User login

Increasing fatigue and dry cough

This patient's clinical presentation is consistent with a diagnosis of superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), secondary to SCLC.

SCLC is an aggressive, poorly differentiated, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma that accounts for approximately 13%-15% of all new lung cancer cases in the United States. SCLC has a propensity for early dissemination; as such, 80%-85% of patients are diagnosed with extensive disease (ES-SCLC). This is common in heavy smokers. Most SCLC tumors are found in hilar or perihilar areas; <5% present in peripheral locations. In many cases, invasion into the peribronchial tissue and lymph node can be clearly identified, with a typical circumferential spread along the submucosa of the bronchi.

Up to 10% of patients with SCLC develop SVCS, which comprises an array of signs and symptoms that result from the obstruction of blood flow through the thin-walled superior vena cava. Clinical symptoms may include cough, dyspnea, and orthopnea; facial edema and plethora, upper extremity swelling, and venous distension of the chest wall and neck are the most commonly encountered signs. Most cases of SVCS occur in patients with mediastinal tumors, although noncancerous causes (eg, thrombosis and fibrosing mediastinitis) can also give rise to it. The diagnosis of SVCS is usually made clinically and then confirmed with imaging (chest radiography, contrast-enhanced CT, duplex ultrasound, conventional venography, and/or magnetic resonance venography).

Though it was traditionally considered a virtual emergency, patients seldom experience life-threatening complications from SVCS. The goals of treatment are to alleviate the symptoms of SVC obstruction and treat the underlying disease process. Treatment approaches include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, open surgery, and endovenous recanalization; however, patients with clinical SVCS often achieve significant improvement in symptoms from conservative treatment approaches, including elevation of the head of the bed and supplemental oxygen. Systemic chemotherapy can effectively relieve the symptoms of SVCS obstruction, typically within 1-2 weeks of treatment initiation. Up to 80% of patients with SCLC and non-Hodgkin lymphoma may experience complete relief of SVCS symptoms with chemotherapy treatment.

Radiation therapy was once considered the standard approach to the management of SVCS in patients with cancer; however, endovenous recanalization can alleviate symptoms faster than radiation therapy — usually within 72 hours, whereas radiation therapy can take up to 2 weeks to provide relief. Endovascular therapy is also associated with higher efficacy rates than is radiation therapy.

Open surgery plays a limited role in the management of SVC obstruction, although it may be the best approach in select cases.

In cases involving brain edema, decreased cardiac output, or upper airway edema, emergency treatment is indicated.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation is consistent with a diagnosis of superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), secondary to SCLC.

SCLC is an aggressive, poorly differentiated, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma that accounts for approximately 13%-15% of all new lung cancer cases in the United States. SCLC has a propensity for early dissemination; as such, 80%-85% of patients are diagnosed with extensive disease (ES-SCLC). This is common in heavy smokers. Most SCLC tumors are found in hilar or perihilar areas; <5% present in peripheral locations. In many cases, invasion into the peribronchial tissue and lymph node can be clearly identified, with a typical circumferential spread along the submucosa of the bronchi.

Up to 10% of patients with SCLC develop SVCS, which comprises an array of signs and symptoms that result from the obstruction of blood flow through the thin-walled superior vena cava. Clinical symptoms may include cough, dyspnea, and orthopnea; facial edema and plethora, upper extremity swelling, and venous distension of the chest wall and neck are the most commonly encountered signs. Most cases of SVCS occur in patients with mediastinal tumors, although noncancerous causes (eg, thrombosis and fibrosing mediastinitis) can also give rise to it. The diagnosis of SVCS is usually made clinically and then confirmed with imaging (chest radiography, contrast-enhanced CT, duplex ultrasound, conventional venography, and/or magnetic resonance venography).

Though it was traditionally considered a virtual emergency, patients seldom experience life-threatening complications from SVCS. The goals of treatment are to alleviate the symptoms of SVC obstruction and treat the underlying disease process. Treatment approaches include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, open surgery, and endovenous recanalization; however, patients with clinical SVCS often achieve significant improvement in symptoms from conservative treatment approaches, including elevation of the head of the bed and supplemental oxygen. Systemic chemotherapy can effectively relieve the symptoms of SVCS obstruction, typically within 1-2 weeks of treatment initiation. Up to 80% of patients with SCLC and non-Hodgkin lymphoma may experience complete relief of SVCS symptoms with chemotherapy treatment.

Radiation therapy was once considered the standard approach to the management of SVCS in patients with cancer; however, endovenous recanalization can alleviate symptoms faster than radiation therapy — usually within 72 hours, whereas radiation therapy can take up to 2 weeks to provide relief. Endovascular therapy is also associated with higher efficacy rates than is radiation therapy.

Open surgery plays a limited role in the management of SVC obstruction, although it may be the best approach in select cases.

In cases involving brain edema, decreased cardiac output, or upper airway edema, emergency treatment is indicated.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation is consistent with a diagnosis of superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), secondary to SCLC.

SCLC is an aggressive, poorly differentiated, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma that accounts for approximately 13%-15% of all new lung cancer cases in the United States. SCLC has a propensity for early dissemination; as such, 80%-85% of patients are diagnosed with extensive disease (ES-SCLC). This is common in heavy smokers. Most SCLC tumors are found in hilar or perihilar areas; <5% present in peripheral locations. In many cases, invasion into the peribronchial tissue and lymph node can be clearly identified, with a typical circumferential spread along the submucosa of the bronchi.

Up to 10% of patients with SCLC develop SVCS, which comprises an array of signs and symptoms that result from the obstruction of blood flow through the thin-walled superior vena cava. Clinical symptoms may include cough, dyspnea, and orthopnea; facial edema and plethora, upper extremity swelling, and venous distension of the chest wall and neck are the most commonly encountered signs. Most cases of SVCS occur in patients with mediastinal tumors, although noncancerous causes (eg, thrombosis and fibrosing mediastinitis) can also give rise to it. The diagnosis of SVCS is usually made clinically and then confirmed with imaging (chest radiography, contrast-enhanced CT, duplex ultrasound, conventional venography, and/or magnetic resonance venography).

Though it was traditionally considered a virtual emergency, patients seldom experience life-threatening complications from SVCS. The goals of treatment are to alleviate the symptoms of SVC obstruction and treat the underlying disease process. Treatment approaches include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, open surgery, and endovenous recanalization; however, patients with clinical SVCS often achieve significant improvement in symptoms from conservative treatment approaches, including elevation of the head of the bed and supplemental oxygen. Systemic chemotherapy can effectively relieve the symptoms of SVCS obstruction, typically within 1-2 weeks of treatment initiation. Up to 80% of patients with SCLC and non-Hodgkin lymphoma may experience complete relief of SVCS symptoms with chemotherapy treatment.

Radiation therapy was once considered the standard approach to the management of SVCS in patients with cancer; however, endovenous recanalization can alleviate symptoms faster than radiation therapy — usually within 72 hours, whereas radiation therapy can take up to 2 weeks to provide relief. Endovascular therapy is also associated with higher efficacy rates than is radiation therapy.

Open surgery plays a limited role in the management of SVC obstruction, although it may be the best approach in select cases.

In cases involving brain edema, decreased cardiac output, or upper airway edema, emergency treatment is indicated.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

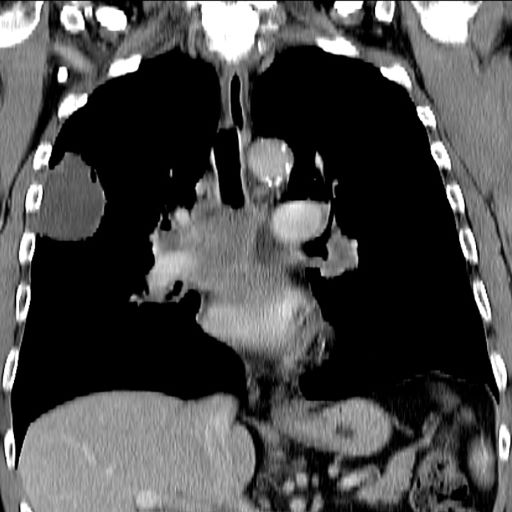

A 66-year-old African American man was diagnosed with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) after the discovery of an endobronchial tumor on bronchoscopy. A biopsy of the tumor was positive for SCLC and CT revealed multiple pulmonary nodules and extensive mediastinal nodal metastases. The patient completed his first cycle of carboplatin-based chemotherapy about 1 month ago. At today's visit, he presents with complaints of worsening symptoms over the past week or so; specifically, he reports increasing fatigue and shortness of breath, a dry cough, light-headedness, difficulty swallowing, and facial swelling. Physical examination reveals facial edema and venous distension of the neck and chest wall; blood pressure is 140/70 mm Hg, respiratory rate is 19 breaths/min, and pulse is 84 beats/min. The patient has a 45-pack-year smoking history and reports having two or three alcoholic drinks per day. His previous medical history is positive for hypertension, which is treated with enalapril 20 mg/day and metoprolol 200 mg/day. Complete blood cell count findings are all within normal range.

SCLC Guidelines

SCLC Treatment

Persistent dry cough

On the basis of the patient's presentation, history, and imaging results, the likely diagnosis is metastatic small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Most patients with SCLC present with hematogenous metastases; only about one third present with limited disease confined to the chest that is amenable to multimodal therapy. Patients with SCLC often present with symptoms of widespread metastases, including weight loss, bone pain, and neurologic compromise. It is uncommon for patients to present with a solitary peripheral nodule. In earlier stages, the differential diagnosis of SCLC spans other neuroendocrine lung tumors and NSCLC, in particular, basaloid carcinoma, extrapulmonary small cell tumors, and lymphoma.

Because the concentration of circulating tumor cells in SCLC is among the highest of any solid tumor, SCLC is characterized by a rapid doubling time, high growth fraction, and early development of widespread metastases. It is likely for this reason that CT screening does not seem effective in detecting early-stage SCLC. Common sites of SCLC metastasis are the contralateral lung, the brain, liver, adrenal glands, and bone. Most cases of SCLC are caused by smoking.

Metastatic spread is often evident on radiologic exam, sometimes showing pleural and pericardial effusions. In general, workup for SCLC includes imaging (contrast-enhanced CT or F-FDG PET–CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and brain MRI with contrast), blood tests (cell count, liver and kidney function, and lactate dehydrogenase), and ECG. Biopsies are generally procured by bronchoscopy with or without endobronchial ultrasonography; if accessible, a biopsy of a distal metastatic site may be obtained. Diagnosis of SCLC is confirmed by histopathologic examination via cytology.

Patients with extensive-stage SCLC are typically treated with systemic chemotherapy with or without immunotherapy. In the early stages, SCLC is very responsive to cytotoxic therapies, with response rates over 60% even in patients with metastatic disease. Until recently, the only second-line therapy for recurrent metastatic SCLC was the topoisomerase I inhibitor topotecan. However, lurbinectedin was granted accelerated approval for second-line therapy after demonstrating a 35% response rate in a single-arm phase 2 study of 105 patients. In addition, the anti–programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibodies nivolumab and pembrolizumab were granted accelerated approval for third-line use. Finally, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines note that participation in clinical trials should be strongly encouraged for all patients with SCLC.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation, history, and imaging results, the likely diagnosis is metastatic small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Most patients with SCLC present with hematogenous metastases; only about one third present with limited disease confined to the chest that is amenable to multimodal therapy. Patients with SCLC often present with symptoms of widespread metastases, including weight loss, bone pain, and neurologic compromise. It is uncommon for patients to present with a solitary peripheral nodule. In earlier stages, the differential diagnosis of SCLC spans other neuroendocrine lung tumors and NSCLC, in particular, basaloid carcinoma, extrapulmonary small cell tumors, and lymphoma.

Because the concentration of circulating tumor cells in SCLC is among the highest of any solid tumor, SCLC is characterized by a rapid doubling time, high growth fraction, and early development of widespread metastases. It is likely for this reason that CT screening does not seem effective in detecting early-stage SCLC. Common sites of SCLC metastasis are the contralateral lung, the brain, liver, adrenal glands, and bone. Most cases of SCLC are caused by smoking.

Metastatic spread is often evident on radiologic exam, sometimes showing pleural and pericardial effusions. In general, workup for SCLC includes imaging (contrast-enhanced CT or F-FDG PET–CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and brain MRI with contrast), blood tests (cell count, liver and kidney function, and lactate dehydrogenase), and ECG. Biopsies are generally procured by bronchoscopy with or without endobronchial ultrasonography; if accessible, a biopsy of a distal metastatic site may be obtained. Diagnosis of SCLC is confirmed by histopathologic examination via cytology.

Patients with extensive-stage SCLC are typically treated with systemic chemotherapy with or without immunotherapy. In the early stages, SCLC is very responsive to cytotoxic therapies, with response rates over 60% even in patients with metastatic disease. Until recently, the only second-line therapy for recurrent metastatic SCLC was the topoisomerase I inhibitor topotecan. However, lurbinectedin was granted accelerated approval for second-line therapy after demonstrating a 35% response rate in a single-arm phase 2 study of 105 patients. In addition, the anti–programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibodies nivolumab and pembrolizumab were granted accelerated approval for third-line use. Finally, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines note that participation in clinical trials should be strongly encouraged for all patients with SCLC.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation, history, and imaging results, the likely diagnosis is metastatic small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Most patients with SCLC present with hematogenous metastases; only about one third present with limited disease confined to the chest that is amenable to multimodal therapy. Patients with SCLC often present with symptoms of widespread metastases, including weight loss, bone pain, and neurologic compromise. It is uncommon for patients to present with a solitary peripheral nodule. In earlier stages, the differential diagnosis of SCLC spans other neuroendocrine lung tumors and NSCLC, in particular, basaloid carcinoma, extrapulmonary small cell tumors, and lymphoma.

Because the concentration of circulating tumor cells in SCLC is among the highest of any solid tumor, SCLC is characterized by a rapid doubling time, high growth fraction, and early development of widespread metastases. It is likely for this reason that CT screening does not seem effective in detecting early-stage SCLC. Common sites of SCLC metastasis are the contralateral lung, the brain, liver, adrenal glands, and bone. Most cases of SCLC are caused by smoking.

Metastatic spread is often evident on radiologic exam, sometimes showing pleural and pericardial effusions. In general, workup for SCLC includes imaging (contrast-enhanced CT or F-FDG PET–CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and brain MRI with contrast), blood tests (cell count, liver and kidney function, and lactate dehydrogenase), and ECG. Biopsies are generally procured by bronchoscopy with or without endobronchial ultrasonography; if accessible, a biopsy of a distal metastatic site may be obtained. Diagnosis of SCLC is confirmed by histopathologic examination via cytology.

Patients with extensive-stage SCLC are typically treated with systemic chemotherapy with or without immunotherapy. In the early stages, SCLC is very responsive to cytotoxic therapies, with response rates over 60% even in patients with metastatic disease. Until recently, the only second-line therapy for recurrent metastatic SCLC was the topoisomerase I inhibitor topotecan. However, lurbinectedin was granted accelerated approval for second-line therapy after demonstrating a 35% response rate in a single-arm phase 2 study of 105 patients. In addition, the anti–programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibodies nivolumab and pembrolizumab were granted accelerated approval for third-line use. Finally, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines note that participation in clinical trials should be strongly encouraged for all patients with SCLC.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 58-year-old man presents with a persistent dry cough that has developed over the past 8 weeks. He has lost about 8-10 lb in under 3 months. Height is 5 ft 10 in and weight is 172 lb (BMI 24.7). Although he quit smoking about 15 years ago, his wife still smokes. He has been screened twice for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), most recently a year and a half ago. Chest radiograph shows multiple pulmonary nodules of varying sizes and a small right basal effusion.