User login

University of California, San Francisco (UCSF): Antepartum and Intrapartum Management Meeting

Get umbilical artery systolic-to-diastolic ratio in intrauterine growth restriction

SAN FRANCISCO – An umbilical artery systolic-to-diastolic ratio of less than 3 as measured on weekly Doppler ultrasounds in a fetus with 30 weeks’ or more gestation and suspected intrauterine growth restriction suggests that the fetus probably is doing okay, Dr. Vickie A. Feldstein said.

That "ballpark guideline" is most helpful if physicians at your institution have agreed to use the umbilical artery systolic/diastolic (S/D) ratio as the parameter for assessing fetuses with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and have agreed on which anatomical location is preferred for the ultrasound interrogation, so that there is some uniformity in how results are presented and interpreted, she said.

The recent Practice Bulletin No. 134 from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended in May 2013 that if the ultrasonographically estimated fetal weight is below the 10th percentile for gestational age, further evaluation should be considered, such as Doppler blood flow studies of the umbilical artery (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:1122-33).

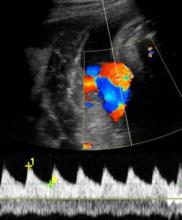

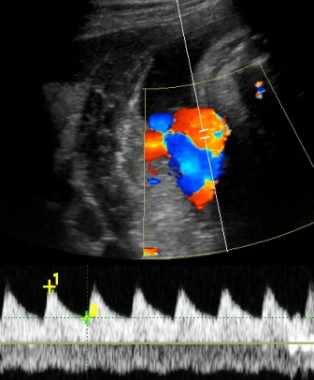

The medical literature describes several Doppler ultrasound parameters that could be used in suspected IUGR, including the umbilical artery S/D ratio, the resistance index, or the pulsatility index. They’re all about the same phenomenon, which is measuring resistance to perfusion in the placenta as reflected in the interrogation of the umbilical artery, Dr. Feldstein said at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco.

"I think a report that includes all of them would make our heads spin," said Dr. Feldstein, professor of clinical radiology at the university. She and her colleagues use the S/D ratio, calculated by using calipers to measure the peak of systole on umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound and dividing that by the measure of end diastole.

"I don’t care how fast the flow actually is, I care about the character of the flow, the relative difference between systole and diastole," she said. The ratio reflects the status of placental circulation. It normally is high early in pregnancy and decreases as gestation advances, placental resistance decreases, and there is more forward flow during diastole.

If separate umbilical artery Doppler tracings yield discrepant S/D ratios, that may reflect normal variability or be due to changes in fetal heart rate. "A significant change in heart rate might change the S/D ratio quite a bit," she said. Or, an ultrasound filter set too low can produce noise in the tracing that might alter where you place the calipers.

The location along the umbilical cord that the sonographer samples also can affect measurements. The medical literature is full of suggestions about where to sample. Dr. Feldstein recommends sampling toward the placenta, if possible, which will reflect resistance to perfusion in the placenta.

"We’ve found the cord insertion, typically, so we know where to look," she said. "The farther away from the placenta you go, you’re adding resistance of the cord to your tracing."

She encouraged obstetricians to talk to the people who do Doppler at their institutions "to decide together how you want this done, how you want it reported, and what parameter you want used, so you don’t overwhelm yourselves with excess information."

If the S/D ratio is a bit above 3 in a third-trimester fetus with IUGR but there’s decent diastolic flow, "don’t sweat the small stuff," she suggested. As the S/D ratio goes higher and higher, however, placental insufficiency (and resistance) increases and forward flow decreases, and can become absent or even reversed end-diastolic flow.

An absence of diastolic flow is associated with a 60%-70% loss of vasculature, "a really significant abnormality in the placenta," she said. With reversed diastolic flow, the odds of perinatal death increase more than fivefold.

A recent study of 1,116 fetuses with IUGR showed that an abnormal umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound tracing (defined by pulsatility index or the absence or reversal of end-diastolic flow) was significantly associated with adverse outcomes irrespective of estimated fetal weight or abdominal circumference (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;208:e1-6 [doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.007]).

When Dr. Feldstein sees an abnormal umbilical artery Doppler tracing, she samples the fetal middle cerebral artery by Doppler ultrasound. The middle cerebral artery S/D ratio should always be higher than the umbilical artery SD ratio, with a typical middle cerebral artery S/D ratio greater than 4 after 30 weeks’ gestation.

A fetus in trouble with IUGR will respond by lowering cerebral vascular resistance to maintain blood flow to its brain, decreasing the middle cerebral artery S/D ratio in what’s known as a "brain-sparing" wave form. Although there’s nothing that can be done for the fetus at this point, she said, it can be helpful to know that brain-sparing in growth-restricted fetuses was associated with increased risk for abnormal neurobehavioral outcomes in a controlled study of 126 preterm infants (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;38:288-94).

"It’s a sign of distress," she said. Until recently, clinicians would follow that fetus carefully with various kinds of testing and watch for reverse diastolic flow in the umbilical artery, which is a sign of significant compromise, hypoxemia, and possible death. Today, a finding of brain-sparing next leads Dr. Feldstein to interrogate the ductus venosus in the liver, which is "the hardest to do, but it can be done," she said.

The ductus venosus flow should be phasic but continuous, in a pattern called the "a wave" reflecting forward, continuous flow even during right atrial contractions. If the flow reverses backward into the ductus venosus during right atrial contractions, that’s a sign of cardiac compromise, severe hypoxia, and right ventricular dysfunction, associated with high risk of morbidity and mortality.

Locating the ductus venosus for sampling can be tricky, in part because it is so close to hepatic veins, but if the ductus venosus flow is abnormal enough, there’s a shortcut that is easier to do: Sample the umbilical vein. Abnormal phasicity in umbilical vein pulsation may reflect ductus venosus flow reversal.

A previous study reported that the risk for perinatal mortality increased to nearly 6% with an elevated umbilical artery S/D ratio, to more than 11% with absent or reversed diastolic flow in the uterine artery, and to 39% with an abnormal ductus venosus wave form (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;22:240-5). In a 2010 Cochrane Review of 18 studies that included more than 10,000 women with high-risk pregnancies, Doppler ultrasound was associated with a 29% reduction in the rate of perinatal deaths (1.2% with Doppler and 1.7% without); analysis showed that using Doppler on 203 high-risk pregnancies would avoid 1 perinatal death (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 Jan. 20). "So, there’s a significant impact and not that much excess work," Dr. Feldstein said.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – An umbilical artery systolic-to-diastolic ratio of less than 3 as measured on weekly Doppler ultrasounds in a fetus with 30 weeks’ or more gestation and suspected intrauterine growth restriction suggests that the fetus probably is doing okay, Dr. Vickie A. Feldstein said.

That "ballpark guideline" is most helpful if physicians at your institution have agreed to use the umbilical artery systolic/diastolic (S/D) ratio as the parameter for assessing fetuses with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and have agreed on which anatomical location is preferred for the ultrasound interrogation, so that there is some uniformity in how results are presented and interpreted, she said.

The recent Practice Bulletin No. 134 from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended in May 2013 that if the ultrasonographically estimated fetal weight is below the 10th percentile for gestational age, further evaluation should be considered, such as Doppler blood flow studies of the umbilical artery (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:1122-33).

The medical literature describes several Doppler ultrasound parameters that could be used in suspected IUGR, including the umbilical artery S/D ratio, the resistance index, or the pulsatility index. They’re all about the same phenomenon, which is measuring resistance to perfusion in the placenta as reflected in the interrogation of the umbilical artery, Dr. Feldstein said at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco.

"I think a report that includes all of them would make our heads spin," said Dr. Feldstein, professor of clinical radiology at the university. She and her colleagues use the S/D ratio, calculated by using calipers to measure the peak of systole on umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound and dividing that by the measure of end diastole.

"I don’t care how fast the flow actually is, I care about the character of the flow, the relative difference between systole and diastole," she said. The ratio reflects the status of placental circulation. It normally is high early in pregnancy and decreases as gestation advances, placental resistance decreases, and there is more forward flow during diastole.

If separate umbilical artery Doppler tracings yield discrepant S/D ratios, that may reflect normal variability or be due to changes in fetal heart rate. "A significant change in heart rate might change the S/D ratio quite a bit," she said. Or, an ultrasound filter set too low can produce noise in the tracing that might alter where you place the calipers.

The location along the umbilical cord that the sonographer samples also can affect measurements. The medical literature is full of suggestions about where to sample. Dr. Feldstein recommends sampling toward the placenta, if possible, which will reflect resistance to perfusion in the placenta.

"We’ve found the cord insertion, typically, so we know where to look," she said. "The farther away from the placenta you go, you’re adding resistance of the cord to your tracing."

She encouraged obstetricians to talk to the people who do Doppler at their institutions "to decide together how you want this done, how you want it reported, and what parameter you want used, so you don’t overwhelm yourselves with excess information."

If the S/D ratio is a bit above 3 in a third-trimester fetus with IUGR but there’s decent diastolic flow, "don’t sweat the small stuff," she suggested. As the S/D ratio goes higher and higher, however, placental insufficiency (and resistance) increases and forward flow decreases, and can become absent or even reversed end-diastolic flow.

An absence of diastolic flow is associated with a 60%-70% loss of vasculature, "a really significant abnormality in the placenta," she said. With reversed diastolic flow, the odds of perinatal death increase more than fivefold.

A recent study of 1,116 fetuses with IUGR showed that an abnormal umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound tracing (defined by pulsatility index or the absence or reversal of end-diastolic flow) was significantly associated with adverse outcomes irrespective of estimated fetal weight or abdominal circumference (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;208:e1-6 [doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.007]).

When Dr. Feldstein sees an abnormal umbilical artery Doppler tracing, she samples the fetal middle cerebral artery by Doppler ultrasound. The middle cerebral artery S/D ratio should always be higher than the umbilical artery SD ratio, with a typical middle cerebral artery S/D ratio greater than 4 after 30 weeks’ gestation.

A fetus in trouble with IUGR will respond by lowering cerebral vascular resistance to maintain blood flow to its brain, decreasing the middle cerebral artery S/D ratio in what’s known as a "brain-sparing" wave form. Although there’s nothing that can be done for the fetus at this point, she said, it can be helpful to know that brain-sparing in growth-restricted fetuses was associated with increased risk for abnormal neurobehavioral outcomes in a controlled study of 126 preterm infants (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;38:288-94).

"It’s a sign of distress," she said. Until recently, clinicians would follow that fetus carefully with various kinds of testing and watch for reverse diastolic flow in the umbilical artery, which is a sign of significant compromise, hypoxemia, and possible death. Today, a finding of brain-sparing next leads Dr. Feldstein to interrogate the ductus venosus in the liver, which is "the hardest to do, but it can be done," she said.

The ductus venosus flow should be phasic but continuous, in a pattern called the "a wave" reflecting forward, continuous flow even during right atrial contractions. If the flow reverses backward into the ductus venosus during right atrial contractions, that’s a sign of cardiac compromise, severe hypoxia, and right ventricular dysfunction, associated with high risk of morbidity and mortality.

Locating the ductus venosus for sampling can be tricky, in part because it is so close to hepatic veins, but if the ductus venosus flow is abnormal enough, there’s a shortcut that is easier to do: Sample the umbilical vein. Abnormal phasicity in umbilical vein pulsation may reflect ductus venosus flow reversal.

A previous study reported that the risk for perinatal mortality increased to nearly 6% with an elevated umbilical artery S/D ratio, to more than 11% with absent or reversed diastolic flow in the uterine artery, and to 39% with an abnormal ductus venosus wave form (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;22:240-5). In a 2010 Cochrane Review of 18 studies that included more than 10,000 women with high-risk pregnancies, Doppler ultrasound was associated with a 29% reduction in the rate of perinatal deaths (1.2% with Doppler and 1.7% without); analysis showed that using Doppler on 203 high-risk pregnancies would avoid 1 perinatal death (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 Jan. 20). "So, there’s a significant impact and not that much excess work," Dr. Feldstein said.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – An umbilical artery systolic-to-diastolic ratio of less than 3 as measured on weekly Doppler ultrasounds in a fetus with 30 weeks’ or more gestation and suspected intrauterine growth restriction suggests that the fetus probably is doing okay, Dr. Vickie A. Feldstein said.

That "ballpark guideline" is most helpful if physicians at your institution have agreed to use the umbilical artery systolic/diastolic (S/D) ratio as the parameter for assessing fetuses with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and have agreed on which anatomical location is preferred for the ultrasound interrogation, so that there is some uniformity in how results are presented and interpreted, she said.

The recent Practice Bulletin No. 134 from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended in May 2013 that if the ultrasonographically estimated fetal weight is below the 10th percentile for gestational age, further evaluation should be considered, such as Doppler blood flow studies of the umbilical artery (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:1122-33).

The medical literature describes several Doppler ultrasound parameters that could be used in suspected IUGR, including the umbilical artery S/D ratio, the resistance index, or the pulsatility index. They’re all about the same phenomenon, which is measuring resistance to perfusion in the placenta as reflected in the interrogation of the umbilical artery, Dr. Feldstein said at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco.

"I think a report that includes all of them would make our heads spin," said Dr. Feldstein, professor of clinical radiology at the university. She and her colleagues use the S/D ratio, calculated by using calipers to measure the peak of systole on umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound and dividing that by the measure of end diastole.

"I don’t care how fast the flow actually is, I care about the character of the flow, the relative difference between systole and diastole," she said. The ratio reflects the status of placental circulation. It normally is high early in pregnancy and decreases as gestation advances, placental resistance decreases, and there is more forward flow during diastole.

If separate umbilical artery Doppler tracings yield discrepant S/D ratios, that may reflect normal variability or be due to changes in fetal heart rate. "A significant change in heart rate might change the S/D ratio quite a bit," she said. Or, an ultrasound filter set too low can produce noise in the tracing that might alter where you place the calipers.

The location along the umbilical cord that the sonographer samples also can affect measurements. The medical literature is full of suggestions about where to sample. Dr. Feldstein recommends sampling toward the placenta, if possible, which will reflect resistance to perfusion in the placenta.

"We’ve found the cord insertion, typically, so we know where to look," she said. "The farther away from the placenta you go, you’re adding resistance of the cord to your tracing."

She encouraged obstetricians to talk to the people who do Doppler at their institutions "to decide together how you want this done, how you want it reported, and what parameter you want used, so you don’t overwhelm yourselves with excess information."

If the S/D ratio is a bit above 3 in a third-trimester fetus with IUGR but there’s decent diastolic flow, "don’t sweat the small stuff," she suggested. As the S/D ratio goes higher and higher, however, placental insufficiency (and resistance) increases and forward flow decreases, and can become absent or even reversed end-diastolic flow.

An absence of diastolic flow is associated with a 60%-70% loss of vasculature, "a really significant abnormality in the placenta," she said. With reversed diastolic flow, the odds of perinatal death increase more than fivefold.

A recent study of 1,116 fetuses with IUGR showed that an abnormal umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound tracing (defined by pulsatility index or the absence or reversal of end-diastolic flow) was significantly associated with adverse outcomes irrespective of estimated fetal weight or abdominal circumference (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;208:e1-6 [doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.007]).

When Dr. Feldstein sees an abnormal umbilical artery Doppler tracing, she samples the fetal middle cerebral artery by Doppler ultrasound. The middle cerebral artery S/D ratio should always be higher than the umbilical artery SD ratio, with a typical middle cerebral artery S/D ratio greater than 4 after 30 weeks’ gestation.

A fetus in trouble with IUGR will respond by lowering cerebral vascular resistance to maintain blood flow to its brain, decreasing the middle cerebral artery S/D ratio in what’s known as a "brain-sparing" wave form. Although there’s nothing that can be done for the fetus at this point, she said, it can be helpful to know that brain-sparing in growth-restricted fetuses was associated with increased risk for abnormal neurobehavioral outcomes in a controlled study of 126 preterm infants (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;38:288-94).

"It’s a sign of distress," she said. Until recently, clinicians would follow that fetus carefully with various kinds of testing and watch for reverse diastolic flow in the umbilical artery, which is a sign of significant compromise, hypoxemia, and possible death. Today, a finding of brain-sparing next leads Dr. Feldstein to interrogate the ductus venosus in the liver, which is "the hardest to do, but it can be done," she said.

The ductus venosus flow should be phasic but continuous, in a pattern called the "a wave" reflecting forward, continuous flow even during right atrial contractions. If the flow reverses backward into the ductus venosus during right atrial contractions, that’s a sign of cardiac compromise, severe hypoxia, and right ventricular dysfunction, associated with high risk of morbidity and mortality.

Locating the ductus venosus for sampling can be tricky, in part because it is so close to hepatic veins, but if the ductus venosus flow is abnormal enough, there’s a shortcut that is easier to do: Sample the umbilical vein. Abnormal phasicity in umbilical vein pulsation may reflect ductus venosus flow reversal.

A previous study reported that the risk for perinatal mortality increased to nearly 6% with an elevated umbilical artery S/D ratio, to more than 11% with absent or reversed diastolic flow in the uterine artery, and to 39% with an abnormal ductus venosus wave form (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;22:240-5). In a 2010 Cochrane Review of 18 studies that included more than 10,000 women with high-risk pregnancies, Doppler ultrasound was associated with a 29% reduction in the rate of perinatal deaths (1.2% with Doppler and 1.7% without); analysis showed that using Doppler on 203 high-risk pregnancies would avoid 1 perinatal death (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 Jan. 20). "So, there’s a significant impact and not that much excess work," Dr. Feldstein said.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @sherryboschert

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING ON ANTEPARTUM AND INTRAPARTUM MANAGEMENT

Identify monochorionic twins to guide pregnancy management

SAN FRANCISCO – The physician is responsible for knowing the chorionicity of a pregnant patient’s twins, so if you don’t offer diagnostic ultrasound or can’t make the diagnosis yourself, refer the patient to someone who can.

Knowing the chorionicity is essential because "it literally will define how you manage the pregnancy," Dr. Larry Rand said at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco.

"This is a critical, critical concept," said Dr. Rand, director of perinatal services for the Fetal Treatment Program at the university. The chorionicity "should be the very first question that you ask yourself when you have a patient with twins."

You don’t need to be an expert on monochorionic twins; you just need to know if the patient is at high risk because of monochorionicity. Determining the chorionicity of twins before 14 weeks’ gestation is considered the standard of care, he stressed, and a physician who doesn’t know that twins are monochorionic could be liable if something goes wrong.

If the chorionicity is undetermined on your office ultrasound, refer the patient and request a chorionicity determination, he advised.

"This is one of the times that I have to say that ultrasound makes all the difference," Dr. Rand said. "The single most important ultrasound finding in the entire pregnancy is going to be the chorionicity."

A patient deserves to know whether her twins are monochorionic because she needs to be counseled appropriately about the risks. "It’s not the radiologist’s responsibility," he said. "The obstetrician is responsible for knowing the effect of chorionicity." Make sure to document that you have either determined the chorionicity yourself or have asked for an exam to assess chorionicity.

The rate of congenital anomalies in monochorionic twins, for example, is similar to the rate seen in diabetic mothers. This "changes the kind of tests you order and the things you see" compared with dichorionic twins, he said. Level II ultrasound examinations of anatomy that would be done in high-risk cases such as diabetic pregnancies, for example, should be done for monochorionic twins, whose elevated risk for anomalies may be due to an imperfect splitting of the single egg from which they came.

Compared with dichorionic twins, monochorionic twins also have increased risk for neurologic injury, including an eightfold increased incidence of cerebral palsy, and for preterm birth, spontaneous abortion, intrauterine growth restriction and growth discordance, intrauterine fetal demise, and twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. Specialized centers can treat twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome with laser therapy if patients are diagnosed and referred in a timely manner – which is the reason for more-frequent screening of monochorionic twins. (See management recommendations below.)

Aterio-arterial (AA) anastomosis, a type of vascular connection within the placenta, can be detected on antenatal ultrasound. If present, the risk of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome decreases 10-fold and the risk of intrauterine fetal demise decreases sevenfold. "It’s very helpful prognostically," he said.

Although AA anastomosis is not a new concept, it’s only recently that obstetrical imaging has evolved to identify it on antenatal ultrasound, which is "so helpful for counseling and management," said Dr. Rand, also the Lynne and Marc Benioff Endowed Chair in Maternal and Fetal Medicine at the university.

The major fear in monochorionic twins is intrauterine fetal demise of one twin, which leaves the surviving twin with a 10%-20% risk of death and a 20%-40% risk of long-term neurologic injury if the second twin survives. The difference even comes into play with genetic counseling. Aneuploidy risk in monochorionic twins is similar to risk in singletons (because they originated from a single egg). For invasive testing, one chorionic villus sampling covers both monochorionic twins (because there’s only one placenta to sample), but amniocentesis typically is performed on each amniotic sac. Some physicians sample just one amniotic sac for amniocentesis, thinking that it should cover both twins because they’re identical, but there are extremely rare cases of subtle differences that would not be detected by single-sac sampling, he said.

The other outcomes differ between monochorionic and dichorionic twins because the splitting of an egg can be imperfect; monochorionic twins share "plumbing" and vascular connections, and they have to share the resources of one placenta, Dr. Rand explained.

Before 14 weeks’ gestation, ultrasound is 99% sensitive and 100% specific for chorionicity, and it’s an easy assessment to do. In the second trimester, it gets trickier, which is why determining chorionicity early is so important, he said.

Dr. Rand gave several recommendations for management of monochorionic twins. In the first trimester, he said, determine the chorionicity, check the nuchal translucency, and assess fetal growth.

In the second trimester, conduct level II (high risk) anatomical surveys and echocardiograms to screen for fetal cardiac disease (as you would in a diabetic mother). Establish a minimum surveillance schedule of at least every 2 weeks for amniotic fluid between 16 and 28 weeks’ gestation, and every 4 weeks for fetal growth between 16 and 32 weeks’ gestation.

In the third trimester, continue the surveillance of amniotic fluid and fetal growth. Consider performing non–stress tests and Doppler ultrasounds. There’s debate about the optimal gestational age for delivery of monochorionic twins, between 36 and 38 weeks. "We’re not sure when to deliver," Dr. Rand said, but he recommends delivering monochorionic twins who’ve had issues with growth, fluid, or other aspects during pregnancy closer to 36 weeks and delivering twins with no issues closer to 38 weeks. "Monochorionicity is not, in and of itself, an indication for cesarean delivery," he added.

Approximately 75% of twins are dizygotic (from two separate eggs, each fertilized by sperm) and thus dichorionic. Among the 25% of twin pregnancies that are monozygotic (from one egg), the egg splits more slowly in 75% of cases, creating monochorionic twins that share a placenta and circulation. In the other 25% of monozygotic twins, the egg splits quickly, within 3 days, yielding two separate units and creating dichorionic twins, each with their own placenta.

Dr. Rand reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – The physician is responsible for knowing the chorionicity of a pregnant patient’s twins, so if you don’t offer diagnostic ultrasound or can’t make the diagnosis yourself, refer the patient to someone who can.

Knowing the chorionicity is essential because "it literally will define how you manage the pregnancy," Dr. Larry Rand said at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco.

"This is a critical, critical concept," said Dr. Rand, director of perinatal services for the Fetal Treatment Program at the university. The chorionicity "should be the very first question that you ask yourself when you have a patient with twins."

You don’t need to be an expert on monochorionic twins; you just need to know if the patient is at high risk because of monochorionicity. Determining the chorionicity of twins before 14 weeks’ gestation is considered the standard of care, he stressed, and a physician who doesn’t know that twins are monochorionic could be liable if something goes wrong.

If the chorionicity is undetermined on your office ultrasound, refer the patient and request a chorionicity determination, he advised.

"This is one of the times that I have to say that ultrasound makes all the difference," Dr. Rand said. "The single most important ultrasound finding in the entire pregnancy is going to be the chorionicity."

A patient deserves to know whether her twins are monochorionic because she needs to be counseled appropriately about the risks. "It’s not the radiologist’s responsibility," he said. "The obstetrician is responsible for knowing the effect of chorionicity." Make sure to document that you have either determined the chorionicity yourself or have asked for an exam to assess chorionicity.

The rate of congenital anomalies in monochorionic twins, for example, is similar to the rate seen in diabetic mothers. This "changes the kind of tests you order and the things you see" compared with dichorionic twins, he said. Level II ultrasound examinations of anatomy that would be done in high-risk cases such as diabetic pregnancies, for example, should be done for monochorionic twins, whose elevated risk for anomalies may be due to an imperfect splitting of the single egg from which they came.

Compared with dichorionic twins, monochorionic twins also have increased risk for neurologic injury, including an eightfold increased incidence of cerebral palsy, and for preterm birth, spontaneous abortion, intrauterine growth restriction and growth discordance, intrauterine fetal demise, and twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. Specialized centers can treat twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome with laser therapy if patients are diagnosed and referred in a timely manner – which is the reason for more-frequent screening of monochorionic twins. (See management recommendations below.)

Aterio-arterial (AA) anastomosis, a type of vascular connection within the placenta, can be detected on antenatal ultrasound. If present, the risk of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome decreases 10-fold and the risk of intrauterine fetal demise decreases sevenfold. "It’s very helpful prognostically," he said.

Although AA anastomosis is not a new concept, it’s only recently that obstetrical imaging has evolved to identify it on antenatal ultrasound, which is "so helpful for counseling and management," said Dr. Rand, also the Lynne and Marc Benioff Endowed Chair in Maternal and Fetal Medicine at the university.

The major fear in monochorionic twins is intrauterine fetal demise of one twin, which leaves the surviving twin with a 10%-20% risk of death and a 20%-40% risk of long-term neurologic injury if the second twin survives. The difference even comes into play with genetic counseling. Aneuploidy risk in monochorionic twins is similar to risk in singletons (because they originated from a single egg). For invasive testing, one chorionic villus sampling covers both monochorionic twins (because there’s only one placenta to sample), but amniocentesis typically is performed on each amniotic sac. Some physicians sample just one amniotic sac for amniocentesis, thinking that it should cover both twins because they’re identical, but there are extremely rare cases of subtle differences that would not be detected by single-sac sampling, he said.

The other outcomes differ between monochorionic and dichorionic twins because the splitting of an egg can be imperfect; monochorionic twins share "plumbing" and vascular connections, and they have to share the resources of one placenta, Dr. Rand explained.

Before 14 weeks’ gestation, ultrasound is 99% sensitive and 100% specific for chorionicity, and it’s an easy assessment to do. In the second trimester, it gets trickier, which is why determining chorionicity early is so important, he said.

Dr. Rand gave several recommendations for management of monochorionic twins. In the first trimester, he said, determine the chorionicity, check the nuchal translucency, and assess fetal growth.

In the second trimester, conduct level II (high risk) anatomical surveys and echocardiograms to screen for fetal cardiac disease (as you would in a diabetic mother). Establish a minimum surveillance schedule of at least every 2 weeks for amniotic fluid between 16 and 28 weeks’ gestation, and every 4 weeks for fetal growth between 16 and 32 weeks’ gestation.

In the third trimester, continue the surveillance of amniotic fluid and fetal growth. Consider performing non–stress tests and Doppler ultrasounds. There’s debate about the optimal gestational age for delivery of monochorionic twins, between 36 and 38 weeks. "We’re not sure when to deliver," Dr. Rand said, but he recommends delivering monochorionic twins who’ve had issues with growth, fluid, or other aspects during pregnancy closer to 36 weeks and delivering twins with no issues closer to 38 weeks. "Monochorionicity is not, in and of itself, an indication for cesarean delivery," he added.

Approximately 75% of twins are dizygotic (from two separate eggs, each fertilized by sperm) and thus dichorionic. Among the 25% of twin pregnancies that are monozygotic (from one egg), the egg splits more slowly in 75% of cases, creating monochorionic twins that share a placenta and circulation. In the other 25% of monozygotic twins, the egg splits quickly, within 3 days, yielding two separate units and creating dichorionic twins, each with their own placenta.

Dr. Rand reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – The physician is responsible for knowing the chorionicity of a pregnant patient’s twins, so if you don’t offer diagnostic ultrasound or can’t make the diagnosis yourself, refer the patient to someone who can.

Knowing the chorionicity is essential because "it literally will define how you manage the pregnancy," Dr. Larry Rand said at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco.

"This is a critical, critical concept," said Dr. Rand, director of perinatal services for the Fetal Treatment Program at the university. The chorionicity "should be the very first question that you ask yourself when you have a patient with twins."

You don’t need to be an expert on monochorionic twins; you just need to know if the patient is at high risk because of monochorionicity. Determining the chorionicity of twins before 14 weeks’ gestation is considered the standard of care, he stressed, and a physician who doesn’t know that twins are monochorionic could be liable if something goes wrong.

If the chorionicity is undetermined on your office ultrasound, refer the patient and request a chorionicity determination, he advised.

"This is one of the times that I have to say that ultrasound makes all the difference," Dr. Rand said. "The single most important ultrasound finding in the entire pregnancy is going to be the chorionicity."

A patient deserves to know whether her twins are monochorionic because she needs to be counseled appropriately about the risks. "It’s not the radiologist’s responsibility," he said. "The obstetrician is responsible for knowing the effect of chorionicity." Make sure to document that you have either determined the chorionicity yourself or have asked for an exam to assess chorionicity.

The rate of congenital anomalies in monochorionic twins, for example, is similar to the rate seen in diabetic mothers. This "changes the kind of tests you order and the things you see" compared with dichorionic twins, he said. Level II ultrasound examinations of anatomy that would be done in high-risk cases such as diabetic pregnancies, for example, should be done for monochorionic twins, whose elevated risk for anomalies may be due to an imperfect splitting of the single egg from which they came.

Compared with dichorionic twins, monochorionic twins also have increased risk for neurologic injury, including an eightfold increased incidence of cerebral palsy, and for preterm birth, spontaneous abortion, intrauterine growth restriction and growth discordance, intrauterine fetal demise, and twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. Specialized centers can treat twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome with laser therapy if patients are diagnosed and referred in a timely manner – which is the reason for more-frequent screening of monochorionic twins. (See management recommendations below.)

Aterio-arterial (AA) anastomosis, a type of vascular connection within the placenta, can be detected on antenatal ultrasound. If present, the risk of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome decreases 10-fold and the risk of intrauterine fetal demise decreases sevenfold. "It’s very helpful prognostically," he said.

Although AA anastomosis is not a new concept, it’s only recently that obstetrical imaging has evolved to identify it on antenatal ultrasound, which is "so helpful for counseling and management," said Dr. Rand, also the Lynne and Marc Benioff Endowed Chair in Maternal and Fetal Medicine at the university.

The major fear in monochorionic twins is intrauterine fetal demise of one twin, which leaves the surviving twin with a 10%-20% risk of death and a 20%-40% risk of long-term neurologic injury if the second twin survives. The difference even comes into play with genetic counseling. Aneuploidy risk in monochorionic twins is similar to risk in singletons (because they originated from a single egg). For invasive testing, one chorionic villus sampling covers both monochorionic twins (because there’s only one placenta to sample), but amniocentesis typically is performed on each amniotic sac. Some physicians sample just one amniotic sac for amniocentesis, thinking that it should cover both twins because they’re identical, but there are extremely rare cases of subtle differences that would not be detected by single-sac sampling, he said.

The other outcomes differ between monochorionic and dichorionic twins because the splitting of an egg can be imperfect; monochorionic twins share "plumbing" and vascular connections, and they have to share the resources of one placenta, Dr. Rand explained.

Before 14 weeks’ gestation, ultrasound is 99% sensitive and 100% specific for chorionicity, and it’s an easy assessment to do. In the second trimester, it gets trickier, which is why determining chorionicity early is so important, he said.

Dr. Rand gave several recommendations for management of monochorionic twins. In the first trimester, he said, determine the chorionicity, check the nuchal translucency, and assess fetal growth.

In the second trimester, conduct level II (high risk) anatomical surveys and echocardiograms to screen for fetal cardiac disease (as you would in a diabetic mother). Establish a minimum surveillance schedule of at least every 2 weeks for amniotic fluid between 16 and 28 weeks’ gestation, and every 4 weeks for fetal growth between 16 and 32 weeks’ gestation.

In the third trimester, continue the surveillance of amniotic fluid and fetal growth. Consider performing non–stress tests and Doppler ultrasounds. There’s debate about the optimal gestational age for delivery of monochorionic twins, between 36 and 38 weeks. "We’re not sure when to deliver," Dr. Rand said, but he recommends delivering monochorionic twins who’ve had issues with growth, fluid, or other aspects during pregnancy closer to 36 weeks and delivering twins with no issues closer to 38 weeks. "Monochorionicity is not, in and of itself, an indication for cesarean delivery," he added.

Approximately 75% of twins are dizygotic (from two separate eggs, each fertilized by sperm) and thus dichorionic. Among the 25% of twin pregnancies that are monozygotic (from one egg), the egg splits more slowly in 75% of cases, creating monochorionic twins that share a placenta and circulation. In the other 25% of monozygotic twins, the egg splits quickly, within 3 days, yielding two separate units and creating dichorionic twins, each with their own placenta.

Dr. Rand reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING ON ANTEPARTUM AND INTRAPARTUM MANAGEMENT

Noninvasive prenatal testing could be secondary screen

SAN FRANCISCO – Using noninvasive prenatal DNA testing as a secondary screen after conventional prenatal testing could decrease the number of amniocenteses by more than 90%, reduce fetal losses, and improve the ratio of Down syndrome cases detected per amniocentesis, according to Dr. Mary E. Norton.

On the other hand, using noninvasive prenatal testing as the primary screen would increase the rate of detecting trisomy 13, 18, or 21 by a bit, but many women will have unsuccessful test results and will go on to have amniocentesis, negatively affecting the fetal loss rate and the ratio of Down syndrome detected per amniocentesis, she said.

For these and other reasons, it’s premature to abandon current prenatal screening for noninvasive prenatal testing, she said at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco.

She used available data to compare three hypothetical scenarios in which 2.9 million pregnant women would be screened and 5,110 pregnancies would be affected by trisomy 13, 18, or 21. The women would be screened by conventional prenatal testing alone, by current screening methods followed by noninvasive prenatal testing, or solely by the noninvasive Digital Analysis of Selected Regions (DANSR) assay that can identify chromosome abnormalities by evaluating specific fragments of maternal cell-free DNA.

Approximately 145,000 of the women would have a positive screen under current testing or with current testing plus noninvasive testing as a secondary screen, but only 45,710 would have a positive screen with noninvasive testing as the primary screen, she estimated. The number of trisomy 13, 18, or 21 cases identified would be 4,667 under scenario one or two and slightly higher – 5,100 – using the noninvasive screening test primarily, said Dr. Norton, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the university. Current screening can detect many more problems than can noninvasive screening, so 2,004 other abnormalities would be detected using current methods, compared with none using noninvasive testing.

A proportion of patients undergoing noninvasive prenatal screening would have no test result because the sequencing failed to work or not enough DNA was present to get a result – 4,350 women undergoing noninvasive testing as a secondary screen and 87,000 women with noninvasive testing as the primary screen, she estimated.

The total number of amniocenteses would be 145,000 under current testing (one for every positive screen), but would be reduced to 11,047 if noninvasive testing was used as a secondary screen to detect aneuploidies. With noninvasive testing as the primary screen, 67,460 women would undergo amniocentesis. That would result in 435 fetal losses with current testing alone, 33 with current testing and secondary noninvasive prenatal testing, or 202 fetal losses with noninvasive testing as the primary screen.

Eighteen amniocenteses would have to be performed to detect one case of Down syndrome with current prenatal testing alone. With noninvasive testing as a secondary screen, every two amniocenteses would detect a case of Down syndrome. With noninvasive testing as the primary screen, 13 amniocenteses would be needed to detect one case of Down syndrome, Dr. Norton said.

The relative benefits of each scenario remain controversial and may vary by each patient’s level of risk. Further study is needed before the standard of care in prenatal screening is changed.

"Prenatal screening is changing at a rapid pace," Dr. Norton said. Even experts are struggling with how best to incorporate all the new information and new tools. "It’s very exciting times, but confusing even for those of us who practice in the field," she commented.

Dr. Norton has received research funding from Ariosa Diagnostics and CellScape, which are involved in prenatal diagnosis products.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Using noninvasive prenatal DNA testing as a secondary screen after conventional prenatal testing could decrease the number of amniocenteses by more than 90%, reduce fetal losses, and improve the ratio of Down syndrome cases detected per amniocentesis, according to Dr. Mary E. Norton.

On the other hand, using noninvasive prenatal testing as the primary screen would increase the rate of detecting trisomy 13, 18, or 21 by a bit, but many women will have unsuccessful test results and will go on to have amniocentesis, negatively affecting the fetal loss rate and the ratio of Down syndrome detected per amniocentesis, she said.

For these and other reasons, it’s premature to abandon current prenatal screening for noninvasive prenatal testing, she said at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco.

She used available data to compare three hypothetical scenarios in which 2.9 million pregnant women would be screened and 5,110 pregnancies would be affected by trisomy 13, 18, or 21. The women would be screened by conventional prenatal testing alone, by current screening methods followed by noninvasive prenatal testing, or solely by the noninvasive Digital Analysis of Selected Regions (DANSR) assay that can identify chromosome abnormalities by evaluating specific fragments of maternal cell-free DNA.

Approximately 145,000 of the women would have a positive screen under current testing or with current testing plus noninvasive testing as a secondary screen, but only 45,710 would have a positive screen with noninvasive testing as the primary screen, she estimated. The number of trisomy 13, 18, or 21 cases identified would be 4,667 under scenario one or two and slightly higher – 5,100 – using the noninvasive screening test primarily, said Dr. Norton, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the university. Current screening can detect many more problems than can noninvasive screening, so 2,004 other abnormalities would be detected using current methods, compared with none using noninvasive testing.

A proportion of patients undergoing noninvasive prenatal screening would have no test result because the sequencing failed to work or not enough DNA was present to get a result – 4,350 women undergoing noninvasive testing as a secondary screen and 87,000 women with noninvasive testing as the primary screen, she estimated.

The total number of amniocenteses would be 145,000 under current testing (one for every positive screen), but would be reduced to 11,047 if noninvasive testing was used as a secondary screen to detect aneuploidies. With noninvasive testing as the primary screen, 67,460 women would undergo amniocentesis. That would result in 435 fetal losses with current testing alone, 33 with current testing and secondary noninvasive prenatal testing, or 202 fetal losses with noninvasive testing as the primary screen.

Eighteen amniocenteses would have to be performed to detect one case of Down syndrome with current prenatal testing alone. With noninvasive testing as a secondary screen, every two amniocenteses would detect a case of Down syndrome. With noninvasive testing as the primary screen, 13 amniocenteses would be needed to detect one case of Down syndrome, Dr. Norton said.

The relative benefits of each scenario remain controversial and may vary by each patient’s level of risk. Further study is needed before the standard of care in prenatal screening is changed.

"Prenatal screening is changing at a rapid pace," Dr. Norton said. Even experts are struggling with how best to incorporate all the new information and new tools. "It’s very exciting times, but confusing even for those of us who practice in the field," she commented.

Dr. Norton has received research funding from Ariosa Diagnostics and CellScape, which are involved in prenatal diagnosis products.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Using noninvasive prenatal DNA testing as a secondary screen after conventional prenatal testing could decrease the number of amniocenteses by more than 90%, reduce fetal losses, and improve the ratio of Down syndrome cases detected per amniocentesis, according to Dr. Mary E. Norton.

On the other hand, using noninvasive prenatal testing as the primary screen would increase the rate of detecting trisomy 13, 18, or 21 by a bit, but many women will have unsuccessful test results and will go on to have amniocentesis, negatively affecting the fetal loss rate and the ratio of Down syndrome detected per amniocentesis, she said.

For these and other reasons, it’s premature to abandon current prenatal screening for noninvasive prenatal testing, she said at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco.

She used available data to compare three hypothetical scenarios in which 2.9 million pregnant women would be screened and 5,110 pregnancies would be affected by trisomy 13, 18, or 21. The women would be screened by conventional prenatal testing alone, by current screening methods followed by noninvasive prenatal testing, or solely by the noninvasive Digital Analysis of Selected Regions (DANSR) assay that can identify chromosome abnormalities by evaluating specific fragments of maternal cell-free DNA.

Approximately 145,000 of the women would have a positive screen under current testing or with current testing plus noninvasive testing as a secondary screen, but only 45,710 would have a positive screen with noninvasive testing as the primary screen, she estimated. The number of trisomy 13, 18, or 21 cases identified would be 4,667 under scenario one or two and slightly higher – 5,100 – using the noninvasive screening test primarily, said Dr. Norton, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the university. Current screening can detect many more problems than can noninvasive screening, so 2,004 other abnormalities would be detected using current methods, compared with none using noninvasive testing.

A proportion of patients undergoing noninvasive prenatal screening would have no test result because the sequencing failed to work or not enough DNA was present to get a result – 4,350 women undergoing noninvasive testing as a secondary screen and 87,000 women with noninvasive testing as the primary screen, she estimated.

The total number of amniocenteses would be 145,000 under current testing (one for every positive screen), but would be reduced to 11,047 if noninvasive testing was used as a secondary screen to detect aneuploidies. With noninvasive testing as the primary screen, 67,460 women would undergo amniocentesis. That would result in 435 fetal losses with current testing alone, 33 with current testing and secondary noninvasive prenatal testing, or 202 fetal losses with noninvasive testing as the primary screen.

Eighteen amniocenteses would have to be performed to detect one case of Down syndrome with current prenatal testing alone. With noninvasive testing as a secondary screen, every two amniocenteses would detect a case of Down syndrome. With noninvasive testing as the primary screen, 13 amniocenteses would be needed to detect one case of Down syndrome, Dr. Norton said.

The relative benefits of each scenario remain controversial and may vary by each patient’s level of risk. Further study is needed before the standard of care in prenatal screening is changed.

"Prenatal screening is changing at a rapid pace," Dr. Norton said. Even experts are struggling with how best to incorporate all the new information and new tools. "It’s very exciting times, but confusing even for those of us who practice in the field," she commented.

Dr. Norton has received research funding from Ariosa Diagnostics and CellScape, which are involved in prenatal diagnosis products.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING ON ANTEPARTUM AND INTRAPARTUM MANAGEMENT

Tracking quality measures improved perinatal care

SAN FRANCISCO – One California community-based hospital got a head start on tracking core measures of quality in perinatal care that all U.S. hospitals will have to report to The Joint Commission beginning January 2014.

Over the past 2 years, the ob.gyns. found it wasn’t easy, but that tracking core measures of quality significantly improved perinatal care.

Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento, Calif., formed a perinatal data committee in 2010 to identify barriers and develop processes for tracking six quality measures, including the five for The Joint Commission. They worked to overcome doubters on their staff, internally published individual doctors’ rates of cesarean section deliveries and episiotomies, and shared the results for each prenatal obstetrics group.

Their overall rate of elective deliveries at less than 39 weeks’ gestation decreased from 25% of the 4,958 deliveries in October 2010 to 2% of the 5,577 deliveries in December 2012. The cesarean section rate for nulliparous women with a term, singleton fetus in a vertex position dropped from 31% in 2010 to 25% in 2012, Dr. William M. Gilbert reported at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco.

They also improved significantly in two other core measures of quality mandated by The Joint Commission: The proportion of preterm infants who received antenatal steroids before delivery jumped from 80% to 100%, and the proportion of newborns who were fed exclusively breast milk during their entire hospitalization improved from 58% to 70%. The hospital has begun collecting data on a fifth core measure for The Joint Commission: the rate of health care-associated bloodstream infections in newborns.

Dr. Gilbert and his group also tracked two measures that are endorsed by the National Quality Forum but are not yet required by The Joint Commission. Their episiotomy rate decreased significantly from 5% to 2%, and the proportion of women undergoing cesarean section who received appropriate prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis increased from 95% to 98% (Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2013;39:258-66).

"It took us 1-2 years to get the bugs worked out" in tracking core quality measures, said Dr. Gilbert, regional medical director of women’s services for Sutter Health’s Sacramento-Sierra Region, Sacramento, Calif. The effort required leadership from doctors and nurses, administrative and medical records support, and education for coders.

"If your hospital has done nothing to look at what you’re going to be submitting" to The Joint Commission, he added, "I can guarantee you that even if you think you’re doing great, the data are going to be awful, and you’re going to be scrambling to fix a problem that has occurred."

This kind of attention to quality measures in perinatal care is long overdue, he said. Despite the fact that the 4.2 million normal vaginal deliveries per year represent the No. 1 hospital discharge diagnosis in the United States, and studies show immense variation in perinatal practices between hospitals and geographical regions, efforts to measure the quality of hospital care largely have ignored obstetrics because those efforts have focused on Medicare, and few obstetrical patients are covered by Medicare.

Previous studies show a 10-fold variation in cesarean section rates around the country, and cesarean section rates in low-risk patients vary from 2% to 36%. "I would put to you, if you were making widgets or tanks, and you had such variation in the quality of your tanks that the government was paying for, you’d be out of work and probably in jail, but that’s what we tolerate" in health care, he said. Huge variations also have been reported in rates of induction, episiotomy, breastfeeding, and use of antenatal steroids.

The 40 ob.gyns. affiliated with Dr. Gilbert’s hospital had cesarean rates for nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex pregnancies ranging from approximately 8% to 60% when the tracking efforts began, he said. The committee assigned two-digit alphanumeric codes for each provider and posted individual rates of cesarean sections and episiotomies by provider code for 6 months, to start. It took a year of convincing before getting agreement, but then individual rates were posted in the doctors’ and labor and delivery lounges and were e-mailed to all medical staff.

"It’s amazing – amazing what that did," he said. Doctors with the highest cesarean section rates reduced their use of cesarean sections.

The category of elective deliveries at less than 39 weeks’ gestation excluded cases with medical indications for early delivery, but tracking ran into problems initially because ICD-9 codes did not exist for some exemptions, including prior classical cesarean section or prior myomectomy. "You got dinged for that" in the tracking despite the medical indication, he said. So the committee created tracking categories of "avoidable" and "unavoidable" early deliveries, and doctors didn’t get dinged for unavoidable cases.

Some doctors wrote the reason for early delivery as "intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy," which is an appropriate indication, but the medical coders told Dr. Gilbert that having the word "intrahepatic" flagged it as gall bladder disease, which is no reason to deliver early. "We had to work with our coders to help us understand," he said.

Every patient at risk of preterm delivery received antenatal steroids at his hospital, Dr. Gilbert said, "but we weren’t documenting it properly." There had been no uniform spot in the medical record to document administration of antenatal steroids, or to show that they had been given before the current hospitalization. Dr. Gilbert’s team worked with the medical records department to change the electronic health records. Nurses now check off if the patient received a full course of antenatal steroids. If this is missing, the doctor gets a pop-up window where a reason must be given.

"That really was effective," he said.

Tracking of episiotomy excluded cases of shoulder dystocia, but not episiotomy for fetal distress. Despite individual rates being internally publicized, the episiotomy rate seems to be stuck at around 2% because "I do have a couple of old-timers," he said. "Even public embarrassment will not get them to change."

"As an individual and as a hospital, we need to make sure we’re doing the best we can."

Capturing data on whether or not newborns are fed exclusively with breast milk can be difficult, in part because it’s often not clear whether the ob.gyn., the nursing staff, or the pediatrician is responsible for this. Dr. Gilbert’s team analyzed 18 cases at his hospital in which women came in saying they wanted to breastfeed the newborn exclusively, but that didn’t happen. In most cases, the babies received formula after a night nurse moved the baby to the nursery so the mother could sleep, a problem that was addressed. Publicizing exclusive breastfeeding rates for 20 different perinatal obstetrics groups – which ranged from 33% to 93% also helped improve breastfeeding rates.

The perinatal data committee also posted a color-coded "dashboard" showing trends in the hospital’s rates for all these measures over time.

Starting in 2014, The Joint Commission will publish hospital rates for cesarean sections and episiotomies, but not rates for individual doctors. Patient access to individual doctors’ rates of cesarean section, early elective delivery, and episiotomy is likely to come in the future, Dr. Gilbert said, and insurers eventually may select physicians and reimbursement rates based on these outcomes.

"As an individual and as a hospital, we need to make sure we’re doing the best we can," he said.

Dr. Gilbert reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – One California community-based hospital got a head start on tracking core measures of quality in perinatal care that all U.S. hospitals will have to report to The Joint Commission beginning January 2014.

Over the past 2 years, the ob.gyns. found it wasn’t easy, but that tracking core measures of quality significantly improved perinatal care.

Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento, Calif., formed a perinatal data committee in 2010 to identify barriers and develop processes for tracking six quality measures, including the five for The Joint Commission. They worked to overcome doubters on their staff, internally published individual doctors’ rates of cesarean section deliveries and episiotomies, and shared the results for each prenatal obstetrics group.

Their overall rate of elective deliveries at less than 39 weeks’ gestation decreased from 25% of the 4,958 deliveries in October 2010 to 2% of the 5,577 deliveries in December 2012. The cesarean section rate for nulliparous women with a term, singleton fetus in a vertex position dropped from 31% in 2010 to 25% in 2012, Dr. William M. Gilbert reported at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco.

They also improved significantly in two other core measures of quality mandated by The Joint Commission: The proportion of preterm infants who received antenatal steroids before delivery jumped from 80% to 100%, and the proportion of newborns who were fed exclusively breast milk during their entire hospitalization improved from 58% to 70%. The hospital has begun collecting data on a fifth core measure for The Joint Commission: the rate of health care-associated bloodstream infections in newborns.

Dr. Gilbert and his group also tracked two measures that are endorsed by the National Quality Forum but are not yet required by The Joint Commission. Their episiotomy rate decreased significantly from 5% to 2%, and the proportion of women undergoing cesarean section who received appropriate prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis increased from 95% to 98% (Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2013;39:258-66).

"It took us 1-2 years to get the bugs worked out" in tracking core quality measures, said Dr. Gilbert, regional medical director of women’s services for Sutter Health’s Sacramento-Sierra Region, Sacramento, Calif. The effort required leadership from doctors and nurses, administrative and medical records support, and education for coders.

"If your hospital has done nothing to look at what you’re going to be submitting" to The Joint Commission, he added, "I can guarantee you that even if you think you’re doing great, the data are going to be awful, and you’re going to be scrambling to fix a problem that has occurred."

This kind of attention to quality measures in perinatal care is long overdue, he said. Despite the fact that the 4.2 million normal vaginal deliveries per year represent the No. 1 hospital discharge diagnosis in the United States, and studies show immense variation in perinatal practices between hospitals and geographical regions, efforts to measure the quality of hospital care largely have ignored obstetrics because those efforts have focused on Medicare, and few obstetrical patients are covered by Medicare.

Previous studies show a 10-fold variation in cesarean section rates around the country, and cesarean section rates in low-risk patients vary from 2% to 36%. "I would put to you, if you were making widgets or tanks, and you had such variation in the quality of your tanks that the government was paying for, you’d be out of work and probably in jail, but that’s what we tolerate" in health care, he said. Huge variations also have been reported in rates of induction, episiotomy, breastfeeding, and use of antenatal steroids.

The 40 ob.gyns. affiliated with Dr. Gilbert’s hospital had cesarean rates for nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex pregnancies ranging from approximately 8% to 60% when the tracking efforts began, he said. The committee assigned two-digit alphanumeric codes for each provider and posted individual rates of cesarean sections and episiotomies by provider code for 6 months, to start. It took a year of convincing before getting agreement, but then individual rates were posted in the doctors’ and labor and delivery lounges and were e-mailed to all medical staff.

"It’s amazing – amazing what that did," he said. Doctors with the highest cesarean section rates reduced their use of cesarean sections.

The category of elective deliveries at less than 39 weeks’ gestation excluded cases with medical indications for early delivery, but tracking ran into problems initially because ICD-9 codes did not exist for some exemptions, including prior classical cesarean section or prior myomectomy. "You got dinged for that" in the tracking despite the medical indication, he said. So the committee created tracking categories of "avoidable" and "unavoidable" early deliveries, and doctors didn’t get dinged for unavoidable cases.

Some doctors wrote the reason for early delivery as "intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy," which is an appropriate indication, but the medical coders told Dr. Gilbert that having the word "intrahepatic" flagged it as gall bladder disease, which is no reason to deliver early. "We had to work with our coders to help us understand," he said.

Every patient at risk of preterm delivery received antenatal steroids at his hospital, Dr. Gilbert said, "but we weren’t documenting it properly." There had been no uniform spot in the medical record to document administration of antenatal steroids, or to show that they had been given before the current hospitalization. Dr. Gilbert’s team worked with the medical records department to change the electronic health records. Nurses now check off if the patient received a full course of antenatal steroids. If this is missing, the doctor gets a pop-up window where a reason must be given.

"That really was effective," he said.

Tracking of episiotomy excluded cases of shoulder dystocia, but not episiotomy for fetal distress. Despite individual rates being internally publicized, the episiotomy rate seems to be stuck at around 2% because "I do have a couple of old-timers," he said. "Even public embarrassment will not get them to change."

"As an individual and as a hospital, we need to make sure we’re doing the best we can."

Capturing data on whether or not newborns are fed exclusively with breast milk can be difficult, in part because it’s often not clear whether the ob.gyn., the nursing staff, or the pediatrician is responsible for this. Dr. Gilbert’s team analyzed 18 cases at his hospital in which women came in saying they wanted to breastfeed the newborn exclusively, but that didn’t happen. In most cases, the babies received formula after a night nurse moved the baby to the nursery so the mother could sleep, a problem that was addressed. Publicizing exclusive breastfeeding rates for 20 different perinatal obstetrics groups – which ranged from 33% to 93% also helped improve breastfeeding rates.

The perinatal data committee also posted a color-coded "dashboard" showing trends in the hospital’s rates for all these measures over time.

Starting in 2014, The Joint Commission will publish hospital rates for cesarean sections and episiotomies, but not rates for individual doctors. Patient access to individual doctors’ rates of cesarean section, early elective delivery, and episiotomy is likely to come in the future, Dr. Gilbert said, and insurers eventually may select physicians and reimbursement rates based on these outcomes.

"As an individual and as a hospital, we need to make sure we’re doing the best we can," he said.

Dr. Gilbert reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – One California community-based hospital got a head start on tracking core measures of quality in perinatal care that all U.S. hospitals will have to report to The Joint Commission beginning January 2014.

Over the past 2 years, the ob.gyns. found it wasn’t easy, but that tracking core measures of quality significantly improved perinatal care.

Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento, Calif., formed a perinatal data committee in 2010 to identify barriers and develop processes for tracking six quality measures, including the five for The Joint Commission. They worked to overcome doubters on their staff, internally published individual doctors’ rates of cesarean section deliveries and episiotomies, and shared the results for each prenatal obstetrics group.

Their overall rate of elective deliveries at less than 39 weeks’ gestation decreased from 25% of the 4,958 deliveries in October 2010 to 2% of the 5,577 deliveries in December 2012. The cesarean section rate for nulliparous women with a term, singleton fetus in a vertex position dropped from 31% in 2010 to 25% in 2012, Dr. William M. Gilbert reported at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco.

They also improved significantly in two other core measures of quality mandated by The Joint Commission: The proportion of preterm infants who received antenatal steroids before delivery jumped from 80% to 100%, and the proportion of newborns who were fed exclusively breast milk during their entire hospitalization improved from 58% to 70%. The hospital has begun collecting data on a fifth core measure for The Joint Commission: the rate of health care-associated bloodstream infections in newborns.

Dr. Gilbert and his group also tracked two measures that are endorsed by the National Quality Forum but are not yet required by The Joint Commission. Their episiotomy rate decreased significantly from 5% to 2%, and the proportion of women undergoing cesarean section who received appropriate prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis increased from 95% to 98% (Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2013;39:258-66).

"It took us 1-2 years to get the bugs worked out" in tracking core quality measures, said Dr. Gilbert, regional medical director of women’s services for Sutter Health’s Sacramento-Sierra Region, Sacramento, Calif. The effort required leadership from doctors and nurses, administrative and medical records support, and education for coders.

"If your hospital has done nothing to look at what you’re going to be submitting" to The Joint Commission, he added, "I can guarantee you that even if you think you’re doing great, the data are going to be awful, and you’re going to be scrambling to fix a problem that has occurred."

This kind of attention to quality measures in perinatal care is long overdue, he said. Despite the fact that the 4.2 million normal vaginal deliveries per year represent the No. 1 hospital discharge diagnosis in the United States, and studies show immense variation in perinatal practices between hospitals and geographical regions, efforts to measure the quality of hospital care largely have ignored obstetrics because those efforts have focused on Medicare, and few obstetrical patients are covered by Medicare.

Previous studies show a 10-fold variation in cesarean section rates around the country, and cesarean section rates in low-risk patients vary from 2% to 36%. "I would put to you, if you were making widgets or tanks, and you had such variation in the quality of your tanks that the government was paying for, you’d be out of work and probably in jail, but that’s what we tolerate" in health care, he said. Huge variations also have been reported in rates of induction, episiotomy, breastfeeding, and use of antenatal steroids.

The 40 ob.gyns. affiliated with Dr. Gilbert’s hospital had cesarean rates for nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex pregnancies ranging from approximately 8% to 60% when the tracking efforts began, he said. The committee assigned two-digit alphanumeric codes for each provider and posted individual rates of cesarean sections and episiotomies by provider code for 6 months, to start. It took a year of convincing before getting agreement, but then individual rates were posted in the doctors’ and labor and delivery lounges and were e-mailed to all medical staff.

"It’s amazing – amazing what that did," he said. Doctors with the highest cesarean section rates reduced their use of cesarean sections.

The category of elective deliveries at less than 39 weeks’ gestation excluded cases with medical indications for early delivery, but tracking ran into problems initially because ICD-9 codes did not exist for some exemptions, including prior classical cesarean section or prior myomectomy. "You got dinged for that" in the tracking despite the medical indication, he said. So the committee created tracking categories of "avoidable" and "unavoidable" early deliveries, and doctors didn’t get dinged for unavoidable cases.

Some doctors wrote the reason for early delivery as "intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy," which is an appropriate indication, but the medical coders told Dr. Gilbert that having the word "intrahepatic" flagged it as gall bladder disease, which is no reason to deliver early. "We had to work with our coders to help us understand," he said.

Every patient at risk of preterm delivery received antenatal steroids at his hospital, Dr. Gilbert said, "but we weren’t documenting it properly." There had been no uniform spot in the medical record to document administration of antenatal steroids, or to show that they had been given before the current hospitalization. Dr. Gilbert’s team worked with the medical records department to change the electronic health records. Nurses now check off if the patient received a full course of antenatal steroids. If this is missing, the doctor gets a pop-up window where a reason must be given.

"That really was effective," he said.

Tracking of episiotomy excluded cases of shoulder dystocia, but not episiotomy for fetal distress. Despite individual rates being internally publicized, the episiotomy rate seems to be stuck at around 2% because "I do have a couple of old-timers," he said. "Even public embarrassment will not get them to change."

"As an individual and as a hospital, we need to make sure we’re doing the best we can."

Capturing data on whether or not newborns are fed exclusively with breast milk can be difficult, in part because it’s often not clear whether the ob.gyn., the nursing staff, or the pediatrician is responsible for this. Dr. Gilbert’s team analyzed 18 cases at his hospital in which women came in saying they wanted to breastfeed the newborn exclusively, but that didn’t happen. In most cases, the babies received formula after a night nurse moved the baby to the nursery so the mother could sleep, a problem that was addressed. Publicizing exclusive breastfeeding rates for 20 different perinatal obstetrics groups – which ranged from 33% to 93% also helped improve breastfeeding rates.

The perinatal data committee also posted a color-coded "dashboard" showing trends in the hospital’s rates for all these measures over time.

Starting in 2014, The Joint Commission will publish hospital rates for cesarean sections and episiotomies, but not rates for individual doctors. Patient access to individual doctors’ rates of cesarean section, early elective delivery, and episiotomy is likely to come in the future, Dr. Gilbert said, and insurers eventually may select physicians and reimbursement rates based on these outcomes.

"As an individual and as a hospital, we need to make sure we’re doing the best we can," he said.

Dr. Gilbert reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

AT A MEETING ON ANTEPARTUM AND INTRAPARTUM MANAGEMENT

Major finding: Tracking quality measures decreased the rate of elective deliveries before 39 weeks’ gestation from 25% to 2% and the cesarean section rate for nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex deliveries from 31% to 25%.

Data source: Two-year data from one community-based medical center with multiple private practitioners.

Disclosures: Dr. Gilbert reported having no financial disclosures.

Three steps identify causes of most stillbirths

SAN FRANCISCO – The cause of stillbirth can be identified in two-thirds of cases by checking the placental histology, conducting an autopsy, and karyotype testing.

That’s a "major, major take-home point" that’s "very different than what I was taught" in medical training, Dr. Yair J. Blumenfeld said at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco.

That finding from an important 2011 study and other new data in the past 5 years suggests that perhaps clinicians should take a staggered approach when ordering tests to search for the etiology of a stillbirth. "Maybe I shouldn’t do a $2,000 workup for thrombophilia and anticardiolipin antibodies if the autopsy showed me that there’s an underlying structural abnormality, or if there’s an abnormal karyotype," he suggested.

In general, a growing proportion of stillbirths is being attributed to maternal, fetal, or placental causes, shrinking the proportion relegated to "idiopathic" or unexplained stillbirth. The idea that most stillbirths are idiopathic is "somewhat old thinking" at this point, said Dr. Blumenfeld of Stanford (Calif.) University.