User login

Should Pediatric HM Pursue Subspecialty Certification, Required Fellowship Training?

PRO

A powerful tool, subspecialty certification should be adopted—and soon

There are many different ways for pediatric hospital medicine to evolve and gain recognition. Board certification with required fellowship training is the most well-known method. For adult hospitalists, recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) has been established. Residency programs are becoming more innovative, creating additional tracks to provide accelerated fellowship education. What path should be chosen for the future of pediatric hospital medicine?

The decision could be compared to purchasing a cellphone. Simple flip phones are sufficient for making phone calls, just as a graduating pediatrics resident might care for routine inpatients. But the smartphone, like the fellowship/subspecialty certification route, provides advantages that could be worth the additional costs.

You can tell a lot about a person by looking at their cellphone. It often reveals personality traits, professions, and behavioral tendencies. Similarly, administrators, colleagues, and other payors might make assumptions based on fellowship/subspecialty certification status. Pediatric hospitalists should be considered experts in the field of clinical HM, hospital-based research, quality improvement (QI), inpatient procedures, and administrative leadership. Fellowship directors have begun discussing how to standardize these content areas. Subspecialty certification after such training will provide a powerful tool for hospitalists to navigate potentially complex clinical scenarios, hospital bureaucracies and/or academic hierarchies. Fellowship training will add a more concrete identity and standards of quality to our subspecialty.

Smartphones are “smart” because they bring convenience and efficiency. The same can be said about fellowship training. Residency training no longer addresses all the needs of a practicing hospitalist. Although one can attend workshops on QI or research and learn hospital administration, all while on the job, many young hospitalists struggle to adapt quickly early in their career; they might fail to thrive. Fellowship programs would provide a learner-centered environment and protected time to accomplish these goals. Certification would help ensure that trainees have the knowledge and competencies needed for the job. This process, designed to create a well-prepared hospitalist work force, should lead to better advancement within the field, which would mean more hospitalists in meaningful leadership roles and improved quality of hospital care.

The cost of a cellphone and its monthly plan must be taken into account when choosing what purchase. Similarly, the benefits of additional education and recognition must be measured against the costs of additional training. For most, the benefits of well-trained hospitalists outweigh the costs in the long run. Concerns of alienating those without board certification or limiting the work force likely are unfounded. The majority of EDs are staffed by general emergency medicine physicians who do not have pediatric emergency medicine certification—and they all see children, and provide referrals to dedicated children’s facilities when needed. Similarly, community hospital wards can choose to follow suit, depending on their needs.

Fellowship training and subspecialty board certification offer numerous benefits that likely outweigh the costs of a new “plan.” We don’t want just anyone on call; we want a future full of smart hospitalists who are leading practitioners of QI, education, and scholarship.

Dr. Chen is assistant professor in the department of pediatrics at the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas.

CON

One-size-fits-all approach is not what pediatric hospitalists need

According to Freed et al in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the central goals of a fellowship in pediatric HM include “advanced training in the clinical care of hospitalized patients, quality improvement (QI), and hospital administration.”1 To determine if certification within pediatric hospital medicine should require a fellowship, it is necessary to decide if there are additional skills beyond those obtained during a pediatric residency that are required for practice as a pediatric hospitalist.

Pediatric residencies are designed to provide residents with the skills to practice in the field of general pediatrics. According to Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) standards, just 40% of a resident’s training is required to be in the outpatient setting. There is the expectation that at the end of three years, a resident is capable of spending 95% of their practice in the primary-care setting despite spending less than half of their training in outpatient medicine.

Having a greater focus on inpatient medicine during residency provides a knowledge base that is adequate to start an HM career. As intended, the amount of training dedicated to inpatient and outpatient care in a pediatric residency program is adequate to achieve the skills that make them capable of practicing both inpatient and outpatient care.

Although Freed stated the goal of advanced training, it is unclear what specialized body of knowledge would be gained during a fellowship. The need for advanced clinical training is a concept that is a careerlong, neverending endeavor. Even if this were the reason to require a fellowship, how long is long enough to have mastered clinical care?

One year? Two years? 35 years? If more than half of a three-year residency is not enough time to provide residents the education and training to care for hospitalized inpatients, we should not require more training; we should fix our current training system.

Administrative experience and training in QI and research are important skills that can help advance a hospitalist’s career. It is important to recognize that because these skills are not required for all pediatric hospitalist positions, it would be unnecessary for all hospitalists to attain these skills in a fellowship. In addition, for those interested in administration or research, there are many other ways to attain those skills, including the APA educational scholars program or obtaining a master’s degree in medical education. The added benefit of these avenues for additional skills is that they can be completed throughout a career as a pediatric hospitalist.

As pediatric hospital medicine is a field in its early stages, it is important to consider all options for certification. While fellowship training has been the path for many subspecialties within pediatrics, HM will be better served by recognizing the need to remain inclusive. The positions within HM are broad, and the training should be individualized for the skills each physician requires.

Dr. Eagle is a hospitalist in the general medicine service at The Joseph M. Sanzari Children’s Hospital at Hackensack University Medical Center in New Jersey.

Reference

- Freed G, Dunham K. Characteristics of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships and training programs. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):157-163.

PRO

A powerful tool, subspecialty certification should be adopted—and soon

There are many different ways for pediatric hospital medicine to evolve and gain recognition. Board certification with required fellowship training is the most well-known method. For adult hospitalists, recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) has been established. Residency programs are becoming more innovative, creating additional tracks to provide accelerated fellowship education. What path should be chosen for the future of pediatric hospital medicine?

The decision could be compared to purchasing a cellphone. Simple flip phones are sufficient for making phone calls, just as a graduating pediatrics resident might care for routine inpatients. But the smartphone, like the fellowship/subspecialty certification route, provides advantages that could be worth the additional costs.

You can tell a lot about a person by looking at their cellphone. It often reveals personality traits, professions, and behavioral tendencies. Similarly, administrators, colleagues, and other payors might make assumptions based on fellowship/subspecialty certification status. Pediatric hospitalists should be considered experts in the field of clinical HM, hospital-based research, quality improvement (QI), inpatient procedures, and administrative leadership. Fellowship directors have begun discussing how to standardize these content areas. Subspecialty certification after such training will provide a powerful tool for hospitalists to navigate potentially complex clinical scenarios, hospital bureaucracies and/or academic hierarchies. Fellowship training will add a more concrete identity and standards of quality to our subspecialty.

Smartphones are “smart” because they bring convenience and efficiency. The same can be said about fellowship training. Residency training no longer addresses all the needs of a practicing hospitalist. Although one can attend workshops on QI or research and learn hospital administration, all while on the job, many young hospitalists struggle to adapt quickly early in their career; they might fail to thrive. Fellowship programs would provide a learner-centered environment and protected time to accomplish these goals. Certification would help ensure that trainees have the knowledge and competencies needed for the job. This process, designed to create a well-prepared hospitalist work force, should lead to better advancement within the field, which would mean more hospitalists in meaningful leadership roles and improved quality of hospital care.

The cost of a cellphone and its monthly plan must be taken into account when choosing what purchase. Similarly, the benefits of additional education and recognition must be measured against the costs of additional training. For most, the benefits of well-trained hospitalists outweigh the costs in the long run. Concerns of alienating those without board certification or limiting the work force likely are unfounded. The majority of EDs are staffed by general emergency medicine physicians who do not have pediatric emergency medicine certification—and they all see children, and provide referrals to dedicated children’s facilities when needed. Similarly, community hospital wards can choose to follow suit, depending on their needs.

Fellowship training and subspecialty board certification offer numerous benefits that likely outweigh the costs of a new “plan.” We don’t want just anyone on call; we want a future full of smart hospitalists who are leading practitioners of QI, education, and scholarship.

Dr. Chen is assistant professor in the department of pediatrics at the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas.

CON

One-size-fits-all approach is not what pediatric hospitalists need

According to Freed et al in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the central goals of a fellowship in pediatric HM include “advanced training in the clinical care of hospitalized patients, quality improvement (QI), and hospital administration.”1 To determine if certification within pediatric hospital medicine should require a fellowship, it is necessary to decide if there are additional skills beyond those obtained during a pediatric residency that are required for practice as a pediatric hospitalist.

Pediatric residencies are designed to provide residents with the skills to practice in the field of general pediatrics. According to Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) standards, just 40% of a resident’s training is required to be in the outpatient setting. There is the expectation that at the end of three years, a resident is capable of spending 95% of their practice in the primary-care setting despite spending less than half of their training in outpatient medicine.

Having a greater focus on inpatient medicine during residency provides a knowledge base that is adequate to start an HM career. As intended, the amount of training dedicated to inpatient and outpatient care in a pediatric residency program is adequate to achieve the skills that make them capable of practicing both inpatient and outpatient care.

Although Freed stated the goal of advanced training, it is unclear what specialized body of knowledge would be gained during a fellowship. The need for advanced clinical training is a concept that is a careerlong, neverending endeavor. Even if this were the reason to require a fellowship, how long is long enough to have mastered clinical care?

One year? Two years? 35 years? If more than half of a three-year residency is not enough time to provide residents the education and training to care for hospitalized inpatients, we should not require more training; we should fix our current training system.

Administrative experience and training in QI and research are important skills that can help advance a hospitalist’s career. It is important to recognize that because these skills are not required for all pediatric hospitalist positions, it would be unnecessary for all hospitalists to attain these skills in a fellowship. In addition, for those interested in administration or research, there are many other ways to attain those skills, including the APA educational scholars program or obtaining a master’s degree in medical education. The added benefit of these avenues for additional skills is that they can be completed throughout a career as a pediatric hospitalist.

As pediatric hospital medicine is a field in its early stages, it is important to consider all options for certification. While fellowship training has been the path for many subspecialties within pediatrics, HM will be better served by recognizing the need to remain inclusive. The positions within HM are broad, and the training should be individualized for the skills each physician requires.

Dr. Eagle is a hospitalist in the general medicine service at The Joseph M. Sanzari Children’s Hospital at Hackensack University Medical Center in New Jersey.

Reference

- Freed G, Dunham K. Characteristics of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships and training programs. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):157-163.

PRO

A powerful tool, subspecialty certification should be adopted—and soon

There are many different ways for pediatric hospital medicine to evolve and gain recognition. Board certification with required fellowship training is the most well-known method. For adult hospitalists, recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) has been established. Residency programs are becoming more innovative, creating additional tracks to provide accelerated fellowship education. What path should be chosen for the future of pediatric hospital medicine?

The decision could be compared to purchasing a cellphone. Simple flip phones are sufficient for making phone calls, just as a graduating pediatrics resident might care for routine inpatients. But the smartphone, like the fellowship/subspecialty certification route, provides advantages that could be worth the additional costs.

You can tell a lot about a person by looking at their cellphone. It often reveals personality traits, professions, and behavioral tendencies. Similarly, administrators, colleagues, and other payors might make assumptions based on fellowship/subspecialty certification status. Pediatric hospitalists should be considered experts in the field of clinical HM, hospital-based research, quality improvement (QI), inpatient procedures, and administrative leadership. Fellowship directors have begun discussing how to standardize these content areas. Subspecialty certification after such training will provide a powerful tool for hospitalists to navigate potentially complex clinical scenarios, hospital bureaucracies and/or academic hierarchies. Fellowship training will add a more concrete identity and standards of quality to our subspecialty.

Smartphones are “smart” because they bring convenience and efficiency. The same can be said about fellowship training. Residency training no longer addresses all the needs of a practicing hospitalist. Although one can attend workshops on QI or research and learn hospital administration, all while on the job, many young hospitalists struggle to adapt quickly early in their career; they might fail to thrive. Fellowship programs would provide a learner-centered environment and protected time to accomplish these goals. Certification would help ensure that trainees have the knowledge and competencies needed for the job. This process, designed to create a well-prepared hospitalist work force, should lead to better advancement within the field, which would mean more hospitalists in meaningful leadership roles and improved quality of hospital care.

The cost of a cellphone and its monthly plan must be taken into account when choosing what purchase. Similarly, the benefits of additional education and recognition must be measured against the costs of additional training. For most, the benefits of well-trained hospitalists outweigh the costs in the long run. Concerns of alienating those without board certification or limiting the work force likely are unfounded. The majority of EDs are staffed by general emergency medicine physicians who do not have pediatric emergency medicine certification—and they all see children, and provide referrals to dedicated children’s facilities when needed. Similarly, community hospital wards can choose to follow suit, depending on their needs.

Fellowship training and subspecialty board certification offer numerous benefits that likely outweigh the costs of a new “plan.” We don’t want just anyone on call; we want a future full of smart hospitalists who are leading practitioners of QI, education, and scholarship.

Dr. Chen is assistant professor in the department of pediatrics at the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas.

CON

One-size-fits-all approach is not what pediatric hospitalists need

According to Freed et al in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the central goals of a fellowship in pediatric HM include “advanced training in the clinical care of hospitalized patients, quality improvement (QI), and hospital administration.”1 To determine if certification within pediatric hospital medicine should require a fellowship, it is necessary to decide if there are additional skills beyond those obtained during a pediatric residency that are required for practice as a pediatric hospitalist.

Pediatric residencies are designed to provide residents with the skills to practice in the field of general pediatrics. According to Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) standards, just 40% of a resident’s training is required to be in the outpatient setting. There is the expectation that at the end of three years, a resident is capable of spending 95% of their practice in the primary-care setting despite spending less than half of their training in outpatient medicine.

Having a greater focus on inpatient medicine during residency provides a knowledge base that is adequate to start an HM career. As intended, the amount of training dedicated to inpatient and outpatient care in a pediatric residency program is adequate to achieve the skills that make them capable of practicing both inpatient and outpatient care.

Although Freed stated the goal of advanced training, it is unclear what specialized body of knowledge would be gained during a fellowship. The need for advanced clinical training is a concept that is a careerlong, neverending endeavor. Even if this were the reason to require a fellowship, how long is long enough to have mastered clinical care?

One year? Two years? 35 years? If more than half of a three-year residency is not enough time to provide residents the education and training to care for hospitalized inpatients, we should not require more training; we should fix our current training system.

Administrative experience and training in QI and research are important skills that can help advance a hospitalist’s career. It is important to recognize that because these skills are not required for all pediatric hospitalist positions, it would be unnecessary for all hospitalists to attain these skills in a fellowship. In addition, for those interested in administration or research, there are many other ways to attain those skills, including the APA educational scholars program or obtaining a master’s degree in medical education. The added benefit of these avenues for additional skills is that they can be completed throughout a career as a pediatric hospitalist.

As pediatric hospital medicine is a field in its early stages, it is important to consider all options for certification. While fellowship training has been the path for many subspecialties within pediatrics, HM will be better served by recognizing the need to remain inclusive. The positions within HM are broad, and the training should be individualized for the skills each physician requires.

Dr. Eagle is a hospitalist in the general medicine service at The Joseph M. Sanzari Children’s Hospital at Hackensack University Medical Center in New Jersey.

Reference

- Freed G, Dunham K. Characteristics of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships and training programs. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):157-163.

New Infection-Control Weapons Emerge

New technology that infuses a copper oxide into hard surfaces or fabrics in order to boost infection control could soon become a major weapon in hospitals, according to the CEOs of two Virginia companies now developing such technologies.

Cupron (http://www.cupron.com/), based in Richmond, Va., provides the infusion of a proprietary copper oxide compound into such hard surfaces as flooring, countertops, building components, and furniture, and into fabrics such as gowns, uniforms, and linens, says company chairman Paul Rocheleau. Cupron is partnering with EOS Surfaces (http://eos-surfaces.com/cupron/), based in Portsmouth, Va., a developer of solid countertop surfaces, which company president Ken Trinder says are thicker than comparable building products.

Together, the companies are seeking approval from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to market these products with registrations for their public health claims of preventing hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) caused by bacteria, fungi, and viruses. The products recently were tested against Staphylococcus and Enterobacter bacteria, with 99.9% effectiveness in killing organisms, Rocheleau says.

“It is well known that copper has the ability to kill pathogens,” he adds. “What’s new are the methods to deliver that technology.”

He calls the copper-ion technology an additional layer of infection control, meant not to supplant other hospital protocols but to become part of overall risk-management programs to control HAIs. Other Cupron products, such as anti-odor footwear, are already on the market, but EOS aims to market the hard-surface products to health facilities starting in the second half of this year. “We’re also well advanced on the first of several clinical studies of the impact of Cupron-infused textiles and hard surfaces on infection rates,” Rocheleau says.

Meanwhile, a new “intelligent handwash monitoring system” to promote hand hygiene compliance in order to prevent HAIs that is now being tested in the United Kingdom by the global thermal technology company Irisys (www.irisys.co.uk/) was presented at the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology 2012 conference in June in San Antonio.

It uses non-intrusive therapy sensors deployed throughout healthcare facilities to detect people’s movements and determine accurate counts of handwashing opportunities, which are then compared to actual handwashing (or sanitizing gel) occurrences. The intention is to promote greater compliance with infection-preventing hand hygiene without violating personal privacy, such as through the use of video surveillance.

New technology that infuses a copper oxide into hard surfaces or fabrics in order to boost infection control could soon become a major weapon in hospitals, according to the CEOs of two Virginia companies now developing such technologies.

Cupron (http://www.cupron.com/), based in Richmond, Va., provides the infusion of a proprietary copper oxide compound into such hard surfaces as flooring, countertops, building components, and furniture, and into fabrics such as gowns, uniforms, and linens, says company chairman Paul Rocheleau. Cupron is partnering with EOS Surfaces (http://eos-surfaces.com/cupron/), based in Portsmouth, Va., a developer of solid countertop surfaces, which company president Ken Trinder says are thicker than comparable building products.

Together, the companies are seeking approval from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to market these products with registrations for their public health claims of preventing hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) caused by bacteria, fungi, and viruses. The products recently were tested against Staphylococcus and Enterobacter bacteria, with 99.9% effectiveness in killing organisms, Rocheleau says.

“It is well known that copper has the ability to kill pathogens,” he adds. “What’s new are the methods to deliver that technology.”

He calls the copper-ion technology an additional layer of infection control, meant not to supplant other hospital protocols but to become part of overall risk-management programs to control HAIs. Other Cupron products, such as anti-odor footwear, are already on the market, but EOS aims to market the hard-surface products to health facilities starting in the second half of this year. “We’re also well advanced on the first of several clinical studies of the impact of Cupron-infused textiles and hard surfaces on infection rates,” Rocheleau says.

Meanwhile, a new “intelligent handwash monitoring system” to promote hand hygiene compliance in order to prevent HAIs that is now being tested in the United Kingdom by the global thermal technology company Irisys (www.irisys.co.uk/) was presented at the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology 2012 conference in June in San Antonio.

It uses non-intrusive therapy sensors deployed throughout healthcare facilities to detect people’s movements and determine accurate counts of handwashing opportunities, which are then compared to actual handwashing (or sanitizing gel) occurrences. The intention is to promote greater compliance with infection-preventing hand hygiene without violating personal privacy, such as through the use of video surveillance.

New technology that infuses a copper oxide into hard surfaces or fabrics in order to boost infection control could soon become a major weapon in hospitals, according to the CEOs of two Virginia companies now developing such technologies.

Cupron (http://www.cupron.com/), based in Richmond, Va., provides the infusion of a proprietary copper oxide compound into such hard surfaces as flooring, countertops, building components, and furniture, and into fabrics such as gowns, uniforms, and linens, says company chairman Paul Rocheleau. Cupron is partnering with EOS Surfaces (http://eos-surfaces.com/cupron/), based in Portsmouth, Va., a developer of solid countertop surfaces, which company president Ken Trinder says are thicker than comparable building products.

Together, the companies are seeking approval from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to market these products with registrations for their public health claims of preventing hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) caused by bacteria, fungi, and viruses. The products recently were tested against Staphylococcus and Enterobacter bacteria, with 99.9% effectiveness in killing organisms, Rocheleau says.

“It is well known that copper has the ability to kill pathogens,” he adds. “What’s new are the methods to deliver that technology.”

He calls the copper-ion technology an additional layer of infection control, meant not to supplant other hospital protocols but to become part of overall risk-management programs to control HAIs. Other Cupron products, such as anti-odor footwear, are already on the market, but EOS aims to market the hard-surface products to health facilities starting in the second half of this year. “We’re also well advanced on the first of several clinical studies of the impact of Cupron-infused textiles and hard surfaces on infection rates,” Rocheleau says.

Meanwhile, a new “intelligent handwash monitoring system” to promote hand hygiene compliance in order to prevent HAIs that is now being tested in the United Kingdom by the global thermal technology company Irisys (www.irisys.co.uk/) was presented at the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology 2012 conference in June in San Antonio.

It uses non-intrusive therapy sensors deployed throughout healthcare facilities to detect people’s movements and determine accurate counts of handwashing opportunities, which are then compared to actual handwashing (or sanitizing gel) occurrences. The intention is to promote greater compliance with infection-preventing hand hygiene without violating personal privacy, such as through the use of video surveillance.

Demographics Correlate with Physician Web Technology Use

A new study in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association offers demographic predictors of physicians and their usage of web-based communication technologies.1 Younger, male doctors who have privileges at a teaching hospital were better predictors of the use of various technologies during the previous six months than were practice-based characteristics, such as specialty, setting, years in practice, or number of patients treated. Communication strategies tallied included using portable devices to access the Internet, visiting social networking websites, communicating by email with patients, listening to podcasts, or writing blog posts.

Lead author Crystale Purvis Cooper, PhD, a researcher at the Soltera Center for Cancer Prevention and Control in Tucson, Ariz., and colleagues drew upon 2009 data from 1,750 physicians in DocStyles, an annual survey of physicians and other health professionals conducted by communications firm Porter Novelli.

References

A new study in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association offers demographic predictors of physicians and their usage of web-based communication technologies.1 Younger, male doctors who have privileges at a teaching hospital were better predictors of the use of various technologies during the previous six months than were practice-based characteristics, such as specialty, setting, years in practice, or number of patients treated. Communication strategies tallied included using portable devices to access the Internet, visiting social networking websites, communicating by email with patients, listening to podcasts, or writing blog posts.

Lead author Crystale Purvis Cooper, PhD, a researcher at the Soltera Center for Cancer Prevention and Control in Tucson, Ariz., and colleagues drew upon 2009 data from 1,750 physicians in DocStyles, an annual survey of physicians and other health professionals conducted by communications firm Porter Novelli.

References

A new study in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association offers demographic predictors of physicians and their usage of web-based communication technologies.1 Younger, male doctors who have privileges at a teaching hospital were better predictors of the use of various technologies during the previous six months than were practice-based characteristics, such as specialty, setting, years in practice, or number of patients treated. Communication strategies tallied included using portable devices to access the Internet, visiting social networking websites, communicating by email with patients, listening to podcasts, or writing blog posts.

Lead author Crystale Purvis Cooper, PhD, a researcher at the Soltera Center for Cancer Prevention and Control in Tucson, Ariz., and colleagues drew upon 2009 data from 1,750 physicians in DocStyles, an annual survey of physicians and other health professionals conducted by communications firm Porter Novelli.

References

Hospitalist-Run Observation Unit Demonstrates Financial Viability

A hospital observation unit run by hospitalists rather than the more typical model led by ED physicians can be financially viable, suggests an abstract presented at HM12 in April in San Diego. One such unit generated $915,000 in facility fee charges, and during a three-month audit posted net revenue of $49,000; the unit also reduced patients’ length of stay (LOS) on observation status by 25%, according to lead author Mary Maher, MD, a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center.1

Previously, Denver Health’s ED had informally operated a small observation unit, primarily for patients with such diagnoses as low-risk chest pain. But due to increasing numbers of observation admissions and the need to manage their flow through the typically full safety-net teaching hospital, the hospitalist department was asked in 2011 to develop a new, hospitalist-run unit, Dr. Maher explains.

In its first six months of operation, the five-bed observation unit cared for 648 patients, with 12% admitted to the hospital. A single hospitalist and mid-level practitioner cover each shift, with additional responsibilities for managing patient flow and new hospital admissions. Dr. Maher says specialized nursing staffers are now familiar with the hospital’s admission criteria and care pathways for common diagnoses. A typical observation patient has chest pain and a history of coronary artery disease but negative clinical markers. Other common diagnoses, with established clinical pathways and discharge criteria, include asthma, syncope, COPD, and gastrointestinal illness.

“Hospitalists are primed to take care of patients who are in this observation status,” Dr. Maher says. “They are a little more complex than patients typically seen in emergency department units. The challenge for hospitalists is to understand the hospital’s admission guidelines and to work collaboratively with utilization management staff.”

Denver Health uses the Milliman Care Guidelines to guide inpatient admissions, but these can be difficult to translate into clinical practice and require some study by physicians, she adds.2 For more information about the poster and the unit, email [email protected].

References

- Maher M, Mascolo M, Mancini D, et al. Creation of a financially viable hospitalist-run observation unit in a safety net hospital. Paper presented at Hospital Medicine 2012, April 1-4, 2012, San Diego.

- Milliman Inc. Milliman Care Guidelines. Milliman Inc. website. Available at: http://www.milliman.com/expertise/healthcare/products-tools/milliman-care-guidelines/. Accessed July 8, 2012.

A hospital observation unit run by hospitalists rather than the more typical model led by ED physicians can be financially viable, suggests an abstract presented at HM12 in April in San Diego. One such unit generated $915,000 in facility fee charges, and during a three-month audit posted net revenue of $49,000; the unit also reduced patients’ length of stay (LOS) on observation status by 25%, according to lead author Mary Maher, MD, a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center.1

Previously, Denver Health’s ED had informally operated a small observation unit, primarily for patients with such diagnoses as low-risk chest pain. But due to increasing numbers of observation admissions and the need to manage their flow through the typically full safety-net teaching hospital, the hospitalist department was asked in 2011 to develop a new, hospitalist-run unit, Dr. Maher explains.

In its first six months of operation, the five-bed observation unit cared for 648 patients, with 12% admitted to the hospital. A single hospitalist and mid-level practitioner cover each shift, with additional responsibilities for managing patient flow and new hospital admissions. Dr. Maher says specialized nursing staffers are now familiar with the hospital’s admission criteria and care pathways for common diagnoses. A typical observation patient has chest pain and a history of coronary artery disease but negative clinical markers. Other common diagnoses, with established clinical pathways and discharge criteria, include asthma, syncope, COPD, and gastrointestinal illness.

“Hospitalists are primed to take care of patients who are in this observation status,” Dr. Maher says. “They are a little more complex than patients typically seen in emergency department units. The challenge for hospitalists is to understand the hospital’s admission guidelines and to work collaboratively with utilization management staff.”

Denver Health uses the Milliman Care Guidelines to guide inpatient admissions, but these can be difficult to translate into clinical practice and require some study by physicians, she adds.2 For more information about the poster and the unit, email [email protected].

References

- Maher M, Mascolo M, Mancini D, et al. Creation of a financially viable hospitalist-run observation unit in a safety net hospital. Paper presented at Hospital Medicine 2012, April 1-4, 2012, San Diego.

- Milliman Inc. Milliman Care Guidelines. Milliman Inc. website. Available at: http://www.milliman.com/expertise/healthcare/products-tools/milliman-care-guidelines/. Accessed July 8, 2012.

A hospital observation unit run by hospitalists rather than the more typical model led by ED physicians can be financially viable, suggests an abstract presented at HM12 in April in San Diego. One such unit generated $915,000 in facility fee charges, and during a three-month audit posted net revenue of $49,000; the unit also reduced patients’ length of stay (LOS) on observation status by 25%, according to lead author Mary Maher, MD, a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center.1

Previously, Denver Health’s ED had informally operated a small observation unit, primarily for patients with such diagnoses as low-risk chest pain. But due to increasing numbers of observation admissions and the need to manage their flow through the typically full safety-net teaching hospital, the hospitalist department was asked in 2011 to develop a new, hospitalist-run unit, Dr. Maher explains.

In its first six months of operation, the five-bed observation unit cared for 648 patients, with 12% admitted to the hospital. A single hospitalist and mid-level practitioner cover each shift, with additional responsibilities for managing patient flow and new hospital admissions. Dr. Maher says specialized nursing staffers are now familiar with the hospital’s admission criteria and care pathways for common diagnoses. A typical observation patient has chest pain and a history of coronary artery disease but negative clinical markers. Other common diagnoses, with established clinical pathways and discharge criteria, include asthma, syncope, COPD, and gastrointestinal illness.

“Hospitalists are primed to take care of patients who are in this observation status,” Dr. Maher says. “They are a little more complex than patients typically seen in emergency department units. The challenge for hospitalists is to understand the hospital’s admission guidelines and to work collaboratively with utilization management staff.”

Denver Health uses the Milliman Care Guidelines to guide inpatient admissions, but these can be difficult to translate into clinical practice and require some study by physicians, she adds.2 For more information about the poster and the unit, email [email protected].

References

- Maher M, Mascolo M, Mancini D, et al. Creation of a financially viable hospitalist-run observation unit in a safety net hospital. Paper presented at Hospital Medicine 2012, April 1-4, 2012, San Diego.

- Milliman Inc. Milliman Care Guidelines. Milliman Inc. website. Available at: http://www.milliman.com/expertise/healthcare/products-tools/milliman-care-guidelines/. Accessed July 8, 2012.

Family-Medicine-Trained Hospitalists Fit to Handle ID Issues

In response to Dr. Leland Allen and his contention that family medicine hospitalists are less prepared to handle inpatient infectious disease (ID) issues in Birmingham, Ala., I would like to point out the following:

- Family medicine hospitalists do have much more outpatient training than internal medicine (IM) residents, and in the early part of their careers, they will be at a slight disadvantage. After a year or so, the difference will be nil.

- The additional exposure to outpatient care allows family medicine graduates to be in a better position to integrate care of hospitalized patients from Day One.

We have internal medicine and family medicine working together well on our hospitalist teams. Other programs should consider the advantages of benefiting from adding family medicine hospitalists to their teams.

Bob Hollis,

SEP Hospitalists,

Florence, Ky.

In response to Dr. Leland Allen and his contention that family medicine hospitalists are less prepared to handle inpatient infectious disease (ID) issues in Birmingham, Ala., I would like to point out the following:

- Family medicine hospitalists do have much more outpatient training than internal medicine (IM) residents, and in the early part of their careers, they will be at a slight disadvantage. After a year or so, the difference will be nil.

- The additional exposure to outpatient care allows family medicine graduates to be in a better position to integrate care of hospitalized patients from Day One.

We have internal medicine and family medicine working together well on our hospitalist teams. Other programs should consider the advantages of benefiting from adding family medicine hospitalists to their teams.

Bob Hollis,

SEP Hospitalists,

Florence, Ky.

In response to Dr. Leland Allen and his contention that family medicine hospitalists are less prepared to handle inpatient infectious disease (ID) issues in Birmingham, Ala., I would like to point out the following:

- Family medicine hospitalists do have much more outpatient training than internal medicine (IM) residents, and in the early part of their careers, they will be at a slight disadvantage. After a year or so, the difference will be nil.

- The additional exposure to outpatient care allows family medicine graduates to be in a better position to integrate care of hospitalized patients from Day One.

We have internal medicine and family medicine working together well on our hospitalist teams. Other programs should consider the advantages of benefiting from adding family medicine hospitalists to their teams.

Bob Hollis,

SEP Hospitalists,

Florence, Ky.

Replenishing the Primary Care Physician Pipeline

A recent survey of nearly 1,000 students from three medical schools found that just 15% planned to become primary-care physicians, including 11.2% of first-year students.1

That startlingly low number might not be reflective of the whole country, and other national surveys have suggested significantly higher rates. But the responses underscore some important contributors beyond financial concerns that include a more negative overall view of PCPs’ work life compared to that of specialists. “Our data suggest that although medical school does not create these negative views of primary-care work life, it may reinforce them,” the authors write.

Conversely, the results suggest that time spent observing physicians could help break negative stereotypes about the ability to develop good relationships with patients, and that career plans might not be based on perceptions, but rather on values and goals. “The study reinforces the importance of admitting students with primary-care-oriented values and primary-care interest and reinforcing those values over the course of medical school,” the authors conclude.

“Maybe we’re not selecting medical students in the optimal way for what society needs,” says Elbert Huang, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago. By emphasizing GPA and test scores, “maybe when you do that, you end with people who don’t want to actually take care of patients in primary care.”

Other studies suggest he’s on to something. Research conducted by the Washington, D.C.-based Robert Graham Center found that students in rural medical schools are significantly more likely to go into rural healthcare and primary care than students in urban medical schools.

“The problem there is that we’ve cut the number of people from rural areas going to medical school by half over the last 20 years,” center director Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, says. “A lot of students just don’t have the background to make them competitive.” Many students in minority communities face similar challenges.

Ed Salsberg, director of the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis in the Health Resources and Services Administration, says many newer osteopathic schools are positioning themselves in rural communities, helping them attract students who might not have gone to medical school otherwise.

Reaching back even earlier into the pipeline to help mentor elementary and high school students might be another way to help build capacity. Medical organizations also seem to be getting the message. New MCAT recommendations by the Association of American Medical Colleges, for example, place less emphasis on scientific knowledge in favor of a more holistic assessment of critical analysis and reasoning skills. The association also is encouraging medical schools to pay more attention to such personal characteristics as integrity and service orientation.

“That’s more of a long-term strategy, but I think it has an impact on who gets recruited to medical school,” Salsberg says.

Reference

A recent survey of nearly 1,000 students from three medical schools found that just 15% planned to become primary-care physicians, including 11.2% of first-year students.1

That startlingly low number might not be reflective of the whole country, and other national surveys have suggested significantly higher rates. But the responses underscore some important contributors beyond financial concerns that include a more negative overall view of PCPs’ work life compared to that of specialists. “Our data suggest that although medical school does not create these negative views of primary-care work life, it may reinforce them,” the authors write.

Conversely, the results suggest that time spent observing physicians could help break negative stereotypes about the ability to develop good relationships with patients, and that career plans might not be based on perceptions, but rather on values and goals. “The study reinforces the importance of admitting students with primary-care-oriented values and primary-care interest and reinforcing those values over the course of medical school,” the authors conclude.

“Maybe we’re not selecting medical students in the optimal way for what society needs,” says Elbert Huang, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago. By emphasizing GPA and test scores, “maybe when you do that, you end with people who don’t want to actually take care of patients in primary care.”

Other studies suggest he’s on to something. Research conducted by the Washington, D.C.-based Robert Graham Center found that students in rural medical schools are significantly more likely to go into rural healthcare and primary care than students in urban medical schools.

“The problem there is that we’ve cut the number of people from rural areas going to medical school by half over the last 20 years,” center director Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, says. “A lot of students just don’t have the background to make them competitive.” Many students in minority communities face similar challenges.

Ed Salsberg, director of the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis in the Health Resources and Services Administration, says many newer osteopathic schools are positioning themselves in rural communities, helping them attract students who might not have gone to medical school otherwise.

Reaching back even earlier into the pipeline to help mentor elementary and high school students might be another way to help build capacity. Medical organizations also seem to be getting the message. New MCAT recommendations by the Association of American Medical Colleges, for example, place less emphasis on scientific knowledge in favor of a more holistic assessment of critical analysis and reasoning skills. The association also is encouraging medical schools to pay more attention to such personal characteristics as integrity and service orientation.

“That’s more of a long-term strategy, but I think it has an impact on who gets recruited to medical school,” Salsberg says.

Reference

A recent survey of nearly 1,000 students from three medical schools found that just 15% planned to become primary-care physicians, including 11.2% of first-year students.1

That startlingly low number might not be reflective of the whole country, and other national surveys have suggested significantly higher rates. But the responses underscore some important contributors beyond financial concerns that include a more negative overall view of PCPs’ work life compared to that of specialists. “Our data suggest that although medical school does not create these negative views of primary-care work life, it may reinforce them,” the authors write.

Conversely, the results suggest that time spent observing physicians could help break negative stereotypes about the ability to develop good relationships with patients, and that career plans might not be based on perceptions, but rather on values and goals. “The study reinforces the importance of admitting students with primary-care-oriented values and primary-care interest and reinforcing those values over the course of medical school,” the authors conclude.

“Maybe we’re not selecting medical students in the optimal way for what society needs,” says Elbert Huang, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago. By emphasizing GPA and test scores, “maybe when you do that, you end with people who don’t want to actually take care of patients in primary care.”

Other studies suggest he’s on to something. Research conducted by the Washington, D.C.-based Robert Graham Center found that students in rural medical schools are significantly more likely to go into rural healthcare and primary care than students in urban medical schools.

“The problem there is that we’ve cut the number of people from rural areas going to medical school by half over the last 20 years,” center director Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, says. “A lot of students just don’t have the background to make them competitive.” Many students in minority communities face similar challenges.

Ed Salsberg, director of the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis in the Health Resources and Services Administration, says many newer osteopathic schools are positioning themselves in rural communities, helping them attract students who might not have gone to medical school otherwise.

Reaching back even earlier into the pipeline to help mentor elementary and high school students might be another way to help build capacity. Medical organizations also seem to be getting the message. New MCAT recommendations by the Association of American Medical Colleges, for example, place less emphasis on scientific knowledge in favor of a more holistic assessment of critical analysis and reasoning skills. The association also is encouraging medical schools to pay more attention to such personal characteristics as integrity and service orientation.

“That’s more of a long-term strategy, but I think it has an impact on who gets recruited to medical school,” Salsberg says.

Reference

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: L.A. Care Health Plan's Z. Joseph Wanski discusses efforts to prevent 30-day readmissions

Click here to listen to Dr. Wanski

Click here to listen to Dr. Wanski

Click here to listen to Dr. Wanski

Psychiatric Hospitalist Model Supported by New Outcomes Research from UK

Unpublished data from a British study of dedicated psychiatric hospitalists shows clear improvements in 17 of 23 measured outcomes, according to the study's lead researcher.

Julian Beezhold, MD, a consultant in emergency psychiatry at Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (formerly Norfolk and Waveney Mental Health Foundation Trust) presented the data at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in May in Philadelphia.

The researchers investigated 5,000 patients over nearly eight years. By switching coverage from 13 consultant psychiatrists to dedicated-unit psychiatric hospitalists, the study showed lengths of stay on two inpatient psychiatry units cut in half (just over 11 days from nearly 22 days). Researchers also found reductions in violent episodes and self-harm. Demand for beds on the units declined steadily during the study, resulting in consolidation down to one unit.

"We found overwhelming, robust evidence showing clear benefit from a hospitalist model of care," Dr. Beezhold says. "We found that dedicated doctors are able to achieve better quality of care simply because they are there, able to respond to crises and to change treatment plans more quickly when that is needed."

Psychiatry practice differs from most specialty practice in the United Kingdom, he adds, but the recent trend has been toward a larger division between office-based and hospital-based practices.

In the U.S., models of coverage for acute psychiatric patients include specialized psychiatric hospitals, dedicated psychiatric units within general hospitals, and patients admitted to general hospital units whose psychiatric care is managed by consultation-liaison psychiatrists, says Abigail Donovan, MD, a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

"At Mass General, we have access to all of these approaches," she says, adding that the new data "reinforces the way we've been doing things with dedicated psychiatric hospitalists—showing the tangible results of this model."

Unpublished data from a British study of dedicated psychiatric hospitalists shows clear improvements in 17 of 23 measured outcomes, according to the study's lead researcher.

Julian Beezhold, MD, a consultant in emergency psychiatry at Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (formerly Norfolk and Waveney Mental Health Foundation Trust) presented the data at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in May in Philadelphia.

The researchers investigated 5,000 patients over nearly eight years. By switching coverage from 13 consultant psychiatrists to dedicated-unit psychiatric hospitalists, the study showed lengths of stay on two inpatient psychiatry units cut in half (just over 11 days from nearly 22 days). Researchers also found reductions in violent episodes and self-harm. Demand for beds on the units declined steadily during the study, resulting in consolidation down to one unit.

"We found overwhelming, robust evidence showing clear benefit from a hospitalist model of care," Dr. Beezhold says. "We found that dedicated doctors are able to achieve better quality of care simply because they are there, able to respond to crises and to change treatment plans more quickly when that is needed."

Psychiatry practice differs from most specialty practice in the United Kingdom, he adds, but the recent trend has been toward a larger division between office-based and hospital-based practices.

In the U.S., models of coverage for acute psychiatric patients include specialized psychiatric hospitals, dedicated psychiatric units within general hospitals, and patients admitted to general hospital units whose psychiatric care is managed by consultation-liaison psychiatrists, says Abigail Donovan, MD, a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

"At Mass General, we have access to all of these approaches," she says, adding that the new data "reinforces the way we've been doing things with dedicated psychiatric hospitalists—showing the tangible results of this model."

Unpublished data from a British study of dedicated psychiatric hospitalists shows clear improvements in 17 of 23 measured outcomes, according to the study's lead researcher.

Julian Beezhold, MD, a consultant in emergency psychiatry at Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (formerly Norfolk and Waveney Mental Health Foundation Trust) presented the data at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in May in Philadelphia.

The researchers investigated 5,000 patients over nearly eight years. By switching coverage from 13 consultant psychiatrists to dedicated-unit psychiatric hospitalists, the study showed lengths of stay on two inpatient psychiatry units cut in half (just over 11 days from nearly 22 days). Researchers also found reductions in violent episodes and self-harm. Demand for beds on the units declined steadily during the study, resulting in consolidation down to one unit.

"We found overwhelming, robust evidence showing clear benefit from a hospitalist model of care," Dr. Beezhold says. "We found that dedicated doctors are able to achieve better quality of care simply because they are there, able to respond to crises and to change treatment plans more quickly when that is needed."

Psychiatry practice differs from most specialty practice in the United Kingdom, he adds, but the recent trend has been toward a larger division between office-based and hospital-based practices.

In the U.S., models of coverage for acute psychiatric patients include specialized psychiatric hospitals, dedicated psychiatric units within general hospitals, and patients admitted to general hospital units whose psychiatric care is managed by consultation-liaison psychiatrists, says Abigail Donovan, MD, a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

"At Mass General, we have access to all of these approaches," she says, adding that the new data "reinforces the way we've been doing things with dedicated psychiatric hospitalists—showing the tangible results of this model."

Tech Takes Off: Videoconferences in medical settings is more acceptable and affordable, but hurdles remain

Picture this likely scenario: You’re a hospitalist in a remote setting, and a patient with stroke symptoms is rushed in by ambulance. Numbness has overcome one side of his body. Dizziness disrupts his balance, his speech becomes slurred, and his vision is blurred. Treatment must be started swiftly to halt irreversible brain damage. The nearest neurologist is located hours away, but thanks to advanced video technology, you’re able to instantly consult face to face with that specialist to help ensure optimal recovery for the patient.

Such applications of telemedicine are becoming more mainstream and affordable, facilitating discussions and decisions between healthcare providers while improving patient access to specialty care in emergencies and other situations.

Remote hospitalist services include videoconferencing for patient monitoring and assessment of various clinical services, says Jona

Advantages and Challenges

Remote patient monitoring in ICUs is on the upswing, filling gaps in the shortage of physicians specializing in critical care. Some unit administrators have established off-site command centers for these specialists to follow multiple facilities with the assistance of video technology and to intervene at urgent times.1

In a neonatal ICU, this type of live-feed technology allows for a face-to-face interaction with a pediatric pulmonologist, for example, when a premature infant is exhibiting symptoms of respiratory distress in the middle of the night, says David Cattell-Gordon, MSW, director of the Office of Telemedicine at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Similarly, in rural areas where women don’t have immediate access to high-risk obstetricians, telemedicine makes it possible to consult with maternal-fetal medicine specialists from a distance, boosting the chances for pregnant mothers with complex conditions to carry healthy babies to term, says Cattell-Gordon. “Our approach has been to bring telemedicine to hospitals and clinics in communities where that resource [specialists] otherwise is unavailable,” he adds.

—Matthew Harbison, MD, medical director, Sound Physicians hospitalist services, Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center

Compared with telephone conversations, the advantages of video consultations are multifold: They display a patient’s facial expressions, gestures, and other body language, which might assist with the diagnosis and prescribed treatment, says Kerry Weiner, MD, chief clinical officer for IPC: The Hospitalist Company in North Hollywood, Calif., which has a presence in about 900 facilities in 25 states.

When the strength of that assessment depends on visual inspection, the technology can be particularly helpful. “The weak part of it is when you need to touch” to guide that assessment, Dr. Weiner says. That’s when the technology isn’t as useful. Still, he adds, “We use teleconferencing all over the place in a Skype-like manner, only more sophisticated. It’s more encrypted.”

Interacting within a secure network is crucial to protect privacy, says Peter Kragel, MD, clinical director of the Telemedicine Center at East Carolina University’s Brody School of Medicine in Greenville, N.C. As with any form of communication that transmits identifiable patient information, healthcare providers must comply with HIPAA guidelines when employing videoconferencing services similar to Skype.

“Because of concerns about compliance with encryption and confidentiality regulations, we do not use [videoconferencing] here,” Dr. Kragel says.

Additionally, “telemedicine isn’t always appropriate for patient care,” Linkous says. “All of this depends on the circumstances and needs of the patient. Obviously, surgery requires a direct physician-patient interaction, except for robotic surgery.” For hospitals that don’t have any neurology coverage, telemedicine robots can assist with outside consults for time-sensitive stroke care.

—Jonathan D. Linkous, CEO, American Telemedicine Association

Videoconferencing isn’t necessary for all telemedicine encounters, Linkous says. Teledermatology and retinal screening use “store and forward” communication of images, which allows for the electronic transmission of images and documents in non-emergent situations in which immediate video isn’t necessary.

“As a society, we’ve become more comfortable with the technology,” says Matthew Harbison, MD, medical director of Sound Physicians hospitalist services at Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center in Houston. “And as the technology continues to develop, ultimately there will be [more of] a role, but how large that will be is difficult to predict.” He adds that “the advantages are obviously in low-staffed places or staffing-challenged sites.”

Moving Ahead

As experts continue to iron out the kinks and as communities obtain greater access to broadband signals, telemedicine equipment is moving to advanced high-definition platforms. Meanwhile, the expense has come down considerably since its inception in the mid-1990s. A high-definition setup that once cost upward of $130,000 is now available for less than $10,000, Cattell-Gordon says.

The digital transmission also can assist in patient follow-up after discharge from the hospital and in monitoring various chronic diseases from home. It’s an effective tool for medical staff meetings and training purposes as well.

IPC's hospitalists have been using the technology to communicate with each other, brainstorming across regions of the country. “Because we’re a national company,” Dr. Weiner says, “this has changed the game in terms of being able to collaborate.”

Susan Kreimer is a freelance medical writer based in New York.

Reference

1. Thomas EJ, Lucke JF, Wueste L, Weavind L, Patel B. Association of telemedicine for remote monitoring of intensive care patients with mortality, complications, and length of stay. JAMA. 2009;302:2671-2678.

Picture this likely scenario: You’re a hospitalist in a remote setting, and a patient with stroke symptoms is rushed in by ambulance. Numbness has overcome one side of his body. Dizziness disrupts his balance, his speech becomes slurred, and his vision is blurred. Treatment must be started swiftly to halt irreversible brain damage. The nearest neurologist is located hours away, but thanks to advanced video technology, you’re able to instantly consult face to face with that specialist to help ensure optimal recovery for the patient.

Such applications of telemedicine are becoming more mainstream and affordable, facilitating discussions and decisions between healthcare providers while improving patient access to specialty care in emergencies and other situations.

Remote hospitalist services include videoconferencing for patient monitoring and assessment of various clinical services, says Jona

Advantages and Challenges

Remote patient monitoring in ICUs is on the upswing, filling gaps in the shortage of physicians specializing in critical care. Some unit administrators have established off-site command centers for these specialists to follow multiple facilities with the assistance of video technology and to intervene at urgent times.1

In a neonatal ICU, this type of live-feed technology allows for a face-to-face interaction with a pediatric pulmonologist, for example, when a premature infant is exhibiting symptoms of respiratory distress in the middle of the night, says David Cattell-Gordon, MSW, director of the Office of Telemedicine at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Similarly, in rural areas where women don’t have immediate access to high-risk obstetricians, telemedicine makes it possible to consult with maternal-fetal medicine specialists from a distance, boosting the chances for pregnant mothers with complex conditions to carry healthy babies to term, says Cattell-Gordon. “Our approach has been to bring telemedicine to hospitals and clinics in communities where that resource [specialists] otherwise is unavailable,” he adds.

—Matthew Harbison, MD, medical director, Sound Physicians hospitalist services, Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center

Compared with telephone conversations, the advantages of video consultations are multifold: They display a patient’s facial expressions, gestures, and other body language, which might assist with the diagnosis and prescribed treatment, says Kerry Weiner, MD, chief clinical officer for IPC: The Hospitalist Company in North Hollywood, Calif., which has a presence in about 900 facilities in 25 states.

When the strength of that assessment depends on visual inspection, the technology can be particularly helpful. “The weak part of it is when you need to touch” to guide that assessment, Dr. Weiner says. That’s when the technology isn’t as useful. Still, he adds, “We use teleconferencing all over the place in a Skype-like manner, only more sophisticated. It’s more encrypted.”

Interacting within a secure network is crucial to protect privacy, says Peter Kragel, MD, clinical director of the Telemedicine Center at East Carolina University’s Brody School of Medicine in Greenville, N.C. As with any form of communication that transmits identifiable patient information, healthcare providers must comply with HIPAA guidelines when employing videoconferencing services similar to Skype.

“Because of concerns about compliance with encryption and confidentiality regulations, we do not use [videoconferencing] here,” Dr. Kragel says.

Additionally, “telemedicine isn’t always appropriate for patient care,” Linkous says. “All of this depends on the circumstances and needs of the patient. Obviously, surgery requires a direct physician-patient interaction, except for robotic surgery.” For hospitals that don’t have any neurology coverage, telemedicine robots can assist with outside consults for time-sensitive stroke care.

—Jonathan D. Linkous, CEO, American Telemedicine Association

Videoconferencing isn’t necessary for all telemedicine encounters, Linkous says. Teledermatology and retinal screening use “store and forward” communication of images, which allows for the electronic transmission of images and documents in non-emergent situations in which immediate video isn’t necessary.

“As a society, we’ve become more comfortable with the technology,” says Matthew Harbison, MD, medical director of Sound Physicians hospitalist services at Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center in Houston. “And as the technology continues to develop, ultimately there will be [more of] a role, but how large that will be is difficult to predict.” He adds that “the advantages are obviously in low-staffed places or staffing-challenged sites.”

Moving Ahead

As experts continue to iron out the kinks and as communities obtain greater access to broadband signals, telemedicine equipment is moving to advanced high-definition platforms. Meanwhile, the expense has come down considerably since its inception in the mid-1990s. A high-definition setup that once cost upward of $130,000 is now available for less than $10,000, Cattell-Gordon says.

The digital transmission also can assist in patient follow-up after discharge from the hospital and in monitoring various chronic diseases from home. It’s an effective tool for medical staff meetings and training purposes as well.

IPC's hospitalists have been using the technology to communicate with each other, brainstorming across regions of the country. “Because we’re a national company,” Dr. Weiner says, “this has changed the game in terms of being able to collaborate.”

Susan Kreimer is a freelance medical writer based in New York.

Reference

1. Thomas EJ, Lucke JF, Wueste L, Weavind L, Patel B. Association of telemedicine for remote monitoring of intensive care patients with mortality, complications, and length of stay. JAMA. 2009;302:2671-2678.

Picture this likely scenario: You’re a hospitalist in a remote setting, and a patient with stroke symptoms is rushed in by ambulance. Numbness has overcome one side of his body. Dizziness disrupts his balance, his speech becomes slurred, and his vision is blurred. Treatment must be started swiftly to halt irreversible brain damage. The nearest neurologist is located hours away, but thanks to advanced video technology, you’re able to instantly consult face to face with that specialist to help ensure optimal recovery for the patient.

Such applications of telemedicine are becoming more mainstream and affordable, facilitating discussions and decisions between healthcare providers while improving patient access to specialty care in emergencies and other situations.

Remote hospitalist services include videoconferencing for patient monitoring and assessment of various clinical services, says Jona

Advantages and Challenges

Remote patient monitoring in ICUs is on the upswing, filling gaps in the shortage of physicians specializing in critical care. Some unit administrators have established off-site command centers for these specialists to follow multiple facilities with the assistance of video technology and to intervene at urgent times.1

In a neonatal ICU, this type of live-feed technology allows for a face-to-face interaction with a pediatric pulmonologist, for example, when a premature infant is exhibiting symptoms of respiratory distress in the middle of the night, says David Cattell-Gordon, MSW, director of the Office of Telemedicine at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Similarly, in rural areas where women don’t have immediate access to high-risk obstetricians, telemedicine makes it possible to consult with maternal-fetal medicine specialists from a distance, boosting the chances for pregnant mothers with complex conditions to carry healthy babies to term, says Cattell-Gordon. “Our approach has been to bring telemedicine to hospitals and clinics in communities where that resource [specialists] otherwise is unavailable,” he adds.

—Matthew Harbison, MD, medical director, Sound Physicians hospitalist services, Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center

Compared with telephone conversations, the advantages of video consultations are multifold: They display a patient’s facial expressions, gestures, and other body language, which might assist with the diagnosis and prescribed treatment, says Kerry Weiner, MD, chief clinical officer for IPC: The Hospitalist Company in North Hollywood, Calif., which has a presence in about 900 facilities in 25 states.

When the strength of that assessment depends on visual inspection, the technology can be particularly helpful. “The weak part of it is when you need to touch” to guide that assessment, Dr. Weiner says. That’s when the technology isn’t as useful. Still, he adds, “We use teleconferencing all over the place in a Skype-like manner, only more sophisticated. It’s more encrypted.”

Interacting within a secure network is crucial to protect privacy, says Peter Kragel, MD, clinical director of the Telemedicine Center at East Carolina University’s Brody School of Medicine in Greenville, N.C. As with any form of communication that transmits identifiable patient information, healthcare providers must comply with HIPAA guidelines when employing videoconferencing services similar to Skype.

“Because of concerns about compliance with encryption and confidentiality regulations, we do not use [videoconferencing] here,” Dr. Kragel says.

Additionally, “telemedicine isn’t always appropriate for patient care,” Linkous says. “All of this depends on the circumstances and needs of the patient. Obviously, surgery requires a direct physician-patient interaction, except for robotic surgery.” For hospitals that don’t have any neurology coverage, telemedicine robots can assist with outside consults for time-sensitive stroke care.

—Jonathan D. Linkous, CEO, American Telemedicine Association

Videoconferencing isn’t necessary for all telemedicine encounters, Linkous says. Teledermatology and retinal screening use “store and forward” communication of images, which allows for the electronic transmission of images and documents in non-emergent situations in which immediate video isn’t necessary.

“As a society, we’ve become more comfortable with the technology,” says Matthew Harbison, MD, medical director of Sound Physicians hospitalist services at Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center in Houston. “And as the technology continues to develop, ultimately there will be [more of] a role, but how large that will be is difficult to predict.” He adds that “the advantages are obviously in low-staffed places or staffing-challenged sites.”

Moving Ahead

As experts continue to iron out the kinks and as communities obtain greater access to broadband signals, telemedicine equipment is moving to advanced high-definition platforms. Meanwhile, the expense has come down considerably since its inception in the mid-1990s. A high-definition setup that once cost upward of $130,000 is now available for less than $10,000, Cattell-Gordon says.

The digital transmission also can assist in patient follow-up after discharge from the hospital and in monitoring various chronic diseases from home. It’s an effective tool for medical staff meetings and training purposes as well.

IPC's hospitalists have been using the technology to communicate with each other, brainstorming across regions of the country. “Because we’re a national company,” Dr. Weiner says, “this has changed the game in terms of being able to collaborate.”

Susan Kreimer is a freelance medical writer based in New York.

Reference

1. Thomas EJ, Lucke JF, Wueste L, Weavind L, Patel B. Association of telemedicine for remote monitoring of intensive care patients with mortality, complications, and length of stay. JAMA. 2009;302:2671-2678.

Unit-Based Rounding: A Holy Grail?

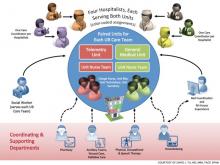

The adult inpatient medicine service at Presbyterian Medical Group (PMG) in Albuquerque, N.M, has been utilizing a unit-based care model (UBCM) with multidisciplinary rounding for the past two years. Due to the positive results, what initially started on two medicine floors telemetry and non-telemetry quickly spread to all of the medicine floors. With implementation of Unit Base 4 in April, all of the medicine beds at Presbyterian will be run using a UBCM.

Set within an inner-city hospital, the medicine service is one of the largest single-site HM programs in the country. The group has 46 FTE requirements and performed more than 15,000 admissions and consults in 2011.

Background

In early 2010, however, the HM service was in crisis. Daily starting census on a typical rounding team was 18 to 20 patients per day, and the average length of stay (LOS) for the group was close to five days. Morale among the hospitalists was low, mainly due to the patient load and multiple throughput issues. Simply stated, the program was at a tipping point.

It was at this time that a Lean Six Sigma Project was initiated to examine the throughput issues. This project expanded rapidly, with input from physicians, nurses, care coordinators, and ancillary staff, and eventually morphed into the UBCM.

The original UBCM premise was to have four geographically isolated hospitalists staff a telemetry floor, and four unit-based hospitalists staff a non-telemetry floor. The isolation guaranteed a lower starting average census for the rounding hospitalists. Each hospitalist on the UBCM would be assigned one specific care coordinator. The multidisciplinary round then occurred at the whiteboard with the hospitalists, nurses, care coordinators, and ancillary staff. The whiteboard had the floor’s census and pertinent care coordination information. The UBCM utilized several tools: visual management (white board), dedicated workspace for the hospitalist team members, standardization of work for team members, and self-regulating governance.