User login

Oncology treatment errors: Emerging data shed light on risk factors, prevention

ORLANDO – Accumulating evidence is helping researchers better understand why errors occur during the delivery of cancer treatment and how to prevent them. Findings from a trio of studies were reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Identifying causes of incidents in radiation therapy

In the first study, Greg D. Judy, MD, a radiation oncology resident at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and his colleagues retrospectively reviewed records in their institution’s reporting system, called Good Catch, to identify near-miss incidents (ones that didn’t reach the patient) and safety incidents (ones that did) among patients undergoing radiation therapy from October 2014 through April 2016.

Multivariate analysis showed that patients had a significantly higher risk of near-miss or safety incidents if they had stage T2 disease (odds ratio, 3.3), were being treated for cancer involving the head and neck (5.2), or were receiving image-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy (3.0) or daily imaging as part of their treatment (7.0), Dr. Judy reported.

“Head and neck site and image-guided IMRT [intensity-modulated radiation therapy] are complex entities: They have multiple steps in both the planning and delivery phase,” he said. “Daily imaging as well. It’s a much more complex process to do daily imaging for setup verification than it is to do once-a-week or even once-every-2-weeks setup verification.”

On the other hand, it was unclear why T2 stage was a risk factor. “We kind of hypothesized that it might be more of the disease site that really drives this, as you can have HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer which usually has lower T stages and more advanced nodal stages, but even then, that’s a head and neck site and we usually use image-guided IMRT, which are both very complex entities,” he said. The most common root causes for the incidents were issues related to documentation and scheduling (29% each), followed by issues related to communication (22%), technical treatment planning (14%), and technical treatment delivery (6%).

Incidents having a communication root cause were more likely than were others to affect patients (P less than .001), and those having a technical treatment delivery root cause were more likely to have higher severity (P = .005).

“Like some other studies, we found really the key factor was the complexity of the treatment plan and complexity of the overall process that is the real driving factor. This is important to understand because it promotes the idea of developing a more dedicated and robust QA system for complex cases,” said Dr. Judy. “It also highlights the importance of a strong reporting system to support a safety culture, as well as promote the continuous learning improvements within a department.”

The national Radiation Oncology Incident Learning System (RO-ILS) has been developed by the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). “This is gaining membership very rapidly, and it’s good because it facilitates cooperative research and also safety standards for our field,” he maintained.

“I’ll argue that they did that for a variety of reasons,” he elaborated. “Strong and effective leadership by Dr. Larry Marks, who’s really created a departmental culture of safety in which people can feel free to speak up. They have this wonderful Good Catch program in place. And they have these simulation review huddles ... where people feel free to talk about what happened yesterday or today that may be relevant moving forward.”

As for the national RO-ILS initiative, “I would look out to the audience and say, why is it that we don’t have such a program in medical oncology?” Dr. Jacobson said. “It’s probably time for us to do this,” he maintained.

Reducing chemotherapy errors in pediatric oncology

In the second study, Brian D. Weiss, MD, associate director of safety and compliance at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his colleagues studied the impact of a safety initiative to prevent chemotherapy errors at their large urban pediatric academic center (J Clin Oncol 35, 2017 [suppl 8S; abstract 37]).

“Pediatric chemotherapy protocols are different from adult protocols. We dose based on age or weight or body surface area, and that can change within a protocol. You have to do adjustments every time they gain weight or grow some, which is different than for adult protocols,” he explained. “We have parents administering chemo at home. And the protocols most patients are on are very complicated, but there is no standardized format, so it makes crucial information for dose adjustments difficult to find.”

The team successively implemented about half a dozen interventions, such as dedicated chemotherapy safety zones where staff were not to be disturbed while checking orders and ear protectors as a visual deterrent to interruptions; a new chemotherapy registered nurse role with a detailed list of responsibilities; an event-reporting system to supplement the center’s error-reporting system and capture events not reaching the patient (near-miss events); and a daily chemotherapy huddle to discuss errors in a nonpunitive setting and review upcoming chemotherapy for readiness.

In the 6 years after the start of the initiative, 105,187 chemotherapy doses were administered at the center and 998 errors occurred, including 250 errors that reached the patient, according to results reported at the symposium and recently published (J Oncol Pract. 2017 April;13:e329-e336).

At the 22-month mark, the rate of chemotherapy errors reaching the patient had fallen from 3.8 in 1,000 doses at baseline to 1.9 in 1,000 doses. The reduction has since persisted for more than 4 years and translates to an estimated 155 fewer predicted errors reaching the patient because of the initiative.

“The errors that reached the patient were more often administration and dispensing errors,” Dr. Weiss said. “About two-thirds of those errors that didn’t reach the patient – because they got caught by the pharmacists and the nurses – were prescription errors.

“Our chemotherapy huddle has certainly increased our reporting of errors. We also now use it for patients on clinical trials ... any patient getting PK [pharmacokinetics] or PD [pharmacodynamics] sampled within the next 24 hours is reviewed at that meeting. And our missed samples have gone down significantly,” he noted. “It’s allowed us to manage our bed space better because now everybody knows who’s definitely coming in the next day and who’s maybe coming in the next day.”

“We are a large urban academic pediatric medical center. Some of these things may seem difficult to translate [to smaller facilities], but I’m not sure they are,” concluded Dr. Weiss.

Dr. Jacobson, the discussant, noted that the initiative was in keeping with this health system’s longstanding “obsessive” focus on patient safety and commended its rigorousness in, for example, setting clear goals, focusing on key drivers [processes] needed for change, and selecting a good outcome metric.

“This is very successful project,” he said. The success can be attributed to “strong and effective organization and leadership, building a culture of safety at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, and an important predefined measurement program and methodology.”

Building chemotherapy regimens more accurately

In the third study, a team led by Andrea Crespo, BSc, BScPhm, BCOP, an oncology pharmacist and member of the Systemic Treatment Team at Cancer Care Ontario, Toronto, studied errors introduced when chemotherapy regimens were moved from publications into orders used by centers in the province (J Clin Oncol. 35, 2017 [suppl 8S; abstract 51]).

Nearly all outpatient intravenous systemic treatment visits in Ontario are supported by a Systemic Treatment Computerized Prescriber Order Entry (ST-CPOE) system, she noted. Such systems can reduce error rates but are not foolproof.

She and her colleagues asked all Ontario treatment centers to review their active chemotherapy regimens. Data were analyzed to determine whether the regimens were built as intended with respect to their component drugs and doses, leading to identification of any unintentional discrepancies with the original regimen.

A total of 33 centers performed the review, and the median number of regimens reviewed was 375 per center, Ms. Crespo reported.

Unintentional discrepancies in regimens were found at 27% of centers. The total number reported was 369 discrepancies, with a range from 2 to 198 per center.

All of the nine centers where discrepancies were found participated in the provincial ST-CPOE system, and most had for at least 20 years. Furthermore, eight of them used a team of at least two pharmacists and one oncologist to build their regimens. “So you can see that discrepancies occurred despite a fairly rigorous regimen-build process and many years of experience with the system,” she said.

Of the 369 total discrepancies, 41% were related to alignment with the Systemic Treatment Quality-Based Program regimen, and 32% were regimens flagged to be inactivated because of outdated information, new standards, or lack of use.

A detailed analysis of the remaining 27%, or 101 unintentional discrepancies, showed that the majority were due to missing information (35.6%) or missing drugs (13.9%), incorrect doses (10.9%), and incorrect or missing schedules (10.9%). Potential to cause harm was mild for 55%, moderate for 28%, and none for 17%.

“Corrective action has been taken to address the discrepancies identified,” said Ms. Crespo.

Only 6% of the 33 centers reported having an established regimen review and maintenance process in place before the study, but all now have such a process. In addition, some centers that did not find any regimen discrepancies nonetheless reported adding quality improvement activities, such as changes in the ways regimens were built and documented, and revising regimen names to facilitate accurate selection.

In discussing the study, Dr. Jacobson noted the low proportion of centers having an established process at baseline to ensure appropriate regimen maintenance and updates. “You might want to think to yourselves, the medical oncologists in the group, whether your center has such a process in place,” he proposed.

It is not yet known whether the project has met its goal of improving the quality and accuracy of oncology regimens in Ontario, he maintained. “We are going to have to invite [Ms. Crespo] back in a year or two to see whether that turns out to be true.” On the other hand, “clearly what they have achieved was the ability to measure the variance between what was intended and what was actually built.”

Chief among the reasons for success, again, “was a strong and effective leadership and organizational structure, not at the department level or hospital level, but across the entire province through Cancer Care Ontario,” Dr. Jacobson said. “It’s clear that they have a focus on quality and patient safety, and this measurement program that they have put in place turned out to be useful.”

Dr. Judy, Dr. Weiss, and Ms. Crespo disclosed that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Accumulating evidence is helping researchers better understand why errors occur during the delivery of cancer treatment and how to prevent them. Findings from a trio of studies were reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Identifying causes of incidents in radiation therapy

In the first study, Greg D. Judy, MD, a radiation oncology resident at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and his colleagues retrospectively reviewed records in their institution’s reporting system, called Good Catch, to identify near-miss incidents (ones that didn’t reach the patient) and safety incidents (ones that did) among patients undergoing radiation therapy from October 2014 through April 2016.

Multivariate analysis showed that patients had a significantly higher risk of near-miss or safety incidents if they had stage T2 disease (odds ratio, 3.3), were being treated for cancer involving the head and neck (5.2), or were receiving image-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy (3.0) or daily imaging as part of their treatment (7.0), Dr. Judy reported.

“Head and neck site and image-guided IMRT [intensity-modulated radiation therapy] are complex entities: They have multiple steps in both the planning and delivery phase,” he said. “Daily imaging as well. It’s a much more complex process to do daily imaging for setup verification than it is to do once-a-week or even once-every-2-weeks setup verification.”

On the other hand, it was unclear why T2 stage was a risk factor. “We kind of hypothesized that it might be more of the disease site that really drives this, as you can have HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer which usually has lower T stages and more advanced nodal stages, but even then, that’s a head and neck site and we usually use image-guided IMRT, which are both very complex entities,” he said. The most common root causes for the incidents were issues related to documentation and scheduling (29% each), followed by issues related to communication (22%), technical treatment planning (14%), and technical treatment delivery (6%).

Incidents having a communication root cause were more likely than were others to affect patients (P less than .001), and those having a technical treatment delivery root cause were more likely to have higher severity (P = .005).

“Like some other studies, we found really the key factor was the complexity of the treatment plan and complexity of the overall process that is the real driving factor. This is important to understand because it promotes the idea of developing a more dedicated and robust QA system for complex cases,” said Dr. Judy. “It also highlights the importance of a strong reporting system to support a safety culture, as well as promote the continuous learning improvements within a department.”

The national Radiation Oncology Incident Learning System (RO-ILS) has been developed by the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). “This is gaining membership very rapidly, and it’s good because it facilitates cooperative research and also safety standards for our field,” he maintained.

“I’ll argue that they did that for a variety of reasons,” he elaborated. “Strong and effective leadership by Dr. Larry Marks, who’s really created a departmental culture of safety in which people can feel free to speak up. They have this wonderful Good Catch program in place. And they have these simulation review huddles ... where people feel free to talk about what happened yesterday or today that may be relevant moving forward.”

As for the national RO-ILS initiative, “I would look out to the audience and say, why is it that we don’t have such a program in medical oncology?” Dr. Jacobson said. “It’s probably time for us to do this,” he maintained.

Reducing chemotherapy errors in pediatric oncology

In the second study, Brian D. Weiss, MD, associate director of safety and compliance at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his colleagues studied the impact of a safety initiative to prevent chemotherapy errors at their large urban pediatric academic center (J Clin Oncol 35, 2017 [suppl 8S; abstract 37]).

“Pediatric chemotherapy protocols are different from adult protocols. We dose based on age or weight or body surface area, and that can change within a protocol. You have to do adjustments every time they gain weight or grow some, which is different than for adult protocols,” he explained. “We have parents administering chemo at home. And the protocols most patients are on are very complicated, but there is no standardized format, so it makes crucial information for dose adjustments difficult to find.”

The team successively implemented about half a dozen interventions, such as dedicated chemotherapy safety zones where staff were not to be disturbed while checking orders and ear protectors as a visual deterrent to interruptions; a new chemotherapy registered nurse role with a detailed list of responsibilities; an event-reporting system to supplement the center’s error-reporting system and capture events not reaching the patient (near-miss events); and a daily chemotherapy huddle to discuss errors in a nonpunitive setting and review upcoming chemotherapy for readiness.

In the 6 years after the start of the initiative, 105,187 chemotherapy doses were administered at the center and 998 errors occurred, including 250 errors that reached the patient, according to results reported at the symposium and recently published (J Oncol Pract. 2017 April;13:e329-e336).

At the 22-month mark, the rate of chemotherapy errors reaching the patient had fallen from 3.8 in 1,000 doses at baseline to 1.9 in 1,000 doses. The reduction has since persisted for more than 4 years and translates to an estimated 155 fewer predicted errors reaching the patient because of the initiative.

“The errors that reached the patient were more often administration and dispensing errors,” Dr. Weiss said. “About two-thirds of those errors that didn’t reach the patient – because they got caught by the pharmacists and the nurses – were prescription errors.

“Our chemotherapy huddle has certainly increased our reporting of errors. We also now use it for patients on clinical trials ... any patient getting PK [pharmacokinetics] or PD [pharmacodynamics] sampled within the next 24 hours is reviewed at that meeting. And our missed samples have gone down significantly,” he noted. “It’s allowed us to manage our bed space better because now everybody knows who’s definitely coming in the next day and who’s maybe coming in the next day.”

“We are a large urban academic pediatric medical center. Some of these things may seem difficult to translate [to smaller facilities], but I’m not sure they are,” concluded Dr. Weiss.

Dr. Jacobson, the discussant, noted that the initiative was in keeping with this health system’s longstanding “obsessive” focus on patient safety and commended its rigorousness in, for example, setting clear goals, focusing on key drivers [processes] needed for change, and selecting a good outcome metric.

“This is very successful project,” he said. The success can be attributed to “strong and effective organization and leadership, building a culture of safety at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, and an important predefined measurement program and methodology.”

Building chemotherapy regimens more accurately

In the third study, a team led by Andrea Crespo, BSc, BScPhm, BCOP, an oncology pharmacist and member of the Systemic Treatment Team at Cancer Care Ontario, Toronto, studied errors introduced when chemotherapy regimens were moved from publications into orders used by centers in the province (J Clin Oncol. 35, 2017 [suppl 8S; abstract 51]).

Nearly all outpatient intravenous systemic treatment visits in Ontario are supported by a Systemic Treatment Computerized Prescriber Order Entry (ST-CPOE) system, she noted. Such systems can reduce error rates but are not foolproof.

She and her colleagues asked all Ontario treatment centers to review their active chemotherapy regimens. Data were analyzed to determine whether the regimens were built as intended with respect to their component drugs and doses, leading to identification of any unintentional discrepancies with the original regimen.

A total of 33 centers performed the review, and the median number of regimens reviewed was 375 per center, Ms. Crespo reported.

Unintentional discrepancies in regimens were found at 27% of centers. The total number reported was 369 discrepancies, with a range from 2 to 198 per center.

All of the nine centers where discrepancies were found participated in the provincial ST-CPOE system, and most had for at least 20 years. Furthermore, eight of them used a team of at least two pharmacists and one oncologist to build their regimens. “So you can see that discrepancies occurred despite a fairly rigorous regimen-build process and many years of experience with the system,” she said.

Of the 369 total discrepancies, 41% were related to alignment with the Systemic Treatment Quality-Based Program regimen, and 32% were regimens flagged to be inactivated because of outdated information, new standards, or lack of use.

A detailed analysis of the remaining 27%, or 101 unintentional discrepancies, showed that the majority were due to missing information (35.6%) or missing drugs (13.9%), incorrect doses (10.9%), and incorrect or missing schedules (10.9%). Potential to cause harm was mild for 55%, moderate for 28%, and none for 17%.

“Corrective action has been taken to address the discrepancies identified,” said Ms. Crespo.

Only 6% of the 33 centers reported having an established regimen review and maintenance process in place before the study, but all now have such a process. In addition, some centers that did not find any regimen discrepancies nonetheless reported adding quality improvement activities, such as changes in the ways regimens were built and documented, and revising regimen names to facilitate accurate selection.

In discussing the study, Dr. Jacobson noted the low proportion of centers having an established process at baseline to ensure appropriate regimen maintenance and updates. “You might want to think to yourselves, the medical oncologists in the group, whether your center has such a process in place,” he proposed.

It is not yet known whether the project has met its goal of improving the quality and accuracy of oncology regimens in Ontario, he maintained. “We are going to have to invite [Ms. Crespo] back in a year or two to see whether that turns out to be true.” On the other hand, “clearly what they have achieved was the ability to measure the variance between what was intended and what was actually built.”

Chief among the reasons for success, again, “was a strong and effective leadership and organizational structure, not at the department level or hospital level, but across the entire province through Cancer Care Ontario,” Dr. Jacobson said. “It’s clear that they have a focus on quality and patient safety, and this measurement program that they have put in place turned out to be useful.”

Dr. Judy, Dr. Weiss, and Ms. Crespo disclosed that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Accumulating evidence is helping researchers better understand why errors occur during the delivery of cancer treatment and how to prevent them. Findings from a trio of studies were reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Identifying causes of incidents in radiation therapy

In the first study, Greg D. Judy, MD, a radiation oncology resident at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and his colleagues retrospectively reviewed records in their institution’s reporting system, called Good Catch, to identify near-miss incidents (ones that didn’t reach the patient) and safety incidents (ones that did) among patients undergoing radiation therapy from October 2014 through April 2016.

Multivariate analysis showed that patients had a significantly higher risk of near-miss or safety incidents if they had stage T2 disease (odds ratio, 3.3), were being treated for cancer involving the head and neck (5.2), or were receiving image-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy (3.0) or daily imaging as part of their treatment (7.0), Dr. Judy reported.

“Head and neck site and image-guided IMRT [intensity-modulated radiation therapy] are complex entities: They have multiple steps in both the planning and delivery phase,” he said. “Daily imaging as well. It’s a much more complex process to do daily imaging for setup verification than it is to do once-a-week or even once-every-2-weeks setup verification.”

On the other hand, it was unclear why T2 stage was a risk factor. “We kind of hypothesized that it might be more of the disease site that really drives this, as you can have HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer which usually has lower T stages and more advanced nodal stages, but even then, that’s a head and neck site and we usually use image-guided IMRT, which are both very complex entities,” he said. The most common root causes for the incidents were issues related to documentation and scheduling (29% each), followed by issues related to communication (22%), technical treatment planning (14%), and technical treatment delivery (6%).

Incidents having a communication root cause were more likely than were others to affect patients (P less than .001), and those having a technical treatment delivery root cause were more likely to have higher severity (P = .005).

“Like some other studies, we found really the key factor was the complexity of the treatment plan and complexity of the overall process that is the real driving factor. This is important to understand because it promotes the idea of developing a more dedicated and robust QA system for complex cases,” said Dr. Judy. “It also highlights the importance of a strong reporting system to support a safety culture, as well as promote the continuous learning improvements within a department.”

The national Radiation Oncology Incident Learning System (RO-ILS) has been developed by the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). “This is gaining membership very rapidly, and it’s good because it facilitates cooperative research and also safety standards for our field,” he maintained.

“I’ll argue that they did that for a variety of reasons,” he elaborated. “Strong and effective leadership by Dr. Larry Marks, who’s really created a departmental culture of safety in which people can feel free to speak up. They have this wonderful Good Catch program in place. And they have these simulation review huddles ... where people feel free to talk about what happened yesterday or today that may be relevant moving forward.”

As for the national RO-ILS initiative, “I would look out to the audience and say, why is it that we don’t have such a program in medical oncology?” Dr. Jacobson said. “It’s probably time for us to do this,” he maintained.

Reducing chemotherapy errors in pediatric oncology

In the second study, Brian D. Weiss, MD, associate director of safety and compliance at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his colleagues studied the impact of a safety initiative to prevent chemotherapy errors at their large urban pediatric academic center (J Clin Oncol 35, 2017 [suppl 8S; abstract 37]).

“Pediatric chemotherapy protocols are different from adult protocols. We dose based on age or weight or body surface area, and that can change within a protocol. You have to do adjustments every time they gain weight or grow some, which is different than for adult protocols,” he explained. “We have parents administering chemo at home. And the protocols most patients are on are very complicated, but there is no standardized format, so it makes crucial information for dose adjustments difficult to find.”

The team successively implemented about half a dozen interventions, such as dedicated chemotherapy safety zones where staff were not to be disturbed while checking orders and ear protectors as a visual deterrent to interruptions; a new chemotherapy registered nurse role with a detailed list of responsibilities; an event-reporting system to supplement the center’s error-reporting system and capture events not reaching the patient (near-miss events); and a daily chemotherapy huddle to discuss errors in a nonpunitive setting and review upcoming chemotherapy for readiness.

In the 6 years after the start of the initiative, 105,187 chemotherapy doses were administered at the center and 998 errors occurred, including 250 errors that reached the patient, according to results reported at the symposium and recently published (J Oncol Pract. 2017 April;13:e329-e336).

At the 22-month mark, the rate of chemotherapy errors reaching the patient had fallen from 3.8 in 1,000 doses at baseline to 1.9 in 1,000 doses. The reduction has since persisted for more than 4 years and translates to an estimated 155 fewer predicted errors reaching the patient because of the initiative.

“The errors that reached the patient were more often administration and dispensing errors,” Dr. Weiss said. “About two-thirds of those errors that didn’t reach the patient – because they got caught by the pharmacists and the nurses – were prescription errors.

“Our chemotherapy huddle has certainly increased our reporting of errors. We also now use it for patients on clinical trials ... any patient getting PK [pharmacokinetics] or PD [pharmacodynamics] sampled within the next 24 hours is reviewed at that meeting. And our missed samples have gone down significantly,” he noted. “It’s allowed us to manage our bed space better because now everybody knows who’s definitely coming in the next day and who’s maybe coming in the next day.”

“We are a large urban academic pediatric medical center. Some of these things may seem difficult to translate [to smaller facilities], but I’m not sure they are,” concluded Dr. Weiss.

Dr. Jacobson, the discussant, noted that the initiative was in keeping with this health system’s longstanding “obsessive” focus on patient safety and commended its rigorousness in, for example, setting clear goals, focusing on key drivers [processes] needed for change, and selecting a good outcome metric.

“This is very successful project,” he said. The success can be attributed to “strong and effective organization and leadership, building a culture of safety at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, and an important predefined measurement program and methodology.”

Building chemotherapy regimens more accurately

In the third study, a team led by Andrea Crespo, BSc, BScPhm, BCOP, an oncology pharmacist and member of the Systemic Treatment Team at Cancer Care Ontario, Toronto, studied errors introduced when chemotherapy regimens were moved from publications into orders used by centers in the province (J Clin Oncol. 35, 2017 [suppl 8S; abstract 51]).

Nearly all outpatient intravenous systemic treatment visits in Ontario are supported by a Systemic Treatment Computerized Prescriber Order Entry (ST-CPOE) system, she noted. Such systems can reduce error rates but are not foolproof.

She and her colleagues asked all Ontario treatment centers to review their active chemotherapy regimens. Data were analyzed to determine whether the regimens were built as intended with respect to their component drugs and doses, leading to identification of any unintentional discrepancies with the original regimen.

A total of 33 centers performed the review, and the median number of regimens reviewed was 375 per center, Ms. Crespo reported.

Unintentional discrepancies in regimens were found at 27% of centers. The total number reported was 369 discrepancies, with a range from 2 to 198 per center.

All of the nine centers where discrepancies were found participated in the provincial ST-CPOE system, and most had for at least 20 years. Furthermore, eight of them used a team of at least two pharmacists and one oncologist to build their regimens. “So you can see that discrepancies occurred despite a fairly rigorous regimen-build process and many years of experience with the system,” she said.

Of the 369 total discrepancies, 41% were related to alignment with the Systemic Treatment Quality-Based Program regimen, and 32% were regimens flagged to be inactivated because of outdated information, new standards, or lack of use.

A detailed analysis of the remaining 27%, or 101 unintentional discrepancies, showed that the majority were due to missing information (35.6%) or missing drugs (13.9%), incorrect doses (10.9%), and incorrect or missing schedules (10.9%). Potential to cause harm was mild for 55%, moderate for 28%, and none for 17%.

“Corrective action has been taken to address the discrepancies identified,” said Ms. Crespo.

Only 6% of the 33 centers reported having an established regimen review and maintenance process in place before the study, but all now have such a process. In addition, some centers that did not find any regimen discrepancies nonetheless reported adding quality improvement activities, such as changes in the ways regimens were built and documented, and revising regimen names to facilitate accurate selection.

In discussing the study, Dr. Jacobson noted the low proportion of centers having an established process at baseline to ensure appropriate regimen maintenance and updates. “You might want to think to yourselves, the medical oncologists in the group, whether your center has such a process in place,” he proposed.

It is not yet known whether the project has met its goal of improving the quality and accuracy of oncology regimens in Ontario, he maintained. “We are going to have to invite [Ms. Crespo] back in a year or two to see whether that turns out to be true.” On the other hand, “clearly what they have achieved was the ability to measure the variance between what was intended and what was actually built.”

Chief among the reasons for success, again, “was a strong and effective leadership and organizational structure, not at the department level or hospital level, but across the entire province through Cancer Care Ontario,” Dr. Jacobson said. “It’s clear that they have a focus on quality and patient safety, and this measurement program that they have put in place turned out to be useful.”

Dr. Judy, Dr. Weiss, and Ms. Crespo disclosed that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT THE QUALITY CARE SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Risk factors for radiation therapy near-miss and safety incidents were T2 stage, H&N site, and more complex techniques (odds ratios, 3.0-7.0). A quality improvement initiative halved the rate of chemotherapy errors reaching the patient from 3.8 to 1.9 per 1,000 doses. Twenty-seven percent of centers found unintentional discrepancies in their chemotherapy regimens, 83% with potential to cause harm.

Data source: A retrospective case-control study of 400 patients receiving radiation therapy, a longitudinal cohort study of a quality improvement initiative at an urban pediatric academic medical center involving administration of 105,187 chemotherapy doses, and a cohort study of 33 Ontario treatment centers that reviewed a median of 375 chemotherapy regimens.

Disclosures: Dr. Judy, Dr. Weiss, and Ms. Crespo disclosed that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Survivorship care models work, some better than others

ORLANDO – Accumulating experience is showing the benefits of various models of care for cancer survivors in terms of health care use and costs, while also suggesting that some provide higher-quality care than others, according to a pair of studies reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Initiative for breast cancer survivors

“In 2011, Cancer Care Ontario did a quick environmental scan of our 14 regional cancer centers and found that the transition of breast cancer survivors from oncologists to primary care was very variable, and that centers often didn’t transition patients very frequently,” said Nicole Mittmann, PhD, first author on one of the studies, chief research officer for Cancer Care Ontario, and an investigator at Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto.

The advisory organization therefore implemented the Well Follow-Up Care Initiative to facilitate appropriate transition of breast cancer survivors. Each regional center was given a $100,000 incentive to roll out a model of the initiative.

Dr. Mittmann and her coinvestigators used provincial administrative databases to compare health care use and associated costs between 2,324 breast cancer survivors who were transitioned with the initiative and 2,324 propensity-matched control survivors who were not. The survivors were about 5 years out from their breast cancer diagnosis at baseline and had median follow-up of 2 years.

Study results reported at the symposium showed that the mean annual total cost of care per patient paid for by the provincial health ministry was $6,575 for the transitioned group and $10,832 for the nontransitioned group, a difference of $4,257 (39%). The main drivers were reduced costs of long-term care and cancer clinic visits.

Findings were similar for median annual costs, which amounted to $2,261 for the transitioned group and $2,903 for the control group, a difference of $638.

Compared with the nontransitioned group, the transitioned group had significantly fewer annual visits to medical oncologists (0.39 vs. 1.29) and radiation oncologists (0.16 vs. 0.36), while visits to general or family practitioners were statistically indistinguishable (7.35 and 7.91), Dr. Mittmann reported. There was also a trend toward fewer emergency department visits.

The transitioned group had fewer bone scans, CT and MRI scans, and radiographs annually, but differences were not significant.

Reassuringly, Dr. Mittmann said, survivors who were transitioned did not fare worse than their nontransitioned counterparts in overall survival; if anything, they tended to live longer. “We think that because the individual cancer centers enrolled patients that they thought were very well that this is a very well and highly selected and maybe a biased group,” Dr. Mittmann acknowledged. “But we certainly see that they are not doing worse than the control group.”

“About $1.4 million was distributed to the cancer centers” for the initiative, she noted. “That generated a savings for the health system of $1.5 million, if you are looking at median costs, to $9.9 million, if you are looking at mean costs.

“The transition of appropriate breast cancer survivors to the community appears to be safe and effective outside of a clinical trial, at least based on this particular retrospective analysis using databases,” she said. “The overall costs are not increased, and they may actually be decreased based on our data, and certainly these results will inform policy.”

The investigators plan several next steps, such as encouraging senior leadership at Cancer Care Ontario and the Ministry of Health to endorse the findings, according to Dr. Mittmann. In addition, “[we plan to] engage with both oncology and primary care leadership and think about how we can potentially roll out a program like this, and develop tools, whether those are letters or information packages, and education, to … appropriately transition individuals.”

Considerations in interpreting the study’s findings include the quality of the matching of survivors, according to invited discussant Monika K. Krzyzanowska, MD, a medical oncologist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, an associate professor at the University of Toronto, and a clinical lead of Quality Care and Access, Systemic Treatment Program, at Cancer Care Ontario. “The quality of that match depends on what’s in the model, so there could be potential for residual confounding, and administrative data may not have all of the elements that you would need to get a perfect match.”

Additional considerations include costs not covered by the payer, impact of the initiative on delivery of guideline-recommended care and patient and provider satisfaction, generalizability of the findings, and long-term outcomes.

“This is a proof of concept, certainly, that transition of low-risk cancer survivors to primary care is feasible and potentially economically attractive,” Dr. Krzyzanowska concluded. “It would be useful to have a formal evaluation of effectiveness that would inform a comprehensive value assessment. And we do have data from a randomized trial about the safety of this particular approach, but it would be nice to see that following implementation in real practices, those safety considerations played out the same way.”

Comparison of survivorship care models

Two-thirds of the large and growing population of cancer survivors are at least 5 years out from diagnosis, stimulating considerable discussion in the oncology community about how to best address their needs, according to Sarah Raskin, PhD, senior author on the second study and a research scientist at the Institute for Patient-Centered Initiatives and Health Equity at George Washington University Cancer Center, Washington.

“Yet, for a lack of cancer survivorship–specific guidelines from research or practice, cancer centers are increasingly developing survivorship care in a variety of ways, many of which are ad hoc or unproven as yet,” she said.

Dr. Raskin and her colleagues compared three emerging models of survivorship care: a specialized consultative model and a specialized longitudinal model – whereby patients have a single or multiple formalized survivorship visits, respectively, with care typically led by an oncology nurse-practitioner – and an oncology-embedded model – whereby survivorship is addressed as a part of ongoing oncology follow-up care, typically by the oncologist.

The investigators worked with survivors to develop the Patient-Prioritized Measure of High-Quality Survivorship Care, a 46-question scale assessing nine components of survivorship care that capture the health care priorities and needs that matter most to patients. Each component is rated on a scale from 0 (not at all met) to 1 (somewhat met) to 2 (definitely met).

Analyses were based on responses of 827 survivors of breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer who received care at 28 U.S. institutions using one of the above models and who were surveyed by telephone about the care received 1 week after their initial survivorship visit.

Results showed that survivors cared for under the three models differed significantly with respect to scores for seven of the nine components of quality of care, Dr. Raskin reported. The exceptions were practical life support, where the mean score was about 0.6-0.8 across the board, and having a medical home, where the mean score was about 1.8-1.9 across the board.

The specialized consult model of care had the highest scores for mental health and social support, information and resources, and supportive and prepared clinicians. The specialized longitudinal model of care had the highest scores for empowered and engaged patients, open patient-clinician communication, care coordination and transitions, and access to full spectrum of care. The oncology-embedded model had the lowest scores. Analysis of the tool’s 46 individual questions showed that patients cared for at institutions using the oncology-embedded model were significantly less likely than were counterparts cared for at institutions using the specialized models to report that the institution performed various activities such as offering a treatment summary, inquiring about the patient’s biggest worries or problems, and explaining the reasons why tests were needed (P less than .05 for each).

For some metrics, the overall proportion reporting that an activity was performed was low, regardless of the model being used. For example, only 48% of all patients reported being helped to set goals or make short-term plans to manage follow-up care and improve health, merely 24% reported being provided emotional and social support to deal with changes in relationships, and just 19% reported being referred to special providers for other medical problems.

“Overall, all three models are performing highly in terms of providing survivors with a medical home and communicating with patients. However, all three are performing quite low in terms of providing mental health and social support, as well as practical life support,” said Dr. Raskin.

“By model, we see that the embedded ongoing care model is significantly underperforming compared with both specialized models on seven of nine components, and we have some hypotheses from our early work with [Commission on Cancer]–accredited centers to explain this,” she added. “Embedded survivorship models have a lot of variability – many are high performers but others are low performers as compared with specialized programs. Embedded survivorship care models are typically led by the treating oncologist, who historically has focused on treating sick patients and less so on providing social supports for follow-up of well patients or ‘well-er’ patients. At the same time, specialized models focus predominantly on survivorship care and providing services and referrals for survivors, which may explain their high scores.

“We know that the higher quality of care measures presented here do not necessarily translate to better patient outcomes, and that’s actually going to be the next phase of our analysis,” she concluded.

The study sample may have had some selection bias, and it is unclear how well validated the tool was, according to Dr. Krzyzanowska, the discussant. Another issue was its assessment of quality of care at only a single time point.

Nonetheless, the findings show “that measuring quality of survivorship care from a patient perspective is feasible and valuable. We have already heard about [need for] survivorship plans in survivorship care, so certainly the work that was just presented is extremely important to help to fill some of these gaps,” she said.

“I’m not sure that we yet know what the optimal model of survivorship care is without the information of the other outcomes. Furthermore, there’s different survivor populations and different ways that health care is organized, so perhaps there isn’t really one optimal model, but the model has to fit with the context,” Dr. Krzyzanowska concluded. “That being said … the tool that they have created can be a great tool for existing survivorship care programs to assess and improve the quality of their care.”

Dr. Mittmann and Dr. Raskin had no disclosures to report.

ORLANDO – Accumulating experience is showing the benefits of various models of care for cancer survivors in terms of health care use and costs, while also suggesting that some provide higher-quality care than others, according to a pair of studies reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Initiative for breast cancer survivors

“In 2011, Cancer Care Ontario did a quick environmental scan of our 14 regional cancer centers and found that the transition of breast cancer survivors from oncologists to primary care was very variable, and that centers often didn’t transition patients very frequently,” said Nicole Mittmann, PhD, first author on one of the studies, chief research officer for Cancer Care Ontario, and an investigator at Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto.

The advisory organization therefore implemented the Well Follow-Up Care Initiative to facilitate appropriate transition of breast cancer survivors. Each regional center was given a $100,000 incentive to roll out a model of the initiative.

Dr. Mittmann and her coinvestigators used provincial administrative databases to compare health care use and associated costs between 2,324 breast cancer survivors who were transitioned with the initiative and 2,324 propensity-matched control survivors who were not. The survivors were about 5 years out from their breast cancer diagnosis at baseline and had median follow-up of 2 years.

Study results reported at the symposium showed that the mean annual total cost of care per patient paid for by the provincial health ministry was $6,575 for the transitioned group and $10,832 for the nontransitioned group, a difference of $4,257 (39%). The main drivers were reduced costs of long-term care and cancer clinic visits.

Findings were similar for median annual costs, which amounted to $2,261 for the transitioned group and $2,903 for the control group, a difference of $638.

Compared with the nontransitioned group, the transitioned group had significantly fewer annual visits to medical oncologists (0.39 vs. 1.29) and radiation oncologists (0.16 vs. 0.36), while visits to general or family practitioners were statistically indistinguishable (7.35 and 7.91), Dr. Mittmann reported. There was also a trend toward fewer emergency department visits.

The transitioned group had fewer bone scans, CT and MRI scans, and radiographs annually, but differences were not significant.

Reassuringly, Dr. Mittmann said, survivors who were transitioned did not fare worse than their nontransitioned counterparts in overall survival; if anything, they tended to live longer. “We think that because the individual cancer centers enrolled patients that they thought were very well that this is a very well and highly selected and maybe a biased group,” Dr. Mittmann acknowledged. “But we certainly see that they are not doing worse than the control group.”

“About $1.4 million was distributed to the cancer centers” for the initiative, she noted. “That generated a savings for the health system of $1.5 million, if you are looking at median costs, to $9.9 million, if you are looking at mean costs.

“The transition of appropriate breast cancer survivors to the community appears to be safe and effective outside of a clinical trial, at least based on this particular retrospective analysis using databases,” she said. “The overall costs are not increased, and they may actually be decreased based on our data, and certainly these results will inform policy.”

The investigators plan several next steps, such as encouraging senior leadership at Cancer Care Ontario and the Ministry of Health to endorse the findings, according to Dr. Mittmann. In addition, “[we plan to] engage with both oncology and primary care leadership and think about how we can potentially roll out a program like this, and develop tools, whether those are letters or information packages, and education, to … appropriately transition individuals.”

Considerations in interpreting the study’s findings include the quality of the matching of survivors, according to invited discussant Monika K. Krzyzanowska, MD, a medical oncologist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, an associate professor at the University of Toronto, and a clinical lead of Quality Care and Access, Systemic Treatment Program, at Cancer Care Ontario. “The quality of that match depends on what’s in the model, so there could be potential for residual confounding, and administrative data may not have all of the elements that you would need to get a perfect match.”

Additional considerations include costs not covered by the payer, impact of the initiative on delivery of guideline-recommended care and patient and provider satisfaction, generalizability of the findings, and long-term outcomes.

“This is a proof of concept, certainly, that transition of low-risk cancer survivors to primary care is feasible and potentially economically attractive,” Dr. Krzyzanowska concluded. “It would be useful to have a formal evaluation of effectiveness that would inform a comprehensive value assessment. And we do have data from a randomized trial about the safety of this particular approach, but it would be nice to see that following implementation in real practices, those safety considerations played out the same way.”

Comparison of survivorship care models

Two-thirds of the large and growing population of cancer survivors are at least 5 years out from diagnosis, stimulating considerable discussion in the oncology community about how to best address their needs, according to Sarah Raskin, PhD, senior author on the second study and a research scientist at the Institute for Patient-Centered Initiatives and Health Equity at George Washington University Cancer Center, Washington.

“Yet, for a lack of cancer survivorship–specific guidelines from research or practice, cancer centers are increasingly developing survivorship care in a variety of ways, many of which are ad hoc or unproven as yet,” she said.

Dr. Raskin and her colleagues compared three emerging models of survivorship care: a specialized consultative model and a specialized longitudinal model – whereby patients have a single or multiple formalized survivorship visits, respectively, with care typically led by an oncology nurse-practitioner – and an oncology-embedded model – whereby survivorship is addressed as a part of ongoing oncology follow-up care, typically by the oncologist.

The investigators worked with survivors to develop the Patient-Prioritized Measure of High-Quality Survivorship Care, a 46-question scale assessing nine components of survivorship care that capture the health care priorities and needs that matter most to patients. Each component is rated on a scale from 0 (not at all met) to 1 (somewhat met) to 2 (definitely met).

Analyses were based on responses of 827 survivors of breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer who received care at 28 U.S. institutions using one of the above models and who were surveyed by telephone about the care received 1 week after their initial survivorship visit.

Results showed that survivors cared for under the three models differed significantly with respect to scores for seven of the nine components of quality of care, Dr. Raskin reported. The exceptions were practical life support, where the mean score was about 0.6-0.8 across the board, and having a medical home, where the mean score was about 1.8-1.9 across the board.

The specialized consult model of care had the highest scores for mental health and social support, information and resources, and supportive and prepared clinicians. The specialized longitudinal model of care had the highest scores for empowered and engaged patients, open patient-clinician communication, care coordination and transitions, and access to full spectrum of care. The oncology-embedded model had the lowest scores. Analysis of the tool’s 46 individual questions showed that patients cared for at institutions using the oncology-embedded model were significantly less likely than were counterparts cared for at institutions using the specialized models to report that the institution performed various activities such as offering a treatment summary, inquiring about the patient’s biggest worries or problems, and explaining the reasons why tests were needed (P less than .05 for each).

For some metrics, the overall proportion reporting that an activity was performed was low, regardless of the model being used. For example, only 48% of all patients reported being helped to set goals or make short-term plans to manage follow-up care and improve health, merely 24% reported being provided emotional and social support to deal with changes in relationships, and just 19% reported being referred to special providers for other medical problems.

“Overall, all three models are performing highly in terms of providing survivors with a medical home and communicating with patients. However, all three are performing quite low in terms of providing mental health and social support, as well as practical life support,” said Dr. Raskin.

“By model, we see that the embedded ongoing care model is significantly underperforming compared with both specialized models on seven of nine components, and we have some hypotheses from our early work with [Commission on Cancer]–accredited centers to explain this,” she added. “Embedded survivorship models have a lot of variability – many are high performers but others are low performers as compared with specialized programs. Embedded survivorship care models are typically led by the treating oncologist, who historically has focused on treating sick patients and less so on providing social supports for follow-up of well patients or ‘well-er’ patients. At the same time, specialized models focus predominantly on survivorship care and providing services and referrals for survivors, which may explain their high scores.

“We know that the higher quality of care measures presented here do not necessarily translate to better patient outcomes, and that’s actually going to be the next phase of our analysis,” she concluded.

The study sample may have had some selection bias, and it is unclear how well validated the tool was, according to Dr. Krzyzanowska, the discussant. Another issue was its assessment of quality of care at only a single time point.

Nonetheless, the findings show “that measuring quality of survivorship care from a patient perspective is feasible and valuable. We have already heard about [need for] survivorship plans in survivorship care, so certainly the work that was just presented is extremely important to help to fill some of these gaps,” she said.

“I’m not sure that we yet know what the optimal model of survivorship care is without the information of the other outcomes. Furthermore, there’s different survivor populations and different ways that health care is organized, so perhaps there isn’t really one optimal model, but the model has to fit with the context,” Dr. Krzyzanowska concluded. “That being said … the tool that they have created can be a great tool for existing survivorship care programs to assess and improve the quality of their care.”

Dr. Mittmann and Dr. Raskin had no disclosures to report.

ORLANDO – Accumulating experience is showing the benefits of various models of care for cancer survivors in terms of health care use and costs, while also suggesting that some provide higher-quality care than others, according to a pair of studies reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Initiative for breast cancer survivors

“In 2011, Cancer Care Ontario did a quick environmental scan of our 14 regional cancer centers and found that the transition of breast cancer survivors from oncologists to primary care was very variable, and that centers often didn’t transition patients very frequently,” said Nicole Mittmann, PhD, first author on one of the studies, chief research officer for Cancer Care Ontario, and an investigator at Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto.

The advisory organization therefore implemented the Well Follow-Up Care Initiative to facilitate appropriate transition of breast cancer survivors. Each regional center was given a $100,000 incentive to roll out a model of the initiative.

Dr. Mittmann and her coinvestigators used provincial administrative databases to compare health care use and associated costs between 2,324 breast cancer survivors who were transitioned with the initiative and 2,324 propensity-matched control survivors who were not. The survivors were about 5 years out from their breast cancer diagnosis at baseline and had median follow-up of 2 years.

Study results reported at the symposium showed that the mean annual total cost of care per patient paid for by the provincial health ministry was $6,575 for the transitioned group and $10,832 for the nontransitioned group, a difference of $4,257 (39%). The main drivers were reduced costs of long-term care and cancer clinic visits.

Findings were similar for median annual costs, which amounted to $2,261 for the transitioned group and $2,903 for the control group, a difference of $638.

Compared with the nontransitioned group, the transitioned group had significantly fewer annual visits to medical oncologists (0.39 vs. 1.29) and radiation oncologists (0.16 vs. 0.36), while visits to general or family practitioners were statistically indistinguishable (7.35 and 7.91), Dr. Mittmann reported. There was also a trend toward fewer emergency department visits.

The transitioned group had fewer bone scans, CT and MRI scans, and radiographs annually, but differences were not significant.

Reassuringly, Dr. Mittmann said, survivors who were transitioned did not fare worse than their nontransitioned counterparts in overall survival; if anything, they tended to live longer. “We think that because the individual cancer centers enrolled patients that they thought were very well that this is a very well and highly selected and maybe a biased group,” Dr. Mittmann acknowledged. “But we certainly see that they are not doing worse than the control group.”

“About $1.4 million was distributed to the cancer centers” for the initiative, she noted. “That generated a savings for the health system of $1.5 million, if you are looking at median costs, to $9.9 million, if you are looking at mean costs.

“The transition of appropriate breast cancer survivors to the community appears to be safe and effective outside of a clinical trial, at least based on this particular retrospective analysis using databases,” she said. “The overall costs are not increased, and they may actually be decreased based on our data, and certainly these results will inform policy.”

The investigators plan several next steps, such as encouraging senior leadership at Cancer Care Ontario and the Ministry of Health to endorse the findings, according to Dr. Mittmann. In addition, “[we plan to] engage with both oncology and primary care leadership and think about how we can potentially roll out a program like this, and develop tools, whether those are letters or information packages, and education, to … appropriately transition individuals.”

Considerations in interpreting the study’s findings include the quality of the matching of survivors, according to invited discussant Monika K. Krzyzanowska, MD, a medical oncologist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, an associate professor at the University of Toronto, and a clinical lead of Quality Care and Access, Systemic Treatment Program, at Cancer Care Ontario. “The quality of that match depends on what’s in the model, so there could be potential for residual confounding, and administrative data may not have all of the elements that you would need to get a perfect match.”

Additional considerations include costs not covered by the payer, impact of the initiative on delivery of guideline-recommended care and patient and provider satisfaction, generalizability of the findings, and long-term outcomes.

“This is a proof of concept, certainly, that transition of low-risk cancer survivors to primary care is feasible and potentially economically attractive,” Dr. Krzyzanowska concluded. “It would be useful to have a formal evaluation of effectiveness that would inform a comprehensive value assessment. And we do have data from a randomized trial about the safety of this particular approach, but it would be nice to see that following implementation in real practices, those safety considerations played out the same way.”

Comparison of survivorship care models

Two-thirds of the large and growing population of cancer survivors are at least 5 years out from diagnosis, stimulating considerable discussion in the oncology community about how to best address their needs, according to Sarah Raskin, PhD, senior author on the second study and a research scientist at the Institute for Patient-Centered Initiatives and Health Equity at George Washington University Cancer Center, Washington.

“Yet, for a lack of cancer survivorship–specific guidelines from research or practice, cancer centers are increasingly developing survivorship care in a variety of ways, many of which are ad hoc or unproven as yet,” she said.

Dr. Raskin and her colleagues compared three emerging models of survivorship care: a specialized consultative model and a specialized longitudinal model – whereby patients have a single or multiple formalized survivorship visits, respectively, with care typically led by an oncology nurse-practitioner – and an oncology-embedded model – whereby survivorship is addressed as a part of ongoing oncology follow-up care, typically by the oncologist.

The investigators worked with survivors to develop the Patient-Prioritized Measure of High-Quality Survivorship Care, a 46-question scale assessing nine components of survivorship care that capture the health care priorities and needs that matter most to patients. Each component is rated on a scale from 0 (not at all met) to 1 (somewhat met) to 2 (definitely met).

Analyses were based on responses of 827 survivors of breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer who received care at 28 U.S. institutions using one of the above models and who were surveyed by telephone about the care received 1 week after their initial survivorship visit.

Results showed that survivors cared for under the three models differed significantly with respect to scores for seven of the nine components of quality of care, Dr. Raskin reported. The exceptions were practical life support, where the mean score was about 0.6-0.8 across the board, and having a medical home, where the mean score was about 1.8-1.9 across the board.

The specialized consult model of care had the highest scores for mental health and social support, information and resources, and supportive and prepared clinicians. The specialized longitudinal model of care had the highest scores for empowered and engaged patients, open patient-clinician communication, care coordination and transitions, and access to full spectrum of care. The oncology-embedded model had the lowest scores. Analysis of the tool’s 46 individual questions showed that patients cared for at institutions using the oncology-embedded model were significantly less likely than were counterparts cared for at institutions using the specialized models to report that the institution performed various activities such as offering a treatment summary, inquiring about the patient’s biggest worries or problems, and explaining the reasons why tests were needed (P less than .05 for each).

For some metrics, the overall proportion reporting that an activity was performed was low, regardless of the model being used. For example, only 48% of all patients reported being helped to set goals or make short-term plans to manage follow-up care and improve health, merely 24% reported being provided emotional and social support to deal with changes in relationships, and just 19% reported being referred to special providers for other medical problems.

“Overall, all three models are performing highly in terms of providing survivors with a medical home and communicating with patients. However, all three are performing quite low in terms of providing mental health and social support, as well as practical life support,” said Dr. Raskin.

“By model, we see that the embedded ongoing care model is significantly underperforming compared with both specialized models on seven of nine components, and we have some hypotheses from our early work with [Commission on Cancer]–accredited centers to explain this,” she added. “Embedded survivorship models have a lot of variability – many are high performers but others are low performers as compared with specialized programs. Embedded survivorship care models are typically led by the treating oncologist, who historically has focused on treating sick patients and less so on providing social supports for follow-up of well patients or ‘well-er’ patients. At the same time, specialized models focus predominantly on survivorship care and providing services and referrals for survivors, which may explain their high scores.

“We know that the higher quality of care measures presented here do not necessarily translate to better patient outcomes, and that’s actually going to be the next phase of our analysis,” she concluded.

The study sample may have had some selection bias, and it is unclear how well validated the tool was, according to Dr. Krzyzanowska, the discussant. Another issue was its assessment of quality of care at only a single time point.

Nonetheless, the findings show “that measuring quality of survivorship care from a patient perspective is feasible and valuable. We have already heard about [need for] survivorship plans in survivorship care, so certainly the work that was just presented is extremely important to help to fill some of these gaps,” she said.

“I’m not sure that we yet know what the optimal model of survivorship care is without the information of the other outcomes. Furthermore, there’s different survivor populations and different ways that health care is organized, so perhaps there isn’t really one optimal model, but the model has to fit with the context,” Dr. Krzyzanowska concluded. “That being said … the tool that they have created can be a great tool for existing survivorship care programs to assess and improve the quality of their care.”

Dr. Mittmann and Dr. Raskin had no disclosures to report.

AT THE QUALITY CARE SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Mean annual health care costs were $4,257 (39%) lower for breast cancer survivors actively transitioned to primary care versus control peers. Specialized consult and specialized longitudinal models outperformed an oncology-embedded model on seven quality metrics.

Data source: A cohort study of 2,324 breast cancer survivors transitioned to primary care and 2,324 not transitioned. A cohort study of 827 survivors of breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer receiving care under three differing models.

Disclosures: Dr. Mittmann and Dr. Raskin had no disclosures to report.

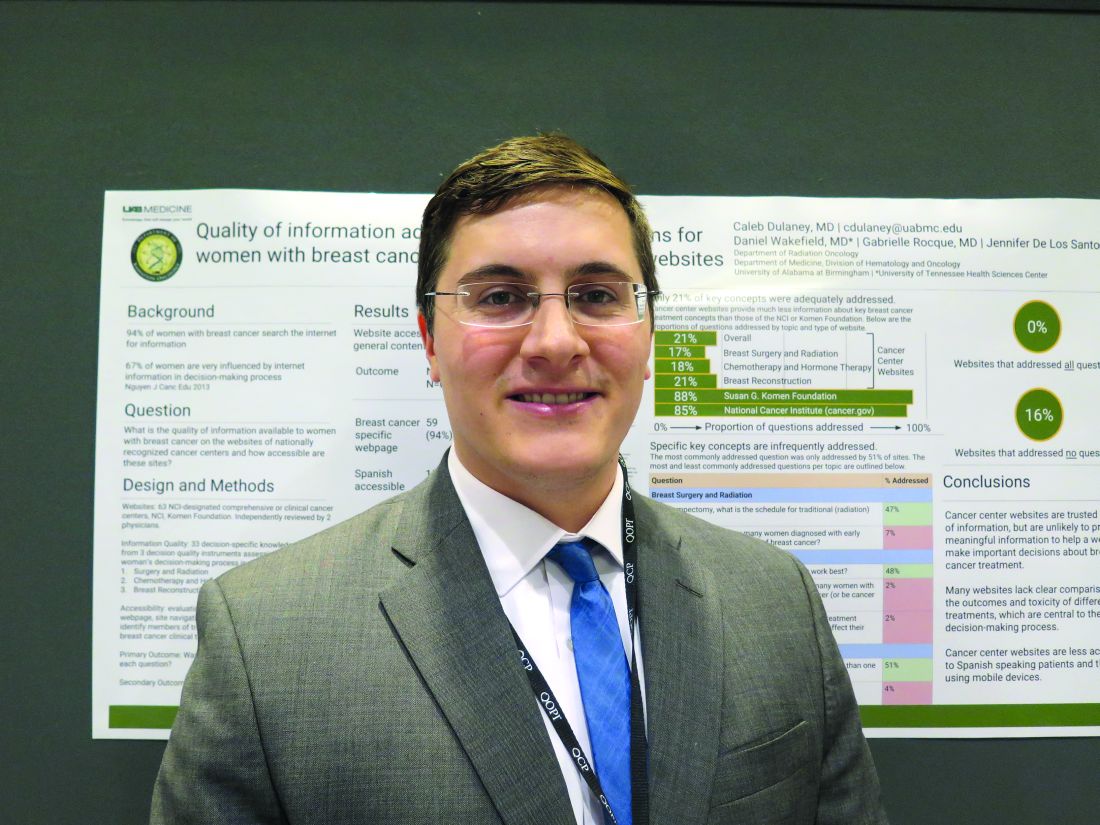

Breast cancer info on centers’ sites leaves room for improvement

ORLANDO – Women with breast cancer who look for well-rounded information about treatment on the websites of prominent U.S. cancer centers are likely to come up short, suggests a study presented at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Research has shown that nearly all women with breast cancer search the Internet for information about its treatment, and two-thirds report that what they find has a strong influence on their decision-making process (J Cancer Educ. 2013;28[4]:662-8).

But the analysis of content on the websites of 63 National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer centers or clinical cancer centers found that, on average, they addressed only 21% of a set of key concepts that women need to understand to make informed decisions about surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and breast reconstruction. This contrasted starkly with 85% for the National Cancer Institute’s own website (cancer.gov) and 88% for the Susan G. Komen Foundation’s website (komen.org).

“These are websites that we think are reliable, cancer center websites, and these are the most prominent cancer centers in the country,” first author Caleb Dulaney, MD, a resident in radiation oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in an interview. “This is where a lot of people receive their care, so they should be very reliable as to the information they provide.

“A lot of websites just had information from the NCI basically integrated into their website or a link to the NCI website,” he acknowledged. “Is it really the goal of the cancer center’s website to provide information? It may not be. But you have to take responsibility for being a trusted source of information. So if you are not going to provide it, you should at least direct people to very accurate, reliable information, and it can also kind of inform what you talk about in clinic.”

All of the investigators evaluating sites in the study were medical professionals, so the team has initiated a new study in which patients will instead perform the evaluations.

“We found that for a few websites, one person found a lot of information and another found no information. So the information may technically be there, but is it transmitted to the patient? Can they find it, and do they understand it?” Dr. Dulaney said. “So it will be interesting when we use patients to evaluate these websites. I’ll be curious to see how many questions they are able to find answers to.”

Study details

For the study, the investigators developed a list of 33 decision-specific knowledge questions about breast cancer treatment by drawing on decision quality instruments that assess how informed a woman’s decision-making process is. The primary outcome was whether the website provided sufficient information to answer each question. The researchers assessed seven measures of accessibility as secondary outcomes.

Results showed that websites contained sufficient content to address only 21% of the decision-specific knowledge questions, Dr. Dulaney reported in a poster session. The value was 17% for questions pertaining to breast surgery and radiation therapy, 18% for those pertaining to chemotherapy and hormone therapy, and 21% for those pertaining to breast reconstruction.

In addition, “a lot of websites put the information in silos,” he noted. “You can read about mastectomy, you can read about lumpectomy, you can read about chemo. But you can’t really get the big picture, which is how do these compare to each other, and which treatment is best for me.”

Even the most commonly addressed single question – what type of reconstruction is most likely to require more than one surgery or procedure – was addressed by only 51% of sites. Proportions were similar for questions pertaining to the type of tumors against which hormone therapy works best (48%) and the schedule for radiation therapy after lumpectomy (47%).

At the other extreme, however, very small proportions of sites addressed questions pertaining to how many women with treated early breast cancer will die from the disease (7%), how many undergoing breast reconstruction will experience complications requiring hospitalization or an unplanned procedure (4%), how skipping chemotherapy and hormone therapy influences risk of death (2%), and whether waiting several weeks to decide about those therapies affects survival (2%). These topics are more negative, Dr. Dulaney observed, “but these are things women need to know.”

None of the websites provided sufficient information to answer all 33 knowledge questions. But perhaps more worrisome, 16% did not provide sufficient information to answer any of them, he said.

When it came to accessibility of information, 94% of sites clearly had a breast cancer–specific page, 87% had information about breast cancer–specific trials, and 86% showed members of the center’s breast cancer team. But only 59% were mobile device friendly as assessed with a Google tool, and merely 24% had obvious links to view information in Spanish.

“A lot of minorities and people of lower socioeconomic status exclusively access the Internet via mobile devices, so they may not have a computer or [other] access to the Internet. But they have a cell phone that is probably a smartphone, and they can get online and search for information that way,” Dr. Dulaney said.

Many oncologists may not have had any say regarding the content and accessibility features of their institution’s website, he acknowledged.

“So we should maybe, number one, try to have more involvement in what information goes on to the website, and two, take a look at our own websites to see what’s on there, because patients are going to look for you, and they are going to associate this information with you,” he said. “If you are at a big institution and you really can’t make a change on your website, you can use alternatives such as social media platforms, things like that, to try and get information out to people.”

From a larger perspective, oncologists have often simply counseled patients that they can’t rely on information they have found online, according to Dr. Dulaney.

“But in this day and age, that can’t really be an answer,” he concluded. “Information on the web is ubiquitous, and there is good information out there. We need to do a better job of speaking up in the conversation. We have the answers to a lot of these questions, we just need to make our voices heard and also direct patients to reliable sources of information.”

ORLANDO – Women with breast cancer who look for well-rounded information about treatment on the websites of prominent U.S. cancer centers are likely to come up short, suggests a study presented at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Research has shown that nearly all women with breast cancer search the Internet for information about its treatment, and two-thirds report that what they find has a strong influence on their decision-making process (J Cancer Educ. 2013;28[4]:662-8).

But the analysis of content on the websites of 63 National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer centers or clinical cancer centers found that, on average, they addressed only 21% of a set of key concepts that women need to understand to make informed decisions about surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and breast reconstruction. This contrasted starkly with 85% for the National Cancer Institute’s own website (cancer.gov) and 88% for the Susan G. Komen Foundation’s website (komen.org).

“These are websites that we think are reliable, cancer center websites, and these are the most prominent cancer centers in the country,” first author Caleb Dulaney, MD, a resident in radiation oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in an interview. “This is where a lot of people receive their care, so they should be very reliable as to the information they provide.

“A lot of websites just had information from the NCI basically integrated into their website or a link to the NCI website,” he acknowledged. “Is it really the goal of the cancer center’s website to provide information? It may not be. But you have to take responsibility for being a trusted source of information. So if you are not going to provide it, you should at least direct people to very accurate, reliable information, and it can also kind of inform what you talk about in clinic.”

All of the investigators evaluating sites in the study were medical professionals, so the team has initiated a new study in which patients will instead perform the evaluations.

“We found that for a few websites, one person found a lot of information and another found no information. So the information may technically be there, but is it transmitted to the patient? Can they find it, and do they understand it?” Dr. Dulaney said. “So it will be interesting when we use patients to evaluate these websites. I’ll be curious to see how many questions they are able to find answers to.”

Study details