User login

Abaloparatide significantly reduced fractures, increased BMD in women at high fracture risk

Postmenopausal women at high or very high risk of fracture gained significantly more bone mineral density and were significantly less likely to experience a fracture when taking abaloparatide for 18 months, according to new research presented at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

“The findings showed that abaloparatide was better than teriparatide in a number of parameters important in osteoporosis treatment, and similar in others, in high-risk and very-high-risk postmenopausal women with osteoporosis,” Bart Clarke, MD, a professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview. “Abaloparatide is safe and effective for use in high-risk or very-high-risk postmenopausal women,” as defined by the new American Association of Clinical Endocrinology/American College of Endocrinology osteoporosis guidelines.

Ricardo R. Correa, MD, of the department of endocrinology and director of diversity for graduate medical education at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, said that the study demonstrates that abaloparatide and teriparatide have a very similar effect with abaloparatide providing a slightly better absolute risk reduction in fracture. Dr. Correa was not involved in the research.

“What will drive my decision in what to prescribe will be the cost and insurance coverage,” Dr. Correa said. “At the Veterans Administration hospital, the option that we have is abaloparatide, so this is the option that we use.”

Among women at least 65 years old who have already had one fracture, 1 in 10 will experience another fracture within the next year, and 30% will have another fracture within the next 5 years, the authors noted in their background material. Since phase 3 ACTIVE study data in 2016 showed that abaloparatide reduces fracture risk while increasing bone mineral density, compared with placebo, the researchers reanalyzed that data to assess the drug’s efficacy in patients at high or very high risk for fracture.

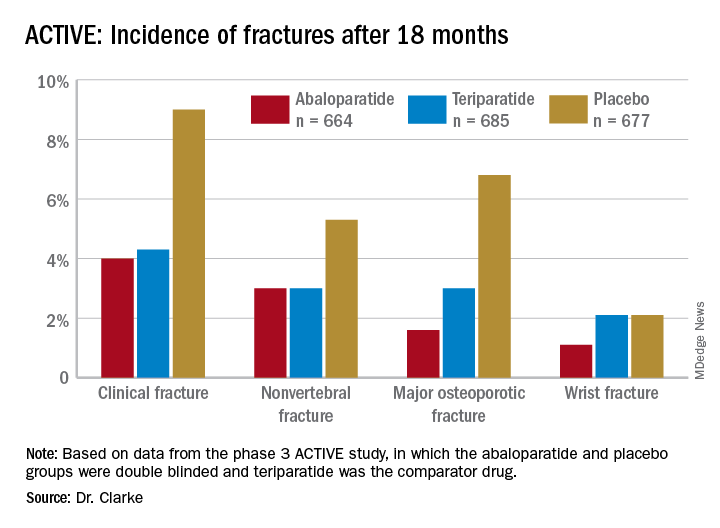

The study involved 2,463 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who received one of three interventions: 80 mcg abaloparatide daily, placebo, or 20 mcg subcutaneous teriparatide daily. Only the abaloparatide and placebo groups were double blinded.

“Teriparatide was used as the comparator drug because teriparatide was previously approved as the first anabolic drug for osteoporosis,” Dr. Clarke said in an interview. “The hope was to show that abaloparatide was a better anabolic drug.”

Women were considered at high or very high risk of fracture if they met at least one of the following four criteria from the 2020 American Association of Clinical Endocrinology guidelines:

- Fracture within the past 12 months or prevalent vertebral fracture.

- Very low T-score (less than –3.0) at baseline at any site.

- Multiple fractures at baseline since age 45.

- Very high fracture risk based on the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) (at least 30% for major osteoporotic fracture or at least 4.5% for hip fracture).

Among the 2,026 patients who met at least one of these criteria, 664 received abaloparatide, 685 received teriparatide, and 677 received placebo. Both the abaloparatide and teriparatide significantly reduced new vertebral fracture risk, compared with placebo. In the abaloparatide group, 0.72% of women had a new vertebral fracture, compared with 0.99% in the teriparatide group and 4.77% in the placebo group (P < .0001).

Abaloparatide and teriparatide also led to significant increases in lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck bone mineral density, compared with placebo (P < .0001).

The study was limited by its duration of 18 months and the Food and Drug Administration’s restriction on using abaloparatide for more than 2 years because of the theoretical risk of increasing osteosarcoma, although that risk has never been demonstrated in humans, Dr. Correa said. ”We need more data with abaloparitide in more than 2 years,” he added.

In determining which medication clinicians should first prescribe to manage osteoporosis, Dr. Correa said practitioners should consider the type of osteoporosis women have, their preferences, and their labs on kidney function.

With mild to moderate osteoporosis, bisphosphonates will be the first option while denosumab will be preferred for moderate to severe osteoporosis. Teriparatide and abaloparitide are the first-line options for severe osteoporosis, he said.

“If the glomerular filtration rate is low, we cannot use bisphosphonate and we will have to limit our use to denosumab,” he said. Route and frequency of delivery plays a role in patient preferences.

“If the patient prefers an infusion once a year or a pill, then bisphosphonate,” he said, but “if the patient is fine with an injection every 6 months, then denosumab.” Patients who need and can do an injection every day can take abaloparitide or teriparatide.

Failure of previous treatments also guide clinical decisions, he added. ”If the patient has been on one medication and has a fracture or the bone mineral density decreases, then we need to switch to another medication, usually teriparatide or abaloparitide, to build new bone.”

Contraindications for abaloparatide include a high serum calcium before therapy or prior allergic reactions to components in abaloparatide, Dr. Clarke said. No new safety signals showed up in the data analysis.

The research was funded by Radius Health. Dr. Clarke is an advisory board member of Amgen, and another author consults and speaks for Amgen and is a Radius Health Advisory Board member. Two other authors are Radius Health employees who own stock in the company. Dr Correa has no disclosures.

Postmenopausal women at high or very high risk of fracture gained significantly more bone mineral density and were significantly less likely to experience a fracture when taking abaloparatide for 18 months, according to new research presented at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

“The findings showed that abaloparatide was better than teriparatide in a number of parameters important in osteoporosis treatment, and similar in others, in high-risk and very-high-risk postmenopausal women with osteoporosis,” Bart Clarke, MD, a professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview. “Abaloparatide is safe and effective for use in high-risk or very-high-risk postmenopausal women,” as defined by the new American Association of Clinical Endocrinology/American College of Endocrinology osteoporosis guidelines.

Ricardo R. Correa, MD, of the department of endocrinology and director of diversity for graduate medical education at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, said that the study demonstrates that abaloparatide and teriparatide have a very similar effect with abaloparatide providing a slightly better absolute risk reduction in fracture. Dr. Correa was not involved in the research.

“What will drive my decision in what to prescribe will be the cost and insurance coverage,” Dr. Correa said. “At the Veterans Administration hospital, the option that we have is abaloparatide, so this is the option that we use.”

Among women at least 65 years old who have already had one fracture, 1 in 10 will experience another fracture within the next year, and 30% will have another fracture within the next 5 years, the authors noted in their background material. Since phase 3 ACTIVE study data in 2016 showed that abaloparatide reduces fracture risk while increasing bone mineral density, compared with placebo, the researchers reanalyzed that data to assess the drug’s efficacy in patients at high or very high risk for fracture.

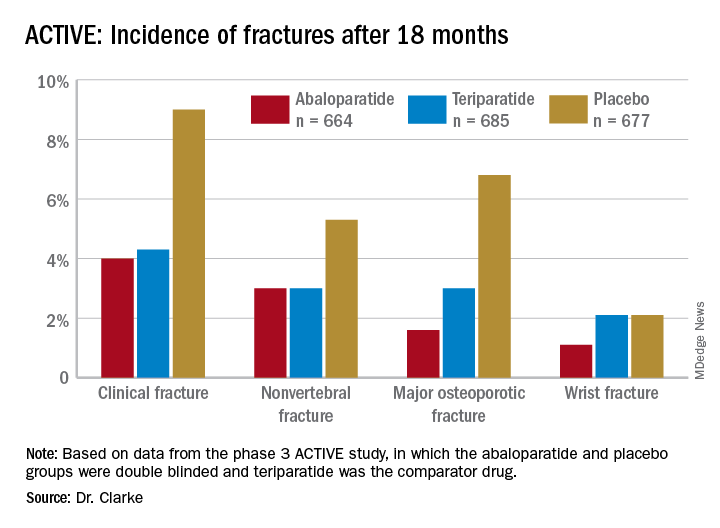

The study involved 2,463 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who received one of three interventions: 80 mcg abaloparatide daily, placebo, or 20 mcg subcutaneous teriparatide daily. Only the abaloparatide and placebo groups were double blinded.

“Teriparatide was used as the comparator drug because teriparatide was previously approved as the first anabolic drug for osteoporosis,” Dr. Clarke said in an interview. “The hope was to show that abaloparatide was a better anabolic drug.”

Women were considered at high or very high risk of fracture if they met at least one of the following four criteria from the 2020 American Association of Clinical Endocrinology guidelines:

- Fracture within the past 12 months or prevalent vertebral fracture.

- Very low T-score (less than –3.0) at baseline at any site.

- Multiple fractures at baseline since age 45.

- Very high fracture risk based on the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) (at least 30% for major osteoporotic fracture or at least 4.5% for hip fracture).

Among the 2,026 patients who met at least one of these criteria, 664 received abaloparatide, 685 received teriparatide, and 677 received placebo. Both the abaloparatide and teriparatide significantly reduced new vertebral fracture risk, compared with placebo. In the abaloparatide group, 0.72% of women had a new vertebral fracture, compared with 0.99% in the teriparatide group and 4.77% in the placebo group (P < .0001).

Abaloparatide and teriparatide also led to significant increases in lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck bone mineral density, compared with placebo (P < .0001).

The study was limited by its duration of 18 months and the Food and Drug Administration’s restriction on using abaloparatide for more than 2 years because of the theoretical risk of increasing osteosarcoma, although that risk has never been demonstrated in humans, Dr. Correa said. ”We need more data with abaloparitide in more than 2 years,” he added.

In determining which medication clinicians should first prescribe to manage osteoporosis, Dr. Correa said practitioners should consider the type of osteoporosis women have, their preferences, and their labs on kidney function.

With mild to moderate osteoporosis, bisphosphonates will be the first option while denosumab will be preferred for moderate to severe osteoporosis. Teriparatide and abaloparitide are the first-line options for severe osteoporosis, he said.

“If the glomerular filtration rate is low, we cannot use bisphosphonate and we will have to limit our use to denosumab,” he said. Route and frequency of delivery plays a role in patient preferences.

“If the patient prefers an infusion once a year or a pill, then bisphosphonate,” he said, but “if the patient is fine with an injection every 6 months, then denosumab.” Patients who need and can do an injection every day can take abaloparitide or teriparatide.

Failure of previous treatments also guide clinical decisions, he added. ”If the patient has been on one medication and has a fracture or the bone mineral density decreases, then we need to switch to another medication, usually teriparatide or abaloparitide, to build new bone.”

Contraindications for abaloparatide include a high serum calcium before therapy or prior allergic reactions to components in abaloparatide, Dr. Clarke said. No new safety signals showed up in the data analysis.

The research was funded by Radius Health. Dr. Clarke is an advisory board member of Amgen, and another author consults and speaks for Amgen and is a Radius Health Advisory Board member. Two other authors are Radius Health employees who own stock in the company. Dr Correa has no disclosures.

Postmenopausal women at high or very high risk of fracture gained significantly more bone mineral density and were significantly less likely to experience a fracture when taking abaloparatide for 18 months, according to new research presented at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

“The findings showed that abaloparatide was better than teriparatide in a number of parameters important in osteoporosis treatment, and similar in others, in high-risk and very-high-risk postmenopausal women with osteoporosis,” Bart Clarke, MD, a professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview. “Abaloparatide is safe and effective for use in high-risk or very-high-risk postmenopausal women,” as defined by the new American Association of Clinical Endocrinology/American College of Endocrinology osteoporosis guidelines.

Ricardo R. Correa, MD, of the department of endocrinology and director of diversity for graduate medical education at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, said that the study demonstrates that abaloparatide and teriparatide have a very similar effect with abaloparatide providing a slightly better absolute risk reduction in fracture. Dr. Correa was not involved in the research.

“What will drive my decision in what to prescribe will be the cost and insurance coverage,” Dr. Correa said. “At the Veterans Administration hospital, the option that we have is abaloparatide, so this is the option that we use.”

Among women at least 65 years old who have already had one fracture, 1 in 10 will experience another fracture within the next year, and 30% will have another fracture within the next 5 years, the authors noted in their background material. Since phase 3 ACTIVE study data in 2016 showed that abaloparatide reduces fracture risk while increasing bone mineral density, compared with placebo, the researchers reanalyzed that data to assess the drug’s efficacy in patients at high or very high risk for fracture.

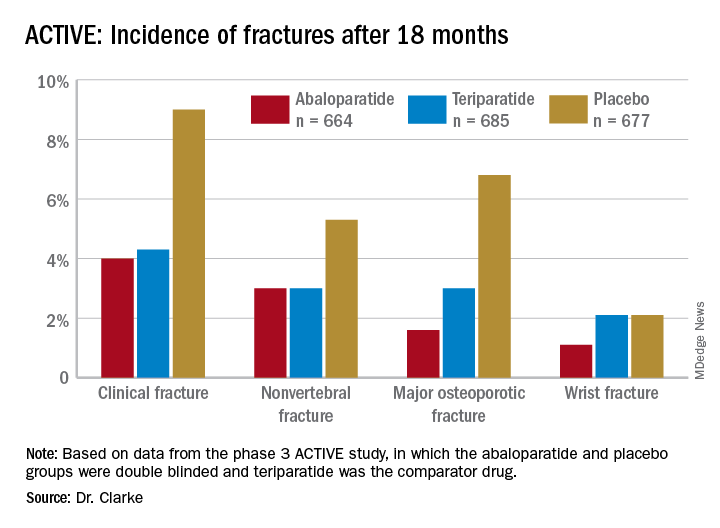

The study involved 2,463 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who received one of three interventions: 80 mcg abaloparatide daily, placebo, or 20 mcg subcutaneous teriparatide daily. Only the abaloparatide and placebo groups were double blinded.

“Teriparatide was used as the comparator drug because teriparatide was previously approved as the first anabolic drug for osteoporosis,” Dr. Clarke said in an interview. “The hope was to show that abaloparatide was a better anabolic drug.”

Women were considered at high or very high risk of fracture if they met at least one of the following four criteria from the 2020 American Association of Clinical Endocrinology guidelines:

- Fracture within the past 12 months or prevalent vertebral fracture.

- Very low T-score (less than –3.0) at baseline at any site.

- Multiple fractures at baseline since age 45.

- Very high fracture risk based on the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) (at least 30% for major osteoporotic fracture or at least 4.5% for hip fracture).

Among the 2,026 patients who met at least one of these criteria, 664 received abaloparatide, 685 received teriparatide, and 677 received placebo. Both the abaloparatide and teriparatide significantly reduced new vertebral fracture risk, compared with placebo. In the abaloparatide group, 0.72% of women had a new vertebral fracture, compared with 0.99% in the teriparatide group and 4.77% in the placebo group (P < .0001).

Abaloparatide and teriparatide also led to significant increases in lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck bone mineral density, compared with placebo (P < .0001).

The study was limited by its duration of 18 months and the Food and Drug Administration’s restriction on using abaloparatide for more than 2 years because of the theoretical risk of increasing osteosarcoma, although that risk has never been demonstrated in humans, Dr. Correa said. ”We need more data with abaloparitide in more than 2 years,” he added.

In determining which medication clinicians should first prescribe to manage osteoporosis, Dr. Correa said practitioners should consider the type of osteoporosis women have, their preferences, and their labs on kidney function.

With mild to moderate osteoporosis, bisphosphonates will be the first option while denosumab will be preferred for moderate to severe osteoporosis. Teriparatide and abaloparitide are the first-line options for severe osteoporosis, he said.

“If the glomerular filtration rate is low, we cannot use bisphosphonate and we will have to limit our use to denosumab,” he said. Route and frequency of delivery plays a role in patient preferences.

“If the patient prefers an infusion once a year or a pill, then bisphosphonate,” he said, but “if the patient is fine with an injection every 6 months, then denosumab.” Patients who need and can do an injection every day can take abaloparitide or teriparatide.

Failure of previous treatments also guide clinical decisions, he added. ”If the patient has been on one medication and has a fracture or the bone mineral density decreases, then we need to switch to another medication, usually teriparatide or abaloparitide, to build new bone.”

Contraindications for abaloparatide include a high serum calcium before therapy or prior allergic reactions to components in abaloparatide, Dr. Clarke said. No new safety signals showed up in the data analysis.

The research was funded by Radius Health. Dr. Clarke is an advisory board member of Amgen, and another author consults and speaks for Amgen and is a Radius Health Advisory Board member. Two other authors are Radius Health employees who own stock in the company. Dr Correa has no disclosures.

FROM NAMS 2021

New nonhormonal therapies for hot flashes on the horizon

Hot flashes affect three out of four women and can last 7-10 years, but the current standard of care treatment isn’t necessarily appropriate for all women who experience vasomotor symptoms, according to Stephanie Faubion, MD, MBA, director of the Mayo Clinic Women’s Health Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

For the majority of women under age 60 who are within 10 years of menopause, hormone therapy currently remains the most effective management option for hot flashes where the benefits outweigh the risks, Dr. Faubion told attendees Sept. 25 during a plenary at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. “But really, individualizing treatment is the goal, and there are some women who are going to need some other options.”

Contraindications for hormone therapy include having a history of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, active liver disease, unexplained vaginal bleeding, high-risk endometrial cancer, transient ischemic attack, and a previous venous thromboembolic event or stroke.

“Fortunately, we have things in development,” Dr. Faubion said. She reviewed a wide range of therapies that are not currently Food and Drug Administration approved for vasomotor symptoms but are either available off label or are in clinical trials.

One of these is oxybutynin, an antimuscarinic, anticholinergic agent currently used to treat overactive bladder and overactive sweating. In a 2016 trial, 73% of women taking 15 mg extended-release oxybutynin once daily rated their symptoms as “much better,” compared with 26% who received placebo. The women experienced reduced frequency and severity of hot flashes and better sleep.

Subsequent research found a 60% reduction in hot flash frequency with 2.5 mg twice a day and a 77% reduction with 5 mg twice a day, compared with a 27% reduction with placebo. The only reported side effect that occurred more often with oxybutynin was dry mouth, but there were no significant differences in reasons for discontinuation between the treatment and placebo groups.

There are, however, some potential long-term cognitive effects from oxybutynin, Dr. Faubion said. Some research has shown an increased risk of dementia from oxybutynin and from an overall higher cumulative use of anticholinergics.

“There’s some concern about that for long-term use,” she said, but it’s effective, it’s “probably not harmful [when] used short term in women with significant, bothersome hot flashes who are unwilling or unable to use hormone therapy, and the adverse effects are tolerable for most women.” Women with bladder symptoms would be especially ideal candidates since the drug already treats those.

Dr. Faubion then discussed a new estrogen called estetrol (E4), a naturally occurring estrogen with selection action in tissues that is produced by the fetal liver and crosses the placenta. It has a long half-life of 28-32 hours, and its potential mechanism may give it a different safety profile than estradiol (E2). “There may be a lower risk of drug-drug interactions; lower breast stimulation, pain or carcinogenic impact; lower impact on triglycerides; and a neutral impact on markers of coagulation,” she said.

Though estetrol was recently approved as an oral contraceptive under the name Estelle, it’s also under investigation as a postmenopausal regimen. Preliminary findings suggest it reduces vasomotor symptom severity by 44%, compared with 30% with placebo, at 15 mg, the apparent minimum effective dose. The safety profile showed no endometrial hyperplasia and no unexpected adverse events. In those taking 15 mg of estetrol, mean endometrial thickness increased from 2 to 6 mm but returned to baseline after progestin therapy.

“The 15-mg dose also positively influenced markers of bone turnover, increased HDL [cholesterol], improved glucose tolerance,” and had no effects on coagulation parameters or triglycerides, Dr. Faubion added.

Another group of potential agents being studied for hot flashes are NK3 antagonists, which aim to exploit the recent discovery that kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin (KNDy) neurons may play an important role in the etiology of vasomotor symptoms. Development of one of these, MLE 4901, was halted despite a 45% reduction in hot flashes because 3 of 28 women developed transiently elevated liver function tests, about four to six times the upper limit of normal.

Two others, fezolinetant and NT-814, are in phase 2 trials and have shown a significant reduction in symptoms, compared with placebo. The most commonly reported adverse effect in the phase 2a trial was gastrointestinal effects, but none of the participants stopped the drug because of these, and no elevated liver tests occurred. In the larger phase 2b trial, the most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events included nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, urinary tract infection, sinusitis, upper respiratory infection, headache, and cough. Five women discontinued the drug because of elevated liver enzymes.

“Overall, NK3 inhibitors appear to be generally well tolerated,” Dr. Faubion said. “There does seem to be mild transaminase elevation,” though it’s not yet known if this is an effect from this class of drugs as a whole. She noted that follicle-stimulating hormone does not significantly increase, which is important because elevated FSH is associated with poor bone health, nor does estradiol significantly increase, which is clinically relevant for women at high risk of breast cancer.

“We don’t know the effects on the heart, the brain, the bone, mood, weight, or sexual health, so there’s a lot that is still not known,” Dr. Faubion said. “We still don’t know about long-term safety and efficacy with these chemical compounds,” but clinical trials of them are ongoing.

They “would be a welcome alternative to hormone therapy for those who can’t or prefer not to use a hormonal option,” Dr. Faubion said. “However, we may need broad education of clinicians to caution against widespread abandonment of hormone therapy, particularly in women with premature or early menopause.”

Donna Klassen, LCSW, the cofounder of Let’s Talk Menopause, asked whether any of these new therapies were being tested in women with breast cancer and whether anything was known about taking oxybutynin at the same time as letrozole.

“I suspect that most women with chronic diseases would have been excluded from these initial studies, but I can’t speak to that,” Dr. Faubion said, and she wasn’t aware of any data related to taking oxybutynin and letrozole concurrently.

James Simon, MD, medical director and founder of IntimMedicine and one of those who led the research on oxybutynin, responded that his trials excluded breast cancer survivors and anyone taking aromatase inhibitors.

“It will be unlikely that, in the very near future, that data will be available because all the clinical developments on these NK3s or KNDy neuron-modulating drugs exclude cancer patients,” Dr. Simon said.

However, another attendee, Lisa Larkin, MD, of Cincinnati, introduced herself as a breast cancer survivor who takes tamoxifen and said she feels “completely comfortable” prescribing oxybutynin to breast cancer survivors.

“In terms of side effects and effectiveness in patients on tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors, I’ve had incredibly good luck with it, and I think it’s underutilized,” Dr. Larkin said. “The clinical pearl I would tell you is you can start really low, and the dry mouth really seems to improve with time.” She added that patients should be informed that it takes 2 weeks before it begins working, but the side effects eventually go away. “It becomes very tolerable, so I just encourage all of you to consider it as another great option.”

Dr. Faubion had no disclosures. Disclosure information was unavailable for Dr. Simon, Dr. Larkin, and Ms. Klassen.

Hot flashes affect three out of four women and can last 7-10 years, but the current standard of care treatment isn’t necessarily appropriate for all women who experience vasomotor symptoms, according to Stephanie Faubion, MD, MBA, director of the Mayo Clinic Women’s Health Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

For the majority of women under age 60 who are within 10 years of menopause, hormone therapy currently remains the most effective management option for hot flashes where the benefits outweigh the risks, Dr. Faubion told attendees Sept. 25 during a plenary at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. “But really, individualizing treatment is the goal, and there are some women who are going to need some other options.”

Contraindications for hormone therapy include having a history of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, active liver disease, unexplained vaginal bleeding, high-risk endometrial cancer, transient ischemic attack, and a previous venous thromboembolic event or stroke.

“Fortunately, we have things in development,” Dr. Faubion said. She reviewed a wide range of therapies that are not currently Food and Drug Administration approved for vasomotor symptoms but are either available off label or are in clinical trials.

One of these is oxybutynin, an antimuscarinic, anticholinergic agent currently used to treat overactive bladder and overactive sweating. In a 2016 trial, 73% of women taking 15 mg extended-release oxybutynin once daily rated their symptoms as “much better,” compared with 26% who received placebo. The women experienced reduced frequency and severity of hot flashes and better sleep.

Subsequent research found a 60% reduction in hot flash frequency with 2.5 mg twice a day and a 77% reduction with 5 mg twice a day, compared with a 27% reduction with placebo. The only reported side effect that occurred more often with oxybutynin was dry mouth, but there were no significant differences in reasons for discontinuation between the treatment and placebo groups.

There are, however, some potential long-term cognitive effects from oxybutynin, Dr. Faubion said. Some research has shown an increased risk of dementia from oxybutynin and from an overall higher cumulative use of anticholinergics.

“There’s some concern about that for long-term use,” she said, but it’s effective, it’s “probably not harmful [when] used short term in women with significant, bothersome hot flashes who are unwilling or unable to use hormone therapy, and the adverse effects are tolerable for most women.” Women with bladder symptoms would be especially ideal candidates since the drug already treats those.

Dr. Faubion then discussed a new estrogen called estetrol (E4), a naturally occurring estrogen with selection action in tissues that is produced by the fetal liver and crosses the placenta. It has a long half-life of 28-32 hours, and its potential mechanism may give it a different safety profile than estradiol (E2). “There may be a lower risk of drug-drug interactions; lower breast stimulation, pain or carcinogenic impact; lower impact on triglycerides; and a neutral impact on markers of coagulation,” she said.

Though estetrol was recently approved as an oral contraceptive under the name Estelle, it’s also under investigation as a postmenopausal regimen. Preliminary findings suggest it reduces vasomotor symptom severity by 44%, compared with 30% with placebo, at 15 mg, the apparent minimum effective dose. The safety profile showed no endometrial hyperplasia and no unexpected adverse events. In those taking 15 mg of estetrol, mean endometrial thickness increased from 2 to 6 mm but returned to baseline after progestin therapy.

“The 15-mg dose also positively influenced markers of bone turnover, increased HDL [cholesterol], improved glucose tolerance,” and had no effects on coagulation parameters or triglycerides, Dr. Faubion added.

Another group of potential agents being studied for hot flashes are NK3 antagonists, which aim to exploit the recent discovery that kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin (KNDy) neurons may play an important role in the etiology of vasomotor symptoms. Development of one of these, MLE 4901, was halted despite a 45% reduction in hot flashes because 3 of 28 women developed transiently elevated liver function tests, about four to six times the upper limit of normal.

Two others, fezolinetant and NT-814, are in phase 2 trials and have shown a significant reduction in symptoms, compared with placebo. The most commonly reported adverse effect in the phase 2a trial was gastrointestinal effects, but none of the participants stopped the drug because of these, and no elevated liver tests occurred. In the larger phase 2b trial, the most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events included nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, urinary tract infection, sinusitis, upper respiratory infection, headache, and cough. Five women discontinued the drug because of elevated liver enzymes.

“Overall, NK3 inhibitors appear to be generally well tolerated,” Dr. Faubion said. “There does seem to be mild transaminase elevation,” though it’s not yet known if this is an effect from this class of drugs as a whole. She noted that follicle-stimulating hormone does not significantly increase, which is important because elevated FSH is associated with poor bone health, nor does estradiol significantly increase, which is clinically relevant for women at high risk of breast cancer.

“We don’t know the effects on the heart, the brain, the bone, mood, weight, or sexual health, so there’s a lot that is still not known,” Dr. Faubion said. “We still don’t know about long-term safety and efficacy with these chemical compounds,” but clinical trials of them are ongoing.

They “would be a welcome alternative to hormone therapy for those who can’t or prefer not to use a hormonal option,” Dr. Faubion said. “However, we may need broad education of clinicians to caution against widespread abandonment of hormone therapy, particularly in women with premature or early menopause.”

Donna Klassen, LCSW, the cofounder of Let’s Talk Menopause, asked whether any of these new therapies were being tested in women with breast cancer and whether anything was known about taking oxybutynin at the same time as letrozole.

“I suspect that most women with chronic diseases would have been excluded from these initial studies, but I can’t speak to that,” Dr. Faubion said, and she wasn’t aware of any data related to taking oxybutynin and letrozole concurrently.

James Simon, MD, medical director and founder of IntimMedicine and one of those who led the research on oxybutynin, responded that his trials excluded breast cancer survivors and anyone taking aromatase inhibitors.

“It will be unlikely that, in the very near future, that data will be available because all the clinical developments on these NK3s or KNDy neuron-modulating drugs exclude cancer patients,” Dr. Simon said.

However, another attendee, Lisa Larkin, MD, of Cincinnati, introduced herself as a breast cancer survivor who takes tamoxifen and said she feels “completely comfortable” prescribing oxybutynin to breast cancer survivors.

“In terms of side effects and effectiveness in patients on tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors, I’ve had incredibly good luck with it, and I think it’s underutilized,” Dr. Larkin said. “The clinical pearl I would tell you is you can start really low, and the dry mouth really seems to improve with time.” She added that patients should be informed that it takes 2 weeks before it begins working, but the side effects eventually go away. “It becomes very tolerable, so I just encourage all of you to consider it as another great option.”

Dr. Faubion had no disclosures. Disclosure information was unavailable for Dr. Simon, Dr. Larkin, and Ms. Klassen.

Hot flashes affect three out of four women and can last 7-10 years, but the current standard of care treatment isn’t necessarily appropriate for all women who experience vasomotor symptoms, according to Stephanie Faubion, MD, MBA, director of the Mayo Clinic Women’s Health Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

For the majority of women under age 60 who are within 10 years of menopause, hormone therapy currently remains the most effective management option for hot flashes where the benefits outweigh the risks, Dr. Faubion told attendees Sept. 25 during a plenary at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. “But really, individualizing treatment is the goal, and there are some women who are going to need some other options.”

Contraindications for hormone therapy include having a history of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, active liver disease, unexplained vaginal bleeding, high-risk endometrial cancer, transient ischemic attack, and a previous venous thromboembolic event or stroke.

“Fortunately, we have things in development,” Dr. Faubion said. She reviewed a wide range of therapies that are not currently Food and Drug Administration approved for vasomotor symptoms but are either available off label or are in clinical trials.

One of these is oxybutynin, an antimuscarinic, anticholinergic agent currently used to treat overactive bladder and overactive sweating. In a 2016 trial, 73% of women taking 15 mg extended-release oxybutynin once daily rated their symptoms as “much better,” compared with 26% who received placebo. The women experienced reduced frequency and severity of hot flashes and better sleep.

Subsequent research found a 60% reduction in hot flash frequency with 2.5 mg twice a day and a 77% reduction with 5 mg twice a day, compared with a 27% reduction with placebo. The only reported side effect that occurred more often with oxybutynin was dry mouth, but there were no significant differences in reasons for discontinuation between the treatment and placebo groups.

There are, however, some potential long-term cognitive effects from oxybutynin, Dr. Faubion said. Some research has shown an increased risk of dementia from oxybutynin and from an overall higher cumulative use of anticholinergics.

“There’s some concern about that for long-term use,” she said, but it’s effective, it’s “probably not harmful [when] used short term in women with significant, bothersome hot flashes who are unwilling or unable to use hormone therapy, and the adverse effects are tolerable for most women.” Women with bladder symptoms would be especially ideal candidates since the drug already treats those.

Dr. Faubion then discussed a new estrogen called estetrol (E4), a naturally occurring estrogen with selection action in tissues that is produced by the fetal liver and crosses the placenta. It has a long half-life of 28-32 hours, and its potential mechanism may give it a different safety profile than estradiol (E2). “There may be a lower risk of drug-drug interactions; lower breast stimulation, pain or carcinogenic impact; lower impact on triglycerides; and a neutral impact on markers of coagulation,” she said.

Though estetrol was recently approved as an oral contraceptive under the name Estelle, it’s also under investigation as a postmenopausal regimen. Preliminary findings suggest it reduces vasomotor symptom severity by 44%, compared with 30% with placebo, at 15 mg, the apparent minimum effective dose. The safety profile showed no endometrial hyperplasia and no unexpected adverse events. In those taking 15 mg of estetrol, mean endometrial thickness increased from 2 to 6 mm but returned to baseline after progestin therapy.

“The 15-mg dose also positively influenced markers of bone turnover, increased HDL [cholesterol], improved glucose tolerance,” and had no effects on coagulation parameters or triglycerides, Dr. Faubion added.

Another group of potential agents being studied for hot flashes are NK3 antagonists, which aim to exploit the recent discovery that kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin (KNDy) neurons may play an important role in the etiology of vasomotor symptoms. Development of one of these, MLE 4901, was halted despite a 45% reduction in hot flashes because 3 of 28 women developed transiently elevated liver function tests, about four to six times the upper limit of normal.

Two others, fezolinetant and NT-814, are in phase 2 trials and have shown a significant reduction in symptoms, compared with placebo. The most commonly reported adverse effect in the phase 2a trial was gastrointestinal effects, but none of the participants stopped the drug because of these, and no elevated liver tests occurred. In the larger phase 2b trial, the most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events included nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, urinary tract infection, sinusitis, upper respiratory infection, headache, and cough. Five women discontinued the drug because of elevated liver enzymes.

“Overall, NK3 inhibitors appear to be generally well tolerated,” Dr. Faubion said. “There does seem to be mild transaminase elevation,” though it’s not yet known if this is an effect from this class of drugs as a whole. She noted that follicle-stimulating hormone does not significantly increase, which is important because elevated FSH is associated with poor bone health, nor does estradiol significantly increase, which is clinically relevant for women at high risk of breast cancer.

“We don’t know the effects on the heart, the brain, the bone, mood, weight, or sexual health, so there’s a lot that is still not known,” Dr. Faubion said. “We still don’t know about long-term safety and efficacy with these chemical compounds,” but clinical trials of them are ongoing.

They “would be a welcome alternative to hormone therapy for those who can’t or prefer not to use a hormonal option,” Dr. Faubion said. “However, we may need broad education of clinicians to caution against widespread abandonment of hormone therapy, particularly in women with premature or early menopause.”

Donna Klassen, LCSW, the cofounder of Let’s Talk Menopause, asked whether any of these new therapies were being tested in women with breast cancer and whether anything was known about taking oxybutynin at the same time as letrozole.

“I suspect that most women with chronic diseases would have been excluded from these initial studies, but I can’t speak to that,” Dr. Faubion said, and she wasn’t aware of any data related to taking oxybutynin and letrozole concurrently.

James Simon, MD, medical director and founder of IntimMedicine and one of those who led the research on oxybutynin, responded that his trials excluded breast cancer survivors and anyone taking aromatase inhibitors.

“It will be unlikely that, in the very near future, that data will be available because all the clinical developments on these NK3s or KNDy neuron-modulating drugs exclude cancer patients,” Dr. Simon said.

However, another attendee, Lisa Larkin, MD, of Cincinnati, introduced herself as a breast cancer survivor who takes tamoxifen and said she feels “completely comfortable” prescribing oxybutynin to breast cancer survivors.

“In terms of side effects and effectiveness in patients on tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors, I’ve had incredibly good luck with it, and I think it’s underutilized,” Dr. Larkin said. “The clinical pearl I would tell you is you can start really low, and the dry mouth really seems to improve with time.” She added that patients should be informed that it takes 2 weeks before it begins working, but the side effects eventually go away. “It becomes very tolerable, so I just encourage all of you to consider it as another great option.”

Dr. Faubion had no disclosures. Disclosure information was unavailable for Dr. Simon, Dr. Larkin, and Ms. Klassen.

FROM NAMS 2021

Migraine history linked to more severe hot flashes in postmenopausal women

Women with a history of migraine are more likely to experience severe or very severe hot flashes than women without migraines, according to research presented Sept. 24 at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. An estimated one in five women experience migraine, and women tend to have greater migraine symptoms and disability, the authors note in their background information. Since migraines are also linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, the authors sought to learn whether migraines were associated with vasomotor symptoms, another cardiovascular risk factor.

“The question in my mind is, can we do better at predicting cardiovascular risk in women because the risk prediction models that we have really don’t work all that well in women because they were designed for use in men,” Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, Penny and Bill George Director for Mayo Clinic’s Center for Women’s Health said in an interview. “My ultimate goal is to see if we can somehow use big data, artificial intelligence to figure out how to weight some of these female-specific or female-predominant factors to come up with a better model for cardiovascular risk prediction.”

The researchers analyzed cross-sectional data from 3,308 women who participated in the Data Registry on the Experiences of Aging, Menopause and Sexuality (DREAMS) study through Mayo Clinic sites in Rochester, Minn.; Scottsdale, Ariz.; and Jacksonville, Fla.. The women ranged in age from 45 to 60 years old, with an average age of 53, and the vast majority of them were white (95%) and had at least some college (93%). Most were also in a long-term relationship (85%), and a majority were employed (69%) and postmenopausal (67%).

The data, collected between May 2015 and December 2019, included a self-reported history of migraine and questionnaires that included the Menopause Rating Scale of menopause-related symptoms.

The researchers adjusted their findings to account for body mass index (BMI), menopause status, smoking status, depression, anxiety, current use of hormone therapy, and presence of low back pain within the past year. ”The diagnosis of low back pain, another pain disorder, was used to test the specificity of the association of migraine and vasomotor symptoms,” the authors write.

Just over a quarter of the women (27%) reported a history of migraine, and these women’s Menopause Rating Scale scores were an average 1.36 points greater than women without a history of migraines (P < .001). Women with self-reported migraine were also 40% more likely than women without migraines to report severe or very severe flashes versus reporting no hot flashes at all (odds ratio, 1.4; P = .02).

“The odds of reporting more severe hot flashes increased monotonically in women with a history of migraine,” the authors report. “In addition, women with low back pain had higher Menopause Rating Scale scores, but were no more likely to have severe/very severe hot flashes than those without back pain, confirming the specificity of the link between vasomotor symptoms and migraine.”

It’s not clear if migraine or hot flashes are risk factors that add to a woman’s existing cardiovascular risk profile or whether they are simply biomarkers of a shared pathway, Dr Faubion said in an interview. She speculates that the common link between migraine and vasomotor symptoms could be neurovascular dysregulation.

Rachael B. Smith, DO, of the department of ob.gyn. at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, was not involved in the research but found that hypothesis plausible as well.

“Our neurologic and vascular systems are coordinated physiologic processes working together for basic brain and body function,” Dr. Smith said in an interview. Some of the symptoms of migraines and menopause are similar and both are often explained by the dysfunction of these systems. The association between history of migraines and severity of vasomotor symptoms is very likely to be explained by this dysregulation between the neurologic and vascular systems.”

Dr. Smith also pointed out, however, that the largely homogeneous study population, all from the same national clinic system, makes it difficult to know how generalizable these findings are.

The primary clinical implications of these findings are that women’s providers need to be sure they’re asking their patients about migraine history and symptoms.

“The counseling we provide on menopausal symptoms should be better tailored to our patients’ medical history, specifically inquiring about history of migraines and how this may impact their symptoms,” Dr. Smith said.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Faubion and Dr. Smith had no disclosures.

Women with a history of migraine are more likely to experience severe or very severe hot flashes than women without migraines, according to research presented Sept. 24 at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. An estimated one in five women experience migraine, and women tend to have greater migraine symptoms and disability, the authors note in their background information. Since migraines are also linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, the authors sought to learn whether migraines were associated with vasomotor symptoms, another cardiovascular risk factor.

“The question in my mind is, can we do better at predicting cardiovascular risk in women because the risk prediction models that we have really don’t work all that well in women because they were designed for use in men,” Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, Penny and Bill George Director for Mayo Clinic’s Center for Women’s Health said in an interview. “My ultimate goal is to see if we can somehow use big data, artificial intelligence to figure out how to weight some of these female-specific or female-predominant factors to come up with a better model for cardiovascular risk prediction.”

The researchers analyzed cross-sectional data from 3,308 women who participated in the Data Registry on the Experiences of Aging, Menopause and Sexuality (DREAMS) study through Mayo Clinic sites in Rochester, Minn.; Scottsdale, Ariz.; and Jacksonville, Fla.. The women ranged in age from 45 to 60 years old, with an average age of 53, and the vast majority of them were white (95%) and had at least some college (93%). Most were also in a long-term relationship (85%), and a majority were employed (69%) and postmenopausal (67%).

The data, collected between May 2015 and December 2019, included a self-reported history of migraine and questionnaires that included the Menopause Rating Scale of menopause-related symptoms.

The researchers adjusted their findings to account for body mass index (BMI), menopause status, smoking status, depression, anxiety, current use of hormone therapy, and presence of low back pain within the past year. ”The diagnosis of low back pain, another pain disorder, was used to test the specificity of the association of migraine and vasomotor symptoms,” the authors write.

Just over a quarter of the women (27%) reported a history of migraine, and these women’s Menopause Rating Scale scores were an average 1.36 points greater than women without a history of migraines (P < .001). Women with self-reported migraine were also 40% more likely than women without migraines to report severe or very severe flashes versus reporting no hot flashes at all (odds ratio, 1.4; P = .02).

“The odds of reporting more severe hot flashes increased monotonically in women with a history of migraine,” the authors report. “In addition, women with low back pain had higher Menopause Rating Scale scores, but were no more likely to have severe/very severe hot flashes than those without back pain, confirming the specificity of the link between vasomotor symptoms and migraine.”

It’s not clear if migraine or hot flashes are risk factors that add to a woman’s existing cardiovascular risk profile or whether they are simply biomarkers of a shared pathway, Dr Faubion said in an interview. She speculates that the common link between migraine and vasomotor symptoms could be neurovascular dysregulation.

Rachael B. Smith, DO, of the department of ob.gyn. at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, was not involved in the research but found that hypothesis plausible as well.

“Our neurologic and vascular systems are coordinated physiologic processes working together for basic brain and body function,” Dr. Smith said in an interview. Some of the symptoms of migraines and menopause are similar and both are often explained by the dysfunction of these systems. The association between history of migraines and severity of vasomotor symptoms is very likely to be explained by this dysregulation between the neurologic and vascular systems.”

Dr. Smith also pointed out, however, that the largely homogeneous study population, all from the same national clinic system, makes it difficult to know how generalizable these findings are.

The primary clinical implications of these findings are that women’s providers need to be sure they’re asking their patients about migraine history and symptoms.

“The counseling we provide on menopausal symptoms should be better tailored to our patients’ medical history, specifically inquiring about history of migraines and how this may impact their symptoms,” Dr. Smith said.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Faubion and Dr. Smith had no disclosures.

Women with a history of migraine are more likely to experience severe or very severe hot flashes than women without migraines, according to research presented Sept. 24 at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. An estimated one in five women experience migraine, and women tend to have greater migraine symptoms and disability, the authors note in their background information. Since migraines are also linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, the authors sought to learn whether migraines were associated with vasomotor symptoms, another cardiovascular risk factor.

“The question in my mind is, can we do better at predicting cardiovascular risk in women because the risk prediction models that we have really don’t work all that well in women because they were designed for use in men,” Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, Penny and Bill George Director for Mayo Clinic’s Center for Women’s Health said in an interview. “My ultimate goal is to see if we can somehow use big data, artificial intelligence to figure out how to weight some of these female-specific or female-predominant factors to come up with a better model for cardiovascular risk prediction.”

The researchers analyzed cross-sectional data from 3,308 women who participated in the Data Registry on the Experiences of Aging, Menopause and Sexuality (DREAMS) study through Mayo Clinic sites in Rochester, Minn.; Scottsdale, Ariz.; and Jacksonville, Fla.. The women ranged in age from 45 to 60 years old, with an average age of 53, and the vast majority of them were white (95%) and had at least some college (93%). Most were also in a long-term relationship (85%), and a majority were employed (69%) and postmenopausal (67%).

The data, collected between May 2015 and December 2019, included a self-reported history of migraine and questionnaires that included the Menopause Rating Scale of menopause-related symptoms.

The researchers adjusted their findings to account for body mass index (BMI), menopause status, smoking status, depression, anxiety, current use of hormone therapy, and presence of low back pain within the past year. ”The diagnosis of low back pain, another pain disorder, was used to test the specificity of the association of migraine and vasomotor symptoms,” the authors write.

Just over a quarter of the women (27%) reported a history of migraine, and these women’s Menopause Rating Scale scores were an average 1.36 points greater than women without a history of migraines (P < .001). Women with self-reported migraine were also 40% more likely than women without migraines to report severe or very severe flashes versus reporting no hot flashes at all (odds ratio, 1.4; P = .02).

“The odds of reporting more severe hot flashes increased monotonically in women with a history of migraine,” the authors report. “In addition, women with low back pain had higher Menopause Rating Scale scores, but were no more likely to have severe/very severe hot flashes than those without back pain, confirming the specificity of the link between vasomotor symptoms and migraine.”

It’s not clear if migraine or hot flashes are risk factors that add to a woman’s existing cardiovascular risk profile or whether they are simply biomarkers of a shared pathway, Dr Faubion said in an interview. She speculates that the common link between migraine and vasomotor symptoms could be neurovascular dysregulation.

Rachael B. Smith, DO, of the department of ob.gyn. at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, was not involved in the research but found that hypothesis plausible as well.

“Our neurologic and vascular systems are coordinated physiologic processes working together for basic brain and body function,” Dr. Smith said in an interview. Some of the symptoms of migraines and menopause are similar and both are often explained by the dysfunction of these systems. The association between history of migraines and severity of vasomotor symptoms is very likely to be explained by this dysregulation between the neurologic and vascular systems.”

Dr. Smith also pointed out, however, that the largely homogeneous study population, all from the same national clinic system, makes it difficult to know how generalizable these findings are.

The primary clinical implications of these findings are that women’s providers need to be sure they’re asking their patients about migraine history and symptoms.

“The counseling we provide on menopausal symptoms should be better tailored to our patients’ medical history, specifically inquiring about history of migraines and how this may impact their symptoms,” Dr. Smith said.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Faubion and Dr. Smith had no disclosures.

FROM NAMS 2021

PCOS linked to menopausal urogenital symptoms but not hot flashes

Women with a history of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are more likely to experience somatic and urogenital symptoms post menopause, but they were no more likely to experience severe hot flashes than were other women with similar characteristics, according to research presented Sept. 24 at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

PCOS and vasomotor symptoms are each risk factors for cardiovascular disease, so researchers wanted to find out whether they were linked to one another, which might indicate that they are markers for the same underlying mechanisms that increase heart disease risk. The lack of an association, however, raises questions about how much each of these conditions might independently increase cardiovascular risk.

“Should we take a little more time to truly risk-assess these patients not just with their ASCVD risk score, but take into account that they have PCOS and they’re going through menopause, and how severe their hot flashes are?” asked Angie S. Lobo, MD, an internal medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., when she discussed her findings in an interview.

The association between PCOS and urogenital symptoms was surprising, Dr. Lobo said, but she said she suspects the reason for the finding may be the self-reported nature of the study.

“If you ask the question, you get the answer,” Dr. Lobo said. ”Are we just not asking the right questions to our patients? And should we be doing this more often? This is an exciting finding because there’s so much room to improve the clinical care of our patients.”

The researchers analyzed data from 3,308 women, ages 45-60, in a cross-sectional study from the Data Registry on the Experiences of Aging, Menopause, and Sexuality (DREAMS). The study occurred at Mayo Clinic locations between May 2015 and December 2019 in Rochester, Minn., in Scottsdale, Ariz., and in Jacksonville, Fla.

The women were an average 53 years old and were primarily White, educated, and postmenopausal. Among the 4.6% of women with a self-reported history of PCOS, 56% of them reported depression symptoms, compared to 42% of women without PCOS. Those with PCOS also had nearly twice the prevalence of obesity – 42% versus 22.5% among women without PCOS – and had a higher average overall score on the Menopause Rating Scale (17.7 vs. 14.7; P < .001).

Although women with PCOS initially had a greater burden of psychological symptoms on the same scale, that association disappeared after adjustment for menopause status, body mass index, depression, anxiety, and current use of hormone therapy. Even after adjustment, however, women with PCOS had higher average scores for somatic symptoms (6.7 vs. 5.6) and urogenital symptoms (5.2 vs. 4.3) than those of women without PCOS (P < .001).

Severe or very severe hot flashes were no more likely in women with a history of PCOS than in the other women in the study.

”The mechanisms underlying the correlation between PCOS and menopause symptoms in the psychological and urogenital symptom domains requires further study, although the well-known association between PCOS and mood disorders may explain the high psychological symptom burden in these women during the menopause transition,” the authors concluded.

Rachael B. Smith, DO, clinical assistant professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Arizona in Phoenix, said she was not surprised to see an association between PCOS and menopause symptoms overall, but she was surprised that PCOS did not correlate with severity of vasomotor symptoms. But Dr. Smith pointed out that the sample size of women with PCOS is fairly small (n = 151).

“Given that PCOS prevalence is about 6%-10%, I feel this association should be further studied to improve our counseling and treatment for this PCOS population,” Dr. Smith, who was not involved in the research, said in an interview. “The take-home message for physicians is improved patient-tailored counseling that takes into account patients’ prior medical history of PCOS.”

Although it will require more research to find out, Dr. Smith said she suspects that PCOS and vasomotor symptoms are additive risk factors for cardiovascular disease. She also noted that the study is limited by the homogeneity of the study population.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lobo and Dr. Smith had no disclosures.

Women with a history of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are more likely to experience somatic and urogenital symptoms post menopause, but they were no more likely to experience severe hot flashes than were other women with similar characteristics, according to research presented Sept. 24 at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

PCOS and vasomotor symptoms are each risk factors for cardiovascular disease, so researchers wanted to find out whether they were linked to one another, which might indicate that they are markers for the same underlying mechanisms that increase heart disease risk. The lack of an association, however, raises questions about how much each of these conditions might independently increase cardiovascular risk.

“Should we take a little more time to truly risk-assess these patients not just with their ASCVD risk score, but take into account that they have PCOS and they’re going through menopause, and how severe their hot flashes are?” asked Angie S. Lobo, MD, an internal medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., when she discussed her findings in an interview.

The association between PCOS and urogenital symptoms was surprising, Dr. Lobo said, but she said she suspects the reason for the finding may be the self-reported nature of the study.

“If you ask the question, you get the answer,” Dr. Lobo said. ”Are we just not asking the right questions to our patients? And should we be doing this more often? This is an exciting finding because there’s so much room to improve the clinical care of our patients.”

The researchers analyzed data from 3,308 women, ages 45-60, in a cross-sectional study from the Data Registry on the Experiences of Aging, Menopause, and Sexuality (DREAMS). The study occurred at Mayo Clinic locations between May 2015 and December 2019 in Rochester, Minn., in Scottsdale, Ariz., and in Jacksonville, Fla.

The women were an average 53 years old and were primarily White, educated, and postmenopausal. Among the 4.6% of women with a self-reported history of PCOS, 56% of them reported depression symptoms, compared to 42% of women without PCOS. Those with PCOS also had nearly twice the prevalence of obesity – 42% versus 22.5% among women without PCOS – and had a higher average overall score on the Menopause Rating Scale (17.7 vs. 14.7; P < .001).

Although women with PCOS initially had a greater burden of psychological symptoms on the same scale, that association disappeared after adjustment for menopause status, body mass index, depression, anxiety, and current use of hormone therapy. Even after adjustment, however, women with PCOS had higher average scores for somatic symptoms (6.7 vs. 5.6) and urogenital symptoms (5.2 vs. 4.3) than those of women without PCOS (P < .001).

Severe or very severe hot flashes were no more likely in women with a history of PCOS than in the other women in the study.

”The mechanisms underlying the correlation between PCOS and menopause symptoms in the psychological and urogenital symptom domains requires further study, although the well-known association between PCOS and mood disorders may explain the high psychological symptom burden in these women during the menopause transition,” the authors concluded.

Rachael B. Smith, DO, clinical assistant professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Arizona in Phoenix, said she was not surprised to see an association between PCOS and menopause symptoms overall, but she was surprised that PCOS did not correlate with severity of vasomotor symptoms. But Dr. Smith pointed out that the sample size of women with PCOS is fairly small (n = 151).

“Given that PCOS prevalence is about 6%-10%, I feel this association should be further studied to improve our counseling and treatment for this PCOS population,” Dr. Smith, who was not involved in the research, said in an interview. “The take-home message for physicians is improved patient-tailored counseling that takes into account patients’ prior medical history of PCOS.”

Although it will require more research to find out, Dr. Smith said she suspects that PCOS and vasomotor symptoms are additive risk factors for cardiovascular disease. She also noted that the study is limited by the homogeneity of the study population.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lobo and Dr. Smith had no disclosures.

Women with a history of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are more likely to experience somatic and urogenital symptoms post menopause, but they were no more likely to experience severe hot flashes than were other women with similar characteristics, according to research presented Sept. 24 at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

PCOS and vasomotor symptoms are each risk factors for cardiovascular disease, so researchers wanted to find out whether they were linked to one another, which might indicate that they are markers for the same underlying mechanisms that increase heart disease risk. The lack of an association, however, raises questions about how much each of these conditions might independently increase cardiovascular risk.

“Should we take a little more time to truly risk-assess these patients not just with their ASCVD risk score, but take into account that they have PCOS and they’re going through menopause, and how severe their hot flashes are?” asked Angie S. Lobo, MD, an internal medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., when she discussed her findings in an interview.

The association between PCOS and urogenital symptoms was surprising, Dr. Lobo said, but she said she suspects the reason for the finding may be the self-reported nature of the study.

“If you ask the question, you get the answer,” Dr. Lobo said. ”Are we just not asking the right questions to our patients? And should we be doing this more often? This is an exciting finding because there’s so much room to improve the clinical care of our patients.”

The researchers analyzed data from 3,308 women, ages 45-60, in a cross-sectional study from the Data Registry on the Experiences of Aging, Menopause, and Sexuality (DREAMS). The study occurred at Mayo Clinic locations between May 2015 and December 2019 in Rochester, Minn., in Scottsdale, Ariz., and in Jacksonville, Fla.

The women were an average 53 years old and were primarily White, educated, and postmenopausal. Among the 4.6% of women with a self-reported history of PCOS, 56% of them reported depression symptoms, compared to 42% of women without PCOS. Those with PCOS also had nearly twice the prevalence of obesity – 42% versus 22.5% among women without PCOS – and had a higher average overall score on the Menopause Rating Scale (17.7 vs. 14.7; P < .001).

Although women with PCOS initially had a greater burden of psychological symptoms on the same scale, that association disappeared after adjustment for menopause status, body mass index, depression, anxiety, and current use of hormone therapy. Even after adjustment, however, women with PCOS had higher average scores for somatic symptoms (6.7 vs. 5.6) and urogenital symptoms (5.2 vs. 4.3) than those of women without PCOS (P < .001).

Severe or very severe hot flashes were no more likely in women with a history of PCOS than in the other women in the study.

”The mechanisms underlying the correlation between PCOS and menopause symptoms in the psychological and urogenital symptom domains requires further study, although the well-known association between PCOS and mood disorders may explain the high psychological symptom burden in these women during the menopause transition,” the authors concluded.

Rachael B. Smith, DO, clinical assistant professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Arizona in Phoenix, said she was not surprised to see an association between PCOS and menopause symptoms overall, but she was surprised that PCOS did not correlate with severity of vasomotor symptoms. But Dr. Smith pointed out that the sample size of women with PCOS is fairly small (n = 151).

“Given that PCOS prevalence is about 6%-10%, I feel this association should be further studied to improve our counseling and treatment for this PCOS population,” Dr. Smith, who was not involved in the research, said in an interview. “The take-home message for physicians is improved patient-tailored counseling that takes into account patients’ prior medical history of PCOS.”

Although it will require more research to find out, Dr. Smith said she suspects that PCOS and vasomotor symptoms are additive risk factors for cardiovascular disease. She also noted that the study is limited by the homogeneity of the study population.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lobo and Dr. Smith had no disclosures.

FROM NAMS 2021

Updates to CDC’s STI guidelines relevant to midlife women too

Sexually transmitted infection rates have not increased as dramatically in older women as they have in women in their teens and 20s, but rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea in women over age 35 have seen a steady incline over the past decade, and syphilis rates have climbed steeply, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That makes the STI treatment guidelines released by the CDC in July even timelier for practitioners of menopause medicine, according to Michael S. Policar, MD, MPH, a professor emeritus of ob.gyn. and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco.

Dr. Policar discussed what clinicians need to know about STIs in midlife women at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. Even the nomenclature change in the guidelines from “sexually transmitted diseases” to “sexually transmitted infections” is important “because they want to acknowledge the fact that a lot of the sexually transmitted infections that we’re treating are asymptomatic, are colonizations, and are not yet diseases,” Dr. Policar said. “We’re trying to be much more expansive in thinking about finding these infections before they actually start causing morbidity in the form of a disease.”

Sexual history

The primary guidelines update for taking sexual history is the recommendation to ask patients about their intentions regarding pregnancy. The “5 Ps” of sexual history are now Partners, Practices, Protection from STIs, Past history of STIs, and Pregnancy intention.

“There should be a sixth P that has to do with pleasure questions,” Policar added. “We ask all the time for patients that we see in the context of perimenopausal and menopausal services, ‘Are you satisfied with your sexual relationship with your partner?’ Hopefully that will make it into the CDC guidelines as the sixth P at some point, but for now, that’s aspirational.”

In asking about partners, instead of asking patients whether they have sex with men, women, or both, clinicians should ask first if the patient is having sex of any kind – oral, vaginal, or anal – with anyone. From there, providers should ask how many sex partners the patient has had, the gender(s) of the partners, and whether they or their partners have other sex partners, using more gender-inclusive language.

When asking about practices, in addition to asking about the type of sexual contact patients have had, additional questions include whether the patient met their partners online or through apps, whether they or any of their partners use drugs, and whether the patient has exchanged sex for any needs, such as money, housing, or drugs. The additional questions can identify those at higher risk for STIs.

After reviewing the CDC’s list of risk factors for gonorrhea and chlamydia screening, Dr. Policar shared the screening list from the California Department of Public Health, which he finds more helpful:

- History of gonorrhea, chlamydia, or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in the past 2 years.

- More than 1 sexual partner in the past year.

- New sexual partner within 90 days.

- Reason to believe that a sex partner has had other partners in the past year.

- Exchanging sex for drugs or money within the past year.

- Other factors identified locally, including prevalence of infection in the community.

STI screening guidelines

For those with a positive gonorrhea/chlamydia (GC/CT) screen, a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) vaginal swab is the preferred specimen source, and self-collection is fine for women of any age, Dr. Policar said. In addition, cis-women who received anal intercourse in the preceding year should consider undergoing a rectal GC/CT NAAT, and those who performed oral sex should consider a pharyngeal GC/CT NAAT, based on shared clinical decision-making. A rectal swab requires an insertion of 3-4 cm and a 360-degree twirl of the wrist, not the swab, to ensure you get a sample from the entire circumference. Pharyngeal samples require swabbing both tonsillar pillars while taking care for those who may gag.

For contact testing – asymptomatic people who have had a high-risk sexual exposure – providers should test for gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, and syphilis but not for herpes, high-risk HPV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or bacterial vaginosis. “Maybe we’ll do a screen for trichomoniasis, and maybe we’ll offer herpes type 2 serology or antibody screening,” Dr. Policar said. Providers should also ask patients requesting contact testing if they have been vaccinated for hepatitis B. If not, “the conversation should be how can we get you vaccinated for hepatitis B,” Dr. Policar said.

HIV screening only needs to occur once between the ages of 15 and 65 for low-risk people and then once annually (or more often if necessary) for those who have a sex partner with HIV, use injectable drugs, engage in commercial sex work, have a new sex partner with unknown HIV status, received care at an STD or TB clinic, or were in a correctional facility or homeless shelter.

Those at increased risk for syphilis include men who have sex with men, men under age 29, and anyone living with HIV or who has a history of incarceration or a history of commercial sex work. In addition, African Americans have the greatest risk for syphilis of racial/ethnic groups, followed by Hispanics. Most adults only require hepatitis C screening with anti-hep C antibody testing once in their lifetime. Periodic hepatitis C screening should occur for people who inject drugs. If the screening is positive, providers should conduct an RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test to determine whether a chronic infection is present.

Trichomoniasis screening should occur annually in women living with HIV or in correctional facilities. Others to consider screening include people with new or multiple sex partners, a history of STIs, inconsistent condom use, a history of sex work, and intravenous drug use. Dr. Policar also noted that several new assays, including NAAT, PCR, and a rapid test, are available for trichomoniasis.

STI treatment guidelines

For women with mucoprurulent cervicitis, the cause could be chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes, trichomonas, mycoplasma, or even progesterone from pregnancy or contraception, Dr. Policar said. The new preferred treatment is 100 mg of doxycycline. The alternative, albeit less preferred, treatment is 1 g azithromycin.

The preferred treatment for chlamydia is now 100 mg oral doxycycline twice daily, or doxycycline 200 mg delayed-release once daily, for 7 days. Alternative regimens include 1 g oral azithromycin in a single dose or 500 mg oral levofloxacin once daily for 7 days. The switch to recommending doxycycline over azithromycin is based on recent evidence showing that doxycycline has a slightly higher efficacy for urogenital chlamydia and a substantially higher efficacy for rectal chlamydia. In addition, an increasing proportion of gonorrheal infections have shown resistance to azithromycin, particularly beginning in 2014.

Preferred treatment of new, uncomplicated gonorrhea infections of the cervix, urethra, rectum, and pharynx is one 500-mg dose of ceftriaxone for those weighing under 150 kg and 1 g for those weighing 150 kg or more. If ceftriaxone is unavailable, the new alternative recommended treatment for gonorrhea is 800 mg cefixime. For pharyngeal gonorrhea only, the CDC recommends a test-of-cure 7-14 days after treatment.

For gonorrheal infections, the CDC also recommends treatment with doxycycline if chlamydia has not been excluded, but the agency no longer recommends dual therapy with azithromycin unless it’s used in place of doxycycline for those who are pregnant, have an allergy, or may not be compliant with a 7-day doxycycline regimen.

The preferred treatment for bacterial vaginosis has not changed. The new recommended regimen for trichomoniasis is 500 mg oral metronidazole for 7 days, with the alternative being a single 2-g dose of tinidazole. Male partners should receive 2 g oral metronidazole. The CDC also notes that patients taking metronidazole no longer need to abstain from alcohol during treatment.

”Another area where the guidelines changed is in their description of expedited partner therapy, which means that, when we find an index case who has gonorrhea or chlamydia, we always have a discussion with her about getting her partners treated,” Dr. Policar said. “The CDC was quite clear that the responsibility for discussing partner treatment rests with us as the diagnosing provider” since city and county health departments don’t have the time or resources for contact tracing these STIs.

The two main ways to treat partners are to have the patient bring their partner(s) to the appointment with them or to do patient-delivered partner therapy. Ideally, clinicians who dispense their own medications can give the patient enough drugs to give her partner(s) a complete dose as well. Otherwise, providers can prescribe extra doses in the index patients’ name or write prescriptions in the partner’s name.

“In every state of the union now, it is legal for you to to prescribe antibiotics for partners sight unseen, Dr. Policar said.

Margaret Sullivan, MD, an ob.gyn. from rural western North Carolina, noted during the Q&A that an obstacle to partner therapy at her practice has been cost, particularly since many of the men don’t have insurance.

“I have not heard before of prescribing the extra doses for partners under the patient’s name,” Dr. Sullivan said. “I’ve thought about doing it, but [was worried about] it potentially being fraudulent if that patient has Medicaid and we’re prescribing extra doses under her name, so how do you work around that?”

Dr. Policar acknowledged that barrier and recommended that patients use the website/app Goodrx.com to find discounts for out-of-pocket generic medications. He also noted the occasional obstacle of pharmacists balking at filling a double or triple dose.

“What we’ve been suggesting in that circumstance is to literally copy that part of the CDC guidelines, which explains expedited partner therapy or patient-delivered partner therapy and send that off to the pharmacist so they can see that it’s a national recommendation of the CDC,” Dr. Policar said.