeat BAL showed a reading of 103 CFU/mL or less on day 4 of therapy. If repeat BAL was done within 2 weeks, they considered any findings greater than 105 CFU/mL as a recurrence.

The study population, which had an average Injury Severity Score of 31 and an average base deficit of 4.4, was composed primarily of blunt trauma patients, Dr. Parks reported. Overall mortality was 9.4%. Slightly more than half of the patients had community-acquired pathogens (50% methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus [MSSA], the remainder split between streptococcus and haemophilus), and slightly fewer had hospital-acquired infections (including about 19% methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA] and 27% pseudomonas). The recurrence rate was 1% overall.

A CPIS score of 6 or greater is considered positive for VAP, but this study showed resolution of VAP at CPIS scores above that. "The average CPIS on discontinuation of antibiotics was 6.9 in the community-acquired group and 6.3 in the hospital-acquired group – both well above our clinical cutoff of 6," Dr. Parks said.

"If we had used CPIS to guide treatment, we would have seen a sensitivity of 69% in our community-acquired group and 72% in our hospital-acquired group," Dr. Parks said. "Specificity would have been 51% and 53%, respectively. Our positive predictive value was 59% and 61%, and negative predictive value 62% and 66%. If we were to use CPIS to guide therapy, 59% of our patients would have had antibiotics continued inappropriately."

"This disparity – that CPIS may be potentially beneficial and useful in medical patients but not in trauma patients – is very important," said Dr. Lena Napolitano, a discussant at the meeting. "It will have important implications, particularly as we strive nationally to modify the definition of VAP and optimize duration of microbial therapy for VAP, hoping to move toward more short-term antimicrobial therapy and hopefully not lead to greater prevalence of recurrent pneumonia," said Dr. Napolitano, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Parks had no disclosures, and the study received no outside funding.

CHICAGO – Use of the Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score to guide therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients has had mixed results, and a recent study has raised further questions about whether CPIS can accurately determine resolution of the infection in critically injured trauma ICU patients.

"Using CPIS to determine the appropriate duration of antimicrobial therapy in trauma patients could potentially be harmful by unnecessarily prolonging exposure to antibiotics," Dr. Nancy A. Parks said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. It could also lead to undertreatment, resulting in relapse, she noted.

Conventional diagnosis of ventilator-assisted pneumonia (VAP) has been based on a CPIS of 6 or higher, but her 6-year study of 1,028 critically ill patients diagnosed with VAP showed resolution of VAP in patients with higher CPIS scores.

Dr. Parks, of the Elvis Presley Memorial Trauma Center in Memphis, cited previously published work that questioned the ability of the CPIS to help differentiate the infection of VAP from posttraumatic systemic inflammatory response syndrome (J. Trauma 2006;60:523-8). While this study explored the efficacy of CPIS for initiating antibiotic therapy, it left unanswered the question of whether CPIS could help determine when to end therapy.

Dr. Parks and her coinvestigators answered that in the negative.

Their protocol to confirm VAP involved using bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in patients with a clinical suspicion of VAP based on three of four elements in the CPIS: body temperature, white cell count, purulent secretions, or new or changing infiltrate on chest x-ray. The investigators started patients on antibiotics empirically, then adjusted treatment if BAL effluent was 105 colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter or higher. The investigators considered VAP resolved if repeat BAL showed a reading of 103 CFU/mL or less on day 4 of therapy. If repeat BAL was done within 2 weeks, they considered any findings greater than 105 CFU/mL as a recurrence.

The study population, which had an average Injury Severity Score of 31 and an average base deficit of 4.4, was composed primarily of blunt trauma patients, Dr. Parks reported. Overall mortality was 9.4%. Slightly more than half of the patients had community-acquired pathogens (50% methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus [MSSA], the remainder split between streptococcus and haemophilus), and slightly fewer had hospital-acquired infections (including about 19% methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA] and 27% pseudomonas). The recurrence rate was 1% overall.

A CPIS score of 6 or greater is considered positive for VAP, but this study showed resolution of VAP at CPIS scores above that. "The average CPIS on discontinuation of antibiotics was 6.9 in the community-acquired group and 6.3 in the hospital-acquired group – both well above our clinical cutoff of 6," Dr. Parks said.

"If we had used CPIS to guide treatment, we would have seen a sensitivity of 69% in our community-acquired group and 72% in our hospital-acquired group," Dr. Parks said. "Specificity would have been 51% and 53%, respectively. Our positive predictive value was 59% and 61%, and negative predictive value 62% and 66%. If we were to use CPIS to guide therapy, 59% of our patients would have had antibiotics continued inappropriately."

"This disparity – that CPIS may be potentially beneficial and useful in medical patients but not in trauma patients – is very important," said Dr. Lena Napolitano, a discussant at the meeting. "It will have important implications, particularly as we strive nationally to modify the definition of VAP and optimize duration of microbial therapy for VAP, hoping to move toward more short-term antimicrobial therapy and hopefully not lead to greater prevalence of recurrent pneumonia," said Dr. Napolitano, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Parks had no disclosures, and the study received no outside funding.

CHICAGO – Use of the Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score to guide therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients has had mixed results, and a recent study has raised further questions about whether CPIS can accurately determine resolution of the infection in critically injured trauma ICU patients.

"Using CPIS to determine the appropriate duration of antimicrobial therapy in trauma patients could potentially be harmful by unnecessarily prolonging exposure to antibiotics," Dr. Nancy A. Parks said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. It could also lead to undertreatment, resulting in relapse, she noted.

Conventional diagnosis of ventilator-assisted pneumonia (VAP) has been based on a CPIS of 6 or higher, but her 6-year study of 1,028 critically ill patients diagnosed with VAP showed resolution of VAP in patients with higher CPIS scores.

Dr. Parks, of the Elvis Presley Memorial Trauma Center in Memphis, cited previously published work that questioned the ability of the CPIS to help differentiate the infection of VAP from posttraumatic systemic inflammatory response syndrome (J. Trauma 2006;60:523-8). While this study explored the efficacy of CPIS for initiating antibiotic therapy, it left unanswered the question of whether CPIS could help determine when to end therapy.

Dr. Parks and her coinvestigators answered that in the negative.

Their protocol to confirm VAP involved using bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in patients with a clinical suspicion of VAP based on three of four elements in the CPIS: body temperature, white cell count, purulent secretions, or new or changing infiltrate on chest x-ray. The investigators started patients on antibiotics empirically, then adjusted treatment if BAL effluent was 105 colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter or higher. The investigators considered VAP resolved if repeat BAL showed a reading of 103 CFU/mL or less on day 4 of therapy. If repeat BAL was done within 2 weeks, they considered any findings greater than 105 CFU/mL as a recurrence.

The study population, which had an average Injury Severity Score of 31 and an average base deficit of 4.4, was composed primarily of blunt trauma patients, Dr. Parks reported. Overall mortality was 9.4%. Slightly more than half of the patients had community-acquired pathogens (50% methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus [MSSA], the remainder split between streptococcus and haemophilus), and slightly fewer had hospital-acquired infections (including about 19% methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA] and 27% pseudomonas). The recurrence rate was 1% overall.

A CPIS score of 6 or greater is considered positive for VAP, but this study showed resolution of VAP at CPIS scores above that. "The average CPIS on discontinuation of antibiotics was 6.9 in the community-acquired group and 6.3 in the hospital-acquired group – both well above our clinical cutoff of 6," Dr. Parks said.

"If we had used CPIS to guide treatment, we would have seen a sensitivity of 69% in our community-acquired group and 72% in our hospital-acquired group," Dr. Parks said. "Specificity would have been 51% and 53%, respectively. Our positive predictive value was 59% and 61%, and negative predictive value 62% and 66%. If we were to use CPIS to guide therapy, 59% of our patients would have had antibiotics continued inappropriately."

"This disparity – that CPIS may be potentially beneficial and useful in medical patients but not in trauma patients – is very important," said Dr. Lena Napolitano, a discussant at the meeting. "It will have important implications, particularly as we strive nationally to modify the definition of VAP and optimize duration of microbial therapy for VAP, hoping to move toward more short-term antimicrobial therapy and hopefully not lead to greater prevalence of recurrent pneumonia," said Dr. Napolitano, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Parks had no disclosures, and the study received no outside funding.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE SURGERY OF TRAUMA

Are Benchmarks the Problem for High VAP Rates?

CHICAGO – Payers are relying ever more on tying physician and hospital payments to quality measures, but what happens if the benchmarks they use vary among institutions or are flawed? Such may be the case with ventilator-associated pneumonia and large trauma centers, as a recent study shows VAP rates at such facilities exceed national benchmarks, which some say are inadequate for comparison.

Dr. Christopher P. Michetti of Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va., presented a retrospective study designed to determine VAP rates at major trauma centers and to lay groundwork for more accurate benchmarking that relies less on National Health Safety Network data, he said. He spoke at the annual meeting of the American Association for Surgery in Trauma. The study was performed through the AAST Multi-Institutional Trials Committee.

"Hospitals are under pressure to reduce their VAP rates, yet a direct association between VAP rates and quality of care or outcomes has not been demonstrated," he remarked.

"VAP rates ...are remarkably variable," Dr. Michetti said. "It is not appropriate to measure all trauma centers against a single benchmark, nor does an actual benchmark appear to exist at this point." Comparing VAP rates between different trauma centers is "like comparing apples and oranges," he said.

The study looked at VAP rates at 47 level I and II trauma centers for 2008 and 2009 with an average of 3,000 trauma evaluations a year. The average VAP rate for the study group was 17.2/1,000 ventilator days, compared with 8.1/1,000 for NHSN data. "In fact, the 90th-percentile rate for NHSN was still below the mean rate from our study," Dr. Michetti said. Across all 47 centers in the study, VAP rates ranged from a low of 1.8/1,000 ventilator days to a high of 57.6/1,000 ventilator days.

The case mix at the trauma centers did not auger well for lower VAP rates, as 88% of the cases were blunt trauma, Dr. Michetti noted. "VAP rates are generally higher for blunt-trauma patients, at about 17/1,000 ventilator days, compared with penetrating trauma at 11/1,000," he said.

Most other variables among the centers in the study – such as having a closed or open ICU, or using a bacteriologic vs. a clinical strategy to diagnose VAP – showed little impact on the pneumonia rates. VAP rates did not correlate with the size or level of trauma center, injury severity or type of ICU, he said.

Among the problems he noted with the NHSN data on VAP rates are the lack of source hospital identification, population risk, or injury severity stratification. "In addition, the NHSN rates are substantially lower than other published rates among trauma patients," he said.

However, the investigators did isolate a few variables that may influence VAP rates: Among centers where the trauma service alone made the diagnosis, the average VAP rate was 27.5/1,000 ventilator days. When the infection control, quality, or epidemiology department made the call, the average VAP rate was 11.9/1,000 days. Centers that excluded patients also had rates about 30% lower than those that did not. This variability raises questions about using VAP as a quality measure, Dr. Michetti said. "Before we take that leap, diagnostic and reporting standards are necessary."

The heightened attention on VAP as a quality measure for critical care is having other implications, he said. "As pressure to reduce VAP rates grows, an increasing number of patients are being labeled as having ventilator-associated tracheobronchitis or excluded for reasons such as aspiration," he said.

Discussant Dr. Karen J. Brasel of the Medical College of Wisconsin in, Milwaukee, acknowledged the need for the study, but raised the question: "Are the benchmarks the problem, or are we the problem?"

"I think the answer is yes, both," Dr. Michetti said. "I’m not sure that an adequate benchmark exists probably because no representative sample of trauma centers has been done to set that benchmark." He noted that the CDC’s Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee does not recommend reporting of VAP, which argues against using that as a benchmark. Meanwhile, across individual centers no reporting standards exist, "so centers can’t agree on what is VAP," Dr. Michetti said.

Dr. Michetti had no disclosures, and the study received no outside funding.

CHICAGO – Payers are relying ever more on tying physician and hospital payments to quality measures, but what happens if the benchmarks they use vary among institutions or are flawed? Such may be the case with ventilator-associated pneumonia and large trauma centers, as a recent study shows VAP rates at such facilities exceed national benchmarks, which some say are inadequate for comparison.

Dr. Christopher P. Michetti of Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va., presented a retrospective study designed to determine VAP rates at major trauma centers and to lay groundwork for more accurate benchmarking that relies less on National Health Safety Network data, he said. He spoke at the annual meeting of the American Association for Surgery in Trauma. The study was performed through the AAST Multi-Institutional Trials Committee.

"Hospitals are under pressure to reduce their VAP rates, yet a direct association between VAP rates and quality of care or outcomes has not been demonstrated," he remarked.

"VAP rates ...are remarkably variable," Dr. Michetti said. "It is not appropriate to measure all trauma centers against a single benchmark, nor does an actual benchmark appear to exist at this point." Comparing VAP rates between different trauma centers is "like comparing apples and oranges," he said.

The study looked at VAP rates at 47 level I and II trauma centers for 2008 and 2009 with an average of 3,000 trauma evaluations a year. The average VAP rate for the study group was 17.2/1,000 ventilator days, compared with 8.1/1,000 for NHSN data. "In fact, the 90th-percentile rate for NHSN was still below the mean rate from our study," Dr. Michetti said. Across all 47 centers in the study, VAP rates ranged from a low of 1.8/1,000 ventilator days to a high of 57.6/1,000 ventilator days.

The case mix at the trauma centers did not auger well for lower VAP rates, as 88% of the cases were blunt trauma, Dr. Michetti noted. "VAP rates are generally higher for blunt-trauma patients, at about 17/1,000 ventilator days, compared with penetrating trauma at 11/1,000," he said.

Most other variables among the centers in the study – such as having a closed or open ICU, or using a bacteriologic vs. a clinical strategy to diagnose VAP – showed little impact on the pneumonia rates. VAP rates did not correlate with the size or level of trauma center, injury severity or type of ICU, he said.

Among the problems he noted with the NHSN data on VAP rates are the lack of source hospital identification, population risk, or injury severity stratification. "In addition, the NHSN rates are substantially lower than other published rates among trauma patients," he said.

However, the investigators did isolate a few variables that may influence VAP rates: Among centers where the trauma service alone made the diagnosis, the average VAP rate was 27.5/1,000 ventilator days. When the infection control, quality, or epidemiology department made the call, the average VAP rate was 11.9/1,000 days. Centers that excluded patients also had rates about 30% lower than those that did not. This variability raises questions about using VAP as a quality measure, Dr. Michetti said. "Before we take that leap, diagnostic and reporting standards are necessary."

The heightened attention on VAP as a quality measure for critical care is having other implications, he said. "As pressure to reduce VAP rates grows, an increasing number of patients are being labeled as having ventilator-associated tracheobronchitis or excluded for reasons such as aspiration," he said.

Discussant Dr. Karen J. Brasel of the Medical College of Wisconsin in, Milwaukee, acknowledged the need for the study, but raised the question: "Are the benchmarks the problem, or are we the problem?"

"I think the answer is yes, both," Dr. Michetti said. "I’m not sure that an adequate benchmark exists probably because no representative sample of trauma centers has been done to set that benchmark." He noted that the CDC’s Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee does not recommend reporting of VAP, which argues against using that as a benchmark. Meanwhile, across individual centers no reporting standards exist, "so centers can’t agree on what is VAP," Dr. Michetti said.

Dr. Michetti had no disclosures, and the study received no outside funding.

CHICAGO – Payers are relying ever more on tying physician and hospital payments to quality measures, but what happens if the benchmarks they use vary among institutions or are flawed? Such may be the case with ventilator-associated pneumonia and large trauma centers, as a recent study shows VAP rates at such facilities exceed national benchmarks, which some say are inadequate for comparison.

Dr. Christopher P. Michetti of Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va., presented a retrospective study designed to determine VAP rates at major trauma centers and to lay groundwork for more accurate benchmarking that relies less on National Health Safety Network data, he said. He spoke at the annual meeting of the American Association for Surgery in Trauma. The study was performed through the AAST Multi-Institutional Trials Committee.

"Hospitals are under pressure to reduce their VAP rates, yet a direct association between VAP rates and quality of care or outcomes has not been demonstrated," he remarked.

"VAP rates ...are remarkably variable," Dr. Michetti said. "It is not appropriate to measure all trauma centers against a single benchmark, nor does an actual benchmark appear to exist at this point." Comparing VAP rates between different trauma centers is "like comparing apples and oranges," he said.

The study looked at VAP rates at 47 level I and II trauma centers for 2008 and 2009 with an average of 3,000 trauma evaluations a year. The average VAP rate for the study group was 17.2/1,000 ventilator days, compared with 8.1/1,000 for NHSN data. "In fact, the 90th-percentile rate for NHSN was still below the mean rate from our study," Dr. Michetti said. Across all 47 centers in the study, VAP rates ranged from a low of 1.8/1,000 ventilator days to a high of 57.6/1,000 ventilator days.

The case mix at the trauma centers did not auger well for lower VAP rates, as 88% of the cases were blunt trauma, Dr. Michetti noted. "VAP rates are generally higher for blunt-trauma patients, at about 17/1,000 ventilator days, compared with penetrating trauma at 11/1,000," he said.

Most other variables among the centers in the study – such as having a closed or open ICU, or using a bacteriologic vs. a clinical strategy to diagnose VAP – showed little impact on the pneumonia rates. VAP rates did not correlate with the size or level of trauma center, injury severity or type of ICU, he said.

Among the problems he noted with the NHSN data on VAP rates are the lack of source hospital identification, population risk, or injury severity stratification. "In addition, the NHSN rates are substantially lower than other published rates among trauma patients," he said.

However, the investigators did isolate a few variables that may influence VAP rates: Among centers where the trauma service alone made the diagnosis, the average VAP rate was 27.5/1,000 ventilator days. When the infection control, quality, or epidemiology department made the call, the average VAP rate was 11.9/1,000 days. Centers that excluded patients also had rates about 30% lower than those that did not. This variability raises questions about using VAP as a quality measure, Dr. Michetti said. "Before we take that leap, diagnostic and reporting standards are necessary."

The heightened attention on VAP as a quality measure for critical care is having other implications, he said. "As pressure to reduce VAP rates grows, an increasing number of patients are being labeled as having ventilator-associated tracheobronchitis or excluded for reasons such as aspiration," he said.

Discussant Dr. Karen J. Brasel of the Medical College of Wisconsin in, Milwaukee, acknowledged the need for the study, but raised the question: "Are the benchmarks the problem, or are we the problem?"

"I think the answer is yes, both," Dr. Michetti said. "I’m not sure that an adequate benchmark exists probably because no representative sample of trauma centers has been done to set that benchmark." He noted that the CDC’s Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee does not recommend reporting of VAP, which argues against using that as a benchmark. Meanwhile, across individual centers no reporting standards exist, "so centers can’t agree on what is VAP," Dr. Michetti said.

Dr. Michetti had no disclosures, and the study received no outside funding.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE SURGERY OF TRAUMA

Major Finding: AAST study shows major trauma centers have higher VAP rates than do national benchmark data.

Data Source: Retrospective analysis of trauma admissions at 47 Level I and II centers sponsored by AAST Multi-Institutional Trials Committee

Disclosures: Dr. Michetti had no disclosures and the study received no outside funding.

r-TEG Test Helps Pinpoint Likelihood of PE

CHICAGO – Performing rapid thromboelastography on admission can help trauma surgeons determine which patients are at greatest risk of developing pulmonary embolism, judging by results of a study of more than 8,000 patients.

The incidence of pulmonary embolism (PE), although still below 0.5%, has more than doubled in recent years, according to a recent report using data from the National Trauma Data Bank (Ann. Surg. 2011 Aug. 24 [E-pub ahead of print]).

"Despite this increasing knowledge of risk factors, despite increasing chemoprophylaxis – we’re getting more aggressive with head injuries in starting enoxaparin and heparin, and more aggressive with our spine and solid organ injuries – despite all this, the incidence of PE is increasing," Dr. Bryan A. Cotton said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

To learn whether rapid thromboelastography (r-TEG), using a maximum amplitude (mA) greater than 65 mm, could identify patients at risk of developing PE during their hospital stay, Dr. Cotton and his colleagues at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston evaluated the use of r-TEG upon admission to the trauma bay for 8,330 total trauma patients over an 18-month period.

"Recent data from multiple institutions have shown an increase in vascular complications following these states if the mA values and certain other portions of TEG values are elevated," Dr. Cotton said. Besides PE and venous thromboembolism (VTE), complications including stroke and postoperative MI have been shown to increase with postoperative and postinjury r-TEG values, he added.

In the Houston study, r-TEG was obtained on 2,070 consecutive trauma patients. Of those, 2.5% went on to develop PE. These patients tended to be older and were more likely to be white and more severely injured than the other patients, and to have only blunt injuries.

"We found the admission mA, which is the highest amplitude of the clot, was associated with risk of developing PE during hospital stay," Dr. Cotton said.

The median time to development of PE was 6 days (duration, 2-31 days), he noted. The investigators also analyzed other factors, and when controlling for male sex, Injury Severity Score, and age, they found that an individual with an mA greater than 65 mm at the time of admission had a 3.5-fold greater odds of developing PE during the hospital stay, Dr. Cotton said. When they raised the threshold to an mA of 72 mm or higher, the risk profile increased sixfold, he said.

"An mA of 65 [mm] or greater is just as good as traditionally noted high-risk factors," Dr. Cotton said. "These include pelvic factures and lower extremity spine and head injuries. When mA is greater than 72 [mm], it exceeds or equals the odds ratio for very-high-risk factors such as prolonged ventilation and venous injuries."