User login

Leading for High Reliability During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Pilot Quality Improvement Initiative to Identify Challenges Faced and Lessons Learned

From the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (all authors), and Cognosante, LLC, Falls Church, VA (Dr. Murray, Dr. Sawyer, and Jessica Fankhauser).

Abstract

Objective: The COVID-19 pandemic posed unprecedented leadership challenges to health care organizations worldwide, especially those on the journey to high reliability. The objective of this pilot quality improvement initiative was to describe the experiences of medical center leaders continuing along the journey to high reliability during the pandemic.

Methods: A convenience sample of Veterans Health Administration medical center directors at facilities that had initiated the journey to high reliability prior to or during the COVID-19 pandemic were asked to complete a confidential survey to explore the challenges experienced and lessons learned.

Results: Of the 35 potential participants, 15 completed the confidential web-based survey. Five major themes emerged from participants’ responses: (1) managing competing priorities, (2) staying committed, (3) adapting and overcoming, (4) prioritizing competing demands, and (5) maintaining momentum.

Conclusion: This pilot quality improvement initiative provides some insight into the challenges experienced and lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic to help inform health care leaders’ responses during crises they may encounter along the journey to becoming a high reliability organization.

Keywords: HRO, leadership, patient safety.

Health care leaders worldwide agree that the

Maintaining continuous progress toward advancing high reliability organization (HRO) principles and practices can be especially challenging during crises of unprecedented scale such as the pandemic. HROs must be continually focused on achieving safety, quality, and efficiency goals by attending to the 3 pillars of HRO: culture, leadership, and continuous process improvement. HROs promote a culture where all staff across the organization watch for and report any unsafe conditions before these conditions pose a greater risk in the workplace. Hospital leaders, from executives to frontline managers, must be cognizant of all systems and processes that have the potential to affect patient care.12 All of the principles of HROs must continue without fail to ensure patient safety; these principles include preoccupation with failure, anticipating unexpected risks, sensitivity to dynamic and ever-changing operations, avoiding oversimplifications of identified problems, fostering resilience across the organization, and deferring to those with the expertise to make the best decisions regardless of position, rank, or title.12,13 Given the demands faced by leaders during crises with unprecedented disruption to normal operating procedures, it can be especially difficult to identify systemic challenges and apply lessons learned in a timely manner. However, it is critical to identify such lessons in order to continuously improve and to increase preparedness for subsequent crises.13,14

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic’s unprecedented nature in recent history, a review of the literature produced little evidence exploring the challenges experienced and lessons learned by health care leaders, especially as it relates to implementing or sustaining HRO journeys during the COVID-19 pandemic. Related literature published to date consists of editorials on reliability, uncertainty, and the management of errors15; patient safety and high reliability preventive strategies16; and authentic leadership.17 Five viewpoints were published on HROs and maladaptive stress behaviors,18 mindful organizing and organizational reliability,19 the practical essence of HROs,20 embracing principles of HROs in crisis,8 and using observation and high reliability strategies when facing an unprecedented safety threat.21 Finally, the authors identified 2 studies that used a qualitative research approach to explore leadership functions within an HRO when managing crises22 and organizational change in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.23 Due to the paucity of available information, the authors undertook a pilot quality improvement (QI) initiative to address this knowledge gap.

The aim of this initiative was to gain a better understanding of the challenges experienced, lessons learned, and recommendations to be shared by VHA medical center directors (MCDs) of health care facilities that had initiated the journey to high reliability before or during the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors hope that this information will help health care leaders across both governmental and nongovernmental organizations, nationally and globally, to prepare for future pandemics, other unanticipated crises (eg, natural disasters, terrorist attacks), and major change initiatives (eg, electronic health record modernization) that may affect the delivery of safe, high-quality, and effective patient care. The initiative is described using the SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines.24,25

Methods

Survey

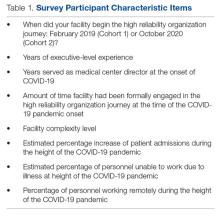

We used a qualitative approach and administered a confidential web-based survey, developed by the project team, to VHA MCDs at facilities that had initiated the journey to high reliability before or during the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey consisted of 8 participant characteristic questions (Table 1) and 4 open-ended questions. The open-ended questions were designed to encourage MCD participants to freely provide detailed descriptions of the challenges experienced, lessons learned, recommendations for other health care leaders, and any additional information they believed was relevant.26,27 Participants were asked to respond to the following items:

- Please describe any challenges you experienced while in the role of MCD at a facility that initiated implementation of HRO principles and practices prior to (February 2020) or during (March 2020–September 2021) the initial onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- What are some lessons that you learned when responding to the COVID-19 pandemic while on the journey to high reliability?

- What recommendations would you like to make to other health care leaders to enable them to respond effectively to crises while on the journey to high reliability?

- Please provide any additional information that would be of value.

An invitation to participate in this pilot QI initiative was sent via e-mail to 35 potential participants, who were all MCDs at Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 facilities. The invitation was sent on June 17, 2022, by a VHA senior High Reliability Enterprise Support government team member not directly involved with the initiative.

The invitation included the objective of the initiative, estimated time to complete the confidential web-based survey, time allotted for responses to be submitted, and a link to the survey should potential participants agree to participate. Potential participants were informed that their involvement was voluntary, based on their willingness to participate and available time to complete the survey. Finally, the invitation noted that any comments provided would remain confidential and nonattributional for the purpose of publishing and presenting. The inclusion criteria for participation were: (1) serving

Data Gathering and Analysis

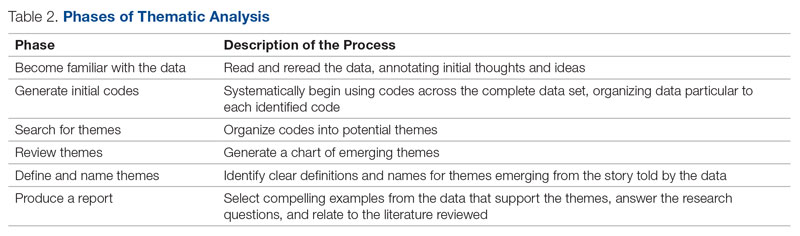

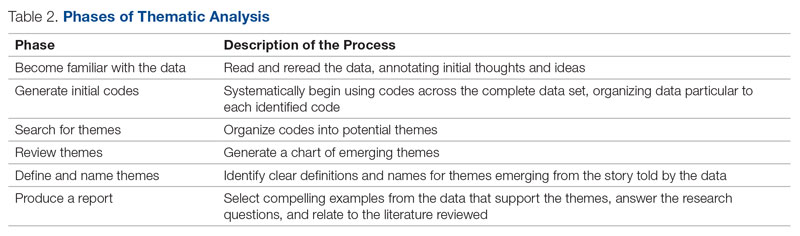

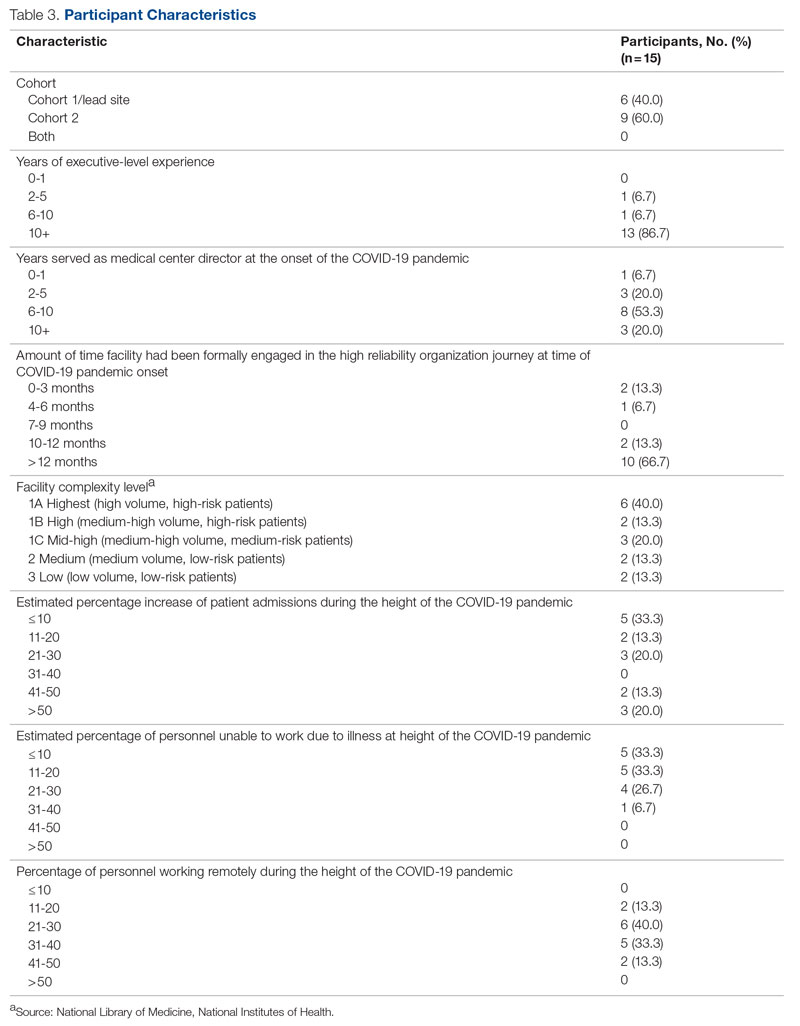

To minimize bias and maintain neutrality at the organizational level, only non-VHA individuals working on the project were directly involved with participants’ data review and analysis. Participant characteristics were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Responses to the 4 open-ended questions were coded and analyzed by an experienced researcher and coauthor using NVivo 11 qualitative data analysis software.28 To ensure trustworthiness (credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability) in the data analysis procedure,29 inductive thematic analysis was also performed manually using the methodologies of Braun and Clarke (Table 2)30 and Erlingsson and Brysiewicz.31 The goal of inductive analysis is to allow themes to emerge from the data while minimizing preconceptions.32,33 Regular team meetings were held to discuss and review the progress of data collection and analysis. The authors agreed that the themes were representative of the participants’ responses.

Institutional review board (IRB) review and approval were not required, as this project was a pilot QI initiative. The intent of the initiative was to explore ways to improve the quality of care delivered in the participants’ local care settings and not to generalize the findings. Under these circumstances, formal IRB review and approval of a QI initiative are not required.34 Participation in this pilot QI initiative was voluntary, and participants could withdraw at any time without consequences. Completion of the survey indicated consent. Confidentiality was ensured at all times by avoiding both the use of facility names and the collection of participant identifiers. Unique numbers were assigned to each participant. All comments provided by survey participants remained confidential and nonattributional for the purpose of publishing and presenting.

Results

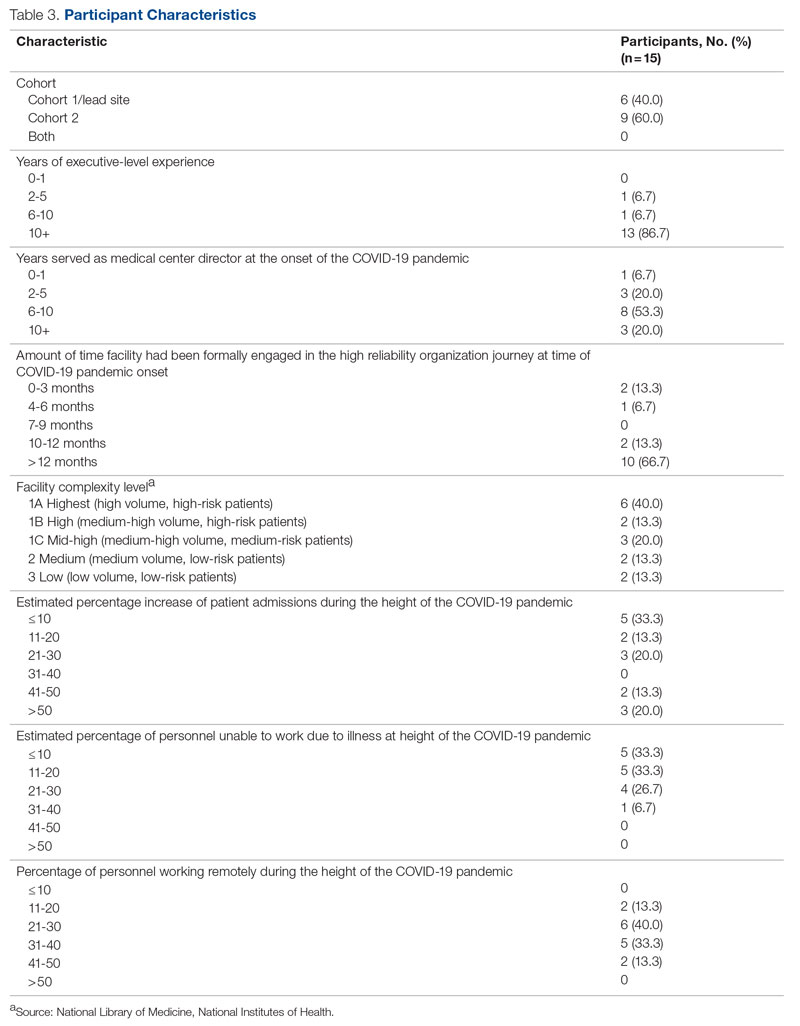

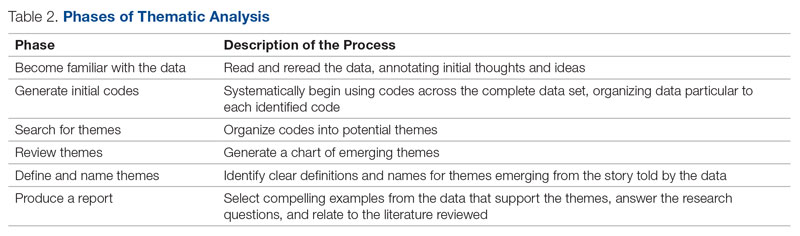

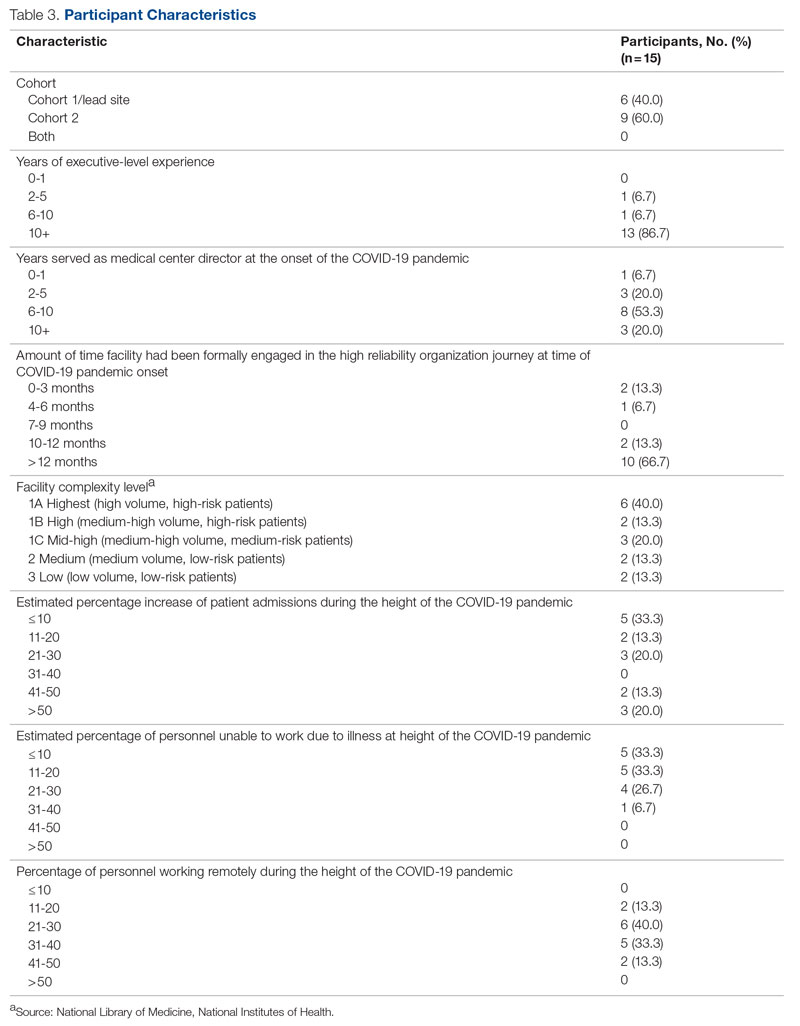

Of the 35 potential participants, 15 VHA MCDs (43%) completed the confidential web-based survey. Out of the 17 potential participants in Cohort 1, 6 (35%) completed the survey. With Cohort 2, 9 (50%) of the potential 18 participants responded. Although saturation was reached at 10 responses, the additional completed surveys were included in the analysis. Saturation can be achieved with a small number of participants (n = 9–17), particularly when the potential participants are relatively homogenous and project aims are narrowly defined.35 Most participants had more than 10 years of executive-level experience and most medical centers had been on the journey to high reliability for more than 12 months at the time of the pandemic (Table 3).

“There were too many competing priorities dealing with the pandemic and staffing crisis.” (Participant 8)

Other participants shared:

“We had our HRO mentor designated just as our first peak was descending on us. It was initially challenging to determine the proper pace of implementation when we clearly had other things going on. There was a real risk that people would say, ‘What, are you kidding?’ as we tried to roll this out.” (Participant 4)

“Prior to COVID, our main challenges were getting organized and operational rollout. During the pandemic, we had to shift our focus to COVID and the training aspects suffered. Also, many other priorities pulled us away from an HRO rollout focus.” (Participant 6)

“If you don’t need a highly reliable organization during a crisis, when do you need it? That was the message that we kicked off with. It was also VERY important to take things slowly. Education had to be done in bits, and we had a much more modest timeline than what would have been the norm for any initiative pre-COVID. The emphasis was on this being a long-term commitment, that we would be doing it the right way rather than rushing it, etc.” (Participant 4)

“Keeping HRO principles and a Just Culture on the forefront of our minds, we looked for opportunities to progress on our HRO journey, despite the challenges of the pandemic. Our monthly Town Halls became weekly events to share COVID updates and information with staff. We used the Town Halls to promote our HRO mission and to open communication lines with staff, designating 1 week each month as a ‘Safety Forum.’ The pandemic provided the springboard and backdrop for staff Safety Stories submissions, many of which were shared at our Town Halls and Safety Forums.” (Participant 7)

“We were able to utilize HRO principles in response to the COVID pandemic. Specifically standardized communication from the facility to VISN [Veterans Integrated Services Network] was initiated on a daily basis. This practice provided daily communication on key operational items and clinical items at the medical center, allowed timely feedback on actions being taken, as was instrumental in daily checks on staffing, COVID testing supplies, overall supply chain issues.” (Participant 9)

The recommendations provided by 10 participants (Cohort 1, n = 6; Cohort 2, n = 4) for other health care leaders experiencing a crisis during the journey to high reliability were insightful. The themes that frequently emerged from the responses to the survey were to adapt and overcome. Participants shared:

“Utilize the many tools you’re given, specifically your team. Try even the craziest ideas from frontline staff.” (Participant 1)

“Use your mentors for younger directors and, even if you think you know the answer, involve your staff. It makes them feel they have a voice and gives them ownership of the issues.” (Participant 5)

“Make sure that you have key leaders in place who are committed to HRO and can help the organization adjust.” (Participant 6)

“Take advantage of HRO Leader Coaching, which pairs MCDs with coaches who act as consultants for HRO leadership practices to ensure progress in reaching the next level in the journey to High Reliability.” (Participant 7)

“Meet regularly with the HRO Lead and team (more frequently during early stages of implementation) to provide support, eliminate barriers, and champion the HRO mission. It is important to include other members of the ELT [Executive Leadership Team] to ensure their involvement with the facility HRO strategic plan.” (Participant 7)

“Prioritize and understand that not everything is priority #1. Continue what you can with HRO, incorporate high reliability principles into the work being done during a crisis, but understand you may need to modify rollout schedules.” (Participant 8)

The theme of prioritizing competing demands emerged again from 5 participants (Cohort 1, n = 3; Cohort 2, n = 2) with question 3 describing recommendations for other leaders:

“Your first priority is to the crisis. Don’t get distracted by this or any other initiative. That was not a very popular message for the people pushing HRO, but it is the reality and the necessity. However, it IS possible to move forward with HRO (or other important initiatives) during crisis times, as long as you carefully consider what you are asking of people and don’t overload/overwhelm them. It is not your ego (or that of Central Office) that needs to be stoked. If the initiative truly has value, you need to be patient to see it done properly, rather than rushed/pushed/forced. Don’t kill it by being overeager and overwhelming your already overtaxed people. That said, keep moving forward. The key is pacing—and remember that your Type A hard-driving leader types (you know who you are) will certainly fail if they push it. Or even if they go at a normal pace that would be appropriate for noncrisis times.” (Participant 4)

“Prioritize and understand that not everything is priority #1. Continue what you can with HRO, incorporate high reliability principles into the work being done during a crisis, but understand you may need to modify rollout schedules.” (Participant 8)

“It was critical for us to always focus on the immediate workplace safety of staff (especially those on the frontlines of the pandemic response) when in the process of rolling out HRO initiatives.” (Participant 14)

Maintaining Momentum

“It seemed as though communication and education from VHA on HRO slowed down at the same time, which further slowed our progress. We are now trying to ramp our engagement up again.” (Participant 3)

“There can be synergy between crisis response and HRO implementation. As an example, one of the first steps we took was leadership rounding. That was necessary anyways for crisis management (raising the spirits on the front lines, so to speak). What we did was include scheduled time instead of (in addition to) ad hoc. And we got credit for taking an HRO step. I resisted whiteboards/visual management systems for a long time because (in my opinion) that would have been much too distracting during the crisis. Having waited for better times, I was able to move forward with that several months later and with good success.” (Participant 4)

Discussion

Health care leaders worldwide experienced an immense set of challenges because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is a crisis of a magnitude with no parallel in modern times. Strong, adaptive leadership at all levels of health care systems was needed to effectively address the immense crisis at hand.36,37 Findings from this pilot QI initiative suggest that MCDs faced many new challenges, requiring them to perform unfamiliar tasks and manage numerous overlapping challenges (eg, staffing shortages and reassignments, safety concerns, changes to patient appointments, backlogs in essential services), all while also trying to continue with the journey to high reliability. Despite the challenges leaders faced, they recognized the need to manage competing priorities early and effectively. At times, the priority was to address the wide-ranging, urgent issues related to the pandemic. When the conditions improved, there was time to refocus efforts on important but longer-term activities related to the HRO journey. Other participants recognized that their commitment to HRO needed to remain a priority even during the periods of intense focus on COVID-19.

Some participants felt compelled to stay committed to the HRO journey despite numerous competing demands. They stayed committed to looking for opportunities to progress by implementing HRO principles and practices to achieve safety, quality, and efficiency goals. This dedication is noteworthy, especially in light of recently published research that demonstrates the vast number of patient safety issues that presented during the COVID-19 pandemic (eg, ineffective communication, poor teamwork, the absence of coordination)1 as well as perceptions that patient safety and quality of care had significantly declined as a result of the crisis.36,37

Participants also highlighted the need to be adaptive when responding to the complexity and unpredictability of the pandemic. Participants regularly sought ways to increase their knowledge, skills, and abilities by using the resources (eg, tools, experts) available to them. Research shows that in increasingly complex and ever-changing situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic, leaders must be adaptive with all levels of performance, especially when limited information is available.38,39

This is the first initiative of its kind to specifically explore the challenges experienced and lessons learned from health care leaders continuing along the journey to high reliability during the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings from this pilot QI initiative revealed that many participants recommended that leaders adapt and overcome challenges as much as possible when continuing with HRO during a crisis. These findings are echoed in the current literature suggesting that adaptive performance is a highly effective form of leadership during crises.38,40 Being able to effectively adapt during a crisis is essential for reducing further vulnerabilities across health care systems. In fact, this lesson is shared by many countries in response to the unprecedented global crisis.41A limitation of this pilot QI initiative is that the authors did not directly solicit responses from all VHA MCDs or from other health care executives (eg, Chief of Staff, Associate Director for Operations, Associate Director for Patient Care, and Nurse Executive). As such, our findings represent only a small segment of senior leadership perspectives from a large, integrated health care system. Individuals who did not respond to the survey may have had different experiences than those who did, and the authors excluded many MCDs who formally began their HRO journeys in 2022, well after the pandemic was underway. Similarly, the experiences of Veterans Affairs leaders may or may not be similar to that of other health care organizations. Although the goal of this initiative was to explore the participants’ experiences during the period of crisis, time and distance from the events at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic may have resulted in difficulty recalling information as well as making sense of the occurrence. This potential recall bias is a common occurrence in trying to explore past experiences, especially as they relate to crises. Finally, this pilot QI initiative did not explore personal challenges participants may have faced during this period of time (eg, burnout, personal or family illness), which may have also shaped their responses.

Conclusion

This initiative suggests that VHA MCDs often relied on HRO principles to guide and assist with their response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including managing periods of unprecedented crisis. The ability to adapt and prioritize was seen as an especially important lesson. Many MCDs continued their personal and organizational efforts toward high reliability even in periods of intense challenge because of the pandemic. These findings can help with future crises that may occur during an organization’s journey to high reliability. This pilot QI initiative’s findings warrant further investigation to explore the experiences of the broader range of health care leaders while responding to unplanned crises or even planned large-scale cultural change or technology modernization initiatives (eg, electronic health record modernization) to expand the state of the science of high reliability as well as inform policy and decision-making. Finally, another area for future study is examining how leadership responses vary across facilities, depending on factors such as leader roles, facility complexity level, resource availability, patient population characteristics, and organizational culture.

Acknowledgment: The authors express their sincere gratitude to the medical center directors who participated in this pilot study.

Corresponding author: John S. Murray, PhD, MPH, MSGH, RN, FAAN, 20 Chapel St., Unit A502, Brookline, MA 02446; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Editors: Dying in a leadership vacuum. 9.4N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1479-1480. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2029812

2. Geerts JM, Kinnair D, Taheri P, et al. Guidance for health care leaders during the recovery stage of the COVID-19 pandemic: a consensus statement. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):1-16. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.20295

3. Boiral O, Brotherton M-C, Rivaud L, et al. Organizations’ management of the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review of business articles. Sustainability. 2021;13:1-20. doi:10.3390/su13073993

4. Razu SR, Yasmin T, Arif TB, et al. Challenges faced by healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative inquiry from Bangladesh. Front Public Health. 2021;9:1-13. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.647315

5. Lyng HB, Ree E, Wibe T, et al. Healthcare leaders’ use of innovative solutions to ensure resilience in healthcare during the Covid-19 pandemic: a qualitative study in Norwegian nursing homes and home care services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1-11. doi:1186/s12913-021-06923-1

6. Freitas J. Queiroz A, Bortotti I, et al. Nurse leaders’ challenges fighting the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Open J Nurs. 2021;11:267-280. doi:10.4236/ojn.2021.115024

7. McGuire AL, Aulisio MP, Davis FD, et al. Ethical challenges arising in the COVID-19 pandemic: an overview from the Association of Bioethics Program Directors (ABPD) Task Force. 9.4Am J Bioeth. 2020;20(7):15-27. doi:10.1080/15265161.2020.1764138

8. Turbow RM, Scibilia JP. Embracing principles of high reliability organizations can improve patient safety during pandemic. AAP News. January 19, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/8975

9. Roberts BH, Damiano LA, Graham S, et al. A case study in fostering a learning culture in the context of Covid-19. American Association for Physician Leadership. June 24, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://www.physicianleaders.org/news/a-case-study-in-fostering-a-learning-culture-in-the-context-of-covid-19

10. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Department of Veterans AffairsCOVID-19 National Summary. Veterans Affairs. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.accesstocare.va.gov/Healthcare/COVID19NationalSummary

11. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA fourth mission summary. Veterans Affairs. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.va.gov/health/coronavirus/statesupport.asp#:~:text=As%20part%20of%20the%20Fourth,the%20facilities%20we%20are%20supporting

12. Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D, et al. Implementing high-reliability organization principles into practice: a rapid evidence review. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(1):e320-e328. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000768

13. Murray JS, Kelly S, Hanover C. Promoting psychological safety in healthcare organizations. 9.4Mil Med. 2022;187(7-8):808-810. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac041

14. Maison D, Jaworska D, Adamczyk D, et al. The challenges arising from the COVID-19 pandemic and the way people deal with them: a qualitative longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):1-17. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258133

15. Schulman PR. Reliability, uncertainty and the management of error: new perspectives in the COVID-19 era. J Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2022;30:92-101. doi:10.1111/1468-5973.12356

16. Adelman JS, Gandhi TK. COVID-19 and patient safety: time to tap into our investment in high reliability. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(4): 331-333. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000843

17. Shingler-Nace A. COVID-19: when leadership calls. Nurs Lead. 2020;18(3):202-203. doi:10.1016/j.mnl.2020.03.017

18. Van Stralen D, Mercer TA. During pandemic COVID 19, the high reliability organization (HRO) identifies maladaptive stress behaviors: the stress-fear-threat cascade. Neonatol Tod. 2020;15(11):113-124. doi: 10.51362/neonatology.today/2020111511113124

19. Vogus TJ, Wilson AD, Randall K, et al. We’re all in this together: how COVID-19 revealed the coconstruction of mindful organising and organisational reliability. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31(3):230-233. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2021-014068

20. Van Stralen D. Pragmatic high-reliability organization (HRO) during pandemic COVID-19. Neonatol Tod. 2020(4);15:109-117. doi:10.51362/neonatology.today/20208158109117

21. Thull-Freedman J, Mondoux S, Stang A, et al. Going to the COVID-19 Gemba: using observation and high reliability strategies to achieve safety in a time of crisis. CJEM. 2020;22(6):738-741. doi:10.1017/cem.2020.380

22. Sarihasan I, Dajnoki K, Oláh J, et al. The importance of the leadership functions of a high-reliability health care organization in managing the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Econ Sociol. 2022;15:78-93. doi:10.14254/2071-789x.2022/15-1/5

23. Crain MA, Bush AL, Hayanga H, et al. Healthcare leadership in the COVID-19 pandemic: from innovative preparation to evolutionary transformation. J Health Leadersh. 2021;13:199-207. doi:10.2147/JHL.S319829

24. SQUIRE. Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) SQUIRE; 2020. Accessed March 1, 2023. http://www.squire-statement.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.ViewPage&pageId=471

25. Lounsbury O. How to write a quality improvement project. Patient Safety J. 2022;4(1):65-67. doi:10.33940/culture/2022.3.6

26. Bengtsson M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nurs Plus Open. 2016;2:8-14. doi:10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

27. Allen M. The Sage Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. (Vols. 1-4). SAGE Publications, Inc; 2017

28. Unlock insights with qualitative data analysis software. Lumivero. Accessed March 2, 2023. https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/

29. Maher C, Hadfield M, Hutchings M, et al. Ensuring rigor in qualitative data analysis: a design research approach to coding combining NVivo with traditional material methods. Int J Qual Methods. 2018;17:1-13. doi:10.1177/1609406918786362

30. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

31. Erlingsson C, Brysiewicz P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr J Emerg Med. 2017;7:93-99. doi:10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001

32. Vears DF, Gillam L. Inductive content analysis: a guide for beginning qualitative researchers. FoHPE. 2022;23:111-127. doi:10.11157/fohpe.v23i1.544

33. Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, et al. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16:1-13. doi:10.1177/1609406917733847

34. Gautham KS, Pearlman S. Do quality improvement projects require IRB approval? J Perinatol. 2021;41:1209-1212. doi:10.1038/s41372-021-01038-1

35. Hennink M, Kaiser BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:1-10. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

36. Balogun M, Dada FO, Oladimeji A, et al. Leading in a time of crisis: a qualitative study capturing experiences of health facility leaders during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria’s epicentre. Leadersh Health Serv (Bradf Engl). Published online May 12, 2022. doi:10.1108/lhs-02-2022-0017

37. Guttormson J, Calkins K, McAndrew N, et al. Critical care nurses’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: a US national survey. Am J Crit Care. 2022;31:96-103. doi:10.4037/ajcc2022312

38. Bajaba A, Bajaba S, Algarni M, et al. Adaptive managers as emerging leaders during the COVID-19 crisis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:1-11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661628

39. Ahern S, Loh E. Leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic: building and sustaining trust in times of uncertainty. BMJ Lead. 2021;59(4):266-269. doi.org/10.1136/leader-2020-000271

40. Cote R. Adaptive leadership approach with COVID 19 adaptive challenges. J Leadersh Account Ethics. 2022;19:34-44. doi:10.33423/jlae.v19i1.4992

41. Juvet TM, Corbaz-Kurth S, Roos P, et al. Adapting to the unexpected: problematic work situations and resilience strategies in healthcare institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic’s first wave. Saf Sci. 2021;139:1-9. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105277

From the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (all authors), and Cognosante, LLC, Falls Church, VA (Dr. Murray, Dr. Sawyer, and Jessica Fankhauser).

Abstract

Objective: The COVID-19 pandemic posed unprecedented leadership challenges to health care organizations worldwide, especially those on the journey to high reliability. The objective of this pilot quality improvement initiative was to describe the experiences of medical center leaders continuing along the journey to high reliability during the pandemic.

Methods: A convenience sample of Veterans Health Administration medical center directors at facilities that had initiated the journey to high reliability prior to or during the COVID-19 pandemic were asked to complete a confidential survey to explore the challenges experienced and lessons learned.

Results: Of the 35 potential participants, 15 completed the confidential web-based survey. Five major themes emerged from participants’ responses: (1) managing competing priorities, (2) staying committed, (3) adapting and overcoming, (4) prioritizing competing demands, and (5) maintaining momentum.

Conclusion: This pilot quality improvement initiative provides some insight into the challenges experienced and lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic to help inform health care leaders’ responses during crises they may encounter along the journey to becoming a high reliability organization.

Keywords: HRO, leadership, patient safety.

Health care leaders worldwide agree that the

Maintaining continuous progress toward advancing high reliability organization (HRO) principles and practices can be especially challenging during crises of unprecedented scale such as the pandemic. HROs must be continually focused on achieving safety, quality, and efficiency goals by attending to the 3 pillars of HRO: culture, leadership, and continuous process improvement. HROs promote a culture where all staff across the organization watch for and report any unsafe conditions before these conditions pose a greater risk in the workplace. Hospital leaders, from executives to frontline managers, must be cognizant of all systems and processes that have the potential to affect patient care.12 All of the principles of HROs must continue without fail to ensure patient safety; these principles include preoccupation with failure, anticipating unexpected risks, sensitivity to dynamic and ever-changing operations, avoiding oversimplifications of identified problems, fostering resilience across the organization, and deferring to those with the expertise to make the best decisions regardless of position, rank, or title.12,13 Given the demands faced by leaders during crises with unprecedented disruption to normal operating procedures, it can be especially difficult to identify systemic challenges and apply lessons learned in a timely manner. However, it is critical to identify such lessons in order to continuously improve and to increase preparedness for subsequent crises.13,14

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic’s unprecedented nature in recent history, a review of the literature produced little evidence exploring the challenges experienced and lessons learned by health care leaders, especially as it relates to implementing or sustaining HRO journeys during the COVID-19 pandemic. Related literature published to date consists of editorials on reliability, uncertainty, and the management of errors15; patient safety and high reliability preventive strategies16; and authentic leadership.17 Five viewpoints were published on HROs and maladaptive stress behaviors,18 mindful organizing and organizational reliability,19 the practical essence of HROs,20 embracing principles of HROs in crisis,8 and using observation and high reliability strategies when facing an unprecedented safety threat.21 Finally, the authors identified 2 studies that used a qualitative research approach to explore leadership functions within an HRO when managing crises22 and organizational change in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.23 Due to the paucity of available information, the authors undertook a pilot quality improvement (QI) initiative to address this knowledge gap.

The aim of this initiative was to gain a better understanding of the challenges experienced, lessons learned, and recommendations to be shared by VHA medical center directors (MCDs) of health care facilities that had initiated the journey to high reliability before or during the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors hope that this information will help health care leaders across both governmental and nongovernmental organizations, nationally and globally, to prepare for future pandemics, other unanticipated crises (eg, natural disasters, terrorist attacks), and major change initiatives (eg, electronic health record modernization) that may affect the delivery of safe, high-quality, and effective patient care. The initiative is described using the SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines.24,25

Methods

Survey

We used a qualitative approach and administered a confidential web-based survey, developed by the project team, to VHA MCDs at facilities that had initiated the journey to high reliability before or during the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey consisted of 8 participant characteristic questions (Table 1) and 4 open-ended questions. The open-ended questions were designed to encourage MCD participants to freely provide detailed descriptions of the challenges experienced, lessons learned, recommendations for other health care leaders, and any additional information they believed was relevant.26,27 Participants were asked to respond to the following items:

- Please describe any challenges you experienced while in the role of MCD at a facility that initiated implementation of HRO principles and practices prior to (February 2020) or during (March 2020–September 2021) the initial onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- What are some lessons that you learned when responding to the COVID-19 pandemic while on the journey to high reliability?

- What recommendations would you like to make to other health care leaders to enable them to respond effectively to crises while on the journey to high reliability?

- Please provide any additional information that would be of value.

An invitation to participate in this pilot QI initiative was sent via e-mail to 35 potential participants, who were all MCDs at Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 facilities. The invitation was sent on June 17, 2022, by a VHA senior High Reliability Enterprise Support government team member not directly involved with the initiative.

The invitation included the objective of the initiative, estimated time to complete the confidential web-based survey, time allotted for responses to be submitted, and a link to the survey should potential participants agree to participate. Potential participants were informed that their involvement was voluntary, based on their willingness to participate and available time to complete the survey. Finally, the invitation noted that any comments provided would remain confidential and nonattributional for the purpose of publishing and presenting. The inclusion criteria for participation were: (1) serving

Data Gathering and Analysis

To minimize bias and maintain neutrality at the organizational level, only non-VHA individuals working on the project were directly involved with participants’ data review and analysis. Participant characteristics were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Responses to the 4 open-ended questions were coded and analyzed by an experienced researcher and coauthor using NVivo 11 qualitative data analysis software.28 To ensure trustworthiness (credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability) in the data analysis procedure,29 inductive thematic analysis was also performed manually using the methodologies of Braun and Clarke (Table 2)30 and Erlingsson and Brysiewicz.31 The goal of inductive analysis is to allow themes to emerge from the data while minimizing preconceptions.32,33 Regular team meetings were held to discuss and review the progress of data collection and analysis. The authors agreed that the themes were representative of the participants’ responses.

Institutional review board (IRB) review and approval were not required, as this project was a pilot QI initiative. The intent of the initiative was to explore ways to improve the quality of care delivered in the participants’ local care settings and not to generalize the findings. Under these circumstances, formal IRB review and approval of a QI initiative are not required.34 Participation in this pilot QI initiative was voluntary, and participants could withdraw at any time without consequences. Completion of the survey indicated consent. Confidentiality was ensured at all times by avoiding both the use of facility names and the collection of participant identifiers. Unique numbers were assigned to each participant. All comments provided by survey participants remained confidential and nonattributional for the purpose of publishing and presenting.

Results

Of the 35 potential participants, 15 VHA MCDs (43%) completed the confidential web-based survey. Out of the 17 potential participants in Cohort 1, 6 (35%) completed the survey. With Cohort 2, 9 (50%) of the potential 18 participants responded. Although saturation was reached at 10 responses, the additional completed surveys were included in the analysis. Saturation can be achieved with a small number of participants (n = 9–17), particularly when the potential participants are relatively homogenous and project aims are narrowly defined.35 Most participants had more than 10 years of executive-level experience and most medical centers had been on the journey to high reliability for more than 12 months at the time of the pandemic (Table 3).

“There were too many competing priorities dealing with the pandemic and staffing crisis.” (Participant 8)

Other participants shared:

“We had our HRO mentor designated just as our first peak was descending on us. It was initially challenging to determine the proper pace of implementation when we clearly had other things going on. There was a real risk that people would say, ‘What, are you kidding?’ as we tried to roll this out.” (Participant 4)

“Prior to COVID, our main challenges were getting organized and operational rollout. During the pandemic, we had to shift our focus to COVID and the training aspects suffered. Also, many other priorities pulled us away from an HRO rollout focus.” (Participant 6)

“If you don’t need a highly reliable organization during a crisis, when do you need it? That was the message that we kicked off with. It was also VERY important to take things slowly. Education had to be done in bits, and we had a much more modest timeline than what would have been the norm for any initiative pre-COVID. The emphasis was on this being a long-term commitment, that we would be doing it the right way rather than rushing it, etc.” (Participant 4)

“Keeping HRO principles and a Just Culture on the forefront of our minds, we looked for opportunities to progress on our HRO journey, despite the challenges of the pandemic. Our monthly Town Halls became weekly events to share COVID updates and information with staff. We used the Town Halls to promote our HRO mission and to open communication lines with staff, designating 1 week each month as a ‘Safety Forum.’ The pandemic provided the springboard and backdrop for staff Safety Stories submissions, many of which were shared at our Town Halls and Safety Forums.” (Participant 7)

“We were able to utilize HRO principles in response to the COVID pandemic. Specifically standardized communication from the facility to VISN [Veterans Integrated Services Network] was initiated on a daily basis. This practice provided daily communication on key operational items and clinical items at the medical center, allowed timely feedback on actions being taken, as was instrumental in daily checks on staffing, COVID testing supplies, overall supply chain issues.” (Participant 9)

The recommendations provided by 10 participants (Cohort 1, n = 6; Cohort 2, n = 4) for other health care leaders experiencing a crisis during the journey to high reliability were insightful. The themes that frequently emerged from the responses to the survey were to adapt and overcome. Participants shared:

“Utilize the many tools you’re given, specifically your team. Try even the craziest ideas from frontline staff.” (Participant 1)

“Use your mentors for younger directors and, even if you think you know the answer, involve your staff. It makes them feel they have a voice and gives them ownership of the issues.” (Participant 5)

“Make sure that you have key leaders in place who are committed to HRO and can help the organization adjust.” (Participant 6)

“Take advantage of HRO Leader Coaching, which pairs MCDs with coaches who act as consultants for HRO leadership practices to ensure progress in reaching the next level in the journey to High Reliability.” (Participant 7)

“Meet regularly with the HRO Lead and team (more frequently during early stages of implementation) to provide support, eliminate barriers, and champion the HRO mission. It is important to include other members of the ELT [Executive Leadership Team] to ensure their involvement with the facility HRO strategic plan.” (Participant 7)

“Prioritize and understand that not everything is priority #1. Continue what you can with HRO, incorporate high reliability principles into the work being done during a crisis, but understand you may need to modify rollout schedules.” (Participant 8)

The theme of prioritizing competing demands emerged again from 5 participants (Cohort 1, n = 3; Cohort 2, n = 2) with question 3 describing recommendations for other leaders:

“Your first priority is to the crisis. Don’t get distracted by this or any other initiative. That was not a very popular message for the people pushing HRO, but it is the reality and the necessity. However, it IS possible to move forward with HRO (or other important initiatives) during crisis times, as long as you carefully consider what you are asking of people and don’t overload/overwhelm them. It is not your ego (or that of Central Office) that needs to be stoked. If the initiative truly has value, you need to be patient to see it done properly, rather than rushed/pushed/forced. Don’t kill it by being overeager and overwhelming your already overtaxed people. That said, keep moving forward. The key is pacing—and remember that your Type A hard-driving leader types (you know who you are) will certainly fail if they push it. Or even if they go at a normal pace that would be appropriate for noncrisis times.” (Participant 4)

“Prioritize and understand that not everything is priority #1. Continue what you can with HRO, incorporate high reliability principles into the work being done during a crisis, but understand you may need to modify rollout schedules.” (Participant 8)

“It was critical for us to always focus on the immediate workplace safety of staff (especially those on the frontlines of the pandemic response) when in the process of rolling out HRO initiatives.” (Participant 14)

Maintaining Momentum

“It seemed as though communication and education from VHA on HRO slowed down at the same time, which further slowed our progress. We are now trying to ramp our engagement up again.” (Participant 3)

“There can be synergy between crisis response and HRO implementation. As an example, one of the first steps we took was leadership rounding. That was necessary anyways for crisis management (raising the spirits on the front lines, so to speak). What we did was include scheduled time instead of (in addition to) ad hoc. And we got credit for taking an HRO step. I resisted whiteboards/visual management systems for a long time because (in my opinion) that would have been much too distracting during the crisis. Having waited for better times, I was able to move forward with that several months later and with good success.” (Participant 4)

Discussion

Health care leaders worldwide experienced an immense set of challenges because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is a crisis of a magnitude with no parallel in modern times. Strong, adaptive leadership at all levels of health care systems was needed to effectively address the immense crisis at hand.36,37 Findings from this pilot QI initiative suggest that MCDs faced many new challenges, requiring them to perform unfamiliar tasks and manage numerous overlapping challenges (eg, staffing shortages and reassignments, safety concerns, changes to patient appointments, backlogs in essential services), all while also trying to continue with the journey to high reliability. Despite the challenges leaders faced, they recognized the need to manage competing priorities early and effectively. At times, the priority was to address the wide-ranging, urgent issues related to the pandemic. When the conditions improved, there was time to refocus efforts on important but longer-term activities related to the HRO journey. Other participants recognized that their commitment to HRO needed to remain a priority even during the periods of intense focus on COVID-19.

Some participants felt compelled to stay committed to the HRO journey despite numerous competing demands. They stayed committed to looking for opportunities to progress by implementing HRO principles and practices to achieve safety, quality, and efficiency goals. This dedication is noteworthy, especially in light of recently published research that demonstrates the vast number of patient safety issues that presented during the COVID-19 pandemic (eg, ineffective communication, poor teamwork, the absence of coordination)1 as well as perceptions that patient safety and quality of care had significantly declined as a result of the crisis.36,37

Participants also highlighted the need to be adaptive when responding to the complexity and unpredictability of the pandemic. Participants regularly sought ways to increase their knowledge, skills, and abilities by using the resources (eg, tools, experts) available to them. Research shows that in increasingly complex and ever-changing situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic, leaders must be adaptive with all levels of performance, especially when limited information is available.38,39

This is the first initiative of its kind to specifically explore the challenges experienced and lessons learned from health care leaders continuing along the journey to high reliability during the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings from this pilot QI initiative revealed that many participants recommended that leaders adapt and overcome challenges as much as possible when continuing with HRO during a crisis. These findings are echoed in the current literature suggesting that adaptive performance is a highly effective form of leadership during crises.38,40 Being able to effectively adapt during a crisis is essential for reducing further vulnerabilities across health care systems. In fact, this lesson is shared by many countries in response to the unprecedented global crisis.41A limitation of this pilot QI initiative is that the authors did not directly solicit responses from all VHA MCDs or from other health care executives (eg, Chief of Staff, Associate Director for Operations, Associate Director for Patient Care, and Nurse Executive). As such, our findings represent only a small segment of senior leadership perspectives from a large, integrated health care system. Individuals who did not respond to the survey may have had different experiences than those who did, and the authors excluded many MCDs who formally began their HRO journeys in 2022, well after the pandemic was underway. Similarly, the experiences of Veterans Affairs leaders may or may not be similar to that of other health care organizations. Although the goal of this initiative was to explore the participants’ experiences during the period of crisis, time and distance from the events at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic may have resulted in difficulty recalling information as well as making sense of the occurrence. This potential recall bias is a common occurrence in trying to explore past experiences, especially as they relate to crises. Finally, this pilot QI initiative did not explore personal challenges participants may have faced during this period of time (eg, burnout, personal or family illness), which may have also shaped their responses.

Conclusion

This initiative suggests that VHA MCDs often relied on HRO principles to guide and assist with their response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including managing periods of unprecedented crisis. The ability to adapt and prioritize was seen as an especially important lesson. Many MCDs continued their personal and organizational efforts toward high reliability even in periods of intense challenge because of the pandemic. These findings can help with future crises that may occur during an organization’s journey to high reliability. This pilot QI initiative’s findings warrant further investigation to explore the experiences of the broader range of health care leaders while responding to unplanned crises or even planned large-scale cultural change or technology modernization initiatives (eg, electronic health record modernization) to expand the state of the science of high reliability as well as inform policy and decision-making. Finally, another area for future study is examining how leadership responses vary across facilities, depending on factors such as leader roles, facility complexity level, resource availability, patient population characteristics, and organizational culture.

Acknowledgment: The authors express their sincere gratitude to the medical center directors who participated in this pilot study.

Corresponding author: John S. Murray, PhD, MPH, MSGH, RN, FAAN, 20 Chapel St., Unit A502, Brookline, MA 02446; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

From the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (all authors), and Cognosante, LLC, Falls Church, VA (Dr. Murray, Dr. Sawyer, and Jessica Fankhauser).

Abstract

Objective: The COVID-19 pandemic posed unprecedented leadership challenges to health care organizations worldwide, especially those on the journey to high reliability. The objective of this pilot quality improvement initiative was to describe the experiences of medical center leaders continuing along the journey to high reliability during the pandemic.

Methods: A convenience sample of Veterans Health Administration medical center directors at facilities that had initiated the journey to high reliability prior to or during the COVID-19 pandemic were asked to complete a confidential survey to explore the challenges experienced and lessons learned.

Results: Of the 35 potential participants, 15 completed the confidential web-based survey. Five major themes emerged from participants’ responses: (1) managing competing priorities, (2) staying committed, (3) adapting and overcoming, (4) prioritizing competing demands, and (5) maintaining momentum.

Conclusion: This pilot quality improvement initiative provides some insight into the challenges experienced and lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic to help inform health care leaders’ responses during crises they may encounter along the journey to becoming a high reliability organization.

Keywords: HRO, leadership, patient safety.

Health care leaders worldwide agree that the

Maintaining continuous progress toward advancing high reliability organization (HRO) principles and practices can be especially challenging during crises of unprecedented scale such as the pandemic. HROs must be continually focused on achieving safety, quality, and efficiency goals by attending to the 3 pillars of HRO: culture, leadership, and continuous process improvement. HROs promote a culture where all staff across the organization watch for and report any unsafe conditions before these conditions pose a greater risk in the workplace. Hospital leaders, from executives to frontline managers, must be cognizant of all systems and processes that have the potential to affect patient care.12 All of the principles of HROs must continue without fail to ensure patient safety; these principles include preoccupation with failure, anticipating unexpected risks, sensitivity to dynamic and ever-changing operations, avoiding oversimplifications of identified problems, fostering resilience across the organization, and deferring to those with the expertise to make the best decisions regardless of position, rank, or title.12,13 Given the demands faced by leaders during crises with unprecedented disruption to normal operating procedures, it can be especially difficult to identify systemic challenges and apply lessons learned in a timely manner. However, it is critical to identify such lessons in order to continuously improve and to increase preparedness for subsequent crises.13,14

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic’s unprecedented nature in recent history, a review of the literature produced little evidence exploring the challenges experienced and lessons learned by health care leaders, especially as it relates to implementing or sustaining HRO journeys during the COVID-19 pandemic. Related literature published to date consists of editorials on reliability, uncertainty, and the management of errors15; patient safety and high reliability preventive strategies16; and authentic leadership.17 Five viewpoints were published on HROs and maladaptive stress behaviors,18 mindful organizing and organizational reliability,19 the practical essence of HROs,20 embracing principles of HROs in crisis,8 and using observation and high reliability strategies when facing an unprecedented safety threat.21 Finally, the authors identified 2 studies that used a qualitative research approach to explore leadership functions within an HRO when managing crises22 and organizational change in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.23 Due to the paucity of available information, the authors undertook a pilot quality improvement (QI) initiative to address this knowledge gap.

The aim of this initiative was to gain a better understanding of the challenges experienced, lessons learned, and recommendations to be shared by VHA medical center directors (MCDs) of health care facilities that had initiated the journey to high reliability before or during the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors hope that this information will help health care leaders across both governmental and nongovernmental organizations, nationally and globally, to prepare for future pandemics, other unanticipated crises (eg, natural disasters, terrorist attacks), and major change initiatives (eg, electronic health record modernization) that may affect the delivery of safe, high-quality, and effective patient care. The initiative is described using the SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines.24,25

Methods

Survey

We used a qualitative approach and administered a confidential web-based survey, developed by the project team, to VHA MCDs at facilities that had initiated the journey to high reliability before or during the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey consisted of 8 participant characteristic questions (Table 1) and 4 open-ended questions. The open-ended questions were designed to encourage MCD participants to freely provide detailed descriptions of the challenges experienced, lessons learned, recommendations for other health care leaders, and any additional information they believed was relevant.26,27 Participants were asked to respond to the following items:

- Please describe any challenges you experienced while in the role of MCD at a facility that initiated implementation of HRO principles and practices prior to (February 2020) or during (March 2020–September 2021) the initial onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- What are some lessons that you learned when responding to the COVID-19 pandemic while on the journey to high reliability?

- What recommendations would you like to make to other health care leaders to enable them to respond effectively to crises while on the journey to high reliability?

- Please provide any additional information that would be of value.

An invitation to participate in this pilot QI initiative was sent via e-mail to 35 potential participants, who were all MCDs at Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 facilities. The invitation was sent on June 17, 2022, by a VHA senior High Reliability Enterprise Support government team member not directly involved with the initiative.

The invitation included the objective of the initiative, estimated time to complete the confidential web-based survey, time allotted for responses to be submitted, and a link to the survey should potential participants agree to participate. Potential participants were informed that their involvement was voluntary, based on their willingness to participate and available time to complete the survey. Finally, the invitation noted that any comments provided would remain confidential and nonattributional for the purpose of publishing and presenting. The inclusion criteria for participation were: (1) serving

Data Gathering and Analysis

To minimize bias and maintain neutrality at the organizational level, only non-VHA individuals working on the project were directly involved with participants’ data review and analysis. Participant characteristics were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Responses to the 4 open-ended questions were coded and analyzed by an experienced researcher and coauthor using NVivo 11 qualitative data analysis software.28 To ensure trustworthiness (credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability) in the data analysis procedure,29 inductive thematic analysis was also performed manually using the methodologies of Braun and Clarke (Table 2)30 and Erlingsson and Brysiewicz.31 The goal of inductive analysis is to allow themes to emerge from the data while minimizing preconceptions.32,33 Regular team meetings were held to discuss and review the progress of data collection and analysis. The authors agreed that the themes were representative of the participants’ responses.

Institutional review board (IRB) review and approval were not required, as this project was a pilot QI initiative. The intent of the initiative was to explore ways to improve the quality of care delivered in the participants’ local care settings and not to generalize the findings. Under these circumstances, formal IRB review and approval of a QI initiative are not required.34 Participation in this pilot QI initiative was voluntary, and participants could withdraw at any time without consequences. Completion of the survey indicated consent. Confidentiality was ensured at all times by avoiding both the use of facility names and the collection of participant identifiers. Unique numbers were assigned to each participant. All comments provided by survey participants remained confidential and nonattributional for the purpose of publishing and presenting.

Results

Of the 35 potential participants, 15 VHA MCDs (43%) completed the confidential web-based survey. Out of the 17 potential participants in Cohort 1, 6 (35%) completed the survey. With Cohort 2, 9 (50%) of the potential 18 participants responded. Although saturation was reached at 10 responses, the additional completed surveys were included in the analysis. Saturation can be achieved with a small number of participants (n = 9–17), particularly when the potential participants are relatively homogenous and project aims are narrowly defined.35 Most participants had more than 10 years of executive-level experience and most medical centers had been on the journey to high reliability for more than 12 months at the time of the pandemic (Table 3).

“There were too many competing priorities dealing with the pandemic and staffing crisis.” (Participant 8)

Other participants shared:

“We had our HRO mentor designated just as our first peak was descending on us. It was initially challenging to determine the proper pace of implementation when we clearly had other things going on. There was a real risk that people would say, ‘What, are you kidding?’ as we tried to roll this out.” (Participant 4)

“Prior to COVID, our main challenges were getting organized and operational rollout. During the pandemic, we had to shift our focus to COVID and the training aspects suffered. Also, many other priorities pulled us away from an HRO rollout focus.” (Participant 6)

“If you don’t need a highly reliable organization during a crisis, when do you need it? That was the message that we kicked off with. It was also VERY important to take things slowly. Education had to be done in bits, and we had a much more modest timeline than what would have been the norm for any initiative pre-COVID. The emphasis was on this being a long-term commitment, that we would be doing it the right way rather than rushing it, etc.” (Participant 4)

“Keeping HRO principles and a Just Culture on the forefront of our minds, we looked for opportunities to progress on our HRO journey, despite the challenges of the pandemic. Our monthly Town Halls became weekly events to share COVID updates and information with staff. We used the Town Halls to promote our HRO mission and to open communication lines with staff, designating 1 week each month as a ‘Safety Forum.’ The pandemic provided the springboard and backdrop for staff Safety Stories submissions, many of which were shared at our Town Halls and Safety Forums.” (Participant 7)

“We were able to utilize HRO principles in response to the COVID pandemic. Specifically standardized communication from the facility to VISN [Veterans Integrated Services Network] was initiated on a daily basis. This practice provided daily communication on key operational items and clinical items at the medical center, allowed timely feedback on actions being taken, as was instrumental in daily checks on staffing, COVID testing supplies, overall supply chain issues.” (Participant 9)

The recommendations provided by 10 participants (Cohort 1, n = 6; Cohort 2, n = 4) for other health care leaders experiencing a crisis during the journey to high reliability were insightful. The themes that frequently emerged from the responses to the survey were to adapt and overcome. Participants shared:

“Utilize the many tools you’re given, specifically your team. Try even the craziest ideas from frontline staff.” (Participant 1)

“Use your mentors for younger directors and, even if you think you know the answer, involve your staff. It makes them feel they have a voice and gives them ownership of the issues.” (Participant 5)

“Make sure that you have key leaders in place who are committed to HRO and can help the organization adjust.” (Participant 6)

“Take advantage of HRO Leader Coaching, which pairs MCDs with coaches who act as consultants for HRO leadership practices to ensure progress in reaching the next level in the journey to High Reliability.” (Participant 7)

“Meet regularly with the HRO Lead and team (more frequently during early stages of implementation) to provide support, eliminate barriers, and champion the HRO mission. It is important to include other members of the ELT [Executive Leadership Team] to ensure their involvement with the facility HRO strategic plan.” (Participant 7)

“Prioritize and understand that not everything is priority #1. Continue what you can with HRO, incorporate high reliability principles into the work being done during a crisis, but understand you may need to modify rollout schedules.” (Participant 8)

The theme of prioritizing competing demands emerged again from 5 participants (Cohort 1, n = 3; Cohort 2, n = 2) with question 3 describing recommendations for other leaders:

“Your first priority is to the crisis. Don’t get distracted by this or any other initiative. That was not a very popular message for the people pushing HRO, but it is the reality and the necessity. However, it IS possible to move forward with HRO (or other important initiatives) during crisis times, as long as you carefully consider what you are asking of people and don’t overload/overwhelm them. It is not your ego (or that of Central Office) that needs to be stoked. If the initiative truly has value, you need to be patient to see it done properly, rather than rushed/pushed/forced. Don’t kill it by being overeager and overwhelming your already overtaxed people. That said, keep moving forward. The key is pacing—and remember that your Type A hard-driving leader types (you know who you are) will certainly fail if they push it. Or even if they go at a normal pace that would be appropriate for noncrisis times.” (Participant 4)

“Prioritize and understand that not everything is priority #1. Continue what you can with HRO, incorporate high reliability principles into the work being done during a crisis, but understand you may need to modify rollout schedules.” (Participant 8)

“It was critical for us to always focus on the immediate workplace safety of staff (especially those on the frontlines of the pandemic response) when in the process of rolling out HRO initiatives.” (Participant 14)

Maintaining Momentum

“It seemed as though communication and education from VHA on HRO slowed down at the same time, which further slowed our progress. We are now trying to ramp our engagement up again.” (Participant 3)

“There can be synergy between crisis response and HRO implementation. As an example, one of the first steps we took was leadership rounding. That was necessary anyways for crisis management (raising the spirits on the front lines, so to speak). What we did was include scheduled time instead of (in addition to) ad hoc. And we got credit for taking an HRO step. I resisted whiteboards/visual management systems for a long time because (in my opinion) that would have been much too distracting during the crisis. Having waited for better times, I was able to move forward with that several months later and with good success.” (Participant 4)

Discussion

Health care leaders worldwide experienced an immense set of challenges because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is a crisis of a magnitude with no parallel in modern times. Strong, adaptive leadership at all levels of health care systems was needed to effectively address the immense crisis at hand.36,37 Findings from this pilot QI initiative suggest that MCDs faced many new challenges, requiring them to perform unfamiliar tasks and manage numerous overlapping challenges (eg, staffing shortages and reassignments, safety concerns, changes to patient appointments, backlogs in essential services), all while also trying to continue with the journey to high reliability. Despite the challenges leaders faced, they recognized the need to manage competing priorities early and effectively. At times, the priority was to address the wide-ranging, urgent issues related to the pandemic. When the conditions improved, there was time to refocus efforts on important but longer-term activities related to the HRO journey. Other participants recognized that their commitment to HRO needed to remain a priority even during the periods of intense focus on COVID-19.

Some participants felt compelled to stay committed to the HRO journey despite numerous competing demands. They stayed committed to looking for opportunities to progress by implementing HRO principles and practices to achieve safety, quality, and efficiency goals. This dedication is noteworthy, especially in light of recently published research that demonstrates the vast number of patient safety issues that presented during the COVID-19 pandemic (eg, ineffective communication, poor teamwork, the absence of coordination)1 as well as perceptions that patient safety and quality of care had significantly declined as a result of the crisis.36,37

Participants also highlighted the need to be adaptive when responding to the complexity and unpredictability of the pandemic. Participants regularly sought ways to increase their knowledge, skills, and abilities by using the resources (eg, tools, experts) available to them. Research shows that in increasingly complex and ever-changing situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic, leaders must be adaptive with all levels of performance, especially when limited information is available.38,39

This is the first initiative of its kind to specifically explore the challenges experienced and lessons learned from health care leaders continuing along the journey to high reliability during the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings from this pilot QI initiative revealed that many participants recommended that leaders adapt and overcome challenges as much as possible when continuing with HRO during a crisis. These findings are echoed in the current literature suggesting that adaptive performance is a highly effective form of leadership during crises.38,40 Being able to effectively adapt during a crisis is essential for reducing further vulnerabilities across health care systems. In fact, this lesson is shared by many countries in response to the unprecedented global crisis.41A limitation of this pilot QI initiative is that the authors did not directly solicit responses from all VHA MCDs or from other health care executives (eg, Chief of Staff, Associate Director for Operations, Associate Director for Patient Care, and Nurse Executive). As such, our findings represent only a small segment of senior leadership perspectives from a large, integrated health care system. Individuals who did not respond to the survey may have had different experiences than those who did, and the authors excluded many MCDs who formally began their HRO journeys in 2022, well after the pandemic was underway. Similarly, the experiences of Veterans Affairs leaders may or may not be similar to that of other health care organizations. Although the goal of this initiative was to explore the participants’ experiences during the period of crisis, time and distance from the events at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic may have resulted in difficulty recalling information as well as making sense of the occurrence. This potential recall bias is a common occurrence in trying to explore past experiences, especially as they relate to crises. Finally, this pilot QI initiative did not explore personal challenges participants may have faced during this period of time (eg, burnout, personal or family illness), which may have also shaped their responses.

Conclusion

This initiative suggests that VHA MCDs often relied on HRO principles to guide and assist with their response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including managing periods of unprecedented crisis. The ability to adapt and prioritize was seen as an especially important lesson. Many MCDs continued their personal and organizational efforts toward high reliability even in periods of intense challenge because of the pandemic. These findings can help with future crises that may occur during an organization’s journey to high reliability. This pilot QI initiative’s findings warrant further investigation to explore the experiences of the broader range of health care leaders while responding to unplanned crises or even planned large-scale cultural change or technology modernization initiatives (eg, electronic health record modernization) to expand the state of the science of high reliability as well as inform policy and decision-making. Finally, another area for future study is examining how leadership responses vary across facilities, depending on factors such as leader roles, facility complexity level, resource availability, patient population characteristics, and organizational culture.

Acknowledgment: The authors express their sincere gratitude to the medical center directors who participated in this pilot study.

Corresponding author: John S. Murray, PhD, MPH, MSGH, RN, FAAN, 20 Chapel St., Unit A502, Brookline, MA 02446; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Editors: Dying in a leadership vacuum. 9.4N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1479-1480. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2029812

2. Geerts JM, Kinnair D, Taheri P, et al. Guidance for health care leaders during the recovery stage of the COVID-19 pandemic: a consensus statement. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):1-16. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.20295

3. Boiral O, Brotherton M-C, Rivaud L, et al. Organizations’ management of the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review of business articles. Sustainability. 2021;13:1-20. doi:10.3390/su13073993

4. Razu SR, Yasmin T, Arif TB, et al. Challenges faced by healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative inquiry from Bangladesh. Front Public Health. 2021;9:1-13. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.647315

5. Lyng HB, Ree E, Wibe T, et al. Healthcare leaders’ use of innovative solutions to ensure resilience in healthcare during the Covid-19 pandemic: a qualitative study in Norwegian nursing homes and home care services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1-11. doi:1186/s12913-021-06923-1

6. Freitas J. Queiroz A, Bortotti I, et al. Nurse leaders’ challenges fighting the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Open J Nurs. 2021;11:267-280. doi:10.4236/ojn.2021.115024

7. McGuire AL, Aulisio MP, Davis FD, et al. Ethical challenges arising in the COVID-19 pandemic: an overview from the Association of Bioethics Program Directors (ABPD) Task Force. 9.4Am J Bioeth. 2020;20(7):15-27. doi:10.1080/15265161.2020.1764138

8. Turbow RM, Scibilia JP. Embracing principles of high reliability organizations can improve patient safety during pandemic. AAP News. January 19, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/8975

9. Roberts BH, Damiano LA, Graham S, et al. A case study in fostering a learning culture in the context of Covid-19. American Association for Physician Leadership. June 24, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://www.physicianleaders.org/news/a-case-study-in-fostering-a-learning-culture-in-the-context-of-covid-19

10. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Department of Veterans AffairsCOVID-19 National Summary. Veterans Affairs. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.accesstocare.va.gov/Healthcare/COVID19NationalSummary

11. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA fourth mission summary. Veterans Affairs. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.va.gov/health/coronavirus/statesupport.asp#:~:text=As%20part%20of%20the%20Fourth,the%20facilities%20we%20are%20supporting

12. Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D, et al. Implementing high-reliability organization principles into practice: a rapid evidence review. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(1):e320-e328. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000768

13. Murray JS, Kelly S, Hanover C. Promoting psychological safety in healthcare organizations. 9.4Mil Med. 2022;187(7-8):808-810. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac041

14. Maison D, Jaworska D, Adamczyk D, et al. The challenges arising from the COVID-19 pandemic and the way people deal with them: a qualitative longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):1-17. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258133

15. Schulman PR. Reliability, uncertainty and the management of error: new perspectives in the COVID-19 era. J Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2022;30:92-101. doi:10.1111/1468-5973.12356

16. Adelman JS, Gandhi TK. COVID-19 and patient safety: time to tap into our investment in high reliability. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(4): 331-333. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000843

17. Shingler-Nace A. COVID-19: when leadership calls. Nurs Lead. 2020;18(3):202-203. doi:10.1016/j.mnl.2020.03.017

18. Van Stralen D, Mercer TA. During pandemic COVID 19, the high reliability organization (HRO) identifies maladaptive stress behaviors: the stress-fear-threat cascade. Neonatol Tod. 2020;15(11):113-124. doi: 10.51362/neonatology.today/2020111511113124

19. Vogus TJ, Wilson AD, Randall K, et al. We’re all in this together: how COVID-19 revealed the coconstruction of mindful organising and organisational reliability. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31(3):230-233. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2021-014068

20. Van Stralen D. Pragmatic high-reliability organization (HRO) during pandemic COVID-19. Neonatol Tod. 2020(4);15:109-117. doi:10.51362/neonatology.today/20208158109117

21. Thull-Freedman J, Mondoux S, Stang A, et al. Going to the COVID-19 Gemba: using observation and high reliability strategies to achieve safety in a time of crisis. CJEM. 2020;22(6):738-741. doi:10.1017/cem.2020.380

22. Sarihasan I, Dajnoki K, Oláh J, et al. The importance of the leadership functions of a high-reliability health care organization in managing the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Econ Sociol. 2022;15:78-93. doi:10.14254/2071-789x.2022/15-1/5