User login

Transforming vaginal hysterectomy: 7 solutions to the most daunting challenges

Vaginal hysterectomy is the preferred route to benign hysterectomy because it is associated with better outcomes and fewer complications than the laparoscopic and open abdominal approaches.1,2 Yet, despite superior patient outcomes and cost benefits, the rate of vaginal hysterectomy is declining.

According to the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, the use of vaginal hysterectomy declined from 24.8% in 1998 to 16.7% in 2010.3 In fact, more than 80% of surgeons in the United States now perform fewer than five vaginal procedures in a year.4

The increasing use of other minimally invasive routes, such as laparoscopy and robotics, indicates that most practicing surgeons and recent graduates are choosing these approaches over the vaginal route. In only 3 years, the rate of laparoscopy increased by 6% and robotics increased by almost 10%.3

Many surgeons assume that vaginal hysterectomy exists in a state of suspended animation, with nothing much changed in the way it has been performed over the past few decades. Further, vaginal surgery is difficult to teach and learn, given limitations in exposure and visualization, difficulty in securing hemostasis, and challenges in the removal of the large uterus and adnexae. As a result, vaginal hysterectomy often is thought, erroneously, to be indicated only in procedures involving a small and prolapsing uterus.

To increase the rate of vaginal hysterectomy, we can benefit from experience gained in laparoscopy and robotics—whether we are teachers or learners—while maintaining patient safety and containing costs.

In this article, I describe common challenges in vaginal hysterectomy and offer tools and techniques to overcome them:

- achieving and enhancing ergonomics, exposure, and visualization

- the need to work in a long vaginal vault

- the task of securing vascular and thick tissue pedicles when the introitus and vaginal vault are narrow.

The vaginal approach is less costly

Vaginal hysterectomy costs significantly less to perform than other approaches. At a tertiary referral center, vaginal hysterectomy costs approximately $7,000 to $18,000 per case less than laparoscopic, abdominal, and robotic hysterectomy.5 With declining use of vaginal hysterectomy and increasing use of more costly approaches, we face a health-care crisis.

Residents are inadequately trained to perform vaginal hysterectomy

Data reveal that not only are our recent graduates inadequately prepared to perform vaginal hysterectomy, but national health-care dollars and resources are depleted when surgeons choose to perform more costly approaches. As a result, many eligible patients end up deprived of the benefits of a single, concealed, and minimally invasive procedure.

The increase in laparoscopic and robotic approaches to hysterectomy has affected residency training. National case log reports from the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education show that the number of vaginal hysterectomies performed by residents as “primary surgeons” decreased by 40%, from a mean of 35 cases in 2002 to 19 cases in 2012.6 A recent survey found that only 28% of graduating residents were “completely prepared” to perform a vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 58% for abdominal hysterectomy, 22% for laparoscopic hysterectomy, and 3% for the robotic approach.7

The rate of vaginal hysterectomy will continue to decline if we perform it in the same manner it was done 30 years ago. The current generation of practicing gynecologists and graduates is choosing to perform the procedure laparoscopically or robotically because of the advantages these technologies provide. It is time that we incorporate features from these minimally invasive approaches to streamline vaginal hysterectomy while maintaining patient safety and containing costs.

Challenges: Ergonomics, exposure, and visualization

In conventional vaginal surgery, the surgeon often is the person who has the best and, sometimes, the sole view. Two bedside assistants are required to hold retractors during the entire case, which can lead to fatigue and muscle strain. Poor lighting also can greatly limit visualization into the pelvic cavity.

Both laparoscopy and robotics provide a well-illuminated and magnified view, with three-dimensional images now available in both platforms. This view is projected to overhead monitors for the entire surgical team to see. Magnification of the pelvic anatomic structures and projection to an external monitor facilitate teaching and learning, better anticipation of the surgical and procedural needs, and overall patient safety.

From robotics, where ergonomics is exemplified, we also learn the importance of surgeon comfort during the procedure.

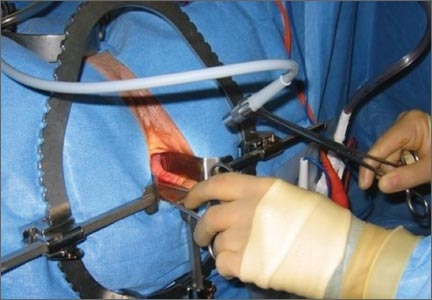

Solution #1: A self-retaining retractor

A self-retaining system such as the Magrina-Bookwalter vaginal retractor (Symmetry Surgical, Nashville, Tennessee) (FIGURE 1)

Solution #2: Seat the surgeon for an optimal view

With the patient in the lithotomy position and her legs in candy cane stirrups, the surgeon can be seated on a high chair so that the operative field is at the approximate level of the assistants’ view (FIGURE 2)

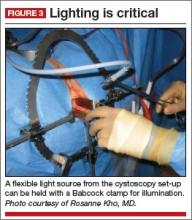

Solution #3: Illuminate the cavity

The deep pelvic cavity can be easily illuminated using a lighted suction tip, a flexible light source (as part of the cystoscopy set) held with a Babcock clamp (FIGURE 3), or a malleable illuminating mat taped to the retractor blades (such as Lightmat surgical illuminator, Lumitex, Inc., Strongsville, Ohio).

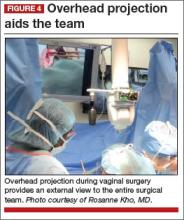

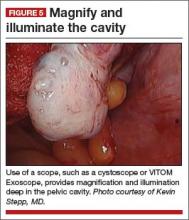

Solution #4: Project the image

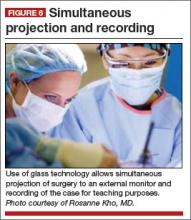

Cameras attached to an overhead boom or operating room light handles (FIGURE 4) and an external telescope with integrated illumination, such as a standard cystoscope or VITOM Exoscope (Karl Storz, El Segundo, California) (FIGURE 5) provide both magnification and projection of the procedure to an overhead monitor.

Glass technology (Google, Mountain View, California) also has been utilized in surgery and can be a good application of simultaneous projection and recording of the procedure to an external monitor (FIGURE 6). Google Glass is a wearable computer with an optical head-mounted display. The device, similar to eyeglasses, is voice-activated, thereby allowing the surgeon to record the procedure hands-free. Simultaneous projection to an external monitor allows the entire team in the operating room to be aware of the flow of the procedure.

Challenge: Working in a narrow vaginal vault

Without correct instrumentation, this challenge can be especially daunting. Laparoscopy and robotics have changed the way we perform pelvic surgery by providing advanced instrumentation.

Solution #5: Adapt your instruments

Modified vaginal instruments can be used to facilitate a case. Watch the accompanying VIDEO on the use of improved vaginal instruments during morcellation.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel |

| Click to enlarge >>> |

Among the instruments adaptable for vaginal surgery:

- curving, articulating instruments

- long, curved, and rounded knife handles, which allow for better ergonomics during prolonged morcellation

- modified long retractors and use of a single long vaginal pack provide retraction of loops of bowel and easy access to secure pedicles deep in the pelvis.

All of these instruments are available through Marina Medical in Sunrise, Florida.

Challenge: Securing vascular and thick tissue pediclesA narrow introitus and vaginal vault can be difficult to manage during vaginal surgery. Another challenge is a uterus that is large or deformed by multiple fibroids.

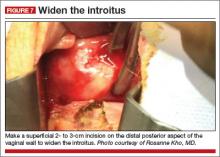

Solution #6: Vaginal incision

A simple superficial 2- to 3-cm incision on the distal posterior aspect of the vaginal wall can widen the introitus and vault to facilitate the procedure (FIGURE 7)

Solution #7: Vessel-sealing tools

The use of energy is integral to laparoscopy and robotics for dissection and securing vessels. In a meta-analysis that included seven randomized controlled trials, advanced vessel-sealing devices proved useful in vaginal surgery by decreasing blood loss and operative time.8

In the setting of a difficult vaginal hysterectomy with a narrow introitus and large uterus, the use of vessel-sealing technology allows the surgeon to skeletonize the uterine arteries while allowing progressive descensus to secure the upper pedicles.

In my experience, the use of an advanced vessel-sealing device, compared with traditional clamp-cut-tying technique, facilitated successful completion of vaginal hysterectomy in 650 patients with relative contraindications to the vaginal approach, such as nulliparity, a uterus weighing more than 250 g, and a history of cesarean delivery (Mayo Clinic data; yet unpublished).

We must change with the times

The rate of vaginal hysterectomy will continue to decline unless we modify our technique to incorporate new technology. The current generation of practicing gynecologists and recent graduates are choosing the laparoscopic and robotic approaches because of the advantages these technologies offer. It is time we incorporate relevant features from these minimally invasive approaches while maintaining patient safety and containing costs by performing vaginal hysterectomy whenever possible. A willingness to change and ability to think outside the usual box will help us train new generations of vaginal surgeons who can bring back vaginal hysterectomy as the preferred route to the benign hysterectomy.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD003677.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 444: Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(5):1156–1158.

3. Wright T, Herzog T, Tsul J, et al. Nationwide trends in inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013:122(2):233–241.

4. Rogo-Gupta L, Lewyn S, Jum JH, et al. Effect of surgeon volume on outcomes and resource use for vaginal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1341–1347.

5. Wright KN, Jonsdottir GM, Jorgensen S, Shah N, Einarsson JI. Costs and outcomes of abdominal, vaginal, laparoscopic and robotic hysterectomies. JSLS. 2012;16(4):519–524.

6. Washburn EE, Cohen SL, Manoucherie E, Zurawin, RJ, Einarsson JI. Trends in reported residency surgical experience in hysterectomy [published online ahead of print June 4, 2014]. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2014.05.005.

7. Burkett D, Horwitz J, Kennedy V, et al. Assessing current trends in resident hysterectomy training. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17(5):210–214.

8. Kroft J, Selk K. Energy-based vessel sealing in vaginal hysterectomy. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1127–1136.

Vaginal hysterectomy is the preferred route to benign hysterectomy because it is associated with better outcomes and fewer complications than the laparoscopic and open abdominal approaches.1,2 Yet, despite superior patient outcomes and cost benefits, the rate of vaginal hysterectomy is declining.

According to the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, the use of vaginal hysterectomy declined from 24.8% in 1998 to 16.7% in 2010.3 In fact, more than 80% of surgeons in the United States now perform fewer than five vaginal procedures in a year.4

The increasing use of other minimally invasive routes, such as laparoscopy and robotics, indicates that most practicing surgeons and recent graduates are choosing these approaches over the vaginal route. In only 3 years, the rate of laparoscopy increased by 6% and robotics increased by almost 10%.3

Many surgeons assume that vaginal hysterectomy exists in a state of suspended animation, with nothing much changed in the way it has been performed over the past few decades. Further, vaginal surgery is difficult to teach and learn, given limitations in exposure and visualization, difficulty in securing hemostasis, and challenges in the removal of the large uterus and adnexae. As a result, vaginal hysterectomy often is thought, erroneously, to be indicated only in procedures involving a small and prolapsing uterus.

To increase the rate of vaginal hysterectomy, we can benefit from experience gained in laparoscopy and robotics—whether we are teachers or learners—while maintaining patient safety and containing costs.

In this article, I describe common challenges in vaginal hysterectomy and offer tools and techniques to overcome them:

- achieving and enhancing ergonomics, exposure, and visualization

- the need to work in a long vaginal vault

- the task of securing vascular and thick tissue pedicles when the introitus and vaginal vault are narrow.

The vaginal approach is less costly

Vaginal hysterectomy costs significantly less to perform than other approaches. At a tertiary referral center, vaginal hysterectomy costs approximately $7,000 to $18,000 per case less than laparoscopic, abdominal, and robotic hysterectomy.5 With declining use of vaginal hysterectomy and increasing use of more costly approaches, we face a health-care crisis.

Residents are inadequately trained to perform vaginal hysterectomy

Data reveal that not only are our recent graduates inadequately prepared to perform vaginal hysterectomy, but national health-care dollars and resources are depleted when surgeons choose to perform more costly approaches. As a result, many eligible patients end up deprived of the benefits of a single, concealed, and minimally invasive procedure.

The increase in laparoscopic and robotic approaches to hysterectomy has affected residency training. National case log reports from the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education show that the number of vaginal hysterectomies performed by residents as “primary surgeons” decreased by 40%, from a mean of 35 cases in 2002 to 19 cases in 2012.6 A recent survey found that only 28% of graduating residents were “completely prepared” to perform a vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 58% for abdominal hysterectomy, 22% for laparoscopic hysterectomy, and 3% for the robotic approach.7

The rate of vaginal hysterectomy will continue to decline if we perform it in the same manner it was done 30 years ago. The current generation of practicing gynecologists and graduates is choosing to perform the procedure laparoscopically or robotically because of the advantages these technologies provide. It is time that we incorporate features from these minimally invasive approaches to streamline vaginal hysterectomy while maintaining patient safety and containing costs.

Challenges: Ergonomics, exposure, and visualization

In conventional vaginal surgery, the surgeon often is the person who has the best and, sometimes, the sole view. Two bedside assistants are required to hold retractors during the entire case, which can lead to fatigue and muscle strain. Poor lighting also can greatly limit visualization into the pelvic cavity.

Both laparoscopy and robotics provide a well-illuminated and magnified view, with three-dimensional images now available in both platforms. This view is projected to overhead monitors for the entire surgical team to see. Magnification of the pelvic anatomic structures and projection to an external monitor facilitate teaching and learning, better anticipation of the surgical and procedural needs, and overall patient safety.

From robotics, where ergonomics is exemplified, we also learn the importance of surgeon comfort during the procedure.

Solution #1: A self-retaining retractor

A self-retaining system such as the Magrina-Bookwalter vaginal retractor (Symmetry Surgical, Nashville, Tennessee) (FIGURE 1)

Solution #2: Seat the surgeon for an optimal view

With the patient in the lithotomy position and her legs in candy cane stirrups, the surgeon can be seated on a high chair so that the operative field is at the approximate level of the assistants’ view (FIGURE 2)

Solution #3: Illuminate the cavity

The deep pelvic cavity can be easily illuminated using a lighted suction tip, a flexible light source (as part of the cystoscopy set) held with a Babcock clamp (FIGURE 3), or a malleable illuminating mat taped to the retractor blades (such as Lightmat surgical illuminator, Lumitex, Inc., Strongsville, Ohio).

Solution #4: Project the image

Cameras attached to an overhead boom or operating room light handles (FIGURE 4) and an external telescope with integrated illumination, such as a standard cystoscope or VITOM Exoscope (Karl Storz, El Segundo, California) (FIGURE 5) provide both magnification and projection of the procedure to an overhead monitor.

Glass technology (Google, Mountain View, California) also has been utilized in surgery and can be a good application of simultaneous projection and recording of the procedure to an external monitor (FIGURE 6). Google Glass is a wearable computer with an optical head-mounted display. The device, similar to eyeglasses, is voice-activated, thereby allowing the surgeon to record the procedure hands-free. Simultaneous projection to an external monitor allows the entire team in the operating room to be aware of the flow of the procedure.

Challenge: Working in a narrow vaginal vault

Without correct instrumentation, this challenge can be especially daunting. Laparoscopy and robotics have changed the way we perform pelvic surgery by providing advanced instrumentation.

Solution #5: Adapt your instruments

Modified vaginal instruments can be used to facilitate a case. Watch the accompanying VIDEO on the use of improved vaginal instruments during morcellation.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel |

| Click to enlarge >>> |

Among the instruments adaptable for vaginal surgery:

- curving, articulating instruments

- long, curved, and rounded knife handles, which allow for better ergonomics during prolonged morcellation

- modified long retractors and use of a single long vaginal pack provide retraction of loops of bowel and easy access to secure pedicles deep in the pelvis.

All of these instruments are available through Marina Medical in Sunrise, Florida.

Challenge: Securing vascular and thick tissue pediclesA narrow introitus and vaginal vault can be difficult to manage during vaginal surgery. Another challenge is a uterus that is large or deformed by multiple fibroids.

Solution #6: Vaginal incision

A simple superficial 2- to 3-cm incision on the distal posterior aspect of the vaginal wall can widen the introitus and vault to facilitate the procedure (FIGURE 7)

Solution #7: Vessel-sealing tools

The use of energy is integral to laparoscopy and robotics for dissection and securing vessels. In a meta-analysis that included seven randomized controlled trials, advanced vessel-sealing devices proved useful in vaginal surgery by decreasing blood loss and operative time.8

In the setting of a difficult vaginal hysterectomy with a narrow introitus and large uterus, the use of vessel-sealing technology allows the surgeon to skeletonize the uterine arteries while allowing progressive descensus to secure the upper pedicles.

In my experience, the use of an advanced vessel-sealing device, compared with traditional clamp-cut-tying technique, facilitated successful completion of vaginal hysterectomy in 650 patients with relative contraindications to the vaginal approach, such as nulliparity, a uterus weighing more than 250 g, and a history of cesarean delivery (Mayo Clinic data; yet unpublished).

We must change with the times

The rate of vaginal hysterectomy will continue to decline unless we modify our technique to incorporate new technology. The current generation of practicing gynecologists and recent graduates are choosing the laparoscopic and robotic approaches because of the advantages these technologies offer. It is time we incorporate relevant features from these minimally invasive approaches while maintaining patient safety and containing costs by performing vaginal hysterectomy whenever possible. A willingness to change and ability to think outside the usual box will help us train new generations of vaginal surgeons who can bring back vaginal hysterectomy as the preferred route to the benign hysterectomy.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

Vaginal hysterectomy is the preferred route to benign hysterectomy because it is associated with better outcomes and fewer complications than the laparoscopic and open abdominal approaches.1,2 Yet, despite superior patient outcomes and cost benefits, the rate of vaginal hysterectomy is declining.

According to the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, the use of vaginal hysterectomy declined from 24.8% in 1998 to 16.7% in 2010.3 In fact, more than 80% of surgeons in the United States now perform fewer than five vaginal procedures in a year.4

The increasing use of other minimally invasive routes, such as laparoscopy and robotics, indicates that most practicing surgeons and recent graduates are choosing these approaches over the vaginal route. In only 3 years, the rate of laparoscopy increased by 6% and robotics increased by almost 10%.3

Many surgeons assume that vaginal hysterectomy exists in a state of suspended animation, with nothing much changed in the way it has been performed over the past few decades. Further, vaginal surgery is difficult to teach and learn, given limitations in exposure and visualization, difficulty in securing hemostasis, and challenges in the removal of the large uterus and adnexae. As a result, vaginal hysterectomy often is thought, erroneously, to be indicated only in procedures involving a small and prolapsing uterus.

To increase the rate of vaginal hysterectomy, we can benefit from experience gained in laparoscopy and robotics—whether we are teachers or learners—while maintaining patient safety and containing costs.

In this article, I describe common challenges in vaginal hysterectomy and offer tools and techniques to overcome them:

- achieving and enhancing ergonomics, exposure, and visualization

- the need to work in a long vaginal vault

- the task of securing vascular and thick tissue pedicles when the introitus and vaginal vault are narrow.

The vaginal approach is less costly

Vaginal hysterectomy costs significantly less to perform than other approaches. At a tertiary referral center, vaginal hysterectomy costs approximately $7,000 to $18,000 per case less than laparoscopic, abdominal, and robotic hysterectomy.5 With declining use of vaginal hysterectomy and increasing use of more costly approaches, we face a health-care crisis.

Residents are inadequately trained to perform vaginal hysterectomy

Data reveal that not only are our recent graduates inadequately prepared to perform vaginal hysterectomy, but national health-care dollars and resources are depleted when surgeons choose to perform more costly approaches. As a result, many eligible patients end up deprived of the benefits of a single, concealed, and minimally invasive procedure.

The increase in laparoscopic and robotic approaches to hysterectomy has affected residency training. National case log reports from the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education show that the number of vaginal hysterectomies performed by residents as “primary surgeons” decreased by 40%, from a mean of 35 cases in 2002 to 19 cases in 2012.6 A recent survey found that only 28% of graduating residents were “completely prepared” to perform a vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 58% for abdominal hysterectomy, 22% for laparoscopic hysterectomy, and 3% for the robotic approach.7

The rate of vaginal hysterectomy will continue to decline if we perform it in the same manner it was done 30 years ago. The current generation of practicing gynecologists and graduates is choosing to perform the procedure laparoscopically or robotically because of the advantages these technologies provide. It is time that we incorporate features from these minimally invasive approaches to streamline vaginal hysterectomy while maintaining patient safety and containing costs.

Challenges: Ergonomics, exposure, and visualization

In conventional vaginal surgery, the surgeon often is the person who has the best and, sometimes, the sole view. Two bedside assistants are required to hold retractors during the entire case, which can lead to fatigue and muscle strain. Poor lighting also can greatly limit visualization into the pelvic cavity.

Both laparoscopy and robotics provide a well-illuminated and magnified view, with three-dimensional images now available in both platforms. This view is projected to overhead monitors for the entire surgical team to see. Magnification of the pelvic anatomic structures and projection to an external monitor facilitate teaching and learning, better anticipation of the surgical and procedural needs, and overall patient safety.

From robotics, where ergonomics is exemplified, we also learn the importance of surgeon comfort during the procedure.

Solution #1: A self-retaining retractor

A self-retaining system such as the Magrina-Bookwalter vaginal retractor (Symmetry Surgical, Nashville, Tennessee) (FIGURE 1)

Solution #2: Seat the surgeon for an optimal view

With the patient in the lithotomy position and her legs in candy cane stirrups, the surgeon can be seated on a high chair so that the operative field is at the approximate level of the assistants’ view (FIGURE 2)

Solution #3: Illuminate the cavity

The deep pelvic cavity can be easily illuminated using a lighted suction tip, a flexible light source (as part of the cystoscopy set) held with a Babcock clamp (FIGURE 3), or a malleable illuminating mat taped to the retractor blades (such as Lightmat surgical illuminator, Lumitex, Inc., Strongsville, Ohio).

Solution #4: Project the image

Cameras attached to an overhead boom or operating room light handles (FIGURE 4) and an external telescope with integrated illumination, such as a standard cystoscope or VITOM Exoscope (Karl Storz, El Segundo, California) (FIGURE 5) provide both magnification and projection of the procedure to an overhead monitor.

Glass technology (Google, Mountain View, California) also has been utilized in surgery and can be a good application of simultaneous projection and recording of the procedure to an external monitor (FIGURE 6). Google Glass is a wearable computer with an optical head-mounted display. The device, similar to eyeglasses, is voice-activated, thereby allowing the surgeon to record the procedure hands-free. Simultaneous projection to an external monitor allows the entire team in the operating room to be aware of the flow of the procedure.

Challenge: Working in a narrow vaginal vault

Without correct instrumentation, this challenge can be especially daunting. Laparoscopy and robotics have changed the way we perform pelvic surgery by providing advanced instrumentation.

Solution #5: Adapt your instruments

Modified vaginal instruments can be used to facilitate a case. Watch the accompanying VIDEO on the use of improved vaginal instruments during morcellation.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel |

| Click to enlarge >>> |

Among the instruments adaptable for vaginal surgery:

- curving, articulating instruments

- long, curved, and rounded knife handles, which allow for better ergonomics during prolonged morcellation

- modified long retractors and use of a single long vaginal pack provide retraction of loops of bowel and easy access to secure pedicles deep in the pelvis.

All of these instruments are available through Marina Medical in Sunrise, Florida.

Challenge: Securing vascular and thick tissue pediclesA narrow introitus and vaginal vault can be difficult to manage during vaginal surgery. Another challenge is a uterus that is large or deformed by multiple fibroids.

Solution #6: Vaginal incision

A simple superficial 2- to 3-cm incision on the distal posterior aspect of the vaginal wall can widen the introitus and vault to facilitate the procedure (FIGURE 7)

Solution #7: Vessel-sealing tools

The use of energy is integral to laparoscopy and robotics for dissection and securing vessels. In a meta-analysis that included seven randomized controlled trials, advanced vessel-sealing devices proved useful in vaginal surgery by decreasing blood loss and operative time.8

In the setting of a difficult vaginal hysterectomy with a narrow introitus and large uterus, the use of vessel-sealing technology allows the surgeon to skeletonize the uterine arteries while allowing progressive descensus to secure the upper pedicles.

In my experience, the use of an advanced vessel-sealing device, compared with traditional clamp-cut-tying technique, facilitated successful completion of vaginal hysterectomy in 650 patients with relative contraindications to the vaginal approach, such as nulliparity, a uterus weighing more than 250 g, and a history of cesarean delivery (Mayo Clinic data; yet unpublished).

We must change with the times

The rate of vaginal hysterectomy will continue to decline unless we modify our technique to incorporate new technology. The current generation of practicing gynecologists and recent graduates are choosing the laparoscopic and robotic approaches because of the advantages these technologies offer. It is time we incorporate relevant features from these minimally invasive approaches while maintaining patient safety and containing costs by performing vaginal hysterectomy whenever possible. A willingness to change and ability to think outside the usual box will help us train new generations of vaginal surgeons who can bring back vaginal hysterectomy as the preferred route to the benign hysterectomy.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD003677.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 444: Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(5):1156–1158.

3. Wright T, Herzog T, Tsul J, et al. Nationwide trends in inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013:122(2):233–241.

4. Rogo-Gupta L, Lewyn S, Jum JH, et al. Effect of surgeon volume on outcomes and resource use for vaginal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1341–1347.

5. Wright KN, Jonsdottir GM, Jorgensen S, Shah N, Einarsson JI. Costs and outcomes of abdominal, vaginal, laparoscopic and robotic hysterectomies. JSLS. 2012;16(4):519–524.

6. Washburn EE, Cohen SL, Manoucherie E, Zurawin, RJ, Einarsson JI. Trends in reported residency surgical experience in hysterectomy [published online ahead of print June 4, 2014]. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2014.05.005.

7. Burkett D, Horwitz J, Kennedy V, et al. Assessing current trends in resident hysterectomy training. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17(5):210–214.

8. Kroft J, Selk K. Energy-based vessel sealing in vaginal hysterectomy. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1127–1136.

1. Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD003677.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 444: Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(5):1156–1158.

3. Wright T, Herzog T, Tsul J, et al. Nationwide trends in inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013:122(2):233–241.

4. Rogo-Gupta L, Lewyn S, Jum JH, et al. Effect of surgeon volume on outcomes and resource use for vaginal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1341–1347.

5. Wright KN, Jonsdottir GM, Jorgensen S, Shah N, Einarsson JI. Costs and outcomes of abdominal, vaginal, laparoscopic and robotic hysterectomies. JSLS. 2012;16(4):519–524.

6. Washburn EE, Cohen SL, Manoucherie E, Zurawin, RJ, Einarsson JI. Trends in reported residency surgical experience in hysterectomy [published online ahead of print June 4, 2014]. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2014.05.005.

7. Burkett D, Horwitz J, Kennedy V, et al. Assessing current trends in resident hysterectomy training. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17(5):210–214.

8. Kroft J, Selk K. Energy-based vessel sealing in vaginal hysterectomy. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1127–1136.

![]()

Dr. Kho presents vaginal morcellation by hand, using advanced instrumentation

Does prenatal acetaminophen exposure increase the risk of behavioral problems in the child?

In the continuing drive to determine the cause of neurobehavioral complications, particularly ADHD and HKD, a number of studies have reported associations with various substances. These include pesticides,1 hormones,2 hormone disrupters,1 and, possibly, genetics. Nevertheless, the etiology of these disorders remains a mystery. ADHD is a complex and heterogeneous disorder. Although we do not yet understand the cause, genetics (or, more accurately, pharmacogenetics) seems likely to play a role.

This study from a large Danish population appears to suggest that the prenatal use of acetaminophen may increase the risk of ADHD and HKD. It is yet another study in which the data indicate and the authors claim that use of a particular drug during pregnancy is responsible for this condition. However, despite the extremely large sample size (which increases the likelihood of positive findings), the hazard ratios were only marginally significant, suggesting that the relevance of the conclusions is questionable.

Details of the study

The 64,322 live-born children and mothers in the Danish National Birth Cohort from 1996 to 2002 were evaluated three ways:

- through parental reports of behavioral problems in children at age 7 using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- through retrieval of HKD diagnoses from the Danish National Hospital Registry or the Danish Psychiatric Central Registry prior to 2011

- through prescriptions for ADHD (primarily methylphenidate [Ritalin]) for children from the Danish Prescription Registry.

Liew and colleagues then estimated hazard ratios for receiving a diagnosis of HKD or using a medication for ADHD, as well as risk ratios for behavioral problems in children after prenatal exposure to acetaminophen.

Stronger associations between prenatal acetaminophen use and HKD or ADHD were found when the mother used the medication in more than one trimester. Exposure-response trends increased with the frequency of acetaminophen use during pregnancy for all three outcomes (HKD diagnosis, ADHD-like behaviors, and ADHD medication use; P trend <.001). Results did not appear to be confounded by maternal inflammation, infection during pregnancy, or the mother’s mental health status.

Related articles:

• How can pregnant women safely relieve low-back pain? Roselyn Jan W. Clemente-Fuentes, MD; Heather Pickett, DO; Misty Carney, MLIS; and Paul Crawford, MD (January 2014)

• Perinatal depression: What you can do to reduce its long-term effects. Janelle Yates (February 2014)

• Low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia prevention: Ready for prime time, but as a “re-run” or as a “new series”? John T. Repke, MD (Guest Editorial; June 2014)

Why these findings are less than compelling

Acetaminophen is the most commonly used medication during pregnancy, although few investigators have analyzed neurobehavioral complications in children exposed to this drug in utero. Another recent epidemiologic study from Norway also suggests that long-term exposure (>28 days) to acetaminophen increases the risk of poor gross motor functioning, poor communication skills, and externalizing and internalizing behavior problems.3

The rationale behind an association between acetaminophen and ADHD and HKD is that the medication is an endocrine-disrupting agent. The evidence of this status comes primarily from in vitro experiments from one group of researchers, which may not represent in vivo conditions.4,5

Epidemiologic studies frequently are confounded by poor design and methodology. It also should be noted that correlation is not necessarily the same as causation. In this study, the design and methodology were appropriate considering the data available. Researchers often use large databases like this to research “hot topics” such as the association between ADHD and prenatal acetaminophen use. In this study, acetaminophen cannot be associated definitively with an increased risk of ADHD or HKD. Further research is needed, with greater attention to possible confounding factors, such as why these women consumed chronic doses and for what conditions.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

For the time being, you should probably counsel your patients to use acetaminophen sparingly during pregnancy, and certainly not on a daily basis. We also should encourage nonpharmacologic pain management, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, when appropriate, and caution patients against long-term use of analgesics, when possible, during gestation and lactation.

Thomas W. Hale, RPH, PhD; Aarienne Einarson, RN; and Teresa Baker, MD

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. Kajta M, Wojtowicz AK. Impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on neural development and the onset of neurological disorders. Pharmacol Rep. 2013;65(6):1632–1639.

2. de Bruin EI, Verheij F, Wiegman T, Ferdinand RF. Differences in finger length ratio between males with autism, pervasive developmental disorder–not otherwise specified, ADHD, and anxiety disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(12):962–965.

3. Brandlistuen RE, Ystrom E, Nulman I, Koren G, Nordeng H. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: A sibling-controlled cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(6):1702–1713.

4. Kristensen DM, Lesne L, Le Fol V, et al. Paracetamol (acetaminophen), aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), and indomethacin are anti-androgenic in the rat foetal testis. Int J Androl. 2012;35(3):377–384.

5. Albert O, Desdoits-Lethimonier C, Lesne L, et al. Paracetamol, aspirin, and indomethacin display endocrine disrupting properties in the adult human testis in vitro. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(7):1890–1898.

In the continuing drive to determine the cause of neurobehavioral complications, particularly ADHD and HKD, a number of studies have reported associations with various substances. These include pesticides,1 hormones,2 hormone disrupters,1 and, possibly, genetics. Nevertheless, the etiology of these disorders remains a mystery. ADHD is a complex and heterogeneous disorder. Although we do not yet understand the cause, genetics (or, more accurately, pharmacogenetics) seems likely to play a role.

This study from a large Danish population appears to suggest that the prenatal use of acetaminophen may increase the risk of ADHD and HKD. It is yet another study in which the data indicate and the authors claim that use of a particular drug during pregnancy is responsible for this condition. However, despite the extremely large sample size (which increases the likelihood of positive findings), the hazard ratios were only marginally significant, suggesting that the relevance of the conclusions is questionable.

Details of the study

The 64,322 live-born children and mothers in the Danish National Birth Cohort from 1996 to 2002 were evaluated three ways:

- through parental reports of behavioral problems in children at age 7 using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- through retrieval of HKD diagnoses from the Danish National Hospital Registry or the Danish Psychiatric Central Registry prior to 2011

- through prescriptions for ADHD (primarily methylphenidate [Ritalin]) for children from the Danish Prescription Registry.

Liew and colleagues then estimated hazard ratios for receiving a diagnosis of HKD or using a medication for ADHD, as well as risk ratios for behavioral problems in children after prenatal exposure to acetaminophen.

Stronger associations between prenatal acetaminophen use and HKD or ADHD were found when the mother used the medication in more than one trimester. Exposure-response trends increased with the frequency of acetaminophen use during pregnancy for all three outcomes (HKD diagnosis, ADHD-like behaviors, and ADHD medication use; P trend <.001). Results did not appear to be confounded by maternal inflammation, infection during pregnancy, or the mother’s mental health status.

Related articles:

• How can pregnant women safely relieve low-back pain? Roselyn Jan W. Clemente-Fuentes, MD; Heather Pickett, DO; Misty Carney, MLIS; and Paul Crawford, MD (January 2014)

• Perinatal depression: What you can do to reduce its long-term effects. Janelle Yates (February 2014)

• Low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia prevention: Ready for prime time, but as a “re-run” or as a “new series”? John T. Repke, MD (Guest Editorial; June 2014)

Why these findings are less than compelling

Acetaminophen is the most commonly used medication during pregnancy, although few investigators have analyzed neurobehavioral complications in children exposed to this drug in utero. Another recent epidemiologic study from Norway also suggests that long-term exposure (>28 days) to acetaminophen increases the risk of poor gross motor functioning, poor communication skills, and externalizing and internalizing behavior problems.3

The rationale behind an association between acetaminophen and ADHD and HKD is that the medication is an endocrine-disrupting agent. The evidence of this status comes primarily from in vitro experiments from one group of researchers, which may not represent in vivo conditions.4,5

Epidemiologic studies frequently are confounded by poor design and methodology. It also should be noted that correlation is not necessarily the same as causation. In this study, the design and methodology were appropriate considering the data available. Researchers often use large databases like this to research “hot topics” such as the association between ADHD and prenatal acetaminophen use. In this study, acetaminophen cannot be associated definitively with an increased risk of ADHD or HKD. Further research is needed, with greater attention to possible confounding factors, such as why these women consumed chronic doses and for what conditions.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

For the time being, you should probably counsel your patients to use acetaminophen sparingly during pregnancy, and certainly not on a daily basis. We also should encourage nonpharmacologic pain management, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, when appropriate, and caution patients against long-term use of analgesics, when possible, during gestation and lactation.

Thomas W. Hale, RPH, PhD; Aarienne Einarson, RN; and Teresa Baker, MD

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

In the continuing drive to determine the cause of neurobehavioral complications, particularly ADHD and HKD, a number of studies have reported associations with various substances. These include pesticides,1 hormones,2 hormone disrupters,1 and, possibly, genetics. Nevertheless, the etiology of these disorders remains a mystery. ADHD is a complex and heterogeneous disorder. Although we do not yet understand the cause, genetics (or, more accurately, pharmacogenetics) seems likely to play a role.

This study from a large Danish population appears to suggest that the prenatal use of acetaminophen may increase the risk of ADHD and HKD. It is yet another study in which the data indicate and the authors claim that use of a particular drug during pregnancy is responsible for this condition. However, despite the extremely large sample size (which increases the likelihood of positive findings), the hazard ratios were only marginally significant, suggesting that the relevance of the conclusions is questionable.

Details of the study

The 64,322 live-born children and mothers in the Danish National Birth Cohort from 1996 to 2002 were evaluated three ways:

- through parental reports of behavioral problems in children at age 7 using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- through retrieval of HKD diagnoses from the Danish National Hospital Registry or the Danish Psychiatric Central Registry prior to 2011

- through prescriptions for ADHD (primarily methylphenidate [Ritalin]) for children from the Danish Prescription Registry.

Liew and colleagues then estimated hazard ratios for receiving a diagnosis of HKD or using a medication for ADHD, as well as risk ratios for behavioral problems in children after prenatal exposure to acetaminophen.

Stronger associations between prenatal acetaminophen use and HKD or ADHD were found when the mother used the medication in more than one trimester. Exposure-response trends increased with the frequency of acetaminophen use during pregnancy for all three outcomes (HKD diagnosis, ADHD-like behaviors, and ADHD medication use; P trend <.001). Results did not appear to be confounded by maternal inflammation, infection during pregnancy, or the mother’s mental health status.

Related articles:

• How can pregnant women safely relieve low-back pain? Roselyn Jan W. Clemente-Fuentes, MD; Heather Pickett, DO; Misty Carney, MLIS; and Paul Crawford, MD (January 2014)

• Perinatal depression: What you can do to reduce its long-term effects. Janelle Yates (February 2014)

• Low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia prevention: Ready for prime time, but as a “re-run” or as a “new series”? John T. Repke, MD (Guest Editorial; June 2014)

Why these findings are less than compelling

Acetaminophen is the most commonly used medication during pregnancy, although few investigators have analyzed neurobehavioral complications in children exposed to this drug in utero. Another recent epidemiologic study from Norway also suggests that long-term exposure (>28 days) to acetaminophen increases the risk of poor gross motor functioning, poor communication skills, and externalizing and internalizing behavior problems.3

The rationale behind an association between acetaminophen and ADHD and HKD is that the medication is an endocrine-disrupting agent. The evidence of this status comes primarily from in vitro experiments from one group of researchers, which may not represent in vivo conditions.4,5

Epidemiologic studies frequently are confounded by poor design and methodology. It also should be noted that correlation is not necessarily the same as causation. In this study, the design and methodology were appropriate considering the data available. Researchers often use large databases like this to research “hot topics” such as the association between ADHD and prenatal acetaminophen use. In this study, acetaminophen cannot be associated definitively with an increased risk of ADHD or HKD. Further research is needed, with greater attention to possible confounding factors, such as why these women consumed chronic doses and for what conditions.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

For the time being, you should probably counsel your patients to use acetaminophen sparingly during pregnancy, and certainly not on a daily basis. We also should encourage nonpharmacologic pain management, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, when appropriate, and caution patients against long-term use of analgesics, when possible, during gestation and lactation.

Thomas W. Hale, RPH, PhD; Aarienne Einarson, RN; and Teresa Baker, MD

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. Kajta M, Wojtowicz AK. Impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on neural development and the onset of neurological disorders. Pharmacol Rep. 2013;65(6):1632–1639.

2. de Bruin EI, Verheij F, Wiegman T, Ferdinand RF. Differences in finger length ratio between males with autism, pervasive developmental disorder–not otherwise specified, ADHD, and anxiety disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(12):962–965.

3. Brandlistuen RE, Ystrom E, Nulman I, Koren G, Nordeng H. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: A sibling-controlled cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(6):1702–1713.

4. Kristensen DM, Lesne L, Le Fol V, et al. Paracetamol (acetaminophen), aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), and indomethacin are anti-androgenic in the rat foetal testis. Int J Androl. 2012;35(3):377–384.

5. Albert O, Desdoits-Lethimonier C, Lesne L, et al. Paracetamol, aspirin, and indomethacin display endocrine disrupting properties in the adult human testis in vitro. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(7):1890–1898.

1. Kajta M, Wojtowicz AK. Impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on neural development and the onset of neurological disorders. Pharmacol Rep. 2013;65(6):1632–1639.

2. de Bruin EI, Verheij F, Wiegman T, Ferdinand RF. Differences in finger length ratio between males with autism, pervasive developmental disorder–not otherwise specified, ADHD, and anxiety disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(12):962–965.

3. Brandlistuen RE, Ystrom E, Nulman I, Koren G, Nordeng H. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: A sibling-controlled cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(6):1702–1713.

4. Kristensen DM, Lesne L, Le Fol V, et al. Paracetamol (acetaminophen), aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), and indomethacin are anti-androgenic in the rat foetal testis. Int J Androl. 2012;35(3):377–384.

5. Albert O, Desdoits-Lethimonier C, Lesne L, et al. Paracetamol, aspirin, and indomethacin display endocrine disrupting properties in the adult human testis in vitro. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(7):1890–1898.

Low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia prevention: Ready for prime time, but as a “re-run” or as a “new series”?

In November 2013, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published the results of its Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy.1 The Task Force aimed to help clinicians become familiar with the state of research in hypertension during pregnancy as well as to assist us in standardizing management approaches to such patients.

The Task Force reported that, worldwide, hypertensive disorders complicate approximately 10% of pregnancies. In addition, in the United States, the past 20 years have brought a 25% increase in the incidence of preeclampsia. According to past ACOG President James N. Martin, Jr, MD, in the last 10 years, the pathophysiology of preeclampsia has become better understood, but the etiology remains unclear and evidence that has emerged to guide therapy has not translated into clinical practice.1

Related articles:

The latest guidance from ACOG on hypertension in pregnancy. Jaimey E. Pauli, MD (Audiocast, January 2014)

Update on Obstetrics. Jaimey E. Pauli, MD, and John T. Repke, MD (January 2014)

The Task Force document contained 60 recommendations for the prevention, prediction, and management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, HELLP syndrome, and preeclampsia superimposed on an underlying hypertensive disorder (see box below). One recommendation was that women at high risk for preeclampsia, particularly those with a history of preeclampsia that required delivery before 34 weeks, could possibly benefit from taking aspirin (60–81 mg) daily starting at the end of the first trimester. They further noted that this benefit could include prevention of recurrent severe preeclampsia, or at least a reduction in recurrence risk.

The ACOG Task Force made its recommendation based on results of a meta-analysis of low-dose aspirin trials, involving more than 30,000 patients,2 suggesting a small decrease in the risk of preeclampsia and associated morbidity. More precise risk reduction estimates were difficult to make due to the heterogeneity of the studies reviewed. And the Task Force further stated that this (low-dose aspirin) approach had no demonstrable acute adverse fetal effects, although long-term adverse effects could not be entirely excluded based on the current data.

Unfortunately, according to the ACOG document, the strength of the evidence supporting their recommendation was “moderate” and the strength of the recommendation was “qualified” so, not exactly a resounding endorsement of this approach, but a recommendation nonetheless.

OBSTETRIC PRACTICE CHANGERS 2014

Hypertension and pregnancy and preventing the first cesarean delivery

John T. Repke, MD, author of this Guest Editorial, recently sat down with Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, fellow OBG Management Board of Editors Member and author of this month’s "Update on Operative Vaginal Delivery." Their discussion focused on individual takeaways from ACOG’s Hypertension in Pregnancy guidelines and the recent joint ACOG−Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine report on emerging clinical and scientific advances in safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery.

From their conversation:

Dr. Repke: About 60 recommendations came out of ACOG’s Hypertension in Pregnancy document; only six had high-quality supporting evidence, and I think most practitioners already did them. Many really were based on either moderate- or low-quality evidence, with qualified recommendations. I think this has led to confusion.

Dr. Norwitz, how do you answer when a clinician asks you, “Is this gestational hypertension or is this preeclampsia?”

Click here to access the audiocast with full transcript.

Data suggest aspirin for high-risk women could be reasonable

A recent study by Henderson and colleagues presented a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) on the potential for low-dose aspirin to prevent morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia.3 The design was a meta-analysis of 28 studies: two large, multisite, randomized clinical trials (RCTs); 13 smaller RCTs of high-risk women, of which eight were deemed “good quality”; and six RCTs and two observational studies of average-risk women, of which seven were deemed to be good quality.

The results essentially supported the notion that low-dose aspirin had a beneficial effect with respect to prevention of preeclampsia and perinatal morbidity in women at high risk for preeclampsia. Additionally, no harmful effects were identified, although the authors acknowledged potential rare or long-term harm could not be excluded.

Questions remain

While somewhat gratifying, the results of the USPSTF systematic review still leave many questions. First, the dose of aspirin used in the studies analyzed ranged from 50 mg/d to 150 mg/d. In the United States, “low-dose” aspirin is usually prescribed at 81 mg/d, so the applicability of this review’s findings to US clinical practice is not exact. Second, the authors acknowledged that the putative positive effects observed could be secondary to so-called “small study effects,” and that when only the larger studies were analyzed the effects were less impressive.

Related article: A stepwise approach to managing eclampsia and other hypertensive emergencies. Baha M. Sibai (October 2013)

In my opinion, both the USPSTF study and the recommendations from the ACOG Task Force provide some reassurance for clinicians that the use of daily, low-dose aspirin by women at high risk for preeclampsia probably does afford some benefit, and seems to be a safe approach—as we have known from the initial Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) trial published in 1993 on low-risk women4 and the follow-up MFMU study on high-risk women.5

The need for additional studies is clear, however. The idea that preeclampsia is the same in every patient would seem to make no more sense than thinking all cancer is the same, with the same risk factors, the same epidemiology and pathophysiology, and the same response to similar treatments. Fundamentally, we need to further explore the different pathways through which preeclampsia develops in women and then apply the strategy best suited to treating (or preventing) their form of the disease—a personalized medicine approach.

In the meantime, most patients who have delivered at 34 weeks or less because of preeclampsia and who are contemplating another pregnancy are really not interested in hearing us tell them that we cannot do anything to prevent recurrent preeclampsia because we are awaiting further studies. At least the ACOG recommendations and the results of the USPSTF’s systematic review provide us with a reasonable, although perhaps not yet optimal, therapeutic option.

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations to improve outcomes in women who have eclampsia. Baha M. Sibai (November 2011)

The bottom line

In my own practice, I discuss the option of initiating low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) as early as 12 weeks’ gestation for patients who had either prior early-onset preeclampsia requiring delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation or preeclampsia during more than one pregnancy.

QUICK POLL

Do you offer low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention?

When faced with a patient with prior preeclampsia in more than one pregnancy or with preeclampsia that resulted in delivery prior to 34 weeks, do you offer low-dose aspirin as an option for preventing preeclampsia?

Visit the Quick Poll on the right column of the OBGManagement.com home page to register your answer and see how your colleagues voted.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

- ACOG Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122–1131.

- Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Heher S, King JF. Antiplatelet agents for preventing preeclampsia and its complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD004659.

- Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O’Connor E, Senger CA, Thompson JH, Rowland MG. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: A systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [published online ahead of print April 8, 2014]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M13-2844.

- Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Thom E, et al. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin in healthy, nulliparous pregnant women. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(17):1213–1218.

- Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, et al. Low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in women at high risk. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(11):701–705.

In November 2013, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published the results of its Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy.1 The Task Force aimed to help clinicians become familiar with the state of research in hypertension during pregnancy as well as to assist us in standardizing management approaches to such patients.

The Task Force reported that, worldwide, hypertensive disorders complicate approximately 10% of pregnancies. In addition, in the United States, the past 20 years have brought a 25% increase in the incidence of preeclampsia. According to past ACOG President James N. Martin, Jr, MD, in the last 10 years, the pathophysiology of preeclampsia has become better understood, but the etiology remains unclear and evidence that has emerged to guide therapy has not translated into clinical practice.1

Related articles:

The latest guidance from ACOG on hypertension in pregnancy. Jaimey E. Pauli, MD (Audiocast, January 2014)

Update on Obstetrics. Jaimey E. Pauli, MD, and John T. Repke, MD (January 2014)

The Task Force document contained 60 recommendations for the prevention, prediction, and management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, HELLP syndrome, and preeclampsia superimposed on an underlying hypertensive disorder (see box below). One recommendation was that women at high risk for preeclampsia, particularly those with a history of preeclampsia that required delivery before 34 weeks, could possibly benefit from taking aspirin (60–81 mg) daily starting at the end of the first trimester. They further noted that this benefit could include prevention of recurrent severe preeclampsia, or at least a reduction in recurrence risk.

The ACOG Task Force made its recommendation based on results of a meta-analysis of low-dose aspirin trials, involving more than 30,000 patients,2 suggesting a small decrease in the risk of preeclampsia and associated morbidity. More precise risk reduction estimates were difficult to make due to the heterogeneity of the studies reviewed. And the Task Force further stated that this (low-dose aspirin) approach had no demonstrable acute adverse fetal effects, although long-term adverse effects could not be entirely excluded based on the current data.

Unfortunately, according to the ACOG document, the strength of the evidence supporting their recommendation was “moderate” and the strength of the recommendation was “qualified” so, not exactly a resounding endorsement of this approach, but a recommendation nonetheless.

OBSTETRIC PRACTICE CHANGERS 2014

Hypertension and pregnancy and preventing the first cesarean delivery

John T. Repke, MD, author of this Guest Editorial, recently sat down with Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, fellow OBG Management Board of Editors Member and author of this month’s "Update on Operative Vaginal Delivery." Their discussion focused on individual takeaways from ACOG’s Hypertension in Pregnancy guidelines and the recent joint ACOG−Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine report on emerging clinical and scientific advances in safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery.

From their conversation:

Dr. Repke: About 60 recommendations came out of ACOG’s Hypertension in Pregnancy document; only six had high-quality supporting evidence, and I think most practitioners already did them. Many really were based on either moderate- or low-quality evidence, with qualified recommendations. I think this has led to confusion.

Dr. Norwitz, how do you answer when a clinician asks you, “Is this gestational hypertension or is this preeclampsia?”

Click here to access the audiocast with full transcript.

Data suggest aspirin for high-risk women could be reasonable

A recent study by Henderson and colleagues presented a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) on the potential for low-dose aspirin to prevent morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia.3 The design was a meta-analysis of 28 studies: two large, multisite, randomized clinical trials (RCTs); 13 smaller RCTs of high-risk women, of which eight were deemed “good quality”; and six RCTs and two observational studies of average-risk women, of which seven were deemed to be good quality.

The results essentially supported the notion that low-dose aspirin had a beneficial effect with respect to prevention of preeclampsia and perinatal morbidity in women at high risk for preeclampsia. Additionally, no harmful effects were identified, although the authors acknowledged potential rare or long-term harm could not be excluded.

Questions remain

While somewhat gratifying, the results of the USPSTF systematic review still leave many questions. First, the dose of aspirin used in the studies analyzed ranged from 50 mg/d to 150 mg/d. In the United States, “low-dose” aspirin is usually prescribed at 81 mg/d, so the applicability of this review’s findings to US clinical practice is not exact. Second, the authors acknowledged that the putative positive effects observed could be secondary to so-called “small study effects,” and that when only the larger studies were analyzed the effects were less impressive.

Related article: A stepwise approach to managing eclampsia and other hypertensive emergencies. Baha M. Sibai (October 2013)

In my opinion, both the USPSTF study and the recommendations from the ACOG Task Force provide some reassurance for clinicians that the use of daily, low-dose aspirin by women at high risk for preeclampsia probably does afford some benefit, and seems to be a safe approach—as we have known from the initial Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) trial published in 1993 on low-risk women4 and the follow-up MFMU study on high-risk women.5

The need for additional studies is clear, however. The idea that preeclampsia is the same in every patient would seem to make no more sense than thinking all cancer is the same, with the same risk factors, the same epidemiology and pathophysiology, and the same response to similar treatments. Fundamentally, we need to further explore the different pathways through which preeclampsia develops in women and then apply the strategy best suited to treating (or preventing) their form of the disease—a personalized medicine approach.

In the meantime, most patients who have delivered at 34 weeks or less because of preeclampsia and who are contemplating another pregnancy are really not interested in hearing us tell them that we cannot do anything to prevent recurrent preeclampsia because we are awaiting further studies. At least the ACOG recommendations and the results of the USPSTF’s systematic review provide us with a reasonable, although perhaps not yet optimal, therapeutic option.

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations to improve outcomes in women who have eclampsia. Baha M. Sibai (November 2011)

The bottom line

In my own practice, I discuss the option of initiating low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) as early as 12 weeks’ gestation for patients who had either prior early-onset preeclampsia requiring delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation or preeclampsia during more than one pregnancy.

QUICK POLL

Do you offer low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention?

When faced with a patient with prior preeclampsia in more than one pregnancy or with preeclampsia that resulted in delivery prior to 34 weeks, do you offer low-dose aspirin as an option for preventing preeclampsia?

Visit the Quick Poll on the right column of the OBGManagement.com home page to register your answer and see how your colleagues voted.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

In November 2013, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published the results of its Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy.1 The Task Force aimed to help clinicians become familiar with the state of research in hypertension during pregnancy as well as to assist us in standardizing management approaches to such patients.

The Task Force reported that, worldwide, hypertensive disorders complicate approximately 10% of pregnancies. In addition, in the United States, the past 20 years have brought a 25% increase in the incidence of preeclampsia. According to past ACOG President James N. Martin, Jr, MD, in the last 10 years, the pathophysiology of preeclampsia has become better understood, but the etiology remains unclear and evidence that has emerged to guide therapy has not translated into clinical practice.1

Related articles:

The latest guidance from ACOG on hypertension in pregnancy. Jaimey E. Pauli, MD (Audiocast, January 2014)

Update on Obstetrics. Jaimey E. Pauli, MD, and John T. Repke, MD (January 2014)

The Task Force document contained 60 recommendations for the prevention, prediction, and management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, HELLP syndrome, and preeclampsia superimposed on an underlying hypertensive disorder (see box below). One recommendation was that women at high risk for preeclampsia, particularly those with a history of preeclampsia that required delivery before 34 weeks, could possibly benefit from taking aspirin (60–81 mg) daily starting at the end of the first trimester. They further noted that this benefit could include prevention of recurrent severe preeclampsia, or at least a reduction in recurrence risk.

The ACOG Task Force made its recommendation based on results of a meta-analysis of low-dose aspirin trials, involving more than 30,000 patients,2 suggesting a small decrease in the risk of preeclampsia and associated morbidity. More precise risk reduction estimates were difficult to make due to the heterogeneity of the studies reviewed. And the Task Force further stated that this (low-dose aspirin) approach had no demonstrable acute adverse fetal effects, although long-term adverse effects could not be entirely excluded based on the current data.

Unfortunately, according to the ACOG document, the strength of the evidence supporting their recommendation was “moderate” and the strength of the recommendation was “qualified” so, not exactly a resounding endorsement of this approach, but a recommendation nonetheless.

OBSTETRIC PRACTICE CHANGERS 2014

Hypertension and pregnancy and preventing the first cesarean delivery

John T. Repke, MD, author of this Guest Editorial, recently sat down with Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, fellow OBG Management Board of Editors Member and author of this month’s "Update on Operative Vaginal Delivery." Their discussion focused on individual takeaways from ACOG’s Hypertension in Pregnancy guidelines and the recent joint ACOG−Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine report on emerging clinical and scientific advances in safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery.

From their conversation:

Dr. Repke: About 60 recommendations came out of ACOG’s Hypertension in Pregnancy document; only six had high-quality supporting evidence, and I think most practitioners already did them. Many really were based on either moderate- or low-quality evidence, with qualified recommendations. I think this has led to confusion.

Dr. Norwitz, how do you answer when a clinician asks you, “Is this gestational hypertension or is this preeclampsia?”

Click here to access the audiocast with full transcript.

Data suggest aspirin for high-risk women could be reasonable

A recent study by Henderson and colleagues presented a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) on the potential for low-dose aspirin to prevent morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia.3 The design was a meta-analysis of 28 studies: two large, multisite, randomized clinical trials (RCTs); 13 smaller RCTs of high-risk women, of which eight were deemed “good quality”; and six RCTs and two observational studies of average-risk women, of which seven were deemed to be good quality.

The results essentially supported the notion that low-dose aspirin had a beneficial effect with respect to prevention of preeclampsia and perinatal morbidity in women at high risk for preeclampsia. Additionally, no harmful effects were identified, although the authors acknowledged potential rare or long-term harm could not be excluded.

Questions remain

While somewhat gratifying, the results of the USPSTF systematic review still leave many questions. First, the dose of aspirin used in the studies analyzed ranged from 50 mg/d to 150 mg/d. In the United States, “low-dose” aspirin is usually prescribed at 81 mg/d, so the applicability of this review’s findings to US clinical practice is not exact. Second, the authors acknowledged that the putative positive effects observed could be secondary to so-called “small study effects,” and that when only the larger studies were analyzed the effects were less impressive.

Related article: A stepwise approach to managing eclampsia and other hypertensive emergencies. Baha M. Sibai (October 2013)

In my opinion, both the USPSTF study and the recommendations from the ACOG Task Force provide some reassurance for clinicians that the use of daily, low-dose aspirin by women at high risk for preeclampsia probably does afford some benefit, and seems to be a safe approach—as we have known from the initial Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) trial published in 1993 on low-risk women4 and the follow-up MFMU study on high-risk women.5

The need for additional studies is clear, however. The idea that preeclampsia is the same in every patient would seem to make no more sense than thinking all cancer is the same, with the same risk factors, the same epidemiology and pathophysiology, and the same response to similar treatments. Fundamentally, we need to further explore the different pathways through which preeclampsia develops in women and then apply the strategy best suited to treating (or preventing) their form of the disease—a personalized medicine approach.

In the meantime, most patients who have delivered at 34 weeks or less because of preeclampsia and who are contemplating another pregnancy are really not interested in hearing us tell them that we cannot do anything to prevent recurrent preeclampsia because we are awaiting further studies. At least the ACOG recommendations and the results of the USPSTF’s systematic review provide us with a reasonable, although perhaps not yet optimal, therapeutic option.

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations to improve outcomes in women who have eclampsia. Baha M. Sibai (November 2011)

The bottom line

In my own practice, I discuss the option of initiating low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) as early as 12 weeks’ gestation for patients who had either prior early-onset preeclampsia requiring delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation or preeclampsia during more than one pregnancy.

QUICK POLL

Do you offer low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention?

When faced with a patient with prior preeclampsia in more than one pregnancy or with preeclampsia that resulted in delivery prior to 34 weeks, do you offer low-dose aspirin as an option for preventing preeclampsia?

Visit the Quick Poll on the right column of the OBGManagement.com home page to register your answer and see how your colleagues voted.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

- ACOG Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122–1131.

- Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Heher S, King JF. Antiplatelet agents for preventing preeclampsia and its complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD004659.

- Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O’Connor E, Senger CA, Thompson JH, Rowland MG. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: A systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [published online ahead of print April 8, 2014]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M13-2844.

- Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Thom E, et al. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin in healthy, nulliparous pregnant women. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(17):1213–1218.

- Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, et al. Low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in women at high risk. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(11):701–705.

- ACOG Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122–1131.

- Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Heher S, King JF. Antiplatelet agents for preventing preeclampsia and its complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD004659.

- Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O’Connor E, Senger CA, Thompson JH, Rowland MG. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: A systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [published online ahead of print April 8, 2014]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M13-2844.

- Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Thom E, et al. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin in healthy, nulliparous pregnant women. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(17):1213–1218.

- Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, et al. Low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in women at high risk. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(11):701–705.

Have you read Dr. Errol R. Norwitz's Update on Operative Vaginal Delivery? Click here to access.

How I am adapting my morcellation practice: Voices from across the country

Hear from:

Michael Baggish, MD (St. Helena, California)

Rupen Baxi, MD (Royal Oak, Michigan)

Jennifer Hollings, MD (Richmond, Virginia)

Gwinnett Ladson, MD (Nashville, Tennessee)

Rich Persino, MD (McHenry, Illinois)

Teresa Tam, MD (Chicago, Illinois)

Yvonne Wolny, MD (Chicago, Illinois)

Hear from:

Michael Baggish, MD (St. Helena, California)

Rupen Baxi, MD (Royal Oak, Michigan)

Jennifer Hollings, MD (Richmond, Virginia)

Gwinnett Ladson, MD (Nashville, Tennessee)

Rich Persino, MD (McHenry, Illinois)

Teresa Tam, MD (Chicago, Illinois)

Yvonne Wolny, MD (Chicago, Illinois)

Hear from:

Michael Baggish, MD (St. Helena, California)