User login

LISTEN NOW: Ron Greeno Discusses Key Policy Issues Facing Hospitalists

LISTEN NOW: HM15 Course Director Explains How You Can Maximize SHM's Annual Meeting

LISTEN NOW: Highlights of the February 2015 Issue of The Hospitalist

[audio mp3="http://www.the-hospitalist.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/2015-February-Hospitalist-Highlights.mp3"][/audio]

[audio mp3="http://www.the-hospitalist.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/2015-February-Hospitalist-Highlights.mp3"][/audio]

[audio mp3="http://www.the-hospitalist.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/2015-February-Hospitalist-Highlights.mp3"][/audio]

Dr. Peter Pronovost to Speak to Hospitalists About Healthcare Quality at HM15

Type the name Peter Pronovost into Google and try to make it past the “n” before the word “checklist” pops up. That’s because Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, senior vice president for patient safety and quality at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, is the “checklist doctor,” widely known for a five-step checklist designed to reduce the incidence of central-line infections and credited by SHM with saving thousands of lives. He was named one of the 100 Most Influential People in the World by Time magazine, and he co-authored a book, “Safe Patients, Smart Hospitals: How One Doctor’s Checklist Can Help Us Change Health Care from the Inside Out.”

Dr. Pronovost is one of three keynote speakers slated to offer their wisdom and insights to thousands of hospitalists attending HM15, scheduled for March 29-April 1 at the Gaylord National Resort and Convention Center in National Harbor, Md.

And before you ask—yes, he smiles when people call him the “checklist guy.”

“These catheter infections, just to give you an example, they used to kill as many people as breast or prostate cancer in the U.S. This isn’t some trivial public health problem,” Dr. Pronovost says. “This is a public health problem the size of breast or prostate cancer. And we virtually eliminated it, [which is] pretty remarkable about what the potential of this approach is in healthcare. That is just one harm. We have a lot of other things to go still.”

Dr. Pronovost, director of the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality at Johns Hopkins, has titled his HM15 talk, “Taking Quality to the Next Level.” One of his main beliefs is that intrinsically motivated efforts are much more successful than payment carrots or sticks wielded by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

—Dr. Pronovost

“We tap into this incredibly rich and passionate juice of improvement work,” he says of intrinsic motivation. “Whether it’s through a church or through a club, all of us have felt that when you connect to a community, the energy and the passion that that unleashes. Hospitalists have the wisdom to know what to do and how to do it right, and it’s just so much more effective when you tap into intrinsic motivation.”

His famed checklist was a great start to that, but he says more needs to be done. That work looked at eliminating a single hospital-acquired condition. Now, Dr. Pronovost has reframed the question: Can we eliminate all harms? What if hospitals listed out all harms and then gave each a checklist?

“It quickly gets to well beyond the potential of human memory, because there are about 150 things we have to do,” he says. “So I’m going to be showcasing a new app that we made that gives you real-time compliance with all those checklists. If I’m missing any one of those 150 things, there’s a red box next to the patient’s name, and all I have to go do is click on the red box and see what I’m missing.”

Dr. Pronovost sees that approach as a fundamental shift in how safety is viewed. It can’t be based on “heroism,” when someone remembers to remember something; rather, it needs to be rooted in properly designed systems that leverage technology to achieve desired results.

To look at it another way, consider a conversation Dr. Pronovost had with friends in engineering who previously worked on missions launching satellites into space.

“They said to me, ‘Peter, you guys are thinking about this backwards in healthcare. If we had to put a mission up…it can blow up for 12 reasons. It didn’t blow up for reason No. 1—call it a bloodstream infection—but it did blow up for reasons 2 through 12, do you think we’d be patting ourselves on the back [because] that No. 1 reason didn’t get us?”

In that vein, Dr. Pronovost believes that hospitalists can be a lynchpin in what he calls “change leadership.”

“Hospitalists have an essential role in improving the quality and safety of care for hospitalized patients and for transitions,” he says. “I would say that between quality and safety, and the patient experience as a core competency of a hospitalist role, healthcare organizations need to actively engage them, including providing support for their time to lead these efforts.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Type the name Peter Pronovost into Google and try to make it past the “n” before the word “checklist” pops up. That’s because Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, senior vice president for patient safety and quality at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, is the “checklist doctor,” widely known for a five-step checklist designed to reduce the incidence of central-line infections and credited by SHM with saving thousands of lives. He was named one of the 100 Most Influential People in the World by Time magazine, and he co-authored a book, “Safe Patients, Smart Hospitals: How One Doctor’s Checklist Can Help Us Change Health Care from the Inside Out.”

Dr. Pronovost is one of three keynote speakers slated to offer their wisdom and insights to thousands of hospitalists attending HM15, scheduled for March 29-April 1 at the Gaylord National Resort and Convention Center in National Harbor, Md.

And before you ask—yes, he smiles when people call him the “checklist guy.”

“These catheter infections, just to give you an example, they used to kill as many people as breast or prostate cancer in the U.S. This isn’t some trivial public health problem,” Dr. Pronovost says. “This is a public health problem the size of breast or prostate cancer. And we virtually eliminated it, [which is] pretty remarkable about what the potential of this approach is in healthcare. That is just one harm. We have a lot of other things to go still.”

Dr. Pronovost, director of the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality at Johns Hopkins, has titled his HM15 talk, “Taking Quality to the Next Level.” One of his main beliefs is that intrinsically motivated efforts are much more successful than payment carrots or sticks wielded by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

—Dr. Pronovost

“We tap into this incredibly rich and passionate juice of improvement work,” he says of intrinsic motivation. “Whether it’s through a church or through a club, all of us have felt that when you connect to a community, the energy and the passion that that unleashes. Hospitalists have the wisdom to know what to do and how to do it right, and it’s just so much more effective when you tap into intrinsic motivation.”

His famed checklist was a great start to that, but he says more needs to be done. That work looked at eliminating a single hospital-acquired condition. Now, Dr. Pronovost has reframed the question: Can we eliminate all harms? What if hospitals listed out all harms and then gave each a checklist?

“It quickly gets to well beyond the potential of human memory, because there are about 150 things we have to do,” he says. “So I’m going to be showcasing a new app that we made that gives you real-time compliance with all those checklists. If I’m missing any one of those 150 things, there’s a red box next to the patient’s name, and all I have to go do is click on the red box and see what I’m missing.”

Dr. Pronovost sees that approach as a fundamental shift in how safety is viewed. It can’t be based on “heroism,” when someone remembers to remember something; rather, it needs to be rooted in properly designed systems that leverage technology to achieve desired results.

To look at it another way, consider a conversation Dr. Pronovost had with friends in engineering who previously worked on missions launching satellites into space.

“They said to me, ‘Peter, you guys are thinking about this backwards in healthcare. If we had to put a mission up…it can blow up for 12 reasons. It didn’t blow up for reason No. 1—call it a bloodstream infection—but it did blow up for reasons 2 through 12, do you think we’d be patting ourselves on the back [because] that No. 1 reason didn’t get us?”

In that vein, Dr. Pronovost believes that hospitalists can be a lynchpin in what he calls “change leadership.”

“Hospitalists have an essential role in improving the quality and safety of care for hospitalized patients and for transitions,” he says. “I would say that between quality and safety, and the patient experience as a core competency of a hospitalist role, healthcare organizations need to actively engage them, including providing support for their time to lead these efforts.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Type the name Peter Pronovost into Google and try to make it past the “n” before the word “checklist” pops up. That’s because Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, senior vice president for patient safety and quality at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, is the “checklist doctor,” widely known for a five-step checklist designed to reduce the incidence of central-line infections and credited by SHM with saving thousands of lives. He was named one of the 100 Most Influential People in the World by Time magazine, and he co-authored a book, “Safe Patients, Smart Hospitals: How One Doctor’s Checklist Can Help Us Change Health Care from the Inside Out.”

Dr. Pronovost is one of three keynote speakers slated to offer their wisdom and insights to thousands of hospitalists attending HM15, scheduled for March 29-April 1 at the Gaylord National Resort and Convention Center in National Harbor, Md.

And before you ask—yes, he smiles when people call him the “checklist guy.”

“These catheter infections, just to give you an example, they used to kill as many people as breast or prostate cancer in the U.S. This isn’t some trivial public health problem,” Dr. Pronovost says. “This is a public health problem the size of breast or prostate cancer. And we virtually eliminated it, [which is] pretty remarkable about what the potential of this approach is in healthcare. That is just one harm. We have a lot of other things to go still.”

Dr. Pronovost, director of the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality at Johns Hopkins, has titled his HM15 talk, “Taking Quality to the Next Level.” One of his main beliefs is that intrinsically motivated efforts are much more successful than payment carrots or sticks wielded by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

—Dr. Pronovost

“We tap into this incredibly rich and passionate juice of improvement work,” he says of intrinsic motivation. “Whether it’s through a church or through a club, all of us have felt that when you connect to a community, the energy and the passion that that unleashes. Hospitalists have the wisdom to know what to do and how to do it right, and it’s just so much more effective when you tap into intrinsic motivation.”

His famed checklist was a great start to that, but he says more needs to be done. That work looked at eliminating a single hospital-acquired condition. Now, Dr. Pronovost has reframed the question: Can we eliminate all harms? What if hospitals listed out all harms and then gave each a checklist?

“It quickly gets to well beyond the potential of human memory, because there are about 150 things we have to do,” he says. “So I’m going to be showcasing a new app that we made that gives you real-time compliance with all those checklists. If I’m missing any one of those 150 things, there’s a red box next to the patient’s name, and all I have to go do is click on the red box and see what I’m missing.”

Dr. Pronovost sees that approach as a fundamental shift in how safety is viewed. It can’t be based on “heroism,” when someone remembers to remember something; rather, it needs to be rooted in properly designed systems that leverage technology to achieve desired results.

To look at it another way, consider a conversation Dr. Pronovost had with friends in engineering who previously worked on missions launching satellites into space.

“They said to me, ‘Peter, you guys are thinking about this backwards in healthcare. If we had to put a mission up…it can blow up for 12 reasons. It didn’t blow up for reason No. 1—call it a bloodstream infection—but it did blow up for reasons 2 through 12, do you think we’d be patting ourselves on the back [because] that No. 1 reason didn’t get us?”

In that vein, Dr. Pronovost believes that hospitalists can be a lynchpin in what he calls “change leadership.”

“Hospitalists have an essential role in improving the quality and safety of care for hospitalized patients and for transitions,” he says. “I would say that between quality and safety, and the patient experience as a core competency of a hospitalist role, healthcare organizations need to actively engage them, including providing support for their time to lead these efforts.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

LISTEN NOW: Hospitalist Chris Spoja discusses his decision to pursue a MMM degree

Listen to Chris Spoja, MD, a hospitalist with Sound Physicians, explain his decision to pursue a Master’s of Medical Management (MMM) degree.

Listen to Chris Spoja, MD, a hospitalist with Sound Physicians, explain his decision to pursue a Master’s of Medical Management (MMM) degree.

Listen to Chris Spoja, MD, a hospitalist with Sound Physicians, explain his decision to pursue a Master’s of Medical Management (MMM) degree.

Movers and Shakers in Hospital Medicine, January 2015

This month, The Hospitalist features new appointments, promotions, awards, and achievements of hospital medicine physicians and healthcare industry professionals.

Douglas Carlson, MD, FAAP, SFHM, has been appointed professor and chair of the department of pediatrics at Southern Illinois University in Springfield, Ill. Dr. Carlson is a pediatric hospitalist who served as director of the pediatric hospitalist medicine division at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo. Dr. Carlson currently serves as co-chair of the SHM Pediatric Committee, as well as Workforce Taskforce Leader for the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Leadership Committee and chair of the Pediatric Hospital Medicine National Conference Planning Committee.

Howard Epstein, MD, FHM, has been appointed executive vice president and chief medical officer at PreferredOne, a health services and insurance provider based in Golden Valley, Minn. Dr. Epstein comes to PreferredOne from the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) in Bloomington, where he served as chief health systems officer. An SHM board member, Dr. Epstein previously helped found the hospital medicine and palliative care programs at Regions Hospital and HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

Les Hall, MD, has been appointed executive dean of the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, as well as CEO of Palmetto Health-USC Medical Group in Columbia, S.C. Prior to his role at the University of South Carolina, Dr. Hall served as associate dean for clinical affairs at the University of Missouri School of Medicine and chief medical officer of the University of Missouri Health System in Columbia, Mo. Dr. Hall is a practicing hospitalist and an active member of SHM, and he has continued to care for patients throughout his career as a healthcare leader.

• Liesbet Jansen, MD, was awarded the 2014 Dr. Alexander MacIntyre Award of Excellence by the Alliston (Ontario, Canada) and Area Physician Recruitment Committee for demonstrating excellence in medical practice and commitment to the local community. Dr. Jansen serves as a hospitalist and chief of family medicine at Stevenson Memorial Hospital in Alliston, Ontario, Canada.

Hans Jeppesen, MD, is the new chief of hospital medicine at North Shore Medical Center (NSMC) in Salem, Mass. In addition to overseeing the hospitalist team at NSMC, Dr. Jeppesen will also be responsible for caring for inpatients at NSMC Salem and Union (Lynn, Mass.) Hospitals. Before joining NSMC, Dr. Jeppesen served as chief of hospitalist services at Cambridge Health Alliance in Cambridge, Mass.

Todd Kislak is the new chief development officer for Hospitalists Now, Inc. (HNI), a national physician management company based in Austin, Texas. In his new role, Kislak is responsible for sales and business development as well as marketing for HNI. Kislak formerly served as vice president of marketing and development for IPC The Hospitalist Company, based in North Hollywood, Calif.

Kelly London, PA-C, has been awarded Non-Physician Hospitalist of the Year by the Maryland chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine. London is the first nonphysician provider to receive the award, and was nominated along with other qualified nurse practitioners and physician assistants throughout Maryland. London serves on the hospitalist team at Anne Arundel Medical Center, managed by MDICS (Physicians Inpatient Care Specialists), in Annapolis, Md.

Jennifer Miraglia is the new executive director for the Chicago region of IPC The Hospitalist Company, a national hospital medicine management company based in North Hollywood, Calif. Before coming to IPC, Miraglia worked as regional vice president of operations for RehabCare, a division of Kindred Healthcare based in Louisville, Ky. IPC manages hospitalist services in over 400 hospitals across the United States.

Steven Pantilat, MD, MHM, FAAHPM, recently was awarded the Ritz E. Heerman Memorial Award by the California Hospital Association Board of Trustees for his work on improving the quality of palliative care services in California. Dr. Pantilat is the founding director of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Palliative Care Program, and director of the UCSF Palliative Care Leadership Center. Dr. Pantilat is a past president of SHM and currently works as a professor of clinical medicine at UCSF.

Business Moves

• North Hollywood, Calif.-based IPC The Hospitalist Company has acquired the following practices: Hospital Practice Associates, Inc. (HPA), in Jacksonville, Fla.; John N. Campbell, MD, PC, in Grand Rapids, Mich.; Comprehensive Health Solutions, in Newtown Square, Penn.; Midland Hospitalists PLC in Midland, Mich.; and Clyo Internal Medicine in Dayton, Ohio. IPC is a national hospitalist management company serving over 400 hospitals and 1,200 post-acute care facilities across the country.

• The Greenville, S.C.-based Ob Hospitalist Group (OBHG) recently received the following honors: voted one of the Inc. 5,000 Fastest Growing Private Companies in America for the second year running for a growth rate of 239% since 2011; voted one of the Best Places to Work in South Carolina by the South Carolina Chamber of Commerce and SC Biz News, for the second consecutive year; listed on the Roaring Twenties List from SC Biz News as one of the 40 highest performing companies in South Carolina; and included on South Carolina’s 25 Fastest-Growing Companies list for the third year running. OBHG has been providing OB/GYN hospitalist services across the country since 2006.

• The OSF St. Elizabeth Medical Center in Ottawa, Ill., has just introduced a new hospitalist program at its 99-bed acute care hospital. Robert B. Maguire, MD, a veteran Ottawa doctor, has been chosen to lead the new hospitalist program as medical director. OSF St. Elizabeth will continue to recruit additional hospitalists to the new program with the help of 24ON Physicians/In Compass Health, Inc., a hospitalist staffing firm based in Alpharetta, Ga.

• Penn State Hershey Children’s Hospital is now providing pediatric care at Moses Taylor Hospital in Scranton, Penn. Moses Taylor Hospital is a 217-bed acute care facility operated by Commonwealth Health, the largest healthcare system in northern Pennsylvania, which consists of six hospitals and dozens of post-acute care practices and facilities.

• TeamHealth, a national physician management company based in Knoxville, Tenn., announced its acquisition of Premier Physician Services, Inc., based in Dayton, Ohio. Premier consists of eight hospitalist programs as well as 45 emergency medicine programs, 15 correctional care programs, and 15 occupational medicine programs, which TeamHealth will now oversee. TeamHealth provides physician management and healthcare staffing in 47 states.

This month, The Hospitalist features new appointments, promotions, awards, and achievements of hospital medicine physicians and healthcare industry professionals.

Douglas Carlson, MD, FAAP, SFHM, has been appointed professor and chair of the department of pediatrics at Southern Illinois University in Springfield, Ill. Dr. Carlson is a pediatric hospitalist who served as director of the pediatric hospitalist medicine division at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo. Dr. Carlson currently serves as co-chair of the SHM Pediatric Committee, as well as Workforce Taskforce Leader for the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Leadership Committee and chair of the Pediatric Hospital Medicine National Conference Planning Committee.

Howard Epstein, MD, FHM, has been appointed executive vice president and chief medical officer at PreferredOne, a health services and insurance provider based in Golden Valley, Minn. Dr. Epstein comes to PreferredOne from the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) in Bloomington, where he served as chief health systems officer. An SHM board member, Dr. Epstein previously helped found the hospital medicine and palliative care programs at Regions Hospital and HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

Les Hall, MD, has been appointed executive dean of the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, as well as CEO of Palmetto Health-USC Medical Group in Columbia, S.C. Prior to his role at the University of South Carolina, Dr. Hall served as associate dean for clinical affairs at the University of Missouri School of Medicine and chief medical officer of the University of Missouri Health System in Columbia, Mo. Dr. Hall is a practicing hospitalist and an active member of SHM, and he has continued to care for patients throughout his career as a healthcare leader.

• Liesbet Jansen, MD, was awarded the 2014 Dr. Alexander MacIntyre Award of Excellence by the Alliston (Ontario, Canada) and Area Physician Recruitment Committee for demonstrating excellence in medical practice and commitment to the local community. Dr. Jansen serves as a hospitalist and chief of family medicine at Stevenson Memorial Hospital in Alliston, Ontario, Canada.

Hans Jeppesen, MD, is the new chief of hospital medicine at North Shore Medical Center (NSMC) in Salem, Mass. In addition to overseeing the hospitalist team at NSMC, Dr. Jeppesen will also be responsible for caring for inpatients at NSMC Salem and Union (Lynn, Mass.) Hospitals. Before joining NSMC, Dr. Jeppesen served as chief of hospitalist services at Cambridge Health Alliance in Cambridge, Mass.

Todd Kislak is the new chief development officer for Hospitalists Now, Inc. (HNI), a national physician management company based in Austin, Texas. In his new role, Kislak is responsible for sales and business development as well as marketing for HNI. Kislak formerly served as vice president of marketing and development for IPC The Hospitalist Company, based in North Hollywood, Calif.

Kelly London, PA-C, has been awarded Non-Physician Hospitalist of the Year by the Maryland chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine. London is the first nonphysician provider to receive the award, and was nominated along with other qualified nurse practitioners and physician assistants throughout Maryland. London serves on the hospitalist team at Anne Arundel Medical Center, managed by MDICS (Physicians Inpatient Care Specialists), in Annapolis, Md.

Jennifer Miraglia is the new executive director for the Chicago region of IPC The Hospitalist Company, a national hospital medicine management company based in North Hollywood, Calif. Before coming to IPC, Miraglia worked as regional vice president of operations for RehabCare, a division of Kindred Healthcare based in Louisville, Ky. IPC manages hospitalist services in over 400 hospitals across the United States.

Steven Pantilat, MD, MHM, FAAHPM, recently was awarded the Ritz E. Heerman Memorial Award by the California Hospital Association Board of Trustees for his work on improving the quality of palliative care services in California. Dr. Pantilat is the founding director of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Palliative Care Program, and director of the UCSF Palliative Care Leadership Center. Dr. Pantilat is a past president of SHM and currently works as a professor of clinical medicine at UCSF.

Business Moves

• North Hollywood, Calif.-based IPC The Hospitalist Company has acquired the following practices: Hospital Practice Associates, Inc. (HPA), in Jacksonville, Fla.; John N. Campbell, MD, PC, in Grand Rapids, Mich.; Comprehensive Health Solutions, in Newtown Square, Penn.; Midland Hospitalists PLC in Midland, Mich.; and Clyo Internal Medicine in Dayton, Ohio. IPC is a national hospitalist management company serving over 400 hospitals and 1,200 post-acute care facilities across the country.

• The Greenville, S.C.-based Ob Hospitalist Group (OBHG) recently received the following honors: voted one of the Inc. 5,000 Fastest Growing Private Companies in America for the second year running for a growth rate of 239% since 2011; voted one of the Best Places to Work in South Carolina by the South Carolina Chamber of Commerce and SC Biz News, for the second consecutive year; listed on the Roaring Twenties List from SC Biz News as one of the 40 highest performing companies in South Carolina; and included on South Carolina’s 25 Fastest-Growing Companies list for the third year running. OBHG has been providing OB/GYN hospitalist services across the country since 2006.

• The OSF St. Elizabeth Medical Center in Ottawa, Ill., has just introduced a new hospitalist program at its 99-bed acute care hospital. Robert B. Maguire, MD, a veteran Ottawa doctor, has been chosen to lead the new hospitalist program as medical director. OSF St. Elizabeth will continue to recruit additional hospitalists to the new program with the help of 24ON Physicians/In Compass Health, Inc., a hospitalist staffing firm based in Alpharetta, Ga.

• Penn State Hershey Children’s Hospital is now providing pediatric care at Moses Taylor Hospital in Scranton, Penn. Moses Taylor Hospital is a 217-bed acute care facility operated by Commonwealth Health, the largest healthcare system in northern Pennsylvania, which consists of six hospitals and dozens of post-acute care practices and facilities.

• TeamHealth, a national physician management company based in Knoxville, Tenn., announced its acquisition of Premier Physician Services, Inc., based in Dayton, Ohio. Premier consists of eight hospitalist programs as well as 45 emergency medicine programs, 15 correctional care programs, and 15 occupational medicine programs, which TeamHealth will now oversee. TeamHealth provides physician management and healthcare staffing in 47 states.

This month, The Hospitalist features new appointments, promotions, awards, and achievements of hospital medicine physicians and healthcare industry professionals.

Douglas Carlson, MD, FAAP, SFHM, has been appointed professor and chair of the department of pediatrics at Southern Illinois University in Springfield, Ill. Dr. Carlson is a pediatric hospitalist who served as director of the pediatric hospitalist medicine division at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo. Dr. Carlson currently serves as co-chair of the SHM Pediatric Committee, as well as Workforce Taskforce Leader for the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Leadership Committee and chair of the Pediatric Hospital Medicine National Conference Planning Committee.

Howard Epstein, MD, FHM, has been appointed executive vice president and chief medical officer at PreferredOne, a health services and insurance provider based in Golden Valley, Minn. Dr. Epstein comes to PreferredOne from the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) in Bloomington, where he served as chief health systems officer. An SHM board member, Dr. Epstein previously helped found the hospital medicine and palliative care programs at Regions Hospital and HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

Les Hall, MD, has been appointed executive dean of the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, as well as CEO of Palmetto Health-USC Medical Group in Columbia, S.C. Prior to his role at the University of South Carolina, Dr. Hall served as associate dean for clinical affairs at the University of Missouri School of Medicine and chief medical officer of the University of Missouri Health System in Columbia, Mo. Dr. Hall is a practicing hospitalist and an active member of SHM, and he has continued to care for patients throughout his career as a healthcare leader.

• Liesbet Jansen, MD, was awarded the 2014 Dr. Alexander MacIntyre Award of Excellence by the Alliston (Ontario, Canada) and Area Physician Recruitment Committee for demonstrating excellence in medical practice and commitment to the local community. Dr. Jansen serves as a hospitalist and chief of family medicine at Stevenson Memorial Hospital in Alliston, Ontario, Canada.

Hans Jeppesen, MD, is the new chief of hospital medicine at North Shore Medical Center (NSMC) in Salem, Mass. In addition to overseeing the hospitalist team at NSMC, Dr. Jeppesen will also be responsible for caring for inpatients at NSMC Salem and Union (Lynn, Mass.) Hospitals. Before joining NSMC, Dr. Jeppesen served as chief of hospitalist services at Cambridge Health Alliance in Cambridge, Mass.

Todd Kislak is the new chief development officer for Hospitalists Now, Inc. (HNI), a national physician management company based in Austin, Texas. In his new role, Kislak is responsible for sales and business development as well as marketing for HNI. Kislak formerly served as vice president of marketing and development for IPC The Hospitalist Company, based in North Hollywood, Calif.

Kelly London, PA-C, has been awarded Non-Physician Hospitalist of the Year by the Maryland chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine. London is the first nonphysician provider to receive the award, and was nominated along with other qualified nurse practitioners and physician assistants throughout Maryland. London serves on the hospitalist team at Anne Arundel Medical Center, managed by MDICS (Physicians Inpatient Care Specialists), in Annapolis, Md.

Jennifer Miraglia is the new executive director for the Chicago region of IPC The Hospitalist Company, a national hospital medicine management company based in North Hollywood, Calif. Before coming to IPC, Miraglia worked as regional vice president of operations for RehabCare, a division of Kindred Healthcare based in Louisville, Ky. IPC manages hospitalist services in over 400 hospitals across the United States.

Steven Pantilat, MD, MHM, FAAHPM, recently was awarded the Ritz E. Heerman Memorial Award by the California Hospital Association Board of Trustees for his work on improving the quality of palliative care services in California. Dr. Pantilat is the founding director of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Palliative Care Program, and director of the UCSF Palliative Care Leadership Center. Dr. Pantilat is a past president of SHM and currently works as a professor of clinical medicine at UCSF.

Business Moves

• North Hollywood, Calif.-based IPC The Hospitalist Company has acquired the following practices: Hospital Practice Associates, Inc. (HPA), in Jacksonville, Fla.; John N. Campbell, MD, PC, in Grand Rapids, Mich.; Comprehensive Health Solutions, in Newtown Square, Penn.; Midland Hospitalists PLC in Midland, Mich.; and Clyo Internal Medicine in Dayton, Ohio. IPC is a national hospitalist management company serving over 400 hospitals and 1,200 post-acute care facilities across the country.

• The Greenville, S.C.-based Ob Hospitalist Group (OBHG) recently received the following honors: voted one of the Inc. 5,000 Fastest Growing Private Companies in America for the second year running for a growth rate of 239% since 2011; voted one of the Best Places to Work in South Carolina by the South Carolina Chamber of Commerce and SC Biz News, for the second consecutive year; listed on the Roaring Twenties List from SC Biz News as one of the 40 highest performing companies in South Carolina; and included on South Carolina’s 25 Fastest-Growing Companies list for the third year running. OBHG has been providing OB/GYN hospitalist services across the country since 2006.

• The OSF St. Elizabeth Medical Center in Ottawa, Ill., has just introduced a new hospitalist program at its 99-bed acute care hospital. Robert B. Maguire, MD, a veteran Ottawa doctor, has been chosen to lead the new hospitalist program as medical director. OSF St. Elizabeth will continue to recruit additional hospitalists to the new program with the help of 24ON Physicians/In Compass Health, Inc., a hospitalist staffing firm based in Alpharetta, Ga.

• Penn State Hershey Children’s Hospital is now providing pediatric care at Moses Taylor Hospital in Scranton, Penn. Moses Taylor Hospital is a 217-bed acute care facility operated by Commonwealth Health, the largest healthcare system in northern Pennsylvania, which consists of six hospitals and dozens of post-acute care practices and facilities.

• TeamHealth, a national physician management company based in Knoxville, Tenn., announced its acquisition of Premier Physician Services, Inc., based in Dayton, Ohio. Premier consists of eight hospitalist programs as well as 45 emergency medicine programs, 15 correctional care programs, and 15 occupational medicine programs, which TeamHealth will now oversee. TeamHealth provides physician management and healthcare staffing in 47 states.

LISTEN NOW: Steve Pantilat, MD, SFHM, explains hospitalists' role in palliative care

10 Things Oncologists Think Hospitalists Need to Know

Things you need to know

An occasional series providing specialty-specific advice for hospitalists from experts in the field.

COMING UP: 10 Things Endocrinologists Want HM to Know Archived: @the-hospitalist.org

- 10 Things Infectious Disease

- 12 Things Cardiology

- 12 Things Nephrology

- 12 Things Billing & Coding

Cancer patients can be some of the most complicated and high-stakes patients who come into a hospitalist’s care.

The issues faced by such patients are three-pronged: Besides the effects of the cancer itself, these often elderly patients also grapple with the side effects of treatment and other medical issues.

The Hospitalist sought tips for caring for hospitalized cancer patients from a half-dozen experts in hematology and oncology. Here are the 10 most common pieces of advice they had for hospitalists caring for cancer patients.

1 Know the History

This includes the subtleties of the patient history, which can be quite involved, says Fadlo R. Khuri, MD, FACP, deputy director of the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and chair of hematology and medical oncology at the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

“Part of that history may be obtained from the patient and the patient’s family, but if the treatment has been evolving over time, you need to get in touch with the treating physician or at least have access to the records of the patient’s treatment,” he says. “The arsenal of drugs that we use against cancer has expanded dramatically and in different directions. Now we have tremendous technological innovations with very focused radiation or very refined surgery, and not just novel chemotherapy but also targeted therapies that can target a specific Achilles heel of cancer.”

Basically, it is important for hospitalists to know exactly “what you are dealing with.”

“That’s a lot of information that the hospitalist needs to know. Whom do I contact? Whom do I need to access, not just on the web, but in person, to understand what this patient is going through?” he adds.

With many patients, time is of the essence. This is part of the reason why it’s so important to get a complete history and full picture of a patient’s treatment right away, Dr. Khuri says.

“The patient with cancer often presents in worse shape than patients with other diseases,” he says. “Therefore, with patients with cancer or patients with other really life-threatening illness, you generally have less time to figure out what is going on.”

2 Communication Is Paramount

“The reason that communication is important is to convey the right message to the patient,” says Suresh Ramalingam, MD, professor and director of medical oncology and the lung cancer program at the Emory School of Medicine. “An oncologist who’s been following a patient for a year and a half…I would think has some insight that he or she can provide the hospitalist to manage the acute illness that the patient is admitted with.

“The other thing is many times a patient comes in the hospital and the first question they have is, ‘Does this mean my cancer is getting worse? What is the next option for me? And am I going to die right away?’ And they’re going to ask this question of whomever they see first. Having the oncologist’s thoughts on the patient’s overall status of cancer is important to address such issues.”

Dr. Ramalingam says that a situation that used to occur, but is now less frequent, is frantic calls from a patient in a hospital bed saying, “The hospitalist just walked in, and he said I’m going to die in three weeks. You never told me about that.”

When that happens, “we have to go back and talk to the patient and reassure the patient that that’s not the case,” Dr. Ramalingam says.

3 Treating Cancer Is More Than Treating Cancer

At the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where a pilot hospitalist program that began six years ago has grown into a permanent part of the center, treatment comes from all angles, not just medical, says Josiah Halm, MD, MS, FACP, FHM, CMQ, and Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, assistant professors of general internal medicine at the center.

“I think the biggest thing is to understand that a cancer patient is very complex and there’s much more than the physical component,” says Dr. Gadiraju, one of nine hospitalists at MD Anderson. “There’s an emotional component. There’s a mental component. There’s the family that’s involved.

“One of the biggest things that we do is not just support the patient physically and medically but also emotionally and mentally. And we provide very good family support working as part of an interdisciplinary team.”

4 Know the Baseline

Dr. Khuri says hospitalists should start by seeking answers to some simple questions.

“What kind of situation were they in when they began to deteriorate? Was this patient walking, talking, healthy, eating, working? And is this an acute deterioration, or is this a gradual deterioration?” he says.

The hospitalist caring for a patient with an acute decline might play a major role in the outcome.

“Some of these acute, precipitating events may be treatable, and the hospitalist may be—forgive my language—Johnny-on-the-spot—and may be able to make a major difference in turning that patient around,” he says.

5 Fight for DVT prophylaxis

When patients should be given prophylaxis for DVT, do not be deterred from doing so by the treating oncologist, says Efrén Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine and interim chief of the division of hospital medicine and patient safety officer for the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. For patients undergoing chemotherapy, oncologists might be concerned about the potential for bleeding events, but it’s important to “get with the guidelines,” Dr. Manjarrez says.

“Oftentimes, hospitalists can be undermined by the oncologists that they’re managing their patients with,” he says. “Make sure that you stick to your guns and make sure that you’re strong about giving DVT prophylaxis to these patients, unless they truly meet exclusion criteria for that prophylaxis.

“Sometimes, hematologists or oncologists might actually cancel your order.”

6 ‘More Is Better’ for Genome Analysis

With a fine-needle biopsy, there might not be enough specimen left for molecular analysis, Dr. Ramalingam explains.

“The purpose of the biopsy is no longer just diagnostic; it has significant therapeutic implications. Therefore, getting as much tissue [as possible] during that initial diagnostic biopsy is very helpful, because we conduct detailed molecular studies on these specimens,” he says. “If you don’t get enough specimen in the first biopsy, but you just have enough to make a diagnosis of the type of cancer, then you have to resort to a second biopsy. So, more is better when it comes to tissue.”

7 Consider Pediatric Test Tubes for Pancytopenic Patients

Using smaller test tubes will lower the potential for anemia caused by frequent blood draws, Dr. Manjarrez says. Recent evidence suggests that hospital-acquired anemia prolongs hospital costs, length of stay, and mortality risk—all directly proportional to the level of anemia.1

“We’re causing [patients] to be more anemic with blood draws,” he says. “When you have cancer patients who get chemotherapy, their bone marrow is wiped out by the chemotherapy. So what happens is that you end up in the cycle where you have to keep transfusing these patients. The more blood draws that you get from them, the more we’re exacerbating it.”

8 Respect Your Turf, Their Turf

Dr. Manjarrez says the best way to ensure the hem-onc specialists respect the hospitalist’s turf, and vice versa, is to discuss the treatment parameters ahead of time.

“Try and negotiate comanagement deals with your hematologist-oncologist colleagues before you enter into comanagement relationships with them,” he says.

One particularly sticky situation is when a patient is admitted with the expectation that the hospitalist will be caring for acute issues like infection or cancer-related pain, but then the hospitalization is extended because the oncologist wants to start chemotherapy.

“That can be a problem,” he says. “Agree with your hematology-oncology colleagues what you’re going to do in advance, as much as you can.”

“Oftentimes, hospitalists can be undermined by the oncologists that they’re managing their patients with. Make sure that you stick to your guns and make sure that you’re strong about giving DVT prophylaxis to these patients, unless they truly meet exclusion criteria for that prophylaxis.”

—Efrén Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine, interim chief, division of hospital medicine, patient safety officer, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

9 Be Cautious in Using Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (GCSF)

The medication is used to stimulate the body to produce more white blood cells, which sometimes is needed after chemotherapy. They are good for certain situations but should be handled with care, says Lowell Schnipper, MD, clinical director of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Cancer Center in Boston.

“Because it’s unnecessary and very expensive,” says Dr. Schnipper, who is chair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Value of Care Task Force. “If this is a chemotherapy regimen that has a risk of fever and neutropenia in the context of the chemotherapy, [and] the odds of having that complication are 20% percent or higher with a chemotherapy regimen, we suggest using GCSF.”

If not, then GCSF should be avoided, he says.

Such decisions likely will fall to the treating oncologist, but Dr. Schnipper says it is a topic with which hospitalists should be familiar.

10 Rethink Imaging

“If you get a PET scan in the hospital and a patient is admitted for a different diagnosis, there’s a good likelihood that it’s not going to be reimbursed,” Dr. Ramalingam says.

Plus, he says, a scan done in the hospital could cloud the radiographic findings used to make decisions.

“For instance, for someone with pneumonia, the infiltrate might be difficult to differentiate from cancer,” he says.

Tom Collins is a freelance author in South Florida and longtime contributor to The Hospitalist.

Reference

Things you need to know

An occasional series providing specialty-specific advice for hospitalists from experts in the field.

COMING UP: 10 Things Endocrinologists Want HM to Know Archived: @the-hospitalist.org

- 10 Things Infectious Disease

- 12 Things Cardiology

- 12 Things Nephrology

- 12 Things Billing & Coding

Cancer patients can be some of the most complicated and high-stakes patients who come into a hospitalist’s care.

The issues faced by such patients are three-pronged: Besides the effects of the cancer itself, these often elderly patients also grapple with the side effects of treatment and other medical issues.

The Hospitalist sought tips for caring for hospitalized cancer patients from a half-dozen experts in hematology and oncology. Here are the 10 most common pieces of advice they had for hospitalists caring for cancer patients.

1 Know the History

This includes the subtleties of the patient history, which can be quite involved, says Fadlo R. Khuri, MD, FACP, deputy director of the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and chair of hematology and medical oncology at the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

“Part of that history may be obtained from the patient and the patient’s family, but if the treatment has been evolving over time, you need to get in touch with the treating physician or at least have access to the records of the patient’s treatment,” he says. “The arsenal of drugs that we use against cancer has expanded dramatically and in different directions. Now we have tremendous technological innovations with very focused radiation or very refined surgery, and not just novel chemotherapy but also targeted therapies that can target a specific Achilles heel of cancer.”

Basically, it is important for hospitalists to know exactly “what you are dealing with.”

“That’s a lot of information that the hospitalist needs to know. Whom do I contact? Whom do I need to access, not just on the web, but in person, to understand what this patient is going through?” he adds.

With many patients, time is of the essence. This is part of the reason why it’s so important to get a complete history and full picture of a patient’s treatment right away, Dr. Khuri says.

“The patient with cancer often presents in worse shape than patients with other diseases,” he says. “Therefore, with patients with cancer or patients with other really life-threatening illness, you generally have less time to figure out what is going on.”

2 Communication Is Paramount

“The reason that communication is important is to convey the right message to the patient,” says Suresh Ramalingam, MD, professor and director of medical oncology and the lung cancer program at the Emory School of Medicine. “An oncologist who’s been following a patient for a year and a half…I would think has some insight that he or she can provide the hospitalist to manage the acute illness that the patient is admitted with.

“The other thing is many times a patient comes in the hospital and the first question they have is, ‘Does this mean my cancer is getting worse? What is the next option for me? And am I going to die right away?’ And they’re going to ask this question of whomever they see first. Having the oncologist’s thoughts on the patient’s overall status of cancer is important to address such issues.”

Dr. Ramalingam says that a situation that used to occur, but is now less frequent, is frantic calls from a patient in a hospital bed saying, “The hospitalist just walked in, and he said I’m going to die in three weeks. You never told me about that.”

When that happens, “we have to go back and talk to the patient and reassure the patient that that’s not the case,” Dr. Ramalingam says.

3 Treating Cancer Is More Than Treating Cancer

At the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where a pilot hospitalist program that began six years ago has grown into a permanent part of the center, treatment comes from all angles, not just medical, says Josiah Halm, MD, MS, FACP, FHM, CMQ, and Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, assistant professors of general internal medicine at the center.

“I think the biggest thing is to understand that a cancer patient is very complex and there’s much more than the physical component,” says Dr. Gadiraju, one of nine hospitalists at MD Anderson. “There’s an emotional component. There’s a mental component. There’s the family that’s involved.

“One of the biggest things that we do is not just support the patient physically and medically but also emotionally and mentally. And we provide very good family support working as part of an interdisciplinary team.”

4 Know the Baseline

Dr. Khuri says hospitalists should start by seeking answers to some simple questions.

“What kind of situation were they in when they began to deteriorate? Was this patient walking, talking, healthy, eating, working? And is this an acute deterioration, or is this a gradual deterioration?” he says.

The hospitalist caring for a patient with an acute decline might play a major role in the outcome.

“Some of these acute, precipitating events may be treatable, and the hospitalist may be—forgive my language—Johnny-on-the-spot—and may be able to make a major difference in turning that patient around,” he says.

5 Fight for DVT prophylaxis

When patients should be given prophylaxis for DVT, do not be deterred from doing so by the treating oncologist, says Efrén Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine and interim chief of the division of hospital medicine and patient safety officer for the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. For patients undergoing chemotherapy, oncologists might be concerned about the potential for bleeding events, but it’s important to “get with the guidelines,” Dr. Manjarrez says.

“Oftentimes, hospitalists can be undermined by the oncologists that they’re managing their patients with,” he says. “Make sure that you stick to your guns and make sure that you’re strong about giving DVT prophylaxis to these patients, unless they truly meet exclusion criteria for that prophylaxis.

“Sometimes, hematologists or oncologists might actually cancel your order.”

6 ‘More Is Better’ for Genome Analysis

With a fine-needle biopsy, there might not be enough specimen left for molecular analysis, Dr. Ramalingam explains.

“The purpose of the biopsy is no longer just diagnostic; it has significant therapeutic implications. Therefore, getting as much tissue [as possible] during that initial diagnostic biopsy is very helpful, because we conduct detailed molecular studies on these specimens,” he says. “If you don’t get enough specimen in the first biopsy, but you just have enough to make a diagnosis of the type of cancer, then you have to resort to a second biopsy. So, more is better when it comes to tissue.”

7 Consider Pediatric Test Tubes for Pancytopenic Patients

Using smaller test tubes will lower the potential for anemia caused by frequent blood draws, Dr. Manjarrez says. Recent evidence suggests that hospital-acquired anemia prolongs hospital costs, length of stay, and mortality risk—all directly proportional to the level of anemia.1

“We’re causing [patients] to be more anemic with blood draws,” he says. “When you have cancer patients who get chemotherapy, their bone marrow is wiped out by the chemotherapy. So what happens is that you end up in the cycle where you have to keep transfusing these patients. The more blood draws that you get from them, the more we’re exacerbating it.”

8 Respect Your Turf, Their Turf

Dr. Manjarrez says the best way to ensure the hem-onc specialists respect the hospitalist’s turf, and vice versa, is to discuss the treatment parameters ahead of time.

“Try and negotiate comanagement deals with your hematologist-oncologist colleagues before you enter into comanagement relationships with them,” he says.

One particularly sticky situation is when a patient is admitted with the expectation that the hospitalist will be caring for acute issues like infection or cancer-related pain, but then the hospitalization is extended because the oncologist wants to start chemotherapy.

“That can be a problem,” he says. “Agree with your hematology-oncology colleagues what you’re going to do in advance, as much as you can.”

“Oftentimes, hospitalists can be undermined by the oncologists that they’re managing their patients with. Make sure that you stick to your guns and make sure that you’re strong about giving DVT prophylaxis to these patients, unless they truly meet exclusion criteria for that prophylaxis.”

—Efrén Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine, interim chief, division of hospital medicine, patient safety officer, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

9 Be Cautious in Using Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (GCSF)

The medication is used to stimulate the body to produce more white blood cells, which sometimes is needed after chemotherapy. They are good for certain situations but should be handled with care, says Lowell Schnipper, MD, clinical director of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Cancer Center in Boston.

“Because it’s unnecessary and very expensive,” says Dr. Schnipper, who is chair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Value of Care Task Force. “If this is a chemotherapy regimen that has a risk of fever and neutropenia in the context of the chemotherapy, [and] the odds of having that complication are 20% percent or higher with a chemotherapy regimen, we suggest using GCSF.”

If not, then GCSF should be avoided, he says.

Such decisions likely will fall to the treating oncologist, but Dr. Schnipper says it is a topic with which hospitalists should be familiar.

10 Rethink Imaging

“If you get a PET scan in the hospital and a patient is admitted for a different diagnosis, there’s a good likelihood that it’s not going to be reimbursed,” Dr. Ramalingam says.

Plus, he says, a scan done in the hospital could cloud the radiographic findings used to make decisions.

“For instance, for someone with pneumonia, the infiltrate might be difficult to differentiate from cancer,” he says.

Tom Collins is a freelance author in South Florida and longtime contributor to The Hospitalist.

Reference

Things you need to know

An occasional series providing specialty-specific advice for hospitalists from experts in the field.

COMING UP: 10 Things Endocrinologists Want HM to Know Archived: @the-hospitalist.org

- 10 Things Infectious Disease

- 12 Things Cardiology

- 12 Things Nephrology

- 12 Things Billing & Coding

Cancer patients can be some of the most complicated and high-stakes patients who come into a hospitalist’s care.

The issues faced by such patients are three-pronged: Besides the effects of the cancer itself, these often elderly patients also grapple with the side effects of treatment and other medical issues.

The Hospitalist sought tips for caring for hospitalized cancer patients from a half-dozen experts in hematology and oncology. Here are the 10 most common pieces of advice they had for hospitalists caring for cancer patients.

1 Know the History

This includes the subtleties of the patient history, which can be quite involved, says Fadlo R. Khuri, MD, FACP, deputy director of the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and chair of hematology and medical oncology at the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

“Part of that history may be obtained from the patient and the patient’s family, but if the treatment has been evolving over time, you need to get in touch with the treating physician or at least have access to the records of the patient’s treatment,” he says. “The arsenal of drugs that we use against cancer has expanded dramatically and in different directions. Now we have tremendous technological innovations with very focused radiation or very refined surgery, and not just novel chemotherapy but also targeted therapies that can target a specific Achilles heel of cancer.”

Basically, it is important for hospitalists to know exactly “what you are dealing with.”

“That’s a lot of information that the hospitalist needs to know. Whom do I contact? Whom do I need to access, not just on the web, but in person, to understand what this patient is going through?” he adds.

With many patients, time is of the essence. This is part of the reason why it’s so important to get a complete history and full picture of a patient’s treatment right away, Dr. Khuri says.

“The patient with cancer often presents in worse shape than patients with other diseases,” he says. “Therefore, with patients with cancer or patients with other really life-threatening illness, you generally have less time to figure out what is going on.”

2 Communication Is Paramount

“The reason that communication is important is to convey the right message to the patient,” says Suresh Ramalingam, MD, professor and director of medical oncology and the lung cancer program at the Emory School of Medicine. “An oncologist who’s been following a patient for a year and a half…I would think has some insight that he or she can provide the hospitalist to manage the acute illness that the patient is admitted with.

“The other thing is many times a patient comes in the hospital and the first question they have is, ‘Does this mean my cancer is getting worse? What is the next option for me? And am I going to die right away?’ And they’re going to ask this question of whomever they see first. Having the oncologist’s thoughts on the patient’s overall status of cancer is important to address such issues.”

Dr. Ramalingam says that a situation that used to occur, but is now less frequent, is frantic calls from a patient in a hospital bed saying, “The hospitalist just walked in, and he said I’m going to die in three weeks. You never told me about that.”

When that happens, “we have to go back and talk to the patient and reassure the patient that that’s not the case,” Dr. Ramalingam says.

3 Treating Cancer Is More Than Treating Cancer

At the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where a pilot hospitalist program that began six years ago has grown into a permanent part of the center, treatment comes from all angles, not just medical, says Josiah Halm, MD, MS, FACP, FHM, CMQ, and Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, assistant professors of general internal medicine at the center.

“I think the biggest thing is to understand that a cancer patient is very complex and there’s much more than the physical component,” says Dr. Gadiraju, one of nine hospitalists at MD Anderson. “There’s an emotional component. There’s a mental component. There’s the family that’s involved.

“One of the biggest things that we do is not just support the patient physically and medically but also emotionally and mentally. And we provide very good family support working as part of an interdisciplinary team.”

4 Know the Baseline

Dr. Khuri says hospitalists should start by seeking answers to some simple questions.

“What kind of situation were they in when they began to deteriorate? Was this patient walking, talking, healthy, eating, working? And is this an acute deterioration, or is this a gradual deterioration?” he says.

The hospitalist caring for a patient with an acute decline might play a major role in the outcome.

“Some of these acute, precipitating events may be treatable, and the hospitalist may be—forgive my language—Johnny-on-the-spot—and may be able to make a major difference in turning that patient around,” he says.

5 Fight for DVT prophylaxis

When patients should be given prophylaxis for DVT, do not be deterred from doing so by the treating oncologist, says Efrén Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine and interim chief of the division of hospital medicine and patient safety officer for the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. For patients undergoing chemotherapy, oncologists might be concerned about the potential for bleeding events, but it’s important to “get with the guidelines,” Dr. Manjarrez says.

“Oftentimes, hospitalists can be undermined by the oncologists that they’re managing their patients with,” he says. “Make sure that you stick to your guns and make sure that you’re strong about giving DVT prophylaxis to these patients, unless they truly meet exclusion criteria for that prophylaxis.

“Sometimes, hematologists or oncologists might actually cancel your order.”

6 ‘More Is Better’ for Genome Analysis

With a fine-needle biopsy, there might not be enough specimen left for molecular analysis, Dr. Ramalingam explains.

“The purpose of the biopsy is no longer just diagnostic; it has significant therapeutic implications. Therefore, getting as much tissue [as possible] during that initial diagnostic biopsy is very helpful, because we conduct detailed molecular studies on these specimens,” he says. “If you don’t get enough specimen in the first biopsy, but you just have enough to make a diagnosis of the type of cancer, then you have to resort to a second biopsy. So, more is better when it comes to tissue.”

7 Consider Pediatric Test Tubes for Pancytopenic Patients

Using smaller test tubes will lower the potential for anemia caused by frequent blood draws, Dr. Manjarrez says. Recent evidence suggests that hospital-acquired anemia prolongs hospital costs, length of stay, and mortality risk—all directly proportional to the level of anemia.1

“We’re causing [patients] to be more anemic with blood draws,” he says. “When you have cancer patients who get chemotherapy, their bone marrow is wiped out by the chemotherapy. So what happens is that you end up in the cycle where you have to keep transfusing these patients. The more blood draws that you get from them, the more we’re exacerbating it.”

8 Respect Your Turf, Their Turf

Dr. Manjarrez says the best way to ensure the hem-onc specialists respect the hospitalist’s turf, and vice versa, is to discuss the treatment parameters ahead of time.

“Try and negotiate comanagement deals with your hematologist-oncologist colleagues before you enter into comanagement relationships with them,” he says.

One particularly sticky situation is when a patient is admitted with the expectation that the hospitalist will be caring for acute issues like infection or cancer-related pain, but then the hospitalization is extended because the oncologist wants to start chemotherapy.

“That can be a problem,” he says. “Agree with your hematology-oncology colleagues what you’re going to do in advance, as much as you can.”

“Oftentimes, hospitalists can be undermined by the oncologists that they’re managing their patients with. Make sure that you stick to your guns and make sure that you’re strong about giving DVT prophylaxis to these patients, unless they truly meet exclusion criteria for that prophylaxis.”

—Efrén Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine, interim chief, division of hospital medicine, patient safety officer, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

9 Be Cautious in Using Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (GCSF)

The medication is used to stimulate the body to produce more white blood cells, which sometimes is needed after chemotherapy. They are good for certain situations but should be handled with care, says Lowell Schnipper, MD, clinical director of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Cancer Center in Boston.

“Because it’s unnecessary and very expensive,” says Dr. Schnipper, who is chair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Value of Care Task Force. “If this is a chemotherapy regimen that has a risk of fever and neutropenia in the context of the chemotherapy, [and] the odds of having that complication are 20% percent or higher with a chemotherapy regimen, we suggest using GCSF.”

If not, then GCSF should be avoided, he says.

Such decisions likely will fall to the treating oncologist, but Dr. Schnipper says it is a topic with which hospitalists should be familiar.

10 Rethink Imaging

“If you get a PET scan in the hospital and a patient is admitted for a different diagnosis, there’s a good likelihood that it’s not going to be reimbursed,” Dr. Ramalingam says.

Plus, he says, a scan done in the hospital could cloud the radiographic findings used to make decisions.

“For instance, for someone with pneumonia, the infiltrate might be difficult to differentiate from cancer,” he says.

Tom Collins is a freelance author in South Florida and longtime contributor to The Hospitalist.

Reference

Should Patients with an Unprovoked VTE Be Screened for Malignancy or a Hypercoagulable State?

Case

A 56-year-old woman with hypertension and diabetes presents to the hospital with acute onset of painful swelling in her right calf. She has had no recent surgeries, trauma, or travel, and takes lisinopril and metformin. An ultrasound of her right lower extremity demonstrates a venous thromboembolism (VTE). The patient’s last mammogram was three years ago, and she’s never undergone a screening colonoscopy. On lab workup, she is noted to have a microcytic anemia.

Should this patient be screened for an underlying hypercoagulable state or malignancy?

Background

An estimated 550,000 hospitalized adults are diagnosed with VTE each year.1 VTE can occur in the absence of known precipitants (unprovoked) or can be temporally associated with a known major risk factor (provoked). This practical division has implications for both treatment duration and risk of recurrence. A VTE is considered provoked if it occurs in the setting of surgery, leg trauma, fracture, pregnancy within the previous three months, estrogen therapy, immobility from an acute illness for more than one week, travel lasting more than six hours, or active malignancy.2 If none of these provoking factors is present, the VTE is considered unprovoked.2

Nearly 20% of first-time VTE events can be attributed to malignancy.3 Additionally, patients presenting with an unprovoked VTE possess a higher risk of being diagnosed with a cancer, raising the question of whether unprovoked VTEs should compel aggressive malignancy screening.4

Before the discovery of antithrombin deficiency in 1965, most unprovoked VTE events remained unexplained. Since then, numerous inherited coagulation abnormalities have been identified. It is now estimated that coagulation abnormalities can be found in up to half of patients with unprovoked thrombi.5

The increase in availability of molecular and genetic assays for hypercoagulability has been accompanied by a dramatic rise in the rate of testing for these disorders.6 Despite increased testing available for inherited thrombophilias, disagreement exists over the utility of this workup.6

Review of the Data

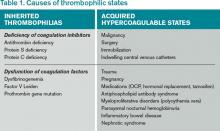

Hypercoagulability leading to venous thrombosis can be broadly divided into two groups: acquired and hereditary (see Table 1). First, let’s examine acquired hypercoagulable states.

Malignancy: Armand Trousseau first suggested an association between thrombotic events and malignancy in 1865. Malignancy causes a hypercoagulable state; additionally, tumors can cause thromboemboli by other mechanisms, such as vascular invasion or external compression of vasculature.7

Multiple studies demonstrate that malignancy increases the chance of developing a VTE. A Danish cohort study of nearly 60,000 cancer patients compared with over 280,000 controls over nine years offered twice the incidence of VTE in patients with cancer.8 Other studies reveal that VTE rates peak in the first year after a cancer diagnosis; moreover, VTE events are associated with more advanced disease and worse prognosis.9 Approximately 11% of cancer patients will develop a clinically evident VTE during the course of their disease.10,11

The majority of cancers associated with VTE events are clinically evident; however, some patients with thrombi have an occult malignancy. During the two years following an unprovoked VTE, the rate of discovering a previously undiagnosed malignancy was three times higher when compared with provoked VTE.6

This potential to diagnose occult malignancy in patients with idiopathic thromboembolic events stimulates debate around the usefulness of extensive cancer screening for these patients. One large systematic review compared routine and extensive cancer screening strategies following an unprovoked VTE. An extensive screening strategy consisting of CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis significantly increased the proportion of previously undiagnosed cancers; however, the authors did not determine complication rates, cost effectiveness, or difference in morbidity and mortality associated with extensive screening strategies.7

Other studies have demonstrated that extensive screening with CT, endoscopy, and tumor markers finds more previously undetected cancers; however, up to half of these malignancies could have been identified without resorting to such expensive and invasive workups.12 Additionally, no prospective data demonstrate improved outcomes or increased survival from these diagnoses. Likewise, no cost-effectiveness data exist to support this expensive and aggressive screening approach.7

All patients with an idiopathic VTE should undergo a complete history and physical examination with attention to common areas of malignancy. Patients should have basic lab work and be recommended for age-appropriate cancer screening (see Table 2). Any abnormalities uncovered on this initial workup should be aggressively investigated.13 If overt cancer is detected, then low molecular weight heparin would be preferred over oral anticoagulation as treatment for the VTE.14 Extensive malignancy evaluation in all patients with unprovoked VTE is not warranted, however, given the lack of data regarding efficacy of extensive screening, the potential for increased harms, and the costs associated with this approach.

Antiphospholipid syndrome: Antiphospholipid syndrome is the most common acquired cause of thrombophilia.15 Characterized by the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (e.g. lupus anticoagulant antibodies or anticardiolipin antibodies), this syndrome is usually secondary to cancer or an autoimmune disease.

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome is a thrombophilic disorder in which both venous and arterial thrombosis may occur. Patients with this disorder are considered at high risk for thrombotic events. Data suggest that antiphospholipid antibody syndrome also increases the risk of VTE recurrence. In one retrospective study, cessation of warfarin therapy in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies after a VTE resulted in 69% of patients having recurrent thrombosis in the first year.16 Given this substantial risk, antiphospholipid antibody testing is recommended in those with a suggestive history, including patients with 1) recurrent fetal loss, 2) fetal loss after 10 weeks, or 3) known collagen vascular disease.16 Lifelong anticoagulation is recommended for these patients.

Inherited hypercoagulable states: The most frequent causes of an inherited hypercoagulable state are the factor V Leiden mutation and the prothrombin gene mutation, accounting for 50% to 60% of hereditary thrombophilias. Protein S, protein C, and antithrombin defects account for most of the remaining cases of inherited thrombophilias.15

Currently, there is no consensus regarding who should be tested for inherited thrombophilia. Testing for an inherited thrombophilia would be indicated if the results added prognostic information or changed management. Arguments against testing hinge on the fact that neither prognosis nor management is affected by the presence of an inherited thrombophilia.

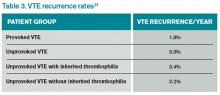

The presence of a thrombophilia also does not change the method or intensity of anticoagulation.17 The risk of recurrence after discontinuing anticoagulation therapy is not affected.17,18 The strongest predictor of VTE recurrence is the unprovoked VTE itself, regardless of an underlying thrombophilia.15 Recurrent VTE is nearly twice as frequent in patients with idiopathic VTE compared to those with provoked VTE.15

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends treating a provoked VTE for three months.19 According to the same guidelines, an unprovoked VTE should be treated for a minimum of three months, and lifelong anticoagulation should be considered.19

Overall, the rate of recurrence after a first VTE is considerable after completion of anticoagulation, especially for an unprovoked thrombotic event. Studies show a 7%-15% recurrence rate during the two years following the index VTE (see Table 3).17,20,21 Currently, no data suggest that a hereditary thrombophilia substantially changes this baseline high recurrent risk. ACCP recommendations state that the presence of hereditary thrombophilia should not be used as a major factor to guide duration of anticoagulation.19

Back to the Case

Our patient presented with an unprovoked VTE. She should be started on anticoagulation therapy with low molecular weight heparin and transitioned to oral anticoagulation.

Her highest risk for VTE recurrence is the unprovoked VTE itself, regardless of an underlying thrombophilia. Since the presence of an inherited thrombophilia will not change duration or intensity of management, our patient should not be tested.

There are no prospective trials showing improved outcomes from aggressive workup for occult malignancy. Given this information, an extensive workup for occult malignancy should not be undertaken; however, this patient has an idiopathic VTE and should undergo a complete history, physical examination, and basic lab work, with attention to common areas of malignancy. Any abnormalities uncovered on this initial workup should be investigated more aggressively. Screening with mammography and Pap smear should be arranged in outpatient follow-up and communicated to the primary care physician, because she is not up to date with these age-appropriate screening tests.

Based on new evidence, a low-dose chest CT would be a consideration if she had a smoking history of at least 30 pack-years.22 Her microcytic anemia uncovered on routine lab work should be investigated further for a possible underlying gastrointestinal malignancy.

Bottom Line

An initial diagnosis of unprovoked VTE remains the strongest risk factor for recurrent thromboembolic events. The presence of an inherited thrombophilia does not significantly alter management. Aggressive workup for occult malignancy has not prospectively improved outcomes, but age-appropriate malignancy screening should be recommended.

Drs. Czernik and Anderson are hospitalists and instructors of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver (UCD). Dr. Wolfe is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UCD. Dr. Cumbler is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at UCD.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous thromboembolism in adult hospitalizations—United States, 2007–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(22);401-404.

- Baglin T, Gray E, Greaves M, et al. Clinical guidelines for testing for heritable thrombophilia. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(2):209-220.

- Heit, JA, O’Fallon WM, Petterson TM, et al. Relative impact of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(11):1245-1248.

- Iodice S, Gandini S, Löhr M, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Venous thromboembolic events and organ-specific occult cancers: a review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(5):781-788.

- Coppens M, Reijnders JH, Middeldorp S, Doggen CJ, Rosendaal FR. Testing for inherited thrombophilia does not reduce the recurrence of venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(9):1474-1477.

- Coppens M, van Mourik JA, Eckmann CM, Büller HR, Middeldorp S. Current practise of testing for inherited thrombophilia. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(9):1979-1981.

- Carrier M, Le Gal G, Wells PS, Fergusson D, Ramsay T, Rodger MA. Systematic review: the Trousseau syndrome revisited: should we screen extensively for cancer in patients with venous thromboembolism? Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):323-333.

- Cronin-Fenton DP, Søndergaard F, Pedersen LA, et al. Hospitalisation for venous thromboembolism in cancer patients and the general population: a population-based cohort study in Denmark, 1997-2006. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(7):947-953.

- Chew HK, Wun T, Harvey D, Zhou H, White RH. Incidence of venous thromboembolism and its effect on survival among patients with common cancers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(4):458-464.

- Lee JL, Lee JH, Kim MK, et al. A case of bone marrow necrosis with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura as a manifestation of occult colon cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34(8):476-480.

- Sack GH Jr, Levin J, Bell WR. Trousseau’s syndrome and other manifestations of chronic disseminated coagulopathy in patients with neoplasms: clinical, pathophysiologic, and therapeutic features. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56(1):1-37.

- Prins MH, Hettiarachchi RJ, Lensing AW, Hirsh J. Newly diagnosed malignancy in patients with venous thromboembolism. Search or wait and see? Thromb Haemost. 1997;78(1):121-125.

- Cornuz J, Pearson SD, Creager MA, Cook EF, Goldman L. Importance of findings on the initial evaluation for cancer in patients with symptomatic idiopathic deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(10):785-793.