User login

How to reduce the open hysterectomy rate

SAN ANTONIO – About a decade ago, the Northern California Permanente Medical Group realized it had a problem: There were too many open hysterectomies being performed.

“We had a large number of low-volume surgeons doing a lot of open hysterectomies,” said Andrew Walter, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) campus in Roseville, Calif., part of Kaiser Permanente. Across 15 hospitals in the system, “our open rate was 64% in 2007.”

To address the problem, “our leadership basically set targets; we then provided surgical education and training in minimally invasive hysterectomy,” Dr. Walter said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Kaiser Permanente is a capitated system, but even so, its experience in reducing open hysterectomy rates may be useful for other systems dealing with the same problem.

At first, Dr. Walter and his colleagues didn’t know how much of an improvement could be made. “In 2008, we said, ‘Okay, 60% seems doable’” as a minimally invasive target rate, Dr. Walter said. TPMG hit that target, and “the chiefs looked at the numbers and said we can do a little bit better.” With some more effort, the rate of minimally invasive hysterectomies hit 80%, and then 90%, about where it stands today, with a corresponding drop in open rates.

“It will be interesting to see if someone says, ‘Let’s try 95%,’ ” Dr. Walter said.

However, the process hasn’t been easy, and it hasn’t been entirely evidence based, he said. “We are working with hundreds of gynecologists, and very few of them have had advanced training. But ultimately, it worked.”

Surgeons trained with TPMG peers experienced in minimally invasive hysterectomy, and both surgeons were kept on full salary during the learning process. It took about 5-15 cases before learner surgeons were considered proficient. “Funded proctoring is the most important aspect of the program,” he said.

TPMG also reduced the number of physicians doing hysterectomies from 416 to 228 in 2015. “This was the hard part, deciding who is a surgeon and who is not,” Dr. Walter said. “I would like to tell you that these were Kumbaya moments, but there was consternation, and there remains consternation about the process.” A number of ob.gyns. voluntarily gave up their surgical privileges, saying, ‘Thank God I don’t have to operate anymore,’ ” he said.

For low-volume surgeons – those who performed 10 or fewer hysterectomies a year – who wanted stay in the operating room, “we either had to push them into this training or encourage them to give up their surgical practices.” The more than 3,600 hysterectomies performed annually at TPMG facilities are now mostly done by surgeons doing at least 11 of these procedures a year, and often more than 20.

TPMG also paid for training courses at outside institutions, and department chiefs were held accountable for performance.

“Obviously, there are unique processes within Kaiser Permanente that facilitated this, but some of them are not unique. Physician support by enhanced training – that’s something that can be done. The barriers are reimbursement, and deciding who is a surgeon,” he said.

The next target is vaginal hysterectomy. Rates have been stable lately at about 30%, but “we have found that many patients, when reviewed, are vaginal hysterectomy candidates. We’ve set a target of 40%.” The procedure needs to be incentivized, Dr. Walter said, but it’s unclear how to do that at this point.

Dr. Walter reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – About a decade ago, the Northern California Permanente Medical Group realized it had a problem: There were too many open hysterectomies being performed.

“We had a large number of low-volume surgeons doing a lot of open hysterectomies,” said Andrew Walter, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) campus in Roseville, Calif., part of Kaiser Permanente. Across 15 hospitals in the system, “our open rate was 64% in 2007.”

To address the problem, “our leadership basically set targets; we then provided surgical education and training in minimally invasive hysterectomy,” Dr. Walter said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Kaiser Permanente is a capitated system, but even so, its experience in reducing open hysterectomy rates may be useful for other systems dealing with the same problem.

At first, Dr. Walter and his colleagues didn’t know how much of an improvement could be made. “In 2008, we said, ‘Okay, 60% seems doable’” as a minimally invasive target rate, Dr. Walter said. TPMG hit that target, and “the chiefs looked at the numbers and said we can do a little bit better.” With some more effort, the rate of minimally invasive hysterectomies hit 80%, and then 90%, about where it stands today, with a corresponding drop in open rates.

“It will be interesting to see if someone says, ‘Let’s try 95%,’ ” Dr. Walter said.

However, the process hasn’t been easy, and it hasn’t been entirely evidence based, he said. “We are working with hundreds of gynecologists, and very few of them have had advanced training. But ultimately, it worked.”

Surgeons trained with TPMG peers experienced in minimally invasive hysterectomy, and both surgeons were kept on full salary during the learning process. It took about 5-15 cases before learner surgeons were considered proficient. “Funded proctoring is the most important aspect of the program,” he said.

TPMG also reduced the number of physicians doing hysterectomies from 416 to 228 in 2015. “This was the hard part, deciding who is a surgeon and who is not,” Dr. Walter said. “I would like to tell you that these were Kumbaya moments, but there was consternation, and there remains consternation about the process.” A number of ob.gyns. voluntarily gave up their surgical privileges, saying, ‘Thank God I don’t have to operate anymore,’ ” he said.

For low-volume surgeons – those who performed 10 or fewer hysterectomies a year – who wanted stay in the operating room, “we either had to push them into this training or encourage them to give up their surgical practices.” The more than 3,600 hysterectomies performed annually at TPMG facilities are now mostly done by surgeons doing at least 11 of these procedures a year, and often more than 20.

TPMG also paid for training courses at outside institutions, and department chiefs were held accountable for performance.

“Obviously, there are unique processes within Kaiser Permanente that facilitated this, but some of them are not unique. Physician support by enhanced training – that’s something that can be done. The barriers are reimbursement, and deciding who is a surgeon,” he said.

The next target is vaginal hysterectomy. Rates have been stable lately at about 30%, but “we have found that many patients, when reviewed, are vaginal hysterectomy candidates. We’ve set a target of 40%.” The procedure needs to be incentivized, Dr. Walter said, but it’s unclear how to do that at this point.

Dr. Walter reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – About a decade ago, the Northern California Permanente Medical Group realized it had a problem: There were too many open hysterectomies being performed.

“We had a large number of low-volume surgeons doing a lot of open hysterectomies,” said Andrew Walter, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) campus in Roseville, Calif., part of Kaiser Permanente. Across 15 hospitals in the system, “our open rate was 64% in 2007.”

To address the problem, “our leadership basically set targets; we then provided surgical education and training in minimally invasive hysterectomy,” Dr. Walter said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Kaiser Permanente is a capitated system, but even so, its experience in reducing open hysterectomy rates may be useful for other systems dealing with the same problem.

At first, Dr. Walter and his colleagues didn’t know how much of an improvement could be made. “In 2008, we said, ‘Okay, 60% seems doable’” as a minimally invasive target rate, Dr. Walter said. TPMG hit that target, and “the chiefs looked at the numbers and said we can do a little bit better.” With some more effort, the rate of minimally invasive hysterectomies hit 80%, and then 90%, about where it stands today, with a corresponding drop in open rates.

“It will be interesting to see if someone says, ‘Let’s try 95%,’ ” Dr. Walter said.

However, the process hasn’t been easy, and it hasn’t been entirely evidence based, he said. “We are working with hundreds of gynecologists, and very few of them have had advanced training. But ultimately, it worked.”

Surgeons trained with TPMG peers experienced in minimally invasive hysterectomy, and both surgeons were kept on full salary during the learning process. It took about 5-15 cases before learner surgeons were considered proficient. “Funded proctoring is the most important aspect of the program,” he said.

TPMG also reduced the number of physicians doing hysterectomies from 416 to 228 in 2015. “This was the hard part, deciding who is a surgeon and who is not,” Dr. Walter said. “I would like to tell you that these were Kumbaya moments, but there was consternation, and there remains consternation about the process.” A number of ob.gyns. voluntarily gave up their surgical privileges, saying, ‘Thank God I don’t have to operate anymore,’ ” he said.

For low-volume surgeons – those who performed 10 or fewer hysterectomies a year – who wanted stay in the operating room, “we either had to push them into this training or encourage them to give up their surgical practices.” The more than 3,600 hysterectomies performed annually at TPMG facilities are now mostly done by surgeons doing at least 11 of these procedures a year, and often more than 20.

TPMG also paid for training courses at outside institutions, and department chiefs were held accountable for performance.

“Obviously, there are unique processes within Kaiser Permanente that facilitated this, but some of them are not unique. Physician support by enhanced training – that’s something that can be done. The barriers are reimbursement, and deciding who is a surgeon,” he said.

The next target is vaginal hysterectomy. Rates have been stable lately at about 30%, but “we have found that many patients, when reviewed, are vaginal hysterectomy candidates. We’ve set a target of 40%.” The procedure needs to be incentivized, Dr. Walter said, but it’s unclear how to do that at this point.

Dr. Walter reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SGS 2017

Liposomal bupivacaine cut need for opioids after gyn surgery

SAN ANTONIO – Liposomal bupivacaine reduced pain after midurethral sling surgery, compared with placebo in a randomized trial, but because of its cost it may be best to keep it in reserve for women who can’t, or shouldn’t, take opioids, said lead investigator Donna Mazloomdoost, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati.

Fifty-four women were randomized to receive liposomal bupivacaine (Exparel) injected into the two trocar paths and the vaginal incision at the end of the procedure; 55 others were injected with normal saline as a placebo.

Fewer women in the liposomal bupivacaine group took narcotics on postop day 2 (12 versus 27, P = .006). However, there was no difference in overall satisfaction with pain control at 1 and 2 weeks follow-up.

Even so, “for this common outpatient surgery, liposomal bupivacaine may be a beneficial addition for pain control,” the investigators concluded.

Liposomal bupivacaine is a local anesthetic with slow release over 72 hours, approved for treatment of postsurgical pain in 2011. “The cost is about $300 at our institution; the charge to the patient is about $1,000,” Dr. Mazloomdoost said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Because of the expense, liposomal bupivacaine is restricted in many hospitals, and gynecologic surgeons are trying to figure out what role it has, if any, in low-pain outpatient procedures like midurethral slings.

“I don’t know if you can justify” routine use for low-pain procedures, “but if you are concerned about opioid” use after surgery – intolerance or addiction – “I would use this,” Dr. Mazloomdoost said.

The investigators expanded 20 mL of liposomal bupivacaine with 10 mL of normal saline for a total of 30 mL. It was split evenly between the two trocar sites and the vaginal epithelium; 10 mL was injected in each of the three sites shortly before the intervention women were roused from anesthesia. The needle was inserted as deeply as possible, and liposomal bupivacaine was injected as the needle was drawn back. Because of the viscosity, it takes at least a 25-gauge needle.

Surgeons knew that they were injecting liposomal bupivacaine instead of saline because of the thickness and color, but they weren’t the ones collecting data, and the women were blinded to the treatment.

Patients were a mean age of 52 years. The mean body mass index was 29.2 kg/m2 in the liposomal bupivacaine group, and 31.6 kg/m2 in the placebo group; there were otherwise no significant demographic differences. Fifty-two women in the liposomal bupivacaine group received midazolam during anesthesia induction versus 44 women receiving placebo, but there were no significant differences in operating time or the number of women in each group who had concomitant anterior or urethrocele repairs, and no differences in urinary retention, time to first bowel movement – about 2 days – or adverse events. The most common adverse events in both groups were nausea/vomiting, headache, and itching.

Women in both groups received intravenous acetaminophen before anesthesia induction, and ketorolac before leaving the operating room; 10 mL of lidocaine with epinephrine was injected into the trocar paths and vaginal epithelium prior to the first incision.

The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – Liposomal bupivacaine reduced pain after midurethral sling surgery, compared with placebo in a randomized trial, but because of its cost it may be best to keep it in reserve for women who can’t, or shouldn’t, take opioids, said lead investigator Donna Mazloomdoost, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati.

Fifty-four women were randomized to receive liposomal bupivacaine (Exparel) injected into the two trocar paths and the vaginal incision at the end of the procedure; 55 others were injected with normal saline as a placebo.

Fewer women in the liposomal bupivacaine group took narcotics on postop day 2 (12 versus 27, P = .006). However, there was no difference in overall satisfaction with pain control at 1 and 2 weeks follow-up.

Even so, “for this common outpatient surgery, liposomal bupivacaine may be a beneficial addition for pain control,” the investigators concluded.

Liposomal bupivacaine is a local anesthetic with slow release over 72 hours, approved for treatment of postsurgical pain in 2011. “The cost is about $300 at our institution; the charge to the patient is about $1,000,” Dr. Mazloomdoost said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Because of the expense, liposomal bupivacaine is restricted in many hospitals, and gynecologic surgeons are trying to figure out what role it has, if any, in low-pain outpatient procedures like midurethral slings.

“I don’t know if you can justify” routine use for low-pain procedures, “but if you are concerned about opioid” use after surgery – intolerance or addiction – “I would use this,” Dr. Mazloomdoost said.

The investigators expanded 20 mL of liposomal bupivacaine with 10 mL of normal saline for a total of 30 mL. It was split evenly between the two trocar sites and the vaginal epithelium; 10 mL was injected in each of the three sites shortly before the intervention women were roused from anesthesia. The needle was inserted as deeply as possible, and liposomal bupivacaine was injected as the needle was drawn back. Because of the viscosity, it takes at least a 25-gauge needle.

Surgeons knew that they were injecting liposomal bupivacaine instead of saline because of the thickness and color, but they weren’t the ones collecting data, and the women were blinded to the treatment.

Patients were a mean age of 52 years. The mean body mass index was 29.2 kg/m2 in the liposomal bupivacaine group, and 31.6 kg/m2 in the placebo group; there were otherwise no significant demographic differences. Fifty-two women in the liposomal bupivacaine group received midazolam during anesthesia induction versus 44 women receiving placebo, but there were no significant differences in operating time or the number of women in each group who had concomitant anterior or urethrocele repairs, and no differences in urinary retention, time to first bowel movement – about 2 days – or adverse events. The most common adverse events in both groups were nausea/vomiting, headache, and itching.

Women in both groups received intravenous acetaminophen before anesthesia induction, and ketorolac before leaving the operating room; 10 mL of lidocaine with epinephrine was injected into the trocar paths and vaginal epithelium prior to the first incision.

The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – Liposomal bupivacaine reduced pain after midurethral sling surgery, compared with placebo in a randomized trial, but because of its cost it may be best to keep it in reserve for women who can’t, or shouldn’t, take opioids, said lead investigator Donna Mazloomdoost, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati.

Fifty-four women were randomized to receive liposomal bupivacaine (Exparel) injected into the two trocar paths and the vaginal incision at the end of the procedure; 55 others were injected with normal saline as a placebo.

Fewer women in the liposomal bupivacaine group took narcotics on postop day 2 (12 versus 27, P = .006). However, there was no difference in overall satisfaction with pain control at 1 and 2 weeks follow-up.

Even so, “for this common outpatient surgery, liposomal bupivacaine may be a beneficial addition for pain control,” the investigators concluded.

Liposomal bupivacaine is a local anesthetic with slow release over 72 hours, approved for treatment of postsurgical pain in 2011. “The cost is about $300 at our institution; the charge to the patient is about $1,000,” Dr. Mazloomdoost said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Because of the expense, liposomal bupivacaine is restricted in many hospitals, and gynecologic surgeons are trying to figure out what role it has, if any, in low-pain outpatient procedures like midurethral slings.

“I don’t know if you can justify” routine use for low-pain procedures, “but if you are concerned about opioid” use after surgery – intolerance or addiction – “I would use this,” Dr. Mazloomdoost said.

The investigators expanded 20 mL of liposomal bupivacaine with 10 mL of normal saline for a total of 30 mL. It was split evenly between the two trocar sites and the vaginal epithelium; 10 mL was injected in each of the three sites shortly before the intervention women were roused from anesthesia. The needle was inserted as deeply as possible, and liposomal bupivacaine was injected as the needle was drawn back. Because of the viscosity, it takes at least a 25-gauge needle.

Surgeons knew that they were injecting liposomal bupivacaine instead of saline because of the thickness and color, but they weren’t the ones collecting data, and the women were blinded to the treatment.

Patients were a mean age of 52 years. The mean body mass index was 29.2 kg/m2 in the liposomal bupivacaine group, and 31.6 kg/m2 in the placebo group; there were otherwise no significant demographic differences. Fifty-two women in the liposomal bupivacaine group received midazolam during anesthesia induction versus 44 women receiving placebo, but there were no significant differences in operating time or the number of women in each group who had concomitant anterior or urethrocele repairs, and no differences in urinary retention, time to first bowel movement – about 2 days – or adverse events. The most common adverse events in both groups were nausea/vomiting, headache, and itching.

Women in both groups received intravenous acetaminophen before anesthesia induction, and ketorolac before leaving the operating room; 10 mL of lidocaine with epinephrine was injected into the trocar paths and vaginal epithelium prior to the first incision.

The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

AT SGS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Pain scores, assessed by diary, were lower in the liposomal bupivacaine group 4 hours after discharge on a 100-mm visual analogue scale (3.5 mm versus 13 mm, P = .014).

Data source: Randomized trial with 109 women at Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati.

Disclosures: The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Avoid hysterectomy in POP repairs

SAN ANTONIO – The Systematic Review Group of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons is suggesting uterine preservation, when not contraindicated, for most pelvic organ prolapse repairs to decrease mesh erosion, operating room time, and blood loss.

The advice is based on a review of 94 original studies, including 12 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 41 nonrandomized comparative studies, winnowed down to the strongest work from an original review of 7,324 abstracts through January 2017.

Short-term prolapse outcomes – 12-30 months in most of the studies – “are usually not clinically significant due to uterine preservation,” with the one exception of vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction, which the group recommended over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, Kate Meriwether, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the University of Louisville, Ky., said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Hysterectomy for prolapse surgery is common: More than 74,000 hysterectomies are done in the United States each year with prolapse as the main indication. Even so, it’s not always necessary to take out the uterus, and perhaps more than a third of women would prefer to keep theirs, Dr. Meriwether said, speaking on behalf of the SGS Systematic Review Group.

The recommendations from the Systematic Review Group must be sent to the SGS board and the full membership before they can be approved as guidelines.*

The Review Group made a grade A recommendation for vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, meaning it was based on high-quality evidence. The rest of the advice came in the form of suggestions, based on moderate grade B evidence, often nonrandomized comparative studies and case reviews.

The Review Group suggested uterine preservation during laparoscopic native tissue prolapse repair to reduce operating room (OR) time and blood loss, and preserve vaginal length, based on four nonrandomized comparison studies using various approaches, with a total of 446 women and up to 3 years’ follow-up. There might be a higher risk of apical recurrence without hysterectomy, but without worsening of prolapse symptoms.

The Review Group also suggested uterine preservation in transvaginal mesh reconstruction for prolapse, based on four RCTs and nine comparison studies with 1,381 women and up to 30 months’ follow-up. The studies found a decreased risk of mesh erosion, reoperating for mesh erosion, blood loss, and postop bleeding, and improved posterior and apical Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification scores when women keep their uterus.

However, “the patient should be counseled that there may be increased de novo stress incontinence, overactive bladder,” postop constipation, and shorter vaginal length, Dr. Meriwether said.

Also, “we suggest preservation of the uterus in transvaginal apical native tissue repair of prolapse, as it does not worsen any outcomes and slightly reduces OR time and estimated blood loss,” based on 13 studies, including four RCTs, and a total of 1,449 women followed for up to 26 months, she said.

The Review Group also came out in favor of the Manchester procedure, when available, over vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue suspension, based on one RCT and five nonrandomized studies involving 1,126 women and up to 61 months’ follow-up. The Manchester procedure pushed back the time to prolapse reoperation 9 months in one study, and also decreased transfusions, OR time, and blood loss. It also better preserved perineal length.

The group suggested uterine preservation when considering mesh sacrocolpopexy versus mesh sacrohysteropexy, to reduce mesh erosion, OR time, blood loss, hospital stay, and surgery costs, although there might be a slight worsening of Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact scores. The advice was based on nine nonrandomized comparison studies involving 745 women followed for up to 39 months. There was no difference in prolapse resolution between the two techniques.

The one grade A recommendation, for vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, was based on two RCTs with 182 women followed for up to 12 months.

Hysterectomy in those studies significantly reduced the risk of repeat surgery for prolapse and urinary symptoms, shortened OR time, and improved quality of life scores. However, the benefits came at the cost of slightly shorter vaginal length, worse Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification point C scores, greater blood loss, and up to a day longer spent in the hospital.

Dr. Meriwether reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

*Correction, 6/8/2017: An earlier version of this story misstated the status of the Systematic Review Group's recommendations. The recommendations have not been approved as official SGS guidelines. Also, the meeting sponsor information was updated.

SAN ANTONIO – The Systematic Review Group of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons is suggesting uterine preservation, when not contraindicated, for most pelvic organ prolapse repairs to decrease mesh erosion, operating room time, and blood loss.

The advice is based on a review of 94 original studies, including 12 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 41 nonrandomized comparative studies, winnowed down to the strongest work from an original review of 7,324 abstracts through January 2017.

Short-term prolapse outcomes – 12-30 months in most of the studies – “are usually not clinically significant due to uterine preservation,” with the one exception of vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction, which the group recommended over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, Kate Meriwether, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the University of Louisville, Ky., said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Hysterectomy for prolapse surgery is common: More than 74,000 hysterectomies are done in the United States each year with prolapse as the main indication. Even so, it’s not always necessary to take out the uterus, and perhaps more than a third of women would prefer to keep theirs, Dr. Meriwether said, speaking on behalf of the SGS Systematic Review Group.

The recommendations from the Systematic Review Group must be sent to the SGS board and the full membership before they can be approved as guidelines.*

The Review Group made a grade A recommendation for vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, meaning it was based on high-quality evidence. The rest of the advice came in the form of suggestions, based on moderate grade B evidence, often nonrandomized comparative studies and case reviews.

The Review Group suggested uterine preservation during laparoscopic native tissue prolapse repair to reduce operating room (OR) time and blood loss, and preserve vaginal length, based on four nonrandomized comparison studies using various approaches, with a total of 446 women and up to 3 years’ follow-up. There might be a higher risk of apical recurrence without hysterectomy, but without worsening of prolapse symptoms.

The Review Group also suggested uterine preservation in transvaginal mesh reconstruction for prolapse, based on four RCTs and nine comparison studies with 1,381 women and up to 30 months’ follow-up. The studies found a decreased risk of mesh erosion, reoperating for mesh erosion, blood loss, and postop bleeding, and improved posterior and apical Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification scores when women keep their uterus.

However, “the patient should be counseled that there may be increased de novo stress incontinence, overactive bladder,” postop constipation, and shorter vaginal length, Dr. Meriwether said.

Also, “we suggest preservation of the uterus in transvaginal apical native tissue repair of prolapse, as it does not worsen any outcomes and slightly reduces OR time and estimated blood loss,” based on 13 studies, including four RCTs, and a total of 1,449 women followed for up to 26 months, she said.

The Review Group also came out in favor of the Manchester procedure, when available, over vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue suspension, based on one RCT and five nonrandomized studies involving 1,126 women and up to 61 months’ follow-up. The Manchester procedure pushed back the time to prolapse reoperation 9 months in one study, and also decreased transfusions, OR time, and blood loss. It also better preserved perineal length.

The group suggested uterine preservation when considering mesh sacrocolpopexy versus mesh sacrohysteropexy, to reduce mesh erosion, OR time, blood loss, hospital stay, and surgery costs, although there might be a slight worsening of Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact scores. The advice was based on nine nonrandomized comparison studies involving 745 women followed for up to 39 months. There was no difference in prolapse resolution between the two techniques.

The one grade A recommendation, for vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, was based on two RCTs with 182 women followed for up to 12 months.

Hysterectomy in those studies significantly reduced the risk of repeat surgery for prolapse and urinary symptoms, shortened OR time, and improved quality of life scores. However, the benefits came at the cost of slightly shorter vaginal length, worse Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification point C scores, greater blood loss, and up to a day longer spent in the hospital.

Dr. Meriwether reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

*Correction, 6/8/2017: An earlier version of this story misstated the status of the Systematic Review Group's recommendations. The recommendations have not been approved as official SGS guidelines. Also, the meeting sponsor information was updated.

SAN ANTONIO – The Systematic Review Group of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons is suggesting uterine preservation, when not contraindicated, for most pelvic organ prolapse repairs to decrease mesh erosion, operating room time, and blood loss.

The advice is based on a review of 94 original studies, including 12 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 41 nonrandomized comparative studies, winnowed down to the strongest work from an original review of 7,324 abstracts through January 2017.

Short-term prolapse outcomes – 12-30 months in most of the studies – “are usually not clinically significant due to uterine preservation,” with the one exception of vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction, which the group recommended over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, Kate Meriwether, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the University of Louisville, Ky., said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Hysterectomy for prolapse surgery is common: More than 74,000 hysterectomies are done in the United States each year with prolapse as the main indication. Even so, it’s not always necessary to take out the uterus, and perhaps more than a third of women would prefer to keep theirs, Dr. Meriwether said, speaking on behalf of the SGS Systematic Review Group.

The recommendations from the Systematic Review Group must be sent to the SGS board and the full membership before they can be approved as guidelines.*

The Review Group made a grade A recommendation for vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, meaning it was based on high-quality evidence. The rest of the advice came in the form of suggestions, based on moderate grade B evidence, often nonrandomized comparative studies and case reviews.

The Review Group suggested uterine preservation during laparoscopic native tissue prolapse repair to reduce operating room (OR) time and blood loss, and preserve vaginal length, based on four nonrandomized comparison studies using various approaches, with a total of 446 women and up to 3 years’ follow-up. There might be a higher risk of apical recurrence without hysterectomy, but without worsening of prolapse symptoms.

The Review Group also suggested uterine preservation in transvaginal mesh reconstruction for prolapse, based on four RCTs and nine comparison studies with 1,381 women and up to 30 months’ follow-up. The studies found a decreased risk of mesh erosion, reoperating for mesh erosion, blood loss, and postop bleeding, and improved posterior and apical Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification scores when women keep their uterus.

However, “the patient should be counseled that there may be increased de novo stress incontinence, overactive bladder,” postop constipation, and shorter vaginal length, Dr. Meriwether said.

Also, “we suggest preservation of the uterus in transvaginal apical native tissue repair of prolapse, as it does not worsen any outcomes and slightly reduces OR time and estimated blood loss,” based on 13 studies, including four RCTs, and a total of 1,449 women followed for up to 26 months, she said.

The Review Group also came out in favor of the Manchester procedure, when available, over vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue suspension, based on one RCT and five nonrandomized studies involving 1,126 women and up to 61 months’ follow-up. The Manchester procedure pushed back the time to prolapse reoperation 9 months in one study, and also decreased transfusions, OR time, and blood loss. It also better preserved perineal length.

The group suggested uterine preservation when considering mesh sacrocolpopexy versus mesh sacrohysteropexy, to reduce mesh erosion, OR time, blood loss, hospital stay, and surgery costs, although there might be a slight worsening of Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact scores. The advice was based on nine nonrandomized comparison studies involving 745 women followed for up to 39 months. There was no difference in prolapse resolution between the two techniques.

The one grade A recommendation, for vaginal hysterectomy with native tissue reconstruction over laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, was based on two RCTs with 182 women followed for up to 12 months.

Hysterectomy in those studies significantly reduced the risk of repeat surgery for prolapse and urinary symptoms, shortened OR time, and improved quality of life scores. However, the benefits came at the cost of slightly shorter vaginal length, worse Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification point C scores, greater blood loss, and up to a day longer spent in the hospital.

Dr. Meriwether reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

*Correction, 6/8/2017: An earlier version of this story misstated the status of the Systematic Review Group's recommendations. The recommendations have not been approved as official SGS guidelines. Also, the meeting sponsor information was updated.

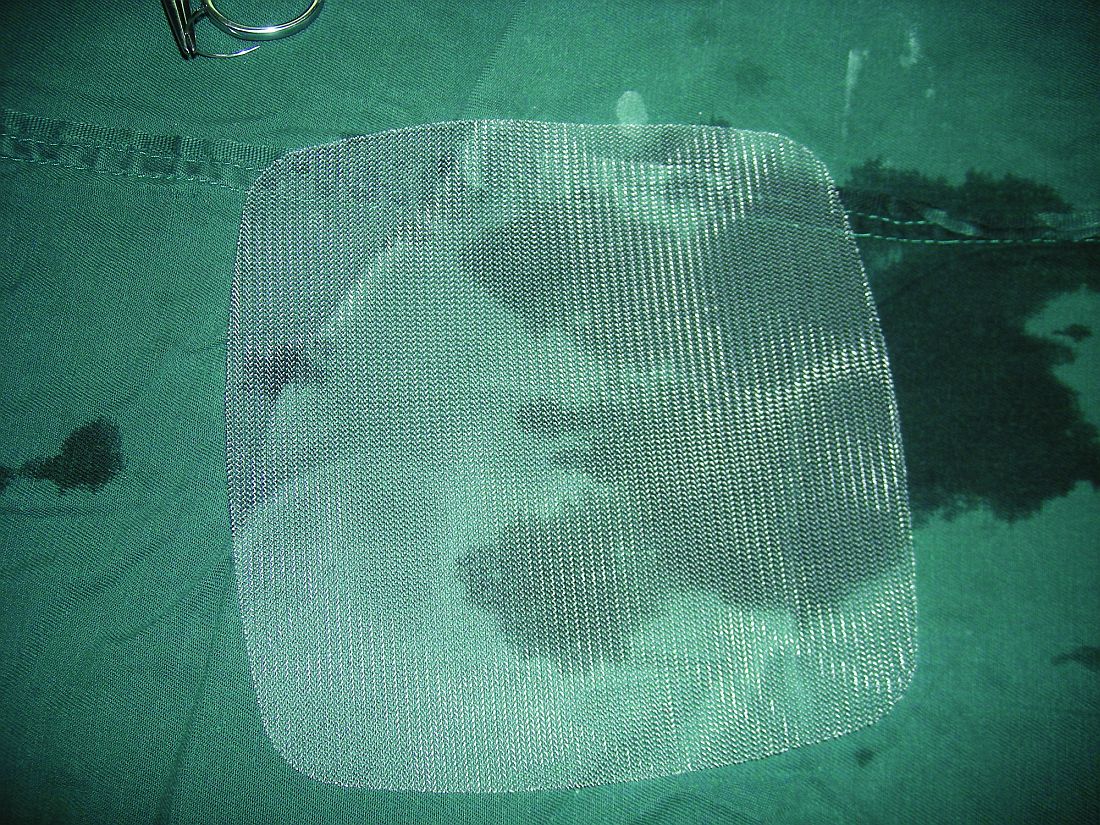

Lightweight mesh reduces erosion risk after sacrocolpopexy

SAN ANTONIO – Compared with heavier mesh types, ultralightweight polypropylene (Restorelle Y) did not increase the risk of mesh erosion after sacrocolpopexy in a retrospective, case-control study.

Delayed–absorbable monofilament polydioxanone suture (PDS) also decreased the risk, compared with nonabsorbable braided suture (Ethibond Excel) for vaginal mesh attachment.

The odds ratio for the ultralightweight polypropylene mesh exposure, versus heavier mesh, was not statistically significant (odds ratio, 2.18; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-14.57), which led to the main study conclusion.

“Mesh choice and suture selection [are] important independent predictors of” erosion, she said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. “Based on this study, surgeons should consider use of [PDS over nonabsorbable braided suture] to reduce the risk of mesh exposure when using ultralightweight mesh.”

The team also found that prior surgery for incontinence, as well as immediate postoperative complications, which likely impede healing, increase erosion risk. The findings are useful in counseling patients and perhaps guiding follow-up, at least early on. Most of the 133 erosions in the study – out of 1,247 sacrocolpopexies performed at the university from 2003 to2013 – occurred in the first year, usually in the first 3 months.

The 133 women with erosions were randomly matched with 261 women who did not have erosions after sacrocolpopexy. The erosion rate hovered around 9.5% for most years. They shot up to 19% in 2006, the first year of robot-assisted sacrocolpopexies and fell to about 6% in 2011, 4% in 2012, and 2% in 2013, when surgeons started using the ultralightweight mesh.

“Our study also confirmed several known risk factors,” Dr. Durst said, including smoking, stage IV prolapse, nonabsorbable braided suture, and heavyweight polypropylene mesh.

On multivariate regression, prior surgery for incontinence (OR, 2.87; 95% CI, 1.19-6.96), porcine acellular collagen matrix with soft polypropylene mesh (Pelvicol with soft Prolene, OR, 4.95; 95% CI, 1.70-14.42), other polypropylene mesh (OR, 6.73; 95% CI, 1.12-40.63); braided suture for vaginal mesh attachment (OR, 4.52; 95% CI, 1.53-13.37), and immediate perioperative complications (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.58-8.43) all remained independent risk factors for mesh exposure, as did duration of follow-up (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.03-1.06).

There was no industry funding for the study, and the investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – Compared with heavier mesh types, ultralightweight polypropylene (Restorelle Y) did not increase the risk of mesh erosion after sacrocolpopexy in a retrospective, case-control study.

Delayed–absorbable monofilament polydioxanone suture (PDS) also decreased the risk, compared with nonabsorbable braided suture (Ethibond Excel) for vaginal mesh attachment.

The odds ratio for the ultralightweight polypropylene mesh exposure, versus heavier mesh, was not statistically significant (odds ratio, 2.18; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-14.57), which led to the main study conclusion.

“Mesh choice and suture selection [are] important independent predictors of” erosion, she said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. “Based on this study, surgeons should consider use of [PDS over nonabsorbable braided suture] to reduce the risk of mesh exposure when using ultralightweight mesh.”

The team also found that prior surgery for incontinence, as well as immediate postoperative complications, which likely impede healing, increase erosion risk. The findings are useful in counseling patients and perhaps guiding follow-up, at least early on. Most of the 133 erosions in the study – out of 1,247 sacrocolpopexies performed at the university from 2003 to2013 – occurred in the first year, usually in the first 3 months.

The 133 women with erosions were randomly matched with 261 women who did not have erosions after sacrocolpopexy. The erosion rate hovered around 9.5% for most years. They shot up to 19% in 2006, the first year of robot-assisted sacrocolpopexies and fell to about 6% in 2011, 4% in 2012, and 2% in 2013, when surgeons started using the ultralightweight mesh.

“Our study also confirmed several known risk factors,” Dr. Durst said, including smoking, stage IV prolapse, nonabsorbable braided suture, and heavyweight polypropylene mesh.

On multivariate regression, prior surgery for incontinence (OR, 2.87; 95% CI, 1.19-6.96), porcine acellular collagen matrix with soft polypropylene mesh (Pelvicol with soft Prolene, OR, 4.95; 95% CI, 1.70-14.42), other polypropylene mesh (OR, 6.73; 95% CI, 1.12-40.63); braided suture for vaginal mesh attachment (OR, 4.52; 95% CI, 1.53-13.37), and immediate perioperative complications (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.58-8.43) all remained independent risk factors for mesh exposure, as did duration of follow-up (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.03-1.06).

There was no industry funding for the study, and the investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – Compared with heavier mesh types, ultralightweight polypropylene (Restorelle Y) did not increase the risk of mesh erosion after sacrocolpopexy in a retrospective, case-control study.

Delayed–absorbable monofilament polydioxanone suture (PDS) also decreased the risk, compared with nonabsorbable braided suture (Ethibond Excel) for vaginal mesh attachment.

The odds ratio for the ultralightweight polypropylene mesh exposure, versus heavier mesh, was not statistically significant (odds ratio, 2.18; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-14.57), which led to the main study conclusion.

“Mesh choice and suture selection [are] important independent predictors of” erosion, she said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. “Based on this study, surgeons should consider use of [PDS over nonabsorbable braided suture] to reduce the risk of mesh exposure when using ultralightweight mesh.”

The team also found that prior surgery for incontinence, as well as immediate postoperative complications, which likely impede healing, increase erosion risk. The findings are useful in counseling patients and perhaps guiding follow-up, at least early on. Most of the 133 erosions in the study – out of 1,247 sacrocolpopexies performed at the university from 2003 to2013 – occurred in the first year, usually in the first 3 months.

The 133 women with erosions were randomly matched with 261 women who did not have erosions after sacrocolpopexy. The erosion rate hovered around 9.5% for most years. They shot up to 19% in 2006, the first year of robot-assisted sacrocolpopexies and fell to about 6% in 2011, 4% in 2012, and 2% in 2013, when surgeons started using the ultralightweight mesh.

“Our study also confirmed several known risk factors,” Dr. Durst said, including smoking, stage IV prolapse, nonabsorbable braided suture, and heavyweight polypropylene mesh.

On multivariate regression, prior surgery for incontinence (OR, 2.87; 95% CI, 1.19-6.96), porcine acellular collagen matrix with soft polypropylene mesh (Pelvicol with soft Prolene, OR, 4.95; 95% CI, 1.70-14.42), other polypropylene mesh (OR, 6.73; 95% CI, 1.12-40.63); braided suture for vaginal mesh attachment (OR, 4.52; 95% CI, 1.53-13.37), and immediate perioperative complications (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.58-8.43) all remained independent risk factors for mesh exposure, as did duration of follow-up (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.03-1.06).

There was no industry funding for the study, and the investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

AT SGS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The odds ratio for ultralightweight polypropylene (Restorelle Y) exposure, versus heavier polypropylene mesh, was not statistically significant (OR, 2.18; 95% CI, 0.33-14.57).

Data source: A single-center study matching 133 erosion cases to 261 controls.

Disclosures: There was no industry funding of the study, and the investigators reported no financial disclosures.

Predicting extraction of an intact uterus in robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy

SAN ANTONIO – Investigators at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, have come up with a simple scoring system to predict if an intact uterus can be delivered vaginally during laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Age greater than 50 years counts as 1 point and uterine length greater than 11 cm, height greater than 8 cm, and width greater than 6.9 cm each count for 3 points. A score of 4 or higher suggests the need for an alternative to vaginal extraction, they reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

The team reviewed 367 robotic-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomies. An intact uterus was able to be extracted vaginally in 265 cases (72%); minilaparotomy was used for the rest. Uterine length, height, and width were documented from pathology reports. The scoring system correctly classified 94.6% of the cases. Sensitivity was 85.3%, specificity was 98.1%, positive predictive value was 94.57%, and negative predictive value was 94.55%.

Factoring in parity, uterine weight, body mass index, procedure indications, tobacco use, and comorbidities did not statistically influence the predictive power.

Gynecologic surgeons “are trying to get specimens out intact” and want to know ahead of time if it’s possible, Dr. Mohling said. “I wanted to create a model that was very reproducible.”

The general benchmark for vaginal delivery of an intact uterus is size below 12 weeks pregnancy, but the University of Tennessee model is more precise, according to Dr. Mohling. “I’ve added this to my counseling,” she said.

There was no external funding for the work and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – Investigators at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, have come up with a simple scoring system to predict if an intact uterus can be delivered vaginally during laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Age greater than 50 years counts as 1 point and uterine length greater than 11 cm, height greater than 8 cm, and width greater than 6.9 cm each count for 3 points. A score of 4 or higher suggests the need for an alternative to vaginal extraction, they reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

The team reviewed 367 robotic-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomies. An intact uterus was able to be extracted vaginally in 265 cases (72%); minilaparotomy was used for the rest. Uterine length, height, and width were documented from pathology reports. The scoring system correctly classified 94.6% of the cases. Sensitivity was 85.3%, specificity was 98.1%, positive predictive value was 94.57%, and negative predictive value was 94.55%.

Factoring in parity, uterine weight, body mass index, procedure indications, tobacco use, and comorbidities did not statistically influence the predictive power.

Gynecologic surgeons “are trying to get specimens out intact” and want to know ahead of time if it’s possible, Dr. Mohling said. “I wanted to create a model that was very reproducible.”

The general benchmark for vaginal delivery of an intact uterus is size below 12 weeks pregnancy, but the University of Tennessee model is more precise, according to Dr. Mohling. “I’ve added this to my counseling,” she said.

There was no external funding for the work and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – Investigators at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, have come up with a simple scoring system to predict if an intact uterus can be delivered vaginally during laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Age greater than 50 years counts as 1 point and uterine length greater than 11 cm, height greater than 8 cm, and width greater than 6.9 cm each count for 3 points. A score of 4 or higher suggests the need for an alternative to vaginal extraction, they reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

The team reviewed 367 robotic-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomies. An intact uterus was able to be extracted vaginally in 265 cases (72%); minilaparotomy was used for the rest. Uterine length, height, and width were documented from pathology reports. The scoring system correctly classified 94.6% of the cases. Sensitivity was 85.3%, specificity was 98.1%, positive predictive value was 94.57%, and negative predictive value was 94.55%.

Factoring in parity, uterine weight, body mass index, procedure indications, tobacco use, and comorbidities did not statistically influence the predictive power.

Gynecologic surgeons “are trying to get specimens out intact” and want to know ahead of time if it’s possible, Dr. Mohling said. “I wanted to create a model that was very reproducible.”

The general benchmark for vaginal delivery of an intact uterus is size below 12 weeks pregnancy, but the University of Tennessee model is more precise, according to Dr. Mohling. “I’ve added this to my counseling,” she said.

There was no external funding for the work and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

AT SGS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The sensitivity of the scoring system was 85.3%, specificity was 98.1%, positive predictive value was 94.57%, and negative predictive value was 94.55%.

Data source: Single-center review of 367 robotic total laparoscopic hysterectomies during 2012-2015.

Disclosures: There was no external funding for the work, and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Confirmatory blood typing unnecessary for closed prolapse repairs

SAN ANTONIO – It was safe to skip preoperative blood type and antibody screening before vaginal and robotic apical prolapse surgeries at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, so long as the women didn’t have hemorrhage risk factors.

The rate of blood transfusions was 0.5% for both the 204 women who had vaginal repairs and the 203 women who underwent robotic repairs; the rate of positive antibody tests was 1.6%. Given the 0.4% risk of transfusion reactions in unscreened women, the investigators calculated that the risk of serious transfusion reactions was 1 in 50,000 with closed vaginal prolapse repairs.

“The bottom line for us is that the risk in this situation is very low, even if preop type and screens are not performed, and women hemorrhage. This information provides insight to answer our key clinical question, which was if we should continue to order preop type and screens,” lead investigator Taylor Brueseke, MD, an ob.gyn. fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

That question has been on the minds of gynecologic surgeons, and it’s probably never been parsed out before by route of surgery. The American College of Pathologists recommends two blood type and antibody screens from separate venipunctures before surgery. Often, the second, confirmatory test means that women have to come in even earlier on the morning of surgery and deal with another painful blood draw. It also adds a few hundred dollars to the bill.

Every surgeon needs to draw their own line between risks and benefits, Dr. Brueseke said, but it seems reasonable in many cases to skip the second screening for closed repairs. Even if a woman has a transfusion reaction, “it doesn’t mean that the patient is going to die. It’s something that you can deal with,” he said.

However, the team reached a different conclusion for women who undergo open abdominal repairs. Among the 201 cases they reviewed, 10.5% had a transfusion, which translated to a transfusion reaction risk of 1 in 2,645 for unscreened women undergoing open apical prolapse surgery. The higher hemorrhage rate was probably due to concomitant Burch procedures and other open incontinence operations.

For abdominal cases, and for women who have had prior transfusions, surgeries, or anticoagulation, “consider type and screen,” Dr. Brueseke said at the meeting.

In a separate study presented at the conference, more than 50,000 pelvic floor disorder surgeries in the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program database further defined the hemorrhage risk.

Investigators at Ohio State University, Columbus, found that the overall incidence of blood transfusions was low at 1.26%, but open abdominal procedures again increased the risk. Other factors associated with an increased risk of blood transfusion included preoperative hematocrit less than 30%, an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status score of 3 or higher, concomitant hysterectomy, body mass index below 18.5 kg/m2, age less than 30 and over 65 years, and a history of bleeding disorders.

In the UNC study, the median Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification was stage III. Patients with bleeding disorders, anticoagulant use, or combined surgery with other services were excluded.

There was no industry funding for the two studies, and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

A lot of people automatically order type and screen for vaginal prolapse repairs, but we really need to rethink that if there aren’t risk factors that warrant it. I defer to the anesthesiologists because they are the ones who usually want this, but most of the time we screen but don’t use the results. There’s room to improve clinical practice here.

Robert Gutman, MD, is a gynecologic surgeon in Washington, D.C., and the program chair for the 2017 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons annual scientific meeting. He wasn’t involved in the studies presented.

A lot of people automatically order type and screen for vaginal prolapse repairs, but we really need to rethink that if there aren’t risk factors that warrant it. I defer to the anesthesiologists because they are the ones who usually want this, but most of the time we screen but don’t use the results. There’s room to improve clinical practice here.

Robert Gutman, MD, is a gynecologic surgeon in Washington, D.C., and the program chair for the 2017 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons annual scientific meeting. He wasn’t involved in the studies presented.

A lot of people automatically order type and screen for vaginal prolapse repairs, but we really need to rethink that if there aren’t risk factors that warrant it. I defer to the anesthesiologists because they are the ones who usually want this, but most of the time we screen but don’t use the results. There’s room to improve clinical practice here.

Robert Gutman, MD, is a gynecologic surgeon in Washington, D.C., and the program chair for the 2017 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons annual scientific meeting. He wasn’t involved in the studies presented.

SAN ANTONIO – It was safe to skip preoperative blood type and antibody screening before vaginal and robotic apical prolapse surgeries at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, so long as the women didn’t have hemorrhage risk factors.

The rate of blood transfusions was 0.5% for both the 204 women who had vaginal repairs and the 203 women who underwent robotic repairs; the rate of positive antibody tests was 1.6%. Given the 0.4% risk of transfusion reactions in unscreened women, the investigators calculated that the risk of serious transfusion reactions was 1 in 50,000 with closed vaginal prolapse repairs.

“The bottom line for us is that the risk in this situation is very low, even if preop type and screens are not performed, and women hemorrhage. This information provides insight to answer our key clinical question, which was if we should continue to order preop type and screens,” lead investigator Taylor Brueseke, MD, an ob.gyn. fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

That question has been on the minds of gynecologic surgeons, and it’s probably never been parsed out before by route of surgery. The American College of Pathologists recommends two blood type and antibody screens from separate venipunctures before surgery. Often, the second, confirmatory test means that women have to come in even earlier on the morning of surgery and deal with another painful blood draw. It also adds a few hundred dollars to the bill.

Every surgeon needs to draw their own line between risks and benefits, Dr. Brueseke said, but it seems reasonable in many cases to skip the second screening for closed repairs. Even if a woman has a transfusion reaction, “it doesn’t mean that the patient is going to die. It’s something that you can deal with,” he said.

However, the team reached a different conclusion for women who undergo open abdominal repairs. Among the 201 cases they reviewed, 10.5% had a transfusion, which translated to a transfusion reaction risk of 1 in 2,645 for unscreened women undergoing open apical prolapse surgery. The higher hemorrhage rate was probably due to concomitant Burch procedures and other open incontinence operations.

For abdominal cases, and for women who have had prior transfusions, surgeries, or anticoagulation, “consider type and screen,” Dr. Brueseke said at the meeting.

In a separate study presented at the conference, more than 50,000 pelvic floor disorder surgeries in the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program database further defined the hemorrhage risk.

Investigators at Ohio State University, Columbus, found that the overall incidence of blood transfusions was low at 1.26%, but open abdominal procedures again increased the risk. Other factors associated with an increased risk of blood transfusion included preoperative hematocrit less than 30%, an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status score of 3 or higher, concomitant hysterectomy, body mass index below 18.5 kg/m2, age less than 30 and over 65 years, and a history of bleeding disorders.

In the UNC study, the median Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification was stage III. Patients with bleeding disorders, anticoagulant use, or combined surgery with other services were excluded.

There was no industry funding for the two studies, and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – It was safe to skip preoperative blood type and antibody screening before vaginal and robotic apical prolapse surgeries at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, so long as the women didn’t have hemorrhage risk factors.

The rate of blood transfusions was 0.5% for both the 204 women who had vaginal repairs and the 203 women who underwent robotic repairs; the rate of positive antibody tests was 1.6%. Given the 0.4% risk of transfusion reactions in unscreened women, the investigators calculated that the risk of serious transfusion reactions was 1 in 50,000 with closed vaginal prolapse repairs.

“The bottom line for us is that the risk in this situation is very low, even if preop type and screens are not performed, and women hemorrhage. This information provides insight to answer our key clinical question, which was if we should continue to order preop type and screens,” lead investigator Taylor Brueseke, MD, an ob.gyn. fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

That question has been on the minds of gynecologic surgeons, and it’s probably never been parsed out before by route of surgery. The American College of Pathologists recommends two blood type and antibody screens from separate venipunctures before surgery. Often, the second, confirmatory test means that women have to come in even earlier on the morning of surgery and deal with another painful blood draw. It also adds a few hundred dollars to the bill.

Every surgeon needs to draw their own line between risks and benefits, Dr. Brueseke said, but it seems reasonable in many cases to skip the second screening for closed repairs. Even if a woman has a transfusion reaction, “it doesn’t mean that the patient is going to die. It’s something that you can deal with,” he said.

However, the team reached a different conclusion for women who undergo open abdominal repairs. Among the 201 cases they reviewed, 10.5% had a transfusion, which translated to a transfusion reaction risk of 1 in 2,645 for unscreened women undergoing open apical prolapse surgery. The higher hemorrhage rate was probably due to concomitant Burch procedures and other open incontinence operations.

For abdominal cases, and for women who have had prior transfusions, surgeries, or anticoagulation, “consider type and screen,” Dr. Brueseke said at the meeting.

In a separate study presented at the conference, more than 50,000 pelvic floor disorder surgeries in the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program database further defined the hemorrhage risk.

Investigators at Ohio State University, Columbus, found that the overall incidence of blood transfusions was low at 1.26%, but open abdominal procedures again increased the risk. Other factors associated with an increased risk of blood transfusion included preoperative hematocrit less than 30%, an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status score of 3 or higher, concomitant hysterectomy, body mass index below 18.5 kg/m2, age less than 30 and over 65 years, and a history of bleeding disorders.

In the UNC study, the median Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification was stage III. Patients with bleeding disorders, anticoagulant use, or combined surgery with other services were excluded.

There was no industry funding for the two studies, and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Given the 0.4% risk of transfusion reactions in unscreened women, the risk of serious transfusion reactions was 1 in 50,000 women with closed apical prolapse repairs.

Data source: A review of more than 600 cases of apical prolapse surgery at a single center.

Disclosures: There was no industry funding, and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Long-term durability low for nonmesh vaginal prolapse repair

SAN ANTONIO – At 5-year follow-up, outcomes were slightly better on most measures for transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension versus transvaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation for apical prolapse, but the differences were not statistically significant, according to the first randomized trial to compare the two techniques.

Quality of life improvements were durable, but the overall 5-year success rate – defined as the absence of descent of the vaginal apex more than one-third into the vagina; anterior or posterior vaginal wall descent beyond the hymen; bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms; and further treatment for prolapse – was 39% in the 109 women randomized to bilateral uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS) and 30% in the 109 women randomized to unilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation (SSLF).

But there was a notable finding in the study. If women failed to meet all the requirements for success at any one visit, they were classified as surgical failures. However, many who missed the mark at one visit met all the requirements for success on other visits, including their last follow-up.

“We don’t think as surgeons that a bulge comes and goes on a yearly basis, but people actually moved in and out of success and failure over time, and that’s new,” Dr. Jelovsek said. “We just don’t understand the dynamic variables of anatomic prolapse, because no one’s looked at it. The assumption of ‘once a failure, always a failure’ may underestimate success rates.”

Nonetheless, using that approach in the study, the investigators found that the anatomic success was 54% in the ULS and 38% in the SSLF groups at 5 years, and 37% of women in the ULS group reported bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms, versus 42% of women with SSLF. A total of 12% of women with ULS and 8% of women with SSLF had undergone POP retreatment at 5 years, either by pessary or secondary surgery but, again, the differences were not statistically significant.

Of the 145 anatomic failures in the study, 41% were stage 3 or 4.

Quality of life improvements, assessed annually by phone, “were maintained over 5 years despite progressive increases in surgical failure rates over time,” with about a 70-point improvement in the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory and similar gains in other measures in both groups, Dr. Jelovsek reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

There were no between-group differences in suture exposure (about 25% in both groups) or sling erosion (about 3%) at 5 years.

There was a difference in granulation tissue: 28.9% with ULS and 18.8% with SSLF (odds ratio with ULS, 1.9; 95% confidence interval 1-3.7). The majority of adverse events occurred within 2 years of surgery.

Early pelvic floor muscle training made no difference in outcomes for the women randomized to it.

The women in the study had stage 2-4 prolapse at baseline. In addition to vaginal suspension surgery, they had vaginal hysterectomies if there was uterine prolapse, and all the women had concomitant retropubic midurethral sling surgery for stress incontinence.

At 2 years, composite success rates were about 60% in both groups (JAMA. 2014 Mar 12;311[10]:1023-34).

The study didn’t identify risk factors for failure, but they would be helpful to know, Dr. Jelovsek said. High-risk women might benefit from a more durable mesh repair. For now at least, “most women say the risk” of pain and other serious mesh complications “completely outweighs the bulge symptoms,” he said.

The trial, an extension of OPTIMAL (Operations and Pelvic Muscle Training in the Management of Apical Support Loss), was conducted at nine U.S. centers in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Jelovsek reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – At 5-year follow-up, outcomes were slightly better on most measures for transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension versus transvaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation for apical prolapse, but the differences were not statistically significant, according to the first randomized trial to compare the two techniques.

Quality of life improvements were durable, but the overall 5-year success rate – defined as the absence of descent of the vaginal apex more than one-third into the vagina; anterior or posterior vaginal wall descent beyond the hymen; bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms; and further treatment for prolapse – was 39% in the 109 women randomized to bilateral uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS) and 30% in the 109 women randomized to unilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation (SSLF).

But there was a notable finding in the study. If women failed to meet all the requirements for success at any one visit, they were classified as surgical failures. However, many who missed the mark at one visit met all the requirements for success on other visits, including their last follow-up.

“We don’t think as surgeons that a bulge comes and goes on a yearly basis, but people actually moved in and out of success and failure over time, and that’s new,” Dr. Jelovsek said. “We just don’t understand the dynamic variables of anatomic prolapse, because no one’s looked at it. The assumption of ‘once a failure, always a failure’ may underestimate success rates.”

Nonetheless, using that approach in the study, the investigators found that the anatomic success was 54% in the ULS and 38% in the SSLF groups at 5 years, and 37% of women in the ULS group reported bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms, versus 42% of women with SSLF. A total of 12% of women with ULS and 8% of women with SSLF had undergone POP retreatment at 5 years, either by pessary or secondary surgery but, again, the differences were not statistically significant.

Of the 145 anatomic failures in the study, 41% were stage 3 or 4.

Quality of life improvements, assessed annually by phone, “were maintained over 5 years despite progressive increases in surgical failure rates over time,” with about a 70-point improvement in the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory and similar gains in other measures in both groups, Dr. Jelovsek reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

There were no between-group differences in suture exposure (about 25% in both groups) or sling erosion (about 3%) at 5 years.

There was a difference in granulation tissue: 28.9% with ULS and 18.8% with SSLF (odds ratio with ULS, 1.9; 95% confidence interval 1-3.7). The majority of adverse events occurred within 2 years of surgery.

Early pelvic floor muscle training made no difference in outcomes for the women randomized to it.

The women in the study had stage 2-4 prolapse at baseline. In addition to vaginal suspension surgery, they had vaginal hysterectomies if there was uterine prolapse, and all the women had concomitant retropubic midurethral sling surgery for stress incontinence.

At 2 years, composite success rates were about 60% in both groups (JAMA. 2014 Mar 12;311[10]:1023-34).

The study didn’t identify risk factors for failure, but they would be helpful to know, Dr. Jelovsek said. High-risk women might benefit from a more durable mesh repair. For now at least, “most women say the risk” of pain and other serious mesh complications “completely outweighs the bulge symptoms,” he said.

The trial, an extension of OPTIMAL (Operations and Pelvic Muscle Training in the Management of Apical Support Loss), was conducted at nine U.S. centers in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Jelovsek reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – At 5-year follow-up, outcomes were slightly better on most measures for transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension versus transvaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation for apical prolapse, but the differences were not statistically significant, according to the first randomized trial to compare the two techniques.

Quality of life improvements were durable, but the overall 5-year success rate – defined as the absence of descent of the vaginal apex more than one-third into the vagina; anterior or posterior vaginal wall descent beyond the hymen; bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms; and further treatment for prolapse – was 39% in the 109 women randomized to bilateral uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS) and 30% in the 109 women randomized to unilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation (SSLF).

But there was a notable finding in the study. If women failed to meet all the requirements for success at any one visit, they were classified as surgical failures. However, many who missed the mark at one visit met all the requirements for success on other visits, including their last follow-up.

“We don’t think as surgeons that a bulge comes and goes on a yearly basis, but people actually moved in and out of success and failure over time, and that’s new,” Dr. Jelovsek said. “We just don’t understand the dynamic variables of anatomic prolapse, because no one’s looked at it. The assumption of ‘once a failure, always a failure’ may underestimate success rates.”

Nonetheless, using that approach in the study, the investigators found that the anatomic success was 54% in the ULS and 38% in the SSLF groups at 5 years, and 37% of women in the ULS group reported bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms, versus 42% of women with SSLF. A total of 12% of women with ULS and 8% of women with SSLF had undergone POP retreatment at 5 years, either by pessary or secondary surgery but, again, the differences were not statistically significant.

Of the 145 anatomic failures in the study, 41% were stage 3 or 4.

Quality of life improvements, assessed annually by phone, “were maintained over 5 years despite progressive increases in surgical failure rates over time,” with about a 70-point improvement in the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory and similar gains in other measures in both groups, Dr. Jelovsek reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

There were no between-group differences in suture exposure (about 25% in both groups) or sling erosion (about 3%) at 5 years.

There was a difference in granulation tissue: 28.9% with ULS and 18.8% with SSLF (odds ratio with ULS, 1.9; 95% confidence interval 1-3.7). The majority of adverse events occurred within 2 years of surgery.

Early pelvic floor muscle training made no difference in outcomes for the women randomized to it.

The women in the study had stage 2-4 prolapse at baseline. In addition to vaginal suspension surgery, they had vaginal hysterectomies if there was uterine prolapse, and all the women had concomitant retropubic midurethral sling surgery for stress incontinence.

At 2 years, composite success rates were about 60% in both groups (JAMA. 2014 Mar 12;311[10]:1023-34).

The study didn’t identify risk factors for failure, but they would be helpful to know, Dr. Jelovsek said. High-risk women might benefit from a more durable mesh repair. For now at least, “most women say the risk” of pain and other serious mesh complications “completely outweighs the bulge symptoms,” he said.

The trial, an extension of OPTIMAL (Operations and Pelvic Muscle Training in the Management of Apical Support Loss), was conducted at nine U.S. centers in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Jelovsek reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The overall 5-year success rate was 39% in women randomized to bilateral uterosacral ligament suspension and 30% in women randomized to unilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation.

Data source: The first randomized trial to compare the two commonly used techniques was conducted among 218 women at nine U.S. centers in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network.

Disclosures: The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network is funded by the National Institutes of Health. The lead investigator reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Don’t shy away from vaginal salpingectomy

SAN ANTONIO – Surgeons at Houston Methodist Hospital reported a 75% success rate in removing both fallopian tubes during vaginal hysterectomy in a study presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Serous ovarian carcinoma is now thought to arise from the distal fallopian tube, and it’s estimated that salpingectomy prevents diagnosis of ovarian cancer in 1 in 225 women and death from ovarian cancer in 1 in 450 women. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that surgeons and patients “discuss the potential benefits of the removal of the fallopian tubes” during hysterectomy in women not having an oophorectomy.

The findings from the Houston team show that “it’s feasible in most cases, with very little risk,” said Danielle Antosh, MD, lead investigator and director of the Center for Restorative Pelvic Medicine at Houston Methodist Urogynecology Associates.

“People are doing laparoscopic hysterectomies or robotic hysterectomies” to get at the fallopian tubes, “but they shouldn’t be deterred from trying to remove the fallopian tubes vaginally,” Dr. Antosh said at the SGS 2017 meeting. When women are having a vaginal hysterectomy, “why not try to remove the fallopian tubes? It’s something I would definitely consider counseling your patients about.”

Dr. Antosh said that residents should be taught how to perform salpingectomy during vaginal hysterectomy. “I think it is definitely feasible for residents to do.” Technically, “it’s a lot easier than removing the ovaries” vaginally, she said.

The 70 women in the study were undergoing vaginal hysterectomies by attending physicians for benign reasons, mostly uterine prolapse, followed by heavy menstrual flow and fibroids. In total, 52 (75%) had successful concomitant bilateral vaginal salpingectomies, and 7 additional women had one tube removed. Success was more likely with increasing parity and a history of prolapse. Most of the failures were because the tubes were too high in the pelvis or there were adhesions from prior adnexal surgery. Even with prior adnexal surgery, however, the success rate was 50%.

Vaginal salpingectomy added a mean of 11 minutes to surgery and a mean of 5 mL blood loss. There were no complications reported from including salpingectomy with vaginal hysterectomy. The study wasn’t powered to detect an impact on menopause symptoms, but there was a decrease in menopause symptoms at 16 week follow-up in the salpingectomy group, perhaps related to less sexual dysfunction and urinary incontinence.

The mean age in the study was 51 years, and mean body mass index was 27 kg/m2. There were no malignancies found on tubal pathology.

Five women were transferred to an abdominal approach because of a large uterus or discovery of ovarian pathology. None were transferred for the purpose of salpingectomy.

There was no external funding for the study, and the investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.