User login

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM): Annual Meeting (The Pregnancy Meeting)

Video: Cervicovaginal microbiome implicated in some preterm births

NEW ORLEANS – Could the cervicovaginal microbiome be responsible for some preterm births?

In a video interview, Dr. Michal Elovitz of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, discussed a study exploring the role the microbiome plays in high-risk pregnancies and preterm births, and she outlines how better understanding could reshape clinical practice.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEW ORLEANS – Could the cervicovaginal microbiome be responsible for some preterm births?

In a video interview, Dr. Michal Elovitz of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, discussed a study exploring the role the microbiome plays in high-risk pregnancies and preterm births, and she outlines how better understanding could reshape clinical practice.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEW ORLEANS – Could the cervicovaginal microbiome be responsible for some preterm births?

In a video interview, Dr. Michal Elovitz of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, discussed a study exploring the role the microbiome plays in high-risk pregnancies and preterm births, and she outlines how better understanding could reshape clinical practice.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE SMFM ANNUAL PREGNANCY MEETING

Video: What can be done to reverse rise in C-sections?

NEW ORLEANS – The rate of cesarean section in the United States has risen dramatically in the past 2 decades, accounting for 30% of all deliveries in 2011.

Several factors are driving the increase, according to the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, which sponsored the annual Pregnancy Meeting. Women are waiting until later in life to have children, and their obesity rates are higher than ever before – both of which increase the risk of medical complications during pregnancy. Fear of malpractice also motivates some ob.gyns. to rely on C-sections.

But the most common reason for a woman to have a C-section is that she has had one before, explained Dr. George Saade, director of the division of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. In a video interview, Dr. Saade discussed what’s fueling the rise, and what physicians must do to reduce C-section rates.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEW ORLEANS – The rate of cesarean section in the United States has risen dramatically in the past 2 decades, accounting for 30% of all deliveries in 2011.

Several factors are driving the increase, according to the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, which sponsored the annual Pregnancy Meeting. Women are waiting until later in life to have children, and their obesity rates are higher than ever before – both of which increase the risk of medical complications during pregnancy. Fear of malpractice also motivates some ob.gyns. to rely on C-sections.

But the most common reason for a woman to have a C-section is that she has had one before, explained Dr. George Saade, director of the division of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. In a video interview, Dr. Saade discussed what’s fueling the rise, and what physicians must do to reduce C-section rates.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEW ORLEANS – The rate of cesarean section in the United States has risen dramatically in the past 2 decades, accounting for 30% of all deliveries in 2011.

Several factors are driving the increase, according to the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, which sponsored the annual Pregnancy Meeting. Women are waiting until later in life to have children, and their obesity rates are higher than ever before – both of which increase the risk of medical complications during pregnancy. Fear of malpractice also motivates some ob.gyns. to rely on C-sections.

But the most common reason for a woman to have a C-section is that she has had one before, explained Dr. George Saade, director of the division of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. In a video interview, Dr. Saade discussed what’s fueling the rise, and what physicians must do to reduce C-section rates.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Learning and feedback reduce cesarean section rate

NEW ORLEANS – A training program that continually reinforced best practices for labor and delivery reduced the risk of cesarean section by 10% overall, and by up to 32% in a subgroup of high-risk pregnancies.

The program also significantly improved newborn outcomes, with a 12% decrease in the rate of major neonatal morbidity, Dr. Nils Chaillet reported at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The neonatal benefit remained significant even after excluding all preterm births from the analysis, said Dr. Chaillet of the Sainte-Justine University Hospital Research Center, Montreal.

The QUARISMA (Quality of Care, Management of Obstetrical Risk, and Mode of Delivery in Quebec) study examined the effects of a clinician training program designed to promote optimal management of labor and delivery. QUARISMA was a multifaceted evidence-medicine program based on audit, feedback, and educational activities that followed the World Health Organization guidelines for quality obstetrical care.

A 2-day training session at each participating hospital introduced the program. Throughout the 3.5-year study, a local audit committee, headed by a peer-selected leader, regularly evaluated performance and provided feedback on results and suggestions on quality improvement. These audits were conducted every 3 months. They included an analysis of each cesarean case, centering on whether and how it could have been prevented.

The study randomized 32 public hospitals in Quebec to the intervention or to a control arm of usual practice. The hospitals all had a cesarean section rate of at least 17% and no prior program aimed at reducing that rate. They had to perform more than 300 deliveries annually. All women who gave birth to an infant of at least 500 grams and 24 weeks’ gestation were included in the study.

A total of 105,351 deliveries occurred. In the control group, the baseline rate of cesarean section was 23%; that remained unchanged. The rate did decrease in the intervention group, dropping from 22.5% at baseline to 21.8% at study’s end – a 10% risk reduction that was statistically significant.

Women with low-risk pregnancies experienced a considerable benefit, Dr. Chaillet noted, with an overall risk reduction of 20%. That varied among hospital type. It was smallest (2%) at community hospitals, followed by 21% at regional hospitals and 24% at tertiary care hospitals.

Among high-risk pregnancies, the risk of a cesarean decreased by 4% overall. It did not change in tertiary care centers, but decreased by 5% at regional hospitals and 32% at community hospitals.

Medical interventions were a secondary endpoint. There were no changes in the rates of episiotomy, epidurals, or artificial rupture of membranes. However, the risk of operative vaginal delivery dropped by 12%, and pharmacologic labor induction by 18%. The odds of using oxytocin during labor increased by16%.

There were no significant changes in the composite measures of minor or major maternal morbidities. But neonatal outcomes did improve. The risk of a minor neonatal morbidity decreased by a significant 12%; the risk of a major problem decreased by 19%.

Dr. Chaillet made no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

NEW ORLEANS – A training program that continually reinforced best practices for labor and delivery reduced the risk of cesarean section by 10% overall, and by up to 32% in a subgroup of high-risk pregnancies.

The program also significantly improved newborn outcomes, with a 12% decrease in the rate of major neonatal morbidity, Dr. Nils Chaillet reported at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The neonatal benefit remained significant even after excluding all preterm births from the analysis, said Dr. Chaillet of the Sainte-Justine University Hospital Research Center, Montreal.

The QUARISMA (Quality of Care, Management of Obstetrical Risk, and Mode of Delivery in Quebec) study examined the effects of a clinician training program designed to promote optimal management of labor and delivery. QUARISMA was a multifaceted evidence-medicine program based on audit, feedback, and educational activities that followed the World Health Organization guidelines for quality obstetrical care.

A 2-day training session at each participating hospital introduced the program. Throughout the 3.5-year study, a local audit committee, headed by a peer-selected leader, regularly evaluated performance and provided feedback on results and suggestions on quality improvement. These audits were conducted every 3 months. They included an analysis of each cesarean case, centering on whether and how it could have been prevented.

The study randomized 32 public hospitals in Quebec to the intervention or to a control arm of usual practice. The hospitals all had a cesarean section rate of at least 17% and no prior program aimed at reducing that rate. They had to perform more than 300 deliveries annually. All women who gave birth to an infant of at least 500 grams and 24 weeks’ gestation were included in the study.

A total of 105,351 deliveries occurred. In the control group, the baseline rate of cesarean section was 23%; that remained unchanged. The rate did decrease in the intervention group, dropping from 22.5% at baseline to 21.8% at study’s end – a 10% risk reduction that was statistically significant.

Women with low-risk pregnancies experienced a considerable benefit, Dr. Chaillet noted, with an overall risk reduction of 20%. That varied among hospital type. It was smallest (2%) at community hospitals, followed by 21% at regional hospitals and 24% at tertiary care hospitals.

Among high-risk pregnancies, the risk of a cesarean decreased by 4% overall. It did not change in tertiary care centers, but decreased by 5% at regional hospitals and 32% at community hospitals.

Medical interventions were a secondary endpoint. There were no changes in the rates of episiotomy, epidurals, or artificial rupture of membranes. However, the risk of operative vaginal delivery dropped by 12%, and pharmacologic labor induction by 18%. The odds of using oxytocin during labor increased by16%.

There were no significant changes in the composite measures of minor or major maternal morbidities. But neonatal outcomes did improve. The risk of a minor neonatal morbidity decreased by a significant 12%; the risk of a major problem decreased by 19%.

Dr. Chaillet made no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

NEW ORLEANS – A training program that continually reinforced best practices for labor and delivery reduced the risk of cesarean section by 10% overall, and by up to 32% in a subgroup of high-risk pregnancies.

The program also significantly improved newborn outcomes, with a 12% decrease in the rate of major neonatal morbidity, Dr. Nils Chaillet reported at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The neonatal benefit remained significant even after excluding all preterm births from the analysis, said Dr. Chaillet of the Sainte-Justine University Hospital Research Center, Montreal.

The QUARISMA (Quality of Care, Management of Obstetrical Risk, and Mode of Delivery in Quebec) study examined the effects of a clinician training program designed to promote optimal management of labor and delivery. QUARISMA was a multifaceted evidence-medicine program based on audit, feedback, and educational activities that followed the World Health Organization guidelines for quality obstetrical care.

A 2-day training session at each participating hospital introduced the program. Throughout the 3.5-year study, a local audit committee, headed by a peer-selected leader, regularly evaluated performance and provided feedback on results and suggestions on quality improvement. These audits were conducted every 3 months. They included an analysis of each cesarean case, centering on whether and how it could have been prevented.

The study randomized 32 public hospitals in Quebec to the intervention or to a control arm of usual practice. The hospitals all had a cesarean section rate of at least 17% and no prior program aimed at reducing that rate. They had to perform more than 300 deliveries annually. All women who gave birth to an infant of at least 500 grams and 24 weeks’ gestation were included in the study.

A total of 105,351 deliveries occurred. In the control group, the baseline rate of cesarean section was 23%; that remained unchanged. The rate did decrease in the intervention group, dropping from 22.5% at baseline to 21.8% at study’s end – a 10% risk reduction that was statistically significant.

Women with low-risk pregnancies experienced a considerable benefit, Dr. Chaillet noted, with an overall risk reduction of 20%. That varied among hospital type. It was smallest (2%) at community hospitals, followed by 21% at regional hospitals and 24% at tertiary care hospitals.

Among high-risk pregnancies, the risk of a cesarean decreased by 4% overall. It did not change in tertiary care centers, but decreased by 5% at regional hospitals and 32% at community hospitals.

Medical interventions were a secondary endpoint. There were no changes in the rates of episiotomy, epidurals, or artificial rupture of membranes. However, the risk of operative vaginal delivery dropped by 12%, and pharmacologic labor induction by 18%. The odds of using oxytocin during labor increased by16%.

There were no significant changes in the composite measures of minor or major maternal morbidities. But neonatal outcomes did improve. The risk of a minor neonatal morbidity decreased by a significant 12%; the risk of a major problem decreased by 19%.

Dr. Chaillet made no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Major finding: Among high-risk pregnancies, the risk of a cesarean decreased by 4% overall. It did not change in tertiary care centers, but decreased by 5% at regional hospitals and 32% at community hospitals.

Data source: The study randomized 32 hospitals and tracked outcomes in more than 100,000 births.

Disclosures: Dr. Chaillet had no financial disclosures.

Intra-amniotic debris associated with preterm birth, not growth restriction

NEW ORLEANS – Intra-amniotic debris can portend a preterm birth, but doesn’t seem to be associated with any other adverse pregnancy outcomes, including small-for-gestational-age infants.

The debris – a mix of bacterial and inflammatory cells encased in an antibiotic-resistant biofilm – may actually trigger an early birth to help protect the fetus, Dr. George R. Saade said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The debris is associated with placental senescence, "which leads to preterm birth before there can be further fetal compromise and growth restriction," said Dr. Saade, director of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

He presented a secondary analysis of a study that examined the effect of progesterone injections to prevent preterm birth in nulliparous women with a short cervix.

The study was halted in October 2012, after preliminary results showed no treatment benefit.

The main outcome for the study was a composite of fetal death, small-for-gestational-age infants, placental abruption, and gestational hypertension/preeclampsia. Of the 657 randomized to progesterone or placebo, 78 were found to have intra-amniotic debris on ultrasound.

These women were significantly older than were those without debris (23 vs. 22 years), had a significantly higher prepregnancy body mass index (28 kg/m2 vs. 25 kg/m2), and a significantly shorter cervical length on ultrasound (19 vs. 24 cm).

There were significantly more infants born at less than 37 weeks’ gestation in women with debris (35% vs. 23%). But there was no significant between-group difference in the composite outcome. When Dr. Saade looked at the individual outcome measures, he found only one significant difference. Despite the larger number of preterm births, there were no small-for-gestational-age infants born to mothers with the debris. However, 5% of those without debris did have small-for-dates babies.

Dr. Saade had no financial declarations.

NEW ORLEANS – Intra-amniotic debris can portend a preterm birth, but doesn’t seem to be associated with any other adverse pregnancy outcomes, including small-for-gestational-age infants.

The debris – a mix of bacterial and inflammatory cells encased in an antibiotic-resistant biofilm – may actually trigger an early birth to help protect the fetus, Dr. George R. Saade said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The debris is associated with placental senescence, "which leads to preterm birth before there can be further fetal compromise and growth restriction," said Dr. Saade, director of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

He presented a secondary analysis of a study that examined the effect of progesterone injections to prevent preterm birth in nulliparous women with a short cervix.

The study was halted in October 2012, after preliminary results showed no treatment benefit.

The main outcome for the study was a composite of fetal death, small-for-gestational-age infants, placental abruption, and gestational hypertension/preeclampsia. Of the 657 randomized to progesterone or placebo, 78 were found to have intra-amniotic debris on ultrasound.

These women were significantly older than were those without debris (23 vs. 22 years), had a significantly higher prepregnancy body mass index (28 kg/m2 vs. 25 kg/m2), and a significantly shorter cervical length on ultrasound (19 vs. 24 cm).

There were significantly more infants born at less than 37 weeks’ gestation in women with debris (35% vs. 23%). But there was no significant between-group difference in the composite outcome. When Dr. Saade looked at the individual outcome measures, he found only one significant difference. Despite the larger number of preterm births, there were no small-for-gestational-age infants born to mothers with the debris. However, 5% of those without debris did have small-for-dates babies.

Dr. Saade had no financial declarations.

NEW ORLEANS – Intra-amniotic debris can portend a preterm birth, but doesn’t seem to be associated with any other adverse pregnancy outcomes, including small-for-gestational-age infants.

The debris – a mix of bacterial and inflammatory cells encased in an antibiotic-resistant biofilm – may actually trigger an early birth to help protect the fetus, Dr. George R. Saade said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The debris is associated with placental senescence, "which leads to preterm birth before there can be further fetal compromise and growth restriction," said Dr. Saade, director of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

He presented a secondary analysis of a study that examined the effect of progesterone injections to prevent preterm birth in nulliparous women with a short cervix.

The study was halted in October 2012, after preliminary results showed no treatment benefit.

The main outcome for the study was a composite of fetal death, small-for-gestational-age infants, placental abruption, and gestational hypertension/preeclampsia. Of the 657 randomized to progesterone or placebo, 78 were found to have intra-amniotic debris on ultrasound.

These women were significantly older than were those without debris (23 vs. 22 years), had a significantly higher prepregnancy body mass index (28 kg/m2 vs. 25 kg/m2), and a significantly shorter cervical length on ultrasound (19 vs. 24 cm).

There were significantly more infants born at less than 37 weeks’ gestation in women with debris (35% vs. 23%). But there was no significant between-group difference in the composite outcome. When Dr. Saade looked at the individual outcome measures, he found only one significant difference. Despite the larger number of preterm births, there were no small-for-gestational-age infants born to mothers with the debris. However, 5% of those without debris did have small-for-dates babies.

Dr. Saade had no financial declarations.

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Major finding: Preterm birth occurred in 35% of women who had intra-amniotic debris, but none of those infants were small for gestational age.

Data source: The analysis comprised 657 women.

Disclosures: Dr. George Saade had no financial disclosures.

For women with prior cesareans, 39-week delivery is not optimal

NEW ORLEANS – The safest time to deliver a woman with prior cesarean sections may be up to 2 weeks earlier than the current recommendation.

Guidelines from a number of national groups, including the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, recommend planning a cesarean delivery at 39 weeks for these women. But a retrospective study has determined that maternal risk increases sharply after 37 weeks for women who have had three or more cesarean deliveries – a full 2 weeks before there is any increase in fetal risk.

"The data clearly show that the optimal time for delivery in women with three or more prior cesareans is 37 weeks," Dr. Laura Hart said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Dr. Hart of the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, extracted her data from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Cesarean Section Registry. It contains prospective data on more than 24,000 deliveries performed after prior cesarean. She examined information on 6,435 deliveries that followed at least two prior cesareans (80% after two sections and 20% after three or more).

Dr. Hart analyzed both maternal and fetal outcomes. Each was a single composite comprising several endpoints. The maternal composite took into account transfusion, hysterectomy, operative injury, thromboembolic event, pulmonary edema, and death. The perinatal composite included respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis (grade 2 or 3), intraventricular hemorrhage (grade 3 or 4), hypoxic ischemic injury, seizure, and stillbirth or neonatal death.

The results were expressed as a risk of the composite event relative to the number of ongoing pregnancies.

Less than half of the women who had two prior cesareans delivered at 39 weeks (46%); 11% delivered at 37 weeks, 31% at 38 weeks, and 13% at 40 weeks or more.

For these women, the risk of maternal complications was less than 5 per 1,000 ongoing pregnancies at 37 weeks. It remained low at 38 weeks (about 7/1,000). But between 38 and 39 weeks, it rose sharply, to 16/1,000. The risk remained similarly elevated at 40 weeks and beyond.

The perinatal outcomes risk was low at 37 weeks (7/1,000) and remained low at 38 and 39 weeks (7 and 9/1,000, respectively). The risk also increased sharply between 38 and 39 weeks, rising to about 20/1,000. The maternal and perinatal risk curves intersected between weeks 37 and 38, indicating that 38 weeks was probably the optimal time for delivery.

Less than half of women who had at least three prior cesareans also made it to 39 weeks (41%). About a third (35%) delivered at 38 weeks, 15% at 37 weeks, and 9% at 40 weeks or more.

Again, maternal risk was very low at 37 weeks (about 4/1,000 ongoing pregnancies). But in contrast to the risk for women with two prior deliveries, the risk for these women increased sharply and linearly over the final weeks of gestation. By 38 weeks, it had jumped to about 16/1,000. By 39 weeks, it was close to 50/1,000, and by 40 weeks and beyond, more than 50/1,000.

Conversely, perinatal risk remained fairly low in weeks 37, 38, and 39 (9, 7, and 10/1,000, respectively). Risk accelerated between weeks 39 and 40; by week 40 and beyond, it hovered just above 25/1,000. The risk curves intersected between weeks 37 and 38, indicating that 37 weeks is the optimal time for delivery.

Dr. Hart added that maternal transfusion was the main risk driver for women, followed closely by operative injury and hysterectomy.

These data were published in a supplement to the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology (Amer. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;210(suppl.):S27).

Dr. Hart had no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – The safest time to deliver a woman with prior cesarean sections may be up to 2 weeks earlier than the current recommendation.

Guidelines from a number of national groups, including the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, recommend planning a cesarean delivery at 39 weeks for these women. But a retrospective study has determined that maternal risk increases sharply after 37 weeks for women who have had three or more cesarean deliveries – a full 2 weeks before there is any increase in fetal risk.

"The data clearly show that the optimal time for delivery in women with three or more prior cesareans is 37 weeks," Dr. Laura Hart said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Dr. Hart of the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, extracted her data from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Cesarean Section Registry. It contains prospective data on more than 24,000 deliveries performed after prior cesarean. She examined information on 6,435 deliveries that followed at least two prior cesareans (80% after two sections and 20% after three or more).

Dr. Hart analyzed both maternal and fetal outcomes. Each was a single composite comprising several endpoints. The maternal composite took into account transfusion, hysterectomy, operative injury, thromboembolic event, pulmonary edema, and death. The perinatal composite included respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis (grade 2 or 3), intraventricular hemorrhage (grade 3 or 4), hypoxic ischemic injury, seizure, and stillbirth or neonatal death.

The results were expressed as a risk of the composite event relative to the number of ongoing pregnancies.

Less than half of the women who had two prior cesareans delivered at 39 weeks (46%); 11% delivered at 37 weeks, 31% at 38 weeks, and 13% at 40 weeks or more.

For these women, the risk of maternal complications was less than 5 per 1,000 ongoing pregnancies at 37 weeks. It remained low at 38 weeks (about 7/1,000). But between 38 and 39 weeks, it rose sharply, to 16/1,000. The risk remained similarly elevated at 40 weeks and beyond.

The perinatal outcomes risk was low at 37 weeks (7/1,000) and remained low at 38 and 39 weeks (7 and 9/1,000, respectively). The risk also increased sharply between 38 and 39 weeks, rising to about 20/1,000. The maternal and perinatal risk curves intersected between weeks 37 and 38, indicating that 38 weeks was probably the optimal time for delivery.

Less than half of women who had at least three prior cesareans also made it to 39 weeks (41%). About a third (35%) delivered at 38 weeks, 15% at 37 weeks, and 9% at 40 weeks or more.

Again, maternal risk was very low at 37 weeks (about 4/1,000 ongoing pregnancies). But in contrast to the risk for women with two prior deliveries, the risk for these women increased sharply and linearly over the final weeks of gestation. By 38 weeks, it had jumped to about 16/1,000. By 39 weeks, it was close to 50/1,000, and by 40 weeks and beyond, more than 50/1,000.

Conversely, perinatal risk remained fairly low in weeks 37, 38, and 39 (9, 7, and 10/1,000, respectively). Risk accelerated between weeks 39 and 40; by week 40 and beyond, it hovered just above 25/1,000. The risk curves intersected between weeks 37 and 38, indicating that 37 weeks is the optimal time for delivery.

Dr. Hart added that maternal transfusion was the main risk driver for women, followed closely by operative injury and hysterectomy.

These data were published in a supplement to the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology (Amer. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;210(suppl.):S27).

Dr. Hart had no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – The safest time to deliver a woman with prior cesarean sections may be up to 2 weeks earlier than the current recommendation.

Guidelines from a number of national groups, including the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, recommend planning a cesarean delivery at 39 weeks for these women. But a retrospective study has determined that maternal risk increases sharply after 37 weeks for women who have had three or more cesarean deliveries – a full 2 weeks before there is any increase in fetal risk.

"The data clearly show that the optimal time for delivery in women with three or more prior cesareans is 37 weeks," Dr. Laura Hart said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Dr. Hart of the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, extracted her data from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Cesarean Section Registry. It contains prospective data on more than 24,000 deliveries performed after prior cesarean. She examined information on 6,435 deliveries that followed at least two prior cesareans (80% after two sections and 20% after three or more).

Dr. Hart analyzed both maternal and fetal outcomes. Each was a single composite comprising several endpoints. The maternal composite took into account transfusion, hysterectomy, operative injury, thromboembolic event, pulmonary edema, and death. The perinatal composite included respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis (grade 2 or 3), intraventricular hemorrhage (grade 3 or 4), hypoxic ischemic injury, seizure, and stillbirth or neonatal death.

The results were expressed as a risk of the composite event relative to the number of ongoing pregnancies.

Less than half of the women who had two prior cesareans delivered at 39 weeks (46%); 11% delivered at 37 weeks, 31% at 38 weeks, and 13% at 40 weeks or more.

For these women, the risk of maternal complications was less than 5 per 1,000 ongoing pregnancies at 37 weeks. It remained low at 38 weeks (about 7/1,000). But between 38 and 39 weeks, it rose sharply, to 16/1,000. The risk remained similarly elevated at 40 weeks and beyond.

The perinatal outcomes risk was low at 37 weeks (7/1,000) and remained low at 38 and 39 weeks (7 and 9/1,000, respectively). The risk also increased sharply between 38 and 39 weeks, rising to about 20/1,000. The maternal and perinatal risk curves intersected between weeks 37 and 38, indicating that 38 weeks was probably the optimal time for delivery.

Less than half of women who had at least three prior cesareans also made it to 39 weeks (41%). About a third (35%) delivered at 38 weeks, 15% at 37 weeks, and 9% at 40 weeks or more.

Again, maternal risk was very low at 37 weeks (about 4/1,000 ongoing pregnancies). But in contrast to the risk for women with two prior deliveries, the risk for these women increased sharply and linearly over the final weeks of gestation. By 38 weeks, it had jumped to about 16/1,000. By 39 weeks, it was close to 50/1,000, and by 40 weeks and beyond, more than 50/1,000.

Conversely, perinatal risk remained fairly low in weeks 37, 38, and 39 (9, 7, and 10/1,000, respectively). Risk accelerated between weeks 39 and 40; by week 40 and beyond, it hovered just above 25/1,000. The risk curves intersected between weeks 37 and 38, indicating that 37 weeks is the optimal time for delivery.

Dr. Hart added that maternal transfusion was the main risk driver for women, followed closely by operative injury and hysterectomy.

These data were published in a supplement to the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology (Amer. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;210(suppl.):S27).

Dr. Hart had no financial disclosures.

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Major finding: The optimal time for delivery of women with two prior cesarean sections is 38 weeks; for women with three or more prior sections, it is 37 weeks.

Data source: The retrospective analysis comprised 6,435 women.

Disclosures: Dr. Laura Hart had no financial disclosures.

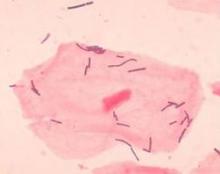

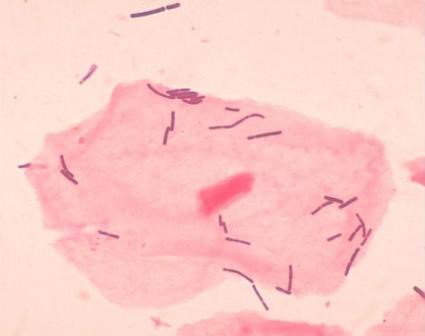

Preterm birth prevention – let’s get the bugs out

Screening for and treating bacterial vaginosis is a routine part of preterm birth prevention. A quick course of antibiotics for women with proven infection is easy and inexpensive – and if it works, a bullet with a huge bang for the buck.

Unfortunately, it just doesn’t seem to work.

A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial presented Feb. 6 at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine, found that clindamycin conferred no benefit on women with bacterial vaginosis (BV)who were at high risk for preterm birth.

The trial, held from May 2006 through June 2011, randomized 2,869 pregnant women at low risk for preterm birth to receive either one of two oral clindamycin regimens or placebo before 15 weeks’ gestation.

The study was complicated by the unexpectedly low preterm birth rate in the group that wasn’t treated, Dr. Gilles Brabant said at the meeting.

The study design assumed a 2% rate in the treated group and 4% rate in the nontreated group. The actual rate was extremely low and almost identical (1.2% in the treatment groups vs. 1% in the comparator group).

However, the power of calculation held in the final analysis, leading Dr. Brabant, of the University Hospital of Lille, France, to question just why the antibiotic wasn’t improving outcomes.

"We to have to ask ourselves, is BV the guilty party or might it be something else? We need to look further – to genetics, inflammatory response, and molecular biology – and perhaps even the microbiome."

Dr. Michal Elovitz said that she couldn’t agree more. In fact, during her presentation she said that it’s time to rethink the whole pathological paradigm of preterm birth.

The current concept starts with bacterial colonization that ascends to the cervix from the vagina, instigating an inflammatory response. The bacteria then propagate in the placenta, provoking another inflammatory response in the decidua and uterus. From there, they travel through the umbilical cord, getting the baby into the inflammation act.

"All of these serve to promote uterine contractions and degradation of the fetal membrane," said Dr. Elovitz of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. "In this model, contractions are the primary event leading to delivery – cervical remodeling is a secondary event."

But this model doesn’t explain why antibiotic trials fail to demonstrate any effect on preterm birth. In the face of these repeat failures, Dr. Elovitz said, "We need to ask if bacterial ascension into the uterus is a necessary pathogenesis for preterm birth."

She’s not letting bacteria off the hook, but she is suggesting that they may affect pregnancy outcomes in a much different way – through the collective influence of their communities at the cervicovaginal junction.

Dr. Elovitz’s research has identified four distinct communities that can populate the cervicovaginal space. Three of these are dominated by different species of lactobacilli – a species never before associated with preterm birth. The fourth lacks lactobacilli; it’s largely composed of the anaerobes that have typically been associated with BV.

She said she thinks it’s time for a new pathogenic model for preterm birth.

"We propose that the microbiota – specifically a dysbiotic community in the cervicovaginal space – may induce cervical remodeling through the interaction of the microbiota, the cervical-epithelial barrier, and the immune system," she said.

She investigated this by looking at 77 cervicovaginal samples*. Of these, 21 belonged to women who went on to have a preterm birth. The samples were obtained at 20-24 weeks and 24-28 weeks’ gestation, and genotyped to discover the exact nature of all their bacterial inhabitants. She found 168 phylotypes, and went on to focus on the 50 that were most frequently present in all samples.

The women who had term and preterm deliveries were demographically similar, except that in the first gestational period, cervical length was already significantly shorter in women destined for a preterm delivery – a hint that something was going on months before any symptoms developed.

It turns out that a single species of lactobacillus – L. iners – dominated the samples of almost all of the women who eventually had a preterm delivery. Women who had term pregnancies were significantly less likely to have that group. In fact, their samples were about evenly split between groups headed by L. crispatus and the Lactobacilli-absent anaerobes.

Lactobacilli generally aren’t thought of as bad guys, Dr. Elovitz said. But emerging data suggest that some strains aren’t so mild-mannered. "We know from nonpregnant data that there are different strains that are either pro- or negative immune mediators," which may play into the preterm birth puzzle.

"Lactobacillus also has mutations that can produce a much less favorable mucin, and if you have those mutations you are much more prone to acquire sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infections."

The good news is that while antibiotics may not be the key to this puzzle, the microbiome can be modified. For example, a plant-based diet has been found to change the microbiota associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

It’s not clear yet if, or how, the cervicovaginal communities could be modulated to protect against preterm birth. But it is clear that the well-trod path of antibiotics just isn’t getting the results researchers, doctors, mothers, and babies need.

Neither Dr. Brabant nor Dr. Elovitz had any financial declarations.

*Correction, 2/7/2014: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the number of cervicovaginal samples.

Screening for and treating bacterial vaginosis is a routine part of preterm birth prevention. A quick course of antibiotics for women with proven infection is easy and inexpensive – and if it works, a bullet with a huge bang for the buck.

Unfortunately, it just doesn’t seem to work.

A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial presented Feb. 6 at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine, found that clindamycin conferred no benefit on women with bacterial vaginosis (BV)who were at high risk for preterm birth.

The trial, held from May 2006 through June 2011, randomized 2,869 pregnant women at low risk for preterm birth to receive either one of two oral clindamycin regimens or placebo before 15 weeks’ gestation.

The study was complicated by the unexpectedly low preterm birth rate in the group that wasn’t treated, Dr. Gilles Brabant said at the meeting.

The study design assumed a 2% rate in the treated group and 4% rate in the nontreated group. The actual rate was extremely low and almost identical (1.2% in the treatment groups vs. 1% in the comparator group).

However, the power of calculation held in the final analysis, leading Dr. Brabant, of the University Hospital of Lille, France, to question just why the antibiotic wasn’t improving outcomes.

"We to have to ask ourselves, is BV the guilty party or might it be something else? We need to look further – to genetics, inflammatory response, and molecular biology – and perhaps even the microbiome."

Dr. Michal Elovitz said that she couldn’t agree more. In fact, during her presentation she said that it’s time to rethink the whole pathological paradigm of preterm birth.

The current concept starts with bacterial colonization that ascends to the cervix from the vagina, instigating an inflammatory response. The bacteria then propagate in the placenta, provoking another inflammatory response in the decidua and uterus. From there, they travel through the umbilical cord, getting the baby into the inflammation act.

"All of these serve to promote uterine contractions and degradation of the fetal membrane," said Dr. Elovitz of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. "In this model, contractions are the primary event leading to delivery – cervical remodeling is a secondary event."

But this model doesn’t explain why antibiotic trials fail to demonstrate any effect on preterm birth. In the face of these repeat failures, Dr. Elovitz said, "We need to ask if bacterial ascension into the uterus is a necessary pathogenesis for preterm birth."

She’s not letting bacteria off the hook, but she is suggesting that they may affect pregnancy outcomes in a much different way – through the collective influence of their communities at the cervicovaginal junction.

Dr. Elovitz’s research has identified four distinct communities that can populate the cervicovaginal space. Three of these are dominated by different species of lactobacilli – a species never before associated with preterm birth. The fourth lacks lactobacilli; it’s largely composed of the anaerobes that have typically been associated with BV.

She said she thinks it’s time for a new pathogenic model for preterm birth.

"We propose that the microbiota – specifically a dysbiotic community in the cervicovaginal space – may induce cervical remodeling through the interaction of the microbiota, the cervical-epithelial barrier, and the immune system," she said.

She investigated this by looking at 77 cervicovaginal samples*. Of these, 21 belonged to women who went on to have a preterm birth. The samples were obtained at 20-24 weeks and 24-28 weeks’ gestation, and genotyped to discover the exact nature of all their bacterial inhabitants. She found 168 phylotypes, and went on to focus on the 50 that were most frequently present in all samples.

The women who had term and preterm deliveries were demographically similar, except that in the first gestational period, cervical length was already significantly shorter in women destined for a preterm delivery – a hint that something was going on months before any symptoms developed.

It turns out that a single species of lactobacillus – L. iners – dominated the samples of almost all of the women who eventually had a preterm delivery. Women who had term pregnancies were significantly less likely to have that group. In fact, their samples were about evenly split between groups headed by L. crispatus and the Lactobacilli-absent anaerobes.

Lactobacilli generally aren’t thought of as bad guys, Dr. Elovitz said. But emerging data suggest that some strains aren’t so mild-mannered. "We know from nonpregnant data that there are different strains that are either pro- or negative immune mediators," which may play into the preterm birth puzzle.

"Lactobacillus also has mutations that can produce a much less favorable mucin, and if you have those mutations you are much more prone to acquire sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infections."

The good news is that while antibiotics may not be the key to this puzzle, the microbiome can be modified. For example, a plant-based diet has been found to change the microbiota associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

It’s not clear yet if, or how, the cervicovaginal communities could be modulated to protect against preterm birth. But it is clear that the well-trod path of antibiotics just isn’t getting the results researchers, doctors, mothers, and babies need.

Neither Dr. Brabant nor Dr. Elovitz had any financial declarations.

*Correction, 2/7/2014: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the number of cervicovaginal samples.

Screening for and treating bacterial vaginosis is a routine part of preterm birth prevention. A quick course of antibiotics for women with proven infection is easy and inexpensive – and if it works, a bullet with a huge bang for the buck.

Unfortunately, it just doesn’t seem to work.

A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial presented Feb. 6 at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine, found that clindamycin conferred no benefit on women with bacterial vaginosis (BV)who were at high risk for preterm birth.

The trial, held from May 2006 through June 2011, randomized 2,869 pregnant women at low risk for preterm birth to receive either one of two oral clindamycin regimens or placebo before 15 weeks’ gestation.

The study was complicated by the unexpectedly low preterm birth rate in the group that wasn’t treated, Dr. Gilles Brabant said at the meeting.

The study design assumed a 2% rate in the treated group and 4% rate in the nontreated group. The actual rate was extremely low and almost identical (1.2% in the treatment groups vs. 1% in the comparator group).

However, the power of calculation held in the final analysis, leading Dr. Brabant, of the University Hospital of Lille, France, to question just why the antibiotic wasn’t improving outcomes.

"We to have to ask ourselves, is BV the guilty party or might it be something else? We need to look further – to genetics, inflammatory response, and molecular biology – and perhaps even the microbiome."

Dr. Michal Elovitz said that she couldn’t agree more. In fact, during her presentation she said that it’s time to rethink the whole pathological paradigm of preterm birth.

The current concept starts with bacterial colonization that ascends to the cervix from the vagina, instigating an inflammatory response. The bacteria then propagate in the placenta, provoking another inflammatory response in the decidua and uterus. From there, they travel through the umbilical cord, getting the baby into the inflammation act.

"All of these serve to promote uterine contractions and degradation of the fetal membrane," said Dr. Elovitz of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. "In this model, contractions are the primary event leading to delivery – cervical remodeling is a secondary event."

But this model doesn’t explain why antibiotic trials fail to demonstrate any effect on preterm birth. In the face of these repeat failures, Dr. Elovitz said, "We need to ask if bacterial ascension into the uterus is a necessary pathogenesis for preterm birth."

She’s not letting bacteria off the hook, but she is suggesting that they may affect pregnancy outcomes in a much different way – through the collective influence of their communities at the cervicovaginal junction.

Dr. Elovitz’s research has identified four distinct communities that can populate the cervicovaginal space. Three of these are dominated by different species of lactobacilli – a species never before associated with preterm birth. The fourth lacks lactobacilli; it’s largely composed of the anaerobes that have typically been associated with BV.

She said she thinks it’s time for a new pathogenic model for preterm birth.

"We propose that the microbiota – specifically a dysbiotic community in the cervicovaginal space – may induce cervical remodeling through the interaction of the microbiota, the cervical-epithelial barrier, and the immune system," she said.

She investigated this by looking at 77 cervicovaginal samples*. Of these, 21 belonged to women who went on to have a preterm birth. The samples were obtained at 20-24 weeks and 24-28 weeks’ gestation, and genotyped to discover the exact nature of all their bacterial inhabitants. She found 168 phylotypes, and went on to focus on the 50 that were most frequently present in all samples.

The women who had term and preterm deliveries were demographically similar, except that in the first gestational period, cervical length was already significantly shorter in women destined for a preterm delivery – a hint that something was going on months before any symptoms developed.

It turns out that a single species of lactobacillus – L. iners – dominated the samples of almost all of the women who eventually had a preterm delivery. Women who had term pregnancies were significantly less likely to have that group. In fact, their samples were about evenly split between groups headed by L. crispatus and the Lactobacilli-absent anaerobes.

Lactobacilli generally aren’t thought of as bad guys, Dr. Elovitz said. But emerging data suggest that some strains aren’t so mild-mannered. "We know from nonpregnant data that there are different strains that are either pro- or negative immune mediators," which may play into the preterm birth puzzle.

"Lactobacillus also has mutations that can produce a much less favorable mucin, and if you have those mutations you are much more prone to acquire sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infections."

The good news is that while antibiotics may not be the key to this puzzle, the microbiome can be modified. For example, a plant-based diet has been found to change the microbiota associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

It’s not clear yet if, or how, the cervicovaginal communities could be modulated to protect against preterm birth. But it is clear that the well-trod path of antibiotics just isn’t getting the results researchers, doctors, mothers, and babies need.

Neither Dr. Brabant nor Dr. Elovitz had any financial declarations.

*Correction, 2/7/2014: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the number of cervicovaginal samples.