User login

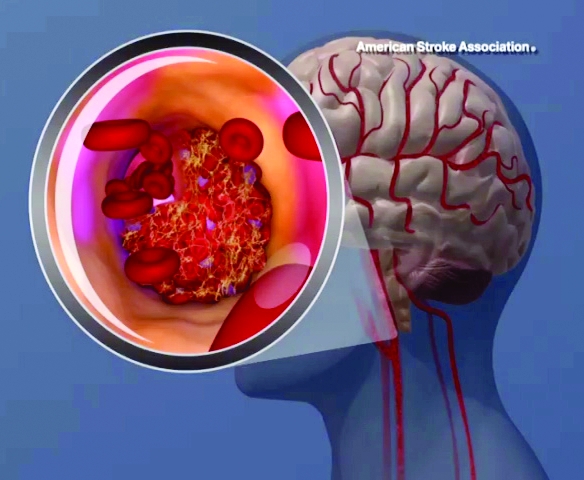

High levels of lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] and LPA genotypes were linked to increased ischemic stroke risk in a recent large, contemporary general population study, investigators are reporting in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Anne Langsted, MD, with Copenhagen University Hospital and the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, and her co-researchers evaluated the impact of high Lp(a) levels in a large contemporary cohort of 49,699 individuals in the Copenhagen General Population Study, and another 10,813 individuals in the Copenhagen City Heart Study.

Measurements assessed included plasma lipoprotein(a) levels and carrier or noncarrier status for LPA rs10455872. The endpoint of ischemic stroke was ascertained from Danish national health registries and confirmed by physicians.

Although risk estimates were less pronounced than what was reported before regarding the link between Lp(a) for ischemic heart disease and aortic valve stenosis, the risk of stroke was increased by a factor of 1.6 among individuals with high Lp(a) levels as compared to those with lower levels, the investigators said.

Compared with noncarriers of LPA rs1045572, the hazard ratio for ischemic stroke was 1.23 for carriers of LPA rs1045572, which was associated with high levels plasma lipoprotein(a) levels, according to the researchers.

“Our results indicate a causal association of Lp(a) with risk of ischemic stroke, and emphasize the need for randomized, controlled clinical trials on the effect of Lp(a)-lowering to prevent cardiovascular disease including ischemic stroke,” About 20% of the general population have high Lp(a) levels, and some individuals have extremely high levels, Dr. Langsted and co-authors said in their report.

Interest in Lp(a) as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease has been reignited following large studies showing that high Lp(a) levels were linked to increased risk of myocardial infarction and aortic valve stenosis, according to the investigators.

However, results of various studies are conflicting as to whether high Lp(a) levels increase risk of hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke, they said.

Both cohort studies used in the analysis were supported by sources in Denmark including the Danish Medical Research Council and Copenhagen University Hospital. Dr. Langsted had no disclosures. One co-author reported disclosures related to Akcea, Amgen, Sanofi, Regeneron, and AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Langsted A, et al. JACC 2019;74[1]: 54-66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.524

This study linking high lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] levels to stroke risk, taken together with previous research, provide a sound basis to routinely perform one-time screening so that individuals with inherited high levels can try to avoid adverse cardiovascular outcomes, according to Christie M. Ballantyne, MD.

“As someone in the dual role of preventive cardiologist and patient with a strong family history of cardiovascular disease, I think that we have sufficient evidence that high Lp(a) is strongly associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and aortic valve stenosis,” Dr. Ballantyne wrote in an editorial comment on the study.

Evidence is now “overwhelming” that high Lp(a) is linked to myocardial infarction and stroke, and it’s known that statins and aspirin reduce risk of these outcomes, he said in the commentary.

Despite that, scientific statements do not recommend routine Lp(a) testing due to a lack of clinical trials evidence; as a result, clinical trials are not including Lp(a) as a routine measurement: “We thus have a loop of futility—lack of routine measurement leads to lack of data,” he said.

This most recent study from Langsted and colleagues demonstrates that high Lp(a) levels, and genetic variants associated with Lp(a), are associated with increased ischemic stroke risk. “The genetics strongly supported that high Lp(a) levels were in the causal pathway for ischemic stroke and coronary heart disease,” Dr. Ballantyne said.

One major strength and weakness of the study is its large and relatively homogeneous European population—that bolstered the genetic analyses, but also means the data can’t be extrapolated to other populations, such as Africans and East Asians, who have higher stroke rates compared with Europeans, Dr. Ballantyne said.

Dr. Ballantyne is with the Department of Medicine and Center for Cardiometabolic Disease Prevention, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex. His editorial comment appears in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (2019;74[1]:67-9. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.05.029 . Dr. Ballantyne reported disclosures related to Akcea, Amgen, and Novartis.

This study linking high lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] levels to stroke risk, taken together with previous research, provide a sound basis to routinely perform one-time screening so that individuals with inherited high levels can try to avoid adverse cardiovascular outcomes, according to Christie M. Ballantyne, MD.

“As someone in the dual role of preventive cardiologist and patient with a strong family history of cardiovascular disease, I think that we have sufficient evidence that high Lp(a) is strongly associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and aortic valve stenosis,” Dr. Ballantyne wrote in an editorial comment on the study.

Evidence is now “overwhelming” that high Lp(a) is linked to myocardial infarction and stroke, and it’s known that statins and aspirin reduce risk of these outcomes, he said in the commentary.

Despite that, scientific statements do not recommend routine Lp(a) testing due to a lack of clinical trials evidence; as a result, clinical trials are not including Lp(a) as a routine measurement: “We thus have a loop of futility—lack of routine measurement leads to lack of data,” he said.

This most recent study from Langsted and colleagues demonstrates that high Lp(a) levels, and genetic variants associated with Lp(a), are associated with increased ischemic stroke risk. “The genetics strongly supported that high Lp(a) levels were in the causal pathway for ischemic stroke and coronary heart disease,” Dr. Ballantyne said.

One major strength and weakness of the study is its large and relatively homogeneous European population—that bolstered the genetic analyses, but also means the data can’t be extrapolated to other populations, such as Africans and East Asians, who have higher stroke rates compared with Europeans, Dr. Ballantyne said.

Dr. Ballantyne is with the Department of Medicine and Center for Cardiometabolic Disease Prevention, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex. His editorial comment appears in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (2019;74[1]:67-9. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.05.029 . Dr. Ballantyne reported disclosures related to Akcea, Amgen, and Novartis.

This study linking high lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] levels to stroke risk, taken together with previous research, provide a sound basis to routinely perform one-time screening so that individuals with inherited high levels can try to avoid adverse cardiovascular outcomes, according to Christie M. Ballantyne, MD.

“As someone in the dual role of preventive cardiologist and patient with a strong family history of cardiovascular disease, I think that we have sufficient evidence that high Lp(a) is strongly associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and aortic valve stenosis,” Dr. Ballantyne wrote in an editorial comment on the study.

Evidence is now “overwhelming” that high Lp(a) is linked to myocardial infarction and stroke, and it’s known that statins and aspirin reduce risk of these outcomes, he said in the commentary.

Despite that, scientific statements do not recommend routine Lp(a) testing due to a lack of clinical trials evidence; as a result, clinical trials are not including Lp(a) as a routine measurement: “We thus have a loop of futility—lack of routine measurement leads to lack of data,” he said.

This most recent study from Langsted and colleagues demonstrates that high Lp(a) levels, and genetic variants associated with Lp(a), are associated with increased ischemic stroke risk. “The genetics strongly supported that high Lp(a) levels were in the causal pathway for ischemic stroke and coronary heart disease,” Dr. Ballantyne said.

One major strength and weakness of the study is its large and relatively homogeneous European population—that bolstered the genetic analyses, but also means the data can’t be extrapolated to other populations, such as Africans and East Asians, who have higher stroke rates compared with Europeans, Dr. Ballantyne said.

Dr. Ballantyne is with the Department of Medicine and Center for Cardiometabolic Disease Prevention, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex. His editorial comment appears in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (2019;74[1]:67-9. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.05.029 . Dr. Ballantyne reported disclosures related to Akcea, Amgen, and Novartis.

High levels of lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] and LPA genotypes were linked to increased ischemic stroke risk in a recent large, contemporary general population study, investigators are reporting in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Anne Langsted, MD, with Copenhagen University Hospital and the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, and her co-researchers evaluated the impact of high Lp(a) levels in a large contemporary cohort of 49,699 individuals in the Copenhagen General Population Study, and another 10,813 individuals in the Copenhagen City Heart Study.

Measurements assessed included plasma lipoprotein(a) levels and carrier or noncarrier status for LPA rs10455872. The endpoint of ischemic stroke was ascertained from Danish national health registries and confirmed by physicians.

Although risk estimates were less pronounced than what was reported before regarding the link between Lp(a) for ischemic heart disease and aortic valve stenosis, the risk of stroke was increased by a factor of 1.6 among individuals with high Lp(a) levels as compared to those with lower levels, the investigators said.

Compared with noncarriers of LPA rs1045572, the hazard ratio for ischemic stroke was 1.23 for carriers of LPA rs1045572, which was associated with high levels plasma lipoprotein(a) levels, according to the researchers.

“Our results indicate a causal association of Lp(a) with risk of ischemic stroke, and emphasize the need for randomized, controlled clinical trials on the effect of Lp(a)-lowering to prevent cardiovascular disease including ischemic stroke,” About 20% of the general population have high Lp(a) levels, and some individuals have extremely high levels, Dr. Langsted and co-authors said in their report.

Interest in Lp(a) as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease has been reignited following large studies showing that high Lp(a) levels were linked to increased risk of myocardial infarction and aortic valve stenosis, according to the investigators.

However, results of various studies are conflicting as to whether high Lp(a) levels increase risk of hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke, they said.

Both cohort studies used in the analysis were supported by sources in Denmark including the Danish Medical Research Council and Copenhagen University Hospital. Dr. Langsted had no disclosures. One co-author reported disclosures related to Akcea, Amgen, Sanofi, Regeneron, and AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Langsted A, et al. JACC 2019;74[1]: 54-66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.524

High levels of lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] and LPA genotypes were linked to increased ischemic stroke risk in a recent large, contemporary general population study, investigators are reporting in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Anne Langsted, MD, with Copenhagen University Hospital and the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, and her co-researchers evaluated the impact of high Lp(a) levels in a large contemporary cohort of 49,699 individuals in the Copenhagen General Population Study, and another 10,813 individuals in the Copenhagen City Heart Study.

Measurements assessed included plasma lipoprotein(a) levels and carrier or noncarrier status for LPA rs10455872. The endpoint of ischemic stroke was ascertained from Danish national health registries and confirmed by physicians.

Although risk estimates were less pronounced than what was reported before regarding the link between Lp(a) for ischemic heart disease and aortic valve stenosis, the risk of stroke was increased by a factor of 1.6 among individuals with high Lp(a) levels as compared to those with lower levels, the investigators said.

Compared with noncarriers of LPA rs1045572, the hazard ratio for ischemic stroke was 1.23 for carriers of LPA rs1045572, which was associated with high levels plasma lipoprotein(a) levels, according to the researchers.

“Our results indicate a causal association of Lp(a) with risk of ischemic stroke, and emphasize the need for randomized, controlled clinical trials on the effect of Lp(a)-lowering to prevent cardiovascular disease including ischemic stroke,” About 20% of the general population have high Lp(a) levels, and some individuals have extremely high levels, Dr. Langsted and co-authors said in their report.

Interest in Lp(a) as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease has been reignited following large studies showing that high Lp(a) levels were linked to increased risk of myocardial infarction and aortic valve stenosis, according to the investigators.

However, results of various studies are conflicting as to whether high Lp(a) levels increase risk of hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke, they said.

Both cohort studies used in the analysis were supported by sources in Denmark including the Danish Medical Research Council and Copenhagen University Hospital. Dr. Langsted had no disclosures. One co-author reported disclosures related to Akcea, Amgen, Sanofi, Regeneron, and AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Langsted A, et al. JACC 2019;74[1]: 54-66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.524

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Stroke risk was 1.6X higher with high Lp(a) levels.

Study details: Analysis of 49,699 individuals in the Copenhagen General Population Study, and 10,813 individuals in the Copenhagen City Heart Study.

Disclosures: Both studies were supported by the sources in Denmark including the Danish Medical Research Council and Copenhagen University Hospital. Dr. Langsted had no disclosures.

Source: Langsted A, et al. JACC 2019;74[1]: 54-66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.524