User login

A Case of Shortness of Breath, Abdominal Pain, and Hematuria

A48-year-old male presents with three weeks of worsening shortness of breath and pleuritic chest discomfort. A week before the onset of these symptoms, he noticed increasing fatigue, weight loss, abdominal discomfort, and persistent hematuria He was otherwise healthy and was taking no medications.

Physical examination reveals a tachypneic yet hemodynamically stable patient, with left upper quadrant fullness. CT chest and abdomen, reveal the following (see right).

You suspect that this finding is secondary to an extrapulmonary process. What unifying diagnosis most likely accounts for these findings? What is your diagnosis?

- Antiphospholipid syndrome

- Antithrombin III deficiency

- Renal cell carcinoma

- Protein C deficiency

- Prostate carcinoma

Discussion

The answer is C: Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with caval extension causing PE; this suggests that the PE was due to tumor thrombus. The photo on p. 8 shows areas of increased attenuation in the prominent right and left pulmonary arteries, consistent with a saddle pulmonary embolism. An MRI of the abdomen (see photo above) reveals a large left renal mass extending to Gerota’s fascia and into the left renal vein, protruding slightly into the inferior vena cava (IVC).

The MRI demonstrates an occlusive thrombus in the left renal vein with propagation into the inferior vena cava. The patient underwent a left radical nephrectomy, an inferior vena cava thrombectomy, and a saddle embolectomy. Histological examination of the mass and thrombus confirmed the diagnosis. He had an uneventful recovery and was discharged from the hospital.

RCC accounts for approximately 80% of all primary renal neoplasms, and commonly is termed the “internist’s tumor.” Hematuria is the most common symptom. It is accompanied by flank pain and a palpable abdominal mass in less than 15% of cases.1 Diagnosis of RCC is often made late due to delayed clinical presentation and 20% of patients have metastatic disease at initial diagnosis.2 PE due to tumor thrombus as an initial manifestation of RCC is rare, but is a well-recognized entity leading to dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, hypoxemia, and—in severe cases—acute cor pulmonale with hemodynamic failure.3-5

Staging CT is required in patients with suspected RCC, and MRI is needed, with transesophageal echocardiography used adjunctively, to evaluate cephalic thrombus extension when indicated.6 IVC tumor thrombus occurs in 4%-10% of all cases, most often originating in the renal vein and extending cranially, subsequently propagating to the lungs.7 Survival in local non-metastatic disease with IVC thrombus is no different whether renal vein extension occurs or not, and ranges from 40%-69%, following surgical resection and thrombectomy.8 In those with distant metastases who require venal caval thrombectomy, five-year survivals range from 0%-12.5%.2

The first case of successful removal of a PE secondary to RCC was documented in 1977.1 The goal of surgery is tumor resection and prevention of recurrent embolic events. It is the only effective means of improving survival in the presence of intravascular tumor. Preoperative anticoagulation may be warranted in patients who present with PE, but should be discontinued following definitive surgical treatment secondary to increased risks of hemorrhage.8 TH

References

- Daughtry JD, Stewart BH, Golding LAR, Groves LK. Pulmonary embolus presenting as the initial manifestation of renal cell carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1977;24:178-181.

- Goetzl MA, Goluboff ET, Murphy AM, et al. A contemporary evaluation of cytoreductive nephrectomy with tumor thrombus: morbidity and long term survival. Urol Oncol. 2004; 22:182-187.

- Kubota H, Furuse A, Kotsuka Y, et al. Successful management of massive pulmonary tumor embolism from renal cell carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:708-710.

- Gayer G, Mini S, Olchovsky D, et al. Pulmonary embolism—the initial manifestation of renal cell carcinoma in a young woman. Emerg Radiol. 2003;10:43-45.

- Eggener SE, Dalton DP. Bilateral pulmonary artery tumour emboli from renal carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:173.

- Tsuji Y, Goto A, Hara I, et al. Renal cell carcinoma with extension of tumor thrombus into vena cava: Surgical strategy and prognosis. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:789-796.

- Zisman A, Pantuck AJ, Chao DH, et al. Renal cell carcinoma with tumor thrombus: is cytoreductive nephrectomy for advanced disease associated with an increased complication rate? J Urol. 2002;168:962-967.

- Nesbitt JC, Soltero ER, Dinney CPN, et al. Surgical management of renal cell carcinoma with inferior vena cava tumor thrombus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1592-1600.

A48-year-old male presents with three weeks of worsening shortness of breath and pleuritic chest discomfort. A week before the onset of these symptoms, he noticed increasing fatigue, weight loss, abdominal discomfort, and persistent hematuria He was otherwise healthy and was taking no medications.

Physical examination reveals a tachypneic yet hemodynamically stable patient, with left upper quadrant fullness. CT chest and abdomen, reveal the following (see right).

You suspect that this finding is secondary to an extrapulmonary process. What unifying diagnosis most likely accounts for these findings? What is your diagnosis?

- Antiphospholipid syndrome

- Antithrombin III deficiency

- Renal cell carcinoma

- Protein C deficiency

- Prostate carcinoma

Discussion

The answer is C: Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with caval extension causing PE; this suggests that the PE was due to tumor thrombus. The photo on p. 8 shows areas of increased attenuation in the prominent right and left pulmonary arteries, consistent with a saddle pulmonary embolism. An MRI of the abdomen (see photo above) reveals a large left renal mass extending to Gerota’s fascia and into the left renal vein, protruding slightly into the inferior vena cava (IVC).

The MRI demonstrates an occlusive thrombus in the left renal vein with propagation into the inferior vena cava. The patient underwent a left radical nephrectomy, an inferior vena cava thrombectomy, and a saddle embolectomy. Histological examination of the mass and thrombus confirmed the diagnosis. He had an uneventful recovery and was discharged from the hospital.

RCC accounts for approximately 80% of all primary renal neoplasms, and commonly is termed the “internist’s tumor.” Hematuria is the most common symptom. It is accompanied by flank pain and a palpable abdominal mass in less than 15% of cases.1 Diagnosis of RCC is often made late due to delayed clinical presentation and 20% of patients have metastatic disease at initial diagnosis.2 PE due to tumor thrombus as an initial manifestation of RCC is rare, but is a well-recognized entity leading to dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, hypoxemia, and—in severe cases—acute cor pulmonale with hemodynamic failure.3-5

Staging CT is required in patients with suspected RCC, and MRI is needed, with transesophageal echocardiography used adjunctively, to evaluate cephalic thrombus extension when indicated.6 IVC tumor thrombus occurs in 4%-10% of all cases, most often originating in the renal vein and extending cranially, subsequently propagating to the lungs.7 Survival in local non-metastatic disease with IVC thrombus is no different whether renal vein extension occurs or not, and ranges from 40%-69%, following surgical resection and thrombectomy.8 In those with distant metastases who require venal caval thrombectomy, five-year survivals range from 0%-12.5%.2

The first case of successful removal of a PE secondary to RCC was documented in 1977.1 The goal of surgery is tumor resection and prevention of recurrent embolic events. It is the only effective means of improving survival in the presence of intravascular tumor. Preoperative anticoagulation may be warranted in patients who present with PE, but should be discontinued following definitive surgical treatment secondary to increased risks of hemorrhage.8 TH

References

- Daughtry JD, Stewart BH, Golding LAR, Groves LK. Pulmonary embolus presenting as the initial manifestation of renal cell carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1977;24:178-181.

- Goetzl MA, Goluboff ET, Murphy AM, et al. A contemporary evaluation of cytoreductive nephrectomy with tumor thrombus: morbidity and long term survival. Urol Oncol. 2004; 22:182-187.

- Kubota H, Furuse A, Kotsuka Y, et al. Successful management of massive pulmonary tumor embolism from renal cell carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:708-710.

- Gayer G, Mini S, Olchovsky D, et al. Pulmonary embolism—the initial manifestation of renal cell carcinoma in a young woman. Emerg Radiol. 2003;10:43-45.

- Eggener SE, Dalton DP. Bilateral pulmonary artery tumour emboli from renal carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:173.

- Tsuji Y, Goto A, Hara I, et al. Renal cell carcinoma with extension of tumor thrombus into vena cava: Surgical strategy and prognosis. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:789-796.

- Zisman A, Pantuck AJ, Chao DH, et al. Renal cell carcinoma with tumor thrombus: is cytoreductive nephrectomy for advanced disease associated with an increased complication rate? J Urol. 2002;168:962-967.

- Nesbitt JC, Soltero ER, Dinney CPN, et al. Surgical management of renal cell carcinoma with inferior vena cava tumor thrombus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1592-1600.

A48-year-old male presents with three weeks of worsening shortness of breath and pleuritic chest discomfort. A week before the onset of these symptoms, he noticed increasing fatigue, weight loss, abdominal discomfort, and persistent hematuria He was otherwise healthy and was taking no medications.

Physical examination reveals a tachypneic yet hemodynamically stable patient, with left upper quadrant fullness. CT chest and abdomen, reveal the following (see right).

You suspect that this finding is secondary to an extrapulmonary process. What unifying diagnosis most likely accounts for these findings? What is your diagnosis?

- Antiphospholipid syndrome

- Antithrombin III deficiency

- Renal cell carcinoma

- Protein C deficiency

- Prostate carcinoma

Discussion

The answer is C: Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with caval extension causing PE; this suggests that the PE was due to tumor thrombus. The photo on p. 8 shows areas of increased attenuation in the prominent right and left pulmonary arteries, consistent with a saddle pulmonary embolism. An MRI of the abdomen (see photo above) reveals a large left renal mass extending to Gerota’s fascia and into the left renal vein, protruding slightly into the inferior vena cava (IVC).

The MRI demonstrates an occlusive thrombus in the left renal vein with propagation into the inferior vena cava. The patient underwent a left radical nephrectomy, an inferior vena cava thrombectomy, and a saddle embolectomy. Histological examination of the mass and thrombus confirmed the diagnosis. He had an uneventful recovery and was discharged from the hospital.

RCC accounts for approximately 80% of all primary renal neoplasms, and commonly is termed the “internist’s tumor.” Hematuria is the most common symptom. It is accompanied by flank pain and a palpable abdominal mass in less than 15% of cases.1 Diagnosis of RCC is often made late due to delayed clinical presentation and 20% of patients have metastatic disease at initial diagnosis.2 PE due to tumor thrombus as an initial manifestation of RCC is rare, but is a well-recognized entity leading to dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, hypoxemia, and—in severe cases—acute cor pulmonale with hemodynamic failure.3-5

Staging CT is required in patients with suspected RCC, and MRI is needed, with transesophageal echocardiography used adjunctively, to evaluate cephalic thrombus extension when indicated.6 IVC tumor thrombus occurs in 4%-10% of all cases, most often originating in the renal vein and extending cranially, subsequently propagating to the lungs.7 Survival in local non-metastatic disease with IVC thrombus is no different whether renal vein extension occurs or not, and ranges from 40%-69%, following surgical resection and thrombectomy.8 In those with distant metastases who require venal caval thrombectomy, five-year survivals range from 0%-12.5%.2

The first case of successful removal of a PE secondary to RCC was documented in 1977.1 The goal of surgery is tumor resection and prevention of recurrent embolic events. It is the only effective means of improving survival in the presence of intravascular tumor. Preoperative anticoagulation may be warranted in patients who present with PE, but should be discontinued following definitive surgical treatment secondary to increased risks of hemorrhage.8 TH

References

- Daughtry JD, Stewart BH, Golding LAR, Groves LK. Pulmonary embolus presenting as the initial manifestation of renal cell carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1977;24:178-181.

- Goetzl MA, Goluboff ET, Murphy AM, et al. A contemporary evaluation of cytoreductive nephrectomy with tumor thrombus: morbidity and long term survival. Urol Oncol. 2004; 22:182-187.

- Kubota H, Furuse A, Kotsuka Y, et al. Successful management of massive pulmonary tumor embolism from renal cell carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:708-710.

- Gayer G, Mini S, Olchovsky D, et al. Pulmonary embolism—the initial manifestation of renal cell carcinoma in a young woman. Emerg Radiol. 2003;10:43-45.

- Eggener SE, Dalton DP. Bilateral pulmonary artery tumour emboli from renal carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:173.

- Tsuji Y, Goto A, Hara I, et al. Renal cell carcinoma with extension of tumor thrombus into vena cava: Surgical strategy and prognosis. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:789-796.

- Zisman A, Pantuck AJ, Chao DH, et al. Renal cell carcinoma with tumor thrombus: is cytoreductive nephrectomy for advanced disease associated with an increased complication rate? J Urol. 2002;168:962-967.

- Nesbitt JC, Soltero ER, Dinney CPN, et al. Surgical management of renal cell carcinoma with inferior vena cava tumor thrombus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1592-1600.

Critical Coalition

March is an important month for SHM. It is DVT Awareness Month, and once again SHM is leading a coalition of almost 40 organizations to raise the understanding of this disease. DVT causes complications that kill more people every year than AIDS and breast cancer combined. This coalition includes the American College of Physicians, the American Public Health Association, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Society of Health System Pharmacists, the American Association of Critical Care Nurses, and many more.

The goals of the coalition are to use our knowledge and influence to inform not only the public at large, but health professionals as well. And if our success in 2005 is any measure, the DVT Awareness campaign has really had an impact.

Last year more than 400 million people saw on TV or read our message in magazines and newspapers. Utilizing the compelling story of our national spokesperson, Melanie Bloom, a mother of three girls who lost her young, athletic NBC war-correspondent husband, David, to a fatal pulmonary embolism (PE), our message was seen on “Larry King Live” on CNN, on the “Jane Pauley Show,” on “Access Hollywood,” and in Ladies Home Journal.

Often Melanie was accompanied by hospitalists such as Frank Michota, MD, the head of the Hospital Medicine Division at Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Michota answered the clinical questions in the interviews. Who can forget when Larry King turned to Dr. Michota and asked, “Are you a cardiologist?”

“No, Larry, I am a hospitalist,” said Dr. Michota.

And when Larry King asked “What is a hospitalist?” Dr. Michota spread the gospel according to hospital medicine to a nationwide audience.

Later in the year a billboard on Rockefeller Center in New York City proclaimed the DVT Awareness message along with the SHM logo. If you can make it there, you can make it anywhere.

But this campaign isn’t just about TV appearances and magazine articles. This is about using awareness to save lives. And save lives we did. More than a thousand letters and e-mails were sent to the coalition in 2005 from patients and family members with personal stories of how exposure to our campaign led them to go to their doctors or show up in an ED. They were treated early for DVT—before they developed a potentially fatal PE. They credit the DVT Awareness Campaign with saving their lives.

In 2006 SHM is back at the head of the coalition. In January at the National Press Club, I was fortunate enough to help roll out the details of our 2006 campaign. Joining me on the dais were Dr. Michota; Geno Merli, MD, from Jefferson Medical College and a frequent speaker at SHM meetings; and Sam Goldhaber, MD, from Harvard’s Brigham and Women’s in Boston.

This year we have set a goal of further engaging the public by telling our patients’ stories, by forming patient affinity groups, by providing the tools for health professionals to provide the best care for DVT and PE, and by continuing to use the media to spread our message.

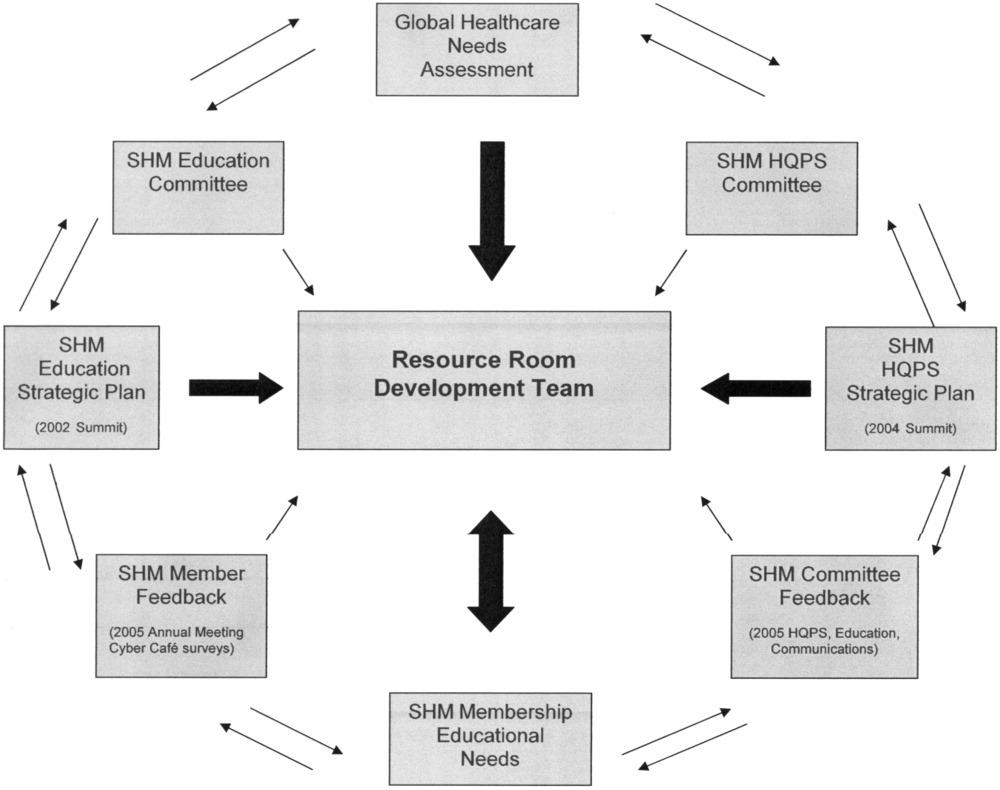

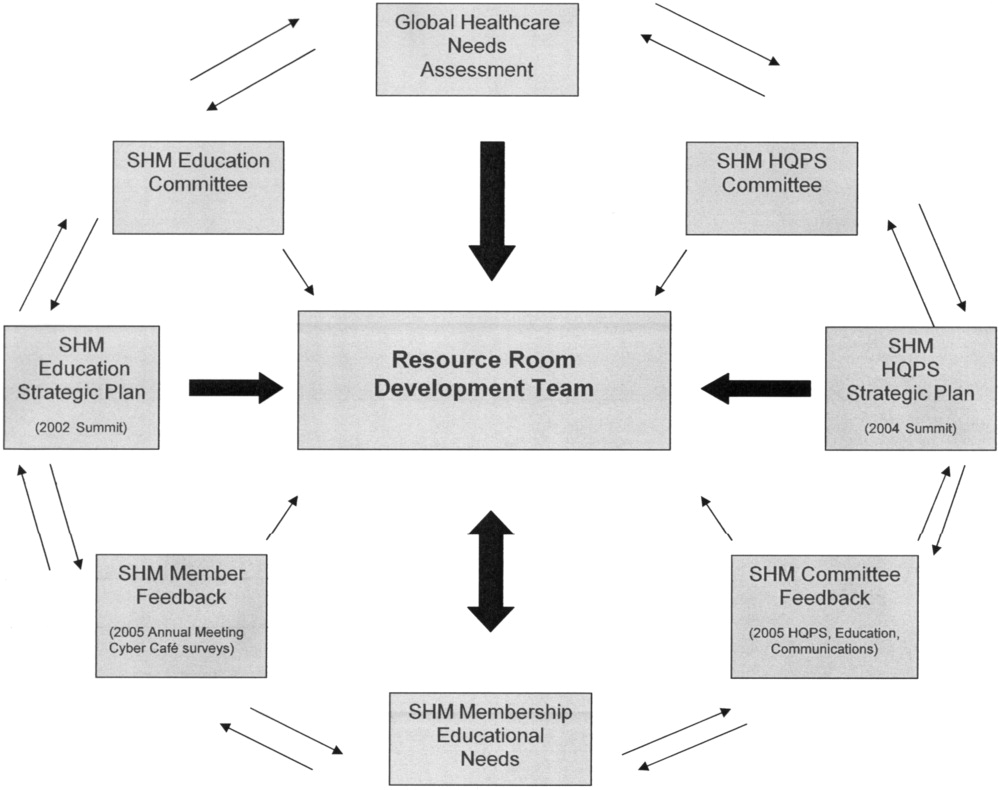

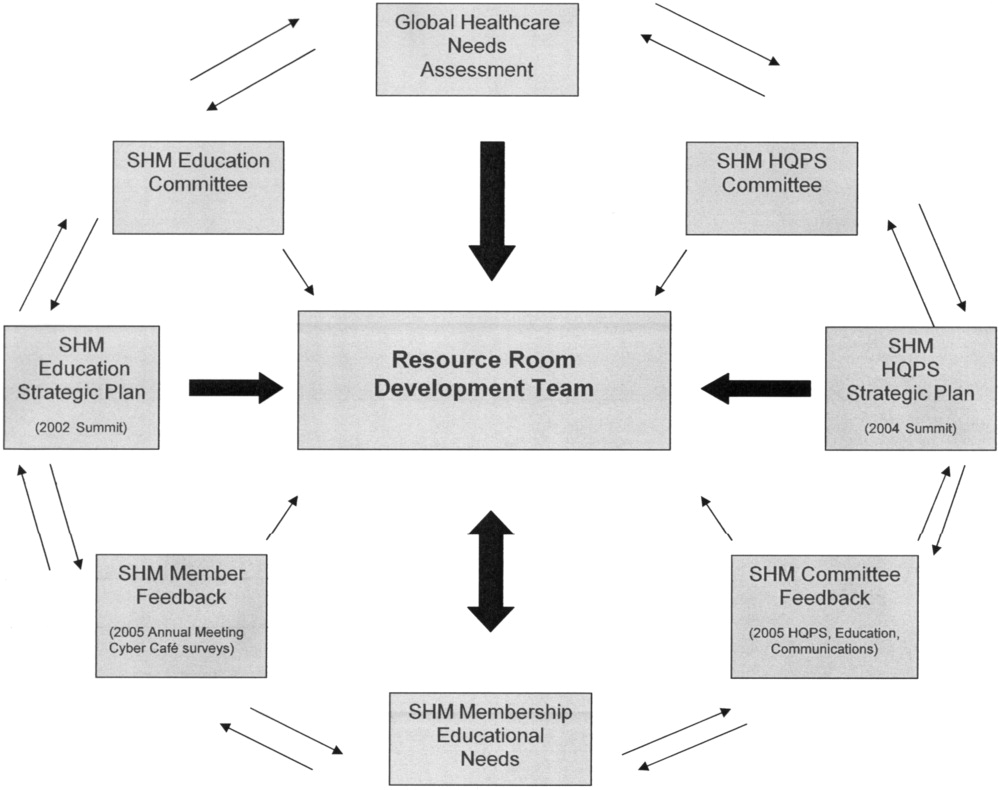

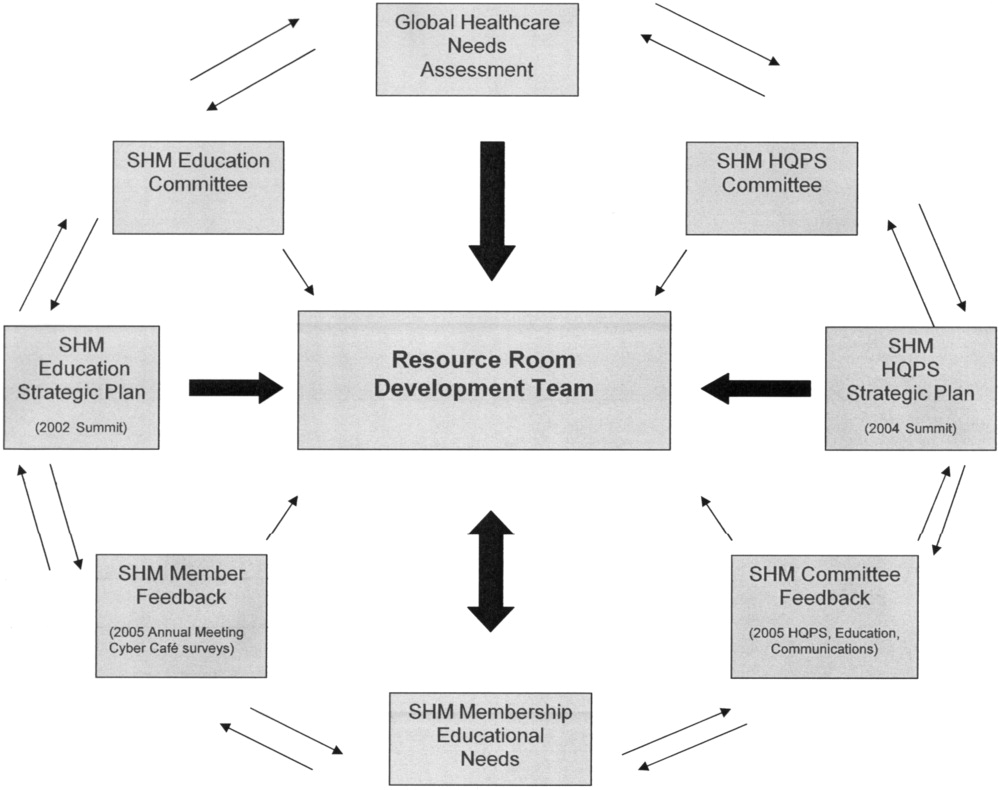

SHM has a robust set of educational and quality improvement tools in the DVT Resource Room on the SHM Web site at www.hospitalmedicine.org under the “Quality/Patient Safety” tab. There hospitalists can find an SHM DVT workbook to help measure their performance and improve their outcomes. At the SHM 2006 Annual Meeting on May 3, from 8 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., SHM will host a precourse on quality improvement, and one of the key conditions is DVT. SHM hopes to raise funds for future demonstration projects to improve patient outcomes in DVT and even to set up skilled mentors who can help hospitalists trying to affect change at their hospitals for the first time.

SHM is a young, enthusiastic organization that lacks the cynicism of entrenchment. We actually do believe with some help and support we can make quality matter, even without pay for performance and before regulated performance standards.

We see the DVT Awareness Coalition as a template for SHM’s call to action. It involves participation across the continuum involving other physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and patients. It is proactive and targeted with not only improving public knowledge, but recognizing that maybe not every doctor and nurse knows all the latest information, either. It is focused on making a tangible difference, not just writing a white paper or a guideline and declaring victory. It is about saving lives in 2005 and again in 2006. It is about multiplying the efforts of SHM by the multiple of the number of hospitals that now have hospitalists.

There is much promise to hospital medicine. Some see this as a future play with only a foundation being built today. There are surely many great things ahead for hospital medicine as we grow to more than 30,000 hospitalists at virtually every hospital in America. There are many skills left for us to learn. But hospitalists and SHM are making a difference today. We are not doing it alone, but through teamwork and coalition-building. We are proud to be a partner in the DVT Awareness Coalition and we are glad to provide leadership when asked. The payoff is in the lives we have saved and the lives we have changed for the better. TH

Dr. Wellikson has been CEO of SHM since 2000.

March is an important month for SHM. It is DVT Awareness Month, and once again SHM is leading a coalition of almost 40 organizations to raise the understanding of this disease. DVT causes complications that kill more people every year than AIDS and breast cancer combined. This coalition includes the American College of Physicians, the American Public Health Association, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Society of Health System Pharmacists, the American Association of Critical Care Nurses, and many more.

The goals of the coalition are to use our knowledge and influence to inform not only the public at large, but health professionals as well. And if our success in 2005 is any measure, the DVT Awareness campaign has really had an impact.

Last year more than 400 million people saw on TV or read our message in magazines and newspapers. Utilizing the compelling story of our national spokesperson, Melanie Bloom, a mother of three girls who lost her young, athletic NBC war-correspondent husband, David, to a fatal pulmonary embolism (PE), our message was seen on “Larry King Live” on CNN, on the “Jane Pauley Show,” on “Access Hollywood,” and in Ladies Home Journal.

Often Melanie was accompanied by hospitalists such as Frank Michota, MD, the head of the Hospital Medicine Division at Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Michota answered the clinical questions in the interviews. Who can forget when Larry King turned to Dr. Michota and asked, “Are you a cardiologist?”

“No, Larry, I am a hospitalist,” said Dr. Michota.

And when Larry King asked “What is a hospitalist?” Dr. Michota spread the gospel according to hospital medicine to a nationwide audience.

Later in the year a billboard on Rockefeller Center in New York City proclaimed the DVT Awareness message along with the SHM logo. If you can make it there, you can make it anywhere.

But this campaign isn’t just about TV appearances and magazine articles. This is about using awareness to save lives. And save lives we did. More than a thousand letters and e-mails were sent to the coalition in 2005 from patients and family members with personal stories of how exposure to our campaign led them to go to their doctors or show up in an ED. They were treated early for DVT—before they developed a potentially fatal PE. They credit the DVT Awareness Campaign with saving their lives.

In 2006 SHM is back at the head of the coalition. In January at the National Press Club, I was fortunate enough to help roll out the details of our 2006 campaign. Joining me on the dais were Dr. Michota; Geno Merli, MD, from Jefferson Medical College and a frequent speaker at SHM meetings; and Sam Goldhaber, MD, from Harvard’s Brigham and Women’s in Boston.

This year we have set a goal of further engaging the public by telling our patients’ stories, by forming patient affinity groups, by providing the tools for health professionals to provide the best care for DVT and PE, and by continuing to use the media to spread our message.

SHM has a robust set of educational and quality improvement tools in the DVT Resource Room on the SHM Web site at www.hospitalmedicine.org under the “Quality/Patient Safety” tab. There hospitalists can find an SHM DVT workbook to help measure their performance and improve their outcomes. At the SHM 2006 Annual Meeting on May 3, from 8 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., SHM will host a precourse on quality improvement, and one of the key conditions is DVT. SHM hopes to raise funds for future demonstration projects to improve patient outcomes in DVT and even to set up skilled mentors who can help hospitalists trying to affect change at their hospitals for the first time.

SHM is a young, enthusiastic organization that lacks the cynicism of entrenchment. We actually do believe with some help and support we can make quality matter, even without pay for performance and before regulated performance standards.

We see the DVT Awareness Coalition as a template for SHM’s call to action. It involves participation across the continuum involving other physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and patients. It is proactive and targeted with not only improving public knowledge, but recognizing that maybe not every doctor and nurse knows all the latest information, either. It is focused on making a tangible difference, not just writing a white paper or a guideline and declaring victory. It is about saving lives in 2005 and again in 2006. It is about multiplying the efforts of SHM by the multiple of the number of hospitals that now have hospitalists.

There is much promise to hospital medicine. Some see this as a future play with only a foundation being built today. There are surely many great things ahead for hospital medicine as we grow to more than 30,000 hospitalists at virtually every hospital in America. There are many skills left for us to learn. But hospitalists and SHM are making a difference today. We are not doing it alone, but through teamwork and coalition-building. We are proud to be a partner in the DVT Awareness Coalition and we are glad to provide leadership when asked. The payoff is in the lives we have saved and the lives we have changed for the better. TH

Dr. Wellikson has been CEO of SHM since 2000.

March is an important month for SHM. It is DVT Awareness Month, and once again SHM is leading a coalition of almost 40 organizations to raise the understanding of this disease. DVT causes complications that kill more people every year than AIDS and breast cancer combined. This coalition includes the American College of Physicians, the American Public Health Association, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Society of Health System Pharmacists, the American Association of Critical Care Nurses, and many more.

The goals of the coalition are to use our knowledge and influence to inform not only the public at large, but health professionals as well. And if our success in 2005 is any measure, the DVT Awareness campaign has really had an impact.

Last year more than 400 million people saw on TV or read our message in magazines and newspapers. Utilizing the compelling story of our national spokesperson, Melanie Bloom, a mother of three girls who lost her young, athletic NBC war-correspondent husband, David, to a fatal pulmonary embolism (PE), our message was seen on “Larry King Live” on CNN, on the “Jane Pauley Show,” on “Access Hollywood,” and in Ladies Home Journal.

Often Melanie was accompanied by hospitalists such as Frank Michota, MD, the head of the Hospital Medicine Division at Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Michota answered the clinical questions in the interviews. Who can forget when Larry King turned to Dr. Michota and asked, “Are you a cardiologist?”

“No, Larry, I am a hospitalist,” said Dr. Michota.

And when Larry King asked “What is a hospitalist?” Dr. Michota spread the gospel according to hospital medicine to a nationwide audience.

Later in the year a billboard on Rockefeller Center in New York City proclaimed the DVT Awareness message along with the SHM logo. If you can make it there, you can make it anywhere.

But this campaign isn’t just about TV appearances and magazine articles. This is about using awareness to save lives. And save lives we did. More than a thousand letters and e-mails were sent to the coalition in 2005 from patients and family members with personal stories of how exposure to our campaign led them to go to their doctors or show up in an ED. They were treated early for DVT—before they developed a potentially fatal PE. They credit the DVT Awareness Campaign with saving their lives.

In 2006 SHM is back at the head of the coalition. In January at the National Press Club, I was fortunate enough to help roll out the details of our 2006 campaign. Joining me on the dais were Dr. Michota; Geno Merli, MD, from Jefferson Medical College and a frequent speaker at SHM meetings; and Sam Goldhaber, MD, from Harvard’s Brigham and Women’s in Boston.

This year we have set a goal of further engaging the public by telling our patients’ stories, by forming patient affinity groups, by providing the tools for health professionals to provide the best care for DVT and PE, and by continuing to use the media to spread our message.

SHM has a robust set of educational and quality improvement tools in the DVT Resource Room on the SHM Web site at www.hospitalmedicine.org under the “Quality/Patient Safety” tab. There hospitalists can find an SHM DVT workbook to help measure their performance and improve their outcomes. At the SHM 2006 Annual Meeting on May 3, from 8 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., SHM will host a precourse on quality improvement, and one of the key conditions is DVT. SHM hopes to raise funds for future demonstration projects to improve patient outcomes in DVT and even to set up skilled mentors who can help hospitalists trying to affect change at their hospitals for the first time.

SHM is a young, enthusiastic organization that lacks the cynicism of entrenchment. We actually do believe with some help and support we can make quality matter, even without pay for performance and before regulated performance standards.

We see the DVT Awareness Coalition as a template for SHM’s call to action. It involves participation across the continuum involving other physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and patients. It is proactive and targeted with not only improving public knowledge, but recognizing that maybe not every doctor and nurse knows all the latest information, either. It is focused on making a tangible difference, not just writing a white paper or a guideline and declaring victory. It is about saving lives in 2005 and again in 2006. It is about multiplying the efforts of SHM by the multiple of the number of hospitals that now have hospitalists.

There is much promise to hospital medicine. Some see this as a future play with only a foundation being built today. There are surely many great things ahead for hospital medicine as we grow to more than 30,000 hospitalists at virtually every hospital in America. There are many skills left for us to learn. But hospitalists and SHM are making a difference today. We are not doing it alone, but through teamwork and coalition-building. We are proud to be a partner in the DVT Awareness Coalition and we are glad to provide leadership when asked. The payoff is in the lives we have saved and the lives we have changed for the better. TH

Dr. Wellikson has been CEO of SHM since 2000.

A Landmark Event

In February we experienced a landmark in the development of the field of hospital medicine with the publication of the premiere issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM). The debut of JHM demonstrates that hospital medicine is maturing as a field and—even more importantly—that it is developing as a new field with specific issues relevant to its practice.

It is difficult to overestimate the critical role that our journal will play in the growth of our field. The content for the inaugural issue of JHM reflects the depth and breadth of hospital medicine—community acquired pneumonia, palliative care, gastrointestinal bleeding, geriatrics, and a patient’s perspective on hospital care. The many authors who submitted their manuscripts took a leap of faith that our journal would be a respected and widely read vehicle for disseminating their hard work. This leap is even greater given that JHM is not yet listed in PubMed. Nonetheless these authors believe that JHM will thrive, be well read, and influence practice and patient care.

I agree because I know the talent of hospitalists and the potential of our field. The first issue of JHM also included a supplement devoted to the core competencies in hospital medicine. These core competencies represent another milestone in the growth of our field. With the core competencies we have outlined the specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes that define who we are and what we do.

Bringing a journal from concept to reality takes a Herculean effort by many people. I especially want to thank Mark Williams, MD, editor of JHM, for his leadership and grand vision for JHM that reflects our society and field so well. I also want to thank the associate editors and editorial board for giving their time, energy, and expertise to our journal.

I want to share my gratitude and appreciation for Larry Wellikson, MD, the CEO of SHM, who took an idea and mandate presented by the SHM Board of Directors and “operationalized” it in the most effective way. Finally, I want to thank Vickie Thaw, associate publisher at John Wiley & Sons, and her publishing team who have been such great partners in this endeavor.

Growth in Research at the SHM

Papers published in JHM represent only the tip of the iceberg of research in hospital medicine. This year we had 176 abstracts submitted for presentation at our annual meeting in May. These abstracts in research, innovations, and vignettes reflect the enthusiasm, interest, and dedication of many hospitalists. I am always impressed as I read the abstracts and wander through the poster session at the amount of work and creativity represented.

What is even more impressive about these abstracts is that they reflect the breadth of hospital medicine—adult medicine and pediatrics; academic and community hospitals; clinical work and administration; internal medicine, family practice, and pediatrics; disease-specific treatments; and system approaches to care. This year for the first time we will publish the abstracts in a supplement to both The Hospitalist and JHM. All hospitalists who have an abstract accepted for the meeting will be able to cite their work. The supplement marks another advance for our society and field.

I hope that many of you who have submitted abstracts will consider turning them into manuscripts and submitting to JHM. Abstracts whet the appetite to know more, and papers provide the details to improve care.

The Importance of Pursuing Research at SHM

These efforts are critical to our field and represent one visible way that SHM pursues research. SHM must pursue research because it helps define our field. We must ensure that the questions asked are relevant to hospital medicine and that the interventions tested and solutions advocated reflect the real world.

While we welcome anyone to pursue research in hospital medicine and how to improve the care of hospitalized patients, we must ensure that hospitalists play a key role in conducting this research. Research conducted by non-hospitalists may advocate for unrealistic interventions or result in research that is not representative of our field. As the organization that represents hospitalists, SHM can also ensure that research asks the right questions and finds practical solutions with real-world applicability.

For example, SHM should promote:

- Research about best practices, innovations in care delivery, and implementation of known beneficial treatments;

- New approaches to system issues, including error reduction, inpatient-outpatient communication, information systems and transitions; and

- Clinical trials of common inpatient conditions, such as pneumonia and acute decompensated heart failure.

By playing a central role in research, SHM can also advocate for community-based initiatives that ensure research occurs where the majority of patients are cared for.

If we fail to lead in research someone else will, and others will be able to define best practices in hospital medicine. We should not let others define hospital medicine. We took a critical step in defining our field by developing and publishing the core competencies in hospital medicine. Research will be another important way for us to delineate our field. Finally, if SHM does not pursue research we risk losing our academic credentials as a society and a field. Ultimately it will be difficult to succeed as a field and specialty if we do not succeed in academic centers because that is where students and residents—the hospitalists of tomorrow—choose their careers. Hospitalists are great teachers and role models for students and residents. However, in order to ensure that the role models and teachers flourish, we need to pursue research so hospital medicine remains a legitimate part of the academic mission.

SHM Research Initiatives

Although JHM may be the most visible sign of research at SHM, it is not the only one. Research projects directly sponsored by SHM include a demonstration project evaluating interventions to improve care of patients with heart failure, a planned survey of hospitalist involvement in managing heart failure in the emergency department and observation units, and a project to develop and evaluate a tool kit to support discharge planning for elders.

I am especially proud that each of these projects involves community and academic hospitalist programs. The SHM Research Committee, chaired by Andy Auerbach, MD, has played a key role in defining a vision for research at the SHM, and I thank Dr. Auerbach and the committee for their efforts and guidance. I am also delighted that SHM recently hired Kathleen Kerr as a senior advisor for research. Kerr’s extensive experience with hospitalists, quality improvement, and research at the University of California, San Francisco, makes her the ideal person to help spearhead this important initiative at SHM. Taken together we have a strong foundation for our research initiative and ensuring that SHM plays a key role in helping to define and shepherd research in hospital medicine.

The Future of Research at SHM

As difficult as it is to publish the first issue of a new journal, the real challenge will be to publish the second issue and beyond. Sustaining the quality and breadth reflected in the first issue will take the combined efforts of the entire editorial staff at JHM, all hospitalists, and all others interested in improving the care of hospitalized patients.

The good news is that, as reflected in our abstract submissions, there is a deep pool of good work in hospital medicine to write about and publish. The other good news is that our field is one in which many of the best innovations and much of the important research comes from community settings and not just academic centers. In fact our strength in research comes from the fact that we can draw from both academic and community programs to create new, “generalizable” knowledge. An even greater strength is when these programs collaborate to take advantage of the best that each has to offer to research.

I encourage each of us to think about the work we are doing and to think about what innovative, creative, or successful program should be shared and implore each of us to submit our work to JHM. Help make JHM the best source for innovation and best practices in hospital medicine. Help shape JHM into the best possible journal it can be—the one you open right away and read through because it is so relevant to your practice.

As our field grows we will look back on this moment as a critical landmark in the development of our field. Hold on to your first issue: It may be a valuable collector’s item when volume 50 is being published and JHM is one of the world’s leading journals. What practices will we look back on and laugh at? What practices will have survived years of scrutiny? What will our field look like? Only time will tell. Read JHM to find out. TH

SHM President Dr. Pantilat is an associate professor of clinical medicine at the University of California at San Francisco.

In February we experienced a landmark in the development of the field of hospital medicine with the publication of the premiere issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM). The debut of JHM demonstrates that hospital medicine is maturing as a field and—even more importantly—that it is developing as a new field with specific issues relevant to its practice.

It is difficult to overestimate the critical role that our journal will play in the growth of our field. The content for the inaugural issue of JHM reflects the depth and breadth of hospital medicine—community acquired pneumonia, palliative care, gastrointestinal bleeding, geriatrics, and a patient’s perspective on hospital care. The many authors who submitted their manuscripts took a leap of faith that our journal would be a respected and widely read vehicle for disseminating their hard work. This leap is even greater given that JHM is not yet listed in PubMed. Nonetheless these authors believe that JHM will thrive, be well read, and influence practice and patient care.

I agree because I know the talent of hospitalists and the potential of our field. The first issue of JHM also included a supplement devoted to the core competencies in hospital medicine. These core competencies represent another milestone in the growth of our field. With the core competencies we have outlined the specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes that define who we are and what we do.

Bringing a journal from concept to reality takes a Herculean effort by many people. I especially want to thank Mark Williams, MD, editor of JHM, for his leadership and grand vision for JHM that reflects our society and field so well. I also want to thank the associate editors and editorial board for giving their time, energy, and expertise to our journal.

I want to share my gratitude and appreciation for Larry Wellikson, MD, the CEO of SHM, who took an idea and mandate presented by the SHM Board of Directors and “operationalized” it in the most effective way. Finally, I want to thank Vickie Thaw, associate publisher at John Wiley & Sons, and her publishing team who have been such great partners in this endeavor.

Growth in Research at the SHM

Papers published in JHM represent only the tip of the iceberg of research in hospital medicine. This year we had 176 abstracts submitted for presentation at our annual meeting in May. These abstracts in research, innovations, and vignettes reflect the enthusiasm, interest, and dedication of many hospitalists. I am always impressed as I read the abstracts and wander through the poster session at the amount of work and creativity represented.

What is even more impressive about these abstracts is that they reflect the breadth of hospital medicine—adult medicine and pediatrics; academic and community hospitals; clinical work and administration; internal medicine, family practice, and pediatrics; disease-specific treatments; and system approaches to care. This year for the first time we will publish the abstracts in a supplement to both The Hospitalist and JHM. All hospitalists who have an abstract accepted for the meeting will be able to cite their work. The supplement marks another advance for our society and field.

I hope that many of you who have submitted abstracts will consider turning them into manuscripts and submitting to JHM. Abstracts whet the appetite to know more, and papers provide the details to improve care.

The Importance of Pursuing Research at SHM

These efforts are critical to our field and represent one visible way that SHM pursues research. SHM must pursue research because it helps define our field. We must ensure that the questions asked are relevant to hospital medicine and that the interventions tested and solutions advocated reflect the real world.

While we welcome anyone to pursue research in hospital medicine and how to improve the care of hospitalized patients, we must ensure that hospitalists play a key role in conducting this research. Research conducted by non-hospitalists may advocate for unrealistic interventions or result in research that is not representative of our field. As the organization that represents hospitalists, SHM can also ensure that research asks the right questions and finds practical solutions with real-world applicability.

For example, SHM should promote:

- Research about best practices, innovations in care delivery, and implementation of known beneficial treatments;

- New approaches to system issues, including error reduction, inpatient-outpatient communication, information systems and transitions; and

- Clinical trials of common inpatient conditions, such as pneumonia and acute decompensated heart failure.

By playing a central role in research, SHM can also advocate for community-based initiatives that ensure research occurs where the majority of patients are cared for.

If we fail to lead in research someone else will, and others will be able to define best practices in hospital medicine. We should not let others define hospital medicine. We took a critical step in defining our field by developing and publishing the core competencies in hospital medicine. Research will be another important way for us to delineate our field. Finally, if SHM does not pursue research we risk losing our academic credentials as a society and a field. Ultimately it will be difficult to succeed as a field and specialty if we do not succeed in academic centers because that is where students and residents—the hospitalists of tomorrow—choose their careers. Hospitalists are great teachers and role models for students and residents. However, in order to ensure that the role models and teachers flourish, we need to pursue research so hospital medicine remains a legitimate part of the academic mission.

SHM Research Initiatives

Although JHM may be the most visible sign of research at SHM, it is not the only one. Research projects directly sponsored by SHM include a demonstration project evaluating interventions to improve care of patients with heart failure, a planned survey of hospitalist involvement in managing heart failure in the emergency department and observation units, and a project to develop and evaluate a tool kit to support discharge planning for elders.

I am especially proud that each of these projects involves community and academic hospitalist programs. The SHM Research Committee, chaired by Andy Auerbach, MD, has played a key role in defining a vision for research at the SHM, and I thank Dr. Auerbach and the committee for their efforts and guidance. I am also delighted that SHM recently hired Kathleen Kerr as a senior advisor for research. Kerr’s extensive experience with hospitalists, quality improvement, and research at the University of California, San Francisco, makes her the ideal person to help spearhead this important initiative at SHM. Taken together we have a strong foundation for our research initiative and ensuring that SHM plays a key role in helping to define and shepherd research in hospital medicine.

The Future of Research at SHM

As difficult as it is to publish the first issue of a new journal, the real challenge will be to publish the second issue and beyond. Sustaining the quality and breadth reflected in the first issue will take the combined efforts of the entire editorial staff at JHM, all hospitalists, and all others interested in improving the care of hospitalized patients.

The good news is that, as reflected in our abstract submissions, there is a deep pool of good work in hospital medicine to write about and publish. The other good news is that our field is one in which many of the best innovations and much of the important research comes from community settings and not just academic centers. In fact our strength in research comes from the fact that we can draw from both academic and community programs to create new, “generalizable” knowledge. An even greater strength is when these programs collaborate to take advantage of the best that each has to offer to research.

I encourage each of us to think about the work we are doing and to think about what innovative, creative, or successful program should be shared and implore each of us to submit our work to JHM. Help make JHM the best source for innovation and best practices in hospital medicine. Help shape JHM into the best possible journal it can be—the one you open right away and read through because it is so relevant to your practice.

As our field grows we will look back on this moment as a critical landmark in the development of our field. Hold on to your first issue: It may be a valuable collector’s item when volume 50 is being published and JHM is one of the world’s leading journals. What practices will we look back on and laugh at? What practices will have survived years of scrutiny? What will our field look like? Only time will tell. Read JHM to find out. TH

SHM President Dr. Pantilat is an associate professor of clinical medicine at the University of California at San Francisco.

In February we experienced a landmark in the development of the field of hospital medicine with the publication of the premiere issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM). The debut of JHM demonstrates that hospital medicine is maturing as a field and—even more importantly—that it is developing as a new field with specific issues relevant to its practice.

It is difficult to overestimate the critical role that our journal will play in the growth of our field. The content for the inaugural issue of JHM reflects the depth and breadth of hospital medicine—community acquired pneumonia, palliative care, gastrointestinal bleeding, geriatrics, and a patient’s perspective on hospital care. The many authors who submitted their manuscripts took a leap of faith that our journal would be a respected and widely read vehicle for disseminating their hard work. This leap is even greater given that JHM is not yet listed in PubMed. Nonetheless these authors believe that JHM will thrive, be well read, and influence practice and patient care.

I agree because I know the talent of hospitalists and the potential of our field. The first issue of JHM also included a supplement devoted to the core competencies in hospital medicine. These core competencies represent another milestone in the growth of our field. With the core competencies we have outlined the specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes that define who we are and what we do.

Bringing a journal from concept to reality takes a Herculean effort by many people. I especially want to thank Mark Williams, MD, editor of JHM, for his leadership and grand vision for JHM that reflects our society and field so well. I also want to thank the associate editors and editorial board for giving their time, energy, and expertise to our journal.

I want to share my gratitude and appreciation for Larry Wellikson, MD, the CEO of SHM, who took an idea and mandate presented by the SHM Board of Directors and “operationalized” it in the most effective way. Finally, I want to thank Vickie Thaw, associate publisher at John Wiley & Sons, and her publishing team who have been such great partners in this endeavor.

Growth in Research at the SHM

Papers published in JHM represent only the tip of the iceberg of research in hospital medicine. This year we had 176 abstracts submitted for presentation at our annual meeting in May. These abstracts in research, innovations, and vignettes reflect the enthusiasm, interest, and dedication of many hospitalists. I am always impressed as I read the abstracts and wander through the poster session at the amount of work and creativity represented.

What is even more impressive about these abstracts is that they reflect the breadth of hospital medicine—adult medicine and pediatrics; academic and community hospitals; clinical work and administration; internal medicine, family practice, and pediatrics; disease-specific treatments; and system approaches to care. This year for the first time we will publish the abstracts in a supplement to both The Hospitalist and JHM. All hospitalists who have an abstract accepted for the meeting will be able to cite their work. The supplement marks another advance for our society and field.

I hope that many of you who have submitted abstracts will consider turning them into manuscripts and submitting to JHM. Abstracts whet the appetite to know more, and papers provide the details to improve care.

The Importance of Pursuing Research at SHM

These efforts are critical to our field and represent one visible way that SHM pursues research. SHM must pursue research because it helps define our field. We must ensure that the questions asked are relevant to hospital medicine and that the interventions tested and solutions advocated reflect the real world.

While we welcome anyone to pursue research in hospital medicine and how to improve the care of hospitalized patients, we must ensure that hospitalists play a key role in conducting this research. Research conducted by non-hospitalists may advocate for unrealistic interventions or result in research that is not representative of our field. As the organization that represents hospitalists, SHM can also ensure that research asks the right questions and finds practical solutions with real-world applicability.

For example, SHM should promote:

- Research about best practices, innovations in care delivery, and implementation of known beneficial treatments;

- New approaches to system issues, including error reduction, inpatient-outpatient communication, information systems and transitions; and

- Clinical trials of common inpatient conditions, such as pneumonia and acute decompensated heart failure.

By playing a central role in research, SHM can also advocate for community-based initiatives that ensure research occurs where the majority of patients are cared for.

If we fail to lead in research someone else will, and others will be able to define best practices in hospital medicine. We should not let others define hospital medicine. We took a critical step in defining our field by developing and publishing the core competencies in hospital medicine. Research will be another important way for us to delineate our field. Finally, if SHM does not pursue research we risk losing our academic credentials as a society and a field. Ultimately it will be difficult to succeed as a field and specialty if we do not succeed in academic centers because that is where students and residents—the hospitalists of tomorrow—choose their careers. Hospitalists are great teachers and role models for students and residents. However, in order to ensure that the role models and teachers flourish, we need to pursue research so hospital medicine remains a legitimate part of the academic mission.

SHM Research Initiatives

Although JHM may be the most visible sign of research at SHM, it is not the only one. Research projects directly sponsored by SHM include a demonstration project evaluating interventions to improve care of patients with heart failure, a planned survey of hospitalist involvement in managing heart failure in the emergency department and observation units, and a project to develop and evaluate a tool kit to support discharge planning for elders.

I am especially proud that each of these projects involves community and academic hospitalist programs. The SHM Research Committee, chaired by Andy Auerbach, MD, has played a key role in defining a vision for research at the SHM, and I thank Dr. Auerbach and the committee for their efforts and guidance. I am also delighted that SHM recently hired Kathleen Kerr as a senior advisor for research. Kerr’s extensive experience with hospitalists, quality improvement, and research at the University of California, San Francisco, makes her the ideal person to help spearhead this important initiative at SHM. Taken together we have a strong foundation for our research initiative and ensuring that SHM plays a key role in helping to define and shepherd research in hospital medicine.

The Future of Research at SHM

As difficult as it is to publish the first issue of a new journal, the real challenge will be to publish the second issue and beyond. Sustaining the quality and breadth reflected in the first issue will take the combined efforts of the entire editorial staff at JHM, all hospitalists, and all others interested in improving the care of hospitalized patients.

The good news is that, as reflected in our abstract submissions, there is a deep pool of good work in hospital medicine to write about and publish. The other good news is that our field is one in which many of the best innovations and much of the important research comes from community settings and not just academic centers. In fact our strength in research comes from the fact that we can draw from both academic and community programs to create new, “generalizable” knowledge. An even greater strength is when these programs collaborate to take advantage of the best that each has to offer to research.

I encourage each of us to think about the work we are doing and to think about what innovative, creative, or successful program should be shared and implore each of us to submit our work to JHM. Help make JHM the best source for innovation and best practices in hospital medicine. Help shape JHM into the best possible journal it can be—the one you open right away and read through because it is so relevant to your practice.

As our field grows we will look back on this moment as a critical landmark in the development of our field. Hold on to your first issue: It may be a valuable collector’s item when volume 50 is being published and JHM is one of the world’s leading journals. What practices will we look back on and laugh at? What practices will have survived years of scrutiny? What will our field look like? Only time will tell. Read JHM to find out. TH

SHM President Dr. Pantilat is an associate professor of clinical medicine at the University of California at San Francisco.

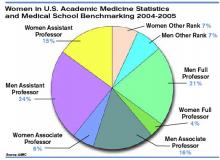

The Gender Factor

In 1980 women physicians represented 11.6% of all U.S. physicians. In 2003 they represented 26% of the total physician population.1 Drawing from the ranks of internal medicine and pediatrics, in which women physicians represent 41.8% and 65.6% of all residents, hospital medicine will likely reap the benefits of these increasing numbers.2 Indeed, hospital medicine appears to offer many advantages for women: an intrinsically collaborative working environment, flexible work hours, and the opportunity to participate in forming the structure for a new specialty. But do enough opportunities for advancement exist in this relatively young specialty?

The Hospitalist recently talked with women hospitalists, SHM leadership, and a researcher on gender discrimination in academic medicine. All shared their perceptions about how hospital medicine fares regarding inclusion of women—both in the ranks and in leadership positions.

A Career that Works

“As a woman hospitalist, I’ve had many opportunities to advocate for patient safety and quality being the primary guiding principle in reorganizing care,” says Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, associate chair, Department of Internal Medicine and an academic hospitalist at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital, Ann Arbor, Mich. “I think as women we do juggle a lot of responsibilities, but I think those skills probably uniquely position us to be very effective in managing groups and being members and leaders of teams.”

As a mother of two young children, Dr. Halasyamani enjoys the flexibility of her current position. “I have a very busy life, but I make sure I have time to do the other parts of my life because those will never come back to me. Today, I went to my daughter’s school and helped her class with some of their math problems, and I chair a multicultural committee at her school as well.”

She finds that she brings the same type of organizational skills to both her working and family life. “Whether it’s preparing for a school assembly or preparing for a patient safety committee meeting,” explains Dr. Halasyamani, “there just isn’t time to focus on what is not important or to come unprepared. Every minute is incredibly precious.”

Like Dr. Halasyamani, Sheri Chernetsky Tejedor, MD, a clinical instructor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, has also been able to carve out a clinical and academic track that suits her present needs for family time. Under a supportive supervisor, Mark Williams, MD, FACP, professor of medicine and director, Emory Hospital Medicine Unit, and editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Tejedor has worked part time as a hospitalist in a nearby community hospital; has worked in academia, including writing and research in quality improvement; and essentially has been a full-time mother when she is home. “I haven’t felt that any doors have closed, and the only ones that have closed are ones that I’ve closed myself—just accepting that I can’t do everything,” says Dr. Tejedor.

According to the AMA, 62.6% of all women physicians fall within the specialties of internal medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, psychiatry, and anesthesiology.1 That is one reason the numbers of women in hospital medicine are also increasing, says Larry Wellikson, MD, FACP, CEO of SHM.

“Because hospitalists come from the ranks of pediatricians and internists, as those specialties attract more women, I think they will also find hospital medicine very attractive as they are looking for their career choice,” says Dr. Wellikson.

—Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD

Approaching Parity?

Although SHM does not currently keep statistics on percentages of women in the organization, many hospitalist services point to increasing numbers of women in their departments. For instance, SHM Past President Robert Wachter, MD, FACP, director of the hospitalist group at the University of California, San Francisco, reports that 57% (12 out of 21) of the hospitalists in his group are women. This majority does not stem from deliberate recruiting on his part.

“My goal here has been to recruit and retain the best people. I couldn’t care less whether they are women or men,” says Dr. Wachter. “I would begin to care if we were so skewed in one direction or the other that it might indicate that we weren’t providing a positive environment for either women or men. But our group has grown organically and it has just turned out that we’ve ended up with more women than men.”

Leadership Opportunities in Medicine

While overall increases in the numbers of women physicians can be seen as a hopeful sign, these percentages may mask the reality for women trying to achieve parity in leadership roles. In fact, the percentages of women in leadership positions in academic medicine remain low: For example, only 11% of department chairs in medical schools are women, and 10% of medical school deans are women.1

A higher percentage of women in a particular specialty does not necessarily translate into better advancement opportunities, according to statistician Arlene S. Ash, PhD, a research professor in the Department of General Internal Medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine. “Sadly,” she says, “the main thing you can predict about a specialty with more women is that it will be less well-paid overall.”

Many committee assignments and semi-leadership positions in the academic medicine arena are informally awarded, and they often go to men. “Often these are innocent decisions,” explains Dr. Ash. “The positions carry perks, and perhaps some regular funding, and can be stepping stones to later promotion, but they usually go to the person who pops into the mind of the administrator making the decision.”

It takes “incredible vigilance,” says Dr. Ash, “to see your way past the prejudiced lens with which we all, having grown up in this society, view the relative value of men’s and women’s contributions.”

To achieve more parity for women, Dr. Ash believes it’s necessary to more closely scrutinize and to set standards for leadership selection processes. Currently, she explains, “There is no comprehensive attempt to cast a wide net, to consider all who might be appropriate, and to ensure a non-sexist, non-biased process for choosing people to get such positions. Even in departments with more than 50% women, and even where the problem is recognized, most of these ‘gateway’ opportunities still go to guys.”

Hospitalists Breaking the Mold?

Those interviewed believe hospital medicine, as a new specialty, may have a chance to break the traditional molds established by more entrenched medical school specialties.

“We’re inventing this entire thing [the hospital medicine specialty] as we go along, so we have not had time to develop an ‘old boys’ network,’” quips Dr. Wachter. “The hope is that if you start a field now, it will not develop along those lines. As we look at those holding leadership roles at individual hospitals and in the society, you find that talented people rise to the top. If you start with a neutral playing field without the tradition and history of the smoke-filled room, it turns out that people sort out on their skills and their interests.”

“I think hospital medicine is a very accessible profession for women on a number of levels,” says Dr. Wellikson. “This is a young, growing, evolving field—as opposed to some of the more static fields in medicine, like orthopedics or thoracic surgery. One of the hallmarks of hospital medicine is creating true teams of health professionals. Women come in as equals, with good ideas, and I think this is mirrored on the SHM Board.”

Currently, four of the 12 SHM board members are women; Jean Huddleston, MD, of the Mayo Clinic is a past president; and the incoming president, Mary Jo Gorman, MD, of IPC, is also a woman. “We [the Society of Hospital Medicine] are very much an open tent,” remarks Dr. Wellikson.

According to Sylvia Cheney McKean, MD, FACP, medical director of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Faulkner Hospitalist Service in Boston, there are pros and cons to hospital medicine being a new specialty.

“In some ways, because [hospital medicine] is a new specialty, women may have been given the opportunity to lead hospitalist programs because early hospitalist services—at least initially—were viewed as experimental,” she says. “Many hospital leaders hired hospitalists to function as ‘super residents’ rather than as leaders. So, therefore, academic institutions didn’t really feel that they had much to lose by hiring women versus men, and many hospitalist leaders—male and female—found themselves functioning as middle managers without necessarily having much input into their job descriptions.

“Even in 2006 some physician administrators hire hospitalists with the expectation that turnover is inevitable as physicians advance to other specialties,” continues Dr. McKean. “Hospital administrators and residency directors may not understand the evolving role of hospitalists as change agents in the hospital setting and may not recognize that hospitalists offer special expertise in addition to on-site availability. So it’s a two-edged sword. A lot of hospital medicine programs, because they have not only young physician leaders, but also proportionately more female physician leaders, may find that they really cannot have the same amount of clout as other established specialties within the department of medicine hierarchy.”

Dr. Halasyamani believes that the male hierarchy may be changing. In hospital medicine, she notes, “because the emphasis in inpatient care delivery is so team focused, the leaders in hospital medicine who are able to best meet those goals and have those skills are really the ones who are being given the most opportunity. If the structures within organizations are very hierarchical, then care delivery ends up looking that way. But if the leadership and decision-making structures are more collaborative, then I think care reflects that.”

At her institution, Dr. Halasyamani has had numerous opportunities to help build some of those new structures. For example, in the past year, she helped form an institutional quality and patient safety collaborative practice team, which she chaired jointly with the head of nursing. The team “brings together people who touch the patient; they identify the barriers in delivering the type of care that we want to be proud of every time, and to help solve those problems.”

Possible Pitfalls

Can hospital medicine, in fact, succeed in developing new leadership paradigms? Much will depend on consciously constructing new systems for nurturing talent and leaders. “You really have to think through your mechanisms for recognizing and rewarding achievement and ask if those mechanisms encourage the behaviors you want to encourage, or do they disadvantage people who do the work that you most want done?” says Dr. Ash.

For example, she says, the collaborative nature of hospital medicine can create problems with career advancement. “To do something meaningful, you may need to involve 20 people on a five-year project,” she explains. “How do you ensure that those people don’t get punished for choosing that work?”

Dr. Ash, together with Boston University colleague Phyllis L. Carr, MD, and Linda Pololi, MD, from Brandeis University (the principal investigator) has started a Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation-funded project to “try to change the culture of academic medicine so that it will better encourage and reward collaborative research,” she says. “This change should benefit the entire academic enterprise—although its immediate goal is to make a common career track for women more viable.

“I want to fix a generic problem about the failure to reward certain kinds of highly desirable activities,” says Dr. Ash. “The current reward system hurts women more than men, but I’m not the slightest bit unhappy—it would be a wonderful thing, actually—for men who do collaborative research to also get the career benefits they deserve.”

Advice for Leaders and Women

Are opportunities for women hospitalists improving? Dr. McKean thinks that “hierarchies exist in hospitals, where surgeons are more powerful than physicians in the department of medicine, which has its own internal hierarchy. I see many more women interviewing for internal medicine slots. And, you could say, that’s great, it’s equalizing out. But I wonder if all it’s going to mean is that the pay scale will go down. I think that’s a real consideration. What we’re seeing now is that the starting salary for physician assistants in the hospital may be more than the starting salary for some physicians in primary care. Adding more women [to a specialty] may not change inequalities. The key is adding more women in the highest leadership positions.”

“The whole process of growing talent needs to be done in a take-control sort of way,” says Dr. Ash. There is a predictable, ongoing need to fill leadership positions, she notes, and “not enough good thought about how to systematically reach out to the entire potential talent pool.”

“Mentorship is very important,” emphasizes Dr. McKean. Her own career as a physician was characterized early on, she says, by a lack of support and mentorship. Twenty-five years later, she hopes things are beginning to change and hospital medicine may in fact set the standard for other specialties for both male and female physicians.

“Medicine is always going to be unpredictable,” she continues. “It will always be stressful. There will be acutely ill patients, and people will return [to the hospital] with unanticipated problems. You cannot change this reality. But you can change how things are structured. The more the Society of Hospital Medicine can give people the tools to identify modifiable risk factors in their own practices, help leaders of the hospitalist services analyze what works and what doesn’t work, and allow for as much diversity as possible within each service, I think that a career in hospital medicine will be sustainable and extremely satisfying, and that people will get promoted. They will find different niches in which they are expert.”

To that end, with Win Whitcomb, MD (SHM co-founder), Dr. McKean approached the SHM to charge a task force to identify what makes for a long and satisfying career in hospital medicine and to develop practice standards. The job-person fit is important, and she advises young women hospitalists to take a look at themselves, define what is important, and then “tailor a schedule around that. If it is important to you to be teaching residents, for example, then you need to be in an academic program. If it is more important to have time off, and to work shifts, then you might want to work at a community hospital. There are a lot of different models,” she says “so you have to look at yourself and your husband and the other issues you have to grapple with in addition to your career.”

Above all Dr. McKean urges women (as well as men) to be receptive to advocates or mentors within their organizations.

Going Forward

Overall, Dr. Wachter sees “the nature of the field [of hospital medicine] as one that involves a lot of collaboration and multidisciplinary work seems to draw a certain kind of person. The kind of person who is most happy and successful in our field is one who likes working closely with nurses, physical therapists, social workers, and hospital administrators, and recognizes that the quality of care and patients’ outcomes are going to be, in large part, dependent on how well that team functions.”

Many younger women and men hospitalists are finding that the job-person fit contributes to a fulfilling work/life balance.

“I chose this field because I was interested in inpatient care,” says Dr. Tejedor, and the flexibility offered by her institution has reinforced that choice. “This [hospital medicine] is a great way to have the best of everything.” TH

Writer Gretchen Henkel is based in California.

References

- Women in Medicine Statistics. Prepared by the Women Physicians Congress from Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US, 2005 ed., Chicago. AMA Press. Available at www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/19/wimstats2005.pdf. Last accessed January 9, 2005.

- Table 2. Distribution of Residents by Specialty, 1994 Compared to 2004. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Medical School Benchmarking, 2004-2005. Association of American Medical Colleges; page 12. Available at www.aamc.org/members/wim/statistics/stats05/wimstats2005.pdf. Last accessed January 9, 2005.

In 1980 women physicians represented 11.6% of all U.S. physicians. In 2003 they represented 26% of the total physician population.1 Drawing from the ranks of internal medicine and pediatrics, in which women physicians represent 41.8% and 65.6% of all residents, hospital medicine will likely reap the benefits of these increasing numbers.2 Indeed, hospital medicine appears to offer many advantages for women: an intrinsically collaborative working environment, flexible work hours, and the opportunity to participate in forming the structure for a new specialty. But do enough opportunities for advancement exist in this relatively young specialty?

The Hospitalist recently talked with women hospitalists, SHM leadership, and a researcher on gender discrimination in academic medicine. All shared their perceptions about how hospital medicine fares regarding inclusion of women—both in the ranks and in leadership positions.

A Career that Works

“As a woman hospitalist, I’ve had many opportunities to advocate for patient safety and quality being the primary guiding principle in reorganizing care,” says Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, associate chair, Department of Internal Medicine and an academic hospitalist at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital, Ann Arbor, Mich. “I think as women we do juggle a lot of responsibilities, but I think those skills probably uniquely position us to be very effective in managing groups and being members and leaders of teams.”

As a mother of two young children, Dr. Halasyamani enjoys the flexibility of her current position. “I have a very busy life, but I make sure I have time to do the other parts of my life because those will never come back to me. Today, I went to my daughter’s school and helped her class with some of their math problems, and I chair a multicultural committee at her school as well.”

She finds that she brings the same type of organizational skills to both her working and family life. “Whether it’s preparing for a school assembly or preparing for a patient safety committee meeting,” explains Dr. Halasyamani, “there just isn’t time to focus on what is not important or to come unprepared. Every minute is incredibly precious.”

Like Dr. Halasyamani, Sheri Chernetsky Tejedor, MD, a clinical instructor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, has also been able to carve out a clinical and academic track that suits her present needs for family time. Under a supportive supervisor, Mark Williams, MD, FACP, professor of medicine and director, Emory Hospital Medicine Unit, and editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Tejedor has worked part time as a hospitalist in a nearby community hospital; has worked in academia, including writing and research in quality improvement; and essentially has been a full-time mother when she is home. “I haven’t felt that any doors have closed, and the only ones that have closed are ones that I’ve closed myself—just accepting that I can’t do everything,” says Dr. Tejedor.

According to the AMA, 62.6% of all women physicians fall within the specialties of internal medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, psychiatry, and anesthesiology.1 That is one reason the numbers of women in hospital medicine are also increasing, says Larry Wellikson, MD, FACP, CEO of SHM.

“Because hospitalists come from the ranks of pediatricians and internists, as those specialties attract more women, I think they will also find hospital medicine very attractive as they are looking for their career choice,” says Dr. Wellikson.

—Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD

Approaching Parity?

Although SHM does not currently keep statistics on percentages of women in the organization, many hospitalist services point to increasing numbers of women in their departments. For instance, SHM Past President Robert Wachter, MD, FACP, director of the hospitalist group at the University of California, San Francisco, reports that 57% (12 out of 21) of the hospitalists in his group are women. This majority does not stem from deliberate recruiting on his part.

“My goal here has been to recruit and retain the best people. I couldn’t care less whether they are women or men,” says Dr. Wachter. “I would begin to care if we were so skewed in one direction or the other that it might indicate that we weren’t providing a positive environment for either women or men. But our group has grown organically and it has just turned out that we’ve ended up with more women than men.”

Leadership Opportunities in Medicine

While overall increases in the numbers of women physicians can be seen as a hopeful sign, these percentages may mask the reality for women trying to achieve parity in leadership roles. In fact, the percentages of women in leadership positions in academic medicine remain low: For example, only 11% of department chairs in medical schools are women, and 10% of medical school deans are women.1