User login

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Physician Assistants Key to HM Group Solutions

Click here to listen to Dr. Johns

Click here to listen to Dr. Johns

Click here to listen to Dr. Johns

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: A neurohospitalist fellowship program director talks about the rise of the neurohospitalist model.

Click here to listen to Dr. Barrett

Click here to listen to Dr. Barrett

Click here to listen to Dr. Barrett

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Telestroke Expands its Reach

In 2009, 338-bed South Fulton Medical Center in Atlanta offered only limited inpatient neurological services. Then along came telemedicine. A plan developed by Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, in conjunction with Atlanta-based Eagle Hospital Physicians, supplied the medical center with on-call teleneurologists working in concert with the HM program, under Dr. Godamunne’s direction.

In the first full year of the program, the medical center increased its volume of stroke patients by 80%. The successful integration of telemedicine and hospital medicine, in conjunction with neurology and nursing, has become a template for a soon-to-be-launched partnership with a hospital in Tennessee.

“So it’s really a multidisciplinary, systemized approach to stroke care,” Dr. Godamunne says.

Some telemedicine programs use remote-controlled robots, such as InTouch Health’s RP-7, that can be driven to the bedside of a patient with a suspected stroke. Mary E. Jensen, MD, professor of radiology and neurosurgery at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, says impressive gains in imaging may be making even that futuristic-seeming technique obsolete. Telemedicine already is using more portable monitors—and in the near future, perhaps, iPads—as visual conduits. A linked system that delivers high-resolution CT and MRI scan results can help Dr. Jensen and stroke neurologists look for hemorrhaging or a large evolving infarction in patients at 25-bed Bath Community Hospital, a two-hour drive to the other side of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains.

After confirming the absence of both complications, a stroke neurologist can give the all-clear for delivery of IV tPA, while Dr. Jensen can determine whether a patient is a candidate for interarterial tPA or mechanical extraction of the clot. And for cases that require it, secure “cloud-based” applications that use the power of the Internet can let multiple providers have a virtual meeting and reach a joint decision about patient care without leaving behind sensitive data that could be fodder for misuse.

“The technology, it’s just developing at such an incredible speed. And I find that very exciting,” Dr. Jensen says.

As the telestroke concept expands, medical centers are departing from the typical hub-and-spoke model in which a large central institution provides services for a ring of rural or underserved areas. Kevin Barrett, MD, MSc, assistant professor of neurology and stroke telemedicine director at the 214-bed Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., says the clinic’s partnership with 201-bed Parrish Medical Center in Titusville, Fla., about 130 miles to the south, is with a facility that’s nearly the same size.

“Because of local neurologists not being enthusiastic about covering emergency cases, telemedicine is now expanding into larger centers where there’s a shortage of inpatient neurology coverage,” Dr. Barrett explains.

Local hospitalists are central to the model’s success, he says, because most of the ischemic stroke patients aren’t falling under the traditional “drip and ship” method, in which they’re treated remotely, then transferred to tertiary-care centers with neurological expertise. The telemedicine-aided ability to manage more patients locally, Dr. Barrett says, is ultimately better for them, their families, and the hospital.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

In 2009, 338-bed South Fulton Medical Center in Atlanta offered only limited inpatient neurological services. Then along came telemedicine. A plan developed by Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, in conjunction with Atlanta-based Eagle Hospital Physicians, supplied the medical center with on-call teleneurologists working in concert with the HM program, under Dr. Godamunne’s direction.

In the first full year of the program, the medical center increased its volume of stroke patients by 80%. The successful integration of telemedicine and hospital medicine, in conjunction with neurology and nursing, has become a template for a soon-to-be-launched partnership with a hospital in Tennessee.

“So it’s really a multidisciplinary, systemized approach to stroke care,” Dr. Godamunne says.

Some telemedicine programs use remote-controlled robots, such as InTouch Health’s RP-7, that can be driven to the bedside of a patient with a suspected stroke. Mary E. Jensen, MD, professor of radiology and neurosurgery at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, says impressive gains in imaging may be making even that futuristic-seeming technique obsolete. Telemedicine already is using more portable monitors—and in the near future, perhaps, iPads—as visual conduits. A linked system that delivers high-resolution CT and MRI scan results can help Dr. Jensen and stroke neurologists look for hemorrhaging or a large evolving infarction in patients at 25-bed Bath Community Hospital, a two-hour drive to the other side of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains.

After confirming the absence of both complications, a stroke neurologist can give the all-clear for delivery of IV tPA, while Dr. Jensen can determine whether a patient is a candidate for interarterial tPA or mechanical extraction of the clot. And for cases that require it, secure “cloud-based” applications that use the power of the Internet can let multiple providers have a virtual meeting and reach a joint decision about patient care without leaving behind sensitive data that could be fodder for misuse.

“The technology, it’s just developing at such an incredible speed. And I find that very exciting,” Dr. Jensen says.

As the telestroke concept expands, medical centers are departing from the typical hub-and-spoke model in which a large central institution provides services for a ring of rural or underserved areas. Kevin Barrett, MD, MSc, assistant professor of neurology and stroke telemedicine director at the 214-bed Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., says the clinic’s partnership with 201-bed Parrish Medical Center in Titusville, Fla., about 130 miles to the south, is with a facility that’s nearly the same size.

“Because of local neurologists not being enthusiastic about covering emergency cases, telemedicine is now expanding into larger centers where there’s a shortage of inpatient neurology coverage,” Dr. Barrett explains.

Local hospitalists are central to the model’s success, he says, because most of the ischemic stroke patients aren’t falling under the traditional “drip and ship” method, in which they’re treated remotely, then transferred to tertiary-care centers with neurological expertise. The telemedicine-aided ability to manage more patients locally, Dr. Barrett says, is ultimately better for them, their families, and the hospital.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

In 2009, 338-bed South Fulton Medical Center in Atlanta offered only limited inpatient neurological services. Then along came telemedicine. A plan developed by Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, in conjunction with Atlanta-based Eagle Hospital Physicians, supplied the medical center with on-call teleneurologists working in concert with the HM program, under Dr. Godamunne’s direction.

In the first full year of the program, the medical center increased its volume of stroke patients by 80%. The successful integration of telemedicine and hospital medicine, in conjunction with neurology and nursing, has become a template for a soon-to-be-launched partnership with a hospital in Tennessee.

“So it’s really a multidisciplinary, systemized approach to stroke care,” Dr. Godamunne says.

Some telemedicine programs use remote-controlled robots, such as InTouch Health’s RP-7, that can be driven to the bedside of a patient with a suspected stroke. Mary E. Jensen, MD, professor of radiology and neurosurgery at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, says impressive gains in imaging may be making even that futuristic-seeming technique obsolete. Telemedicine already is using more portable monitors—and in the near future, perhaps, iPads—as visual conduits. A linked system that delivers high-resolution CT and MRI scan results can help Dr. Jensen and stroke neurologists look for hemorrhaging or a large evolving infarction in patients at 25-bed Bath Community Hospital, a two-hour drive to the other side of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains.

After confirming the absence of both complications, a stroke neurologist can give the all-clear for delivery of IV tPA, while Dr. Jensen can determine whether a patient is a candidate for interarterial tPA or mechanical extraction of the clot. And for cases that require it, secure “cloud-based” applications that use the power of the Internet can let multiple providers have a virtual meeting and reach a joint decision about patient care without leaving behind sensitive data that could be fodder for misuse.

“The technology, it’s just developing at such an incredible speed. And I find that very exciting,” Dr. Jensen says.

As the telestroke concept expands, medical centers are departing from the typical hub-and-spoke model in which a large central institution provides services for a ring of rural or underserved areas. Kevin Barrett, MD, MSc, assistant professor of neurology and stroke telemedicine director at the 214-bed Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., says the clinic’s partnership with 201-bed Parrish Medical Center in Titusville, Fla., about 130 miles to the south, is with a facility that’s nearly the same size.

“Because of local neurologists not being enthusiastic about covering emergency cases, telemedicine is now expanding into larger centers where there’s a shortage of inpatient neurology coverage,” Dr. Barrett explains.

Local hospitalists are central to the model’s success, he says, because most of the ischemic stroke patients aren’t falling under the traditional “drip and ship” method, in which they’re treated remotely, then transferred to tertiary-care centers with neurological expertise. The telemedicine-aided ability to manage more patients locally, Dr. Barrett says, is ultimately better for them, their families, and the hospital.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

Reconciliation Act

Pharmacist Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, got the chance to personally test her ability to help ED providers with medication reconciliation—known by most in healthcare as “med rec”—when she broke her leg a couple of years ago. No problem, she thought: “I’ve been involved in med-rec efforts for eight-plus years.”

But when asked to provide her current medications, Gleason, who is the clinical quality leader in the department of clinical quality and analytics at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, says she was in pain and overwhelmed. “I couldn’t even remember my children’s names, let alone the names and dosages of my aspirin and my thyroid medication,” she says. Moreover, she didn’t carry a list in her wallet because “I’m a pharmacist and I do med rec,” she says.

Gleason’s experience highlights why, six years after The Joint Commission introduced medication reconciliation as National Patient Safety Goal (NPSG) No. 8, hospitals and providers still struggle with the process.1 As a younger patient, Gleason took few medications. But for the majority of elderly inpatients with comorbid conditions, just establishing the patient’s medication list can bring the whole process to a halt; without that foundational list, reconciling other medications becomes problematic.

Although the commission has taken the goals under review and has, since July 1, required compliance with the revised NPSG 03.06.01 (see “Additional Resources,”), hospitalization-associated adverse drug events continue to mount. A recent Canadian study caused a ripple this summer with its findings that patients discharged from acute-care hospitals were at higher risk for unintentional discontinuation of their medications prescribed for chronic diseases than control groups, and those who had an ICU stay are at even higher risk.2

There’s been no shortage of med-rec initiatives in recent years. Medication reconciliation was at the top of the list for ways to prevent errors when the Institute for Healthcare Improvement launched its “5 Million Lives Campaign” in December 2006. SHM weighed in on the issue in 2010 with a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps in med rec.3

“This isn’t a new problem,” Gleason says. “Med rec has become more heightened because we have many more medications and complex therapies, more care providers, more specialists—more players, if you will.”

The March launch of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, part of the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services’ (CMS) Inpatient Prospective Payment System, will again shine the spotlight on med rec’s role in the prevention of 30-day readmissions. The Hospitalist talked with researchers, pharmacists, and hospitalists about the reasons behind medication discrepancies, and their strategies for addressing mismatches.

Why So Difficult?

The goal of medication reconciliation is to generate and maintain an accurate and coherent record of patients’ medications across all transitions of care, which sounds straightforward enough. But the process involves much more than just checking items off a list, says Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, currently the principal investigator for the $1.5 million study funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to research and implement best practices in med rec, dubbed MARQUIS (Multicenter Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study). Those immersed in med rec know that it’s nonlinear, multilayered, and surprisingly complex, requiring partnerships among diverse providers across many domains of care.

“Medication reconciliation gets right at all the weaknesses of our healthcare system,” says Dr. Schnipper, a hospitalist and director of clinical research for the HM service at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “We have an excellent healthcare system in so many ways, but what we do not do such a good job of is coordination of care across settings, easy transfer of information, and having one person who is responsible for the accuracy of a patient’s health information.”

Dr. Schnipper’s studies attest to the common occurrence of unintentional medical discrepancies, pointing to the need for accurate medication histories, identifying high-risk patients for intensive interventions, and careful med rec at time of discharge.4

Other factors might come into play, says Ted Tsomides, MD, PhD, an attending physician on the HM service at WakeMed Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina’s School of Medicine in Raleigh, N.C. For example, he surmises that a “fatigue factor” sets in for some providers. “After five years of working on any initiative, people get worn out and push it to the back burner, unless they are really incentivized to stay on it,” he says.

List Capture

Medication reconciliation is a multifaceted process, and the first step is to gather the history of medications the patient has been taking. Hospitalist Blake J. Lesselroth, MD, MBI, assistant professor of medicine and medical informatics and director of the Portland Patient Safety Center of Inquiry at the Portland VA Medical Center in Oregon, points out that “the initial exposure to the patient is like a pencil sketch. You start to realize that med rec involves iterative loops of communication between you, the patient, and other knowledge resources (see Figure 1). As you start to pull in more information, you begin to complete your narrative. At the end of hospitalization, you’ve got a vibrant portrait with much more nuance to it. So it can’t be a linear process.”

—Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, clinical quality leader, department of clinical quality and analytics, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

The list is dynamic, especially in the ICU setting, says Gleason, where it represents only one point in time.

In a closed system, such as the Veterans Administration or Kaiser Permanente, it’s often easier to establish a patient’s ongoing medications. With an integrated electronic health record (EHR), providers can call up the patient’s list of medications during admittance to the hospital. Verifying those medications remains critical: The health record lists patients’ prescriptions, but that doesn’t always mean they have actually filled or are taking those medications.

At the Kaiser Permanente Southern California site in Santa Clarita, Calif., where hospitalist David W. Wong, MD, works, pharmacists review their medications with patients when they are admitted, provide any needed consultation, then repeat the process at discharge. “So far,” Dr. Wong says, “this has resulted in the best medication reconciliation that we’ve seen.”

Pharmacy Is Key

In 2006, Kenneth Boockvar, MD, of the James J. Peters VA Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y., found in a pre- and post-intervention study that using pharmacists to ferret out and communicate prescribing discrepancies to physicians resulted in lower risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) for patients transferred between the hospital and the nursing home.5 Likewise, Dr. Schnipper and his colleagues found that using pharmacists to conduct medication reviews, counsel patients at discharge, and make follow-up telephone calls to patients was associated with a lower rate of preventable ADEs 30 days after hospital discharge.6

At United Hospital System’s (UHS) Kenosha Medical Center campus in Kenosha, Wis., pharmacists play a key role in generating medication lists for incoming patients. Hospitalist Corey Black, MD, regional medical director for Cogent HMG, says many patients do not recall their medications or the dosages, so UHS utilizes a team approach: If patients come in during evenings or weekends, pharmacists start calling local pharmacies to track down patients’ medication lists. “We also try to have family members bring in any medication containers they can find,” he adds. Due to a Wisconsin state law mandating nursing homes to send medication lists along with patients, generating a list is much easier.

Dr. Tsomides is a physician sponsor of a new med-rec initiative at WakeMed. With a steering committee that includes representatives from stakeholder services (medicine, nursing, pharmacy, administration, etc.), the group plans to hire and train pharmacy techs who will take home medication lists in the ED, lifting that responsibility from physicians’ task lists.

Is IT the Answer?

Would many of the barriers to med rec go away with universal EHR? So far, the literature has not borne out the superiority of using EHR to facilitate better med rec.

Peter Kaboli and colleagues found that the computerized medication record reflected what patients were actually taking for only 5.3% of the 493 VA patients enrolled in a study at the Iowa City VA.7 Kenneth Boockvar and colleagues at the Bronx VA found no difference in the overall incidence of ADEs caused by medication discrepancies between VA patients with an EHR and non-VA patients without an EHR.8 A group of researchers with Partners HealthCare in Boston evaluated a secure, Web-based patient portal to produce more accurate medication lists. The patients using this system had just as many discrepancies between medication lists and self-reporting as those who did not.9

Dr. Lesselroth, who has devised a patient kiosk touch-screen tool for reconciling patients’ medication lists and has faced barriers when implementing said technology, says med rec is much more “organic” than strictly mechanical. “It invokes theories of learning from the cognitive sciences,” he says. “We haven’t actually built tools that help people with their problem representation, with understanding not just how medications reconcile with the prior setting of care, but whether they make clinical sense within the new context of care. That requires a quantum leap in thinking.”

Re-Brand the Message

Drs. Schnipper and Tsomides believe that when The Joint Committee first coined the term “medication reconciliation” and advanced it as a mandate, most providers associated it with a regulatory requirement, and understandably so. Dr. Schnipper says med rec could be improved if providers think about it in the context of accurate orders that translate to greater patient safety. “After all,” he says, “hospitalists are ultimately responsible for the medication orders written for their patients.

“This is not about regulatory requirements,” he continues. “This is about medication safety and transitions of care. You can spend an hour on deciding what dose of Lasix you want to send this patient home on, but if the patient then takes the wrong dose of Lasix because they don’t know what they were supposed to be taking, then all that good medical care is undone.”

The med rec conversation has come full circle, then, as being truly an issue of delivering patient-centered care. (For more on this topic, visit the-hospitalist.org to read “Patient Engagement Critical.”) Rather than focusing on the sometimes-befuddling term of medication reconciliation, providers should see med rec as part of an integrated medication management process that aims to take better care of patients through prevention and treatment, Gleason says.

The med rec issue is about effective communication at every transition of care. And that’s why, says Dr. Schnipper, “Hospitalists should own this process. We don’t have to do the process entirely by ourselves—and shouldn’t. But we are responsible for errors that happen during transitions in care and we should own these initiatives.”

He notes that all six hospitals enrolled in the MARQUIS study have hospitalists at the forefront of their quality-improvement (QI) efforts.

“Medication reconciliation is potentially a high-risk process, and there are no silver bullets” for globally addressing the process, says Dorothea Wild, MD, chief hospitalist at Griffin Hospital, a 160-bed acute care hospital in Derby, Conn.

—Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, hospitalist and director of clinical research, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Hospitalist Service, assistant professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston

Dr. Wild draws a parallel between med rec and blood transfusions. Just as with correct transfusing procedures, “we envision a process where at least two people independently verify what patients’ medications are,” she says. The meds list is started in the ED by nursing staff, is verified by the ED attending, verified again by the admitting team, and triple-checked by the admitting attending. Thus, says Dr. Wild, med rec becomes a shared responsibility.

Dr. Lesselroth wholeheartedly agrees with the approach.

“This is everybody’s job,” he says. “In a larger world view, med rec is all about trying to find a medication regimen that harmonizes with what the patient can do, that improves their probability of adherence, and that also helps us gather information when the patient returns and we re-embrace them in the care model. Theoretically, then, everybody [interfacing with a patient] becomes a clutch player.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. 2005 Hospital Accreditation Standards. JCO website. Available at: http://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/ JCI-Accredited-Organizations/. Accessed Dec. 7, 2011.

- Bell CM, Brener SS, Gunraj N, et al. Association of ICU or hospital admission with unintentional discontinuation of medications for chronic diseases. JAMA. 2011;306:840-847.

- Greenwald JL, Halasyamani L, Green J, et al. Making inpatient medication patient centered, clinically relevant and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:477-485.

- Pippins JR, Gandhi TK, Hamann C, et al. Classifying and predicting errors of inpatient medication reconciliation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1414-1422.

- Boockvar KS, Carlson HL, Giambanco V, et al. Medication reconciliation for reducing drug-discrepancy adverse events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:236-243.

- Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:565-571.

- Kaboli PJ, McClimon JB, Hoth AB, et al. Assessing the accuracy of computerized medication histories. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 2):872-877.

- Boockvar KS, Livote EE, Goldstein N, et al. Electronic health records and adverse drug events after patient transfer. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;5:Epub(Aug 19).

- Staroselsky M, Volk LA, Tsurikova R, et al. An effort to improve electronic health record medication list accuracy between visits: patients’ and physicians’ responses. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:153-160.

- Gleason KM, McDaniel MR, Feinglass J, et al. Results of the Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) study: an analysis of medication reconciliation errors and risk factors at hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:441-447.

Pharmacist Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, got the chance to personally test her ability to help ED providers with medication reconciliation—known by most in healthcare as “med rec”—when she broke her leg a couple of years ago. No problem, she thought: “I’ve been involved in med-rec efforts for eight-plus years.”

But when asked to provide her current medications, Gleason, who is the clinical quality leader in the department of clinical quality and analytics at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, says she was in pain and overwhelmed. “I couldn’t even remember my children’s names, let alone the names and dosages of my aspirin and my thyroid medication,” she says. Moreover, she didn’t carry a list in her wallet because “I’m a pharmacist and I do med rec,” she says.

Gleason’s experience highlights why, six years after The Joint Commission introduced medication reconciliation as National Patient Safety Goal (NPSG) No. 8, hospitals and providers still struggle with the process.1 As a younger patient, Gleason took few medications. But for the majority of elderly inpatients with comorbid conditions, just establishing the patient’s medication list can bring the whole process to a halt; without that foundational list, reconciling other medications becomes problematic.

Although the commission has taken the goals under review and has, since July 1, required compliance with the revised NPSG 03.06.01 (see “Additional Resources,”), hospitalization-associated adverse drug events continue to mount. A recent Canadian study caused a ripple this summer with its findings that patients discharged from acute-care hospitals were at higher risk for unintentional discontinuation of their medications prescribed for chronic diseases than control groups, and those who had an ICU stay are at even higher risk.2

There’s been no shortage of med-rec initiatives in recent years. Medication reconciliation was at the top of the list for ways to prevent errors when the Institute for Healthcare Improvement launched its “5 Million Lives Campaign” in December 2006. SHM weighed in on the issue in 2010 with a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps in med rec.3

“This isn’t a new problem,” Gleason says. “Med rec has become more heightened because we have many more medications and complex therapies, more care providers, more specialists—more players, if you will.”

The March launch of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, part of the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services’ (CMS) Inpatient Prospective Payment System, will again shine the spotlight on med rec’s role in the prevention of 30-day readmissions. The Hospitalist talked with researchers, pharmacists, and hospitalists about the reasons behind medication discrepancies, and their strategies for addressing mismatches.

Why So Difficult?

The goal of medication reconciliation is to generate and maintain an accurate and coherent record of patients’ medications across all transitions of care, which sounds straightforward enough. But the process involves much more than just checking items off a list, says Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, currently the principal investigator for the $1.5 million study funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to research and implement best practices in med rec, dubbed MARQUIS (Multicenter Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study). Those immersed in med rec know that it’s nonlinear, multilayered, and surprisingly complex, requiring partnerships among diverse providers across many domains of care.

“Medication reconciliation gets right at all the weaknesses of our healthcare system,” says Dr. Schnipper, a hospitalist and director of clinical research for the HM service at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “We have an excellent healthcare system in so many ways, but what we do not do such a good job of is coordination of care across settings, easy transfer of information, and having one person who is responsible for the accuracy of a patient’s health information.”

Dr. Schnipper’s studies attest to the common occurrence of unintentional medical discrepancies, pointing to the need for accurate medication histories, identifying high-risk patients for intensive interventions, and careful med rec at time of discharge.4

Other factors might come into play, says Ted Tsomides, MD, PhD, an attending physician on the HM service at WakeMed Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina’s School of Medicine in Raleigh, N.C. For example, he surmises that a “fatigue factor” sets in for some providers. “After five years of working on any initiative, people get worn out and push it to the back burner, unless they are really incentivized to stay on it,” he says.

List Capture

Medication reconciliation is a multifaceted process, and the first step is to gather the history of medications the patient has been taking. Hospitalist Blake J. Lesselroth, MD, MBI, assistant professor of medicine and medical informatics and director of the Portland Patient Safety Center of Inquiry at the Portland VA Medical Center in Oregon, points out that “the initial exposure to the patient is like a pencil sketch. You start to realize that med rec involves iterative loops of communication between you, the patient, and other knowledge resources (see Figure 1). As you start to pull in more information, you begin to complete your narrative. At the end of hospitalization, you’ve got a vibrant portrait with much more nuance to it. So it can’t be a linear process.”

—Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, clinical quality leader, department of clinical quality and analytics, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

The list is dynamic, especially in the ICU setting, says Gleason, where it represents only one point in time.

In a closed system, such as the Veterans Administration or Kaiser Permanente, it’s often easier to establish a patient’s ongoing medications. With an integrated electronic health record (EHR), providers can call up the patient’s list of medications during admittance to the hospital. Verifying those medications remains critical: The health record lists patients’ prescriptions, but that doesn’t always mean they have actually filled or are taking those medications.

At the Kaiser Permanente Southern California site in Santa Clarita, Calif., where hospitalist David W. Wong, MD, works, pharmacists review their medications with patients when they are admitted, provide any needed consultation, then repeat the process at discharge. “So far,” Dr. Wong says, “this has resulted in the best medication reconciliation that we’ve seen.”

Pharmacy Is Key

In 2006, Kenneth Boockvar, MD, of the James J. Peters VA Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y., found in a pre- and post-intervention study that using pharmacists to ferret out and communicate prescribing discrepancies to physicians resulted in lower risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) for patients transferred between the hospital and the nursing home.5 Likewise, Dr. Schnipper and his colleagues found that using pharmacists to conduct medication reviews, counsel patients at discharge, and make follow-up telephone calls to patients was associated with a lower rate of preventable ADEs 30 days after hospital discharge.6

At United Hospital System’s (UHS) Kenosha Medical Center campus in Kenosha, Wis., pharmacists play a key role in generating medication lists for incoming patients. Hospitalist Corey Black, MD, regional medical director for Cogent HMG, says many patients do not recall their medications or the dosages, so UHS utilizes a team approach: If patients come in during evenings or weekends, pharmacists start calling local pharmacies to track down patients’ medication lists. “We also try to have family members bring in any medication containers they can find,” he adds. Due to a Wisconsin state law mandating nursing homes to send medication lists along with patients, generating a list is much easier.

Dr. Tsomides is a physician sponsor of a new med-rec initiative at WakeMed. With a steering committee that includes representatives from stakeholder services (medicine, nursing, pharmacy, administration, etc.), the group plans to hire and train pharmacy techs who will take home medication lists in the ED, lifting that responsibility from physicians’ task lists.

Is IT the Answer?

Would many of the barriers to med rec go away with universal EHR? So far, the literature has not borne out the superiority of using EHR to facilitate better med rec.

Peter Kaboli and colleagues found that the computerized medication record reflected what patients were actually taking for only 5.3% of the 493 VA patients enrolled in a study at the Iowa City VA.7 Kenneth Boockvar and colleagues at the Bronx VA found no difference in the overall incidence of ADEs caused by medication discrepancies between VA patients with an EHR and non-VA patients without an EHR.8 A group of researchers with Partners HealthCare in Boston evaluated a secure, Web-based patient portal to produce more accurate medication lists. The patients using this system had just as many discrepancies between medication lists and self-reporting as those who did not.9

Dr. Lesselroth, who has devised a patient kiosk touch-screen tool for reconciling patients’ medication lists and has faced barriers when implementing said technology, says med rec is much more “organic” than strictly mechanical. “It invokes theories of learning from the cognitive sciences,” he says. “We haven’t actually built tools that help people with their problem representation, with understanding not just how medications reconcile with the prior setting of care, but whether they make clinical sense within the new context of care. That requires a quantum leap in thinking.”

Re-Brand the Message

Drs. Schnipper and Tsomides believe that when The Joint Committee first coined the term “medication reconciliation” and advanced it as a mandate, most providers associated it with a regulatory requirement, and understandably so. Dr. Schnipper says med rec could be improved if providers think about it in the context of accurate orders that translate to greater patient safety. “After all,” he says, “hospitalists are ultimately responsible for the medication orders written for their patients.

“This is not about regulatory requirements,” he continues. “This is about medication safety and transitions of care. You can spend an hour on deciding what dose of Lasix you want to send this patient home on, but if the patient then takes the wrong dose of Lasix because they don’t know what they were supposed to be taking, then all that good medical care is undone.”

The med rec conversation has come full circle, then, as being truly an issue of delivering patient-centered care. (For more on this topic, visit the-hospitalist.org to read “Patient Engagement Critical.”) Rather than focusing on the sometimes-befuddling term of medication reconciliation, providers should see med rec as part of an integrated medication management process that aims to take better care of patients through prevention and treatment, Gleason says.

The med rec issue is about effective communication at every transition of care. And that’s why, says Dr. Schnipper, “Hospitalists should own this process. We don’t have to do the process entirely by ourselves—and shouldn’t. But we are responsible for errors that happen during transitions in care and we should own these initiatives.”

He notes that all six hospitals enrolled in the MARQUIS study have hospitalists at the forefront of their quality-improvement (QI) efforts.

“Medication reconciliation is potentially a high-risk process, and there are no silver bullets” for globally addressing the process, says Dorothea Wild, MD, chief hospitalist at Griffin Hospital, a 160-bed acute care hospital in Derby, Conn.

—Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, hospitalist and director of clinical research, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Hospitalist Service, assistant professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston

Dr. Wild draws a parallel between med rec and blood transfusions. Just as with correct transfusing procedures, “we envision a process where at least two people independently verify what patients’ medications are,” she says. The meds list is started in the ED by nursing staff, is verified by the ED attending, verified again by the admitting team, and triple-checked by the admitting attending. Thus, says Dr. Wild, med rec becomes a shared responsibility.

Dr. Lesselroth wholeheartedly agrees with the approach.

“This is everybody’s job,” he says. “In a larger world view, med rec is all about trying to find a medication regimen that harmonizes with what the patient can do, that improves their probability of adherence, and that also helps us gather information when the patient returns and we re-embrace them in the care model. Theoretically, then, everybody [interfacing with a patient] becomes a clutch player.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. 2005 Hospital Accreditation Standards. JCO website. Available at: http://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/ JCI-Accredited-Organizations/. Accessed Dec. 7, 2011.

- Bell CM, Brener SS, Gunraj N, et al. Association of ICU or hospital admission with unintentional discontinuation of medications for chronic diseases. JAMA. 2011;306:840-847.

- Greenwald JL, Halasyamani L, Green J, et al. Making inpatient medication patient centered, clinically relevant and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:477-485.

- Pippins JR, Gandhi TK, Hamann C, et al. Classifying and predicting errors of inpatient medication reconciliation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1414-1422.

- Boockvar KS, Carlson HL, Giambanco V, et al. Medication reconciliation for reducing drug-discrepancy adverse events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:236-243.

- Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:565-571.

- Kaboli PJ, McClimon JB, Hoth AB, et al. Assessing the accuracy of computerized medication histories. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 2):872-877.

- Boockvar KS, Livote EE, Goldstein N, et al. Electronic health records and adverse drug events after patient transfer. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;5:Epub(Aug 19).

- Staroselsky M, Volk LA, Tsurikova R, et al. An effort to improve electronic health record medication list accuracy between visits: patients’ and physicians’ responses. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:153-160.

- Gleason KM, McDaniel MR, Feinglass J, et al. Results of the Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) study: an analysis of medication reconciliation errors and risk factors at hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:441-447.

Pharmacist Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, got the chance to personally test her ability to help ED providers with medication reconciliation—known by most in healthcare as “med rec”—when she broke her leg a couple of years ago. No problem, she thought: “I’ve been involved in med-rec efforts for eight-plus years.”

But when asked to provide her current medications, Gleason, who is the clinical quality leader in the department of clinical quality and analytics at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, says she was in pain and overwhelmed. “I couldn’t even remember my children’s names, let alone the names and dosages of my aspirin and my thyroid medication,” she says. Moreover, she didn’t carry a list in her wallet because “I’m a pharmacist and I do med rec,” she says.

Gleason’s experience highlights why, six years after The Joint Commission introduced medication reconciliation as National Patient Safety Goal (NPSG) No. 8, hospitals and providers still struggle with the process.1 As a younger patient, Gleason took few medications. But for the majority of elderly inpatients with comorbid conditions, just establishing the patient’s medication list can bring the whole process to a halt; without that foundational list, reconciling other medications becomes problematic.

Although the commission has taken the goals under review and has, since July 1, required compliance with the revised NPSG 03.06.01 (see “Additional Resources,”), hospitalization-associated adverse drug events continue to mount. A recent Canadian study caused a ripple this summer with its findings that patients discharged from acute-care hospitals were at higher risk for unintentional discontinuation of their medications prescribed for chronic diseases than control groups, and those who had an ICU stay are at even higher risk.2

There’s been no shortage of med-rec initiatives in recent years. Medication reconciliation was at the top of the list for ways to prevent errors when the Institute for Healthcare Improvement launched its “5 Million Lives Campaign” in December 2006. SHM weighed in on the issue in 2010 with a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps in med rec.3

“This isn’t a new problem,” Gleason says. “Med rec has become more heightened because we have many more medications and complex therapies, more care providers, more specialists—more players, if you will.”

The March launch of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, part of the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services’ (CMS) Inpatient Prospective Payment System, will again shine the spotlight on med rec’s role in the prevention of 30-day readmissions. The Hospitalist talked with researchers, pharmacists, and hospitalists about the reasons behind medication discrepancies, and their strategies for addressing mismatches.

Why So Difficult?

The goal of medication reconciliation is to generate and maintain an accurate and coherent record of patients’ medications across all transitions of care, which sounds straightforward enough. But the process involves much more than just checking items off a list, says Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, currently the principal investigator for the $1.5 million study funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to research and implement best practices in med rec, dubbed MARQUIS (Multicenter Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study). Those immersed in med rec know that it’s nonlinear, multilayered, and surprisingly complex, requiring partnerships among diverse providers across many domains of care.

“Medication reconciliation gets right at all the weaknesses of our healthcare system,” says Dr. Schnipper, a hospitalist and director of clinical research for the HM service at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “We have an excellent healthcare system in so many ways, but what we do not do such a good job of is coordination of care across settings, easy transfer of information, and having one person who is responsible for the accuracy of a patient’s health information.”

Dr. Schnipper’s studies attest to the common occurrence of unintentional medical discrepancies, pointing to the need for accurate medication histories, identifying high-risk patients for intensive interventions, and careful med rec at time of discharge.4

Other factors might come into play, says Ted Tsomides, MD, PhD, an attending physician on the HM service at WakeMed Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina’s School of Medicine in Raleigh, N.C. For example, he surmises that a “fatigue factor” sets in for some providers. “After five years of working on any initiative, people get worn out and push it to the back burner, unless they are really incentivized to stay on it,” he says.

List Capture

Medication reconciliation is a multifaceted process, and the first step is to gather the history of medications the patient has been taking. Hospitalist Blake J. Lesselroth, MD, MBI, assistant professor of medicine and medical informatics and director of the Portland Patient Safety Center of Inquiry at the Portland VA Medical Center in Oregon, points out that “the initial exposure to the patient is like a pencil sketch. You start to realize that med rec involves iterative loops of communication between you, the patient, and other knowledge resources (see Figure 1). As you start to pull in more information, you begin to complete your narrative. At the end of hospitalization, you’ve got a vibrant portrait with much more nuance to it. So it can’t be a linear process.”

—Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, clinical quality leader, department of clinical quality and analytics, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

The list is dynamic, especially in the ICU setting, says Gleason, where it represents only one point in time.

In a closed system, such as the Veterans Administration or Kaiser Permanente, it’s often easier to establish a patient’s ongoing medications. With an integrated electronic health record (EHR), providers can call up the patient’s list of medications during admittance to the hospital. Verifying those medications remains critical: The health record lists patients’ prescriptions, but that doesn’t always mean they have actually filled or are taking those medications.

At the Kaiser Permanente Southern California site in Santa Clarita, Calif., where hospitalist David W. Wong, MD, works, pharmacists review their medications with patients when they are admitted, provide any needed consultation, then repeat the process at discharge. “So far,” Dr. Wong says, “this has resulted in the best medication reconciliation that we’ve seen.”

Pharmacy Is Key

In 2006, Kenneth Boockvar, MD, of the James J. Peters VA Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y., found in a pre- and post-intervention study that using pharmacists to ferret out and communicate prescribing discrepancies to physicians resulted in lower risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) for patients transferred between the hospital and the nursing home.5 Likewise, Dr. Schnipper and his colleagues found that using pharmacists to conduct medication reviews, counsel patients at discharge, and make follow-up telephone calls to patients was associated with a lower rate of preventable ADEs 30 days after hospital discharge.6

At United Hospital System’s (UHS) Kenosha Medical Center campus in Kenosha, Wis., pharmacists play a key role in generating medication lists for incoming patients. Hospitalist Corey Black, MD, regional medical director for Cogent HMG, says many patients do not recall their medications or the dosages, so UHS utilizes a team approach: If patients come in during evenings or weekends, pharmacists start calling local pharmacies to track down patients’ medication lists. “We also try to have family members bring in any medication containers they can find,” he adds. Due to a Wisconsin state law mandating nursing homes to send medication lists along with patients, generating a list is much easier.

Dr. Tsomides is a physician sponsor of a new med-rec initiative at WakeMed. With a steering committee that includes representatives from stakeholder services (medicine, nursing, pharmacy, administration, etc.), the group plans to hire and train pharmacy techs who will take home medication lists in the ED, lifting that responsibility from physicians’ task lists.

Is IT the Answer?

Would many of the barriers to med rec go away with universal EHR? So far, the literature has not borne out the superiority of using EHR to facilitate better med rec.

Peter Kaboli and colleagues found that the computerized medication record reflected what patients were actually taking for only 5.3% of the 493 VA patients enrolled in a study at the Iowa City VA.7 Kenneth Boockvar and colleagues at the Bronx VA found no difference in the overall incidence of ADEs caused by medication discrepancies between VA patients with an EHR and non-VA patients without an EHR.8 A group of researchers with Partners HealthCare in Boston evaluated a secure, Web-based patient portal to produce more accurate medication lists. The patients using this system had just as many discrepancies between medication lists and self-reporting as those who did not.9

Dr. Lesselroth, who has devised a patient kiosk touch-screen tool for reconciling patients’ medication lists and has faced barriers when implementing said technology, says med rec is much more “organic” than strictly mechanical. “It invokes theories of learning from the cognitive sciences,” he says. “We haven’t actually built tools that help people with their problem representation, with understanding not just how medications reconcile with the prior setting of care, but whether they make clinical sense within the new context of care. That requires a quantum leap in thinking.”

Re-Brand the Message

Drs. Schnipper and Tsomides believe that when The Joint Committee first coined the term “medication reconciliation” and advanced it as a mandate, most providers associated it with a regulatory requirement, and understandably so. Dr. Schnipper says med rec could be improved if providers think about it in the context of accurate orders that translate to greater patient safety. “After all,” he says, “hospitalists are ultimately responsible for the medication orders written for their patients.

“This is not about regulatory requirements,” he continues. “This is about medication safety and transitions of care. You can spend an hour on deciding what dose of Lasix you want to send this patient home on, but if the patient then takes the wrong dose of Lasix because they don’t know what they were supposed to be taking, then all that good medical care is undone.”

The med rec conversation has come full circle, then, as being truly an issue of delivering patient-centered care. (For more on this topic, visit the-hospitalist.org to read “Patient Engagement Critical.”) Rather than focusing on the sometimes-befuddling term of medication reconciliation, providers should see med rec as part of an integrated medication management process that aims to take better care of patients through prevention and treatment, Gleason says.

The med rec issue is about effective communication at every transition of care. And that’s why, says Dr. Schnipper, “Hospitalists should own this process. We don’t have to do the process entirely by ourselves—and shouldn’t. But we are responsible for errors that happen during transitions in care and we should own these initiatives.”

He notes that all six hospitals enrolled in the MARQUIS study have hospitalists at the forefront of their quality-improvement (QI) efforts.

“Medication reconciliation is potentially a high-risk process, and there are no silver bullets” for globally addressing the process, says Dorothea Wild, MD, chief hospitalist at Griffin Hospital, a 160-bed acute care hospital in Derby, Conn.

—Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, hospitalist and director of clinical research, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Hospitalist Service, assistant professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston

Dr. Wild draws a parallel between med rec and blood transfusions. Just as with correct transfusing procedures, “we envision a process where at least two people independently verify what patients’ medications are,” she says. The meds list is started in the ED by nursing staff, is verified by the ED attending, verified again by the admitting team, and triple-checked by the admitting attending. Thus, says Dr. Wild, med rec becomes a shared responsibility.

Dr. Lesselroth wholeheartedly agrees with the approach.

“This is everybody’s job,” he says. “In a larger world view, med rec is all about trying to find a medication regimen that harmonizes with what the patient can do, that improves their probability of adherence, and that also helps us gather information when the patient returns and we re-embrace them in the care model. Theoretically, then, everybody [interfacing with a patient] becomes a clutch player.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. 2005 Hospital Accreditation Standards. JCO website. Available at: http://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/ JCI-Accredited-Organizations/. Accessed Dec. 7, 2011.

- Bell CM, Brener SS, Gunraj N, et al. Association of ICU or hospital admission with unintentional discontinuation of medications for chronic diseases. JAMA. 2011;306:840-847.

- Greenwald JL, Halasyamani L, Green J, et al. Making inpatient medication patient centered, clinically relevant and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:477-485.

- Pippins JR, Gandhi TK, Hamann C, et al. Classifying and predicting errors of inpatient medication reconciliation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1414-1422.

- Boockvar KS, Carlson HL, Giambanco V, et al. Medication reconciliation for reducing drug-discrepancy adverse events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:236-243.

- Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:565-571.

- Kaboli PJ, McClimon JB, Hoth AB, et al. Assessing the accuracy of computerized medication histories. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 2):872-877.

- Boockvar KS, Livote EE, Goldstein N, et al. Electronic health records and adverse drug events after patient transfer. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;5:Epub(Aug 19).

- Staroselsky M, Volk LA, Tsurikova R, et al. An effort to improve electronic health record medication list accuracy between visits: patients’ and physicians’ responses. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:153-160.

- Gleason KM, McDaniel MR, Feinglass J, et al. Results of the Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) study: an analysis of medication reconciliation errors and risk factors at hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:441-447.

Is a Post-Discharge Clinic in Your Hospital's Future?

The hospitalist concept was established on the foundation of timely, informative handoffs to primary-care physicians (PCPs) once a patient’s hospital stay is complete. With sicker patients and shorter hospital stays, pending test results, and complex post-discharge medication regimens to sort out, this handoff is crucial to successful discharges. But what if a discharged patient can’t get in to see the PCP, or has no established PCP?

Recent research on hospital readmissions by the Dartmouth Atlas Project found that only 42% of hospitalized Medicare patients had any contact with a primary-care clinician within 14 days of discharge.1 For patients with ongoing medical needs, such missed connections are a major contributor to hospital readmissions, and thus a target for hospitals and HM groups wanting to control their readmission rates before Medicare imposes reimbursement penalties starting in October 2012 (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011, p. 1).

One proposed solution is the post-discharge clinic, typically located on or near a hospital’s campus and staffed by hospitalists, PCPs, or advanced-practice nurses. The patient can be seen once or a few times in the post-discharge clinic to make sure that health education started in the hospital is understood and followed, and that prescriptions ordered in the hospital are being taken on schedule.

—Lauren Doctoroff, MD, hospitalist, director, post-discharge clinic, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, describes hospitalist-led post-discharge clinics as “Band-Aids for an inadequate primary-care system.” What would be better, he says, is focusing on the underlying problem and working to improve post-discharge access to primary care. Dr. Williams acknowledges, however, that sometimes a patch is needed to stanch the blood flow—e.g., to better manage care transitions—while waiting on healthcare reform and medical homes to improve care coordination throughout the system.

Working in a post-discharge clinic might seem like “a stretch for many hospitalists, especially those who chose this field because they didn’t want to do outpatient medicine,” says Lauren Doctoroff, MD, a hospitalist who directs a post-discharge clinic at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. “But there are times when it may be appropriate for hospital-based doctors to extend their responsibility out of the hospital.”

Dr. Doctoroff also says that working in such a clinic can be practice-changing for hospitalists. “All of a sudden, you have a different view of your hospitalized patients, and you start to ask different questions while they’re in the hospital than you ever did before,” she explains.

What is a Post-Discharge Clinic?

The post-discharge clinic, also known as a transitional-care clinic or after-care clinic, is intended to bridge medical coverage between the hospital and primary care. The clinic at BIDMC is for patients affiliated with its Health Care Associates faculty practice “discharged from either our hospital or another hospital, who need care that their PCP or specialist, because of scheduling conflicts, cannot provide within the needed time frame,” Dr. Doctoroff says.

Four hospitalists from BIDMC’s large HM group were selected to staff the clinic. The hospitalists work in one-month rotations (a total of three months on service per year), and are relieved of other responsibilities during their month in clinic. They provide five half-day clinic sessions per week, with a 40-minute-per-patient visit schedule. Thirty minutes are allotted for patients referred from the hospital’s ED who did not get admitted to the hospital but need clinical follow-up.

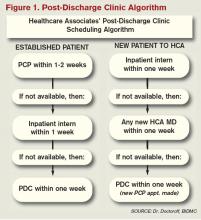

The clinic is based in a BIDMC-affiliated primary-care practice, “which allows us to use its administrative structure and logistical support,” Dr. Doctoroff explains. “A hospital-based administrative service helps set up outpatient visits prior to discharge using computerized physician order entry and a scheduling algorhythm.” (See Figure 1) Patients who can be seen by their PCP in a timely fashion are referred to the PCP office; if not, they are scheduled in the post-discharge clinic. “That helps preserve the PCP relationship, which I think is paramount,” she says.

The first two years were spent getting the clinic established, but in the near future, BIDMC will start measuring such outcomes as access to care and quality. “But not necessarily readmission rates,” Dr. Doctoroff adds. “I know many people think of post-discharge clinics in the context of preventing readmissions, although we don’t have the data yet to fully support that. In fact, some readmissions may result from seeing a doctor. If you get a closer look at some patients after discharge and they are doing badly, they are more likely to be readmitted than if they had just stayed home.” In such cases, readmission could actually be a better outcome for the patient, she notes.

Dr. Doctoroff describes a typical user of her post-discharge clinic as a non-English-speaking patient who was discharged from the hospital with severe back pain from a herniated disk. “He came back to see me 10 days later, still barely able to walk. He hadn’t been able to fill any of the prescriptions from his hospital stay. Within two hours after I saw him, we got his meds filled and outpatient services set up,” she says. “We take care of many patients like him in the hospital with acute pain issues, whom we discharge as soon as they can walk, and later we see them limping into outpatient clinics. It makes me think differently now about how I plan their discharges.”

—Shay Martinez, MD, hospitalist, medical director, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle

Who else needs these clinics? Dr. Doctoroff suggests two ways of looking at the question.

“Even for a simple patient admitted to the hospital, that can represent a significant change in the medical picture—a sort of sentinel event. In the discharge clinic, we give them an opportunity to review the hospitalization and answer their questions,” she says. “A lot of information presented to patients in the hospital is not well heard, and the initial visit may be their first time to really talk about what happened.” For other patients with conditions such as congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or poorly controlled diabetes, treatment guidelines might dictate a pattern for post-discharge follow-up—for example, medical visits in seven or 10 days.

In Seattle, Harborview Medical Center established its After Care Clinic, staffed by hospitalists and nurse practitioners, to provide transitional care for patients discharged from inpatient wards or the ED in need of follow-up, says medical director and hospitalist Shay Martinez, MD. A second priority is to see any CHF patient within 48 hours of discharge.

“We try to limit patients to a maximum of three visits in our clinic,” she says. “At that point, we help them get established in a medical home, either here in one of our primary-care clinics, or in one of the many excellent community clinics in the area.

“This model works well with our patient population. We actually try to do primary care on the inpatient side as well. Our hospitalists are specialized in that approach, given our patient population. We see a lot of immigrants, non-English speakers, people with low health literacy, and the homeless, many of whom lack primary care,” Dr. Martinez says. “We do medication reconciliation, reassessments, and follow-ups with lab tests. We also try to assess who is more likely to be a no-show, and who needs more help with scheduling follow-up appointments.”

Clinical coverage of post-discharge clinics varies by setting, staffing, and scope. If demand is low, hospitalists or ED physicians can be called off the floor to see patients who return to the clinic, or they could staff the clinic after their hospitalist shift ends. Post-discharge clinic staff whose schedules are light can flex into providing primary-care visits in the clinic. Post-discharge can also could be provided in conjunction with—or as an alternative to—physician house calls to patients’ homes. Some post-discharge clinics work with medical call centers or telephonic case managers; some even use telemedicine.

It also could be a growth opportunity for hospitalist practices. “It is an exciting potential role for hospitalists interested in doing a little outpatient care,” Dr. Martinez says. “This is also a good way to be a safety net for your safety-net hospital.”

continued below...

Partner with Community

Tallahassee (Fla.) Memorial Hospital (TMH) in February launched a transitional-care clinic in collaboration with faculty from Florida State University, community-based health providers, and the local Capital Health Plan. Hospitalists don’t staff the clinic, but the HM group is its major source of referrals, says Dean Watson, MD, chief medical officer at TMH. Patients can be followed for up to eight weeks, during which time they get comprehensive assessments, medication review and optimization, and referral by the clinic social worker to a PCP and to available community services.

“Three years ago, we came up with the idea for a patient population we know is at high risk for readmission. Why don’t we partner with organizations in the community, form a clinic, teach students and residents, and learn together?” Dr. Watson says. “In addition to the usual patients, TMH targets those who have been readmitted to the hospital three times or more in the past year.”

The clinic, open five days a week, is staffed by a physician, nurse practitioner, telephonic nurse, and social worker, and also has a geriatric assessment clinic.

“We set up a system to identify patients through our electronic health record, and when they come to the clinic, we focus on their social environment and other non-medical issues that might cause readmissions,” he says. The clinic has a pharmacy and funds to support medications for patients without insurance. “In our first six months, we reduced emergency room visits and readmissions for these patients by 68 percent.”

One key partner, Capital Health Plan, bought and refurbished a building, and made it available for the clinic at no cost. Capital’s motivation, says Tom Glennon, a senior vice president for the plan, is its commitment to the community and to community service.

“We’re a nonprofit HMO. We’re focused on what we can do to serve the community, and we’re looking at this as a way for the hospital to have fewer costly, unreimbursed bouncebacks,” Glennon says. “That’s a win-win for all of us.”

Most of the patients who use the clinic are not members of Capital Health Plan, Glennon adds. “If we see CHP members turning up at the transitions clinic, then we have a problem—a breakdown in our case management,” he explains. “Our goal is to have our members taken care of by primary-care providers.”

Hard Data? Not So Fast

How many post-discharge clinics are in operation today is not known. Fundamental financial data, too, are limited, but some say it is unlikely a post-discharge clinic will cover operating expenses from billing revenues alone.

Thus, such clinics will require funding from the hospital, HM group, health system, or health plans, based on the benefits the clinic provides to discharged patients and the impact on 30-day readmissions (for more about the logistical challenges post-discharge clinics present, see “What Do PCPs Think?”).

Some also suggest that many of the post-discharge clinics now in operation are too new to have demonstrated financial impact or return on investment. “We have not yet been asked to show our financial viability,” Dr. Doctoroff says. “I think the clinic leadership thinks we are fulfilling other goals for now, such as creating easier access for their patients after discharge.”

Amy Boutwell, MD, MPP, a hospitalist at Newton Wellesley Hospital in Massachusetts and founder of Collaborative Healthcare Strategies, is among the post-discharge skeptics. She agrees with Dr. Williams that the post-discharge concept is more of a temporary fix to the long-term issues in primary care. “I think the idea is getting more play than actual activity out there right now,” she says. “We need to find opportunities to manage transitions within our scope today and tomorrow while strategically looking at where we want to be in five years [as hospitals and health systems].”

Dr. Boutwell says she’s experienced the frustration of trying to make follow-up appointments with physicians who don’t have any open slots for hospitalized patients awaiting discharge. “We think of follow up as physician-led, but there are alternatives and physician extenders,” she says. “It is well-documented that our healthcare system underuses home health care and other services that might be helpful. We forget how many other opportunities there are in our communities to get another clinician to touch the patient.”

Hospitalists, as key players in the healthcare system, can speak out in support of strengthening primary-care networks and building more collaborative relationships with PCPs, according to Dr. Williams. “If you’re going to set up an outpatient clinic, ideally, have it staffed by PCPs who can funnel the patients into primary-care networks. If that’s not feasible, then hospitalists should proceed with caution, since this approach begins to take them out of their scope of practice,” he says.

With 13 years of experience in urban hospital settings, Dr. Williams is familiar with the dangers unassigned patients present at discharge. “But I don’t know that we’ve yet optimized the hospital discharge process at any hospital in the United States,” he says.

That said, Dr. Williams knows his hospital in downtown Chicago is now working to establish a post-discharge clinic. It will be staffed by PCPs and will target patients who don’t have a PCP, are on Medicaid, or lack insurance.

“Where it starts to make me uncomfortable,” Dr. Williams says, “is what happens when you follow patients out into the outpatient setting?

It’s hard to do just one visit and draw the line. Yes, you may prevent a readmission, but the patient is still left with chronic illness and the need for primary care.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Goodman, DC, Fisher ES, Chang C. After Hospitalization: A Dartmouth Atlas Report on Post-Acute Care for Medicare Beneficiaries. Dartmouth Atlas website. Available at: www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/Post_discharge_events_092811.pdf. Accessed Nov. 3, 2011.

- Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 3-day rehospitalization: A systematic review. Ann Int Med. 2011;155(8): 520-528.

- Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: Examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397.

- Shu CC, Hsu NC, Lin YF, et al. Integrated post-discharge transitional care in Taiwan. BMC Medicine website. Available at: www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/96. Accessed Nov. 1, 2011.

The hospitalist concept was established on the foundation of timely, informative handoffs to primary-care physicians (PCPs) once a patient’s hospital stay is complete. With sicker patients and shorter hospital stays, pending test results, and complex post-discharge medication regimens to sort out, this handoff is crucial to successful discharges. But what if a discharged patient can’t get in to see the PCP, or has no established PCP?

Recent research on hospital readmissions by the Dartmouth Atlas Project found that only 42% of hospitalized Medicare patients had any contact with a primary-care clinician within 14 days of discharge.1 For patients with ongoing medical needs, such missed connections are a major contributor to hospital readmissions, and thus a target for hospitals and HM groups wanting to control their readmission rates before Medicare imposes reimbursement penalties starting in October 2012 (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011, p. 1).

One proposed solution is the post-discharge clinic, typically located on or near a hospital’s campus and staffed by hospitalists, PCPs, or advanced-practice nurses. The patient can be seen once or a few times in the post-discharge clinic to make sure that health education started in the hospital is understood and followed, and that prescriptions ordered in the hospital are being taken on schedule.

—Lauren Doctoroff, MD, hospitalist, director, post-discharge clinic, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, describes hospitalist-led post-discharge clinics as “Band-Aids for an inadequate primary-care system.” What would be better, he says, is focusing on the underlying problem and working to improve post-discharge access to primary care. Dr. Williams acknowledges, however, that sometimes a patch is needed to stanch the blood flow—e.g., to better manage care transitions—while waiting on healthcare reform and medical homes to improve care coordination throughout the system.

Working in a post-discharge clinic might seem like “a stretch for many hospitalists, especially those who chose this field because they didn’t want to do outpatient medicine,” says Lauren Doctoroff, MD, a hospitalist who directs a post-discharge clinic at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. “But there are times when it may be appropriate for hospital-based doctors to extend their responsibility out of the hospital.”

Dr. Doctoroff also says that working in such a clinic can be practice-changing for hospitalists. “All of a sudden, you have a different view of your hospitalized patients, and you start to ask different questions while they’re in the hospital than you ever did before,” she explains.

What is a Post-Discharge Clinic?

The post-discharge clinic, also known as a transitional-care clinic or after-care clinic, is intended to bridge medical coverage between the hospital and primary care. The clinic at BIDMC is for patients affiliated with its Health Care Associates faculty practice “discharged from either our hospital or another hospital, who need care that their PCP or specialist, because of scheduling conflicts, cannot provide within the needed time frame,” Dr. Doctoroff says.

Four hospitalists from BIDMC’s large HM group were selected to staff the clinic. The hospitalists work in one-month rotations (a total of three months on service per year), and are relieved of other responsibilities during their month in clinic. They provide five half-day clinic sessions per week, with a 40-minute-per-patient visit schedule. Thirty minutes are allotted for patients referred from the hospital’s ED who did not get admitted to the hospital but need clinical follow-up.

The clinic is based in a BIDMC-affiliated primary-care practice, “which allows us to use its administrative structure and logistical support,” Dr. Doctoroff explains. “A hospital-based administrative service helps set up outpatient visits prior to discharge using computerized physician order entry and a scheduling algorhythm.” (See Figure 1) Patients who can be seen by their PCP in a timely fashion are referred to the PCP office; if not, they are scheduled in the post-discharge clinic. “That helps preserve the PCP relationship, which I think is paramount,” she says.

The first two years were spent getting the clinic established, but in the near future, BIDMC will start measuring such outcomes as access to care and quality. “But not necessarily readmission rates,” Dr. Doctoroff adds. “I know many people think of post-discharge clinics in the context of preventing readmissions, although we don’t have the data yet to fully support that. In fact, some readmissions may result from seeing a doctor. If you get a closer look at some patients after discharge and they are doing badly, they are more likely to be readmitted than if they had just stayed home.” In such cases, readmission could actually be a better outcome for the patient, she notes.

Dr. Doctoroff describes a typical user of her post-discharge clinic as a non-English-speaking patient who was discharged from the hospital with severe back pain from a herniated disk. “He came back to see me 10 days later, still barely able to walk. He hadn’t been able to fill any of the prescriptions from his hospital stay. Within two hours after I saw him, we got his meds filled and outpatient services set up,” she says. “We take care of many patients like him in the hospital with acute pain issues, whom we discharge as soon as they can walk, and later we see them limping into outpatient clinics. It makes me think differently now about how I plan their discharges.”

—Shay Martinez, MD, hospitalist, medical director, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle

Who else needs these clinics? Dr. Doctoroff suggests two ways of looking at the question.

“Even for a simple patient admitted to the hospital, that can represent a significant change in the medical picture—a sort of sentinel event. In the discharge clinic, we give them an opportunity to review the hospitalization and answer their questions,” she says. “A lot of information presented to patients in the hospital is not well heard, and the initial visit may be their first time to really talk about what happened.” For other patients with conditions such as congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or poorly controlled diabetes, treatment guidelines might dictate a pattern for post-discharge follow-up—for example, medical visits in seven or 10 days.

In Seattle, Harborview Medical Center established its After Care Clinic, staffed by hospitalists and nurse practitioners, to provide transitional care for patients discharged from inpatient wards or the ED in need of follow-up, says medical director and hospitalist Shay Martinez, MD. A second priority is to see any CHF patient within 48 hours of discharge.

“We try to limit patients to a maximum of three visits in our clinic,” she says. “At that point, we help them get established in a medical home, either here in one of our primary-care clinics, or in one of the many excellent community clinics in the area.