User login

Hospitalist Compensation Models Evolve Toward Production, Performance-Based Variables

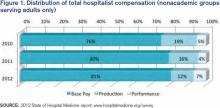

Hospitalists have long recognized that compensation varies significantly by geographic location and by the type of hospitalist medicine group (HMG) you work in: private vs. hospital-owned vs. national-management-owned. A review of SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report suggests that hospitalist compensation is also evolving toward a model that more routinely includes both some production variable and performance-based pay (see Figure 1). Although the proportion of compensation paid as a base salary has been trending up over the last few years, so has the proportion paid as a performance incentive.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report; www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey

The pay distribution of adult-medicine hospitalists employed by management companies is composed of a high base percentage (mean 88.3% by survey data) and relatively low production and performance variables (mean 6.8% and 4.9%, respectively) compared with other employment models. Contrast that with private hospitalist-only groups, where the mean base is 76.3% with an emphasis on a production component (19.4%) and slightly less on performance pay at 4.2%.

Of the three employment models, however, hospital-/health-system-employed groups have the highest proportion of compensation based on performance metrics with a mean of 7.8%. This makes sense given the financial penalties hospitals and health systems are facing from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) around pay-for-performance measures. Hospitals are looking for help from hospitalists in improving quality of care and patient satisfaction and avoiding incurring future penalties. Compensation models in these groups reflect the goals of aligning performance on these measures with financial incentives/risk for hospitalists working in these environments.

What are the top performance metrics hospitalists are being compensated for? CMS’ hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) core measures and patient satisfaction scores are at the top of the list. More than 70% of all HMGs identify these two measures as part of their performance pay incentive, which is seen consistently by geographic location and by type of hospitalist group.

Beyond these top two metrics, management-company-employed groups also focus on ED throughput measures and early morning discharge times, with more than 70% of these groups having pay incentives aligned with these goals. They also have a higher proportion of their groups participating in several other measures, such as clinical protocols, medication reconciliation, EHR utilization, transitions of care, and readmission rates. In comparison, both hospital-employed and private groups have a wider variety of performance measures in which they participate. Differences are seen geographically, too, with hospitalists located in the Western region having a wider variety of performance measures than other regions.

How hospitalists are compensated for their work will likely continue to evolve. Overall, for nonacademic HMGs serving adults only, we are seeing an upward trend in percentage paid as base pay (from 76% in 2010 to 81% in 2012) and in performance (from 5% in 2010 to 7% in 2012). Hospitalists should anticipate that performance-based pay will continue to account for an increasingly larger percentage of their overall compensation, especially as CMS’ pay-for-performance measures for hospital systems really start to take effect.

Hospital CEOs and CFOs are looking to hospitalists to help deliver on quality, satisfaction, and other performance measures. Incentives will be put in place to reward those groups who do it well.

Dr. Sites is senior medical director of hospitalist programs at Providence Health and Services in Oregon. She is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Hospitalists have long recognized that compensation varies significantly by geographic location and by the type of hospitalist medicine group (HMG) you work in: private vs. hospital-owned vs. national-management-owned. A review of SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report suggests that hospitalist compensation is also evolving toward a model that more routinely includes both some production variable and performance-based pay (see Figure 1). Although the proportion of compensation paid as a base salary has been trending up over the last few years, so has the proportion paid as a performance incentive.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report; www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey

The pay distribution of adult-medicine hospitalists employed by management companies is composed of a high base percentage (mean 88.3% by survey data) and relatively low production and performance variables (mean 6.8% and 4.9%, respectively) compared with other employment models. Contrast that with private hospitalist-only groups, where the mean base is 76.3% with an emphasis on a production component (19.4%) and slightly less on performance pay at 4.2%.

Of the three employment models, however, hospital-/health-system-employed groups have the highest proportion of compensation based on performance metrics with a mean of 7.8%. This makes sense given the financial penalties hospitals and health systems are facing from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) around pay-for-performance measures. Hospitals are looking for help from hospitalists in improving quality of care and patient satisfaction and avoiding incurring future penalties. Compensation models in these groups reflect the goals of aligning performance on these measures with financial incentives/risk for hospitalists working in these environments.

What are the top performance metrics hospitalists are being compensated for? CMS’ hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) core measures and patient satisfaction scores are at the top of the list. More than 70% of all HMGs identify these two measures as part of their performance pay incentive, which is seen consistently by geographic location and by type of hospitalist group.

Beyond these top two metrics, management-company-employed groups also focus on ED throughput measures and early morning discharge times, with more than 70% of these groups having pay incentives aligned with these goals. They also have a higher proportion of their groups participating in several other measures, such as clinical protocols, medication reconciliation, EHR utilization, transitions of care, and readmission rates. In comparison, both hospital-employed and private groups have a wider variety of performance measures in which they participate. Differences are seen geographically, too, with hospitalists located in the Western region having a wider variety of performance measures than other regions.

How hospitalists are compensated for their work will likely continue to evolve. Overall, for nonacademic HMGs serving adults only, we are seeing an upward trend in percentage paid as base pay (from 76% in 2010 to 81% in 2012) and in performance (from 5% in 2010 to 7% in 2012). Hospitalists should anticipate that performance-based pay will continue to account for an increasingly larger percentage of their overall compensation, especially as CMS’ pay-for-performance measures for hospital systems really start to take effect.

Hospital CEOs and CFOs are looking to hospitalists to help deliver on quality, satisfaction, and other performance measures. Incentives will be put in place to reward those groups who do it well.

Dr. Sites is senior medical director of hospitalist programs at Providence Health and Services in Oregon. She is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Hospitalists have long recognized that compensation varies significantly by geographic location and by the type of hospitalist medicine group (HMG) you work in: private vs. hospital-owned vs. national-management-owned. A review of SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report suggests that hospitalist compensation is also evolving toward a model that more routinely includes both some production variable and performance-based pay (see Figure 1). Although the proportion of compensation paid as a base salary has been trending up over the last few years, so has the proportion paid as a performance incentive.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report; www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey

The pay distribution of adult-medicine hospitalists employed by management companies is composed of a high base percentage (mean 88.3% by survey data) and relatively low production and performance variables (mean 6.8% and 4.9%, respectively) compared with other employment models. Contrast that with private hospitalist-only groups, where the mean base is 76.3% with an emphasis on a production component (19.4%) and slightly less on performance pay at 4.2%.

Of the three employment models, however, hospital-/health-system-employed groups have the highest proportion of compensation based on performance metrics with a mean of 7.8%. This makes sense given the financial penalties hospitals and health systems are facing from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) around pay-for-performance measures. Hospitals are looking for help from hospitalists in improving quality of care and patient satisfaction and avoiding incurring future penalties. Compensation models in these groups reflect the goals of aligning performance on these measures with financial incentives/risk for hospitalists working in these environments.

What are the top performance metrics hospitalists are being compensated for? CMS’ hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) core measures and patient satisfaction scores are at the top of the list. More than 70% of all HMGs identify these two measures as part of their performance pay incentive, which is seen consistently by geographic location and by type of hospitalist group.

Beyond these top two metrics, management-company-employed groups also focus on ED throughput measures and early morning discharge times, with more than 70% of these groups having pay incentives aligned with these goals. They also have a higher proportion of their groups participating in several other measures, such as clinical protocols, medication reconciliation, EHR utilization, transitions of care, and readmission rates. In comparison, both hospital-employed and private groups have a wider variety of performance measures in which they participate. Differences are seen geographically, too, with hospitalists located in the Western region having a wider variety of performance measures than other regions.

How hospitalists are compensated for their work will likely continue to evolve. Overall, for nonacademic HMGs serving adults only, we are seeing an upward trend in percentage paid as base pay (from 76% in 2010 to 81% in 2012) and in performance (from 5% in 2010 to 7% in 2012). Hospitalists should anticipate that performance-based pay will continue to account for an increasingly larger percentage of their overall compensation, especially as CMS’ pay-for-performance measures for hospital systems really start to take effect.

Hospital CEOs and CFOs are looking to hospitalists to help deliver on quality, satisfaction, and other performance measures. Incentives will be put in place to reward those groups who do it well.

Dr. Sites is senior medical director of hospitalist programs at Providence Health and Services in Oregon. She is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

SHM Advocates for Medicare to Cover Skilled-Nursing Facilities

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently issued a Final Rule for the Inpatient Prospective Payment System, which guides payment and programs associated with inpatient hospitalizations. In this year’s rule, CMS adjusted the criteria for inpatient admissions in an attempt to simplify and clarify the decision-making process.

The policy would allow physicians to admit a patient if they reasonably expect and document in the medical record that a beneficiary will need to stay in the hospital for more than two midnights. Admissions based on this time-limited expectation will be presumed to be appropriate for Medicare Part A payment. CMS cited concerns about the growing trend of longer observation stays to support this change.

With observation stays, there are two major financial concerns for patients: whether the hospital stay is paid under Medicare Part A or Part B, and whether Medicare will pay for post-acute care in a skilled-nursing facility (SNF). Medicare Part A reimburses for inpatient admissions, with a one-time deductible for the benefit period. Outpatient services, such as observation care and physician services, are covered under Medicare Part B, which has copays and co-insurance that greatly increase the costs for beneficiaries. In addition, SNF coverage through Medicare Part A is determined by the three-day rule; a patient must be an inpatient for three days to qualify for coverage.

While the long-term impacts of this regulatory change to the admission criteria remain to be seen, SHM is concerned that the rule does not adequately address the broader problems associated with inpatient and observation status. As we note in our comments to CMS on the new rule:1

Even with these changes, the central tension created by the bifurcation in admission status still remains.…Other policies and programs, such as the attempts to reduce admissions, may inadvertently add pressure to the admission decision.

Indeed, for beneficiaries, the barrier to SNF coverage remains. CMS takes care to note that, while time under emergency care and observation care count toward the two-midnight presumption for inpatient admission, it does not count toward the three-day rule for SNF coverage. This is particularly problematic; as advances in medicine allow for the treatment of higher-acuity and -severity conditions with observation stays or shorter inpatient stays, patients might not be getting the follow-up care they need. This puts them at risk for additional complications and, ultimately, readmissions to the hospital.

In an era of seeking value in the healthcare system, it seems like an opportunity lost to streamline and coordinate care across settings and to ensure that patients are getting the follow-up care they require. It is for this reason that hospitalists continue to push for passage of the Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act, a bill sponsored by Rep. Joe Courtney (D-Conn.), Rep. Tom Latham (R-Iowa), and Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) that would count observation status as time toward the three-day requirement for SNF coverage.

A recent Office of Inspector General (OIG) report for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on observation status sums up the problem succinctly.2 The OIG states that “CMS should consider how to ensure that beneficiaries with similar post-hospital care needs have the same access and cost-sharing for SNF services.”2

SHM concurs.

Joshua Lapps is SHM’s government relations specialist.

References

- Society of Hospital Medicine. SHM submits comments in response to FY2014 inpatient prospective payment system proposed rule. Society of Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Letters_to_Congress_and_Regulatory_Agencies&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=34044. Accessed Sept. 9, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Memorandum report: Hospitals’ use of observations stays and short inpatient stays for Medicare beneficiaries, OEI-02-12-00040. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. Available at: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.pdf. Accessed Sept. 9, 2013.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently issued a Final Rule for the Inpatient Prospective Payment System, which guides payment and programs associated with inpatient hospitalizations. In this year’s rule, CMS adjusted the criteria for inpatient admissions in an attempt to simplify and clarify the decision-making process.

The policy would allow physicians to admit a patient if they reasonably expect and document in the medical record that a beneficiary will need to stay in the hospital for more than two midnights. Admissions based on this time-limited expectation will be presumed to be appropriate for Medicare Part A payment. CMS cited concerns about the growing trend of longer observation stays to support this change.

With observation stays, there are two major financial concerns for patients: whether the hospital stay is paid under Medicare Part A or Part B, and whether Medicare will pay for post-acute care in a skilled-nursing facility (SNF). Medicare Part A reimburses for inpatient admissions, with a one-time deductible for the benefit period. Outpatient services, such as observation care and physician services, are covered under Medicare Part B, which has copays and co-insurance that greatly increase the costs for beneficiaries. In addition, SNF coverage through Medicare Part A is determined by the three-day rule; a patient must be an inpatient for three days to qualify for coverage.

While the long-term impacts of this regulatory change to the admission criteria remain to be seen, SHM is concerned that the rule does not adequately address the broader problems associated with inpatient and observation status. As we note in our comments to CMS on the new rule:1

Even with these changes, the central tension created by the bifurcation in admission status still remains.…Other policies and programs, such as the attempts to reduce admissions, may inadvertently add pressure to the admission decision.

Indeed, for beneficiaries, the barrier to SNF coverage remains. CMS takes care to note that, while time under emergency care and observation care count toward the two-midnight presumption for inpatient admission, it does not count toward the three-day rule for SNF coverage. This is particularly problematic; as advances in medicine allow for the treatment of higher-acuity and -severity conditions with observation stays or shorter inpatient stays, patients might not be getting the follow-up care they need. This puts them at risk for additional complications and, ultimately, readmissions to the hospital.

In an era of seeking value in the healthcare system, it seems like an opportunity lost to streamline and coordinate care across settings and to ensure that patients are getting the follow-up care they require. It is for this reason that hospitalists continue to push for passage of the Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act, a bill sponsored by Rep. Joe Courtney (D-Conn.), Rep. Tom Latham (R-Iowa), and Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) that would count observation status as time toward the three-day requirement for SNF coverage.

A recent Office of Inspector General (OIG) report for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on observation status sums up the problem succinctly.2 The OIG states that “CMS should consider how to ensure that beneficiaries with similar post-hospital care needs have the same access and cost-sharing for SNF services.”2

SHM concurs.

Joshua Lapps is SHM’s government relations specialist.

References

- Society of Hospital Medicine. SHM submits comments in response to FY2014 inpatient prospective payment system proposed rule. Society of Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Letters_to_Congress_and_Regulatory_Agencies&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=34044. Accessed Sept. 9, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Memorandum report: Hospitals’ use of observations stays and short inpatient stays for Medicare beneficiaries, OEI-02-12-00040. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. Available at: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.pdf. Accessed Sept. 9, 2013.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently issued a Final Rule for the Inpatient Prospective Payment System, which guides payment and programs associated with inpatient hospitalizations. In this year’s rule, CMS adjusted the criteria for inpatient admissions in an attempt to simplify and clarify the decision-making process.

The policy would allow physicians to admit a patient if they reasonably expect and document in the medical record that a beneficiary will need to stay in the hospital for more than two midnights. Admissions based on this time-limited expectation will be presumed to be appropriate for Medicare Part A payment. CMS cited concerns about the growing trend of longer observation stays to support this change.

With observation stays, there are two major financial concerns for patients: whether the hospital stay is paid under Medicare Part A or Part B, and whether Medicare will pay for post-acute care in a skilled-nursing facility (SNF). Medicare Part A reimburses for inpatient admissions, with a one-time deductible for the benefit period. Outpatient services, such as observation care and physician services, are covered under Medicare Part B, which has copays and co-insurance that greatly increase the costs for beneficiaries. In addition, SNF coverage through Medicare Part A is determined by the three-day rule; a patient must be an inpatient for three days to qualify for coverage.

While the long-term impacts of this regulatory change to the admission criteria remain to be seen, SHM is concerned that the rule does not adequately address the broader problems associated with inpatient and observation status. As we note in our comments to CMS on the new rule:1

Even with these changes, the central tension created by the bifurcation in admission status still remains.…Other policies and programs, such as the attempts to reduce admissions, may inadvertently add pressure to the admission decision.

Indeed, for beneficiaries, the barrier to SNF coverage remains. CMS takes care to note that, while time under emergency care and observation care count toward the two-midnight presumption for inpatient admission, it does not count toward the three-day rule for SNF coverage. This is particularly problematic; as advances in medicine allow for the treatment of higher-acuity and -severity conditions with observation stays or shorter inpatient stays, patients might not be getting the follow-up care they need. This puts them at risk for additional complications and, ultimately, readmissions to the hospital.

In an era of seeking value in the healthcare system, it seems like an opportunity lost to streamline and coordinate care across settings and to ensure that patients are getting the follow-up care they require. It is for this reason that hospitalists continue to push for passage of the Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act, a bill sponsored by Rep. Joe Courtney (D-Conn.), Rep. Tom Latham (R-Iowa), and Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) that would count observation status as time toward the three-day requirement for SNF coverage.

A recent Office of Inspector General (OIG) report for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on observation status sums up the problem succinctly.2 The OIG states that “CMS should consider how to ensure that beneficiaries with similar post-hospital care needs have the same access and cost-sharing for SNF services.”2

SHM concurs.

Joshua Lapps is SHM’s government relations specialist.

References

- Society of Hospital Medicine. SHM submits comments in response to FY2014 inpatient prospective payment system proposed rule. Society of Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Letters_to_Congress_and_Regulatory_Agencies&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=34044. Accessed Sept. 9, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Memorandum report: Hospitals’ use of observations stays and short inpatient stays for Medicare beneficiaries, OEI-02-12-00040. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. Available at: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.pdf. Accessed Sept. 9, 2013.

Bleeding Risks, Anticoagulants, Hospital-Acquired Infections Among Can't Miss Topics at HM14

What breakout-session and pre-course topics are HM14 course director Daniel Brotman, MD, SFHM, and assistant course director Efren Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, looking forward to showcasing? Here is a sampling:

- Bleeding risks: a crucial yet misunderstood area.

- New anticoagulants: a quickly evolving area that will affect lots of hospitalists and patients.

- What keeps your CFO up at night: a financial perspective from a hospital president and hospitalist.

- Choosing Wisely: Learn how SHM turned the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely initiative into practical recommendations for hospitalists.

- Pediatric clinical conundrums.

- Updates in key specialty and content areas.

- Hospital-acquired infection control by Sanjay Saint.

- CMS’ meaningful use.

What breakout-session and pre-course topics are HM14 course director Daniel Brotman, MD, SFHM, and assistant course director Efren Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, looking forward to showcasing? Here is a sampling:

- Bleeding risks: a crucial yet misunderstood area.

- New anticoagulants: a quickly evolving area that will affect lots of hospitalists and patients.

- What keeps your CFO up at night: a financial perspective from a hospital president and hospitalist.

- Choosing Wisely: Learn how SHM turned the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely initiative into practical recommendations for hospitalists.

- Pediatric clinical conundrums.

- Updates in key specialty and content areas.

- Hospital-acquired infection control by Sanjay Saint.

- CMS’ meaningful use.

What breakout-session and pre-course topics are HM14 course director Daniel Brotman, MD, SFHM, and assistant course director Efren Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, looking forward to showcasing? Here is a sampling:

- Bleeding risks: a crucial yet misunderstood area.

- New anticoagulants: a quickly evolving area that will affect lots of hospitalists and patients.

- What keeps your CFO up at night: a financial perspective from a hospital president and hospitalist.

- Choosing Wisely: Learn how SHM turned the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely initiative into practical recommendations for hospitalists.

- Pediatric clinical conundrums.

- Updates in key specialty and content areas.

- Hospital-acquired infection control by Sanjay Saint.

- CMS’ meaningful use.

Make Plans Now for HM14

SHM’s next annual meeting, HM14, is only six months away. So today is the day to make scheduling requests and book a room. And, for the first time, the biggest annual event in hospital medicine will be in Las Vegas.

HM14 will be held March 24-27 at Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas. Meeting registration is now open at www.hospitalmedicine2014.org. The early registration discount ends Jan. 26.

Who should attend HM14? Bring the whole team: hospitalists, pediatricians, academic hospitalists, general internists, family physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, administrators, and providers practicing in acute-care settings.

SHM’s next annual meeting, HM14, is only six months away. So today is the day to make scheduling requests and book a room. And, for the first time, the biggest annual event in hospital medicine will be in Las Vegas.

HM14 will be held March 24-27 at Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas. Meeting registration is now open at www.hospitalmedicine2014.org. The early registration discount ends Jan. 26.

Who should attend HM14? Bring the whole team: hospitalists, pediatricians, academic hospitalists, general internists, family physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, administrators, and providers practicing in acute-care settings.

SHM’s next annual meeting, HM14, is only six months away. So today is the day to make scheduling requests and book a room. And, for the first time, the biggest annual event in hospital medicine will be in Las Vegas.

HM14 will be held March 24-27 at Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas. Meeting registration is now open at www.hospitalmedicine2014.org. The early registration discount ends Jan. 26.

Who should attend HM14? Bring the whole team: hospitalists, pediatricians, academic hospitalists, general internists, family physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, administrators, and providers practicing in acute-care settings.

Movers and Shakers in Hospital Medicine

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, has been named to the board of directors and chair of the quality committee for IPC: The Hospitalist Company, based in North Hollywood, Calif. Dr. Wachter currently serves as director of the division of hospital medicine and associate chair of the department of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco. A well-known and respected authority on quality and safety, he was recognized with the John M. Eisenberg Award for excellence in patient safety in 2004. He also pens the Wachter’s World blog at www.wachtersworld.com.

Raffi Hodikian, MD, a hospitalist and longtime member of SHM, was named the 2013 Physician of the Year at Foothill Presbyterian Hospital in Glendora, Calif. “Not only was this the greatest honor of my career, but I thought it further reaffirmed the vital role hospitalists play in our community hospitals,” Dr. Hodikian said of the award.

Kimberly A. Bell, MD, is the new associate vice president of hospital medicine for Franciscan Health System (FHS) in Tacoma, Wash. In her new role, Dr. Bell will oversee hospitalist services at five of FHS’ seven area hospitals. FHS employs nearly 100 hospital medicine providers, including physicians and physician extenders.

Felix T. Cabrera, MD, has been named associate medical director at Guam Memorial Hospital (GMH) in Tamuning, Guam, after working as a hospitalist at GMH for more than two years. In his new role, Dr. Cabrera hopes to improve the technological infrastructure within the hospital. He will continue with his regular hospitalist rounds and private practice at International Health Providers Medical Group in Dededo, Guam. GMH is a 158-bed acute-care facility and the only hospital dedicated to civilian care on the island.

Troy Martin, MD, has been appointed chief medical officer for Questcare Hospitalists, based in Dallas. Dr. Martin comes to the Questcare executive team from the Medical Center of McKinney in McKinney, Texas, where he served as medical director of Questcare’s hospitalist program.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, has been named to the board of directors and chair of the quality committee for IPC: The Hospitalist Company, based in North Hollywood, Calif. Dr. Wachter currently serves as director of the division of hospital medicine and associate chair of the department of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco. A well-known and respected authority on quality and safety, he was recognized with the John M. Eisenberg Award for excellence in patient safety in 2004. He also pens the Wachter’s World blog at www.wachtersworld.com.

Raffi Hodikian, MD, a hospitalist and longtime member of SHM, was named the 2013 Physician of the Year at Foothill Presbyterian Hospital in Glendora, Calif. “Not only was this the greatest honor of my career, but I thought it further reaffirmed the vital role hospitalists play in our community hospitals,” Dr. Hodikian said of the award.

Kimberly A. Bell, MD, is the new associate vice president of hospital medicine for Franciscan Health System (FHS) in Tacoma, Wash. In her new role, Dr. Bell will oversee hospitalist services at five of FHS’ seven area hospitals. FHS employs nearly 100 hospital medicine providers, including physicians and physician extenders.

Felix T. Cabrera, MD, has been named associate medical director at Guam Memorial Hospital (GMH) in Tamuning, Guam, after working as a hospitalist at GMH for more than two years. In his new role, Dr. Cabrera hopes to improve the technological infrastructure within the hospital. He will continue with his regular hospitalist rounds and private practice at International Health Providers Medical Group in Dededo, Guam. GMH is a 158-bed acute-care facility and the only hospital dedicated to civilian care on the island.

Troy Martin, MD, has been appointed chief medical officer for Questcare Hospitalists, based in Dallas. Dr. Martin comes to the Questcare executive team from the Medical Center of McKinney in McKinney, Texas, where he served as medical director of Questcare’s hospitalist program.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, has been named to the board of directors and chair of the quality committee for IPC: The Hospitalist Company, based in North Hollywood, Calif. Dr. Wachter currently serves as director of the division of hospital medicine and associate chair of the department of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco. A well-known and respected authority on quality and safety, he was recognized with the John M. Eisenberg Award for excellence in patient safety in 2004. He also pens the Wachter’s World blog at www.wachtersworld.com.

Raffi Hodikian, MD, a hospitalist and longtime member of SHM, was named the 2013 Physician of the Year at Foothill Presbyterian Hospital in Glendora, Calif. “Not only was this the greatest honor of my career, but I thought it further reaffirmed the vital role hospitalists play in our community hospitals,” Dr. Hodikian said of the award.

Kimberly A. Bell, MD, is the new associate vice president of hospital medicine for Franciscan Health System (FHS) in Tacoma, Wash. In her new role, Dr. Bell will oversee hospitalist services at five of FHS’ seven area hospitals. FHS employs nearly 100 hospital medicine providers, including physicians and physician extenders.

Felix T. Cabrera, MD, has been named associate medical director at Guam Memorial Hospital (GMH) in Tamuning, Guam, after working as a hospitalist at GMH for more than two years. In his new role, Dr. Cabrera hopes to improve the technological infrastructure within the hospital. He will continue with his regular hospitalist rounds and private practice at International Health Providers Medical Group in Dededo, Guam. GMH is a 158-bed acute-care facility and the only hospital dedicated to civilian care on the island.

Troy Martin, MD, has been appointed chief medical officer for Questcare Hospitalists, based in Dallas. Dr. Martin comes to the Questcare executive team from the Medical Center of McKinney in McKinney, Texas, where he served as medical director of Questcare’s hospitalist program.

Nine Things Chronic-Pain Specialists Think Hospitalists Need To Know

In This Edition

9 Things: At a Glance

An occasional series providing specialty-specific advice for hospitalists from experts in the field.

- Recognize the differential diagnosis for pain exacerbation in a chronic opioid therapy (COT) patient/chronic pain patient.

- Know where the opioids are going.

- Sometimes stopping pills, rather than adding them, can cure pain.

- Take time to educate patients about methadone and its risk of mortality if not used as prescribed.

- A little local anesthetic (and some steroid) goes a long way.

- Addiction to opioids is not rare.

- Safely changing opioid regimens requires good math and good judgment.

- For a low-risk chronic pain patient on low-dose opioids, don’t change the regimen, even if the indication for opioids isn’t clear.

- If a patient has pain all the time, they need to be on a medication that works all the time.

The differential diagnosis for pain exacerbation in a chronic opioid therapy (COT) patient/chronic pain patient is:

- Worsening medical problem;

- New medical problem;

- Nonopioid problem (side effect);

- Opioid problem (resistance/tolerance/side effect); and

- Opioid-induced hyperalgesia.

The search for an etiology and treatment for chronic pain should not end, even if a patient is labeled with “chronic pain syndrome.” The patient could simply be chronically undiagnosed or on an incorrect therapy.

Know where the opioids are going.

Whether it’s auditing a prescription-monitoring program (PMP), checking a urine drug screen, or calling a pharmacist, try to ensure that chronic pain patients are taking the opioids as prescribed. A phone call to the primary opioid prescriber or chronic pain provider could save a busy hospitalist a lot of time.

Using PMP data can consume a lot of time. Typically, only prescribing providers can access PMPs, so delegating this responsibility to someone else is not possible. If your state PMP does not help, simply call the patient’s pharmacy and ask for the last three fill dates on an opioid prescription. This also works well in case the patient’s pharmacy doesn’t participate in a PMP or is delayed in uploading recent prescriber data. Many COT patients have an opioid treatment agreement with their prescriber and must use only one pharmacy to fill opioids.

In January 2013, the University of North Carolina Injury Prevention Center published an analysis of three years of North Carolina PMP data.1 Patients followed by providers who consistently used the state PMP were five times more likely to receive treatment for opioid dependence compared with patients of providers who never used the state PMP.1

Why go through all this trouble if a chronic pain specialist is also doing it? It’s good documentation and good care, like monitoring levels of transplant meds or making sure hemoglobin A1Cs are up to date and trending toward goal. It may only take one misused or diverted opioid pill to result in a serious adverse event.

Sometimes stopping pills, rather than adding them, can cure pain.

Many chronic pain patients accumulate a patchwork of pills (e.g. benzodiazepines, opioids, muscle relaxants, and antidepressants). Many interpret noxious symptoms associated with the drug burden as “uncontrolled pain.” Two conditions that might afflict the pain sufferer who takes multiple medications are opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) and medication-overuse headaches (MOH). They are uncommon but should be on a hospitalist’s differential for difficult-to-control chronic pain. Opioids commonly are implicated in causing MOH, a chronic headache occurring at least 15 days a month, four hours a day if untreated, and for at least three consecutive months. OIH is a nociceptive sensitization caused by opioids that can occur suddenly or insidiously.

If a drug isn’t absolutely necessary, stop it. If you and the patient start by agreeing to the shared goal of improving health, the conversation should go better. An axiom we learned from mentors at the University of Washington is: “There is no pain that cannot be made worse with inappropriate therapy.”

Take time to educate patients about methadone and its risk of mortality if not used as prescribed.

Methadone is less frequently prescribed than other opioids, yet it is more frequently associated with death from overdose. Though there is a risk of overdose and death with any opioid, managing methadone is more difficult. A desperate chronic pain patient may self-escalate their methadone without proper insight into the consequences.

Remember the logarithmic relationship methadone doses have with their morphine equivalency. The following highlights how deceiving the numbers are: 50 mg of methadone is about 100 mg of morphine-equivalent, but 100 mg of methadone is about 1,000 mg of morphine-equivalent, or 10 times as strong.

From 1999 to 2005, methadone-related deaths increased by 468%.2 If the patient doesn’t seem to understand these risks, they are not a good candidate for methadone treatment.

A little local anesthetic (and some steroid) goes a long way.

Hospitalists should offer an assortment of diagnostic and therapeutic injections to chronic pain patients. First, be sure you’ve done your due diligence:

- What procedures do you have privileges to do?

- Do you need to be proctored first?

- How do your local specialists feel about you doing injections?

In light of these considerations, hospitalists should be able to train and be credentialed to offer such procedures as trigger-point injections, joint injections (knees, shoulders), or even a peripheral nerve injection (e.g. lateral femoral cutaneous nerve or ilioinguinal nerve injection). Some hospitalists might even want to learn ultrasound-guided sacroiliac joint injections for chronic unexplained back pain.

Offering an indicated and effective injection is a good nonopioid option. And local anesthetic injections can help hospitalists establish an elusive diagnosis. For example, many patients spend years getting worked up for head and neck pain when dry-needling with a small volume (1 cc) of local anesthetic into a neck muscle trigger point can break their pain generator, eliminating their pain.

Addiction to opioids is not rare.

The use, misuse, and diversion of opioids and all the associated complications have appropriately received considerable media attention. A seminal paper by Porter and Jick titled “Addiction Is Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics” is one of many tipping points associated with the boom in opioid prescribing.3 Whether it’s a three-day supply of hydrocodone, 24 hours on a PCA, or an opioid rotation, any exposure to opioids can put a patient on the runway to addiction.

There are only 3,071 board-certified addiction specialists certified by the American Board of Addiction Medicine, so access to an addiction specialist might be difficult.4

Nonetheless, do not become complacent and just continue the opioid therapy in a difficult opioid-addicted patient. Express your concerns to the primary opioid prescriber, or help patients who don’t have an opioid prescriber get access and treatment. Otherwise, you have no choice but to taper the opioids.

Ideally, chronic pain management should be delivered in the outpatient arena where long-term monitoring can take place.

Safely changing opioid regimens requires good math and good judgment.

During training and practice, hospitalists become accustomed to rapidly analyze objective data, such as ABGs, ECGs, anion gaps, and vent settings. A hospitalist should become similarly efficient at calculating morphine equivalencies (cautiously with methadone and fentanyl), making dose reductions, and rotating opioids. The more comfortable you are with morphine equivalencies, the faster and safer you will be at rotating opioids. Whatever morphine-equivalence table you feel comfortable with is the one you should use consistently.

We see many providers who unwittingly take, for example, a patient who has become resistant to hydrocodone/acetaminophen 10/325 mg PO TID (30 mg of morphine) and convert them to oxycodone/acetaminophen 10/325 mg PO QID (60 mg of morphine—a doubling), when doubling could cause respiratory depression or a faster path to addiction and dependency.

But there are cases in which judgment should trump math, such as when converting from an IV to an oral regimen. We frequently see patients in the clinic requesting refills for more than 100 mg of hydromorphone because “that’s what I was on when I was hospitalized and on the pump.” If the IV-to-oral conversion leaves you prescribing high doses of oral opioids, plan for a rapid taper and a smooth handoff to the outpatient setting.

One strategy to decrease an error in math and judgment is to use IV PCAs as infrequently as possible if a patient isn’t post-operative and they are able to take oral meds. And never hesitate to consult with your inpatient pharmacist or a chronic pain specialist.

For a low-risk chronic pain patient on low-dose opioids, don’t change the regimen, even if the indication for opioids isn’t clear.

Although it is tempting to become an opioid prohibitionist, if a patient has been taking an opioid for years and is functioning, working, compliant, and has no risk factors for complications from COT, it is likely fine to continue their current regimen. Touch base with the primary opioid prescriber, and if you’re concerned, use some of the monitoring instruments described earlier (PMP, urine drug screen, opioid treatment agreement, pill counts).

If a patient has pain all the time, they need to be on a medication that works all the time.

A good pain history followed by a good neurological and mental health assessment is of incalculable value, especially because physicians often underestimate a patient’s pain intensity and its impact on a patient’s quality of life.5,6 A patient’s pain intensity, quality of life, and function can be dramatically improved by starting a long-acting medication for “constant pain.”

If a patient hurts “24 hours a day” and cannot function on hydrocodone/acetaminophen 10/325 QID, it’s probably because they are constantly reacting to spikes in pain and using a “some of the time” medicine to treat “all the time” pain. Switching to a long-acting medication—and it doesn’t have to be an opioid—could improve control and decrease how much narcotic the patient needs.

If you choose a long-acting opioid (in this case, you could try morphine sulphate extended-release 15 mg BID and satisfy 50% of the hydrocodone need), then you could titrate slowly upwards to where the patient would not need hydrocodone. If the patient still had uncontrolled pain, then either morphine is the wrong compound for them or they are benefiting from the “nonanalgesic properties” of the opioids.

Give the patient the benefit of the doubt; because of genetic polymorphisms, a patient may need several opioid rotations before the right opioid compound is found.

Dr. Schultz is a hospitalist and assistant professor in the department of internal medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. She is board-certified in hospice and palliative care and specializes in chronic pain management. Dr. Ajam is a hospitalist and a clinical assistant professor in the department of anesthesiology at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center and the Carolinas Pain Institute. He is board-certified in chronic pain management.

References

- Garrettson M, Ringwalt C. An evaluation of the North Carolina controlled substances reporting system: part II impact evaluation, January 2013. PDMP Center of Excellence website. Available at: http://pdmpexcellence.org/sites/all/pdfs/NC_control_sub_eval_pt_2.pdf. Accessed Sept. 3, 2013.

- Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu JQ, Murphy SL. Deaths: Final data for 2005, national vital statistics reports; Vol. 56 No. 10. Hyattsville, Md.: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008.

- Porter J, Jick H. Addiction rare in patients treated with narcotics. N Engl J Med. 1980;302(2):123.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine; personal communication, 2013.

- Mäntyselkä P, Kumpusalo E, Ahonen R, Takala J. Patients’ versus general practitioners’ assessments of pain intensity in primary care patients with non-cancer pain. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(473):995-997.

- Petersen MA, Larsen H, Pedersen L, Sonne N, Groenvold M. Assessing health-related quality of life in palliative care: comparing patient and physician assessments. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(8):1159-1166.

In This Edition

9 Things: At a Glance

An occasional series providing specialty-specific advice for hospitalists from experts in the field.

- Recognize the differential diagnosis for pain exacerbation in a chronic opioid therapy (COT) patient/chronic pain patient.

- Know where the opioids are going.

- Sometimes stopping pills, rather than adding them, can cure pain.

- Take time to educate patients about methadone and its risk of mortality if not used as prescribed.

- A little local anesthetic (and some steroid) goes a long way.

- Addiction to opioids is not rare.

- Safely changing opioid regimens requires good math and good judgment.

- For a low-risk chronic pain patient on low-dose opioids, don’t change the regimen, even if the indication for opioids isn’t clear.

- If a patient has pain all the time, they need to be on a medication that works all the time.

The differential diagnosis for pain exacerbation in a chronic opioid therapy (COT) patient/chronic pain patient is:

- Worsening medical problem;

- New medical problem;

- Nonopioid problem (side effect);

- Opioid problem (resistance/tolerance/side effect); and

- Opioid-induced hyperalgesia.

The search for an etiology and treatment for chronic pain should not end, even if a patient is labeled with “chronic pain syndrome.” The patient could simply be chronically undiagnosed or on an incorrect therapy.

Know where the opioids are going.

Whether it’s auditing a prescription-monitoring program (PMP), checking a urine drug screen, or calling a pharmacist, try to ensure that chronic pain patients are taking the opioids as prescribed. A phone call to the primary opioid prescriber or chronic pain provider could save a busy hospitalist a lot of time.

Using PMP data can consume a lot of time. Typically, only prescribing providers can access PMPs, so delegating this responsibility to someone else is not possible. If your state PMP does not help, simply call the patient’s pharmacy and ask for the last three fill dates on an opioid prescription. This also works well in case the patient’s pharmacy doesn’t participate in a PMP or is delayed in uploading recent prescriber data. Many COT patients have an opioid treatment agreement with their prescriber and must use only one pharmacy to fill opioids.

In January 2013, the University of North Carolina Injury Prevention Center published an analysis of three years of North Carolina PMP data.1 Patients followed by providers who consistently used the state PMP were five times more likely to receive treatment for opioid dependence compared with patients of providers who never used the state PMP.1

Why go through all this trouble if a chronic pain specialist is also doing it? It’s good documentation and good care, like monitoring levels of transplant meds or making sure hemoglobin A1Cs are up to date and trending toward goal. It may only take one misused or diverted opioid pill to result in a serious adverse event.

Sometimes stopping pills, rather than adding them, can cure pain.

Many chronic pain patients accumulate a patchwork of pills (e.g. benzodiazepines, opioids, muscle relaxants, and antidepressants). Many interpret noxious symptoms associated with the drug burden as “uncontrolled pain.” Two conditions that might afflict the pain sufferer who takes multiple medications are opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) and medication-overuse headaches (MOH). They are uncommon but should be on a hospitalist’s differential for difficult-to-control chronic pain. Opioids commonly are implicated in causing MOH, a chronic headache occurring at least 15 days a month, four hours a day if untreated, and for at least three consecutive months. OIH is a nociceptive sensitization caused by opioids that can occur suddenly or insidiously.

If a drug isn’t absolutely necessary, stop it. If you and the patient start by agreeing to the shared goal of improving health, the conversation should go better. An axiom we learned from mentors at the University of Washington is: “There is no pain that cannot be made worse with inappropriate therapy.”

Take time to educate patients about methadone and its risk of mortality if not used as prescribed.

Methadone is less frequently prescribed than other opioids, yet it is more frequently associated with death from overdose. Though there is a risk of overdose and death with any opioid, managing methadone is more difficult. A desperate chronic pain patient may self-escalate their methadone without proper insight into the consequences.

Remember the logarithmic relationship methadone doses have with their morphine equivalency. The following highlights how deceiving the numbers are: 50 mg of methadone is about 100 mg of morphine-equivalent, but 100 mg of methadone is about 1,000 mg of morphine-equivalent, or 10 times as strong.

From 1999 to 2005, methadone-related deaths increased by 468%.2 If the patient doesn’t seem to understand these risks, they are not a good candidate for methadone treatment.

A little local anesthetic (and some steroid) goes a long way.

Hospitalists should offer an assortment of diagnostic and therapeutic injections to chronic pain patients. First, be sure you’ve done your due diligence:

- What procedures do you have privileges to do?

- Do you need to be proctored first?

- How do your local specialists feel about you doing injections?

In light of these considerations, hospitalists should be able to train and be credentialed to offer such procedures as trigger-point injections, joint injections (knees, shoulders), or even a peripheral nerve injection (e.g. lateral femoral cutaneous nerve or ilioinguinal nerve injection). Some hospitalists might even want to learn ultrasound-guided sacroiliac joint injections for chronic unexplained back pain.

Offering an indicated and effective injection is a good nonopioid option. And local anesthetic injections can help hospitalists establish an elusive diagnosis. For example, many patients spend years getting worked up for head and neck pain when dry-needling with a small volume (1 cc) of local anesthetic into a neck muscle trigger point can break their pain generator, eliminating their pain.

Addiction to opioids is not rare.

The use, misuse, and diversion of opioids and all the associated complications have appropriately received considerable media attention. A seminal paper by Porter and Jick titled “Addiction Is Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics” is one of many tipping points associated with the boom in opioid prescribing.3 Whether it’s a three-day supply of hydrocodone, 24 hours on a PCA, or an opioid rotation, any exposure to opioids can put a patient on the runway to addiction.

There are only 3,071 board-certified addiction specialists certified by the American Board of Addiction Medicine, so access to an addiction specialist might be difficult.4

Nonetheless, do not become complacent and just continue the opioid therapy in a difficult opioid-addicted patient. Express your concerns to the primary opioid prescriber, or help patients who don’t have an opioid prescriber get access and treatment. Otherwise, you have no choice but to taper the opioids.

Ideally, chronic pain management should be delivered in the outpatient arena where long-term monitoring can take place.

Safely changing opioid regimens requires good math and good judgment.

During training and practice, hospitalists become accustomed to rapidly analyze objective data, such as ABGs, ECGs, anion gaps, and vent settings. A hospitalist should become similarly efficient at calculating morphine equivalencies (cautiously with methadone and fentanyl), making dose reductions, and rotating opioids. The more comfortable you are with morphine equivalencies, the faster and safer you will be at rotating opioids. Whatever morphine-equivalence table you feel comfortable with is the one you should use consistently.

We see many providers who unwittingly take, for example, a patient who has become resistant to hydrocodone/acetaminophen 10/325 mg PO TID (30 mg of morphine) and convert them to oxycodone/acetaminophen 10/325 mg PO QID (60 mg of morphine—a doubling), when doubling could cause respiratory depression or a faster path to addiction and dependency.

But there are cases in which judgment should trump math, such as when converting from an IV to an oral regimen. We frequently see patients in the clinic requesting refills for more than 100 mg of hydromorphone because “that’s what I was on when I was hospitalized and on the pump.” If the IV-to-oral conversion leaves you prescribing high doses of oral opioids, plan for a rapid taper and a smooth handoff to the outpatient setting.

One strategy to decrease an error in math and judgment is to use IV PCAs as infrequently as possible if a patient isn’t post-operative and they are able to take oral meds. And never hesitate to consult with your inpatient pharmacist or a chronic pain specialist.

For a low-risk chronic pain patient on low-dose opioids, don’t change the regimen, even if the indication for opioids isn’t clear.

Although it is tempting to become an opioid prohibitionist, if a patient has been taking an opioid for years and is functioning, working, compliant, and has no risk factors for complications from COT, it is likely fine to continue their current regimen. Touch base with the primary opioid prescriber, and if you’re concerned, use some of the monitoring instruments described earlier (PMP, urine drug screen, opioid treatment agreement, pill counts).

If a patient has pain all the time, they need to be on a medication that works all the time.

A good pain history followed by a good neurological and mental health assessment is of incalculable value, especially because physicians often underestimate a patient’s pain intensity and its impact on a patient’s quality of life.5,6 A patient’s pain intensity, quality of life, and function can be dramatically improved by starting a long-acting medication for “constant pain.”

If a patient hurts “24 hours a day” and cannot function on hydrocodone/acetaminophen 10/325 QID, it’s probably because they are constantly reacting to spikes in pain and using a “some of the time” medicine to treat “all the time” pain. Switching to a long-acting medication—and it doesn’t have to be an opioid—could improve control and decrease how much narcotic the patient needs.

If you choose a long-acting opioid (in this case, you could try morphine sulphate extended-release 15 mg BID and satisfy 50% of the hydrocodone need), then you could titrate slowly upwards to where the patient would not need hydrocodone. If the patient still had uncontrolled pain, then either morphine is the wrong compound for them or they are benefiting from the “nonanalgesic properties” of the opioids.

Give the patient the benefit of the doubt; because of genetic polymorphisms, a patient may need several opioid rotations before the right opioid compound is found.

Dr. Schultz is a hospitalist and assistant professor in the department of internal medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. She is board-certified in hospice and palliative care and specializes in chronic pain management. Dr. Ajam is a hospitalist and a clinical assistant professor in the department of anesthesiology at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center and the Carolinas Pain Institute. He is board-certified in chronic pain management.

References

- Garrettson M, Ringwalt C. An evaluation of the North Carolina controlled substances reporting system: part II impact evaluation, January 2013. PDMP Center of Excellence website. Available at: http://pdmpexcellence.org/sites/all/pdfs/NC_control_sub_eval_pt_2.pdf. Accessed Sept. 3, 2013.

- Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu JQ, Murphy SL. Deaths: Final data for 2005, national vital statistics reports; Vol. 56 No. 10. Hyattsville, Md.: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008.

- Porter J, Jick H. Addiction rare in patients treated with narcotics. N Engl J Med. 1980;302(2):123.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine; personal communication, 2013.

- Mäntyselkä P, Kumpusalo E, Ahonen R, Takala J. Patients’ versus general practitioners’ assessments of pain intensity in primary care patients with non-cancer pain. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(473):995-997.

- Petersen MA, Larsen H, Pedersen L, Sonne N, Groenvold M. Assessing health-related quality of life in palliative care: comparing patient and physician assessments. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(8):1159-1166.

In This Edition

9 Things: At a Glance

An occasional series providing specialty-specific advice for hospitalists from experts in the field.

- Recognize the differential diagnosis for pain exacerbation in a chronic opioid therapy (COT) patient/chronic pain patient.

- Know where the opioids are going.

- Sometimes stopping pills, rather than adding them, can cure pain.

- Take time to educate patients about methadone and its risk of mortality if not used as prescribed.

- A little local anesthetic (and some steroid) goes a long way.

- Addiction to opioids is not rare.

- Safely changing opioid regimens requires good math and good judgment.

- For a low-risk chronic pain patient on low-dose opioids, don’t change the regimen, even if the indication for opioids isn’t clear.

- If a patient has pain all the time, they need to be on a medication that works all the time.

The differential diagnosis for pain exacerbation in a chronic opioid therapy (COT) patient/chronic pain patient is:

- Worsening medical problem;

- New medical problem;

- Nonopioid problem (side effect);

- Opioid problem (resistance/tolerance/side effect); and

- Opioid-induced hyperalgesia.

The search for an etiology and treatment for chronic pain should not end, even if a patient is labeled with “chronic pain syndrome.” The patient could simply be chronically undiagnosed or on an incorrect therapy.

Know where the opioids are going.

Whether it’s auditing a prescription-monitoring program (PMP), checking a urine drug screen, or calling a pharmacist, try to ensure that chronic pain patients are taking the opioids as prescribed. A phone call to the primary opioid prescriber or chronic pain provider could save a busy hospitalist a lot of time.

Using PMP data can consume a lot of time. Typically, only prescribing providers can access PMPs, so delegating this responsibility to someone else is not possible. If your state PMP does not help, simply call the patient’s pharmacy and ask for the last three fill dates on an opioid prescription. This also works well in case the patient’s pharmacy doesn’t participate in a PMP or is delayed in uploading recent prescriber data. Many COT patients have an opioid treatment agreement with their prescriber and must use only one pharmacy to fill opioids.

In January 2013, the University of North Carolina Injury Prevention Center published an analysis of three years of North Carolina PMP data.1 Patients followed by providers who consistently used the state PMP were five times more likely to receive treatment for opioid dependence compared with patients of providers who never used the state PMP.1

Why go through all this trouble if a chronic pain specialist is also doing it? It’s good documentation and good care, like monitoring levels of transplant meds or making sure hemoglobin A1Cs are up to date and trending toward goal. It may only take one misused or diverted opioid pill to result in a serious adverse event.

Sometimes stopping pills, rather than adding them, can cure pain.

Many chronic pain patients accumulate a patchwork of pills (e.g. benzodiazepines, opioids, muscle relaxants, and antidepressants). Many interpret noxious symptoms associated with the drug burden as “uncontrolled pain.” Two conditions that might afflict the pain sufferer who takes multiple medications are opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) and medication-overuse headaches (MOH). They are uncommon but should be on a hospitalist’s differential for difficult-to-control chronic pain. Opioids commonly are implicated in causing MOH, a chronic headache occurring at least 15 days a month, four hours a day if untreated, and for at least three consecutive months. OIH is a nociceptive sensitization caused by opioids that can occur suddenly or insidiously.

If a drug isn’t absolutely necessary, stop it. If you and the patient start by agreeing to the shared goal of improving health, the conversation should go better. An axiom we learned from mentors at the University of Washington is: “There is no pain that cannot be made worse with inappropriate therapy.”

Take time to educate patients about methadone and its risk of mortality if not used as prescribed.

Methadone is less frequently prescribed than other opioids, yet it is more frequently associated with death from overdose. Though there is a risk of overdose and death with any opioid, managing methadone is more difficult. A desperate chronic pain patient may self-escalate their methadone without proper insight into the consequences.

Remember the logarithmic relationship methadone doses have with their morphine equivalency. The following highlights how deceiving the numbers are: 50 mg of methadone is about 100 mg of morphine-equivalent, but 100 mg of methadone is about 1,000 mg of morphine-equivalent, or 10 times as strong.

From 1999 to 2005, methadone-related deaths increased by 468%.2 If the patient doesn’t seem to understand these risks, they are not a good candidate for methadone treatment.

A little local anesthetic (and some steroid) goes a long way.

Hospitalists should offer an assortment of diagnostic and therapeutic injections to chronic pain patients. First, be sure you’ve done your due diligence:

- What procedures do you have privileges to do?

- Do you need to be proctored first?

- How do your local specialists feel about you doing injections?

In light of these considerations, hospitalists should be able to train and be credentialed to offer such procedures as trigger-point injections, joint injections (knees, shoulders), or even a peripheral nerve injection (e.g. lateral femoral cutaneous nerve or ilioinguinal nerve injection). Some hospitalists might even want to learn ultrasound-guided sacroiliac joint injections for chronic unexplained back pain.

Offering an indicated and effective injection is a good nonopioid option. And local anesthetic injections can help hospitalists establish an elusive diagnosis. For example, many patients spend years getting worked up for head and neck pain when dry-needling with a small volume (1 cc) of local anesthetic into a neck muscle trigger point can break their pain generator, eliminating their pain.

Addiction to opioids is not rare.

The use, misuse, and diversion of opioids and all the associated complications have appropriately received considerable media attention. A seminal paper by Porter and Jick titled “Addiction Is Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics” is one of many tipping points associated with the boom in opioid prescribing.3 Whether it’s a three-day supply of hydrocodone, 24 hours on a PCA, or an opioid rotation, any exposure to opioids can put a patient on the runway to addiction.

There are only 3,071 board-certified addiction specialists certified by the American Board of Addiction Medicine, so access to an addiction specialist might be difficult.4

Nonetheless, do not become complacent and just continue the opioid therapy in a difficult opioid-addicted patient. Express your concerns to the primary opioid prescriber, or help patients who don’t have an opioid prescriber get access and treatment. Otherwise, you have no choice but to taper the opioids.

Ideally, chronic pain management should be delivered in the outpatient arena where long-term monitoring can take place.

Safely changing opioid regimens requires good math and good judgment.

During training and practice, hospitalists become accustomed to rapidly analyze objective data, such as ABGs, ECGs, anion gaps, and vent settings. A hospitalist should become similarly efficient at calculating morphine equivalencies (cautiously with methadone and fentanyl), making dose reductions, and rotating opioids. The more comfortable you are with morphine equivalencies, the faster and safer you will be at rotating opioids. Whatever morphine-equivalence table you feel comfortable with is the one you should use consistently.

We see many providers who unwittingly take, for example, a patient who has become resistant to hydrocodone/acetaminophen 10/325 mg PO TID (30 mg of morphine) and convert them to oxycodone/acetaminophen 10/325 mg PO QID (60 mg of morphine—a doubling), when doubling could cause respiratory depression or a faster path to addiction and dependency.

But there are cases in which judgment should trump math, such as when converting from an IV to an oral regimen. We frequently see patients in the clinic requesting refills for more than 100 mg of hydromorphone because “that’s what I was on when I was hospitalized and on the pump.” If the IV-to-oral conversion leaves you prescribing high doses of oral opioids, plan for a rapid taper and a smooth handoff to the outpatient setting.

One strategy to decrease an error in math and judgment is to use IV PCAs as infrequently as possible if a patient isn’t post-operative and they are able to take oral meds. And never hesitate to consult with your inpatient pharmacist or a chronic pain specialist.

For a low-risk chronic pain patient on low-dose opioids, don’t change the regimen, even if the indication for opioids isn’t clear.

Although it is tempting to become an opioid prohibitionist, if a patient has been taking an opioid for years and is functioning, working, compliant, and has no risk factors for complications from COT, it is likely fine to continue their current regimen. Touch base with the primary opioid prescriber, and if you’re concerned, use some of the monitoring instruments described earlier (PMP, urine drug screen, opioid treatment agreement, pill counts).

If a patient has pain all the time, they need to be on a medication that works all the time.

A good pain history followed by a good neurological and mental health assessment is of incalculable value, especially because physicians often underestimate a patient’s pain intensity and its impact on a patient’s quality of life.5,6 A patient’s pain intensity, quality of life, and function can be dramatically improved by starting a long-acting medication for “constant pain.”

If a patient hurts “24 hours a day” and cannot function on hydrocodone/acetaminophen 10/325 QID, it’s probably because they are constantly reacting to spikes in pain and using a “some of the time” medicine to treat “all the time” pain. Switching to a long-acting medication—and it doesn’t have to be an opioid—could improve control and decrease how much narcotic the patient needs.

If you choose a long-acting opioid (in this case, you could try morphine sulphate extended-release 15 mg BID and satisfy 50% of the hydrocodone need), then you could titrate slowly upwards to where the patient would not need hydrocodone. If the patient still had uncontrolled pain, then either morphine is the wrong compound for them or they are benefiting from the “nonanalgesic properties” of the opioids.

Give the patient the benefit of the doubt; because of genetic polymorphisms, a patient may need several opioid rotations before the right opioid compound is found.

Dr. Schultz is a hospitalist and assistant professor in the department of internal medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. She is board-certified in hospice and palliative care and specializes in chronic pain management. Dr. Ajam is a hospitalist and a clinical assistant professor in the department of anesthesiology at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center and the Carolinas Pain Institute. He is board-certified in chronic pain management.

References

- Garrettson M, Ringwalt C. An evaluation of the North Carolina controlled substances reporting system: part II impact evaluation, January 2013. PDMP Center of Excellence website. Available at: http://pdmpexcellence.org/sites/all/pdfs/NC_control_sub_eval_pt_2.pdf. Accessed Sept. 3, 2013.

- Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu JQ, Murphy SL. Deaths: Final data for 2005, national vital statistics reports; Vol. 56 No. 10. Hyattsville, Md.: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008.

- Porter J, Jick H. Addiction rare in patients treated with narcotics. N Engl J Med. 1980;302(2):123.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine; personal communication, 2013.

- Mäntyselkä P, Kumpusalo E, Ahonen R, Takala J. Patients’ versus general practitioners’ assessments of pain intensity in primary care patients with non-cancer pain. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(473):995-997.

- Petersen MA, Larsen H, Pedersen L, Sonne N, Groenvold M. Assessing health-related quality of life in palliative care: comparing patient and physician assessments. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(8):1159-1166.

Observation Status Not So Well-Defined in Hospitals

New research suggests use of the designation "observation status" for admitted hospital patients varies in clinical practice, despite rigid criteria the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) uses to define the term.

CMS defines observation status as "well-defined sets of specific, clinically appropriate services." In most cases, the status applies to inpatient stays of less than 24 hours. Longer than 48 hours is dubbed "rare and exceptional" by the federal agency.

But in the report, “Hospitalized But Not Admitted: Characteristics of Patients With ‘Observation Status’ at an Academic Medical Center," lead author and hospitalist Ann Sheehy, MD, MS, of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison found that patients' mean length of stay (LOS) in observation was 33.3 hours, but it was longer than 48 hours in 16.5% of cases. Dr. Sheehy adds that 1,141 distinct observation diagnosis codes were used for observation stays during the study period, which ran from July 1, 2010, to Dec. 31, 2011.

"What CMS has as a definition for observation status is clearly not what's happening in clinical practice, based on the length of stay and the wide variety of diagnosis codes," Dr. Sheehy says. "We had over 1,000 diagnosis codes for something CMS says is well-defined."

The issue is of particular note to hospital medicine groups as observation status disproportionately affects the general-medicine population, Dr. Sheehy says. Just over 52% of all observation stays in the study were adult general-medicine patients.

The paper adds that while the cost per encounter for observation care was less than that for inpatient care, the average reimbursement for observation care failed to cover it. The net loss per encounter for an observation stay was $331, compared with a net gain of $2,163 for an inpatient stay.

"We don't want to have hospitals operating on a huge profit margin," Dr. Sheehy says, but "you can't have hospitals delivering care at a loss consistently and have them stay solvent. It's just not going to work."

Visit our website for more information on observation status rules.

New research suggests use of the designation "observation status" for admitted hospital patients varies in clinical practice, despite rigid criteria the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) uses to define the term.

CMS defines observation status as "well-defined sets of specific, clinically appropriate services." In most cases, the status applies to inpatient stays of less than 24 hours. Longer than 48 hours is dubbed "rare and exceptional" by the federal agency.

But in the report, “Hospitalized But Not Admitted: Characteristics of Patients With ‘Observation Status’ at an Academic Medical Center," lead author and hospitalist Ann Sheehy, MD, MS, of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison found that patients' mean length of stay (LOS) in observation was 33.3 hours, but it was longer than 48 hours in 16.5% of cases. Dr. Sheehy adds that 1,141 distinct observation diagnosis codes were used for observation stays during the study period, which ran from July 1, 2010, to Dec. 31, 2011.

"What CMS has as a definition for observation status is clearly not what's happening in clinical practice, based on the length of stay and the wide variety of diagnosis codes," Dr. Sheehy says. "We had over 1,000 diagnosis codes for something CMS says is well-defined."

The issue is of particular note to hospital medicine groups as observation status disproportionately affects the general-medicine population, Dr. Sheehy says. Just over 52% of all observation stays in the study were adult general-medicine patients.

The paper adds that while the cost per encounter for observation care was less than that for inpatient care, the average reimbursement for observation care failed to cover it. The net loss per encounter for an observation stay was $331, compared with a net gain of $2,163 for an inpatient stay.

"We don't want to have hospitals operating on a huge profit margin," Dr. Sheehy says, but "you can't have hospitals delivering care at a loss consistently and have them stay solvent. It's just not going to work."

Visit our website for more information on observation status rules.

New research suggests use of the designation "observation status" for admitted hospital patients varies in clinical practice, despite rigid criteria the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) uses to define the term.

CMS defines observation status as "well-defined sets of specific, clinically appropriate services." In most cases, the status applies to inpatient stays of less than 24 hours. Longer than 48 hours is dubbed "rare and exceptional" by the federal agency.

But in the report, “Hospitalized But Not Admitted: Characteristics of Patients With ‘Observation Status’ at an Academic Medical Center," lead author and hospitalist Ann Sheehy, MD, MS, of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison found that patients' mean length of stay (LOS) in observation was 33.3 hours, but it was longer than 48 hours in 16.5% of cases. Dr. Sheehy adds that 1,141 distinct observation diagnosis codes were used for observation stays during the study period, which ran from July 1, 2010, to Dec. 31, 2011.

"What CMS has as a definition for observation status is clearly not what's happening in clinical practice, based on the length of stay and the wide variety of diagnosis codes," Dr. Sheehy says. "We had over 1,000 diagnosis codes for something CMS says is well-defined."

The issue is of particular note to hospital medicine groups as observation status disproportionately affects the general-medicine population, Dr. Sheehy says. Just over 52% of all observation stays in the study were adult general-medicine patients.

The paper adds that while the cost per encounter for observation care was less than that for inpatient care, the average reimbursement for observation care failed to cover it. The net loss per encounter for an observation stay was $331, compared with a net gain of $2,163 for an inpatient stay.