User login

Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists (SOGH): Annual Clinical Meeting

Anticipate the many challenges of cesarean section in superobese

DENVER – In current practice, the majority of superobese pregnant women – those having a prepregnancy body mass index of 50 kg/m2 or more – will end up having a cesarean section. The inherent technical challenges make it crucial to have a plan in place before heading to the operating room.

"There’s a lot to think about: patient positioning, choice of incision, antibiotic prophylaxis, deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, wound care," Dr. Mark Alanis observed at the annual meeting of the Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists.

Also, it’s important to understand up front that one in three of these superobese patients will have a significant wound complication. Eighty-five percent of these are cellulitis or wound disruptions, mostly seromas, which will require packing. But one in seven of the wound complications are abscesses, and affected superobese patients require hospital readmission, said Dr. Alanis of the University of Colorado, Denver.

He presented lessons learned from his own retrospective study of 194 superobese patients who underwent cesarean section, plus several studies by other investigators. Among the highlights:

• Anesthesia evaluation. Bring the anesthesiologist in on the case early. Finding the landmarks for spinal anesthesia is tough in a superobese patient. Failed regional anesthesia is more common. In Dr. Alanis’ series, general anesthesia was required in 15% of patients – a far higher rate than in leaner women – so a careful preoperative airway assessment is essential.

• Patient positioning. Understand that positioning the superobese patient at a 20-degree tilt puts the midline far away from the surgeon, who’ll have to operate bending forward. "My back is killing me when I do these operations," the ob.gyn. said.

• Choice of incision. Dr. Alanis recommends the Pfannenstiel incision. This horizontal incision is faster than a vertical incision, the wound hurts less, healing is better, and the classic teaching that it poses an increased risk of infection in massively obese patients is a myth unsupported by data.

The key is to first mobilize the panniculus, moving it up off the suprapubic region, then securing it with a Montgomery strap tied off to the bedposts.

"It takes 5 minutes to secure the pannis. It’s the easiest thing in the world, and you don’t need an assistant for the operation once it’s done," he explained.

• Operative characteristics. The mean skin-to-delivery time in Dr. Alanis’ series was 15 minutes, with an incision-to-closure time of 64 minutes and an estimated blood loss of 1,000 mL, all considerably greater than in leaner patients.

In another investigator’s study involving 193 superobese women, the incision-to-delivery time was nearly identical at 16 minutes, and the fetal distress rate as measured by cord pH, Apgar score, and neonatal ICU admission was significantly higher than in patients with a lower body mass index (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;209:386.e1-386.e6).

This increased risk of fetal distress was confirmed recently in a study from the National Institutes of Health Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. The analysis of 5,742 mother/singleton term neonate pairs delivered by prelabor cesarean section demonstrated that fetal distress increased with greater body mass index category. For every 10-unit increase in BMI, the cord arterial pH decreased by an adjusted value of 0.01 and the base deficit increased by 0.26 mmol/L. The relationship wasn’t linear, though; the steepest increase in fetal distress was seen in women with a prepregnancy BMI of 40 kg/L or more (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;122:262-7).

"We want these women to deliver vaginally, but be cognizant that it’s going to take longer to take that woman to the OR, and it’s going to take longer to get that baby out," he observed.

• Antibiotic prophylaxis. A major practice trend in the past several years has been a shift to routine administration of preincision antibiotics.

• Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis. Two-thirds of postsurgical DVTs are deemed preventable. The risk in pregnancy jumps from a fourfold increase with vaginal delivery over that in daily life, to a 13-fold increase with cesarean delivery, to a 26-fold increase with emergent cesarean section – and emergent cesarean section is considerably more common in superobese patients than in those of lesser BMI. Also, a BMI of 40 or more is an independent risk factor for DVT.

Dr. Alanis strongly recommends having an order set in place. While the risk of postpartum hemorrhage climbs with increasing BMI, this is not due to the use of anticoagulation. Nor does anticoagulation in superobese patients undergoing cesarean section raise their risk of hematoma or wound complications, he added.

• Wound closure. An audience show of hands indicated a strong preference for subcutaneous closure. Dr. Alanis said that’s probably fine for patients who are merely overweight, but in the superobese – women who often have 5-10 cm of subcutaneous thickness – it doesn’t improve the risk of seroma. He believes retention sutures are a good idea that hasn’t been well studied. Subcutaneous drains proved to be a bust in his study, as well as in every other study ever published.

"I would abandon the practice if I were you," the ob.gyn. advised.

Similarly, negative pressure dressings sound like a good idea but have proved disappointing in randomized clinical trials.

Dr. Alanis favors delayed closure. He’ll pack the wound for 3-4 days while granulation tissue forms, and then sew the wound closed in the office.

• Managing wound complications. To Dr. Alanis’ surprise, factors that proved unrelated to the risk of wound complications in his study of the superobese included labor as opposed to nonlabor, labor duration, rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, operative time, and emergent vs. routine vs. urgent cesarean section. Indeed, the only predictors of wound complications in his series were subcutaneous drains, associated with a 2.4-fold increased risk, and smoking, with a 2.9-fold elevated risk.

Eighty-six percent of wound complications in the superobese women were diagnosed post discharge. Wound disruption was diagnosed on median postoperative day 8.5. A total of 24% of patients with a wound complication were readmitted; 14% underwent reoperation.

Delayed closure is a very attractive way to manage seromas and hematomas. It requires healthy pink tissue and is not a technique for patients with a postoperative abscess.

Dr. Alanis reported having no financial interests germane to his presentation.

DENVER – In current practice, the majority of superobese pregnant women – those having a prepregnancy body mass index of 50 kg/m2 or more – will end up having a cesarean section. The inherent technical challenges make it crucial to have a plan in place before heading to the operating room.

"There’s a lot to think about: patient positioning, choice of incision, antibiotic prophylaxis, deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, wound care," Dr. Mark Alanis observed at the annual meeting of the Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists.

Also, it’s important to understand up front that one in three of these superobese patients will have a significant wound complication. Eighty-five percent of these are cellulitis or wound disruptions, mostly seromas, which will require packing. But one in seven of the wound complications are abscesses, and affected superobese patients require hospital readmission, said Dr. Alanis of the University of Colorado, Denver.

He presented lessons learned from his own retrospective study of 194 superobese patients who underwent cesarean section, plus several studies by other investigators. Among the highlights:

• Anesthesia evaluation. Bring the anesthesiologist in on the case early. Finding the landmarks for spinal anesthesia is tough in a superobese patient. Failed regional anesthesia is more common. In Dr. Alanis’ series, general anesthesia was required in 15% of patients – a far higher rate than in leaner women – so a careful preoperative airway assessment is essential.

• Patient positioning. Understand that positioning the superobese patient at a 20-degree tilt puts the midline far away from the surgeon, who’ll have to operate bending forward. "My back is killing me when I do these operations," the ob.gyn. said.

• Choice of incision. Dr. Alanis recommends the Pfannenstiel incision. This horizontal incision is faster than a vertical incision, the wound hurts less, healing is better, and the classic teaching that it poses an increased risk of infection in massively obese patients is a myth unsupported by data.

The key is to first mobilize the panniculus, moving it up off the suprapubic region, then securing it with a Montgomery strap tied off to the bedposts.

"It takes 5 minutes to secure the pannis. It’s the easiest thing in the world, and you don’t need an assistant for the operation once it’s done," he explained.

• Operative characteristics. The mean skin-to-delivery time in Dr. Alanis’ series was 15 minutes, with an incision-to-closure time of 64 minutes and an estimated blood loss of 1,000 mL, all considerably greater than in leaner patients.

In another investigator’s study involving 193 superobese women, the incision-to-delivery time was nearly identical at 16 minutes, and the fetal distress rate as measured by cord pH, Apgar score, and neonatal ICU admission was significantly higher than in patients with a lower body mass index (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;209:386.e1-386.e6).

This increased risk of fetal distress was confirmed recently in a study from the National Institutes of Health Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. The analysis of 5,742 mother/singleton term neonate pairs delivered by prelabor cesarean section demonstrated that fetal distress increased with greater body mass index category. For every 10-unit increase in BMI, the cord arterial pH decreased by an adjusted value of 0.01 and the base deficit increased by 0.26 mmol/L. The relationship wasn’t linear, though; the steepest increase in fetal distress was seen in women with a prepregnancy BMI of 40 kg/L or more (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;122:262-7).

"We want these women to deliver vaginally, but be cognizant that it’s going to take longer to take that woman to the OR, and it’s going to take longer to get that baby out," he observed.

• Antibiotic prophylaxis. A major practice trend in the past several years has been a shift to routine administration of preincision antibiotics.

• Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis. Two-thirds of postsurgical DVTs are deemed preventable. The risk in pregnancy jumps from a fourfold increase with vaginal delivery over that in daily life, to a 13-fold increase with cesarean delivery, to a 26-fold increase with emergent cesarean section – and emergent cesarean section is considerably more common in superobese patients than in those of lesser BMI. Also, a BMI of 40 or more is an independent risk factor for DVT.

Dr. Alanis strongly recommends having an order set in place. While the risk of postpartum hemorrhage climbs with increasing BMI, this is not due to the use of anticoagulation. Nor does anticoagulation in superobese patients undergoing cesarean section raise their risk of hematoma or wound complications, he added.

• Wound closure. An audience show of hands indicated a strong preference for subcutaneous closure. Dr. Alanis said that’s probably fine for patients who are merely overweight, but in the superobese – women who often have 5-10 cm of subcutaneous thickness – it doesn’t improve the risk of seroma. He believes retention sutures are a good idea that hasn’t been well studied. Subcutaneous drains proved to be a bust in his study, as well as in every other study ever published.

"I would abandon the practice if I were you," the ob.gyn. advised.

Similarly, negative pressure dressings sound like a good idea but have proved disappointing in randomized clinical trials.

Dr. Alanis favors delayed closure. He’ll pack the wound for 3-4 days while granulation tissue forms, and then sew the wound closed in the office.

• Managing wound complications. To Dr. Alanis’ surprise, factors that proved unrelated to the risk of wound complications in his study of the superobese included labor as opposed to nonlabor, labor duration, rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, operative time, and emergent vs. routine vs. urgent cesarean section. Indeed, the only predictors of wound complications in his series were subcutaneous drains, associated with a 2.4-fold increased risk, and smoking, with a 2.9-fold elevated risk.

Eighty-six percent of wound complications in the superobese women were diagnosed post discharge. Wound disruption was diagnosed on median postoperative day 8.5. A total of 24% of patients with a wound complication were readmitted; 14% underwent reoperation.

Delayed closure is a very attractive way to manage seromas and hematomas. It requires healthy pink tissue and is not a technique for patients with a postoperative abscess.

Dr. Alanis reported having no financial interests germane to his presentation.

DENVER – In current practice, the majority of superobese pregnant women – those having a prepregnancy body mass index of 50 kg/m2 or more – will end up having a cesarean section. The inherent technical challenges make it crucial to have a plan in place before heading to the operating room.

"There’s a lot to think about: patient positioning, choice of incision, antibiotic prophylaxis, deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, wound care," Dr. Mark Alanis observed at the annual meeting of the Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists.

Also, it’s important to understand up front that one in three of these superobese patients will have a significant wound complication. Eighty-five percent of these are cellulitis or wound disruptions, mostly seromas, which will require packing. But one in seven of the wound complications are abscesses, and affected superobese patients require hospital readmission, said Dr. Alanis of the University of Colorado, Denver.

He presented lessons learned from his own retrospective study of 194 superobese patients who underwent cesarean section, plus several studies by other investigators. Among the highlights:

• Anesthesia evaluation. Bring the anesthesiologist in on the case early. Finding the landmarks for spinal anesthesia is tough in a superobese patient. Failed regional anesthesia is more common. In Dr. Alanis’ series, general anesthesia was required in 15% of patients – a far higher rate than in leaner women – so a careful preoperative airway assessment is essential.

• Patient positioning. Understand that positioning the superobese patient at a 20-degree tilt puts the midline far away from the surgeon, who’ll have to operate bending forward. "My back is killing me when I do these operations," the ob.gyn. said.

• Choice of incision. Dr. Alanis recommends the Pfannenstiel incision. This horizontal incision is faster than a vertical incision, the wound hurts less, healing is better, and the classic teaching that it poses an increased risk of infection in massively obese patients is a myth unsupported by data.

The key is to first mobilize the panniculus, moving it up off the suprapubic region, then securing it with a Montgomery strap tied off to the bedposts.

"It takes 5 minutes to secure the pannis. It’s the easiest thing in the world, and you don’t need an assistant for the operation once it’s done," he explained.

• Operative characteristics. The mean skin-to-delivery time in Dr. Alanis’ series was 15 minutes, with an incision-to-closure time of 64 minutes and an estimated blood loss of 1,000 mL, all considerably greater than in leaner patients.

In another investigator’s study involving 193 superobese women, the incision-to-delivery time was nearly identical at 16 minutes, and the fetal distress rate as measured by cord pH, Apgar score, and neonatal ICU admission was significantly higher than in patients with a lower body mass index (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;209:386.e1-386.e6).

This increased risk of fetal distress was confirmed recently in a study from the National Institutes of Health Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. The analysis of 5,742 mother/singleton term neonate pairs delivered by prelabor cesarean section demonstrated that fetal distress increased with greater body mass index category. For every 10-unit increase in BMI, the cord arterial pH decreased by an adjusted value of 0.01 and the base deficit increased by 0.26 mmol/L. The relationship wasn’t linear, though; the steepest increase in fetal distress was seen in women with a prepregnancy BMI of 40 kg/L or more (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;122:262-7).

"We want these women to deliver vaginally, but be cognizant that it’s going to take longer to take that woman to the OR, and it’s going to take longer to get that baby out," he observed.

• Antibiotic prophylaxis. A major practice trend in the past several years has been a shift to routine administration of preincision antibiotics.

• Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis. Two-thirds of postsurgical DVTs are deemed preventable. The risk in pregnancy jumps from a fourfold increase with vaginal delivery over that in daily life, to a 13-fold increase with cesarean delivery, to a 26-fold increase with emergent cesarean section – and emergent cesarean section is considerably more common in superobese patients than in those of lesser BMI. Also, a BMI of 40 or more is an independent risk factor for DVT.

Dr. Alanis strongly recommends having an order set in place. While the risk of postpartum hemorrhage climbs with increasing BMI, this is not due to the use of anticoagulation. Nor does anticoagulation in superobese patients undergoing cesarean section raise their risk of hematoma or wound complications, he added.

• Wound closure. An audience show of hands indicated a strong preference for subcutaneous closure. Dr. Alanis said that’s probably fine for patients who are merely overweight, but in the superobese – women who often have 5-10 cm of subcutaneous thickness – it doesn’t improve the risk of seroma. He believes retention sutures are a good idea that hasn’t been well studied. Subcutaneous drains proved to be a bust in his study, as well as in every other study ever published.

"I would abandon the practice if I were you," the ob.gyn. advised.

Similarly, negative pressure dressings sound like a good idea but have proved disappointing in randomized clinical trials.

Dr. Alanis favors delayed closure. He’ll pack the wound for 3-4 days while granulation tissue forms, and then sew the wound closed in the office.

• Managing wound complications. To Dr. Alanis’ surprise, factors that proved unrelated to the risk of wound complications in his study of the superobese included labor as opposed to nonlabor, labor duration, rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, operative time, and emergent vs. routine vs. urgent cesarean section. Indeed, the only predictors of wound complications in his series were subcutaneous drains, associated with a 2.4-fold increased risk, and smoking, with a 2.9-fold elevated risk.

Eighty-six percent of wound complications in the superobese women were diagnosed post discharge. Wound disruption was diagnosed on median postoperative day 8.5. A total of 24% of patients with a wound complication were readmitted; 14% underwent reoperation.

Delayed closure is a very attractive way to manage seromas and hematomas. It requires healthy pink tissue and is not a technique for patients with a postoperative abscess.

Dr. Alanis reported having no financial interests germane to his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE SOGH ANNUAL CLINICAL MEETING

Why obesity spells higher cesarean section rates

DENVER – The obesity epidemic has been a major driver of the steep rise in cesarean section rates documented nationally since the year 2000.

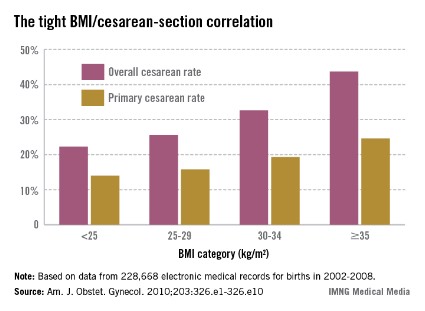

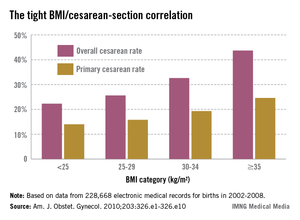

The contemporary trend is nicely captured by data on nearly 207,000 pregnancies in the mid-to-late years of the past decade collected by the Consortium on Safe Labor, a group of 19 university and community hospitals in all nine American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists districts. As prepregnancy body mass index increased, so did the cesarean section rate, Dr. Mark Alanis observed at the annual meeting of the Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists.

The Consortium used as their highest body mass index (BMI) category those women with a prepregnancy BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more, who made up 21% of their study population. Nationally, 7.6% of the obstetric population is extremely obese as defined by a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or more. The superobese – women with a prepregnancy BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more – make up a smaller subset, but they pose a special challenge for obstetricians. In the three studies that have examined cesarean section rates in superobese patients, one of which was conducted by Dr. Alanis, the rates were 55%, 49%, and 56%.

"It makes you wonder if it’s worth doing a randomized, controlled trial of scheduled primary cesarean section for women with a BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more. Is it more cost effective to try to do labor or just do the cesarean section? We don’t know," he said.

Why do obese women have a higher rate of cesarean section? The answer is beyond dispute, yet not widely appreciated; it’s because obese women tend to have ineffective uterine contractions in early labor, according to Dr. Alanis of the University of Colorado, Denver.

Persuasive evidence exists that greater body weight correlates with slowed cervical dilation. The first stage of labor is prolonged by about 2 hours in obese women. Dystocia occurs before 7 cm.

"You do these cesarean sections between 4 and 7 cm. You don’t do them after 7 cm very often," he noted. "The bottom line is if you can get your obese patient past 7 cm and she’s clearly in active labor, she’ll deliver just as easily as a lean patient."

Compelling data provided by the National Institutes of Health Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network show no differences in uterine forces or the length of the second stage of labor depending upon prepregnancy BMI in 5,341 nulliparous women.

"Maternal BMI in nulliparous women reaching the second stage is not associated with a higher incidence of cesarean delivery," according to the investigators (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118:1309-13).

This finding confirms earlier work by Australian/New Zealand clinical trialists in a study involving 2,629 nulliparous women who went into labor after 37 weeks’ gestation. Being overweight or obese, respectively, was associated with adjusted 39% and 2.9-fold increased likelihood of cesarean delivery during the first stage of labor, compared with normal-weight women, but no increase in second-stage cesarean delivery (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;117:1315-22).

These findings of an overall longer duration and slower progression of the early part of the first stage of labor have led to a proposal for adoption of a separate obese labor curve (Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;120:130-5).

"We probably should," according to Dr. Alanis.

The indication for cesarean section in obese patients is disproportionately failure to progress. Fetal distress as a trigger for cesarean delivery is not more common than in normal-weight women.

The explanation for the slower course of first-stage labor in obese women remains unclear, according to Dr. Alanis. Neither smooth muscle content nor contraction strength differs between obese and leaner women.

Dr. Alanis offers vaginal birth after cesarean section to obese patients he considers to have a decent chance of success. But he explains to them that they have a higher risk of uterine rupture, are more likely to develop endometritis, and are less likely to have a successful vaginal delivery than are normal-weight women, based upon data from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network.

"So approach TOLAC [trial of labor after cesarean] cautiously," he advised.

Dr. Alanis reported having no financial interests germane to his presentation.

DENVER – The obesity epidemic has been a major driver of the steep rise in cesarean section rates documented nationally since the year 2000.

The contemporary trend is nicely captured by data on nearly 207,000 pregnancies in the mid-to-late years of the past decade collected by the Consortium on Safe Labor, a group of 19 university and community hospitals in all nine American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists districts. As prepregnancy body mass index increased, so did the cesarean section rate, Dr. Mark Alanis observed at the annual meeting of the Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists.

The Consortium used as their highest body mass index (BMI) category those women with a prepregnancy BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more, who made up 21% of their study population. Nationally, 7.6% of the obstetric population is extremely obese as defined by a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or more. The superobese – women with a prepregnancy BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more – make up a smaller subset, but they pose a special challenge for obstetricians. In the three studies that have examined cesarean section rates in superobese patients, one of which was conducted by Dr. Alanis, the rates were 55%, 49%, and 56%.

"It makes you wonder if it’s worth doing a randomized, controlled trial of scheduled primary cesarean section for women with a BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more. Is it more cost effective to try to do labor or just do the cesarean section? We don’t know," he said.

Why do obese women have a higher rate of cesarean section? The answer is beyond dispute, yet not widely appreciated; it’s because obese women tend to have ineffective uterine contractions in early labor, according to Dr. Alanis of the University of Colorado, Denver.

Persuasive evidence exists that greater body weight correlates with slowed cervical dilation. The first stage of labor is prolonged by about 2 hours in obese women. Dystocia occurs before 7 cm.

"You do these cesarean sections between 4 and 7 cm. You don’t do them after 7 cm very often," he noted. "The bottom line is if you can get your obese patient past 7 cm and she’s clearly in active labor, she’ll deliver just as easily as a lean patient."

Compelling data provided by the National Institutes of Health Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network show no differences in uterine forces or the length of the second stage of labor depending upon prepregnancy BMI in 5,341 nulliparous women.

"Maternal BMI in nulliparous women reaching the second stage is not associated with a higher incidence of cesarean delivery," according to the investigators (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118:1309-13).

This finding confirms earlier work by Australian/New Zealand clinical trialists in a study involving 2,629 nulliparous women who went into labor after 37 weeks’ gestation. Being overweight or obese, respectively, was associated with adjusted 39% and 2.9-fold increased likelihood of cesarean delivery during the first stage of labor, compared with normal-weight women, but no increase in second-stage cesarean delivery (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;117:1315-22).

These findings of an overall longer duration and slower progression of the early part of the first stage of labor have led to a proposal for adoption of a separate obese labor curve (Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;120:130-5).

"We probably should," according to Dr. Alanis.

The indication for cesarean section in obese patients is disproportionately failure to progress. Fetal distress as a trigger for cesarean delivery is not more common than in normal-weight women.

The explanation for the slower course of first-stage labor in obese women remains unclear, according to Dr. Alanis. Neither smooth muscle content nor contraction strength differs between obese and leaner women.

Dr. Alanis offers vaginal birth after cesarean section to obese patients he considers to have a decent chance of success. But he explains to them that they have a higher risk of uterine rupture, are more likely to develop endometritis, and are less likely to have a successful vaginal delivery than are normal-weight women, based upon data from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network.

"So approach TOLAC [trial of labor after cesarean] cautiously," he advised.

Dr. Alanis reported having no financial interests germane to his presentation.

DENVER – The obesity epidemic has been a major driver of the steep rise in cesarean section rates documented nationally since the year 2000.

The contemporary trend is nicely captured by data on nearly 207,000 pregnancies in the mid-to-late years of the past decade collected by the Consortium on Safe Labor, a group of 19 university and community hospitals in all nine American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists districts. As prepregnancy body mass index increased, so did the cesarean section rate, Dr. Mark Alanis observed at the annual meeting of the Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists.

The Consortium used as their highest body mass index (BMI) category those women with a prepregnancy BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more, who made up 21% of their study population. Nationally, 7.6% of the obstetric population is extremely obese as defined by a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or more. The superobese – women with a prepregnancy BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more – make up a smaller subset, but they pose a special challenge for obstetricians. In the three studies that have examined cesarean section rates in superobese patients, one of which was conducted by Dr. Alanis, the rates were 55%, 49%, and 56%.

"It makes you wonder if it’s worth doing a randomized, controlled trial of scheduled primary cesarean section for women with a BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more. Is it more cost effective to try to do labor or just do the cesarean section? We don’t know," he said.

Why do obese women have a higher rate of cesarean section? The answer is beyond dispute, yet not widely appreciated; it’s because obese women tend to have ineffective uterine contractions in early labor, according to Dr. Alanis of the University of Colorado, Denver.

Persuasive evidence exists that greater body weight correlates with slowed cervical dilation. The first stage of labor is prolonged by about 2 hours in obese women. Dystocia occurs before 7 cm.

"You do these cesarean sections between 4 and 7 cm. You don’t do them after 7 cm very often," he noted. "The bottom line is if you can get your obese patient past 7 cm and she’s clearly in active labor, she’ll deliver just as easily as a lean patient."

Compelling data provided by the National Institutes of Health Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network show no differences in uterine forces or the length of the second stage of labor depending upon prepregnancy BMI in 5,341 nulliparous women.

"Maternal BMI in nulliparous women reaching the second stage is not associated with a higher incidence of cesarean delivery," according to the investigators (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118:1309-13).

This finding confirms earlier work by Australian/New Zealand clinical trialists in a study involving 2,629 nulliparous women who went into labor after 37 weeks’ gestation. Being overweight or obese, respectively, was associated with adjusted 39% and 2.9-fold increased likelihood of cesarean delivery during the first stage of labor, compared with normal-weight women, but no increase in second-stage cesarean delivery (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;117:1315-22).

These findings of an overall longer duration and slower progression of the early part of the first stage of labor have led to a proposal for adoption of a separate obese labor curve (Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;120:130-5).

"We probably should," according to Dr. Alanis.

The indication for cesarean section in obese patients is disproportionately failure to progress. Fetal distress as a trigger for cesarean delivery is not more common than in normal-weight women.

The explanation for the slower course of first-stage labor in obese women remains unclear, according to Dr. Alanis. Neither smooth muscle content nor contraction strength differs between obese and leaner women.

Dr. Alanis offers vaginal birth after cesarean section to obese patients he considers to have a decent chance of success. But he explains to them that they have a higher risk of uterine rupture, are more likely to develop endometritis, and are less likely to have a successful vaginal delivery than are normal-weight women, based upon data from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network.

"So approach TOLAC [trial of labor after cesarean] cautiously," he advised.

Dr. Alanis reported having no financial interests germane to his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE SOGH ANNUAL CLINICAL MEETING

Evaluation for possible early pregnancy failure

DENVER – There is a slew of ultrasound findings that are equivocal or downright worrisome for the diagnosis of early pregnancy failure, but the list of definitive findings is short – and even those are fraught with controversy, according to Dr. Roxanne Vrees.

"In a highly desired pregnancy, even with ultrasound findings that are perhaps suggestive of early pregnancy failure, I think watchful waiting has a really important role," said Dr. Vrees, an ob.gyn. at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

She is also on the staff at the Women and Infants Hospital in Providence, where she works in a unique women’s emergency department staffed 24/7 exclusively by ob.gyn. attending physicians. Traditional emergency medicine physicians are not in the picture. This busy women’s ED averages nearly 30,000 visits annually, so Dr. Vrees and her colleagues have acquired considerable experience in emergency ob.gyn. However, because the facility is licensed by the state as an ED, by law any patient who comes in must be treated, so medical backup is available around the clock for patients who present with chest pain or otherwise fall outside the generalist ob.gyn.’s scope.

Early pregnancy failure occurs in 15%-20% of clinically recognized pregnancies. The most common symptom is vaginal bleeding, which occurs in one-quarter of all known first-trimester pregnancies, half of which end in pregnancy failure.

Dr. Vrees emphasized that no single aspect of the work-up for early pregnancy failure should drive patient management. That ought to be based upon a combination of the patient’s symptoms, laboratory findings, physical exam, and pelvic ultrasound.

In the setting of worrisome ultrasound findings, the most important step in management is to get a repeat ultrasound under real-time observation. The use of cine loops in order to visualize the entire gestational sac is valuable.

"Most obstetricians underutilize this. You’re unlikely to miss a yolk sac or embryo, and you’re getting a true report of sac diameter, not a random measurement from a snapshot," she explained at the annual meeting of the Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists.

Worrisome but nondefinitive findings suggestive of early pregnancy loss include a slow fetal heart rate, an unusual appearance of the uterine lining, and a sac that is small, grossly distorted, enlarged, irregularly contoured, or low in position.

Maternal gestational age is a key consideration in defining a slow fetal heart rate by M-mode ultrasound. At a menstrual age of 6.2 weeks or less, a normal fetal heart rate is 100 bpm or more; less than 90 bpm is considered slow. In contrast, at 6.3-7.0 weeks, normal is defined as 120 bpm or more, and a fetal heart rate of less than 110 bpm is considered slow. When a slow fetal heart rate is detected at 6.0-7.0 weeks, the risk of subsequent first-trimester fetal demise remains elevated at about 25% even if the heart rate is normal at follow-up at 8.0 weeks (Radiology;2005;236:643-6).

The absolute ultrasound criteria for early pregnancy failure used at the Women and Infants Hospital as well as in many other settings are no fetal heart beat in an embryo more than 5 mm in crown-rump length, or menstrual age known to be greater than 6.5 weeks with no heart beat.

However, a group of investigators led by Dr. Yazan Abdallah of Imperial College London has argued that current definitions used to diagnose early pregnancy failure are potentially unsafe and could result in inadvertent termination of wanted pregnancies. Given the inherent inter- and intraobserver variation in ultrasound measurements, they have urged more conservative criteria for the definitive diagnosis of early pregnancy failure: specifically, a crown-rump length cutoff of greater than 7 mm instead of the widely used 5 mm, and a mean gestational sac diameter cutoff of more than 25 mm.

Dr. Abdallah and his coworkers support their argument on the basis of their observational, prospective cross-sectional study involving 1,060 consecutive women diagnosed with intrauterine pregnancy of uncertain viability. This diagnosis was based upon a symptom-generated ultrasound that showed either an empty gestational sac; a gestational sac with a yolk sac but no embryo when the mean gestational sac diameter was either less than 20 mm or less than 30 mm; or an embryo with an absent heart beat and a crown-rump length of either less than 6 mm or less than 8 mm.

The primary endpoint was a viable pregnancy upon routine first-trimester screening ultrasound at 11-14 weeks. At that point, 473 of the women had viable pregnancies and 587 did not.

When neither the yolk sac nor the embryo was visualized on the initial ultrasound, the false-positive rate for diagnosis of early pregnancy failure was 4.4% when a mean gestational sac diameter of 16 mm was used as a cutoff and 0.5% when 20 mm was the cutoff. Only when a cutoff of 21 mm was utilized did the false-positive rate fall to 0.

If a yolk sac was present but an embryo wasn’t, the false-positive rate was 2.6% with a mean gestational sac diameter cutoff of 16 mm and 0.4% with a cutoff of 20 mm. Again, there were no false positives when a cutoff of 21 mm was employed.

When a yolk sac and embryo were visible but a fetal heartbeat was not apparent, the false-positive rate for miscarriage was 8.3% with a crown-rump length cutoff of 5 mm. At a cutoff of 5.3 mm, there were no false-positive results (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;38:497-502).

When Dr. Vrees asked the audience for a show of hands as to who utilizes a mean gestational sac diameter cutoff of 21 mm to define early pregnancy loss in the absence of both a yolk sac and embryo, only a couple of ob.gyns. responded affirmatively. Some audience members indicated they use a cutoff as low as 16 mm.

"We see great variability at our institution, too, in the definition of early pregnancy failure based upon mean gestational sac diameter," according to Dr. Vrees.

The lack of unanimity on this point, coupled with the remote likelihood of physical harm in waiting 7-10 days to repeat an ultrasound scan, figure prominently in her advocacy of expectant management.

She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

DENVER – There is a slew of ultrasound findings that are equivocal or downright worrisome for the diagnosis of early pregnancy failure, but the list of definitive findings is short – and even those are fraught with controversy, according to Dr. Roxanne Vrees.

"In a highly desired pregnancy, even with ultrasound findings that are perhaps suggestive of early pregnancy failure, I think watchful waiting has a really important role," said Dr. Vrees, an ob.gyn. at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

She is also on the staff at the Women and Infants Hospital in Providence, where she works in a unique women’s emergency department staffed 24/7 exclusively by ob.gyn. attending physicians. Traditional emergency medicine physicians are not in the picture. This busy women’s ED averages nearly 30,000 visits annually, so Dr. Vrees and her colleagues have acquired considerable experience in emergency ob.gyn. However, because the facility is licensed by the state as an ED, by law any patient who comes in must be treated, so medical backup is available around the clock for patients who present with chest pain or otherwise fall outside the generalist ob.gyn.’s scope.

Early pregnancy failure occurs in 15%-20% of clinically recognized pregnancies. The most common symptom is vaginal bleeding, which occurs in one-quarter of all known first-trimester pregnancies, half of which end in pregnancy failure.

Dr. Vrees emphasized that no single aspect of the work-up for early pregnancy failure should drive patient management. That ought to be based upon a combination of the patient’s symptoms, laboratory findings, physical exam, and pelvic ultrasound.

In the setting of worrisome ultrasound findings, the most important step in management is to get a repeat ultrasound under real-time observation. The use of cine loops in order to visualize the entire gestational sac is valuable.

"Most obstetricians underutilize this. You’re unlikely to miss a yolk sac or embryo, and you’re getting a true report of sac diameter, not a random measurement from a snapshot," she explained at the annual meeting of the Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists.

Worrisome but nondefinitive findings suggestive of early pregnancy loss include a slow fetal heart rate, an unusual appearance of the uterine lining, and a sac that is small, grossly distorted, enlarged, irregularly contoured, or low in position.

Maternal gestational age is a key consideration in defining a slow fetal heart rate by M-mode ultrasound. At a menstrual age of 6.2 weeks or less, a normal fetal heart rate is 100 bpm or more; less than 90 bpm is considered slow. In contrast, at 6.3-7.0 weeks, normal is defined as 120 bpm or more, and a fetal heart rate of less than 110 bpm is considered slow. When a slow fetal heart rate is detected at 6.0-7.0 weeks, the risk of subsequent first-trimester fetal demise remains elevated at about 25% even if the heart rate is normal at follow-up at 8.0 weeks (Radiology;2005;236:643-6).

The absolute ultrasound criteria for early pregnancy failure used at the Women and Infants Hospital as well as in many other settings are no fetal heart beat in an embryo more than 5 mm in crown-rump length, or menstrual age known to be greater than 6.5 weeks with no heart beat.

However, a group of investigators led by Dr. Yazan Abdallah of Imperial College London has argued that current definitions used to diagnose early pregnancy failure are potentially unsafe and could result in inadvertent termination of wanted pregnancies. Given the inherent inter- and intraobserver variation in ultrasound measurements, they have urged more conservative criteria for the definitive diagnosis of early pregnancy failure: specifically, a crown-rump length cutoff of greater than 7 mm instead of the widely used 5 mm, and a mean gestational sac diameter cutoff of more than 25 mm.

Dr. Abdallah and his coworkers support their argument on the basis of their observational, prospective cross-sectional study involving 1,060 consecutive women diagnosed with intrauterine pregnancy of uncertain viability. This diagnosis was based upon a symptom-generated ultrasound that showed either an empty gestational sac; a gestational sac with a yolk sac but no embryo when the mean gestational sac diameter was either less than 20 mm or less than 30 mm; or an embryo with an absent heart beat and a crown-rump length of either less than 6 mm or less than 8 mm.

The primary endpoint was a viable pregnancy upon routine first-trimester screening ultrasound at 11-14 weeks. At that point, 473 of the women had viable pregnancies and 587 did not.

When neither the yolk sac nor the embryo was visualized on the initial ultrasound, the false-positive rate for diagnosis of early pregnancy failure was 4.4% when a mean gestational sac diameter of 16 mm was used as a cutoff and 0.5% when 20 mm was the cutoff. Only when a cutoff of 21 mm was utilized did the false-positive rate fall to 0.

If a yolk sac was present but an embryo wasn’t, the false-positive rate was 2.6% with a mean gestational sac diameter cutoff of 16 mm and 0.4% with a cutoff of 20 mm. Again, there were no false positives when a cutoff of 21 mm was employed.

When a yolk sac and embryo were visible but a fetal heartbeat was not apparent, the false-positive rate for miscarriage was 8.3% with a crown-rump length cutoff of 5 mm. At a cutoff of 5.3 mm, there were no false-positive results (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;38:497-502).

When Dr. Vrees asked the audience for a show of hands as to who utilizes a mean gestational sac diameter cutoff of 21 mm to define early pregnancy loss in the absence of both a yolk sac and embryo, only a couple of ob.gyns. responded affirmatively. Some audience members indicated they use a cutoff as low as 16 mm.

"We see great variability at our institution, too, in the definition of early pregnancy failure based upon mean gestational sac diameter," according to Dr. Vrees.

The lack of unanimity on this point, coupled with the remote likelihood of physical harm in waiting 7-10 days to repeat an ultrasound scan, figure prominently in her advocacy of expectant management.

She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

DENVER – There is a slew of ultrasound findings that are equivocal or downright worrisome for the diagnosis of early pregnancy failure, but the list of definitive findings is short – and even those are fraught with controversy, according to Dr. Roxanne Vrees.

"In a highly desired pregnancy, even with ultrasound findings that are perhaps suggestive of early pregnancy failure, I think watchful waiting has a really important role," said Dr. Vrees, an ob.gyn. at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

She is also on the staff at the Women and Infants Hospital in Providence, where she works in a unique women’s emergency department staffed 24/7 exclusively by ob.gyn. attending physicians. Traditional emergency medicine physicians are not in the picture. This busy women’s ED averages nearly 30,000 visits annually, so Dr. Vrees and her colleagues have acquired considerable experience in emergency ob.gyn. However, because the facility is licensed by the state as an ED, by law any patient who comes in must be treated, so medical backup is available around the clock for patients who present with chest pain or otherwise fall outside the generalist ob.gyn.’s scope.

Early pregnancy failure occurs in 15%-20% of clinically recognized pregnancies. The most common symptom is vaginal bleeding, which occurs in one-quarter of all known first-trimester pregnancies, half of which end in pregnancy failure.

Dr. Vrees emphasized that no single aspect of the work-up for early pregnancy failure should drive patient management. That ought to be based upon a combination of the patient’s symptoms, laboratory findings, physical exam, and pelvic ultrasound.

In the setting of worrisome ultrasound findings, the most important step in management is to get a repeat ultrasound under real-time observation. The use of cine loops in order to visualize the entire gestational sac is valuable.

"Most obstetricians underutilize this. You’re unlikely to miss a yolk sac or embryo, and you’re getting a true report of sac diameter, not a random measurement from a snapshot," she explained at the annual meeting of the Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists.

Worrisome but nondefinitive findings suggestive of early pregnancy loss include a slow fetal heart rate, an unusual appearance of the uterine lining, and a sac that is small, grossly distorted, enlarged, irregularly contoured, or low in position.

Maternal gestational age is a key consideration in defining a slow fetal heart rate by M-mode ultrasound. At a menstrual age of 6.2 weeks or less, a normal fetal heart rate is 100 bpm or more; less than 90 bpm is considered slow. In contrast, at 6.3-7.0 weeks, normal is defined as 120 bpm or more, and a fetal heart rate of less than 110 bpm is considered slow. When a slow fetal heart rate is detected at 6.0-7.0 weeks, the risk of subsequent first-trimester fetal demise remains elevated at about 25% even if the heart rate is normal at follow-up at 8.0 weeks (Radiology;2005;236:643-6).

The absolute ultrasound criteria for early pregnancy failure used at the Women and Infants Hospital as well as in many other settings are no fetal heart beat in an embryo more than 5 mm in crown-rump length, or menstrual age known to be greater than 6.5 weeks with no heart beat.

However, a group of investigators led by Dr. Yazan Abdallah of Imperial College London has argued that current definitions used to diagnose early pregnancy failure are potentially unsafe and could result in inadvertent termination of wanted pregnancies. Given the inherent inter- and intraobserver variation in ultrasound measurements, they have urged more conservative criteria for the definitive diagnosis of early pregnancy failure: specifically, a crown-rump length cutoff of greater than 7 mm instead of the widely used 5 mm, and a mean gestational sac diameter cutoff of more than 25 mm.

Dr. Abdallah and his coworkers support their argument on the basis of their observational, prospective cross-sectional study involving 1,060 consecutive women diagnosed with intrauterine pregnancy of uncertain viability. This diagnosis was based upon a symptom-generated ultrasound that showed either an empty gestational sac; a gestational sac with a yolk sac but no embryo when the mean gestational sac diameter was either less than 20 mm or less than 30 mm; or an embryo with an absent heart beat and a crown-rump length of either less than 6 mm or less than 8 mm.

The primary endpoint was a viable pregnancy upon routine first-trimester screening ultrasound at 11-14 weeks. At that point, 473 of the women had viable pregnancies and 587 did not.

When neither the yolk sac nor the embryo was visualized on the initial ultrasound, the false-positive rate for diagnosis of early pregnancy failure was 4.4% when a mean gestational sac diameter of 16 mm was used as a cutoff and 0.5% when 20 mm was the cutoff. Only when a cutoff of 21 mm was utilized did the false-positive rate fall to 0.

If a yolk sac was present but an embryo wasn’t, the false-positive rate was 2.6% with a mean gestational sac diameter cutoff of 16 mm and 0.4% with a cutoff of 20 mm. Again, there were no false positives when a cutoff of 21 mm was employed.

When a yolk sac and embryo were visible but a fetal heartbeat was not apparent, the false-positive rate for miscarriage was 8.3% with a crown-rump length cutoff of 5 mm. At a cutoff of 5.3 mm, there were no false-positive results (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;38:497-502).

When Dr. Vrees asked the audience for a show of hands as to who utilizes a mean gestational sac diameter cutoff of 21 mm to define early pregnancy loss in the absence of both a yolk sac and embryo, only a couple of ob.gyns. responded affirmatively. Some audience members indicated they use a cutoff as low as 16 mm.

"We see great variability at our institution, too, in the definition of early pregnancy failure based upon mean gestational sac diameter," according to Dr. Vrees.

The lack of unanimity on this point, coupled with the remote likelihood of physical harm in waiting 7-10 days to repeat an ultrasound scan, figure prominently in her advocacy of expectant management.

She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE SOGH ANNUAL CLINICAL MEETING

Implementing hospital laborist program cut cesarean rates

DENVER – The newly published first data showing improved clinical outcomes after adoption of a full-time hospital laborist program was roundly celebrated at the annual meeting of the Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists.

Dr. Thomas J. Garite presented highlights of this freshly published retrospective observational study (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;209:251.e1-6) conducted at a large-delivery-volume tertiary hospital in Las Vegas. Dr. Garite and his coinvestigators, led by Dr. Brian K. Iriye, compared hospital-wide cesarean delivery rates for 6,206 nulliparous, term, singleton live births during 2006-2011.

This was a period of change in how labor and delivery was organized at the hospital. During the first 16 months of the study period, the traditional private-practice model of patient care was in place, with ob.gyns. on call and no laborists in the house. This was followed by a 14-month interlude in which local private-practice ob.gyns. got together and made sure that a community physician was continuously in-hospital to provide laborist coverage.

"I call that the doc-in-a-box model," said Dr. Garite, professor emeritus and former chair of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Irvine.

Finally came a 24-month period with full-time laborists – that is, ob.gyns. without a private practice – providing in-hospital coverage 24/7.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the hospital’s cesarean section rate was roughly 25% lower after implementation of the full-time laborist program than in either of the other two periods.

"I haven’t seen other studies to date that demonstrate these kinds of outcome advantages for this kind of practice. I think we’re going to see a lot more. But until we do, a lot of people who don’t like change are going to be saying, ‘Wait, where’s the proof?’ Well, this is the beginning of the proof of something I believe in strongly," declared Dr. Garite, who is also editor-in-chief of the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and chief clinical officer at PeriGen, a provider of fetal surveillance systems.

Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists (SOGH) board member Dr. Jennifer Tessmer-Tuck hailed the new study as "the best and almost the only" clinical outcome data to date showing the advantages of the ob.gyn. hospitalist model of care. And it was a long time coming, she noted: a full 10½ years since Dr. Louis Weinstein of the Medical College of Ohio, Toledo, heralded the birth of a radically different form of ob.gyn. practice in his seminal essay "The laborist: A new focus of practice for the obstetrician" (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;188:310-2).

"We have a lot to do. SOGH would really like to have more of a research platform and be able to put ourselves out there. There’s really a gap in care, and we’re hoping to jump in and fill it," said Dr. Tessmer-Tuck, director of North Memorial Medical Center Laborist Associates in Robbinsdale, Minn.

But while the SOGH leadership is eager to see the field assume a bigger research presence, it’s a challenge. Most society members, when they talk about why they became hospitalists, say they had burned out in traditional private practice, with its demanding on-call schedule. They sought well-defined hours, perhaps more family time. Given those priorities, taking on a research project can sound daunting, even though the fruits of such a project might enhance the standing of the young subspecialty.

Dr. Garite reported that the cesarean section rate at the tertiary center was 33.2% during the 24 months when full-time laborists were on hand, compared with 39.2% under the traditional private practice model with no laborists, and 38.7% with laborist coverage by community staff. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for maternal age, physician age, race, gestational age, induction of labor, birth weight, and maternal weight, the hospital’s cesarean section rate after the introduction of full-time laborists was 27% lower than in the earlier period of no laborists and 23% less than with community laborist care.

There were no differences between the three groups in rates of low Apgar scores, metabolic acidosis, or any other parameters of adverse neonatal or maternal outcome.

During the study years of 2006-2011, cesarean section rates at the other hospitals in the city were either stable or rising.

Asked why hospital-wide cesarean section rates dropped significantly once full-time obstetric hospitalists were in place, Dr. Garite replied, "It’s not, for example, the patient with abruption who comes in the door; she’s going to get a cesarean section whether a hospitalist is there or some other doctor is covering. Instead, it’s the patient who has what I call ‘failure to wait,’ a.k.a. failure to progress, or the 4 o’clock induction that hasn’t made any progress ... There are lots of examples of why cesarean section rates change with a hospitalist in place, especially if you look at the correlation between cesarean sections and time of day."

Dr. Tessmer-Tuck said she found the Las Vegas study highly relevant because lots of hospitals throughout the country are now going through a similar transition from traditional on-call practice to around-the-clock coverage provided by rotating private practice community laborists, while pondering a possible move to full-time laborists.

"This is where many of our hospitals are at: They’re in the middle phase, with private-practice docs being paid to stay in-house 24 hours in case there’s an emergency," according to Dr. Tessmer-Tuck.

She said she found particularly impressive the investigators’ calculation that a full-time laborist resulted in an average of one fewer cesarean section every 2 days in a population of primiparous, term, singleton patients, with a resultant estimated savings in patient care costs of $2,823-$3,305 per day. Because a laborist might be paid $2,500 per 24-hour shift, the reduced cesarean section rate alone covers the laborist’s salary. Those are the sort of numbers hospital administrators find persuasive.

"This is a message you guys should take home with you when you go back to your own program," she said.

While the Las Vegas study provides the first evidence to be published in a major peer-reviewed journal demonstrating superior clinical outcomes with the full-time laborist model, Dr. Tessmer-Tuck noted that in addition there are several published studies suggesting that hospitals experience fewer adverse events and markedly lower payouts for bad outcomes after they implement multipronged, comprehensive obstetric patient safety programs that include bringing a laborist on board.

"Liability has become a huge issue for us. Many hospitals implement hospitalist programs mainly in order to reduce liability," according to Dr. Tessmer-Tuck.

She cited a study by ob.gyns. at New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center in which they analyzed the impact of a comprehensive patient safety program initiated in stages beginning in 2003. The interventions included mandatory labor and delivery team training aimed at enhancing physician/nurse communication, development of standardized management protocols, training in fetal heart rate monitoring interpretation, creation of a patient safety nurse position, and, in 2006, introduction of a laborist.

It’s not possible to parse out just how much of the improvement in response to the multipronged safety program was the result of adopting the laborist model, Dr. Tessmer-Tuck said, but she noted the average yearly compensation payments for patient claims or lawsuits were $27.6 million during 2003-2006, plummeting to $2.5 million per year in 2007-2009, after the laborist was in place. Moreover, sentinel adverse events such as maternal death or severe neurodevelopmental impairment in a child decreased from five in the year 2000 to none in 2008 and 2009 (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;204:97-105).

Ob.gyns. at Yale–New Haven (Conn.) Hospital introduced a similar comprehensive patient safety program, also including implementation of a 24-hour obstetrics hospitalist, during 2004-2006. During 3 years of prospective follow-up involving nearly 14,000 deliveries, they documented a significant linear decline in obstetric adverse outcomes (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;200:492e1-8). They also administered a validated workplace safety attitude questionnaire four times during 2004-2009 and documented marked improvement over time in favorable scores in the domains of job satisfaction, teamwork, and safety culture (Am J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;204:216.e1-6).

Dr. Garite and Dr. Tessmer-Tuck reported having no germane financial relationships.

DENVER – The newly published first data showing improved clinical outcomes after adoption of a full-time hospital laborist program was roundly celebrated at the annual meeting of the Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists.

Dr. Thomas J. Garite presented highlights of this freshly published retrospective observational study (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;209:251.e1-6) conducted at a large-delivery-volume tertiary hospital in Las Vegas. Dr. Garite and his coinvestigators, led by Dr. Brian K. Iriye, compared hospital-wide cesarean delivery rates for 6,206 nulliparous, term, singleton live births during 2006-2011.

This was a period of change in how labor and delivery was organized at the hospital. During the first 16 months of the study period, the traditional private-practice model of patient care was in place, with ob.gyns. on call and no laborists in the house. This was followed by a 14-month interlude in which local private-practice ob.gyns. got together and made sure that a community physician was continuously in-hospital to provide laborist coverage.

"I call that the doc-in-a-box model," said Dr. Garite, professor emeritus and former chair of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Irvine.

Finally came a 24-month period with full-time laborists – that is, ob.gyns. without a private practice – providing in-hospital coverage 24/7.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the hospital’s cesarean section rate was roughly 25% lower after implementation of the full-time laborist program than in either of the other two periods.

"I haven’t seen other studies to date that demonstrate these kinds of outcome advantages for this kind of practice. I think we’re going to see a lot more. But until we do, a lot of people who don’t like change are going to be saying, ‘Wait, where’s the proof?’ Well, this is the beginning of the proof of something I believe in strongly," declared Dr. Garite, who is also editor-in-chief of the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and chief clinical officer at PeriGen, a provider of fetal surveillance systems.

Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists (SOGH) board member Dr. Jennifer Tessmer-Tuck hailed the new study as "the best and almost the only" clinical outcome data to date showing the advantages of the ob.gyn. hospitalist model of care. And it was a long time coming, she noted: a full 10½ years since Dr. Louis Weinstein of the Medical College of Ohio, Toledo, heralded the birth of a radically different form of ob.gyn. practice in his seminal essay "The laborist: A new focus of practice for the obstetrician" (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;188:310-2).

"We have a lot to do. SOGH would really like to have more of a research platform and be able to put ourselves out there. There’s really a gap in care, and we’re hoping to jump in and fill it," said Dr. Tessmer-Tuck, director of North Memorial Medical Center Laborist Associates in Robbinsdale, Minn.

But while the SOGH leadership is eager to see the field assume a bigger research presence, it’s a challenge. Most society members, when they talk about why they became hospitalists, say they had burned out in traditional private practice, with its demanding on-call schedule. They sought well-defined hours, perhaps more family time. Given those priorities, taking on a research project can sound daunting, even though the fruits of such a project might enhance the standing of the young subspecialty.

Dr. Garite reported that the cesarean section rate at the tertiary center was 33.2% during the 24 months when full-time laborists were on hand, compared with 39.2% under the traditional private practice model with no laborists, and 38.7% with laborist coverage by community staff. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for maternal age, physician age, race, gestational age, induction of labor, birth weight, and maternal weight, the hospital’s cesarean section rate after the introduction of full-time laborists was 27% lower than in the earlier period of no laborists and 23% less than with community laborist care.

There were no differences between the three groups in rates of low Apgar scores, metabolic acidosis, or any other parameters of adverse neonatal or maternal outcome.

During the study years of 2006-2011, cesarean section rates at the other hospitals in the city were either stable or rising.

Asked why hospital-wide cesarean section rates dropped significantly once full-time obstetric hospitalists were in place, Dr. Garite replied, "It’s not, for example, the patient with abruption who comes in the door; she’s going to get a cesarean section whether a hospitalist is there or some other doctor is covering. Instead, it’s the patient who has what I call ‘failure to wait,’ a.k.a. failure to progress, or the 4 o’clock induction that hasn’t made any progress ... There are lots of examples of why cesarean section rates change with a hospitalist in place, especially if you look at the correlation between cesarean sections and time of day."

Dr. Tessmer-Tuck said she found the Las Vegas study highly relevant because lots of hospitals throughout the country are now going through a similar transition from traditional on-call practice to around-the-clock coverage provided by rotating private practice community laborists, while pondering a possible move to full-time laborists.

"This is where many of our hospitals are at: They’re in the middle phase, with private-practice docs being paid to stay in-house 24 hours in case there’s an emergency," according to Dr. Tessmer-Tuck.

She said she found particularly impressive the investigators’ calculation that a full-time laborist resulted in an average of one fewer cesarean section every 2 days in a population of primiparous, term, singleton patients, with a resultant estimated savings in patient care costs of $2,823-$3,305 per day. Because a laborist might be paid $2,500 per 24-hour shift, the reduced cesarean section rate alone covers the laborist’s salary. Those are the sort of numbers hospital administrators find persuasive.

"This is a message you guys should take home with you when you go back to your own program," she said.

While the Las Vegas study provides the first evidence to be published in a major peer-reviewed journal demonstrating superior clinical outcomes with the full-time laborist model, Dr. Tessmer-Tuck noted that in addition there are several published studies suggesting that hospitals experience fewer adverse events and markedly lower payouts for bad outcomes after they implement multipronged, comprehensive obstetric patient safety programs that include bringing a laborist on board.

"Liability has become a huge issue for us. Many hospitals implement hospitalist programs mainly in order to reduce liability," according to Dr. Tessmer-Tuck.

She cited a study by ob.gyns. at New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center in which they analyzed the impact of a comprehensive patient safety program initiated in stages beginning in 2003. The interventions included mandatory labor and delivery team training aimed at enhancing physician/nurse communication, development of standardized management protocols, training in fetal heart rate monitoring interpretation, creation of a patient safety nurse position, and, in 2006, introduction of a laborist.

It’s not possible to parse out just how much of the improvement in response to the multipronged safety program was the result of adopting the laborist model, Dr. Tessmer-Tuck said, but she noted the average yearly compensation payments for patient claims or lawsuits were $27.6 million during 2003-2006, plummeting to $2.5 million per year in 2007-2009, after the laborist was in place. Moreover, sentinel adverse events such as maternal death or severe neurodevelopmental impairment in a child decreased from five in the year 2000 to none in 2008 and 2009 (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;204:97-105).

Ob.gyns. at Yale–New Haven (Conn.) Hospital introduced a similar comprehensive patient safety program, also including implementation of a 24-hour obstetrics hospitalist, during 2004-2006. During 3 years of prospective follow-up involving nearly 14,000 deliveries, they documented a significant linear decline in obstetric adverse outcomes (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;200:492e1-8). They also administered a validated workplace safety attitude questionnaire four times during 2004-2009 and documented marked improvement over time in favorable scores in the domains of job satisfaction, teamwork, and safety culture (Am J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;204:216.e1-6).

Dr. Garite and Dr. Tessmer-Tuck reported having no germane financial relationships.

DENVER – The newly published first data showing improved clinical outcomes after adoption of a full-time hospital laborist program was roundly celebrated at the annual meeting of the Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists.

Dr. Thomas J. Garite presented highlights of this freshly published retrospective observational study (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;209:251.e1-6) conducted at a large-delivery-volume tertiary hospital in Las Vegas. Dr. Garite and his coinvestigators, led by Dr. Brian K. Iriye, compared hospital-wide cesarean delivery rates for 6,206 nulliparous, term, singleton live births during 2006-2011.

This was a period of change in how labor and delivery was organized at the hospital. During the first 16 months of the study period, the traditional private-practice model of patient care was in place, with ob.gyns. on call and no laborists in the house. This was followed by a 14-month interlude in which local private-practice ob.gyns. got together and made sure that a community physician was continuously in-hospital to provide laborist coverage.

"I call that the doc-in-a-box model," said Dr. Garite, professor emeritus and former chair of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Irvine.

Finally came a 24-month period with full-time laborists – that is, ob.gyns. without a private practice – providing in-hospital coverage 24/7.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the hospital’s cesarean section rate was roughly 25% lower after implementation of the full-time laborist program than in either of the other two periods.

"I haven’t seen other studies to date that demonstrate these kinds of outcome advantages for this kind of practice. I think we’re going to see a lot more. But until we do, a lot of people who don’t like change are going to be saying, ‘Wait, where’s the proof?’ Well, this is the beginning of the proof of something I believe in strongly," declared Dr. Garite, who is also editor-in-chief of the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and chief clinical officer at PeriGen, a provider of fetal surveillance systems.

Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists (SOGH) board member Dr. Jennifer Tessmer-Tuck hailed the new study as "the best and almost the only" clinical outcome data to date showing the advantages of the ob.gyn. hospitalist model of care. And it was a long time coming, she noted: a full 10½ years since Dr. Louis Weinstein of the Medical College of Ohio, Toledo, heralded the birth of a radically different form of ob.gyn. practice in his seminal essay "The laborist: A new focus of practice for the obstetrician" (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;188:310-2).

"We have a lot to do. SOGH would really like to have more of a research platform and be able to put ourselves out there. There’s really a gap in care, and we’re hoping to jump in and fill it," said Dr. Tessmer-Tuck, director of North Memorial Medical Center Laborist Associates in Robbinsdale, Minn.

But while the SOGH leadership is eager to see the field assume a bigger research presence, it’s a challenge. Most society members, when they talk about why they became hospitalists, say they had burned out in traditional private practice, with its demanding on-call schedule. They sought well-defined hours, perhaps more family time. Given those priorities, taking on a research project can sound daunting, even though the fruits of such a project might enhance the standing of the young subspecialty.

Dr. Garite reported that the cesarean section rate at the tertiary center was 33.2% during the 24 months when full-time laborists were on hand, compared with 39.2% under the traditional private practice model with no laborists, and 38.7% with laborist coverage by community staff. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for maternal age, physician age, race, gestational age, induction of labor, birth weight, and maternal weight, the hospital’s cesarean section rate after the introduction of full-time laborists was 27% lower than in the earlier period of no laborists and 23% less than with community laborist care.

There were no differences between the three groups in rates of low Apgar scores, metabolic acidosis, or any other parameters of adverse neonatal or maternal outcome.

During the study years of 2006-2011, cesarean section rates at the other hospitals in the city were either stable or rising.

Asked why hospital-wide cesarean section rates dropped significantly once full-time obstetric hospitalists were in place, Dr. Garite replied, "It’s not, for example, the patient with abruption who comes in the door; she’s going to get a cesarean section whether a hospitalist is there or some other doctor is covering. Instead, it’s the patient who has what I call ‘failure to wait,’ a.k.a. failure to progress, or the 4 o’clock induction that hasn’t made any progress ... There are lots of examples of why cesarean section rates change with a hospitalist in place, especially if you look at the correlation between cesarean sections and time of day."

Dr. Tessmer-Tuck said she found the Las Vegas study highly relevant because lots of hospitals throughout the country are now going through a similar transition from traditional on-call practice to around-the-clock coverage provided by rotating private practice community laborists, while pondering a possible move to full-time laborists.

"This is where many of our hospitals are at: They’re in the middle phase, with private-practice docs being paid to stay in-house 24 hours in case there’s an emergency," according to Dr. Tessmer-Tuck.

She said she found particularly impressive the investigators’ calculation that a full-time laborist resulted in an average of one fewer cesarean section every 2 days in a population of primiparous, term, singleton patients, with a resultant estimated savings in patient care costs of $2,823-$3,305 per day. Because a laborist might be paid $2,500 per 24-hour shift, the reduced cesarean section rate alone covers the laborist’s salary. Those are the sort of numbers hospital administrators find persuasive.

"This is a message you guys should take home with you when you go back to your own program," she said.

While the Las Vegas study provides the first evidence to be published in a major peer-reviewed journal demonstrating superior clinical outcomes with the full-time laborist model, Dr. Tessmer-Tuck noted that in addition there are several published studies suggesting that hospitals experience fewer adverse events and markedly lower payouts for bad outcomes after they implement multipronged, comprehensive obstetric patient safety programs that include bringing a laborist on board.

"Liability has become a huge issue for us. Many hospitals implement hospitalist programs mainly in order to reduce liability," according to Dr. Tessmer-Tuck.

She cited a study by ob.gyns. at New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center in which they analyzed the impact of a comprehensive patient safety program initiated in stages beginning in 2003. The interventions included mandatory labor and delivery team training aimed at enhancing physician/nurse communication, development of standardized management protocols, training in fetal heart rate monitoring interpretation, creation of a patient safety nurse position, and, in 2006, introduction of a laborist.

It’s not possible to parse out just how much of the improvement in response to the multipronged safety program was the result of adopting the laborist model, Dr. Tessmer-Tuck said, but she noted the average yearly compensation payments for patient claims or lawsuits were $27.6 million during 2003-2006, plummeting to $2.5 million per year in 2007-2009, after the laborist was in place. Moreover, sentinel adverse events such as maternal death or severe neurodevelopmental impairment in a child decreased from five in the year 2000 to none in 2008 and 2009 (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;204:97-105).

Ob.gyns. at Yale–New Haven (Conn.) Hospital introduced a similar comprehensive patient safety program, also including implementation of a 24-hour obstetrics hospitalist, during 2004-2006. During 3 years of prospective follow-up involving nearly 14,000 deliveries, they documented a significant linear decline in obstetric adverse outcomes (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;200:492e1-8). They also administered a validated workplace safety attitude questionnaire four times during 2004-2009 and documented marked improvement over time in favorable scores in the domains of job satisfaction, teamwork, and safety culture (Am J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;204:216.e1-6).

Dr. Garite and Dr. Tessmer-Tuck reported having no germane financial relationships.

AT THE SOGH ANNUAL CLINICAL MEETING