User login

Painful Ulcers on the Elbows, Knees, and Ankles

Painful Ulcers on the Elbows, Knees, and Ankles

THE DIAGNOSIS: Diffuse Dermal Angiomatosis

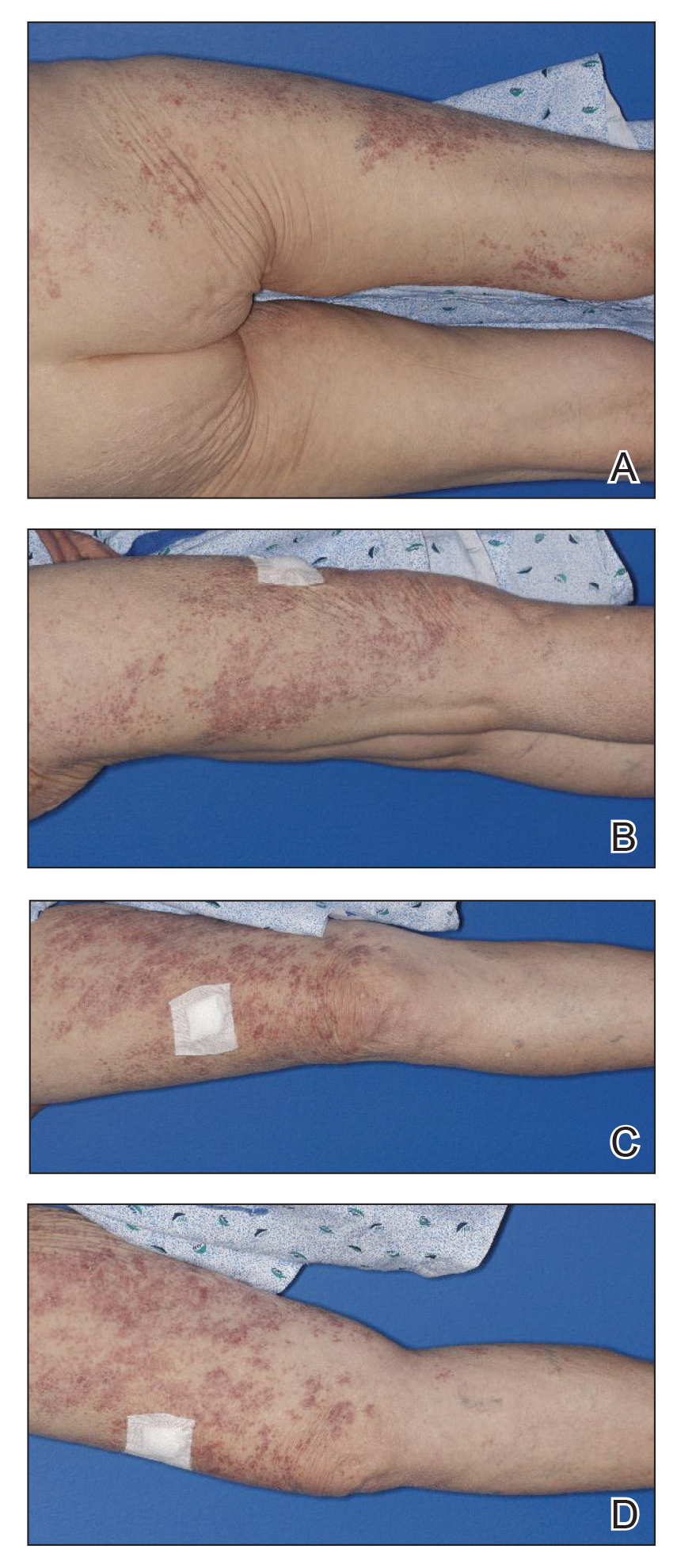

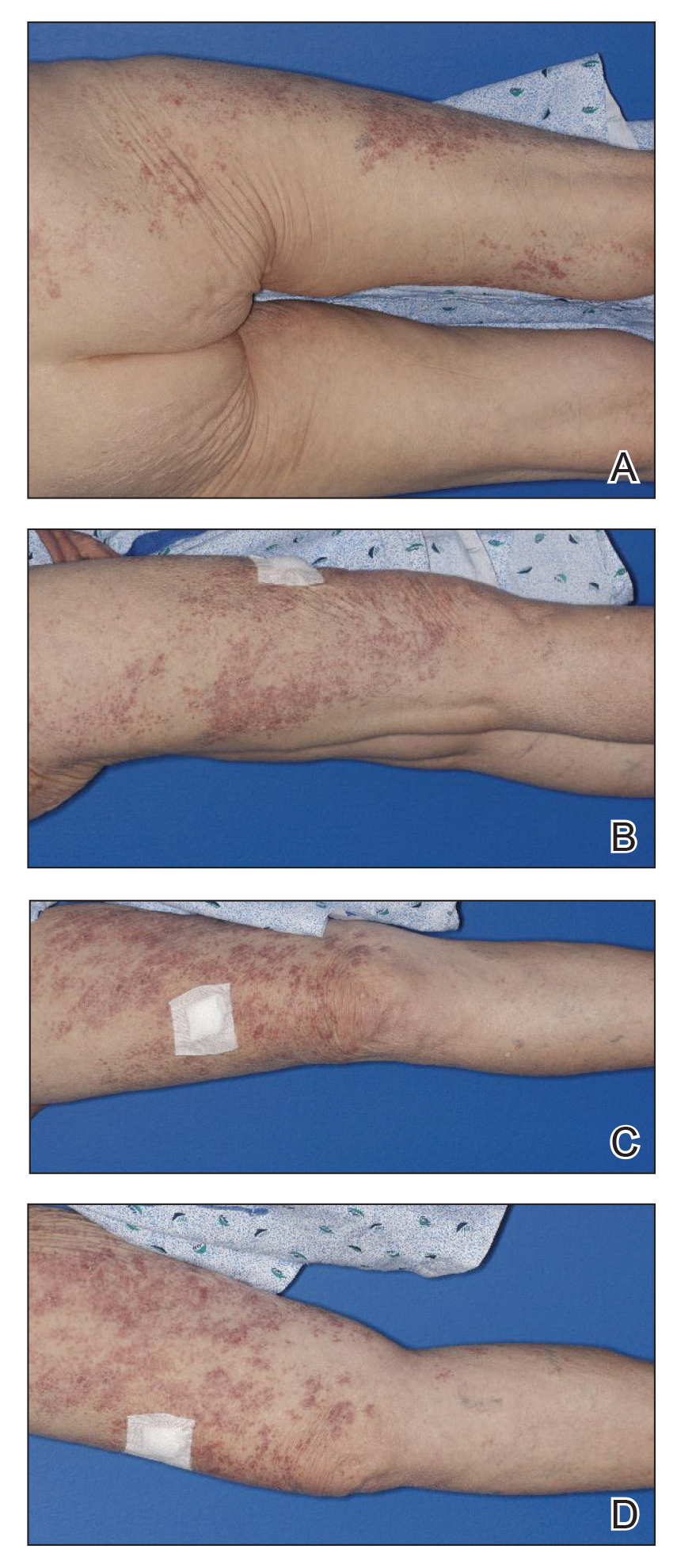

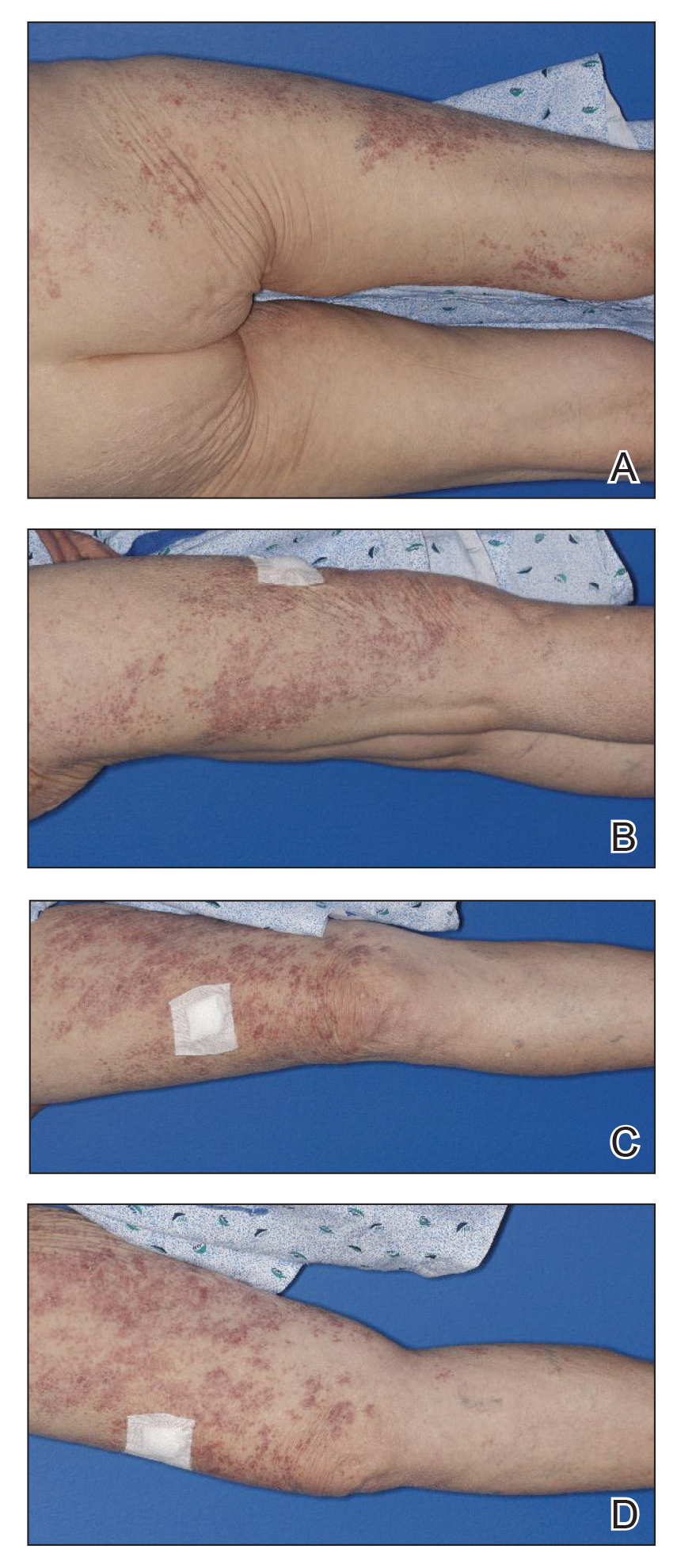

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is a rare benign condition that manifests as tender, indurated, erythematous or violaceous plaques that can develop ulceration and necrosis. It typically occurs in areas susceptible to chronic hypoxia, such as the arms and legs, as was seen in our patient, as well as on large pendulous breasts in females. This condition is a distinct variant of reactive angioendotheliomatosis associated with smoking, trauma, underlying vaso-occlusion, and hypercoagulability.1,2 Risk factors include a history of smoking as well as conditions associated with chronic hypoxia, such as severe peripheral vascular disease, subclavian artery stenosis, hypercoagulable states, monoclonal gammopathy, steal syndrome from an arteriovenous fistula, end-stage renal failure, calciphylaxis, and obesity.1

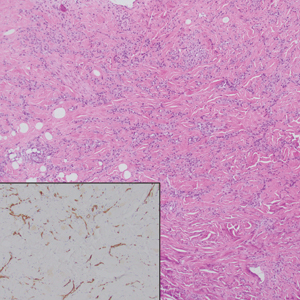

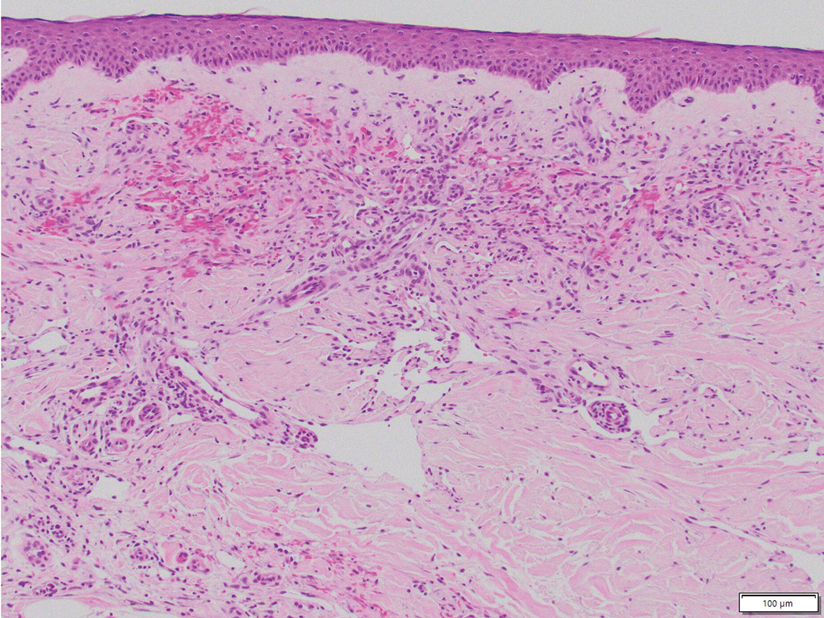

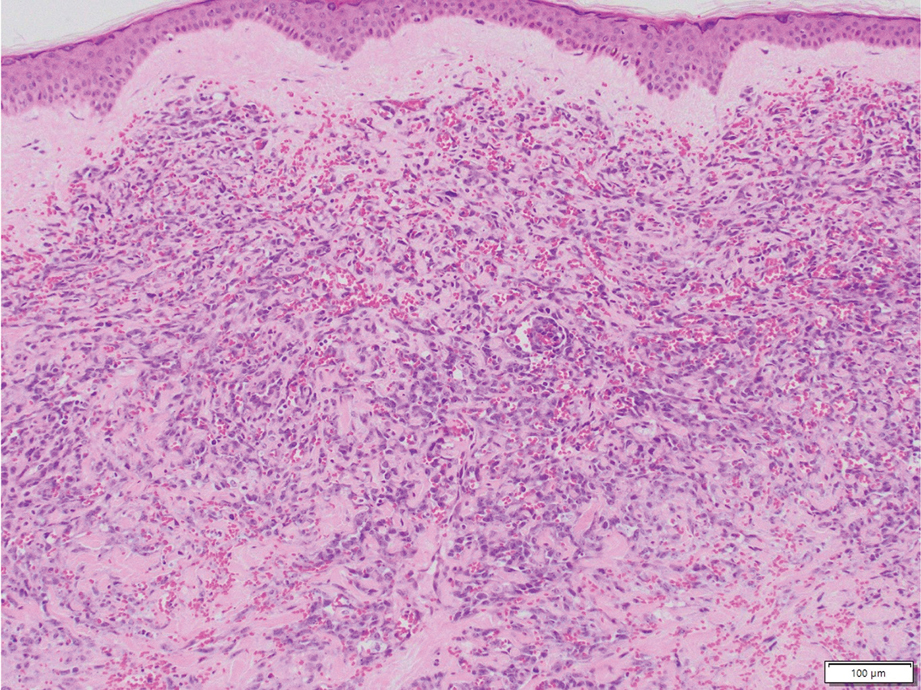

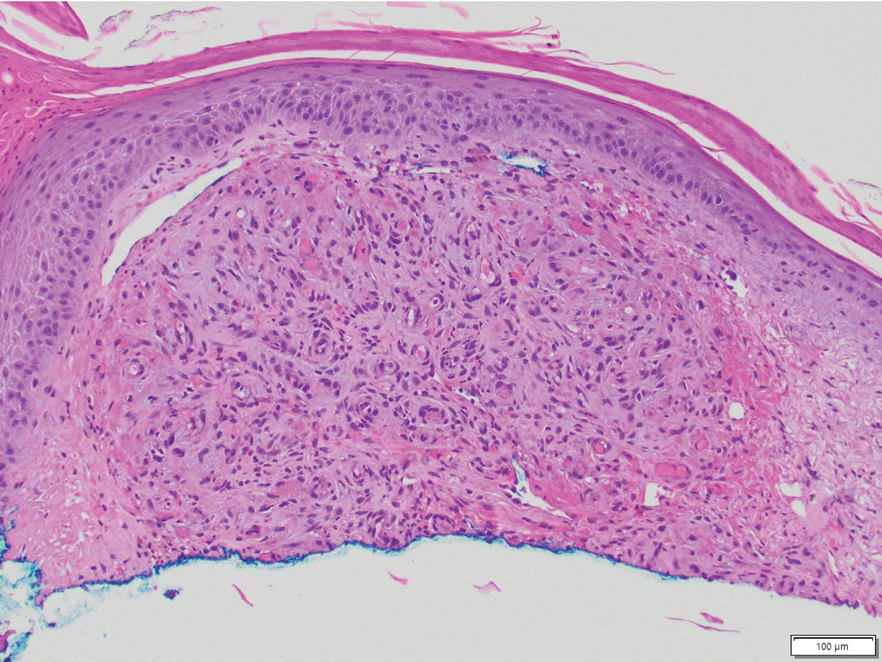

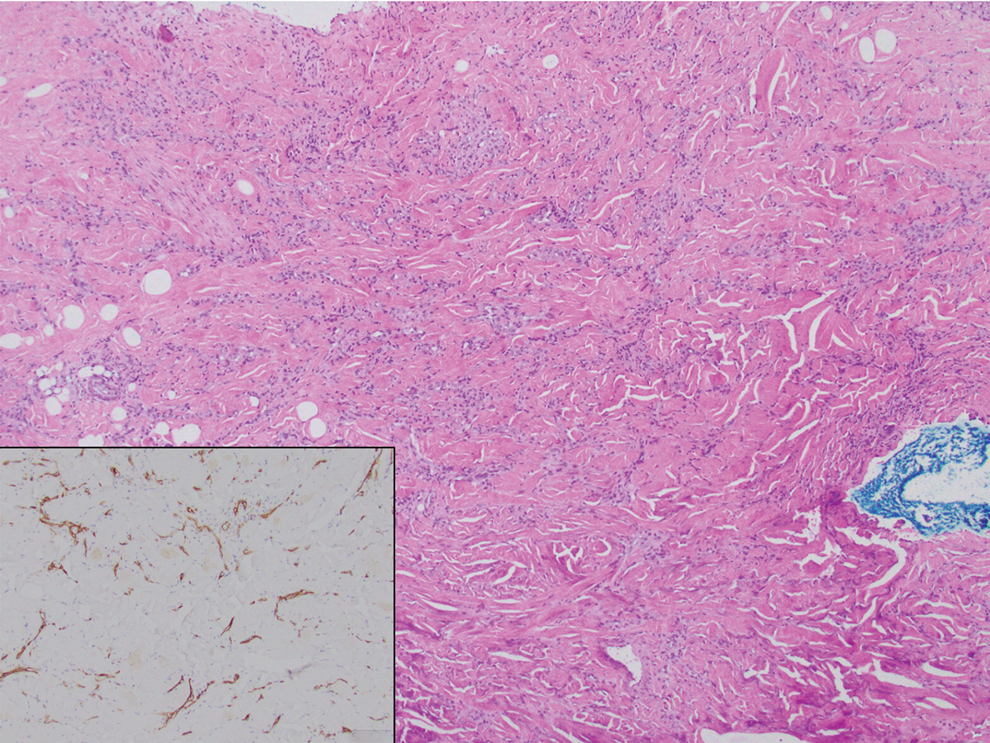

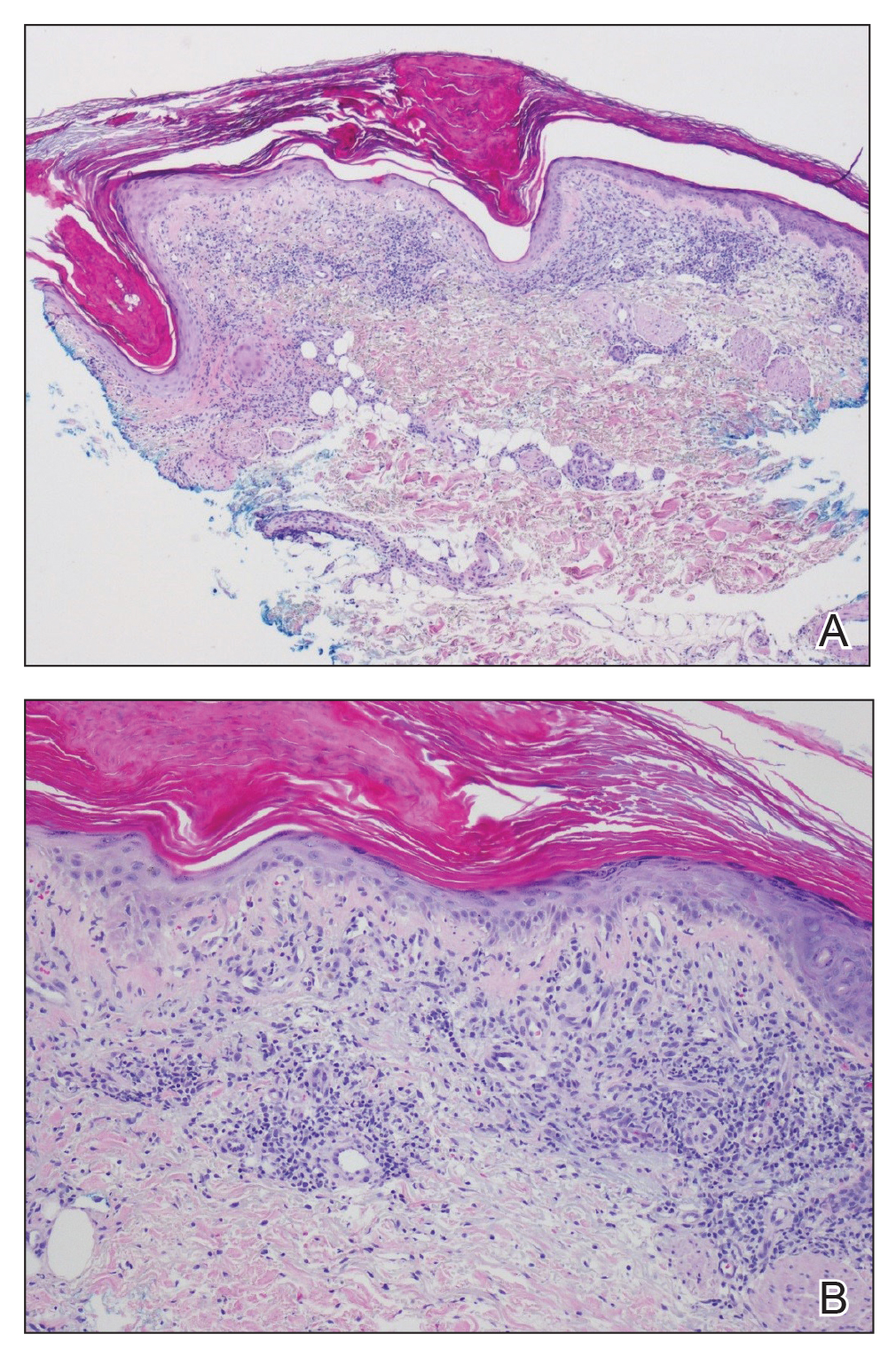

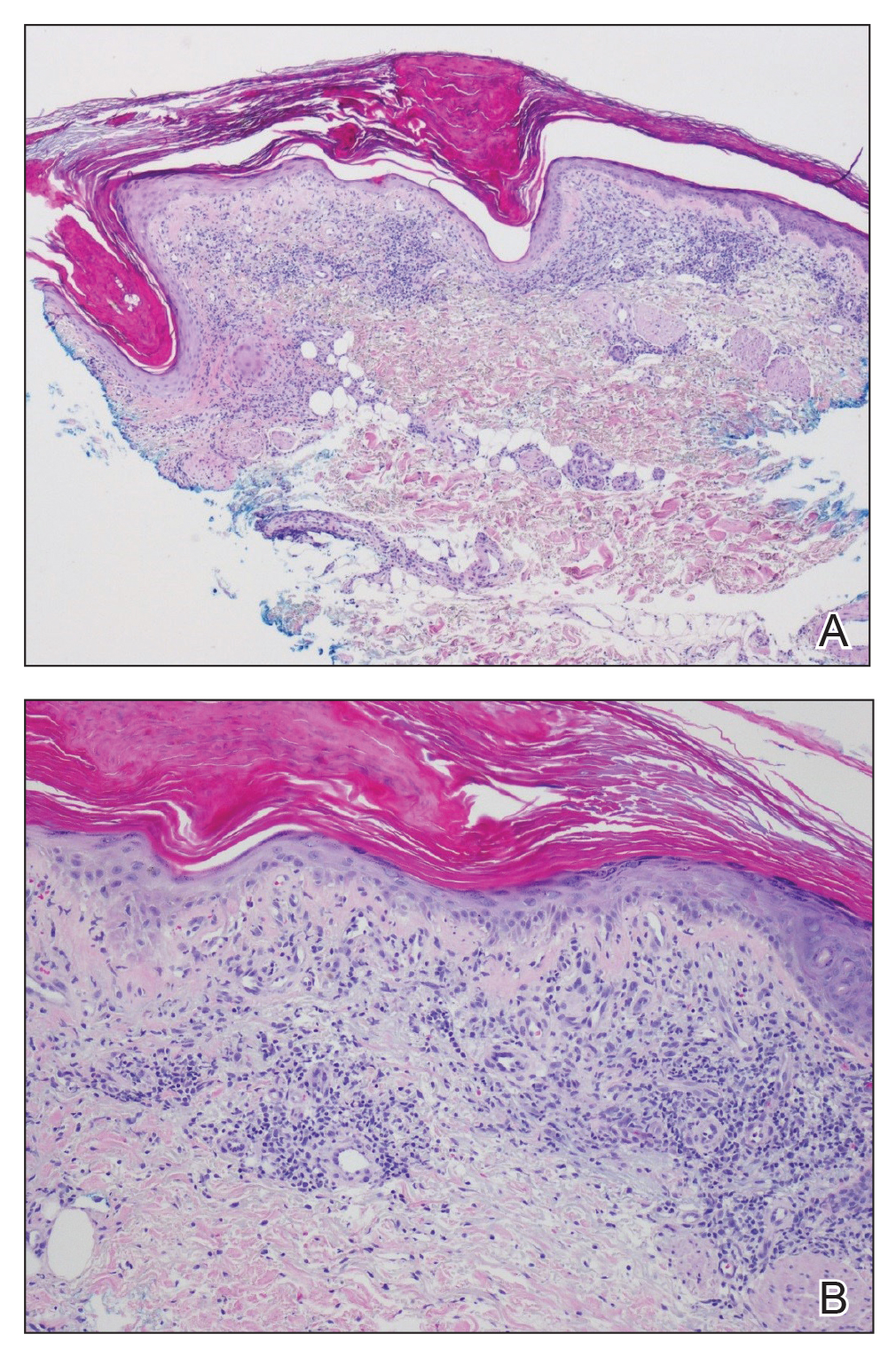

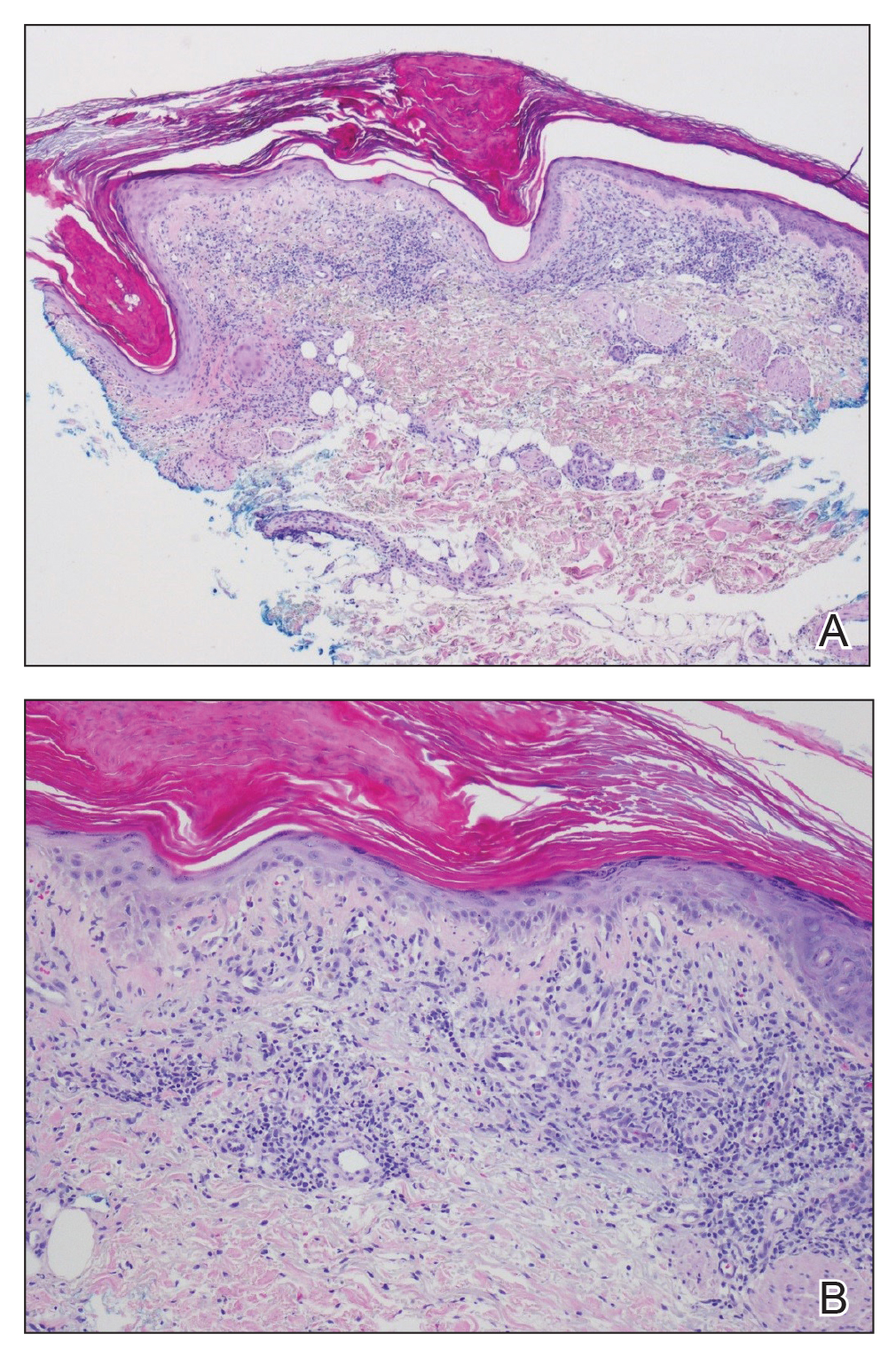

Histopathology of DDA reveals a diffuse dermal proliferation of capillaries due to upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor secondary to chronic ischemia and hypoxia.1,2 Small, well-formed capillaries surrounded by pericytes dissect through dermal collagen into the subcutis (eFigure 1). Spindle-shaped cells with vacuolated cytoplasm and scattered extravasated erythrocytes with hemosiderin may be observed.2 Cellular atypia generally is not seen.2,3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is characterized by positive CD31, CD34, and ERG immunostaining1 and HHV-8 and D2-40 negativity.2 In our patient, the areas suggestive of connective tissue calciumlike depositions were concerning for dystrophic calcification related to end-stage renal disease. Although Von Kossa staining failed to highlight vascular calcifications, early calciphylaxis from end-stage renal disease could not be excluded.

The main goal of DDA treatment is to target tissue hypoxia, and primary preventive measures aim to reduce risk factors associated with atherosclerosis.1 Treatment options for DDA include revascularization, reduction mammoplasty, excision, isotretinoin, oral corticosteroids, smoking cessation, pentoxifylline plus aspirin, and management of underlying calciphylaxis.1,2 Spontaneous resolution of DDA rarely has been reported.1

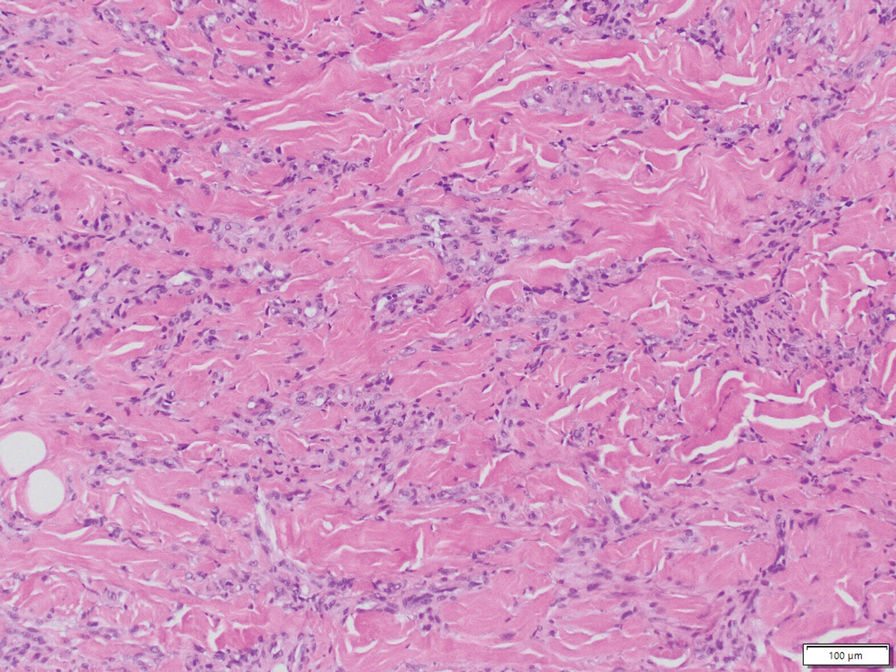

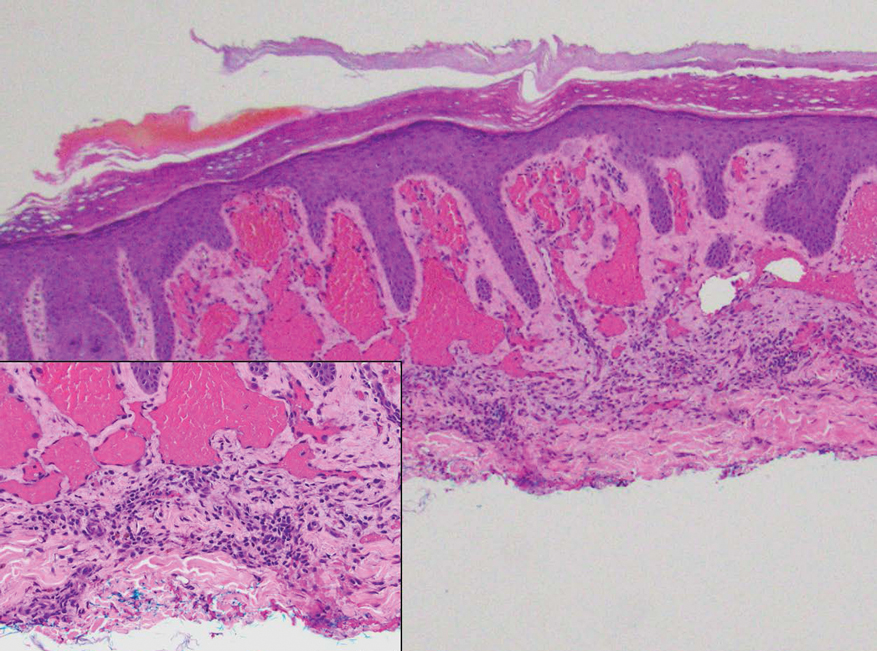

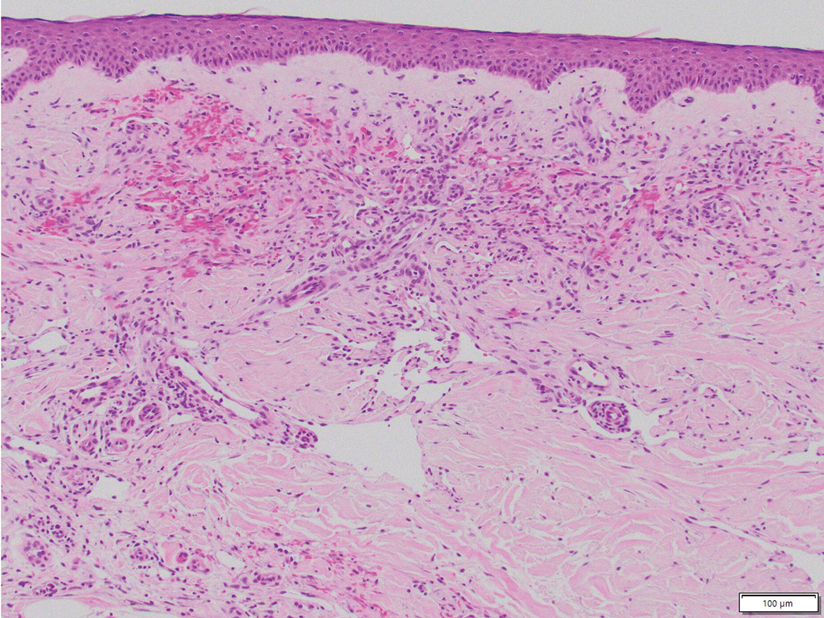

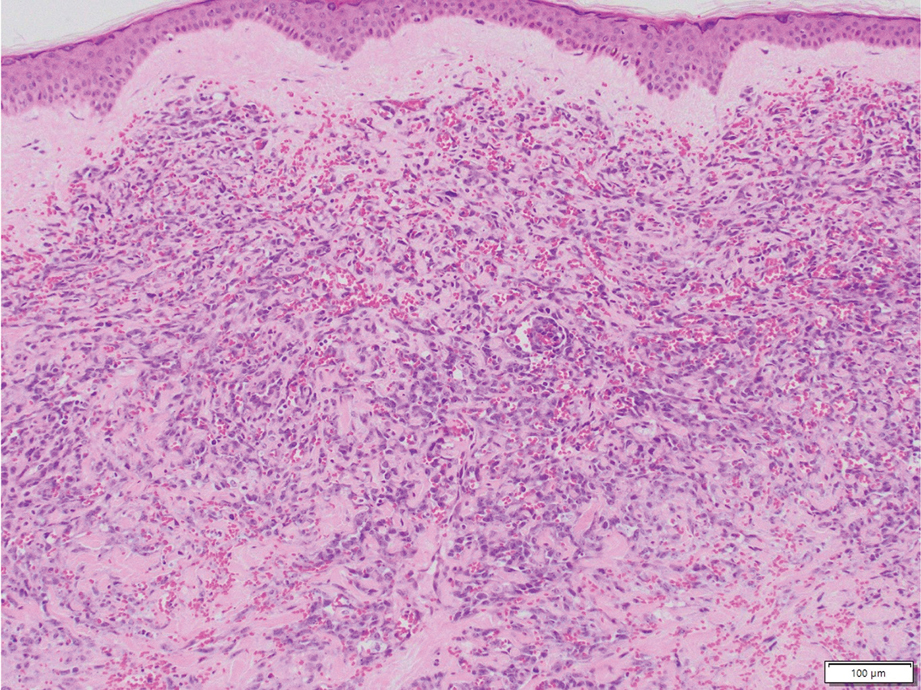

Acroangiodermatitis, also known as pseudo–Kaposi sarcoma (KS), is a rare angioproliferative disorder that often is associated with vascular anomalies.4,5 It is divided into 2 main variants: Mali type, which is associated with chronic venous insufficiency, and Stewart-Bluefarb type, associated with arteriovenous malformations.4 This condition is characterized by red to violaceous macules, papules, or plaques that may become ulcerated or coalesce to form larger confluent patches, typically arising on the lower extremities.4,6,7 Histopathology of acroangiodermatitis reveals circumscribed lobular proliferation of thick-walled dermal vessels (eFigure 2), in contrast to the diffuse dermal proliferation of endothelial cells between collagen bundles seen in DDA.2,3,6

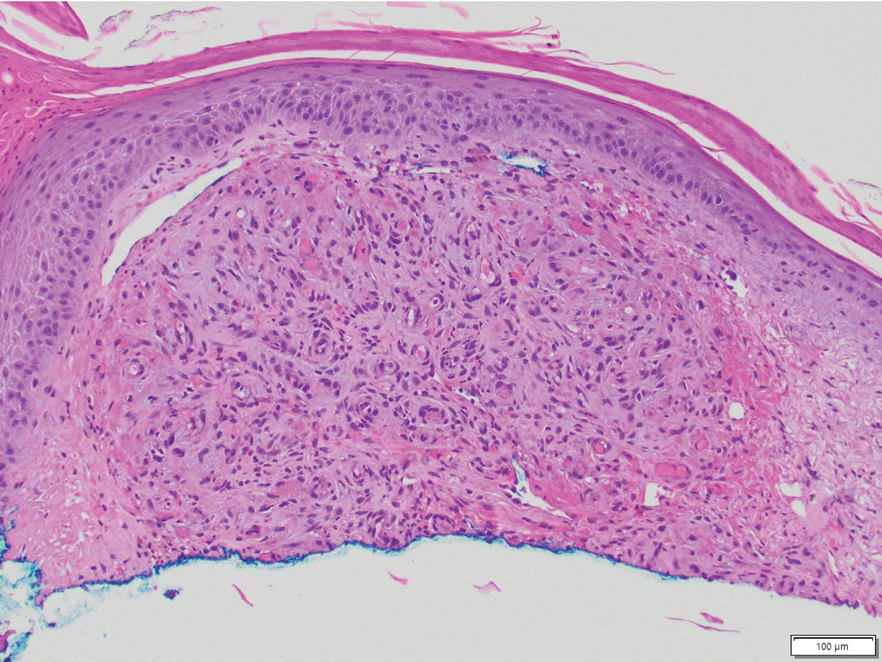

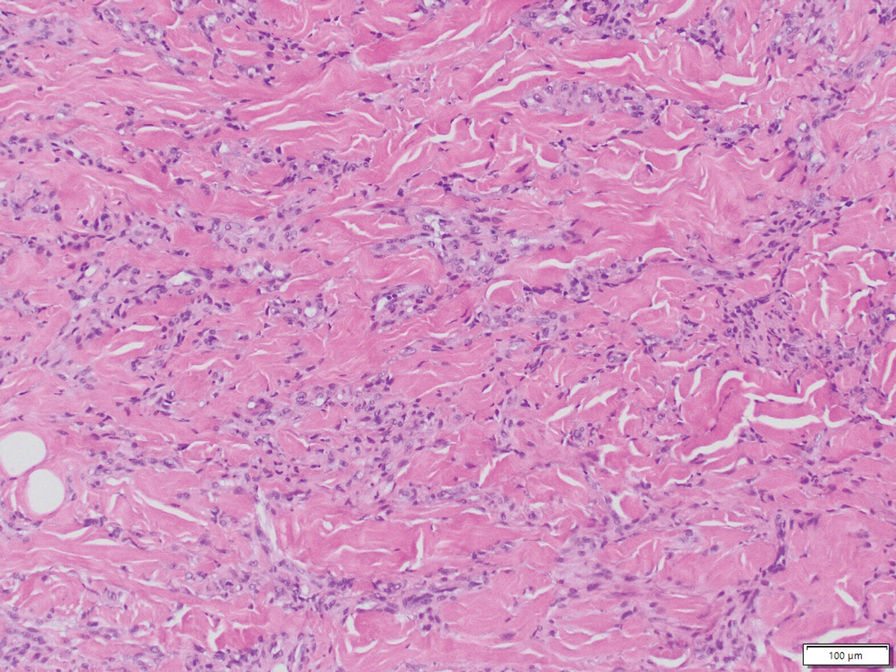

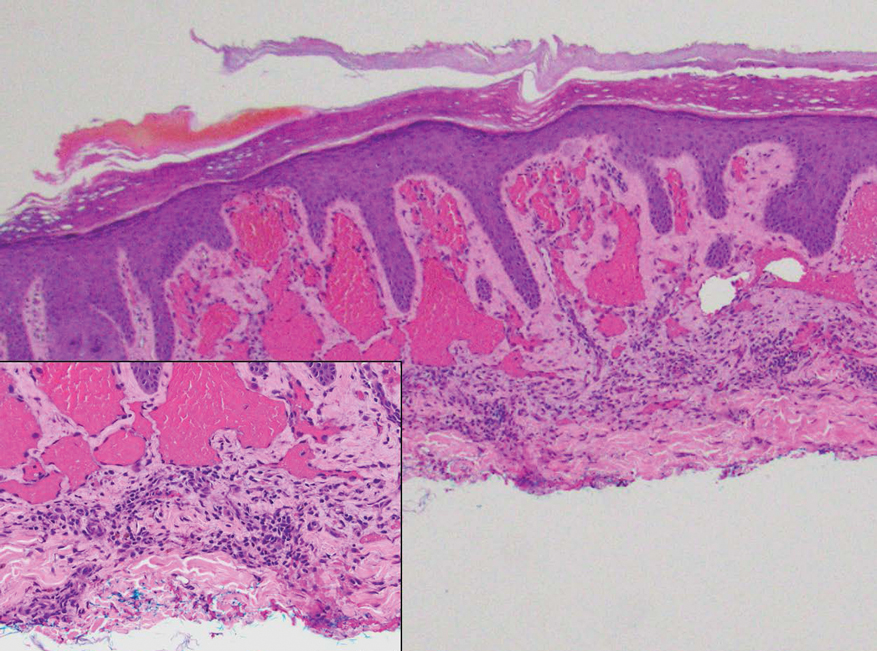

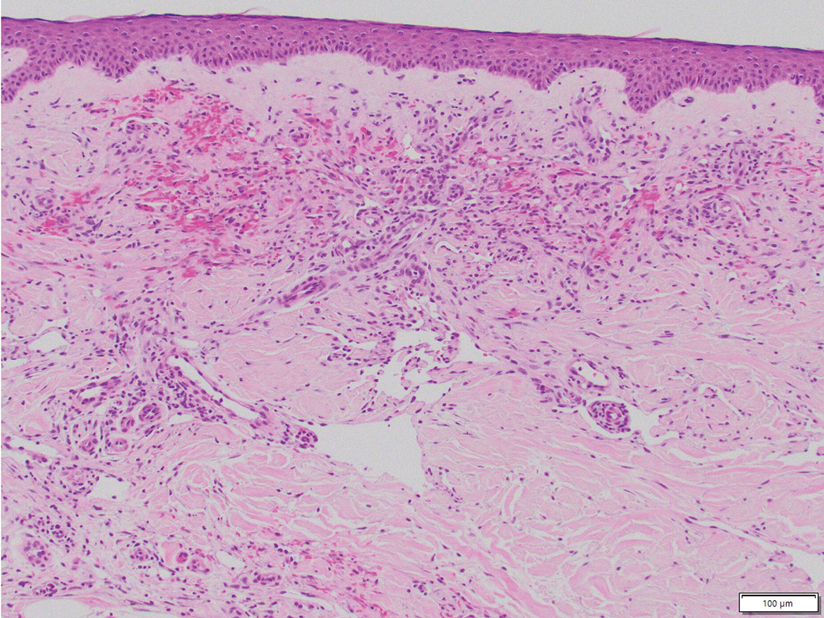

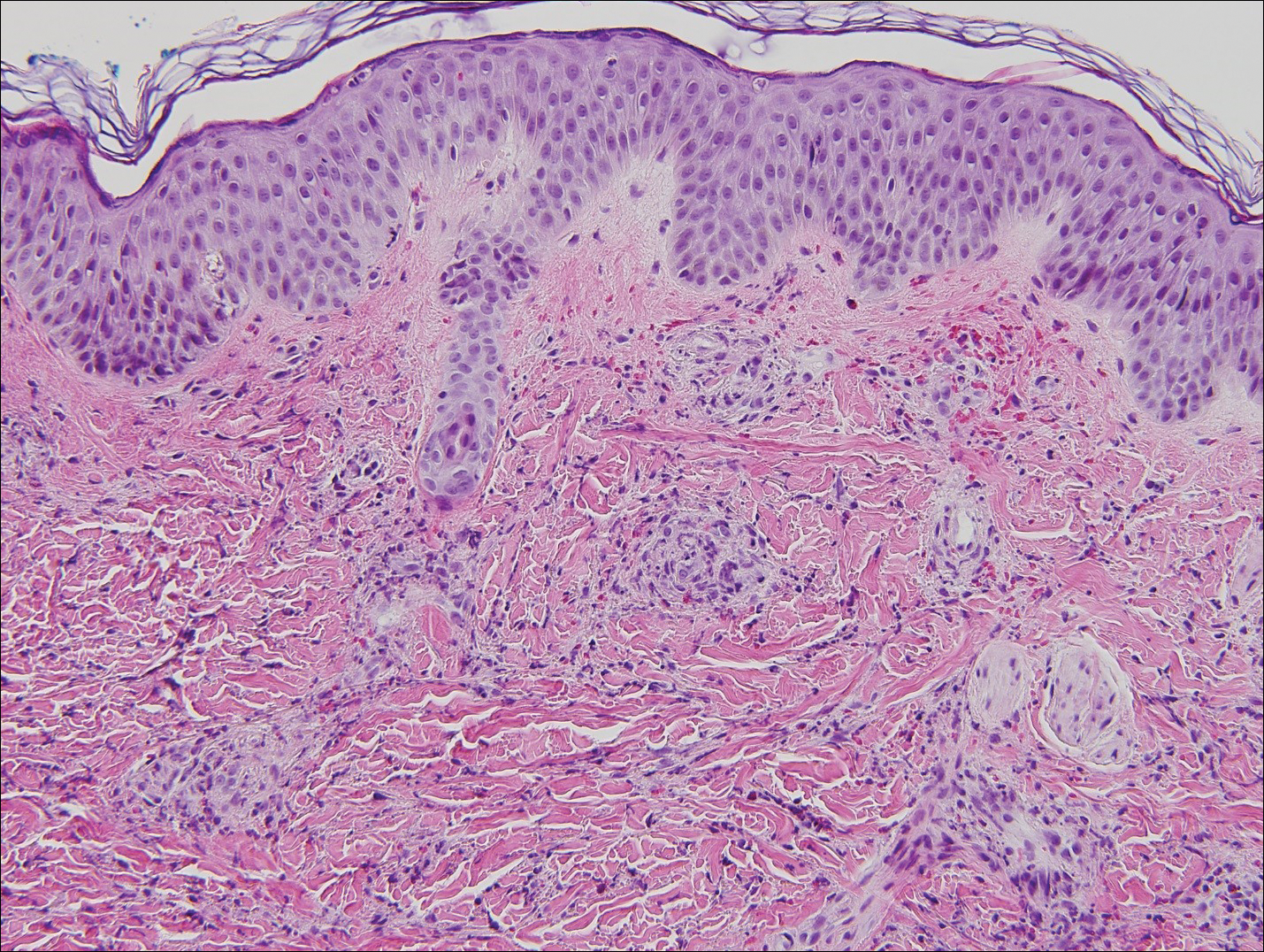

Angiosarcoma is a rare, highly aggressive vascular tumor that originates from vascular or lymphatic endothelial cells. It typically manifests with raised, bruiselike, erythematous to violaceous papules or plaques.8,9 Histopathologically, the hallmark feature of angiosarcoma is abnormal, pleomorphic, malignant endothelial cells with pale, light, eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (eFigure 3).2,9 In poorly differentiated cases, malignant endothelial cells may exhibit an epithelioid morphology with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis.9 Immunohistochemistry is positive for ERG, CD34, CD31, vascular endothelial growth factor, and D2-40.2,9

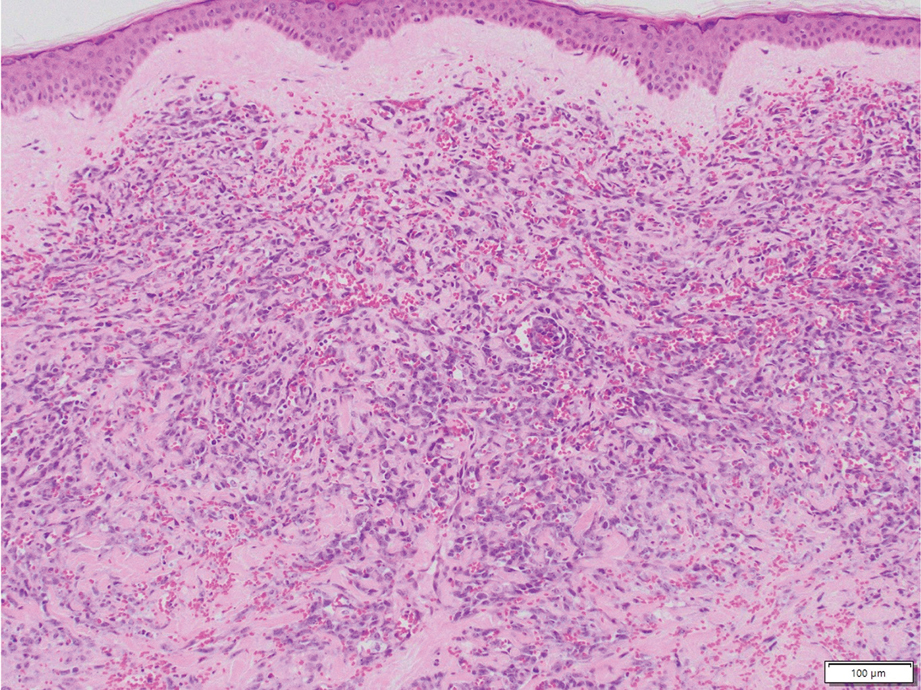

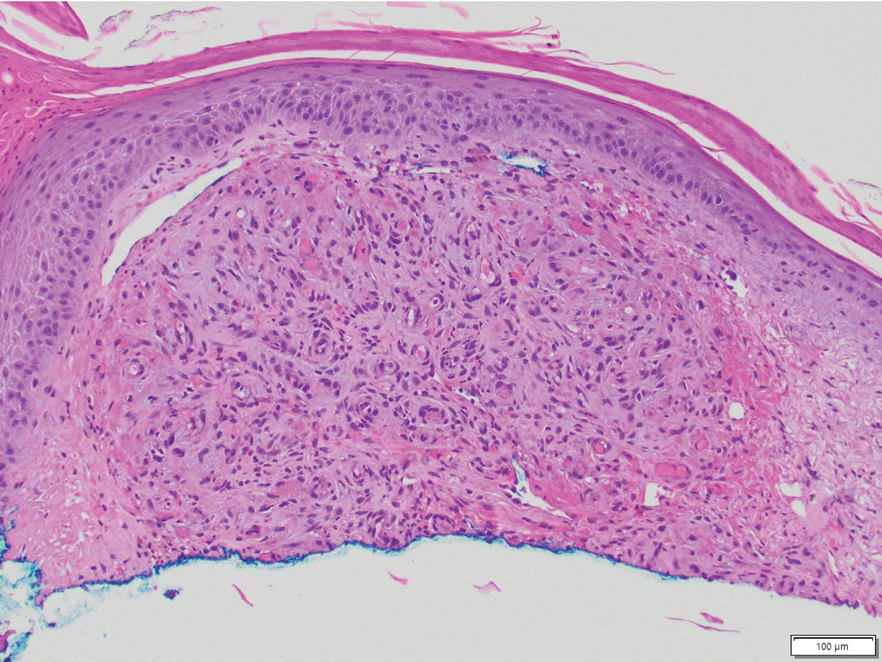

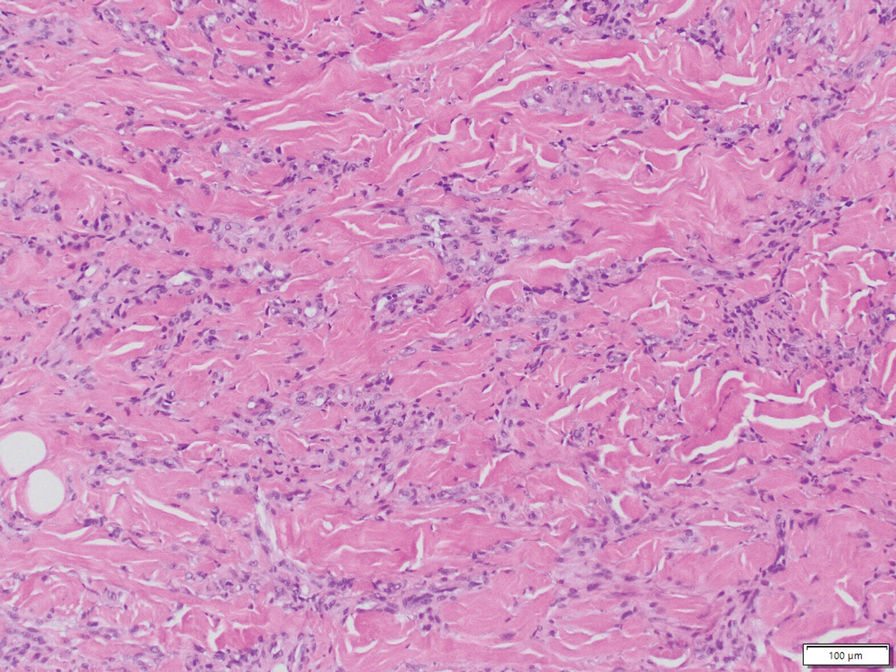

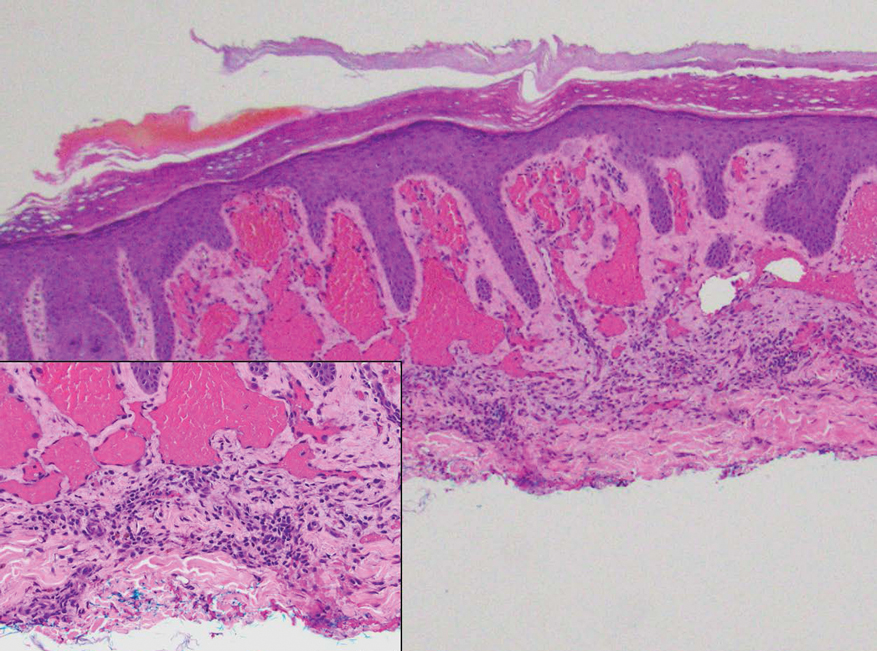

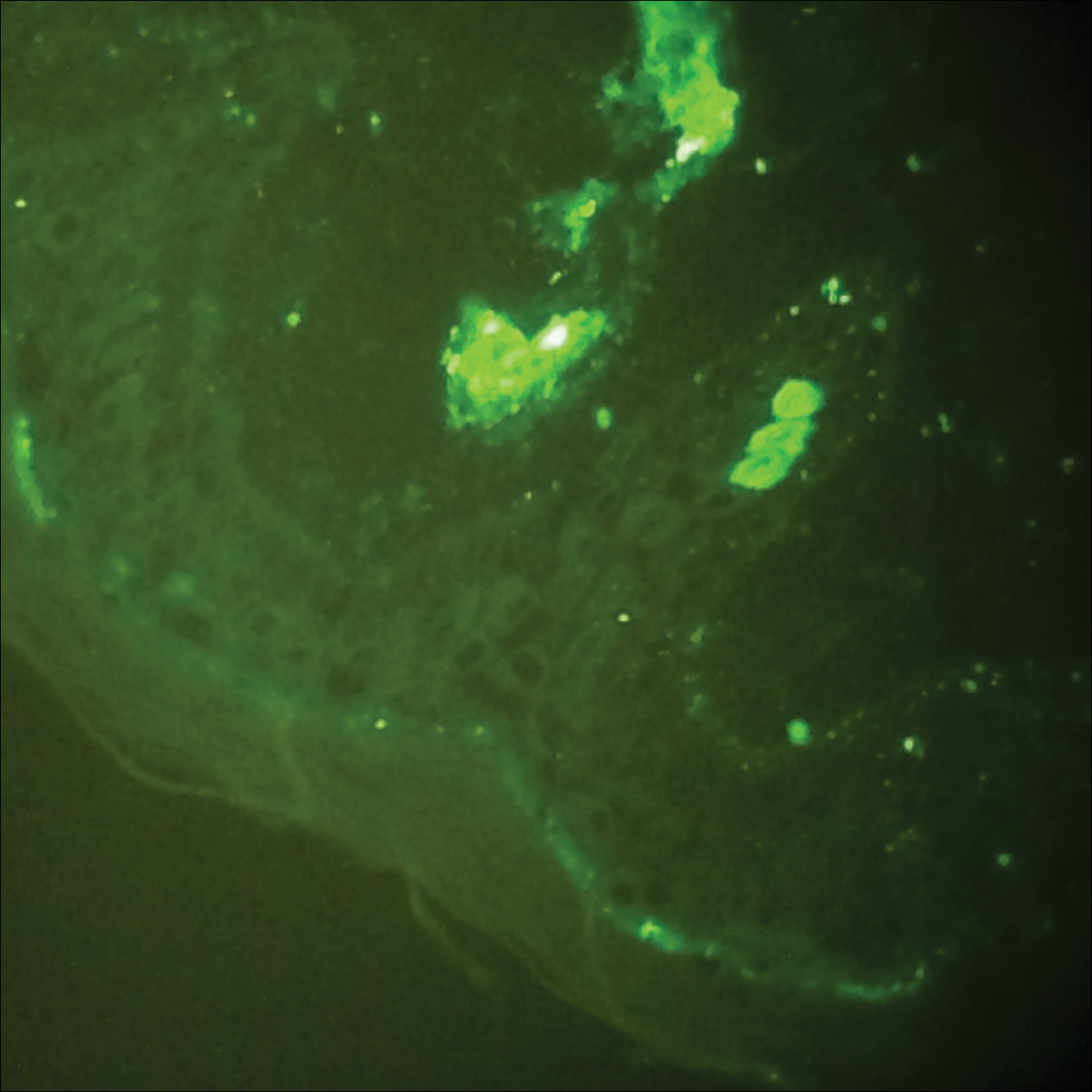

Kaposi sarcoma is a soft tissue malignancy known to occur in immunosuppressed patients such as individuals with AIDS or those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplantation.10 There are 4 major forms of KS: classic (appearing on the lower extremities in elderly men of Mediterranean and Eastern European descent), endemic (occurring in children specifically in Africa with generalized lymph node involvement), HIV/ AIDS–related (occurring in patients not taking highly active antiretroviral therapy with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs), and iatrogenic (occurring in immunosuppressed patients with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs).10,11 Kaposi sarcoma presents as multiple reddish brown, raised or flat, painless, nonblanching mucocutaneous lesions that occasionally can ulcerate and bleed.11 Histopathologic features of KS include vascular proliferation in the dermis with diffuse slitlike lumen formation with the promontory sign, hyaline globules, hemosiderin accumulation, and an inflammatory component that often contains plasma cells (eFigure 4).2,11 Kaposi sarcoma is characterized by positive staining for CD31, CD34, D2-40, and HHV-8; the last 2 are an important distinction from DDA.2

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma, also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular lesion that typically manifests as a solitary, brown to violaceous papule or plaque on the trunk or extremities.12 It is sometimes surrounded by a pale area and a peripheral ecchymotic ring, giving the lesion a targetoid appearance.12,13 Histopathologic features include dilated, thin-walled vessels with prominent endothelial hobnailing in the papillary dermis, slit-shaped vascular channels between collagen bundles in the deeper dermis, and an interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposits (eFigure 5).12,14 The etiology of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma remains unclear. Chronic inflammation, trauma, exposure to ionizing radiation, and vascular obstruction have been suggested as inciting factors, though many cases have been reported without a history of cutaneous injury.12,13 Studies suggest a lymphatic origin instead of its original classification as a hemangioma.13,15 The endothelial cells stain positive with CD31 and may stain with D2-40 and CD34.13,15

- Nguyen N, Silfvast-Kaiser AS, Frieder J, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2020;33:273-275. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1722052

- Frikha F, Boudaya S, Abid N, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast with adjacent fat necrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1vq114n7

- Yang H, Ahmed I, Mathew V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:343-347. doi:10.1001 /archderm.142.3.343

- Chhabra G, Verma P, Khullar G, et al. Acroangiodermatitis, Mali and Stewart-Bluefarb type: two additional cases in adolescents. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62:E156-E157. doi:10.1111/ajd.13386

- Ramírez-Marín HA, Ruben-Castillo C, Barrera-Godínez A, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of the hand secondary to a dysfunctional a rteriovenous fistula. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;77:350.e13-350.e17. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2021.05.042

- Sun L, Duarte S, Soares-de-Almeida L. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali—an unusual cause of painful ulcer. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2023;114:546. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2022.07.013

- Parsi K, O’Connor A, Bester L. Stewart–Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514. doi:10.1177/0268355514548090

- Alharbi A, Kim YC, AlShomer F, et al. Utility of multimodal treatment protocols in the management of scalp cutaneous angiosarcoma. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023;11:E4827. doi:10.1097 /GOX.0000000000004827

- Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, et al. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:983-991. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70023-1

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed January 7, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, et al. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2019;5:1-21. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9

- AbuHilal M, Breslavet M, Ho N, et al. Hobnail hemangioma (superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation) in children: a series of 6 pediatric cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:216-220. doi:10.1177/1203475415612421

- Kakizaki P, Valente NYS, Paiva DLM, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20143264

- Trindade F, Kutzner H, Tellechea Ó, et al. Hobnail hemangioma reclassified as superficial lymphatic malformation: a study of 52 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:112-115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.019

- Hejnold M, Dyduch G, Mojsa I, et al. Hobnail hemangioma: a immunohistochemical study and literature review. Pol J Pathol. 2012;63:189-192. doi:10.5114/pjp.2012.31504

THE DIAGNOSIS: Diffuse Dermal Angiomatosis

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is a rare benign condition that manifests as tender, indurated, erythematous or violaceous plaques that can develop ulceration and necrosis. It typically occurs in areas susceptible to chronic hypoxia, such as the arms and legs, as was seen in our patient, as well as on large pendulous breasts in females. This condition is a distinct variant of reactive angioendotheliomatosis associated with smoking, trauma, underlying vaso-occlusion, and hypercoagulability.1,2 Risk factors include a history of smoking as well as conditions associated with chronic hypoxia, such as severe peripheral vascular disease, subclavian artery stenosis, hypercoagulable states, monoclonal gammopathy, steal syndrome from an arteriovenous fistula, end-stage renal failure, calciphylaxis, and obesity.1

Histopathology of DDA reveals a diffuse dermal proliferation of capillaries due to upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor secondary to chronic ischemia and hypoxia.1,2 Small, well-formed capillaries surrounded by pericytes dissect through dermal collagen into the subcutis (eFigure 1). Spindle-shaped cells with vacuolated cytoplasm and scattered extravasated erythrocytes with hemosiderin may be observed.2 Cellular atypia generally is not seen.2,3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is characterized by positive CD31, CD34, and ERG immunostaining1 and HHV-8 and D2-40 negativity.2 In our patient, the areas suggestive of connective tissue calciumlike depositions were concerning for dystrophic calcification related to end-stage renal disease. Although Von Kossa staining failed to highlight vascular calcifications, early calciphylaxis from end-stage renal disease could not be excluded.

The main goal of DDA treatment is to target tissue hypoxia, and primary preventive measures aim to reduce risk factors associated with atherosclerosis.1 Treatment options for DDA include revascularization, reduction mammoplasty, excision, isotretinoin, oral corticosteroids, smoking cessation, pentoxifylline plus aspirin, and management of underlying calciphylaxis.1,2 Spontaneous resolution of DDA rarely has been reported.1

Acroangiodermatitis, also known as pseudo–Kaposi sarcoma (KS), is a rare angioproliferative disorder that often is associated with vascular anomalies.4,5 It is divided into 2 main variants: Mali type, which is associated with chronic venous insufficiency, and Stewart-Bluefarb type, associated with arteriovenous malformations.4 This condition is characterized by red to violaceous macules, papules, or plaques that may become ulcerated or coalesce to form larger confluent patches, typically arising on the lower extremities.4,6,7 Histopathology of acroangiodermatitis reveals circumscribed lobular proliferation of thick-walled dermal vessels (eFigure 2), in contrast to the diffuse dermal proliferation of endothelial cells between collagen bundles seen in DDA.2,3,6

Angiosarcoma is a rare, highly aggressive vascular tumor that originates from vascular or lymphatic endothelial cells. It typically manifests with raised, bruiselike, erythematous to violaceous papules or plaques.8,9 Histopathologically, the hallmark feature of angiosarcoma is abnormal, pleomorphic, malignant endothelial cells with pale, light, eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (eFigure 3).2,9 In poorly differentiated cases, malignant endothelial cells may exhibit an epithelioid morphology with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis.9 Immunohistochemistry is positive for ERG, CD34, CD31, vascular endothelial growth factor, and D2-40.2,9

Kaposi sarcoma is a soft tissue malignancy known to occur in immunosuppressed patients such as individuals with AIDS or those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplantation.10 There are 4 major forms of KS: classic (appearing on the lower extremities in elderly men of Mediterranean and Eastern European descent), endemic (occurring in children specifically in Africa with generalized lymph node involvement), HIV/ AIDS–related (occurring in patients not taking highly active antiretroviral therapy with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs), and iatrogenic (occurring in immunosuppressed patients with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs).10,11 Kaposi sarcoma presents as multiple reddish brown, raised or flat, painless, nonblanching mucocutaneous lesions that occasionally can ulcerate and bleed.11 Histopathologic features of KS include vascular proliferation in the dermis with diffuse slitlike lumen formation with the promontory sign, hyaline globules, hemosiderin accumulation, and an inflammatory component that often contains plasma cells (eFigure 4).2,11 Kaposi sarcoma is characterized by positive staining for CD31, CD34, D2-40, and HHV-8; the last 2 are an important distinction from DDA.2

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma, also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular lesion that typically manifests as a solitary, brown to violaceous papule or plaque on the trunk or extremities.12 It is sometimes surrounded by a pale area and a peripheral ecchymotic ring, giving the lesion a targetoid appearance.12,13 Histopathologic features include dilated, thin-walled vessels with prominent endothelial hobnailing in the papillary dermis, slit-shaped vascular channels between collagen bundles in the deeper dermis, and an interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposits (eFigure 5).12,14 The etiology of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma remains unclear. Chronic inflammation, trauma, exposure to ionizing radiation, and vascular obstruction have been suggested as inciting factors, though many cases have been reported without a history of cutaneous injury.12,13 Studies suggest a lymphatic origin instead of its original classification as a hemangioma.13,15 The endothelial cells stain positive with CD31 and may stain with D2-40 and CD34.13,15

THE DIAGNOSIS: Diffuse Dermal Angiomatosis

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is a rare benign condition that manifests as tender, indurated, erythematous or violaceous plaques that can develop ulceration and necrosis. It typically occurs in areas susceptible to chronic hypoxia, such as the arms and legs, as was seen in our patient, as well as on large pendulous breasts in females. This condition is a distinct variant of reactive angioendotheliomatosis associated with smoking, trauma, underlying vaso-occlusion, and hypercoagulability.1,2 Risk factors include a history of smoking as well as conditions associated with chronic hypoxia, such as severe peripheral vascular disease, subclavian artery stenosis, hypercoagulable states, monoclonal gammopathy, steal syndrome from an arteriovenous fistula, end-stage renal failure, calciphylaxis, and obesity.1

Histopathology of DDA reveals a diffuse dermal proliferation of capillaries due to upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor secondary to chronic ischemia and hypoxia.1,2 Small, well-formed capillaries surrounded by pericytes dissect through dermal collagen into the subcutis (eFigure 1). Spindle-shaped cells with vacuolated cytoplasm and scattered extravasated erythrocytes with hemosiderin may be observed.2 Cellular atypia generally is not seen.2,3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is characterized by positive CD31, CD34, and ERG immunostaining1 and HHV-8 and D2-40 negativity.2 In our patient, the areas suggestive of connective tissue calciumlike depositions were concerning for dystrophic calcification related to end-stage renal disease. Although Von Kossa staining failed to highlight vascular calcifications, early calciphylaxis from end-stage renal disease could not be excluded.

The main goal of DDA treatment is to target tissue hypoxia, and primary preventive measures aim to reduce risk factors associated with atherosclerosis.1 Treatment options for DDA include revascularization, reduction mammoplasty, excision, isotretinoin, oral corticosteroids, smoking cessation, pentoxifylline plus aspirin, and management of underlying calciphylaxis.1,2 Spontaneous resolution of DDA rarely has been reported.1

Acroangiodermatitis, also known as pseudo–Kaposi sarcoma (KS), is a rare angioproliferative disorder that often is associated with vascular anomalies.4,5 It is divided into 2 main variants: Mali type, which is associated with chronic venous insufficiency, and Stewart-Bluefarb type, associated with arteriovenous malformations.4 This condition is characterized by red to violaceous macules, papules, or plaques that may become ulcerated or coalesce to form larger confluent patches, typically arising on the lower extremities.4,6,7 Histopathology of acroangiodermatitis reveals circumscribed lobular proliferation of thick-walled dermal vessels (eFigure 2), in contrast to the diffuse dermal proliferation of endothelial cells between collagen bundles seen in DDA.2,3,6

Angiosarcoma is a rare, highly aggressive vascular tumor that originates from vascular or lymphatic endothelial cells. It typically manifests with raised, bruiselike, erythematous to violaceous papules or plaques.8,9 Histopathologically, the hallmark feature of angiosarcoma is abnormal, pleomorphic, malignant endothelial cells with pale, light, eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (eFigure 3).2,9 In poorly differentiated cases, malignant endothelial cells may exhibit an epithelioid morphology with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis.9 Immunohistochemistry is positive for ERG, CD34, CD31, vascular endothelial growth factor, and D2-40.2,9

Kaposi sarcoma is a soft tissue malignancy known to occur in immunosuppressed patients such as individuals with AIDS or those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplantation.10 There are 4 major forms of KS: classic (appearing on the lower extremities in elderly men of Mediterranean and Eastern European descent), endemic (occurring in children specifically in Africa with generalized lymph node involvement), HIV/ AIDS–related (occurring in patients not taking highly active antiretroviral therapy with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs), and iatrogenic (occurring in immunosuppressed patients with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs).10,11 Kaposi sarcoma presents as multiple reddish brown, raised or flat, painless, nonblanching mucocutaneous lesions that occasionally can ulcerate and bleed.11 Histopathologic features of KS include vascular proliferation in the dermis with diffuse slitlike lumen formation with the promontory sign, hyaline globules, hemosiderin accumulation, and an inflammatory component that often contains plasma cells (eFigure 4).2,11 Kaposi sarcoma is characterized by positive staining for CD31, CD34, D2-40, and HHV-8; the last 2 are an important distinction from DDA.2

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma, also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular lesion that typically manifests as a solitary, brown to violaceous papule or plaque on the trunk or extremities.12 It is sometimes surrounded by a pale area and a peripheral ecchymotic ring, giving the lesion a targetoid appearance.12,13 Histopathologic features include dilated, thin-walled vessels with prominent endothelial hobnailing in the papillary dermis, slit-shaped vascular channels between collagen bundles in the deeper dermis, and an interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposits (eFigure 5).12,14 The etiology of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma remains unclear. Chronic inflammation, trauma, exposure to ionizing radiation, and vascular obstruction have been suggested as inciting factors, though many cases have been reported without a history of cutaneous injury.12,13 Studies suggest a lymphatic origin instead of its original classification as a hemangioma.13,15 The endothelial cells stain positive with CD31 and may stain with D2-40 and CD34.13,15

- Nguyen N, Silfvast-Kaiser AS, Frieder J, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2020;33:273-275. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1722052

- Frikha F, Boudaya S, Abid N, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast with adjacent fat necrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1vq114n7

- Yang H, Ahmed I, Mathew V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:343-347. doi:10.1001 /archderm.142.3.343

- Chhabra G, Verma P, Khullar G, et al. Acroangiodermatitis, Mali and Stewart-Bluefarb type: two additional cases in adolescents. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62:E156-E157. doi:10.1111/ajd.13386

- Ramírez-Marín HA, Ruben-Castillo C, Barrera-Godínez A, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of the hand secondary to a dysfunctional a rteriovenous fistula. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;77:350.e13-350.e17. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2021.05.042

- Sun L, Duarte S, Soares-de-Almeida L. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali—an unusual cause of painful ulcer. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2023;114:546. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2022.07.013

- Parsi K, O’Connor A, Bester L. Stewart–Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514. doi:10.1177/0268355514548090

- Alharbi A, Kim YC, AlShomer F, et al. Utility of multimodal treatment protocols in the management of scalp cutaneous angiosarcoma. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023;11:E4827. doi:10.1097 /GOX.0000000000004827

- Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, et al. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:983-991. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70023-1

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed January 7, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, et al. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2019;5:1-21. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9

- AbuHilal M, Breslavet M, Ho N, et al. Hobnail hemangioma (superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation) in children: a series of 6 pediatric cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:216-220. doi:10.1177/1203475415612421

- Kakizaki P, Valente NYS, Paiva DLM, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20143264

- Trindade F, Kutzner H, Tellechea Ó, et al. Hobnail hemangioma reclassified as superficial lymphatic malformation: a study of 52 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:112-115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.019

- Hejnold M, Dyduch G, Mojsa I, et al. Hobnail hemangioma: a immunohistochemical study and literature review. Pol J Pathol. 2012;63:189-192. doi:10.5114/pjp.2012.31504

- Nguyen N, Silfvast-Kaiser AS, Frieder J, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2020;33:273-275. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1722052

- Frikha F, Boudaya S, Abid N, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast with adjacent fat necrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1vq114n7

- Yang H, Ahmed I, Mathew V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:343-347. doi:10.1001 /archderm.142.3.343

- Chhabra G, Verma P, Khullar G, et al. Acroangiodermatitis, Mali and Stewart-Bluefarb type: two additional cases in adolescents. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62:E156-E157. doi:10.1111/ajd.13386

- Ramírez-Marín HA, Ruben-Castillo C, Barrera-Godínez A, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of the hand secondary to a dysfunctional a rteriovenous fistula. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;77:350.e13-350.e17. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2021.05.042

- Sun L, Duarte S, Soares-de-Almeida L. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali—an unusual cause of painful ulcer. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2023;114:546. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2022.07.013

- Parsi K, O’Connor A, Bester L. Stewart–Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514. doi:10.1177/0268355514548090

- Alharbi A, Kim YC, AlShomer F, et al. Utility of multimodal treatment protocols in the management of scalp cutaneous angiosarcoma. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023;11:E4827. doi:10.1097 /GOX.0000000000004827

- Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, et al. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:983-991. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70023-1

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed January 7, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, et al. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2019;5:1-21. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9

- AbuHilal M, Breslavet M, Ho N, et al. Hobnail hemangioma (superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation) in children: a series of 6 pediatric cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:216-220. doi:10.1177/1203475415612421

- Kakizaki P, Valente NYS, Paiva DLM, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20143264

- Trindade F, Kutzner H, Tellechea Ó, et al. Hobnail hemangioma reclassified as superficial lymphatic malformation: a study of 52 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:112-115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.019

- Hejnold M, Dyduch G, Mojsa I, et al. Hobnail hemangioma: a immunohistochemical study and literature review. Pol J Pathol. 2012;63:189-192. doi:10.5114/pjp.2012.31504

Painful Ulcers on the Elbows, Knees, and Ankles

Painful Ulcers on the Elbows, Knees, and Ankles

A 46-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus and end-stage renal disease presented to the dermatology department with painful ulcers on the extensor surfaces of the elbows, knees, and ankles of 2 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed angulated ulcers with surrounding pink erythema. A 4-mm punch biopsy and CD31 immunostaining of the left knee revealed dystrophic elastic fibers and purplish calciumlike depositions on connective tissue fibers in the mid to deep dermis.

What’s Eating You? Carpet Beetles (Dermestidae)

Carpet beetle larvae of the family Dermestidae have been documented to cause both acute and delayed hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals. These larvae have specialized horizontal rows of spear-shaped hairs called hastisetae, which detach easily into the surrounding environment and are small enough to travel by air. Exposure to hastisetae has been tied to adverse effects ranging from dermatitis to rhinoconjunctivitis and acute asthma, with treatment being mostly empiric and symptom based. Due to the pervasiveness of carpet beetles in homes, improved awareness of dermestid-induced manifestations is valuable for clinicians.

Beetles in the Dermestidae family do not bite humans but have been reported to cause skin reactions in addition to other symptoms typical of an allergic reaction. Skin contact with larval hairs (hastisetae) of these insects—known as carpet, larder, or hide beetles — may cause urticarial or edematous papules that are mistaken for papular urticaria or arthropod bites. 1 There are approximately 500 to 700 species of carpet beetles worldwide. Carpet beetles are a clinically underrecognized cause of allergic contact dermatitis given their frequent presence in homes across the world. 2 Carpet beetle larvae feed on shed skin, feathers, hair, wool, book bindings, felt, leather, wood, silk, and sometimes grains and thus can be found nearly anywhere. Most symptom-inducing exposures to Dermestidae beetles occur occupationally, such as in museum curators working hands-on with collection materials and workers handling infested materials such as wool. 3,4 In-home Dermestidae exposure may lead to symptoms, especially if regularly worn clothing and bedding materials are infested. The broad palate of dermestid members has resulted in substantial contamination of stored materials such as flour and fabric in addition to the destruction of museum collections. 5-7

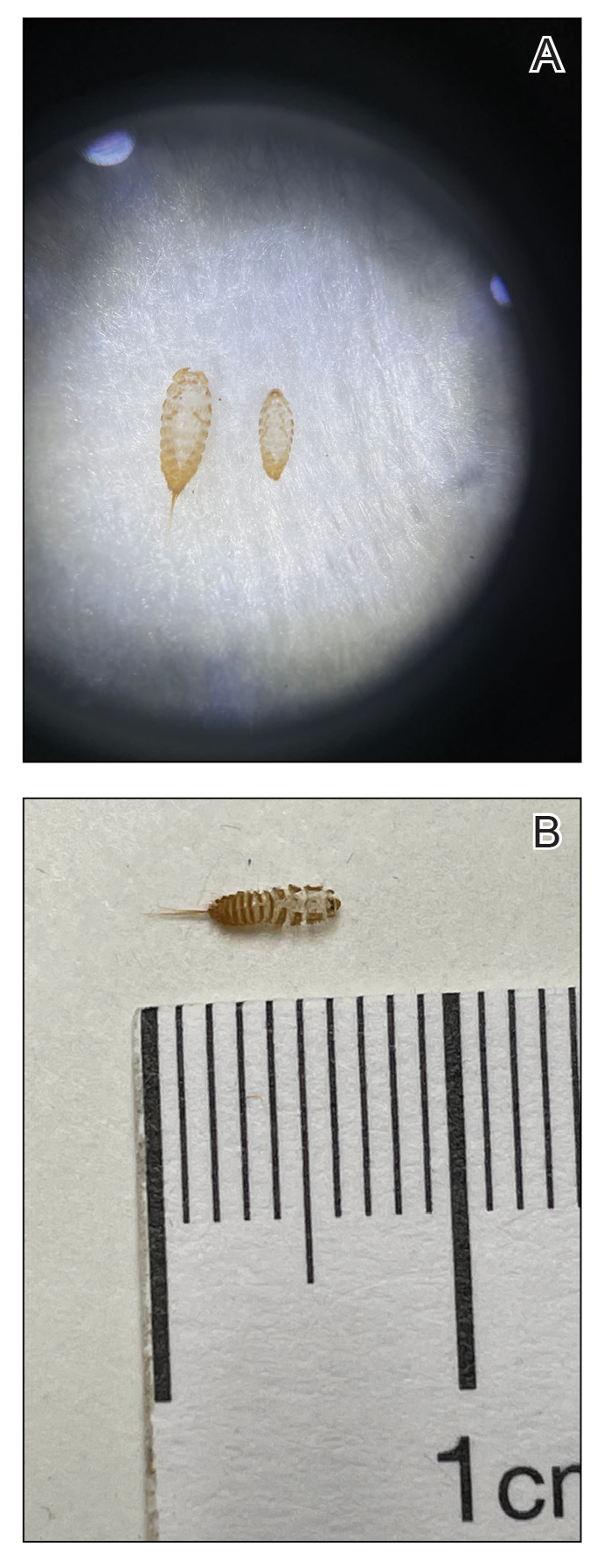

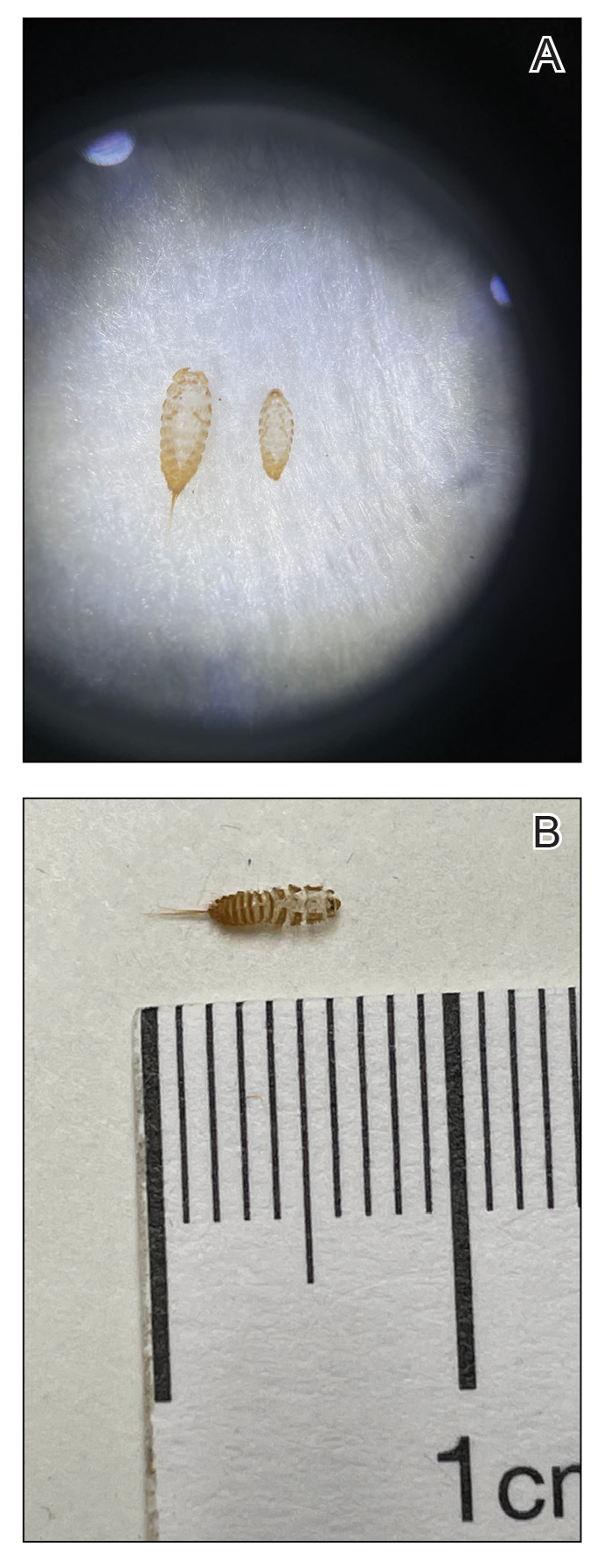

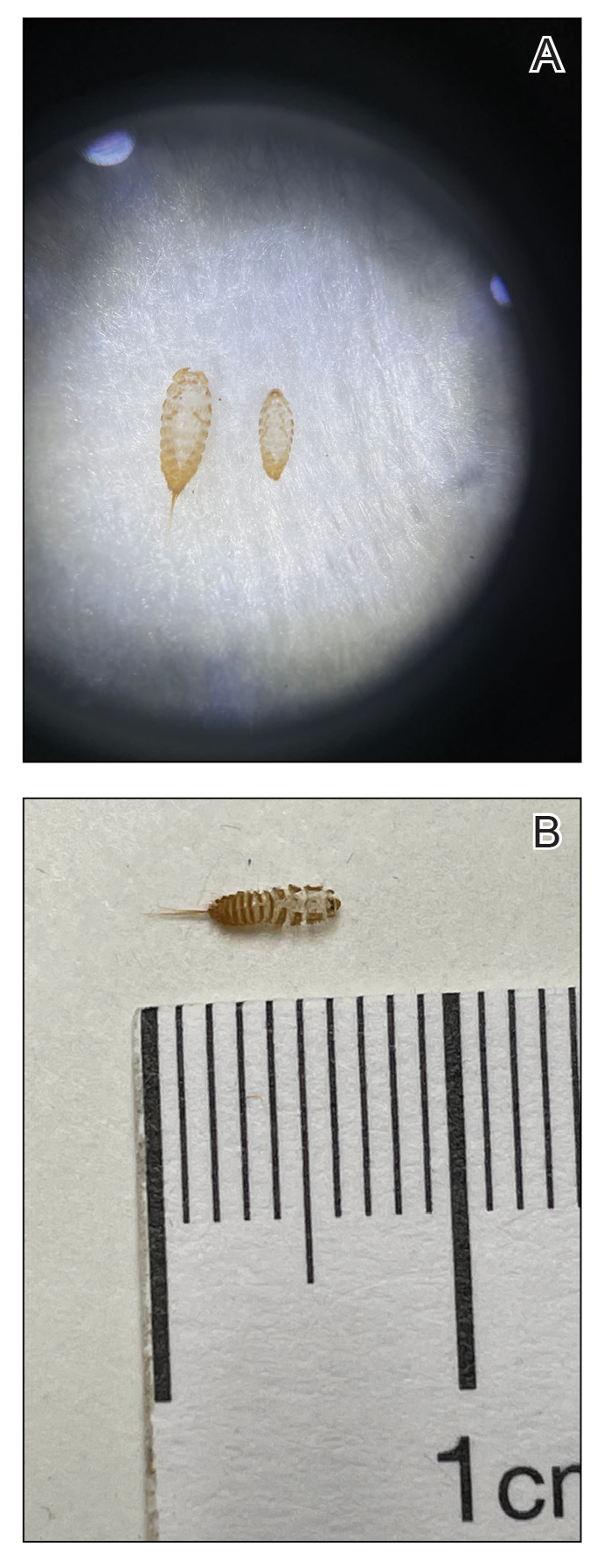

The larvae of some dermestid species, most commonly of the genera Anthrenus and Dermestes, are 2 to 3 mm in length and have detachable hairlike hastisetae that shed into the surrounding environment throughout larval development (Figure 1).8 The hastisetae, located on the thoracic and abdominal segments (tergites), serve as a larval defense mechanism. When prodded, the round, hairy, wormlike larvae tense up and can raise their abdominal tergites while splaying the hastisetae out in a fanlike manner.9 Similar to porcupine quills, the hastisetae easily detach and can entrap the appendages of invertebrate predators. Hastisetae are not known to be sharp enough to puncture human skin, but friction and irritation from skin contact and superficial sticking of the hastisetae into mucous membranes and noncornified epithelium, such as in the bronchial airways, are thought to induce hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals.

Additionally, hastisetae and the exoskeletons of both adult and larval dermestid beetles are composed mostly of chitin, which is highly allergenic. Chitin has been found to play a proinflammatory role in ocular inflammation, asthma, and bronchial reactivity via T helper cell (TH2)–mediated cellular interactions.10-12 Larvae shed their exoskeletons, including hastisetae, multiple times over the course of their development, which contributes to their potential allergen burden (Figure 2). Reports of positive prick and/or patch testing to larval components indicate some cases of both acute type 1 and delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions.4,8,13

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Multiple erythematous urticarial papules, papulopustules, and papulovesicles are the typical manifestations of dermestid dermatitis.3,4,13-16 Figure 3 demonstrates several characteristic edematous papules with background erythema. Unlike the clusters seen with flea and bed bug bites, dermestid-induced lesions typically are single and scattered, with a propensity for exposed limbs and the face. Exposure to hastisetae commonly results in classic allergic symptoms including rhinitis, conjunctivitis, coughing, wheezing, sneezing, and intranasal and periocular pruritus, even in those with no personal history of atopy.17-19 Lymphadenopathy, vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis also have been reported.20 A large infestation in which many individual beetles as well as larvae can be found in 1 or more areas of the inhabited structure has been reported to cause more severe symptoms, including acute eczema, otitis externa, lymphocytic vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis, all of which resolved within 3 months of thorough deinfestation cleaning.21

Skin-prick and/or patch testing is not necessary for this clinical diagnosis of dermestid-induced allergic contact dermatitis. This diagnosis is bolstered by (but does not require a history of) repeated symptom induction upon performing certain activities (eg, handling taxidermy specimens) and/or in certain environments (eg, only at home). Because of individual differences in hypersensitivity to dermestid parts, it is not typical for all members of a household to be affected.

When there are multiple potential suspected allergens or an unknown cause for symptoms despite a detailed history, allergy testing can be useful in confirming a diagnosis and directing management. Immediate-onset type 1 hypersensitivity reactions are evaluated using skin-prick testing or serum IgE levels, whereas delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions can be evaluated using patch testing. Type 1 reactions tend to present with classic allergy symptoms, especially where there are abundant mast cells to degranulate in the skin and mucosa of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts; these symptoms range from mild wheezing, urticaria, periorbital pruritus, and sneezing to outright asthma, diarrhea, rhinoconjunctivitis, and even anaphylaxis. With these reactions, initial exposure to an antigen such as chitin in the hastisetae leads to an asymptomatic sensitization against the antigen in which its introduction leads to a TH2-skewed cellular response, which promotes B-cell production of IgE antibodies. Upon subsequent exposure to this antigen, IgE antibodies bound to mast cells will lead them to degranulate with release of histamine and other proinflammatory molecules, resulting in clinical manifestations. The skin-prick test relies on introduction of potential antigens through the epidermis into the dermis with a sharp lancet to induce IgE antibody activation and then degranulation of the patient’s mast cells, resulting in a pruritic erythematous wheal. This IgE-mediated process has been shown to occur in response to dermestid larval parts among household dust, resulting in chronic coughing, sneezing, nasal pruritus, and asthma.15,17,22

Type 4 hypersensitivity reactions are T-cell mediated and also include a sensitization phase followed by symptom manifestation upon repeat exposure; however, these reactions usually are not immediate and can take up to 72 hours after exposure to manifest.23 This is because T cells specific to the antigen do not lead a process resulting in antibodies but instead recruit numerous other TH1-polarized mediators upon re-exposure to activate cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and macrophages to attempt to neutralize the antigen. Many type 4 reactions result in mostly cutaneous manifestations, such as contact dermatitis. Patch testing involves adhering potential allergens to the skin for a time with assessments at regular intervals to evaluate the level of reaction from weakly positive to severe. At minimum, most reports of dermestid-related manifestations include a rash such as erythematous papules, and several published cases involving patch testing have yielded positive results to various preparations of larval parts.3,14,21

Management and Treatment

Prevention of dermestid exposure is difficult given the myriad materials eaten by the larvae. An insect exterminator should verify and treat a carpet beetle infestation, while a dermatologist can treat symptomatic individuals. Treatment is driven by the severity of the patient’s discomfort and is aimed at both symptomatic relief and reducing dermestid exposure moving forward. Although in certain environments it will be nearly impossible to eradicate Dermestidae, cleaning thoroughly and regularly may go far to reduce exposure and associated symptoms.

Clothing and other materials such as bedding that will have direct skin contact should be washed to remove hastisetae and be stored in airtight containers in addition to items made with animal fibers, such as wool sweaters and down blankets. Mattresses, flooring, rugs, curtains, and other amenable areas should be vacuumed thoroughly, and the vacuum bag should be placed in the trash afterward. Protective pillow and mattress covers should be used. Stuffed animals in infested areas should be thrown away if not able to be completely washed and dried. Air conditioning systems may spread larval hairs away from the site of infestation and should be cleaned as much as possible. Surfaces where beetles and larvae also are commonly seen, such as windowsills, and hidden among closet and pantry items should also be wiped clean to remove both insects and potential substrate. In one case, scraping the wood flooring and applying a thick coat of varnish in addition to removing all stuffed animals from an affected individual’s home allowed for resolution of symptoms.17

Treatment for symptoms includes topical anti-inflammatory agents and/or oral antihistamines, with improvement in symptoms typically occurring within days and resolution dependent on level of exposure moving forward.

Final Thoughts

- Gumina ME, Yan AC. Carpet beetle dermatitis mimicking bullous impetigo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:329-331. doi:10.1111/pde.14453

- Bertone MA, Leong M, Bayless KM, et al. Arthropods of the great indoors: characterizing diversity inside urban and suburban homes. PeerJ. 2016;4:E1582. doi:10.7717/peerj.1582

- Siegel S, Lee N, Rohr A, et. al. Evaluation of dermestid sensitivity in museum personnel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87:190. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(91)91488-F

- Brito FF, Mur P, Barber D, et al. Occupational rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma in a wool worker caused by Dermestidae spp. Allergy. 2002;57:1191-1194.

- Stengaard HL, Akerlund M, Grontoft T, et al. Future pest status of an insect pest in museums, Attagenus smirnovi: distribution and food consumption in relation to climate change. J Cult Herit. 2012;13:22l-227.

- Veer V, Negi BK, Rao KM. Dermestid beetles and some other insect pests associated with stored silkworm cocoons in India, including a world list of dermestid species found attacking this commodity. J Stored Products Research. 1996;32:69-89.

- Veer V, Prasad R, Rao KM. Taxonomic and biological notes on Attagenus and Anthrenus spp. (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) found damaging stored woolen fabrics in India. J Stored Products Research. 1991;27:189-198.

- Háva J. World Catalogue of Insects. Volume 13. Dermestidae (Coleoptera). Brill; 2015.

- Ruzzier E, Kadej M, Di Giulio A, et al. Entangling the enemy: ecological, systematic, and medical implications of dermestid beetle Hastisetae. Insects. 2021;12:436. doi:10.3390/insects12050436

- Arae K, Morita H, Unno H, et al. Chitin promotes antigen-specific Th2 cell-mediated murine asthma through induction of IL-33-mediated IL-1β production by DCs. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11721.

- Brinchmann BC, Bayat M, Brøgger T, et. al. A possible role of chitin in the pathogenesis of asthma and allergy. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2011;18:7-12.

- Bucolo C, Musumeci M, Musumeci S, et al. Acidic mammalian chitinase and the eye: implications for ocular inflammatory diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2011;2:1-4.

- Hoverson K, Wohltmann WE, Pollack RJ, et al. Dermestid dermatitis in a 2-year-old girl: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:E228-E233. doi:10.1111/pde.12641

- Simon L, Boukari F, Oumarou H, et al. Anthrenus sp. and an uncommon cluster of dermatitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1940-1943. doi:10.3201/eid2707.203245

- Ahmed R, Moy R, Barr R, et al. Carpet beetle dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:428-432.

- MacArthur K, Richardson V, Novoa R, et al. Carpet beetle dermatitis: a possibly under-recognized entity. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:577-579.

- Cuesta-Herranz J, de las Heras M, Sastre J, et al. Asthma caused by Dermestidae (black carpet beetle): a new allergen in house dust. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(1 Pt 1):147-149.

- Bernstein J, Morgan M, Ghosh D, et al. Respiratory sensitization of a worker to the warehouse beetle Trogoderma variabile: an index case report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1413-1416.

- Gorgojo IE, De Las Heras M, Pastor C, et al. Allergy to Dermestidae: a new indoor allergen? [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:AB105.

- Ruzzier E, Kadej M, Battisti A. Occurrence, ecological function and medical importance of dermestid beetle hastisetae. PeerJ. 2020;8:E8340. doi:10.7717/peerj.8340

- Ramachandran J, Hern J, Almeyda J, et al. Contact dermatitis with cervical lymphadenopathy following exposure to the hide beetle, Dermestes peruvianus. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:943-945.

- Horster S, Prinz J, Holm N, et al. Anthrenus-dermatitis. Hautarzt. 2002;53:328-331.

- Justiz Vaillant AA, Vashisht R, Zito PM. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

Carpet beetle larvae of the family Dermestidae have been documented to cause both acute and delayed hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals. These larvae have specialized horizontal rows of spear-shaped hairs called hastisetae, which detach easily into the surrounding environment and are small enough to travel by air. Exposure to hastisetae has been tied to adverse effects ranging from dermatitis to rhinoconjunctivitis and acute asthma, with treatment being mostly empiric and symptom based. Due to the pervasiveness of carpet beetles in homes, improved awareness of dermestid-induced manifestations is valuable for clinicians.

Beetles in the Dermestidae family do not bite humans but have been reported to cause skin reactions in addition to other symptoms typical of an allergic reaction. Skin contact with larval hairs (hastisetae) of these insects—known as carpet, larder, or hide beetles — may cause urticarial or edematous papules that are mistaken for papular urticaria or arthropod bites. 1 There are approximately 500 to 700 species of carpet beetles worldwide. Carpet beetles are a clinically underrecognized cause of allergic contact dermatitis given their frequent presence in homes across the world. 2 Carpet beetle larvae feed on shed skin, feathers, hair, wool, book bindings, felt, leather, wood, silk, and sometimes grains and thus can be found nearly anywhere. Most symptom-inducing exposures to Dermestidae beetles occur occupationally, such as in museum curators working hands-on with collection materials and workers handling infested materials such as wool. 3,4 In-home Dermestidae exposure may lead to symptoms, especially if regularly worn clothing and bedding materials are infested. The broad palate of dermestid members has resulted in substantial contamination of stored materials such as flour and fabric in addition to the destruction of museum collections. 5-7

The larvae of some dermestid species, most commonly of the genera Anthrenus and Dermestes, are 2 to 3 mm in length and have detachable hairlike hastisetae that shed into the surrounding environment throughout larval development (Figure 1).8 The hastisetae, located on the thoracic and abdominal segments (tergites), serve as a larval defense mechanism. When prodded, the round, hairy, wormlike larvae tense up and can raise their abdominal tergites while splaying the hastisetae out in a fanlike manner.9 Similar to porcupine quills, the hastisetae easily detach and can entrap the appendages of invertebrate predators. Hastisetae are not known to be sharp enough to puncture human skin, but friction and irritation from skin contact and superficial sticking of the hastisetae into mucous membranes and noncornified epithelium, such as in the bronchial airways, are thought to induce hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals.

Additionally, hastisetae and the exoskeletons of both adult and larval dermestid beetles are composed mostly of chitin, which is highly allergenic. Chitin has been found to play a proinflammatory role in ocular inflammation, asthma, and bronchial reactivity via T helper cell (TH2)–mediated cellular interactions.10-12 Larvae shed their exoskeletons, including hastisetae, multiple times over the course of their development, which contributes to their potential allergen burden (Figure 2). Reports of positive prick and/or patch testing to larval components indicate some cases of both acute type 1 and delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions.4,8,13

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Multiple erythematous urticarial papules, papulopustules, and papulovesicles are the typical manifestations of dermestid dermatitis.3,4,13-16 Figure 3 demonstrates several characteristic edematous papules with background erythema. Unlike the clusters seen with flea and bed bug bites, dermestid-induced lesions typically are single and scattered, with a propensity for exposed limbs and the face. Exposure to hastisetae commonly results in classic allergic symptoms including rhinitis, conjunctivitis, coughing, wheezing, sneezing, and intranasal and periocular pruritus, even in those with no personal history of atopy.17-19 Lymphadenopathy, vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis also have been reported.20 A large infestation in which many individual beetles as well as larvae can be found in 1 or more areas of the inhabited structure has been reported to cause more severe symptoms, including acute eczema, otitis externa, lymphocytic vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis, all of which resolved within 3 months of thorough deinfestation cleaning.21

Skin-prick and/or patch testing is not necessary for this clinical diagnosis of dermestid-induced allergic contact dermatitis. This diagnosis is bolstered by (but does not require a history of) repeated symptom induction upon performing certain activities (eg, handling taxidermy specimens) and/or in certain environments (eg, only at home). Because of individual differences in hypersensitivity to dermestid parts, it is not typical for all members of a household to be affected.

When there are multiple potential suspected allergens or an unknown cause for symptoms despite a detailed history, allergy testing can be useful in confirming a diagnosis and directing management. Immediate-onset type 1 hypersensitivity reactions are evaluated using skin-prick testing or serum IgE levels, whereas delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions can be evaluated using patch testing. Type 1 reactions tend to present with classic allergy symptoms, especially where there are abundant mast cells to degranulate in the skin and mucosa of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts; these symptoms range from mild wheezing, urticaria, periorbital pruritus, and sneezing to outright asthma, diarrhea, rhinoconjunctivitis, and even anaphylaxis. With these reactions, initial exposure to an antigen such as chitin in the hastisetae leads to an asymptomatic sensitization against the antigen in which its introduction leads to a TH2-skewed cellular response, which promotes B-cell production of IgE antibodies. Upon subsequent exposure to this antigen, IgE antibodies bound to mast cells will lead them to degranulate with release of histamine and other proinflammatory molecules, resulting in clinical manifestations. The skin-prick test relies on introduction of potential antigens through the epidermis into the dermis with a sharp lancet to induce IgE antibody activation and then degranulation of the patient’s mast cells, resulting in a pruritic erythematous wheal. This IgE-mediated process has been shown to occur in response to dermestid larval parts among household dust, resulting in chronic coughing, sneezing, nasal pruritus, and asthma.15,17,22

Type 4 hypersensitivity reactions are T-cell mediated and also include a sensitization phase followed by symptom manifestation upon repeat exposure; however, these reactions usually are not immediate and can take up to 72 hours after exposure to manifest.23 This is because T cells specific to the antigen do not lead a process resulting in antibodies but instead recruit numerous other TH1-polarized mediators upon re-exposure to activate cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and macrophages to attempt to neutralize the antigen. Many type 4 reactions result in mostly cutaneous manifestations, such as contact dermatitis. Patch testing involves adhering potential allergens to the skin for a time with assessments at regular intervals to evaluate the level of reaction from weakly positive to severe. At minimum, most reports of dermestid-related manifestations include a rash such as erythematous papules, and several published cases involving patch testing have yielded positive results to various preparations of larval parts.3,14,21

Management and Treatment

Prevention of dermestid exposure is difficult given the myriad materials eaten by the larvae. An insect exterminator should verify and treat a carpet beetle infestation, while a dermatologist can treat symptomatic individuals. Treatment is driven by the severity of the patient’s discomfort and is aimed at both symptomatic relief and reducing dermestid exposure moving forward. Although in certain environments it will be nearly impossible to eradicate Dermestidae, cleaning thoroughly and regularly may go far to reduce exposure and associated symptoms.

Clothing and other materials such as bedding that will have direct skin contact should be washed to remove hastisetae and be stored in airtight containers in addition to items made with animal fibers, such as wool sweaters and down blankets. Mattresses, flooring, rugs, curtains, and other amenable areas should be vacuumed thoroughly, and the vacuum bag should be placed in the trash afterward. Protective pillow and mattress covers should be used. Stuffed animals in infested areas should be thrown away if not able to be completely washed and dried. Air conditioning systems may spread larval hairs away from the site of infestation and should be cleaned as much as possible. Surfaces where beetles and larvae also are commonly seen, such as windowsills, and hidden among closet and pantry items should also be wiped clean to remove both insects and potential substrate. In one case, scraping the wood flooring and applying a thick coat of varnish in addition to removing all stuffed animals from an affected individual’s home allowed for resolution of symptoms.17

Treatment for symptoms includes topical anti-inflammatory agents and/or oral antihistamines, with improvement in symptoms typically occurring within days and resolution dependent on level of exposure moving forward.

Final Thoughts

Carpet beetle larvae of the family Dermestidae have been documented to cause both acute and delayed hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals. These larvae have specialized horizontal rows of spear-shaped hairs called hastisetae, which detach easily into the surrounding environment and are small enough to travel by air. Exposure to hastisetae has been tied to adverse effects ranging from dermatitis to rhinoconjunctivitis and acute asthma, with treatment being mostly empiric and symptom based. Due to the pervasiveness of carpet beetles in homes, improved awareness of dermestid-induced manifestations is valuable for clinicians.

Beetles in the Dermestidae family do not bite humans but have been reported to cause skin reactions in addition to other symptoms typical of an allergic reaction. Skin contact with larval hairs (hastisetae) of these insects—known as carpet, larder, or hide beetles — may cause urticarial or edematous papules that are mistaken for papular urticaria or arthropod bites. 1 There are approximately 500 to 700 species of carpet beetles worldwide. Carpet beetles are a clinically underrecognized cause of allergic contact dermatitis given their frequent presence in homes across the world. 2 Carpet beetle larvae feed on shed skin, feathers, hair, wool, book bindings, felt, leather, wood, silk, and sometimes grains and thus can be found nearly anywhere. Most symptom-inducing exposures to Dermestidae beetles occur occupationally, such as in museum curators working hands-on with collection materials and workers handling infested materials such as wool. 3,4 In-home Dermestidae exposure may lead to symptoms, especially if regularly worn clothing and bedding materials are infested. The broad palate of dermestid members has resulted in substantial contamination of stored materials such as flour and fabric in addition to the destruction of museum collections. 5-7

The larvae of some dermestid species, most commonly of the genera Anthrenus and Dermestes, are 2 to 3 mm in length and have detachable hairlike hastisetae that shed into the surrounding environment throughout larval development (Figure 1).8 The hastisetae, located on the thoracic and abdominal segments (tergites), serve as a larval defense mechanism. When prodded, the round, hairy, wormlike larvae tense up and can raise their abdominal tergites while splaying the hastisetae out in a fanlike manner.9 Similar to porcupine quills, the hastisetae easily detach and can entrap the appendages of invertebrate predators. Hastisetae are not known to be sharp enough to puncture human skin, but friction and irritation from skin contact and superficial sticking of the hastisetae into mucous membranes and noncornified epithelium, such as in the bronchial airways, are thought to induce hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals.

Additionally, hastisetae and the exoskeletons of both adult and larval dermestid beetles are composed mostly of chitin, which is highly allergenic. Chitin has been found to play a proinflammatory role in ocular inflammation, asthma, and bronchial reactivity via T helper cell (TH2)–mediated cellular interactions.10-12 Larvae shed their exoskeletons, including hastisetae, multiple times over the course of their development, which contributes to their potential allergen burden (Figure 2). Reports of positive prick and/or patch testing to larval components indicate some cases of both acute type 1 and delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions.4,8,13

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Multiple erythematous urticarial papules, papulopustules, and papulovesicles are the typical manifestations of dermestid dermatitis.3,4,13-16 Figure 3 demonstrates several characteristic edematous papules with background erythema. Unlike the clusters seen with flea and bed bug bites, dermestid-induced lesions typically are single and scattered, with a propensity for exposed limbs and the face. Exposure to hastisetae commonly results in classic allergic symptoms including rhinitis, conjunctivitis, coughing, wheezing, sneezing, and intranasal and periocular pruritus, even in those with no personal history of atopy.17-19 Lymphadenopathy, vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis also have been reported.20 A large infestation in which many individual beetles as well as larvae can be found in 1 or more areas of the inhabited structure has been reported to cause more severe symptoms, including acute eczema, otitis externa, lymphocytic vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis, all of which resolved within 3 months of thorough deinfestation cleaning.21

Skin-prick and/or patch testing is not necessary for this clinical diagnosis of dermestid-induced allergic contact dermatitis. This diagnosis is bolstered by (but does not require a history of) repeated symptom induction upon performing certain activities (eg, handling taxidermy specimens) and/or in certain environments (eg, only at home). Because of individual differences in hypersensitivity to dermestid parts, it is not typical for all members of a household to be affected.

When there are multiple potential suspected allergens or an unknown cause for symptoms despite a detailed history, allergy testing can be useful in confirming a diagnosis and directing management. Immediate-onset type 1 hypersensitivity reactions are evaluated using skin-prick testing or serum IgE levels, whereas delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions can be evaluated using patch testing. Type 1 reactions tend to present with classic allergy symptoms, especially where there are abundant mast cells to degranulate in the skin and mucosa of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts; these symptoms range from mild wheezing, urticaria, periorbital pruritus, and sneezing to outright asthma, diarrhea, rhinoconjunctivitis, and even anaphylaxis. With these reactions, initial exposure to an antigen such as chitin in the hastisetae leads to an asymptomatic sensitization against the antigen in which its introduction leads to a TH2-skewed cellular response, which promotes B-cell production of IgE antibodies. Upon subsequent exposure to this antigen, IgE antibodies bound to mast cells will lead them to degranulate with release of histamine and other proinflammatory molecules, resulting in clinical manifestations. The skin-prick test relies on introduction of potential antigens through the epidermis into the dermis with a sharp lancet to induce IgE antibody activation and then degranulation of the patient’s mast cells, resulting in a pruritic erythematous wheal. This IgE-mediated process has been shown to occur in response to dermestid larval parts among household dust, resulting in chronic coughing, sneezing, nasal pruritus, and asthma.15,17,22

Type 4 hypersensitivity reactions are T-cell mediated and also include a sensitization phase followed by symptom manifestation upon repeat exposure; however, these reactions usually are not immediate and can take up to 72 hours after exposure to manifest.23 This is because T cells specific to the antigen do not lead a process resulting in antibodies but instead recruit numerous other TH1-polarized mediators upon re-exposure to activate cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and macrophages to attempt to neutralize the antigen. Many type 4 reactions result in mostly cutaneous manifestations, such as contact dermatitis. Patch testing involves adhering potential allergens to the skin for a time with assessments at regular intervals to evaluate the level of reaction from weakly positive to severe. At minimum, most reports of dermestid-related manifestations include a rash such as erythematous papules, and several published cases involving patch testing have yielded positive results to various preparations of larval parts.3,14,21

Management and Treatment

Prevention of dermestid exposure is difficult given the myriad materials eaten by the larvae. An insect exterminator should verify and treat a carpet beetle infestation, while a dermatologist can treat symptomatic individuals. Treatment is driven by the severity of the patient’s discomfort and is aimed at both symptomatic relief and reducing dermestid exposure moving forward. Although in certain environments it will be nearly impossible to eradicate Dermestidae, cleaning thoroughly and regularly may go far to reduce exposure and associated symptoms.

Clothing and other materials such as bedding that will have direct skin contact should be washed to remove hastisetae and be stored in airtight containers in addition to items made with animal fibers, such as wool sweaters and down blankets. Mattresses, flooring, rugs, curtains, and other amenable areas should be vacuumed thoroughly, and the vacuum bag should be placed in the trash afterward. Protective pillow and mattress covers should be used. Stuffed animals in infested areas should be thrown away if not able to be completely washed and dried. Air conditioning systems may spread larval hairs away from the site of infestation and should be cleaned as much as possible. Surfaces where beetles and larvae also are commonly seen, such as windowsills, and hidden among closet and pantry items should also be wiped clean to remove both insects and potential substrate. In one case, scraping the wood flooring and applying a thick coat of varnish in addition to removing all stuffed animals from an affected individual’s home allowed for resolution of symptoms.17

Treatment for symptoms includes topical anti-inflammatory agents and/or oral antihistamines, with improvement in symptoms typically occurring within days and resolution dependent on level of exposure moving forward.

Final Thoughts

- Gumina ME, Yan AC. Carpet beetle dermatitis mimicking bullous impetigo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:329-331. doi:10.1111/pde.14453

- Bertone MA, Leong M, Bayless KM, et al. Arthropods of the great indoors: characterizing diversity inside urban and suburban homes. PeerJ. 2016;4:E1582. doi:10.7717/peerj.1582

- Siegel S, Lee N, Rohr A, et. al. Evaluation of dermestid sensitivity in museum personnel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87:190. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(91)91488-F

- Brito FF, Mur P, Barber D, et al. Occupational rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma in a wool worker caused by Dermestidae spp. Allergy. 2002;57:1191-1194.

- Stengaard HL, Akerlund M, Grontoft T, et al. Future pest status of an insect pest in museums, Attagenus smirnovi: distribution and food consumption in relation to climate change. J Cult Herit. 2012;13:22l-227.

- Veer V, Negi BK, Rao KM. Dermestid beetles and some other insect pests associated with stored silkworm cocoons in India, including a world list of dermestid species found attacking this commodity. J Stored Products Research. 1996;32:69-89.

- Veer V, Prasad R, Rao KM. Taxonomic and biological notes on Attagenus and Anthrenus spp. (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) found damaging stored woolen fabrics in India. J Stored Products Research. 1991;27:189-198.

- Háva J. World Catalogue of Insects. Volume 13. Dermestidae (Coleoptera). Brill; 2015.

- Ruzzier E, Kadej M, Di Giulio A, et al. Entangling the enemy: ecological, systematic, and medical implications of dermestid beetle Hastisetae. Insects. 2021;12:436. doi:10.3390/insects12050436

- Arae K, Morita H, Unno H, et al. Chitin promotes antigen-specific Th2 cell-mediated murine asthma through induction of IL-33-mediated IL-1β production by DCs. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11721.

- Brinchmann BC, Bayat M, Brøgger T, et. al. A possible role of chitin in the pathogenesis of asthma and allergy. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2011;18:7-12.

- Bucolo C, Musumeci M, Musumeci S, et al. Acidic mammalian chitinase and the eye: implications for ocular inflammatory diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2011;2:1-4.

- Hoverson K, Wohltmann WE, Pollack RJ, et al. Dermestid dermatitis in a 2-year-old girl: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:E228-E233. doi:10.1111/pde.12641

- Simon L, Boukari F, Oumarou H, et al. Anthrenus sp. and an uncommon cluster of dermatitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1940-1943. doi:10.3201/eid2707.203245

- Ahmed R, Moy R, Barr R, et al. Carpet beetle dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:428-432.

- MacArthur K, Richardson V, Novoa R, et al. Carpet beetle dermatitis: a possibly under-recognized entity. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:577-579.

- Cuesta-Herranz J, de las Heras M, Sastre J, et al. Asthma caused by Dermestidae (black carpet beetle): a new allergen in house dust. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(1 Pt 1):147-149.

- Bernstein J, Morgan M, Ghosh D, et al. Respiratory sensitization of a worker to the warehouse beetle Trogoderma variabile: an index case report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1413-1416.

- Gorgojo IE, De Las Heras M, Pastor C, et al. Allergy to Dermestidae: a new indoor allergen? [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:AB105.

- Ruzzier E, Kadej M, Battisti A. Occurrence, ecological function and medical importance of dermestid beetle hastisetae. PeerJ. 2020;8:E8340. doi:10.7717/peerj.8340

- Ramachandran J, Hern J, Almeyda J, et al. Contact dermatitis with cervical lymphadenopathy following exposure to the hide beetle, Dermestes peruvianus. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:943-945.

- Horster S, Prinz J, Holm N, et al. Anthrenus-dermatitis. Hautarzt. 2002;53:328-331.

- Justiz Vaillant AA, Vashisht R, Zito PM. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Gumina ME, Yan AC. Carpet beetle dermatitis mimicking bullous impetigo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:329-331. doi:10.1111/pde.14453

- Bertone MA, Leong M, Bayless KM, et al. Arthropods of the great indoors: characterizing diversity inside urban and suburban homes. PeerJ. 2016;4:E1582. doi:10.7717/peerj.1582

- Siegel S, Lee N, Rohr A, et. al. Evaluation of dermestid sensitivity in museum personnel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87:190. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(91)91488-F

- Brito FF, Mur P, Barber D, et al. Occupational rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma in a wool worker caused by Dermestidae spp. Allergy. 2002;57:1191-1194.

- Stengaard HL, Akerlund M, Grontoft T, et al. Future pest status of an insect pest in museums, Attagenus smirnovi: distribution and food consumption in relation to climate change. J Cult Herit. 2012;13:22l-227.

- Veer V, Negi BK, Rao KM. Dermestid beetles and some other insect pests associated with stored silkworm cocoons in India, including a world list of dermestid species found attacking this commodity. J Stored Products Research. 1996;32:69-89.

- Veer V, Prasad R, Rao KM. Taxonomic and biological notes on Attagenus and Anthrenus spp. (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) found damaging stored woolen fabrics in India. J Stored Products Research. 1991;27:189-198.

- Háva J. World Catalogue of Insects. Volume 13. Dermestidae (Coleoptera). Brill; 2015.

- Ruzzier E, Kadej M, Di Giulio A, et al. Entangling the enemy: ecological, systematic, and medical implications of dermestid beetle Hastisetae. Insects. 2021;12:436. doi:10.3390/insects12050436

- Arae K, Morita H, Unno H, et al. Chitin promotes antigen-specific Th2 cell-mediated murine asthma through induction of IL-33-mediated IL-1β production by DCs. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11721.

- Brinchmann BC, Bayat M, Brøgger T, et. al. A possible role of chitin in the pathogenesis of asthma and allergy. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2011;18:7-12.

- Bucolo C, Musumeci M, Musumeci S, et al. Acidic mammalian chitinase and the eye: implications for ocular inflammatory diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2011;2:1-4.

- Hoverson K, Wohltmann WE, Pollack RJ, et al. Dermestid dermatitis in a 2-year-old girl: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:E228-E233. doi:10.1111/pde.12641

- Simon L, Boukari F, Oumarou H, et al. Anthrenus sp. and an uncommon cluster of dermatitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1940-1943. doi:10.3201/eid2707.203245

- Ahmed R, Moy R, Barr R, et al. Carpet beetle dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:428-432.

- MacArthur K, Richardson V, Novoa R, et al. Carpet beetle dermatitis: a possibly under-recognized entity. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:577-579.

- Cuesta-Herranz J, de las Heras M, Sastre J, et al. Asthma caused by Dermestidae (black carpet beetle): a new allergen in house dust. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(1 Pt 1):147-149.

- Bernstein J, Morgan M, Ghosh D, et al. Respiratory sensitization of a worker to the warehouse beetle Trogoderma variabile: an index case report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1413-1416.

- Gorgojo IE, De Las Heras M, Pastor C, et al. Allergy to Dermestidae: a new indoor allergen? [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:AB105.

- Ruzzier E, Kadej M, Battisti A. Occurrence, ecological function and medical importance of dermestid beetle hastisetae. PeerJ. 2020;8:E8340. doi:10.7717/peerj.8340

- Ramachandran J, Hern J, Almeyda J, et al. Contact dermatitis with cervical lymphadenopathy following exposure to the hide beetle, Dermestes peruvianus. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:943-945.

- Horster S, Prinz J, Holm N, et al. Anthrenus-dermatitis. Hautarzt. 2002;53:328-331.

- Justiz Vaillant AA, Vashisht R, Zito PM. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

Practice Points

- Given their ubiquity, dermatologists should be aware of the potential for hypersensitivity reactions to carpet beetles (Dermestidae).

- Pruritic erythematous papules, pustules, and vesicles are the most common manifestations of exposure to larval hairs.

- Treatment is symptom based, and future exposure can be greatly diminished with thorough cleaning of the patient’s environment.

What’s Eating You? Noble False Widow Spider (Steatoda nobilis)

Incidence and Characteristics

The noble false widow spider (Steatoda nobilis) is one of the world’s most invasive spider species, having spread across the globe from Madeira and the Canary Islands into the North Atlantic.1,2 Steatoda comprise multiple species of false widow spiders, named for their resemblance to black widow spiders (Latrodectus). The noble false widow spider is the dominant species in buildings in southern Ireland and Great Britain, with a population surge in 2018 that caused multiple temporary school closures in London, England, for fumigation.3 The noble false widow spider was first documented in the United States in Ventura County, California, in 2011, with numerous specimens found in urban areas (eg, in parks, underneath garbage cans) closer to the coastline as well as farther inland. The species may have been introduced to this area by way of Port Hueneme, a city in California with a US naval base with routes to various other military bases in Western Europe.4 Given its already rapid expansion outside of the United States with a concurrent rise in bite reports, dermatologists should be familiar with these invasive and potentially dangerous arachnids.

The spread of noble false widow spiders is assisted by their wide range of temperature tolerance and ability to survive for months with little food and no water. They can live for several years, with one report of a noble false widow spider living up to 7 years.5 These spiders are found inside homes and buildings year-round, and they prefer to build their webs in an elevated position such as the top corner of a room. Steatoda weave tangle webs with crisscrossing threads that often have a denser middle section.5

Noble false widow spiders are sexually dimorphic, with males typically no larger than 1-cm long and females up to 1.4-cm long. They have a dark brown to black thorax and brown abdomen with red-brown legs. Males have brighter cream-colored abdominal markings than females, who lack markings altogether on their distinctive globular abdomen (Figure). The abdominal markings are known to resemble a skull or house.

Although noble false widow spiders are not exclusively synanthropic, they can be found in any crevice in homes or other structures where there are humans such as office buildings.5-7 Up until the last 20 years, reports of bites from noble false widow spiders worldwide were few and far between. In Great Britain, the spiders were first considered to be common in the 1980s, with recent evidence of an urban population boom in the last 5 to 10 years that has coincided with an increase in bite reports.5,8,9

Clinical Significance

Most bites occur in a defensive manner, such as when humans perform activities that disturb the hiding space, cause vibrations in the web, or compress the body of the arachnid. Most envenomations in Great Britain occur while the individual is in bed, though they also may occur during other activities that disturb the spider, such as moving boxes or putting on a pair of pants.5 Occupational exposure to noble false widow spiders may soon be a concern for those involved in construction, carpentry, cleaning, and decorating given their recent invasive spread into the United States.

The venom from these spiders is neurotoxic and cytotoxic, causing moderate to intense pain that may resemble a wasp sting. The incidence of steatodism—which can include symptoms of pain in addition to fever, hypotension, headache, lethargy, nausea, localized diaphoresis, abdominal pain, paresthesias, and malaise—is unknown but reportedly rare.5,10 There are considerable similarities between Steatoda and true black widow spider venom, which explains the symptom overlap with latrodectism. There are reports of severe debilitation lasting weeks due to pain and decreased affected limb movement after bites from noble false widow spiders.10-12

Nearly all noble false widow spider bite reports describe immediate pain upon bite/envenomation, which is unlike the delayed pain from a black widow spider bite (after 10 minutes or more).6,13,14 Erythema and swelling occur around a pale raised site of envenomation lasting up to 72 hours. The bite site may be highly tender and blister or ulcerate, with reports of cellulitis and local skin necrosis.7,15 Pruritus during this period can be intense, and excoriation increases the risk for complications such as infection. Reports of anaphylaxis following a noble false widow spider bite are rare.5,16 The incidence of bites may be underreported due to the lack of proper identification of the responsible arachnid for those who do not seek care or require hospitalization, though this is not unique to Steatoda.

There are reports of secondary infection after bites and even cases of limb amputation, septicemia, and death.14,17 However, it is unknown if noble false widow spiders are vectors for bacteria transmitted during envenomation, and infection likely is secondary to scratching or inadequate wound care.18,19 Potentially pathogenic bacteria have been isolated from the body surfaces of the noble false widow spider, including Pseudomonas putida, Staphylococcus capitis, and Staphylococcus epidermidis.20 Fortunately, most captured cases (ie, events in which the biting arachnid was properly identified) report symptoms ranging from mild to moderate in severity without the need for hospitalization. A series of 24 reports revealed that all individuals experienced sharp pain upon the initial bite followed by erythema, and 18 of them experienced considerable swelling of the area soon thereafter. One individual experienced temporary paralysis of the affected limb, and 3 individuals experienced hypotension or hypertension in addition to fever, skin necrosis, or cellulitis.14

Treatment

The envenomation site should be washed with antibacterial soap and warm water and should be kept clean to prevent infection. There is no evidence that tight pressure bandaging of these bite sites will restrict venom flow; because it may worsen pain in the area, pressure bandaging is not recommended. When possible, the arachnid should be collected for identification. Supportive care is warranted for symptoms of pain, erythema, and swelling, with the use of cool compresses, oral pain relievers (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen), topical anesthetic (eg, lidocaine), or antihistamines as needed.

Urgent care is warranted for patients who experience severe symptoms of steatodism such as hypertension, lymphadenopathy, paresthesia, or limb paralysis. Limited reports show onset of this distress typically within an hour of envenomation. Treatments analogous to those for latrodectism including muscle relaxers and pain medications have demonstrated rapid attenuation of symptoms upon intramuscular administration of antivenom made from Latrodectus species.21-23

Signs of infection warrant bacterial culture with antibiotic susceptibilities to ensure adequate treatment.20 Infections from spider bites can present a few days to a week following envenomation. Symptoms may include spreading redness or an enlarging wound site, pus formation, worsening or unrelenting pain after 24 hours, fevers, flulike symptoms, and muscle cramps.

Final Thoughts

- Kulczycki A, Legittimo C, Simeon E, et al. New records of Steatoda nobilis (Thorell, 1875) (Araneae, Theridiidae), an introduced species on the Italian mainland and in Sardinia. Bull Br Arachnological Soc. 2012;15:269-272.

- Bauer T, Feldmeier S, Krehenwinkel H, et al. Steatoda nobilis, a false widow on the rise: a synthesis of past and current distribution trends. NeoBiota. 2019; 42:19. doi:10.3897/neobiota.42.31582

- Murphy A. Web of cries: false widow spider infestation fears forceeleventh school in London to close as outbreak spreads. The Sun.October 19, 2018. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/7534016/false-widow-spider-infestation-fears-force-eleventh-londonschool-closing

- Vetter R, Rust M. A large European combfoot spider, Steatoda nobilis (Thorell 1875)(Araneae: Theridiidae), newly established in Ventura County, California. The Pan-Pacific Entomologist. 2012;88:92-97.

- Hambler C. The ‘noble false widow’ spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threat. OSF Preprints. Preprint posted online October 15, 2019. doi:10.31219/osf.io/axbd4

- Dunbar J, Schulte J, Lyons K, et al. New Irish record for Steatoda triangulosa (Walckenaer, 1802), and new county records for Steatoda nobilis (Thorell, 1875), Steatoda bipunctata (Linnaeus, 1758) and Steatoda grossa (C.L. Koch, 1838). Ir Naturalists J. 2018;36:39-43.

- Duon M, Dunbar J, Afoullouss S, et al. Occurrence, reproductive rate and identification of the non-native noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis (Thorell, 1875) in Ireland. Biol Environment: Proc Royal Ir Acad. 2017;117B:77-89. doi:10.3318/bioe.2017.11

- Burrows T. Great bitten: Britain’s spider bite capital revealed as Essex with 450 attacks—find out where your town ranks. The Sun. Published April 3, 2019. Accessed September 14, 2023. https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/8782355/britains-spider-bite-capital-revealed-as-essex-with-450- attacks-find-out-where-your-town-ranks/

- Wathen T. Essex is the UK capital for spider bites—and the amount is terrifying. Essex News. April 4, 2019. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.essexlive.news/news/essex-news/essex-uk-capital-spider-bites- 2720935

- Dunbar J, Afoullouss S, Sulpice R, et al. Envenomation by the noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis (Thorell, 1875)—five new cases of steatodism from Ireland and Great Britain. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56:433-435. doi:10.1080/15563650.2017.1393084

- Dunbar J, Fort A, Redureau D, et al. Venomics approach reveals a high proportion of Latrodectus-like toxins in the venom of the noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis. Toxins. 2020;12:402.

- Warrell D, Shaheen J, Hillyard P, et al. Neurotoxic envenoming by an immigrant spider (Steatoda nobilis) in southern England. Toxicon. 1991;29:1263-1265.

- Zhou H, Xu K, Zheng PY, et. al. Clinical characteristics of patients with black widow spider bites: a report of 59 patients and single-center experience. World J Emerg Med. 2021;12:317-320. doi:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2021.04.011

- Dunbar J, Vitkauskaite A, O’Keeffe D, et. al. Bites by the noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis can induce Latrodectus-like symptoms and vector-borne bacterial infections with implications for public health: a case series. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2022;60:59-70. doi:10.1080/15563650.2021.1928165

- Dunbar J, Sulpice R, Dugon M. The kiss of (cell) death: can venom-induced immune response contribute to dermal necrosis following arthropod envenomations? Clin Toxicol. 2019;57:677-685. doi:10.1080/15563650.2019.1578367

- Magee J. Bite ‘nightmare’: close encounter with a false widow. The Bournemouth Echo. September 7, 2009. Accessed September 21, 2023. http://www.bournemouthecho.co.uk/news/4582887.Bite____nightmare_____close_encounter_with_a_false_widow_spider/

- Marsh H. Woman nearly loses hand after bite from false widow. Daily Echo. April 17, 2012. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.bournemouthecho.co.uk/news/9652335.woman-nearly-loses-hand-after-bite-from-false-widow-spider/

- Stuber N, Nentwig W. How informative are case studies of spider bites in the medical literature? Toxicon. 2016;114:40-44. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.02.023