User login

North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG)

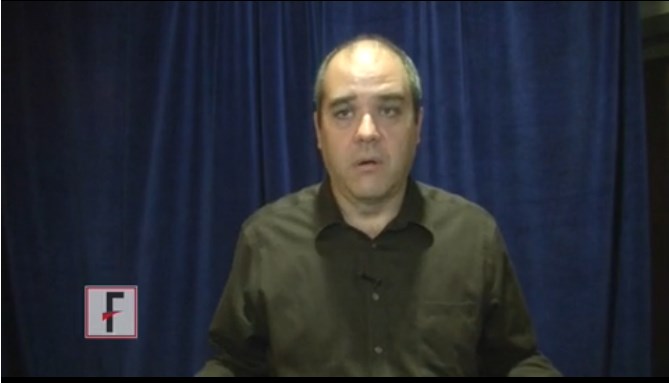

VIDEO: For family physicians, ‘Death is not a defeat’

NEW YORK– Family physicians are more comfortable with letting patients choose to die, and helping them do so comfortably, according to Dr. Richard Young, a speaker at this year’s annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

“We’re more comfortable with death,” he said, comparing physicians accustomed to focusing on one part of the body rather than the whole. That can lead to unnecessary pain and agony for the patient and family, who would be better served being made comfortable, rather than having to endure the heroics of a specialist who “can’t let go,” noted Dr. Young, director of research at the John S. Peters Health System in Fort Worth, Tex.

This video interview is the third in a four-part series on the role family medicine plays in delivering humane, cost-effective health care.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK– Family physicians are more comfortable with letting patients choose to die, and helping them do so comfortably, according to Dr. Richard Young, a speaker at this year’s annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

“We’re more comfortable with death,” he said, comparing physicians accustomed to focusing on one part of the body rather than the whole. That can lead to unnecessary pain and agony for the patient and family, who would be better served being made comfortable, rather than having to endure the heroics of a specialist who “can’t let go,” noted Dr. Young, director of research at the John S. Peters Health System in Fort Worth, Tex.

This video interview is the third in a four-part series on the role family medicine plays in delivering humane, cost-effective health care.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK– Family physicians are more comfortable with letting patients choose to die, and helping them do so comfortably, according to Dr. Richard Young, a speaker at this year’s annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

“We’re more comfortable with death,” he said, comparing physicians accustomed to focusing on one part of the body rather than the whole. That can lead to unnecessary pain and agony for the patient and family, who would be better served being made comfortable, rather than having to endure the heroics of a specialist who “can’t let go,” noted Dr. Young, director of research at the John S. Peters Health System in Fort Worth, Tex.

This video interview is the third in a four-part series on the role family medicine plays in delivering humane, cost-effective health care.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM NAPCRG 2014

VIDEO: Data support family physicians’ cost-effective care methods

NEW YORK – Family physicians are comfortable with uncertainty and view many tests as wastes of money.

These and other characteristics typical of family physicians are what Dr. Richard A. Young calls the foundation of the nation’s most practical and cost-effective care, despite what he calls “bigotry” toward the field from more specialized medicine and from those who created the current system of payment.

“The reason we add value to the world is because we don’t treat everybody the same,” said Dr. Young, the director of research and residency at the John Peter Smith Health System in Fort Worth, Tex.

In this video interview, the fourth and final in a series, Dr. Young makes the case for how, despite systematic overreliance on specialty care, evidence shows it is the primary care physician who is best suited to meet the majority of patients’ needs.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK – Family physicians are comfortable with uncertainty and view many tests as wastes of money.

These and other characteristics typical of family physicians are what Dr. Richard A. Young calls the foundation of the nation’s most practical and cost-effective care, despite what he calls “bigotry” toward the field from more specialized medicine and from those who created the current system of payment.

“The reason we add value to the world is because we don’t treat everybody the same,” said Dr. Young, the director of research and residency at the John Peter Smith Health System in Fort Worth, Tex.

In this video interview, the fourth and final in a series, Dr. Young makes the case for how, despite systematic overreliance on specialty care, evidence shows it is the primary care physician who is best suited to meet the majority of patients’ needs.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK – Family physicians are comfortable with uncertainty and view many tests as wastes of money.

These and other characteristics typical of family physicians are what Dr. Richard A. Young calls the foundation of the nation’s most practical and cost-effective care, despite what he calls “bigotry” toward the field from more specialized medicine and from those who created the current system of payment.

“The reason we add value to the world is because we don’t treat everybody the same,” said Dr. Young, the director of research and residency at the John Peter Smith Health System in Fort Worth, Tex.

In this video interview, the fourth and final in a series, Dr. Young makes the case for how, despite systematic overreliance on specialty care, evidence shows it is the primary care physician who is best suited to meet the majority of patients’ needs.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM NAPCRG 2014

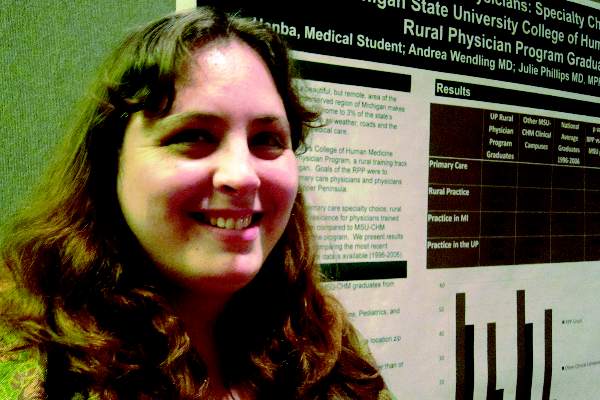

Rural residency program trains, keeps more family physicians

NEW YORK – Graduates of a clinical program designed to train family practice physicians in a rural setting were significantly more likely to practice in rural areas than their peers who trained in a medical school located in more populous areas, according to a poster presented at this year’s North American Primary Care Research Group annual meeting.

Over a ten-year period, nearly half of all graduates of the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine’s Rural Physician Program, a clinical track specifically designed to expose students to life and practice in a rural setting, chose to practice in a rural setting, nearly four times more than graduates of the university’s main campus medical school.

“When the program started, there was a lot of skepticism as to whether it would be successful,” Dr. Julie Phillips, a family physician and assistant dean for student career development at the University’s East Lansing campus, said in an interview. An author of the retrospective analysis, Dr. Phillips said the program enrolls an average of 12 students annually, a quarter of whom stay in the region to set up practice.

The program was created in 1974 to address a shortage of family physicians in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and enrolls students who express an interest in rural practice. Once a student’s clinical training is complete, including a residency that typically occurs in Marquette, the Upper Peninsula’s most populous city with just under 22,000 residents, but a retrospective cohort analysis showed that 42.2 percent of participants enrolled from 1996 to 2006 chose to either return or stay in a more rural setting to set up their practice.

“It looks like [the program] has been a success,” Dr. Phillips said.

She also said relative to other medical schools, the program graduates tended to remain in the state and set up family care practices post-graduation, but that the rural residency program was “significantly better” at attracting physicians than the college’s traditional medical school program. She did not know what proportion of the program graduates who chose rural settings had actually grown up in the areas where they practiced, but said it was a predictor she and her colleagues were considering in a secondary analysis.

“Historically, we have attracted students who did grow up in the Upper Peninsula, but many students who become interested in rural practice actually don’t grow up in rural communities,” Dr. Phillips said.

During the time period studied, 55 percent of rural training track graduates chose to set up a primary care practice, roughly 15 percent more than the ratio of students graduated by the college’s main medical facility (P = .015). More than half of rural track graduates also chose to practice in Michigan, compared with 40 percent of the medical school graduates from the main campus (P = .006). A quarter of the rural program’s graduates stayed to practice in the Upper Peninsula, compared with the one percent of physicians graduated from the main campus (P less than .001) who chose to settle in the Upper Peninsula. Overall, 42.2 percent of rural program graduates set up practice in any rural area during the time period studied, compared with 13 percent of graduates from the main medical school (P less than .001)

Dr. Phillips and her colleagues considered a community rural if it met Code 4 specifications from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Continuum – typically populations of 20,000 or less. The results of the program are impressive, Dr. Dana E. King, professor and chair of family medicine at the University of West Virginia, said in an interview.

Being able to attract people to places that are somehow geographically undesirable, either because they are isolated, have harsh winters, or aren’t near a city, is difficult.” The key to success is appealing to the physician’s spouse, said Dr. King. “What if you’re married to a Ph.D. in something, or another physician? There is a challenge to provide enough opportunities for both the physician and spouse. The fact that [Michigan State University’s rural practice program] has had these kind of results is a testament to the fact that it pays attention to the needs of the physician’s family and to the entire community.”

Dr. King, who is the secretary and treasurer of the North American Primary Care Research Group, is not affiliated with the study.

Dr. Phillips said that the program curriculum does address the specific challenges -- and rewards -- of living and practicing in a rural community, but that the program’s rural location itself was the most instructive. “The students are already there. They’re in medical school in a rural setting. They don’t need to go somewhere else to learn about a rural life after they learn medicine.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK – Graduates of a clinical program designed to train family practice physicians in a rural setting were significantly more likely to practice in rural areas than their peers who trained in a medical school located in more populous areas, according to a poster presented at this year’s North American Primary Care Research Group annual meeting.

Over a ten-year period, nearly half of all graduates of the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine’s Rural Physician Program, a clinical track specifically designed to expose students to life and practice in a rural setting, chose to practice in a rural setting, nearly four times more than graduates of the university’s main campus medical school.

“When the program started, there was a lot of skepticism as to whether it would be successful,” Dr. Julie Phillips, a family physician and assistant dean for student career development at the University’s East Lansing campus, said in an interview. An author of the retrospective analysis, Dr. Phillips said the program enrolls an average of 12 students annually, a quarter of whom stay in the region to set up practice.

The program was created in 1974 to address a shortage of family physicians in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and enrolls students who express an interest in rural practice. Once a student’s clinical training is complete, including a residency that typically occurs in Marquette, the Upper Peninsula’s most populous city with just under 22,000 residents, but a retrospective cohort analysis showed that 42.2 percent of participants enrolled from 1996 to 2006 chose to either return or stay in a more rural setting to set up their practice.

“It looks like [the program] has been a success,” Dr. Phillips said.

She also said relative to other medical schools, the program graduates tended to remain in the state and set up family care practices post-graduation, but that the rural residency program was “significantly better” at attracting physicians than the college’s traditional medical school program. She did not know what proportion of the program graduates who chose rural settings had actually grown up in the areas where they practiced, but said it was a predictor she and her colleagues were considering in a secondary analysis.

“Historically, we have attracted students who did grow up in the Upper Peninsula, but many students who become interested in rural practice actually don’t grow up in rural communities,” Dr. Phillips said.

During the time period studied, 55 percent of rural training track graduates chose to set up a primary care practice, roughly 15 percent more than the ratio of students graduated by the college’s main medical facility (P = .015). More than half of rural track graduates also chose to practice in Michigan, compared with 40 percent of the medical school graduates from the main campus (P = .006). A quarter of the rural program’s graduates stayed to practice in the Upper Peninsula, compared with the one percent of physicians graduated from the main campus (P less than .001) who chose to settle in the Upper Peninsula. Overall, 42.2 percent of rural program graduates set up practice in any rural area during the time period studied, compared with 13 percent of graduates from the main medical school (P less than .001)

Dr. Phillips and her colleagues considered a community rural if it met Code 4 specifications from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Continuum – typically populations of 20,000 or less. The results of the program are impressive, Dr. Dana E. King, professor and chair of family medicine at the University of West Virginia, said in an interview.

Being able to attract people to places that are somehow geographically undesirable, either because they are isolated, have harsh winters, or aren’t near a city, is difficult.” The key to success is appealing to the physician’s spouse, said Dr. King. “What if you’re married to a Ph.D. in something, or another physician? There is a challenge to provide enough opportunities for both the physician and spouse. The fact that [Michigan State University’s rural practice program] has had these kind of results is a testament to the fact that it pays attention to the needs of the physician’s family and to the entire community.”

Dr. King, who is the secretary and treasurer of the North American Primary Care Research Group, is not affiliated with the study.

Dr. Phillips said that the program curriculum does address the specific challenges -- and rewards -- of living and practicing in a rural community, but that the program’s rural location itself was the most instructive. “The students are already there. They’re in medical school in a rural setting. They don’t need to go somewhere else to learn about a rural life after they learn medicine.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK – Graduates of a clinical program designed to train family practice physicians in a rural setting were significantly more likely to practice in rural areas than their peers who trained in a medical school located in more populous areas, according to a poster presented at this year’s North American Primary Care Research Group annual meeting.

Over a ten-year period, nearly half of all graduates of the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine’s Rural Physician Program, a clinical track specifically designed to expose students to life and practice in a rural setting, chose to practice in a rural setting, nearly four times more than graduates of the university’s main campus medical school.

“When the program started, there was a lot of skepticism as to whether it would be successful,” Dr. Julie Phillips, a family physician and assistant dean for student career development at the University’s East Lansing campus, said in an interview. An author of the retrospective analysis, Dr. Phillips said the program enrolls an average of 12 students annually, a quarter of whom stay in the region to set up practice.

The program was created in 1974 to address a shortage of family physicians in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and enrolls students who express an interest in rural practice. Once a student’s clinical training is complete, including a residency that typically occurs in Marquette, the Upper Peninsula’s most populous city with just under 22,000 residents, but a retrospective cohort analysis showed that 42.2 percent of participants enrolled from 1996 to 2006 chose to either return or stay in a more rural setting to set up their practice.

“It looks like [the program] has been a success,” Dr. Phillips said.

She also said relative to other medical schools, the program graduates tended to remain in the state and set up family care practices post-graduation, but that the rural residency program was “significantly better” at attracting physicians than the college’s traditional medical school program. She did not know what proportion of the program graduates who chose rural settings had actually grown up in the areas where they practiced, but said it was a predictor she and her colleagues were considering in a secondary analysis.

“Historically, we have attracted students who did grow up in the Upper Peninsula, but many students who become interested in rural practice actually don’t grow up in rural communities,” Dr. Phillips said.

During the time period studied, 55 percent of rural training track graduates chose to set up a primary care practice, roughly 15 percent more than the ratio of students graduated by the college’s main medical facility (P = .015). More than half of rural track graduates also chose to practice in Michigan, compared with 40 percent of the medical school graduates from the main campus (P = .006). A quarter of the rural program’s graduates stayed to practice in the Upper Peninsula, compared with the one percent of physicians graduated from the main campus (P less than .001) who chose to settle in the Upper Peninsula. Overall, 42.2 percent of rural program graduates set up practice in any rural area during the time period studied, compared with 13 percent of graduates from the main medical school (P less than .001)

Dr. Phillips and her colleagues considered a community rural if it met Code 4 specifications from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Continuum – typically populations of 20,000 or less. The results of the program are impressive, Dr. Dana E. King, professor and chair of family medicine at the University of West Virginia, said in an interview.

Being able to attract people to places that are somehow geographically undesirable, either because they are isolated, have harsh winters, or aren’t near a city, is difficult.” The key to success is appealing to the physician’s spouse, said Dr. King. “What if you’re married to a Ph.D. in something, or another physician? There is a challenge to provide enough opportunities for both the physician and spouse. The fact that [Michigan State University’s rural practice program] has had these kind of results is a testament to the fact that it pays attention to the needs of the physician’s family and to the entire community.”

Dr. King, who is the secretary and treasurer of the North American Primary Care Research Group, is not affiliated with the study.

Dr. Phillips said that the program curriculum does address the specific challenges -- and rewards -- of living and practicing in a rural community, but that the program’s rural location itself was the most instructive. “The students are already there. They’re in medical school in a rural setting. They don’t need to go somewhere else to learn about a rural life after they learn medicine.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Key clinical point: Clinical training programs designed specifically around rural communities can increase the number of physicians who choose to practice permanently in these settings.

Major finding: Graduates of a rural physician training program were significantly more likely to practice in rural areas, compared with graduates from non-rural physician programs (P less than .001).

Data source: Retrospective cohort study analysis of rural physician training program graduates and non-rural physician training from a single academic center between 1996 and 2006.

Disclosures: Dr. Phillips did not have any relevant disclosures.

VIDEO: ‘Meaningless use’? Quality measures pit physicians against patients

NEW YORK – Because quality measures intended to create patient-centered care are impractical, elitist, and ungrounded in the realities of most patients’ lives, physicians are forced to choose between being a failure, a bully, or both.

That’s according to Dr. Richard Young, director of research at the John S. Peters Health System in Fort Worth, Tex., and a speaker at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

“The grand irony is that patient-centered care ... becomes a carrot-and-stick measurement system that incentivizes [doctors] to get what [they] want patients to do, not what the patients want,” Dr. Young said.

In a video interview, he also explains how borrowing “exception reporting” as practiced in the United Kingdom’s National Health Service would make the United States’ own quality measurement system more practical. Dr. Young also explains how physicians’ fear of missing quality measurement marks may lead them to avoid taking on the sickest and neediest of patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK – Because quality measures intended to create patient-centered care are impractical, elitist, and ungrounded in the realities of most patients’ lives, physicians are forced to choose between being a failure, a bully, or both.

That’s according to Dr. Richard Young, director of research at the John S. Peters Health System in Fort Worth, Tex., and a speaker at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

“The grand irony is that patient-centered care ... becomes a carrot-and-stick measurement system that incentivizes [doctors] to get what [they] want patients to do, not what the patients want,” Dr. Young said.

In a video interview, he also explains how borrowing “exception reporting” as practiced in the United Kingdom’s National Health Service would make the United States’ own quality measurement system more practical. Dr. Young also explains how physicians’ fear of missing quality measurement marks may lead them to avoid taking on the sickest and neediest of patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK – Because quality measures intended to create patient-centered care are impractical, elitist, and ungrounded in the realities of most patients’ lives, physicians are forced to choose between being a failure, a bully, or both.

That’s according to Dr. Richard Young, director of research at the John S. Peters Health System in Fort Worth, Tex., and a speaker at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

“The grand irony is that patient-centered care ... becomes a carrot-and-stick measurement system that incentivizes [doctors] to get what [they] want patients to do, not what the patients want,” Dr. Young said.

In a video interview, he also explains how borrowing “exception reporting” as practiced in the United Kingdom’s National Health Service would make the United States’ own quality measurement system more practical. Dr. Young also explains how physicians’ fear of missing quality measurement marks may lead them to avoid taking on the sickest and neediest of patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT NAPCRG 2014

Study: FPs with maternity care skills still needed in rural United States

NEW YORK - In rural hospitals, family physicians are very likely to deliver babies, even if the facility has at least one obstetrician with admitting privileges, according to survey results of 457 chief executives of rural American hospitals.

The survey also showed that, in southwestern and western states like Texas and Montana, nearly all maternity care–skilled FPs were likely to perform any necessary C-sections, although, across the country, only 63% of FPs are able to deliver cesarean births, Dr. Richard Young said at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Just over two-thirds of the respondents said they had dedicated maternity facilities where, on average, 271 babies are born annually, with just over a quarter being delivered by C-section. The hospital executives reported an average ratio of 1.6 obstetricians to every 2.8 maternity-skilled family practitioners, according to Dr. Young, director of research and associate director of the family medicine residency program at John Peters Smith Hospital in Ft. Worth, Tex., which is affiliated with the University of Texas.

Going by the numbers, the average numbers of vaginal and caesarean births a rural hospital required a family doctor to have performed to receive hospital admitting privileges were 40 and 35, respectively.

Because so many respondents either answered the question loosely or not at all, short of having been fellowship trained, “basically, if you claimed you could do this, then ol’ doc Pritchard would watch you do it, and if he said you were good, then you were good,” he concluded.

Practicing midwives in these hospitals were essentially nonexistent.

The findings point to a need for family practice residency programs to include and, in some cases, expand their maternity medicine offerings. “Rural America needs us,” Dr. Young said.

Other data support his imperative. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reports that nearly half of all 3,107 U.S. counties, many of them in rural areas, lack even one ob.gyn. Meanwhile, a 2013 study published in the Journal of Women’s Health and conducted in part by ACOG indicated that, even by modest measures, in 2020 the demand for maternity care specialists would increase 6%, much of it in states with large rural populations, such as Texas, Nevada, and Idaho, yet the number of ob.gyns. entering the field has remained relatively flat since 1980.

In Dr. Young’s survey, the number of acute-care beds corresponded to the maternity-care workload of the family care physicians. Overall, family physicians who offered maternity care tended to figure most prominently in hospitals with 100 beds or fewer, while facilities with 150 beds or more had double the number of OBs as maternity-skilled FPs; however, even then, two-thirds of the FPs still performed their own C-sections.

The study’s accuracy was limited because not all states were represented in the data, and Dr. Young was unsure if he had been able to reach all rural hospital facilities in each state (his initial mailing was to approximately 1,000 facilities). Of the states where hospital executives did respond, three-quarters of the hospitals were critical-access facilities, 60% were nonprofit centers, and just over a quarter were government run. The rest were either for-profit facilities or other types of centers.

Despite what he said were cultural differences from state to state, Dr. Young said that “family doctors continue to provide the majority of maternity care in rural U.S. hospitals.”

The implications of this, he said, were that, even though it was evident from the low threshold for admitting privileges across the facilities surveyed, family medicine residency programs “know what they need to teach … and we’ve got to keep training these doctors how to do obstetrics, including C-sections, because the OBs aren’t going to go to [rural areas] and do it.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK - In rural hospitals, family physicians are very likely to deliver babies, even if the facility has at least one obstetrician with admitting privileges, according to survey results of 457 chief executives of rural American hospitals.

The survey also showed that, in southwestern and western states like Texas and Montana, nearly all maternity care–skilled FPs were likely to perform any necessary C-sections, although, across the country, only 63% of FPs are able to deliver cesarean births, Dr. Richard Young said at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Just over two-thirds of the respondents said they had dedicated maternity facilities where, on average, 271 babies are born annually, with just over a quarter being delivered by C-section. The hospital executives reported an average ratio of 1.6 obstetricians to every 2.8 maternity-skilled family practitioners, according to Dr. Young, director of research and associate director of the family medicine residency program at John Peters Smith Hospital in Ft. Worth, Tex., which is affiliated with the University of Texas.

Going by the numbers, the average numbers of vaginal and caesarean births a rural hospital required a family doctor to have performed to receive hospital admitting privileges were 40 and 35, respectively.

Because so many respondents either answered the question loosely or not at all, short of having been fellowship trained, “basically, if you claimed you could do this, then ol’ doc Pritchard would watch you do it, and if he said you were good, then you were good,” he concluded.

Practicing midwives in these hospitals were essentially nonexistent.

The findings point to a need for family practice residency programs to include and, in some cases, expand their maternity medicine offerings. “Rural America needs us,” Dr. Young said.

Other data support his imperative. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reports that nearly half of all 3,107 U.S. counties, many of them in rural areas, lack even one ob.gyn. Meanwhile, a 2013 study published in the Journal of Women’s Health and conducted in part by ACOG indicated that, even by modest measures, in 2020 the demand for maternity care specialists would increase 6%, much of it in states with large rural populations, such as Texas, Nevada, and Idaho, yet the number of ob.gyns. entering the field has remained relatively flat since 1980.

In Dr. Young’s survey, the number of acute-care beds corresponded to the maternity-care workload of the family care physicians. Overall, family physicians who offered maternity care tended to figure most prominently in hospitals with 100 beds or fewer, while facilities with 150 beds or more had double the number of OBs as maternity-skilled FPs; however, even then, two-thirds of the FPs still performed their own C-sections.

The study’s accuracy was limited because not all states were represented in the data, and Dr. Young was unsure if he had been able to reach all rural hospital facilities in each state (his initial mailing was to approximately 1,000 facilities). Of the states where hospital executives did respond, three-quarters of the hospitals were critical-access facilities, 60% were nonprofit centers, and just over a quarter were government run. The rest were either for-profit facilities or other types of centers.

Despite what he said were cultural differences from state to state, Dr. Young said that “family doctors continue to provide the majority of maternity care in rural U.S. hospitals.”

The implications of this, he said, were that, even though it was evident from the low threshold for admitting privileges across the facilities surveyed, family medicine residency programs “know what they need to teach … and we’ve got to keep training these doctors how to do obstetrics, including C-sections, because the OBs aren’t going to go to [rural areas] and do it.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK - In rural hospitals, family physicians are very likely to deliver babies, even if the facility has at least one obstetrician with admitting privileges, according to survey results of 457 chief executives of rural American hospitals.

The survey also showed that, in southwestern and western states like Texas and Montana, nearly all maternity care–skilled FPs were likely to perform any necessary C-sections, although, across the country, only 63% of FPs are able to deliver cesarean births, Dr. Richard Young said at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Just over two-thirds of the respondents said they had dedicated maternity facilities where, on average, 271 babies are born annually, with just over a quarter being delivered by C-section. The hospital executives reported an average ratio of 1.6 obstetricians to every 2.8 maternity-skilled family practitioners, according to Dr. Young, director of research and associate director of the family medicine residency program at John Peters Smith Hospital in Ft. Worth, Tex., which is affiliated with the University of Texas.

Going by the numbers, the average numbers of vaginal and caesarean births a rural hospital required a family doctor to have performed to receive hospital admitting privileges were 40 and 35, respectively.

Because so many respondents either answered the question loosely or not at all, short of having been fellowship trained, “basically, if you claimed you could do this, then ol’ doc Pritchard would watch you do it, and if he said you were good, then you were good,” he concluded.

Practicing midwives in these hospitals were essentially nonexistent.

The findings point to a need for family practice residency programs to include and, in some cases, expand their maternity medicine offerings. “Rural America needs us,” Dr. Young said.

Other data support his imperative. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reports that nearly half of all 3,107 U.S. counties, many of them in rural areas, lack even one ob.gyn. Meanwhile, a 2013 study published in the Journal of Women’s Health and conducted in part by ACOG indicated that, even by modest measures, in 2020 the demand for maternity care specialists would increase 6%, much of it in states with large rural populations, such as Texas, Nevada, and Idaho, yet the number of ob.gyns. entering the field has remained relatively flat since 1980.

In Dr. Young’s survey, the number of acute-care beds corresponded to the maternity-care workload of the family care physicians. Overall, family physicians who offered maternity care tended to figure most prominently in hospitals with 100 beds or fewer, while facilities with 150 beds or more had double the number of OBs as maternity-skilled FPs; however, even then, two-thirds of the FPs still performed their own C-sections.

The study’s accuracy was limited because not all states were represented in the data, and Dr. Young was unsure if he had been able to reach all rural hospital facilities in each state (his initial mailing was to approximately 1,000 facilities). Of the states where hospital executives did respond, three-quarters of the hospitals were critical-access facilities, 60% were nonprofit centers, and just over a quarter were government run. The rest were either for-profit facilities or other types of centers.

Despite what he said were cultural differences from state to state, Dr. Young said that “family doctors continue to provide the majority of maternity care in rural U.S. hospitals.”

The implications of this, he said, were that, even though it was evident from the low threshold for admitting privileges across the facilities surveyed, family medicine residency programs “know what they need to teach … and we’ve got to keep training these doctors how to do obstetrics, including C-sections, because the OBs aren’t going to go to [rural areas] and do it.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Key clinical point: Family physician residency programs must provide extensive maternity care training.

Major finding: Family physicians are twice as likely, on average, to deliver babies in the rural United States, compared with OBs; two-thirds of these FPs perform C-sections.

Data source: Survey of 457 rural American hospital CEOs.

Disclosures: Neither Dr. Young nor his associate, Dr. Kelsey Walker, had any relevant disclosures. The study was made possible by a grant from the Texas Academy of Family Physicians.

Lose the weight or lose the money: Online weight-loss contracts gain favor

NEW YORK – The more you stand to lose, the deeper your commitment to losing, particularly when it’s your wallet and not your word that’s at stake.

People who contractually committed online to lose a certain amount of weight or else fork over a predetermined amount of cash to a friend, a favorite charity, or even a hated charity were, on average, successful at losing 5.2% of their body weight, according to preliminary data presented at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

In a retrospective analysis of 5,024 self-selected participants in an online contractual weight loss site, 70% of whom were women whose average age was 39 years, the ones who pledged to let their money go to an “anticharity” if they didn’t meet their weight loss goals lost nearly 8% of their body weight. Those who pledged to give to a favorite charity lost just under 7%, and those who promised to pay a friend if they didn’t succeed lost 6.3% of their body weight. Those whose commitment did not involve any cash lost 3.4% of their body weight.

“If you are for gun control, your anticharity would be the National Rifle Association,” Dr. Lenard Lesser, a family physician and researcher at the Palo Alto (Calif.) Medical Foundation and Research Institute, said in an interview. “So, if you don’t lose the weight you said you’d lose, then the money you committed would go to the NRA.”

There was no statistical difference in weight loss between those who committed to either a charity or an anticharity, but according to Dr. Lesser, the data, set to be published in the near future, indicated that there was a statistical difference between the amount of weight lost when money was committed compared with when no money was committed. “People are averse to losing money wherever it goes,” he said.

The average duration of the weight loss commitments in the online weight loss commitment study were between 10 and 16 weeks, but it is unclear whether the weight loss was permanent, and whether the contracts could serve as a viable weight loss intervention in the primary care setting, according to Dr. Lesser. “We don’t know what happens to these people long term. We need to explore how these contracts can be integrated into a more comprehensive system.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK – The more you stand to lose, the deeper your commitment to losing, particularly when it’s your wallet and not your word that’s at stake.

People who contractually committed online to lose a certain amount of weight or else fork over a predetermined amount of cash to a friend, a favorite charity, or even a hated charity were, on average, successful at losing 5.2% of their body weight, according to preliminary data presented at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

In a retrospective analysis of 5,024 self-selected participants in an online contractual weight loss site, 70% of whom were women whose average age was 39 years, the ones who pledged to let their money go to an “anticharity” if they didn’t meet their weight loss goals lost nearly 8% of their body weight. Those who pledged to give to a favorite charity lost just under 7%, and those who promised to pay a friend if they didn’t succeed lost 6.3% of their body weight. Those whose commitment did not involve any cash lost 3.4% of their body weight.

“If you are for gun control, your anticharity would be the National Rifle Association,” Dr. Lenard Lesser, a family physician and researcher at the Palo Alto (Calif.) Medical Foundation and Research Institute, said in an interview. “So, if you don’t lose the weight you said you’d lose, then the money you committed would go to the NRA.”

There was no statistical difference in weight loss between those who committed to either a charity or an anticharity, but according to Dr. Lesser, the data, set to be published in the near future, indicated that there was a statistical difference between the amount of weight lost when money was committed compared with when no money was committed. “People are averse to losing money wherever it goes,” he said.

The average duration of the weight loss commitments in the online weight loss commitment study were between 10 and 16 weeks, but it is unclear whether the weight loss was permanent, and whether the contracts could serve as a viable weight loss intervention in the primary care setting, according to Dr. Lesser. “We don’t know what happens to these people long term. We need to explore how these contracts can be integrated into a more comprehensive system.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK – The more you stand to lose, the deeper your commitment to losing, particularly when it’s your wallet and not your word that’s at stake.

People who contractually committed online to lose a certain amount of weight or else fork over a predetermined amount of cash to a friend, a favorite charity, or even a hated charity were, on average, successful at losing 5.2% of their body weight, according to preliminary data presented at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

In a retrospective analysis of 5,024 self-selected participants in an online contractual weight loss site, 70% of whom were women whose average age was 39 years, the ones who pledged to let their money go to an “anticharity” if they didn’t meet their weight loss goals lost nearly 8% of their body weight. Those who pledged to give to a favorite charity lost just under 7%, and those who promised to pay a friend if they didn’t succeed lost 6.3% of their body weight. Those whose commitment did not involve any cash lost 3.4% of their body weight.

“If you are for gun control, your anticharity would be the National Rifle Association,” Dr. Lenard Lesser, a family physician and researcher at the Palo Alto (Calif.) Medical Foundation and Research Institute, said in an interview. “So, if you don’t lose the weight you said you’d lose, then the money you committed would go to the NRA.”

There was no statistical difference in weight loss between those who committed to either a charity or an anticharity, but according to Dr. Lesser, the data, set to be published in the near future, indicated that there was a statistical difference between the amount of weight lost when money was committed compared with when no money was committed. “People are averse to losing money wherever it goes,” he said.

The average duration of the weight loss commitments in the online weight loss commitment study were between 10 and 16 weeks, but it is unclear whether the weight loss was permanent, and whether the contracts could serve as a viable weight loss intervention in the primary care setting, according to Dr. Lesser. “We don’t know what happens to these people long term. We need to explore how these contracts can be integrated into a more comprehensive system.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT NAPCRG 2014

Key clinical point: Online weight-loss commitment contracts can be effective interventions for patients.

Major finding: People who contractually committed to losing weight lost an average of 5.2% of their body weight; when loss of money was at stake, the body weight losses were highest.

Data source: A retrospective secondary analysis of online commitment contracts from 5,024 self-selected individuals.

Disclosures: Dr. Lesser said he did not have any relevant disclosures.

Less confident nurses more likely to elevate triage level in calls to primary care clinics

NEW YORK – Nurses who lacked confidence as telephone triage advisers were more likely than more confident nurses to elevate the triage level of patients calling general practice clinics for same-day service, according to a British report.

The findings have implications for busy general practice physicians who are considering such programs to help ease their daily patient load.

Although there is “broad public support” in Britain for nurse practitioners and general nursing staff taking on many of the tasks usually associated with general practitioners, the manner in which these nurses handle patients varies greatly, according to Anna Varley, a social worker and researcher at the University of East Anglia, Norwich, England, who spoke at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

“Previous research is still equivocal as to explaining exactly why it is that different health professionals make different decisions about the same calls,” Ms. Varley said to a capacity crowd.

However, data from a randomized, controlled study of telephone triage services indicated that a nurse’s self-reported level of preparedness, was key to how – and if – she advised that callers receive follow-up care.

“Therefore, standardized telephone triage training is necessary, but it may not be sufficient,” Ms. Varley said.

The data were part of the larger, clustered, randomized controlled ESTEEM trial conducted across four regions in the United Kingdom between March 2011 and March 2013 to examine the outcomes and cost-effectiveness of telephone triage services. In the study, patients seeking same-day consultations were randomly assigned with intention to treat and by protocol, to either general practice–led phone triage care; nurse practitioner–led, computer-supported phone triage care; or usual practice. Allocation was not blinded to patients, clinicians, or researchers, but practice assignment was concealed from the study’s statistician. In all, 20,990 patient calls were managed by 42 general care clinics, with 77% of all patient-clinician interactions reaching the primary outcome of additional follow-up within 28 days of the initial call. The results of the larger trial were published recently in the Lancet (2014 Nov. 22 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61058-8]). For the subanalysis, Ms. Varley and her coinvestigators evaluated the 7,012 patient calls randomly routed to triage intervention from 45 nurses across 15 general practices in the four regions. All of the nursing staff were women, and all had been trained in the use of the clinical decision support software. All nurses were surveyed to discover their levels of training, experience, and facility with triage software. Thirty-five of the original 45 nurses returned valid profiles.

Of these, eight were nurse practitioners, an important distinction given that in the United Kingdom, this denotes more years of formal medical training than other nursing professionals, the authority to diagnose, and typically, the authority to prescribe medication.

The remaining 27 nurses were what are known in Britain as “practice nurses.” This group is not authorized to prescribe, and generally has less authority in other matters as well.

The range of the two groups of nurses’ years of experience was 2.5-40 years, although 89% of all nurse participants had 10 or more years of practical experience; 69% had 20 or more years of experience.

Across both groups, nearly half had prior experience manning triage phone lines, although only 2 of the 35 women had ever used the clinical support software.

At the time of each call, the nurses were asked to rate how prepared they felt for the particulars of the call. These data were included when evaluating how often each nurse recommended a caller for follow-up. Although most calls (86%) were recommended to some form of follow-up, nurse practitioners were less likely than practice nurses to recommend follow-up care (odds ratio, 0.19; confidence interval, 0.07-0.49). Across both groups, nurses who reported less confidence in their ability to manage the call were found more likely to recommend patients for follow-up (OR, 3.17; CI, 1.18-5.55). Additionally, less seasoned nurses, defined as those with 10 or less years of practical experience, had significantly longer mean call durations (OR, 2.58; CI, 0.76-4.40).

As reported in the larger ESTEEM trial, nurse-led triage resulted in an overall 48% increase in patient contacts over a 28-day period, compared with usual care. General practice physician–led triage resulted in a 33% increase over usual care during the same period. Despite the increase in patient contacts, the costs of care were found to remain essentially the same (about 75 British pounds sterling). Eight deaths were reported overall, including two triaged by the nurses, but none of the deaths were associated with the trial itself.

The overall implications of the study are positive, so long as there is already an established trust between the patient and the general practice clinic, according to Dr. Garey Mazowita, a family practice physician in Vancouver, B.C., who is participating in a telephone screening program for general practitioners in his home province.

“At the heart of the medical home model we are moving toward is the continuity of the relationship between the family care doctor and the patient, and the knowledge that if you do something over the phone that averts an office visit, you’ve still got the security of the relationship [to rely on],” Dr. Mazowita, who is also the president of the College of Family Physicians of Canada, said in an interview. “We think it’s fundamentally safer than if no relationship exists.”

Ms. Varley agreed that how general practice clinics, and in particular, the physicians, related to patients overall was important, but said that for the purpose of nurse-led call screening, it was important to note that while all triage call screening was shown in the study to be comparably safe, “the individual characteristics of nurses independently influenced how telephone triage was implemented.”

Neither Ms. Varley nor Dr. Mazowita had any relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK – Nurses who lacked confidence as telephone triage advisers were more likely than more confident nurses to elevate the triage level of patients calling general practice clinics for same-day service, according to a British report.

The findings have implications for busy general practice physicians who are considering such programs to help ease their daily patient load.

Although there is “broad public support” in Britain for nurse practitioners and general nursing staff taking on many of the tasks usually associated with general practitioners, the manner in which these nurses handle patients varies greatly, according to Anna Varley, a social worker and researcher at the University of East Anglia, Norwich, England, who spoke at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

“Previous research is still equivocal as to explaining exactly why it is that different health professionals make different decisions about the same calls,” Ms. Varley said to a capacity crowd.

However, data from a randomized, controlled study of telephone triage services indicated that a nurse’s self-reported level of preparedness, was key to how – and if – she advised that callers receive follow-up care.

“Therefore, standardized telephone triage training is necessary, but it may not be sufficient,” Ms. Varley said.

The data were part of the larger, clustered, randomized controlled ESTEEM trial conducted across four regions in the United Kingdom between March 2011 and March 2013 to examine the outcomes and cost-effectiveness of telephone triage services. In the study, patients seeking same-day consultations were randomly assigned with intention to treat and by protocol, to either general practice–led phone triage care; nurse practitioner–led, computer-supported phone triage care; or usual practice. Allocation was not blinded to patients, clinicians, or researchers, but practice assignment was concealed from the study’s statistician. In all, 20,990 patient calls were managed by 42 general care clinics, with 77% of all patient-clinician interactions reaching the primary outcome of additional follow-up within 28 days of the initial call. The results of the larger trial were published recently in the Lancet (2014 Nov. 22 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61058-8]). For the subanalysis, Ms. Varley and her coinvestigators evaluated the 7,012 patient calls randomly routed to triage intervention from 45 nurses across 15 general practices in the four regions. All of the nursing staff were women, and all had been trained in the use of the clinical decision support software. All nurses were surveyed to discover their levels of training, experience, and facility with triage software. Thirty-five of the original 45 nurses returned valid profiles.

Of these, eight were nurse practitioners, an important distinction given that in the United Kingdom, this denotes more years of formal medical training than other nursing professionals, the authority to diagnose, and typically, the authority to prescribe medication.

The remaining 27 nurses were what are known in Britain as “practice nurses.” This group is not authorized to prescribe, and generally has less authority in other matters as well.

The range of the two groups of nurses’ years of experience was 2.5-40 years, although 89% of all nurse participants had 10 or more years of practical experience; 69% had 20 or more years of experience.

Across both groups, nearly half had prior experience manning triage phone lines, although only 2 of the 35 women had ever used the clinical support software.

At the time of each call, the nurses were asked to rate how prepared they felt for the particulars of the call. These data were included when evaluating how often each nurse recommended a caller for follow-up. Although most calls (86%) were recommended to some form of follow-up, nurse practitioners were less likely than practice nurses to recommend follow-up care (odds ratio, 0.19; confidence interval, 0.07-0.49). Across both groups, nurses who reported less confidence in their ability to manage the call were found more likely to recommend patients for follow-up (OR, 3.17; CI, 1.18-5.55). Additionally, less seasoned nurses, defined as those with 10 or less years of practical experience, had significantly longer mean call durations (OR, 2.58; CI, 0.76-4.40).

As reported in the larger ESTEEM trial, nurse-led triage resulted in an overall 48% increase in patient contacts over a 28-day period, compared with usual care. General practice physician–led triage resulted in a 33% increase over usual care during the same period. Despite the increase in patient contacts, the costs of care were found to remain essentially the same (about 75 British pounds sterling). Eight deaths were reported overall, including two triaged by the nurses, but none of the deaths were associated with the trial itself.

The overall implications of the study are positive, so long as there is already an established trust between the patient and the general practice clinic, according to Dr. Garey Mazowita, a family practice physician in Vancouver, B.C., who is participating in a telephone screening program for general practitioners in his home province.

“At the heart of the medical home model we are moving toward is the continuity of the relationship between the family care doctor and the patient, and the knowledge that if you do something over the phone that averts an office visit, you’ve still got the security of the relationship [to rely on],” Dr. Mazowita, who is also the president of the College of Family Physicians of Canada, said in an interview. “We think it’s fundamentally safer than if no relationship exists.”

Ms. Varley agreed that how general practice clinics, and in particular, the physicians, related to patients overall was important, but said that for the purpose of nurse-led call screening, it was important to note that while all triage call screening was shown in the study to be comparably safe, “the individual characteristics of nurses independently influenced how telephone triage was implemented.”

Neither Ms. Varley nor Dr. Mazowita had any relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK – Nurses who lacked confidence as telephone triage advisers were more likely than more confident nurses to elevate the triage level of patients calling general practice clinics for same-day service, according to a British report.

The findings have implications for busy general practice physicians who are considering such programs to help ease their daily patient load.

Although there is “broad public support” in Britain for nurse practitioners and general nursing staff taking on many of the tasks usually associated with general practitioners, the manner in which these nurses handle patients varies greatly, according to Anna Varley, a social worker and researcher at the University of East Anglia, Norwich, England, who spoke at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

“Previous research is still equivocal as to explaining exactly why it is that different health professionals make different decisions about the same calls,” Ms. Varley said to a capacity crowd.

However, data from a randomized, controlled study of telephone triage services indicated that a nurse’s self-reported level of preparedness, was key to how – and if – she advised that callers receive follow-up care.

“Therefore, standardized telephone triage training is necessary, but it may not be sufficient,” Ms. Varley said.

The data were part of the larger, clustered, randomized controlled ESTEEM trial conducted across four regions in the United Kingdom between March 2011 and March 2013 to examine the outcomes and cost-effectiveness of telephone triage services. In the study, patients seeking same-day consultations were randomly assigned with intention to treat and by protocol, to either general practice–led phone triage care; nurse practitioner–led, computer-supported phone triage care; or usual practice. Allocation was not blinded to patients, clinicians, or researchers, but practice assignment was concealed from the study’s statistician. In all, 20,990 patient calls were managed by 42 general care clinics, with 77% of all patient-clinician interactions reaching the primary outcome of additional follow-up within 28 days of the initial call. The results of the larger trial were published recently in the Lancet (2014 Nov. 22 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61058-8]). For the subanalysis, Ms. Varley and her coinvestigators evaluated the 7,012 patient calls randomly routed to triage intervention from 45 nurses across 15 general practices in the four regions. All of the nursing staff were women, and all had been trained in the use of the clinical decision support software. All nurses were surveyed to discover their levels of training, experience, and facility with triage software. Thirty-five of the original 45 nurses returned valid profiles.

Of these, eight were nurse practitioners, an important distinction given that in the United Kingdom, this denotes more years of formal medical training than other nursing professionals, the authority to diagnose, and typically, the authority to prescribe medication.

The remaining 27 nurses were what are known in Britain as “practice nurses.” This group is not authorized to prescribe, and generally has less authority in other matters as well.

The range of the two groups of nurses’ years of experience was 2.5-40 years, although 89% of all nurse participants had 10 or more years of practical experience; 69% had 20 or more years of experience.

Across both groups, nearly half had prior experience manning triage phone lines, although only 2 of the 35 women had ever used the clinical support software.

At the time of each call, the nurses were asked to rate how prepared they felt for the particulars of the call. These data were included when evaluating how often each nurse recommended a caller for follow-up. Although most calls (86%) were recommended to some form of follow-up, nurse practitioners were less likely than practice nurses to recommend follow-up care (odds ratio, 0.19; confidence interval, 0.07-0.49). Across both groups, nurses who reported less confidence in their ability to manage the call were found more likely to recommend patients for follow-up (OR, 3.17; CI, 1.18-5.55). Additionally, less seasoned nurses, defined as those with 10 or less years of practical experience, had significantly longer mean call durations (OR, 2.58; CI, 0.76-4.40).

As reported in the larger ESTEEM trial, nurse-led triage resulted in an overall 48% increase in patient contacts over a 28-day period, compared with usual care. General practice physician–led triage resulted in a 33% increase over usual care during the same period. Despite the increase in patient contacts, the costs of care were found to remain essentially the same (about 75 British pounds sterling). Eight deaths were reported overall, including two triaged by the nurses, but none of the deaths were associated with the trial itself.

The overall implications of the study are positive, so long as there is already an established trust between the patient and the general practice clinic, according to Dr. Garey Mazowita, a family practice physician in Vancouver, B.C., who is participating in a telephone screening program for general practitioners in his home province.

“At the heart of the medical home model we are moving toward is the continuity of the relationship between the family care doctor and the patient, and the knowledge that if you do something over the phone that averts an office visit, you’ve still got the security of the relationship [to rely on],” Dr. Mazowita, who is also the president of the College of Family Physicians of Canada, said in an interview. “We think it’s fundamentally safer than if no relationship exists.”

Ms. Varley agreed that how general practice clinics, and in particular, the physicians, related to patients overall was important, but said that for the purpose of nurse-led call screening, it was important to note that while all triage call screening was shown in the study to be comparably safe, “the individual characteristics of nurses independently influenced how telephone triage was implemented.”

Neither Ms. Varley nor Dr. Mazowita had any relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT NAPCRG 2014

Key clinical point: Telephone triage training may not be enough to help nursing staff adequately manage callers seeking same-day consultations from general practice physicians.

Major finding: Nurses with more advanced medical training and higher levels of self-reported confidence about triage calls were less likely to recommend follow-up, compared with nurses with fewer years of formal education and less confidence in their skills (OR, 0.19, 3.17 respectively).

Data source: Telephone triage data from a randomized, controlled trial of 7,012 patient calls managed by 45 nurses across 15 general practice clinics in the United Kingdom.

Disclosures: Neither Ms. Varley nor Dr. Mazowita had any relevant disclosures.

Patient-centered medical homes bested others in chronic pain management

NEW YORK– Certified patient-centered medical homes were significantly more likely to adhere to pain management guidelines than were uncredentialed primary care practices, a retrospective study has shown.

Because patient-centered medical homes are predicated on safety and quality, coordination and integration, Dr. Nancy C. Elder, professor and director of research in the department of family and community medicine at the University of Cincinnati, said that they were already focused on primary care pain process guidelines for managing musculoskeletal pain established in 2011.

“A team, multidisciplinary approach to care, typical of a medical home, is generally associated with better pain outcomes,” Dr. Elder told a standing-room only crowd at the chronic pain research track of the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Still, there are few data to support a direct correlation between patient-centered medical home (PCMH) protocols as defined by the National Committee for Quality Assurance and how chronic pain is managed.

To address that gap, Dr. Elder and her associates conducted a random review of 485 charts of chronic pain patients seen at least twice at one of 12 academic-affiliated primary care practices in a 12-month period. Three of the practices had achieved PCMH certification in 2010, five were certified in 2013 prior to the study, and four clinics had no medical home certification. There was one internal medicine residency, while the rest were a combination of either family and internal medicine or internal medicine and pediatrics practices. Between 6 to 15 charts were reviewed per provider, although per office the range was between 10 and 95 charts. Charts from experienced PCMH clinics numbered 128, while newer PCMH-certified-clinic charts numbered 242. There were 115 non–PCMH clinic chart reviews.

Patients across all three clinic groups ranged in age from 56 years to 61.6 years and were predominantly white women.

The non-PCMH offices, when compared with the certified clinics, were significantly less likely to document four of eight key data points to assess and manage chronic pain, including a patient’s pain severity (39% vs. 75%, P less than .001), functional disability (41% vs. 66%, P less than .001), psychosocial distress (38% vs. 54%, P = .01), or substance abuse (13% vs. 32%, P less than .001).

All clinics were inclined to address depression and employ nonpharmacologic approaches to pain, although opioids were prescribed chronically 57% of the time, regardless of PCMH certification status. All clinics were equally likely to ask patients to enter into an opioid-use contract, but noncertified practices were less likely to assess patients for the side effects of opioid use (56% vs. 68%, P = .02), perform a urine drug screen (27% vs. 48%), or review a state controlled-prescription report (38% vs. 50%, P = .005).

Although Dr. Elder concluded that the medical home model is conducive to better chronic pain management, the actual relationship between protocols and patient outcomes is still unknown. She also noted that, although there was not a statistically significant difference, practices that had been PCMH certified the longest did not perform as well as the practices with newer certification.

“That raised the question about whether some of the skills and benefits of becoming a PCMH wane with time,” she said.

Dr. Elder did not state any relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK– Certified patient-centered medical homes were significantly more likely to adhere to pain management guidelines than were uncredentialed primary care practices, a retrospective study has shown.

Because patient-centered medical homes are predicated on safety and quality, coordination and integration, Dr. Nancy C. Elder, professor and director of research in the department of family and community medicine at the University of Cincinnati, said that they were already focused on primary care pain process guidelines for managing musculoskeletal pain established in 2011.

“A team, multidisciplinary approach to care, typical of a medical home, is generally associated with better pain outcomes,” Dr. Elder told a standing-room only crowd at the chronic pain research track of the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Still, there are few data to support a direct correlation between patient-centered medical home (PCMH) protocols as defined by the National Committee for Quality Assurance and how chronic pain is managed.

To address that gap, Dr. Elder and her associates conducted a random review of 485 charts of chronic pain patients seen at least twice at one of 12 academic-affiliated primary care practices in a 12-month period. Three of the practices had achieved PCMH certification in 2010, five were certified in 2013 prior to the study, and four clinics had no medical home certification. There was one internal medicine residency, while the rest were a combination of either family and internal medicine or internal medicine and pediatrics practices. Between 6 to 15 charts were reviewed per provider, although per office the range was between 10 and 95 charts. Charts from experienced PCMH clinics numbered 128, while newer PCMH-certified-clinic charts numbered 242. There were 115 non–PCMH clinic chart reviews.

Patients across all three clinic groups ranged in age from 56 years to 61.6 years and were predominantly white women.

The non-PCMH offices, when compared with the certified clinics, were significantly less likely to document four of eight key data points to assess and manage chronic pain, including a patient’s pain severity (39% vs. 75%, P less than .001), functional disability (41% vs. 66%, P less than .001), psychosocial distress (38% vs. 54%, P = .01), or substance abuse (13% vs. 32%, P less than .001).

All clinics were inclined to address depression and employ nonpharmacologic approaches to pain, although opioids were prescribed chronically 57% of the time, regardless of PCMH certification status. All clinics were equally likely to ask patients to enter into an opioid-use contract, but noncertified practices were less likely to assess patients for the side effects of opioid use (56% vs. 68%, P = .02), perform a urine drug screen (27% vs. 48%), or review a state controlled-prescription report (38% vs. 50%, P = .005).

Although Dr. Elder concluded that the medical home model is conducive to better chronic pain management, the actual relationship between protocols and patient outcomes is still unknown. She also noted that, although there was not a statistically significant difference, practices that had been PCMH certified the longest did not perform as well as the practices with newer certification.

“That raised the question about whether some of the skills and benefits of becoming a PCMH wane with time,” she said.

Dr. Elder did not state any relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK– Certified patient-centered medical homes were significantly more likely to adhere to pain management guidelines than were uncredentialed primary care practices, a retrospective study has shown.

Because patient-centered medical homes are predicated on safety and quality, coordination and integration, Dr. Nancy C. Elder, professor and director of research in the department of family and community medicine at the University of Cincinnati, said that they were already focused on primary care pain process guidelines for managing musculoskeletal pain established in 2011.

“A team, multidisciplinary approach to care, typical of a medical home, is generally associated with better pain outcomes,” Dr. Elder told a standing-room only crowd at the chronic pain research track of the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Still, there are few data to support a direct correlation between patient-centered medical home (PCMH) protocols as defined by the National Committee for Quality Assurance and how chronic pain is managed.

To address that gap, Dr. Elder and her associates conducted a random review of 485 charts of chronic pain patients seen at least twice at one of 12 academic-affiliated primary care practices in a 12-month period. Three of the practices had achieved PCMH certification in 2010, five were certified in 2013 prior to the study, and four clinics had no medical home certification. There was one internal medicine residency, while the rest were a combination of either family and internal medicine or internal medicine and pediatrics practices. Between 6 to 15 charts were reviewed per provider, although per office the range was between 10 and 95 charts. Charts from experienced PCMH clinics numbered 128, while newer PCMH-certified-clinic charts numbered 242. There were 115 non–PCMH clinic chart reviews.

Patients across all three clinic groups ranged in age from 56 years to 61.6 years and were predominantly white women.

The non-PCMH offices, when compared with the certified clinics, were significantly less likely to document four of eight key data points to assess and manage chronic pain, including a patient’s pain severity (39% vs. 75%, P less than .001), functional disability (41% vs. 66%, P less than .001), psychosocial distress (38% vs. 54%, P = .01), or substance abuse (13% vs. 32%, P less than .001).

All clinics were inclined to address depression and employ nonpharmacologic approaches to pain, although opioids were prescribed chronically 57% of the time, regardless of PCMH certification status. All clinics were equally likely to ask patients to enter into an opioid-use contract, but noncertified practices were less likely to assess patients for the side effects of opioid use (56% vs. 68%, P = .02), perform a urine drug screen (27% vs. 48%), or review a state controlled-prescription report (38% vs. 50%, P = .005).

Although Dr. Elder concluded that the medical home model is conducive to better chronic pain management, the actual relationship between protocols and patient outcomes is still unknown. She also noted that, although there was not a statistically significant difference, practices that had been PCMH certified the longest did not perform as well as the practices with newer certification.

“That raised the question about whether some of the skills and benefits of becoming a PCMH wane with time,” she said.

Dr. Elder did not state any relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT NAPCRG 2014

Key clinical point: A patient-centered medical home model may be better at treating patients according to primary care pain management guidelines.

Major finding: Patient-centered medical home certification was associated with significantly more evidence-based chronic pain management protocols.

Data source: Chart review of chronic pain patients seen at 12 academic-affiliated primary care practices over 12 months.

Disclosures: Dr. Elder did not state any relevant disclosures.

PODCAST: Medical home model connects patients, docs via phone, e-mail

NEW YORK – A Canadian pilot program encourages patients and primary care physicians to communicate as often as necessary by phone or e-mail, rather than always in person, to improve continuity of care.

“We believe that if one has continuity of care, one can be a lot more creative in delivery models,” explained Dr. Garey Mazowita, president of the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group, Dr. Mazowita outlined the pilot program’s rationale and implementation, and he discussed the key role that trust between patient and physician plays in the success of such a program.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK – A Canadian pilot program encourages patients and primary care physicians to communicate as often as necessary by phone or e-mail, rather than always in person, to improve continuity of care.

“We believe that if one has continuity of care, one can be a lot more creative in delivery models,” explained Dr. Garey Mazowita, president of the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group, Dr. Mazowita outlined the pilot program’s rationale and implementation, and he discussed the key role that trust between patient and physician plays in the success of such a program.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

NEW YORK – A Canadian pilot program encourages patients and primary care physicians to communicate as often as necessary by phone or e-mail, rather than always in person, to improve continuity of care.

“We believe that if one has continuity of care, one can be a lot more creative in delivery models,” explained Dr. Garey Mazowita, president of the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group, Dr. Mazowita outlined the pilot program’s rationale and implementation, and he discussed the key role that trust between patient and physician plays in the success of such a program.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM NAPCRG 2014

VIDEO: Family physicians can fill rural maternity care gaps

NEW YORK– Rather than relying on more obstetricians to practice in rural settings with limited access to maternity care, family physicians should be trusted to provide “excellent, quality care” to expectant mothers living in less populated areas – including delivering babies by cesarean section.

That’s the recommendation of Dr. Richard A. Young, director of research in family medicine at John Peters Smith Hospital, Fort Worth, Tex.

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group, Dr. Young talked about the role family physicians can play in providing quality obstetrical care in underserved areas, and how they can collaborate with local obstetricians to ensure quality care even in complex cases.