User login

What’s Eating You? Millipede Burns

Clinical Presentation

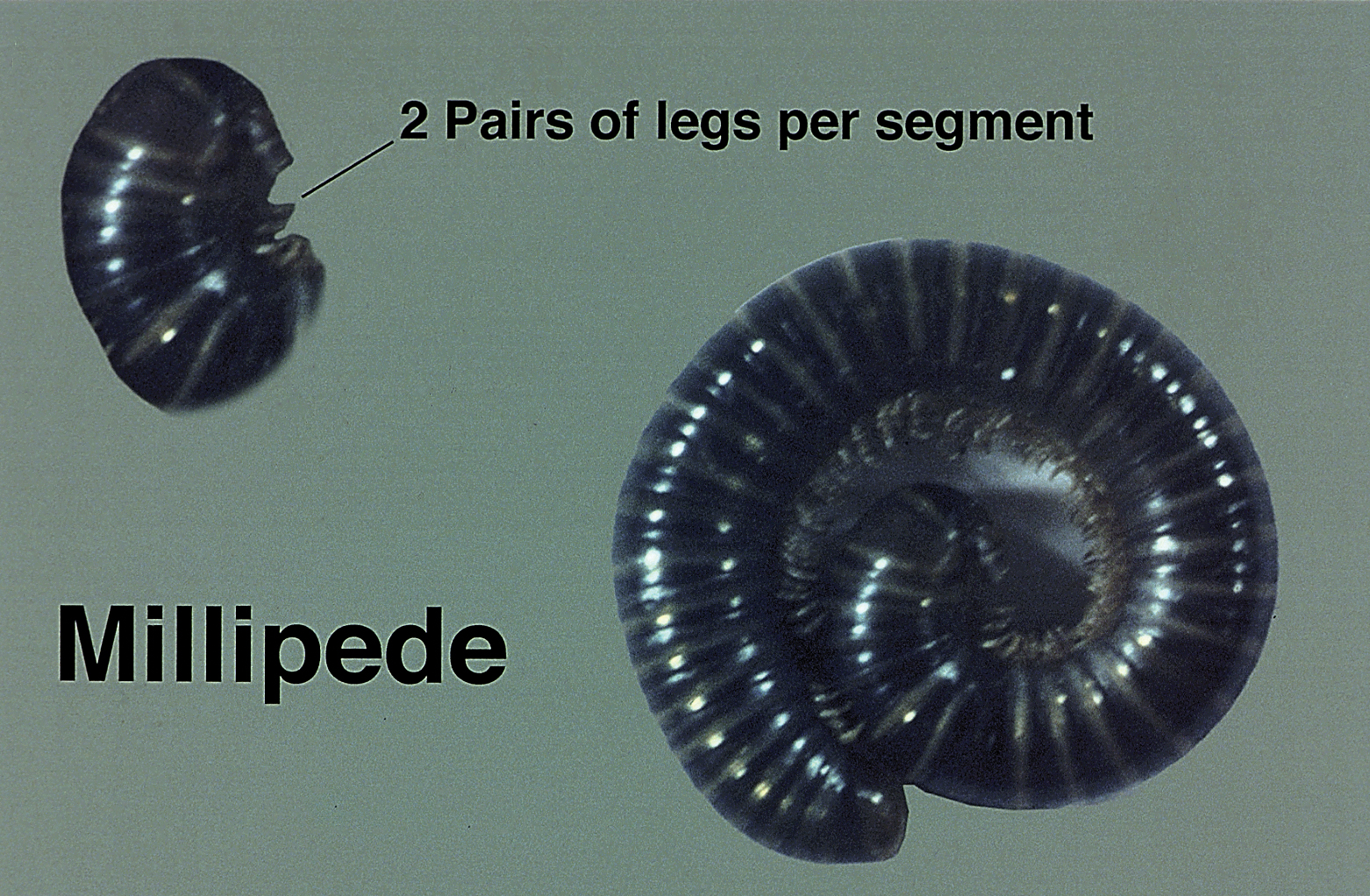

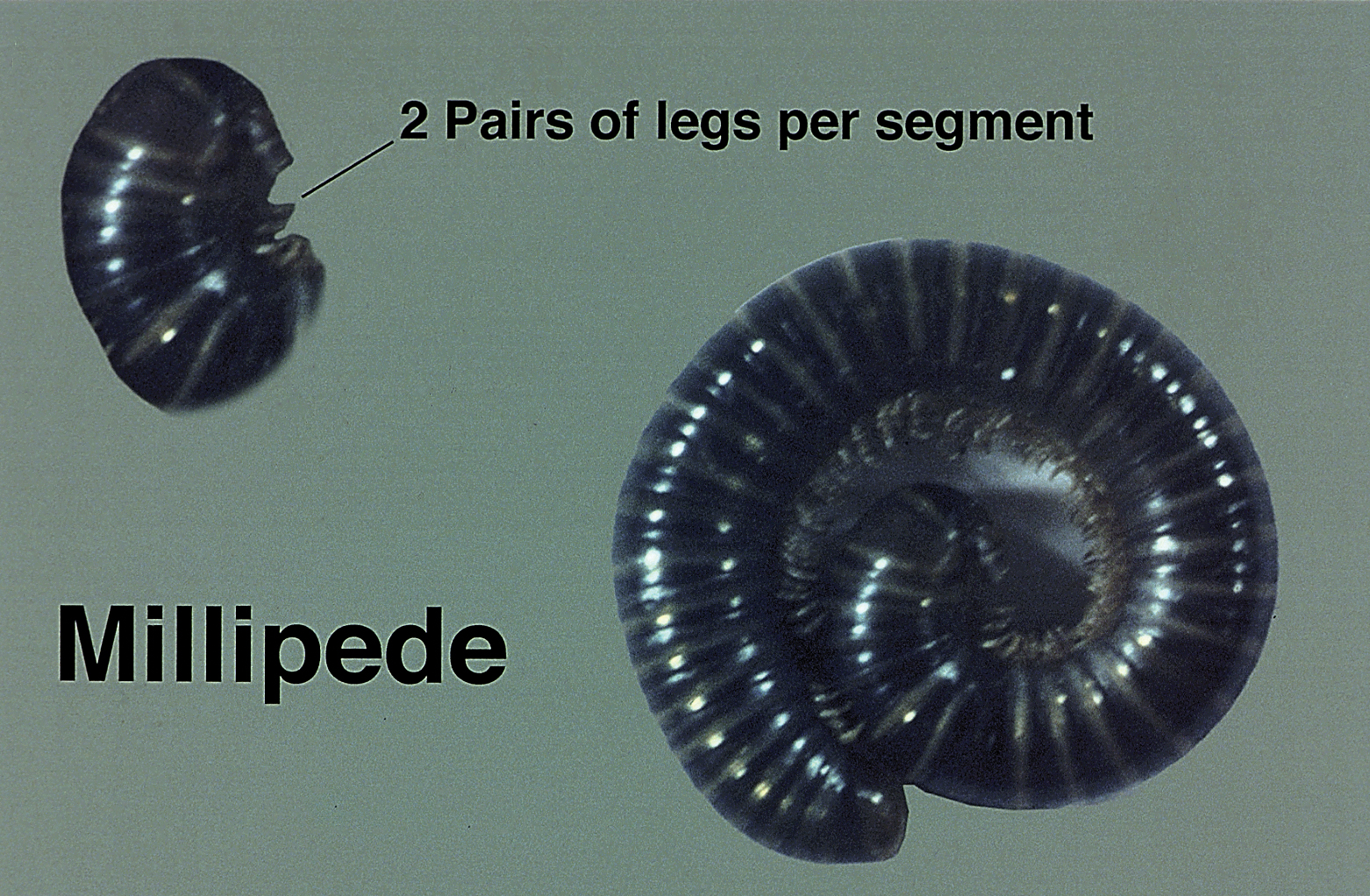

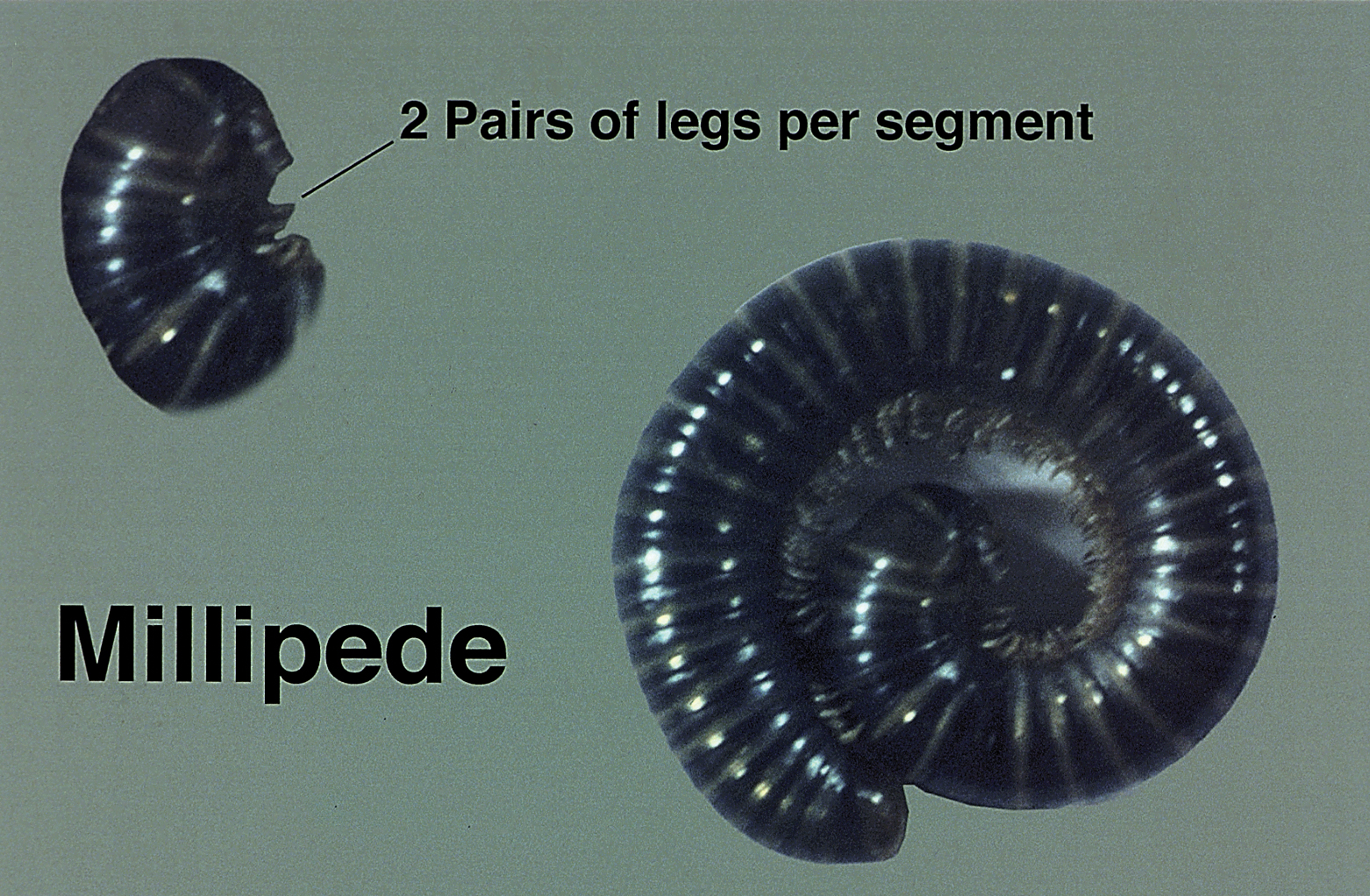

Millipedes secrete a noxious toxin implicated in millipede burns. The toxic substance is benzoquinone, a strong irritant secreted from the repugnatorial glands contained in each segment of the arthropod (Figure 1). This compound serves as a natural insect repellant, acting as the millipede’s defense mechanism from potential predators.1 On human skin, benzoquinone causes localized pigmentary changes most commonly presenting on the feet and toes. Local lesions may be associated with pain or burning, but there are no known reports of adverse systemic effects.2 Affected patients experience cutaneous pigmentary changes, which may be dark red, blue, or black, and spontaneously resolve over time.2 The degree of pigment change may be associated with duration of skin contact with the toxin. The affected areas may resemble burns, dermatitis, or skin necrosis. More distal lesions may present similarly to blue toe syndrome or acute arterial occlusion but can be differentiated by the presence of intact peripheral pulses and lack of temperature discrepancy between the feet.3,4 Histologic evaluation of the lesions generally reveals nonspecific full-thickness epidermal necrosis, making clinical suspicion and physical examination paramount to the diagnosis of millipede burns.5

Diagnostic Difficulties

Accurate diagnosis of millipede burns is more difficult when the burn involves an unusual site. The most common site of involvement is the foot (Figure 2), followed by other commonly exposed areas such as the arms, face, and eyes.2,3,6,7 Covered parts of the body are much less commonly affected, requiring the arthropod to gain access via infiltration of clothing, often when hanging on a clothesline. In these cases, burns may be mistaken for child abuse, especially if certain areas of the body are involved, such as the groin and genitals.2 The well-defined arcuate lesions of the burns may resemble injuries from a wire or belt to the unsuspecting observer.

Conclusion

Although millipedes often are regarded as harmless, they are capable of causing adverse reactions through the secretion of toxic chemicals. Millipede burns cause localized pigmentary changes that may be associated with pain or burning in some patients. Because these burns may resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, physicians should be aware of this diagnosis when unusual parts of the body are involved.

- Kuwahara Y, Omura H, Tanabe T. 2-Nitroethenylbenzenes as naturalproducts in millipede defense secretions. Naturwissenschaften. 2002;89:308-310.

- De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190.

- Heeren Neto AS, Bernardes Filho F, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258.

- Lima CA, Cardoso JL, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda class (“millipedes”). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392.

- Dar NR, Raza N, Rehman SB. Millipede burn at an unusual site mimicking child abuse in an 8-year-old girl. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47:490-492.

- Hendrickson RG. Millipede exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005;43:211-212.

- Verma AK, Bourke B. Millipede burn masquerading as trash foot in a paediatric patient [published online October 29, 2013]. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:388-390.

Clinical Presentation

Millipedes secrete a noxious toxin implicated in millipede burns. The toxic substance is benzoquinone, a strong irritant secreted from the repugnatorial glands contained in each segment of the arthropod (Figure 1). This compound serves as a natural insect repellant, acting as the millipede’s defense mechanism from potential predators.1 On human skin, benzoquinone causes localized pigmentary changes most commonly presenting on the feet and toes. Local lesions may be associated with pain or burning, but there are no known reports of adverse systemic effects.2 Affected patients experience cutaneous pigmentary changes, which may be dark red, blue, or black, and spontaneously resolve over time.2 The degree of pigment change may be associated with duration of skin contact with the toxin. The affected areas may resemble burns, dermatitis, or skin necrosis. More distal lesions may present similarly to blue toe syndrome or acute arterial occlusion but can be differentiated by the presence of intact peripheral pulses and lack of temperature discrepancy between the feet.3,4 Histologic evaluation of the lesions generally reveals nonspecific full-thickness epidermal necrosis, making clinical suspicion and physical examination paramount to the diagnosis of millipede burns.5

Diagnostic Difficulties

Accurate diagnosis of millipede burns is more difficult when the burn involves an unusual site. The most common site of involvement is the foot (Figure 2), followed by other commonly exposed areas such as the arms, face, and eyes.2,3,6,7 Covered parts of the body are much less commonly affected, requiring the arthropod to gain access via infiltration of clothing, often when hanging on a clothesline. In these cases, burns may be mistaken for child abuse, especially if certain areas of the body are involved, such as the groin and genitals.2 The well-defined arcuate lesions of the burns may resemble injuries from a wire or belt to the unsuspecting observer.

Conclusion

Although millipedes often are regarded as harmless, they are capable of causing adverse reactions through the secretion of toxic chemicals. Millipede burns cause localized pigmentary changes that may be associated with pain or burning in some patients. Because these burns may resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, physicians should be aware of this diagnosis when unusual parts of the body are involved.

Clinical Presentation

Millipedes secrete a noxious toxin implicated in millipede burns. The toxic substance is benzoquinone, a strong irritant secreted from the repugnatorial glands contained in each segment of the arthropod (Figure 1). This compound serves as a natural insect repellant, acting as the millipede’s defense mechanism from potential predators.1 On human skin, benzoquinone causes localized pigmentary changes most commonly presenting on the feet and toes. Local lesions may be associated with pain or burning, but there are no known reports of adverse systemic effects.2 Affected patients experience cutaneous pigmentary changes, which may be dark red, blue, or black, and spontaneously resolve over time.2 The degree of pigment change may be associated with duration of skin contact with the toxin. The affected areas may resemble burns, dermatitis, or skin necrosis. More distal lesions may present similarly to blue toe syndrome or acute arterial occlusion but can be differentiated by the presence of intact peripheral pulses and lack of temperature discrepancy between the feet.3,4 Histologic evaluation of the lesions generally reveals nonspecific full-thickness epidermal necrosis, making clinical suspicion and physical examination paramount to the diagnosis of millipede burns.5

Diagnostic Difficulties

Accurate diagnosis of millipede burns is more difficult when the burn involves an unusual site. The most common site of involvement is the foot (Figure 2), followed by other commonly exposed areas such as the arms, face, and eyes.2,3,6,7 Covered parts of the body are much less commonly affected, requiring the arthropod to gain access via infiltration of clothing, often when hanging on a clothesline. In these cases, burns may be mistaken for child abuse, especially if certain areas of the body are involved, such as the groin and genitals.2 The well-defined arcuate lesions of the burns may resemble injuries from a wire or belt to the unsuspecting observer.

Conclusion

Although millipedes often are regarded as harmless, they are capable of causing adverse reactions through the secretion of toxic chemicals. Millipede burns cause localized pigmentary changes that may be associated with pain or burning in some patients. Because these burns may resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, physicians should be aware of this diagnosis when unusual parts of the body are involved.

- Kuwahara Y, Omura H, Tanabe T. 2-Nitroethenylbenzenes as naturalproducts in millipede defense secretions. Naturwissenschaften. 2002;89:308-310.

- De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190.

- Heeren Neto AS, Bernardes Filho F, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258.

- Lima CA, Cardoso JL, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda class (“millipedes”). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392.

- Dar NR, Raza N, Rehman SB. Millipede burn at an unusual site mimicking child abuse in an 8-year-old girl. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47:490-492.

- Hendrickson RG. Millipede exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005;43:211-212.

- Verma AK, Bourke B. Millipede burn masquerading as trash foot in a paediatric patient [published online October 29, 2013]. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:388-390.

- Kuwahara Y, Omura H, Tanabe T. 2-Nitroethenylbenzenes as naturalproducts in millipede defense secretions. Naturwissenschaften. 2002;89:308-310.

- De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190.

- Heeren Neto AS, Bernardes Filho F, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258.

- Lima CA, Cardoso JL, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda class (“millipedes”). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392.

- Dar NR, Raza N, Rehman SB. Millipede burn at an unusual site mimicking child abuse in an 8-year-old girl. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47:490-492.

- Hendrickson RG. Millipede exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005;43:211-212.

- Verma AK, Bourke B. Millipede burn masquerading as trash foot in a paediatric patient [published online October 29, 2013]. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:388-390.

Practice Points

- The most common site of involvement of millipede burns is the foot, followed by other commonly exposed areas such as the arms, face, and eyes. Covered parts of the body are much less commonly affected.

- Millipede burns may resemble child abuse in pediatric patients; therefore, physicians should be aware of this diagnosis when unusual parts of the body are involved.

Aquatic Antagonists: Stingray Injury Update

Incidence and Characteristics

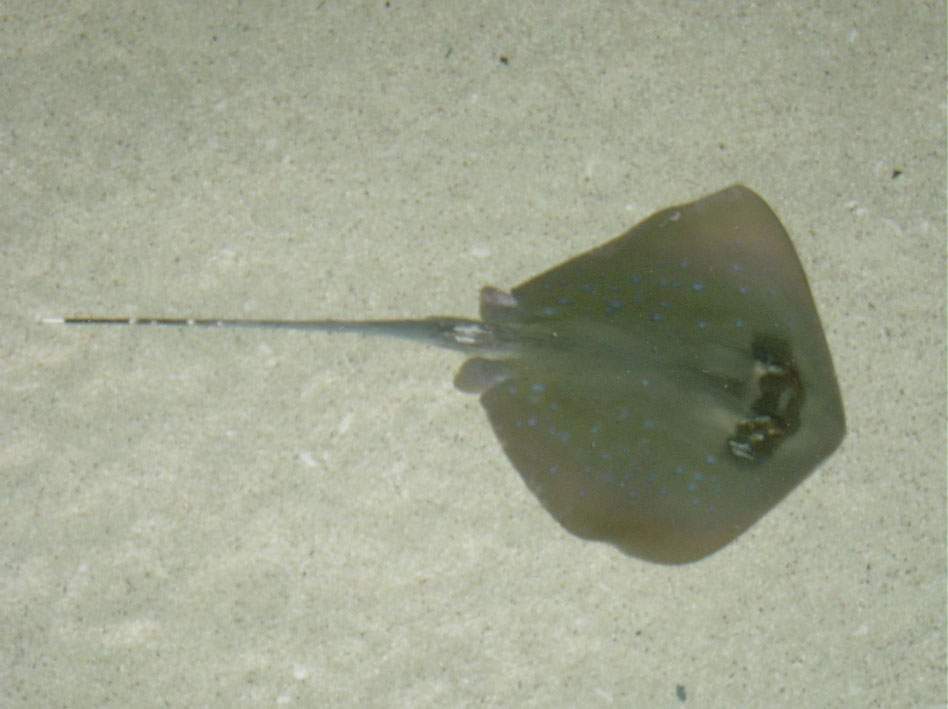

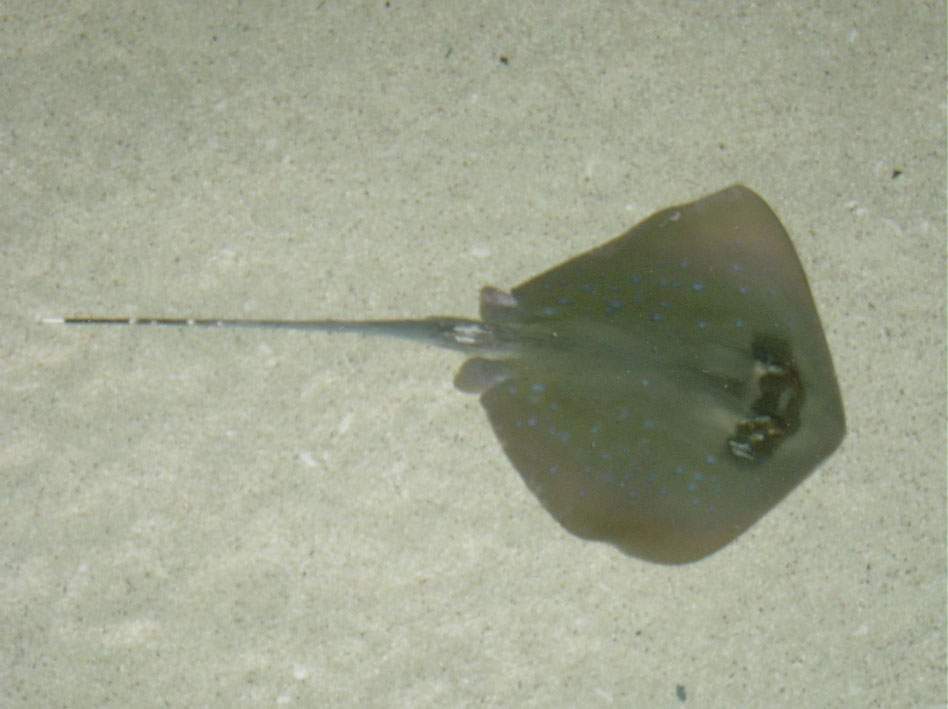

Stingrays are dorsoventrally flattened, diamond-shaped fish with light-colored ventral and dark-colored dorsal surfaces. They have strong pectoral wings that allow them to swim forward and backward and even launch off waves.3 Stingrays range in size from the palm of a human hand to 6.5 ft in width. They possess 1 or more spines (2.5 to >30 cm in length) that are disguised by much longer tails.6,7 They often are encountered accidentally because they bury themselves in the sand or mud of shallow coastal waters or rivers with only their eyes and tails exposed to fool prey and avoid predators.

Injury Clinical Presentation

Stingray injuries typically involve the lower legs, ankles, or feet after stepping on a stingray.8 Fishermen can present with injuries of the upper extremities after handling fish with their hands.9 Other rarer injuries occur when individuals are swimming alongside stingrays or when stingrays catapult off waves into moving boats.10,11 Stingrays impale victims by using their tails to direct a retroserrate barb composed of a strong cartilaginous material called vasodentin. The barb releases venom by breaking through the venom-containing integumentary sheath that encapsulates it. Stingray venom contains phosphodiesterase, serotonin, and 5′-nucleotidase. It causes severe pain, vasoconstriction, ischemia, and poor wound healing, along with systemic effects such as disorientation, syncope, seizures, salivation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle cramps or fasciculations, pruritus, allergic reaction, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, paralysis, and possibly death.1,8,12,13

Management

Pain Relief

As with many marine envenomations, immersion in hot but not scalding water can inactivate venom and reduce symptoms.8,9 In one retrospective review, 52 of 75 (69%) patients reporting to a California poison center with stingray injuries had improvement in pain within 1 hour of hot water immersion before any analgesics were instituted.8 In another review, 65 of 74 (88%) patients presenting to a California emergency department within 24 hours of sustaining a stingray injury had complete relief of pain within 30 minutes of hot water immersion. Patients who received analgesics in addition to hot water immersion did not require a second dose.9 In concordance with these studies, we suggest immersing areas affected by stingray injuries in hot water (temperature, 43.3°C to 46.1°C [110°F–115°F]; or as close to this range as tolerated) until pain subsides.8,9,14 Ice packs are an alternative to hot water immersion that may be more readily available to patients. If pain does not resolve following hot water immersion or application of an ice pack, additional analgesics and xylocaine without epinephrine may be helpful.9,15

Infection

One major complication of stingray injuries is infection.8,9 Many bacterial species reside in stingray mucus, the marine environment, or on human skin that may be introduced during a single injury. Marine envenomations can involve organisms such as Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium species, which often are resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis covering common causes of soft-tissue infection such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.8,9,16,17 Additionally, physicians should cover for Clostridium species and ensure patients are up-to-date on vaccinations because severe cases of tetanus following stingray injuries have been reported.18 Lastly, fungal infections including fusariosis have been reported following stingray injuries and should be considered if a patient develops an infection.19

Several authors support the use of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics in all but mild stingray injuries.8,9,20,21 Although no standardized definition exists, mild injuries generally represent patients with superficial lacerations or less, while deeper lacerations and puncture wounds require prophylaxis. Several authors agree on the use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily) for 5 to 7 days following severe stingray injuries.1,9,13,22 Other proposed antibiotic regimens include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) or tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days.13 Failure of ciprofloxacin therapy after 7 days has been reported, with resolution of infection after treatment with an intravenous cephalosporin for 7 days.20 Failure of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy also has been reported, with one case requiring levofloxacin for a much longer course.21 Clinical follow-up remains essential after prescribing prophylactic antibiotics, as resistance is common.

Foreign Bodies

Stingray injuries also are often complicated by foreign bodies or retained spines.3,8 Although these complications are less severe than infection, all wounds should be explored for material under local anesthesia. Furthermore, there has been support for thorough debridement of necrotic tissue with referral to a hand specialist for deeper injuries to the hands as well as referral to a foot and ankle specialist for deeper injuries of the lower extremities.23,24 More serious injuries with penetration of vital structures, such as through the chest or abdomen, require immediate exploration in an operating room.1,24

Imaging

Routine imaging of stingray injuries remains controversial. In a case series of 119 patients presenting to a California emergency department with stingray injuries, Clark et al9 found that radiographs were not helpful. This finding likely is due in part to an inability to detect hypodense material such as integumentary or glandular tissue via radiography.3 However, radiographs have been used to identify retained stingray barbs in select cases in which retained barbs are suspected.2,25 Lastly, ultrasonography potentially may offer a better first choice when a barb is not readily apparent; magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated for more involved areas and for further visualization of suspected hypodense material, though at a higher expense.2,9

Biopsy

Biopsies of stingray injuries are rarely performed, and the findings are not well characterized. One case biopsied 2 months after injury showed a large zone of paucicellular necrosis with superficial ulceration and granulomatous inflammation. The stingray venom was most likely responsible for the pattern of necrosis noted in the biopsy.21

Avoidance and Prevention

Patients traveling to areas of the world inhabited by stingrays should receive counseling on how to avoid injury. Prior to entry, individuals can throw stones or use a long stick to clear their walking or swimming areas of venomous fish.26 Polarized sunglasses may help spot stingrays in shallow water. Furthermore, wading through water with a shuffling gait can help individuals avoid stepping directly on a stingray and also warns stingrays that someone is in the area. Individuals who spend more time in coastal waters or river systems inhabited by stingrays may invest in protective stingray gear such as leg guards or specialized wading boots.26 Lastly, fishermen should be advised to avoid handling stingrays with their hands and instead cut their fishing line to release the fish.

- Aurbach PS. Envenomations by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerbach PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1730-1749.

- Robins CR, Ray GC. A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1986.

- Diaz JH. The evaluation, management, and prevention of stingray injuries in travelers. J Travel Med. 2008;15:102-109.

- Haddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto JB, et al. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinical and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon. 2004;43:287-294.

- Marinkelle CJ. Accidents by venomous animals in Colombia. Ind Med Surg. 1966;35:988-992.

- Last PR, White WT, Caire JN, et al. Sharks and Rays of Borneo. Collingwood VIC, Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2010.

- Mebs D. Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

- Clark AT, Clark RF, Cantrell FL. A retrospective review of the presentation and treatment of stingray stings reported to a poison control system. Am J Ther. 2017;24:E177-E180.

- Clark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, et al. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:33-37.

- Mahjoubi L, Joyeux A, Delambre JF, et al. Near-death thoracic trauma caused by a stingray in the Indian Ocean. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:262-263.

- Parra MW, Constantini EN, Rodas EB. Surviving a transfixing cardiac injury caused by a stingray barb. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:E115-E116.

- Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, et al. Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7912.

- Auerbach PS, Norris RL. Marine envenomation. In: Longo DL, Kasper SL, Jameson JL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:144-148.

- Cook MD, Matteucci MJ, Lall R, et al. Stingray envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2006;30:345-347.

- Bowers RC, Mustain MV. Disorders due to physical & environmental agents. In: Humphries RL, Stone C, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:835-861.

- Domingos MO, Franzolin MR, dos Anjos MT, et al. The influence of environmental bacteria in freshwater stingray wound-healing. Toxicon. 2011;58:147-153.

- Auerbach PS, Yajko DM, Nassos PS, et al. Bacteriology of the marine environment: implications for clinical therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:643-649.

- Torrez PP, Quiroga MM, Said R, et al. Tetanus after envenomations caused by freshwater stingrays. Toxicon. 2015;97:32-35.

- Hiemenz JW, Kennedy B, Kwon-Chung KJ. Invasive fusariosis associated with an injury by a stingray barb. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:209-213.

- da Silva NJ Jr, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, et al. A severe accident caused by an ocellate river stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in central Brazil: how well do we really understand stingray venom chemistry, envenomation, and therapeutics? Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:2272-2288.

- Tartar D, Limova M, North J. Clinical and histopathologic findings in cutaneous sting ray wounds: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19261.

- Jarvis HC, Matheny LM, Clanton TO. Stingray injury to the webspace of the foot. Orthopedics. 2012;35:E762-E765.

- Trickett R, Whitaker IS, Boyce DE. Sting-ray injuries to the hand: case report, literature review and a suggested algorithm for management. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:E270-E273.

- Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103-112.

- O’Malley GF, O’Malley RN, Pham O, et al. Retained stingray barb and the importance of imaging. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:375-379.

- How to protect yourself from stingrays. Howcast website. https://www.howcast.com/videos/228034-how-to-protect-yourself-from-stingrays/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

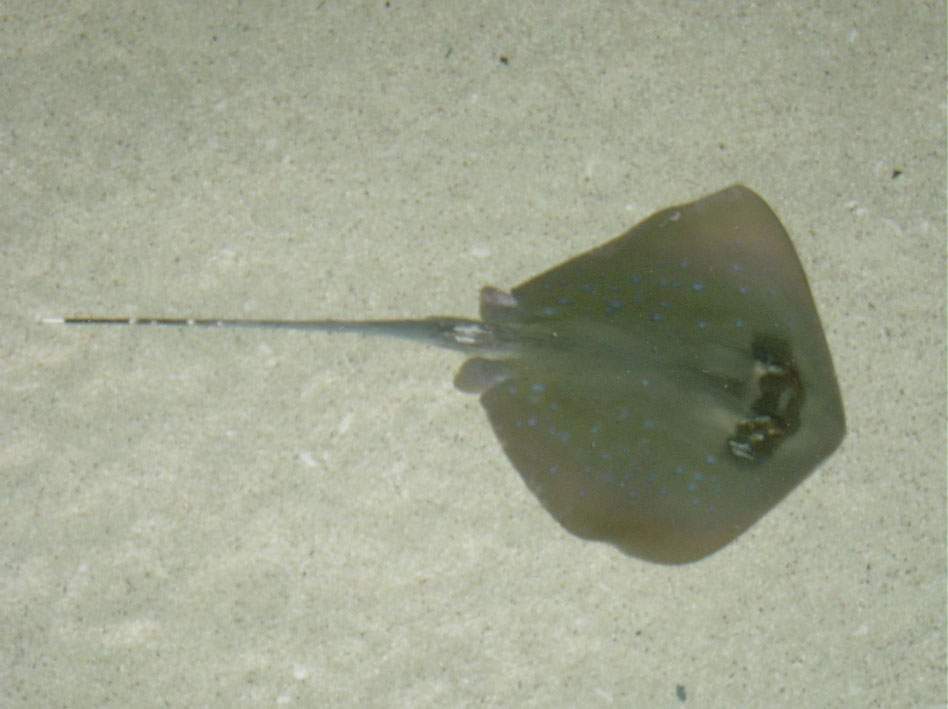

Incidence and Characteristics

Stingrays are dorsoventrally flattened, diamond-shaped fish with light-colored ventral and dark-colored dorsal surfaces. They have strong pectoral wings that allow them to swim forward and backward and even launch off waves.3 Stingrays range in size from the palm of a human hand to 6.5 ft in width. They possess 1 or more spines (2.5 to >30 cm in length) that are disguised by much longer tails.6,7 They often are encountered accidentally because they bury themselves in the sand or mud of shallow coastal waters or rivers with only their eyes and tails exposed to fool prey and avoid predators.

Injury Clinical Presentation

Stingray injuries typically involve the lower legs, ankles, or feet after stepping on a stingray.8 Fishermen can present with injuries of the upper extremities after handling fish with their hands.9 Other rarer injuries occur when individuals are swimming alongside stingrays or when stingrays catapult off waves into moving boats.10,11 Stingrays impale victims by using their tails to direct a retroserrate barb composed of a strong cartilaginous material called vasodentin. The barb releases venom by breaking through the venom-containing integumentary sheath that encapsulates it. Stingray venom contains phosphodiesterase, serotonin, and 5′-nucleotidase. It causes severe pain, vasoconstriction, ischemia, and poor wound healing, along with systemic effects such as disorientation, syncope, seizures, salivation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle cramps or fasciculations, pruritus, allergic reaction, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, paralysis, and possibly death.1,8,12,13

Management

Pain Relief

As with many marine envenomations, immersion in hot but not scalding water can inactivate venom and reduce symptoms.8,9 In one retrospective review, 52 of 75 (69%) patients reporting to a California poison center with stingray injuries had improvement in pain within 1 hour of hot water immersion before any analgesics were instituted.8 In another review, 65 of 74 (88%) patients presenting to a California emergency department within 24 hours of sustaining a stingray injury had complete relief of pain within 30 minutes of hot water immersion. Patients who received analgesics in addition to hot water immersion did not require a second dose.9 In concordance with these studies, we suggest immersing areas affected by stingray injuries in hot water (temperature, 43.3°C to 46.1°C [110°F–115°F]; or as close to this range as tolerated) until pain subsides.8,9,14 Ice packs are an alternative to hot water immersion that may be more readily available to patients. If pain does not resolve following hot water immersion or application of an ice pack, additional analgesics and xylocaine without epinephrine may be helpful.9,15

Infection

One major complication of stingray injuries is infection.8,9 Many bacterial species reside in stingray mucus, the marine environment, or on human skin that may be introduced during a single injury. Marine envenomations can involve organisms such as Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium species, which often are resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis covering common causes of soft-tissue infection such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.8,9,16,17 Additionally, physicians should cover for Clostridium species and ensure patients are up-to-date on vaccinations because severe cases of tetanus following stingray injuries have been reported.18 Lastly, fungal infections including fusariosis have been reported following stingray injuries and should be considered if a patient develops an infection.19

Several authors support the use of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics in all but mild stingray injuries.8,9,20,21 Although no standardized definition exists, mild injuries generally represent patients with superficial lacerations or less, while deeper lacerations and puncture wounds require prophylaxis. Several authors agree on the use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily) for 5 to 7 days following severe stingray injuries.1,9,13,22 Other proposed antibiotic regimens include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) or tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days.13 Failure of ciprofloxacin therapy after 7 days has been reported, with resolution of infection after treatment with an intravenous cephalosporin for 7 days.20 Failure of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy also has been reported, with one case requiring levofloxacin for a much longer course.21 Clinical follow-up remains essential after prescribing prophylactic antibiotics, as resistance is common.

Foreign Bodies

Stingray injuries also are often complicated by foreign bodies or retained spines.3,8 Although these complications are less severe than infection, all wounds should be explored for material under local anesthesia. Furthermore, there has been support for thorough debridement of necrotic tissue with referral to a hand specialist for deeper injuries to the hands as well as referral to a foot and ankle specialist for deeper injuries of the lower extremities.23,24 More serious injuries with penetration of vital structures, such as through the chest or abdomen, require immediate exploration in an operating room.1,24

Imaging

Routine imaging of stingray injuries remains controversial. In a case series of 119 patients presenting to a California emergency department with stingray injuries, Clark et al9 found that radiographs were not helpful. This finding likely is due in part to an inability to detect hypodense material such as integumentary or glandular tissue via radiography.3 However, radiographs have been used to identify retained stingray barbs in select cases in which retained barbs are suspected.2,25 Lastly, ultrasonography potentially may offer a better first choice when a barb is not readily apparent; magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated for more involved areas and for further visualization of suspected hypodense material, though at a higher expense.2,9

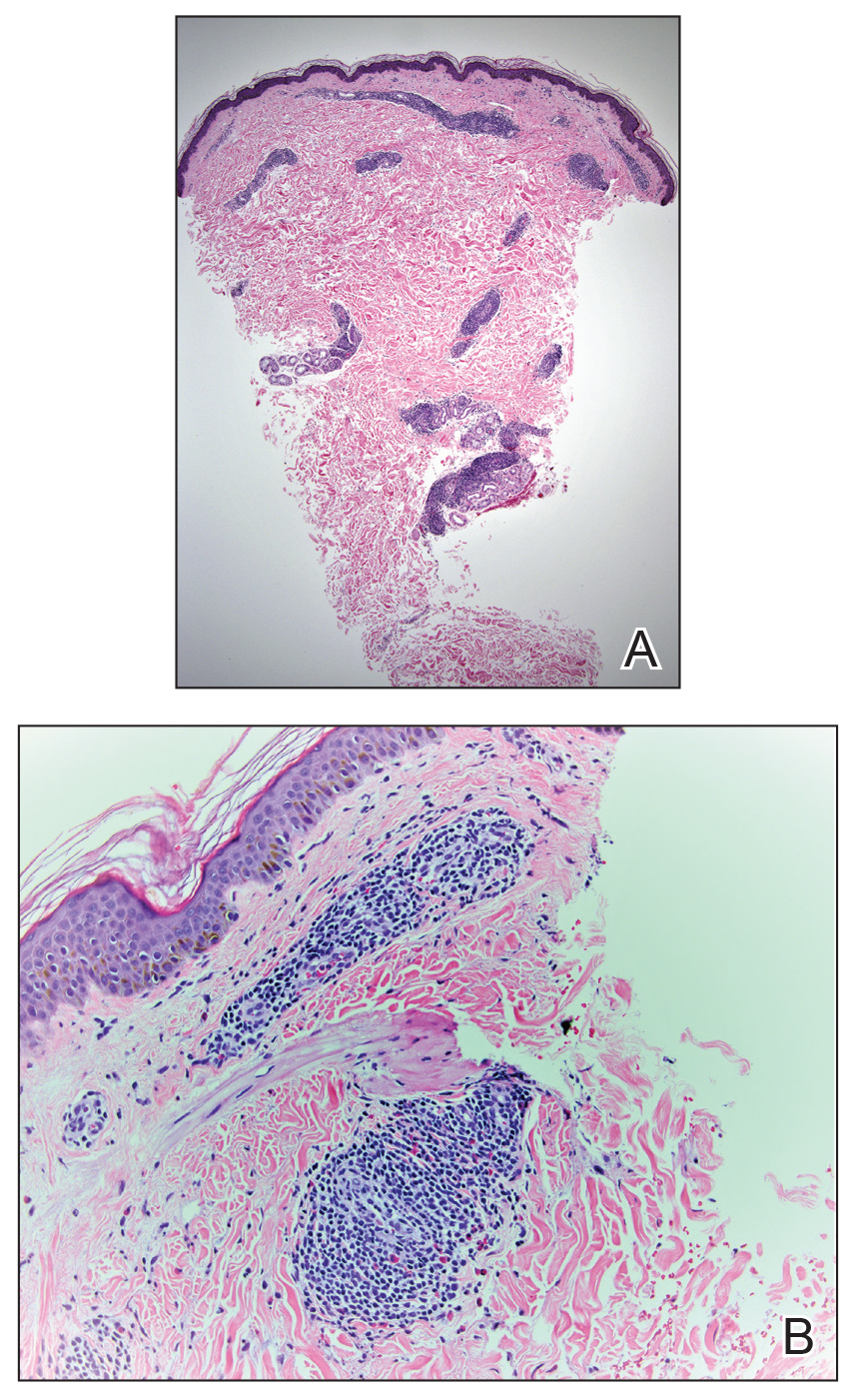

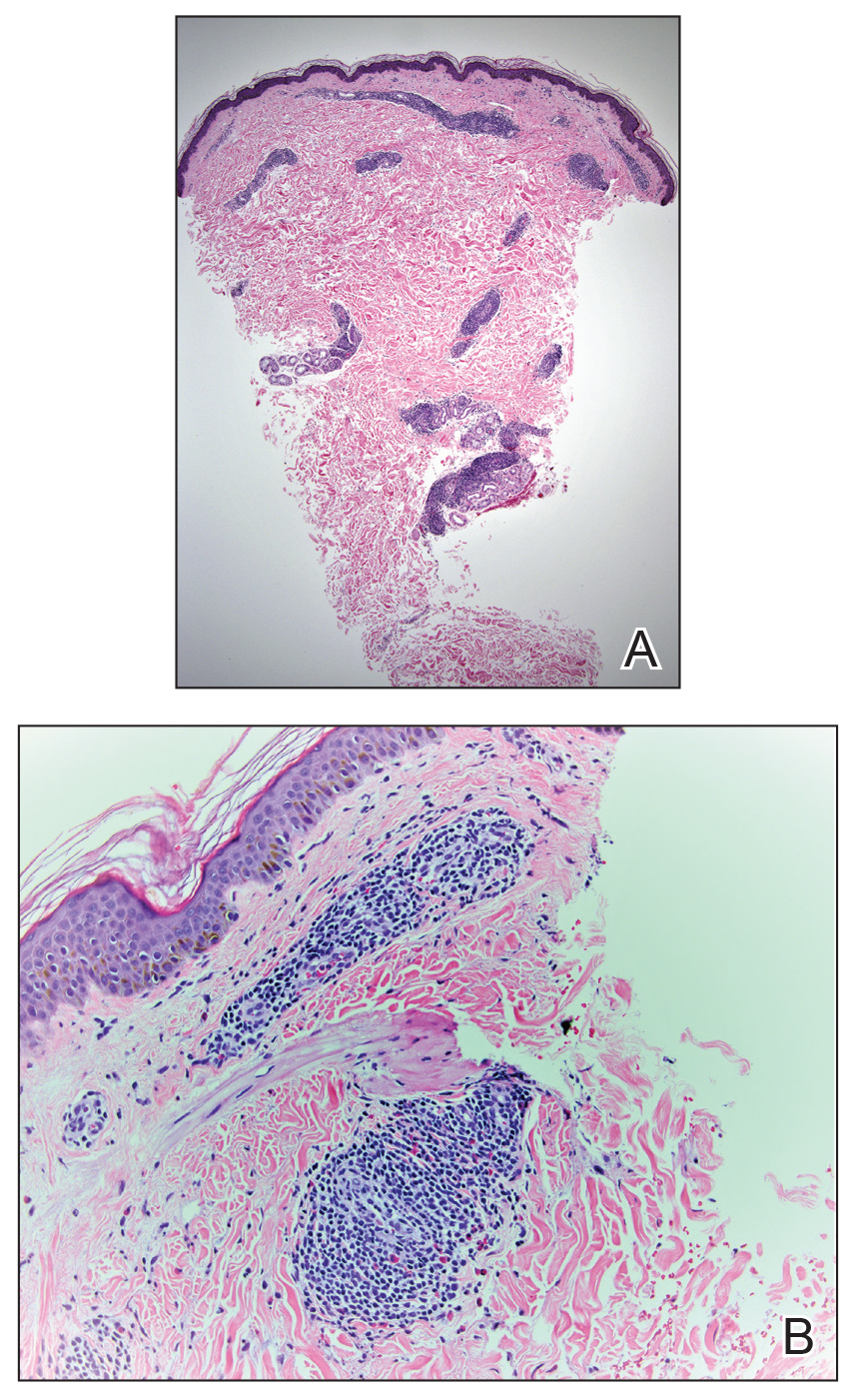

Biopsy

Biopsies of stingray injuries are rarely performed, and the findings are not well characterized. One case biopsied 2 months after injury showed a large zone of paucicellular necrosis with superficial ulceration and granulomatous inflammation. The stingray venom was most likely responsible for the pattern of necrosis noted in the biopsy.21

Avoidance and Prevention

Patients traveling to areas of the world inhabited by stingrays should receive counseling on how to avoid injury. Prior to entry, individuals can throw stones or use a long stick to clear their walking or swimming areas of venomous fish.26 Polarized sunglasses may help spot stingrays in shallow water. Furthermore, wading through water with a shuffling gait can help individuals avoid stepping directly on a stingray and also warns stingrays that someone is in the area. Individuals who spend more time in coastal waters or river systems inhabited by stingrays may invest in protective stingray gear such as leg guards or specialized wading boots.26 Lastly, fishermen should be advised to avoid handling stingrays with their hands and instead cut their fishing line to release the fish.

Incidence and Characteristics

Stingrays are dorsoventrally flattened, diamond-shaped fish with light-colored ventral and dark-colored dorsal surfaces. They have strong pectoral wings that allow them to swim forward and backward and even launch off waves.3 Stingrays range in size from the palm of a human hand to 6.5 ft in width. They possess 1 or more spines (2.5 to >30 cm in length) that are disguised by much longer tails.6,7 They often are encountered accidentally because they bury themselves in the sand or mud of shallow coastal waters or rivers with only their eyes and tails exposed to fool prey and avoid predators.

Injury Clinical Presentation

Stingray injuries typically involve the lower legs, ankles, or feet after stepping on a stingray.8 Fishermen can present with injuries of the upper extremities after handling fish with their hands.9 Other rarer injuries occur when individuals are swimming alongside stingrays or when stingrays catapult off waves into moving boats.10,11 Stingrays impale victims by using their tails to direct a retroserrate barb composed of a strong cartilaginous material called vasodentin. The barb releases venom by breaking through the venom-containing integumentary sheath that encapsulates it. Stingray venom contains phosphodiesterase, serotonin, and 5′-nucleotidase. It causes severe pain, vasoconstriction, ischemia, and poor wound healing, along with systemic effects such as disorientation, syncope, seizures, salivation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle cramps or fasciculations, pruritus, allergic reaction, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, paralysis, and possibly death.1,8,12,13

Management

Pain Relief

As with many marine envenomations, immersion in hot but not scalding water can inactivate venom and reduce symptoms.8,9 In one retrospective review, 52 of 75 (69%) patients reporting to a California poison center with stingray injuries had improvement in pain within 1 hour of hot water immersion before any analgesics were instituted.8 In another review, 65 of 74 (88%) patients presenting to a California emergency department within 24 hours of sustaining a stingray injury had complete relief of pain within 30 minutes of hot water immersion. Patients who received analgesics in addition to hot water immersion did not require a second dose.9 In concordance with these studies, we suggest immersing areas affected by stingray injuries in hot water (temperature, 43.3°C to 46.1°C [110°F–115°F]; or as close to this range as tolerated) until pain subsides.8,9,14 Ice packs are an alternative to hot water immersion that may be more readily available to patients. If pain does not resolve following hot water immersion or application of an ice pack, additional analgesics and xylocaine without epinephrine may be helpful.9,15

Infection

One major complication of stingray injuries is infection.8,9 Many bacterial species reside in stingray mucus, the marine environment, or on human skin that may be introduced during a single injury. Marine envenomations can involve organisms such as Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium species, which often are resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis covering common causes of soft-tissue infection such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.8,9,16,17 Additionally, physicians should cover for Clostridium species and ensure patients are up-to-date on vaccinations because severe cases of tetanus following stingray injuries have been reported.18 Lastly, fungal infections including fusariosis have been reported following stingray injuries and should be considered if a patient develops an infection.19

Several authors support the use of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics in all but mild stingray injuries.8,9,20,21 Although no standardized definition exists, mild injuries generally represent patients with superficial lacerations or less, while deeper lacerations and puncture wounds require prophylaxis. Several authors agree on the use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily) for 5 to 7 days following severe stingray injuries.1,9,13,22 Other proposed antibiotic regimens include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) or tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days.13 Failure of ciprofloxacin therapy after 7 days has been reported, with resolution of infection after treatment with an intravenous cephalosporin for 7 days.20 Failure of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy also has been reported, with one case requiring levofloxacin for a much longer course.21 Clinical follow-up remains essential after prescribing prophylactic antibiotics, as resistance is common.

Foreign Bodies

Stingray injuries also are often complicated by foreign bodies or retained spines.3,8 Although these complications are less severe than infection, all wounds should be explored for material under local anesthesia. Furthermore, there has been support for thorough debridement of necrotic tissue with referral to a hand specialist for deeper injuries to the hands as well as referral to a foot and ankle specialist for deeper injuries of the lower extremities.23,24 More serious injuries with penetration of vital structures, such as through the chest or abdomen, require immediate exploration in an operating room.1,24

Imaging

Routine imaging of stingray injuries remains controversial. In a case series of 119 patients presenting to a California emergency department with stingray injuries, Clark et al9 found that radiographs were not helpful. This finding likely is due in part to an inability to detect hypodense material such as integumentary or glandular tissue via radiography.3 However, radiographs have been used to identify retained stingray barbs in select cases in which retained barbs are suspected.2,25 Lastly, ultrasonography potentially may offer a better first choice when a barb is not readily apparent; magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated for more involved areas and for further visualization of suspected hypodense material, though at a higher expense.2,9

Biopsy

Biopsies of stingray injuries are rarely performed, and the findings are not well characterized. One case biopsied 2 months after injury showed a large zone of paucicellular necrosis with superficial ulceration and granulomatous inflammation. The stingray venom was most likely responsible for the pattern of necrosis noted in the biopsy.21

Avoidance and Prevention

Patients traveling to areas of the world inhabited by stingrays should receive counseling on how to avoid injury. Prior to entry, individuals can throw stones or use a long stick to clear their walking or swimming areas of venomous fish.26 Polarized sunglasses may help spot stingrays in shallow water. Furthermore, wading through water with a shuffling gait can help individuals avoid stepping directly on a stingray and also warns stingrays that someone is in the area. Individuals who spend more time in coastal waters or river systems inhabited by stingrays may invest in protective stingray gear such as leg guards or specialized wading boots.26 Lastly, fishermen should be advised to avoid handling stingrays with their hands and instead cut their fishing line to release the fish.

- Aurbach PS. Envenomations by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerbach PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1730-1749.

- Robins CR, Ray GC. A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1986.

- Diaz JH. The evaluation, management, and prevention of stingray injuries in travelers. J Travel Med. 2008;15:102-109.

- Haddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto JB, et al. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinical and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon. 2004;43:287-294.

- Marinkelle CJ. Accidents by venomous animals in Colombia. Ind Med Surg. 1966;35:988-992.

- Last PR, White WT, Caire JN, et al. Sharks and Rays of Borneo. Collingwood VIC, Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2010.

- Mebs D. Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

- Clark AT, Clark RF, Cantrell FL. A retrospective review of the presentation and treatment of stingray stings reported to a poison control system. Am J Ther. 2017;24:E177-E180.

- Clark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, et al. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:33-37.

- Mahjoubi L, Joyeux A, Delambre JF, et al. Near-death thoracic trauma caused by a stingray in the Indian Ocean. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:262-263.

- Parra MW, Constantini EN, Rodas EB. Surviving a transfixing cardiac injury caused by a stingray barb. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:E115-E116.

- Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, et al. Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7912.

- Auerbach PS, Norris RL. Marine envenomation. In: Longo DL, Kasper SL, Jameson JL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:144-148.

- Cook MD, Matteucci MJ, Lall R, et al. Stingray envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2006;30:345-347.

- Bowers RC, Mustain MV. Disorders due to physical & environmental agents. In: Humphries RL, Stone C, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:835-861.

- Domingos MO, Franzolin MR, dos Anjos MT, et al. The influence of environmental bacteria in freshwater stingray wound-healing. Toxicon. 2011;58:147-153.

- Auerbach PS, Yajko DM, Nassos PS, et al. Bacteriology of the marine environment: implications for clinical therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:643-649.

- Torrez PP, Quiroga MM, Said R, et al. Tetanus after envenomations caused by freshwater stingrays. Toxicon. 2015;97:32-35.

- Hiemenz JW, Kennedy B, Kwon-Chung KJ. Invasive fusariosis associated with an injury by a stingray barb. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:209-213.

- da Silva NJ Jr, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, et al. A severe accident caused by an ocellate river stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in central Brazil: how well do we really understand stingray venom chemistry, envenomation, and therapeutics? Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:2272-2288.

- Tartar D, Limova M, North J. Clinical and histopathologic findings in cutaneous sting ray wounds: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19261.

- Jarvis HC, Matheny LM, Clanton TO. Stingray injury to the webspace of the foot. Orthopedics. 2012;35:E762-E765.

- Trickett R, Whitaker IS, Boyce DE. Sting-ray injuries to the hand: case report, literature review and a suggested algorithm for management. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:E270-E273.

- Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103-112.

- O’Malley GF, O’Malley RN, Pham O, et al. Retained stingray barb and the importance of imaging. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:375-379.

- How to protect yourself from stingrays. Howcast website. https://www.howcast.com/videos/228034-how-to-protect-yourself-from-stingrays/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

- Aurbach PS. Envenomations by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerbach PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1730-1749.

- Robins CR, Ray GC. A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1986.

- Diaz JH. The evaluation, management, and prevention of stingray injuries in travelers. J Travel Med. 2008;15:102-109.

- Haddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto JB, et al. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinical and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon. 2004;43:287-294.

- Marinkelle CJ. Accidents by venomous animals in Colombia. Ind Med Surg. 1966;35:988-992.

- Last PR, White WT, Caire JN, et al. Sharks and Rays of Borneo. Collingwood VIC, Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2010.

- Mebs D. Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

- Clark AT, Clark RF, Cantrell FL. A retrospective review of the presentation and treatment of stingray stings reported to a poison control system. Am J Ther. 2017;24:E177-E180.

- Clark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, et al. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:33-37.

- Mahjoubi L, Joyeux A, Delambre JF, et al. Near-death thoracic trauma caused by a stingray in the Indian Ocean. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:262-263.

- Parra MW, Constantini EN, Rodas EB. Surviving a transfixing cardiac injury caused by a stingray barb. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:E115-E116.

- Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, et al. Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7912.

- Auerbach PS, Norris RL. Marine envenomation. In: Longo DL, Kasper SL, Jameson JL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:144-148.

- Cook MD, Matteucci MJ, Lall R, et al. Stingray envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2006;30:345-347.

- Bowers RC, Mustain MV. Disorders due to physical & environmental agents. In: Humphries RL, Stone C, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:835-861.

- Domingos MO, Franzolin MR, dos Anjos MT, et al. The influence of environmental bacteria in freshwater stingray wound-healing. Toxicon. 2011;58:147-153.

- Auerbach PS, Yajko DM, Nassos PS, et al. Bacteriology of the marine environment: implications for clinical therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:643-649.

- Torrez PP, Quiroga MM, Said R, et al. Tetanus after envenomations caused by freshwater stingrays. Toxicon. 2015;97:32-35.

- Hiemenz JW, Kennedy B, Kwon-Chung KJ. Invasive fusariosis associated with an injury by a stingray barb. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:209-213.

- da Silva NJ Jr, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, et al. A severe accident caused by an ocellate river stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in central Brazil: how well do we really understand stingray venom chemistry, envenomation, and therapeutics? Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:2272-2288.

- Tartar D, Limova M, North J. Clinical and histopathologic findings in cutaneous sting ray wounds: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19261.

- Jarvis HC, Matheny LM, Clanton TO. Stingray injury to the webspace of the foot. Orthopedics. 2012;35:E762-E765.

- Trickett R, Whitaker IS, Boyce DE. Sting-ray injuries to the hand: case report, literature review and a suggested algorithm for management. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:E270-E273.

- Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103-112.

- O’Malley GF, O’Malley RN, Pham O, et al. Retained stingray barb and the importance of imaging. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:375-379.

- How to protect yourself from stingrays. Howcast website. https://www.howcast.com/videos/228034-how-to-protect-yourself-from-stingrays/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

Practice Points

- Acute pain associated with stingray injuries can be treated with hot water immersion.

- Stingray injuries are prone to secondary infection and poor wound healing.

What’s Eating You? Bedbugs

Bedbugs are common pests causing several health and economic consequences. With increased travel, pesticide resistance, and a lack of awareness about prevention, bedbugs have become even more difficult to control, especially within large population centers.1 The US Environmental Protection Agency considers bedbugs to be a considerable public health issue.2 Typically, they are found in private residences; however, there have been more reports of bedbugs discovered in the workplace within the last 20 years.3-5 Herein, we present a case of bedbugs presenting in this unusual environment.

Case Report

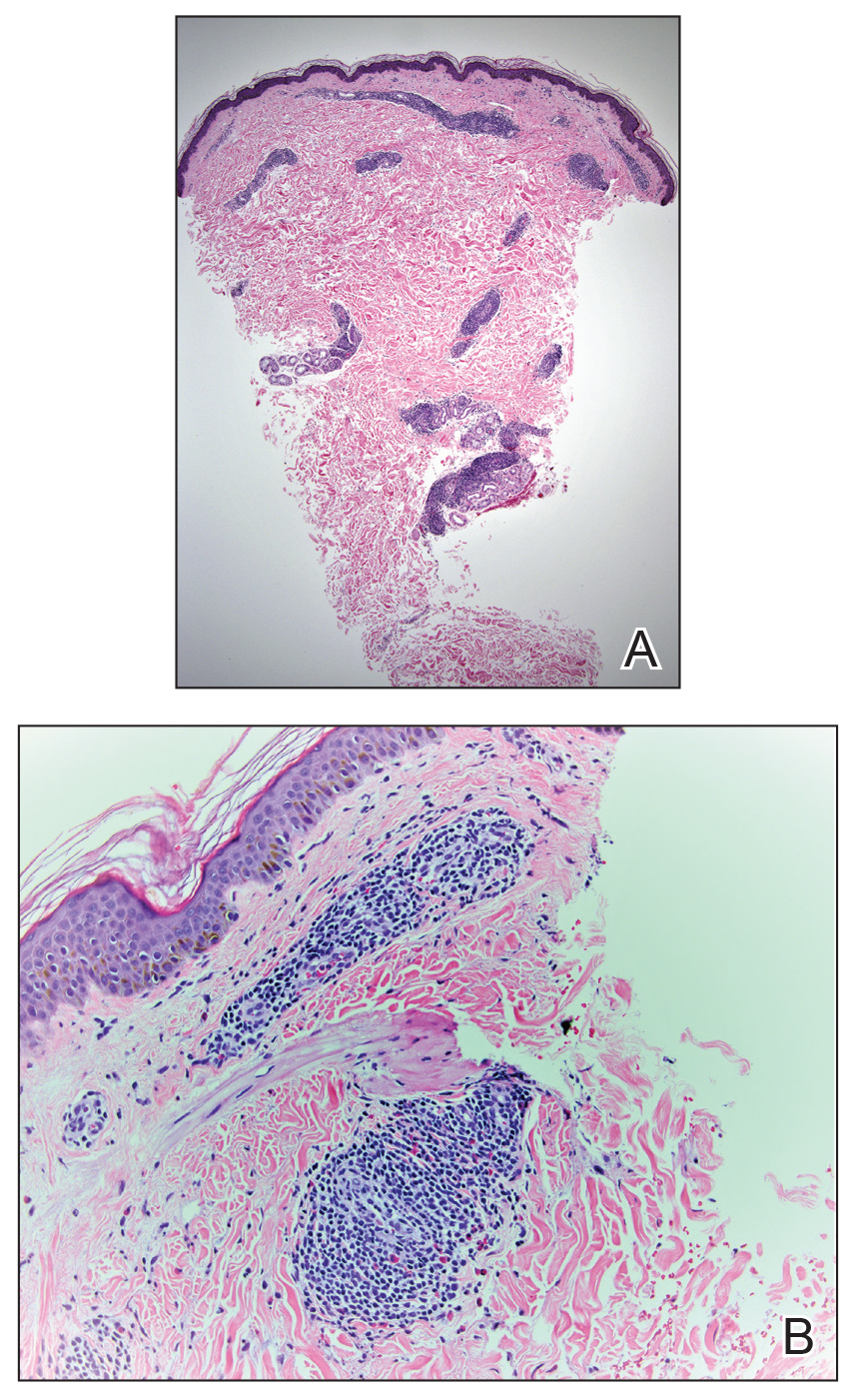

A 42-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with intensely itchy bumps over the bilateral posterior arms of 3 months’ duration. He had no other skin, hair, or nail concerns. Over the last 3 months prior to dermatologic evaluation, he was treated by an outside physician with topical steroids, systemic antibiotics, topical antifungals, and even systemic steroids with no improvement of the lesions or symptoms. On clinical examination at the current presentation, 8 to 10 pink dermal papules coalescing into 10-cm round patches were noted on the bilateral posterior arms (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the posterior right arm was performed, and histologic analysis showed a dense superficial and deep infiltrate and a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 2). No notable epidermal changes were observed.

At this time, the patient was counseled that the most likely cause was some unknown arthropod exposure. Given the chronicity of the patient’s disease course, bedbugs were favored; however, an extensive search of the patient’s home failed to uncover any arthropods, let alone bedbugs. A few weeks later, the patient discovered insects emanating from the mesh backing of his office chair while at work (Figure 3). The location of the intruders corresponded exactly with the lesions on the posterior arms. The occupational health office at his workplace collected samples of the arthropods and confirmed they were bedbugs. The patient’s lesions resolved with topical clobetasol once eradication of the workplace was complete.

Discussion

Morphology and Epidemiology

Bedbugs are wingless arthropods that have flat, oval-shaped, reddish brown bodies. They are approximately 4.5-mm long and 2.5-mm wide (Figure 4). The 2 most common species of bedbugs that infect humans are Cimex lectularius and Cimex hemipterus. Bedbugs are most commonly found in hotels, apartments, and residential households near sleep locations. They reside in crevices, cracks, mattresses, cushions, dressers, and other structures proximal to the bed. During the day they remain hidden, but at night they emerge for a blood meal. The average lifespan of a bedbug is 6 to 12 months.6 Females lay more than 200 eggs that hatch in approximately 6 to 10 days.7 Bedbugs progress through 5 nymph stages before becoming adults; several blood meals are required to advance each stage.6

Although commonly attributed to the home, bedbugs are being increasingly seen in the office setting.3-5 In a survey given to pest management professionals in 2015, more than 45% reported that they were contracted by corporations for bedbug infestations in office settings, an increase from 18% in 2010 and 36% in 2013.3 Bedbugs are brought into offices through clothing, luggage, books, and other personal items. Unable to find hosts at night, bedbugs adapt to daytime hours and spread to more unpredictable locations, including chairs, office equipment, desks, and computers.4 Additionally, they frequently move around to find a suitable host.5 As a result, the growth rate of bedbugs in an office setting is much slower than in the home, with fewer insects. Our patient did not have bedbugs at home, but it is possible that other employees transported them to the office over time.

Clinical Manifestations

Bedbugs cause pruritic and nonpruritic skin rashes, often of the arms, legs, neck, and face. A common reaction is an erythematous papule with a hemorrhagic punctum caused by one bite.8 Other presentations include purpuric macules, bullae, and papular urticaria.8-10 Although bedbugs are suspected to transmit infectious diseases, no reports have substantiated that claim.11

Our patient had several coalescing dermal papules on the arms indicating multiple bites around the same area. Due to the stationary aspect of his job—with the arms resting on his chair while typing at his desk—our patient was an easy target for consistent blood meals.

Detection

Due to an overall smaller population of insects in an office setting, detection of bedbugs in the workplace can be difficult. Infestations can be primarily identified on visual inspection by pest control.12 The mesh backing on our patient’s chair was one site where bedbugs resided. It is important to check areas where employees congregate, such as lounges, lunch areas, conference rooms, and printers.4 It also is essential to examine coatracks and locker rooms, as employees may leave personal items that can serve as a source of transmission of the bugs from home. Additional detection tools provided by pest management professionals include canines, as well as devices that emit pheromones, carbon dioxide, or heat to ensnare the insects.12

Treatment

Treatment of bedbug bites is quite variable. For some patients, lesions may resolve on their own. Pruritic maculopapular eruptions can be treated with topical pramoxine or doxepin.8 Patients who develop allergic urticaria can use oral antihistamines. Systemic reactions such as anaphylaxis can be treated with a combination of intramuscular epinephrine, antihistamines, and corticosteroids.8 The etiology of our patient’s condition initially was unknown, and thus he was given unnecessary systemic steroids and antifungals until the source of the rash was identified and eradicated. Topical clobetasol was subsequently administered and was sufficient to resolve his symptoms.

Final Thoughts

Bedbugs continue to remain a nuisance in the home. This case provides an example of bedbugs in the office, a location that is not commonly associated with bedbug infestations. Bedbugs pose numerous psychological, economic, and health consequences.2 Productivity can be reduced, as patients with symptomatic lesions will be unable to work effectively, and those who are unaffected may be unwilling to work knowing their office environment poses a health risk. In addition, employees may worry about bringing the bedbugs home. It is important that employees be educated on the signs of a bedbug infestation and take preventive measures to stop spreading or introducing them to the office space. Due to the scattered habitation of bedbugs in offices, pest control managers need to be vigilant to identify sources of infestation and eradicate accordingly. Clinical manifestations can be nonspecific, resembling autoimmune disorders, fungal infections, or bites from other various arthropods; thus, treatment is highly dependent on the patient’s history and occupational exposure.

Bedbugs have successfully adapted to a new environment in the office space. Dermatologists and other health care professionals can no longer exclusively associate bedbugs with the home. When the clinical and histological presentation suggests an arthropod assault, we must counsel our patients to surveil their homes and work settings alike. If necessary, they should seek the assistance of occupational health professionals.

1. Ralph N, Jones HE, Thorpe LE. Self-reported bed bug infestation among New York City residents: prevalence and risk factors. J Environ Health; 2013;76:38-45.

2. US Environmental Protection Agency. Bed Bugs are public health pests. EPA website. https://www.epa.gov/bedbugs/bed-bugs-are-public-health-pests. Accessed December 6, 2018.

3. Potter MF, Haynes KF, Fredericks J. Bed bugs across America: 2015 Bugs Without Borders survey. Pestworld. 2015:4-14. https://www.npmapestworld.org/default/assets/File/newsroom/magazine/2015/nov-dec_2015.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

4. Pinto LJ, Cooper R, Kraft SK. Bed bugs in office buildings: the ultimate challenge? MGK website. http://giecdn.blob.core.windows.net/fileuploads/file/bedbugs-office-buildings.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

5. Baumblatt JA, Dunn JR, Schaffner W, et al. An outbreak of bed bug infestation in an office building. J Environ Health. 2014;76:16-19.

6. Parasites: bed bugs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. www.cdc.gov/parasites/bedbugs/biology.html. Updated March 17, 2015. Accessed September 21, 2018.

7. Bed bugs. University of Minnesota Extension website. https://www.extension.umn.edu/garden/insects/find/bed-bugs-in-residences. Accessed September 21, 2018.

8. Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularius) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358-1366.

9. Scarupa, MD, Economides A. Bedbug bites masquerading as urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1508-1509.

10. Abdel-Naser MB, Lotfy RA, Al-Sherbiny MM, et al. Patients with papular urticaria have IgG antibodies to bedbug (Cimex lectularius) antigens. Parasitol Res. 2006;98:550-556.

11. Lai O, Ho D, Glick S, et al. Bed bugs and possible transmission of human pathogens: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:531-538.

12. Vaidyanathan R, Feldlaufer MF. Bed bug detection: current technologies and future directions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:619-625.

Bedbugs are common pests causing several health and economic consequences. With increased travel, pesticide resistance, and a lack of awareness about prevention, bedbugs have become even more difficult to control, especially within large population centers.1 The US Environmental Protection Agency considers bedbugs to be a considerable public health issue.2 Typically, they are found in private residences; however, there have been more reports of bedbugs discovered in the workplace within the last 20 years.3-5 Herein, we present a case of bedbugs presenting in this unusual environment.

Case Report

A 42-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with intensely itchy bumps over the bilateral posterior arms of 3 months’ duration. He had no other skin, hair, or nail concerns. Over the last 3 months prior to dermatologic evaluation, he was treated by an outside physician with topical steroids, systemic antibiotics, topical antifungals, and even systemic steroids with no improvement of the lesions or symptoms. On clinical examination at the current presentation, 8 to 10 pink dermal papules coalescing into 10-cm round patches were noted on the bilateral posterior arms (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the posterior right arm was performed, and histologic analysis showed a dense superficial and deep infiltrate and a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 2). No notable epidermal changes were observed.

At this time, the patient was counseled that the most likely cause was some unknown arthropod exposure. Given the chronicity of the patient’s disease course, bedbugs were favored; however, an extensive search of the patient’s home failed to uncover any arthropods, let alone bedbugs. A few weeks later, the patient discovered insects emanating from the mesh backing of his office chair while at work (Figure 3). The location of the intruders corresponded exactly with the lesions on the posterior arms. The occupational health office at his workplace collected samples of the arthropods and confirmed they were bedbugs. The patient’s lesions resolved with topical clobetasol once eradication of the workplace was complete.

Discussion

Morphology and Epidemiology

Bedbugs are wingless arthropods that have flat, oval-shaped, reddish brown bodies. They are approximately 4.5-mm long and 2.5-mm wide (Figure 4). The 2 most common species of bedbugs that infect humans are Cimex lectularius and Cimex hemipterus. Bedbugs are most commonly found in hotels, apartments, and residential households near sleep locations. They reside in crevices, cracks, mattresses, cushions, dressers, and other structures proximal to the bed. During the day they remain hidden, but at night they emerge for a blood meal. The average lifespan of a bedbug is 6 to 12 months.6 Females lay more than 200 eggs that hatch in approximately 6 to 10 days.7 Bedbugs progress through 5 nymph stages before becoming adults; several blood meals are required to advance each stage.6

Although commonly attributed to the home, bedbugs are being increasingly seen in the office setting.3-5 In a survey given to pest management professionals in 2015, more than 45% reported that they were contracted by corporations for bedbug infestations in office settings, an increase from 18% in 2010 and 36% in 2013.3 Bedbugs are brought into offices through clothing, luggage, books, and other personal items. Unable to find hosts at night, bedbugs adapt to daytime hours and spread to more unpredictable locations, including chairs, office equipment, desks, and computers.4 Additionally, they frequently move around to find a suitable host.5 As a result, the growth rate of bedbugs in an office setting is much slower than in the home, with fewer insects. Our patient did not have bedbugs at home, but it is possible that other employees transported them to the office over time.

Clinical Manifestations

Bedbugs cause pruritic and nonpruritic skin rashes, often of the arms, legs, neck, and face. A common reaction is an erythematous papule with a hemorrhagic punctum caused by one bite.8 Other presentations include purpuric macules, bullae, and papular urticaria.8-10 Although bedbugs are suspected to transmit infectious diseases, no reports have substantiated that claim.11

Our patient had several coalescing dermal papules on the arms indicating multiple bites around the same area. Due to the stationary aspect of his job—with the arms resting on his chair while typing at his desk—our patient was an easy target for consistent blood meals.

Detection

Due to an overall smaller population of insects in an office setting, detection of bedbugs in the workplace can be difficult. Infestations can be primarily identified on visual inspection by pest control.12 The mesh backing on our patient’s chair was one site where bedbugs resided. It is important to check areas where employees congregate, such as lounges, lunch areas, conference rooms, and printers.4 It also is essential to examine coatracks and locker rooms, as employees may leave personal items that can serve as a source of transmission of the bugs from home. Additional detection tools provided by pest management professionals include canines, as well as devices that emit pheromones, carbon dioxide, or heat to ensnare the insects.12

Treatment

Treatment of bedbug bites is quite variable. For some patients, lesions may resolve on their own. Pruritic maculopapular eruptions can be treated with topical pramoxine or doxepin.8 Patients who develop allergic urticaria can use oral antihistamines. Systemic reactions such as anaphylaxis can be treated with a combination of intramuscular epinephrine, antihistamines, and corticosteroids.8 The etiology of our patient’s condition initially was unknown, and thus he was given unnecessary systemic steroids and antifungals until the source of the rash was identified and eradicated. Topical clobetasol was subsequently administered and was sufficient to resolve his symptoms.

Final Thoughts

Bedbugs continue to remain a nuisance in the home. This case provides an example of bedbugs in the office, a location that is not commonly associated with bedbug infestations. Bedbugs pose numerous psychological, economic, and health consequences.2 Productivity can be reduced, as patients with symptomatic lesions will be unable to work effectively, and those who are unaffected may be unwilling to work knowing their office environment poses a health risk. In addition, employees may worry about bringing the bedbugs home. It is important that employees be educated on the signs of a bedbug infestation and take preventive measures to stop spreading or introducing them to the office space. Due to the scattered habitation of bedbugs in offices, pest control managers need to be vigilant to identify sources of infestation and eradicate accordingly. Clinical manifestations can be nonspecific, resembling autoimmune disorders, fungal infections, or bites from other various arthropods; thus, treatment is highly dependent on the patient’s history and occupational exposure.

Bedbugs have successfully adapted to a new environment in the office space. Dermatologists and other health care professionals can no longer exclusively associate bedbugs with the home. When the clinical and histological presentation suggests an arthropod assault, we must counsel our patients to surveil their homes and work settings alike. If necessary, they should seek the assistance of occupational health professionals.

Bedbugs are common pests causing several health and economic consequences. With increased travel, pesticide resistance, and a lack of awareness about prevention, bedbugs have become even more difficult to control, especially within large population centers.1 The US Environmental Protection Agency considers bedbugs to be a considerable public health issue.2 Typically, they are found in private residences; however, there have been more reports of bedbugs discovered in the workplace within the last 20 years.3-5 Herein, we present a case of bedbugs presenting in this unusual environment.

Case Report

A 42-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with intensely itchy bumps over the bilateral posterior arms of 3 months’ duration. He had no other skin, hair, or nail concerns. Over the last 3 months prior to dermatologic evaluation, he was treated by an outside physician with topical steroids, systemic antibiotics, topical antifungals, and even systemic steroids with no improvement of the lesions or symptoms. On clinical examination at the current presentation, 8 to 10 pink dermal papules coalescing into 10-cm round patches were noted on the bilateral posterior arms (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the posterior right arm was performed, and histologic analysis showed a dense superficial and deep infiltrate and a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 2). No notable epidermal changes were observed.

At this time, the patient was counseled that the most likely cause was some unknown arthropod exposure. Given the chronicity of the patient’s disease course, bedbugs were favored; however, an extensive search of the patient’s home failed to uncover any arthropods, let alone bedbugs. A few weeks later, the patient discovered insects emanating from the mesh backing of his office chair while at work (Figure 3). The location of the intruders corresponded exactly with the lesions on the posterior arms. The occupational health office at his workplace collected samples of the arthropods and confirmed they were bedbugs. The patient’s lesions resolved with topical clobetasol once eradication of the workplace was complete.

Discussion

Morphology and Epidemiology

Bedbugs are wingless arthropods that have flat, oval-shaped, reddish brown bodies. They are approximately 4.5-mm long and 2.5-mm wide (Figure 4). The 2 most common species of bedbugs that infect humans are Cimex lectularius and Cimex hemipterus. Bedbugs are most commonly found in hotels, apartments, and residential households near sleep locations. They reside in crevices, cracks, mattresses, cushions, dressers, and other structures proximal to the bed. During the day they remain hidden, but at night they emerge for a blood meal. The average lifespan of a bedbug is 6 to 12 months.6 Females lay more than 200 eggs that hatch in approximately 6 to 10 days.7 Bedbugs progress through 5 nymph stages before becoming adults; several blood meals are required to advance each stage.6

Although commonly attributed to the home, bedbugs are being increasingly seen in the office setting.3-5 In a survey given to pest management professionals in 2015, more than 45% reported that they were contracted by corporations for bedbug infestations in office settings, an increase from 18% in 2010 and 36% in 2013.3 Bedbugs are brought into offices through clothing, luggage, books, and other personal items. Unable to find hosts at night, bedbugs adapt to daytime hours and spread to more unpredictable locations, including chairs, office equipment, desks, and computers.4 Additionally, they frequently move around to find a suitable host.5 As a result, the growth rate of bedbugs in an office setting is much slower than in the home, with fewer insects. Our patient did not have bedbugs at home, but it is possible that other employees transported them to the office over time.

Clinical Manifestations

Bedbugs cause pruritic and nonpruritic skin rashes, often of the arms, legs, neck, and face. A common reaction is an erythematous papule with a hemorrhagic punctum caused by one bite.8 Other presentations include purpuric macules, bullae, and papular urticaria.8-10 Although bedbugs are suspected to transmit infectious diseases, no reports have substantiated that claim.11

Our patient had several coalescing dermal papules on the arms indicating multiple bites around the same area. Due to the stationary aspect of his job—with the arms resting on his chair while typing at his desk—our patient was an easy target for consistent blood meals.

Detection

Due to an overall smaller population of insects in an office setting, detection of bedbugs in the workplace can be difficult. Infestations can be primarily identified on visual inspection by pest control.12 The mesh backing on our patient’s chair was one site where bedbugs resided. It is important to check areas where employees congregate, such as lounges, lunch areas, conference rooms, and printers.4 It also is essential to examine coatracks and locker rooms, as employees may leave personal items that can serve as a source of transmission of the bugs from home. Additional detection tools provided by pest management professionals include canines, as well as devices that emit pheromones, carbon dioxide, or heat to ensnare the insects.12

Treatment

Treatment of bedbug bites is quite variable. For some patients, lesions may resolve on their own. Pruritic maculopapular eruptions can be treated with topical pramoxine or doxepin.8 Patients who develop allergic urticaria can use oral antihistamines. Systemic reactions such as anaphylaxis can be treated with a combination of intramuscular epinephrine, antihistamines, and corticosteroids.8 The etiology of our patient’s condition initially was unknown, and thus he was given unnecessary systemic steroids and antifungals until the source of the rash was identified and eradicated. Topical clobetasol was subsequently administered and was sufficient to resolve his symptoms.

Final Thoughts

Bedbugs continue to remain a nuisance in the home. This case provides an example of bedbugs in the office, a location that is not commonly associated with bedbug infestations. Bedbugs pose numerous psychological, economic, and health consequences.2 Productivity can be reduced, as patients with symptomatic lesions will be unable to work effectively, and those who are unaffected may be unwilling to work knowing their office environment poses a health risk. In addition, employees may worry about bringing the bedbugs home. It is important that employees be educated on the signs of a bedbug infestation and take preventive measures to stop spreading or introducing them to the office space. Due to the scattered habitation of bedbugs in offices, pest control managers need to be vigilant to identify sources of infestation and eradicate accordingly. Clinical manifestations can be nonspecific, resembling autoimmune disorders, fungal infections, or bites from other various arthropods; thus, treatment is highly dependent on the patient’s history and occupational exposure.

Bedbugs have successfully adapted to a new environment in the office space. Dermatologists and other health care professionals can no longer exclusively associate bedbugs with the home. When the clinical and histological presentation suggests an arthropod assault, we must counsel our patients to surveil their homes and work settings alike. If necessary, they should seek the assistance of occupational health professionals.

1. Ralph N, Jones HE, Thorpe LE. Self-reported bed bug infestation among New York City residents: prevalence and risk factors. J Environ Health; 2013;76:38-45.

2. US Environmental Protection Agency. Bed Bugs are public health pests. EPA website. https://www.epa.gov/bedbugs/bed-bugs-are-public-health-pests. Accessed December 6, 2018.

3. Potter MF, Haynes KF, Fredericks J. Bed bugs across America: 2015 Bugs Without Borders survey. Pestworld. 2015:4-14. https://www.npmapestworld.org/default/assets/File/newsroom/magazine/2015/nov-dec_2015.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

4. Pinto LJ, Cooper R, Kraft SK. Bed bugs in office buildings: the ultimate challenge? MGK website. http://giecdn.blob.core.windows.net/fileuploads/file/bedbugs-office-buildings.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

5. Baumblatt JA, Dunn JR, Schaffner W, et al. An outbreak of bed bug infestation in an office building. J Environ Health. 2014;76:16-19.

6. Parasites: bed bugs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. www.cdc.gov/parasites/bedbugs/biology.html. Updated March 17, 2015. Accessed September 21, 2018.

7. Bed bugs. University of Minnesota Extension website. https://www.extension.umn.edu/garden/insects/find/bed-bugs-in-residences. Accessed September 21, 2018.

8. Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularius) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358-1366.

9. Scarupa, MD, Economides A. Bedbug bites masquerading as urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1508-1509.

10. Abdel-Naser MB, Lotfy RA, Al-Sherbiny MM, et al. Patients with papular urticaria have IgG antibodies to bedbug (Cimex lectularius) antigens. Parasitol Res. 2006;98:550-556.

11. Lai O, Ho D, Glick S, et al. Bed bugs and possible transmission of human pathogens: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:531-538.

12. Vaidyanathan R, Feldlaufer MF. Bed bug detection: current technologies and future directions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:619-625.

1. Ralph N, Jones HE, Thorpe LE. Self-reported bed bug infestation among New York City residents: prevalence and risk factors. J Environ Health; 2013;76:38-45.

2. US Environmental Protection Agency. Bed Bugs are public health pests. EPA website. https://www.epa.gov/bedbugs/bed-bugs-are-public-health-pests. Accessed December 6, 2018.

3. Potter MF, Haynes KF, Fredericks J. Bed bugs across America: 2015 Bugs Without Borders survey. Pestworld. 2015:4-14. https://www.npmapestworld.org/default/assets/File/newsroom/magazine/2015/nov-dec_2015.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

4. Pinto LJ, Cooper R, Kraft SK. Bed bugs in office buildings: the ultimate challenge? MGK website. http://giecdn.blob.core.windows.net/fileuploads/file/bedbugs-office-buildings.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

5. Baumblatt JA, Dunn JR, Schaffner W, et al. An outbreak of bed bug infestation in an office building. J Environ Health. 2014;76:16-19.

6. Parasites: bed bugs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. www.cdc.gov/parasites/bedbugs/biology.html. Updated March 17, 2015. Accessed September 21, 2018.

7. Bed bugs. University of Minnesota Extension website. https://www.extension.umn.edu/garden/insects/find/bed-bugs-in-residences. Accessed September 21, 2018.

8. Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularius) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358-1366.

9. Scarupa, MD, Economides A. Bedbug bites masquerading as urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1508-1509.

10. Abdel-Naser MB, Lotfy RA, Al-Sherbiny MM, et al. Patients with papular urticaria have IgG antibodies to bedbug (Cimex lectularius) antigens. Parasitol Res. 2006;98:550-556.

11. Lai O, Ho D, Glick S, et al. Bed bugs and possible transmission of human pathogens: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:531-538.

12. Vaidyanathan R, Feldlaufer MF. Bed bug detection: current technologies and future directions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:619-625.

Practice Points

- Bedbug exposures in the workplace are on the rise.

- High clinical suspicion is required when atypical dermatoses are not responding to therapy and histology suggests arthropod exposure.

- Once detected, partnership with occupational health and pest management experts is critical to eradicate bedbugs.

Aquatic Antagonists: Lionfish (Pterois volitans)

The lionfish (Pterois volitans) is a member of the Scorpaenidae family of venomous fish.1-3 Lionfish are an invasive species originally from the Indian and Pacific oceans and the Red Sea that now are widely found throughout tropical and temperate oceans in both hemispheres. They are a popular aquarium fish and were inadvertently introduced in the Atlantic Ocean in South Florida during the late 1980s to early 1990s.2,4 Since then, lionfish have spread into reef systems throughout the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico in rapidly growing numbers, and they are now fo und all along the southeastern coast of the United States.5

Characteristics

Lionfish are brightly colored with red or maroon and white stripes, tentacles above the eyes and mouth, fan-shaped pectoral fins, and spines that deliver an especially painful venomous sting that often results in edema (Figure 1). They have 12 dorsal spines, 2 pelvic spines, and 3 anal spines.

Symptoms of Envenomation

As lionfish continue to spread to popular areas of the southeast Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, the chances of human contact with lionfish have increased. Lionfish stings are now the second most common marine envenomation injury after those caused by stingrays.4 Lionfish stings usually occur on the hands, fingers, or forearms during handling of the fish in ocean waters or in maintenance of aquariums. The mechanism of the venom apparatus is similar for all venomous fish. The spines have surrounding integumentary sheaths containing venom that rupture and inject venom when they penetrate the skin.6 The venom is a heat-labile neuromuscular toxin that causes edema (Figure 2), plasma extravasation, and thrombotic skin lesions.7

Wounds are classified into 3 categories: grade I consists of local erythema/ecchymosis, grade II involves vesicle or blister formation, and grade III denotes wounds that develop local necrosis.8 The sting causes immediate and severe throbbing pain, often described as excruciating or rated 10/10 on a basic pain scale, typically radiating up the affected limb. Puncture sites may bleed and often have associated redness and swelling. Pain may last up to 24 hours. Occasionally, foreign material may be left in the wound requiring removal. There also is a chance of secondary infection at the wound site, and severe envenomation can lead to local tissue necrosis.8 Systemic effects can occur in some cases, including nausea, vomiting, sweating, headache, dizziness, disorientation, palpitations, and even syncope.9 However, to our knowledge there are no documented cases of human death from a lionfish sting. Anaphylactic reactions are possible and require immediate treatment.6

A study conducted in the French West Indies evaluated 117 patients with lionfish envenomation and found that victims experienced severe pain and local edema (100%), paresthesia (90%), abdominal cramps (62%), extensive edema (53%), tachycardia (34%), skin rash (32%), gastrointestinal tract symptoms (28%), syncope (27%), transient weakness (24%), hypertension (21%), hypotension (18%), and hyperthermia (9%).9 Complications included local infection (18%) such as skin abscess (5%), skin necrosis (3%), and septic arthritis (2%). Twenty-two percent of patients were hospitalized and 8% required surgery. Local infectious complications were more frequent in those with multiple stings (19%). The study concluded that lionfish now represent a major health threat in the West Indies.9 As lionfish numbers have grown, health care providers are seeing increasing numbers of envenomation cases in areas of the coastal southeastern United States and Caribbean associated with considerable morbidity. Providers in nonendemic areas also may see envenomation injuries due to the lionfish popularity in home aquariums.9

Management