User login

Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer

Prostate Cancer: Small Cell Prostate Carcinoma-Pathology

Abdominal pain and urinary frequency

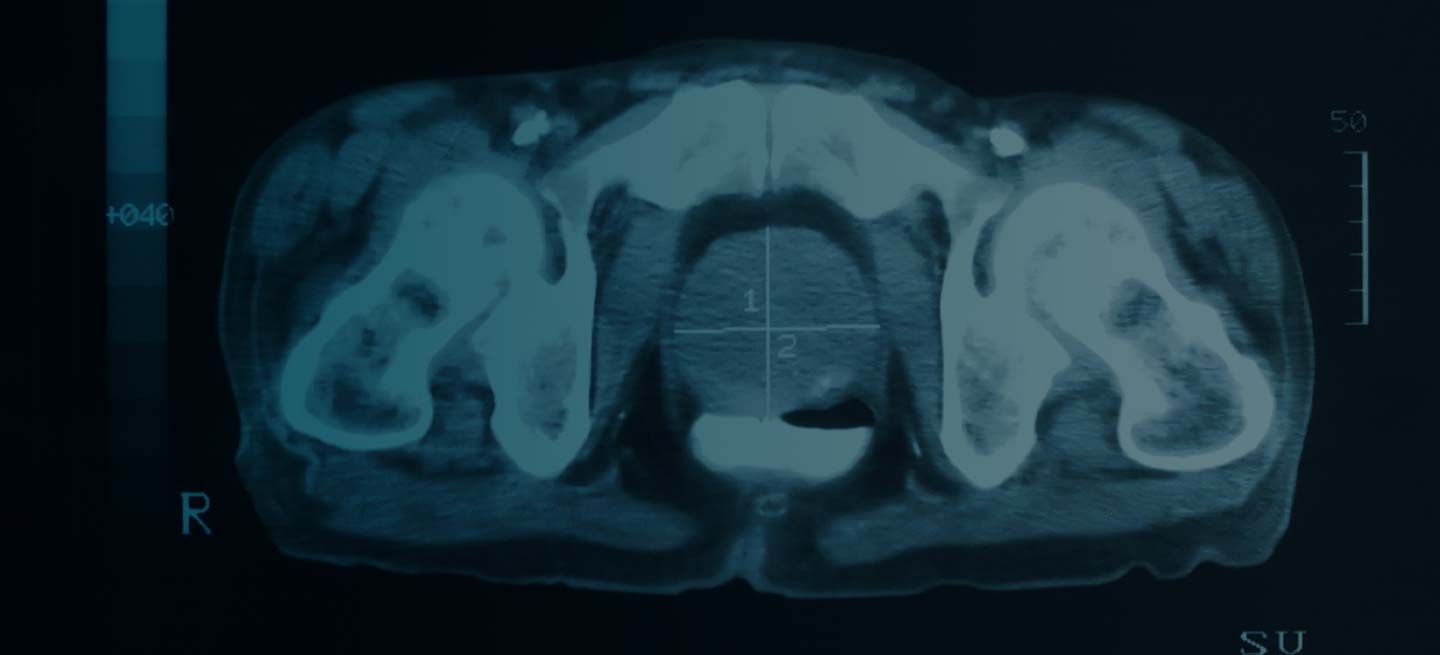

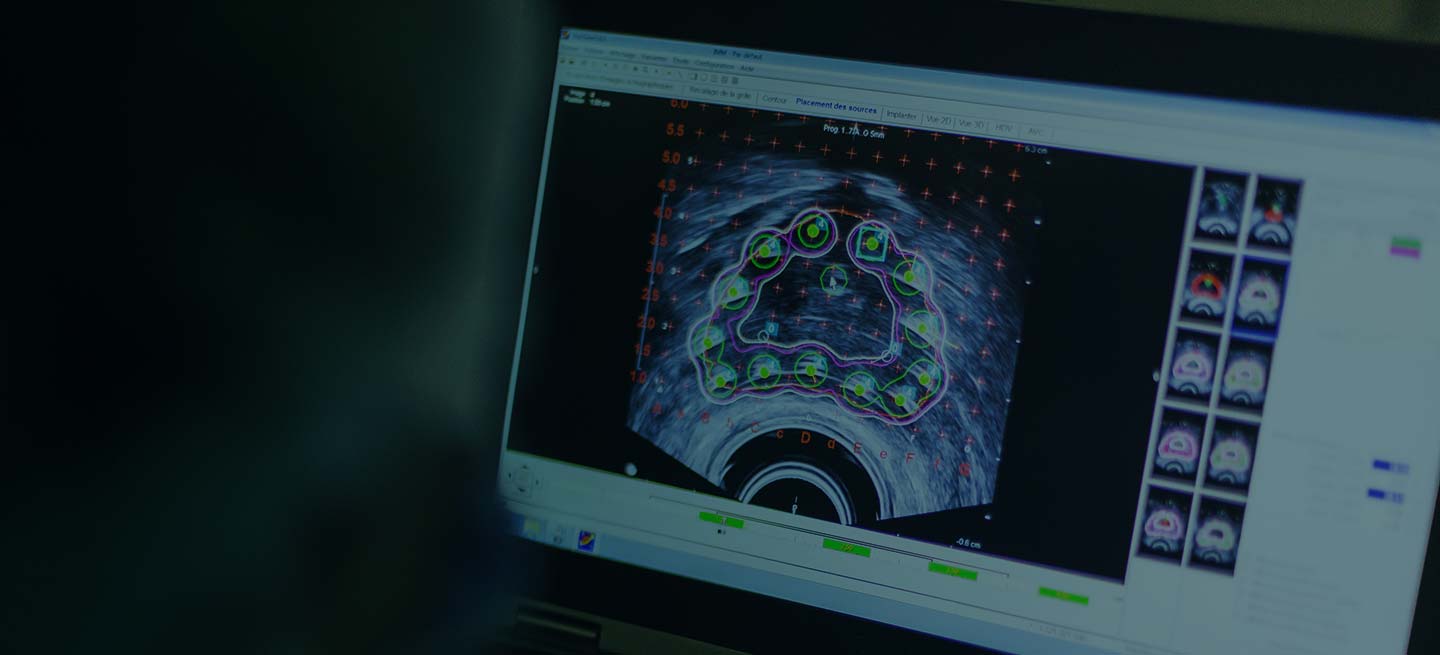

Transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS)–guided needle biopsy of the prostate confirms a diagnosis of high-grade prostate cancer, and the digital rectal exam and CT scan are concerning for extracapsular invasion. Genetic and molecular biomarker testing is recommended.

According to GLOBOCAN 2020 data, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in men (second only to lung cancer) and the fifth leading cause of death globally. Compared with other races, the incidence of prostate cancer in the United States is highest in Black men, and mortality rates are more than double than those reported in White men. In its early stages, prostate cancer is often asymptomatic and has an indolent course. Locally advanced prostate cancer is a clinical scenario in which the cancer has extended beyond the prostatic capsule. It involves invasion of the pericapsular tissue, bladder neck, or seminal vesicles, without lymph node involvement or distant metastases. Biological recurrence, metastatic progression, and poor survival are associated with locally advanced prostate cancer.

In the presence of advanced disease, troublesome lower urinary tract symptoms — particularly abnormal growth of prostate cancer–induced bladder outlet obstruction — are often reported. Such symptoms have a significant impact on patients' quality of life. Other symptoms of locally advanced disease may include hematuria, pain, urinary retention, urinary incontinence, hematospermia, painful ejaculation, anejaculation, constipation, and hematochezia.

Guideline-based approaches to the management of prostate cancer begin with appropriate risk stratification based on biopsy, physical examination, and imaging evaluation. In patients with advanced prostate cancer, treatment decisions should incorporate a multidisciplinary approach and include consideration of life expectancy, comorbidities, patient preferences, and tumor characteristics. Establishing whether the patient has widely advanced disease vs locally advanced disease (clinical stage T3) is helpful for ascertaining which treatment options are available. Pain control and other supportive therapies should be optimized in cases involving advanced prostate cancer.

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), combined with luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists or surgical castration, is considered first-line treatment for advanced metastatic prostate cancer. Abundant data show that ADT in advanced symptomatic metastatic prostate cancer, either in the form of surgical castration or LHRH analogues, is beneficial chiefly for palliation of symptoms. However, the combination of ADT with radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy has been shown to improve overall and cancer-specific survival in selected patients with nonmetastatic but locally advanced prostate cancer. Recently, a prospective study showed a significant improvement in urodynamic variables and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) questionnaire results, including IPSS-related quality of life, in patients with advanced cancer who received ADT, although lower urinary tract symptoms persist in some patients.

For patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC), continued treatment with ADT in combination with either androgen pathway–directed therapy (abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, apalutamide, enzalutamide) or chemotherapy (docetaxel) is generally recommended. A recent meta-analysis found that the next-generation androgen receptor inhibitors abiraterone, apalutamide, and enzalutamide appear to be significantly more effective than ADT and more effective than docetaxel for mHSPC; apalutamide was the best tolerated. For selected patients with mHSPC with low-volume metastatic disease, primary radiation therapy to the prostate in combination with ADT may be offered. First-generation antiandrogens (bicalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) in combination with LHRH agonists are not recommended for patients with mHSPC, unless needed to block testosterone flare. In addition, oral androgen pathway–directed therapy (eg, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, apalutamide, bicalutamide, darolutamide, enzalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) without ADT is not recommended for patients with mHSPC.

In patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC), darolutamide, apalutamide, and enzalutamide with continued ADT have been shown to postpone the onset of metastases and death. Unless within the context of a clinical trial, systemic chemotherapy or immunotherapy should not be offered to patients with nmCRPC.

For patients with newly diagnosed metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), continued ADT with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, docetaxel, or enzalutamide is recommended. For patients with mCRPC who are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, sipuleucel-T may be offered. At present, radium-223 is the only available therapy for mCRPC that specifically targets bone metastases, delays development of skeletal-related events, and improves survival. On the basis of results of the ALSYMPCA study, radium-223 in combination with systemic therapies is now considered an effective, efficient, and well-tolerated therapy for patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer with bone lesions. The effects of local radiation therapy for men with metastatic prostate cancer and the optimal combination of systemic therapies in the metastatic setting are still under investigation.

Complete recommendations on sequencing agents and selecting therapies for patients with advanced prostate cancer can be found in guidelines from the American Urological Association, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the European Association of Urology.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS)–guided needle biopsy of the prostate confirms a diagnosis of high-grade prostate cancer, and the digital rectal exam and CT scan are concerning for extracapsular invasion. Genetic and molecular biomarker testing is recommended.

According to GLOBOCAN 2020 data, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in men (second only to lung cancer) and the fifth leading cause of death globally. Compared with other races, the incidence of prostate cancer in the United States is highest in Black men, and mortality rates are more than double than those reported in White men. In its early stages, prostate cancer is often asymptomatic and has an indolent course. Locally advanced prostate cancer is a clinical scenario in which the cancer has extended beyond the prostatic capsule. It involves invasion of the pericapsular tissue, bladder neck, or seminal vesicles, without lymph node involvement or distant metastases. Biological recurrence, metastatic progression, and poor survival are associated with locally advanced prostate cancer.

In the presence of advanced disease, troublesome lower urinary tract symptoms — particularly abnormal growth of prostate cancer–induced bladder outlet obstruction — are often reported. Such symptoms have a significant impact on patients' quality of life. Other symptoms of locally advanced disease may include hematuria, pain, urinary retention, urinary incontinence, hematospermia, painful ejaculation, anejaculation, constipation, and hematochezia.

Guideline-based approaches to the management of prostate cancer begin with appropriate risk stratification based on biopsy, physical examination, and imaging evaluation. In patients with advanced prostate cancer, treatment decisions should incorporate a multidisciplinary approach and include consideration of life expectancy, comorbidities, patient preferences, and tumor characteristics. Establishing whether the patient has widely advanced disease vs locally advanced disease (clinical stage T3) is helpful for ascertaining which treatment options are available. Pain control and other supportive therapies should be optimized in cases involving advanced prostate cancer.

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), combined with luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists or surgical castration, is considered first-line treatment for advanced metastatic prostate cancer. Abundant data show that ADT in advanced symptomatic metastatic prostate cancer, either in the form of surgical castration or LHRH analogues, is beneficial chiefly for palliation of symptoms. However, the combination of ADT with radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy has been shown to improve overall and cancer-specific survival in selected patients with nonmetastatic but locally advanced prostate cancer. Recently, a prospective study showed a significant improvement in urodynamic variables and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) questionnaire results, including IPSS-related quality of life, in patients with advanced cancer who received ADT, although lower urinary tract symptoms persist in some patients.

For patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC), continued treatment with ADT in combination with either androgen pathway–directed therapy (abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, apalutamide, enzalutamide) or chemotherapy (docetaxel) is generally recommended. A recent meta-analysis found that the next-generation androgen receptor inhibitors abiraterone, apalutamide, and enzalutamide appear to be significantly more effective than ADT and more effective than docetaxel for mHSPC; apalutamide was the best tolerated. For selected patients with mHSPC with low-volume metastatic disease, primary radiation therapy to the prostate in combination with ADT may be offered. First-generation antiandrogens (bicalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) in combination with LHRH agonists are not recommended for patients with mHSPC, unless needed to block testosterone flare. In addition, oral androgen pathway–directed therapy (eg, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, apalutamide, bicalutamide, darolutamide, enzalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) without ADT is not recommended for patients with mHSPC.

In patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC), darolutamide, apalutamide, and enzalutamide with continued ADT have been shown to postpone the onset of metastases and death. Unless within the context of a clinical trial, systemic chemotherapy or immunotherapy should not be offered to patients with nmCRPC.

For patients with newly diagnosed metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), continued ADT with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, docetaxel, or enzalutamide is recommended. For patients with mCRPC who are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, sipuleucel-T may be offered. At present, radium-223 is the only available therapy for mCRPC that specifically targets bone metastases, delays development of skeletal-related events, and improves survival. On the basis of results of the ALSYMPCA study, radium-223 in combination with systemic therapies is now considered an effective, efficient, and well-tolerated therapy for patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer with bone lesions. The effects of local radiation therapy for men with metastatic prostate cancer and the optimal combination of systemic therapies in the metastatic setting are still under investigation.

Complete recommendations on sequencing agents and selecting therapies for patients with advanced prostate cancer can be found in guidelines from the American Urological Association, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the European Association of Urology.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS)–guided needle biopsy of the prostate confirms a diagnosis of high-grade prostate cancer, and the digital rectal exam and CT scan are concerning for extracapsular invasion. Genetic and molecular biomarker testing is recommended.

According to GLOBOCAN 2020 data, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in men (second only to lung cancer) and the fifth leading cause of death globally. Compared with other races, the incidence of prostate cancer in the United States is highest in Black men, and mortality rates are more than double than those reported in White men. In its early stages, prostate cancer is often asymptomatic and has an indolent course. Locally advanced prostate cancer is a clinical scenario in which the cancer has extended beyond the prostatic capsule. It involves invasion of the pericapsular tissue, bladder neck, or seminal vesicles, without lymph node involvement or distant metastases. Biological recurrence, metastatic progression, and poor survival are associated with locally advanced prostate cancer.

In the presence of advanced disease, troublesome lower urinary tract symptoms — particularly abnormal growth of prostate cancer–induced bladder outlet obstruction — are often reported. Such symptoms have a significant impact on patients' quality of life. Other symptoms of locally advanced disease may include hematuria, pain, urinary retention, urinary incontinence, hematospermia, painful ejaculation, anejaculation, constipation, and hematochezia.

Guideline-based approaches to the management of prostate cancer begin with appropriate risk stratification based on biopsy, physical examination, and imaging evaluation. In patients with advanced prostate cancer, treatment decisions should incorporate a multidisciplinary approach and include consideration of life expectancy, comorbidities, patient preferences, and tumor characteristics. Establishing whether the patient has widely advanced disease vs locally advanced disease (clinical stage T3) is helpful for ascertaining which treatment options are available. Pain control and other supportive therapies should be optimized in cases involving advanced prostate cancer.

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), combined with luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists or surgical castration, is considered first-line treatment for advanced metastatic prostate cancer. Abundant data show that ADT in advanced symptomatic metastatic prostate cancer, either in the form of surgical castration or LHRH analogues, is beneficial chiefly for palliation of symptoms. However, the combination of ADT with radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy has been shown to improve overall and cancer-specific survival in selected patients with nonmetastatic but locally advanced prostate cancer. Recently, a prospective study showed a significant improvement in urodynamic variables and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) questionnaire results, including IPSS-related quality of life, in patients with advanced cancer who received ADT, although lower urinary tract symptoms persist in some patients.

For patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC), continued treatment with ADT in combination with either androgen pathway–directed therapy (abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, apalutamide, enzalutamide) or chemotherapy (docetaxel) is generally recommended. A recent meta-analysis found that the next-generation androgen receptor inhibitors abiraterone, apalutamide, and enzalutamide appear to be significantly more effective than ADT and more effective than docetaxel for mHSPC; apalutamide was the best tolerated. For selected patients with mHSPC with low-volume metastatic disease, primary radiation therapy to the prostate in combination with ADT may be offered. First-generation antiandrogens (bicalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) in combination with LHRH agonists are not recommended for patients with mHSPC, unless needed to block testosterone flare. In addition, oral androgen pathway–directed therapy (eg, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, apalutamide, bicalutamide, darolutamide, enzalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) without ADT is not recommended for patients with mHSPC.

In patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC), darolutamide, apalutamide, and enzalutamide with continued ADT have been shown to postpone the onset of metastases and death. Unless within the context of a clinical trial, systemic chemotherapy or immunotherapy should not be offered to patients with nmCRPC.

For patients with newly diagnosed metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), continued ADT with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, docetaxel, or enzalutamide is recommended. For patients with mCRPC who are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, sipuleucel-T may be offered. At present, radium-223 is the only available therapy for mCRPC that specifically targets bone metastases, delays development of skeletal-related events, and improves survival. On the basis of results of the ALSYMPCA study, radium-223 in combination with systemic therapies is now considered an effective, efficient, and well-tolerated therapy for patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer with bone lesions. The effects of local radiation therapy for men with metastatic prostate cancer and the optimal combination of systemic therapies in the metastatic setting are still under investigation.

Complete recommendations on sequencing agents and selecting therapies for patients with advanced prostate cancer can be found in guidelines from the American Urological Association, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the European Association of Urology.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 58-year-old Black man presents with abdominal pain, urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, incomplete voiding, and postmicturition dribble. The patient's medical history is unremarkable apart from stage 1 hypertension, for which he receives losartan plus amlodipine. Physical examination findings reveal an overdistended bladder with associated tenderness and a mildly enlarged prostate with a large, firm nodule on digital rectal exam. Urinalysis shows hematuria. Complete blood count and chemistry panel are normal. The total prostate-specific antigen level is 22 ng/mL.

Prostate Cancer – Diagnosis and Staging

Sudden onset of severe pain in left thigh

On the basis of the patient's physical examination, laboratory findings, and radiographic findings, a diagnosis of de novo metastatic prostate cancer is suspected and later confirmed by transrectal ultrasonography–guided needle biopsy of the prostate.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-associated death in men in the United States. Among men diagnosed with prostate cancer in the United States, approximately three quarters have localized-stage disease at diagnosis; however, recent data show that an increasing number and percentage of men are being diagnosed with distant-stage prostate cancer. Despite advancements in treatment, less than one third of men survive 5 years after the diagnosis of distant-stage prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer frequently metastasizes to the bone. In fact, as many as 90% of patients with advanced prostate cancer have bone involvement. The morbidity from bone metastases is considerable and includes bone pain, immobility, pathologic fractures, hypercalcemia, hematologic disorders, and spinal cord compression. Bone metastases also have a considerable impact on mortality.

In patients with metastatic prostate cancer, determining the presence and extent of metastatic disease is essential for appropriate treatment to be selected. Studies have shown that the extent of metastatic disease affects treatment response. In a recent exploratory analysis of the STAMPEDE trial, survival benefit associated with prostate radiation therapy decreased continuously as the number of bone metastases rose, with the most benefit being seen in patients with up to three bone metastases.

Guidelines recommend that imaging studies be conducted in all patients with advanced prostate cancer. This may include conventional imaging (ie, CT, bone scan, and/or prostate MRI) and/or next-generation imaging (ie, PET, PET/CT, PET/MRI, whole-body MRI). In cases involving hormone-sensitive disease with obvious metastatic disease on conventional imaging at presentation, next-generation imaging may be useful for illuminating the disease burden and possibly shifting the treatment intent from multimodality management of oligometastatic disease to systemic anticancer therapy, either alone or in combination with targeted therapy for palliative purposes. However, prospective data on this are lacking.

Clinicians should also assess symptoms in patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer at presentation, because symptoms have been shown to have prognostic value. In addition, understanding symptoms related to cancer is essential for optimizing pain and other symptom management in addition to anticancer therapy.

Metastatic prostate cancer remains incurable. Immediate systemic treatment with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) combined with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone or apalutamide or enzalutamide should be offered to symptomatic patients who have distant metastases on diagnosis, both to alleviate symptoms and to lessen the risk for potential serious complications, such as spinal cord compression. ADT combined with docetaxel can also be offered to patients who are able to tolerate docetaxel.

ADT combined with prostate radiation therapy may be offered to patients with distant metastases and low-volume disease. However, when patients present with high-volume disease, referral to a clinical trial is recommended.

Surgery and/or local radiation therapy can be considered for patients with distant metastases and evidence of impending complications (eg, spinal cord compression or pathologic fracture).

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

On the basis of the patient's physical examination, laboratory findings, and radiographic findings, a diagnosis of de novo metastatic prostate cancer is suspected and later confirmed by transrectal ultrasonography–guided needle biopsy of the prostate.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-associated death in men in the United States. Among men diagnosed with prostate cancer in the United States, approximately three quarters have localized-stage disease at diagnosis; however, recent data show that an increasing number and percentage of men are being diagnosed with distant-stage prostate cancer. Despite advancements in treatment, less than one third of men survive 5 years after the diagnosis of distant-stage prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer frequently metastasizes to the bone. In fact, as many as 90% of patients with advanced prostate cancer have bone involvement. The morbidity from bone metastases is considerable and includes bone pain, immobility, pathologic fractures, hypercalcemia, hematologic disorders, and spinal cord compression. Bone metastases also have a considerable impact on mortality.

In patients with metastatic prostate cancer, determining the presence and extent of metastatic disease is essential for appropriate treatment to be selected. Studies have shown that the extent of metastatic disease affects treatment response. In a recent exploratory analysis of the STAMPEDE trial, survival benefit associated with prostate radiation therapy decreased continuously as the number of bone metastases rose, with the most benefit being seen in patients with up to three bone metastases.

Guidelines recommend that imaging studies be conducted in all patients with advanced prostate cancer. This may include conventional imaging (ie, CT, bone scan, and/or prostate MRI) and/or next-generation imaging (ie, PET, PET/CT, PET/MRI, whole-body MRI). In cases involving hormone-sensitive disease with obvious metastatic disease on conventional imaging at presentation, next-generation imaging may be useful for illuminating the disease burden and possibly shifting the treatment intent from multimodality management of oligometastatic disease to systemic anticancer therapy, either alone or in combination with targeted therapy for palliative purposes. However, prospective data on this are lacking.

Clinicians should also assess symptoms in patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer at presentation, because symptoms have been shown to have prognostic value. In addition, understanding symptoms related to cancer is essential for optimizing pain and other symptom management in addition to anticancer therapy.

Metastatic prostate cancer remains incurable. Immediate systemic treatment with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) combined with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone or apalutamide or enzalutamide should be offered to symptomatic patients who have distant metastases on diagnosis, both to alleviate symptoms and to lessen the risk for potential serious complications, such as spinal cord compression. ADT combined with docetaxel can also be offered to patients who are able to tolerate docetaxel.

ADT combined with prostate radiation therapy may be offered to patients with distant metastases and low-volume disease. However, when patients present with high-volume disease, referral to a clinical trial is recommended.

Surgery and/or local radiation therapy can be considered for patients with distant metastases and evidence of impending complications (eg, spinal cord compression or pathologic fracture).

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

On the basis of the patient's physical examination, laboratory findings, and radiographic findings, a diagnosis of de novo metastatic prostate cancer is suspected and later confirmed by transrectal ultrasonography–guided needle biopsy of the prostate.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-associated death in men in the United States. Among men diagnosed with prostate cancer in the United States, approximately three quarters have localized-stage disease at diagnosis; however, recent data show that an increasing number and percentage of men are being diagnosed with distant-stage prostate cancer. Despite advancements in treatment, less than one third of men survive 5 years after the diagnosis of distant-stage prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer frequently metastasizes to the bone. In fact, as many as 90% of patients with advanced prostate cancer have bone involvement. The morbidity from bone metastases is considerable and includes bone pain, immobility, pathologic fractures, hypercalcemia, hematologic disorders, and spinal cord compression. Bone metastases also have a considerable impact on mortality.

In patients with metastatic prostate cancer, determining the presence and extent of metastatic disease is essential for appropriate treatment to be selected. Studies have shown that the extent of metastatic disease affects treatment response. In a recent exploratory analysis of the STAMPEDE trial, survival benefit associated with prostate radiation therapy decreased continuously as the number of bone metastases rose, with the most benefit being seen in patients with up to three bone metastases.

Guidelines recommend that imaging studies be conducted in all patients with advanced prostate cancer. This may include conventional imaging (ie, CT, bone scan, and/or prostate MRI) and/or next-generation imaging (ie, PET, PET/CT, PET/MRI, whole-body MRI). In cases involving hormone-sensitive disease with obvious metastatic disease on conventional imaging at presentation, next-generation imaging may be useful for illuminating the disease burden and possibly shifting the treatment intent from multimodality management of oligometastatic disease to systemic anticancer therapy, either alone or in combination with targeted therapy for palliative purposes. However, prospective data on this are lacking.

Clinicians should also assess symptoms in patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer at presentation, because symptoms have been shown to have prognostic value. In addition, understanding symptoms related to cancer is essential for optimizing pain and other symptom management in addition to anticancer therapy.

Metastatic prostate cancer remains incurable. Immediate systemic treatment with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) combined with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone or apalutamide or enzalutamide should be offered to symptomatic patients who have distant metastases on diagnosis, both to alleviate symptoms and to lessen the risk for potential serious complications, such as spinal cord compression. ADT combined with docetaxel can also be offered to patients who are able to tolerate docetaxel.

ADT combined with prostate radiation therapy may be offered to patients with distant metastases and low-volume disease. However, when patients present with high-volume disease, referral to a clinical trial is recommended.

Surgery and/or local radiation therapy can be considered for patients with distant metastases and evidence of impending complications (eg, spinal cord compression or pathologic fracture).

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

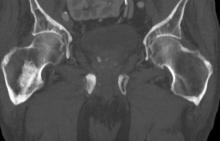

A 74-year-old man presents to the emergency department with sudden onset of severe pain in his left thigh, a 3-month history of unexplained weight loss and general weakness, and progressive difficulty in walking for the past 3 weeks. The patient states that he has always been in excellent health and he has not seen a physician in at least 10 years. Cachexia is noted on physical examination. Laboratory findings include hemoglobin, 12.4 g/dL; white blood cells, 8.12 cells/µL; platelets, 310,000 cells/µL; creatinine, 1.4 mg/dL; sodium, 137 mmol/L; potassium, 4.4 mmol/L; calcium, 10.1 mg/dL; prostate-specific antigen, 31 ng/mL; aspartate aminotransferase, 37 IU/L; and gamma-glutamyltransferase, 16 IU/L. Proteinuria and hematuria are detected by urinalysis. CT reveals multiple diffuse osteoblastic lesions in the right proximal femur.

Intermittent fever and gradually progressive low back pain

Transrectal ultrasonography–guided needle biopsy of the prostate confirms a diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer.

With the exception of nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most commonly occurring cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-associated mortality in men in the United States. Most patients have localized stage at diagnosis; however, the incidence of distant-stage prostate cancer at diagnosis is steadily increasing. Five-year survival for distant-stage prostate cancer is approximately 32%.

High serum levels of PSA have been associated with bone metastases in men with prostate cancer, and the presence of metastatic disease increases with rising PSA levels. Over the past several decades, PSA levels > 100 ng/mL have been used as a marker for metastatic prostate cancer. However, not all men with metastatic prostate cancer will have elevated PSA levels, and bone imaging is necessary for correct staging and treatment stratification.

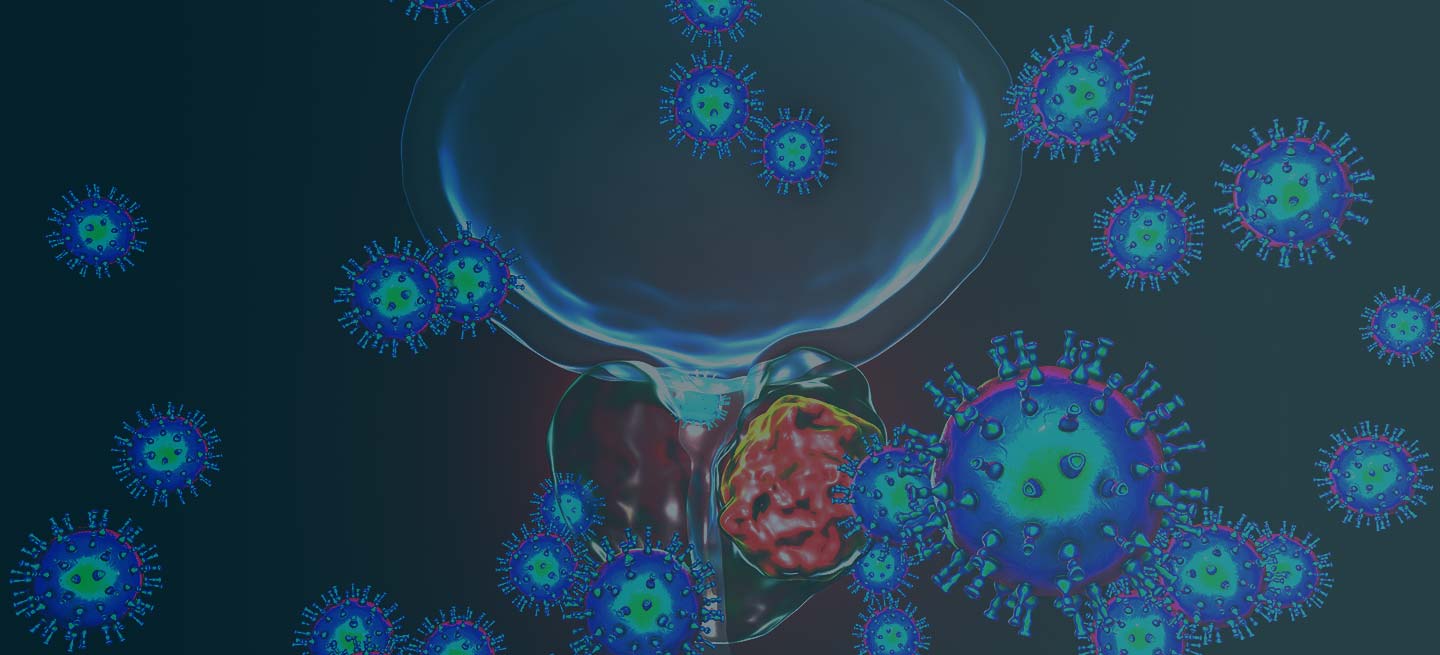

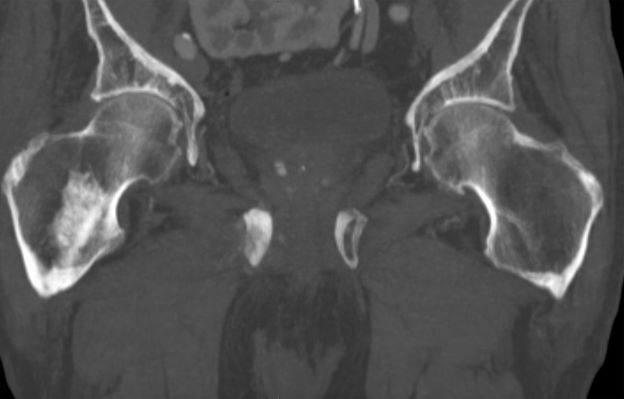

Bone metastases occur in approximately 70% of men with advanced prostate cancer, most often in the spine, and are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Bone metastases can cause severe pain, particularly in the evening; decreased mobility; pathologic fractures; spinal cord compression; bone marrow aplasia; and hypercalcemia.

The bone marrow represents a fertile soil into which prostate tumors can colonize and proliferate. Such colonization by prostate tumor cells is commonly associated with tumor-induced bone lesions, which typically arise from an imbalance between bone-forming osteoblasts and bone-absorbing osteoclasts generated by prostate cancer cells. Whereas most solid tumors, such as breast cancer and melanoma, have a propensity for causing osteolytic lesions with excessive bone resorption, bone lesions resulting from prostate cancer are largely osteoblastic and are associated with uncontrolled low-quality bone formation. The resultant metastases have a unique bone formation that can be detected by plain radiography, bone scan, bone biopsy, and increased serum alkaline phosphatase levels.

CT; skeletal scintigraphy and PET; and single-photon emission CT (SPECT)/CT, PET/CT, and PET/MRI are recommended diagnostics for men at risk for prostate cancer metastasis. Radiotracer-based PET, which mainly uses altered metabolic activity or explicitly overexpressed receptors, is a promising diagnostic modality. However, the choice of a respective radiotracer must be carefully considered because a single radiotracer is typically insufficient to visualize all clinical stages of prostate cancer. In addition, its use is reliant on the extent of malignant tissue, tumor heterogeneity, and previous treatments.

Systemic androgen-deprivation therapy, with or without docetaxel-based chemotherapy, is the standard of care for metastatic prostate cancer. Treatment is largely directed at preventing skeletal-related events and providing pain management.

Radium-223 is the only available therapy for castrate-resistant prostate cancer that specifically targets bone metastases, delays development of skeletal-related events, and improves survival. Based on the results of the ALSYMPCA study, radium-223 in combination with systemic therapies is now considered an effective, efficient, and well-tolerated therapy for castrate-resistant prostate cancer with bone lesions.

The effects of local radiation therapy for men with metastatic prostate cancer and the optimal combination of systemic therapies in the metastatic setting are still under investigation.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Transrectal ultrasonography–guided needle biopsy of the prostate confirms a diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer.

With the exception of nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most commonly occurring cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-associated mortality in men in the United States. Most patients have localized stage at diagnosis; however, the incidence of distant-stage prostate cancer at diagnosis is steadily increasing. Five-year survival for distant-stage prostate cancer is approximately 32%.

High serum levels of PSA have been associated with bone metastases in men with prostate cancer, and the presence of metastatic disease increases with rising PSA levels. Over the past several decades, PSA levels > 100 ng/mL have been used as a marker for metastatic prostate cancer. However, not all men with metastatic prostate cancer will have elevated PSA levels, and bone imaging is necessary for correct staging and treatment stratification.

Bone metastases occur in approximately 70% of men with advanced prostate cancer, most often in the spine, and are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Bone metastases can cause severe pain, particularly in the evening; decreased mobility; pathologic fractures; spinal cord compression; bone marrow aplasia; and hypercalcemia.

The bone marrow represents a fertile soil into which prostate tumors can colonize and proliferate. Such colonization by prostate tumor cells is commonly associated with tumor-induced bone lesions, which typically arise from an imbalance between bone-forming osteoblasts and bone-absorbing osteoclasts generated by prostate cancer cells. Whereas most solid tumors, such as breast cancer and melanoma, have a propensity for causing osteolytic lesions with excessive bone resorption, bone lesions resulting from prostate cancer are largely osteoblastic and are associated with uncontrolled low-quality bone formation. The resultant metastases have a unique bone formation that can be detected by plain radiography, bone scan, bone biopsy, and increased serum alkaline phosphatase levels.

CT; skeletal scintigraphy and PET; and single-photon emission CT (SPECT)/CT, PET/CT, and PET/MRI are recommended diagnostics for men at risk for prostate cancer metastasis. Radiotracer-based PET, which mainly uses altered metabolic activity or explicitly overexpressed receptors, is a promising diagnostic modality. However, the choice of a respective radiotracer must be carefully considered because a single radiotracer is typically insufficient to visualize all clinical stages of prostate cancer. In addition, its use is reliant on the extent of malignant tissue, tumor heterogeneity, and previous treatments.

Systemic androgen-deprivation therapy, with or without docetaxel-based chemotherapy, is the standard of care for metastatic prostate cancer. Treatment is largely directed at preventing skeletal-related events and providing pain management.

Radium-223 is the only available therapy for castrate-resistant prostate cancer that specifically targets bone metastases, delays development of skeletal-related events, and improves survival. Based on the results of the ALSYMPCA study, radium-223 in combination with systemic therapies is now considered an effective, efficient, and well-tolerated therapy for castrate-resistant prostate cancer with bone lesions.

The effects of local radiation therapy for men with metastatic prostate cancer and the optimal combination of systemic therapies in the metastatic setting are still under investigation.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Transrectal ultrasonography–guided needle biopsy of the prostate confirms a diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer.

With the exception of nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most commonly occurring cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-associated mortality in men in the United States. Most patients have localized stage at diagnosis; however, the incidence of distant-stage prostate cancer at diagnosis is steadily increasing. Five-year survival for distant-stage prostate cancer is approximately 32%.

High serum levels of PSA have been associated with bone metastases in men with prostate cancer, and the presence of metastatic disease increases with rising PSA levels. Over the past several decades, PSA levels > 100 ng/mL have been used as a marker for metastatic prostate cancer. However, not all men with metastatic prostate cancer will have elevated PSA levels, and bone imaging is necessary for correct staging and treatment stratification.

Bone metastases occur in approximately 70% of men with advanced prostate cancer, most often in the spine, and are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Bone metastases can cause severe pain, particularly in the evening; decreased mobility; pathologic fractures; spinal cord compression; bone marrow aplasia; and hypercalcemia.

The bone marrow represents a fertile soil into which prostate tumors can colonize and proliferate. Such colonization by prostate tumor cells is commonly associated with tumor-induced bone lesions, which typically arise from an imbalance between bone-forming osteoblasts and bone-absorbing osteoclasts generated by prostate cancer cells. Whereas most solid tumors, such as breast cancer and melanoma, have a propensity for causing osteolytic lesions with excessive bone resorption, bone lesions resulting from prostate cancer are largely osteoblastic and are associated with uncontrolled low-quality bone formation. The resultant metastases have a unique bone formation that can be detected by plain radiography, bone scan, bone biopsy, and increased serum alkaline phosphatase levels.

CT; skeletal scintigraphy and PET; and single-photon emission CT (SPECT)/CT, PET/CT, and PET/MRI are recommended diagnostics for men at risk for prostate cancer metastasis. Radiotracer-based PET, which mainly uses altered metabolic activity or explicitly overexpressed receptors, is a promising diagnostic modality. However, the choice of a respective radiotracer must be carefully considered because a single radiotracer is typically insufficient to visualize all clinical stages of prostate cancer. In addition, its use is reliant on the extent of malignant tissue, tumor heterogeneity, and previous treatments.

Systemic androgen-deprivation therapy, with or without docetaxel-based chemotherapy, is the standard of care for metastatic prostate cancer. Treatment is largely directed at preventing skeletal-related events and providing pain management.

Radium-223 is the only available therapy for castrate-resistant prostate cancer that specifically targets bone metastases, delays development of skeletal-related events, and improves survival. Based on the results of the ALSYMPCA study, radium-223 in combination with systemic therapies is now considered an effective, efficient, and well-tolerated therapy for castrate-resistant prostate cancer with bone lesions.

The effects of local radiation therapy for men with metastatic prostate cancer and the optimal combination of systemic therapies in the metastatic setting are still under investigation.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 71-year-old homeless man presents to the emergency department (ED) with intermittent fever, gradually progressive low back pain restricting physical activities and movement, fatigue, exertional dyspnea, and poor appetite. The patient has been seen in the same ED sporadically over the years for various problems, and his medical history is notable for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, tobacco use, alcoholism, and foot infections. Physical examination findings include tenderness to percussion over the thoracic and lumbar spine and a mildly enlarged prostate that appears to be smooth, normal in texture, and lacking nodules on digital rectal exam. Complete blood cell count and chemistry panel are normal. Both alkaline phosphatase and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels are elevated, at 240 U/L and 115 ng/mL, respectively. Urinalysis shows hematuria. CT shows osteolytic lesions in the patient's lumbar spine and femur.