User login

SHM SPARK Helps Bridge Gap for Hospitalist MOC Exam Prep

SHM SPARK delivers 175 vignette-style, multiple-choice questions that bridge the primary knowledge gaps found within existing MOC exam-preparation products. It offers up to 10.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits of CME. Content areas covered include:

- Palliative care, ethics, and decision making

- Patient safety

- Perioperative care and consultative co-management

- Quality, cost, and clinical reasoning

The Hospitalist recently spoke with three SHM SPARK users about its impact on their exam-preparation efforts: Louis O’Boyle, DO, SFHM, CLHM, medical director of Advanced Inpatient Medicine, a hospitalist management company in Lakeville, Pa.; Timothy Crone, MD, SFHM, medical director of Enterprise Intelligence and Analytics and former vice-chairman of the Department of Hospital Medicine at Cleveland Clinic; and Aroop Pal, MD, FHM, hospitalist, associate professor, and program director of transitions of care services at University of Kansas Medical Center.

Question: Why did you choose to purchase SHM SPARK?

Dr. O’Boyle: I was expecting the FPHM exam to be more challenging than the traditional exam, so I wanted to get as much help as possible, particularly in those areas that are less utilized in day-to-day hospitalist practice. This exam covered the 40% or so that is not covered in a typical review course.

Dr. Crone: I was selected to receive SHM SPARK as a test user, but had I not been, I probably would have purchased it as there was not another single tool that addressed the content gap preparing for the exam that SHM SPARK did. On HMX and in conversations with other hospitalists, I was aware of “collections” of tools, like books and websites, that people had put together to review information not covered in MKSAP or other standard test-prep materials. SHM SPARK brought that content together in a single space, which allowed me to take a systematic approach to reviewing the content areas covered as opposed to a potentially incomplete, piecemeal approach.

Dr. Pal: There are no board review products focused on the 40% of the FPHM exam not based on traditional clinical knowledge. Thus, it made sense to give SHM SPARK a try, especially since it was affordable for members.

Q: During your preparation, what was the most useful aspect of SHM SPARK?

Dr. Crone: I find that working through computer-based questions similar in format to the actual exam is most helpful to me. Both in terms of knowledge acquisition and comfort level with the exam itself, the “context-dependent learning” aspect is important for me. SHM SPARK allowed me to work through its content areas in that way and also helped me identify and correct gaps in my knowledge as opposed to guessing what was important and searching for source material on my own.

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK helped frame how quality and patient safety questions would or could be posed on the FPHM exam. This made it helpful to determine what content is fair game for the exam and the key competencies ABIM was focusing on—especially since traditional board review materials do not cover as much quality-specific content.

Dr. O’Boyle: The most useful aspects were the topics that are not encountered specifically in everyday practice, such as the sections on quality, cost, and clinical reasoning, as well as patient safety.

Q: After taking the exam, in retrospect, how effective was SHM SPARK in preparing you?

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK was valuable to me and worth the time and effort. The board exam itself is a little bit of a blur; if nothing else, it helped me identify areas that I needed more information on and reinforced some knowledge I had prior to taking the exam.

Dr. O’Boyle: The SHM SPARK review absolutely helped me perform well on the sections that were covered. I think it is almost essential to prepare for the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine exam.

Dr. Crone: I passed, so I’d label that effective! In some cases, using SHM SPARK, I scored 90% or better on a first pass on questions with no review; that has not been my experience with MKSAP or Med Study questions. The only recommendation I would have is to make some of the questions a bit more rigorous. However, SHM SPARK clearly met a need nothing else did.

Q: If you were to tell a fellow hospitalist one thing about SHM SPARK, what would it be?

Dr. O’Boyle: I encourage everyone to purchase it. It is an excellent resource guide. The way the exam is currently designed, you may need the additional 40% of exam content covered by SHM SPARK in order to pass. By that, I mean that some of the medical questions were so complicated and cumbersome that they were at the specialist level and not at all representative of what a typical hospitalist routinely encounters, in my opinion. Therefore, knowing this portion of the exam content through SHM SPARK made up for the questions that I felt should not have been fair game. I, for one, would likely not have passed without SHM SPARK.

Dr. Crone: It’s worth the time, effort, and cost. Although much or most of the exam content was couched in a clinical scenario, substantive content existed on the MOC exam around these subject areas. To not use some form of structured approach to covering this material would have been a mistake.

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK is extremely valuable if you plan to take the FPHM exam as it highlights many areas not covered by any other review material. It offers great CME, too! TH

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications specialist.

More Info

For more information about how SHM SPARK can help you master your preparation for the FPHM MOC exam this fall, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/SPARK.

SHM SPARK delivers 175 vignette-style, multiple-choice questions that bridge the primary knowledge gaps found within existing MOC exam-preparation products. It offers up to 10.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits of CME. Content areas covered include:

- Palliative care, ethics, and decision making

- Patient safety

- Perioperative care and consultative co-management

- Quality, cost, and clinical reasoning

The Hospitalist recently spoke with three SHM SPARK users about its impact on their exam-preparation efforts: Louis O’Boyle, DO, SFHM, CLHM, medical director of Advanced Inpatient Medicine, a hospitalist management company in Lakeville, Pa.; Timothy Crone, MD, SFHM, medical director of Enterprise Intelligence and Analytics and former vice-chairman of the Department of Hospital Medicine at Cleveland Clinic; and Aroop Pal, MD, FHM, hospitalist, associate professor, and program director of transitions of care services at University of Kansas Medical Center.

Question: Why did you choose to purchase SHM SPARK?

Dr. O’Boyle: I was expecting the FPHM exam to be more challenging than the traditional exam, so I wanted to get as much help as possible, particularly in those areas that are less utilized in day-to-day hospitalist practice. This exam covered the 40% or so that is not covered in a typical review course.

Dr. Crone: I was selected to receive SHM SPARK as a test user, but had I not been, I probably would have purchased it as there was not another single tool that addressed the content gap preparing for the exam that SHM SPARK did. On HMX and in conversations with other hospitalists, I was aware of “collections” of tools, like books and websites, that people had put together to review information not covered in MKSAP or other standard test-prep materials. SHM SPARK brought that content together in a single space, which allowed me to take a systematic approach to reviewing the content areas covered as opposed to a potentially incomplete, piecemeal approach.

Dr. Pal: There are no board review products focused on the 40% of the FPHM exam not based on traditional clinical knowledge. Thus, it made sense to give SHM SPARK a try, especially since it was affordable for members.

Q: During your preparation, what was the most useful aspect of SHM SPARK?

Dr. Crone: I find that working through computer-based questions similar in format to the actual exam is most helpful to me. Both in terms of knowledge acquisition and comfort level with the exam itself, the “context-dependent learning” aspect is important for me. SHM SPARK allowed me to work through its content areas in that way and also helped me identify and correct gaps in my knowledge as opposed to guessing what was important and searching for source material on my own.

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK helped frame how quality and patient safety questions would or could be posed on the FPHM exam. This made it helpful to determine what content is fair game for the exam and the key competencies ABIM was focusing on—especially since traditional board review materials do not cover as much quality-specific content.

Dr. O’Boyle: The most useful aspects were the topics that are not encountered specifically in everyday practice, such as the sections on quality, cost, and clinical reasoning, as well as patient safety.

Q: After taking the exam, in retrospect, how effective was SHM SPARK in preparing you?

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK was valuable to me and worth the time and effort. The board exam itself is a little bit of a blur; if nothing else, it helped me identify areas that I needed more information on and reinforced some knowledge I had prior to taking the exam.

Dr. O’Boyle: The SHM SPARK review absolutely helped me perform well on the sections that were covered. I think it is almost essential to prepare for the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine exam.

Dr. Crone: I passed, so I’d label that effective! In some cases, using SHM SPARK, I scored 90% or better on a first pass on questions with no review; that has not been my experience with MKSAP or Med Study questions. The only recommendation I would have is to make some of the questions a bit more rigorous. However, SHM SPARK clearly met a need nothing else did.

Q: If you were to tell a fellow hospitalist one thing about SHM SPARK, what would it be?

Dr. O’Boyle: I encourage everyone to purchase it. It is an excellent resource guide. The way the exam is currently designed, you may need the additional 40% of exam content covered by SHM SPARK in order to pass. By that, I mean that some of the medical questions were so complicated and cumbersome that they were at the specialist level and not at all representative of what a typical hospitalist routinely encounters, in my opinion. Therefore, knowing this portion of the exam content through SHM SPARK made up for the questions that I felt should not have been fair game. I, for one, would likely not have passed without SHM SPARK.

Dr. Crone: It’s worth the time, effort, and cost. Although much or most of the exam content was couched in a clinical scenario, substantive content existed on the MOC exam around these subject areas. To not use some form of structured approach to covering this material would have been a mistake.

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK is extremely valuable if you plan to take the FPHM exam as it highlights many areas not covered by any other review material. It offers great CME, too! TH

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications specialist.

More Info

For more information about how SHM SPARK can help you master your preparation for the FPHM MOC exam this fall, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/SPARK.

SHM SPARK delivers 175 vignette-style, multiple-choice questions that bridge the primary knowledge gaps found within existing MOC exam-preparation products. It offers up to 10.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits of CME. Content areas covered include:

- Palliative care, ethics, and decision making

- Patient safety

- Perioperative care and consultative co-management

- Quality, cost, and clinical reasoning

The Hospitalist recently spoke with three SHM SPARK users about its impact on their exam-preparation efforts: Louis O’Boyle, DO, SFHM, CLHM, medical director of Advanced Inpatient Medicine, a hospitalist management company in Lakeville, Pa.; Timothy Crone, MD, SFHM, medical director of Enterprise Intelligence and Analytics and former vice-chairman of the Department of Hospital Medicine at Cleveland Clinic; and Aroop Pal, MD, FHM, hospitalist, associate professor, and program director of transitions of care services at University of Kansas Medical Center.

Question: Why did you choose to purchase SHM SPARK?

Dr. O’Boyle: I was expecting the FPHM exam to be more challenging than the traditional exam, so I wanted to get as much help as possible, particularly in those areas that are less utilized in day-to-day hospitalist practice. This exam covered the 40% or so that is not covered in a typical review course.

Dr. Crone: I was selected to receive SHM SPARK as a test user, but had I not been, I probably would have purchased it as there was not another single tool that addressed the content gap preparing for the exam that SHM SPARK did. On HMX and in conversations with other hospitalists, I was aware of “collections” of tools, like books and websites, that people had put together to review information not covered in MKSAP or other standard test-prep materials. SHM SPARK brought that content together in a single space, which allowed me to take a systematic approach to reviewing the content areas covered as opposed to a potentially incomplete, piecemeal approach.

Dr. Pal: There are no board review products focused on the 40% of the FPHM exam not based on traditional clinical knowledge. Thus, it made sense to give SHM SPARK a try, especially since it was affordable for members.

Q: During your preparation, what was the most useful aspect of SHM SPARK?

Dr. Crone: I find that working through computer-based questions similar in format to the actual exam is most helpful to me. Both in terms of knowledge acquisition and comfort level with the exam itself, the “context-dependent learning” aspect is important for me. SHM SPARK allowed me to work through its content areas in that way and also helped me identify and correct gaps in my knowledge as opposed to guessing what was important and searching for source material on my own.

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK helped frame how quality and patient safety questions would or could be posed on the FPHM exam. This made it helpful to determine what content is fair game for the exam and the key competencies ABIM was focusing on—especially since traditional board review materials do not cover as much quality-specific content.

Dr. O’Boyle: The most useful aspects were the topics that are not encountered specifically in everyday practice, such as the sections on quality, cost, and clinical reasoning, as well as patient safety.

Q: After taking the exam, in retrospect, how effective was SHM SPARK in preparing you?

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK was valuable to me and worth the time and effort. The board exam itself is a little bit of a blur; if nothing else, it helped me identify areas that I needed more information on and reinforced some knowledge I had prior to taking the exam.

Dr. O’Boyle: The SHM SPARK review absolutely helped me perform well on the sections that were covered. I think it is almost essential to prepare for the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine exam.

Dr. Crone: I passed, so I’d label that effective! In some cases, using SHM SPARK, I scored 90% or better on a first pass on questions with no review; that has not been my experience with MKSAP or Med Study questions. The only recommendation I would have is to make some of the questions a bit more rigorous. However, SHM SPARK clearly met a need nothing else did.

Q: If you were to tell a fellow hospitalist one thing about SHM SPARK, what would it be?

Dr. O’Boyle: I encourage everyone to purchase it. It is an excellent resource guide. The way the exam is currently designed, you may need the additional 40% of exam content covered by SHM SPARK in order to pass. By that, I mean that some of the medical questions were so complicated and cumbersome that they were at the specialist level and not at all representative of what a typical hospitalist routinely encounters, in my opinion. Therefore, knowing this portion of the exam content through SHM SPARK made up for the questions that I felt should not have been fair game. I, for one, would likely not have passed without SHM SPARK.

Dr. Crone: It’s worth the time, effort, and cost. Although much or most of the exam content was couched in a clinical scenario, substantive content existed on the MOC exam around these subject areas. To not use some form of structured approach to covering this material would have been a mistake.

Dr. Pal: SHM SPARK is extremely valuable if you plan to take the FPHM exam as it highlights many areas not covered by any other review material. It offers great CME, too! TH

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications specialist.

More Info

For more information about how SHM SPARK can help you master your preparation for the FPHM MOC exam this fall, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/SPARK.

Measure Hospitalist Engagement with SHM’s Engagement Benchmarking Service

One of the most important questions for leaders of hospital medicine groups is, “How can I measure the level of engagement of my hospitalists?” Measuring hospitalist engagement can be difficult, and many leaders are not satisfied with the tools they currently have at their disposal.

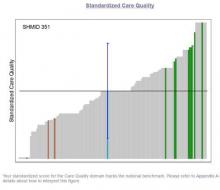

SHM is here to help. SHM developed an Engagement Benchmarking Service to evaluate relationships with leaders, care quality, autonomy, effective motivation, burnout risk, and more. You can see your standardized score in the various domains and where it falls within the national benchmark. This helps you know what is working well and identifies the areas for improvement in your hospital medicine group.

More than 80% of respondents from 2015 indicated that they will utilize the service again and plan to recommend it to a colleague. Help ensure hospitalists are engaged in your HM group by registering now for the next cohort at www.hospitalmedicine.org/pmad3.

One of the most important questions for leaders of hospital medicine groups is, “How can I measure the level of engagement of my hospitalists?” Measuring hospitalist engagement can be difficult, and many leaders are not satisfied with the tools they currently have at their disposal.

SHM is here to help. SHM developed an Engagement Benchmarking Service to evaluate relationships with leaders, care quality, autonomy, effective motivation, burnout risk, and more. You can see your standardized score in the various domains and where it falls within the national benchmark. This helps you know what is working well and identifies the areas for improvement in your hospital medicine group.

More than 80% of respondents from 2015 indicated that they will utilize the service again and plan to recommend it to a colleague. Help ensure hospitalists are engaged in your HM group by registering now for the next cohort at www.hospitalmedicine.org/pmad3.

One of the most important questions for leaders of hospital medicine groups is, “How can I measure the level of engagement of my hospitalists?” Measuring hospitalist engagement can be difficult, and many leaders are not satisfied with the tools they currently have at their disposal.

SHM is here to help. SHM developed an Engagement Benchmarking Service to evaluate relationships with leaders, care quality, autonomy, effective motivation, burnout risk, and more. You can see your standardized score in the various domains and where it falls within the national benchmark. This helps you know what is working well and identifies the areas for improvement in your hospital medicine group.

More than 80% of respondents from 2015 indicated that they will utilize the service again and plan to recommend it to a colleague. Help ensure hospitalists are engaged in your HM group by registering now for the next cohort at www.hospitalmedicine.org/pmad3.

Key Medicare Fund Could Exhaust Reserves in 2028: Trustees

WASHINGTON—The U.S. federal program that pays elderly Americans' hospital bills will exhaust reserves in 2028, two years sooner than last year's estimate, trustees of the program said on Wednesday.

In their annual financial review, the trustees also said that the combined Social Security and disability trust fund reserves are estimated to run out in 2034, the same projection as last year.

The Medicare program's trust fund for hospital care is still scheduled to have sufficient funding 11 years longer than the estimate given before the Affordable Care Act was passed, the trustees said.

They put the shortening of the timeline down to changes in estimates of income and cost, particularly in the near term.

A depletion in funds available for Medicare and Social Security does not mean the programs would suddenly stop. At the current rate of payroll tax collections, Medicare would be able to cover 87 percent of costs in 2028. This would fall to 79 percent by 2043 and then gradually increase.

Social Security would be able to pay about three-quarters of scheduled benefits from 2034 to 2090, the trustees said.

WASHINGTON—The U.S. federal program that pays elderly Americans' hospital bills will exhaust reserves in 2028, two years sooner than last year's estimate, trustees of the program said on Wednesday.

In their annual financial review, the trustees also said that the combined Social Security and disability trust fund reserves are estimated to run out in 2034, the same projection as last year.

The Medicare program's trust fund for hospital care is still scheduled to have sufficient funding 11 years longer than the estimate given before the Affordable Care Act was passed, the trustees said.

They put the shortening of the timeline down to changes in estimates of income and cost, particularly in the near term.

A depletion in funds available for Medicare and Social Security does not mean the programs would suddenly stop. At the current rate of payroll tax collections, Medicare would be able to cover 87 percent of costs in 2028. This would fall to 79 percent by 2043 and then gradually increase.

Social Security would be able to pay about three-quarters of scheduled benefits from 2034 to 2090, the trustees said.

WASHINGTON—The U.S. federal program that pays elderly Americans' hospital bills will exhaust reserves in 2028, two years sooner than last year's estimate, trustees of the program said on Wednesday.

In their annual financial review, the trustees also said that the combined Social Security and disability trust fund reserves are estimated to run out in 2034, the same projection as last year.

The Medicare program's trust fund for hospital care is still scheduled to have sufficient funding 11 years longer than the estimate given before the Affordable Care Act was passed, the trustees said.

They put the shortening of the timeline down to changes in estimates of income and cost, particularly in the near term.

A depletion in funds available for Medicare and Social Security does not mean the programs would suddenly stop. At the current rate of payroll tax collections, Medicare would be able to cover 87 percent of costs in 2028. This would fall to 79 percent by 2043 and then gradually increase.

Social Security would be able to pay about three-quarters of scheduled benefits from 2034 to 2090, the trustees said.

Lesson in Improper Allocations, Unaccounted for NP/PA Contributions

I visited during a hot Florida summer in the mid 1990s and could readily see that the practice was great in most respects. The large multispecialty group had recruited talented hospitalists and had put in place effective operational practices. All seemed to be going well, but inappropriate overhead allocation was undermining the success of their efforts.

The multispecialty group employing the hospitalists used the same formula to allocate overhead to the hospitalists that was in place for other specialties. And compensation was essentially each doctor’s collections minus overhead, leaving the hospitalists with annual compensation much lower than they could reasonably expect. With the group deducting from hospitalist collections the same overhead expenses charged to other specialties, including a share of outpatient buildings, staff, and supplies, the hospitalists were paying a lot for services they weren’t using. This group corrected the errors but not until some talented doctors had resigned because of the compensation formula.

This was a common mistake made by multispecialty groups that employed hospitalists years ago. Today, nearly all such groups assess an appropriately smaller portion of overhead to hospitalists than office-based doctors.

Typical Hospitalist Overhead

It is still tricky to correctly assess and allocate hospitalist overhead. This meaningfully influences the apparent total cost of the program and hence the amount of support paid by the hospital or other entity. (This support is often referred to as a “subsidy,” though I don’t care for that term because of its negative connotation.)

For example, costs for billing and collections services, malpractice insurance, temporary staffing (locums), and an overhead allocation that pays for things like the salaries of medical group administrators and clerical staff may or may not be attributed to the hospitalist budget or “cost center.” This is one of several factors that make it awfully tricky to compare the total costs and/or hospital financial support between different hospitalist groups.

SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report includes detailed instructions regarding which expenses the survey respondents should include as overhead costs, but I think it’s safe to assume that not all responses are fully compliant. I’m confident there is a meaningful amount of “noise” in these figures. Numbers like the median financial support per FTE hospitalist per year ($156,063 in the 2014 report) should only be used as a guideline and not a precise number that might apply in your setting. My reasoning is that the collections rate and compensation amount can vary tremendously from one practice to another and will typically have a far larger influence on the amount of financial support provided by the hospital than which expenses are or aren’t included as overhead. But I am confining this discussion to the latter.

APC Costs: One Factor Driving Increased Support

SHM has been surveying the financial support per physician FTE for about 15 years, and it has shown a steady increase. It was about $60,000 per FTE annually when first surveyed in the late 1990s; it has gone up every survey since. The best explanation for this seems to an increase in hospitalist compensation while production and revenue have remained relatively flat.

There likely are many other factors in play. One important one is physician assistant and nurse practitioner costs. The survey divides the total annual support provided to the whole hospitalist practice by the total number of physician FTEs. NPs and PAs are becoming more common in hospitalist groups; 65% of groups included them in 2014, up from 54% in 2012. Yet the cost of employing them, primarily salary and benefits, appears in the numerator but not the denominator of the support per physician FTE figure.

This means a group that adds NP/PA staffing, which typically requires an accompanying increase in hospital financial support, while maintaining the same number of physician FTEs will show an increase in hospital support per physician FTE. But this fails to capture that the practice’s work product (i.e., patients seen) has increased as a result of increasing its clinical staff.

This is a tricky issue to fix. SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, which manages the survey, is aware of the issue and may make future adjustments to account for it. The best method might be to convert total staffing by physicians and NP/PAs into physician-equivalent FTEs (I described one method for doing this in my August 2009 column titled “Volume Variables”) or some other method that clearly accounts for both physician and NP/PA staffing levels. Other alternatives would be to divide the annual support by the number of billed encounters or some other measure of “work output” or to report percent of the total practice revenue that comes from hospital support versus professional fee collections and other sources.

Why Allocation of NP/PA Costs and FTEs Matter

Another way to think of this issue is that including NP/PA costs but not their work (FTEs) in the financial support per FTE figure overlooks the important work they can do for a hospitalist practice. And it can lead one to conclude hospitals’ costs per clinician FTE are rising faster than is actually the case.

This is only one of the tricky issues in accurately understanding hospitalist overhead and costs to the hospital they serve. TH

I visited during a hot Florida summer in the mid 1990s and could readily see that the practice was great in most respects. The large multispecialty group had recruited talented hospitalists and had put in place effective operational practices. All seemed to be going well, but inappropriate overhead allocation was undermining the success of their efforts.

The multispecialty group employing the hospitalists used the same formula to allocate overhead to the hospitalists that was in place for other specialties. And compensation was essentially each doctor’s collections minus overhead, leaving the hospitalists with annual compensation much lower than they could reasonably expect. With the group deducting from hospitalist collections the same overhead expenses charged to other specialties, including a share of outpatient buildings, staff, and supplies, the hospitalists were paying a lot for services they weren’t using. This group corrected the errors but not until some talented doctors had resigned because of the compensation formula.

This was a common mistake made by multispecialty groups that employed hospitalists years ago. Today, nearly all such groups assess an appropriately smaller portion of overhead to hospitalists than office-based doctors.

Typical Hospitalist Overhead

It is still tricky to correctly assess and allocate hospitalist overhead. This meaningfully influences the apparent total cost of the program and hence the amount of support paid by the hospital or other entity. (This support is often referred to as a “subsidy,” though I don’t care for that term because of its negative connotation.)

For example, costs for billing and collections services, malpractice insurance, temporary staffing (locums), and an overhead allocation that pays for things like the salaries of medical group administrators and clerical staff may or may not be attributed to the hospitalist budget or “cost center.” This is one of several factors that make it awfully tricky to compare the total costs and/or hospital financial support between different hospitalist groups.

SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report includes detailed instructions regarding which expenses the survey respondents should include as overhead costs, but I think it’s safe to assume that not all responses are fully compliant. I’m confident there is a meaningful amount of “noise” in these figures. Numbers like the median financial support per FTE hospitalist per year ($156,063 in the 2014 report) should only be used as a guideline and not a precise number that might apply in your setting. My reasoning is that the collections rate and compensation amount can vary tremendously from one practice to another and will typically have a far larger influence on the amount of financial support provided by the hospital than which expenses are or aren’t included as overhead. But I am confining this discussion to the latter.

APC Costs: One Factor Driving Increased Support

SHM has been surveying the financial support per physician FTE for about 15 years, and it has shown a steady increase. It was about $60,000 per FTE annually when first surveyed in the late 1990s; it has gone up every survey since. The best explanation for this seems to an increase in hospitalist compensation while production and revenue have remained relatively flat.

There likely are many other factors in play. One important one is physician assistant and nurse practitioner costs. The survey divides the total annual support provided to the whole hospitalist practice by the total number of physician FTEs. NPs and PAs are becoming more common in hospitalist groups; 65% of groups included them in 2014, up from 54% in 2012. Yet the cost of employing them, primarily salary and benefits, appears in the numerator but not the denominator of the support per physician FTE figure.

This means a group that adds NP/PA staffing, which typically requires an accompanying increase in hospital financial support, while maintaining the same number of physician FTEs will show an increase in hospital support per physician FTE. But this fails to capture that the practice’s work product (i.e., patients seen) has increased as a result of increasing its clinical staff.

This is a tricky issue to fix. SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, which manages the survey, is aware of the issue and may make future adjustments to account for it. The best method might be to convert total staffing by physicians and NP/PAs into physician-equivalent FTEs (I described one method for doing this in my August 2009 column titled “Volume Variables”) or some other method that clearly accounts for both physician and NP/PA staffing levels. Other alternatives would be to divide the annual support by the number of billed encounters or some other measure of “work output” or to report percent of the total practice revenue that comes from hospital support versus professional fee collections and other sources.

Why Allocation of NP/PA Costs and FTEs Matter

Another way to think of this issue is that including NP/PA costs but not their work (FTEs) in the financial support per FTE figure overlooks the important work they can do for a hospitalist practice. And it can lead one to conclude hospitals’ costs per clinician FTE are rising faster than is actually the case.

This is only one of the tricky issues in accurately understanding hospitalist overhead and costs to the hospital they serve. TH

I visited during a hot Florida summer in the mid 1990s and could readily see that the practice was great in most respects. The large multispecialty group had recruited talented hospitalists and had put in place effective operational practices. All seemed to be going well, but inappropriate overhead allocation was undermining the success of their efforts.

The multispecialty group employing the hospitalists used the same formula to allocate overhead to the hospitalists that was in place for other specialties. And compensation was essentially each doctor’s collections minus overhead, leaving the hospitalists with annual compensation much lower than they could reasonably expect. With the group deducting from hospitalist collections the same overhead expenses charged to other specialties, including a share of outpatient buildings, staff, and supplies, the hospitalists were paying a lot for services they weren’t using. This group corrected the errors but not until some talented doctors had resigned because of the compensation formula.

This was a common mistake made by multispecialty groups that employed hospitalists years ago. Today, nearly all such groups assess an appropriately smaller portion of overhead to hospitalists than office-based doctors.

Typical Hospitalist Overhead

It is still tricky to correctly assess and allocate hospitalist overhead. This meaningfully influences the apparent total cost of the program and hence the amount of support paid by the hospital or other entity. (This support is often referred to as a “subsidy,” though I don’t care for that term because of its negative connotation.)

For example, costs for billing and collections services, malpractice insurance, temporary staffing (locums), and an overhead allocation that pays for things like the salaries of medical group administrators and clerical staff may or may not be attributed to the hospitalist budget or “cost center.” This is one of several factors that make it awfully tricky to compare the total costs and/or hospital financial support between different hospitalist groups.

SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report includes detailed instructions regarding which expenses the survey respondents should include as overhead costs, but I think it’s safe to assume that not all responses are fully compliant. I’m confident there is a meaningful amount of “noise” in these figures. Numbers like the median financial support per FTE hospitalist per year ($156,063 in the 2014 report) should only be used as a guideline and not a precise number that might apply in your setting. My reasoning is that the collections rate and compensation amount can vary tremendously from one practice to another and will typically have a far larger influence on the amount of financial support provided by the hospital than which expenses are or aren’t included as overhead. But I am confining this discussion to the latter.

APC Costs: One Factor Driving Increased Support

SHM has been surveying the financial support per physician FTE for about 15 years, and it has shown a steady increase. It was about $60,000 per FTE annually when first surveyed in the late 1990s; it has gone up every survey since. The best explanation for this seems to an increase in hospitalist compensation while production and revenue have remained relatively flat.

There likely are many other factors in play. One important one is physician assistant and nurse practitioner costs. The survey divides the total annual support provided to the whole hospitalist practice by the total number of physician FTEs. NPs and PAs are becoming more common in hospitalist groups; 65% of groups included them in 2014, up from 54% in 2012. Yet the cost of employing them, primarily salary and benefits, appears in the numerator but not the denominator of the support per physician FTE figure.

This means a group that adds NP/PA staffing, which typically requires an accompanying increase in hospital financial support, while maintaining the same number of physician FTEs will show an increase in hospital support per physician FTE. But this fails to capture that the practice’s work product (i.e., patients seen) has increased as a result of increasing its clinical staff.

This is a tricky issue to fix. SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, which manages the survey, is aware of the issue and may make future adjustments to account for it. The best method might be to convert total staffing by physicians and NP/PAs into physician-equivalent FTEs (I described one method for doing this in my August 2009 column titled “Volume Variables”) or some other method that clearly accounts for both physician and NP/PA staffing levels. Other alternatives would be to divide the annual support by the number of billed encounters or some other measure of “work output” or to report percent of the total practice revenue that comes from hospital support versus professional fee collections and other sources.

Why Allocation of NP/PA Costs and FTEs Matter

Another way to think of this issue is that including NP/PA costs but not their work (FTEs) in the financial support per FTE figure overlooks the important work they can do for a hospitalist practice. And it can lead one to conclude hospitals’ costs per clinician FTE are rising faster than is actually the case.

This is only one of the tricky issues in accurately understanding hospitalist overhead and costs to the hospital they serve. TH

LETTER: Emory Hospital Medicine’s Growth Sparks Establishment of NP, PA Career Track

Due to many reasons, the healthcare paradigm has shifted, dictating alternative staffing models to manage the burgeoning inpatient census of hospital-based physicians. Herein, we will briefly describe the Emory University Division of Hospital Medicine (EDHM) approach to utilizing advanced practice providers (APPs) in the care of inpatients and summarize key components of the program that improve sustainability for providers.

The EDHM in Atlanta matriculated APPs into its service in 2004. Currently, there are 22 APPs across all Emory HM sites. The largest group is at Emory University Hospital Midtown (EUHM).

At EUHM, the addition of a renal service created concern for increased workload for the physicians. APPs were recruited to bridge the gap in 2011. Initially, the role was ill-defined, but over time, with physician and administrative leadership buy-in and support, the role has evolved. Currently at EUHM, APPs are practicing in other HM services, allowing them to practice near or at the top of their scope of practice. The 12 hospitalist APPs at EUHM practice in four roles: nocturnist, frontline provider in the observation unit, dedicated renal service, and generalist on an overflow team.

Along with the rapid growth of APPs on the service came the need for structured leadership, improved onboarding procedures, competency maintenance, advocacy, and professional development activities. Essentially, we needed to create a career track parallel to that of the physicians without compromising the portion of our scopes of our practice that overlap (i.e., patient care) while supporting our regulatory differences.

The professional development plans incorporated findings from APP exit interviews at the University of Maryland Medical Center highlighting the following retention issues:1

- Length of time for credentialing

- Role clarity

- Inadequate clinical orientation

- Feelings of clinical incompetence

- Feelings of isolation

With the instillation of APP leadership, the team created a comprehensive APP program. The Hospital Medicine APP program at EUHM includes the following components:

- APP representation at monthly clinical operation meetings and quarterly education council meetings to ensure that APP competency and regulatory issues are always represented.

- Orientation personally tailored to the APP’s level of clinical expertise, with a post-orientation meeting with leadership and remediation, if needed.

- APP incentives to teach NP or PA students, conduct in-services, join committees, or participate in other leadership opportunities.

- APPs invited to attend and/or present at all divisional small and large group learning opportunities (e.g., Grand Rounds, Lunch and Learn, Journal Club).

- APPs allocated time and space to meet and discuss practice issues.

- Newly developed Mini-Hospitalist Academy, which offers monthly workshops to all hospitalist physicians and APPs, from novice to expert.

- Dedicated APP Ongoing Professional Performance Evaluation (OPPE) program.

- In addition to the annual monetary support offered for educational opportunities, the division offers an annual Faculty Development Award. This award is by application for eligible educational opportunities; APPs are welcome to apply and have consistently been awarded support to pursue myriad opportunities.

This successful APP-physician collaboration is driven by a committed group of professionals who are sensitive to the shifting healthcare paradigm. Our APPs and physicians are constantly adapting their practice so that our collaboration is safe, evidence-based, and professionally fulfilling. TH

Yvonne Brown, DNP, MSN, ACNP-C, FNP-C, nurse practitioner, lead advanced practice provider, Division of Hospital Medicine, Emory Healthcare, Emory University Hospital Midtown, Atlanta

Reference

1. Bahouth MN, Esposito-Herr MB. Orientation program for hospital-based nurse practitioners. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2009;20(1):82-90.

Due to many reasons, the healthcare paradigm has shifted, dictating alternative staffing models to manage the burgeoning inpatient census of hospital-based physicians. Herein, we will briefly describe the Emory University Division of Hospital Medicine (EDHM) approach to utilizing advanced practice providers (APPs) in the care of inpatients and summarize key components of the program that improve sustainability for providers.

The EDHM in Atlanta matriculated APPs into its service in 2004. Currently, there are 22 APPs across all Emory HM sites. The largest group is at Emory University Hospital Midtown (EUHM).

At EUHM, the addition of a renal service created concern for increased workload for the physicians. APPs were recruited to bridge the gap in 2011. Initially, the role was ill-defined, but over time, with physician and administrative leadership buy-in and support, the role has evolved. Currently at EUHM, APPs are practicing in other HM services, allowing them to practice near or at the top of their scope of practice. The 12 hospitalist APPs at EUHM practice in four roles: nocturnist, frontline provider in the observation unit, dedicated renal service, and generalist on an overflow team.

Along with the rapid growth of APPs on the service came the need for structured leadership, improved onboarding procedures, competency maintenance, advocacy, and professional development activities. Essentially, we needed to create a career track parallel to that of the physicians without compromising the portion of our scopes of our practice that overlap (i.e., patient care) while supporting our regulatory differences.

The professional development plans incorporated findings from APP exit interviews at the University of Maryland Medical Center highlighting the following retention issues:1

- Length of time for credentialing

- Role clarity

- Inadequate clinical orientation

- Feelings of clinical incompetence

- Feelings of isolation

With the instillation of APP leadership, the team created a comprehensive APP program. The Hospital Medicine APP program at EUHM includes the following components:

- APP representation at monthly clinical operation meetings and quarterly education council meetings to ensure that APP competency and regulatory issues are always represented.

- Orientation personally tailored to the APP’s level of clinical expertise, with a post-orientation meeting with leadership and remediation, if needed.

- APP incentives to teach NP or PA students, conduct in-services, join committees, or participate in other leadership opportunities.

- APPs invited to attend and/or present at all divisional small and large group learning opportunities (e.g., Grand Rounds, Lunch and Learn, Journal Club).

- APPs allocated time and space to meet and discuss practice issues.

- Newly developed Mini-Hospitalist Academy, which offers monthly workshops to all hospitalist physicians and APPs, from novice to expert.

- Dedicated APP Ongoing Professional Performance Evaluation (OPPE) program.

- In addition to the annual monetary support offered for educational opportunities, the division offers an annual Faculty Development Award. This award is by application for eligible educational opportunities; APPs are welcome to apply and have consistently been awarded support to pursue myriad opportunities.

This successful APP-physician collaboration is driven by a committed group of professionals who are sensitive to the shifting healthcare paradigm. Our APPs and physicians are constantly adapting their practice so that our collaboration is safe, evidence-based, and professionally fulfilling. TH

Yvonne Brown, DNP, MSN, ACNP-C, FNP-C, nurse practitioner, lead advanced practice provider, Division of Hospital Medicine, Emory Healthcare, Emory University Hospital Midtown, Atlanta

Reference

1. Bahouth MN, Esposito-Herr MB. Orientation program for hospital-based nurse practitioners. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2009;20(1):82-90.

Due to many reasons, the healthcare paradigm has shifted, dictating alternative staffing models to manage the burgeoning inpatient census of hospital-based physicians. Herein, we will briefly describe the Emory University Division of Hospital Medicine (EDHM) approach to utilizing advanced practice providers (APPs) in the care of inpatients and summarize key components of the program that improve sustainability for providers.

The EDHM in Atlanta matriculated APPs into its service in 2004. Currently, there are 22 APPs across all Emory HM sites. The largest group is at Emory University Hospital Midtown (EUHM).

At EUHM, the addition of a renal service created concern for increased workload for the physicians. APPs were recruited to bridge the gap in 2011. Initially, the role was ill-defined, but over time, with physician and administrative leadership buy-in and support, the role has evolved. Currently at EUHM, APPs are practicing in other HM services, allowing them to practice near or at the top of their scope of practice. The 12 hospitalist APPs at EUHM practice in four roles: nocturnist, frontline provider in the observation unit, dedicated renal service, and generalist on an overflow team.

Along with the rapid growth of APPs on the service came the need for structured leadership, improved onboarding procedures, competency maintenance, advocacy, and professional development activities. Essentially, we needed to create a career track parallel to that of the physicians without compromising the portion of our scopes of our practice that overlap (i.e., patient care) while supporting our regulatory differences.

The professional development plans incorporated findings from APP exit interviews at the University of Maryland Medical Center highlighting the following retention issues:1

- Length of time for credentialing

- Role clarity

- Inadequate clinical orientation

- Feelings of clinical incompetence

- Feelings of isolation

With the instillation of APP leadership, the team created a comprehensive APP program. The Hospital Medicine APP program at EUHM includes the following components:

- APP representation at monthly clinical operation meetings and quarterly education council meetings to ensure that APP competency and regulatory issues are always represented.

- Orientation personally tailored to the APP’s level of clinical expertise, with a post-orientation meeting with leadership and remediation, if needed.

- APP incentives to teach NP or PA students, conduct in-services, join committees, or participate in other leadership opportunities.

- APPs invited to attend and/or present at all divisional small and large group learning opportunities (e.g., Grand Rounds, Lunch and Learn, Journal Club).

- APPs allocated time and space to meet and discuss practice issues.

- Newly developed Mini-Hospitalist Academy, which offers monthly workshops to all hospitalist physicians and APPs, from novice to expert.

- Dedicated APP Ongoing Professional Performance Evaluation (OPPE) program.

- In addition to the annual monetary support offered for educational opportunities, the division offers an annual Faculty Development Award. This award is by application for eligible educational opportunities; APPs are welcome to apply and have consistently been awarded support to pursue myriad opportunities.

This successful APP-physician collaboration is driven by a committed group of professionals who are sensitive to the shifting healthcare paradigm. Our APPs and physicians are constantly adapting their practice so that our collaboration is safe, evidence-based, and professionally fulfilling. TH

Yvonne Brown, DNP, MSN, ACNP-C, FNP-C, nurse practitioner, lead advanced practice provider, Division of Hospital Medicine, Emory Healthcare, Emory University Hospital Midtown, Atlanta

Reference

1. Bahouth MN, Esposito-Herr MB. Orientation program for hospital-based nurse practitioners. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2009;20(1):82-90.

Better Reporting Needed to Accurately Estimate Medical Error as Cause of Death in U.S.

Clinical question: What is the contribution of hospital-based medical errors to national mortality in the U.S. compared to other causes listed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)?

Background: Medical error can contribute to patient mortality. Currently, the annual list of the most common causes of death in the U.S. is compiled by the CDC using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes on death certificates. Deaths caused by errors are unmeasured because medical errors are not included in the death certificate.

Study design: Analysis of existing literature on medical errors.

Setting: U.S. hospitals.

Synopsis: Findings of four studies on U.S. death rates from medical errors published between 2000 and 2008 were synthesized and extrapolated to the total number of U.S. hospital admissions in 2013. This resulted in a mean rate of death from medical errors of 251,454 per year, which is much higher than the annual incidence of 44,000–98,000 deaths published in the 1999 Institute of Medicine report. Comparing these data to the CDC ranking makes medical errors the third-leading cause of death in the U.S.

Although the accuracy of this result is limited to inpatient deaths and as the authors extrapolated the data from other studies, the number is still staggering and highlights the need for systematic measurement of the problem. One simple solution for this could be to have an extra field on the death certificate asking whether a preventable complication stemming from the patient’s medical care contributed to the death.

Bottom line: Medical error as the estimated third-leading cause of the death in the U.S. remains under-recognized, underappreciated, and highly unmeasured.

Citation: Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

Short Take

Isolating C. Difficile Carriers Decreases Hospital-Acquired C. Difficile Infections

In a nonblinded time-series analysis, screening all patients for asymptomatic C. diff carrier status and isolating carriers reduced rates of hospital-acquired C. diff, preventing 62.4% of expected cases.

Citation: Longtin Y, Paquet-Bolduc B, Gilca R, et al. Effect of detecting and isolating Clostridium difficile carriers at hospital admission on the incidence of C difficile infections: a quasi-experimental controlled study. JAMA Inter Med. 2016;176(6):796¬-804.

Clinical question: What is the contribution of hospital-based medical errors to national mortality in the U.S. compared to other causes listed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)?

Background: Medical error can contribute to patient mortality. Currently, the annual list of the most common causes of death in the U.S. is compiled by the CDC using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes on death certificates. Deaths caused by errors are unmeasured because medical errors are not included in the death certificate.

Study design: Analysis of existing literature on medical errors.

Setting: U.S. hospitals.

Synopsis: Findings of four studies on U.S. death rates from medical errors published between 2000 and 2008 were synthesized and extrapolated to the total number of U.S. hospital admissions in 2013. This resulted in a mean rate of death from medical errors of 251,454 per year, which is much higher than the annual incidence of 44,000–98,000 deaths published in the 1999 Institute of Medicine report. Comparing these data to the CDC ranking makes medical errors the third-leading cause of death in the U.S.

Although the accuracy of this result is limited to inpatient deaths and as the authors extrapolated the data from other studies, the number is still staggering and highlights the need for systematic measurement of the problem. One simple solution for this could be to have an extra field on the death certificate asking whether a preventable complication stemming from the patient’s medical care contributed to the death.

Bottom line: Medical error as the estimated third-leading cause of the death in the U.S. remains under-recognized, underappreciated, and highly unmeasured.

Citation: Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

Short Take

Isolating C. Difficile Carriers Decreases Hospital-Acquired C. Difficile Infections

In a nonblinded time-series analysis, screening all patients for asymptomatic C. diff carrier status and isolating carriers reduced rates of hospital-acquired C. diff, preventing 62.4% of expected cases.

Citation: Longtin Y, Paquet-Bolduc B, Gilca R, et al. Effect of detecting and isolating Clostridium difficile carriers at hospital admission on the incidence of C difficile infections: a quasi-experimental controlled study. JAMA Inter Med. 2016;176(6):796¬-804.

Clinical question: What is the contribution of hospital-based medical errors to national mortality in the U.S. compared to other causes listed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)?

Background: Medical error can contribute to patient mortality. Currently, the annual list of the most common causes of death in the U.S. is compiled by the CDC using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes on death certificates. Deaths caused by errors are unmeasured because medical errors are not included in the death certificate.

Study design: Analysis of existing literature on medical errors.

Setting: U.S. hospitals.

Synopsis: Findings of four studies on U.S. death rates from medical errors published between 2000 and 2008 were synthesized and extrapolated to the total number of U.S. hospital admissions in 2013. This resulted in a mean rate of death from medical errors of 251,454 per year, which is much higher than the annual incidence of 44,000–98,000 deaths published in the 1999 Institute of Medicine report. Comparing these data to the CDC ranking makes medical errors the third-leading cause of death in the U.S.

Although the accuracy of this result is limited to inpatient deaths and as the authors extrapolated the data from other studies, the number is still staggering and highlights the need for systematic measurement of the problem. One simple solution for this could be to have an extra field on the death certificate asking whether a preventable complication stemming from the patient’s medical care contributed to the death.

Bottom line: Medical error as the estimated third-leading cause of the death in the U.S. remains under-recognized, underappreciated, and highly unmeasured.

Citation: Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

Short Take

Isolating C. Difficile Carriers Decreases Hospital-Acquired C. Difficile Infections

In a nonblinded time-series analysis, screening all patients for asymptomatic C. diff carrier status and isolating carriers reduced rates of hospital-acquired C. diff, preventing 62.4% of expected cases.

Citation: Longtin Y, Paquet-Bolduc B, Gilca R, et al. Effect of detecting and isolating Clostridium difficile carriers at hospital admission on the incidence of C difficile infections: a quasi-experimental controlled study. JAMA Inter Med. 2016;176(6):796¬-804.

Hospital Medicine's Movers and Shakers – July 2016

Several prominent hospitalist leaders have been named to Modern Healthcare magazine’s “50 Most Influential Physician Executives and Leaders” for 2016. Among them are Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, MHM, a pediatric hospitalist as well as CMO and deputy administrator for innovation and quality at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS); Vivek Murthy, MD, MBA, a hospitalist and the current U.S. Surgeon General; Lynn Massingale, MD, co-founder and executive chairman of the hospitalist staffing firm TeamHealth; and Robert M. Wachter, MD, MHM, a national hospitalist leader, professor, and interim chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and a founder of the hospitalist movement.

Susan George, MD, SFHM, recently received the Katharine F. Erskine Award from the YWCA in Worcester, Mass. Dr. George served as an internal medicine physician at Saint Vincent Hospital in Worcester for a total of 20 years and as hospitalist medical director there from 2007 until this year, when she left to go into private practice. Dr. George still teaches at the University of Massachusetts Medical School as an associate professor of medicine. The award is named for Katharine F. Erskine, a former YWCA president and women’s advocate since before the turn of the 20th century.

Alanna Small, MD, was recently named deputy chief of staff for Physician Services at Samuel Simmonds Memorial Hospital in Barrow, Alaska. Prior to this role, Dr. Small served as a hospitalist at the Alaska Native Medical Center in Anchorage.

Business Moves

Envision also announced its planned acquisition of Emergency Physicians Medical Group (EPMG), based in Ann Arbor, Mich., a private emergency and hospital medicine staffing firm serving the Midwestern United States since 1976.

Michael O’Neal is a freelance writer in New York City.

Several prominent hospitalist leaders have been named to Modern Healthcare magazine’s “50 Most Influential Physician Executives and Leaders” for 2016. Among them are Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, MHM, a pediatric hospitalist as well as CMO and deputy administrator for innovation and quality at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS); Vivek Murthy, MD, MBA, a hospitalist and the current U.S. Surgeon General; Lynn Massingale, MD, co-founder and executive chairman of the hospitalist staffing firm TeamHealth; and Robert M. Wachter, MD, MHM, a national hospitalist leader, professor, and interim chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and a founder of the hospitalist movement.

Susan George, MD, SFHM, recently received the Katharine F. Erskine Award from the YWCA in Worcester, Mass. Dr. George served as an internal medicine physician at Saint Vincent Hospital in Worcester for a total of 20 years and as hospitalist medical director there from 2007 until this year, when she left to go into private practice. Dr. George still teaches at the University of Massachusetts Medical School as an associate professor of medicine. The award is named for Katharine F. Erskine, a former YWCA president and women’s advocate since before the turn of the 20th century.

Alanna Small, MD, was recently named deputy chief of staff for Physician Services at Samuel Simmonds Memorial Hospital in Barrow, Alaska. Prior to this role, Dr. Small served as a hospitalist at the Alaska Native Medical Center in Anchorage.

Business Moves

Envision also announced its planned acquisition of Emergency Physicians Medical Group (EPMG), based in Ann Arbor, Mich., a private emergency and hospital medicine staffing firm serving the Midwestern United States since 1976.

Michael O’Neal is a freelance writer in New York City.

Several prominent hospitalist leaders have been named to Modern Healthcare magazine’s “50 Most Influential Physician Executives and Leaders” for 2016. Among them are Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, MHM, a pediatric hospitalist as well as CMO and deputy administrator for innovation and quality at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS); Vivek Murthy, MD, MBA, a hospitalist and the current U.S. Surgeon General; Lynn Massingale, MD, co-founder and executive chairman of the hospitalist staffing firm TeamHealth; and Robert M. Wachter, MD, MHM, a national hospitalist leader, professor, and interim chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and a founder of the hospitalist movement.

Susan George, MD, SFHM, recently received the Katharine F. Erskine Award from the YWCA in Worcester, Mass. Dr. George served as an internal medicine physician at Saint Vincent Hospital in Worcester for a total of 20 years and as hospitalist medical director there from 2007 until this year, when she left to go into private practice. Dr. George still teaches at the University of Massachusetts Medical School as an associate professor of medicine. The award is named for Katharine F. Erskine, a former YWCA president and women’s advocate since before the turn of the 20th century.

Alanna Small, MD, was recently named deputy chief of staff for Physician Services at Samuel Simmonds Memorial Hospital in Barrow, Alaska. Prior to this role, Dr. Small served as a hospitalist at the Alaska Native Medical Center in Anchorage.

Business Moves

Envision also announced its planned acquisition of Emergency Physicians Medical Group (EPMG), based in Ann Arbor, Mich., a private emergency and hospital medicine staffing firm serving the Midwestern United States since 1976.

Michael O’Neal is a freelance writer in New York City.

Hospital Admission, Stroke Clinic Follow-up Improve Outcomes for Patients with Transient Ischemic Attack, Minor Ischemic Stroke

Clinical question: How do guideline-based care and outcomes of patients with transient ischemic attack (TIA) and minor ischemic stroke differ among patients admitted to the hospital and discharged from the ED, as well as in those referred versus not referred to stroke prevention clinics following discharge?

Background: Previous research demonstrated that urgent outpatient management strategies for patients with TIA and minor ischemic stroke are superior to standard outpatient care. However, there is less known about how outpatient stroke care compares to inpatient care in terms of outcomes, rapid risk factor identification/modification, and initiation of antithrombotic therapy.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: EDs of acute-care hospitals in Ontario, Canada.

Synopsis: Using the Ontario Stroke Registry, 8,540 patients seen in the ED with TIA or minor ischemic stroke were identified. The use of guideline-based interventions was highest in admitted patients, followed by patients discharged from the ED with stroke clinic follow-up, followed by patients discharged without follow-up. There was no significant difference in one-year mortality between admitted and discharged patients when adjusted for age, sex, and comorbid conditions (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.92–1.34). However, stroke clinic referral was associated with a lower risk of one-year mortality compared with those discharged without follow-up (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.38–0.64).

Limitations of this study include that it was carried out only in Ontario, where there is a universal healthcare system, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, patient information was limited to what was available through the registry, which may mean there were other unmeasurable differences among groups.

Bottom line: Admitted patients with TIA or minor ischemic stroke are more likely to receive guideline-based therapy, and among patients discharged from the ED, referral to stroke clinic improves outcomes, including one-year mortality.

Citation: Kapral MK, Hall R, Fang J, et al. Association between hospitalization and care after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Neurology. 2016;86(17):1582-1589.

Clinical question: How do guideline-based care and outcomes of patients with transient ischemic attack (TIA) and minor ischemic stroke differ among patients admitted to the hospital and discharged from the ED, as well as in those referred versus not referred to stroke prevention clinics following discharge?

Background: Previous research demonstrated that urgent outpatient management strategies for patients with TIA and minor ischemic stroke are superior to standard outpatient care. However, there is less known about how outpatient stroke care compares to inpatient care in terms of outcomes, rapid risk factor identification/modification, and initiation of antithrombotic therapy.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: EDs of acute-care hospitals in Ontario, Canada.

Synopsis: Using the Ontario Stroke Registry, 8,540 patients seen in the ED with TIA or minor ischemic stroke were identified. The use of guideline-based interventions was highest in admitted patients, followed by patients discharged from the ED with stroke clinic follow-up, followed by patients discharged without follow-up. There was no significant difference in one-year mortality between admitted and discharged patients when adjusted for age, sex, and comorbid conditions (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.92–1.34). However, stroke clinic referral was associated with a lower risk of one-year mortality compared with those discharged without follow-up (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.38–0.64).

Limitations of this study include that it was carried out only in Ontario, where there is a universal healthcare system, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, patient information was limited to what was available through the registry, which may mean there were other unmeasurable differences among groups.

Bottom line: Admitted patients with TIA or minor ischemic stroke are more likely to receive guideline-based therapy, and among patients discharged from the ED, referral to stroke clinic improves outcomes, including one-year mortality.

Citation: Kapral MK, Hall R, Fang J, et al. Association between hospitalization and care after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Neurology. 2016;86(17):1582-1589.

Clinical question: How do guideline-based care and outcomes of patients with transient ischemic attack (TIA) and minor ischemic stroke differ among patients admitted to the hospital and discharged from the ED, as well as in those referred versus not referred to stroke prevention clinics following discharge?

Background: Previous research demonstrated that urgent outpatient management strategies for patients with TIA and minor ischemic stroke are superior to standard outpatient care. However, there is less known about how outpatient stroke care compares to inpatient care in terms of outcomes, rapid risk factor identification/modification, and initiation of antithrombotic therapy.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: EDs of acute-care hospitals in Ontario, Canada.

Synopsis: Using the Ontario Stroke Registry, 8,540 patients seen in the ED with TIA or minor ischemic stroke were identified. The use of guideline-based interventions was highest in admitted patients, followed by patients discharged from the ED with stroke clinic follow-up, followed by patients discharged without follow-up. There was no significant difference in one-year mortality between admitted and discharged patients when adjusted for age, sex, and comorbid conditions (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.92–1.34). However, stroke clinic referral was associated with a lower risk of one-year mortality compared with those discharged without follow-up (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.38–0.64).

Limitations of this study include that it was carried out only in Ontario, where there is a universal healthcare system, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, patient information was limited to what was available through the registry, which may mean there were other unmeasurable differences among groups.

Bottom line: Admitted patients with TIA or minor ischemic stroke are more likely to receive guideline-based therapy, and among patients discharged from the ED, referral to stroke clinic improves outcomes, including one-year mortality.

Citation: Kapral MK, Hall R, Fang J, et al. Association between hospitalization and care after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Neurology. 2016;86(17):1582-1589.

New Framework for Quality Improvement

Improving healthcare means taking an efficacious intervention from one setting and effectively implementing it somewhere else.

“It is this key element of adapting what works to new settings that sets improvement in contrast to clinical research. The study of these complex systems will therefore require different methods of inquiry,” according to a recently published paper in the International Journal for Quality in Health Care titled “How Do We Learn about Improving Health Care: A Call for a New Epistemological Paradigm.”

“In biomedical sciences, we’re used to a golden standard that is the randomized controlled trial,” says lead author M. Rashad Massoud, MD, MPH, senior vice president, Quality & Performance Institute, University Research Co., LLC. “Of course, the nature of what we’re trying to do does not lend itself to that type of evaluation. It means that we can’t have an either/or situation where we either continue as we are or we go to flip side—which then inhibits the very nature of improvement from taking place, which is very contextual, very much adaptive in nature. There has to be a happy medium in between, where we can continue to do the improvements without inhibiting them and, at the same time, improve the rigor of the work.”

A new framework for how we learn about improvement could help in the design, implementation, and evaluation of QI by strengthening attribution and better understanding variations in effectiveness in different contexts, the authors assert.

“This will in turn allow us to understand which activities, under which conditions, are most effective at achieving sustained results in health outcomes,” the authors write.

In seeking a new framework for learning about QI, the authors suggest that the following questions must be considered:

- Did the improvements work?

- Why did they work?

- How do we know that the results can be attributed to the changes made?

- How can we replicate them?

“I think hospitalists would probably welcome the idea that not only can they measure improvements in the work that they’re doing but can actually do that in a more rigorous way and actually attribute the results they’re getting to the work that they’re doing,” Dr. Massoud says.

Reference

- Massoud MR, Barry D, Murphy A, Albrecht Y, Sax S, Parchman M. How do we learn about improving health care: a call for a new epistemological paradigm. Intl J Quality Health Care. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzw039.

Improving healthcare means taking an efficacious intervention from one setting and effectively implementing it somewhere else.

“It is this key element of adapting what works to new settings that sets improvement in contrast to clinical research. The study of these complex systems will therefore require different methods of inquiry,” according to a recently published paper in the International Journal for Quality in Health Care titled “How Do We Learn about Improving Health Care: A Call for a New Epistemological Paradigm.”

“In biomedical sciences, we’re used to a golden standard that is the randomized controlled trial,” says lead author M. Rashad Massoud, MD, MPH, senior vice president, Quality & Performance Institute, University Research Co., LLC. “Of course, the nature of what we’re trying to do does not lend itself to that type of evaluation. It means that we can’t have an either/or situation where we either continue as we are or we go to flip side—which then inhibits the very nature of improvement from taking place, which is very contextual, very much adaptive in nature. There has to be a happy medium in between, where we can continue to do the improvements without inhibiting them and, at the same time, improve the rigor of the work.”

A new framework for how we learn about improvement could help in the design, implementation, and evaluation of QI by strengthening attribution and better understanding variations in effectiveness in different contexts, the authors assert.

“This will in turn allow us to understand which activities, under which conditions, are most effective at achieving sustained results in health outcomes,” the authors write.

In seeking a new framework for learning about QI, the authors suggest that the following questions must be considered:

- Did the improvements work?

- Why did they work?

- How do we know that the results can be attributed to the changes made?

- How can we replicate them?

“I think hospitalists would probably welcome the idea that not only can they measure improvements in the work that they’re doing but can actually do that in a more rigorous way and actually attribute the results they’re getting to the work that they’re doing,” Dr. Massoud says.

Reference

- Massoud MR, Barry D, Murphy A, Albrecht Y, Sax S, Parchman M. How do we learn about improving health care: a call for a new epistemological paradigm. Intl J Quality Health Care. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzw039.

Improving healthcare means taking an efficacious intervention from one setting and effectively implementing it somewhere else.

“It is this key element of adapting what works to new settings that sets improvement in contrast to clinical research. The study of these complex systems will therefore require different methods of inquiry,” according to a recently published paper in the International Journal for Quality in Health Care titled “How Do We Learn about Improving Health Care: A Call for a New Epistemological Paradigm.”

“In biomedical sciences, we’re used to a golden standard that is the randomized controlled trial,” says lead author M. Rashad Massoud, MD, MPH, senior vice president, Quality & Performance Institute, University Research Co., LLC. “Of course, the nature of what we’re trying to do does not lend itself to that type of evaluation. It means that we can’t have an either/or situation where we either continue as we are or we go to flip side—which then inhibits the very nature of improvement from taking place, which is very contextual, very much adaptive in nature. There has to be a happy medium in between, where we can continue to do the improvements without inhibiting them and, at the same time, improve the rigor of the work.”

A new framework for how we learn about improvement could help in the design, implementation, and evaluation of QI by strengthening attribution and better understanding variations in effectiveness in different contexts, the authors assert.

“This will in turn allow us to understand which activities, under which conditions, are most effective at achieving sustained results in health outcomes,” the authors write.

In seeking a new framework for learning about QI, the authors suggest that the following questions must be considered:

- Did the improvements work?

- Why did they work?

- How do we know that the results can be attributed to the changes made?