User login

American Heart Association (AHA): Scientific Sessions 2013

Advanced pacing slows AF progression in bradycardia

DALLAS – Enhanced pacemaker technology sharply reduced progression of nonpermanent atrial fibrillation to permanent AF in patients with bradycardia and sinus node disease in the large international, randomized MINERVA trial.

In the MINERVA (Minimize Right Ventricular Pacing to Prevent Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure) study, the use of dual-chamber pacemakers containing features for atrial preventive pacing and atrial antitachycardia pacing, called DDDRPs, plus managed ventricular pacing (MVP) resulted in a 61% reduction in the incidence of permanent AF during 2 years of prospective follow-up, compared with conventional dual-chamber pacing, Dr. Giuseppe Boriani reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

In addition, patients in the enhanced-pacing group experienced a 52% reduction in AF-related hospitalizations and emergency department visits, as well as a 49% decrease in atrial cardioversions relative to controls, added Dr. Boriani of the University of Bologna (Italy).

"This is the first study to show that using these enhanced pacing features in combination not only delays the AF disease progression, but also has an impact on health care utilization," he noted. "With this solid evidence of beneficial results, I think the practice guidelines probably should be updated to state this type of device should be implanted for sinus node disease in patients with a history of atrial fibrillation."

MINERVA included 1,166 patients at 63 European, Asian, and Middle Eastern centers; all had bradycardia, sinus node disease, and a history of nonpermanent AF. They received a commercially available Medtronic dual-chamber pacemaker that was randomized single-blind to operate using both the DDDRP and MVP features, the MVP alone, or conventional dual-chamber pacing with neither enhanced feature.

At 2 years, the primary composite endpoint of death, cardiovascular hospitalization, or permanent AF had occurred in 19.8% of the DDDRP plus MVP group. That amounted to a significant 26% reduction in the endpoint compared with the 26.5% rate in the controls on standard dual-chamber pacing. The 21.4% rate in patients whose device used only the MVP algorithm was not significantly different from the rate in controls.

Most strikingly, the 2-year incidence of progression to permanent AF was 3.8% in patients with the enhanced pacing features, compared with 9.2% in those assigned to conventional dual-chamber pacing, for a 61% relative risk reduction. This means 20 patients would need to be treated for 2 years with a pacemaker utilizing the advanced pacing features in order to prevent one additional case of permanent AF.

In addition, patients whose pacemakers utilized rate response and antitachycardia pacing plus MVP reported better quality of life and less fatigue than did those in the other two study arms.

Dr. Boriani estimated that of the 170,000 patients each year in the United States who undergo pacemaker implantation for bradycardia, roughly 25,000 have sinus node disease and a history of AF and would thus now be considered strong candidates for the enhanced pacing features.

Discussant Dr. Anthony Tang explained that it has been known for years that pacemaker algorithms designed to increase the atrial pacing rate above the intrinsic sinus rate can prevent events that trigger AF. The problem has been that this atrial pacing can have the side effect of also increasing ventricular pacing, which can initiate AF, thus canceling the advantage of the atrial preventive pacing. The MVP algorithm decreases this unnecessary pacing in the right ventricle, with the resultant benefits seen in MINERVA.

In his view, the enhanced pacing features used in MINERVA represent a very good option for patients with severe sinus node dysfunction but preserved atrioventricular node conduction, that is, patients who need atrial pacing for long sinus pauses but don’t need much ventricular pacing.

In contrast, for patients with an indication for a pacemaker but who only occasionally need pacing, such as those with a rare sinus pause or occasional AV block, a simple single-chamber ventricular pacemaker will generally do. For those with second- or third-degree AV block with left ventricular dysfunction and who need both atrial and ventricular pacing most of the time, a cardiac resynchronization therapy device plus either a pacemaker or a defibrillator is appropriate, depending upon the severity of the left ventricular dysfunction, according to Dr. Tang, professor of medicine and chair of cardiovascular population health at Western University, London, Ont.

Discussant Dr. Timothy J. Gardner wasn’t bowled over by the number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 20 in MINERVA.

"That seems a very modest impact. I wonder from a health care/societal benefit standpoint whether an NNT of 20 for a more complex and expensive technology is appropriate," challenged Dr. Gardner, a heart surgeon and medical director of the Christiana Care Center for Heart and Vascular Health in Newark, Del.

Dr. Boriani replied that the benefits seen with advanced pacing in this 2-year study will only become more pronounced with longer follow-up.

"Permanent atrial fibrillation is the later stage of irreversible AF, when the arrhythmia becomes untreatable. And it is a marker for adverse events, including heart failure, stroke, and death," he said.

The MINERVA trial was sponsored by Medtronic, which markets the proprietary enhanced pacing technology. Dr. Boriani reported having no relevant financial interests.

DALLAS – Enhanced pacemaker technology sharply reduced progression of nonpermanent atrial fibrillation to permanent AF in patients with bradycardia and sinus node disease in the large international, randomized MINERVA trial.

In the MINERVA (Minimize Right Ventricular Pacing to Prevent Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure) study, the use of dual-chamber pacemakers containing features for atrial preventive pacing and atrial antitachycardia pacing, called DDDRPs, plus managed ventricular pacing (MVP) resulted in a 61% reduction in the incidence of permanent AF during 2 years of prospective follow-up, compared with conventional dual-chamber pacing, Dr. Giuseppe Boriani reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

In addition, patients in the enhanced-pacing group experienced a 52% reduction in AF-related hospitalizations and emergency department visits, as well as a 49% decrease in atrial cardioversions relative to controls, added Dr. Boriani of the University of Bologna (Italy).

"This is the first study to show that using these enhanced pacing features in combination not only delays the AF disease progression, but also has an impact on health care utilization," he noted. "With this solid evidence of beneficial results, I think the practice guidelines probably should be updated to state this type of device should be implanted for sinus node disease in patients with a history of atrial fibrillation."

MINERVA included 1,166 patients at 63 European, Asian, and Middle Eastern centers; all had bradycardia, sinus node disease, and a history of nonpermanent AF. They received a commercially available Medtronic dual-chamber pacemaker that was randomized single-blind to operate using both the DDDRP and MVP features, the MVP alone, or conventional dual-chamber pacing with neither enhanced feature.

At 2 years, the primary composite endpoint of death, cardiovascular hospitalization, or permanent AF had occurred in 19.8% of the DDDRP plus MVP group. That amounted to a significant 26% reduction in the endpoint compared with the 26.5% rate in the controls on standard dual-chamber pacing. The 21.4% rate in patients whose device used only the MVP algorithm was not significantly different from the rate in controls.

Most strikingly, the 2-year incidence of progression to permanent AF was 3.8% in patients with the enhanced pacing features, compared with 9.2% in those assigned to conventional dual-chamber pacing, for a 61% relative risk reduction. This means 20 patients would need to be treated for 2 years with a pacemaker utilizing the advanced pacing features in order to prevent one additional case of permanent AF.

In addition, patients whose pacemakers utilized rate response and antitachycardia pacing plus MVP reported better quality of life and less fatigue than did those in the other two study arms.

Dr. Boriani estimated that of the 170,000 patients each year in the United States who undergo pacemaker implantation for bradycardia, roughly 25,000 have sinus node disease and a history of AF and would thus now be considered strong candidates for the enhanced pacing features.

Discussant Dr. Anthony Tang explained that it has been known for years that pacemaker algorithms designed to increase the atrial pacing rate above the intrinsic sinus rate can prevent events that trigger AF. The problem has been that this atrial pacing can have the side effect of also increasing ventricular pacing, which can initiate AF, thus canceling the advantage of the atrial preventive pacing. The MVP algorithm decreases this unnecessary pacing in the right ventricle, with the resultant benefits seen in MINERVA.

In his view, the enhanced pacing features used in MINERVA represent a very good option for patients with severe sinus node dysfunction but preserved atrioventricular node conduction, that is, patients who need atrial pacing for long sinus pauses but don’t need much ventricular pacing.

In contrast, for patients with an indication for a pacemaker but who only occasionally need pacing, such as those with a rare sinus pause or occasional AV block, a simple single-chamber ventricular pacemaker will generally do. For those with second- or third-degree AV block with left ventricular dysfunction and who need both atrial and ventricular pacing most of the time, a cardiac resynchronization therapy device plus either a pacemaker or a defibrillator is appropriate, depending upon the severity of the left ventricular dysfunction, according to Dr. Tang, professor of medicine and chair of cardiovascular population health at Western University, London, Ont.

Discussant Dr. Timothy J. Gardner wasn’t bowled over by the number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 20 in MINERVA.

"That seems a very modest impact. I wonder from a health care/societal benefit standpoint whether an NNT of 20 for a more complex and expensive technology is appropriate," challenged Dr. Gardner, a heart surgeon and medical director of the Christiana Care Center for Heart and Vascular Health in Newark, Del.

Dr. Boriani replied that the benefits seen with advanced pacing in this 2-year study will only become more pronounced with longer follow-up.

"Permanent atrial fibrillation is the later stage of irreversible AF, when the arrhythmia becomes untreatable. And it is a marker for adverse events, including heart failure, stroke, and death," he said.

The MINERVA trial was sponsored by Medtronic, which markets the proprietary enhanced pacing technology. Dr. Boriani reported having no relevant financial interests.

DALLAS – Enhanced pacemaker technology sharply reduced progression of nonpermanent atrial fibrillation to permanent AF in patients with bradycardia and sinus node disease in the large international, randomized MINERVA trial.

In the MINERVA (Minimize Right Ventricular Pacing to Prevent Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure) study, the use of dual-chamber pacemakers containing features for atrial preventive pacing and atrial antitachycardia pacing, called DDDRPs, plus managed ventricular pacing (MVP) resulted in a 61% reduction in the incidence of permanent AF during 2 years of prospective follow-up, compared with conventional dual-chamber pacing, Dr. Giuseppe Boriani reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

In addition, patients in the enhanced-pacing group experienced a 52% reduction in AF-related hospitalizations and emergency department visits, as well as a 49% decrease in atrial cardioversions relative to controls, added Dr. Boriani of the University of Bologna (Italy).

"This is the first study to show that using these enhanced pacing features in combination not only delays the AF disease progression, but also has an impact on health care utilization," he noted. "With this solid evidence of beneficial results, I think the practice guidelines probably should be updated to state this type of device should be implanted for sinus node disease in patients with a history of atrial fibrillation."

MINERVA included 1,166 patients at 63 European, Asian, and Middle Eastern centers; all had bradycardia, sinus node disease, and a history of nonpermanent AF. They received a commercially available Medtronic dual-chamber pacemaker that was randomized single-blind to operate using both the DDDRP and MVP features, the MVP alone, or conventional dual-chamber pacing with neither enhanced feature.

At 2 years, the primary composite endpoint of death, cardiovascular hospitalization, or permanent AF had occurred in 19.8% of the DDDRP plus MVP group. That amounted to a significant 26% reduction in the endpoint compared with the 26.5% rate in the controls on standard dual-chamber pacing. The 21.4% rate in patients whose device used only the MVP algorithm was not significantly different from the rate in controls.

Most strikingly, the 2-year incidence of progression to permanent AF was 3.8% in patients with the enhanced pacing features, compared with 9.2% in those assigned to conventional dual-chamber pacing, for a 61% relative risk reduction. This means 20 patients would need to be treated for 2 years with a pacemaker utilizing the advanced pacing features in order to prevent one additional case of permanent AF.

In addition, patients whose pacemakers utilized rate response and antitachycardia pacing plus MVP reported better quality of life and less fatigue than did those in the other two study arms.

Dr. Boriani estimated that of the 170,000 patients each year in the United States who undergo pacemaker implantation for bradycardia, roughly 25,000 have sinus node disease and a history of AF and would thus now be considered strong candidates for the enhanced pacing features.

Discussant Dr. Anthony Tang explained that it has been known for years that pacemaker algorithms designed to increase the atrial pacing rate above the intrinsic sinus rate can prevent events that trigger AF. The problem has been that this atrial pacing can have the side effect of also increasing ventricular pacing, which can initiate AF, thus canceling the advantage of the atrial preventive pacing. The MVP algorithm decreases this unnecessary pacing in the right ventricle, with the resultant benefits seen in MINERVA.

In his view, the enhanced pacing features used in MINERVA represent a very good option for patients with severe sinus node dysfunction but preserved atrioventricular node conduction, that is, patients who need atrial pacing for long sinus pauses but don’t need much ventricular pacing.

In contrast, for patients with an indication for a pacemaker but who only occasionally need pacing, such as those with a rare sinus pause or occasional AV block, a simple single-chamber ventricular pacemaker will generally do. For those with second- or third-degree AV block with left ventricular dysfunction and who need both atrial and ventricular pacing most of the time, a cardiac resynchronization therapy device plus either a pacemaker or a defibrillator is appropriate, depending upon the severity of the left ventricular dysfunction, according to Dr. Tang, professor of medicine and chair of cardiovascular population health at Western University, London, Ont.

Discussant Dr. Timothy J. Gardner wasn’t bowled over by the number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 20 in MINERVA.

"That seems a very modest impact. I wonder from a health care/societal benefit standpoint whether an NNT of 20 for a more complex and expensive technology is appropriate," challenged Dr. Gardner, a heart surgeon and medical director of the Christiana Care Center for Heart and Vascular Health in Newark, Del.

Dr. Boriani replied that the benefits seen with advanced pacing in this 2-year study will only become more pronounced with longer follow-up.

"Permanent atrial fibrillation is the later stage of irreversible AF, when the arrhythmia becomes untreatable. And it is a marker for adverse events, including heart failure, stroke, and death," he said.

The MINERVA trial was sponsored by Medtronic, which markets the proprietary enhanced pacing technology. Dr. Boriani reported having no relevant financial interests.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Major finding: Patients with bradycardia, sinus node disease, and a history of atrial fibrillation who were implanted with a dual-chamber pacemaker utilizing enhanced pacing features showed a 61% reduction in progression to permanent AF over 2 years, compared with those randomized to conventional dual-chamber pacing.

Data source: The MINERVA trial, a single-blind, randomized, international, prospective, 2-year trial conducted in 1,166 patients.

Disclosures: The MINERVA trial was sponsored by Medtronic, which markets the proprietary enhanced pacing technology. Dr. Boriani reported having no relevant financial interests.

Substrate ablation shows no advantage for A fib

DALLAS – A substrate-based ablation strategy failed to show an efficacy advantage over conventional circumferential pulmonary vein isolation for eliminating persistent or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in a multicenter randomized trial with 232 patients.

High-frequency source ablation (HFSA), a strategy that targets rotors in the atrial substrate responsible for maintaining fibrillation episodes, did not reach statistical significance for noninferiority compared with circumferential pulmonary vein isolation (CPVI) after 6 months in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF), the study’s primary endpoint, Dr. Felipe Atienza said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In enrolled patients with persistent atrial fibrillation, adding HFSA to CPVI "offered no incremental value with a trend for an increase in complications," after 6 months in a study designed to test superiority, said Dr. Atienza, an electrophysiologist at Gregorio Marañón University Hospital in Madrid.

But a ray of promise came from 1-year follow-up of the paroxysmal atrial fibrillation patients, half of the patients enrolled in the study. (The other patients had persistent atrial fibrillation.) At that time, HFSA treatment achieved statistically significant noninferiority compared with CPVI for freedom from atrial fibrillation and freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmia, with a significantly lower rate of serious adverse events.

Although the results mean that pulmonary vein isolation remains the standard of care for treating atrial fibrillation patients who fail to respond to drug treatment, substrate-based ablation showed enough potential in the study to remain a viable candidate for further testing, experts said.

"In this trial, HFSA did not improve outcomes in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF, but the fact that HFSA treatment was equivalent to CPVI in patients with paroxysmal AF keeps the AF substrate and trigger argument alive," commented Dr. Mark S. Link, professor and codirector of the New England Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at Tufts Medical Center Boston, and designated discussant for the report.

"The way to go is to run further investigations like this to try to find and eliminate the substrates of atrial fibrillation instead of ablating everywhere," said Dr. Atienza.

The RADAR-AF (Radiofrequency Ablation of Drivers of Atrial Fibrillation) trial enrolled 115 patients with paroxysmal AF and 117 patients with persistent AF at 11 hospitals in Spain. The researchers randomized the patients with paroxysmal AF to treatment with either HFSA or CPVI; they randomized patients with persistent AF to treatment with both HFSA and CPVI or to CPVI alone. They used software developed by St. Jude Medical to identify the sites for HFSA.

The study’s primary endpoint was freedom from AF while off of antiarrhythmic drugs at 6 months. In the paroxysmal patients, this endpoint was reached by 73% of patients treated with HFSA and 83% treated with CPVI, which failed to meet the prespecified criteria for noninferiority. However, after 1 year the rate of freedom from AF was 69% in patients in both groups, and the rate of freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmia in both groups was 59%, rates that met the criteria for noninferiority. In addition, after 1 year the cumulative rate of serious adverse events was 9% in the HFSA group and 24% in the CPVI group, a statistically significant difference.

Among the patients with persistent atrial fibrillation, the rate of freedom from AF after 6 months was 61% in patients treated with both techniques and 60% in those treated with CPVI alone, which failed to show superiority. Efficacy rates were also similar in both arms after 1 year, and the rate of serious adverse events was 24% in patients treated with both HFSA and CPVI, compared with 10% among those treated by CPVI only.

The RADAR-AF trial was sponsored by St. Jude Medical, which developed the rotor-mapping software used for substrate ablation in the study. Dr. Atienza and Dr. Link said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The hypothesis underlying the RADAR-AF trial is that while atrial fibrillation is initiated by focal triggers, it is maintained in the atrial substrate, specifically by rotors in the substrate. The concept is that if you can ablate the substrate correctly, it will prevent episodes of sustained atrial fibrillation and move us beyond the ceiling we currently have with pulmonary vein isolation, which has about a 70% success rate.

|

Mitchel L. Zoler/IMNG Medical Media

|

The results from RADAR-AF do not kill the notion that the substrate is important, especially because in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation just ablating the substrate did as well after 1 year as standard pulmonary vein isolation.

The findings also indicate that the technique tested for identifying rotors in the substrate is inadequate, and we need a better way to do this. Several ongoing clinical trials are looking at this. We just do not have adequate tools right now to know where to ablate the substrate.

The most important thing is that the RADAR-AF results produced a signal that the substrate is important.

Dr. Mark S. Link is professor of medicine and codirector of the New England Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. He made these comments as the designated discussant for the report and during a press conference. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

RADAR-AF, Radiofrequency Ablation of Drivers of Atrial Fibrillation trial,

The hypothesis underlying the RADAR-AF trial is that while atrial fibrillation is initiated by focal triggers, it is maintained in the atrial substrate, specifically by rotors in the substrate. The concept is that if you can ablate the substrate correctly, it will prevent episodes of sustained atrial fibrillation and move us beyond the ceiling we currently have with pulmonary vein isolation, which has about a 70% success rate.

|

Mitchel L. Zoler/IMNG Medical Media

|

The results from RADAR-AF do not kill the notion that the substrate is important, especially because in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation just ablating the substrate did as well after 1 year as standard pulmonary vein isolation.

The findings also indicate that the technique tested for identifying rotors in the substrate is inadequate, and we need a better way to do this. Several ongoing clinical trials are looking at this. We just do not have adequate tools right now to know where to ablate the substrate.

The most important thing is that the RADAR-AF results produced a signal that the substrate is important.

Dr. Mark S. Link is professor of medicine and codirector of the New England Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. He made these comments as the designated discussant for the report and during a press conference. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

The hypothesis underlying the RADAR-AF trial is that while atrial fibrillation is initiated by focal triggers, it is maintained in the atrial substrate, specifically by rotors in the substrate. The concept is that if you can ablate the substrate correctly, it will prevent episodes of sustained atrial fibrillation and move us beyond the ceiling we currently have with pulmonary vein isolation, which has about a 70% success rate.

|

Mitchel L. Zoler/IMNG Medical Media

|

The results from RADAR-AF do not kill the notion that the substrate is important, especially because in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation just ablating the substrate did as well after 1 year as standard pulmonary vein isolation.

The findings also indicate that the technique tested for identifying rotors in the substrate is inadequate, and we need a better way to do this. Several ongoing clinical trials are looking at this. We just do not have adequate tools right now to know where to ablate the substrate.

The most important thing is that the RADAR-AF results produced a signal that the substrate is important.

Dr. Mark S. Link is professor of medicine and codirector of the New England Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. He made these comments as the designated discussant for the report and during a press conference. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

DALLAS – A substrate-based ablation strategy failed to show an efficacy advantage over conventional circumferential pulmonary vein isolation for eliminating persistent or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in a multicenter randomized trial with 232 patients.

High-frequency source ablation (HFSA), a strategy that targets rotors in the atrial substrate responsible for maintaining fibrillation episodes, did not reach statistical significance for noninferiority compared with circumferential pulmonary vein isolation (CPVI) after 6 months in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF), the study’s primary endpoint, Dr. Felipe Atienza said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In enrolled patients with persistent atrial fibrillation, adding HFSA to CPVI "offered no incremental value with a trend for an increase in complications," after 6 months in a study designed to test superiority, said Dr. Atienza, an electrophysiologist at Gregorio Marañón University Hospital in Madrid.

But a ray of promise came from 1-year follow-up of the paroxysmal atrial fibrillation patients, half of the patients enrolled in the study. (The other patients had persistent atrial fibrillation.) At that time, HFSA treatment achieved statistically significant noninferiority compared with CPVI for freedom from atrial fibrillation and freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmia, with a significantly lower rate of serious adverse events.

Although the results mean that pulmonary vein isolation remains the standard of care for treating atrial fibrillation patients who fail to respond to drug treatment, substrate-based ablation showed enough potential in the study to remain a viable candidate for further testing, experts said.

"In this trial, HFSA did not improve outcomes in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF, but the fact that HFSA treatment was equivalent to CPVI in patients with paroxysmal AF keeps the AF substrate and trigger argument alive," commented Dr. Mark S. Link, professor and codirector of the New England Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at Tufts Medical Center Boston, and designated discussant for the report.

"The way to go is to run further investigations like this to try to find and eliminate the substrates of atrial fibrillation instead of ablating everywhere," said Dr. Atienza.

The RADAR-AF (Radiofrequency Ablation of Drivers of Atrial Fibrillation) trial enrolled 115 patients with paroxysmal AF and 117 patients with persistent AF at 11 hospitals in Spain. The researchers randomized the patients with paroxysmal AF to treatment with either HFSA or CPVI; they randomized patients with persistent AF to treatment with both HFSA and CPVI or to CPVI alone. They used software developed by St. Jude Medical to identify the sites for HFSA.

The study’s primary endpoint was freedom from AF while off of antiarrhythmic drugs at 6 months. In the paroxysmal patients, this endpoint was reached by 73% of patients treated with HFSA and 83% treated with CPVI, which failed to meet the prespecified criteria for noninferiority. However, after 1 year the rate of freedom from AF was 69% in patients in both groups, and the rate of freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmia in both groups was 59%, rates that met the criteria for noninferiority. In addition, after 1 year the cumulative rate of serious adverse events was 9% in the HFSA group and 24% in the CPVI group, a statistically significant difference.

Among the patients with persistent atrial fibrillation, the rate of freedom from AF after 6 months was 61% in patients treated with both techniques and 60% in those treated with CPVI alone, which failed to show superiority. Efficacy rates were also similar in both arms after 1 year, and the rate of serious adverse events was 24% in patients treated with both HFSA and CPVI, compared with 10% among those treated by CPVI only.

The RADAR-AF trial was sponsored by St. Jude Medical, which developed the rotor-mapping software used for substrate ablation in the study. Dr. Atienza and Dr. Link said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

DALLAS – A substrate-based ablation strategy failed to show an efficacy advantage over conventional circumferential pulmonary vein isolation for eliminating persistent or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in a multicenter randomized trial with 232 patients.

High-frequency source ablation (HFSA), a strategy that targets rotors in the atrial substrate responsible for maintaining fibrillation episodes, did not reach statistical significance for noninferiority compared with circumferential pulmonary vein isolation (CPVI) after 6 months in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF), the study’s primary endpoint, Dr. Felipe Atienza said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In enrolled patients with persistent atrial fibrillation, adding HFSA to CPVI "offered no incremental value with a trend for an increase in complications," after 6 months in a study designed to test superiority, said Dr. Atienza, an electrophysiologist at Gregorio Marañón University Hospital in Madrid.

But a ray of promise came from 1-year follow-up of the paroxysmal atrial fibrillation patients, half of the patients enrolled in the study. (The other patients had persistent atrial fibrillation.) At that time, HFSA treatment achieved statistically significant noninferiority compared with CPVI for freedom from atrial fibrillation and freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmia, with a significantly lower rate of serious adverse events.

Although the results mean that pulmonary vein isolation remains the standard of care for treating atrial fibrillation patients who fail to respond to drug treatment, substrate-based ablation showed enough potential in the study to remain a viable candidate for further testing, experts said.

"In this trial, HFSA did not improve outcomes in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF, but the fact that HFSA treatment was equivalent to CPVI in patients with paroxysmal AF keeps the AF substrate and trigger argument alive," commented Dr. Mark S. Link, professor and codirector of the New England Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at Tufts Medical Center Boston, and designated discussant for the report.

"The way to go is to run further investigations like this to try to find and eliminate the substrates of atrial fibrillation instead of ablating everywhere," said Dr. Atienza.

The RADAR-AF (Radiofrequency Ablation of Drivers of Atrial Fibrillation) trial enrolled 115 patients with paroxysmal AF and 117 patients with persistent AF at 11 hospitals in Spain. The researchers randomized the patients with paroxysmal AF to treatment with either HFSA or CPVI; they randomized patients with persistent AF to treatment with both HFSA and CPVI or to CPVI alone. They used software developed by St. Jude Medical to identify the sites for HFSA.

The study’s primary endpoint was freedom from AF while off of antiarrhythmic drugs at 6 months. In the paroxysmal patients, this endpoint was reached by 73% of patients treated with HFSA and 83% treated with CPVI, which failed to meet the prespecified criteria for noninferiority. However, after 1 year the rate of freedom from AF was 69% in patients in both groups, and the rate of freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmia in both groups was 59%, rates that met the criteria for noninferiority. In addition, after 1 year the cumulative rate of serious adverse events was 9% in the HFSA group and 24% in the CPVI group, a statistically significant difference.

Among the patients with persistent atrial fibrillation, the rate of freedom from AF after 6 months was 61% in patients treated with both techniques and 60% in those treated with CPVI alone, which failed to show superiority. Efficacy rates were also similar in both arms after 1 year, and the rate of serious adverse events was 24% in patients treated with both HFSA and CPVI, compared with 10% among those treated by CPVI only.

The RADAR-AF trial was sponsored by St. Jude Medical, which developed the rotor-mapping software used for substrate ablation in the study. Dr. Atienza and Dr. Link said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

RADAR-AF, Radiofrequency Ablation of Drivers of Atrial Fibrillation trial,

RADAR-AF, Radiofrequency Ablation of Drivers of Atrial Fibrillation trial,

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Major finding: Substrate ablation failed to show efficacy compared with conventional pulmonary vein isolation for patients with atrial fibrillation.

Data source: The RADAR-AF trial, which enrolled 232 patients with paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation at 11 Spanish Hospitals.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by St. Jude Medical, which developed the rotor-mapping software used for substrate ablation in the study. Dr. Atienza and Dr. Link said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

TOPCAT: Spironolactone cuts hospitalizations for diastolic heart failure

DALLAS – Spironolactone did not hit a home run in the large international "treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist" (TOPCAT) trial, but it did knock out a solid single in the form of significantly reduced hospitalizations for this extremely common, chronic, high morbidity/mortality condition.

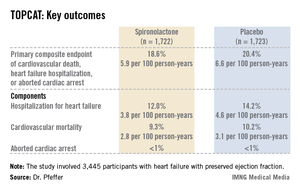

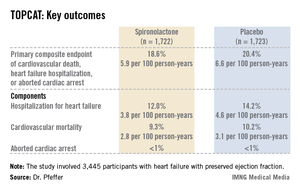

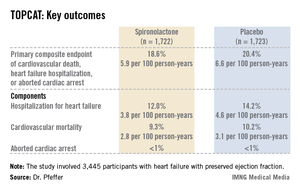

It was this positive result for an important prespecified secondary outcome that enabled TOPCAT to avoid becoming roadkill. Technically, TOPCAT was a negative clinical trial in that spironolactone did not significantly outperform placebo on the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular mortality, heart failure hospitalization, or aborted cardiac arrest.

Yet that negative primary outcome was controversial: The aldosterone antagonist actually showed a significant positive result for the composite endpoint in North and South American participants, yet the results were resoundingly negative – and also considerably out of whack with the characteristic arc of progressive heart failure – among the nearly one-half of TOPCAT participants in Russia and the Republic of Georgia.

"What happened in Russia and Georgia we just don’t understand," Dr. Bertram Pitt, TOPCAT steering committee chair, said in an interview, shaking his head. "The event rate with placebo in Eastern Europe was so low it’s not compatible with anything we know about heart failure. The signs and symptoms of HFpEF [heart failure with preserved ejection fraction] are nonspecific; they can be due to obesity, lung disease, and other things. Clearly there are some people getting into the major trials of HFpEF that probably don’t have it."

TOPCAT was a randomized, double-blind clinical trial comprising 3,445 participants with symptomatic HFpEF at 250 sites in the United States and five other countries. They were randomized to spironolactone or placebo and followed prospectively for a mean of 3.3 years. The starting dose of the aldosterone antagonist was 15 mg/day, with a target of 30 mg/day. The drug could be titrated within the range of 15-45 mg/day. Eight months into the trial, the mean daily dose was 25 mg.

Presenting the TOPCAT results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions, Dr. Marc A. Pfeffer noted that the primary composite endpoint occurred in 20.4% of placebo-treated controls and 18.6% on spironolactone, a statistically nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 17% reduction in the rate of hospitalization for HFpEF in the spironolactone group relative to controls was significant (P = .04). Moreover, the spironolactone-treated patients had a collective 394 HFpEF hospitalizations, markedly fewer than the 475 in controls. This translated to a hospitalization for heart failure with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction occurring at a rate of 3.8 per 100 person-years in patients randomized to spironolactone, compared with the 4.6 per 100 person-years in placebo-treated controls.

Hyperkalemia in excess of 5.5 mmol/L occurred in 18.7% of the spironolactone group, twice the rate of controls (9.1%). And the incidence of a creatinine level more than double the upper limit of normal was 49% greater in the spironolactone group. That said, neither of these laboratory abnormalities resulted in any serious adverse consequences because investigators adjusted the dose in response, explained Dr. Pfeffer, professor of medicine at Harvard University, Boston.

He drew special attention to two points: The primary composite event rate in placebo-treated patients in the Americas was 31.8% consistent with what has been seen in other studies of HFpEF – compared to a mere 8.4% in Eastern Europe. And patients who qualified for TOPCAT on the basis of an elevated natriuretic peptide level had a primary endpoint rate of 15.9% with spironolactone, a highly significant 35% reduction compared with the 23.6% in controls, suggesting that an elevated baseline natriuretic peptide level may be a biomarker useful in identifying those HFpEF patients most likely to respond to an aldosterone antagonist.

Dr. Pfeffer said that because the pharmaceutical industry has zero interest in spironolactone and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), which sponsored TOPCAT, has finite resources, he doubts there will be any further large studies of the drug in HFpEF.

"One is going to have to make decisions based on this trial. I don’t see another trial behind us," the cardiologist said.

And while TOPCAT was flawed, he said it contains a compelling message for clinicians: "I think we have an important finding here. We’re very confident that with this generic medication, which costs pennies per day, we can reduce hospitalizations for heart failure, which are the major burden in patients with HFpEF."

Discussant Dr. Margaret M. Redfield was more cautious. While there was a sound rationale for studying spironolactone in HFpEF based upon its impressive benefits in systolic heart failure as shown in earlier landmark clinical trials, given that the drug didn’t result in a significant reduction in all-cause hospitalizations, she said she wants to see evidence of improved patient-centered outcomes, such as quality of life, before prescribing spironolactone for HFpEF.

"One has to worry that the problems with worsening renal function and hyperkalemia may be much more common in clinical practice than in the highly monitored environment of a clinical trial," added Dr. Redfield, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Other heart failure experts not involved in TOPCAT took a more positive view of the study.

Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, AHA spokesperson, said in an interview that HFpEF is probably even more common than systolic heart failure, and it is a disease for which physicians have had no proven-effective treatments.

"You can almost justifiably say, ‘Let’s just look at the Americas, where patients had event rates that are consistent with the disease we think we understand.’ And it looks like there’s a signal there. I think that there’s enough evidence in TOPCAT for the clinical pragmatist to be able to be comfortable that spironolactone is probably beneficial and can be given safely. If you are convinced you can give it safely in your own clinical scenario, I think you should use it," said Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Marco Metra, a cardiologist at the University of Brescia (Italy), said he interprets the TOPCAT results as an indication for prescribing spironolactone, at least in HFpEF patients with high natriuretic peptide levels or multiple heart failure hospitalizations.

Dr. Pitt, emeritus professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, emphasized that in prescribing spironolactone, whether for HFpEF or systolic heart failure, it’s obligatory to measure potassium and creatinine levels at baseline, when changing the dose, and at each routine follow-up visit, titrating in response to the results. Failure to do so is akin to prescribing warfarin for a patient with atrial fibrillation and then never measuring the INR (international normalized ratio) he said.

TOPCAT was sponsored by the National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Pfeffer and Dr. Pitt serve as consultants to numerous pharmaceutical companies that had no involvement in the trial.

DALLAS – Spironolactone did not hit a home run in the large international "treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist" (TOPCAT) trial, but it did knock out a solid single in the form of significantly reduced hospitalizations for this extremely common, chronic, high morbidity/mortality condition.

It was this positive result for an important prespecified secondary outcome that enabled TOPCAT to avoid becoming roadkill. Technically, TOPCAT was a negative clinical trial in that spironolactone did not significantly outperform placebo on the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular mortality, heart failure hospitalization, or aborted cardiac arrest.

Yet that negative primary outcome was controversial: The aldosterone antagonist actually showed a significant positive result for the composite endpoint in North and South American participants, yet the results were resoundingly negative – and also considerably out of whack with the characteristic arc of progressive heart failure – among the nearly one-half of TOPCAT participants in Russia and the Republic of Georgia.

"What happened in Russia and Georgia we just don’t understand," Dr. Bertram Pitt, TOPCAT steering committee chair, said in an interview, shaking his head. "The event rate with placebo in Eastern Europe was so low it’s not compatible with anything we know about heart failure. The signs and symptoms of HFpEF [heart failure with preserved ejection fraction] are nonspecific; they can be due to obesity, lung disease, and other things. Clearly there are some people getting into the major trials of HFpEF that probably don’t have it."

TOPCAT was a randomized, double-blind clinical trial comprising 3,445 participants with symptomatic HFpEF at 250 sites in the United States and five other countries. They were randomized to spironolactone or placebo and followed prospectively for a mean of 3.3 years. The starting dose of the aldosterone antagonist was 15 mg/day, with a target of 30 mg/day. The drug could be titrated within the range of 15-45 mg/day. Eight months into the trial, the mean daily dose was 25 mg.

Presenting the TOPCAT results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions, Dr. Marc A. Pfeffer noted that the primary composite endpoint occurred in 20.4% of placebo-treated controls and 18.6% on spironolactone, a statistically nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 17% reduction in the rate of hospitalization for HFpEF in the spironolactone group relative to controls was significant (P = .04). Moreover, the spironolactone-treated patients had a collective 394 HFpEF hospitalizations, markedly fewer than the 475 in controls. This translated to a hospitalization for heart failure with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction occurring at a rate of 3.8 per 100 person-years in patients randomized to spironolactone, compared with the 4.6 per 100 person-years in placebo-treated controls.

Hyperkalemia in excess of 5.5 mmol/L occurred in 18.7% of the spironolactone group, twice the rate of controls (9.1%). And the incidence of a creatinine level more than double the upper limit of normal was 49% greater in the spironolactone group. That said, neither of these laboratory abnormalities resulted in any serious adverse consequences because investigators adjusted the dose in response, explained Dr. Pfeffer, professor of medicine at Harvard University, Boston.

He drew special attention to two points: The primary composite event rate in placebo-treated patients in the Americas was 31.8% consistent with what has been seen in other studies of HFpEF – compared to a mere 8.4% in Eastern Europe. And patients who qualified for TOPCAT on the basis of an elevated natriuretic peptide level had a primary endpoint rate of 15.9% with spironolactone, a highly significant 35% reduction compared with the 23.6% in controls, suggesting that an elevated baseline natriuretic peptide level may be a biomarker useful in identifying those HFpEF patients most likely to respond to an aldosterone antagonist.

Dr. Pfeffer said that because the pharmaceutical industry has zero interest in spironolactone and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), which sponsored TOPCAT, has finite resources, he doubts there will be any further large studies of the drug in HFpEF.

"One is going to have to make decisions based on this trial. I don’t see another trial behind us," the cardiologist said.

And while TOPCAT was flawed, he said it contains a compelling message for clinicians: "I think we have an important finding here. We’re very confident that with this generic medication, which costs pennies per day, we can reduce hospitalizations for heart failure, which are the major burden in patients with HFpEF."

Discussant Dr. Margaret M. Redfield was more cautious. While there was a sound rationale for studying spironolactone in HFpEF based upon its impressive benefits in systolic heart failure as shown in earlier landmark clinical trials, given that the drug didn’t result in a significant reduction in all-cause hospitalizations, she said she wants to see evidence of improved patient-centered outcomes, such as quality of life, before prescribing spironolactone for HFpEF.

"One has to worry that the problems with worsening renal function and hyperkalemia may be much more common in clinical practice than in the highly monitored environment of a clinical trial," added Dr. Redfield, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Other heart failure experts not involved in TOPCAT took a more positive view of the study.

Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, AHA spokesperson, said in an interview that HFpEF is probably even more common than systolic heart failure, and it is a disease for which physicians have had no proven-effective treatments.

"You can almost justifiably say, ‘Let’s just look at the Americas, where patients had event rates that are consistent with the disease we think we understand.’ And it looks like there’s a signal there. I think that there’s enough evidence in TOPCAT for the clinical pragmatist to be able to be comfortable that spironolactone is probably beneficial and can be given safely. If you are convinced you can give it safely in your own clinical scenario, I think you should use it," said Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Marco Metra, a cardiologist at the University of Brescia (Italy), said he interprets the TOPCAT results as an indication for prescribing spironolactone, at least in HFpEF patients with high natriuretic peptide levels or multiple heart failure hospitalizations.

Dr. Pitt, emeritus professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, emphasized that in prescribing spironolactone, whether for HFpEF or systolic heart failure, it’s obligatory to measure potassium and creatinine levels at baseline, when changing the dose, and at each routine follow-up visit, titrating in response to the results. Failure to do so is akin to prescribing warfarin for a patient with atrial fibrillation and then never measuring the INR (international normalized ratio) he said.

TOPCAT was sponsored by the National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Pfeffer and Dr. Pitt serve as consultants to numerous pharmaceutical companies that had no involvement in the trial.

DALLAS – Spironolactone did not hit a home run in the large international "treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist" (TOPCAT) trial, but it did knock out a solid single in the form of significantly reduced hospitalizations for this extremely common, chronic, high morbidity/mortality condition.

It was this positive result for an important prespecified secondary outcome that enabled TOPCAT to avoid becoming roadkill. Technically, TOPCAT was a negative clinical trial in that spironolactone did not significantly outperform placebo on the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular mortality, heart failure hospitalization, or aborted cardiac arrest.

Yet that negative primary outcome was controversial: The aldosterone antagonist actually showed a significant positive result for the composite endpoint in North and South American participants, yet the results were resoundingly negative – and also considerably out of whack with the characteristic arc of progressive heart failure – among the nearly one-half of TOPCAT participants in Russia and the Republic of Georgia.

"What happened in Russia and Georgia we just don’t understand," Dr. Bertram Pitt, TOPCAT steering committee chair, said in an interview, shaking his head. "The event rate with placebo in Eastern Europe was so low it’s not compatible with anything we know about heart failure. The signs and symptoms of HFpEF [heart failure with preserved ejection fraction] are nonspecific; they can be due to obesity, lung disease, and other things. Clearly there are some people getting into the major trials of HFpEF that probably don’t have it."

TOPCAT was a randomized, double-blind clinical trial comprising 3,445 participants with symptomatic HFpEF at 250 sites in the United States and five other countries. They were randomized to spironolactone or placebo and followed prospectively for a mean of 3.3 years. The starting dose of the aldosterone antagonist was 15 mg/day, with a target of 30 mg/day. The drug could be titrated within the range of 15-45 mg/day. Eight months into the trial, the mean daily dose was 25 mg.

Presenting the TOPCAT results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions, Dr. Marc A. Pfeffer noted that the primary composite endpoint occurred in 20.4% of placebo-treated controls and 18.6% on spironolactone, a statistically nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 17% reduction in the rate of hospitalization for HFpEF in the spironolactone group relative to controls was significant (P = .04). Moreover, the spironolactone-treated patients had a collective 394 HFpEF hospitalizations, markedly fewer than the 475 in controls. This translated to a hospitalization for heart failure with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction occurring at a rate of 3.8 per 100 person-years in patients randomized to spironolactone, compared with the 4.6 per 100 person-years in placebo-treated controls.

Hyperkalemia in excess of 5.5 mmol/L occurred in 18.7% of the spironolactone group, twice the rate of controls (9.1%). And the incidence of a creatinine level more than double the upper limit of normal was 49% greater in the spironolactone group. That said, neither of these laboratory abnormalities resulted in any serious adverse consequences because investigators adjusted the dose in response, explained Dr. Pfeffer, professor of medicine at Harvard University, Boston.

He drew special attention to two points: The primary composite event rate in placebo-treated patients in the Americas was 31.8% consistent with what has been seen in other studies of HFpEF – compared to a mere 8.4% in Eastern Europe. And patients who qualified for TOPCAT on the basis of an elevated natriuretic peptide level had a primary endpoint rate of 15.9% with spironolactone, a highly significant 35% reduction compared with the 23.6% in controls, suggesting that an elevated baseline natriuretic peptide level may be a biomarker useful in identifying those HFpEF patients most likely to respond to an aldosterone antagonist.

Dr. Pfeffer said that because the pharmaceutical industry has zero interest in spironolactone and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), which sponsored TOPCAT, has finite resources, he doubts there will be any further large studies of the drug in HFpEF.

"One is going to have to make decisions based on this trial. I don’t see another trial behind us," the cardiologist said.

And while TOPCAT was flawed, he said it contains a compelling message for clinicians: "I think we have an important finding here. We’re very confident that with this generic medication, which costs pennies per day, we can reduce hospitalizations for heart failure, which are the major burden in patients with HFpEF."

Discussant Dr. Margaret M. Redfield was more cautious. While there was a sound rationale for studying spironolactone in HFpEF based upon its impressive benefits in systolic heart failure as shown in earlier landmark clinical trials, given that the drug didn’t result in a significant reduction in all-cause hospitalizations, she said she wants to see evidence of improved patient-centered outcomes, such as quality of life, before prescribing spironolactone for HFpEF.

"One has to worry that the problems with worsening renal function and hyperkalemia may be much more common in clinical practice than in the highly monitored environment of a clinical trial," added Dr. Redfield, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Other heart failure experts not involved in TOPCAT took a more positive view of the study.

Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, AHA spokesperson, said in an interview that HFpEF is probably even more common than systolic heart failure, and it is a disease for which physicians have had no proven-effective treatments.

"You can almost justifiably say, ‘Let’s just look at the Americas, where patients had event rates that are consistent with the disease we think we understand.’ And it looks like there’s a signal there. I think that there’s enough evidence in TOPCAT for the clinical pragmatist to be able to be comfortable that spironolactone is probably beneficial and can be given safely. If you are convinced you can give it safely in your own clinical scenario, I think you should use it," said Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Marco Metra, a cardiologist at the University of Brescia (Italy), said he interprets the TOPCAT results as an indication for prescribing spironolactone, at least in HFpEF patients with high natriuretic peptide levels or multiple heart failure hospitalizations.

Dr. Pitt, emeritus professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, emphasized that in prescribing spironolactone, whether for HFpEF or systolic heart failure, it’s obligatory to measure potassium and creatinine levels at baseline, when changing the dose, and at each routine follow-up visit, titrating in response to the results. Failure to do so is akin to prescribing warfarin for a patient with atrial fibrillation and then never measuring the INR (international normalized ratio) he said.

TOPCAT was sponsored by the National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Pfeffer and Dr. Pitt serve as consultants to numerous pharmaceutical companies that had no involvement in the trial.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Major finding: Hospitalization for heart failure with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction occurred at a rate of 3.8 per 100 person-years in patients randomized to spironolactone, a significant 17% risk reduction compared with the 4.6 per 100 person-years in placebo-treated controls.

Data source: TOPCAT, a randomized, double-blind, six-country clinical trial involving 3,445 patients with symptomatic heart failure and an ejection fraction of 45% or more.

Disclosures:. TOPCAT was sponsored by the National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Pfeffer and Dr. Pitt serve as consultants to pharmaceutical companies that had no involvement in the trial.

Guideline authors, AHA-ACC leaders confident in risk calculator

DALLAS – In the face of high-profile criticism of the new U.S. cholesterol-management guidelines released by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association on Nov. 12, the physicians who crafted the guidelines, as well as the leadership of the two organizations, stood firmly behind the work, reiterating that it is a big step forward in the battle against atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

During a last-minute press conference called on Monday morning, Nov. 18, to address concerns that first bubbled up over the prior weekend, a series of representatives from the guideline-writing panel stressed that the new cardiovascular-risk-calculation formula introduced in the guidelines reflected the best and most comprehensive evidence available today. They also stressed that the guidelines do not advocate simply using the formula and a rigid risk-threshold to decide whether or not a patient should receive a statin, but instead tell physicians and their patients to use the risk calculator as the starting point for a discussion of the risks and benefits that statin treatment might pose for each person.

"I think these are these are the most carefully vetted guidelines ever published," said Dr. Mariell Jessup, AHA president. "We’re confident that they are based on the best evidence."

"We intend to move forward with implementation of these guidelines," said Dr. Sidney Smith, professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and chair of the ACC/AHA subcommittee on prevention guidelines.

The controversy began with an analysis run by two Harvard researchers starting on the day the guidelines and risk calculator came out that applied the new risk calculator to three databases at their immediate disposal, the Women’s Health Study, the Physicians’ Health Study, and the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. They found that the risk calculator overestimated the 10-year rate of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) event by 75%-150%, doubling the actual, observed risk in these three cohorts. The authors of the analysis, Dr. Paul M. Ridker and Nancy R. Cook, Sc.D., of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, published their results in a brief article published online in the Lancet on Nov. 19.

Based on their calculations, "it is possible that as many as 40% to 50% of the 33 million Americans targeted by the new guidelines for statin therapy do not actually have risk thresholds exceeding the 7.5% level suggested for treatment," the two researchers wrote. "Miscalibration to this extent should be reconciled and addressed ... before these new prediction models are widely implemented."

Their analysis was made available to the New York Times over the weekend, which led to a prominent story in the newspaper’s Nov. 18 edition that called this overestimate by the risk calculator a "major embarrassment," and quoted some prominent cardiologists who also called for a delay in implementation of the new guidelines and risk calculator.

The researchers who devised the calculator responded by acknowledging the flaws in the device, something they had already done in their manuscript, but stressed that it represented a major improvement over the risk calculator from the prior guidelines, the third edition of the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) used for the past 12 years, particularly because of its inclusion of strokes as a ASCVD endpoint and its reliance on databases that had substantial numbers of African Americans, two major features missing from ATP III.

A risk calculator "will never be perfect, but this is a huge step ahead from where we were 12 years ago," said Dr. Donald Lloyd-Jones, professor of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and cochair of the panel that developed the risk calculator. "We made it better for women [by including stroke as an outcome], for African Americans, and for white men, too. We feel very confident that we are in a great place now, but as more data become available, we’re very happy to see if we can improve it further. You can certainly criticize the calculator, but I don’t know of anything that’s better," he said in an interview.

Other experts who led development of the new guidelines also stressed that they do not call for blindly prescribing a statin to every person whose risk calculates at or above 7.5%.

"No one said that patients automatically get a statin. We said that there needs to be a risk discussion between the patient and physician, because sometimes the numbers make sense and sometimes they don’t," said Dr. Neil Stone, Robert Bonow Professor in the division of medicine-cardiology at Northwestern University and chair of the ACC/AHA panel that wrote the new guidelines. "For the first time, we built into the guidelines the unique judgment of physicians, and patients’ personal preferences." Risk calculation "is the start of a discussion" between a physician and patient, not the endpoint. He also noted that the guidelines included a built-in "buffer" because "we had evidence that statins are effective even for patients with a 5% risk" for an ASCVD event over the subsequent 10 years.

The guidelines say that it is "reasonable to offer" statin treatment to a middle-age person with a 7.5% or greater 10-year risk for a ASCVD event and no other risks that warrant statin treatment and that before starting statin treatment, it is "reasonable" for a physician and patient to have a discussion that covers the patient’s individual risk level, the potential risks and benefits of statin treatment, and patient preference.

Aside from their critique of the risk calculator, Dr. Ridker and Dr. Cook applauded the overall guidelines in their commentary, calling them "a major step in the right direction."

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

DALLAS – In the face of high-profile criticism of the new U.S. cholesterol-management guidelines released by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association on Nov. 12, the physicians who crafted the guidelines, as well as the leadership of the two organizations, stood firmly behind the work, reiterating that it is a big step forward in the battle against atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

During a last-minute press conference called on Monday morning, Nov. 18, to address concerns that first bubbled up over the prior weekend, a series of representatives from the guideline-writing panel stressed that the new cardiovascular-risk-calculation formula introduced in the guidelines reflected the best and most comprehensive evidence available today. They also stressed that the guidelines do not advocate simply using the formula and a rigid risk-threshold to decide whether or not a patient should receive a statin, but instead tell physicians and their patients to use the risk calculator as the starting point for a discussion of the risks and benefits that statin treatment might pose for each person.

"I think these are these are the most carefully vetted guidelines ever published," said Dr. Mariell Jessup, AHA president. "We’re confident that they are based on the best evidence."

"We intend to move forward with implementation of these guidelines," said Dr. Sidney Smith, professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and chair of the ACC/AHA subcommittee on prevention guidelines.

The controversy began with an analysis run by two Harvard researchers starting on the day the guidelines and risk calculator came out that applied the new risk calculator to three databases at their immediate disposal, the Women’s Health Study, the Physicians’ Health Study, and the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. They found that the risk calculator overestimated the 10-year rate of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) event by 75%-150%, doubling the actual, observed risk in these three cohorts. The authors of the analysis, Dr. Paul M. Ridker and Nancy R. Cook, Sc.D., of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, published their results in a brief article published online in the Lancet on Nov. 19.

Based on their calculations, "it is possible that as many as 40% to 50% of the 33 million Americans targeted by the new guidelines for statin therapy do not actually have risk thresholds exceeding the 7.5% level suggested for treatment," the two researchers wrote. "Miscalibration to this extent should be reconciled and addressed ... before these new prediction models are widely implemented."

Their analysis was made available to the New York Times over the weekend, which led to a prominent story in the newspaper’s Nov. 18 edition that called this overestimate by the risk calculator a "major embarrassment," and quoted some prominent cardiologists who also called for a delay in implementation of the new guidelines and risk calculator.

The researchers who devised the calculator responded by acknowledging the flaws in the device, something they had already done in their manuscript, but stressed that it represented a major improvement over the risk calculator from the prior guidelines, the third edition of the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) used for the past 12 years, particularly because of its inclusion of strokes as a ASCVD endpoint and its reliance on databases that had substantial numbers of African Americans, two major features missing from ATP III.

A risk calculator "will never be perfect, but this is a huge step ahead from where we were 12 years ago," said Dr. Donald Lloyd-Jones, professor of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and cochair of the panel that developed the risk calculator. "We made it better for women [by including stroke as an outcome], for African Americans, and for white men, too. We feel very confident that we are in a great place now, but as more data become available, we’re very happy to see if we can improve it further. You can certainly criticize the calculator, but I don’t know of anything that’s better," he said in an interview.

Other experts who led development of the new guidelines also stressed that they do not call for blindly prescribing a statin to every person whose risk calculates at or above 7.5%.

"No one said that patients automatically get a statin. We said that there needs to be a risk discussion between the patient and physician, because sometimes the numbers make sense and sometimes they don’t," said Dr. Neil Stone, Robert Bonow Professor in the division of medicine-cardiology at Northwestern University and chair of the ACC/AHA panel that wrote the new guidelines. "For the first time, we built into the guidelines the unique judgment of physicians, and patients’ personal preferences." Risk calculation "is the start of a discussion" between a physician and patient, not the endpoint. He also noted that the guidelines included a built-in "buffer" because "we had evidence that statins are effective even for patients with a 5% risk" for an ASCVD event over the subsequent 10 years.

The guidelines say that it is "reasonable to offer" statin treatment to a middle-age person with a 7.5% or greater 10-year risk for a ASCVD event and no other risks that warrant statin treatment and that before starting statin treatment, it is "reasonable" for a physician and patient to have a discussion that covers the patient’s individual risk level, the potential risks and benefits of statin treatment, and patient preference.

Aside from their critique of the risk calculator, Dr. Ridker and Dr. Cook applauded the overall guidelines in their commentary, calling them "a major step in the right direction."

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

DALLAS – In the face of high-profile criticism of the new U.S. cholesterol-management guidelines released by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association on Nov. 12, the physicians who crafted the guidelines, as well as the leadership of the two organizations, stood firmly behind the work, reiterating that it is a big step forward in the battle against atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

During a last-minute press conference called on Monday morning, Nov. 18, to address concerns that first bubbled up over the prior weekend, a series of representatives from the guideline-writing panel stressed that the new cardiovascular-risk-calculation formula introduced in the guidelines reflected the best and most comprehensive evidence available today. They also stressed that the guidelines do not advocate simply using the formula and a rigid risk-threshold to decide whether or not a patient should receive a statin, but instead tell physicians and their patients to use the risk calculator as the starting point for a discussion of the risks and benefits that statin treatment might pose for each person.

"I think these are these are the most carefully vetted guidelines ever published," said Dr. Mariell Jessup, AHA president. "We’re confident that they are based on the best evidence."

"We intend to move forward with implementation of these guidelines," said Dr. Sidney Smith, professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and chair of the ACC/AHA subcommittee on prevention guidelines.

The controversy began with an analysis run by two Harvard researchers starting on the day the guidelines and risk calculator came out that applied the new risk calculator to three databases at their immediate disposal, the Women’s Health Study, the Physicians’ Health Study, and the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. They found that the risk calculator overestimated the 10-year rate of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) event by 75%-150%, doubling the actual, observed risk in these three cohorts. The authors of the analysis, Dr. Paul M. Ridker and Nancy R. Cook, Sc.D., of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, published their results in a brief article published online in the Lancet on Nov. 19.

Based on their calculations, "it is possible that as many as 40% to 50% of the 33 million Americans targeted by the new guidelines for statin therapy do not actually have risk thresholds exceeding the 7.5% level suggested for treatment," the two researchers wrote. "Miscalibration to this extent should be reconciled and addressed ... before these new prediction models are widely implemented."

Their analysis was made available to the New York Times over the weekend, which led to a prominent story in the newspaper’s Nov. 18 edition that called this overestimate by the risk calculator a "major embarrassment," and quoted some prominent cardiologists who also called for a delay in implementation of the new guidelines and risk calculator.

The researchers who devised the calculator responded by acknowledging the flaws in the device, something they had already done in their manuscript, but stressed that it represented a major improvement over the risk calculator from the prior guidelines, the third edition of the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) used for the past 12 years, particularly because of its inclusion of strokes as a ASCVD endpoint and its reliance on databases that had substantial numbers of African Americans, two major features missing from ATP III.

A risk calculator "will never be perfect, but this is a huge step ahead from where we were 12 years ago," said Dr. Donald Lloyd-Jones, professor of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and cochair of the panel that developed the risk calculator. "We made it better for women [by including stroke as an outcome], for African Americans, and for white men, too. We feel very confident that we are in a great place now, but as more data become available, we’re very happy to see if we can improve it further. You can certainly criticize the calculator, but I don’t know of anything that’s better," he said in an interview.

Other experts who led development of the new guidelines also stressed that they do not call for blindly prescribing a statin to every person whose risk calculates at or above 7.5%.

"No one said that patients automatically get a statin. We said that there needs to be a risk discussion between the patient and physician, because sometimes the numbers make sense and sometimes they don’t," said Dr. Neil Stone, Robert Bonow Professor in the division of medicine-cardiology at Northwestern University and chair of the ACC/AHA panel that wrote the new guidelines. "For the first time, we built into the guidelines the unique judgment of physicians, and patients’ personal preferences." Risk calculation "is the start of a discussion" between a physician and patient, not the endpoint. He also noted that the guidelines included a built-in "buffer" because "we had evidence that statins are effective even for patients with a 5% risk" for an ASCVD event over the subsequent 10 years.

The guidelines say that it is "reasonable to offer" statin treatment to a middle-age person with a 7.5% or greater 10-year risk for a ASCVD event and no other risks that warrant statin treatment and that before starting statin treatment, it is "reasonable" for a physician and patient to have a discussion that covers the patient’s individual risk level, the potential risks and benefits of statin treatment, and patient preference.

Aside from their critique of the risk calculator, Dr. Ridker and Dr. Cook applauded the overall guidelines in their commentary, calling them "a major step in the right direction."

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT OPINION AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Anticoagulant edoxaban comparable with warfarin in atrial fib

Two doses of the once-daily, oral factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban were noninferior to warfarin in preventing stroke or systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation in the phase III ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial.

The primary endpoint of stroke or embolic events was seen in 1.50% of patients per year on well-controlled warfarin vs. 1.18% with edoxaban 60 mg (hazard ratio, 0.79; P less than .001 for noninferiority) and 1.61% with edoxaban 30 mg (HR, 1.07; P = .005 for noninferiority), Dr. Robert P. Giugliano reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Edoxaban also bested oral warfarin on the study’s principal safety endpoint of major bleeding and significantly reduced bleeding and death from cardiovascular causes in the study, published simultaneously with the presentation (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013 Nov. 19 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1310907]).

Edoxaban is currently approved only in Japan (Lixiana) for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention after major orthopedic surgery, although regulatory filings are expected in the United States, Europe, and Japan in 2014 following recent positive results phase III results for the treatment and prevention of recurrent symptomatic VTE.

Though positive, the results of ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 (Effective Anticoagulation With Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation – Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48) do little to distinguish edoxaban from other novel oral anticoagulants entering the market, including the factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and apixaban (Eliquis), and the twice-daily direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa).

Approval of the lower dose of edoxaban is unlikely as it barely meets noninferiority for the primary endpoint in the intention-to-treat analysis (upper 95% confidence interval bound of 1.34; noninferiority margin of 1.38) – and ischemic stroke was significantly worse than warfarin (1.77% per year vs. 1.25% per year; HR, 1.41; P less than .001), observed cardiologist Dr. Sanjay Kaul of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

High-dose edoxaban had the same ischemic stroke rate as warfarin, 1.25%.

Annualized rates of hemorrhagic stroke were 0.47% with warfarin, compared with 0.26% with high-dose edoxaban (HR, 0.54) and 0.16% with low-dose edoxaban (HR, 0.33; both P less than .001).

High-dose edoxaban also failed to meet superiority over warfarin for the primary endpoint in a prespecified intention-to-treat analysis (1.57% vs. 1.80%; HR, 0.87; P = .08), so a superiority claim won’t be allowed.

"Marketability might be an issue, as the treatment advantage is not overwhelming," Dr. Kaul said in an interview. "Being the fourth kid on the block with no unique advantage might challenge its acceptability in clinical practice and marketability."

ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 enrolled 21,105 patients with moderate- to high-risk atrial fibrillation. One-quarter had paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, median follow-up was 2.8 years, and the warfarin group was in the therapeutic range for a median of 68.4% of the treatment period.