User login

Clinical Conundrum

A 62‐year‐old man with psoriasis for more than 30 years presented to the emergency department with a scaly, pruritic rash involving his face, trunk, and extremities that he had had for the past 10 days. The rash was spreading and not responding to application of clobetasol ointment, which had helped his psoriasis in the past. He also reported mild pharyngitis, headache, and myalgias.

A patient with a chronic skin condition presenting with a new rash means the clinician must consider whether it is an alternative manifestation of the chronic disorder or a new illness. Psoriasis takes many forms including guttate psoriasis, which presents with small, droplike plaques and frequently follows respiratory infections (particularly those caused by Streptococcus). Well‐controlled psoriasis rarely transforms after 3 decades, so I would consider other conditions. The tempo of illness makes certain life‐threatening syndromes, including Stevens‐Johnson, toxic shock, and purpura fulminans, unlikely. An allergic reaction, atopic dermatitis, or medication reaction is possible. Infections, either systemic (eg, syphilis) or dermatologic (eg, scabies), should be considered. Photosensitivity could involve the sun‐exposed areas, such as the extremities and face. Seborrheic dermatitis can cause scaling lesions of the face and trunk but not the extremities. Vasculitis merits consideration, but dependent regions are typically affected more than the head. Mycosis fungoides or a paraneoplastic phenomenon could cause a diffuse rash in this age group.

The patient had diabetes mellitus, hypertension, diverticulosis, and depression. Three months earlier he had undergone surgical drainage of a perirectal abscess. His usual medications were lovastatin, paroxetine, insulin, hydrochlorothiazide, and lisinopril. Three weeks previously he had completed a 10‐day course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for an upper respiratory infection. Otherwise, he was taking no new medications. He was allergic to penicillin. He denied substance abuse, recent travel, or risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. He worked as an automobile painter, lived with his wife, and had a pet dog.

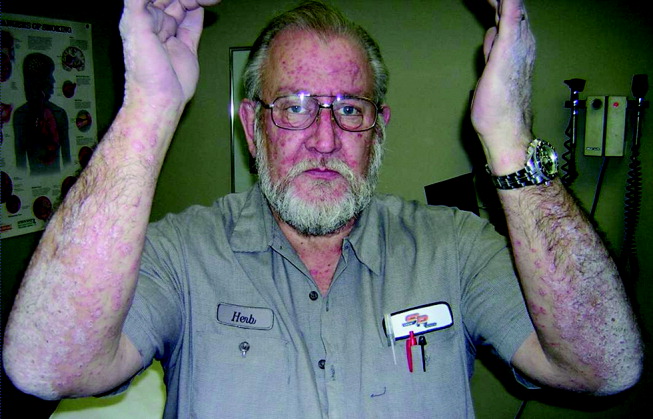

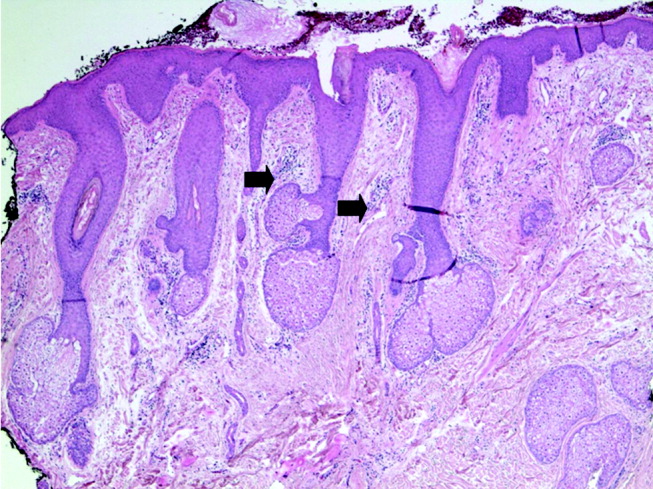

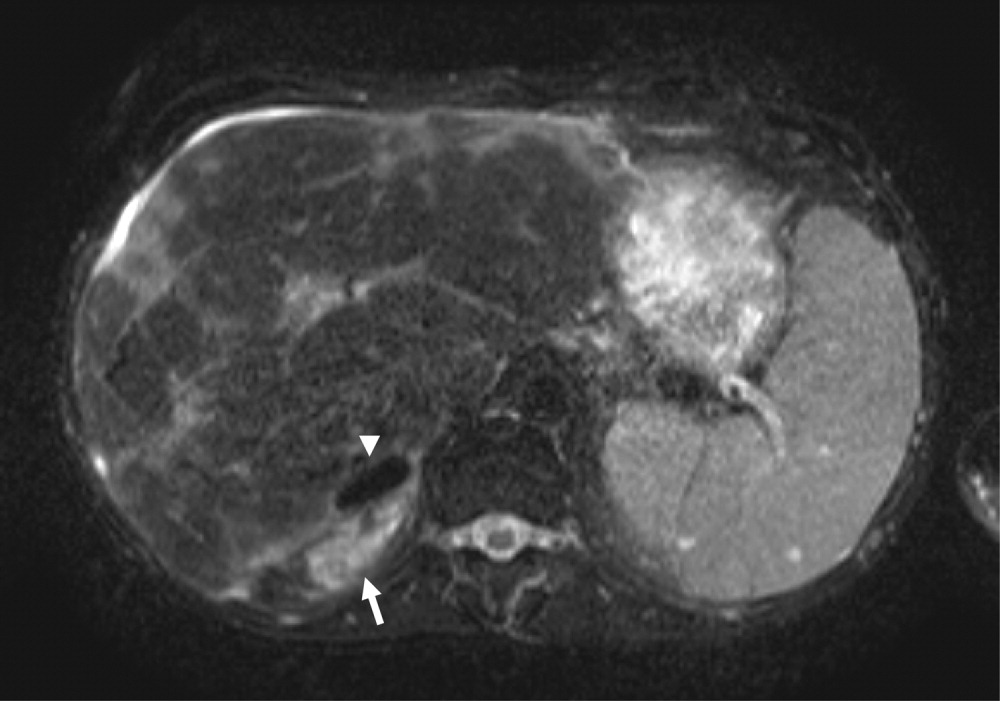

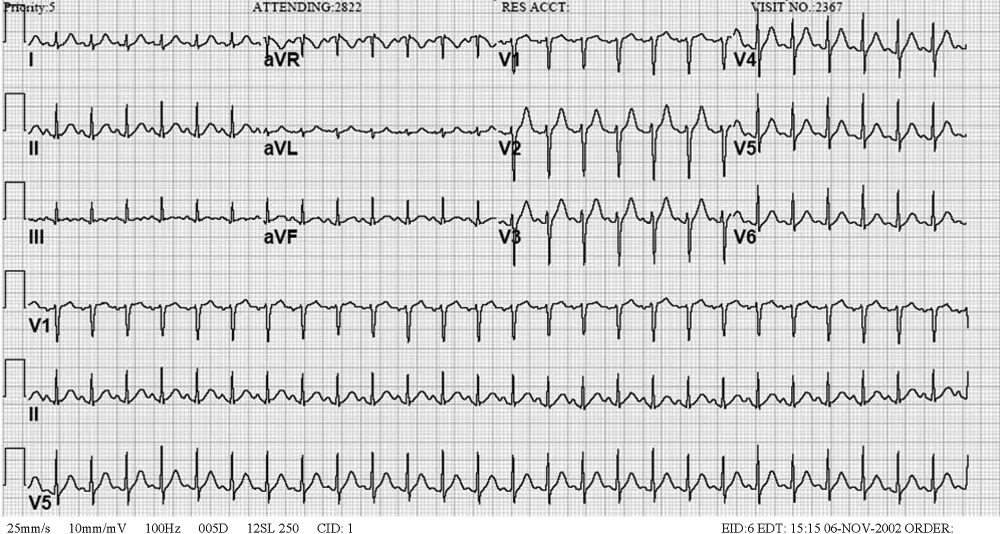

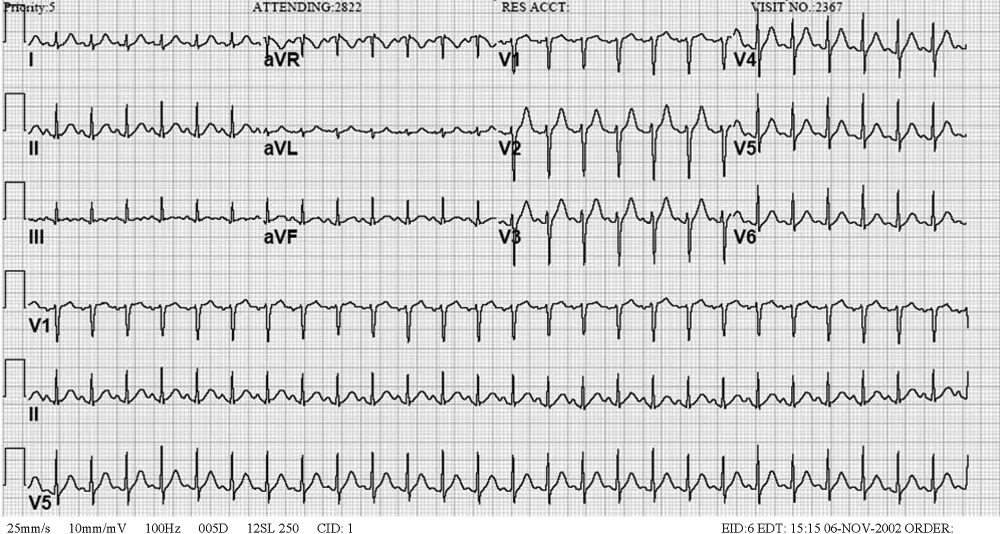

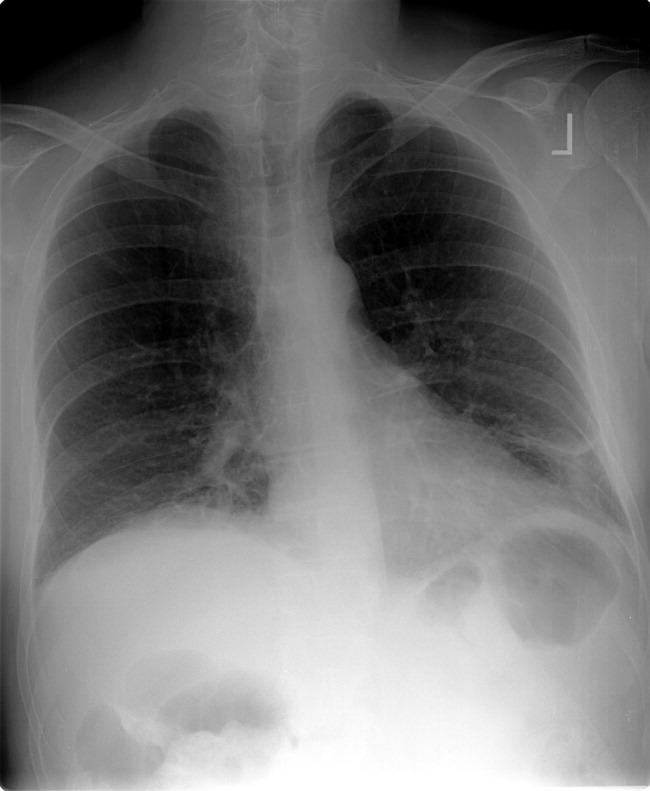

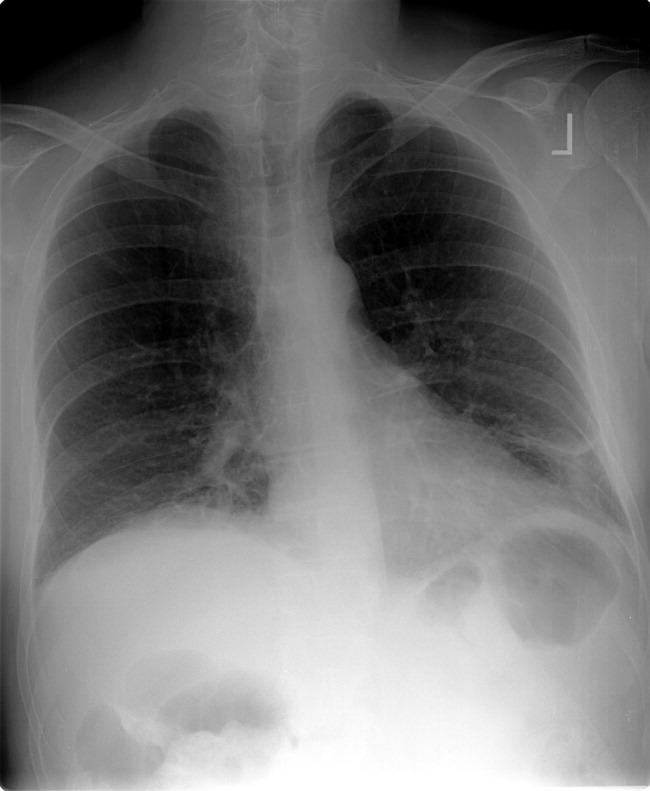

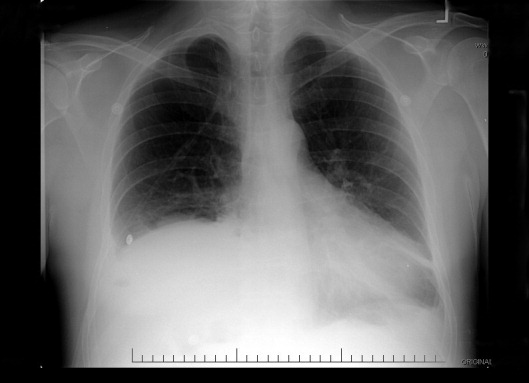

Physical examination revealed a well‐appearing man with normal vital signs. His skin had well‐defined circumscribed pink plaques, mostly 1‐2 cm in size, with thick, silvery scales in the ears and on the dorsal and ventral arms and legs, chest, back, face, and scalp. There were no pustules or other signs of infection (Figs. 1and 2). The nails exhibited distal onycholysis, oil spots, and rare pits. His posterior pharynx was mildly erythematous. The results of cardiovascular, pulmonary, and abdominal examinations were normal.

Although other scaling skin conditions such as eczema, irritant dermatitis, or malignancy remain possible, his rash is most consistent with widespread psoriasis. I would consider immunological changes that may have caused a remarkably altered and more severe expression of his chronic disease, for example, recent steroid therapy or HIV infection. The company a rash keeps helps frame the differential diagnosis. Based on the patient's well appearance, the time course, his minimal systemic symptoms, and the appearance of the rash, my leading considerations are psoriasis or an allergic dermatitis. Cutaneous T‐cell malignancy, with its indolent and sometimes protean manifestations, remains possible in a patient of his age. I would now consult a dermatologist for 3 reasons: this patient has a chronic disease that I do not manage beyond basic treatments (eg, topical steroids), he has an undiagnosed illness with substantial dermatologic manifestations, and he may need a skin biopsy for definitive diagnosis.

The dermatology team diagnosed a guttate psoriasis flare, possibly associated with streptococcal pharyngitis. The differential diagnosis included secondary syphilis, although the team believed this was less likely. The dermatology team recommended obtaining a throat culture, streptozyme assay, and rapid plasma reagin and prescribed oral erythromycin and topical steroid ointment under a sauna suit.

I would follow his response to the prescribed steroid treatments. If the patient's course deviates from the dermatologists' expectations, I would request a skin biopsy and undertake further evaluations in search of an underlying systemic disease.

The patient followed up in the dermatology clinic 3 weeks later. His rash had worsened, and he had developed patchy alopecia and progressive edema of the face, ears, and eyes. He denied mouth or tongue swelling, difficulty breathing, or hives. The streptozyme assay was positive, but the other laboratory test results were negative.

The dermatology team diagnosed a severely inflammatory psoriasis flare and prescribed an oral retinoid, acitretin, and referred him for ultraviolet light therapy. He was unable to travel for phototherapy, and acitretin was discontinued after 1 week because of elevated serum transaminase levels. The dermatologists then prescribed oral cyclosporine.

The progression of disease despite standard treatment suggests a nonpsoriatic condition. Although medications could cause the abnormal liver tests, so could another underlying illness that involves the liver. An infiltrative disorder of the skin with hair follicle destruction and local lymphedema could explain both alopecia and facial edema.

I am unable account for his clinical features with a single disease, so the differential remains broad, including severe psoriasis, an infiltrating cutaneous malignancy, or a toxic exposure. Arsenic poisoning causes hyperkeratotic skin lesions, although he lacks the associated gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms. I would not have added the potentially toxic cyclosporine.

When he returned to dermatology clinic 1 week later, his rash and facial swelling had worsened. He also reported muscle and joint aches, fatigue, lightheadedness, anorexia, nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and dyspnea on exertion. He denied fever, chills, and night sweats.

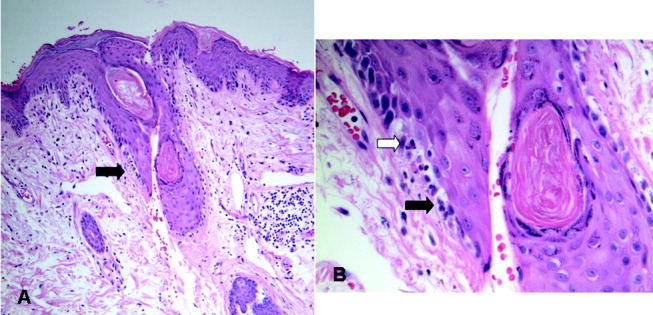

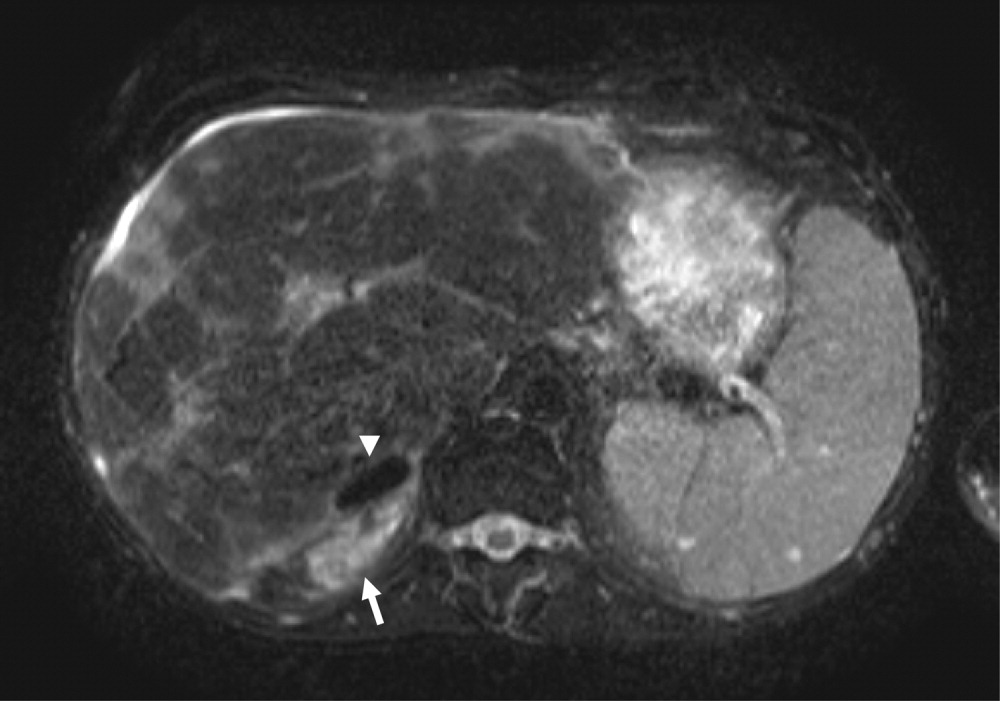

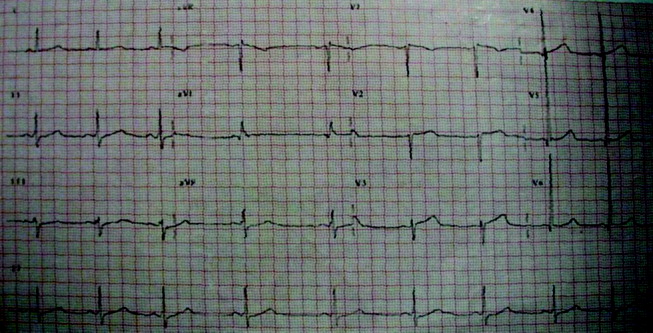

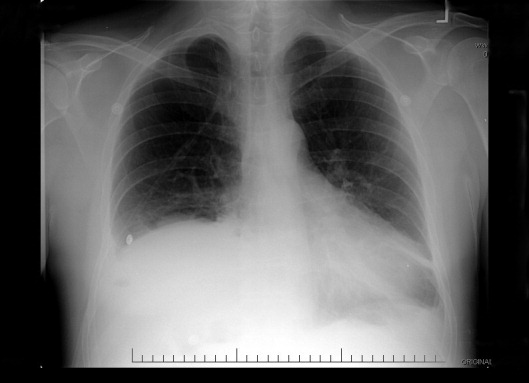

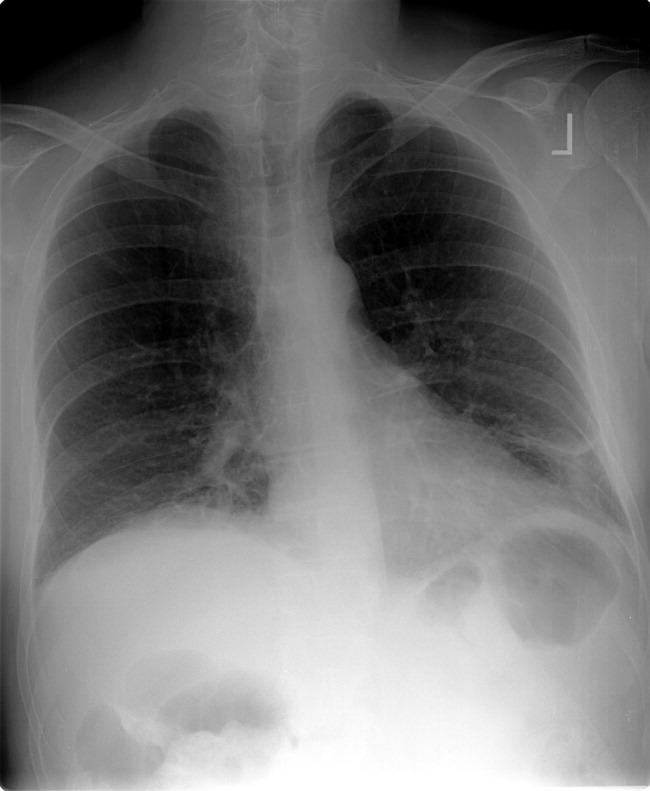

He appeared ill and used a cane to arise and walk. His vital signs and oxygen saturation were normal. He had marked swelling of his face, diffuse erythema and swelling on the chest, and widespread scaly, erythematous plaques (Fig. 3). The proximal nail folds of his fingers were erythematous, with ragged cuticles. His abdomen was mildly distended, but the rest of the physical examination was normal.

He has become too systemically ill to attribute his condition to psoriasis. The nail findings suggest dermatomyositis, which could explain many of his findings. The diffuse erythema and his difficulty walking are consistent with its skin and muscle involvement. Dyspnea could be explained by dermatomyositis‐associated interstitial lung disease. A dermatomyositis‐associated hematological or solid malignancy could account for his multisystem ailments and functional decline. A point against dermatomyositis is the relatively explosive onset of his disease. He should be carefully examined for any motor weakness. With his progressive erythroderma, I am also concerned about an advancing cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma (with leukemic transformation).

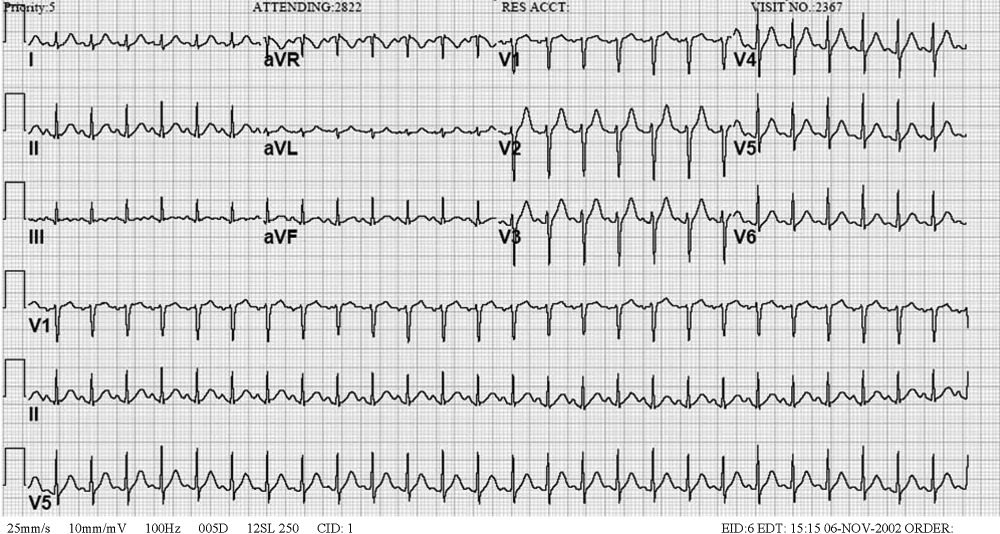

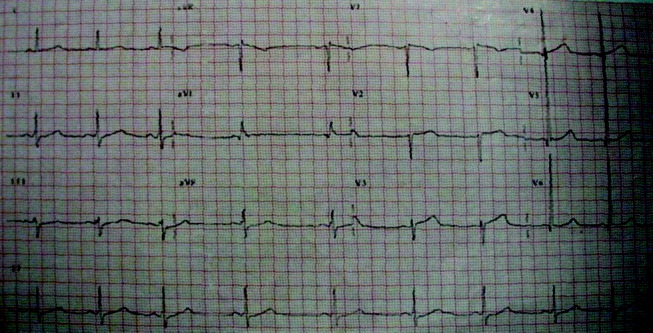

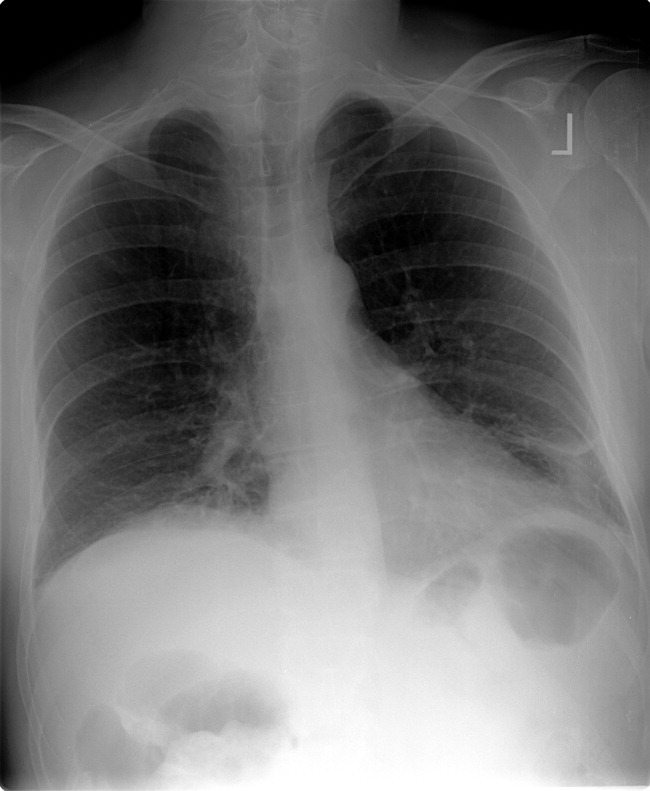

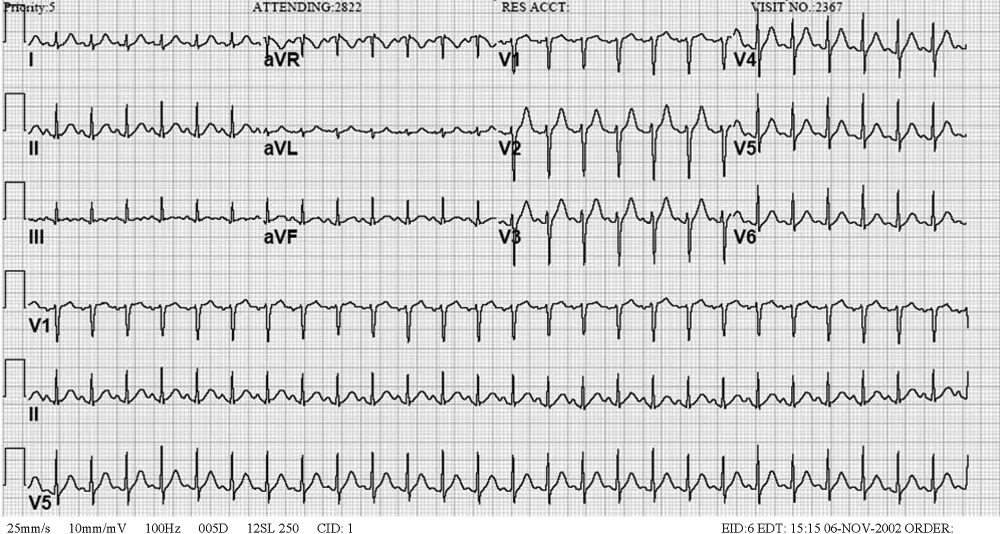

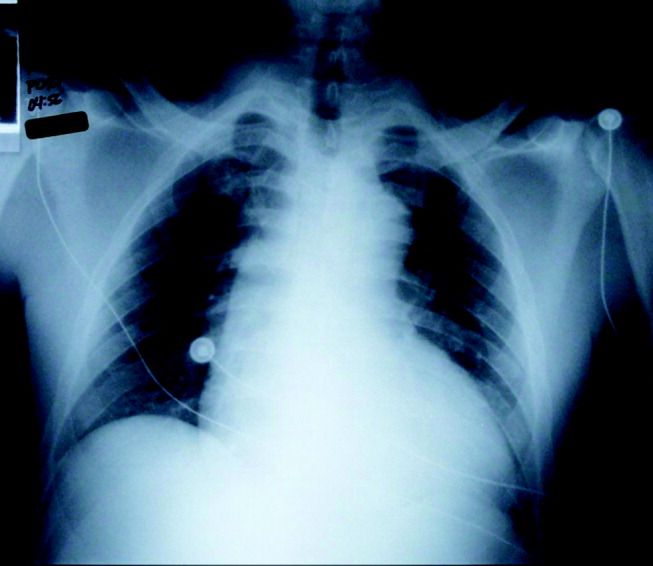

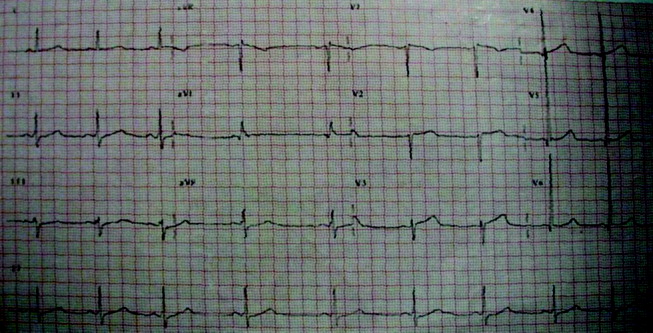

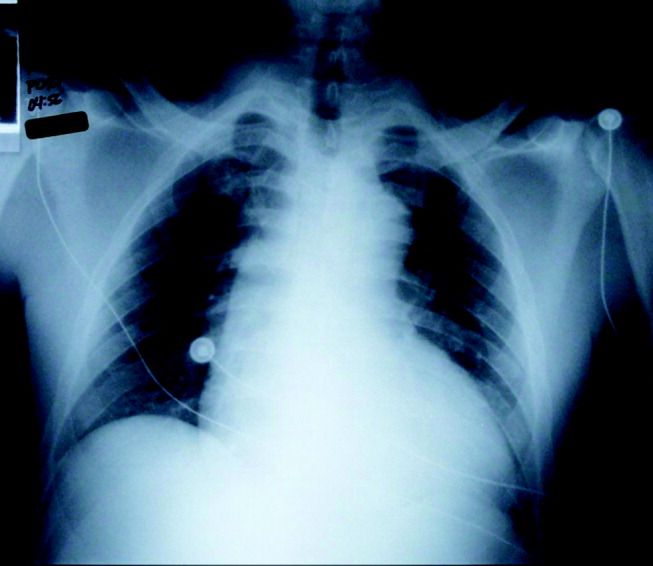

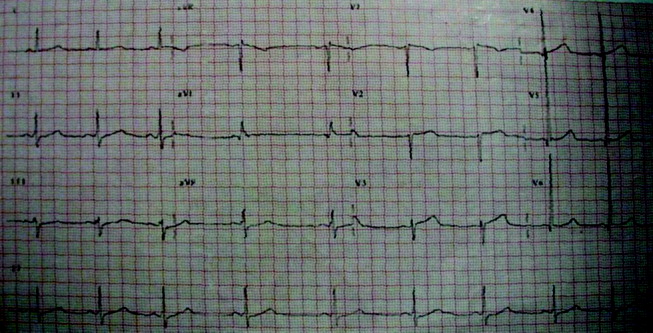

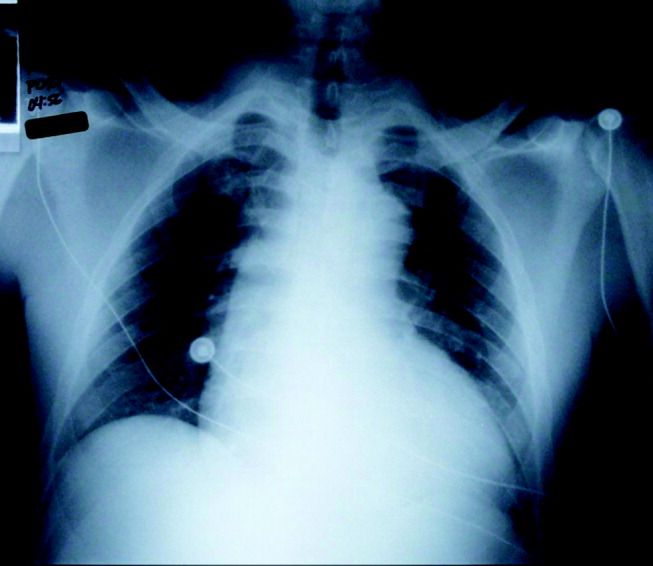

Blood tests revealed the following values: white‐blood‐cell count, 8700/L; hematocrit, 46%; platelet count, 172,000/L; blood urea nitrogen, 26 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.0 mg/dL; glucose, 199 mg/dL; albumin, 3.1 g/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 172 U/L (normal range 45‐129); alanine aminotransferase, 75 U/L (normal range 0‐39 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 263 U/L (normal range 0‐37 U/L); total bilirubin, 1.1 mg/dL; prothrombin time, 16 seconds (normal range 11.7‐14.3 seconds), and serum creatinine, kinase, 4253 U/L (normal range 0‐194 U/L). HIV serology was negative. Urinalysis revealed trace protein. The results of chest radiographs and an electrocardiogram were normal.

The liver function tests results are consistent with medication effects or liver involvement in a systemic disease. The creatinine kinase elevation is consistent with a myopathy such as dermatomyositis. A skin biopsy would still be useful. Depending on those results, he may need a muscle biopsy, urine heavy metal testing, and computed tomography body imaging. Considering his transaminase and creatinine kinase elevations, I would discontinue lovastatin.

The patient was hospitalized. Further questioning revealed that he had typical Raynaud's phenomenon and odynophagia. A detailed neurological examination showed weakness (3/5) of the triceps and iliopsoas muscles and difficulty rising from a chair without using his arms. Dermatoscopic examination of the proximal nail folds showed dilated capillary loops and foci of hemorrhage.

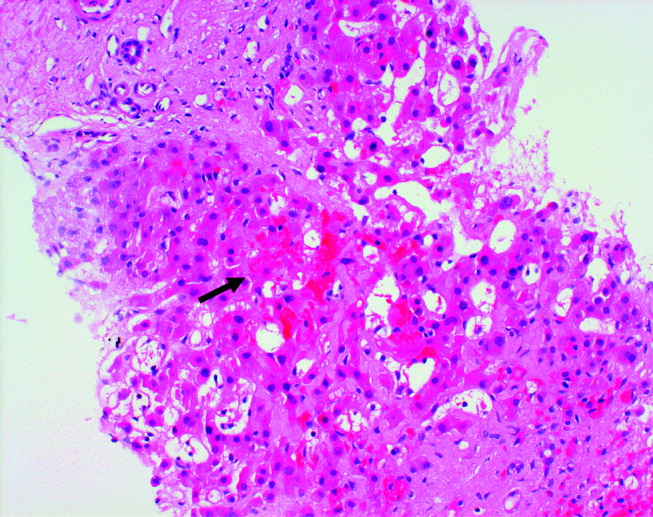

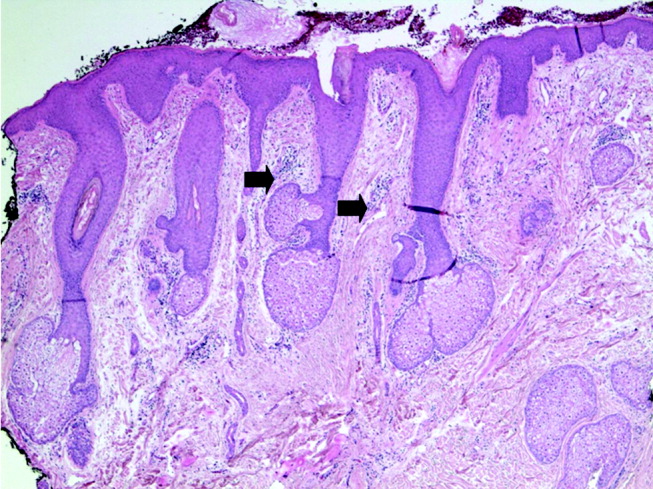

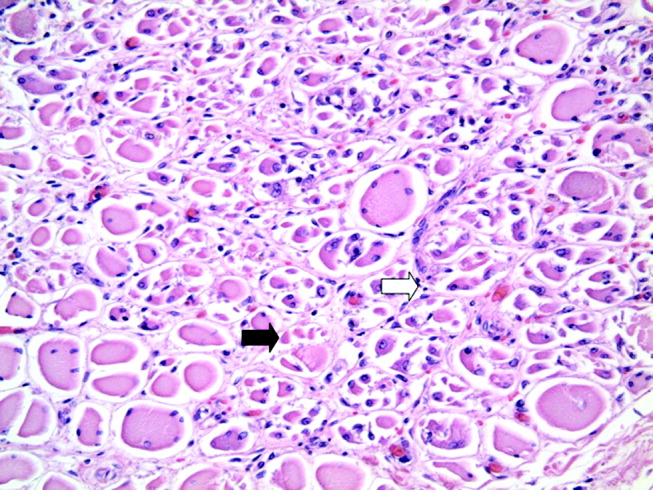

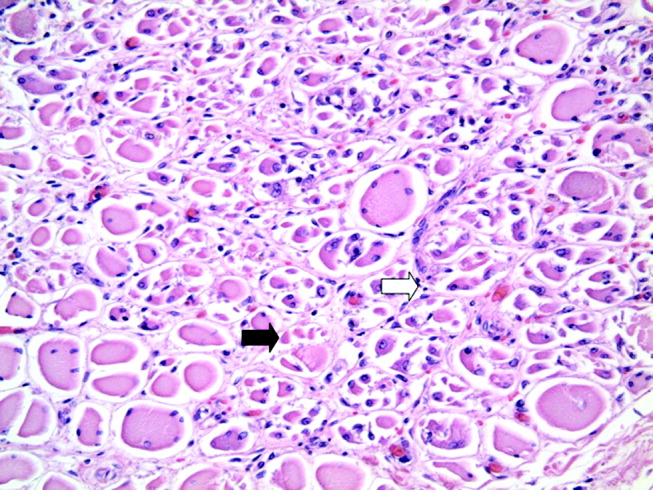

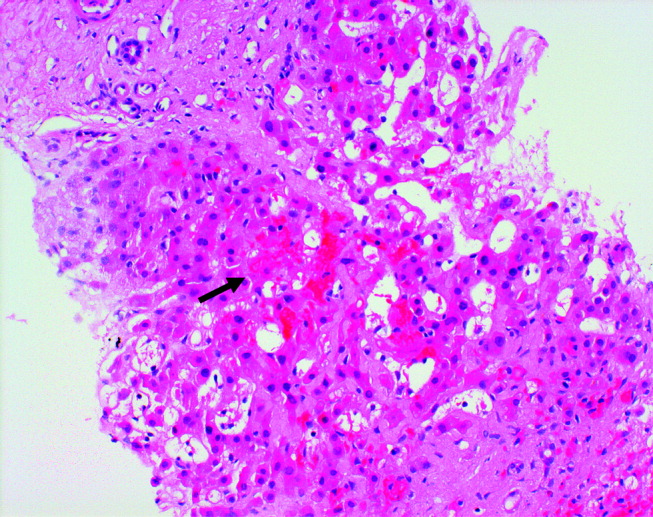

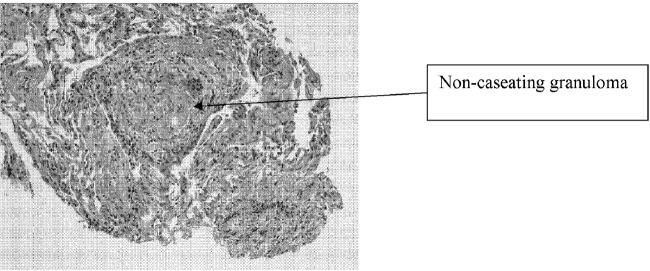

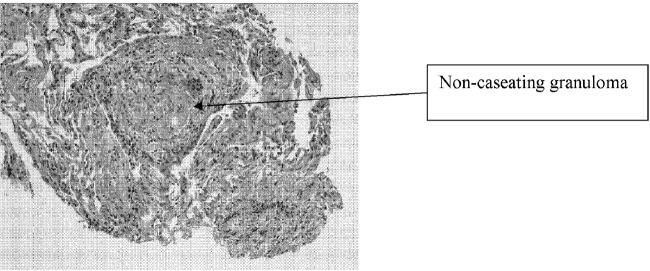

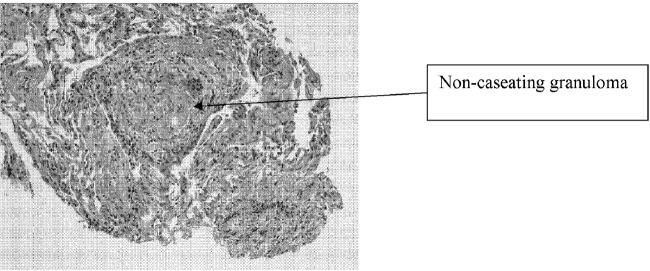

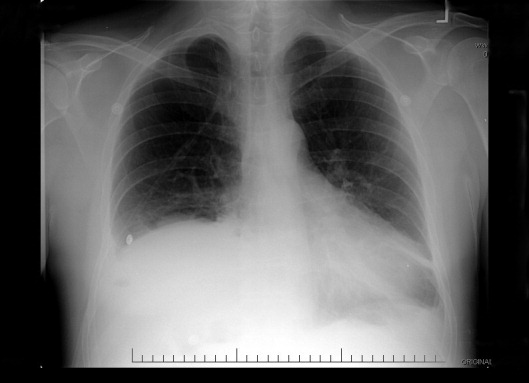

Blood tests showed a lactate dehydrogenase level of 456 U/L (normal range 0‐249 U/L) and an aldolase of 38 U/L (normal range 1.2‐7.6 U/L). Tests for antinuclear antibodies, anti‐Jo antibody, and antimyeloperoxidase antibodies were negative. Two skin biopsies were interpreted by general pathology as consistent with partially treated psoriasis, whereas another showed nonspecific changes with minimal superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammation (Fig. 4). Lisinopril was discontinued because of its possible contribution to the facial edema.

Dermatomyositis is now the leading diagnosis. Characteristic features include his proximal muscle weakness, Raynaud's phenomenon, and dilated nailfold capillary loops. I am not overly dissuaded by the negative antinuclear antibodies, but because of additional atypical features (ie, extensive cutaneous edema, rapid onset, illness severity, prominent gastrointestinal symptoms), a confirmatory muscle biopsy is needed. Endoscopy of the proximal aerodigestive tract would help evaluate the odynophagia. There is little to suggest infection, malignancy, or metabolic derangement.

The inpatient medical team considered myositis related to retinoid or cyclosporine therapy. They discontinued cyclosporine and began systemic corticosteroid therapy. Within a few days, the patient's rash, muscle pain, and weakness improved, and the elevated transaminase and creatinine kinase levels decreased.

Dermatology recommended an evaluation for dermatomyositis‐associated malignancy, but the medicine team and rheumatology consultants, noting the lack of classic skin findings (heliotrope rash and Gottron's papules) and the uncharacteristically rapid onset and improvement of myositis, suggested delaying the evaluation until dermatomyositis was proven.

An immediate improvement in symptoms with steroids is nonspecific, often occurring in autoimmune, infectious, and neoplastic diseases. This juncture in the case is common in complex multisystem illnesses, where various consultants may arrive at differing conclusions. With both typical and atypical features of dermatomyositis, where should one set the therapeutic threshold, that is, the point where one ends testing, accepts a diagnosis, and initiates treatment? Several factors raise the level of certainty I would require. First, dermatomyositis is quite rare. Adding atypical features further increases the burden of proof for that illness. Second, the existence of alternative possibilities (admittedly of equal uncertainty) gives me some pause. Finally, the toxicity of the proposed treatments raises the therapeutic threshold. Acknowledging that empiric treatment may be indicated for a severely ill patient at a lower level of certainty, I would hesitate to commit a patient to long‐term steroids without being confident of the diagnosis. I would therefore require a muscle biopsy, or at least electromyography to support or exclude dermatomyositis.

The patient was discharged from the hospital on high‐dose prednisone. He underwent electromyography, which revealed inflammatory myopathic changes more apparent in the proximal than distal muscles. These findings were thought to be compatible with dermatomyositis, although the fibrillations and positive sharp waves characteristic of acute inflammation were absent, perhaps because of corticosteroid therapy.

The patient mistakenly stopped taking his prednisone. Within days, his weakness and skin rash worsened, and he developed nausea with vomiting. He returned to clinic, where his creatinine kinase level was again found to be elevated, and he was rehospitalized. Oral corticosteroid therapy was restarted with prompt improvement. On review of the original skin biopsies, a dermatopathologist observed areas of thickened dermal collagen and a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, both consistent with connective tissue disease.

These 3 additional findings (ie, electromyography results, temporally established steroid responsiveness, and the new skin biopsy interpretation) in aggregate support the diagnosis of dermatomyositis, but the nausea and vomiting are unusual. I would discuss these results with a rheumatologist and still request a confirmatory muscle biopsy. Because diagnosing dermatomyositis should prompt consideration of seeking an underlying malignancy in a patient of this age group, I would repeat a targeted history and physical examination along with age‐ and risk‐factor‐appropriate screening. If muscle biopsy results are not definitive, finding an underlying malignancy would lend support to dermatomyositis.

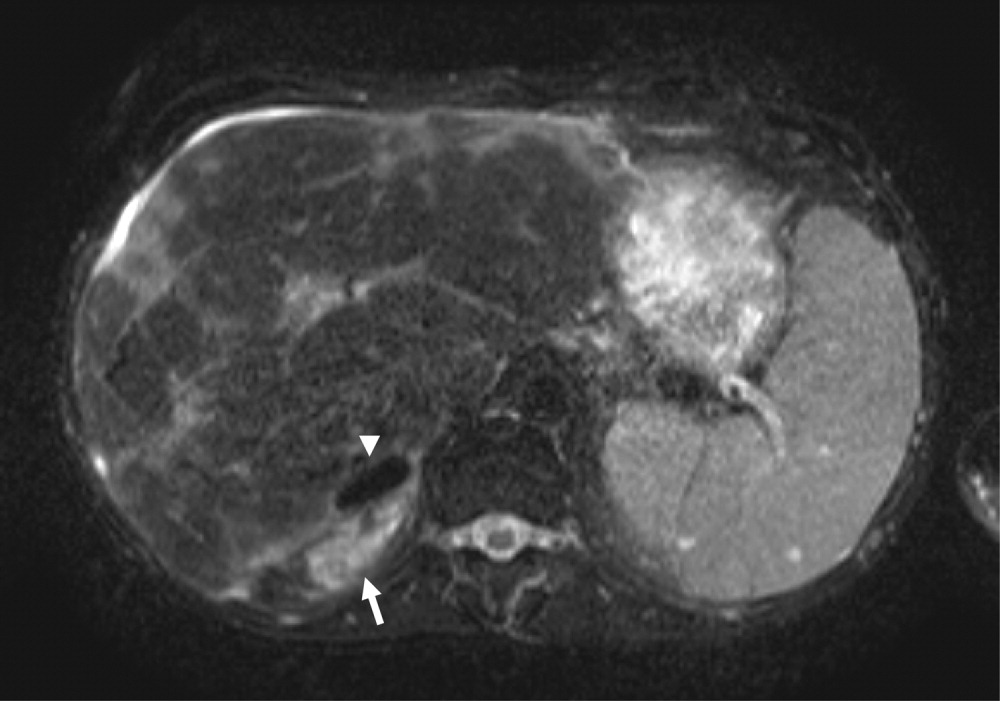

While hospitalized, the patient complained of continued odynophagia and was noted to have oral candidiasis. Upper endoscopy, undertaken to evaluate for esophageal candidiasis, revealed a mass at the gastroesophageal junction. Biopsy revealed gastric‐type adenocarcinoma. An abdominal computed tomography scan demonstrated 3 hypodense hepatic lesions, evidence of cirrhosis, and ascites. Cytology of paracentesis fluid revealed cells compatible with adenocarcinoma. The patient died in hospice care 2 weeks later.

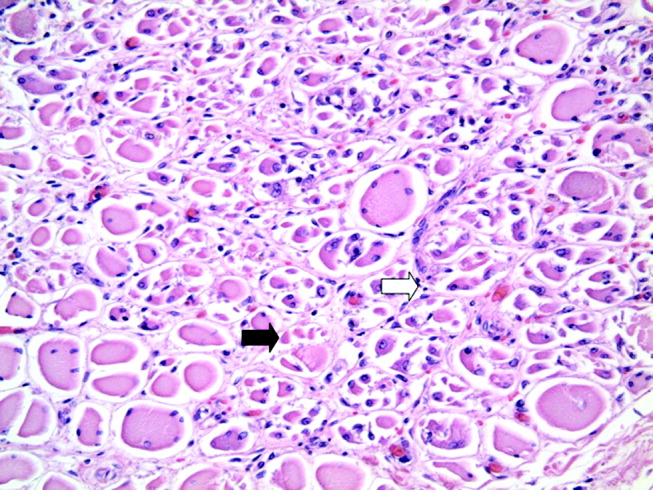

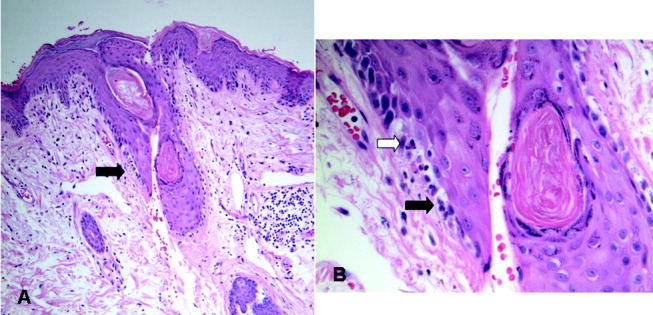

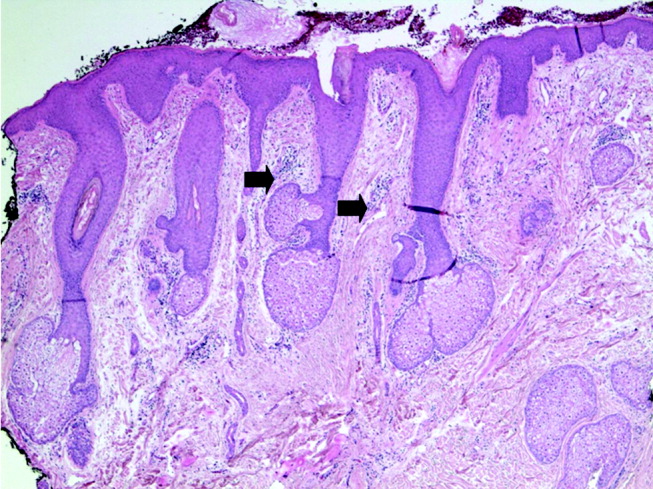

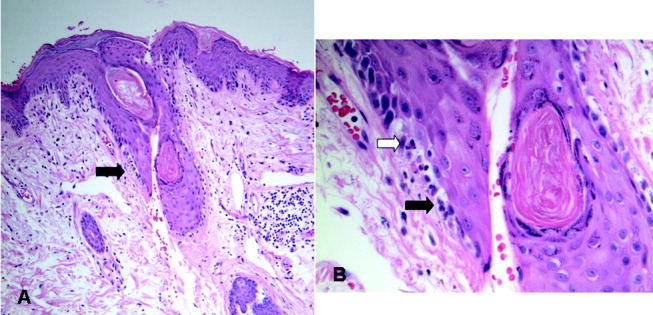

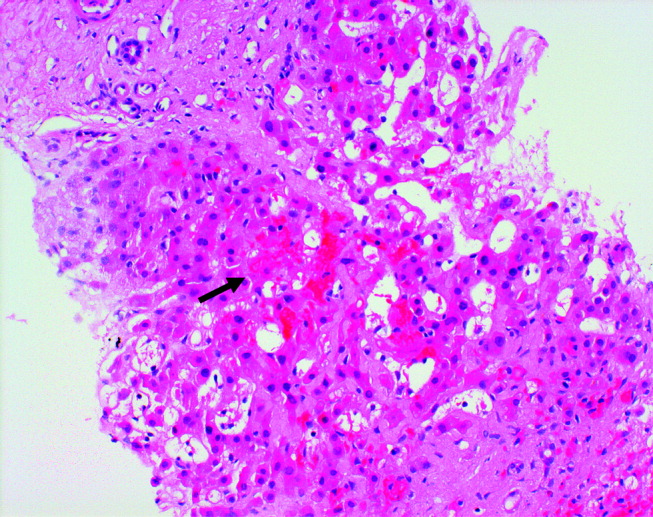

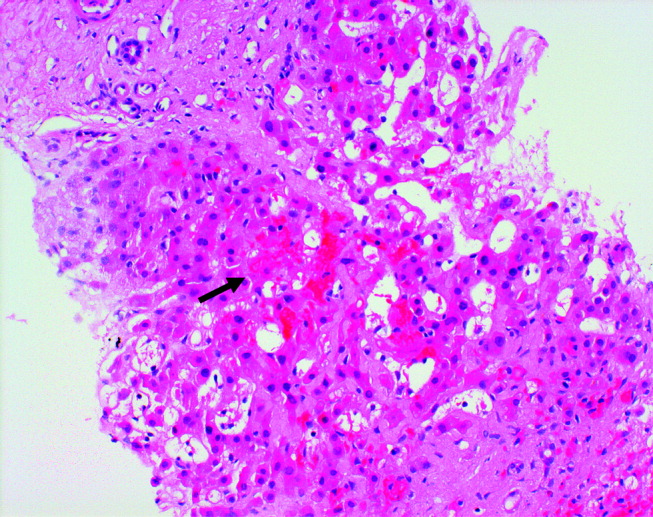

At autopsy, he had metastatic gastric‐type adenocarcinoma. A muscle biopsy (Fig. 5) revealed muscle atrophy with small foci of lymphocytic infiltrates, most compatible with dermatomyositis. Another dermatopathologist reviewed the skin biopsies and noted interface dermatitis, which is typical of connective tissue diseases like dermatomyositis (Fig. 6A,B).

COMMENTARY

Dermatomyositis is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy characterized by endomysial inflammation and muscle weakness and differentiated from other myopathies by the presence of a rash.1 Muscle disease may manifest with or precede the rash, but up to 40% of patients present with skin manifestations alone, an entity called amyopathic dermatomyositis.2 When present, the myositis generally develops over months, but the onset can be acute.1 The weakness is typically symmetrical and proximal,1 and many patients have oropharyngeal dysphagia.3

The characteristic rash is erythematous, symmetrical, and photodistributed.4 Classic cutaneous findings are the heliotrope rash (violaceous eyelid erythema), which is pathognomonic but uncommon, and the more common Gottron's papules (violaceous, slightly elevated papules and plaques on bony prominences and extensor surfaces, especially the knuckles).4 Other findings include periorbital edema, scalp dermatitis, poikiloderma (ie, hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, atrophy, and telangiectasia), periungual erythema, and dystrophic cuticles.2 The cutaneous manifestations of dermatomyositis may be similar to those of psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, lichen planus, rosacea, polymorphous light eruption, drug eruption, atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, or allergic contact dermatitis.4

Diagnosing dermatomyositis requires considering clinical, laboratory, electromyographical, and histological evidence, as there are no widely accepted, validated diagnostic criteria.1, 5 The diagnosis is usually suspected if there is a characteristic rash and symptoms of myositis (eg, proximal muscle weakness, myalgias, fatigue, or an inability to swallow). When the patient has an atypical rash, skin biopsy can differentiate dermatomyositis from other conditions, except lupus, which shares the key finding of interface dermatitis.2 The histological findings can be variable and subtle,6 so consultation with a dermatopathologist may be helpful.

Myositis may be confirmed by various studies. Most patients have elevated muscle enzymes (ie, creatinine kinase, aldolase, lactate dehydrogenase, or transaminases)1; for those who do not, magnetic resonance imaging can be helpful in detecting muscle involvement and locating the best site for muscle biopsy.7 Electromyography reveals nonspecific muscle membrane instability.8 Muscle biopsy shows muscle fiber necrosis, perifascicular atrophy, and perivascular and perifascicular lymphocytic infiltrates. These can be patchy, diminished by steroid use, and occasionally seen in noninflammatory muscular dystrophies.8 For a patient with typical myositis and a characteristic rash, muscle biopsy may be unnecessary.1

The clinical utility of serologic testing for diagnosing dermatomyositis is controversial.2 Myositis‐specific antibody testing is insensitive but specific; these antibodies include Jo‐1, an antisynthetase antibody that predicts incomplete response to therapy and lung involvement, and Mi‐2, which is associated with better response to therapy.2, 9, 10 The sensitivity and specificity of antinuclear antibodies are both approximately 60%.10

Patients with dermatomyositis have higher rates of cancers than age‐matched controls, and nearly 25% of patients are diagnosed with a malignancy at some point during the course of the disease.11 Malignancies are typically solid tumors that manifest within 3 years of the diagnosis,1214 although the increased risk may exist for at least 5 years.14 There is a 10‐fold higher risk of ovarian cancer in women with dermatomyositis.12, 15 Other associated malignancies include lung, gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, and breast carcinomas and non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma.14

Recommendations for screening affected patients for cancer have changed over the years, with increasing evidence of an association between dermatomyositis and malignancy and evolving improvements in diagnostic techniques.16 Many authorities recommend that all adult patients with dermatomyositis be evaluated for cancer, including a complete physical examination, basic hematological tests, age‐ and sex‐appropriate screening (eg, mammography, pap smear, and colonoscopy), and chest x‐ray.16 Some would add upper endoscopy; imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; gynecological examination; and serum CA‐125 level to better evaluate for the most common malignancies (ie, ovarian, gastric, lung, and pancreatic carcinomas and non‐Hodgkins lymphoma).12, 1720

In 19% of adults, dermatomyositis overlaps with other autoimmune disorders, usually systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis.21 These manifest as Raynaud's phenomenon, arthritis, esophageal dysmotility, renal disease, or neuropathy.21 Other potentially serious systemic manifestations of dermatomyositis include proximal dysphagia from pharyngeal myopathy; distal dysphagia from esophageal dysmotility in systemic sclerosis overlap; pulmonary disease from autoimmune interstitial lung disease or aspiration; cardiac disease from conduction abnormalities, myocarditis, pericarditis, and valvular disease; and rhabdomyolysis.2

Treatment of dermatomyositis requires systemic immunosuppression with 1 or more agents. The prognosis of dermatomyositis is variable. Mortality at 5 years ranges from 23% to 73%. At least a third of patients are left with mild to severe disability.1 In addition to older age, predictors of poor outcome include male sex, dysphagia, longstanding symptoms before treatment, pulmonary or cardiac involvement, and presence of antisynthetase antibodies.22

Dermatomyositis is often treated in the outpatient setting, but there are many reasons for hospitalization. Complications of treatment, like infection or adverse effects of medications, could result in hospitalization. Treatment with intravenous pulse corticosteroids or IVIG may require inpatient administration if no infusion center is available. Other indications for inpatient evaluation include the consequences of various malignancies and the more severe expression of systemic complications of dermatomyositis (eg, dysphagia and pulmonary, cardiac, or renal disease).

Every parent knows the plaintive backseat whine, Are we there, yet? Clinicians may also experience this feeling when attempting to diagnose a perplexing illness, especially one that lacks a definitive diagnostic test. It was easy for this patient's doctors to assume initially that his new rash was a manifestation of his long‐standing psoriasis. Having done so, they could understandably attribute the subsequent findings to either evolution of this disease or to consequences of the prescribed treatments, rather than considering a novel diagnosis. Only when faced with new (or newly appreciated) findings suggesting myopathy did the clinicians (and our discussant) consider the diagnosis of dermatomyositis. Even then, the primary inpatient medical team and their consultants were unsure when they had sufficient evidence to be certain.

Several factors compounded the difficulty of making a diagnosis in this case: the clinicians were dealing with a rare disease; they were considering alternative diagnoses (ie, psoriasis or a toxic effect of medication); and the disease presented somewhat atypically. The clinicians initially failed to consider and then accept the correct diagnosis because the patient's rash was not classic, his biopsy was interpreted as nonspecific, and he lacked myositis at presentation. Furthermore, when the generalists sought expert assistance, they encountered a difference of opinion among the consultants. These complex situations should goad the clinician into carefully considering the therapeutic threshold, that is, the transition point from diagnostic testing to therapeutic intervention.23 With complex cases like this, it may be difficult to know when one has reached a strongly supported diagnosis, and frequently asking whether we are there yet may be appropriate.

Take‐Home Points for the Hospitalist

-

A skin rash, which may have typical or atypical features, distinguishes dermatomyositis from other acquired myopathies.

-

Consider consultation with pathology specialists for skin and muscle biopsies.

-

Ovarian, lung, gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, and breast carcinomas and non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma are the most common cancers associated with dermatomyositis.

-

In addition to age‐appropriate cancer screening, consider obtaining upper endoscopy, imaging of the chest/abdomen/pelvis, and CA‐125.

-

Patients with dermatomyositis and no obvious concurrent malignancy need long‐term outpatient follow‐up for repeated malignancy screening.

- ,.Polymyositis and dermatomyositis.Lancet.2003;362:971–982.

- .Dermatomyositis.Lancet.2000;355:53–47.

- ,,,.Oropharyngeal dysphagia in polymyositis/dermatomyositis.Clin Neurol Neurosurg.2004;107(1):32–37.

- ,.Skin involvement in dermatomyositis.Curr Opin Rheumatol.2003;15:714–22.

- ,,,,,.Novel classification of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies based on overlap syndrome features and autoantibodies: analysis of 100 French Canadian patients.Medicine (Baltimore).2005;84:231–249.

- .Skin Pathology.2nd ed.New York:Churchill Livingstone;2002.

- ,.Utility of magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of patients with inflammatory myopathies.Curr Rheumatol Rep.2001;3:334–245.

- ,,.Is it really myositis? A consideration of the differential diagnosis.Curr Opin Rheumatol2004;16:684–691.

- .Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: autoantibody update.Curr Rheumatol Rep.2002;4:434–441.

- ,,.Laboratory assessment in musculoskeletal disorders.Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol.2003;17:475–494.

- ,.Dermatomyositis.Clin Dermatol.2006;24:363–373.

- ,,, et al.Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population‐based study.Lancet.2001;357:96–100.

- ,,, et al.Cancer‐associated myositis: clinical features and prognostic signs.Ann N Y Acad Sci.2005;1051:64–71.

- ,,,,.Incidence of malignant disease in biopsy‐proven inflammatory myopathy. A population‐based cohort study.Ann Intern Med.2001;134:1087–1095.

- ,,.Risk of cancer in patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis, and follow‐up implications: a Scottish population‐based cohort study.Br J Cancer.2001;85 (1):41–45.

- .When and how should the patient with dermatomyositis or amyopathic dermatomyositis be assessed for possible cancer?Arch Dermatol.2002;138:969–971.

- ,,.Ovarian cancer in patients with dermatomyositis.Medicine (Baltimore).1994;73(3):153–160.

- ,,,.Dermatomyositis sine myositis: association with malignancy.J Rheumatol.1996;23 (1):101–105.

- ,,, et al.Tumor antigen markers for the detection of solid cancers in inflammatory myopathies.Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev.2005;14:1279–1282.

- ,,, et al.Routine vs extensive malignancy search for adult dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a study of 40 patients.Arch Dermatol.2002;138:885–890.

- ,,,,,.Dermatomyositis: a dermatology‐based case series.J Am Acad Dermatol.1998;38:397–404.

- ,,, et al.Long‐term outcome in polymyositis and dermatomyositis.Ann Rheum Dis.2006;65:1456–1461.

- .Our stubborn quest for diagnostic certainty. A cause of excessive testing.N Engl J Med.1989;320:1489–1491.

A 62‐year‐old man with psoriasis for more than 30 years presented to the emergency department with a scaly, pruritic rash involving his face, trunk, and extremities that he had had for the past 10 days. The rash was spreading and not responding to application of clobetasol ointment, which had helped his psoriasis in the past. He also reported mild pharyngitis, headache, and myalgias.

A patient with a chronic skin condition presenting with a new rash means the clinician must consider whether it is an alternative manifestation of the chronic disorder or a new illness. Psoriasis takes many forms including guttate psoriasis, which presents with small, droplike plaques and frequently follows respiratory infections (particularly those caused by Streptococcus). Well‐controlled psoriasis rarely transforms after 3 decades, so I would consider other conditions. The tempo of illness makes certain life‐threatening syndromes, including Stevens‐Johnson, toxic shock, and purpura fulminans, unlikely. An allergic reaction, atopic dermatitis, or medication reaction is possible. Infections, either systemic (eg, syphilis) or dermatologic (eg, scabies), should be considered. Photosensitivity could involve the sun‐exposed areas, such as the extremities and face. Seborrheic dermatitis can cause scaling lesions of the face and trunk but not the extremities. Vasculitis merits consideration, but dependent regions are typically affected more than the head. Mycosis fungoides or a paraneoplastic phenomenon could cause a diffuse rash in this age group.

The patient had diabetes mellitus, hypertension, diverticulosis, and depression. Three months earlier he had undergone surgical drainage of a perirectal abscess. His usual medications were lovastatin, paroxetine, insulin, hydrochlorothiazide, and lisinopril. Three weeks previously he had completed a 10‐day course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for an upper respiratory infection. Otherwise, he was taking no new medications. He was allergic to penicillin. He denied substance abuse, recent travel, or risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. He worked as an automobile painter, lived with his wife, and had a pet dog.

Physical examination revealed a well‐appearing man with normal vital signs. His skin had well‐defined circumscribed pink plaques, mostly 1‐2 cm in size, with thick, silvery scales in the ears and on the dorsal and ventral arms and legs, chest, back, face, and scalp. There were no pustules or other signs of infection (Figs. 1and 2). The nails exhibited distal onycholysis, oil spots, and rare pits. His posterior pharynx was mildly erythematous. The results of cardiovascular, pulmonary, and abdominal examinations were normal.

Although other scaling skin conditions such as eczema, irritant dermatitis, or malignancy remain possible, his rash is most consistent with widespread psoriasis. I would consider immunological changes that may have caused a remarkably altered and more severe expression of his chronic disease, for example, recent steroid therapy or HIV infection. The company a rash keeps helps frame the differential diagnosis. Based on the patient's well appearance, the time course, his minimal systemic symptoms, and the appearance of the rash, my leading considerations are psoriasis or an allergic dermatitis. Cutaneous T‐cell malignancy, with its indolent and sometimes protean manifestations, remains possible in a patient of his age. I would now consult a dermatologist for 3 reasons: this patient has a chronic disease that I do not manage beyond basic treatments (eg, topical steroids), he has an undiagnosed illness with substantial dermatologic manifestations, and he may need a skin biopsy for definitive diagnosis.

The dermatology team diagnosed a guttate psoriasis flare, possibly associated with streptococcal pharyngitis. The differential diagnosis included secondary syphilis, although the team believed this was less likely. The dermatology team recommended obtaining a throat culture, streptozyme assay, and rapid plasma reagin and prescribed oral erythromycin and topical steroid ointment under a sauna suit.

I would follow his response to the prescribed steroid treatments. If the patient's course deviates from the dermatologists' expectations, I would request a skin biopsy and undertake further evaluations in search of an underlying systemic disease.

The patient followed up in the dermatology clinic 3 weeks later. His rash had worsened, and he had developed patchy alopecia and progressive edema of the face, ears, and eyes. He denied mouth or tongue swelling, difficulty breathing, or hives. The streptozyme assay was positive, but the other laboratory test results were negative.

The dermatology team diagnosed a severely inflammatory psoriasis flare and prescribed an oral retinoid, acitretin, and referred him for ultraviolet light therapy. He was unable to travel for phototherapy, and acitretin was discontinued after 1 week because of elevated serum transaminase levels. The dermatologists then prescribed oral cyclosporine.

The progression of disease despite standard treatment suggests a nonpsoriatic condition. Although medications could cause the abnormal liver tests, so could another underlying illness that involves the liver. An infiltrative disorder of the skin with hair follicle destruction and local lymphedema could explain both alopecia and facial edema.

I am unable account for his clinical features with a single disease, so the differential remains broad, including severe psoriasis, an infiltrating cutaneous malignancy, or a toxic exposure. Arsenic poisoning causes hyperkeratotic skin lesions, although he lacks the associated gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms. I would not have added the potentially toxic cyclosporine.

When he returned to dermatology clinic 1 week later, his rash and facial swelling had worsened. He also reported muscle and joint aches, fatigue, lightheadedness, anorexia, nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and dyspnea on exertion. He denied fever, chills, and night sweats.

He appeared ill and used a cane to arise and walk. His vital signs and oxygen saturation were normal. He had marked swelling of his face, diffuse erythema and swelling on the chest, and widespread scaly, erythematous plaques (Fig. 3). The proximal nail folds of his fingers were erythematous, with ragged cuticles. His abdomen was mildly distended, but the rest of the physical examination was normal.

He has become too systemically ill to attribute his condition to psoriasis. The nail findings suggest dermatomyositis, which could explain many of his findings. The diffuse erythema and his difficulty walking are consistent with its skin and muscle involvement. Dyspnea could be explained by dermatomyositis‐associated interstitial lung disease. A dermatomyositis‐associated hematological or solid malignancy could account for his multisystem ailments and functional decline. A point against dermatomyositis is the relatively explosive onset of his disease. He should be carefully examined for any motor weakness. With his progressive erythroderma, I am also concerned about an advancing cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma (with leukemic transformation).

Blood tests revealed the following values: white‐blood‐cell count, 8700/L; hematocrit, 46%; platelet count, 172,000/L; blood urea nitrogen, 26 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.0 mg/dL; glucose, 199 mg/dL; albumin, 3.1 g/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 172 U/L (normal range 45‐129); alanine aminotransferase, 75 U/L (normal range 0‐39 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 263 U/L (normal range 0‐37 U/L); total bilirubin, 1.1 mg/dL; prothrombin time, 16 seconds (normal range 11.7‐14.3 seconds), and serum creatinine, kinase, 4253 U/L (normal range 0‐194 U/L). HIV serology was negative. Urinalysis revealed trace protein. The results of chest radiographs and an electrocardiogram were normal.

The liver function tests results are consistent with medication effects or liver involvement in a systemic disease. The creatinine kinase elevation is consistent with a myopathy such as dermatomyositis. A skin biopsy would still be useful. Depending on those results, he may need a muscle biopsy, urine heavy metal testing, and computed tomography body imaging. Considering his transaminase and creatinine kinase elevations, I would discontinue lovastatin.

The patient was hospitalized. Further questioning revealed that he had typical Raynaud's phenomenon and odynophagia. A detailed neurological examination showed weakness (3/5) of the triceps and iliopsoas muscles and difficulty rising from a chair without using his arms. Dermatoscopic examination of the proximal nail folds showed dilated capillary loops and foci of hemorrhage.

Blood tests showed a lactate dehydrogenase level of 456 U/L (normal range 0‐249 U/L) and an aldolase of 38 U/L (normal range 1.2‐7.6 U/L). Tests for antinuclear antibodies, anti‐Jo antibody, and antimyeloperoxidase antibodies were negative. Two skin biopsies were interpreted by general pathology as consistent with partially treated psoriasis, whereas another showed nonspecific changes with minimal superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammation (Fig. 4). Lisinopril was discontinued because of its possible contribution to the facial edema.

Dermatomyositis is now the leading diagnosis. Characteristic features include his proximal muscle weakness, Raynaud's phenomenon, and dilated nailfold capillary loops. I am not overly dissuaded by the negative antinuclear antibodies, but because of additional atypical features (ie, extensive cutaneous edema, rapid onset, illness severity, prominent gastrointestinal symptoms), a confirmatory muscle biopsy is needed. Endoscopy of the proximal aerodigestive tract would help evaluate the odynophagia. There is little to suggest infection, malignancy, or metabolic derangement.

The inpatient medical team considered myositis related to retinoid or cyclosporine therapy. They discontinued cyclosporine and began systemic corticosteroid therapy. Within a few days, the patient's rash, muscle pain, and weakness improved, and the elevated transaminase and creatinine kinase levels decreased.

Dermatology recommended an evaluation for dermatomyositis‐associated malignancy, but the medicine team and rheumatology consultants, noting the lack of classic skin findings (heliotrope rash and Gottron's papules) and the uncharacteristically rapid onset and improvement of myositis, suggested delaying the evaluation until dermatomyositis was proven.

An immediate improvement in symptoms with steroids is nonspecific, often occurring in autoimmune, infectious, and neoplastic diseases. This juncture in the case is common in complex multisystem illnesses, where various consultants may arrive at differing conclusions. With both typical and atypical features of dermatomyositis, where should one set the therapeutic threshold, that is, the point where one ends testing, accepts a diagnosis, and initiates treatment? Several factors raise the level of certainty I would require. First, dermatomyositis is quite rare. Adding atypical features further increases the burden of proof for that illness. Second, the existence of alternative possibilities (admittedly of equal uncertainty) gives me some pause. Finally, the toxicity of the proposed treatments raises the therapeutic threshold. Acknowledging that empiric treatment may be indicated for a severely ill patient at a lower level of certainty, I would hesitate to commit a patient to long‐term steroids without being confident of the diagnosis. I would therefore require a muscle biopsy, or at least electromyography to support or exclude dermatomyositis.

The patient was discharged from the hospital on high‐dose prednisone. He underwent electromyography, which revealed inflammatory myopathic changes more apparent in the proximal than distal muscles. These findings were thought to be compatible with dermatomyositis, although the fibrillations and positive sharp waves characteristic of acute inflammation were absent, perhaps because of corticosteroid therapy.

The patient mistakenly stopped taking his prednisone. Within days, his weakness and skin rash worsened, and he developed nausea with vomiting. He returned to clinic, where his creatinine kinase level was again found to be elevated, and he was rehospitalized. Oral corticosteroid therapy was restarted with prompt improvement. On review of the original skin biopsies, a dermatopathologist observed areas of thickened dermal collagen and a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, both consistent with connective tissue disease.

These 3 additional findings (ie, electromyography results, temporally established steroid responsiveness, and the new skin biopsy interpretation) in aggregate support the diagnosis of dermatomyositis, but the nausea and vomiting are unusual. I would discuss these results with a rheumatologist and still request a confirmatory muscle biopsy. Because diagnosing dermatomyositis should prompt consideration of seeking an underlying malignancy in a patient of this age group, I would repeat a targeted history and physical examination along with age‐ and risk‐factor‐appropriate screening. If muscle biopsy results are not definitive, finding an underlying malignancy would lend support to dermatomyositis.

While hospitalized, the patient complained of continued odynophagia and was noted to have oral candidiasis. Upper endoscopy, undertaken to evaluate for esophageal candidiasis, revealed a mass at the gastroesophageal junction. Biopsy revealed gastric‐type adenocarcinoma. An abdominal computed tomography scan demonstrated 3 hypodense hepatic lesions, evidence of cirrhosis, and ascites. Cytology of paracentesis fluid revealed cells compatible with adenocarcinoma. The patient died in hospice care 2 weeks later.

At autopsy, he had metastatic gastric‐type adenocarcinoma. A muscle biopsy (Fig. 5) revealed muscle atrophy with small foci of lymphocytic infiltrates, most compatible with dermatomyositis. Another dermatopathologist reviewed the skin biopsies and noted interface dermatitis, which is typical of connective tissue diseases like dermatomyositis (Fig. 6A,B).

COMMENTARY

Dermatomyositis is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy characterized by endomysial inflammation and muscle weakness and differentiated from other myopathies by the presence of a rash.1 Muscle disease may manifest with or precede the rash, but up to 40% of patients present with skin manifestations alone, an entity called amyopathic dermatomyositis.2 When present, the myositis generally develops over months, but the onset can be acute.1 The weakness is typically symmetrical and proximal,1 and many patients have oropharyngeal dysphagia.3

The characteristic rash is erythematous, symmetrical, and photodistributed.4 Classic cutaneous findings are the heliotrope rash (violaceous eyelid erythema), which is pathognomonic but uncommon, and the more common Gottron's papules (violaceous, slightly elevated papules and plaques on bony prominences and extensor surfaces, especially the knuckles).4 Other findings include periorbital edema, scalp dermatitis, poikiloderma (ie, hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, atrophy, and telangiectasia), periungual erythema, and dystrophic cuticles.2 The cutaneous manifestations of dermatomyositis may be similar to those of psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, lichen planus, rosacea, polymorphous light eruption, drug eruption, atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, or allergic contact dermatitis.4

Diagnosing dermatomyositis requires considering clinical, laboratory, electromyographical, and histological evidence, as there are no widely accepted, validated diagnostic criteria.1, 5 The diagnosis is usually suspected if there is a characteristic rash and symptoms of myositis (eg, proximal muscle weakness, myalgias, fatigue, or an inability to swallow). When the patient has an atypical rash, skin biopsy can differentiate dermatomyositis from other conditions, except lupus, which shares the key finding of interface dermatitis.2 The histological findings can be variable and subtle,6 so consultation with a dermatopathologist may be helpful.

Myositis may be confirmed by various studies. Most patients have elevated muscle enzymes (ie, creatinine kinase, aldolase, lactate dehydrogenase, or transaminases)1; for those who do not, magnetic resonance imaging can be helpful in detecting muscle involvement and locating the best site for muscle biopsy.7 Electromyography reveals nonspecific muscle membrane instability.8 Muscle biopsy shows muscle fiber necrosis, perifascicular atrophy, and perivascular and perifascicular lymphocytic infiltrates. These can be patchy, diminished by steroid use, and occasionally seen in noninflammatory muscular dystrophies.8 For a patient with typical myositis and a characteristic rash, muscle biopsy may be unnecessary.1

The clinical utility of serologic testing for diagnosing dermatomyositis is controversial.2 Myositis‐specific antibody testing is insensitive but specific; these antibodies include Jo‐1, an antisynthetase antibody that predicts incomplete response to therapy and lung involvement, and Mi‐2, which is associated with better response to therapy.2, 9, 10 The sensitivity and specificity of antinuclear antibodies are both approximately 60%.10

Patients with dermatomyositis have higher rates of cancers than age‐matched controls, and nearly 25% of patients are diagnosed with a malignancy at some point during the course of the disease.11 Malignancies are typically solid tumors that manifest within 3 years of the diagnosis,1214 although the increased risk may exist for at least 5 years.14 There is a 10‐fold higher risk of ovarian cancer in women with dermatomyositis.12, 15 Other associated malignancies include lung, gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, and breast carcinomas and non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma.14

Recommendations for screening affected patients for cancer have changed over the years, with increasing evidence of an association between dermatomyositis and malignancy and evolving improvements in diagnostic techniques.16 Many authorities recommend that all adult patients with dermatomyositis be evaluated for cancer, including a complete physical examination, basic hematological tests, age‐ and sex‐appropriate screening (eg, mammography, pap smear, and colonoscopy), and chest x‐ray.16 Some would add upper endoscopy; imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; gynecological examination; and serum CA‐125 level to better evaluate for the most common malignancies (ie, ovarian, gastric, lung, and pancreatic carcinomas and non‐Hodgkins lymphoma).12, 1720

In 19% of adults, dermatomyositis overlaps with other autoimmune disorders, usually systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis.21 These manifest as Raynaud's phenomenon, arthritis, esophageal dysmotility, renal disease, or neuropathy.21 Other potentially serious systemic manifestations of dermatomyositis include proximal dysphagia from pharyngeal myopathy; distal dysphagia from esophageal dysmotility in systemic sclerosis overlap; pulmonary disease from autoimmune interstitial lung disease or aspiration; cardiac disease from conduction abnormalities, myocarditis, pericarditis, and valvular disease; and rhabdomyolysis.2

Treatment of dermatomyositis requires systemic immunosuppression with 1 or more agents. The prognosis of dermatomyositis is variable. Mortality at 5 years ranges from 23% to 73%. At least a third of patients are left with mild to severe disability.1 In addition to older age, predictors of poor outcome include male sex, dysphagia, longstanding symptoms before treatment, pulmonary or cardiac involvement, and presence of antisynthetase antibodies.22

Dermatomyositis is often treated in the outpatient setting, but there are many reasons for hospitalization. Complications of treatment, like infection or adverse effects of medications, could result in hospitalization. Treatment with intravenous pulse corticosteroids or IVIG may require inpatient administration if no infusion center is available. Other indications for inpatient evaluation include the consequences of various malignancies and the more severe expression of systemic complications of dermatomyositis (eg, dysphagia and pulmonary, cardiac, or renal disease).

Every parent knows the plaintive backseat whine, Are we there, yet? Clinicians may also experience this feeling when attempting to diagnose a perplexing illness, especially one that lacks a definitive diagnostic test. It was easy for this patient's doctors to assume initially that his new rash was a manifestation of his long‐standing psoriasis. Having done so, they could understandably attribute the subsequent findings to either evolution of this disease or to consequences of the prescribed treatments, rather than considering a novel diagnosis. Only when faced with new (or newly appreciated) findings suggesting myopathy did the clinicians (and our discussant) consider the diagnosis of dermatomyositis. Even then, the primary inpatient medical team and their consultants were unsure when they had sufficient evidence to be certain.

Several factors compounded the difficulty of making a diagnosis in this case: the clinicians were dealing with a rare disease; they were considering alternative diagnoses (ie, psoriasis or a toxic effect of medication); and the disease presented somewhat atypically. The clinicians initially failed to consider and then accept the correct diagnosis because the patient's rash was not classic, his biopsy was interpreted as nonspecific, and he lacked myositis at presentation. Furthermore, when the generalists sought expert assistance, they encountered a difference of opinion among the consultants. These complex situations should goad the clinician into carefully considering the therapeutic threshold, that is, the transition point from diagnostic testing to therapeutic intervention.23 With complex cases like this, it may be difficult to know when one has reached a strongly supported diagnosis, and frequently asking whether we are there yet may be appropriate.

Take‐Home Points for the Hospitalist

-

A skin rash, which may have typical or atypical features, distinguishes dermatomyositis from other acquired myopathies.

-

Consider consultation with pathology specialists for skin and muscle biopsies.

-

Ovarian, lung, gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, and breast carcinomas and non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma are the most common cancers associated with dermatomyositis.

-

In addition to age‐appropriate cancer screening, consider obtaining upper endoscopy, imaging of the chest/abdomen/pelvis, and CA‐125.

-

Patients with dermatomyositis and no obvious concurrent malignancy need long‐term outpatient follow‐up for repeated malignancy screening.

A 62‐year‐old man with psoriasis for more than 30 years presented to the emergency department with a scaly, pruritic rash involving his face, trunk, and extremities that he had had for the past 10 days. The rash was spreading and not responding to application of clobetasol ointment, which had helped his psoriasis in the past. He also reported mild pharyngitis, headache, and myalgias.

A patient with a chronic skin condition presenting with a new rash means the clinician must consider whether it is an alternative manifestation of the chronic disorder or a new illness. Psoriasis takes many forms including guttate psoriasis, which presents with small, droplike plaques and frequently follows respiratory infections (particularly those caused by Streptococcus). Well‐controlled psoriasis rarely transforms after 3 decades, so I would consider other conditions. The tempo of illness makes certain life‐threatening syndromes, including Stevens‐Johnson, toxic shock, and purpura fulminans, unlikely. An allergic reaction, atopic dermatitis, or medication reaction is possible. Infections, either systemic (eg, syphilis) or dermatologic (eg, scabies), should be considered. Photosensitivity could involve the sun‐exposed areas, such as the extremities and face. Seborrheic dermatitis can cause scaling lesions of the face and trunk but not the extremities. Vasculitis merits consideration, but dependent regions are typically affected more than the head. Mycosis fungoides or a paraneoplastic phenomenon could cause a diffuse rash in this age group.

The patient had diabetes mellitus, hypertension, diverticulosis, and depression. Three months earlier he had undergone surgical drainage of a perirectal abscess. His usual medications were lovastatin, paroxetine, insulin, hydrochlorothiazide, and lisinopril. Three weeks previously he had completed a 10‐day course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for an upper respiratory infection. Otherwise, he was taking no new medications. He was allergic to penicillin. He denied substance abuse, recent travel, or risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. He worked as an automobile painter, lived with his wife, and had a pet dog.

Physical examination revealed a well‐appearing man with normal vital signs. His skin had well‐defined circumscribed pink plaques, mostly 1‐2 cm in size, with thick, silvery scales in the ears and on the dorsal and ventral arms and legs, chest, back, face, and scalp. There were no pustules or other signs of infection (Figs. 1and 2). The nails exhibited distal onycholysis, oil spots, and rare pits. His posterior pharynx was mildly erythematous. The results of cardiovascular, pulmonary, and abdominal examinations were normal.

Although other scaling skin conditions such as eczema, irritant dermatitis, or malignancy remain possible, his rash is most consistent with widespread psoriasis. I would consider immunological changes that may have caused a remarkably altered and more severe expression of his chronic disease, for example, recent steroid therapy or HIV infection. The company a rash keeps helps frame the differential diagnosis. Based on the patient's well appearance, the time course, his minimal systemic symptoms, and the appearance of the rash, my leading considerations are psoriasis or an allergic dermatitis. Cutaneous T‐cell malignancy, with its indolent and sometimes protean manifestations, remains possible in a patient of his age. I would now consult a dermatologist for 3 reasons: this patient has a chronic disease that I do not manage beyond basic treatments (eg, topical steroids), he has an undiagnosed illness with substantial dermatologic manifestations, and he may need a skin biopsy for definitive diagnosis.

The dermatology team diagnosed a guttate psoriasis flare, possibly associated with streptococcal pharyngitis. The differential diagnosis included secondary syphilis, although the team believed this was less likely. The dermatology team recommended obtaining a throat culture, streptozyme assay, and rapid plasma reagin and prescribed oral erythromycin and topical steroid ointment under a sauna suit.

I would follow his response to the prescribed steroid treatments. If the patient's course deviates from the dermatologists' expectations, I would request a skin biopsy and undertake further evaluations in search of an underlying systemic disease.

The patient followed up in the dermatology clinic 3 weeks later. His rash had worsened, and he had developed patchy alopecia and progressive edema of the face, ears, and eyes. He denied mouth or tongue swelling, difficulty breathing, or hives. The streptozyme assay was positive, but the other laboratory test results were negative.

The dermatology team diagnosed a severely inflammatory psoriasis flare and prescribed an oral retinoid, acitretin, and referred him for ultraviolet light therapy. He was unable to travel for phototherapy, and acitretin was discontinued after 1 week because of elevated serum transaminase levels. The dermatologists then prescribed oral cyclosporine.

The progression of disease despite standard treatment suggests a nonpsoriatic condition. Although medications could cause the abnormal liver tests, so could another underlying illness that involves the liver. An infiltrative disorder of the skin with hair follicle destruction and local lymphedema could explain both alopecia and facial edema.

I am unable account for his clinical features with a single disease, so the differential remains broad, including severe psoriasis, an infiltrating cutaneous malignancy, or a toxic exposure. Arsenic poisoning causes hyperkeratotic skin lesions, although he lacks the associated gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms. I would not have added the potentially toxic cyclosporine.

When he returned to dermatology clinic 1 week later, his rash and facial swelling had worsened. He also reported muscle and joint aches, fatigue, lightheadedness, anorexia, nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and dyspnea on exertion. He denied fever, chills, and night sweats.

He appeared ill and used a cane to arise and walk. His vital signs and oxygen saturation were normal. He had marked swelling of his face, diffuse erythema and swelling on the chest, and widespread scaly, erythematous plaques (Fig. 3). The proximal nail folds of his fingers were erythematous, with ragged cuticles. His abdomen was mildly distended, but the rest of the physical examination was normal.

He has become too systemically ill to attribute his condition to psoriasis. The nail findings suggest dermatomyositis, which could explain many of his findings. The diffuse erythema and his difficulty walking are consistent with its skin and muscle involvement. Dyspnea could be explained by dermatomyositis‐associated interstitial lung disease. A dermatomyositis‐associated hematological or solid malignancy could account for his multisystem ailments and functional decline. A point against dermatomyositis is the relatively explosive onset of his disease. He should be carefully examined for any motor weakness. With his progressive erythroderma, I am also concerned about an advancing cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma (with leukemic transformation).

Blood tests revealed the following values: white‐blood‐cell count, 8700/L; hematocrit, 46%; platelet count, 172,000/L; blood urea nitrogen, 26 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.0 mg/dL; glucose, 199 mg/dL; albumin, 3.1 g/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 172 U/L (normal range 45‐129); alanine aminotransferase, 75 U/L (normal range 0‐39 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 263 U/L (normal range 0‐37 U/L); total bilirubin, 1.1 mg/dL; prothrombin time, 16 seconds (normal range 11.7‐14.3 seconds), and serum creatinine, kinase, 4253 U/L (normal range 0‐194 U/L). HIV serology was negative. Urinalysis revealed trace protein. The results of chest radiographs and an electrocardiogram were normal.

The liver function tests results are consistent with medication effects or liver involvement in a systemic disease. The creatinine kinase elevation is consistent with a myopathy such as dermatomyositis. A skin biopsy would still be useful. Depending on those results, he may need a muscle biopsy, urine heavy metal testing, and computed tomography body imaging. Considering his transaminase and creatinine kinase elevations, I would discontinue lovastatin.

The patient was hospitalized. Further questioning revealed that he had typical Raynaud's phenomenon and odynophagia. A detailed neurological examination showed weakness (3/5) of the triceps and iliopsoas muscles and difficulty rising from a chair without using his arms. Dermatoscopic examination of the proximal nail folds showed dilated capillary loops and foci of hemorrhage.

Blood tests showed a lactate dehydrogenase level of 456 U/L (normal range 0‐249 U/L) and an aldolase of 38 U/L (normal range 1.2‐7.6 U/L). Tests for antinuclear antibodies, anti‐Jo antibody, and antimyeloperoxidase antibodies were negative. Two skin biopsies were interpreted by general pathology as consistent with partially treated psoriasis, whereas another showed nonspecific changes with minimal superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammation (Fig. 4). Lisinopril was discontinued because of its possible contribution to the facial edema.

Dermatomyositis is now the leading diagnosis. Characteristic features include his proximal muscle weakness, Raynaud's phenomenon, and dilated nailfold capillary loops. I am not overly dissuaded by the negative antinuclear antibodies, but because of additional atypical features (ie, extensive cutaneous edema, rapid onset, illness severity, prominent gastrointestinal symptoms), a confirmatory muscle biopsy is needed. Endoscopy of the proximal aerodigestive tract would help evaluate the odynophagia. There is little to suggest infection, malignancy, or metabolic derangement.

The inpatient medical team considered myositis related to retinoid or cyclosporine therapy. They discontinued cyclosporine and began systemic corticosteroid therapy. Within a few days, the patient's rash, muscle pain, and weakness improved, and the elevated transaminase and creatinine kinase levels decreased.

Dermatology recommended an evaluation for dermatomyositis‐associated malignancy, but the medicine team and rheumatology consultants, noting the lack of classic skin findings (heliotrope rash and Gottron's papules) and the uncharacteristically rapid onset and improvement of myositis, suggested delaying the evaluation until dermatomyositis was proven.

An immediate improvement in symptoms with steroids is nonspecific, often occurring in autoimmune, infectious, and neoplastic diseases. This juncture in the case is common in complex multisystem illnesses, where various consultants may arrive at differing conclusions. With both typical and atypical features of dermatomyositis, where should one set the therapeutic threshold, that is, the point where one ends testing, accepts a diagnosis, and initiates treatment? Several factors raise the level of certainty I would require. First, dermatomyositis is quite rare. Adding atypical features further increases the burden of proof for that illness. Second, the existence of alternative possibilities (admittedly of equal uncertainty) gives me some pause. Finally, the toxicity of the proposed treatments raises the therapeutic threshold. Acknowledging that empiric treatment may be indicated for a severely ill patient at a lower level of certainty, I would hesitate to commit a patient to long‐term steroids without being confident of the diagnosis. I would therefore require a muscle biopsy, or at least electromyography to support or exclude dermatomyositis.

The patient was discharged from the hospital on high‐dose prednisone. He underwent electromyography, which revealed inflammatory myopathic changes more apparent in the proximal than distal muscles. These findings were thought to be compatible with dermatomyositis, although the fibrillations and positive sharp waves characteristic of acute inflammation were absent, perhaps because of corticosteroid therapy.

The patient mistakenly stopped taking his prednisone. Within days, his weakness and skin rash worsened, and he developed nausea with vomiting. He returned to clinic, where his creatinine kinase level was again found to be elevated, and he was rehospitalized. Oral corticosteroid therapy was restarted with prompt improvement. On review of the original skin biopsies, a dermatopathologist observed areas of thickened dermal collagen and a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, both consistent with connective tissue disease.

These 3 additional findings (ie, electromyography results, temporally established steroid responsiveness, and the new skin biopsy interpretation) in aggregate support the diagnosis of dermatomyositis, but the nausea and vomiting are unusual. I would discuss these results with a rheumatologist and still request a confirmatory muscle biopsy. Because diagnosing dermatomyositis should prompt consideration of seeking an underlying malignancy in a patient of this age group, I would repeat a targeted history and physical examination along with age‐ and risk‐factor‐appropriate screening. If muscle biopsy results are not definitive, finding an underlying malignancy would lend support to dermatomyositis.

While hospitalized, the patient complained of continued odynophagia and was noted to have oral candidiasis. Upper endoscopy, undertaken to evaluate for esophageal candidiasis, revealed a mass at the gastroesophageal junction. Biopsy revealed gastric‐type adenocarcinoma. An abdominal computed tomography scan demonstrated 3 hypodense hepatic lesions, evidence of cirrhosis, and ascites. Cytology of paracentesis fluid revealed cells compatible with adenocarcinoma. The patient died in hospice care 2 weeks later.

At autopsy, he had metastatic gastric‐type adenocarcinoma. A muscle biopsy (Fig. 5) revealed muscle atrophy with small foci of lymphocytic infiltrates, most compatible with dermatomyositis. Another dermatopathologist reviewed the skin biopsies and noted interface dermatitis, which is typical of connective tissue diseases like dermatomyositis (Fig. 6A,B).

COMMENTARY

Dermatomyositis is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy characterized by endomysial inflammation and muscle weakness and differentiated from other myopathies by the presence of a rash.1 Muscle disease may manifest with or precede the rash, but up to 40% of patients present with skin manifestations alone, an entity called amyopathic dermatomyositis.2 When present, the myositis generally develops over months, but the onset can be acute.1 The weakness is typically symmetrical and proximal,1 and many patients have oropharyngeal dysphagia.3

The characteristic rash is erythematous, symmetrical, and photodistributed.4 Classic cutaneous findings are the heliotrope rash (violaceous eyelid erythema), which is pathognomonic but uncommon, and the more common Gottron's papules (violaceous, slightly elevated papules and plaques on bony prominences and extensor surfaces, especially the knuckles).4 Other findings include periorbital edema, scalp dermatitis, poikiloderma (ie, hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, atrophy, and telangiectasia), periungual erythema, and dystrophic cuticles.2 The cutaneous manifestations of dermatomyositis may be similar to those of psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, lichen planus, rosacea, polymorphous light eruption, drug eruption, atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, or allergic contact dermatitis.4

Diagnosing dermatomyositis requires considering clinical, laboratory, electromyographical, and histological evidence, as there are no widely accepted, validated diagnostic criteria.1, 5 The diagnosis is usually suspected if there is a characteristic rash and symptoms of myositis (eg, proximal muscle weakness, myalgias, fatigue, or an inability to swallow). When the patient has an atypical rash, skin biopsy can differentiate dermatomyositis from other conditions, except lupus, which shares the key finding of interface dermatitis.2 The histological findings can be variable and subtle,6 so consultation with a dermatopathologist may be helpful.

Myositis may be confirmed by various studies. Most patients have elevated muscle enzymes (ie, creatinine kinase, aldolase, lactate dehydrogenase, or transaminases)1; for those who do not, magnetic resonance imaging can be helpful in detecting muscle involvement and locating the best site for muscle biopsy.7 Electromyography reveals nonspecific muscle membrane instability.8 Muscle biopsy shows muscle fiber necrosis, perifascicular atrophy, and perivascular and perifascicular lymphocytic infiltrates. These can be patchy, diminished by steroid use, and occasionally seen in noninflammatory muscular dystrophies.8 For a patient with typical myositis and a characteristic rash, muscle biopsy may be unnecessary.1

The clinical utility of serologic testing for diagnosing dermatomyositis is controversial.2 Myositis‐specific antibody testing is insensitive but specific; these antibodies include Jo‐1, an antisynthetase antibody that predicts incomplete response to therapy and lung involvement, and Mi‐2, which is associated with better response to therapy.2, 9, 10 The sensitivity and specificity of antinuclear antibodies are both approximately 60%.10

Patients with dermatomyositis have higher rates of cancers than age‐matched controls, and nearly 25% of patients are diagnosed with a malignancy at some point during the course of the disease.11 Malignancies are typically solid tumors that manifest within 3 years of the diagnosis,1214 although the increased risk may exist for at least 5 years.14 There is a 10‐fold higher risk of ovarian cancer in women with dermatomyositis.12, 15 Other associated malignancies include lung, gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, and breast carcinomas and non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma.14

Recommendations for screening affected patients for cancer have changed over the years, with increasing evidence of an association between dermatomyositis and malignancy and evolving improvements in diagnostic techniques.16 Many authorities recommend that all adult patients with dermatomyositis be evaluated for cancer, including a complete physical examination, basic hematological tests, age‐ and sex‐appropriate screening (eg, mammography, pap smear, and colonoscopy), and chest x‐ray.16 Some would add upper endoscopy; imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; gynecological examination; and serum CA‐125 level to better evaluate for the most common malignancies (ie, ovarian, gastric, lung, and pancreatic carcinomas and non‐Hodgkins lymphoma).12, 1720

In 19% of adults, dermatomyositis overlaps with other autoimmune disorders, usually systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis.21 These manifest as Raynaud's phenomenon, arthritis, esophageal dysmotility, renal disease, or neuropathy.21 Other potentially serious systemic manifestations of dermatomyositis include proximal dysphagia from pharyngeal myopathy; distal dysphagia from esophageal dysmotility in systemic sclerosis overlap; pulmonary disease from autoimmune interstitial lung disease or aspiration; cardiac disease from conduction abnormalities, myocarditis, pericarditis, and valvular disease; and rhabdomyolysis.2

Treatment of dermatomyositis requires systemic immunosuppression with 1 or more agents. The prognosis of dermatomyositis is variable. Mortality at 5 years ranges from 23% to 73%. At least a third of patients are left with mild to severe disability.1 In addition to older age, predictors of poor outcome include male sex, dysphagia, longstanding symptoms before treatment, pulmonary or cardiac involvement, and presence of antisynthetase antibodies.22

Dermatomyositis is often treated in the outpatient setting, but there are many reasons for hospitalization. Complications of treatment, like infection or adverse effects of medications, could result in hospitalization. Treatment with intravenous pulse corticosteroids or IVIG may require inpatient administration if no infusion center is available. Other indications for inpatient evaluation include the consequences of various malignancies and the more severe expression of systemic complications of dermatomyositis (eg, dysphagia and pulmonary, cardiac, or renal disease).

Every parent knows the plaintive backseat whine, Are we there, yet? Clinicians may also experience this feeling when attempting to diagnose a perplexing illness, especially one that lacks a definitive diagnostic test. It was easy for this patient's doctors to assume initially that his new rash was a manifestation of his long‐standing psoriasis. Having done so, they could understandably attribute the subsequent findings to either evolution of this disease or to consequences of the prescribed treatments, rather than considering a novel diagnosis. Only when faced with new (or newly appreciated) findings suggesting myopathy did the clinicians (and our discussant) consider the diagnosis of dermatomyositis. Even then, the primary inpatient medical team and their consultants were unsure when they had sufficient evidence to be certain.

Several factors compounded the difficulty of making a diagnosis in this case: the clinicians were dealing with a rare disease; they were considering alternative diagnoses (ie, psoriasis or a toxic effect of medication); and the disease presented somewhat atypically. The clinicians initially failed to consider and then accept the correct diagnosis because the patient's rash was not classic, his biopsy was interpreted as nonspecific, and he lacked myositis at presentation. Furthermore, when the generalists sought expert assistance, they encountered a difference of opinion among the consultants. These complex situations should goad the clinician into carefully considering the therapeutic threshold, that is, the transition point from diagnostic testing to therapeutic intervention.23 With complex cases like this, it may be difficult to know when one has reached a strongly supported diagnosis, and frequently asking whether we are there yet may be appropriate.

Take‐Home Points for the Hospitalist

-

A skin rash, which may have typical or atypical features, distinguishes dermatomyositis from other acquired myopathies.

-

Consider consultation with pathology specialists for skin and muscle biopsies.

-

Ovarian, lung, gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, and breast carcinomas and non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma are the most common cancers associated with dermatomyositis.

-

In addition to age‐appropriate cancer screening, consider obtaining upper endoscopy, imaging of the chest/abdomen/pelvis, and CA‐125.

-

Patients with dermatomyositis and no obvious concurrent malignancy need long‐term outpatient follow‐up for repeated malignancy screening.

- ,.Polymyositis and dermatomyositis.Lancet.2003;362:971–982.

- .Dermatomyositis.Lancet.2000;355:53–47.

- ,,,.Oropharyngeal dysphagia in polymyositis/dermatomyositis.Clin Neurol Neurosurg.2004;107(1):32–37.

- ,.Skin involvement in dermatomyositis.Curr Opin Rheumatol.2003;15:714–22.

- ,,,,,.Novel classification of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies based on overlap syndrome features and autoantibodies: analysis of 100 French Canadian patients.Medicine (Baltimore).2005;84:231–249.

- .Skin Pathology.2nd ed.New York:Churchill Livingstone;2002.

- ,.Utility of magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of patients with inflammatory myopathies.Curr Rheumatol Rep.2001;3:334–245.

- ,,.Is it really myositis? A consideration of the differential diagnosis.Curr Opin Rheumatol2004;16:684–691.

- .Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: autoantibody update.Curr Rheumatol Rep.2002;4:434–441.

- ,,.Laboratory assessment in musculoskeletal disorders.Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol.2003;17:475–494.

- ,.Dermatomyositis.Clin Dermatol.2006;24:363–373.

- ,,, et al.Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population‐based study.Lancet.2001;357:96–100.

- ,,, et al.Cancer‐associated myositis: clinical features and prognostic signs.Ann N Y Acad Sci.2005;1051:64–71.

- ,,,,.Incidence of malignant disease in biopsy‐proven inflammatory myopathy. A population‐based cohort study.Ann Intern Med.2001;134:1087–1095.

- ,,.Risk of cancer in patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis, and follow‐up implications: a Scottish population‐based cohort study.Br J Cancer.2001;85 (1):41–45.

- .When and how should the patient with dermatomyositis or amyopathic dermatomyositis be assessed for possible cancer?Arch Dermatol.2002;138:969–971.

- ,,.Ovarian cancer in patients with dermatomyositis.Medicine (Baltimore).1994;73(3):153–160.

- ,,,.Dermatomyositis sine myositis: association with malignancy.J Rheumatol.1996;23 (1):101–105.

- ,,, et al.Tumor antigen markers for the detection of solid cancers in inflammatory myopathies.Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev.2005;14:1279–1282.

- ,,, et al.Routine vs extensive malignancy search for adult dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a study of 40 patients.Arch Dermatol.2002;138:885–890.

- ,,,,,.Dermatomyositis: a dermatology‐based case series.J Am Acad Dermatol.1998;38:397–404.

- ,,, et al.Long‐term outcome in polymyositis and dermatomyositis.Ann Rheum Dis.2006;65:1456–1461.

- .Our stubborn quest for diagnostic certainty. A cause of excessive testing.N Engl J Med.1989;320:1489–1491.

- ,.Polymyositis and dermatomyositis.Lancet.2003;362:971–982.

- .Dermatomyositis.Lancet.2000;355:53–47.

- ,,,.Oropharyngeal dysphagia in polymyositis/dermatomyositis.Clin Neurol Neurosurg.2004;107(1):32–37.

- ,.Skin involvement in dermatomyositis.Curr Opin Rheumatol.2003;15:714–22.

- ,,,,,.Novel classification of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies based on overlap syndrome features and autoantibodies: analysis of 100 French Canadian patients.Medicine (Baltimore).2005;84:231–249.

- .Skin Pathology.2nd ed.New York:Churchill Livingstone;2002.

- ,.Utility of magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of patients with inflammatory myopathies.Curr Rheumatol Rep.2001;3:334–245.

- ,,.Is it really myositis? A consideration of the differential diagnosis.Curr Opin Rheumatol2004;16:684–691.

- .Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: autoantibody update.Curr Rheumatol Rep.2002;4:434–441.

- ,,.Laboratory assessment in musculoskeletal disorders.Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol.2003;17:475–494.

- ,.Dermatomyositis.Clin Dermatol.2006;24:363–373.

- ,,, et al.Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population‐based study.Lancet.2001;357:96–100.

- ,,, et al.Cancer‐associated myositis: clinical features and prognostic signs.Ann N Y Acad Sci.2005;1051:64–71.

- ,,,,.Incidence of malignant disease in biopsy‐proven inflammatory myopathy. A population‐based cohort study.Ann Intern Med.2001;134:1087–1095.

- ,,.Risk of cancer in patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis, and follow‐up implications: a Scottish population‐based cohort study.Br J Cancer.2001;85 (1):41–45.

- .When and how should the patient with dermatomyositis or amyopathic dermatomyositis be assessed for possible cancer?Arch Dermatol.2002;138:969–971.

- ,,.Ovarian cancer in patients with dermatomyositis.Medicine (Baltimore).1994;73(3):153–160.

- ,,,.Dermatomyositis sine myositis: association with malignancy.J Rheumatol.1996;23 (1):101–105.

- ,,, et al.Tumor antigen markers for the detection of solid cancers in inflammatory myopathies.Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev.2005;14:1279–1282.

- ,,, et al.Routine vs extensive malignancy search for adult dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a study of 40 patients.Arch Dermatol.2002;138:885–890.

- ,,,,,.Dermatomyositis: a dermatology‐based case series.J Am Acad Dermatol.1998;38:397–404.

- ,,, et al.Long‐term outcome in polymyositis and dermatomyositis.Ann Rheum Dis.2006;65:1456–1461.

- .Our stubborn quest for diagnostic certainty. A cause of excessive testing.N Engl J Med.1989;320:1489–1491.

Clinical Conundrum

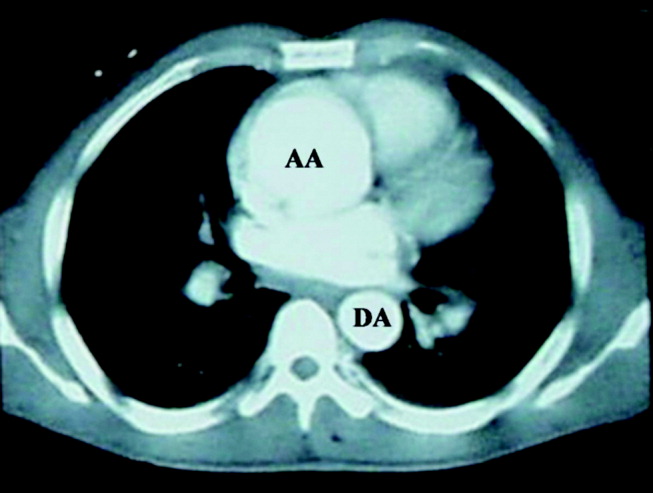

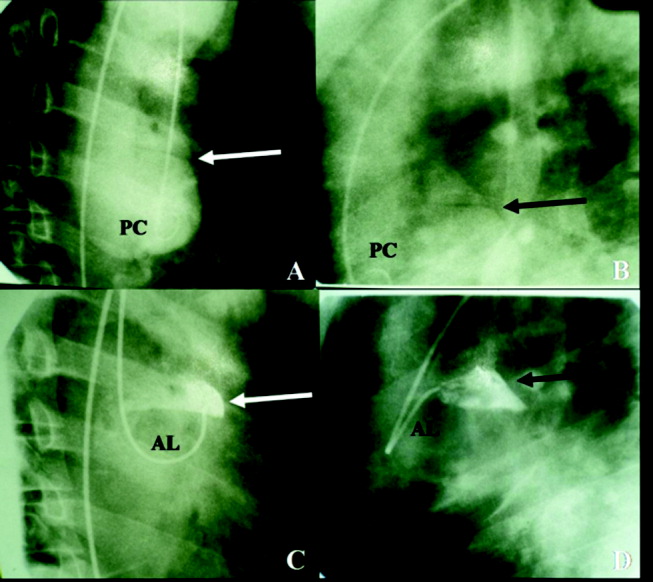

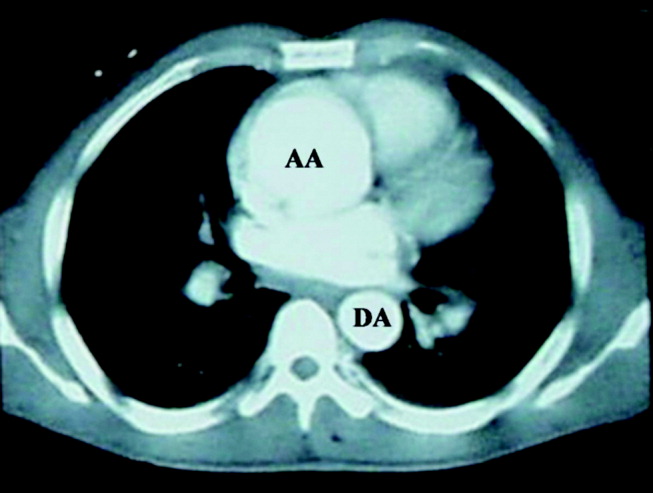

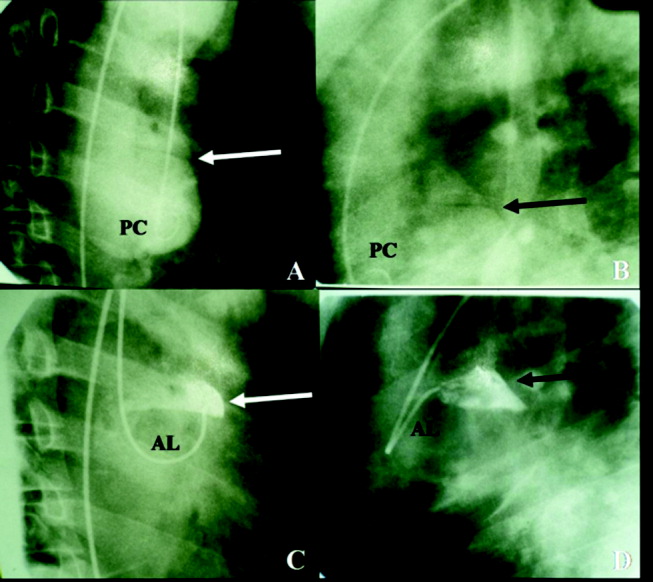

A 56‐year‐old woman from Colombia presented to the emergency department after 24 hours of abdominal pain. One week before, she had experienced similar pain that lasted for 4 hours and spontaneously resolved. She was nauseated but had no vomiting. She reported an unintentional 14‐pound weight loss over the preceding 3 weeks. She denied fever, chills, night sweats, diarrhea, constipation, dysuria, or jaundice.

In a middle‐aged woman with abdominal pain and nausea, diagnostic considerations include gallbladder disease, diseases of the bowel (such as a partial small‐bowel obstruction or inflammatory conditions), hepatic or pancreatic conditions, and nongastrointestinal ailments such as cardiac ischemia. Knowing the specific location of pain, its quality, precipitating factors, and accompanying systemic symptoms may help to narrow the diagnosis. The unintentional weight loss preceding the onset of pain may be an important clue because it suggests a systemic condition, and in a South American immigrantparticularly if she has traveled recentlyit is important to consider parasitic illnesses. The absence of fever makes some infections such as tuberculosis and malaria less likely. At this point, in addition to a thorough history and physical, laboratory tests should include a complete blood count (with quantification of eosinophils) and a metabolic panel with liver enzymes and albumin.

The patient described pain in the midline, just inferior to the umbilicus. The pain was constant, developed without any particular provocation, and was not related to meals or exertion. There were no constitutional symptoms aside from weight loss. She had a history of bipolar disorder, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, and chronic sinusitis and had previously undergone cholecystectomy and abdominal hysterectomy. She was taking levothyroxine, montelukast, bupropion, oxcarbazepine, fexofenadine, meloxicam, zolpidem, and, as needed, acetaminophen. She had recently completed a 10‐day course of levofloxacin for acute sinusitis. She had immigrated to the United States 10 years earlier and lived with her husband and daughter. She denied the use of tobacco, alcohol or illicit drugs. She had visited Colombia 6 months earlier but had no other recent travel history.