User login

Oklahoma Hospitalist Discusses Medical Center Devastation, Community Response

Click here to listen to more of our interview with Dr. Womble

Click here to listen to more of our interview with Dr. Womble

Click here to listen to more of our interview with Dr. Womble

Devastating Superstorm Gone, But Not Forgotten in Moore, Okla.

–Joe R. Womble, MD

The first bit of feedback was fantastic: Everyone who had been inside the hospital—roughly 200 to 300 people, including 30 patients—had survived.

“Everyone was fine,” he said. “All the patients and staff, no one got injured. I was thinking that either the hospital was missed by the storm or that it must not have really damaged it very significantly.”

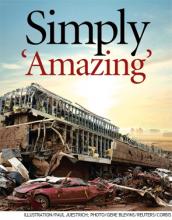

Unfortunately, the hospital was not OK. He watched as local TV painted a very different picture.

“They started showing aerial shots and I was just shocked. My jaw was just dropped,” Dr. Womble said. “The main entrance that I go in every day was literally stacked with three or four cars deep. A huge stack of about 30 cars was piled up on the main entrance, essentially.”

It was as though they were “toy cars.”

The May 20 tornado, a two-mile-wide superstorm boasting 200-mph winds that struck just south of Oklahoma City, claimed 24 lives and left the regional health system with a void in its network. It also left hospitalists mourning the loss of the place they called a second home several times a week. About a week after the storm, officials announced that Moore Medical Center would have to be demolished.

Miraculous Moments

Despite the terrible events, hospitalists and hospital officials were astounded by the good fortune of the hospital’s inhabitants. Dr. Womble said about 100 people from nearby neighborhoods and businesses used the hospital as shelter.

Senthil Raju, MD, a hospitalist who had done rounds at Moore Medical earlier that day, said the protocol was to take shelter in the hallways. But at some point, probably only minutes before the storm hit, the chief nurse and the house supervisor made the decision to move all the patients to the ground floor because they were in “reasonably stable condition,” according to Dr. Womble, who relayed accounts by staffers who were there. Most of the people in the hospital rode out the storm in the first-floor cafeteria.

After the storm, patient rooms on the second floor were either no longer there or had been reduced to their steel innards.

The decision to move everyone undoubtedly saved lives. “If any of our patients stayed there, they’re probably all dead,” Dr. Raju said.

David Whitaker, CEO of Norman Regional Health System, which includes Moore Medical, marveled at the outcome.

“We had some bumps and bruises, some scratches, but no major lacerations, no broken bones, no injuries that people couldn’t ambulate. It’s totally amazing,” he said. “The leadership that was in place, the employees that were working at that time, they sprang into action, they took command and control of the situation. They got people into the proper areas.”

Dr. Womble said hospital staff at Moore Medical had still more amazing stories of death-defiance. They told him 30 people refused to leave the chapel. Somehow, the chapel remained intact, even though the hospital all around it was destroyed. Whitaker confirmed this.

One woman in active labor was kept in a second-floor operating room—which the medical staff thought was the best place for her, all things considered. Nurses covered the woman with pillows, blankets, and their own bodies as the tornado barreled through the town. She survived and gave birth to a boy several hours later. The parents gave him the middle name Emmanuel, which means “God is with us.”

As the tornado approached, an elderly volunteer had gone outside to get something from a van he used to transport elderly patients to and from a physical therapy program. “Nobody inside knew he had gone outside,” Dr. Womble said. By the time he tried to get back in, the power had gone out, and the doors wouldn’t open. He huddled behind a concrete pillar and ended up with just one minor laceration.

Patients eventually were taken to another hospital, Norman’s HealthPlex, about five miles south. Both Dr. Womble and Dr. Raju have begun working full time at the HealthPlex.

Dr. Raju said that he avoided being at Moore Medical during the tornado only by a turn of luck. He normally rounds at Moore in the afternoon and at the HealthPlex in the morning. But on that day, there were three new admissions at Moore, and only one at HealthPlex. So he went to Moore first, and was gone by the time the tornado hit.

“So lucky,” he said.

–David Whitaker, CEO of Norman Regional Health System

The Aftermath

It remains to be seen what kind of medical facility will be built to replace Moore Medical Center.

“Nobody knows what will happen next, but a lot of us speculate that they will not rebuild an inpatient facility,” said Dr. Womble, who had worked at Moore Medical Center for four years.

Whitaker said the first priority was to re-establish the clinics located at Moore Medical, and that has been done. The next step is, possibly, a temporary building in Moore for urgent care. The long-term plan remains in the discussion phase.

“We’ve already started having some meetings,” Whitaker said. “We’re going to determine what type of facility, what service levels it will be offering as we go back.”

It’s hard knowing that his hospital is no longer there, Dr. Raju said.

“We are going to miss it,” he said. “It’s unimaginable.”

Dr. Womble said those first few hours, when he wasn’t sure of where he’d be working, were difficult. He struggles to describe the feeling of not being able to provide care at his hospital at the time it’s most needed.

“It’s really hard to put it into words,” he said. “It’s the only hospital in that city, and it’s just me and my partner to take care of virtually everyone that comes in with any kind of medical problem. I definitely feel a tie to the community.

“It’s devastating. What is the rest of the city going to do for their hospital care? They essentially will not have a hospital in their city. They’ll have to drive to another city for care.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

–Joe R. Womble, MD

The first bit of feedback was fantastic: Everyone who had been inside the hospital—roughly 200 to 300 people, including 30 patients—had survived.

“Everyone was fine,” he said. “All the patients and staff, no one got injured. I was thinking that either the hospital was missed by the storm or that it must not have really damaged it very significantly.”

Unfortunately, the hospital was not OK. He watched as local TV painted a very different picture.

“They started showing aerial shots and I was just shocked. My jaw was just dropped,” Dr. Womble said. “The main entrance that I go in every day was literally stacked with three or four cars deep. A huge stack of about 30 cars was piled up on the main entrance, essentially.”

It was as though they were “toy cars.”

The May 20 tornado, a two-mile-wide superstorm boasting 200-mph winds that struck just south of Oklahoma City, claimed 24 lives and left the regional health system with a void in its network. It also left hospitalists mourning the loss of the place they called a second home several times a week. About a week after the storm, officials announced that Moore Medical Center would have to be demolished.

Miraculous Moments

Despite the terrible events, hospitalists and hospital officials were astounded by the good fortune of the hospital’s inhabitants. Dr. Womble said about 100 people from nearby neighborhoods and businesses used the hospital as shelter.

Senthil Raju, MD, a hospitalist who had done rounds at Moore Medical earlier that day, said the protocol was to take shelter in the hallways. But at some point, probably only minutes before the storm hit, the chief nurse and the house supervisor made the decision to move all the patients to the ground floor because they were in “reasonably stable condition,” according to Dr. Womble, who relayed accounts by staffers who were there. Most of the people in the hospital rode out the storm in the first-floor cafeteria.

After the storm, patient rooms on the second floor were either no longer there or had been reduced to their steel innards.

The decision to move everyone undoubtedly saved lives. “If any of our patients stayed there, they’re probably all dead,” Dr. Raju said.

David Whitaker, CEO of Norman Regional Health System, which includes Moore Medical, marveled at the outcome.

“We had some bumps and bruises, some scratches, but no major lacerations, no broken bones, no injuries that people couldn’t ambulate. It’s totally amazing,” he said. “The leadership that was in place, the employees that were working at that time, they sprang into action, they took command and control of the situation. They got people into the proper areas.”

Dr. Womble said hospital staff at Moore Medical had still more amazing stories of death-defiance. They told him 30 people refused to leave the chapel. Somehow, the chapel remained intact, even though the hospital all around it was destroyed. Whitaker confirmed this.

One woman in active labor was kept in a second-floor operating room—which the medical staff thought was the best place for her, all things considered. Nurses covered the woman with pillows, blankets, and their own bodies as the tornado barreled through the town. She survived and gave birth to a boy several hours later. The parents gave him the middle name Emmanuel, which means “God is with us.”

As the tornado approached, an elderly volunteer had gone outside to get something from a van he used to transport elderly patients to and from a physical therapy program. “Nobody inside knew he had gone outside,” Dr. Womble said. By the time he tried to get back in, the power had gone out, and the doors wouldn’t open. He huddled behind a concrete pillar and ended up with just one minor laceration.

Patients eventually were taken to another hospital, Norman’s HealthPlex, about five miles south. Both Dr. Womble and Dr. Raju have begun working full time at the HealthPlex.

Dr. Raju said that he avoided being at Moore Medical during the tornado only by a turn of luck. He normally rounds at Moore in the afternoon and at the HealthPlex in the morning. But on that day, there were three new admissions at Moore, and only one at HealthPlex. So he went to Moore first, and was gone by the time the tornado hit.

“So lucky,” he said.

–David Whitaker, CEO of Norman Regional Health System

The Aftermath

It remains to be seen what kind of medical facility will be built to replace Moore Medical Center.

“Nobody knows what will happen next, but a lot of us speculate that they will not rebuild an inpatient facility,” said Dr. Womble, who had worked at Moore Medical Center for four years.

Whitaker said the first priority was to re-establish the clinics located at Moore Medical, and that has been done. The next step is, possibly, a temporary building in Moore for urgent care. The long-term plan remains in the discussion phase.

“We’ve already started having some meetings,” Whitaker said. “We’re going to determine what type of facility, what service levels it will be offering as we go back.”

It’s hard knowing that his hospital is no longer there, Dr. Raju said.

“We are going to miss it,” he said. “It’s unimaginable.”

Dr. Womble said those first few hours, when he wasn’t sure of where he’d be working, were difficult. He struggles to describe the feeling of not being able to provide care at his hospital at the time it’s most needed.

“It’s really hard to put it into words,” he said. “It’s the only hospital in that city, and it’s just me and my partner to take care of virtually everyone that comes in with any kind of medical problem. I definitely feel a tie to the community.

“It’s devastating. What is the rest of the city going to do for their hospital care? They essentially will not have a hospital in their city. They’ll have to drive to another city for care.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

–Joe R. Womble, MD

The first bit of feedback was fantastic: Everyone who had been inside the hospital—roughly 200 to 300 people, including 30 patients—had survived.

“Everyone was fine,” he said. “All the patients and staff, no one got injured. I was thinking that either the hospital was missed by the storm or that it must not have really damaged it very significantly.”

Unfortunately, the hospital was not OK. He watched as local TV painted a very different picture.

“They started showing aerial shots and I was just shocked. My jaw was just dropped,” Dr. Womble said. “The main entrance that I go in every day was literally stacked with three or four cars deep. A huge stack of about 30 cars was piled up on the main entrance, essentially.”

It was as though they were “toy cars.”

The May 20 tornado, a two-mile-wide superstorm boasting 200-mph winds that struck just south of Oklahoma City, claimed 24 lives and left the regional health system with a void in its network. It also left hospitalists mourning the loss of the place they called a second home several times a week. About a week after the storm, officials announced that Moore Medical Center would have to be demolished.

Miraculous Moments

Despite the terrible events, hospitalists and hospital officials were astounded by the good fortune of the hospital’s inhabitants. Dr. Womble said about 100 people from nearby neighborhoods and businesses used the hospital as shelter.

Senthil Raju, MD, a hospitalist who had done rounds at Moore Medical earlier that day, said the protocol was to take shelter in the hallways. But at some point, probably only minutes before the storm hit, the chief nurse and the house supervisor made the decision to move all the patients to the ground floor because they were in “reasonably stable condition,” according to Dr. Womble, who relayed accounts by staffers who were there. Most of the people in the hospital rode out the storm in the first-floor cafeteria.

After the storm, patient rooms on the second floor were either no longer there or had been reduced to their steel innards.

The decision to move everyone undoubtedly saved lives. “If any of our patients stayed there, they’re probably all dead,” Dr. Raju said.

David Whitaker, CEO of Norman Regional Health System, which includes Moore Medical, marveled at the outcome.

“We had some bumps and bruises, some scratches, but no major lacerations, no broken bones, no injuries that people couldn’t ambulate. It’s totally amazing,” he said. “The leadership that was in place, the employees that were working at that time, they sprang into action, they took command and control of the situation. They got people into the proper areas.”

Dr. Womble said hospital staff at Moore Medical had still more amazing stories of death-defiance. They told him 30 people refused to leave the chapel. Somehow, the chapel remained intact, even though the hospital all around it was destroyed. Whitaker confirmed this.

One woman in active labor was kept in a second-floor operating room—which the medical staff thought was the best place for her, all things considered. Nurses covered the woman with pillows, blankets, and their own bodies as the tornado barreled through the town. She survived and gave birth to a boy several hours later. The parents gave him the middle name Emmanuel, which means “God is with us.”

As the tornado approached, an elderly volunteer had gone outside to get something from a van he used to transport elderly patients to and from a physical therapy program. “Nobody inside knew he had gone outside,” Dr. Womble said. By the time he tried to get back in, the power had gone out, and the doors wouldn’t open. He huddled behind a concrete pillar and ended up with just one minor laceration.

Patients eventually were taken to another hospital, Norman’s HealthPlex, about five miles south. Both Dr. Womble and Dr. Raju have begun working full time at the HealthPlex.

Dr. Raju said that he avoided being at Moore Medical during the tornado only by a turn of luck. He normally rounds at Moore in the afternoon and at the HealthPlex in the morning. But on that day, there were three new admissions at Moore, and only one at HealthPlex. So he went to Moore first, and was gone by the time the tornado hit.

“So lucky,” he said.

–David Whitaker, CEO of Norman Regional Health System

The Aftermath

It remains to be seen what kind of medical facility will be built to replace Moore Medical Center.

“Nobody knows what will happen next, but a lot of us speculate that they will not rebuild an inpatient facility,” said Dr. Womble, who had worked at Moore Medical Center for four years.

Whitaker said the first priority was to re-establish the clinics located at Moore Medical, and that has been done. The next step is, possibly, a temporary building in Moore for urgent care. The long-term plan remains in the discussion phase.

“We’ve already started having some meetings,” Whitaker said. “We’re going to determine what type of facility, what service levels it will be offering as we go back.”

It’s hard knowing that his hospital is no longer there, Dr. Raju said.

“We are going to miss it,” he said. “It’s unimaginable.”

Dr. Womble said those first few hours, when he wasn’t sure of where he’d be working, were difficult. He struggles to describe the feeling of not being able to provide care at his hospital at the time it’s most needed.

“It’s really hard to put it into words,” he said. “It’s the only hospital in that city, and it’s just me and my partner to take care of virtually everyone that comes in with any kind of medical problem. I definitely feel a tie to the community.

“It’s devastating. What is the rest of the city going to do for their hospital care? They essentially will not have a hospital in their city. They’ll have to drive to another city for care.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Obituary: Laura Mirkinson, MD, MSc, FAAP

Laura Mirkinson, MD, MSc, FAAP, pediatric hospitalist and a founder of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) Section on Hospital Medicine Executive Committee, died April 29 of ovarian cancer. She was 60.

Dr. Mirkinson received her medical degree from Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS) in Bethesda, Md., before serving her pediatrics residency at Bethesda Naval Hospital and Walter Reed Army Medical Center. She served as an active-duty medical officer in the U.S. Naval Medical Corps Reserves before retiring as a captain in 2000. She then worked at Children’s Hospital of Washington and the pediatric hospitalist group at Holy Cross Hospital in Silver Spring, Md.

Dr. Mirkinson played a role in the development of pediatric hospital medicine during and after her military service. In 2007, she was elected chief of pediatrics at Blythedale Children’s Hospital in Valhalla, N.Y. She also served as director of education for the AAP’s Section on Hospital Medicine and was its second chairperson, following the section’s co-founder Jack Percelay, MD, FAAP. Through this work, she helped promote the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine newsletter, as well as the Hospital Pediatrics journal.

Dr. Mirkinson’s colleagues and students remember her as a caring, insightful teacher and mentor who offered wise advice on all matters professional and personal. Her devotion to patient care was evident throughout her career. Even in her administrative roles, she would often practice clinical medicine to help fill scheduling gaps or cover other physicians’ vacations.

Laura Mirkinson, MD, MSc, FAAP, pediatric hospitalist and a founder of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) Section on Hospital Medicine Executive Committee, died April 29 of ovarian cancer. She was 60.

Dr. Mirkinson received her medical degree from Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS) in Bethesda, Md., before serving her pediatrics residency at Bethesda Naval Hospital and Walter Reed Army Medical Center. She served as an active-duty medical officer in the U.S. Naval Medical Corps Reserves before retiring as a captain in 2000. She then worked at Children’s Hospital of Washington and the pediatric hospitalist group at Holy Cross Hospital in Silver Spring, Md.

Dr. Mirkinson played a role in the development of pediatric hospital medicine during and after her military service. In 2007, she was elected chief of pediatrics at Blythedale Children’s Hospital in Valhalla, N.Y. She also served as director of education for the AAP’s Section on Hospital Medicine and was its second chairperson, following the section’s co-founder Jack Percelay, MD, FAAP. Through this work, she helped promote the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine newsletter, as well as the Hospital Pediatrics journal.

Dr. Mirkinson’s colleagues and students remember her as a caring, insightful teacher and mentor who offered wise advice on all matters professional and personal. Her devotion to patient care was evident throughout her career. Even in her administrative roles, she would often practice clinical medicine to help fill scheduling gaps or cover other physicians’ vacations.

Laura Mirkinson, MD, MSc, FAAP, pediatric hospitalist and a founder of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) Section on Hospital Medicine Executive Committee, died April 29 of ovarian cancer. She was 60.

Dr. Mirkinson received her medical degree from Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS) in Bethesda, Md., before serving her pediatrics residency at Bethesda Naval Hospital and Walter Reed Army Medical Center. She served as an active-duty medical officer in the U.S. Naval Medical Corps Reserves before retiring as a captain in 2000. She then worked at Children’s Hospital of Washington and the pediatric hospitalist group at Holy Cross Hospital in Silver Spring, Md.

Dr. Mirkinson played a role in the development of pediatric hospital medicine during and after her military service. In 2007, she was elected chief of pediatrics at Blythedale Children’s Hospital in Valhalla, N.Y. She also served as director of education for the AAP’s Section on Hospital Medicine and was its second chairperson, following the section’s co-founder Jack Percelay, MD, FAAP. Through this work, she helped promote the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine newsletter, as well as the Hospital Pediatrics journal.

Dr. Mirkinson’s colleagues and students remember her as a caring, insightful teacher and mentor who offered wise advice on all matters professional and personal. Her devotion to patient care was evident throughout her career. Even in her administrative roles, she would often practice clinical medicine to help fill scheduling gaps or cover other physicians’ vacations.

Movers and Shakers in Hospital Medicine

Chris Brown, MD, MPH, was elected one of Columbus Business First’s members of the Forty Under 40 class of 2013. Dr. Brown is the medical director of hospital medicine at Memorial Hospital of Union County in Marysville, Ohio. The designation recognizes members of the Columbus, Ohio, community who demonstrate superior professional development, community involvement, and other awards and recognitions. Dr. Brown’s colleagues describe him as “a collaborative, attentive, and detailed physician as well as a capable leader.”

Thomas Gallagher, MD, is the University of Washington’s (UW) new director of the program in hospital medicine. This new position in UW’s division of general internal medicine will oversee all of the hospitalist programs at UW Medicine and Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. Dr. Gallagher also is a UW professor of medicine and bioethics and humanities.

Pawan Dhawan, MD, has been appointed medical director of the hospitalist programs at Trident Medical Center in Charleston, S.C., and Summerville Medical Center in Summerville, S.C. Dr. Dhawan comes to Trident Health System from Bay Hospitalists in Newark, Del. Dr. Dhawan served on SHM’s Leadership Committee in 2011.

OB Hospitalist Group (OBHG) in Mauldin, S.C., has announced new medical directors of operations (MDOs) for five of its regions. Nicholas Kulbida, MD, MDO for OBHG’s northeast region, works at Bellevue Women’s Center in Niskayuna, N.Y. Susie Wilson, MD, one of two MDOs for the southeast region, is team leader at Summerville Medical Center in Summerville, S.C. Sue Smith, MD, the other MDO for OBHG’s southeast region, works for Winter Haven Hospital-Regency Medical Center in Winter Haven, Fla. Matthew Conrad, MD, MDO for the Great Lakes region, serves as an OB hospitalist at both Holmes Regional Medical Center in Melbourne, Fla., and Osceola Regional Medical Center in Kissimmee, Fla. Charlie Jaynes, MD, OBHG’s MDO for the south-central region, is an OB hospitalist at North Austin Medical Center in Austin, Texas, and Baylor All Saints Andrews Women’s Hospital in Fort Worth, Texas. Michael White, MD, the West Coast MDO, works as a hospitalist at Hoag Memorial Hospital in Newport Beach, Calif.

Jetinder Singh-Marjara, MD, is the new hospital medicine program director at Golden Valley Memorial Hospital in Clinton, Mo. Dr. Singh-Marjara has worked in Kansas City, Mo., and throughout the Midwest as a hospitalist for more than 10 years since completing his residency in internal medicine at the University of Illinois in Chicago.

Boghara, MD Tien Vo, MD

Fred Guyer, MD, recently was awarded the Northeast Florida Pediatric Society’s Pediatric Hospitalist of the Year award. Dr. Guyer is a hospitalist at Nemours Children’s Clinic in Jacksonville. Dr. Guyer is faculty at the University of Florida College of Medicine.

TeamHealth of Knoxville, Tenn., has announced three new medical directors.

Shelley Lenamond, DO, FHM, is the new facility medical director for TeamHealth’s hospitalist program at Methodist Mansfield Medical Center in Mansfield, Texas.

Haresh Boghara, MD, is the new facility medical director of hospitalist services at Methodist Charlton Medical Center in Dallas.

Tien Vo, MD, is TeamHealth’s new facility medical director of its hospitalist program at El Centro Regional Medical Center in El Centro, Calif.

Michael O'Neal is a freelance writer in New York.

Chris Brown, MD, MPH, was elected one of Columbus Business First’s members of the Forty Under 40 class of 2013. Dr. Brown is the medical director of hospital medicine at Memorial Hospital of Union County in Marysville, Ohio. The designation recognizes members of the Columbus, Ohio, community who demonstrate superior professional development, community involvement, and other awards and recognitions. Dr. Brown’s colleagues describe him as “a collaborative, attentive, and detailed physician as well as a capable leader.”

Thomas Gallagher, MD, is the University of Washington’s (UW) new director of the program in hospital medicine. This new position in UW’s division of general internal medicine will oversee all of the hospitalist programs at UW Medicine and Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. Dr. Gallagher also is a UW professor of medicine and bioethics and humanities.

Pawan Dhawan, MD, has been appointed medical director of the hospitalist programs at Trident Medical Center in Charleston, S.C., and Summerville Medical Center in Summerville, S.C. Dr. Dhawan comes to Trident Health System from Bay Hospitalists in Newark, Del. Dr. Dhawan served on SHM’s Leadership Committee in 2011.

OB Hospitalist Group (OBHG) in Mauldin, S.C., has announced new medical directors of operations (MDOs) for five of its regions. Nicholas Kulbida, MD, MDO for OBHG’s northeast region, works at Bellevue Women’s Center in Niskayuna, N.Y. Susie Wilson, MD, one of two MDOs for the southeast region, is team leader at Summerville Medical Center in Summerville, S.C. Sue Smith, MD, the other MDO for OBHG’s southeast region, works for Winter Haven Hospital-Regency Medical Center in Winter Haven, Fla. Matthew Conrad, MD, MDO for the Great Lakes region, serves as an OB hospitalist at both Holmes Regional Medical Center in Melbourne, Fla., and Osceola Regional Medical Center in Kissimmee, Fla. Charlie Jaynes, MD, OBHG’s MDO for the south-central region, is an OB hospitalist at North Austin Medical Center in Austin, Texas, and Baylor All Saints Andrews Women’s Hospital in Fort Worth, Texas. Michael White, MD, the West Coast MDO, works as a hospitalist at Hoag Memorial Hospital in Newport Beach, Calif.

Jetinder Singh-Marjara, MD, is the new hospital medicine program director at Golden Valley Memorial Hospital in Clinton, Mo. Dr. Singh-Marjara has worked in Kansas City, Mo., and throughout the Midwest as a hospitalist for more than 10 years since completing his residency in internal medicine at the University of Illinois in Chicago.

Boghara, MD Tien Vo, MD

Fred Guyer, MD, recently was awarded the Northeast Florida Pediatric Society’s Pediatric Hospitalist of the Year award. Dr. Guyer is a hospitalist at Nemours Children’s Clinic in Jacksonville. Dr. Guyer is faculty at the University of Florida College of Medicine.

TeamHealth of Knoxville, Tenn., has announced three new medical directors.

Shelley Lenamond, DO, FHM, is the new facility medical director for TeamHealth’s hospitalist program at Methodist Mansfield Medical Center in Mansfield, Texas.

Haresh Boghara, MD, is the new facility medical director of hospitalist services at Methodist Charlton Medical Center in Dallas.

Tien Vo, MD, is TeamHealth’s new facility medical director of its hospitalist program at El Centro Regional Medical Center in El Centro, Calif.

Michael O'Neal is a freelance writer in New York.

Chris Brown, MD, MPH, was elected one of Columbus Business First’s members of the Forty Under 40 class of 2013. Dr. Brown is the medical director of hospital medicine at Memorial Hospital of Union County in Marysville, Ohio. The designation recognizes members of the Columbus, Ohio, community who demonstrate superior professional development, community involvement, and other awards and recognitions. Dr. Brown’s colleagues describe him as “a collaborative, attentive, and detailed physician as well as a capable leader.”

Thomas Gallagher, MD, is the University of Washington’s (UW) new director of the program in hospital medicine. This new position in UW’s division of general internal medicine will oversee all of the hospitalist programs at UW Medicine and Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. Dr. Gallagher also is a UW professor of medicine and bioethics and humanities.

Pawan Dhawan, MD, has been appointed medical director of the hospitalist programs at Trident Medical Center in Charleston, S.C., and Summerville Medical Center in Summerville, S.C. Dr. Dhawan comes to Trident Health System from Bay Hospitalists in Newark, Del. Dr. Dhawan served on SHM’s Leadership Committee in 2011.

OB Hospitalist Group (OBHG) in Mauldin, S.C., has announced new medical directors of operations (MDOs) for five of its regions. Nicholas Kulbida, MD, MDO for OBHG’s northeast region, works at Bellevue Women’s Center in Niskayuna, N.Y. Susie Wilson, MD, one of two MDOs for the southeast region, is team leader at Summerville Medical Center in Summerville, S.C. Sue Smith, MD, the other MDO for OBHG’s southeast region, works for Winter Haven Hospital-Regency Medical Center in Winter Haven, Fla. Matthew Conrad, MD, MDO for the Great Lakes region, serves as an OB hospitalist at both Holmes Regional Medical Center in Melbourne, Fla., and Osceola Regional Medical Center in Kissimmee, Fla. Charlie Jaynes, MD, OBHG’s MDO for the south-central region, is an OB hospitalist at North Austin Medical Center in Austin, Texas, and Baylor All Saints Andrews Women’s Hospital in Fort Worth, Texas. Michael White, MD, the West Coast MDO, works as a hospitalist at Hoag Memorial Hospital in Newport Beach, Calif.

Jetinder Singh-Marjara, MD, is the new hospital medicine program director at Golden Valley Memorial Hospital in Clinton, Mo. Dr. Singh-Marjara has worked in Kansas City, Mo., and throughout the Midwest as a hospitalist for more than 10 years since completing his residency in internal medicine at the University of Illinois in Chicago.

Boghara, MD Tien Vo, MD

Fred Guyer, MD, recently was awarded the Northeast Florida Pediatric Society’s Pediatric Hospitalist of the Year award. Dr. Guyer is a hospitalist at Nemours Children’s Clinic in Jacksonville. Dr. Guyer is faculty at the University of Florida College of Medicine.

TeamHealth of Knoxville, Tenn., has announced three new medical directors.

Shelley Lenamond, DO, FHM, is the new facility medical director for TeamHealth’s hospitalist program at Methodist Mansfield Medical Center in Mansfield, Texas.

Haresh Boghara, MD, is the new facility medical director of hospitalist services at Methodist Charlton Medical Center in Dallas.

Tien Vo, MD, is TeamHealth’s new facility medical director of its hospitalist program at El Centro Regional Medical Center in El Centro, Calif.

Michael O'Neal is a freelance writer in New York.

Can Medicare Pay for Value?

Can quality measurement and comparisons serve as the backbone for a major shift in the Medicare payment system to reward value instead of volume? That is the question being explored over the next few years as the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and, by extension, the physician value-based payment modifier (VBPM) come fully into effect for all physicians.

There seems to be a consensus in the policy community that the fee-for-service model of payment is past its prime and needs to be replaced with a more dynamic and responsive payment system. Medicare hopes that PQRS and the VBPM will enable adjustments to physician payments to reward high-quality and low-cost care. Although these programs currently are add-ons to the fee-for-service system, they likely will serve as stepping stones to more radical departures from the existing payment system.

SHM advocates refinements to policies for PQRS and similar programs to make them more meaningful and productive for both hospitalists and the broader health-care system. Each year, SHM submits comments on the Physician Fee Schedule Rule, which creates and updates the regulatory framework for PQRS and the VBPM. SHM also provided feedback on Quality and Resource Use Reports (QRURs), the report cards for the modifier that were being tested over the past year.

From a practical standpoint, SHM engages with measure development and endorsement processes to ensure there are reportable quality measures in PQRS that fit hospitalist practice. In addition, SHM is helping to increase accessibility to PQRS reporting by offering members reduced fare access to registry reporting through the PQRI Wizard.

The comments range from the technical aspects of individual quality measures in PQRS to how hospitalists appear to be performing in these programs. SHM firmly believes that the unique positioning of hospitalists within the health-care system presents challenges for their identification and evaluation in Medicare programs. In some sense, hospitalists exist on the line between the inpatient and outpatient worlds, a location not adequately captured in pay-for-performance programs.

It’s imperative that pay-for-performance programs have reasonable and actionable outcomes for providers. If quality measures are not clinically meaningful and do not capture a plurality of the care provided by an individual hospitalist, it is difficult for the program to meet its stated aims. If payment is to be influenced by performance on quality measures, it follows that those measures should be relevant to the care provided.

There is a long way to go toward creating quality measurement and evaluation programs that are relevant and actionable for clinical quality improvement (QI). By becoming involved in SHM’s policy efforts, members are able to share their experiences and impressions of programs with SHM and lawmakers. This partnership helps create more responsive and intuitive programs, which in turn leads to greater participation and, hopefully, improved patient outcomes. As these programs continue to evolve and more health professionals are required to participate, SHM will be looking to its membership for their perspectives.

Join the grassroots network to stay involved and up to date by registering at www.hospitalmedicine.org/grassroots.

Joshua Lapps is SHM’s government relations specialist.

Can quality measurement and comparisons serve as the backbone for a major shift in the Medicare payment system to reward value instead of volume? That is the question being explored over the next few years as the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and, by extension, the physician value-based payment modifier (VBPM) come fully into effect for all physicians.

There seems to be a consensus in the policy community that the fee-for-service model of payment is past its prime and needs to be replaced with a more dynamic and responsive payment system. Medicare hopes that PQRS and the VBPM will enable adjustments to physician payments to reward high-quality and low-cost care. Although these programs currently are add-ons to the fee-for-service system, they likely will serve as stepping stones to more radical departures from the existing payment system.

SHM advocates refinements to policies for PQRS and similar programs to make them more meaningful and productive for both hospitalists and the broader health-care system. Each year, SHM submits comments on the Physician Fee Schedule Rule, which creates and updates the regulatory framework for PQRS and the VBPM. SHM also provided feedback on Quality and Resource Use Reports (QRURs), the report cards for the modifier that were being tested over the past year.

From a practical standpoint, SHM engages with measure development and endorsement processes to ensure there are reportable quality measures in PQRS that fit hospitalist practice. In addition, SHM is helping to increase accessibility to PQRS reporting by offering members reduced fare access to registry reporting through the PQRI Wizard.

The comments range from the technical aspects of individual quality measures in PQRS to how hospitalists appear to be performing in these programs. SHM firmly believes that the unique positioning of hospitalists within the health-care system presents challenges for their identification and evaluation in Medicare programs. In some sense, hospitalists exist on the line between the inpatient and outpatient worlds, a location not adequately captured in pay-for-performance programs.

It’s imperative that pay-for-performance programs have reasonable and actionable outcomes for providers. If quality measures are not clinically meaningful and do not capture a plurality of the care provided by an individual hospitalist, it is difficult for the program to meet its stated aims. If payment is to be influenced by performance on quality measures, it follows that those measures should be relevant to the care provided.

There is a long way to go toward creating quality measurement and evaluation programs that are relevant and actionable for clinical quality improvement (QI). By becoming involved in SHM’s policy efforts, members are able to share their experiences and impressions of programs with SHM and lawmakers. This partnership helps create more responsive and intuitive programs, which in turn leads to greater participation and, hopefully, improved patient outcomes. As these programs continue to evolve and more health professionals are required to participate, SHM will be looking to its membership for their perspectives.

Join the grassroots network to stay involved and up to date by registering at www.hospitalmedicine.org/grassroots.

Joshua Lapps is SHM’s government relations specialist.

Can quality measurement and comparisons serve as the backbone for a major shift in the Medicare payment system to reward value instead of volume? That is the question being explored over the next few years as the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and, by extension, the physician value-based payment modifier (VBPM) come fully into effect for all physicians.

There seems to be a consensus in the policy community that the fee-for-service model of payment is past its prime and needs to be replaced with a more dynamic and responsive payment system. Medicare hopes that PQRS and the VBPM will enable adjustments to physician payments to reward high-quality and low-cost care. Although these programs currently are add-ons to the fee-for-service system, they likely will serve as stepping stones to more radical departures from the existing payment system.

SHM advocates refinements to policies for PQRS and similar programs to make them more meaningful and productive for both hospitalists and the broader health-care system. Each year, SHM submits comments on the Physician Fee Schedule Rule, which creates and updates the regulatory framework for PQRS and the VBPM. SHM also provided feedback on Quality and Resource Use Reports (QRURs), the report cards for the modifier that were being tested over the past year.

From a practical standpoint, SHM engages with measure development and endorsement processes to ensure there are reportable quality measures in PQRS that fit hospitalist practice. In addition, SHM is helping to increase accessibility to PQRS reporting by offering members reduced fare access to registry reporting through the PQRI Wizard.

The comments range from the technical aspects of individual quality measures in PQRS to how hospitalists appear to be performing in these programs. SHM firmly believes that the unique positioning of hospitalists within the health-care system presents challenges for their identification and evaluation in Medicare programs. In some sense, hospitalists exist on the line between the inpatient and outpatient worlds, a location not adequately captured in pay-for-performance programs.

It’s imperative that pay-for-performance programs have reasonable and actionable outcomes for providers. If quality measures are not clinically meaningful and do not capture a plurality of the care provided by an individual hospitalist, it is difficult for the program to meet its stated aims. If payment is to be influenced by performance on quality measures, it follows that those measures should be relevant to the care provided.

There is a long way to go toward creating quality measurement and evaluation programs that are relevant and actionable for clinical quality improvement (QI). By becoming involved in SHM’s policy efforts, members are able to share their experiences and impressions of programs with SHM and lawmakers. This partnership helps create more responsive and intuitive programs, which in turn leads to greater participation and, hopefully, improved patient outcomes. As these programs continue to evolve and more health professionals are required to participate, SHM will be looking to its membership for their perspectives.

Join the grassroots network to stay involved and up to date by registering at www.hospitalmedicine.org/grassroots.

Joshua Lapps is SHM’s government relations specialist.

Three Easy Ways to Get Ahead in Hospital Medicine

Getting involved—and getting ahead—in hospital medicine has never been easier, with just some planning and preparation. Here are three ways to move your hospital—and your career—forward this month.

1. Add “award-winning” to your CV: SHM’s Awards of Excellence deadline is Sept. 16.

Although 2013’s award-winners are still fresh in hospitalists’ minds, now is the time to put together award applications for the 2014 Awards of Excellence.

Each year, SHM presents six different awards that recognize individuals and one award to a team that is transforming health care and revolutionizing patient care for hospitalized patients:

- Excellence in Research Award;

- Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians;

- Award for Excellence in Teaching;

- Award for Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine;

- Award for Clinical Excellence; and

- Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement.

Last year, SHM received award nominations from a diverse group of hospitalists and looks forward to receiving even more this year. Each winner receives an all-expenses-paid trip to HM14 in Las Vegas, including complimentary meeting registration.

The deadline for applications for SHM’s five individual awards is Sept. 16. The deadline for the Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement is Oct. 15. All SHM members are eligible, and nominees can be self-nominated.

For more information, visit www.hospital medicine.org/awards.

2. Bring the experts in reducing readmissions to your hospital: Apply now for Project BOOST.

There is still time to apply for SHM’s Project BOOST, which helps hospitals design discharge programs to reduce readmissions. SHM will accept applications for Project BOOST until the end of August.

Project BOOST is based on SHM’s award-winning mentored implementation model that brings individualized attention from national experts in reducing readmissions to hospitals across the country. Each Project BOOST site receives:

- A comprehensive intervention developed by a panel of nationally recognized experts based on the best available evidence.

- A comprehensive implementation guide that provides step-by-step instructions and project-management tools, such as the teachback training curriculum, to help interdisciplinary teams redesign workflow and plan, implement, and evaluate the intervention.

- Longitudinal technical assistance providing face-to-face training and a year of expert mentoring and coaching to implement BOOST interventions that build a culture that supports safe and complete transitions. The mentoring program provides a training DVD and curriculum for nurses and case managers on using the teachback process, as well as webinars that target the educational needs of other team members, including administrators, data analysts, physicians, nurses, and others.

- Collaboration that allows sites to communicate with and learn from each other via the BOOST community site and quarterly all-site teleconferences and webinars.

- The BOOST data center, an online resource that allows sites to store and benchmark data against control units and other sites and generates reports.

For more information, visit www.hospital medicine.org/boost.

3. Start Choosing Wisely today.

In 2014, as part of a grant from the ABIM Foundation, SHM will begin its first Choosing Wisely case-study competition to highlight hospitalists’ best practices within the popular campaign.

But in order to have a successful case study next year, some preparation is in order now. Developing goals, gathering a team, and, perhaps most important, developing benchmarking data on a project motivated by Choosing Wisely will all be important parts of a compelling case study.

To start brainstorming your project to implement Choosing Wisely recommendations at your hospital, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Getting involved—and getting ahead—in hospital medicine has never been easier, with just some planning and preparation. Here are three ways to move your hospital—and your career—forward this month.

1. Add “award-winning” to your CV: SHM’s Awards of Excellence deadline is Sept. 16.

Although 2013’s award-winners are still fresh in hospitalists’ minds, now is the time to put together award applications for the 2014 Awards of Excellence.

Each year, SHM presents six different awards that recognize individuals and one award to a team that is transforming health care and revolutionizing patient care for hospitalized patients:

- Excellence in Research Award;

- Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians;

- Award for Excellence in Teaching;

- Award for Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine;

- Award for Clinical Excellence; and

- Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement.

Last year, SHM received award nominations from a diverse group of hospitalists and looks forward to receiving even more this year. Each winner receives an all-expenses-paid trip to HM14 in Las Vegas, including complimentary meeting registration.

The deadline for applications for SHM’s five individual awards is Sept. 16. The deadline for the Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement is Oct. 15. All SHM members are eligible, and nominees can be self-nominated.

For more information, visit www.hospital medicine.org/awards.

2. Bring the experts in reducing readmissions to your hospital: Apply now for Project BOOST.

There is still time to apply for SHM’s Project BOOST, which helps hospitals design discharge programs to reduce readmissions. SHM will accept applications for Project BOOST until the end of August.

Project BOOST is based on SHM’s award-winning mentored implementation model that brings individualized attention from national experts in reducing readmissions to hospitals across the country. Each Project BOOST site receives:

- A comprehensive intervention developed by a panel of nationally recognized experts based on the best available evidence.

- A comprehensive implementation guide that provides step-by-step instructions and project-management tools, such as the teachback training curriculum, to help interdisciplinary teams redesign workflow and plan, implement, and evaluate the intervention.

- Longitudinal technical assistance providing face-to-face training and a year of expert mentoring and coaching to implement BOOST interventions that build a culture that supports safe and complete transitions. The mentoring program provides a training DVD and curriculum for nurses and case managers on using the teachback process, as well as webinars that target the educational needs of other team members, including administrators, data analysts, physicians, nurses, and others.

- Collaboration that allows sites to communicate with and learn from each other via the BOOST community site and quarterly all-site teleconferences and webinars.

- The BOOST data center, an online resource that allows sites to store and benchmark data against control units and other sites and generates reports.

For more information, visit www.hospital medicine.org/boost.

3. Start Choosing Wisely today.

In 2014, as part of a grant from the ABIM Foundation, SHM will begin its first Choosing Wisely case-study competition to highlight hospitalists’ best practices within the popular campaign.

But in order to have a successful case study next year, some preparation is in order now. Developing goals, gathering a team, and, perhaps most important, developing benchmarking data on a project motivated by Choosing Wisely will all be important parts of a compelling case study.

To start brainstorming your project to implement Choosing Wisely recommendations at your hospital, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Getting involved—and getting ahead—in hospital medicine has never been easier, with just some planning and preparation. Here are three ways to move your hospital—and your career—forward this month.

1. Add “award-winning” to your CV: SHM’s Awards of Excellence deadline is Sept. 16.

Although 2013’s award-winners are still fresh in hospitalists’ minds, now is the time to put together award applications for the 2014 Awards of Excellence.

Each year, SHM presents six different awards that recognize individuals and one award to a team that is transforming health care and revolutionizing patient care for hospitalized patients:

- Excellence in Research Award;

- Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians;

- Award for Excellence in Teaching;

- Award for Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine;

- Award for Clinical Excellence; and

- Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement.

Last year, SHM received award nominations from a diverse group of hospitalists and looks forward to receiving even more this year. Each winner receives an all-expenses-paid trip to HM14 in Las Vegas, including complimentary meeting registration.

The deadline for applications for SHM’s five individual awards is Sept. 16. The deadline for the Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement is Oct. 15. All SHM members are eligible, and nominees can be self-nominated.

For more information, visit www.hospital medicine.org/awards.

2. Bring the experts in reducing readmissions to your hospital: Apply now for Project BOOST.

There is still time to apply for SHM’s Project BOOST, which helps hospitals design discharge programs to reduce readmissions. SHM will accept applications for Project BOOST until the end of August.

Project BOOST is based on SHM’s award-winning mentored implementation model that brings individualized attention from national experts in reducing readmissions to hospitals across the country. Each Project BOOST site receives:

- A comprehensive intervention developed by a panel of nationally recognized experts based on the best available evidence.

- A comprehensive implementation guide that provides step-by-step instructions and project-management tools, such as the teachback training curriculum, to help interdisciplinary teams redesign workflow and plan, implement, and evaluate the intervention.

- Longitudinal technical assistance providing face-to-face training and a year of expert mentoring and coaching to implement BOOST interventions that build a culture that supports safe and complete transitions. The mentoring program provides a training DVD and curriculum for nurses and case managers on using the teachback process, as well as webinars that target the educational needs of other team members, including administrators, data analysts, physicians, nurses, and others.

- Collaboration that allows sites to communicate with and learn from each other via the BOOST community site and quarterly all-site teleconferences and webinars.

- The BOOST data center, an online resource that allows sites to store and benchmark data against control units and other sites and generates reports.

For more information, visit www.hospital medicine.org/boost.

3. Start Choosing Wisely today.

In 2014, as part of a grant from the ABIM Foundation, SHM will begin its first Choosing Wisely case-study competition to highlight hospitalists’ best practices within the popular campaign.

But in order to have a successful case study next year, some preparation is in order now. Developing goals, gathering a team, and, perhaps most important, developing benchmarking data on a project motivated by Choosing Wisely will all be important parts of a compelling case study.

To start brainstorming your project to implement Choosing Wisely recommendations at your hospital, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Hospitalist Advocate Finds Niche in Hospital Medicine

Bryan Weiss, MBA, likes to say he’s “passionate” about HM. The twist? He isn’t even a practicing physician. Nevertheless, he’s been involved in medicine for 25 years, having worked with hospitals, health plans, and multispecialty groups before joining IPC: The Hospitalist Company in 2003. During his first few years working in the field, he realized the specialty had a bright future.

“I enjoy working with the hospitalists and assisting them to become the cornerstone of the hospitals they work in,” says Weiss, managing director of the consulting services practice at Irving, Texas-based MedSynergies. “Creating the open communications among the hospital administration, emergency room, nursing, case management, consultants, and PCPs—as well as moving the specialty forward with actionable, balanced scorecards—is the most satisfying component.”

Weiss previously was president of the hospitalist division at Hospital Physician Partners of Hollywood, Fla., and COO of inpatient services at Dallas-based EmCare. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in business administration from California State University and earned his master’s degree from California Lutheran University.

He is one of nine new Team Hospitalist members, The Hospitalist’s volunteer group of editorial advisors. He sees challenges ahead for hospitalists, administrators, and the health-care system, but he also has faith the specialty will be up to the task.

“I think the incredibly rapid growth of the specialty is huge,” he says. “The acceptance of the specialty has gone from needing to explain what a hospitalist is to insurance companies and hospitals and other physicians to [knowing] the value of a hospitalist program and how disadvantaged a hospital is without a program.”

Question: As a nonphysician, explain your role in the health-care system and HM.

Answer: I want to make sure the hospitalist team truly operates as a team and not a bunch of physicians who happen to work in the same hospital. The bottom line is it is about the patient experience and how hospitalists will be pivotal as health care moves to more risk-based and population health.

Q: What is your biggest professional challenge?

A: Ensuring the alignment of the goals of the hospital and the hospitalists are translated to measurable outcomes is probably the biggest challenge in the current state of health care.

Q: What is your biggest professional reward?

A: The number of hospital administrators who value my contribution and commitment to making the hospitalist program at their facilities the best they can become.

Q: When you aren’t working, what is important to you?

A: My family time and the balance of work and life have become the most important as I have matured professionally.

Q: What’s next professionally?

A: I am doing my ideal professional position.

Q: If you had to do it all over again, what career would you be doing right now?

A: If I wasn’t an executive in healthcare, I would have probably been a lawyer since I contemplated law school over my MBA.

Q: What’s the best book you’ve read recently?

A: New Orleans Saints quarterback Drew Brees’ book, “Coming Back Stronger.” As an avid sports fan, I appreciate what this athlete experienced personally and professionally, and still was able to pick himself back up from situations that many of us would have struggled to overcome. He is one of the biggest class acts in sports and the book just solidified that opinion. We can apply what he says to our own lives and make ourselves better in what we do as leaders.

Q: How many Apple products (phones, iPods, tablets, iTunes, etc.) do you interface with in a given week?

A: I am constantly on my iPad and use iTunes regularly during my weekly travels. My cellphone is an Android, so only two Apple products, but I use Apple countless times a week.

Richard Quinn is a freelance author in New Jersey.

Bryan Weiss, MBA, likes to say he’s “passionate” about HM. The twist? He isn’t even a practicing physician. Nevertheless, he’s been involved in medicine for 25 years, having worked with hospitals, health plans, and multispecialty groups before joining IPC: The Hospitalist Company in 2003. During his first few years working in the field, he realized the specialty had a bright future.

“I enjoy working with the hospitalists and assisting them to become the cornerstone of the hospitals they work in,” says Weiss, managing director of the consulting services practice at Irving, Texas-based MedSynergies. “Creating the open communications among the hospital administration, emergency room, nursing, case management, consultants, and PCPs—as well as moving the specialty forward with actionable, balanced scorecards—is the most satisfying component.”

Weiss previously was president of the hospitalist division at Hospital Physician Partners of Hollywood, Fla., and COO of inpatient services at Dallas-based EmCare. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in business administration from California State University and earned his master’s degree from California Lutheran University.

He is one of nine new Team Hospitalist members, The Hospitalist’s volunteer group of editorial advisors. He sees challenges ahead for hospitalists, administrators, and the health-care system, but he also has faith the specialty will be up to the task.

“I think the incredibly rapid growth of the specialty is huge,” he says. “The acceptance of the specialty has gone from needing to explain what a hospitalist is to insurance companies and hospitals and other physicians to [knowing] the value of a hospitalist program and how disadvantaged a hospital is without a program.”

Question: As a nonphysician, explain your role in the health-care system and HM.

Answer: I want to make sure the hospitalist team truly operates as a team and not a bunch of physicians who happen to work in the same hospital. The bottom line is it is about the patient experience and how hospitalists will be pivotal as health care moves to more risk-based and population health.

Q: What is your biggest professional challenge?

A: Ensuring the alignment of the goals of the hospital and the hospitalists are translated to measurable outcomes is probably the biggest challenge in the current state of health care.

Q: What is your biggest professional reward?

A: The number of hospital administrators who value my contribution and commitment to making the hospitalist program at their facilities the best they can become.

Q: When you aren’t working, what is important to you?

A: My family time and the balance of work and life have become the most important as I have matured professionally.

Q: What’s next professionally?

A: I am doing my ideal professional position.

Q: If you had to do it all over again, what career would you be doing right now?

A: If I wasn’t an executive in healthcare, I would have probably been a lawyer since I contemplated law school over my MBA.

Q: What’s the best book you’ve read recently?

A: New Orleans Saints quarterback Drew Brees’ book, “Coming Back Stronger.” As an avid sports fan, I appreciate what this athlete experienced personally and professionally, and still was able to pick himself back up from situations that many of us would have struggled to overcome. He is one of the biggest class acts in sports and the book just solidified that opinion. We can apply what he says to our own lives and make ourselves better in what we do as leaders.

Q: How many Apple products (phones, iPods, tablets, iTunes, etc.) do you interface with in a given week?

A: I am constantly on my iPad and use iTunes regularly during my weekly travels. My cellphone is an Android, so only two Apple products, but I use Apple countless times a week.

Richard Quinn is a freelance author in New Jersey.

Bryan Weiss, MBA, likes to say he’s “passionate” about HM. The twist? He isn’t even a practicing physician. Nevertheless, he’s been involved in medicine for 25 years, having worked with hospitals, health plans, and multispecialty groups before joining IPC: The Hospitalist Company in 2003. During his first few years working in the field, he realized the specialty had a bright future.

“I enjoy working with the hospitalists and assisting them to become the cornerstone of the hospitals they work in,” says Weiss, managing director of the consulting services practice at Irving, Texas-based MedSynergies. “Creating the open communications among the hospital administration, emergency room, nursing, case management, consultants, and PCPs—as well as moving the specialty forward with actionable, balanced scorecards—is the most satisfying component.”

Weiss previously was president of the hospitalist division at Hospital Physician Partners of Hollywood, Fla., and COO of inpatient services at Dallas-based EmCare. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in business administration from California State University and earned his master’s degree from California Lutheran University.

He is one of nine new Team Hospitalist members, The Hospitalist’s volunteer group of editorial advisors. He sees challenges ahead for hospitalists, administrators, and the health-care system, but he also has faith the specialty will be up to the task.

“I think the incredibly rapid growth of the specialty is huge,” he says. “The acceptance of the specialty has gone from needing to explain what a hospitalist is to insurance companies and hospitals and other physicians to [knowing] the value of a hospitalist program and how disadvantaged a hospital is without a program.”

Question: As a nonphysician, explain your role in the health-care system and HM.

Answer: I want to make sure the hospitalist team truly operates as a team and not a bunch of physicians who happen to work in the same hospital. The bottom line is it is about the patient experience and how hospitalists will be pivotal as health care moves to more risk-based and population health.

Q: What is your biggest professional challenge?

A: Ensuring the alignment of the goals of the hospital and the hospitalists are translated to measurable outcomes is probably the biggest challenge in the current state of health care.

Q: What is your biggest professional reward?

A: The number of hospital administrators who value my contribution and commitment to making the hospitalist program at their facilities the best they can become.

Q: When you aren’t working, what is important to you?

A: My family time and the balance of work and life have become the most important as I have matured professionally.

Q: What’s next professionally?

A: I am doing my ideal professional position.

Q: If you had to do it all over again, what career would you be doing right now?

A: If I wasn’t an executive in healthcare, I would have probably been a lawyer since I contemplated law school over my MBA.

Q: What’s the best book you’ve read recently?

A: New Orleans Saints quarterback Drew Brees’ book, “Coming Back Stronger.” As an avid sports fan, I appreciate what this athlete experienced personally and professionally, and still was able to pick himself back up from situations that many of us would have struggled to overcome. He is one of the biggest class acts in sports and the book just solidified that opinion. We can apply what he says to our own lives and make ourselves better in what we do as leaders.

Q: How many Apple products (phones, iPods, tablets, iTunes, etc.) do you interface with in a given week?

A: I am constantly on my iPad and use iTunes regularly during my weekly travels. My cellphone is an Android, so only two Apple products, but I use Apple countless times a week.

Richard Quinn is a freelance author in New Jersey.

Pediatric Hospital Medicine Aims to Define Itself

Legend has it that Alexander the Great once was confronted with an intricate knot tying up a sacred ox cart in the palace of the Phrygians, whom he was trying to conquer. When his attempts to untie the knot proved unsuccessful, he drew his sword and sliced it in half, thus providing a rapid if inelegant solution.

Pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) now finds itself facing a similar dilemma in its attempts to define its “kingdom.” The question: Who will become citizens of this kingdom—and who will be left outside the gates? And will this intricate knot be unraveled or simply cut?

In some ways, the mere posing of this question signifies the success PHM has forged for itself over the past decade. At its core, the question of how to define the identity, and thus the training, of a pediatric hospitalist is rooted in noble ideals: excellence in the management of hospitalized children, robust training in quality improvement, patient safety, and cost-effective care.1 Yet this question also stirs up more base feelings frequently articulated in many a physician lounge: territoriality, inadequacy, feeling excluded.

Nevertheless, the question must be answered.

In many ways, the situation in which PHM finds itself mirrors the dilemma facing pediatrics itself in its infancy. As Borden Veeder, the first president of the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), wrote in the 1930s, “There were no legal or medical requirements relating to the training and education of specialists—all a man licensed to practice medicine had to do was to announce himself as a surgeon, internist, pediatrician, etc., as he preferred.”2 In 1933, the ABP was incorporated, with representatives from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Medical Association (AMA) section on pediatrics, and the American Pediatric Society.

Facing a similar state of confusion, hospitalist leaders of the PHM community in 2010 formed the Strategic Planning Committee (STP) to evaluate training and certification options for PHM as a distinct discipline.3 Co-chairs of the STP Committee were chosen by consensus from a group composed of one representative each from the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM), the Academic Pediatric Association (APA), and SHM. The STP identified various training and/or certification options that could define PHM as a subspecialty. A survey with these options was distributed to the PHM community via the listservs of the APA, the AAP SOHM, and the AAP. The results:3

- 33% of respondents preferred Recognition of Focused Practice through the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC);

- 30% preferred a two-year fellowship; and

- 17% suggested an HM track within pediatric residency.

Yet at the PHM Leaders Conference in Chapel Hill, N.C., in April, “there was overwhelming consensus that an MOC program could not provide the rigor to insure [sic] that all pediatric hospitalists would meet a standard.”4 Further, “there was overwhelming consensus that a standardized training program resulting in certification was the best option to assure adequate training in the PHM Core Competencies and provide the public with a meaningful definition of a pediatric hospitalist” and “that the duration of such training should be two years.” Why, one might ask, would those present feel so strongly that the MOC model would be inadequate?

Many concerns regarding MOC were voiced, including whether MOC addresses a knowledge gap after residency (which it does to some extent through ongoing recertification requirements), whether it ensures public trust (but it had “positive potential”), and whether it addressed core competencies (to which the leadership present answered “yes, if rigorous”).4

The perception that the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) MOC was “not a successful model so far in adult hospital medicine” seemed to weigh heavily on the minds of those in attendance. This perception may have arisen from data showing a somewhat low number of adult hospitalists (363 completed, 527 in process) having successfully completed the FPHM MOC to date. Of note, the possibility of a FPHM MOC for PHM was considered a “non-starter” by the ABP representatives, who in turn attributed this determination to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS).5

There are, of course, many reasons for the low turnout for adult FPHM MOC. Candidates must have been previously certified in internal medicine of family medicine, and thus entry into the FPHM MOC would only arise at recertification or if one decided to seek FPHM certification “early”—that is, prior to the need for recertification. Being not only a Procrastination Club president but also a client, I was not among the 67 virtuous hospitalists who were among the first class of FPHM diplomates in 2011.6 The FPHM MOC also initially was more rigorous than the traditional IM recertification, in that it required completion of a practice-improvement module (PIM) every three years versus every 10 years (in 2014, both the traditional IM and FPHM MOC programs will require PIM completion every 5 years). Without a clearly mandated requirement from most HM groups, at the inception of the FPHM MOC one would be entering a more rigorous recertification process without a clear benefit.

This lack of a requirement from adult HM groups for completion or entry into the FPHM MOC, in turn, arises from a straightforward issue: workforce. Requiring all hospitalists in your HM group to have completed or entered FPHM MOC is a bar most directors and chiefs are not prepared to raise given its potential to shrink their applicant pool. With only 32 to 35 graduates of pediatric HM fellowship programs yearly, workforce issues should clearly be of concern to the PHM community given the current estimates that pediatric hospitalists number anywhere from 1,500 to 3,000.6,7

Is the adult FPHM MOC process perfect? Nothing created by so many committees and professional societies could ever be, but as a first iteration, it certainly created a relatively sturdy straw man. Could the PHM community create a FPHM MOC upon this model that was refined and tailored to their needs? Creating and requiring completion of a robust PHM-specific curriculum via required self-evaluation modules, requiring not only patient encounter thresholds but also evidence of quality care, and developing PIMs specific to PHM would all go a long way to making a FPHM MOC an acceptable alternative for pediatric hospitalist “designation.”

In any case, the gauntlet seems to have been thrown down already in Chapel Hill in favor of a two-year fellowship leading to certification. I admire those present for advocating a training and certification that provides the least compromise in defining the path of future pediatric hospitalists. But I suspect that the answer to the problem of PHM’s future may not be so simple as a single sharp-edged solution and might lie in a more complex array of options for future pediatric hospitalists.

Dr. Chang is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. He is associate clinical professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) School of Medicine, and a hospitalist at both UCSD Medical Center and Rady Children’s Hospital. Send comments and questions to [email protected].

References

- Maniscalco J, Fisher ES. Pediatric hospital medicine and education: why we can’t stand still. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:412-413.

- Brownlee RC. The American Board of Pediatrics: its origin and early history. Pediatrics. 1994;94:732-735.

- Maloney CG, Mendez SS, Quinonez RA, et al. The Strategic Planning Committee report: the first step in a journey to recognize pediatric hospital medicine as a distinct discipline. Hospital Pediatrics. 2012;2:187-190.

- Strategic Planning Committee. Strategic planning for the future of pediatric hospital medicine. Strategic Planning Committee website. Available at: http://stpcommittee.blogspot.com/2013/04/phm-leadership-conference-april-4-5.htmlfiles/97/phm-leadership-conference-april-4-5.html. Accessed July 4, 2013.

- Fisher ES. (2013) Email sent to Chang WW. 25 June.

- Carris J. Defining moment: focused practice in HM. The Hospitalist website. Available at: http://www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/1018793/Defining_Moment_Focused_Practice_in_HM.html. Accessed June 15, 2013.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. PHM fellowship info. American Academy of Pediatrics website. Available at: http://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/Committees-Councils-Sections/Section-on-Hospital-Medicine.html. Accessed June 15, 2013.

- Rauch DA, Lye PS, Carlson D, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: a strategic planning roundtable to chart the future. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:329-334.

Legend has it that Alexander the Great once was confronted with an intricate knot tying up a sacred ox cart in the palace of the Phrygians, whom he was trying to conquer. When his attempts to untie the knot proved unsuccessful, he drew his sword and sliced it in half, thus providing a rapid if inelegant solution.

Pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) now finds itself facing a similar dilemma in its attempts to define its “kingdom.” The question: Who will become citizens of this kingdom—and who will be left outside the gates? And will this intricate knot be unraveled or simply cut?

In some ways, the mere posing of this question signifies the success PHM has forged for itself over the past decade. At its core, the question of how to define the identity, and thus the training, of a pediatric hospitalist is rooted in noble ideals: excellence in the management of hospitalized children, robust training in quality improvement, patient safety, and cost-effective care.1 Yet this question also stirs up more base feelings frequently articulated in many a physician lounge: territoriality, inadequacy, feeling excluded.

Nevertheless, the question must be answered.

In many ways, the situation in which PHM finds itself mirrors the dilemma facing pediatrics itself in its infancy. As Borden Veeder, the first president of the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), wrote in the 1930s, “There were no legal or medical requirements relating to the training and education of specialists—all a man licensed to practice medicine had to do was to announce himself as a surgeon, internist, pediatrician, etc., as he preferred.”2 In 1933, the ABP was incorporated, with representatives from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Medical Association (AMA) section on pediatrics, and the American Pediatric Society.

Facing a similar state of confusion, hospitalist leaders of the PHM community in 2010 formed the Strategic Planning Committee (STP) to evaluate training and certification options for PHM as a distinct discipline.3 Co-chairs of the STP Committee were chosen by consensus from a group composed of one representative each from the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM), the Academic Pediatric Association (APA), and SHM. The STP identified various training and/or certification options that could define PHM as a subspecialty. A survey with these options was distributed to the PHM community via the listservs of the APA, the AAP SOHM, and the AAP. The results:3

- 33% of respondents preferred Recognition of Focused Practice through the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC);