User login

Man Continually Cuts Facial Lesion While Shaving

ANSWER

The best answer is to send the slides to a dermatopathologist (choice “a”), for reasons that will become clear in the discussion. It is true that by re-excising with margins (choice “b”), the lesion would certainly be gone, but that does nothing to address the potential pathologic implications of some of the items in the differential diagnosis for this type of lesion.

The same could be said for rechecking the lesion periodically (choice “c”), which would otherwise be an intelligent option. It is almost never wrong to consult with a supervising/collaborating physician (choice “d”), but that does not relieve the PA/NP of the ultimate responsibility for resolving the dilemma.

DISCUSSION

Odd little papules in the nasolabial fold can have implications far beyond the usual “benign versus malignant” issue. With its surface devoid of adnexal structures, and firm feel, this lesion was a bit suspicious, history of stability notwithstanding.

Generally termed skin adnexal tumors (SATs), these lesions are derived from local adnexal structures, such as eccrine or apocrine sweat glands or pilosebaceous unit tissue. But they may originate from pluripotent stem cells located in the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, residing in an area called “the bulge.”

Their final designation is based on the predominant cell type seen on pathology, but differentiation can be difficult, even for experienced pathologists. Many benign types have been described, but for every benign category, a malignant counterpart exists. The latter tend to be aggressive and involve nodes, metastasis, and generally poor outcomes.

Heredity, skin type, and UV exposure play significant roles in some types of skin cancer, but an intracellular signaling pathway is also thought to determine the ultimate differentiation of these cells. Loss of inhibition of this pathway, which normally occurs, is apparently the main deciding factor in malignant transformation.

But the importance of a precise diagnosis for an SAT is more than mere benign versus malignant considerations. These lesions can serve as markers for syndromes associated with internal malignancies, such as Cowden’s disease (trichilemmomas) or Muir-Torre syndrome (sebaceous neoplasm), to name just two.

The person most likely to be able to discriminate between these various possibilities is the dermatopathologist, who is not only an expert in what is seen microscopically, but is also typically a practicing dermatologist who regularly sees the conditions he diagnoses. The biopsying provider has an obligation to insist on a crystal-clear diagnosis, when it can be obtained. And that “diagnosis” isn’t always about what the lesion is. Sometimes it’s as much about what the lesion means.

SUGGESTED READING

Alsaad KO, Obaidat NA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms—part 1: an approach to tumours of the pilosebaceous unit. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(2):129-144.

ANSWER

The best answer is to send the slides to a dermatopathologist (choice “a”), for reasons that will become clear in the discussion. It is true that by re-excising with margins (choice “b”), the lesion would certainly be gone, but that does nothing to address the potential pathologic implications of some of the items in the differential diagnosis for this type of lesion.

The same could be said for rechecking the lesion periodically (choice “c”), which would otherwise be an intelligent option. It is almost never wrong to consult with a supervising/collaborating physician (choice “d”), but that does not relieve the PA/NP of the ultimate responsibility for resolving the dilemma.

DISCUSSION

Odd little papules in the nasolabial fold can have implications far beyond the usual “benign versus malignant” issue. With its surface devoid of adnexal structures, and firm feel, this lesion was a bit suspicious, history of stability notwithstanding.

Generally termed skin adnexal tumors (SATs), these lesions are derived from local adnexal structures, such as eccrine or apocrine sweat glands or pilosebaceous unit tissue. But they may originate from pluripotent stem cells located in the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, residing in an area called “the bulge.”

Their final designation is based on the predominant cell type seen on pathology, but differentiation can be difficult, even for experienced pathologists. Many benign types have been described, but for every benign category, a malignant counterpart exists. The latter tend to be aggressive and involve nodes, metastasis, and generally poor outcomes.

Heredity, skin type, and UV exposure play significant roles in some types of skin cancer, but an intracellular signaling pathway is also thought to determine the ultimate differentiation of these cells. Loss of inhibition of this pathway, which normally occurs, is apparently the main deciding factor in malignant transformation.

But the importance of a precise diagnosis for an SAT is more than mere benign versus malignant considerations. These lesions can serve as markers for syndromes associated with internal malignancies, such as Cowden’s disease (trichilemmomas) or Muir-Torre syndrome (sebaceous neoplasm), to name just two.

The person most likely to be able to discriminate between these various possibilities is the dermatopathologist, who is not only an expert in what is seen microscopically, but is also typically a practicing dermatologist who regularly sees the conditions he diagnoses. The biopsying provider has an obligation to insist on a crystal-clear diagnosis, when it can be obtained. And that “diagnosis” isn’t always about what the lesion is. Sometimes it’s as much about what the lesion means.

SUGGESTED READING

Alsaad KO, Obaidat NA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms—part 1: an approach to tumours of the pilosebaceous unit. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(2):129-144.

ANSWER

The best answer is to send the slides to a dermatopathologist (choice “a”), for reasons that will become clear in the discussion. It is true that by re-excising with margins (choice “b”), the lesion would certainly be gone, but that does nothing to address the potential pathologic implications of some of the items in the differential diagnosis for this type of lesion.

The same could be said for rechecking the lesion periodically (choice “c”), which would otherwise be an intelligent option. It is almost never wrong to consult with a supervising/collaborating physician (choice “d”), but that does not relieve the PA/NP of the ultimate responsibility for resolving the dilemma.

DISCUSSION

Odd little papules in the nasolabial fold can have implications far beyond the usual “benign versus malignant” issue. With its surface devoid of adnexal structures, and firm feel, this lesion was a bit suspicious, history of stability notwithstanding.

Generally termed skin adnexal tumors (SATs), these lesions are derived from local adnexal structures, such as eccrine or apocrine sweat glands or pilosebaceous unit tissue. But they may originate from pluripotent stem cells located in the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, residing in an area called “the bulge.”

Their final designation is based on the predominant cell type seen on pathology, but differentiation can be difficult, even for experienced pathologists. Many benign types have been described, but for every benign category, a malignant counterpart exists. The latter tend to be aggressive and involve nodes, metastasis, and generally poor outcomes.

Heredity, skin type, and UV exposure play significant roles in some types of skin cancer, but an intracellular signaling pathway is also thought to determine the ultimate differentiation of these cells. Loss of inhibition of this pathway, which normally occurs, is apparently the main deciding factor in malignant transformation.

But the importance of a precise diagnosis for an SAT is more than mere benign versus malignant considerations. These lesions can serve as markers for syndromes associated with internal malignancies, such as Cowden’s disease (trichilemmomas) or Muir-Torre syndrome (sebaceous neoplasm), to name just two.

The person most likely to be able to discriminate between these various possibilities is the dermatopathologist, who is not only an expert in what is seen microscopically, but is also typically a practicing dermatologist who regularly sees the conditions he diagnoses. The biopsying provider has an obligation to insist on a crystal-clear diagnosis, when it can be obtained. And that “diagnosis” isn’t always about what the lesion is. Sometimes it’s as much about what the lesion means.

SUGGESTED READING

Alsaad KO, Obaidat NA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms—part 1: an approach to tumours of the pilosebaceous unit. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(2):129-144.

A 53-year-old man self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of a lesion on his left maxilla that has been basically unchanged for several years. He is concerned for two reasons: First, it is a rare day on which he fails to cut the lesion while shaving, and he is afraid this repeated trauma will “turn it into skin cancer.” Second, a co-worker who recently had a basal cell carcinoma diagnosed in the same location constantly asks the patient when he is “going to see someone about that lesion.” Additional history taking reveals that the patient has had little sun exposure in his life. He is otherwise healthy. Examination of the lesion shows a nevoid pink 6-mm intradermal nodule in the lower left nasolabial/upper maxillary area. Closer inspection reveals that the surface of the lesion is totally smooth and devoid of adnexae (pores, hairs). On palpation, the lesion is notably firmer than expected. The lesion has a slightly translucent appearance, almost as if light could pass through it. In light of the recurring trauma caused by shaving, and at his co-worker’s urging, the patient decides to have the lesion excised. The lesion is sent for pathologic examination, in this case by a general dermatologist from a laboratory of his insurance provider’s choosing. Calling the lesion a desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, the general pathologist nonetheless expressed his uncertainty, advising “clinical correlation.”

How Should This Young Girl Be Diagnosed?

ANSWER

The correct answer is test treatment with liquid nitrogen (choice “c”), which would elicit the pathognomic umbilication seen in most molluscum papules. Cultures for bacteria or viruses (choice “a” or “b”) would not help, since this is not a bacterial condition and since the poxvirus is difficult to grow in culture. Punch or shave biopsy (choice “d”) would establish the diagnosis and is occasionally necessary, but it is not called for in this case.

DISCUSSION

This combination of molluscum papules, which occasionally become inflamed and pustular, and underlying eczematous changes is quite common. It has been called “eczematized molluscum.”

The antecubital distribution and personal and family history of atopy should put the provider on notice immediately. The diagnosis usually can be made on empiric grounds, without the diagnostic liquid nitrogen or biopsy. But when in doubt, confirmation is quick and easy.

The majority of molluscum patients will be atopic or will have parents or siblings who are. Patients with atopy are notoriously susceptible to skin infections, especially from viral organisms.

Most children with molluscum will acquire immunity within a few months, with or without treatment. But it is arguably sensible to treat a few lesions with topical preparations such as cantharidin, a blistering agent that destroys the treated lesions and may prompt the immune system to destroy the rest.

As with molluscum’s cousin, the wart, many different treatments for removing the papules have been tried, including destructive modalities such as liquid nitrogen. All have drawbacks, such as pain and blistering.

With this combination of atopy and warts or molluscum, a healthy dose of patient (or, more importantly, parent!) education is essential before treatment is attempted, since parents of these patients are often confused and worried. Parents and providers are often frightened by the occasional red, pustular molluscum. However, only rarely does this represent secondary bacterial infection.

ANSWER

The correct answer is test treatment with liquid nitrogen (choice “c”), which would elicit the pathognomic umbilication seen in most molluscum papules. Cultures for bacteria or viruses (choice “a” or “b”) would not help, since this is not a bacterial condition and since the poxvirus is difficult to grow in culture. Punch or shave biopsy (choice “d”) would establish the diagnosis and is occasionally necessary, but it is not called for in this case.

DISCUSSION

This combination of molluscum papules, which occasionally become inflamed and pustular, and underlying eczematous changes is quite common. It has been called “eczematized molluscum.”

The antecubital distribution and personal and family history of atopy should put the provider on notice immediately. The diagnosis usually can be made on empiric grounds, without the diagnostic liquid nitrogen or biopsy. But when in doubt, confirmation is quick and easy.

The majority of molluscum patients will be atopic or will have parents or siblings who are. Patients with atopy are notoriously susceptible to skin infections, especially from viral organisms.

Most children with molluscum will acquire immunity within a few months, with or without treatment. But it is arguably sensible to treat a few lesions with topical preparations such as cantharidin, a blistering agent that destroys the treated lesions and may prompt the immune system to destroy the rest.

As with molluscum’s cousin, the wart, many different treatments for removing the papules have been tried, including destructive modalities such as liquid nitrogen. All have drawbacks, such as pain and blistering.

With this combination of atopy and warts or molluscum, a healthy dose of patient (or, more importantly, parent!) education is essential before treatment is attempted, since parents of these patients are often confused and worried. Parents and providers are often frightened by the occasional red, pustular molluscum. However, only rarely does this represent secondary bacterial infection.

ANSWER

The correct answer is test treatment with liquid nitrogen (choice “c”), which would elicit the pathognomic umbilication seen in most molluscum papules. Cultures for bacteria or viruses (choice “a” or “b”) would not help, since this is not a bacterial condition and since the poxvirus is difficult to grow in culture. Punch or shave biopsy (choice “d”) would establish the diagnosis and is occasionally necessary, but it is not called for in this case.

DISCUSSION

This combination of molluscum papules, which occasionally become inflamed and pustular, and underlying eczematous changes is quite common. It has been called “eczematized molluscum.”

The antecubital distribution and personal and family history of atopy should put the provider on notice immediately. The diagnosis usually can be made on empiric grounds, without the diagnostic liquid nitrogen or biopsy. But when in doubt, confirmation is quick and easy.

The majority of molluscum patients will be atopic or will have parents or siblings who are. Patients with atopy are notoriously susceptible to skin infections, especially from viral organisms.

Most children with molluscum will acquire immunity within a few months, with or without treatment. But it is arguably sensible to treat a few lesions with topical preparations such as cantharidin, a blistering agent that destroys the treated lesions and may prompt the immune system to destroy the rest.

As with molluscum’s cousin, the wart, many different treatments for removing the papules have been tried, including destructive modalities such as liquid nitrogen. All have drawbacks, such as pain and blistering.

With this combination of atopy and warts or molluscum, a healthy dose of patient (or, more importantly, parent!) education is essential before treatment is attempted, since parents of these patients are often confused and worried. Parents and providers are often frightened by the occasional red, pustular molluscum. However, only rarely does this represent secondary bacterial infection.

A 6-year-old girl has been seen by at least three providers, each of whom offered a different diagnosis for the dermatologic changes to her arm (staph infection, warts, and dermatitis). None of the prescribed treatments for these conditions—a 10-day course of cephalexin; salicylic acid; and hydrocortisone cream, respectively—have resolved the problem. Therefore, her mother brings the child to dermatology. Further questioning reveals a marked history of atopy, characterized by seasonal allergies, occasional hives, and asthma. Both parents experienced these same problems as children. Examination reveals a 5-cm ill-defined collection of firm 2- to 4-mm papules covering the bilateral antecubital areas. These are superimposed on a background of slightly erythematous, slightly scaly skin. A total of three angry-looking pustules are interspersed among the smaller shiny, firm papules.

30-Year Rash that Flares in the Summertime

ANSWER

The correct answer is tinea pedis (choice “a”) of the moccasin variety (see “Discussion”). Contact dermatitis (choice “b”) is highly unlikely, given the lack of symptoms, the absence of vesiculation, and the duration of the problem. Unna-Thost syndrome (choice “c”) manifests with, among other things, plantar hyperkeratosis that is thick and fissured and looks like exaggerated callous formation. Plantar psoriasis (choice “d”) waxes and wanes and is seldom relegated to the sides of the feet. And while it is possible for psoriasis to affect only one area of the body (scalp, nails, or elbows), it is far more common for it to be seen in multiple areas, particularly in cases with a long duration, such as this one.

DISCUSSION

There are three common types of tinea pedis (dermatophytosis of the foot), but the moccasin variety (also called chronic hyperkeratotic type) is by far the most common and probably the least known. The classic interdigital type, with maceration and inflammation between either the fourth and fifth or third and fourth toes, is better known and therefore easier to diagnose. The third type of tinea pedis is inflammatory and typically presents with the sudden appearance of discrete vesicles and pustules on the non–weight-bearing portion of the sole; it is quite pruritic.

Given the appearance and complete lack of symptoms, moccasin-variety tinea pedis often goes unnoticed by the patient, or is written off as mere “dry skin” until a flare (usually in the summer) brings it back to mind. Patients often have a family history of similar problems; in this case, the patient’s mother was affected.

The KOH prep was positive in this case, showing numerous fungal elements that probably represented Trichophyton rubrum. This common dermatophyte also causes jock itch and onychomycosis, among other conditions. Fortunately, it is sensitive to most of the allylamines (eg, terbinafine) and imidazoles (eg, econazole or oxiconazole) in topical form.

Although the use of these medications can lead to marked improvement, a cure is most unlikely. Patients with this type of tinea pedis are probably susceptible to this “infection” and cannot avoid repeated re-exposure to the organism, which will be present in great numbers in their environment (shoes, socks, bedding, carpet).

After a thorough discussion of the diagnosis and prognosis, this patient was initially treated with OTC terbinafine cream, applied twice daily. Within two weeks, the frequency of application can be reduced to once or twice per week, especially during colder months; this should be sufficient to control the condition.

Of note, none of this woman’s immediate family has contracted tinea pedis, despite many years of exposure. This demonstrates the principle that susceptibility is probably more important than exposure.

ANSWER

The correct answer is tinea pedis (choice “a”) of the moccasin variety (see “Discussion”). Contact dermatitis (choice “b”) is highly unlikely, given the lack of symptoms, the absence of vesiculation, and the duration of the problem. Unna-Thost syndrome (choice “c”) manifests with, among other things, plantar hyperkeratosis that is thick and fissured and looks like exaggerated callous formation. Plantar psoriasis (choice “d”) waxes and wanes and is seldom relegated to the sides of the feet. And while it is possible for psoriasis to affect only one area of the body (scalp, nails, or elbows), it is far more common for it to be seen in multiple areas, particularly in cases with a long duration, such as this one.

DISCUSSION

There are three common types of tinea pedis (dermatophytosis of the foot), but the moccasin variety (also called chronic hyperkeratotic type) is by far the most common and probably the least known. The classic interdigital type, with maceration and inflammation between either the fourth and fifth or third and fourth toes, is better known and therefore easier to diagnose. The third type of tinea pedis is inflammatory and typically presents with the sudden appearance of discrete vesicles and pustules on the non–weight-bearing portion of the sole; it is quite pruritic.

Given the appearance and complete lack of symptoms, moccasin-variety tinea pedis often goes unnoticed by the patient, or is written off as mere “dry skin” until a flare (usually in the summer) brings it back to mind. Patients often have a family history of similar problems; in this case, the patient’s mother was affected.

The KOH prep was positive in this case, showing numerous fungal elements that probably represented Trichophyton rubrum. This common dermatophyte also causes jock itch and onychomycosis, among other conditions. Fortunately, it is sensitive to most of the allylamines (eg, terbinafine) and imidazoles (eg, econazole or oxiconazole) in topical form.

Although the use of these medications can lead to marked improvement, a cure is most unlikely. Patients with this type of tinea pedis are probably susceptible to this “infection” and cannot avoid repeated re-exposure to the organism, which will be present in great numbers in their environment (shoes, socks, bedding, carpet).

After a thorough discussion of the diagnosis and prognosis, this patient was initially treated with OTC terbinafine cream, applied twice daily. Within two weeks, the frequency of application can be reduced to once or twice per week, especially during colder months; this should be sufficient to control the condition.

Of note, none of this woman’s immediate family has contracted tinea pedis, despite many years of exposure. This demonstrates the principle that susceptibility is probably more important than exposure.

ANSWER

The correct answer is tinea pedis (choice “a”) of the moccasin variety (see “Discussion”). Contact dermatitis (choice “b”) is highly unlikely, given the lack of symptoms, the absence of vesiculation, and the duration of the problem. Unna-Thost syndrome (choice “c”) manifests with, among other things, plantar hyperkeratosis that is thick and fissured and looks like exaggerated callous formation. Plantar psoriasis (choice “d”) waxes and wanes and is seldom relegated to the sides of the feet. And while it is possible for psoriasis to affect only one area of the body (scalp, nails, or elbows), it is far more common for it to be seen in multiple areas, particularly in cases with a long duration, such as this one.

DISCUSSION

There are three common types of tinea pedis (dermatophytosis of the foot), but the moccasin variety (also called chronic hyperkeratotic type) is by far the most common and probably the least known. The classic interdigital type, with maceration and inflammation between either the fourth and fifth or third and fourth toes, is better known and therefore easier to diagnose. The third type of tinea pedis is inflammatory and typically presents with the sudden appearance of discrete vesicles and pustules on the non–weight-bearing portion of the sole; it is quite pruritic.

Given the appearance and complete lack of symptoms, moccasin-variety tinea pedis often goes unnoticed by the patient, or is written off as mere “dry skin” until a flare (usually in the summer) brings it back to mind. Patients often have a family history of similar problems; in this case, the patient’s mother was affected.

The KOH prep was positive in this case, showing numerous fungal elements that probably represented Trichophyton rubrum. This common dermatophyte also causes jock itch and onychomycosis, among other conditions. Fortunately, it is sensitive to most of the allylamines (eg, terbinafine) and imidazoles (eg, econazole or oxiconazole) in topical form.

Although the use of these medications can lead to marked improvement, a cure is most unlikely. Patients with this type of tinea pedis are probably susceptible to this “infection” and cannot avoid repeated re-exposure to the organism, which will be present in great numbers in their environment (shoes, socks, bedding, carpet).

After a thorough discussion of the diagnosis and prognosis, this patient was initially treated with OTC terbinafine cream, applied twice daily. Within two weeks, the frequency of application can be reduced to once or twice per week, especially during colder months; this should be sufficient to control the condition.

Of note, none of this woman’s immediate family has contracted tinea pedis, despite many years of exposure. This demonstrates the principle that susceptibility is probably more important than exposure.

A 53-year-old woman presents with a 30-year history of an asymptomatic rash on both feet. According to the patient, her mother had a similar condition. Over the years, the patient has tried any number of OTC moisturizers, thinking the rash was just dry skin that always worsened in the summertime. She has mentioned it to several medical providers, none of whom had any useful ideas about what it is or what to do about it. The patient claims to be otherwise healthy. She is not immunosuppressed and is taking no prescription medications. She further denies a personal or family history of any other skin problems. Examination reveals extensive marked desquamation of the sides of both feet. The scaling is quite fine and slightly erythematous. The well-demarcated annular proximal borders stop abruptly about halfway up the heel, involving the medial aspects of both big toes and the lateral aspects of both fifth toes. There is no involvement or maceration in the interdigital areas, and both soles are completely spared. Her skin elsewhere—including elbows, knees, nails, and scalp—is completely free of notable changes.

Parents Fear Infant May Have Skin Cancer

ANSWER

The correct answer is Mongolian spot (choice “a”), which is seen in about 90% of newborn Native Americans. True ecchymosis (choice “b”) would not persist beyond a few days at most. Blue nevus (choice “c”) is still possible, but unlikely given the archetypical presentation and commonality of this Mongolian spot. If serious consideration were to be given to either blue nevus or nevus of Ito (choice “d”), biopsy would have to be done. However, the latter is quite unusual, while the former is usually much smaller than the patient’s lesion.

DISCUSSION

The Mongolian spot, also known as congenital dermal melanocytosis, usually presents either at birth or shortly thereafter and disappears by age 4. It only involves the skin and results from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during their migration from the neural crest to the epidermis. This case illustrates a typical location, but Mongolian spots can present as multiple lesions, usually on the posterior trunk, or as one large (> 20 cm) lesion. Fortunately, they are not associated with significant mortality or morbidity.

In addition to its high prevalence in Native Americans, Mongolian spots are seen on approximately 80% of Asian and 70% of Hispanic newborns, but less than 10% of white babies.

Blue nevi are quite common, representing a type of melanocytic nevus that is totally benign. Their color is actually brown, but these lesions develop relatively deep in the dermis and when viewed through the skin, appear blue—hence the name. Blue nevi, typically much smaller than our patient’s Mongolian spot, are often removed to rule out melanoma, which they can resemble at times.

The rare nevus of Ito represents a benign dermal melanocytic condition. It most commonly affects the shoulder.

ANSWER

The correct answer is Mongolian spot (choice “a”), which is seen in about 90% of newborn Native Americans. True ecchymosis (choice “b”) would not persist beyond a few days at most. Blue nevus (choice “c”) is still possible, but unlikely given the archetypical presentation and commonality of this Mongolian spot. If serious consideration were to be given to either blue nevus or nevus of Ito (choice “d”), biopsy would have to be done. However, the latter is quite unusual, while the former is usually much smaller than the patient’s lesion.

DISCUSSION

The Mongolian spot, also known as congenital dermal melanocytosis, usually presents either at birth or shortly thereafter and disappears by age 4. It only involves the skin and results from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during their migration from the neural crest to the epidermis. This case illustrates a typical location, but Mongolian spots can present as multiple lesions, usually on the posterior trunk, or as one large (> 20 cm) lesion. Fortunately, they are not associated with significant mortality or morbidity.

In addition to its high prevalence in Native Americans, Mongolian spots are seen on approximately 80% of Asian and 70% of Hispanic newborns, but less than 10% of white babies.

Blue nevi are quite common, representing a type of melanocytic nevus that is totally benign. Their color is actually brown, but these lesions develop relatively deep in the dermis and when viewed through the skin, appear blue—hence the name. Blue nevi, typically much smaller than our patient’s Mongolian spot, are often removed to rule out melanoma, which they can resemble at times.

The rare nevus of Ito represents a benign dermal melanocytic condition. It most commonly affects the shoulder.

ANSWER

The correct answer is Mongolian spot (choice “a”), which is seen in about 90% of newborn Native Americans. True ecchymosis (choice “b”) would not persist beyond a few days at most. Blue nevus (choice “c”) is still possible, but unlikely given the archetypical presentation and commonality of this Mongolian spot. If serious consideration were to be given to either blue nevus or nevus of Ito (choice “d”), biopsy would have to be done. However, the latter is quite unusual, while the former is usually much smaller than the patient’s lesion.

DISCUSSION

The Mongolian spot, also known as congenital dermal melanocytosis, usually presents either at birth or shortly thereafter and disappears by age 4. It only involves the skin and results from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during their migration from the neural crest to the epidermis. This case illustrates a typical location, but Mongolian spots can present as multiple lesions, usually on the posterior trunk, or as one large (> 20 cm) lesion. Fortunately, they are not associated with significant mortality or morbidity.

In addition to its high prevalence in Native Americans, Mongolian spots are seen on approximately 80% of Asian and 70% of Hispanic newborns, but less than 10% of white babies.

Blue nevi are quite common, representing a type of melanocytic nevus that is totally benign. Their color is actually brown, but these lesions develop relatively deep in the dermis and when viewed through the skin, appear blue—hence the name. Blue nevi, typically much smaller than our patient’s Mongolian spot, are often removed to rule out melanoma, which they can resemble at times.

The rare nevus of Ito represents a benign dermal melanocytic condition. It most commonly affects the shoulder.

A 3-week-old infant is referred to dermatology for evaluation of a lesion on the sacral area. The lesion has been present since the child’s birth and has not changed since then. The child is otherwise healthy, and a pediatrician diagnosed the lesion as benign. However, the parents, who are both Native American, are nonetheless alarmed. Part of their concern relates to the possibility of trauma or skin cancer. The lesion is round, located on the lower left sacral area, and uniformly purple. The surface is totally macular and measures about 2.5 cm. Its margins are uniform, and no underlying induration or other changes can be palpated. No other notable lesions can be found on the child. Dermatoscopic examination shows uniform faint, bluish pigment.

Diagnosing a Sun Exposed Thumbnail

ANSWER

The correct answer is to biopsy the proximal origin of the lesion (choice “d”), because this lesion could represent a subungual melanoma, a potentially lethal cancer. In this patient’s case, with his personal sun damage and family history of melanoma, simple reassurance (choice “a”) would have been inappropriate. Submitting a portion of the distal nail plate to pathology (choice “b”) contributes nothing to the process of distinguishing benign from malignant. Seeing the patient every few months (choice “c”) ignores the present potentially dangerous situation, although it would at least keep the patient in the loop

DISCUSSION

The so-called acral lentiginous (AL) melanomas (by definition, on feet or hands, under nails, in oral tissues, or in perianal, scalp, and genital areas) are especially dangerous by virtue of location. Detection and removal are often delayed as a result.

While ALs constitute only 7% of melanomas overall, they account for more than half of all melanomas in Asian and black people. These patients have a far worse prognosis with AL than would be expected.

Subungual melanonychia is usually benign, but is suspicious for AL melanoma under certain circumstances. Patients at risk include:

• Those in their fifth to seventh decade of life

• Those who have a pigment stripe larger than 3 mm

• Those who experience changes in the lesion.

Thumbnails are especially at risk compared, for example, to the index fingernail or toenail. Other factors include extension of pigment onto surrounding paronychial skin (Hutchinson sign) and positive personal or family history of melanoma.

Our patient’s thumb lesion, his positive family history of melanoma, the width of his lesion, and his age all spoke to the need for biopsy. This can be done directly through the nail plate into the most proximal aspect of the lesion.

Alternatively, the cuticle can be surgically reflected proximally to facilitate removal of a portion of the proximal nail and subsequent biopsy or even removal of the lesion. Obviously, most patients with these lesions will need to be referred to dermatology for this procedure.

It is also important to note that by age 20, 77% of African-American patients will have developed at least one of these lesions. By age 50, virtually 100% of them will display the condition, often in the form of multiple lesions. These are almost always benign but bear watching for substantive change.

One should also be aware that 20% to 30% of all subungual melanomas are amelanotic—that is, they do not display dark pigment. Instead, they can be white, almost colorless, light tan, or even pink, so the key word is change.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to biopsy the proximal origin of the lesion (choice “d”), because this lesion could represent a subungual melanoma, a potentially lethal cancer. In this patient’s case, with his personal sun damage and family history of melanoma, simple reassurance (choice “a”) would have been inappropriate. Submitting a portion of the distal nail plate to pathology (choice “b”) contributes nothing to the process of distinguishing benign from malignant. Seeing the patient every few months (choice “c”) ignores the present potentially dangerous situation, although it would at least keep the patient in the loop

DISCUSSION

The so-called acral lentiginous (AL) melanomas (by definition, on feet or hands, under nails, in oral tissues, or in perianal, scalp, and genital areas) are especially dangerous by virtue of location. Detection and removal are often delayed as a result.

While ALs constitute only 7% of melanomas overall, they account for more than half of all melanomas in Asian and black people. These patients have a far worse prognosis with AL than would be expected.

Subungual melanonychia is usually benign, but is suspicious for AL melanoma under certain circumstances. Patients at risk include:

• Those in their fifth to seventh decade of life

• Those who have a pigment stripe larger than 3 mm

• Those who experience changes in the lesion.

Thumbnails are especially at risk compared, for example, to the index fingernail or toenail. Other factors include extension of pigment onto surrounding paronychial skin (Hutchinson sign) and positive personal or family history of melanoma.

Our patient’s thumb lesion, his positive family history of melanoma, the width of his lesion, and his age all spoke to the need for biopsy. This can be done directly through the nail plate into the most proximal aspect of the lesion.

Alternatively, the cuticle can be surgically reflected proximally to facilitate removal of a portion of the proximal nail and subsequent biopsy or even removal of the lesion. Obviously, most patients with these lesions will need to be referred to dermatology for this procedure.

It is also important to note that by age 20, 77% of African-American patients will have developed at least one of these lesions. By age 50, virtually 100% of them will display the condition, often in the form of multiple lesions. These are almost always benign but bear watching for substantive change.

One should also be aware that 20% to 30% of all subungual melanomas are amelanotic—that is, they do not display dark pigment. Instead, they can be white, almost colorless, light tan, or even pink, so the key word is change.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to biopsy the proximal origin of the lesion (choice “d”), because this lesion could represent a subungual melanoma, a potentially lethal cancer. In this patient’s case, with his personal sun damage and family history of melanoma, simple reassurance (choice “a”) would have been inappropriate. Submitting a portion of the distal nail plate to pathology (choice “b”) contributes nothing to the process of distinguishing benign from malignant. Seeing the patient every few months (choice “c”) ignores the present potentially dangerous situation, although it would at least keep the patient in the loop

DISCUSSION

The so-called acral lentiginous (AL) melanomas (by definition, on feet or hands, under nails, in oral tissues, or in perianal, scalp, and genital areas) are especially dangerous by virtue of location. Detection and removal are often delayed as a result.

While ALs constitute only 7% of melanomas overall, they account for more than half of all melanomas in Asian and black people. These patients have a far worse prognosis with AL than would be expected.

Subungual melanonychia is usually benign, but is suspicious for AL melanoma under certain circumstances. Patients at risk include:

• Those in their fifth to seventh decade of life

• Those who have a pigment stripe larger than 3 mm

• Those who experience changes in the lesion.

Thumbnails are especially at risk compared, for example, to the index fingernail or toenail. Other factors include extension of pigment onto surrounding paronychial skin (Hutchinson sign) and positive personal or family history of melanoma.

Our patient’s thumb lesion, his positive family history of melanoma, the width of his lesion, and his age all spoke to the need for biopsy. This can be done directly through the nail plate into the most proximal aspect of the lesion.

Alternatively, the cuticle can be surgically reflected proximally to facilitate removal of a portion of the proximal nail and subsequent biopsy or even removal of the lesion. Obviously, most patients with these lesions will need to be referred to dermatology for this procedure.

It is also important to note that by age 20, 77% of African-American patients will have developed at least one of these lesions. By age 50, virtually 100% of them will display the condition, often in the form of multiple lesions. These are almost always benign but bear watching for substantive change.

One should also be aware that 20% to 30% of all subungual melanomas are amelanotic—that is, they do not display dark pigment. Instead, they can be white, almost colorless, light tan, or even pink, so the key word is change.

A 51-year-old white man is seen for evaluation of a dark subungual stripe that appeared in his thumbnail six months ago. There are no symptoms to report and no history of trauma to the digit. His health is reportedly perfect otherwise. When questioned, the patient admits to regular unprotected sun exposure. He chalks this up to the necessity of yard work, both at home and at his family’s lake cabin, where they spend several weekends and holidays each year. The patient’s father died of melanoma years ago. On examination, a 3-mm-wide dark brown longitudinal stripe is seen on the affected fingernail, beginning in the distal lunular area and extending to the end of the nail plate. The margins of the stripe are quite even, as is the color. No such color changes are seen in the surrounding paronychial skin. The other fingernails and the toenails are free of changes. The patient is quite fair, with blue eyes, reddish brown hair, and modest dermatoheliosis. However, no distinctly worrisome lesions are seen.

What is the Next Step in Dealing With This Lesion?

DISCUSSION

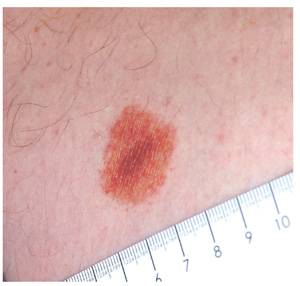

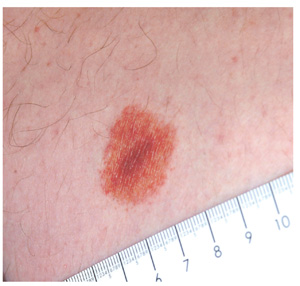

Punch biopsy confirmed the clinical impression of lichen aureus. This is one of several types of pigmented purpuric dermatoses, all of which involve extravasation of red blood cells and marked localized deposition of hemosiderin.

Some researchers consider all other forms to represent variants of the most common type, Schamberg’s disease, which typically begins with symmetrical involvement of the lower portions of both legs, slowly ascending to mid-thigh or (less often) to the waistline, then just as slowly descending—resolving, in most cases, in months to years. The hallmark of most types of pigmented purpuras is an orange-brown, speckled macular cayenne pepper–like discoloration.

Lichen aureus, one of the least common types, usually appears on the legs of adolescents and young adults. It presents as a solitary copper-colored macule or patch that is nonblanchable on digital pressure, confirming the presence of extravasated red blood cells.

Biopsy shows a T-cell infiltrate centered in the walls of small blood vessels, with endothelial cell swelling, narrowing of vessel lumens, extravasation of red blood cells, and marked hemosiderin deposition in macrophages.

The cause of the pigmented purpuric dermatoses is unknown. However, the predominately lower-leg involvement and hemosiderin deposition strongly suggest a role for venous stasis, gravitational dependence, increased activity while upright, or all three.

In addition to lichen aureus and Schamberg’s disease, several other forms of pigmented purpura have been noted. These include:

• Purpura annularis telangiectodes (Majocchi’s disease): Small annular plaques with prominent telangiectasias start, as does Schamberg’s, on bilateral distal extremities and spread proximally. The lesions tend to become targetoid (displaying concentric light and dark rings). This type is more common in young women and can occur in areas other than the legs.

• Eczematid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis: This condition involves pruritic eczematous papulosquamous annular lesions with sparse petechiae and hemosiderin staining. Histologically, it is characterized by the presence of spongiosis (intercellular edema of the epidermis). It must be distinguished from cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which it can resemble both clinically and histologically.

• Gougerot-Blum syndrome: This condition, also known as pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis, starts with lichenoid papules that fuse into reddish-blue to purple plaques. It is notable among the various pigmented purpuras for the presence of underlying induration, caused by a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate

The differential in this case also includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which was successfully ruled out with the biopsy, as were drug rash and contact dermatitis.

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, no good treatment exists for lichen aureus; however, the condition usually fades on its own over time, typically leaving no blemish behind. As it happens, there are no systemic implications of any of the pigmented purpuras.

DISCUSSION

Punch biopsy confirmed the clinical impression of lichen aureus. This is one of several types of pigmented purpuric dermatoses, all of which involve extravasation of red blood cells and marked localized deposition of hemosiderin.

Some researchers consider all other forms to represent variants of the most common type, Schamberg’s disease, which typically begins with symmetrical involvement of the lower portions of both legs, slowly ascending to mid-thigh or (less often) to the waistline, then just as slowly descending—resolving, in most cases, in months to years. The hallmark of most types of pigmented purpuras is an orange-brown, speckled macular cayenne pepper–like discoloration.

Lichen aureus, one of the least common types, usually appears on the legs of adolescents and young adults. It presents as a solitary copper-colored macule or patch that is nonblanchable on digital pressure, confirming the presence of extravasated red blood cells.

Biopsy shows a T-cell infiltrate centered in the walls of small blood vessels, with endothelial cell swelling, narrowing of vessel lumens, extravasation of red blood cells, and marked hemosiderin deposition in macrophages.

The cause of the pigmented purpuric dermatoses is unknown. However, the predominately lower-leg involvement and hemosiderin deposition strongly suggest a role for venous stasis, gravitational dependence, increased activity while upright, or all three.

In addition to lichen aureus and Schamberg’s disease, several other forms of pigmented purpura have been noted. These include:

• Purpura annularis telangiectodes (Majocchi’s disease): Small annular plaques with prominent telangiectasias start, as does Schamberg’s, on bilateral distal extremities and spread proximally. The lesions tend to become targetoid (displaying concentric light and dark rings). This type is more common in young women and can occur in areas other than the legs.

• Eczematid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis: This condition involves pruritic eczematous papulosquamous annular lesions with sparse petechiae and hemosiderin staining. Histologically, it is characterized by the presence of spongiosis (intercellular edema of the epidermis). It must be distinguished from cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which it can resemble both clinically and histologically.

• Gougerot-Blum syndrome: This condition, also known as pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis, starts with lichenoid papules that fuse into reddish-blue to purple plaques. It is notable among the various pigmented purpuras for the presence of underlying induration, caused by a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate

The differential in this case also includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which was successfully ruled out with the biopsy, as were drug rash and contact dermatitis.

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, no good treatment exists for lichen aureus; however, the condition usually fades on its own over time, typically leaving no blemish behind. As it happens, there are no systemic implications of any of the pigmented purpuras.

DISCUSSION

Punch biopsy confirmed the clinical impression of lichen aureus. This is one of several types of pigmented purpuric dermatoses, all of which involve extravasation of red blood cells and marked localized deposition of hemosiderin.

Some researchers consider all other forms to represent variants of the most common type, Schamberg’s disease, which typically begins with symmetrical involvement of the lower portions of both legs, slowly ascending to mid-thigh or (less often) to the waistline, then just as slowly descending—resolving, in most cases, in months to years. The hallmark of most types of pigmented purpuras is an orange-brown, speckled macular cayenne pepper–like discoloration.

Lichen aureus, one of the least common types, usually appears on the legs of adolescents and young adults. It presents as a solitary copper-colored macule or patch that is nonblanchable on digital pressure, confirming the presence of extravasated red blood cells.

Biopsy shows a T-cell infiltrate centered in the walls of small blood vessels, with endothelial cell swelling, narrowing of vessel lumens, extravasation of red blood cells, and marked hemosiderin deposition in macrophages.

The cause of the pigmented purpuric dermatoses is unknown. However, the predominately lower-leg involvement and hemosiderin deposition strongly suggest a role for venous stasis, gravitational dependence, increased activity while upright, or all three.

In addition to lichen aureus and Schamberg’s disease, several other forms of pigmented purpura have been noted. These include:

• Purpura annularis telangiectodes (Majocchi’s disease): Small annular plaques with prominent telangiectasias start, as does Schamberg’s, on bilateral distal extremities and spread proximally. The lesions tend to become targetoid (displaying concentric light and dark rings). This type is more common in young women and can occur in areas other than the legs.

• Eczematid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis: This condition involves pruritic eczematous papulosquamous annular lesions with sparse petechiae and hemosiderin staining. Histologically, it is characterized by the presence of spongiosis (intercellular edema of the epidermis). It must be distinguished from cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which it can resemble both clinically and histologically.

• Gougerot-Blum syndrome: This condition, also known as pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis, starts with lichenoid papules that fuse into reddish-blue to purple plaques. It is notable among the various pigmented purpuras for the presence of underlying induration, caused by a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate

The differential in this case also includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which was successfully ruled out with the biopsy, as were drug rash and contact dermatitis.

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, no good treatment exists for lichen aureus; however, the condition usually fades on its own over time, typically leaving no blemish behind. As it happens, there are no systemic implications of any of the pigmented purpuras.

An 18-year-old man is referred to dermatology for evaluation of an asymptomatic lesion that has been present on his left inner thigh for several months. The lesion has persisted despite the use of a topical cream containing clotrimazole and betamethasone (applied twice daily for a week) and a subsequent 10-day course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d). Neither treatment seems to have had any impact. There is no history of antecedent trauma. The patient and his family report that no other lesions have been noted and that the patient is quite healthy in other respects. However, there is a family history of melanoma, which has caused the parents more than a little concern. Examination reveals a 3-cm reddish brown polygonal macule with a darker center, located on the left inner thigh. The lesion is neither palpable nor blanchable with digital pressure. No such lesions are seen elsewhere on the patient’s body.

Soap and Water Will Not Clean Dirty Skin

ANSWER

The correct answer is terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD; choice “d”), also known as “Duncan’s dirty dermatosis.” This relatively common condition usually affects adolescents and is one of the very few causes of hyperpigmentation that can be removed specifically with alcohol.

Dirty skin (choice “a”) is certainly seen, especially in this age-group, but the dirt is easily removed with soap and water.

Acanthosis nigricans (choice “b”) is often mistaken for dirty skin, but it cannot be removed by any nondestructive modality. Moreover, the most common form of acanthosis nigricans presents with a velvety, faintly raised brownish discoloration that usually affects the circumferential neck, axillae, and often, other intertriginous areas.

Reticulated and confluent papillomatosis (choice “c”) is a rare condition seen on the chest, back, and occasionally the face. It involves a slightly papular reticular (a netlike effect) patch, often in a triangular shape. Alcohol has no effect on it.

DISCUSSION

TFFD is surprisingly common, once its existence is recognized. Its etiology is, as one might expect, unknown, but it has been described in the literature (see “Suggested Reading” for examples) and is also defined by predictable histologic features seen on biopsy.

Besides the obvious implications, TFFD is probably most important as an imitator of acanthosis nigricans, which is often seen in overweight adolescents on their way to becoming diabetic. Unlike TFFD, acanthosis nigricans (type III, the most common form) has a multitude of potentially serious implications, although it is most often benign. Besides its well-known potential connection with diabetes, acanthosis nigricans can be seen in a myriad of insulin-resistant states and a bewildering variety of endocrinopathies.

SUMMARY

Unnecessary treatments and/or workups can be avoided by being aware of the existence of this common condition, which is easily diagnosed (and treated!) by wiping with alcohol—effectively ruling out the other items in the differential.

SUGGESTED READING

Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987; 123(5):567-569.

Pavlovic MD, Dragos V, Potocnik M, Adamic M. Terra firma-forme dermatosis in a child. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2008;17(1):41-42.

ANSWER

The correct answer is terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD; choice “d”), also known as “Duncan’s dirty dermatosis.” This relatively common condition usually affects adolescents and is one of the very few causes of hyperpigmentation that can be removed specifically with alcohol.

Dirty skin (choice “a”) is certainly seen, especially in this age-group, but the dirt is easily removed with soap and water.

Acanthosis nigricans (choice “b”) is often mistaken for dirty skin, but it cannot be removed by any nondestructive modality. Moreover, the most common form of acanthosis nigricans presents with a velvety, faintly raised brownish discoloration that usually affects the circumferential neck, axillae, and often, other intertriginous areas.

Reticulated and confluent papillomatosis (choice “c”) is a rare condition seen on the chest, back, and occasionally the face. It involves a slightly papular reticular (a netlike effect) patch, often in a triangular shape. Alcohol has no effect on it.

DISCUSSION

TFFD is surprisingly common, once its existence is recognized. Its etiology is, as one might expect, unknown, but it has been described in the literature (see “Suggested Reading” for examples) and is also defined by predictable histologic features seen on biopsy.

Besides the obvious implications, TFFD is probably most important as an imitator of acanthosis nigricans, which is often seen in overweight adolescents on their way to becoming diabetic. Unlike TFFD, acanthosis nigricans (type III, the most common form) has a multitude of potentially serious implications, although it is most often benign. Besides its well-known potential connection with diabetes, acanthosis nigricans can be seen in a myriad of insulin-resistant states and a bewildering variety of endocrinopathies.

SUMMARY

Unnecessary treatments and/or workups can be avoided by being aware of the existence of this common condition, which is easily diagnosed (and treated!) by wiping with alcohol—effectively ruling out the other items in the differential.

SUGGESTED READING

Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987; 123(5):567-569.

Pavlovic MD, Dragos V, Potocnik M, Adamic M. Terra firma-forme dermatosis in a child. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2008;17(1):41-42.

ANSWER

The correct answer is terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD; choice “d”), also known as “Duncan’s dirty dermatosis.” This relatively common condition usually affects adolescents and is one of the very few causes of hyperpigmentation that can be removed specifically with alcohol.

Dirty skin (choice “a”) is certainly seen, especially in this age-group, but the dirt is easily removed with soap and water.

Acanthosis nigricans (choice “b”) is often mistaken for dirty skin, but it cannot be removed by any nondestructive modality. Moreover, the most common form of acanthosis nigricans presents with a velvety, faintly raised brownish discoloration that usually affects the circumferential neck, axillae, and often, other intertriginous areas.

Reticulated and confluent papillomatosis (choice “c”) is a rare condition seen on the chest, back, and occasionally the face. It involves a slightly papular reticular (a netlike effect) patch, often in a triangular shape. Alcohol has no effect on it.

DISCUSSION

TFFD is surprisingly common, once its existence is recognized. Its etiology is, as one might expect, unknown, but it has been described in the literature (see “Suggested Reading” for examples) and is also defined by predictable histologic features seen on biopsy.

Besides the obvious implications, TFFD is probably most important as an imitator of acanthosis nigricans, which is often seen in overweight adolescents on their way to becoming diabetic. Unlike TFFD, acanthosis nigricans (type III, the most common form) has a multitude of potentially serious implications, although it is most often benign. Besides its well-known potential connection with diabetes, acanthosis nigricans can be seen in a myriad of insulin-resistant states and a bewildering variety of endocrinopathies.

SUMMARY

Unnecessary treatments and/or workups can be avoided by being aware of the existence of this common condition, which is easily diagnosed (and treated!) by wiping with alcohol—effectively ruling out the other items in the differential.

SUGGESTED READING

Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987; 123(5):567-569.

Pavlovic MD, Dragos V, Potocnik M, Adamic M. Terra firma-forme dermatosis in a child. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2008;17(1):41-42.

The mother of a 14-year-old girl brings the child into your clinic, essentially to gain support in her effort to convince the child to wash better. It seems that several times a year, areas of the girl’s arms and neck appear to be dirty, despite protestations of adequate washing by the patient, who will not let her mother (or anyone else, to date) scrub the areas. The patient denies having any symptoms in the affected areas and further denies applying any medication to them. She wears no jewelry that might have touched the areas. According to the mother and the patient, the latter is otherwise healthy. She almost never takes any medication, and she had normal blood work (including blood sugar) as part of a recent physical exam. There is no family history of serious health problems, such as diabetes or skin diseases. The child seldom exerts to the point of perspiration, although she does swim once or twice a week for exercise. You note that the child is moderately overweight and quite reluctant to allow anyone to see or touch the areas in question. But with considerable time and much persuasion, she allows you to examine and palpate her skin, which has a slight olive tone (type IV). The ill-defined, light brown macular discoloration stands out and indeed looks like dirt. However, it is confined to the patient’s anterior neck and lateral arms. Although there is no palpable component to the discoloration, it has a faintly reticular look to it in places. It spares all other locations, such as the axillae, posterior neck, and back. A brief scrub with soap and water fails to have any effect on the discoloration, but a few swipes with an alcohol swab completely restore the skin to its normal, light color, effectively removing the pigmented surface.

Is This Man's Eczema Spreading?

Answer

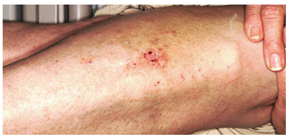

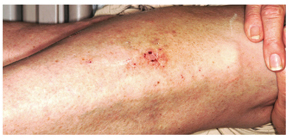

The correct answer is neurodermatitis with associated “id” reaction (choice “c”). The patient probably did have eczema (choice “d”) on his legs, but it became secondarily infected, leading to the later appearance of the arm rash. There was nothing to suggest that this condition was fungal in nature (choice “a”), nor were there any signs of psoriasis (choice “b”).

Discussion Cutaneous reactions to bacterial, fungal, viral, and other antigens have long been recognized as diagnostic entities in dermatology and are usually termed “id” reactions (though an older term, autoeczematization, is also used). “Id” reactions are quite common, particularly in association with inciting conditions such as stasis dermatitis and neurodermatitis. The diagnosis is facilitated by the finding of two different rashes in distant locations that appear sequentially.

This case typifies one of the more common presentations: a bacterid reaction that stems from secondary bacterial infection of neurodermatitis, which is itself secondary to eczema, which, in this particular case, was a manifestation of atopic dermatitis. Recognition of the latter point is significant, since patients with atopic dermatitis are known to have dry, sensitive skin, a lowered threshold for pruritus, and increased numbers of Staphylococcus epidermidis that colonize and invade chronically excoriated skin. This is followed, within days to weeks, by the appearance of a papulovesicular rash at a distant site—often on the volar forearms.

The most common presentation of the bacterid phenomenon starts with stasis dermatitis (venous stasis disease), which becomes, in turn, pruritic and excoriated, then secondarily infected. Inflammatory tinea pedis can trigger a fungal id (“fungid”) reaction at distant sites, especially on the hands and fingers. Acute herpes simplex virus outbreaks are another known culprit, resulting in a more generalized, erythema multiforme–like eruption.

Whatever the trigger, the secondary “id” rash is, by definition, distant to the original, usually symmetrical in distribution, and most often composed of morphologically different lesions. In addition to the arms, it can also involve the neck, trunk, hands, and feet.

Treatment Treatment is twofold, as it must address both the precipitating infection (in this case, with cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days) and the underlying skin condition (in this case, with topical fluocinolone 0.05% ointment applied bid to the legs and daily use of emollients). In severe cases, we often prescribe a 10- to 14-day tapering course of prednisone as well. Direct treatment of the arm rash is not necessary, since it will clear with treatment of the triggering condition.

Answer

The correct answer is neurodermatitis with associated “id” reaction (choice “c”). The patient probably did have eczema (choice “d”) on his legs, but it became secondarily infected, leading to the later appearance of the arm rash. There was nothing to suggest that this condition was fungal in nature (choice “a”), nor were there any signs of psoriasis (choice “b”).

Discussion Cutaneous reactions to bacterial, fungal, viral, and other antigens have long been recognized as diagnostic entities in dermatology and are usually termed “id” reactions (though an older term, autoeczematization, is also used). “Id” reactions are quite common, particularly in association with inciting conditions such as stasis dermatitis and neurodermatitis. The diagnosis is facilitated by the finding of two different rashes in distant locations that appear sequentially.

This case typifies one of the more common presentations: a bacterid reaction that stems from secondary bacterial infection of neurodermatitis, which is itself secondary to eczema, which, in this particular case, was a manifestation of atopic dermatitis. Recognition of the latter point is significant, since patients with atopic dermatitis are known to have dry, sensitive skin, a lowered threshold for pruritus, and increased numbers of Staphylococcus epidermidis that colonize and invade chronically excoriated skin. This is followed, within days to weeks, by the appearance of a papulovesicular rash at a distant site—often on the volar forearms.

The most common presentation of the bacterid phenomenon starts with stasis dermatitis (venous stasis disease), which becomes, in turn, pruritic and excoriated, then secondarily infected. Inflammatory tinea pedis can trigger a fungal id (“fungid”) reaction at distant sites, especially on the hands and fingers. Acute herpes simplex virus outbreaks are another known culprit, resulting in a more generalized, erythema multiforme–like eruption.

Whatever the trigger, the secondary “id” rash is, by definition, distant to the original, usually symmetrical in distribution, and most often composed of morphologically different lesions. In addition to the arms, it can also involve the neck, trunk, hands, and feet.

Treatment Treatment is twofold, as it must address both the precipitating infection (in this case, with cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days) and the underlying skin condition (in this case, with topical fluocinolone 0.05% ointment applied bid to the legs and daily use of emollients). In severe cases, we often prescribe a 10- to 14-day tapering course of prednisone as well. Direct treatment of the arm rash is not necessary, since it will clear with treatment of the triggering condition.

Answer

The correct answer is neurodermatitis with associated “id” reaction (choice “c”). The patient probably did have eczema (choice “d”) on his legs, but it became secondarily infected, leading to the later appearance of the arm rash. There was nothing to suggest that this condition was fungal in nature (choice “a”), nor were there any signs of psoriasis (choice “b”).

Discussion Cutaneous reactions to bacterial, fungal, viral, and other antigens have long been recognized as diagnostic entities in dermatology and are usually termed “id” reactions (though an older term, autoeczematization, is also used). “Id” reactions are quite common, particularly in association with inciting conditions such as stasis dermatitis and neurodermatitis. The diagnosis is facilitated by the finding of two different rashes in distant locations that appear sequentially.

This case typifies one of the more common presentations: a bacterid reaction that stems from secondary bacterial infection of neurodermatitis, which is itself secondary to eczema, which, in this particular case, was a manifestation of atopic dermatitis. Recognition of the latter point is significant, since patients with atopic dermatitis are known to have dry, sensitive skin, a lowered threshold for pruritus, and increased numbers of Staphylococcus epidermidis that colonize and invade chronically excoriated skin. This is followed, within days to weeks, by the appearance of a papulovesicular rash at a distant site—often on the volar forearms.

The most common presentation of the bacterid phenomenon starts with stasis dermatitis (venous stasis disease), which becomes, in turn, pruritic and excoriated, then secondarily infected. Inflammatory tinea pedis can trigger a fungal id (“fungid”) reaction at distant sites, especially on the hands and fingers. Acute herpes simplex virus outbreaks are another known culprit, resulting in a more generalized, erythema multiforme–like eruption.

Whatever the trigger, the secondary “id” rash is, by definition, distant to the original, usually symmetrical in distribution, and most often composed of morphologically different lesions. In addition to the arms, it can also involve the neck, trunk, hands, and feet.

Treatment Treatment is twofold, as it must address both the precipitating infection (in this case, with cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days) and the underlying skin condition (in this case, with topical fluocinolone 0.05% ointment applied bid to the legs and daily use of emollients). In severe cases, we often prescribe a 10- to 14-day tapering course of prednisone as well. Direct treatment of the arm rash is not necessary, since it will clear with treatment of the triggering condition.

A 30-year-old man presents with a pruritic rash that first affected both legs and was followed two weeks later by the appearance of a different but equally pruritic rash on his volar forearms. These rashes have persisted despite the use of OTC topical steroid and antifungal creams, triple-antibiotic ointment, and frequent application of rubbing alcohol. Eczema has been a problem throughout the patient’s life, but since his 20s, it has mostly affected his lower legs. As a result, he has gotten into the habit of scratching, even fantasizing about being able to do so at home. Despite being remarkably atopic, with seasonal allergies and generally sensitive skin, he claims to be otherwise healthy. Examination of the patient’s legs shows heavily lichenified papulosquamous involvement of both legs. There are numerous focal areas of scabbing, redness, and edema, which sharply spare the skin under his socks, thin out, then disappear well below the knees. The patient is even observed scratching these areas as the history is taken, and readily admits doing so several times a day. A fairly dense, symmetrical papulovesicular rash is noted on both volar forearms, with only a few lesions remaining intact because of scratching. Elsewhere, his elbows, knees, scalp, and nail plates are free of significant changes.

Infant with Unrelenting Rash

Answer

The correct answer is intertrigo (choice “a”), an inflammatory condition seen only where skin touches skin—the so-called intertriginous areas such as axillae, groins, and in the case of babies, the rolls of their necks. Read on for further discussion.

Intertrigo is often mistaken for “yeast infection” (choice “b”). While yeast can colonize and worsen intertrigo, it is not the main cause of the problem.

Intertrigo is often difficult to treat, which leads many patients and providers to apply several different topical medications. It is therefore not unusual to see intertrigo worsened by way of an irritant or contact dermatitis (choice “c”) from one or more of these products. But again, this is not the basic nature of the problem.

Impetigo (choice “d”) is a superficial infection caused by a secondary staph and/or strep infection of skin disrupted by excoriated acne or eczema. Usually a localized process, it typically demonstrates a honey-colored surface on an eroded base, and looks entirely different from our patient’s rash.

Discussion

Warmth, friction, and moisture all conspire to result in maceration (disruption of barrier function); when chronic in nature, this manifests as an inflammatory rash in intertriginous areas. The classic example is seen in the inframammary area in obese women, with a worsening condition in warmer weather. But it can occur in any patient at any age, given the right conditions. The baby who drools into the cute chubby folds of its neck is a good example, for more than one reason.

For parents, the appearance of this rash is alarming to say the least. Everyone offers an opinion, from grandparents to pharmacists. Multiple creams not only fail to help, they often seem to make things worse. Primary care providers are dismayed to find that antiyeast creams don’t work, which often leads them to try a different antiyeast preparation—with the same result.

The explanation is simple: It is intertrigo, not an infection. Candida, being a ubiquitous contaminant of skin, is also an opportunistic organism that can play a role in intertrigo, but the latter is usually more about inflammation than it is infection. Even oral antiyeast medications such as fluconazole are of little help. In the unusual instance when Candida is a major player, multiple discrete erythematous papular erosions are seen as so-called “satellites” on the periphery of the process. Diabetes and/or immunosuppression are often involved in those instances.

Treatment

In this case, successful treatment entailed twice-daily application of a half-and-half mixture of hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and oxiconazole cream. Also recommended was the use of once-daily two-minute compresses of Burow’s solution (aluminum acetate powder, OTC, mixed with water according to package instructions), which dries the area.

Recurrences can be prevented with the application of a combination product containing miconazole cream and talcum-based powder at any sign of a flare; in the case of infants and children, care should be taken to avoid inhalation of the powder. (Miconazole, while ineffective as a treatment for intertrigo, is beneficial for prevention.) Starch-based powders are potentially counterproductive, since Candida actively feeds on starch.

When intertrigo occurs in the more classic inframammary location, a stronger steroid (such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream) is mixed with the oxiconazole. Additional strategies for dealing with perspiration include applying an actual antiperspirant to the area and/or cutting an old cotton t-shirt into strips that are then placed between the breasts and chest wall to cut down on chafing and provide absorption.

Answer

The correct answer is intertrigo (choice “a”), an inflammatory condition seen only where skin touches skin—the so-called intertriginous areas such as axillae, groins, and in the case of babies, the rolls of their necks. Read on for further discussion.

Intertrigo is often mistaken for “yeast infection” (choice “b”). While yeast can colonize and worsen intertrigo, it is not the main cause of the problem.

Intertrigo is often difficult to treat, which leads many patients and providers to apply several different topical medications. It is therefore not unusual to see intertrigo worsened by way of an irritant or contact dermatitis (choice “c”) from one or more of these products. But again, this is not the basic nature of the problem.

Impetigo (choice “d”) is a superficial infection caused by a secondary staph and/or strep infection of skin disrupted by excoriated acne or eczema. Usually a localized process, it typically demonstrates a honey-colored surface on an eroded base, and looks entirely different from our patient’s rash.

Discussion

Warmth, friction, and moisture all conspire to result in maceration (disruption of barrier function); when chronic in nature, this manifests as an inflammatory rash in intertriginous areas. The classic example is seen in the inframammary area in obese women, with a worsening condition in warmer weather. But it can occur in any patient at any age, given the right conditions. The baby who drools into the cute chubby folds of its neck is a good example, for more than one reason.

For parents, the appearance of this rash is alarming to say the least. Everyone offers an opinion, from grandparents to pharmacists. Multiple creams not only fail to help, they often seem to make things worse. Primary care providers are dismayed to find that antiyeast creams don’t work, which often leads them to try a different antiyeast preparation—with the same result.

The explanation is simple: It is intertrigo, not an infection. Candida, being a ubiquitous contaminant of skin, is also an opportunistic organism that can play a role in intertrigo, but the latter is usually more about inflammation than it is infection. Even oral antiyeast medications such as fluconazole are of little help. In the unusual instance when Candida is a major player, multiple discrete erythematous papular erosions are seen as so-called “satellites” on the periphery of the process. Diabetes and/or immunosuppression are often involved in those instances.

Treatment

In this case, successful treatment entailed twice-daily application of a half-and-half mixture of hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and oxiconazole cream. Also recommended was the use of once-daily two-minute compresses of Burow’s solution (aluminum acetate powder, OTC, mixed with water according to package instructions), which dries the area.

Recurrences can be prevented with the application of a combination product containing miconazole cream and talcum-based powder at any sign of a flare; in the case of infants and children, care should be taken to avoid inhalation of the powder. (Miconazole, while ineffective as a treatment for intertrigo, is beneficial for prevention.) Starch-based powders are potentially counterproductive, since Candida actively feeds on starch.

When intertrigo occurs in the more classic inframammary location, a stronger steroid (such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream) is mixed with the oxiconazole. Additional strategies for dealing with perspiration include applying an actual antiperspirant to the area and/or cutting an old cotton t-shirt into strips that are then placed between the breasts and chest wall to cut down on chafing and provide absorption.

Answer

The correct answer is intertrigo (choice “a”), an inflammatory condition seen only where skin touches skin—the so-called intertriginous areas such as axillae, groins, and in the case of babies, the rolls of their necks. Read on for further discussion.

Intertrigo is often mistaken for “yeast infection” (choice “b”). While yeast can colonize and worsen intertrigo, it is not the main cause of the problem.