User login

Dapagliflozin DELIVERs regardless of systolic pressure in HFpEF

Whatever the mechanism of benefit from dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in patients with heart failure (HF) – and potentially also other sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors – its blood pressure lowering effects aren’t likely to contribute much.

Indeed, at least in patients with HF and non-reduced ejection fractions, dapagliflozin has only a modest BP-lowering effect and cuts cardiovascular (CV) risk regardless of baseline pressure or change in systolic BP, suggests a secondary analysis from the large placebo-controlled DELIVER trial.

Systolic BP fell over 1 month by just under 2 mmHg, on average, in trial patients with either mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction (HFmrEF or HFpEF, respectively) assigned to take dapagliflozin versus placebo.

The effect was achieved without increasing the risk for adverse events from dapagliflozin, even among patients with the lowest baseline systolic pressures. Adverse outcomes overall, however, were more common at the lowest systolic BP level than at higher pressures, researchers reported.

They say the findings should help alleviate long-standing concerns that initiating SGLT2 inhibitors, with their recognized diuretic effects, might present a hazard in patients with HF and low systolic BP.

“It is a consistent theme in heart failure trials that the blood pressure–lowering effect of SGLT2 inhibitors is more modest than it is in non–heart-failure populations,” Senthil Selvaraj, MD, Duke University, Durham, N.C., told this news organization.

Changes to antihypertensive drug therapy throughout the trial, which presumably enhanced BP responses and “might occur more frequently in the placebo group,” Dr. Selvaraj said, “might explain why the blood pressure effect is a little bit more modest in this population.”

Dr. Selvaraj presented the analysis at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, held in National Harbor, Md., and is lead author on its same-day publication in JACC: Heart Failure.

The findings “reinforce the clinical benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure across the full spectrum of ejection fractions and large range of systolic blood pressures,” said Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center, who was not part of the DELIVER analysis.

The study’s greater adjusted risks for CV and all-cause mortality risks at the lowest baseline systolic pressures “parallels a series of observational analyses from registries, including OPTIMIZE-HF,” Dr. Fonarow observed.

In those prior studies of patients with established HFpEF, “systolic BP less than 120 mmHg or even 130 mmHg was associated with worse outcomes than those with higher systolic BP.”

The current findings, therefore, “highlight how optimal blood pressure targets in patients with established heart failure have not been well established,” Dr. Fonarow said.

The analysis included all 6,263 participants in DELIVER, outpatients or patients hospitalized for worsening HF who were in NYHA class 2-4 with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) greater than 40%. They averaged 72 in age, and 44% were women. Their mean baseline systolic BP was 128 mmHg.

After 1 month, mean systolic BP had fallen by 1.8 mmHg (P < .001) in patients who had been randomly assigned to dapagliflozin versus placebo. The effect was consistent (interaction P = .16) across all systolic BP categories (less than 120 mmHg, 120-129 mmHg, 130-139 mmHg, and 140 mmHg or higher).

The effect was similarly independent of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and LVEF (interaction P = .30 and P = .33, respectively), Dr. Selvaraj reported.

In an analysis adjusted for both baseline and 1-month change in systolic BP, the effect of dapagliflozin on the primary endpoint was “minimally attenuated,” compared with the primary analysis, he said. That suggests the clinical benefits “did not significantly relate to the blood pressure–lowering effect” of the SGLT2 inhibitor.

In that analysis, the hazard ratio for CV death or worsening HF for dapagliflozin versus placebo was 0.85 (95% confidence interval, 0.75-0.96; P = .010). The HR had been 0.82 (95% CI, 0.73-0.92; P < .001) overall in the DELIVER primary analysis.

The current study doesn’t shed further light on the main SGLT2 inhibitor mechanism of clinical benefit in nondiabetics with HF, which remains a mystery.

“There is a diuretic effect, but it’s not incredibly robust,” Dr. Selvaraj observed. It may contribute to the drugs’ benefits, “but it’s definitely more than that – a lot more than that.”

DELIVER was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Selvaraj reported no relevant conflicts. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Fonarow has reported receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Cytokinetics, Edwards, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Whatever the mechanism of benefit from dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in patients with heart failure (HF) – and potentially also other sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors – its blood pressure lowering effects aren’t likely to contribute much.

Indeed, at least in patients with HF and non-reduced ejection fractions, dapagliflozin has only a modest BP-lowering effect and cuts cardiovascular (CV) risk regardless of baseline pressure or change in systolic BP, suggests a secondary analysis from the large placebo-controlled DELIVER trial.

Systolic BP fell over 1 month by just under 2 mmHg, on average, in trial patients with either mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction (HFmrEF or HFpEF, respectively) assigned to take dapagliflozin versus placebo.

The effect was achieved without increasing the risk for adverse events from dapagliflozin, even among patients with the lowest baseline systolic pressures. Adverse outcomes overall, however, were more common at the lowest systolic BP level than at higher pressures, researchers reported.

They say the findings should help alleviate long-standing concerns that initiating SGLT2 inhibitors, with their recognized diuretic effects, might present a hazard in patients with HF and low systolic BP.

“It is a consistent theme in heart failure trials that the blood pressure–lowering effect of SGLT2 inhibitors is more modest than it is in non–heart-failure populations,” Senthil Selvaraj, MD, Duke University, Durham, N.C., told this news organization.

Changes to antihypertensive drug therapy throughout the trial, which presumably enhanced BP responses and “might occur more frequently in the placebo group,” Dr. Selvaraj said, “might explain why the blood pressure effect is a little bit more modest in this population.”

Dr. Selvaraj presented the analysis at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, held in National Harbor, Md., and is lead author on its same-day publication in JACC: Heart Failure.

The findings “reinforce the clinical benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure across the full spectrum of ejection fractions and large range of systolic blood pressures,” said Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center, who was not part of the DELIVER analysis.

The study’s greater adjusted risks for CV and all-cause mortality risks at the lowest baseline systolic pressures “parallels a series of observational analyses from registries, including OPTIMIZE-HF,” Dr. Fonarow observed.

In those prior studies of patients with established HFpEF, “systolic BP less than 120 mmHg or even 130 mmHg was associated with worse outcomes than those with higher systolic BP.”

The current findings, therefore, “highlight how optimal blood pressure targets in patients with established heart failure have not been well established,” Dr. Fonarow said.

The analysis included all 6,263 participants in DELIVER, outpatients or patients hospitalized for worsening HF who were in NYHA class 2-4 with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) greater than 40%. They averaged 72 in age, and 44% were women. Their mean baseline systolic BP was 128 mmHg.

After 1 month, mean systolic BP had fallen by 1.8 mmHg (P < .001) in patients who had been randomly assigned to dapagliflozin versus placebo. The effect was consistent (interaction P = .16) across all systolic BP categories (less than 120 mmHg, 120-129 mmHg, 130-139 mmHg, and 140 mmHg or higher).

The effect was similarly independent of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and LVEF (interaction P = .30 and P = .33, respectively), Dr. Selvaraj reported.

In an analysis adjusted for both baseline and 1-month change in systolic BP, the effect of dapagliflozin on the primary endpoint was “minimally attenuated,” compared with the primary analysis, he said. That suggests the clinical benefits “did not significantly relate to the blood pressure–lowering effect” of the SGLT2 inhibitor.

In that analysis, the hazard ratio for CV death or worsening HF for dapagliflozin versus placebo was 0.85 (95% confidence interval, 0.75-0.96; P = .010). The HR had been 0.82 (95% CI, 0.73-0.92; P < .001) overall in the DELIVER primary analysis.

The current study doesn’t shed further light on the main SGLT2 inhibitor mechanism of clinical benefit in nondiabetics with HF, which remains a mystery.

“There is a diuretic effect, but it’s not incredibly robust,” Dr. Selvaraj observed. It may contribute to the drugs’ benefits, “but it’s definitely more than that – a lot more than that.”

DELIVER was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Selvaraj reported no relevant conflicts. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Fonarow has reported receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Cytokinetics, Edwards, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Whatever the mechanism of benefit from dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in patients with heart failure (HF) – and potentially also other sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors – its blood pressure lowering effects aren’t likely to contribute much.

Indeed, at least in patients with HF and non-reduced ejection fractions, dapagliflozin has only a modest BP-lowering effect and cuts cardiovascular (CV) risk regardless of baseline pressure or change in systolic BP, suggests a secondary analysis from the large placebo-controlled DELIVER trial.

Systolic BP fell over 1 month by just under 2 mmHg, on average, in trial patients with either mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction (HFmrEF or HFpEF, respectively) assigned to take dapagliflozin versus placebo.

The effect was achieved without increasing the risk for adverse events from dapagliflozin, even among patients with the lowest baseline systolic pressures. Adverse outcomes overall, however, were more common at the lowest systolic BP level than at higher pressures, researchers reported.

They say the findings should help alleviate long-standing concerns that initiating SGLT2 inhibitors, with their recognized diuretic effects, might present a hazard in patients with HF and low systolic BP.

“It is a consistent theme in heart failure trials that the blood pressure–lowering effect of SGLT2 inhibitors is more modest than it is in non–heart-failure populations,” Senthil Selvaraj, MD, Duke University, Durham, N.C., told this news organization.

Changes to antihypertensive drug therapy throughout the trial, which presumably enhanced BP responses and “might occur more frequently in the placebo group,” Dr. Selvaraj said, “might explain why the blood pressure effect is a little bit more modest in this population.”

Dr. Selvaraj presented the analysis at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, held in National Harbor, Md., and is lead author on its same-day publication in JACC: Heart Failure.

The findings “reinforce the clinical benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure across the full spectrum of ejection fractions and large range of systolic blood pressures,” said Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center, who was not part of the DELIVER analysis.

The study’s greater adjusted risks for CV and all-cause mortality risks at the lowest baseline systolic pressures “parallels a series of observational analyses from registries, including OPTIMIZE-HF,” Dr. Fonarow observed.

In those prior studies of patients with established HFpEF, “systolic BP less than 120 mmHg or even 130 mmHg was associated with worse outcomes than those with higher systolic BP.”

The current findings, therefore, “highlight how optimal blood pressure targets in patients with established heart failure have not been well established,” Dr. Fonarow said.

The analysis included all 6,263 participants in DELIVER, outpatients or patients hospitalized for worsening HF who were in NYHA class 2-4 with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) greater than 40%. They averaged 72 in age, and 44% were women. Their mean baseline systolic BP was 128 mmHg.

After 1 month, mean systolic BP had fallen by 1.8 mmHg (P < .001) in patients who had been randomly assigned to dapagliflozin versus placebo. The effect was consistent (interaction P = .16) across all systolic BP categories (less than 120 mmHg, 120-129 mmHg, 130-139 mmHg, and 140 mmHg or higher).

The effect was similarly independent of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and LVEF (interaction P = .30 and P = .33, respectively), Dr. Selvaraj reported.

In an analysis adjusted for both baseline and 1-month change in systolic BP, the effect of dapagliflozin on the primary endpoint was “minimally attenuated,” compared with the primary analysis, he said. That suggests the clinical benefits “did not significantly relate to the blood pressure–lowering effect” of the SGLT2 inhibitor.

In that analysis, the hazard ratio for CV death or worsening HF for dapagliflozin versus placebo was 0.85 (95% confidence interval, 0.75-0.96; P = .010). The HR had been 0.82 (95% CI, 0.73-0.92; P < .001) overall in the DELIVER primary analysis.

The current study doesn’t shed further light on the main SGLT2 inhibitor mechanism of clinical benefit in nondiabetics with HF, which remains a mystery.

“There is a diuretic effect, but it’s not incredibly robust,” Dr. Selvaraj observed. It may contribute to the drugs’ benefits, “but it’s definitely more than that – a lot more than that.”

DELIVER was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Selvaraj reported no relevant conflicts. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Fonarow has reported receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Cytokinetics, Edwards, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Salt pills for patients with acute decompensated heart failure?

Restriction of dietary salt to alleviate or prevent volume overload in patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is common hospital practice, but without a solid evidence base. A trial testing whether taking salt pills might have benefits for patients with ADHF undergoing intensive diuresis, therefore, may seem a bit counterintuitive.

In just such a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the approach made no difference to weight loss on diuresis, a proxy for volume reduction, or to serum creatinine levels in ADHF patients receiving high-dose intravenous diuretic therapy.

The patients consumed the extra salt during their intravenous therapy in the form of tablets providing 6 g sodium chloride daily on top of their hospital-provided, low-sodium meals.

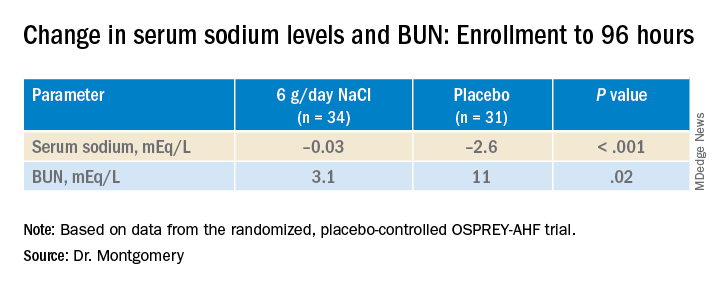

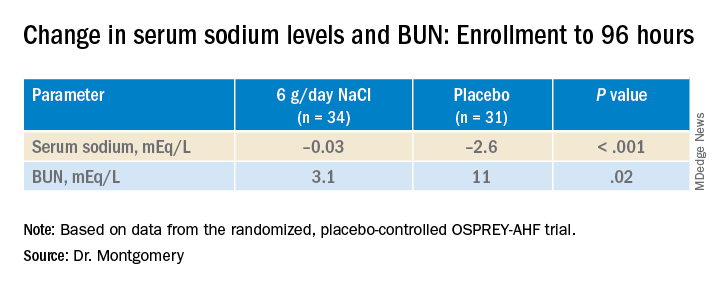

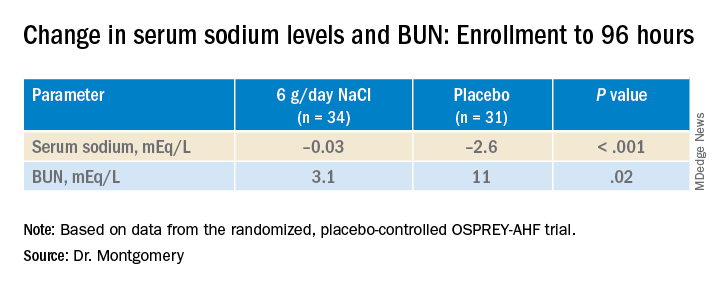

During that time, serum sodium levels remained stable for the 34 patients assigned to the salt tablets but dropped significantly in the 31 given placebo pills.

They lost about the same weight, averages of 4 kg and 4.6 kg (8.8-10 lb), respectively, and their urine output was also similar. Patients who took the salt tablets showed less of an increase in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at both 96 hours and at discharge.

The findings “challenge the routine practice of sodium chloride restriction in acute heart failure, something done thousands of times a day, millions of times a year,” Robert A. Montgomery, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said when presenting the study at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The trial, called OSPREY-AHF (Oral Sodium to Preserve Renal Efficiency in Acute Heart Failure), also may encourage a shift in ADHF management from a preoccupation with salt restriction to focus more on fighting fluid retention.

OSPREY-HF took on “an established practice that doesn’t have much high-quality evidentiary support,” one guided primarily by consensus and observational data, Montgomery said in an interview.

There are also potential downsides to dietary sodium restriction, including some that may complicate or block ADHF therapies.

“Low-sodium diets can be associated with decreased caloric intake and nutritional quality,” Dr. Montgomery observed. And observational studies suggest that “patients who are on a low sodium diet can develop increased neurohormonal activation. The kidney is not sensing salt, and so starts ramping up the hormones,” which promotes diuretic resistance.

But emerging evidence also suggests “that giving sodium chloride in the form of hypertonic saline can help patients who are diuretic resistant.” The intervention, which appears to attenuate the neurohormonal activation associated with high-dose intravenous diuretics, Dr. Montgomery noted, helped inspire the design of OSPREY-AHF.

Edema consists of “a gallon of water and a pinch of salt, so we really should stop being so salt-centric and think much more about water as the problem in decompensated heart failure,” said John G.F. Cleland, MD, PhD, during the question-and-answer period after Montgomery’s presentation. Dr. Cleland, of the University of Glasgow Institute of Health and Wellbeing, is not connected to OSPREY-AHF.

“I think that maybe we overinterpret how important salt is” as a focus of volume management in ADHF, offered David Lanfear, MD, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, who is also not part of the study.

OSPREY-AHF was well conducted but applies to a “very specific” clinical setting, Dr. Lanfear said in an interview. “These people are getting aggressive diuresis, a big dose and continuous infusion. It’s not everybody that has heart failure.”

Although the study was small, “I think it will fuel interest in this area and, probably, further investigation,” he said. The trial on its own won’t change practice, “but it will raise some eyebrows.”

The trial included patients with ADHF who have been “admitted to a cardiovascular medicine floor, not the intensive care unit” and were receiving at least 10 mg per hour of furosemide. It excluded any who were “hypernatremic or severely hyponatremic,” said Dr. Montgomery when presenting the study. They were required to have an initial estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of at least 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

The patients were randomly assigned double blind at a single center to receive tablets providing 2 g sodium chloride or placebo pills – 34 and 31 patients, respectively – three times daily during intravenous diuresis.

At 96 hours, the two groups showed no difference in change in creatinine levels or change in weight, both primary endpoints. Nor did they differ in urine output or change in eGFR. But serum sodium levels fell further, and BUN levels went up more in those given placebo.

The two groups showed no differences in hospital length of stay, use of renal replacement therapy at 90 days, ICU time during the index hospitalization, 30-day readmission, or 90-day mortality – although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical outcomes, Dr. Montgomery reported.

"We have patients who complain about their sodium-restricted diet, we have patients that have cachexia, who have a lot of complaints about provider-ordered meals and recommendations,” Dr. Montgomery explained in an interview.

Clinicians provide education and invest a lot of effort into getting patients with heart failure to start and maintain a low-sodium diet, he said. “But a low-sodium diet, in prior studies – and our study adds to this – is not a lever that actually seems to positively or adversely affect patients.”

Dr. Montgomery pointed to the recently published SODIUM-HF trial comparing low-sodium and unrestricted-sodium diets in outpatients with heart failure. It saw no clinical benefit from the low-sodium intervention.

Until studies show, potentially, that sodium restriction in hospitalized patients with heart failure makes a clinical difference, Dr. Montgomery said, “I’d say we should invest our time in things that we know are the most helpful, like getting them on guideline-directed medical therapy, when instead we spend an enormous amount of time counseling on and enforcing dietary restriction.”

Support for this study was provided by Cleveland Clinic Heart Vascular and Thoracic Institute’s Wilson Grant and Kaufman Center for Heart Failure Treatment and Recovery Grant. Dr. Lanfear disclosed research support from SomaLogic and Lilly; consulting for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Martin Pharmaceuticals, and Amgen; and serving on advisory panels for Illumina and Cytokinetics. Dr. Montgomery and Dr. Cleland disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Restriction of dietary salt to alleviate or prevent volume overload in patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is common hospital practice, but without a solid evidence base. A trial testing whether taking salt pills might have benefits for patients with ADHF undergoing intensive diuresis, therefore, may seem a bit counterintuitive.

In just such a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the approach made no difference to weight loss on diuresis, a proxy for volume reduction, or to serum creatinine levels in ADHF patients receiving high-dose intravenous diuretic therapy.

The patients consumed the extra salt during their intravenous therapy in the form of tablets providing 6 g sodium chloride daily on top of their hospital-provided, low-sodium meals.

During that time, serum sodium levels remained stable for the 34 patients assigned to the salt tablets but dropped significantly in the 31 given placebo pills.

They lost about the same weight, averages of 4 kg and 4.6 kg (8.8-10 lb), respectively, and their urine output was also similar. Patients who took the salt tablets showed less of an increase in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at both 96 hours and at discharge.

The findings “challenge the routine practice of sodium chloride restriction in acute heart failure, something done thousands of times a day, millions of times a year,” Robert A. Montgomery, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said when presenting the study at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The trial, called OSPREY-AHF (Oral Sodium to Preserve Renal Efficiency in Acute Heart Failure), also may encourage a shift in ADHF management from a preoccupation with salt restriction to focus more on fighting fluid retention.

OSPREY-HF took on “an established practice that doesn’t have much high-quality evidentiary support,” one guided primarily by consensus and observational data, Montgomery said in an interview.

There are also potential downsides to dietary sodium restriction, including some that may complicate or block ADHF therapies.

“Low-sodium diets can be associated with decreased caloric intake and nutritional quality,” Dr. Montgomery observed. And observational studies suggest that “patients who are on a low sodium diet can develop increased neurohormonal activation. The kidney is not sensing salt, and so starts ramping up the hormones,” which promotes diuretic resistance.

But emerging evidence also suggests “that giving sodium chloride in the form of hypertonic saline can help patients who are diuretic resistant.” The intervention, which appears to attenuate the neurohormonal activation associated with high-dose intravenous diuretics, Dr. Montgomery noted, helped inspire the design of OSPREY-AHF.

Edema consists of “a gallon of water and a pinch of salt, so we really should stop being so salt-centric and think much more about water as the problem in decompensated heart failure,” said John G.F. Cleland, MD, PhD, during the question-and-answer period after Montgomery’s presentation. Dr. Cleland, of the University of Glasgow Institute of Health and Wellbeing, is not connected to OSPREY-AHF.

“I think that maybe we overinterpret how important salt is” as a focus of volume management in ADHF, offered David Lanfear, MD, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, who is also not part of the study.

OSPREY-AHF was well conducted but applies to a “very specific” clinical setting, Dr. Lanfear said in an interview. “These people are getting aggressive diuresis, a big dose and continuous infusion. It’s not everybody that has heart failure.”

Although the study was small, “I think it will fuel interest in this area and, probably, further investigation,” he said. The trial on its own won’t change practice, “but it will raise some eyebrows.”

The trial included patients with ADHF who have been “admitted to a cardiovascular medicine floor, not the intensive care unit” and were receiving at least 10 mg per hour of furosemide. It excluded any who were “hypernatremic or severely hyponatremic,” said Dr. Montgomery when presenting the study. They were required to have an initial estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of at least 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

The patients were randomly assigned double blind at a single center to receive tablets providing 2 g sodium chloride or placebo pills – 34 and 31 patients, respectively – three times daily during intravenous diuresis.

At 96 hours, the two groups showed no difference in change in creatinine levels or change in weight, both primary endpoints. Nor did they differ in urine output or change in eGFR. But serum sodium levels fell further, and BUN levels went up more in those given placebo.

The two groups showed no differences in hospital length of stay, use of renal replacement therapy at 90 days, ICU time during the index hospitalization, 30-day readmission, or 90-day mortality – although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical outcomes, Dr. Montgomery reported.

"We have patients who complain about their sodium-restricted diet, we have patients that have cachexia, who have a lot of complaints about provider-ordered meals and recommendations,” Dr. Montgomery explained in an interview.

Clinicians provide education and invest a lot of effort into getting patients with heart failure to start and maintain a low-sodium diet, he said. “But a low-sodium diet, in prior studies – and our study adds to this – is not a lever that actually seems to positively or adversely affect patients.”

Dr. Montgomery pointed to the recently published SODIUM-HF trial comparing low-sodium and unrestricted-sodium diets in outpatients with heart failure. It saw no clinical benefit from the low-sodium intervention.

Until studies show, potentially, that sodium restriction in hospitalized patients with heart failure makes a clinical difference, Dr. Montgomery said, “I’d say we should invest our time in things that we know are the most helpful, like getting them on guideline-directed medical therapy, when instead we spend an enormous amount of time counseling on and enforcing dietary restriction.”

Support for this study was provided by Cleveland Clinic Heart Vascular and Thoracic Institute’s Wilson Grant and Kaufman Center for Heart Failure Treatment and Recovery Grant. Dr. Lanfear disclosed research support from SomaLogic and Lilly; consulting for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Martin Pharmaceuticals, and Amgen; and serving on advisory panels for Illumina and Cytokinetics. Dr. Montgomery and Dr. Cleland disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Restriction of dietary salt to alleviate or prevent volume overload in patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is common hospital practice, but without a solid evidence base. A trial testing whether taking salt pills might have benefits for patients with ADHF undergoing intensive diuresis, therefore, may seem a bit counterintuitive.

In just such a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the approach made no difference to weight loss on diuresis, a proxy for volume reduction, or to serum creatinine levels in ADHF patients receiving high-dose intravenous diuretic therapy.

The patients consumed the extra salt during their intravenous therapy in the form of tablets providing 6 g sodium chloride daily on top of their hospital-provided, low-sodium meals.

During that time, serum sodium levels remained stable for the 34 patients assigned to the salt tablets but dropped significantly in the 31 given placebo pills.

They lost about the same weight, averages of 4 kg and 4.6 kg (8.8-10 lb), respectively, and their urine output was also similar. Patients who took the salt tablets showed less of an increase in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at both 96 hours and at discharge.

The findings “challenge the routine practice of sodium chloride restriction in acute heart failure, something done thousands of times a day, millions of times a year,” Robert A. Montgomery, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said when presenting the study at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The trial, called OSPREY-AHF (Oral Sodium to Preserve Renal Efficiency in Acute Heart Failure), also may encourage a shift in ADHF management from a preoccupation with salt restriction to focus more on fighting fluid retention.

OSPREY-HF took on “an established practice that doesn’t have much high-quality evidentiary support,” one guided primarily by consensus and observational data, Montgomery said in an interview.

There are also potential downsides to dietary sodium restriction, including some that may complicate or block ADHF therapies.

“Low-sodium diets can be associated with decreased caloric intake and nutritional quality,” Dr. Montgomery observed. And observational studies suggest that “patients who are on a low sodium diet can develop increased neurohormonal activation. The kidney is not sensing salt, and so starts ramping up the hormones,” which promotes diuretic resistance.

But emerging evidence also suggests “that giving sodium chloride in the form of hypertonic saline can help patients who are diuretic resistant.” The intervention, which appears to attenuate the neurohormonal activation associated with high-dose intravenous diuretics, Dr. Montgomery noted, helped inspire the design of OSPREY-AHF.

Edema consists of “a gallon of water and a pinch of salt, so we really should stop being so salt-centric and think much more about water as the problem in decompensated heart failure,” said John G.F. Cleland, MD, PhD, during the question-and-answer period after Montgomery’s presentation. Dr. Cleland, of the University of Glasgow Institute of Health and Wellbeing, is not connected to OSPREY-AHF.

“I think that maybe we overinterpret how important salt is” as a focus of volume management in ADHF, offered David Lanfear, MD, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, who is also not part of the study.

OSPREY-AHF was well conducted but applies to a “very specific” clinical setting, Dr. Lanfear said in an interview. “These people are getting aggressive diuresis, a big dose and continuous infusion. It’s not everybody that has heart failure.”

Although the study was small, “I think it will fuel interest in this area and, probably, further investigation,” he said. The trial on its own won’t change practice, “but it will raise some eyebrows.”

The trial included patients with ADHF who have been “admitted to a cardiovascular medicine floor, not the intensive care unit” and were receiving at least 10 mg per hour of furosemide. It excluded any who were “hypernatremic or severely hyponatremic,” said Dr. Montgomery when presenting the study. They were required to have an initial estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of at least 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

The patients were randomly assigned double blind at a single center to receive tablets providing 2 g sodium chloride or placebo pills – 34 and 31 patients, respectively – three times daily during intravenous diuresis.

At 96 hours, the two groups showed no difference in change in creatinine levels or change in weight, both primary endpoints. Nor did they differ in urine output or change in eGFR. But serum sodium levels fell further, and BUN levels went up more in those given placebo.

The two groups showed no differences in hospital length of stay, use of renal replacement therapy at 90 days, ICU time during the index hospitalization, 30-day readmission, or 90-day mortality – although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical outcomes, Dr. Montgomery reported.

"We have patients who complain about their sodium-restricted diet, we have patients that have cachexia, who have a lot of complaints about provider-ordered meals and recommendations,” Dr. Montgomery explained in an interview.

Clinicians provide education and invest a lot of effort into getting patients with heart failure to start and maintain a low-sodium diet, he said. “But a low-sodium diet, in prior studies – and our study adds to this – is not a lever that actually seems to positively or adversely affect patients.”

Dr. Montgomery pointed to the recently published SODIUM-HF trial comparing low-sodium and unrestricted-sodium diets in outpatients with heart failure. It saw no clinical benefit from the low-sodium intervention.

Until studies show, potentially, that sodium restriction in hospitalized patients with heart failure makes a clinical difference, Dr. Montgomery said, “I’d say we should invest our time in things that we know are the most helpful, like getting them on guideline-directed medical therapy, when instead we spend an enormous amount of time counseling on and enforcing dietary restriction.”

Support for this study was provided by Cleveland Clinic Heart Vascular and Thoracic Institute’s Wilson Grant and Kaufman Center for Heart Failure Treatment and Recovery Grant. Dr. Lanfear disclosed research support from SomaLogic and Lilly; consulting for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Martin Pharmaceuticals, and Amgen; and serving on advisory panels for Illumina and Cytokinetics. Dr. Montgomery and Dr. Cleland disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HFSA 2022