User login

PsA Imaging

Progressive joint pain and swelling

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is consistent with the patient's joint pain, dactylitis, enthesitis, skin plaques, and radiographic findings, making it the most likely diagnosis.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is possible because of the patient's joint symptoms; however, it is not the correct answer because of negative RF and ACPA tests and skin plaques.

Osteoarthritis might cause joint pain but does not typically present with prolonged morning stiffness, skin plaques, or the "pencil-in-cup" radiographic finding.

Gout, an inflammatory arthritis, primarily affects the big toe and does not align with the patient's skin and radiographic manifestations.

PsA is a chronic inflammatory arthritis that often develops in people with psoriasis. It affects roughly 0.05%- 0.25% of the general population and up to 41% of people with psoriasis. PsA is most seen in White patients between 35 and 55 years and affects both men and women equally. PsA is linked to a higher risk for obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and other conditions, including uveitis and inflammatory bowel disease.

Clinically, PsA presents with a diverse range of manifestations, encompassing peripheral joint inflammation, often with an asymmetric distribution; axial skeletal involvement reminiscent of spondylitis; dactylitis characterized by sausage-like swelling of fingers or toes; and enthesitis. Common symptoms or findings include early morning stiffness for > 30 minutes; joint pain, tenderness, and swelling; back pain aggravated by rest and relieved by exercise; limited joint motion; and deformity. Although most patients have a preceding condition in skin psoriasis, diagnosis of PsA is often delayed. Furthermore, nearly 80% of patients may exhibit nail changes, such as pitting or onycholysis, compared with about 40% of patients with psoriasis without arthritis. The heterogeneity of its clinical features often necessitates a comprehensive differential diagnosis to distinguish PsA from other spondyloarthropathies and rheumatic diseases. The most accepted classification criteria for PsA are the Classification of Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) criteria, which have been used since 2006.

No laboratory tests are specific for PsA; however, a normal ESR and CRP level should not be used to rule out a diagnosis of PsA because these values are increased in only about 40% of patients. RF and ACPA are classically considered absent in PsA, and a negative RF is regarded as a criterion for diagnosing PsA per the CASPAR classification criteria. Radiographic changes show some characteristic patterns in PsA, including erosive damage, gross joint destruction, joint space narrowing, and "pencil-in-cup" deformity.

PsA treatment options have evolved over the years. Whereas in the past, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and cyclosporine were commonly prescribed, the development of immunologically targeted biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and targeted synthetic DMARDs since 2000 has revolutionized the treatment of PsA. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (ie, etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab) have been shown to improve all domains (psoriatic and articular disease) of PsA and are considered a milestone in managing the condition. Other emerging therapeutic strategies in recent years have demonstrated efficacy in treating PsA, including monoclonal antibodies targeting interleukin (IL)-12, IL-23, and IL-17, as well as small-molecule phosphodiesterase 4 and Janus kinase inhibitors.

Although most of these options have the potential to be effective in all clinical domains of the disease, their cross-domain efficacy can vary from patient to patient. In some cases, treatment may not be practical or can lose effectiveness over time, and true disease remission is rare. As a result, clinicians must regularly assess each domain and aim to achieve remission or low disease activity across the different active domains while also being aware of potential adverse events.

Alan Irvine, MD, DSc, Consultant Dermatologist, ADI Dermatology LTD, Dublin, Ireland

Alan Irvine, MD, DSc, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Serve(d) as a speaker or member of a speakers bureau for: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is consistent with the patient's joint pain, dactylitis, enthesitis, skin plaques, and radiographic findings, making it the most likely diagnosis.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is possible because of the patient's joint symptoms; however, it is not the correct answer because of negative RF and ACPA tests and skin plaques.

Osteoarthritis might cause joint pain but does not typically present with prolonged morning stiffness, skin plaques, or the "pencil-in-cup" radiographic finding.

Gout, an inflammatory arthritis, primarily affects the big toe and does not align with the patient's skin and radiographic manifestations.

PsA is a chronic inflammatory arthritis that often develops in people with psoriasis. It affects roughly 0.05%- 0.25% of the general population and up to 41% of people with psoriasis. PsA is most seen in White patients between 35 and 55 years and affects both men and women equally. PsA is linked to a higher risk for obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and other conditions, including uveitis and inflammatory bowel disease.

Clinically, PsA presents with a diverse range of manifestations, encompassing peripheral joint inflammation, often with an asymmetric distribution; axial skeletal involvement reminiscent of spondylitis; dactylitis characterized by sausage-like swelling of fingers or toes; and enthesitis. Common symptoms or findings include early morning stiffness for > 30 minutes; joint pain, tenderness, and swelling; back pain aggravated by rest and relieved by exercise; limited joint motion; and deformity. Although most patients have a preceding condition in skin psoriasis, diagnosis of PsA is often delayed. Furthermore, nearly 80% of patients may exhibit nail changes, such as pitting or onycholysis, compared with about 40% of patients with psoriasis without arthritis. The heterogeneity of its clinical features often necessitates a comprehensive differential diagnosis to distinguish PsA from other spondyloarthropathies and rheumatic diseases. The most accepted classification criteria for PsA are the Classification of Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) criteria, which have been used since 2006.

No laboratory tests are specific for PsA; however, a normal ESR and CRP level should not be used to rule out a diagnosis of PsA because these values are increased in only about 40% of patients. RF and ACPA are classically considered absent in PsA, and a negative RF is regarded as a criterion for diagnosing PsA per the CASPAR classification criteria. Radiographic changes show some characteristic patterns in PsA, including erosive damage, gross joint destruction, joint space narrowing, and "pencil-in-cup" deformity.

PsA treatment options have evolved over the years. Whereas in the past, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and cyclosporine were commonly prescribed, the development of immunologically targeted biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and targeted synthetic DMARDs since 2000 has revolutionized the treatment of PsA. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (ie, etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab) have been shown to improve all domains (psoriatic and articular disease) of PsA and are considered a milestone in managing the condition. Other emerging therapeutic strategies in recent years have demonstrated efficacy in treating PsA, including monoclonal antibodies targeting interleukin (IL)-12, IL-23, and IL-17, as well as small-molecule phosphodiesterase 4 and Janus kinase inhibitors.

Although most of these options have the potential to be effective in all clinical domains of the disease, their cross-domain efficacy can vary from patient to patient. In some cases, treatment may not be practical or can lose effectiveness over time, and true disease remission is rare. As a result, clinicians must regularly assess each domain and aim to achieve remission or low disease activity across the different active domains while also being aware of potential adverse events.

Alan Irvine, MD, DSc, Consultant Dermatologist, ADI Dermatology LTD, Dublin, Ireland

Alan Irvine, MD, DSc, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Serve(d) as a speaker or member of a speakers bureau for: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is consistent with the patient's joint pain, dactylitis, enthesitis, skin plaques, and radiographic findings, making it the most likely diagnosis.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is possible because of the patient's joint symptoms; however, it is not the correct answer because of negative RF and ACPA tests and skin plaques.

Osteoarthritis might cause joint pain but does not typically present with prolonged morning stiffness, skin plaques, or the "pencil-in-cup" radiographic finding.

Gout, an inflammatory arthritis, primarily affects the big toe and does not align with the patient's skin and radiographic manifestations.

PsA is a chronic inflammatory arthritis that often develops in people with psoriasis. It affects roughly 0.05%- 0.25% of the general population and up to 41% of people with psoriasis. PsA is most seen in White patients between 35 and 55 years and affects both men and women equally. PsA is linked to a higher risk for obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and other conditions, including uveitis and inflammatory bowel disease.

Clinically, PsA presents with a diverse range of manifestations, encompassing peripheral joint inflammation, often with an asymmetric distribution; axial skeletal involvement reminiscent of spondylitis; dactylitis characterized by sausage-like swelling of fingers or toes; and enthesitis. Common symptoms or findings include early morning stiffness for > 30 minutes; joint pain, tenderness, and swelling; back pain aggravated by rest and relieved by exercise; limited joint motion; and deformity. Although most patients have a preceding condition in skin psoriasis, diagnosis of PsA is often delayed. Furthermore, nearly 80% of patients may exhibit nail changes, such as pitting or onycholysis, compared with about 40% of patients with psoriasis without arthritis. The heterogeneity of its clinical features often necessitates a comprehensive differential diagnosis to distinguish PsA from other spondyloarthropathies and rheumatic diseases. The most accepted classification criteria for PsA are the Classification of Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) criteria, which have been used since 2006.

No laboratory tests are specific for PsA; however, a normal ESR and CRP level should not be used to rule out a diagnosis of PsA because these values are increased in only about 40% of patients. RF and ACPA are classically considered absent in PsA, and a negative RF is regarded as a criterion for diagnosing PsA per the CASPAR classification criteria. Radiographic changes show some characteristic patterns in PsA, including erosive damage, gross joint destruction, joint space narrowing, and "pencil-in-cup" deformity.

PsA treatment options have evolved over the years. Whereas in the past, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and cyclosporine were commonly prescribed, the development of immunologically targeted biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and targeted synthetic DMARDs since 2000 has revolutionized the treatment of PsA. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (ie, etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab) have been shown to improve all domains (psoriatic and articular disease) of PsA and are considered a milestone in managing the condition. Other emerging therapeutic strategies in recent years have demonstrated efficacy in treating PsA, including monoclonal antibodies targeting interleukin (IL)-12, IL-23, and IL-17, as well as small-molecule phosphodiesterase 4 and Janus kinase inhibitors.

Although most of these options have the potential to be effective in all clinical domains of the disease, their cross-domain efficacy can vary from patient to patient. In some cases, treatment may not be practical or can lose effectiveness over time, and true disease remission is rare. As a result, clinicians must regularly assess each domain and aim to achieve remission or low disease activity across the different active domains while also being aware of potential adverse events.

Alan Irvine, MD, DSc, Consultant Dermatologist, ADI Dermatology LTD, Dublin, Ireland

Alan Irvine, MD, DSc, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Serve(d) as a speaker or member of a speakers bureau for: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 45-year-old man visited the rheumatology clinic with a 6-month history of progressive joint pain and swelling. He described experiencing morning stiffness that lasted about an hour, with the pain showing improvement with activity. Interestingly, he also mentioned having rashes for the past 10 years, which he initially attributed to eczema and managed with over-the-counter creams.

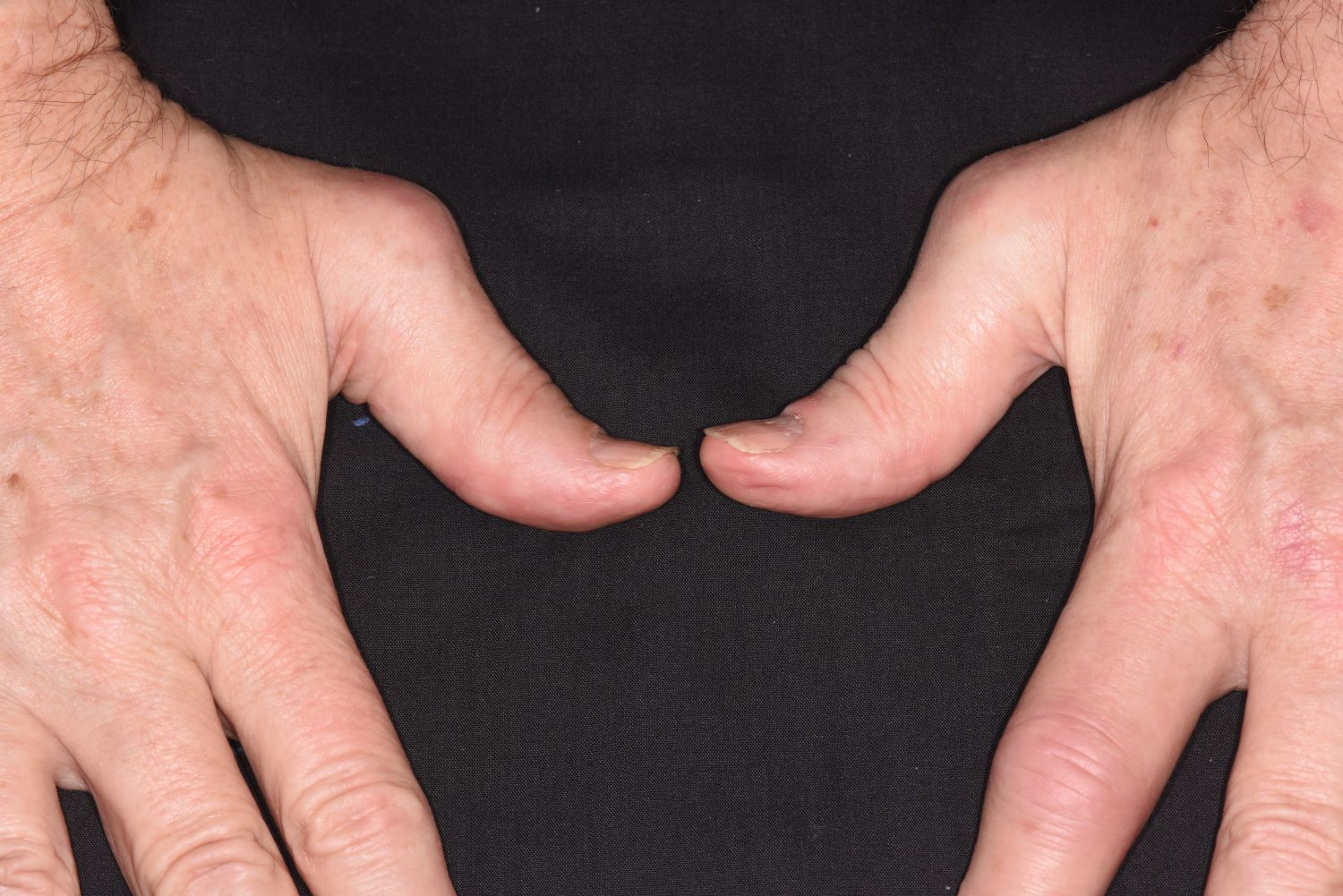

On physical examination, there was noticeable swelling and tenderness in the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints of both hands. The fourth finger on the right hand exhibited dactylitis with a well-circumscribed, erythematous, scaly lesion (see image). Physical exam suggested enthesitis at the insertion of the Achilles tendon. Skin examination revealed plaques with a characteristic silver scaling on the elbows and knees. Laboratory tests indicated elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Notably, both the rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) tests returned negative results. Radiography of the hands showed periarticular erosions and a "pencil-in-cup" deformity at the DIP joints.

Pain in fingers for several months

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an immune-mediated arthritis that is almost always associated with plaque psoriasis. PsA is diagnosed in about 20% of patients with plaque psoriasis, and, in most patients, a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis precedes PsA development. However, in this patient, PsA appears to have become symptomatic at about the same time as the skin symptoms behind his ears, which is consistent with studies showing that PsA co-occurs with plaque psoriasis in 15% of patients and precedes plaque psoriasis diagnosis in 17% of patients. Environmental risk factors for PsA in genetically susceptible patients with plaque psoriasis include joint trauma, streptococcal infection, and certain antibiotics. Smoking appears to have a protective effect in PsA. PsA is more highly associated with severe plaque psoriasis than with mild plaque psoriasis.

PsA has a heterogeneous presentation, which may challenge diagnosis. It is classified by the degree of joint involvement as oligoarticular (four or fewer joints) or polyarticular (five or more joints). Radiographically, there are five main types of PsA, one of which is predominant involvement of the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) joints — the form seen in this patient. The other four types of PsA are symmetrical peripheral polyarthritis, asymmetrical mono- or oligoarthritis, axial spondyloarthropathy, and arthritis mutilans. DIP joint involvement with proliferative bone changes suggests a diagnosis of PsA over rheumatoid arthritis.

PsA is diagnosed using radiography, skin biopsy of affected skin areas, and complete blood and metabolic assessments. With advanced PsA, radiographs typically reveal bone destruction and disease-related bone formation (juxta-articular bone formation), resulting in erosions, joint destruction, and joint-space narrowing. Juxta-articular bone formation (presenting poorly defined ossification adjacent to the joint margin) is often the earliest radiographic clue before erosions may occur. Enthesitis in multiple entheses is typical of PsA vs osteoarthritis or mechanical injury. There are no specific tests to confirm PsA. Patients with PsA usually are rheumatoid factor negative. Inflammatory biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, are elevated in about 40% of patients with PsA.

In addition to plaques, extra-articular manifestations of PsA may include nail changes and chronic bilateral ocular disease. PsA is an articular manifestation of psoriasis but is still a systemic disease with deleterious effects on cardiometabolic factors; increased mortality with myocardial infarction; and possible involvement of other immune-mediated diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, that share a common pathway of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha overexpression.

Early treatment with disease-modifying drugs plus nonpharmacologic interventions is crucial to minimizing disability progression and optimizing patients' quality of life. Nonpharmacologic interventions include physical and occupational therapy and exercise. Symptomatic therapies (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or steroids) can be used to relieve mild symptoms. Assessment for cardiometabolic, renal, and other systemic impacts of PsA is essential.

Biologic therapies are key to preventing disease progression. The most broadly targeted are the TNF-alpha inhibitors, which are commonly recommended as first-line therapy in moderate to severe PsA or in patients with radiographic damage. The interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitors ixekizumab and secukinumab and the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab have targets downstream of TNF-alpha. Treatment options also include oral small molecule inhibitors of phosphodiesterase 4 (apremilast) or Janus kinase (tofacitinib, upadacitinib). Recognition of the role of IL-23 as a key cytokine in PsA development through promotion of Th17 differentiation has led to availability of drugs specifically targeting IL-23(p19) (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab). All have been studied, but only guselkumab and risankizumab currently are approved for treatment of PsA. Each class of drugs has specific benefits and risks, which should be discussed with patients before treatment initiation. Patient comorbidities should also be considered in choosing treatment.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an immune-mediated arthritis that is almost always associated with plaque psoriasis. PsA is diagnosed in about 20% of patients with plaque psoriasis, and, in most patients, a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis precedes PsA development. However, in this patient, PsA appears to have become symptomatic at about the same time as the skin symptoms behind his ears, which is consistent with studies showing that PsA co-occurs with plaque psoriasis in 15% of patients and precedes plaque psoriasis diagnosis in 17% of patients. Environmental risk factors for PsA in genetically susceptible patients with plaque psoriasis include joint trauma, streptococcal infection, and certain antibiotics. Smoking appears to have a protective effect in PsA. PsA is more highly associated with severe plaque psoriasis than with mild plaque psoriasis.

PsA has a heterogeneous presentation, which may challenge diagnosis. It is classified by the degree of joint involvement as oligoarticular (four or fewer joints) or polyarticular (five or more joints). Radiographically, there are five main types of PsA, one of which is predominant involvement of the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) joints — the form seen in this patient. The other four types of PsA are symmetrical peripheral polyarthritis, asymmetrical mono- or oligoarthritis, axial spondyloarthropathy, and arthritis mutilans. DIP joint involvement with proliferative bone changes suggests a diagnosis of PsA over rheumatoid arthritis.

PsA is diagnosed using radiography, skin biopsy of affected skin areas, and complete blood and metabolic assessments. With advanced PsA, radiographs typically reveal bone destruction and disease-related bone formation (juxta-articular bone formation), resulting in erosions, joint destruction, and joint-space narrowing. Juxta-articular bone formation (presenting poorly defined ossification adjacent to the joint margin) is often the earliest radiographic clue before erosions may occur. Enthesitis in multiple entheses is typical of PsA vs osteoarthritis or mechanical injury. There are no specific tests to confirm PsA. Patients with PsA usually are rheumatoid factor negative. Inflammatory biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, are elevated in about 40% of patients with PsA.

In addition to plaques, extra-articular manifestations of PsA may include nail changes and chronic bilateral ocular disease. PsA is an articular manifestation of psoriasis but is still a systemic disease with deleterious effects on cardiometabolic factors; increased mortality with myocardial infarction; and possible involvement of other immune-mediated diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, that share a common pathway of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha overexpression.

Early treatment with disease-modifying drugs plus nonpharmacologic interventions is crucial to minimizing disability progression and optimizing patients' quality of life. Nonpharmacologic interventions include physical and occupational therapy and exercise. Symptomatic therapies (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or steroids) can be used to relieve mild symptoms. Assessment for cardiometabolic, renal, and other systemic impacts of PsA is essential.

Biologic therapies are key to preventing disease progression. The most broadly targeted are the TNF-alpha inhibitors, which are commonly recommended as first-line therapy in moderate to severe PsA or in patients with radiographic damage. The interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitors ixekizumab and secukinumab and the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab have targets downstream of TNF-alpha. Treatment options also include oral small molecule inhibitors of phosphodiesterase 4 (apremilast) or Janus kinase (tofacitinib, upadacitinib). Recognition of the role of IL-23 as a key cytokine in PsA development through promotion of Th17 differentiation has led to availability of drugs specifically targeting IL-23(p19) (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab). All have been studied, but only guselkumab and risankizumab currently are approved for treatment of PsA. Each class of drugs has specific benefits and risks, which should be discussed with patients before treatment initiation. Patient comorbidities should also be considered in choosing treatment.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an immune-mediated arthritis that is almost always associated with plaque psoriasis. PsA is diagnosed in about 20% of patients with plaque psoriasis, and, in most patients, a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis precedes PsA development. However, in this patient, PsA appears to have become symptomatic at about the same time as the skin symptoms behind his ears, which is consistent with studies showing that PsA co-occurs with plaque psoriasis in 15% of patients and precedes plaque psoriasis diagnosis in 17% of patients. Environmental risk factors for PsA in genetically susceptible patients with plaque psoriasis include joint trauma, streptococcal infection, and certain antibiotics. Smoking appears to have a protective effect in PsA. PsA is more highly associated with severe plaque psoriasis than with mild plaque psoriasis.

PsA has a heterogeneous presentation, which may challenge diagnosis. It is classified by the degree of joint involvement as oligoarticular (four or fewer joints) or polyarticular (five or more joints). Radiographically, there are five main types of PsA, one of which is predominant involvement of the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) joints — the form seen in this patient. The other four types of PsA are symmetrical peripheral polyarthritis, asymmetrical mono- or oligoarthritis, axial spondyloarthropathy, and arthritis mutilans. DIP joint involvement with proliferative bone changes suggests a diagnosis of PsA over rheumatoid arthritis.

PsA is diagnosed using radiography, skin biopsy of affected skin areas, and complete blood and metabolic assessments. With advanced PsA, radiographs typically reveal bone destruction and disease-related bone formation (juxta-articular bone formation), resulting in erosions, joint destruction, and joint-space narrowing. Juxta-articular bone formation (presenting poorly defined ossification adjacent to the joint margin) is often the earliest radiographic clue before erosions may occur. Enthesitis in multiple entheses is typical of PsA vs osteoarthritis or mechanical injury. There are no specific tests to confirm PsA. Patients with PsA usually are rheumatoid factor negative. Inflammatory biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, are elevated in about 40% of patients with PsA.

In addition to plaques, extra-articular manifestations of PsA may include nail changes and chronic bilateral ocular disease. PsA is an articular manifestation of psoriasis but is still a systemic disease with deleterious effects on cardiometabolic factors; increased mortality with myocardial infarction; and possible involvement of other immune-mediated diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, that share a common pathway of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha overexpression.

Early treatment with disease-modifying drugs plus nonpharmacologic interventions is crucial to minimizing disability progression and optimizing patients' quality of life. Nonpharmacologic interventions include physical and occupational therapy and exercise. Symptomatic therapies (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or steroids) can be used to relieve mild symptoms. Assessment for cardiometabolic, renal, and other systemic impacts of PsA is essential.

Biologic therapies are key to preventing disease progression. The most broadly targeted are the TNF-alpha inhibitors, which are commonly recommended as first-line therapy in moderate to severe PsA or in patients with radiographic damage. The interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitors ixekizumab and secukinumab and the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab have targets downstream of TNF-alpha. Treatment options also include oral small molecule inhibitors of phosphodiesterase 4 (apremilast) or Janus kinase (tofacitinib, upadacitinib). Recognition of the role of IL-23 as a key cytokine in PsA development through promotion of Th17 differentiation has led to availability of drugs specifically targeting IL-23(p19) (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab). All have been studied, but only guselkumab and risankizumab currently are approved for treatment of PsA. Each class of drugs has specific benefits and risks, which should be discussed with patients before treatment initiation. Patient comorbidities should also be considered in choosing treatment.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 58-year-old man presents with pain in fingers of several months' duration, which is moderately relieved with over-the-counter naproxen. He is concerned about "crooked" fingers and is worried that his work will be affected. He is overweight (BMI, 28.8), hypertensive, hypercholesterolemic, and a nonsmoker. The patient also reports a 6-month history of itchy "scalp" behind the ears, not relieved with dandruff shampoos. Physical exam reveals advanced deformity in index and middle fingers of both hands and no evident deformity in the wrists or metacarpophalangeal joints. Nails are pitted and discolored. Scalp behind ears shows well-demarcated, scaly patches. Lab work, radiography, and biopsy of the retroauricular area are ordered.

PsA Complications

History of plaque psoriasis

The patient's history of psoriasis, along with his current skin and scalp plaque flares, symmetrical joint symptomatology, laboratory studies, and x-rays, suggest a diagnosis of symmetrical psoriatic arthritis (PsA). The rheumatologist considers ordering additional imaging to assess for subclinical enthesitis and dactylitis, and discusses treatment next steps with the patient, given inadequate control with a TNF inhibitor.

Symmetrical polyarthritis is one of the most common types of PsA and involves five or more joints in the hands, wrists, ankles, and/or feet. Among patients with PsA, 60% to 80% experience plaque psoriasis before joint-symptom onset; time to joint-symptom onset in these patients typically occurs within 10 years of a plaque psoriasis diagnosis. Involvement of DIP joints differentiates PsA from rheumatoid arthritis, as does the absence of subcutaneous nodules and a negative result for rheumatoid factor. About 30% of all people with plaque psoriasis will develop PsA, which affects an estimated 1 million people in the United States annually. Symptoms typically appear between the ages of 35 and 55 years; women are more likely than men to develop symmetrical PsA.

There are no specific diagnostic tests for PsA. Rheumatologists generally use the assessment known as the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis, (CASPAR), which can help reveal established inflammatory articular disease through a point system based on the presence/absence of various factors. On laboratory studies, the most common characteristic abnormalities of PsA are elevated ESR and CRP levels and negative rheumatoid factor in most patients. Other abnormalities that may be present in patients with PsA include elevated serum uric acid concentration and serum immunoglobulin A, and reduced levels of circulating immune complexes. Physicians also use imaging studies, such as radiography, ultrasonography, and MRI, to help differentiate PsA from other articular diseases.

While the pathogenesis of PsA remains unclear, research has shown that disease development is associated with a complex interplay of immune-mediated inflammatory responses; genetic and environmental factors may also be involved. In addition, patients with PsA are more likely to have a high risk for comorbidities, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular events, compared with the general population.

When patients with PsA experience both skin and joint symptoms, a multidisciplinary approach to care is advised. Multidisciplinary teams play a key role in educating patients about their treatment plans and managing their PsA symptoms. The teams also help patients determine the best approaches to exercise to help maintain current joint function, as well as helpful adjustments in daily activities that will make it easier to accommodate their disease.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, whether self-prescribed or prescribed by a physician, are a common initial treatment to manage joint symptoms of PsA. Current American College of Rheumatology treatment guidelines, however, encourage early treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) because approximately 40% of patients with PsA develop erosive and deforming arthritis. Several DMARDs are available, including older drugs like methotrexate, as well as newer biologic agents, such as TNF inhibitors, interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitors, IL-12/23 inhibitors, and Janus kinase inhibitors. In addition, guidelines recommend early and customized physical therapy and rehabilitation approaches for patients with PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient's history of psoriasis, along with his current skin and scalp plaque flares, symmetrical joint symptomatology, laboratory studies, and x-rays, suggest a diagnosis of symmetrical psoriatic arthritis (PsA). The rheumatologist considers ordering additional imaging to assess for subclinical enthesitis and dactylitis, and discusses treatment next steps with the patient, given inadequate control with a TNF inhibitor.

Symmetrical polyarthritis is one of the most common types of PsA and involves five or more joints in the hands, wrists, ankles, and/or feet. Among patients with PsA, 60% to 80% experience plaque psoriasis before joint-symptom onset; time to joint-symptom onset in these patients typically occurs within 10 years of a plaque psoriasis diagnosis. Involvement of DIP joints differentiates PsA from rheumatoid arthritis, as does the absence of subcutaneous nodules and a negative result for rheumatoid factor. About 30% of all people with plaque psoriasis will develop PsA, which affects an estimated 1 million people in the United States annually. Symptoms typically appear between the ages of 35 and 55 years; women are more likely than men to develop symmetrical PsA.

There are no specific diagnostic tests for PsA. Rheumatologists generally use the assessment known as the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis, (CASPAR), which can help reveal established inflammatory articular disease through a point system based on the presence/absence of various factors. On laboratory studies, the most common characteristic abnormalities of PsA are elevated ESR and CRP levels and negative rheumatoid factor in most patients. Other abnormalities that may be present in patients with PsA include elevated serum uric acid concentration and serum immunoglobulin A, and reduced levels of circulating immune complexes. Physicians also use imaging studies, such as radiography, ultrasonography, and MRI, to help differentiate PsA from other articular diseases.

While the pathogenesis of PsA remains unclear, research has shown that disease development is associated with a complex interplay of immune-mediated inflammatory responses; genetic and environmental factors may also be involved. In addition, patients with PsA are more likely to have a high risk for comorbidities, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular events, compared with the general population.

When patients with PsA experience both skin and joint symptoms, a multidisciplinary approach to care is advised. Multidisciplinary teams play a key role in educating patients about their treatment plans and managing their PsA symptoms. The teams also help patients determine the best approaches to exercise to help maintain current joint function, as well as helpful adjustments in daily activities that will make it easier to accommodate their disease.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, whether self-prescribed or prescribed by a physician, are a common initial treatment to manage joint symptoms of PsA. Current American College of Rheumatology treatment guidelines, however, encourage early treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) because approximately 40% of patients with PsA develop erosive and deforming arthritis. Several DMARDs are available, including older drugs like methotrexate, as well as newer biologic agents, such as TNF inhibitors, interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitors, IL-12/23 inhibitors, and Janus kinase inhibitors. In addition, guidelines recommend early and customized physical therapy and rehabilitation approaches for patients with PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient's history of psoriasis, along with his current skin and scalp plaque flares, symmetrical joint symptomatology, laboratory studies, and x-rays, suggest a diagnosis of symmetrical psoriatic arthritis (PsA). The rheumatologist considers ordering additional imaging to assess for subclinical enthesitis and dactylitis, and discusses treatment next steps with the patient, given inadequate control with a TNF inhibitor.

Symmetrical polyarthritis is one of the most common types of PsA and involves five or more joints in the hands, wrists, ankles, and/or feet. Among patients with PsA, 60% to 80% experience plaque psoriasis before joint-symptom onset; time to joint-symptom onset in these patients typically occurs within 10 years of a plaque psoriasis diagnosis. Involvement of DIP joints differentiates PsA from rheumatoid arthritis, as does the absence of subcutaneous nodules and a negative result for rheumatoid factor. About 30% of all people with plaque psoriasis will develop PsA, which affects an estimated 1 million people in the United States annually. Symptoms typically appear between the ages of 35 and 55 years; women are more likely than men to develop symmetrical PsA.

There are no specific diagnostic tests for PsA. Rheumatologists generally use the assessment known as the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis, (CASPAR), which can help reveal established inflammatory articular disease through a point system based on the presence/absence of various factors. On laboratory studies, the most common characteristic abnormalities of PsA are elevated ESR and CRP levels and negative rheumatoid factor in most patients. Other abnormalities that may be present in patients with PsA include elevated serum uric acid concentration and serum immunoglobulin A, and reduced levels of circulating immune complexes. Physicians also use imaging studies, such as radiography, ultrasonography, and MRI, to help differentiate PsA from other articular diseases.

While the pathogenesis of PsA remains unclear, research has shown that disease development is associated with a complex interplay of immune-mediated inflammatory responses; genetic and environmental factors may also be involved. In addition, patients with PsA are more likely to have a high risk for comorbidities, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular events, compared with the general population.

When patients with PsA experience both skin and joint symptoms, a multidisciplinary approach to care is advised. Multidisciplinary teams play a key role in educating patients about their treatment plans and managing their PsA symptoms. The teams also help patients determine the best approaches to exercise to help maintain current joint function, as well as helpful adjustments in daily activities that will make it easier to accommodate their disease.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, whether self-prescribed or prescribed by a physician, are a common initial treatment to manage joint symptoms of PsA. Current American College of Rheumatology treatment guidelines, however, encourage early treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) because approximately 40% of patients with PsA develop erosive and deforming arthritis. Several DMARDs are available, including older drugs like methotrexate, as well as newer biologic agents, such as TNF inhibitors, interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitors, IL-12/23 inhibitors, and Janus kinase inhibitors. In addition, guidelines recommend early and customized physical therapy and rehabilitation approaches for patients with PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 43-year-old White man with a 5-year history of plaque psoriasis presents to a rheumatologist on referral from his dermatologist. He had been taking a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, which had controlled his skin and scalp plaques since diagnosis. Lately, however, some of the plaques have begun to flare up, and the patient reports new tenderness and swelling in three of the same joints on his left and right hands and extensive fatigue. Additional medical history includes type 2 diabetes, which was diagnosed 3 years ago; soon thereafter, he started taking metformin with consistent disease control. The rheumatologist conducts a physical exam and orders laboratory studies and x-rays. Results of the laboratory studies reveal elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Radiographs reveal joint-space narrowing in several distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints in both hands, with mild erosive disease.

PsA Differential Diagnosis

Intermittent pain and stiffness

The history and findings in this case are consistent with a diagnosis of psoriatic spondylitis.

Psoriatic spondylitis is a form of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) that affects the spine and the joints in the pelvis (axial involvement). PsA is a chronic, heterogeneous condition that affects approximately 25%-30% of patients with psoriasis, particularly those with severe psoriasis or nail or scalp involvement. It is characterized by musculoskeletal inflammation (arthritis, enthesitis, spondylitis, and dactylitis). PsA is a spondyloarthritis that can be found either in the peripheral or axial skeleton. If not treated, it may result in permanent joint damage and loss of function.

Patients with PsA may present with nail and skin changes, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), either alone or in combination. Common symptoms of axial involvement in PsA include morning back/neck stiffness that lasts longer than 30 minutes, neck or back pain that improves with activity and worsens after prolonged inactivity, and diminished mobility. PsA affects men and women equally, and typically develops when patients are between 30 and 50 years of age. As with psoriasis, PsA is associated with numerous comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression, uveitis, and anxiety.

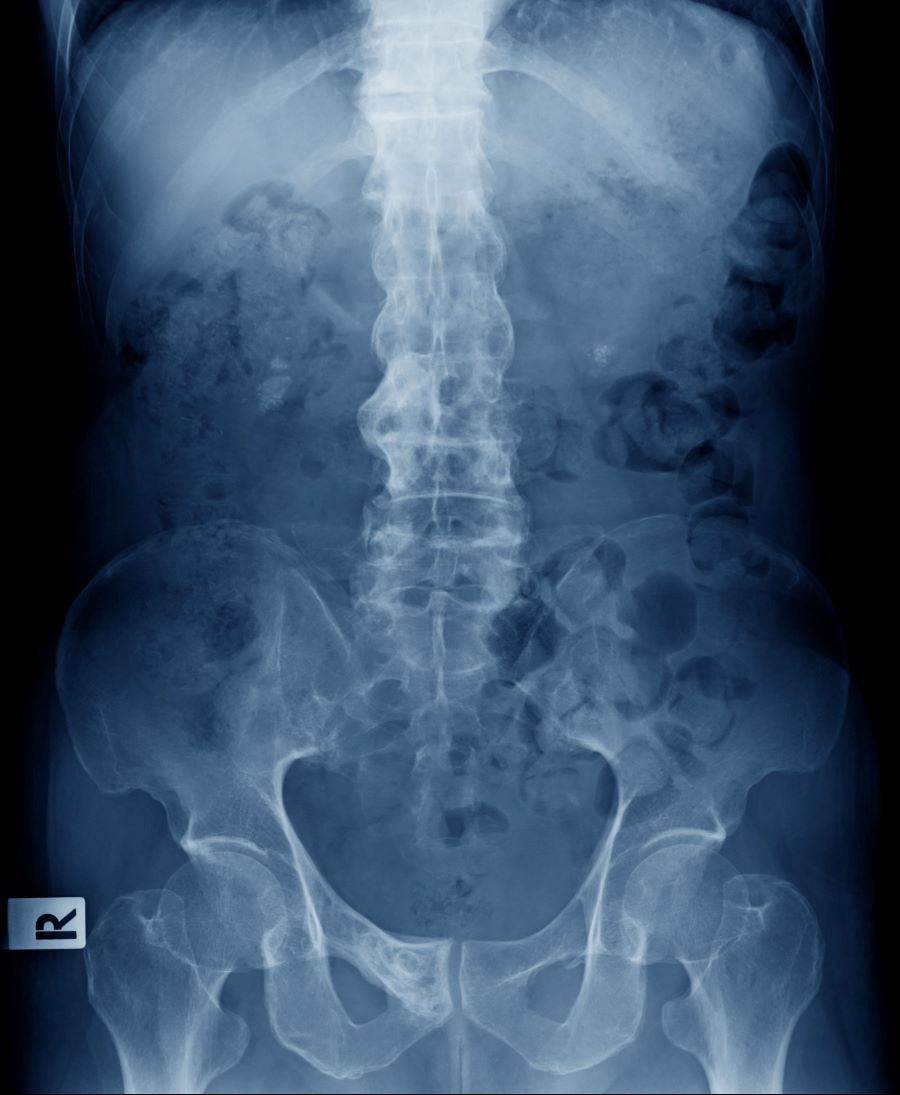

The diagnosis of psoriatic spondylitis is confirmed by physical examination and imaging. Axial PsA characteristics, including sacroiliitis and spondylitis, are distinguished by the development of syndesmophytes (ie, ossification of the annulus fibrosus). Useful imaging tools for evaluating patients with PsA include plain radiography, CT, ultrasound, and MRI. Although MRI and ultrasound may be more sensitive than plain radiography for detecting early joint inflammation and damage and axial changes, including sacroiliitis, they are not mandatory for a diagnosis of PsA to be made.

International guidelines have been developed by the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA), the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR), and the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society to guide the treatment of axial PsA. The goals of treatment include minimizing pain, stiffness, and fatigue; improving and preserving spinal flexibility and posture; improving functional capacity; and maintaining the ability to work, with a target of remission or minimal/low disease activity.

Treatment options for symptomatic relief include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and sacroiliac joint injections with glucocorticoids for mild disease; long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is not recommended. If patients remain symptomatic or have erosive disease or other indications of high disease activity, guidelines recommend initiation of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor (eg, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol). Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (eg, methotrexate) are not routinely prescribed for patients with axial disease because they have not been shown to be effective. In patients with significant skin involvement, treatment with interleukin-17A inhibitors may be preferred to TNF inhibitors.

If patients have an inadequate response to a first trial of a TNF inhibitor, guidelines recommend trying a second TNF inhibitor before switching to a different class of biologic. For patients who do not respond to TNF inhibitors, a Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib) may be considered. Additionally, nonpharmacologic therapies (eg, exercise, physical therapy, massage therapy, occupational therapy, acupuncture) are recommended for all patients with active PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are consistent with a diagnosis of psoriatic spondylitis.

Psoriatic spondylitis is a form of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) that affects the spine and the joints in the pelvis (axial involvement). PsA is a chronic, heterogeneous condition that affects approximately 25%-30% of patients with psoriasis, particularly those with severe psoriasis or nail or scalp involvement. It is characterized by musculoskeletal inflammation (arthritis, enthesitis, spondylitis, and dactylitis). PsA is a spondyloarthritis that can be found either in the peripheral or axial skeleton. If not treated, it may result in permanent joint damage and loss of function.

Patients with PsA may present with nail and skin changes, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), either alone or in combination. Common symptoms of axial involvement in PsA include morning back/neck stiffness that lasts longer than 30 minutes, neck or back pain that improves with activity and worsens after prolonged inactivity, and diminished mobility. PsA affects men and women equally, and typically develops when patients are between 30 and 50 years of age. As with psoriasis, PsA is associated with numerous comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression, uveitis, and anxiety.

The diagnosis of psoriatic spondylitis is confirmed by physical examination and imaging. Axial PsA characteristics, including sacroiliitis and spondylitis, are distinguished by the development of syndesmophytes (ie, ossification of the annulus fibrosus). Useful imaging tools for evaluating patients with PsA include plain radiography, CT, ultrasound, and MRI. Although MRI and ultrasound may be more sensitive than plain radiography for detecting early joint inflammation and damage and axial changes, including sacroiliitis, they are not mandatory for a diagnosis of PsA to be made.

International guidelines have been developed by the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA), the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR), and the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society to guide the treatment of axial PsA. The goals of treatment include minimizing pain, stiffness, and fatigue; improving and preserving spinal flexibility and posture; improving functional capacity; and maintaining the ability to work, with a target of remission or minimal/low disease activity.

Treatment options for symptomatic relief include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and sacroiliac joint injections with glucocorticoids for mild disease; long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is not recommended. If patients remain symptomatic or have erosive disease or other indications of high disease activity, guidelines recommend initiation of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor (eg, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol). Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (eg, methotrexate) are not routinely prescribed for patients with axial disease because they have not been shown to be effective. In patients with significant skin involvement, treatment with interleukin-17A inhibitors may be preferred to TNF inhibitors.

If patients have an inadequate response to a first trial of a TNF inhibitor, guidelines recommend trying a second TNF inhibitor before switching to a different class of biologic. For patients who do not respond to TNF inhibitors, a Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib) may be considered. Additionally, nonpharmacologic therapies (eg, exercise, physical therapy, massage therapy, occupational therapy, acupuncture) are recommended for all patients with active PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are consistent with a diagnosis of psoriatic spondylitis.

Psoriatic spondylitis is a form of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) that affects the spine and the joints in the pelvis (axial involvement). PsA is a chronic, heterogeneous condition that affects approximately 25%-30% of patients with psoriasis, particularly those with severe psoriasis or nail or scalp involvement. It is characterized by musculoskeletal inflammation (arthritis, enthesitis, spondylitis, and dactylitis). PsA is a spondyloarthritis that can be found either in the peripheral or axial skeleton. If not treated, it may result in permanent joint damage and loss of function.

Patients with PsA may present with nail and skin changes, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), either alone or in combination. Common symptoms of axial involvement in PsA include morning back/neck stiffness that lasts longer than 30 minutes, neck or back pain that improves with activity and worsens after prolonged inactivity, and diminished mobility. PsA affects men and women equally, and typically develops when patients are between 30 and 50 years of age. As with psoriasis, PsA is associated with numerous comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression, uveitis, and anxiety.

The diagnosis of psoriatic spondylitis is confirmed by physical examination and imaging. Axial PsA characteristics, including sacroiliitis and spondylitis, are distinguished by the development of syndesmophytes (ie, ossification of the annulus fibrosus). Useful imaging tools for evaluating patients with PsA include plain radiography, CT, ultrasound, and MRI. Although MRI and ultrasound may be more sensitive than plain radiography for detecting early joint inflammation and damage and axial changes, including sacroiliitis, they are not mandatory for a diagnosis of PsA to be made.

International guidelines have been developed by the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA), the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR), and the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society to guide the treatment of axial PsA. The goals of treatment include minimizing pain, stiffness, and fatigue; improving and preserving spinal flexibility and posture; improving functional capacity; and maintaining the ability to work, with a target of remission or minimal/low disease activity.

Treatment options for symptomatic relief include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and sacroiliac joint injections with glucocorticoids for mild disease; long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is not recommended. If patients remain symptomatic or have erosive disease or other indications of high disease activity, guidelines recommend initiation of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor (eg, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol). Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (eg, methotrexate) are not routinely prescribed for patients with axial disease because they have not been shown to be effective. In patients with significant skin involvement, treatment with interleukin-17A inhibitors may be preferred to TNF inhibitors.

If patients have an inadequate response to a first trial of a TNF inhibitor, guidelines recommend trying a second TNF inhibitor before switching to a different class of biologic. For patients who do not respond to TNF inhibitors, a Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib) may be considered. Additionally, nonpharmacologic therapies (eg, exercise, physical therapy, massage therapy, occupational therapy, acupuncture) are recommended for all patients with active PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 41-year-old man with a 5-year history of moderate to severe scalp psoriasis presents with complaints of intermittent pain and stiffness in his left hip and lower back of approximately 6 months' duration. The patient states that his back pain has been severe enough to wake him up on several occasions. Treatment with over-the-counter ibuprofen is moderately effective at relieving his pain. He also reports morning back stiffness that improves with motion, usually within an hour of awakening. The patient reports no fever, pain, swelling, or worsening of his scalp psoriasis. He is not aware of any injury or other triggering factor for his back pain. He takes an over-the-counter multivitamin daily and treats his scalp psoriasis with fluocinolone acetonide 0.01% oil. The patient is 5 ft 9 in and weighs 176 lb (BMI 26).

Physical examination reveals tenderness in the lumbar spine and associated decreased range of motion, as well as psoriatic plaques on the scalp. Vital signs are within normal ranges. Pertinent laboratory findings include erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 19 mm/h and C-reactive protein of 10 mg/L. Rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody were negative. Radiographic findings include sacroiliitis and bulky nonmarginal syndesmophytes.