User login

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM): Annual Meeting (The Pregnancy Meeting)

Vertical incision at C-section in morbidly obese women led to lower infection rates

NEW ORLEANS – Vertical incisions in morbidly obese women undergoing a primary cesarean delivery are associated with fewer wound complications, compared with transverse incisions.

The findings were "contrary to expectations," presenter Dr. Caroline C. Marrs told an audience at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The registry study of morbidly obese women who had had a primary C-section showed that those with a vertical incision were found to have higher rates of all adverse maternal outcomes, except for transfusions, but had lower incision-to-delivery times (9.2 plus or minus 5.5 vs. 11.1 plus or minus 6.1, P less than .001). "However, there was significant confounder bias, because after adjusting for significant baseline and clinical characteristics such as race, smoking status, and body mass index, vertical incisions were not associated with higher rates of composite maternal morbidity," said Dr. Marrs of the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston.

Using data collected between 1999 and 2002 for the cesarean registry of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network from 19 academic medical centers, Dr. Marrs and her colleagues identified 3,200 women with a body mass index of 40 kg/m2 at the time of their delivery by primary C-section whose incision type was known

The transverse skin incision cohort numbered 2,603 (81%), and the vertical incision group was 597 (19%).

An analysis of patient characteristics indicated the type of incision a woman had positively correlated with her race, smoking status, and insurance type, as well as whether the woman had gestational diabetes, chorioamnionitis, non–lower-segment hysterotomy, and an emergency C-section.

Logistical regression showed that vertical skin incisions were associated with parity (1.16, adjusted odds ratio 1.09-1.25); black race (1.24, AOR 1.03-1.51), maternal body mass index (1.06, AOR 1.04-1.08), low transverse hysterotomy (4.46, AOR 3.21-6.20), and nonemergent cesarean delivery (0.49, AOR 0.39-0.62).

A univariate analysis of composite wound complications such as seroma or hematoma indicated that vertical wounds were more associated with higher complication rates (4.2% of the vertical group vs. 1.7% of the transverse group, P less than .001).

Multivariate progression analysis indicated that the adjusted odds ratio for a vertical incision being a risk factor for wound complications was 0.32 (0.17-62). Other risk factors noted were: nonwhite race (0.48, AOR 0.25 to 0.94), maternal BMI (1.05, AOR 1.00 to 1.09), and ASA score (2.10, AOR 1.21-3.65).

"We suspect selection bias played a role," said Dr. Marrs. "Given the differences in baseline clinical characteristics of women who had vertical incisions, surgeons may have chosen this route based on selected factors such as BMI or need for emergency delivery."

Dr. Marrs did not have any relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Vertical incisions in morbidly obese women undergoing a primary cesarean delivery are associated with fewer wound complications, compared with transverse incisions.

The findings were "contrary to expectations," presenter Dr. Caroline C. Marrs told an audience at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The registry study of morbidly obese women who had had a primary C-section showed that those with a vertical incision were found to have higher rates of all adverse maternal outcomes, except for transfusions, but had lower incision-to-delivery times (9.2 plus or minus 5.5 vs. 11.1 plus or minus 6.1, P less than .001). "However, there was significant confounder bias, because after adjusting for significant baseline and clinical characteristics such as race, smoking status, and body mass index, vertical incisions were not associated with higher rates of composite maternal morbidity," said Dr. Marrs of the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston.

Using data collected between 1999 and 2002 for the cesarean registry of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network from 19 academic medical centers, Dr. Marrs and her colleagues identified 3,200 women with a body mass index of 40 kg/m2 at the time of their delivery by primary C-section whose incision type was known

The transverse skin incision cohort numbered 2,603 (81%), and the vertical incision group was 597 (19%).

An analysis of patient characteristics indicated the type of incision a woman had positively correlated with her race, smoking status, and insurance type, as well as whether the woman had gestational diabetes, chorioamnionitis, non–lower-segment hysterotomy, and an emergency C-section.

Logistical regression showed that vertical skin incisions were associated with parity (1.16, adjusted odds ratio 1.09-1.25); black race (1.24, AOR 1.03-1.51), maternal body mass index (1.06, AOR 1.04-1.08), low transverse hysterotomy (4.46, AOR 3.21-6.20), and nonemergent cesarean delivery (0.49, AOR 0.39-0.62).

A univariate analysis of composite wound complications such as seroma or hematoma indicated that vertical wounds were more associated with higher complication rates (4.2% of the vertical group vs. 1.7% of the transverse group, P less than .001).

Multivariate progression analysis indicated that the adjusted odds ratio for a vertical incision being a risk factor for wound complications was 0.32 (0.17-62). Other risk factors noted were: nonwhite race (0.48, AOR 0.25 to 0.94), maternal BMI (1.05, AOR 1.00 to 1.09), and ASA score (2.10, AOR 1.21-3.65).

"We suspect selection bias played a role," said Dr. Marrs. "Given the differences in baseline clinical characteristics of women who had vertical incisions, surgeons may have chosen this route based on selected factors such as BMI or need for emergency delivery."

Dr. Marrs did not have any relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Vertical incisions in morbidly obese women undergoing a primary cesarean delivery are associated with fewer wound complications, compared with transverse incisions.

The findings were "contrary to expectations," presenter Dr. Caroline C. Marrs told an audience at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The registry study of morbidly obese women who had had a primary C-section showed that those with a vertical incision were found to have higher rates of all adverse maternal outcomes, except for transfusions, but had lower incision-to-delivery times (9.2 plus or minus 5.5 vs. 11.1 plus or minus 6.1, P less than .001). "However, there was significant confounder bias, because after adjusting for significant baseline and clinical characteristics such as race, smoking status, and body mass index, vertical incisions were not associated with higher rates of composite maternal morbidity," said Dr. Marrs of the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston.

Using data collected between 1999 and 2002 for the cesarean registry of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network from 19 academic medical centers, Dr. Marrs and her colleagues identified 3,200 women with a body mass index of 40 kg/m2 at the time of their delivery by primary C-section whose incision type was known

The transverse skin incision cohort numbered 2,603 (81%), and the vertical incision group was 597 (19%).

An analysis of patient characteristics indicated the type of incision a woman had positively correlated with her race, smoking status, and insurance type, as well as whether the woman had gestational diabetes, chorioamnionitis, non–lower-segment hysterotomy, and an emergency C-section.

Logistical regression showed that vertical skin incisions were associated with parity (1.16, adjusted odds ratio 1.09-1.25); black race (1.24, AOR 1.03-1.51), maternal body mass index (1.06, AOR 1.04-1.08), low transverse hysterotomy (4.46, AOR 3.21-6.20), and nonemergent cesarean delivery (0.49, AOR 0.39-0.62).

A univariate analysis of composite wound complications such as seroma or hematoma indicated that vertical wounds were more associated with higher complication rates (4.2% of the vertical group vs. 1.7% of the transverse group, P less than .001).

Multivariate progression analysis indicated that the adjusted odds ratio for a vertical incision being a risk factor for wound complications was 0.32 (0.17-62). Other risk factors noted were: nonwhite race (0.48, AOR 0.25 to 0.94), maternal BMI (1.05, AOR 1.00 to 1.09), and ASA score (2.10, AOR 1.21-3.65).

"We suspect selection bias played a role," said Dr. Marrs. "Given the differences in baseline clinical characteristics of women who had vertical incisions, surgeons may have chosen this route based on selected factors such as BMI or need for emergency delivery."

Dr. Marrs did not have any relevant disclosures.

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: Vertical incisions at primary C-section appear to be a better choice for morbidly obese women, at least in terms of infection rate.

Major finding: Vertical incisions are associated with lower wound complication rates compared with transverse incisions in morbidly obese pregnant women.

Data source: Registry cohort study with multivariate analysis of 3,200 morbidly obese women who underwent primary cesarean delivery: 2,603 with a transverse incision and 597 with a vertical one.

Disclosures: Dr. Marrs did not have any relevant disclosures.

Laboring women preferred epidural to patient-controlled remifentanil analgesia

NEW ORLEANS – Laboring women had better overall pain relief satisfaction from epidurals than from remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia, according to results presented at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Although Dr. Liv Freeman, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and her colleagues expected to find that the two pain relief methods would be equivalent, the results of their multisite, randomized controlled study instead showed a significantly higher pain appreciation (pain relief satisfaction) score in women who received epidural analgesia during delivery.

"This should be taken into account when pain relief is offered to women in labor," said Dr. Freeman, who noted that the study’s intention was to provide more definitive data about the two pain relief methods because previous studies were underpowered – with some data showing the two methods were comparable.

An advantage to using remifentanil, an opioid similar to pethidine, is that it is fast-acting, typically cycling within 3 minutes. This attribute allows the drug to be self-administered and lowers costs, said Dr. Freeman. There are maternal side effects, however, including respiratory depression, nausea and vomiting, and sedation.

Placental transfer also occurs with remifentanil, although "the drug is so short acting, it is cleared once the baby is born when discontinued in the second stage of labor," Dr. Freeman said.

As for the potential risks of using an epidural, Dr. Freeman said that although rare, epidural hematomas can occur, and that "about 1 in 100 women experience postspinal headache, and between 10% and 20% of mothers develop a fever during labor."

Before active labor began, 709 women were randomly assigned to the remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) group, and 705 were assigned to the epidural group. The maternal age was about 31 years in each group, and other demographic baseline data also were similar. Nearly one-third more of the remifentanil PCA group, 402 women in all, opted to use the pain medication during labor, and 296 assigned to the epidural group chose to use it.

All women across the cohorts were asked hourly to rate their pain relief on a visual analog scale.

The total time-weighted pain appreciation score for the remifentanil PCA group was 25.7, versus 36.8 in the epidural group (P = .001).

Although the analysis was based on intention to treat, Dr. Freeman noted that 53 of the women in the self-administered pain relief group requested epidurals while in labor. Three women converted from an epidural to the self-administered pain medication.

The epidurals were performed according to local procedures across the 15 Dutch sites where the trial was conducted. Remifentanil PCA was 30 mcg administered intravenously with a 3-minute lockout time. The women had the option of increasing their dose to 40 mcg or decreasing it to 20 mcg.

The duration of analgesia was notably shorter in the remifentanil PCA group than in the epidural group: 236 minutes (interquartile range, 128-376 minutes) vs. 309 minutes (IQR, 181-454 minutes).

There were 22 elective cesarean deliveries in the remifentanil group and 29 in the epidural group. Three women in the epidural cohort were lost to follow-up, and two withdrew their consent.

There were no significant differences in important maternal and fetal outcomes, said Dr. Freeman. Because the safety profiles of remifentanil and epidural analgesia are essentially the same, physicians should counsel women about the pros and cons of each, she said.

This study was funded by ZonMw, the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. Dr. Freeman did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Laboring women had better overall pain relief satisfaction from epidurals than from remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia, according to results presented at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Although Dr. Liv Freeman, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and her colleagues expected to find that the two pain relief methods would be equivalent, the results of their multisite, randomized controlled study instead showed a significantly higher pain appreciation (pain relief satisfaction) score in women who received epidural analgesia during delivery.

"This should be taken into account when pain relief is offered to women in labor," said Dr. Freeman, who noted that the study’s intention was to provide more definitive data about the two pain relief methods because previous studies were underpowered – with some data showing the two methods were comparable.

An advantage to using remifentanil, an opioid similar to pethidine, is that it is fast-acting, typically cycling within 3 minutes. This attribute allows the drug to be self-administered and lowers costs, said Dr. Freeman. There are maternal side effects, however, including respiratory depression, nausea and vomiting, and sedation.

Placental transfer also occurs with remifentanil, although "the drug is so short acting, it is cleared once the baby is born when discontinued in the second stage of labor," Dr. Freeman said.

As for the potential risks of using an epidural, Dr. Freeman said that although rare, epidural hematomas can occur, and that "about 1 in 100 women experience postspinal headache, and between 10% and 20% of mothers develop a fever during labor."

Before active labor began, 709 women were randomly assigned to the remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) group, and 705 were assigned to the epidural group. The maternal age was about 31 years in each group, and other demographic baseline data also were similar. Nearly one-third more of the remifentanil PCA group, 402 women in all, opted to use the pain medication during labor, and 296 assigned to the epidural group chose to use it.

All women across the cohorts were asked hourly to rate their pain relief on a visual analog scale.

The total time-weighted pain appreciation score for the remifentanil PCA group was 25.7, versus 36.8 in the epidural group (P = .001).

Although the analysis was based on intention to treat, Dr. Freeman noted that 53 of the women in the self-administered pain relief group requested epidurals while in labor. Three women converted from an epidural to the self-administered pain medication.

The epidurals were performed according to local procedures across the 15 Dutch sites where the trial was conducted. Remifentanil PCA was 30 mcg administered intravenously with a 3-minute lockout time. The women had the option of increasing their dose to 40 mcg or decreasing it to 20 mcg.

The duration of analgesia was notably shorter in the remifentanil PCA group than in the epidural group: 236 minutes (interquartile range, 128-376 minutes) vs. 309 minutes (IQR, 181-454 minutes).

There were 22 elective cesarean deliveries in the remifentanil group and 29 in the epidural group. Three women in the epidural cohort were lost to follow-up, and two withdrew their consent.

There were no significant differences in important maternal and fetal outcomes, said Dr. Freeman. Because the safety profiles of remifentanil and epidural analgesia are essentially the same, physicians should counsel women about the pros and cons of each, she said.

This study was funded by ZonMw, the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. Dr. Freeman did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Laboring women had better overall pain relief satisfaction from epidurals than from remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia, according to results presented at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Although Dr. Liv Freeman, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and her colleagues expected to find that the two pain relief methods would be equivalent, the results of their multisite, randomized controlled study instead showed a significantly higher pain appreciation (pain relief satisfaction) score in women who received epidural analgesia during delivery.

"This should be taken into account when pain relief is offered to women in labor," said Dr. Freeman, who noted that the study’s intention was to provide more definitive data about the two pain relief methods because previous studies were underpowered – with some data showing the two methods were comparable.

An advantage to using remifentanil, an opioid similar to pethidine, is that it is fast-acting, typically cycling within 3 minutes. This attribute allows the drug to be self-administered and lowers costs, said Dr. Freeman. There are maternal side effects, however, including respiratory depression, nausea and vomiting, and sedation.

Placental transfer also occurs with remifentanil, although "the drug is so short acting, it is cleared once the baby is born when discontinued in the second stage of labor," Dr. Freeman said.

As for the potential risks of using an epidural, Dr. Freeman said that although rare, epidural hematomas can occur, and that "about 1 in 100 women experience postspinal headache, and between 10% and 20% of mothers develop a fever during labor."

Before active labor began, 709 women were randomly assigned to the remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) group, and 705 were assigned to the epidural group. The maternal age was about 31 years in each group, and other demographic baseline data also were similar. Nearly one-third more of the remifentanil PCA group, 402 women in all, opted to use the pain medication during labor, and 296 assigned to the epidural group chose to use it.

All women across the cohorts were asked hourly to rate their pain relief on a visual analog scale.

The total time-weighted pain appreciation score for the remifentanil PCA group was 25.7, versus 36.8 in the epidural group (P = .001).

Although the analysis was based on intention to treat, Dr. Freeman noted that 53 of the women in the self-administered pain relief group requested epidurals while in labor. Three women converted from an epidural to the self-administered pain medication.

The epidurals were performed according to local procedures across the 15 Dutch sites where the trial was conducted. Remifentanil PCA was 30 mcg administered intravenously with a 3-minute lockout time. The women had the option of increasing their dose to 40 mcg or decreasing it to 20 mcg.

The duration of analgesia was notably shorter in the remifentanil PCA group than in the epidural group: 236 minutes (interquartile range, 128-376 minutes) vs. 309 minutes (IQR, 181-454 minutes).

There were 22 elective cesarean deliveries in the remifentanil group and 29 in the epidural group. Three women in the epidural cohort were lost to follow-up, and two withdrew their consent.

There were no significant differences in important maternal and fetal outcomes, said Dr. Freeman. Because the safety profiles of remifentanil and epidural analgesia are essentially the same, physicians should counsel women about the pros and cons of each, she said.

This study was funded by ZonMw, the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. Dr. Freeman did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Major finding: Time-weighted, overall satisfaction scores for women who received an epidural were 36.8, compared with 25.7 for women using remifentanil, a significant difference.

Data source: Multisite, randomized controlled equivalence trial of 705 women who were administered an epidural vs. 709 women using patient-controlled remifentanil.

Disclosures: This study was funded by ZonMw, the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. Dr. Freeman did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Obesity does not interfere with accuracy of noninvasive preterm birth monitoring

NEW ORLEANS – Maternal obesity does not lessen the predictive value of noninvasive uterine electromyography monitoring, according to a poster presentation at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

"We wanted to see if in this subset of pregnant women, the noninvasive method was as effective as in other pregnant women," said Dr. Miha Lucovnik, a perinatologist at the University Medical Center, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

"Uterine contractions, at term or preterm, are one of the most common reasons for visits to obstetrical triage, but determining which patient with contractions is in true labor and needs to be admitted is, however, difficult," said Dr. Lucovnik. "The inability to accurately diagnose preterm labor leads to missed opportunities to improve outcomes of premature neonates, and also to unnecessary costs and side effects of treatments in women who would not deliver preterm regardless of intervention."

One of the more common monitoring methods – tocodynamometry – measures length and frequency of contractions but is often ineffective at detecting these signals in women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 and above, he said.

Electromyography (EMG) is more effective at monitoring the progression of true labor, because it can detect "the changes in cell excitability and coupling necessary for effective contractions," said Dr. Lucovnik.

To detect uterine activity, electrodes are placed on the patient’s abdomen with vertical and horizontal axes parallel to the patient’s vertical and horizontal axes, respectively, and with center-to-center distances between adjacent electrodes set about 5.0-5.5 cm apart. The uterine EMG is then measured for 30 minutes.

For the study, Dr. Lucovnik and his colleagues reviewed the predictive values of uterine EMG for preterm delivery in 88 women divided into three cohorts: 20 with a BMI of 30 or greater; 64 with a BMI of 25-29.9; and 4 with a BMI of 18.5-24.9.

The investigators did not find any significant difference between the cohorts in the area under the curve prediction of preterm delivery within 7 days (AUC was 0.95 in the normal and overweight cohorts, and 1 in the obese group; P = .08).

Six patients with low uterine EMG scores delivered prematurely within 7 days from the EMG measurement. No significant differences in BMI were reported between this false negative group (range, 26.13 plus or minus 1.03) and the combined true positive and true negative preterm labor groups (range, 28.04 plus or minus 3.77; P = .32).

"We know that predictive values of currently used methods to diagnose preterm labor are even lower in women with high BMI," said Dr. Lucovnik. "Our study showed that the accuracy of uterine EMG monitoring and its predictive value for preterm delivery are not affected by obesity in pregnant patients."

Dr. Lucovnik reported that he did not have any relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Maternal obesity does not lessen the predictive value of noninvasive uterine electromyography monitoring, according to a poster presentation at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

"We wanted to see if in this subset of pregnant women, the noninvasive method was as effective as in other pregnant women," said Dr. Miha Lucovnik, a perinatologist at the University Medical Center, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

"Uterine contractions, at term or preterm, are one of the most common reasons for visits to obstetrical triage, but determining which patient with contractions is in true labor and needs to be admitted is, however, difficult," said Dr. Lucovnik. "The inability to accurately diagnose preterm labor leads to missed opportunities to improve outcomes of premature neonates, and also to unnecessary costs and side effects of treatments in women who would not deliver preterm regardless of intervention."

One of the more common monitoring methods – tocodynamometry – measures length and frequency of contractions but is often ineffective at detecting these signals in women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 and above, he said.

Electromyography (EMG) is more effective at monitoring the progression of true labor, because it can detect "the changes in cell excitability and coupling necessary for effective contractions," said Dr. Lucovnik.

To detect uterine activity, electrodes are placed on the patient’s abdomen with vertical and horizontal axes parallel to the patient’s vertical and horizontal axes, respectively, and with center-to-center distances between adjacent electrodes set about 5.0-5.5 cm apart. The uterine EMG is then measured for 30 minutes.

For the study, Dr. Lucovnik and his colleagues reviewed the predictive values of uterine EMG for preterm delivery in 88 women divided into three cohorts: 20 with a BMI of 30 or greater; 64 with a BMI of 25-29.9; and 4 with a BMI of 18.5-24.9.

The investigators did not find any significant difference between the cohorts in the area under the curve prediction of preterm delivery within 7 days (AUC was 0.95 in the normal and overweight cohorts, and 1 in the obese group; P = .08).

Six patients with low uterine EMG scores delivered prematurely within 7 days from the EMG measurement. No significant differences in BMI were reported between this false negative group (range, 26.13 plus or minus 1.03) and the combined true positive and true negative preterm labor groups (range, 28.04 plus or minus 3.77; P = .32).

"We know that predictive values of currently used methods to diagnose preterm labor are even lower in women with high BMI," said Dr. Lucovnik. "Our study showed that the accuracy of uterine EMG monitoring and its predictive value for preterm delivery are not affected by obesity in pregnant patients."

Dr. Lucovnik reported that he did not have any relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Maternal obesity does not lessen the predictive value of noninvasive uterine electromyography monitoring, according to a poster presentation at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

"We wanted to see if in this subset of pregnant women, the noninvasive method was as effective as in other pregnant women," said Dr. Miha Lucovnik, a perinatologist at the University Medical Center, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

"Uterine contractions, at term or preterm, are one of the most common reasons for visits to obstetrical triage, but determining which patient with contractions is in true labor and needs to be admitted is, however, difficult," said Dr. Lucovnik. "The inability to accurately diagnose preterm labor leads to missed opportunities to improve outcomes of premature neonates, and also to unnecessary costs and side effects of treatments in women who would not deliver preterm regardless of intervention."

One of the more common monitoring methods – tocodynamometry – measures length and frequency of contractions but is often ineffective at detecting these signals in women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 and above, he said.

Electromyography (EMG) is more effective at monitoring the progression of true labor, because it can detect "the changes in cell excitability and coupling necessary for effective contractions," said Dr. Lucovnik.

To detect uterine activity, electrodes are placed on the patient’s abdomen with vertical and horizontal axes parallel to the patient’s vertical and horizontal axes, respectively, and with center-to-center distances between adjacent electrodes set about 5.0-5.5 cm apart. The uterine EMG is then measured for 30 minutes.

For the study, Dr. Lucovnik and his colleagues reviewed the predictive values of uterine EMG for preterm delivery in 88 women divided into three cohorts: 20 with a BMI of 30 or greater; 64 with a BMI of 25-29.9; and 4 with a BMI of 18.5-24.9.

The investigators did not find any significant difference between the cohorts in the area under the curve prediction of preterm delivery within 7 days (AUC was 0.95 in the normal and overweight cohorts, and 1 in the obese group; P = .08).

Six patients with low uterine EMG scores delivered prematurely within 7 days from the EMG measurement. No significant differences in BMI were reported between this false negative group (range, 26.13 plus or minus 1.03) and the combined true positive and true negative preterm labor groups (range, 28.04 plus or minus 3.77; P = .32).

"We know that predictive values of currently used methods to diagnose preterm labor are even lower in women with high BMI," said Dr. Lucovnik. "Our study showed that the accuracy of uterine EMG monitoring and its predictive value for preterm delivery are not affected by obesity in pregnant patients."

Dr. Lucovnik reported that he did not have any relevant disclosures.

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING 2014

Major finding: No significant differences in BMI were found in the false negative group (range, 26.13 plus or minus 1.03) and the combined true positive and true negative preterm labor groups combined (range, 28.04 plus or minus 3.77) (P = .32).

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 88 women, including 20 women with BMI greater than 30 kg/m2, noninvasively monitored for preterm birth.

Disclosures: Dr. Lucovnik reported that he did not have any relevant disclosures.

Obesity a driving factor in stillbirth

NEW ORLEANS – Almost 20% of the stillbirths that occurred over an 8-year period appeared to be associated with obesity.

A database review of nearly 3 million births found that the risk of stillbirth increased along with body mass index and gestational age. For women with the highest BMI – 50 kg/m2 – the incidence of a stillbirth jumped from 1.8/1,000 pregnancies at 39 weeks to 3/1,000 at 40 weeks and to more than 5/1,000 by 41 weeks, Dr. Ruofan Yao reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

"There is a dose-response relationship where the greater the BMI, the higher the risk of stillbirth. Obesity is a major contributing risk for stillbirth, where 20% of all stillbirths happen to women who are obese, and 1 in 4 stillbirths after 37 weeks is associated with obesity," said Dr. Yao of Drexel University, Philadelphia. "This is significantly higher than the population-attributable risk for chronic hypertension or pregestational diabetes."

Dr. Yao used birth and death records from Texas and Washington to determine the associations between weight and stillbirth. The Texas cohort included data on about 2 million births that occurred from 2006 to 2011. The Washington cohort included data on about 1 million from 2003 to 2011. Of the nearly 3 million births analyzed, about 9,000 were stillbirths. Fetuses with severe congenital anomalies were excluded from the analysis, as were pregnancies with a gestational age of less than 20 weeks.

Overall, 51% of the mothers in the analysis were of normal weight. About a quarter were overweight. Class I obesity was present in 13%, class II in 6%, and class III in 3.5%. The remaining 0.5% had a BMI of 50 or higher.

Although the risk of stillbirth rose with BMI and gestational age, overweight women were at no significantly increased risk of stillbirth compared with normal-weight women.

Women in class I were about twice as likely to have a stillbirth at both 37-39 weeks and 40-42 weeks. For women in class II, the risk was about 2.5 times higher at 37-39 weeks and twice as high at 40-42 weeks. In class III, the risk of stillbirth was three times higher at both time points.

The risk was sharply elevated for women with a BMI of 50 or more. At 37-39 weeks, they had a threefold increased risk. That jumped to a ninefold increased risk by 40-42 weeks, Dr. Yao said.

A separate analysis quantified population-attributable risk (PAR) for obesity and stillbirth. For all obesity (30 or higher), the risk was almost 20% overall. The PAR was 24% for early-term pregnancies and 28% for late-term pregnancies.

"Furthermore, over 5% of stillbirths from 37-39 weeks were associated with the much smaller subset of women who are morbidly obese, and this number jumps to 8% from 40-42 weeks," he said.

"Our data pointed to 39 weeks as a pivotal point in the pregnancy where the risk of stillbirth increases at a dramatic pace for women with BMI more than 50," Dr. Yao said in an interview. "I believe it is reasonable to have a discussion with patients in this BMI group regarding their maternal and fetal risks for expectant management verses delivery at 39 weeks. Whether to extend this recommendation to other obese women is unclear until more studies can delineate the risks and benefits more clearly."

The pathophysiology behind the association of obesity and preterm birth isn’t yet clear, he added.

"It is known in endocrine and medicine literature that obesity increases the baseline inflammatory response, and this may lead to abnormal placental growth and the development of uteroplacental insufficiency," Dr. Yao said.

"Obesity is also commonly associated with sleep apnea, which often worsens in pregnancy and can lead to transient hypoxic state, hindering normal fetal growth, and increase the risk of preeclampsia. Obesity also leads to glucose intolerance and increased serum lipid and triglyceride levels, leading to accelerated fetal growth velocity, and may contribute to the development of uteroplacental insufficiency. Additionally, the dietary habits of many obese women tend to exacerbate that problem."

Dr. Yao reported that he had no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Almost 20% of the stillbirths that occurred over an 8-year period appeared to be associated with obesity.

A database review of nearly 3 million births found that the risk of stillbirth increased along with body mass index and gestational age. For women with the highest BMI – 50 kg/m2 – the incidence of a stillbirth jumped from 1.8/1,000 pregnancies at 39 weeks to 3/1,000 at 40 weeks and to more than 5/1,000 by 41 weeks, Dr. Ruofan Yao reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

"There is a dose-response relationship where the greater the BMI, the higher the risk of stillbirth. Obesity is a major contributing risk for stillbirth, where 20% of all stillbirths happen to women who are obese, and 1 in 4 stillbirths after 37 weeks is associated with obesity," said Dr. Yao of Drexel University, Philadelphia. "This is significantly higher than the population-attributable risk for chronic hypertension or pregestational diabetes."

Dr. Yao used birth and death records from Texas and Washington to determine the associations between weight and stillbirth. The Texas cohort included data on about 2 million births that occurred from 2006 to 2011. The Washington cohort included data on about 1 million from 2003 to 2011. Of the nearly 3 million births analyzed, about 9,000 were stillbirths. Fetuses with severe congenital anomalies were excluded from the analysis, as were pregnancies with a gestational age of less than 20 weeks.

Overall, 51% of the mothers in the analysis were of normal weight. About a quarter were overweight. Class I obesity was present in 13%, class II in 6%, and class III in 3.5%. The remaining 0.5% had a BMI of 50 or higher.

Although the risk of stillbirth rose with BMI and gestational age, overweight women were at no significantly increased risk of stillbirth compared with normal-weight women.

Women in class I were about twice as likely to have a stillbirth at both 37-39 weeks and 40-42 weeks. For women in class II, the risk was about 2.5 times higher at 37-39 weeks and twice as high at 40-42 weeks. In class III, the risk of stillbirth was three times higher at both time points.

The risk was sharply elevated for women with a BMI of 50 or more. At 37-39 weeks, they had a threefold increased risk. That jumped to a ninefold increased risk by 40-42 weeks, Dr. Yao said.

A separate analysis quantified population-attributable risk (PAR) for obesity and stillbirth. For all obesity (30 or higher), the risk was almost 20% overall. The PAR was 24% for early-term pregnancies and 28% for late-term pregnancies.

"Furthermore, over 5% of stillbirths from 37-39 weeks were associated with the much smaller subset of women who are morbidly obese, and this number jumps to 8% from 40-42 weeks," he said.

"Our data pointed to 39 weeks as a pivotal point in the pregnancy where the risk of stillbirth increases at a dramatic pace for women with BMI more than 50," Dr. Yao said in an interview. "I believe it is reasonable to have a discussion with patients in this BMI group regarding their maternal and fetal risks for expectant management verses delivery at 39 weeks. Whether to extend this recommendation to other obese women is unclear until more studies can delineate the risks and benefits more clearly."

The pathophysiology behind the association of obesity and preterm birth isn’t yet clear, he added.

"It is known in endocrine and medicine literature that obesity increases the baseline inflammatory response, and this may lead to abnormal placental growth and the development of uteroplacental insufficiency," Dr. Yao said.

"Obesity is also commonly associated with sleep apnea, which often worsens in pregnancy and can lead to transient hypoxic state, hindering normal fetal growth, and increase the risk of preeclampsia. Obesity also leads to glucose intolerance and increased serum lipid and triglyceride levels, leading to accelerated fetal growth velocity, and may contribute to the development of uteroplacental insufficiency. Additionally, the dietary habits of many obese women tend to exacerbate that problem."

Dr. Yao reported that he had no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Almost 20% of the stillbirths that occurred over an 8-year period appeared to be associated with obesity.

A database review of nearly 3 million births found that the risk of stillbirth increased along with body mass index and gestational age. For women with the highest BMI – 50 kg/m2 – the incidence of a stillbirth jumped from 1.8/1,000 pregnancies at 39 weeks to 3/1,000 at 40 weeks and to more than 5/1,000 by 41 weeks, Dr. Ruofan Yao reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

"There is a dose-response relationship where the greater the BMI, the higher the risk of stillbirth. Obesity is a major contributing risk for stillbirth, where 20% of all stillbirths happen to women who are obese, and 1 in 4 stillbirths after 37 weeks is associated with obesity," said Dr. Yao of Drexel University, Philadelphia. "This is significantly higher than the population-attributable risk for chronic hypertension or pregestational diabetes."

Dr. Yao used birth and death records from Texas and Washington to determine the associations between weight and stillbirth. The Texas cohort included data on about 2 million births that occurred from 2006 to 2011. The Washington cohort included data on about 1 million from 2003 to 2011. Of the nearly 3 million births analyzed, about 9,000 were stillbirths. Fetuses with severe congenital anomalies were excluded from the analysis, as were pregnancies with a gestational age of less than 20 weeks.

Overall, 51% of the mothers in the analysis were of normal weight. About a quarter were overweight. Class I obesity was present in 13%, class II in 6%, and class III in 3.5%. The remaining 0.5% had a BMI of 50 or higher.

Although the risk of stillbirth rose with BMI and gestational age, overweight women were at no significantly increased risk of stillbirth compared with normal-weight women.

Women in class I were about twice as likely to have a stillbirth at both 37-39 weeks and 40-42 weeks. For women in class II, the risk was about 2.5 times higher at 37-39 weeks and twice as high at 40-42 weeks. In class III, the risk of stillbirth was three times higher at both time points.

The risk was sharply elevated for women with a BMI of 50 or more. At 37-39 weeks, they had a threefold increased risk. That jumped to a ninefold increased risk by 40-42 weeks, Dr. Yao said.

A separate analysis quantified population-attributable risk (PAR) for obesity and stillbirth. For all obesity (30 or higher), the risk was almost 20% overall. The PAR was 24% for early-term pregnancies and 28% for late-term pregnancies.

"Furthermore, over 5% of stillbirths from 37-39 weeks were associated with the much smaller subset of women who are morbidly obese, and this number jumps to 8% from 40-42 weeks," he said.

"Our data pointed to 39 weeks as a pivotal point in the pregnancy where the risk of stillbirth increases at a dramatic pace for women with BMI more than 50," Dr. Yao said in an interview. "I believe it is reasonable to have a discussion with patients in this BMI group regarding their maternal and fetal risks for expectant management verses delivery at 39 weeks. Whether to extend this recommendation to other obese women is unclear until more studies can delineate the risks and benefits more clearly."

The pathophysiology behind the association of obesity and preterm birth isn’t yet clear, he added.

"It is known in endocrine and medicine literature that obesity increases the baseline inflammatory response, and this may lead to abnormal placental growth and the development of uteroplacental insufficiency," Dr. Yao said.

"Obesity is also commonly associated with sleep apnea, which often worsens in pregnancy and can lead to transient hypoxic state, hindering normal fetal growth, and increase the risk of preeclampsia. Obesity also leads to glucose intolerance and increased serum lipid and triglyceride levels, leading to accelerated fetal growth velocity, and may contribute to the development of uteroplacental insufficiency. Additionally, the dietary habits of many obese women tend to exacerbate that problem."

Dr. Yao reported that he had no financial disclosures.

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Major finding: Nearly 20% of stillbirths that occurred over an 8-year period were associated with obesity.

Data source: Population-based data with information on almost 3 million births.

Disclosures: Dr. Yao reported that he had no financial disclosures.

Delivery of identical twins near 33 weeks balances outcomes

NEW ORLEANS – The optimal time to deliver monoamniotic twins is right around 33 weeks, when the risks of intrauterine death and neonatal complications are both very low.

"Monoamniotic twin pregnancies are at extremely high risk of intrauterine death before 28 weeks’ gestation," Dr. Tim Van Mieghem said at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine. "But with regular fetal monitoring and ultrasound, that risk is extremely low from 28 to 32 weeks."

At the same time, the risk of neonatal complications decreases as the pregnancy advances. The fulcrum that balances both optimal outcomes is 33 weeks, 4 days.

To determine this, Dr. Van Mieghem looked at a retrospective cohort of monoamniotic twin pregnancies followed during 2003-2013 in Canada and Europe. The group comprised 193 pregnancies (386 fetuses); the investigators excluded conjoined twins and cases of twin reversed arterial perfusion. The rate of twin-twin transfusion syndrome was low (3%).

The rate of fetal anomalies was quite high (53; 14%), said Dr. Van Mieghem of the University Hospital of Leuven, Belgium. Twelve of the pregnancies were terminated. There were 28 double intrauterine deaths and 14 single intrauterine deaths. Most of these were caused by cord events; seven were iatrogenic.

Most of the fetuses (76%) were born alive at an average of 32 weeks’ gestation. Most of the mothers received corticosteroids (91%), and most deliveries were by cesarean section (97%). The mean birth weight was 1,749 g. The neonatal death rate was 5.7%.

The most common neonatal complications were respiratory; 80% of the infants needed respiratory support and 40% had respiratory distress syndrome. The rate of nonrespiratory complications was about 15%. Sepsis occurred in about 10%. The remainder of the complications were necrotizing enterocolitis, intraventricular hemorrhage, and periventricular leukomalacia.

The risk of intrauterine death decreased as the pregnancy advanced. At 24 weeks, it was about 5%, but by 28 weeks had dropped to a low of 1.4%. Thereafter, the risk began to rise, reaching about 7% by week 35.

The risk of neonatal complications also decreased as the pregnancy advanced. It reached its nadir of about 2% at around 28 weeks and stayed low until about 33 weeks, when it began to rise. By 34 weeks it was near 7%, but dropped to close to 0 shortly after 35 weeks.

"The risk curves intersected at 32 weeks, 4 days," Dr. Van Mieghem said. "Based on these curves, it seems prudent to deliver these fetuses at 32 weeks, when the risk of both intrauterine demise and neonatal complications is about 3%."

He added that there were no significant differences in neonatal outcomes between pregnancies that were monitored on an inpatient and outpatient basis. The gestational age at delivery was about a week earlier in inpatients (32 vs. 33 weeks.) The rate of fetal distress was slightly higher among inpatients (21% vs. 23%). The outpatient pregnancies resulted in larger infants (mean 1,827 g vs. 1,776 g).

The rate of nonrespiratory neonatal complications was about 9% in each group. However, significantly more infants in the inpatient group needed ventilation (76% vs. 63%). They were also on ventilation about a day longer (5 days vs. 4 days).

There were one single and two double intrauterine deaths in the outpatient group, and one single intrauterine death in the inpatient group. But because all of the outpatient deaths occurred before 28 weeks, Dr. Van Mieghem said they probably could not have been averted by inpatient management.

"If you were looking at the rate of truly preventable deaths, it likely would have been 0 in both groups," he said.

Dr. Van Mieghem had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

NEW ORLEANS – The optimal time to deliver monoamniotic twins is right around 33 weeks, when the risks of intrauterine death and neonatal complications are both very low.

"Monoamniotic twin pregnancies are at extremely high risk of intrauterine death before 28 weeks’ gestation," Dr. Tim Van Mieghem said at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine. "But with regular fetal monitoring and ultrasound, that risk is extremely low from 28 to 32 weeks."

At the same time, the risk of neonatal complications decreases as the pregnancy advances. The fulcrum that balances both optimal outcomes is 33 weeks, 4 days.

To determine this, Dr. Van Mieghem looked at a retrospective cohort of monoamniotic twin pregnancies followed during 2003-2013 in Canada and Europe. The group comprised 193 pregnancies (386 fetuses); the investigators excluded conjoined twins and cases of twin reversed arterial perfusion. The rate of twin-twin transfusion syndrome was low (3%).

The rate of fetal anomalies was quite high (53; 14%), said Dr. Van Mieghem of the University Hospital of Leuven, Belgium. Twelve of the pregnancies were terminated. There were 28 double intrauterine deaths and 14 single intrauterine deaths. Most of these were caused by cord events; seven were iatrogenic.

Most of the fetuses (76%) were born alive at an average of 32 weeks’ gestation. Most of the mothers received corticosteroids (91%), and most deliveries were by cesarean section (97%). The mean birth weight was 1,749 g. The neonatal death rate was 5.7%.

The most common neonatal complications were respiratory; 80% of the infants needed respiratory support and 40% had respiratory distress syndrome. The rate of nonrespiratory complications was about 15%. Sepsis occurred in about 10%. The remainder of the complications were necrotizing enterocolitis, intraventricular hemorrhage, and periventricular leukomalacia.

The risk of intrauterine death decreased as the pregnancy advanced. At 24 weeks, it was about 5%, but by 28 weeks had dropped to a low of 1.4%. Thereafter, the risk began to rise, reaching about 7% by week 35.

The risk of neonatal complications also decreased as the pregnancy advanced. It reached its nadir of about 2% at around 28 weeks and stayed low until about 33 weeks, when it began to rise. By 34 weeks it was near 7%, but dropped to close to 0 shortly after 35 weeks.

"The risk curves intersected at 32 weeks, 4 days," Dr. Van Mieghem said. "Based on these curves, it seems prudent to deliver these fetuses at 32 weeks, when the risk of both intrauterine demise and neonatal complications is about 3%."

He added that there were no significant differences in neonatal outcomes between pregnancies that were monitored on an inpatient and outpatient basis. The gestational age at delivery was about a week earlier in inpatients (32 vs. 33 weeks.) The rate of fetal distress was slightly higher among inpatients (21% vs. 23%). The outpatient pregnancies resulted in larger infants (mean 1,827 g vs. 1,776 g).

The rate of nonrespiratory neonatal complications was about 9% in each group. However, significantly more infants in the inpatient group needed ventilation (76% vs. 63%). They were also on ventilation about a day longer (5 days vs. 4 days).

There were one single and two double intrauterine deaths in the outpatient group, and one single intrauterine death in the inpatient group. But because all of the outpatient deaths occurred before 28 weeks, Dr. Van Mieghem said they probably could not have been averted by inpatient management.

"If you were looking at the rate of truly preventable deaths, it likely would have been 0 in both groups," he said.

Dr. Van Mieghem had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

NEW ORLEANS – The optimal time to deliver monoamniotic twins is right around 33 weeks, when the risks of intrauterine death and neonatal complications are both very low.

"Monoamniotic twin pregnancies are at extremely high risk of intrauterine death before 28 weeks’ gestation," Dr. Tim Van Mieghem said at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine. "But with regular fetal monitoring and ultrasound, that risk is extremely low from 28 to 32 weeks."

At the same time, the risk of neonatal complications decreases as the pregnancy advances. The fulcrum that balances both optimal outcomes is 33 weeks, 4 days.

To determine this, Dr. Van Mieghem looked at a retrospective cohort of monoamniotic twin pregnancies followed during 2003-2013 in Canada and Europe. The group comprised 193 pregnancies (386 fetuses); the investigators excluded conjoined twins and cases of twin reversed arterial perfusion. The rate of twin-twin transfusion syndrome was low (3%).

The rate of fetal anomalies was quite high (53; 14%), said Dr. Van Mieghem of the University Hospital of Leuven, Belgium. Twelve of the pregnancies were terminated. There were 28 double intrauterine deaths and 14 single intrauterine deaths. Most of these were caused by cord events; seven were iatrogenic.

Most of the fetuses (76%) were born alive at an average of 32 weeks’ gestation. Most of the mothers received corticosteroids (91%), and most deliveries were by cesarean section (97%). The mean birth weight was 1,749 g. The neonatal death rate was 5.7%.

The most common neonatal complications were respiratory; 80% of the infants needed respiratory support and 40% had respiratory distress syndrome. The rate of nonrespiratory complications was about 15%. Sepsis occurred in about 10%. The remainder of the complications were necrotizing enterocolitis, intraventricular hemorrhage, and periventricular leukomalacia.

The risk of intrauterine death decreased as the pregnancy advanced. At 24 weeks, it was about 5%, but by 28 weeks had dropped to a low of 1.4%. Thereafter, the risk began to rise, reaching about 7% by week 35.

The risk of neonatal complications also decreased as the pregnancy advanced. It reached its nadir of about 2% at around 28 weeks and stayed low until about 33 weeks, when it began to rise. By 34 weeks it was near 7%, but dropped to close to 0 shortly after 35 weeks.

"The risk curves intersected at 32 weeks, 4 days," Dr. Van Mieghem said. "Based on these curves, it seems prudent to deliver these fetuses at 32 weeks, when the risk of both intrauterine demise and neonatal complications is about 3%."

He added that there were no significant differences in neonatal outcomes between pregnancies that were monitored on an inpatient and outpatient basis. The gestational age at delivery was about a week earlier in inpatients (32 vs. 33 weeks.) The rate of fetal distress was slightly higher among inpatients (21% vs. 23%). The outpatient pregnancies resulted in larger infants (mean 1,827 g vs. 1,776 g).

The rate of nonrespiratory neonatal complications was about 9% in each group. However, significantly more infants in the inpatient group needed ventilation (76% vs. 63%). They were also on ventilation about a day longer (5 days vs. 4 days).

There were one single and two double intrauterine deaths in the outpatient group, and one single intrauterine death in the inpatient group. But because all of the outpatient deaths occurred before 28 weeks, Dr. Van Mieghem said they probably could not have been averted by inpatient management.

"If you were looking at the rate of truly preventable deaths, it likely would have been 0 in both groups," he said.

Dr. Van Mieghem had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Major finding: For monoamniotic twins, the risks of intrauterine death and neonatal complications are both about 3% at 33 weeks’ gestation, making that the best time to deliver these babies.

Data source: The retrospective study comprised 193 monoamniotic twin pregnancies during 2003-2013.

Disclosures: Dr. Tim Van Mieghem had no financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Is noninvasive prenatal testing right for your patient?

NEW ORLEANS – Noninvasive prenatal testing widens the options available to patients and their physicians seeking more information than what is provided by integrated screens, but who are perhaps not willing to take the risks of invasive diagnostic testing. Dr. Mary Norton, vice chair of clinical and translational genetics and a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, San Francisco, gives front-line obstetricians pragmatic advice for how to counsel their patients about the use of this emerging screening technology in this video interview.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEW ORLEANS – Noninvasive prenatal testing widens the options available to patients and their physicians seeking more information than what is provided by integrated screens, but who are perhaps not willing to take the risks of invasive diagnostic testing. Dr. Mary Norton, vice chair of clinical and translational genetics and a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, San Francisco, gives front-line obstetricians pragmatic advice for how to counsel their patients about the use of this emerging screening technology in this video interview.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEW ORLEANS – Noninvasive prenatal testing widens the options available to patients and their physicians seeking more information than what is provided by integrated screens, but who are perhaps not willing to take the risks of invasive diagnostic testing. Dr. Mary Norton, vice chair of clinical and translational genetics and a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, San Francisco, gives front-line obstetricians pragmatic advice for how to counsel their patients about the use of this emerging screening technology in this video interview.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE SMFM ANNUAL MEETING

Study finds increased infant mortality for home births

NEW ORLEANS – Midwife-attended home births appear to have a higher mortality rate than midwife-attended hospital births, a new national database study suggests.

But for both physicians and families, the findings lie at the center of a tangled knot of statistics, philosophy, fear, and determination.

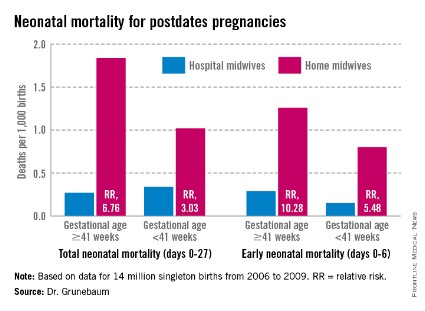

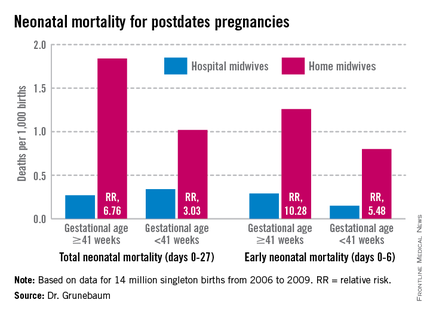

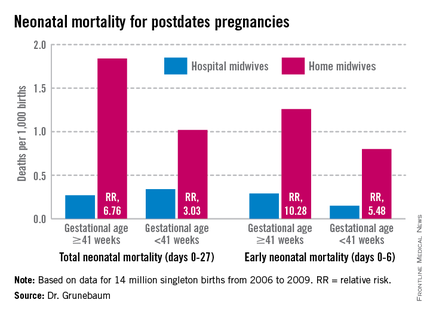

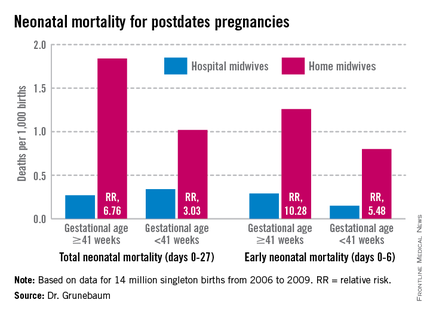

According to a new study of national birth and death statistics, total neonatal mortality in midwife-assisted hospital births was 0.32/1,000. For a midwife-attended home birth, that number was 1.26/1,000 – almost a fourfold increase in relative risk, Dr. Amos Grunebaum said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

His study drew its data from linked birth and death records available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) database. The study looked at 14 million births from 2006 to 2009. Only healthy singleton infants of normal birth weight and vertex presentation were included; gestation was 38-42 weeks.

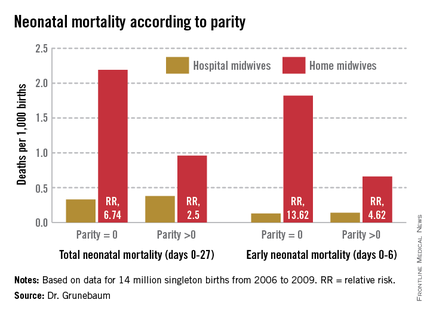

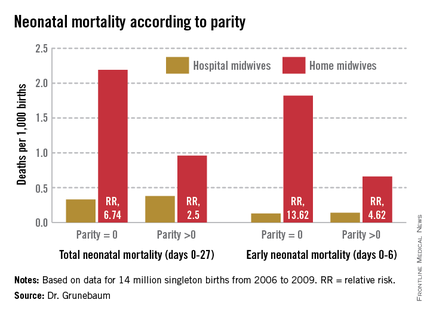

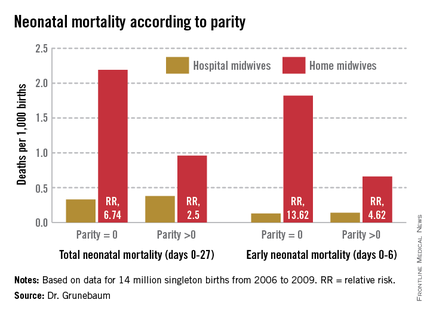

The figures for nulliparous women giving birth at home were even more striking, said Dr. Grunebaum, director of obstetrics at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. Total neonatal mortality (deaths from day 0 to 27) was 2.19/1,000 for home-birthed infants, compared with 0.38/1,000 for hospital-born infants (relative risk, 6.74). The rates of early neonatal mortality (deaths from day 0 to 6) were 1.82/1,000 vs. 0.13/1,000, respectively (RR, 13.6).

"When we calculate the excess total neonatal deaths associated with home birth, we arrive at 9/10,000," he said during an interview. "If the trend of increasing home birth holds over the next few years, in 2016 we could have 32 excess neonatal deaths per year – a whole school class of children."

"It’s possible these risks are even higher," he added, because any babies born in the hospital after an emergency transfer from home are counted as hospital births.

It’s tough to parse out the details in his analysis, however. Because lay midwives would never have had hospital privileges, the in-hospital midwife group was likely composed entirely of certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), whose specialized training makes them highly skilled birth attendants. But the midwives who attended home births were a heterogenous group. In addition to CNMs, the analysis included anyone else who would register as "midwife" on a birth certificate – a group that represents an extremely varied range of skill.

These attendants could be could have been CNMs, certified midwives, certified professional midwives, licensed midwives, or lay midwives. CNMs must have a bachelor’s degree as a registered nurse and then graduate from an accredited school of nurse-midwifery. A certified midwife is a graduate of the same school of midwifery program, but can hold a degree in a field other than nursing. The American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM) regulates these providers.

No college degree is required for a certified professional midwife. They can obtain licensure based on an apprenticeship portfolio or from other schools of midwifery. The Midwives Alliance of North America and the National Association of Certified Professional Midwives regulate this group. Lay midwives are allowed to practice in some states, but there is no regulatory board, and no licensure or educational requirements.

In all probability, very few CNMs attended the home births in Dr. Grunebaum’s study, according to Jesse Bushman, ACNM’s director of advocacy and government affairs. The college’s own data indicate that 90% of deliveries performed by members are in hospitals. Only 30% of home births recorded in the CDC data were performed by CNMs, he said.

"That is one issue we have with Dr. Grunebaum’s results," Mr. Bushman* said in an interview. "There are many people who could call themselves a midwife who may not have the training or competencies that CNMs do. To lump them together is quite problematic."

In an interview, Dr. Grunebaum said that he had parsed out the mortality results by specific provider group. However, he would not release those numbers, saying it could jeopardize his study’s peer-reviewed publication. "I will tell you that CNMs at home did much, much worse than CNMs in the hospital, and that other midwives at home were not far behind."

Birth outcomes data just released by the Midwives Alliance of North America (MANA) align with Dr. Grunebaum’s numbers (J. Midwifery Womens Health 2014 Jan. 30 [doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12172]). But the interpretation – if not the numbers – lies in the eye of the beholder. Dr. Grunebaum said the study illustrates the danger of home birth. MANA hailed it as proof of home birth’s safety.

"The results of this study ... confirm the safety and overwhelmingly positive health benefits for low-risk mothers and babies who choose to birth at home with a midwife," the group noted on its website. "At every step of the way, midwives are providing excellent care. This study enables families, providers, and policy makers to have a transparent look at the risks and benefits of planned home birth, as well as the health benefits of normal physiologic birth."

The study was a voluntary survey that examined data from almost 17,000 home births. The voluntary nature troubles Dr. Grunebaum, who pointed out that midwives with poor outcomes probably would not have submitted data.

There was an 11% hospital transfer rate in the cohort from the midwives study. There were 43 fetal deaths in the intrapartum, early, and late neonatal periods; 8 of these were from lethal congenital defects. The remaining deaths translated to a total neonatal mortality rate of 1.3/1,000.

Twenty-two died during labor, but before birth. For 13, the causes were known: placental abruption (2), intrauterine infection (2), cord accidents (3), complications of maternal gestational diabetes (2), meconium aspiration (1), shoulder dystocia (1), complications of preeclampsia (1), and liver rupture and hypoxia (1).

Seven babies died during the first 6 days of life. The causes were secondary to cord accidents (2, one with shoulder dystocia), and hypoxia or ischemia of unknown origin (5).

Six infants died in the late neonatal period. Two deaths were secondary to cord accidents, and four were from unknown causes.

Of 222 breech births, three infants died (13/1,000). Of 3,773 births to primiparous women, 11 infants died (2.9/1,000). Of 1,052 attempted vaginal births, 3 infants died (2.85/1,000)

"These numbers are horrible," Dr. Grunebaum said. "There is no longer room for the argument from home birth supporters that while the risk may be increased, it’s still very low in terms of absolute risk."

"This view has even been expressed by our own specialists," he added, referring to an American Academy of Pediatrics position paper on planned home birth (Pediatrics 2013;131:1016-20). While maintaining that birth is safest in a hospital or birthing center, the paper acknowledges that the two- or threefold overall increase in mortality associated with home birth is low – generally translating to about 1 in 1,000 newborns.

"That minimizes the extra risk involved in home birth," Dr. Grunebaum said. "We should have no acceptance for any increase in death or injury in exchange for parental convenience or for fewer interventions. We need to disclose these increased risks to mothers, and perform direct counseling against home birth."

His study fans a long-simmering debate about the best places to birth. Proponents of both philosophies want the same primary outcome: healthy mothers and infants. The debate? How to best get there.

Midwife-assisted home birth has grown exponentially over the past decade. According to CDC data, there were about 16,000 in 2007; by 2012, it was about 23,500. The rise is mostly seen in a very specific demographic – well-educated, financially secure white women with at least one other child who was, most frequently, born in a hospital.

Dr. Grunebaum attributed the rise to some women’s desire to avoid what they perceive as intrusive labor and birth management. With this thought, at least, others do agree.

Eugene DeClercq, Ph.D., a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and of public health at Boston University, has worked on three national surveys that poll new mothers about their experiences with pregnancy, labor and delivery, and postpartum life.

Childbirth Connection (childbirthconnection.org) conducted the Listening to Mothers surveys in 2002, 2006, and 2012. The survey reports are intended to serve as policy resources for improving the childbearing experience for women and their families.

"One of the real questions we need to look at is, what’s going on in hospitals that makes women consider giving birth outside the hospital," Dr. DeClercq said in an interview. "What has come through in our interviews is that many women are quite fine with the ways things go in a hospital. They are for any intervention that they think will make a safer birth. But many women are not. They report feeling pressured to have interventions, and worried that one will lead to another and another, in a cascade that can eventually end up in a cesarean section."

This is a legitimate concern in the United States, he said – a country in which the cesarean rate hovers around 30%, and ranges from 7% to 70% across hospitals. "If you lived ... where there was a 70% rate of cesarean – 70%! – might you be thinking about some way to avoid that?"

In the Listening to Mothers II survey, women were asked a series of questions about their experiences with labor and delivery. The results of the survey revealed that 47% of first-time mothers were induced. "Of those having an induction, 78% had an epidural, and of those mothers who had both an attempted induction and an epidural, the unplanned cesarean rate was 31%," the report noted. "Those who experienced either labor induction or an epidural, but not both, had cesarean rates of 19% to 20%. For those first-time mothers who experienced neither attempted induction nor an epidural, the unplanned cesarean rate was 5%."

Like it or not, he said, some women will go to almost any length to avoid interventions they fear may harm them and their babies.

The Listening to Mothers survey found that a quarter of women who had given birth in a hospital would consider a home birth. Most women in the survey (2/3) said a woman should be able to have a home birth if she wanted, and 11% said they would definitely want a home birth.

"If you look at the profile of home-birthers, it’s not like they are some crazy fringe group," Dr. DeClercq said. "These are very well-educated women, 75% of whom have already had a hospital birth. They are researching and weighing the pros and cons. They’re not just making some random decision."

His data also suggest that women who transfer to a hospital from a home birth fear judgment and even recrimination. "The consequences of that can be a delay in transfer when it’s necessary, and can lead to problems," even poor infant outcomes.

On this point at least, the two sides find common ground.

"Most of us will never attend a home birth," Dr. Grunebaum said. "But we will encounter patients asking us about home births and seeking hospital transfer for successful or complicated home births, and babies transferred after a home birth. And for these we need to provide compassionate, nonjudgmental care."

None of the sources interviewed for this story reported any financial disclosures.

*Correction, 3/4/2014: An earlier version of this story misstated Mr. Bushman's name.

NEW ORLEANS – Midwife-attended home births appear to have a higher mortality rate than midwife-attended hospital births, a new national database study suggests.

But for both physicians and families, the findings lie at the center of a tangled knot of statistics, philosophy, fear, and determination.

According to a new study of national birth and death statistics, total neonatal mortality in midwife-assisted hospital births was 0.32/1,000. For a midwife-attended home birth, that number was 1.26/1,000 – almost a fourfold increase in relative risk, Dr. Amos Grunebaum said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

His study drew its data from linked birth and death records available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) database. The study looked at 14 million births from 2006 to 2009. Only healthy singleton infants of normal birth weight and vertex presentation were included; gestation was 38-42 weeks.

The figures for nulliparous women giving birth at home were even more striking, said Dr. Grunebaum, director of obstetrics at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. Total neonatal mortality (deaths from day 0 to 27) was 2.19/1,000 for home-birthed infants, compared with 0.38/1,000 for hospital-born infants (relative risk, 6.74). The rates of early neonatal mortality (deaths from day 0 to 6) were 1.82/1,000 vs. 0.13/1,000, respectively (RR, 13.6).

"When we calculate the excess total neonatal deaths associated with home birth, we arrive at 9/10,000," he said during an interview. "If the trend of increasing home birth holds over the next few years, in 2016 we could have 32 excess neonatal deaths per year – a whole school class of children."

"It’s possible these risks are even higher," he added, because any babies born in the hospital after an emergency transfer from home are counted as hospital births.

It’s tough to parse out the details in his analysis, however. Because lay midwives would never have had hospital privileges, the in-hospital midwife group was likely composed entirely of certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), whose specialized training makes them highly skilled birth attendants. But the midwives who attended home births were a heterogenous group. In addition to CNMs, the analysis included anyone else who would register as "midwife" on a birth certificate – a group that represents an extremely varied range of skill.

These attendants could be could have been CNMs, certified midwives, certified professional midwives, licensed midwives, or lay midwives. CNMs must have a bachelor’s degree as a registered nurse and then graduate from an accredited school of nurse-midwifery. A certified midwife is a graduate of the same school of midwifery program, but can hold a degree in a field other than nursing. The American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM) regulates these providers.

No college degree is required for a certified professional midwife. They can obtain licensure based on an apprenticeship portfolio or from other schools of midwifery. The Midwives Alliance of North America and the National Association of Certified Professional Midwives regulate this group. Lay midwives are allowed to practice in some states, but there is no regulatory board, and no licensure or educational requirements.

In all probability, very few CNMs attended the home births in Dr. Grunebaum’s study, according to Jesse Bushman, ACNM’s director of advocacy and government affairs. The college’s own data indicate that 90% of deliveries performed by members are in hospitals. Only 30% of home births recorded in the CDC data were performed by CNMs, he said.

"That is one issue we have with Dr. Grunebaum’s results," Mr. Bushman* said in an interview. "There are many people who could call themselves a midwife who may not have the training or competencies that CNMs do. To lump them together is quite problematic."

In an interview, Dr. Grunebaum said that he had parsed out the mortality results by specific provider group. However, he would not release those numbers, saying it could jeopardize his study’s peer-reviewed publication. "I will tell you that CNMs at home did much, much worse than CNMs in the hospital, and that other midwives at home were not far behind."

Birth outcomes data just released by the Midwives Alliance of North America (MANA) align with Dr. Grunebaum’s numbers (J. Midwifery Womens Health 2014 Jan. 30 [doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12172]). But the interpretation – if not the numbers – lies in the eye of the beholder. Dr. Grunebaum said the study illustrates the danger of home birth. MANA hailed it as proof of home birth’s safety.

"The results of this study ... confirm the safety and overwhelmingly positive health benefits for low-risk mothers and babies who choose to birth at home with a midwife," the group noted on its website. "At every step of the way, midwives are providing excellent care. This study enables families, providers, and policy makers to have a transparent look at the risks and benefits of planned home birth, as well as the health benefits of normal physiologic birth."

The study was a voluntary survey that examined data from almost 17,000 home births. The voluntary nature troubles Dr. Grunebaum, who pointed out that midwives with poor outcomes probably would not have submitted data.

There was an 11% hospital transfer rate in the cohort from the midwives study. There were 43 fetal deaths in the intrapartum, early, and late neonatal periods; 8 of these were from lethal congenital defects. The remaining deaths translated to a total neonatal mortality rate of 1.3/1,000.

Twenty-two died during labor, but before birth. For 13, the causes were known: placental abruption (2), intrauterine infection (2), cord accidents (3), complications of maternal gestational diabetes (2), meconium aspiration (1), shoulder dystocia (1), complications of preeclampsia (1), and liver rupture and hypoxia (1).

Seven babies died during the first 6 days of life. The causes were secondary to cord accidents (2, one with shoulder dystocia), and hypoxia or ischemia of unknown origin (5).

Six infants died in the late neonatal period. Two deaths were secondary to cord accidents, and four were from unknown causes.

Of 222 breech births, three infants died (13/1,000). Of 3,773 births to primiparous women, 11 infants died (2.9/1,000). Of 1,052 attempted vaginal births, 3 infants died (2.85/1,000)

"These numbers are horrible," Dr. Grunebaum said. "There is no longer room for the argument from home birth supporters that while the risk may be increased, it’s still very low in terms of absolute risk."

"This view has even been expressed by our own specialists," he added, referring to an American Academy of Pediatrics position paper on planned home birth (Pediatrics 2013;131:1016-20). While maintaining that birth is safest in a hospital or birthing center, the paper acknowledges that the two- or threefold overall increase in mortality associated with home birth is low – generally translating to about 1 in 1,000 newborns.

"That minimizes the extra risk involved in home birth," Dr. Grunebaum said. "We should have no acceptance for any increase in death or injury in exchange for parental convenience or for fewer interventions. We need to disclose these increased risks to mothers, and perform direct counseling against home birth."

His study fans a long-simmering debate about the best places to birth. Proponents of both philosophies want the same primary outcome: healthy mothers and infants. The debate? How to best get there.

Midwife-assisted home birth has grown exponentially over the past decade. According to CDC data, there were about 16,000 in 2007; by 2012, it was about 23,500. The rise is mostly seen in a very specific demographic – well-educated, financially secure white women with at least one other child who was, most frequently, born in a hospital.

Dr. Grunebaum attributed the rise to some women’s desire to avoid what they perceive as intrusive labor and birth management. With this thought, at least, others do agree.

Eugene DeClercq, Ph.D., a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and of public health at Boston University, has worked on three national surveys that poll new mothers about their experiences with pregnancy, labor and delivery, and postpartum life.

Childbirth Connection (childbirthconnection.org) conducted the Listening to Mothers surveys in 2002, 2006, and 2012. The survey reports are intended to serve as policy resources for improving the childbearing experience for women and their families.