User login

The advent of liquid biopsies targeting genetic mutations in solid tumors is a major milestone in the field of precision oncology.1 Conventional methods of obtaining tissue for molecular studies are limited by sample size and often do not represent the entire bulk of the tumor.2 This newer minimally invasive, revolutionary technique analyzes circulating cell-free DNA carrying tumor-specific alterations (circulating tumor DNA [ctDNA]) in peripheral blood and detects signature genomic alterations.1 Tp53 mutations have been reported in 25 to 40% of prostatic cancers and > 50% of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC), being more common in late-stage and hormone refractory prostate cancers.3,4 Tp53 mutation has been found to be associated with poor prognosis and increased germline mutations.5

The veteran patient population has distinct demographic characteristics that make veterans more vulnerable to genetic mutations and malignancies, including risk of exposure to Agent Orange, smoking, substance abuse, and asbestos. This area is understudied and extremely sparse in the literature for frequency of genetic mutations, risk factors in solid malignancies occurring in the veteran patient population, and the clinical impact of these risk factors. We herein present a quality assurance study for the utility of liquid biopsies regarding the frequency of DNA damage repair (DDR) gene, Tp53, and androgen receptor (AR) mutations. The clinical impact in advanced lung and prostate cancers in the veteran patient population and frequency are the quality assurance observations that are the study endpoints.

Methods

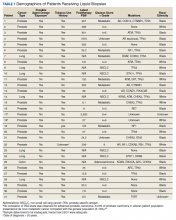

We reviewed for quality assurance documentation from the Foundation Medicine (www.foundationmedicine.com) cancer biomarker tests on liquid biopsies performed at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Veteran Affairs Medical Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania from May 2019 to April 15, 2020. All biopsies were performed on cancers with biochemical, imaging or tissue evidence of advanced tumor progression. The testing was performed on advanced solid malignancies, including NSCLC, prostate adenocarcinoma, and metastatic colon cancer. Statistical data for adequacy; cases with notable mutations; frequency; and type of mutations of AR, DDR, and Tp53 were noted. General and specific risk factors associated with the veteran patient population were studied and matched with the type of mutations (Table 1).

Results

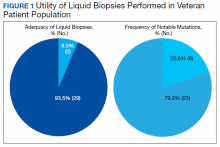

Thirty-one liquid biopsies were performed over this period—23 for prostate cancer, 7 for patients with lung cancer patients, and 1 for a patient with colon cancer. Of 31 cases, sensitivity/adequacy of liquid biopsy for genetic mutation was detected in 29 (93.5%) cases (Figure 1). Two inadequate biopsies (both from patients with prostate cancer) were excluded from the study, leaving 29 liquid biopsies with adequate ctDNA for analysis that were considered for further statistical purpose—21 prostate, 7 lung, and 1 colon cancer.

Multiple (common and different) genetic mutations were identified; however, our study subcategorized the mutations into the those that were related to prostate cancer, lung cancer, and some common mutations that occur in both cancers. Only the significant ones will be discussed in this review and equivocal result for AR is excluded from this study. Of the 21 prostate cancers, 4 (19.0%) had directed the targeted therapy to driver mutation (AR being most common in prostate cancer), while KRAS mutation, which was more common in lung cancer, was detected in 2/7 (28.6%) lung cancers. Mutations common to both cancer types were DDR gene mutations, which is a broad name for numerous genes including CDK12, ATM, and CHEK2.

Of all cases irrespective of the cancer type, 23/29 (79.3%) showed notable mutations. DDR gene mutations were found in 6 of 21 (28.5%) patients with prostate cancer and 8 of 23 (34.7%) patients with advanced prostate and lung cancers, indicating poor outcome and possible resistance to the current therapy. Of 23 patients showing mutations irrespective of the cancer type, 15 (65.2%) harbored Tp53 mutations, which is much more frequent in veteran patient population when compared with the literature. Fifteen of the 31 (48.4%) total patients were Vietnam War-era veterans who were potentially exposed to Agent Orange and 20 (64.5%) patients who were not Vietnam War-era veterans had a history that included smoking (Figure 2).

Discussion

The veteran patient population is a unique cohort due to its distinct demographic characteristics with a high volume of cancer cases diagnosed each year. According to data from VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR), the most frequently diagnosed cancers are prostate (29%) and lung (18%).6

Liquid biopsy is a novel, promising technology that uses ctDNA and circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood for detecting genetic alterations through next generation sequencing.7-9 The advent of this minimally invasive, revolutionary technology has been a breakthrough in the field of precision oncology for prognosis, to monitor treatment response or resistance to therapy and further personalize cancer therapy.9,10

Comprehensive genomic profiling by liquid biopsy has many advantages over the molecular studies performed on tissue biopsy. Due to the tumor heterogeneity, tissue samples may not represent the full profile of the tumor genomics of cancer, while liquid biopsy has full presentation of the disease.11,12 Many times, tissue biopsy may be limited by a sample size that precludes full genetic profiling in addition to higher total cost, potential technical issues during processing, and possible side effects of the biopsy procedure.7,13 Additionally, as the tumor progresses, new driver mutations other than the ones previously detected on the primary tissue may emerge, which can confer resistance to the existing therapy.7,13

Advanced prostatic and lung carcinomas with biochemical, distant organ, or bony progression harbor unique signature genetic mutations indicating poor prognosis, lack of response or resistance to the existing therapy, and high risk of relapse.14,15 Some of the unique characteristics of the veteran patient population include a more aged patient population multiple comorbidities, higher frequency of > 1 type of cancer, advanced cancer stage at presentation, and specific risks factors such as exposure to Agent Orange in veterans who served during the Vietnam War era.16,17 We studied the utility of liquid biopsy in cancer care, including type and incidence of genomic alterations associated with advanced prostate and lung cancers, in this unique patient population.

The amount of cell-free DNA (cfDNA), also known as ctDNA varies widely in cancer patients. Some of the factors associated with low concentration of cfDNA are disease stage, intervening therapy, proliferation rates, and tumor vascularization.18,19 In the peripheral blood, of the total cfDNA, fractions of cfDNA varies from 0.01 to 90%.18,19 All samples containing ≥ 20 ng cfDNA (20 - 100 ng) were subjected to the hybrid capture-based NGS FoundationACT assay.20 In our study, 2 specimens did not meet the minimum criteria of adequacy (20 ng cfDNA); however, the overall adequacy rate for the detection of mutation, irrespective of the cancer type was 29 of 31 (93.5%) with only 2 inadequate samples. This rate is higher than the rate reported in the literature, which is about 70%.20

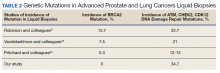

Significant differences were encountered in the incidence of DNA damage repair genes including Tp53 mutations when compared with those in the general patient population (Table 2). According to recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, all prostate cancers should be screened for DDR gene mutations as these genes are common in aggressive prostate cancers and strongly associated with poor outcomes and shortened survival. Due to relatively high frequency of DDR gene mutations in advanced prostatic cancers, liquid biopsy in patients with these advanced stage prostate cancers may be a useful tool in clinical decision making and exploring targeted therapy.20

Mutations in BRCA2, ATM, CDK12, and CHEK2 (DDR gene family) are common. Incidence of ATM and CDK12 mutations in the literature is 3 to 6% of cases.21 Of 21 liquid biopsies of advanced prostate cancer patients, we found combined DDR gene mutation of ATM, CHEK2, and CDK12 genes in 6 (28.5%) cases, which is substantially higher than the 3 to 6% rate reported in the literature.21-24 Of the 23 patients who had notable mutations in our liquid biopsies, including both advanced prostate and lung cancer cases, 8 (34.7%) also showed mutation of the genes of DDR family. Our study did not show BRCA2 mutation, which is otherwise common in the literature.

We also evaluated the frequency of the most commonly occurring genetic mutations, Tp53 in advanced solid malignancies, especially advanced prostate and NSCLC. Previous studies have reported Tp53 mutation in association with risk factors (carcinogens) of cancer and have been a surrogate marker of poor survival or lack of response of therapy.25 Knowledge of Tp53 mutation is crucial for closer disease monitoring, preparing the patient for rapid progression, and encouraging the physician to prepare future lines of therapy.25-27 Although Tp53 mutation varies with histologic type and tissue of origin, Beltran and colleagues reported it in 30 to 40% of tumors, while Robles and colleagues reported about 40 to 42% incidence.25,27

Our study showed notable mutations in 23 of 29 adequate cases. Further, our study showed a high frequency of mutated Tp53 in 65.2% of combined advanced prostate and NSCLC cases. We then correlated cases of Vietnam War-era veterans with risk potential of Agent Orange exposure and Tp53 mutation. We found 7 of 15 Vietnam War-era veterans were positive for Tp53 mutations irrespective of the cancer type. The high incidence of Tp53 mutations in advanced prostate and lung carcinomas in the veteran patient population makes this tumor marker an aspiration not only as a surrogate of aggressive disease and tumor progression, but also as a key marker for targeted therapy in advanced prostate and lung cancers with loss of Tp53 function (Figure 3).

Mutations and amplifications in the AR gene are fundamental to progression of prostate cancer associated with advanced, hormone-refractory prostate cancer with the potential for targeted therapy with AR inhibitors. In our study, AR amplification was detected in 4 of 21 (19%) advanced prostate cancer cases, which is significantly lower than the 30 to 50% previously reported in the literature.28-32 Neither AR amplification or mutation was noted in advanced NSCLC in our study as previously reported in literature by Brennan and colleagues and Wang and colleagues.33-35 This is significant as it provides a pathway for future studies to focus on additional driver mutations for targeted therapies in advanced prostate carcinoma. To date, AR gene mutation does not play a role for personalized therapy in advanced NSCLC. Perhaps, a large cohort study with longitudinal analysis is needed for absolutely ruling out the possibility of personalized medicine in advanced lung cancer using this biomarker.

Conclusions

Liquid biopsy successfully provides precision-based oncology and information for decision making in this unique population of veterans. Difference in frequency of the genetic mutations in this cohort can provide future insight into disease progression, lack of response, and mechanism of resistance to the implemented therapy. Future studies focused on this veteran patient population are needed for developing targeted therapies and patient tailored oncologic therapy. ctDNA has a high potential for monitoring clinically relevant cancer-related genetic and epigenetic modifications for discovering more detailed information on the tumor characterization. Although larger cohort trial with longitudinal analyses are needed, high prevalence of DDR gene and Tp53 mutation in our study instills promising hope for therapeutic interventions in this unique cohort.

The minimally invasive liquid biopsy shows a great promise as both diagnostic and prognostic tool in the personalized clinical management of advanced prostate, and NSCLC in the veteran patient population with unique demographic characteristics. De novo metastatic prostate cancer is more common in veterans when compared with the general population, and therefore veterans may benefit by liquid biopsy. Differences in the frequency of genetic mutations (DDR, TP53, AR) in this cohort provides valuable information for disease progression, lack of response, mechanism of resistance to the implemented therapy and clinical decision making. Precision oncology can be further tailored for this cohort by focusing on DNA repair genes and Tp53 mutations for future targeted therapy.

1

9

16. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review the Health Effects in Vietnam Veterans of Exposure to Herbicides (Fourth Biennial Update). Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2002. National Academies Press (US); 2003.

17. Eibner C, Krull H, Brown KM, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique health care needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Rand Health Q. 2016;5(4):13. Published 2016 May 9.

18. Saarenheimo J, Eigeliene N, Andersen H, Tiirola M, Jekunen A. The value of liquid biopsies for guiding therapy decisions in non-small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:129. Published 2019 Mar 5.doi:10.3389/fonc.2019.00129

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31. Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Luber B, et al. Clinical significance of androgen receptor splice variant-7 mRNA detection in circulating tumor cells of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with first- and second-line abiraterone and enzalutamide. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(19):2149-2156. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1961

32

33. Jung A, Kirchner T. Liquid biopsy in tumor genetic diagnosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(10):169-174. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2018.0169

34. Brennan S, Wang AR, Beyer H, et al. Androgen receptor as a potential target in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77(Suppl13): abstract nr 4121. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.AM2017-4121

35. Wang AR, Beyer H, Brennan S, et al. Androgen receptor drives differential gene expression in KRAS-mediated non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78(Suppl 13): abstract nr 3946. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.AM2018-3946

The advent of liquid biopsies targeting genetic mutations in solid tumors is a major milestone in the field of precision oncology.1 Conventional methods of obtaining tissue for molecular studies are limited by sample size and often do not represent the entire bulk of the tumor.2 This newer minimally invasive, revolutionary technique analyzes circulating cell-free DNA carrying tumor-specific alterations (circulating tumor DNA [ctDNA]) in peripheral blood and detects signature genomic alterations.1 Tp53 mutations have been reported in 25 to 40% of prostatic cancers and > 50% of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC), being more common in late-stage and hormone refractory prostate cancers.3,4 Tp53 mutation has been found to be associated with poor prognosis and increased germline mutations.5

The veteran patient population has distinct demographic characteristics that make veterans more vulnerable to genetic mutations and malignancies, including risk of exposure to Agent Orange, smoking, substance abuse, and asbestos. This area is understudied and extremely sparse in the literature for frequency of genetic mutations, risk factors in solid malignancies occurring in the veteran patient population, and the clinical impact of these risk factors. We herein present a quality assurance study for the utility of liquid biopsies regarding the frequency of DNA damage repair (DDR) gene, Tp53, and androgen receptor (AR) mutations. The clinical impact in advanced lung and prostate cancers in the veteran patient population and frequency are the quality assurance observations that are the study endpoints.

Methods

We reviewed for quality assurance documentation from the Foundation Medicine (www.foundationmedicine.com) cancer biomarker tests on liquid biopsies performed at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Veteran Affairs Medical Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania from May 2019 to April 15, 2020. All biopsies were performed on cancers with biochemical, imaging or tissue evidence of advanced tumor progression. The testing was performed on advanced solid malignancies, including NSCLC, prostate adenocarcinoma, and metastatic colon cancer. Statistical data for adequacy; cases with notable mutations; frequency; and type of mutations of AR, DDR, and Tp53 were noted. General and specific risk factors associated with the veteran patient population were studied and matched with the type of mutations (Table 1).

Results

Thirty-one liquid biopsies were performed over this period—23 for prostate cancer, 7 for patients with lung cancer patients, and 1 for a patient with colon cancer. Of 31 cases, sensitivity/adequacy of liquid biopsy for genetic mutation was detected in 29 (93.5%) cases (Figure 1). Two inadequate biopsies (both from patients with prostate cancer) were excluded from the study, leaving 29 liquid biopsies with adequate ctDNA for analysis that were considered for further statistical purpose—21 prostate, 7 lung, and 1 colon cancer.

Multiple (common and different) genetic mutations were identified; however, our study subcategorized the mutations into the those that were related to prostate cancer, lung cancer, and some common mutations that occur in both cancers. Only the significant ones will be discussed in this review and equivocal result for AR is excluded from this study. Of the 21 prostate cancers, 4 (19.0%) had directed the targeted therapy to driver mutation (AR being most common in prostate cancer), while KRAS mutation, which was more common in lung cancer, was detected in 2/7 (28.6%) lung cancers. Mutations common to both cancer types were DDR gene mutations, which is a broad name for numerous genes including CDK12, ATM, and CHEK2.

Of all cases irrespective of the cancer type, 23/29 (79.3%) showed notable mutations. DDR gene mutations were found in 6 of 21 (28.5%) patients with prostate cancer and 8 of 23 (34.7%) patients with advanced prostate and lung cancers, indicating poor outcome and possible resistance to the current therapy. Of 23 patients showing mutations irrespective of the cancer type, 15 (65.2%) harbored Tp53 mutations, which is much more frequent in veteran patient population when compared with the literature. Fifteen of the 31 (48.4%) total patients were Vietnam War-era veterans who were potentially exposed to Agent Orange and 20 (64.5%) patients who were not Vietnam War-era veterans had a history that included smoking (Figure 2).

Discussion

The veteran patient population is a unique cohort due to its distinct demographic characteristics with a high volume of cancer cases diagnosed each year. According to data from VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR), the most frequently diagnosed cancers are prostate (29%) and lung (18%).6

Liquid biopsy is a novel, promising technology that uses ctDNA and circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood for detecting genetic alterations through next generation sequencing.7-9 The advent of this minimally invasive, revolutionary technology has been a breakthrough in the field of precision oncology for prognosis, to monitor treatment response or resistance to therapy and further personalize cancer therapy.9,10

Comprehensive genomic profiling by liquid biopsy has many advantages over the molecular studies performed on tissue biopsy. Due to the tumor heterogeneity, tissue samples may not represent the full profile of the tumor genomics of cancer, while liquid biopsy has full presentation of the disease.11,12 Many times, tissue biopsy may be limited by a sample size that precludes full genetic profiling in addition to higher total cost, potential technical issues during processing, and possible side effects of the biopsy procedure.7,13 Additionally, as the tumor progresses, new driver mutations other than the ones previously detected on the primary tissue may emerge, which can confer resistance to the existing therapy.7,13

Advanced prostatic and lung carcinomas with biochemical, distant organ, or bony progression harbor unique signature genetic mutations indicating poor prognosis, lack of response or resistance to the existing therapy, and high risk of relapse.14,15 Some of the unique characteristics of the veteran patient population include a more aged patient population multiple comorbidities, higher frequency of > 1 type of cancer, advanced cancer stage at presentation, and specific risks factors such as exposure to Agent Orange in veterans who served during the Vietnam War era.16,17 We studied the utility of liquid biopsy in cancer care, including type and incidence of genomic alterations associated with advanced prostate and lung cancers, in this unique patient population.

The amount of cell-free DNA (cfDNA), also known as ctDNA varies widely in cancer patients. Some of the factors associated with low concentration of cfDNA are disease stage, intervening therapy, proliferation rates, and tumor vascularization.18,19 In the peripheral blood, of the total cfDNA, fractions of cfDNA varies from 0.01 to 90%.18,19 All samples containing ≥ 20 ng cfDNA (20 - 100 ng) were subjected to the hybrid capture-based NGS FoundationACT assay.20 In our study, 2 specimens did not meet the minimum criteria of adequacy (20 ng cfDNA); however, the overall adequacy rate for the detection of mutation, irrespective of the cancer type was 29 of 31 (93.5%) with only 2 inadequate samples. This rate is higher than the rate reported in the literature, which is about 70%.20

Significant differences were encountered in the incidence of DNA damage repair genes including Tp53 mutations when compared with those in the general patient population (Table 2). According to recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, all prostate cancers should be screened for DDR gene mutations as these genes are common in aggressive prostate cancers and strongly associated with poor outcomes and shortened survival. Due to relatively high frequency of DDR gene mutations in advanced prostatic cancers, liquid biopsy in patients with these advanced stage prostate cancers may be a useful tool in clinical decision making and exploring targeted therapy.20

Mutations in BRCA2, ATM, CDK12, and CHEK2 (DDR gene family) are common. Incidence of ATM and CDK12 mutations in the literature is 3 to 6% of cases.21 Of 21 liquid biopsies of advanced prostate cancer patients, we found combined DDR gene mutation of ATM, CHEK2, and CDK12 genes in 6 (28.5%) cases, which is substantially higher than the 3 to 6% rate reported in the literature.21-24 Of the 23 patients who had notable mutations in our liquid biopsies, including both advanced prostate and lung cancer cases, 8 (34.7%) also showed mutation of the genes of DDR family. Our study did not show BRCA2 mutation, which is otherwise common in the literature.

We also evaluated the frequency of the most commonly occurring genetic mutations, Tp53 in advanced solid malignancies, especially advanced prostate and NSCLC. Previous studies have reported Tp53 mutation in association with risk factors (carcinogens) of cancer and have been a surrogate marker of poor survival or lack of response of therapy.25 Knowledge of Tp53 mutation is crucial for closer disease monitoring, preparing the patient for rapid progression, and encouraging the physician to prepare future lines of therapy.25-27 Although Tp53 mutation varies with histologic type and tissue of origin, Beltran and colleagues reported it in 30 to 40% of tumors, while Robles and colleagues reported about 40 to 42% incidence.25,27

Our study showed notable mutations in 23 of 29 adequate cases. Further, our study showed a high frequency of mutated Tp53 in 65.2% of combined advanced prostate and NSCLC cases. We then correlated cases of Vietnam War-era veterans with risk potential of Agent Orange exposure and Tp53 mutation. We found 7 of 15 Vietnam War-era veterans were positive for Tp53 mutations irrespective of the cancer type. The high incidence of Tp53 mutations in advanced prostate and lung carcinomas in the veteran patient population makes this tumor marker an aspiration not only as a surrogate of aggressive disease and tumor progression, but also as a key marker for targeted therapy in advanced prostate and lung cancers with loss of Tp53 function (Figure 3).

Mutations and amplifications in the AR gene are fundamental to progression of prostate cancer associated with advanced, hormone-refractory prostate cancer with the potential for targeted therapy with AR inhibitors. In our study, AR amplification was detected in 4 of 21 (19%) advanced prostate cancer cases, which is significantly lower than the 30 to 50% previously reported in the literature.28-32 Neither AR amplification or mutation was noted in advanced NSCLC in our study as previously reported in literature by Brennan and colleagues and Wang and colleagues.33-35 This is significant as it provides a pathway for future studies to focus on additional driver mutations for targeted therapies in advanced prostate carcinoma. To date, AR gene mutation does not play a role for personalized therapy in advanced NSCLC. Perhaps, a large cohort study with longitudinal analysis is needed for absolutely ruling out the possibility of personalized medicine in advanced lung cancer using this biomarker.

Conclusions

Liquid biopsy successfully provides precision-based oncology and information for decision making in this unique population of veterans. Difference in frequency of the genetic mutations in this cohort can provide future insight into disease progression, lack of response, and mechanism of resistance to the implemented therapy. Future studies focused on this veteran patient population are needed for developing targeted therapies and patient tailored oncologic therapy. ctDNA has a high potential for monitoring clinically relevant cancer-related genetic and epigenetic modifications for discovering more detailed information on the tumor characterization. Although larger cohort trial with longitudinal analyses are needed, high prevalence of DDR gene and Tp53 mutation in our study instills promising hope for therapeutic interventions in this unique cohort.

The minimally invasive liquid biopsy shows a great promise as both diagnostic and prognostic tool in the personalized clinical management of advanced prostate, and NSCLC in the veteran patient population with unique demographic characteristics. De novo metastatic prostate cancer is more common in veterans when compared with the general population, and therefore veterans may benefit by liquid biopsy. Differences in the frequency of genetic mutations (DDR, TP53, AR) in this cohort provides valuable information for disease progression, lack of response, mechanism of resistance to the implemented therapy and clinical decision making. Precision oncology can be further tailored for this cohort by focusing on DNA repair genes and Tp53 mutations for future targeted therapy.

The advent of liquid biopsies targeting genetic mutations in solid tumors is a major milestone in the field of precision oncology.1 Conventional methods of obtaining tissue for molecular studies are limited by sample size and often do not represent the entire bulk of the tumor.2 This newer minimally invasive, revolutionary technique analyzes circulating cell-free DNA carrying tumor-specific alterations (circulating tumor DNA [ctDNA]) in peripheral blood and detects signature genomic alterations.1 Tp53 mutations have been reported in 25 to 40% of prostatic cancers and > 50% of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC), being more common in late-stage and hormone refractory prostate cancers.3,4 Tp53 mutation has been found to be associated with poor prognosis and increased germline mutations.5

The veteran patient population has distinct demographic characteristics that make veterans more vulnerable to genetic mutations and malignancies, including risk of exposure to Agent Orange, smoking, substance abuse, and asbestos. This area is understudied and extremely sparse in the literature for frequency of genetic mutations, risk factors in solid malignancies occurring in the veteran patient population, and the clinical impact of these risk factors. We herein present a quality assurance study for the utility of liquid biopsies regarding the frequency of DNA damage repair (DDR) gene, Tp53, and androgen receptor (AR) mutations. The clinical impact in advanced lung and prostate cancers in the veteran patient population and frequency are the quality assurance observations that are the study endpoints.

Methods

We reviewed for quality assurance documentation from the Foundation Medicine (www.foundationmedicine.com) cancer biomarker tests on liquid biopsies performed at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Veteran Affairs Medical Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania from May 2019 to April 15, 2020. All biopsies were performed on cancers with biochemical, imaging or tissue evidence of advanced tumor progression. The testing was performed on advanced solid malignancies, including NSCLC, prostate adenocarcinoma, and metastatic colon cancer. Statistical data for adequacy; cases with notable mutations; frequency; and type of mutations of AR, DDR, and Tp53 were noted. General and specific risk factors associated with the veteran patient population were studied and matched with the type of mutations (Table 1).

Results

Thirty-one liquid biopsies were performed over this period—23 for prostate cancer, 7 for patients with lung cancer patients, and 1 for a patient with colon cancer. Of 31 cases, sensitivity/adequacy of liquid biopsy for genetic mutation was detected in 29 (93.5%) cases (Figure 1). Two inadequate biopsies (both from patients with prostate cancer) were excluded from the study, leaving 29 liquid biopsies with adequate ctDNA for analysis that were considered for further statistical purpose—21 prostate, 7 lung, and 1 colon cancer.

Multiple (common and different) genetic mutations were identified; however, our study subcategorized the mutations into the those that were related to prostate cancer, lung cancer, and some common mutations that occur in both cancers. Only the significant ones will be discussed in this review and equivocal result for AR is excluded from this study. Of the 21 prostate cancers, 4 (19.0%) had directed the targeted therapy to driver mutation (AR being most common in prostate cancer), while KRAS mutation, which was more common in lung cancer, was detected in 2/7 (28.6%) lung cancers. Mutations common to both cancer types were DDR gene mutations, which is a broad name for numerous genes including CDK12, ATM, and CHEK2.

Of all cases irrespective of the cancer type, 23/29 (79.3%) showed notable mutations. DDR gene mutations were found in 6 of 21 (28.5%) patients with prostate cancer and 8 of 23 (34.7%) patients with advanced prostate and lung cancers, indicating poor outcome and possible resistance to the current therapy. Of 23 patients showing mutations irrespective of the cancer type, 15 (65.2%) harbored Tp53 mutations, which is much more frequent in veteran patient population when compared with the literature. Fifteen of the 31 (48.4%) total patients were Vietnam War-era veterans who were potentially exposed to Agent Orange and 20 (64.5%) patients who were not Vietnam War-era veterans had a history that included smoking (Figure 2).

Discussion

The veteran patient population is a unique cohort due to its distinct demographic characteristics with a high volume of cancer cases diagnosed each year. According to data from VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR), the most frequently diagnosed cancers are prostate (29%) and lung (18%).6

Liquid biopsy is a novel, promising technology that uses ctDNA and circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood for detecting genetic alterations through next generation sequencing.7-9 The advent of this minimally invasive, revolutionary technology has been a breakthrough in the field of precision oncology for prognosis, to monitor treatment response or resistance to therapy and further personalize cancer therapy.9,10

Comprehensive genomic profiling by liquid biopsy has many advantages over the molecular studies performed on tissue biopsy. Due to the tumor heterogeneity, tissue samples may not represent the full profile of the tumor genomics of cancer, while liquid biopsy has full presentation of the disease.11,12 Many times, tissue biopsy may be limited by a sample size that precludes full genetic profiling in addition to higher total cost, potential technical issues during processing, and possible side effects of the biopsy procedure.7,13 Additionally, as the tumor progresses, new driver mutations other than the ones previously detected on the primary tissue may emerge, which can confer resistance to the existing therapy.7,13

Advanced prostatic and lung carcinomas with biochemical, distant organ, or bony progression harbor unique signature genetic mutations indicating poor prognosis, lack of response or resistance to the existing therapy, and high risk of relapse.14,15 Some of the unique characteristics of the veteran patient population include a more aged patient population multiple comorbidities, higher frequency of > 1 type of cancer, advanced cancer stage at presentation, and specific risks factors such as exposure to Agent Orange in veterans who served during the Vietnam War era.16,17 We studied the utility of liquid biopsy in cancer care, including type and incidence of genomic alterations associated with advanced prostate and lung cancers, in this unique patient population.

The amount of cell-free DNA (cfDNA), also known as ctDNA varies widely in cancer patients. Some of the factors associated with low concentration of cfDNA are disease stage, intervening therapy, proliferation rates, and tumor vascularization.18,19 In the peripheral blood, of the total cfDNA, fractions of cfDNA varies from 0.01 to 90%.18,19 All samples containing ≥ 20 ng cfDNA (20 - 100 ng) were subjected to the hybrid capture-based NGS FoundationACT assay.20 In our study, 2 specimens did not meet the minimum criteria of adequacy (20 ng cfDNA); however, the overall adequacy rate for the detection of mutation, irrespective of the cancer type was 29 of 31 (93.5%) with only 2 inadequate samples. This rate is higher than the rate reported in the literature, which is about 70%.20

Significant differences were encountered in the incidence of DNA damage repair genes including Tp53 mutations when compared with those in the general patient population (Table 2). According to recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, all prostate cancers should be screened for DDR gene mutations as these genes are common in aggressive prostate cancers and strongly associated with poor outcomes and shortened survival. Due to relatively high frequency of DDR gene mutations in advanced prostatic cancers, liquid biopsy in patients with these advanced stage prostate cancers may be a useful tool in clinical decision making and exploring targeted therapy.20

Mutations in BRCA2, ATM, CDK12, and CHEK2 (DDR gene family) are common. Incidence of ATM and CDK12 mutations in the literature is 3 to 6% of cases.21 Of 21 liquid biopsies of advanced prostate cancer patients, we found combined DDR gene mutation of ATM, CHEK2, and CDK12 genes in 6 (28.5%) cases, which is substantially higher than the 3 to 6% rate reported in the literature.21-24 Of the 23 patients who had notable mutations in our liquid biopsies, including both advanced prostate and lung cancer cases, 8 (34.7%) also showed mutation of the genes of DDR family. Our study did not show BRCA2 mutation, which is otherwise common in the literature.

We also evaluated the frequency of the most commonly occurring genetic mutations, Tp53 in advanced solid malignancies, especially advanced prostate and NSCLC. Previous studies have reported Tp53 mutation in association with risk factors (carcinogens) of cancer and have been a surrogate marker of poor survival or lack of response of therapy.25 Knowledge of Tp53 mutation is crucial for closer disease monitoring, preparing the patient for rapid progression, and encouraging the physician to prepare future lines of therapy.25-27 Although Tp53 mutation varies with histologic type and tissue of origin, Beltran and colleagues reported it in 30 to 40% of tumors, while Robles and colleagues reported about 40 to 42% incidence.25,27

Our study showed notable mutations in 23 of 29 adequate cases. Further, our study showed a high frequency of mutated Tp53 in 65.2% of combined advanced prostate and NSCLC cases. We then correlated cases of Vietnam War-era veterans with risk potential of Agent Orange exposure and Tp53 mutation. We found 7 of 15 Vietnam War-era veterans were positive for Tp53 mutations irrespective of the cancer type. The high incidence of Tp53 mutations in advanced prostate and lung carcinomas in the veteran patient population makes this tumor marker an aspiration not only as a surrogate of aggressive disease and tumor progression, but also as a key marker for targeted therapy in advanced prostate and lung cancers with loss of Tp53 function (Figure 3).

Mutations and amplifications in the AR gene are fundamental to progression of prostate cancer associated with advanced, hormone-refractory prostate cancer with the potential for targeted therapy with AR inhibitors. In our study, AR amplification was detected in 4 of 21 (19%) advanced prostate cancer cases, which is significantly lower than the 30 to 50% previously reported in the literature.28-32 Neither AR amplification or mutation was noted in advanced NSCLC in our study as previously reported in literature by Brennan and colleagues and Wang and colleagues.33-35 This is significant as it provides a pathway for future studies to focus on additional driver mutations for targeted therapies in advanced prostate carcinoma. To date, AR gene mutation does not play a role for personalized therapy in advanced NSCLC. Perhaps, a large cohort study with longitudinal analysis is needed for absolutely ruling out the possibility of personalized medicine in advanced lung cancer using this biomarker.

Conclusions

Liquid biopsy successfully provides precision-based oncology and information for decision making in this unique population of veterans. Difference in frequency of the genetic mutations in this cohort can provide future insight into disease progression, lack of response, and mechanism of resistance to the implemented therapy. Future studies focused on this veteran patient population are needed for developing targeted therapies and patient tailored oncologic therapy. ctDNA has a high potential for monitoring clinically relevant cancer-related genetic and epigenetic modifications for discovering more detailed information on the tumor characterization. Although larger cohort trial with longitudinal analyses are needed, high prevalence of DDR gene and Tp53 mutation in our study instills promising hope for therapeutic interventions in this unique cohort.

The minimally invasive liquid biopsy shows a great promise as both diagnostic and prognostic tool in the personalized clinical management of advanced prostate, and NSCLC in the veteran patient population with unique demographic characteristics. De novo metastatic prostate cancer is more common in veterans when compared with the general population, and therefore veterans may benefit by liquid biopsy. Differences in the frequency of genetic mutations (DDR, TP53, AR) in this cohort provides valuable information for disease progression, lack of response, mechanism of resistance to the implemented therapy and clinical decision making. Precision oncology can be further tailored for this cohort by focusing on DNA repair genes and Tp53 mutations for future targeted therapy.

1

9

16. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review the Health Effects in Vietnam Veterans of Exposure to Herbicides (Fourth Biennial Update). Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2002. National Academies Press (US); 2003.

17. Eibner C, Krull H, Brown KM, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique health care needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Rand Health Q. 2016;5(4):13. Published 2016 May 9.

18. Saarenheimo J, Eigeliene N, Andersen H, Tiirola M, Jekunen A. The value of liquid biopsies for guiding therapy decisions in non-small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:129. Published 2019 Mar 5.doi:10.3389/fonc.2019.00129

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31. Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Luber B, et al. Clinical significance of androgen receptor splice variant-7 mRNA detection in circulating tumor cells of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with first- and second-line abiraterone and enzalutamide. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(19):2149-2156. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1961

32

33. Jung A, Kirchner T. Liquid biopsy in tumor genetic diagnosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(10):169-174. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2018.0169

34. Brennan S, Wang AR, Beyer H, et al. Androgen receptor as a potential target in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77(Suppl13): abstract nr 4121. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.AM2017-4121

35. Wang AR, Beyer H, Brennan S, et al. Androgen receptor drives differential gene expression in KRAS-mediated non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78(Suppl 13): abstract nr 3946. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.AM2018-3946

1

9

16. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review the Health Effects in Vietnam Veterans of Exposure to Herbicides (Fourth Biennial Update). Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2002. National Academies Press (US); 2003.

17. Eibner C, Krull H, Brown KM, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique health care needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Rand Health Q. 2016;5(4):13. Published 2016 May 9.

18. Saarenheimo J, Eigeliene N, Andersen H, Tiirola M, Jekunen A. The value of liquid biopsies for guiding therapy decisions in non-small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:129. Published 2019 Mar 5.doi:10.3389/fonc.2019.00129

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31. Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Luber B, et al. Clinical significance of androgen receptor splice variant-7 mRNA detection in circulating tumor cells of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with first- and second-line abiraterone and enzalutamide. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(19):2149-2156. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1961

32

33. Jung A, Kirchner T. Liquid biopsy in tumor genetic diagnosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(10):169-174. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2018.0169

34. Brennan S, Wang AR, Beyer H, et al. Androgen receptor as a potential target in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77(Suppl13): abstract nr 4121. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.AM2017-4121

35. Wang AR, Beyer H, Brennan S, et al. Androgen receptor drives differential gene expression in KRAS-mediated non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78(Suppl 13): abstract nr 3946. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.AM2018-3946