User login

Comparing the efficacy and safety of common SIADH treatments

Background: Hyponatremia caused by SIADH is common in hospitalized patients, and most evidence for treatment comes from noncontrolled studies. This study aims to investigate the efficacy and safety of fluid restriction compared with furosemide, with or without NaCl supplementation, for treating SIADH.

Study design: Open-label randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Single center in Thailand.

Synopsis: There were 92 participants randomized to fluid restriction alone, fluid restriction and furosemide, or fluid restriction, furosemide, and NaCl supplementation. The authors assessed the primary outcome, change in sodium, at 4, 7, 14, and 28 days (baseline mean Na 125 mmol/L). By day 4, all groups had a significant increase in sodium (mean delta 5 mmol/L). The time to achieve a safe sodium level (Na less than 130 mmol/L) was not different among groups. Acute kidney injury was most common in patients who received furosemide and NaCl supplementation, compared with the fluid restriction and fluid restriction plus furosemide groups (32%, 10%, 17%, respectively; P = .07). Hypokalemia was also most common in the furosemide and NaCl group (42%, 13%, 23%, respectively; P = .01). Limitations include open-label study design, poor fluid restriction adherence (63% overall), and inflexible treatment regimens that excluded treatment with oral potassium.

Bottom line: In treatment of hyponatremia caused by SIADH, there was no benefit to adding furosemide with or without NaCl supplementation to fluid restriction. However, there was potential associated risk of acute kidney injury and hypokalemia.Citation: Krisanapan P et al. Efficacy of furosemide, oral sodium chloride, and fluid restriction for treatment of syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (SIADH): An open-label randomized controlled study (the EFFUSE-FLUID trial). Am J Kidney Dis. 2020 Aug;76(2):203-12. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.11.012.

Dr. Welter is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and instructor of medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, both in Chicago.

Background: Hyponatremia caused by SIADH is common in hospitalized patients, and most evidence for treatment comes from noncontrolled studies. This study aims to investigate the efficacy and safety of fluid restriction compared with furosemide, with or without NaCl supplementation, for treating SIADH.

Study design: Open-label randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Single center in Thailand.

Synopsis: There were 92 participants randomized to fluid restriction alone, fluid restriction and furosemide, or fluid restriction, furosemide, and NaCl supplementation. The authors assessed the primary outcome, change in sodium, at 4, 7, 14, and 28 days (baseline mean Na 125 mmol/L). By day 4, all groups had a significant increase in sodium (mean delta 5 mmol/L). The time to achieve a safe sodium level (Na less than 130 mmol/L) was not different among groups. Acute kidney injury was most common in patients who received furosemide and NaCl supplementation, compared with the fluid restriction and fluid restriction plus furosemide groups (32%, 10%, 17%, respectively; P = .07). Hypokalemia was also most common in the furosemide and NaCl group (42%, 13%, 23%, respectively; P = .01). Limitations include open-label study design, poor fluid restriction adherence (63% overall), and inflexible treatment regimens that excluded treatment with oral potassium.

Bottom line: In treatment of hyponatremia caused by SIADH, there was no benefit to adding furosemide with or without NaCl supplementation to fluid restriction. However, there was potential associated risk of acute kidney injury and hypokalemia.Citation: Krisanapan P et al. Efficacy of furosemide, oral sodium chloride, and fluid restriction for treatment of syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (SIADH): An open-label randomized controlled study (the EFFUSE-FLUID trial). Am J Kidney Dis. 2020 Aug;76(2):203-12. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.11.012.

Dr. Welter is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and instructor of medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, both in Chicago.

Background: Hyponatremia caused by SIADH is common in hospitalized patients, and most evidence for treatment comes from noncontrolled studies. This study aims to investigate the efficacy and safety of fluid restriction compared with furosemide, with or without NaCl supplementation, for treating SIADH.

Study design: Open-label randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Single center in Thailand.

Synopsis: There were 92 participants randomized to fluid restriction alone, fluid restriction and furosemide, or fluid restriction, furosemide, and NaCl supplementation. The authors assessed the primary outcome, change in sodium, at 4, 7, 14, and 28 days (baseline mean Na 125 mmol/L). By day 4, all groups had a significant increase in sodium (mean delta 5 mmol/L). The time to achieve a safe sodium level (Na less than 130 mmol/L) was not different among groups. Acute kidney injury was most common in patients who received furosemide and NaCl supplementation, compared with the fluid restriction and fluid restriction plus furosemide groups (32%, 10%, 17%, respectively; P = .07). Hypokalemia was also most common in the furosemide and NaCl group (42%, 13%, 23%, respectively; P = .01). Limitations include open-label study design, poor fluid restriction adherence (63% overall), and inflexible treatment regimens that excluded treatment with oral potassium.

Bottom line: In treatment of hyponatremia caused by SIADH, there was no benefit to adding furosemide with or without NaCl supplementation to fluid restriction. However, there was potential associated risk of acute kidney injury and hypokalemia.Citation: Krisanapan P et al. Efficacy of furosemide, oral sodium chloride, and fluid restriction for treatment of syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (SIADH): An open-label randomized controlled study (the EFFUSE-FLUID trial). Am J Kidney Dis. 2020 Aug;76(2):203-12. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.11.012.

Dr. Welter is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and instructor of medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, both in Chicago.

Oakland score identifies patients with lower GI bleed at low risk for adverse events

Background: The Oakland score was initially designed to be used in patients presenting with LGIB in the urgent, emergent, or primary care setting to help predict risk of readmission and determine if outpatient management is feasible. National guidelines in the United Kingdom have recommended use of the Oakland score despite limited external validation for the triage of patients with acute LGIB. This study aimed to externally validate the Oakland score in a large population in the United States and compare the performance at two thresholds.

Study design: Retrospective observational study.

Setting: 140 hospitals across the United States.

Synopsis: In this prognostic study, 38,067 patients were identified retrospectively using ICD-10 codes that were consistent with a diagnosis of LGIB and were admitted to the hospital. The Oakland score consisted of seven variables, including age, sex, prior hospitalization with LGIB, digital rectal exam results, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and hemoglobin concentration. The primary outcome was safe discharge from the hospital, defined as absence of in-hospital rebleeding, RBC transfusion, therapeutic colonoscopy, mesenteric embolization or laparotomy for bleeding, in-hospital death, or readmission with subsequent LGIB in 28 days. In total, 47.9% of the identified patients experienced no adverse outcomes and were classified as meeting criteria for safe discharge. In addition, 8.7% of patients scored 8 points or fewer with a sensitivity of 98.4% and specificity of 16.0% for safe discharge. A sensitivity of 96% was maintained after increasing the threshold to 10 points or fewer with a specificity of 31.9%, suggesting the threshold can be increased while still maintaining adequate sensitivity. The study suggests that, by using the Oakland score threshold of 8, hospital admission may be avoided in low-risk patients leading to a savings of at least $44.5 million and even more if the threshold is increased to 10. Low specificity does present limitation of the score as some patients considered to be at risk for adverse events may have been safely discharged and managed as an outpatient, avoiding hospitalization.

Bottom line: The Oakland score was externally validated for use in assessing risk of adverse outcomes in patients with LGIB and had a high sensitivity but low specificity for identifying low-risk patients.

Citation: Oakland K et al. External validation of the Oakland score to assess safe hospital discharge among adult patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jul 1;3:e209630. doi:

Dr. Steker is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and instructor of medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, both in Chicago.

Background: The Oakland score was initially designed to be used in patients presenting with LGIB in the urgent, emergent, or primary care setting to help predict risk of readmission and determine if outpatient management is feasible. National guidelines in the United Kingdom have recommended use of the Oakland score despite limited external validation for the triage of patients with acute LGIB. This study aimed to externally validate the Oakland score in a large population in the United States and compare the performance at two thresholds.

Study design: Retrospective observational study.

Setting: 140 hospitals across the United States.

Synopsis: In this prognostic study, 38,067 patients were identified retrospectively using ICD-10 codes that were consistent with a diagnosis of LGIB and were admitted to the hospital. The Oakland score consisted of seven variables, including age, sex, prior hospitalization with LGIB, digital rectal exam results, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and hemoglobin concentration. The primary outcome was safe discharge from the hospital, defined as absence of in-hospital rebleeding, RBC transfusion, therapeutic colonoscopy, mesenteric embolization or laparotomy for bleeding, in-hospital death, or readmission with subsequent LGIB in 28 days. In total, 47.9% of the identified patients experienced no adverse outcomes and were classified as meeting criteria for safe discharge. In addition, 8.7% of patients scored 8 points or fewer with a sensitivity of 98.4% and specificity of 16.0% for safe discharge. A sensitivity of 96% was maintained after increasing the threshold to 10 points or fewer with a specificity of 31.9%, suggesting the threshold can be increased while still maintaining adequate sensitivity. The study suggests that, by using the Oakland score threshold of 8, hospital admission may be avoided in low-risk patients leading to a savings of at least $44.5 million and even more if the threshold is increased to 10. Low specificity does present limitation of the score as some patients considered to be at risk for adverse events may have been safely discharged and managed as an outpatient, avoiding hospitalization.

Bottom line: The Oakland score was externally validated for use in assessing risk of adverse outcomes in patients with LGIB and had a high sensitivity but low specificity for identifying low-risk patients.

Citation: Oakland K et al. External validation of the Oakland score to assess safe hospital discharge among adult patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jul 1;3:e209630. doi:

Dr. Steker is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and instructor of medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, both in Chicago.

Background: The Oakland score was initially designed to be used in patients presenting with LGIB in the urgent, emergent, or primary care setting to help predict risk of readmission and determine if outpatient management is feasible. National guidelines in the United Kingdom have recommended use of the Oakland score despite limited external validation for the triage of patients with acute LGIB. This study aimed to externally validate the Oakland score in a large population in the United States and compare the performance at two thresholds.

Study design: Retrospective observational study.

Setting: 140 hospitals across the United States.

Synopsis: In this prognostic study, 38,067 patients were identified retrospectively using ICD-10 codes that were consistent with a diagnosis of LGIB and were admitted to the hospital. The Oakland score consisted of seven variables, including age, sex, prior hospitalization with LGIB, digital rectal exam results, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and hemoglobin concentration. The primary outcome was safe discharge from the hospital, defined as absence of in-hospital rebleeding, RBC transfusion, therapeutic colonoscopy, mesenteric embolization or laparotomy for bleeding, in-hospital death, or readmission with subsequent LGIB in 28 days. In total, 47.9% of the identified patients experienced no adverse outcomes and were classified as meeting criteria for safe discharge. In addition, 8.7% of patients scored 8 points or fewer with a sensitivity of 98.4% and specificity of 16.0% for safe discharge. A sensitivity of 96% was maintained after increasing the threshold to 10 points or fewer with a specificity of 31.9%, suggesting the threshold can be increased while still maintaining adequate sensitivity. The study suggests that, by using the Oakland score threshold of 8, hospital admission may be avoided in low-risk patients leading to a savings of at least $44.5 million and even more if the threshold is increased to 10. Low specificity does present limitation of the score as some patients considered to be at risk for adverse events may have been safely discharged and managed as an outpatient, avoiding hospitalization.

Bottom line: The Oakland score was externally validated for use in assessing risk of adverse outcomes in patients with LGIB and had a high sensitivity but low specificity for identifying low-risk patients.

Citation: Oakland K et al. External validation of the Oakland score to assess safe hospital discharge among adult patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jul 1;3:e209630. doi:

Dr. Steker is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and instructor of medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, both in Chicago.

What makes a urinary tract infection complicated?

Consider anatomical and severity risk factors

Case

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents with acute dysuria, fever, and flank pain. She had a urinary tract infection (UTI) 3 months prior treated with nitrofurantoin. Temperature is 102° F, heart rate 112 beats per minute, and the remainder of vital signs are normal. She has left costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine microscopy shows 70 WBCs per high power field and bacteria. Is this urinary tract infection complicated?

Background

The urinary tract is divided into the upper tract, which includes the kidneys and ureters, and the lower urinary tract, which includes the bladder, urethra, and prostate. Infection of the lower urinary tract is referred to as cystitis while infection of the upper urinary tract is pyelonephritis. A UTI is the colonization of pathogen(s) within the urinary system that causes an inflammatory response resulting in symptoms and requiring treatment. UTIs occur when there is reduced urine flow, an increase in colonization risk, and when there are factors that facilitate ascent such as catheterization or incontinence.

There are an estimated 150 million cases of UTIs worldwide per year, accounting for $6 billion in health care expenditures.1 In the inpatient setting, about 40% of nosocomial infections are associated with urinary catheters. This equates to about 1 million catheter-associated UTIs per year in the United States, and up to 40% of hospital gram-negative bacteremia per year are caused by UTIs.1

UTIs are often classified as either uncomplicated or complicated infections, which can influence the depth of management. UTIs have a wide spectrum of symptoms and can manifest anywhere from mild dysuria treated successfully with outpatient antibiotics to florid sepsis. Uncomplicated simple cystitis is often treated as an outpatient with oral nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.2 Complicated UTIs are treated with broader antimicrobial coverage, and depending on severity, could require intravenous antibiotics. Many factors affect how a UTI manifests and determining whether an infection is “uncomplicated” or “complicated” is an important first step in guiding management. Unfortunately, there are differing classifications of “complicated” UTIs, making it a complicated issue itself. We outline two common approaches.

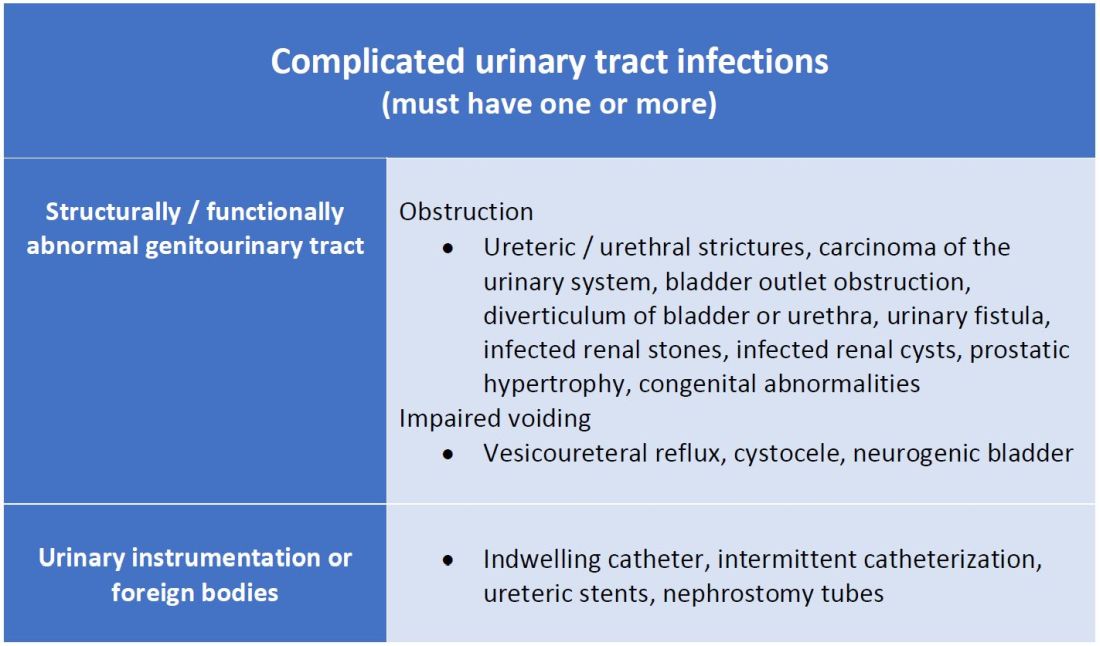

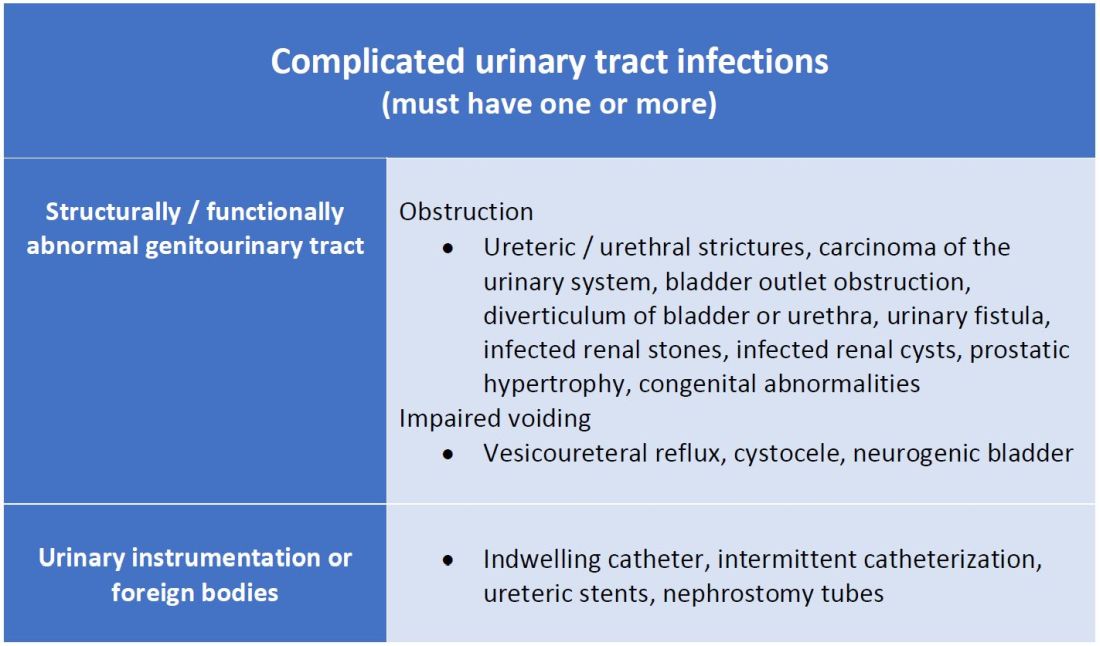

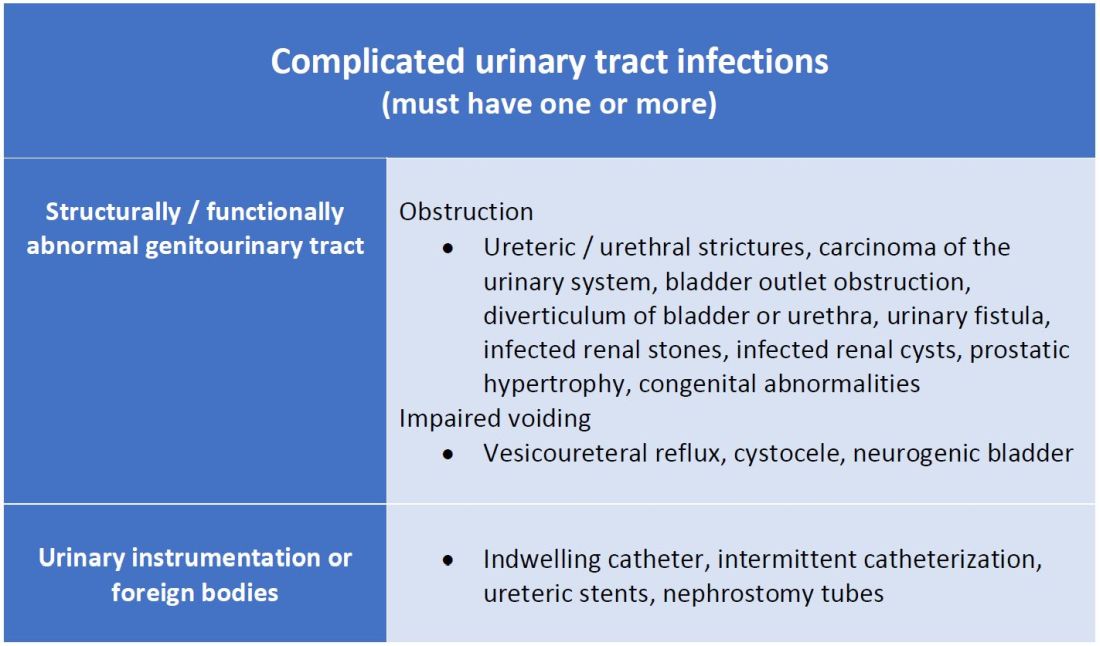

Anatomic approach

A commonly recognized definition is from the American Urological Association, which states that complicated UTIs are symptomatic cases associated with the presence of “underlying, predisposing conditions and not necessarily clinical severity, invasiveness, or complications.”3 These factors include structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities or urinary instrumentation (see Table 1). These predisposing conditions can increase microbial colonization and decrease therapy efficacy, thus increasing the frequency of infection and relapse.

This population of patients is at high risk of infections with more resistant bacteria such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli since they often lack the natural genitourinary barriers to infection. In addition, these patients more often undergo multiple antibiotic courses for their frequent infections, which also contributes to their risk of ESBL infections. Genitourinary abnormalities interfere with normal voiding, resulting in impaired flushing of bacteria. For instance, obstruction inhibits complete urinary drainage and increases the persistence of bacteria in biofilms, especially if there are stones or indwelling devices present. Biofilms usually contain a high concentration of organisms including Proteus mirabilis, Morgenella morganii, and Providencia spp.4 Keep in mind that, if there is an obstruction, the urinalysis might be without pyuria or bacteriuria.

Instrumentation increases infection risks through the direct introduction of bacteria into the genitourinary tract. Despite the efforts in maintaining sterility in urinary catheter placement, catheters provide a nidus for infection. Catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI) is defined by the Infectious Disease Society of America as UTIs that occur in patients with an indwelling catheter or who had a catheter removed for less than 48 hours who develop urinary symptoms and cultures positive for uropathogenic bacteria.4 Studies show that in general, patients with indwelling catheters will develop bacteriuria over time, with 10%-25% eventually developing symptoms.

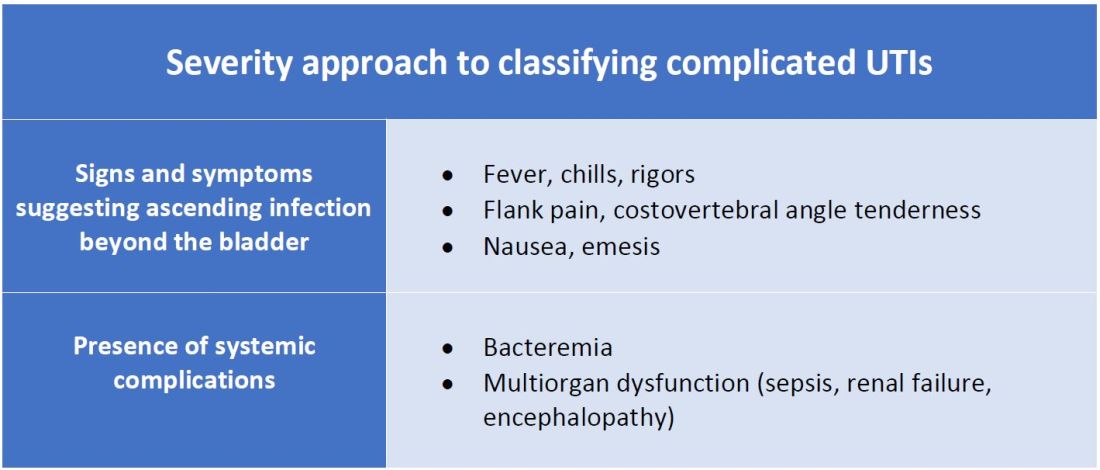

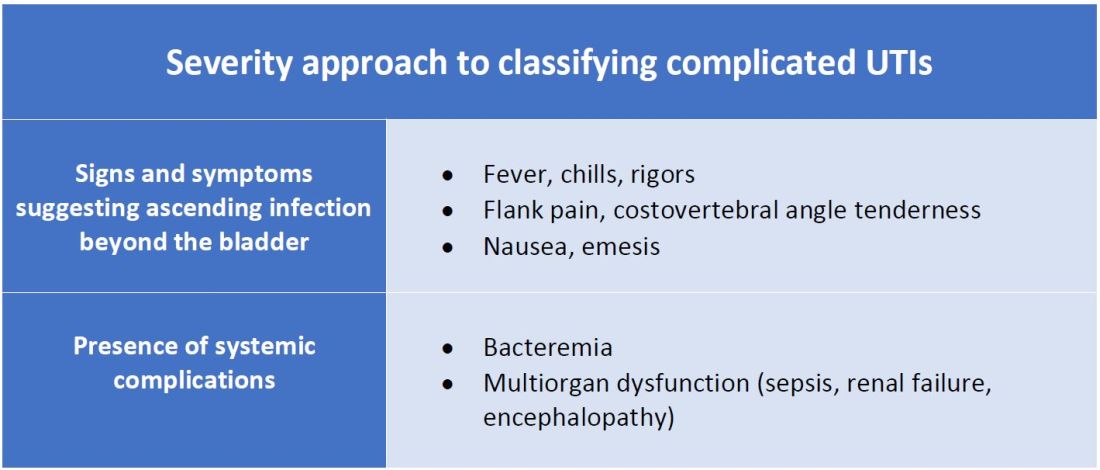

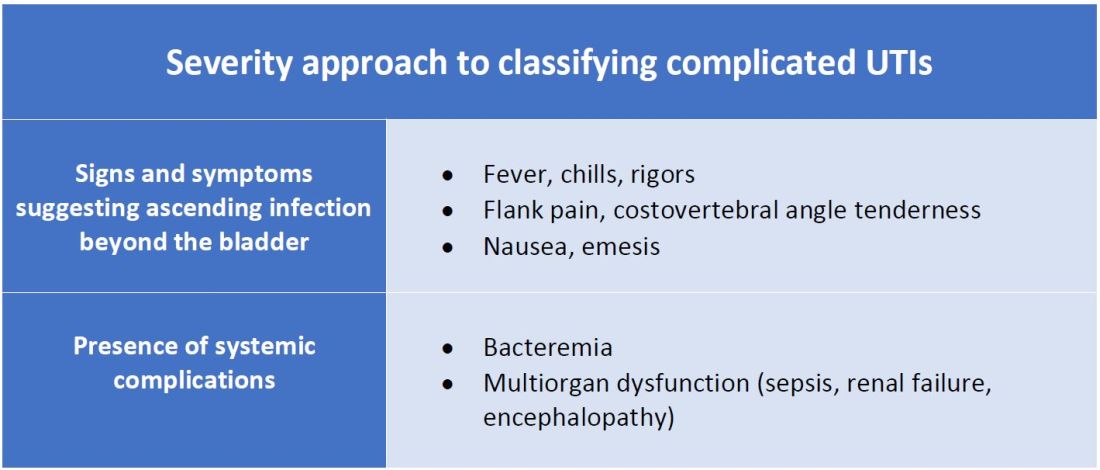

Severity approach

There are other schools of thought that categorize uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs based on the severity of presentation (see Table 2). An uncomplicated UTI would be classified as symptoms and signs of simple cystitis limited to dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain. Using a symptom severity approach, systemic findings such as fever, chills, emesis, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, or other findings of sepsis would be classified as a complicated UTI. These systemic findings would suggest an extension of infection beyond the bladder.

The argument for a symptomatic-based approach of classification is that the severity of symptoms should dictate the degree of management. Not all UTIs in the anatomic approach are severe. In fact, populations that are considered at risk for complicated UTIs by the AUA guidelines in Table 1 often have mild symptomatic cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the colonization of organisms in the urinary tract without active infection. For instance, bacteriuria is present in almost 100% of people with chronic indwelling catheters, 30%-40% of neurogenic bladder requiring intermittent catheterization, and 50% of elderly nursing home residents.4 Not all bacteriuria triggers enough of an inflammatory response to cause symptoms that require treatment.

Ultimate clinical judgment

Although there are multiple different society recommendations in distinguishing uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs, considering both anatomical and severity risk factors can better aid in clinical decision-making rather than abiding by one classification method alone.

Uncomplicated UTIs from the AUA guidelines can cause severe infections that might require longer courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics. On the other hand, people with anatomic abnormalities can present with mild symptoms that can be treated with a narrow-spectrum antibiotic for a standard time course. Recognizing the severity of the infection and using clinical judgment aids in antibiotic stewardship.

Although the existence of algorithmic approaches can help guide clinical judgment, accounting for the spectrum of host and bacterial factors should ultimately determine the complexity of the disease and management.3 Using clinical suspicion to determine when a UTI should be treated as a complicated infection can ensure effective treatment and decrease the likelihood of sepsis, renal scarring, or end-stage disease.5

Back to the case

The case presents an elderly woman with diabetes presenting with sepsis from a UTI. Because of a normal urinary tract and no prior instrumentation, by the AUA definition, she would be classified as an uncomplicated UTI; however, we would classify her as a complicated UTI based on the severity of her presentation. She has a fever, tachycardia, flank pain, and costovertebral angle tenderness that are evidence of infection extending beyond the bladder. She has sepsis warranting inpatient management. Prior urine culture results could aid in determining empiric treatment while waiting for new cultures. In her case, an intravenous antibiotic with broad gram-negative coverage such as ceftriaxone would be appropriate.

Bottom line

There are multiple interpretations of complicated UTIs including both an anatomical and severity approach. Clinical judgment regarding infection severity should determine the depth of management.

Dr. Vu is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Gray is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky and the Lexington Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

References

1. Folk CS. AUA Core Curriculum: Urinary Tract Infection (Adult). 2021 Mar 1. https://university.auanet.org/core_topic.cfm?coreid=92.

2. Gupta K et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 1;52(5):e103-20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257.

3. Johnson JR. Definition of Complicated Urinary Tract Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 February 15;64(4):529. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw751.

4. Nicolle LE, AMMI Canada Guidelines Committee. Complicated urinary tract infection in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(6):349-60. doi: 10.1155/2005/385768.

5. Melekos MD and Naber KG. Complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15(4):247-56. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00168-0.

Key points

- The anatomical approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the presence of underlying, predisposing conditions such as structurally or functionally abnormal genitourinary tract or urinary instrumentation or foreign bodies.

- The severity approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the severity of presentation including the presence of systemic manifestations.

- Both approaches should consider populations that are at risk for recurrent or multidrug-resistant infections and infections that can lead to high morbidity.

- Either approach can be used as a guide, but neither should replace clinical suspicion and judgment in determining the depth of treatment.

Additional reading

Choe HS et al. Summary of the UAA‐AAUS guidelines for urinary tract infections. Int J Urol. 2018 Mar;25(3):175-85. doi:10.1111/iju.13493.

Nicolle LE et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Mar;40(5):643-54. doi: 10.1086/427507.

Wagenlehner FME et al. Epidemiology, definition and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Urol. 2020 Oct;17:586-600. doi:10.1038/s41585-020-0362-4.

Wallace DW et al. Urinalysis: A simple test with complicated interpretation. J Urgent Care Med. 2020 July-Aug;14(10):11-4.

Quiz

A 68-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the emergency department with acute fever, chills, dysuria, frequency, and suprapubic pain. She has associated nausea, malaise, and fatigue. She takes metformin and denies recent antibiotic use. Her temperature is 102.8° F, heart rate 118 beats per minute, blood pressure 118/71 mm Hg, and her respiratory rate is 24 breaths per minute. She is ill-appearing and has mild suprapubic tenderness. White blood cell count is 18 k/mcL. Urinalysis is positive for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and bacteria. Urine microscopy has 120 white blood cells per high power field. What is the most appropriate treatment?

A. Azithromycin

B. Ceftriaxone

C. Cefepime and vancomycin

D. Nitrofurantoin

The answer is B. The patient presents with sepsis secondary to a urinary tract infection. Using the anatomic approach this would be classified as uncomplicated. Using the severity approach, this would be classified as a complicated urinary tract infection. With fever, chills, and signs of sepsis, it’s likely her infection extends beyond the bladder. Given the severity of her presentation, we’d favor treating her as a complicated urinary tract infection with intravenous ceftriaxone. There is no suggestion of resistance or additional MRSA risk factors requiring intravenous vancomycin or cefepime. Nitrofurantoin, although a first-line treatment for uncomplicated cystitis, would not be appropriate if there is suspicion infection extends beyond the bladder. Azithromycin is a first-line option for chlamydia trachomatis, but not a urinary tract infection.

Consider anatomical and severity risk factors

Consider anatomical and severity risk factors

Case

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents with acute dysuria, fever, and flank pain. She had a urinary tract infection (UTI) 3 months prior treated with nitrofurantoin. Temperature is 102° F, heart rate 112 beats per minute, and the remainder of vital signs are normal. She has left costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine microscopy shows 70 WBCs per high power field and bacteria. Is this urinary tract infection complicated?

Background

The urinary tract is divided into the upper tract, which includes the kidneys and ureters, and the lower urinary tract, which includes the bladder, urethra, and prostate. Infection of the lower urinary tract is referred to as cystitis while infection of the upper urinary tract is pyelonephritis. A UTI is the colonization of pathogen(s) within the urinary system that causes an inflammatory response resulting in symptoms and requiring treatment. UTIs occur when there is reduced urine flow, an increase in colonization risk, and when there are factors that facilitate ascent such as catheterization or incontinence.

There are an estimated 150 million cases of UTIs worldwide per year, accounting for $6 billion in health care expenditures.1 In the inpatient setting, about 40% of nosocomial infections are associated with urinary catheters. This equates to about 1 million catheter-associated UTIs per year in the United States, and up to 40% of hospital gram-negative bacteremia per year are caused by UTIs.1

UTIs are often classified as either uncomplicated or complicated infections, which can influence the depth of management. UTIs have a wide spectrum of symptoms and can manifest anywhere from mild dysuria treated successfully with outpatient antibiotics to florid sepsis. Uncomplicated simple cystitis is often treated as an outpatient with oral nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.2 Complicated UTIs are treated with broader antimicrobial coverage, and depending on severity, could require intravenous antibiotics. Many factors affect how a UTI manifests and determining whether an infection is “uncomplicated” or “complicated” is an important first step in guiding management. Unfortunately, there are differing classifications of “complicated” UTIs, making it a complicated issue itself. We outline two common approaches.

Anatomic approach

A commonly recognized definition is from the American Urological Association, which states that complicated UTIs are symptomatic cases associated with the presence of “underlying, predisposing conditions and not necessarily clinical severity, invasiveness, or complications.”3 These factors include structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities or urinary instrumentation (see Table 1). These predisposing conditions can increase microbial colonization and decrease therapy efficacy, thus increasing the frequency of infection and relapse.

This population of patients is at high risk of infections with more resistant bacteria such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli since they often lack the natural genitourinary barriers to infection. In addition, these patients more often undergo multiple antibiotic courses for their frequent infections, which also contributes to their risk of ESBL infections. Genitourinary abnormalities interfere with normal voiding, resulting in impaired flushing of bacteria. For instance, obstruction inhibits complete urinary drainage and increases the persistence of bacteria in biofilms, especially if there are stones or indwelling devices present. Biofilms usually contain a high concentration of organisms including Proteus mirabilis, Morgenella morganii, and Providencia spp.4 Keep in mind that, if there is an obstruction, the urinalysis might be without pyuria or bacteriuria.

Instrumentation increases infection risks through the direct introduction of bacteria into the genitourinary tract. Despite the efforts in maintaining sterility in urinary catheter placement, catheters provide a nidus for infection. Catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI) is defined by the Infectious Disease Society of America as UTIs that occur in patients with an indwelling catheter or who had a catheter removed for less than 48 hours who develop urinary symptoms and cultures positive for uropathogenic bacteria.4 Studies show that in general, patients with indwelling catheters will develop bacteriuria over time, with 10%-25% eventually developing symptoms.

Severity approach

There are other schools of thought that categorize uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs based on the severity of presentation (see Table 2). An uncomplicated UTI would be classified as symptoms and signs of simple cystitis limited to dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain. Using a symptom severity approach, systemic findings such as fever, chills, emesis, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, or other findings of sepsis would be classified as a complicated UTI. These systemic findings would suggest an extension of infection beyond the bladder.

The argument for a symptomatic-based approach of classification is that the severity of symptoms should dictate the degree of management. Not all UTIs in the anatomic approach are severe. In fact, populations that are considered at risk for complicated UTIs by the AUA guidelines in Table 1 often have mild symptomatic cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the colonization of organisms in the urinary tract without active infection. For instance, bacteriuria is present in almost 100% of people with chronic indwelling catheters, 30%-40% of neurogenic bladder requiring intermittent catheterization, and 50% of elderly nursing home residents.4 Not all bacteriuria triggers enough of an inflammatory response to cause symptoms that require treatment.

Ultimate clinical judgment

Although there are multiple different society recommendations in distinguishing uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs, considering both anatomical and severity risk factors can better aid in clinical decision-making rather than abiding by one classification method alone.

Uncomplicated UTIs from the AUA guidelines can cause severe infections that might require longer courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics. On the other hand, people with anatomic abnormalities can present with mild symptoms that can be treated with a narrow-spectrum antibiotic for a standard time course. Recognizing the severity of the infection and using clinical judgment aids in antibiotic stewardship.

Although the existence of algorithmic approaches can help guide clinical judgment, accounting for the spectrum of host and bacterial factors should ultimately determine the complexity of the disease and management.3 Using clinical suspicion to determine when a UTI should be treated as a complicated infection can ensure effective treatment and decrease the likelihood of sepsis, renal scarring, or end-stage disease.5

Back to the case

The case presents an elderly woman with diabetes presenting with sepsis from a UTI. Because of a normal urinary tract and no prior instrumentation, by the AUA definition, she would be classified as an uncomplicated UTI; however, we would classify her as a complicated UTI based on the severity of her presentation. She has a fever, tachycardia, flank pain, and costovertebral angle tenderness that are evidence of infection extending beyond the bladder. She has sepsis warranting inpatient management. Prior urine culture results could aid in determining empiric treatment while waiting for new cultures. In her case, an intravenous antibiotic with broad gram-negative coverage such as ceftriaxone would be appropriate.

Bottom line

There are multiple interpretations of complicated UTIs including both an anatomical and severity approach. Clinical judgment regarding infection severity should determine the depth of management.

Dr. Vu is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Gray is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky and the Lexington Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

References

1. Folk CS. AUA Core Curriculum: Urinary Tract Infection (Adult). 2021 Mar 1. https://university.auanet.org/core_topic.cfm?coreid=92.

2. Gupta K et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 1;52(5):e103-20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257.

3. Johnson JR. Definition of Complicated Urinary Tract Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 February 15;64(4):529. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw751.

4. Nicolle LE, AMMI Canada Guidelines Committee. Complicated urinary tract infection in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(6):349-60. doi: 10.1155/2005/385768.

5. Melekos MD and Naber KG. Complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15(4):247-56. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00168-0.

Key points

- The anatomical approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the presence of underlying, predisposing conditions such as structurally or functionally abnormal genitourinary tract or urinary instrumentation or foreign bodies.

- The severity approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the severity of presentation including the presence of systemic manifestations.

- Both approaches should consider populations that are at risk for recurrent or multidrug-resistant infections and infections that can lead to high morbidity.

- Either approach can be used as a guide, but neither should replace clinical suspicion and judgment in determining the depth of treatment.

Additional reading

Choe HS et al. Summary of the UAA‐AAUS guidelines for urinary tract infections. Int J Urol. 2018 Mar;25(3):175-85. doi:10.1111/iju.13493.

Nicolle LE et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Mar;40(5):643-54. doi: 10.1086/427507.

Wagenlehner FME et al. Epidemiology, definition and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Urol. 2020 Oct;17:586-600. doi:10.1038/s41585-020-0362-4.

Wallace DW et al. Urinalysis: A simple test with complicated interpretation. J Urgent Care Med. 2020 July-Aug;14(10):11-4.

Quiz

A 68-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the emergency department with acute fever, chills, dysuria, frequency, and suprapubic pain. She has associated nausea, malaise, and fatigue. She takes metformin and denies recent antibiotic use. Her temperature is 102.8° F, heart rate 118 beats per minute, blood pressure 118/71 mm Hg, and her respiratory rate is 24 breaths per minute. She is ill-appearing and has mild suprapubic tenderness. White blood cell count is 18 k/mcL. Urinalysis is positive for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and bacteria. Urine microscopy has 120 white blood cells per high power field. What is the most appropriate treatment?

A. Azithromycin

B. Ceftriaxone

C. Cefepime and vancomycin

D. Nitrofurantoin

The answer is B. The patient presents with sepsis secondary to a urinary tract infection. Using the anatomic approach this would be classified as uncomplicated. Using the severity approach, this would be classified as a complicated urinary tract infection. With fever, chills, and signs of sepsis, it’s likely her infection extends beyond the bladder. Given the severity of her presentation, we’d favor treating her as a complicated urinary tract infection with intravenous ceftriaxone. There is no suggestion of resistance or additional MRSA risk factors requiring intravenous vancomycin or cefepime. Nitrofurantoin, although a first-line treatment for uncomplicated cystitis, would not be appropriate if there is suspicion infection extends beyond the bladder. Azithromycin is a first-line option for chlamydia trachomatis, but not a urinary tract infection.

Case

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents with acute dysuria, fever, and flank pain. She had a urinary tract infection (UTI) 3 months prior treated with nitrofurantoin. Temperature is 102° F, heart rate 112 beats per minute, and the remainder of vital signs are normal. She has left costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine microscopy shows 70 WBCs per high power field and bacteria. Is this urinary tract infection complicated?

Background

The urinary tract is divided into the upper tract, which includes the kidneys and ureters, and the lower urinary tract, which includes the bladder, urethra, and prostate. Infection of the lower urinary tract is referred to as cystitis while infection of the upper urinary tract is pyelonephritis. A UTI is the colonization of pathogen(s) within the urinary system that causes an inflammatory response resulting in symptoms and requiring treatment. UTIs occur when there is reduced urine flow, an increase in colonization risk, and when there are factors that facilitate ascent such as catheterization or incontinence.

There are an estimated 150 million cases of UTIs worldwide per year, accounting for $6 billion in health care expenditures.1 In the inpatient setting, about 40% of nosocomial infections are associated with urinary catheters. This equates to about 1 million catheter-associated UTIs per year in the United States, and up to 40% of hospital gram-negative bacteremia per year are caused by UTIs.1

UTIs are often classified as either uncomplicated or complicated infections, which can influence the depth of management. UTIs have a wide spectrum of symptoms and can manifest anywhere from mild dysuria treated successfully with outpatient antibiotics to florid sepsis. Uncomplicated simple cystitis is often treated as an outpatient with oral nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.2 Complicated UTIs are treated with broader antimicrobial coverage, and depending on severity, could require intravenous antibiotics. Many factors affect how a UTI manifests and determining whether an infection is “uncomplicated” or “complicated” is an important first step in guiding management. Unfortunately, there are differing classifications of “complicated” UTIs, making it a complicated issue itself. We outline two common approaches.

Anatomic approach

A commonly recognized definition is from the American Urological Association, which states that complicated UTIs are symptomatic cases associated with the presence of “underlying, predisposing conditions and not necessarily clinical severity, invasiveness, or complications.”3 These factors include structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities or urinary instrumentation (see Table 1). These predisposing conditions can increase microbial colonization and decrease therapy efficacy, thus increasing the frequency of infection and relapse.

This population of patients is at high risk of infections with more resistant bacteria such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli since they often lack the natural genitourinary barriers to infection. In addition, these patients more often undergo multiple antibiotic courses for their frequent infections, which also contributes to their risk of ESBL infections. Genitourinary abnormalities interfere with normal voiding, resulting in impaired flushing of bacteria. For instance, obstruction inhibits complete urinary drainage and increases the persistence of bacteria in biofilms, especially if there are stones or indwelling devices present. Biofilms usually contain a high concentration of organisms including Proteus mirabilis, Morgenella morganii, and Providencia spp.4 Keep in mind that, if there is an obstruction, the urinalysis might be without pyuria or bacteriuria.

Instrumentation increases infection risks through the direct introduction of bacteria into the genitourinary tract. Despite the efforts in maintaining sterility in urinary catheter placement, catheters provide a nidus for infection. Catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI) is defined by the Infectious Disease Society of America as UTIs that occur in patients with an indwelling catheter or who had a catheter removed for less than 48 hours who develop urinary symptoms and cultures positive for uropathogenic bacteria.4 Studies show that in general, patients with indwelling catheters will develop bacteriuria over time, with 10%-25% eventually developing symptoms.

Severity approach

There are other schools of thought that categorize uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs based on the severity of presentation (see Table 2). An uncomplicated UTI would be classified as symptoms and signs of simple cystitis limited to dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain. Using a symptom severity approach, systemic findings such as fever, chills, emesis, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, or other findings of sepsis would be classified as a complicated UTI. These systemic findings would suggest an extension of infection beyond the bladder.

The argument for a symptomatic-based approach of classification is that the severity of symptoms should dictate the degree of management. Not all UTIs in the anatomic approach are severe. In fact, populations that are considered at risk for complicated UTIs by the AUA guidelines in Table 1 often have mild symptomatic cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the colonization of organisms in the urinary tract without active infection. For instance, bacteriuria is present in almost 100% of people with chronic indwelling catheters, 30%-40% of neurogenic bladder requiring intermittent catheterization, and 50% of elderly nursing home residents.4 Not all bacteriuria triggers enough of an inflammatory response to cause symptoms that require treatment.

Ultimate clinical judgment

Although there are multiple different society recommendations in distinguishing uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs, considering both anatomical and severity risk factors can better aid in clinical decision-making rather than abiding by one classification method alone.

Uncomplicated UTIs from the AUA guidelines can cause severe infections that might require longer courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics. On the other hand, people with anatomic abnormalities can present with mild symptoms that can be treated with a narrow-spectrum antibiotic for a standard time course. Recognizing the severity of the infection and using clinical judgment aids in antibiotic stewardship.

Although the existence of algorithmic approaches can help guide clinical judgment, accounting for the spectrum of host and bacterial factors should ultimately determine the complexity of the disease and management.3 Using clinical suspicion to determine when a UTI should be treated as a complicated infection can ensure effective treatment and decrease the likelihood of sepsis, renal scarring, or end-stage disease.5

Back to the case

The case presents an elderly woman with diabetes presenting with sepsis from a UTI. Because of a normal urinary tract and no prior instrumentation, by the AUA definition, she would be classified as an uncomplicated UTI; however, we would classify her as a complicated UTI based on the severity of her presentation. She has a fever, tachycardia, flank pain, and costovertebral angle tenderness that are evidence of infection extending beyond the bladder. She has sepsis warranting inpatient management. Prior urine culture results could aid in determining empiric treatment while waiting for new cultures. In her case, an intravenous antibiotic with broad gram-negative coverage such as ceftriaxone would be appropriate.

Bottom line

There are multiple interpretations of complicated UTIs including both an anatomical and severity approach. Clinical judgment regarding infection severity should determine the depth of management.

Dr. Vu is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Gray is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky and the Lexington Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

References

1. Folk CS. AUA Core Curriculum: Urinary Tract Infection (Adult). 2021 Mar 1. https://university.auanet.org/core_topic.cfm?coreid=92.

2. Gupta K et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 1;52(5):e103-20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257.

3. Johnson JR. Definition of Complicated Urinary Tract Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 February 15;64(4):529. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw751.

4. Nicolle LE, AMMI Canada Guidelines Committee. Complicated urinary tract infection in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(6):349-60. doi: 10.1155/2005/385768.

5. Melekos MD and Naber KG. Complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15(4):247-56. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00168-0.

Key points

- The anatomical approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the presence of underlying, predisposing conditions such as structurally or functionally abnormal genitourinary tract or urinary instrumentation or foreign bodies.

- The severity approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the severity of presentation including the presence of systemic manifestations.

- Both approaches should consider populations that are at risk for recurrent or multidrug-resistant infections and infections that can lead to high morbidity.

- Either approach can be used as a guide, but neither should replace clinical suspicion and judgment in determining the depth of treatment.

Additional reading

Choe HS et al. Summary of the UAA‐AAUS guidelines for urinary tract infections. Int J Urol. 2018 Mar;25(3):175-85. doi:10.1111/iju.13493.

Nicolle LE et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Mar;40(5):643-54. doi: 10.1086/427507.

Wagenlehner FME et al. Epidemiology, definition and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Urol. 2020 Oct;17:586-600. doi:10.1038/s41585-020-0362-4.

Wallace DW et al. Urinalysis: A simple test with complicated interpretation. J Urgent Care Med. 2020 July-Aug;14(10):11-4.

Quiz

A 68-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the emergency department with acute fever, chills, dysuria, frequency, and suprapubic pain. She has associated nausea, malaise, and fatigue. She takes metformin and denies recent antibiotic use. Her temperature is 102.8° F, heart rate 118 beats per minute, blood pressure 118/71 mm Hg, and her respiratory rate is 24 breaths per minute. She is ill-appearing and has mild suprapubic tenderness. White blood cell count is 18 k/mcL. Urinalysis is positive for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and bacteria. Urine microscopy has 120 white blood cells per high power field. What is the most appropriate treatment?

A. Azithromycin

B. Ceftriaxone

C. Cefepime and vancomycin

D. Nitrofurantoin

The answer is B. The patient presents with sepsis secondary to a urinary tract infection. Using the anatomic approach this would be classified as uncomplicated. Using the severity approach, this would be classified as a complicated urinary tract infection. With fever, chills, and signs of sepsis, it’s likely her infection extends beyond the bladder. Given the severity of her presentation, we’d favor treating her as a complicated urinary tract infection with intravenous ceftriaxone. There is no suggestion of resistance or additional MRSA risk factors requiring intravenous vancomycin or cefepime. Nitrofurantoin, although a first-line treatment for uncomplicated cystitis, would not be appropriate if there is suspicion infection extends beyond the bladder. Azithromycin is a first-line option for chlamydia trachomatis, but not a urinary tract infection.

Is ERCP indicated in gallstone pancreatitis without cholangitis?

Background: The timing and need for ERCP in the setting of gallstone pancreatitis without acute cholangitis has been debated widely. Guidelines recommend urgent ERCP for patients with gallstone pancreatitis with concurrent cholangitis, severe cholestasis, or a visualized stone in the duct, but it is unclear if ERCP benefits those with gallstone pancreatitis without those clear indicators.

Study design: Prospective randomized controlled superiority trial.

Setting: 26 hospitals in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of patients with severe gallstone pancreatitis without cholangitis, 232 were randomized 1:1 to undergo urgent ERCP with biliary sphincterotomy (less than 24 hours after presentation) or conservative therapy (analgesia, intravenous fluids, with selective ERCP for cholangitis or persistent cholestasis). The primary endpoint was a composite score of mortality or major complications within 6 months of randomization. There was no difference in the primary endpoint, which occurred in 38% of the urgent-ERCP group and 44% of the conservative-therapy group (P = .37). In a subgroup of patients with cholestasis suggestive of biliary obstruction, the primary endpoint occurred in 32% of the urgent-ERCP group and 42% in the conservative group (P = .18). Similar rates of adverse events were observed between both groups. Limitations included difficulty in diagnosis of cholangitis, moderate positive predictive value of scoring tools to isolate those with severe pancreatitis, and lack of endoscopic ultrasound to determine the presence of ductal stones or sludge.

Bottom line: Conservative management was equal to ERCP with sphincterotomy in patients with severe gallstone pancreatitis without cholangitis, and ERCP may be best reserved for patients with persistent cholestasis or later-developed cholangitis.

Citation: Schepers NJ et al. Urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy versus conservative treatment in predicted severe acute gallstone pancreatitis (APEC): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396:167-76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30539-0.

Dr. Reddy is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and instructor of medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, both in Chicago.

Background: The timing and need for ERCP in the setting of gallstone pancreatitis without acute cholangitis has been debated widely. Guidelines recommend urgent ERCP for patients with gallstone pancreatitis with concurrent cholangitis, severe cholestasis, or a visualized stone in the duct, but it is unclear if ERCP benefits those with gallstone pancreatitis without those clear indicators.

Study design: Prospective randomized controlled superiority trial.

Setting: 26 hospitals in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of patients with severe gallstone pancreatitis without cholangitis, 232 were randomized 1:1 to undergo urgent ERCP with biliary sphincterotomy (less than 24 hours after presentation) or conservative therapy (analgesia, intravenous fluids, with selective ERCP for cholangitis or persistent cholestasis). The primary endpoint was a composite score of mortality or major complications within 6 months of randomization. There was no difference in the primary endpoint, which occurred in 38% of the urgent-ERCP group and 44% of the conservative-therapy group (P = .37). In a subgroup of patients with cholestasis suggestive of biliary obstruction, the primary endpoint occurred in 32% of the urgent-ERCP group and 42% in the conservative group (P = .18). Similar rates of adverse events were observed between both groups. Limitations included difficulty in diagnosis of cholangitis, moderate positive predictive value of scoring tools to isolate those with severe pancreatitis, and lack of endoscopic ultrasound to determine the presence of ductal stones or sludge.

Bottom line: Conservative management was equal to ERCP with sphincterotomy in patients with severe gallstone pancreatitis without cholangitis, and ERCP may be best reserved for patients with persistent cholestasis or later-developed cholangitis.

Citation: Schepers NJ et al. Urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy versus conservative treatment in predicted severe acute gallstone pancreatitis (APEC): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396:167-76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30539-0.

Dr. Reddy is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and instructor of medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, both in Chicago.

Background: The timing and need for ERCP in the setting of gallstone pancreatitis without acute cholangitis has been debated widely. Guidelines recommend urgent ERCP for patients with gallstone pancreatitis with concurrent cholangitis, severe cholestasis, or a visualized stone in the duct, but it is unclear if ERCP benefits those with gallstone pancreatitis without those clear indicators.

Study design: Prospective randomized controlled superiority trial.

Setting: 26 hospitals in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of patients with severe gallstone pancreatitis without cholangitis, 232 were randomized 1:1 to undergo urgent ERCP with biliary sphincterotomy (less than 24 hours after presentation) or conservative therapy (analgesia, intravenous fluids, with selective ERCP for cholangitis or persistent cholestasis). The primary endpoint was a composite score of mortality or major complications within 6 months of randomization. There was no difference in the primary endpoint, which occurred in 38% of the urgent-ERCP group and 44% of the conservative-therapy group (P = .37). In a subgroup of patients with cholestasis suggestive of biliary obstruction, the primary endpoint occurred in 32% of the urgent-ERCP group and 42% in the conservative group (P = .18). Similar rates of adverse events were observed between both groups. Limitations included difficulty in diagnosis of cholangitis, moderate positive predictive value of scoring tools to isolate those with severe pancreatitis, and lack of endoscopic ultrasound to determine the presence of ductal stones or sludge.

Bottom line: Conservative management was equal to ERCP with sphincterotomy in patients with severe gallstone pancreatitis without cholangitis, and ERCP may be best reserved for patients with persistent cholestasis or later-developed cholangitis.

Citation: Schepers NJ et al. Urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy versus conservative treatment in predicted severe acute gallstone pancreatitis (APEC): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396:167-76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30539-0.

Dr. Reddy is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and instructor of medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, both in Chicago.

Timing of renal-replacement therapy for AKI in the ICU

Background: Acute kidney injury (AKI) in the ICU is associated with high mortality. It is hypothesized that earlier initiation of RRT may benefit patients by controlling fluid overload and reducing metabolic stress caused by electrolyte and acid-base imbalances. However, prior studies have been conflicting, with the IDEAL-ICU study (2018) demonstrating no improvement in 90-day mortality with early RRT in septic shock.

Study design: Open-label randomized controlled trial.

Setting: 168 hospitals in 15 countries.

Synopsis: Of ICU patients with severe AKI, 3,019 were randomized to either early or standard initiation of RRT. Early RRT was defined as occurring within 12 hours of eligibility; in the standard-therapy group, RRT was delayed until specifically indicated or if there was no improvement after 72 hours. Those needing immediate renal replacement or deemed likely to recover without need for RRT were excluded in order to study only those in whom ideal timing of dialysis was uncertain. There was no difference in 90-day mortality between the groups (43.9% vs. 43.7%; P = .92). Early initiation did not improve length of ICU stay, ventilator-free days, days out of the hospital, or quality of life. The early-initiation patients experienced more adverse events related to RRT and were more likely to have continued dependence on RRT at 90 days (10.4% vs. 6.0% in standard initiation). Of note, approximately 40% of those randomized to standard initiation never required RRT.

Bottom line: This large, multicenter, well-conducted trial demonstrates no benefit for early initiation of RRT in critically ill patients.

Citation: STARRT-AKI investigators. Timing of initiation of renal-replacement therapy in acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:240-51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000741.

Dr. Lee is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Lurie Children’s Hospital and assistant professor of medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, all in Chicago.

Background: Acute kidney injury (AKI) in the ICU is associated with high mortality. It is hypothesized that earlier initiation of RRT may benefit patients by controlling fluid overload and reducing metabolic stress caused by electrolyte and acid-base imbalances. However, prior studies have been conflicting, with the IDEAL-ICU study (2018) demonstrating no improvement in 90-day mortality with early RRT in septic shock.

Study design: Open-label randomized controlled trial.

Setting: 168 hospitals in 15 countries.

Synopsis: Of ICU patients with severe AKI, 3,019 were randomized to either early or standard initiation of RRT. Early RRT was defined as occurring within 12 hours of eligibility; in the standard-therapy group, RRT was delayed until specifically indicated or if there was no improvement after 72 hours. Those needing immediate renal replacement or deemed likely to recover without need for RRT were excluded in order to study only those in whom ideal timing of dialysis was uncertain. There was no difference in 90-day mortality between the groups (43.9% vs. 43.7%; P = .92). Early initiation did not improve length of ICU stay, ventilator-free days, days out of the hospital, or quality of life. The early-initiation patients experienced more adverse events related to RRT and were more likely to have continued dependence on RRT at 90 days (10.4% vs. 6.0% in standard initiation). Of note, approximately 40% of those randomized to standard initiation never required RRT.

Bottom line: This large, multicenter, well-conducted trial demonstrates no benefit for early initiation of RRT in critically ill patients.

Citation: STARRT-AKI investigators. Timing of initiation of renal-replacement therapy in acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:240-51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000741.

Dr. Lee is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Lurie Children’s Hospital and assistant professor of medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, all in Chicago.

Background: Acute kidney injury (AKI) in the ICU is associated with high mortality. It is hypothesized that earlier initiation of RRT may benefit patients by controlling fluid overload and reducing metabolic stress caused by electrolyte and acid-base imbalances. However, prior studies have been conflicting, with the IDEAL-ICU study (2018) demonstrating no improvement in 90-day mortality with early RRT in septic shock.

Study design: Open-label randomized controlled trial.

Setting: 168 hospitals in 15 countries.

Synopsis: Of ICU patients with severe AKI, 3,019 were randomized to either early or standard initiation of RRT. Early RRT was defined as occurring within 12 hours of eligibility; in the standard-therapy group, RRT was delayed until specifically indicated or if there was no improvement after 72 hours. Those needing immediate renal replacement or deemed likely to recover without need for RRT were excluded in order to study only those in whom ideal timing of dialysis was uncertain. There was no difference in 90-day mortality between the groups (43.9% vs. 43.7%; P = .92). Early initiation did not improve length of ICU stay, ventilator-free days, days out of the hospital, or quality of life. The early-initiation patients experienced more adverse events related to RRT and were more likely to have continued dependence on RRT at 90 days (10.4% vs. 6.0% in standard initiation). Of note, approximately 40% of those randomized to standard initiation never required RRT.

Bottom line: This large, multicenter, well-conducted trial demonstrates no benefit for early initiation of RRT in critically ill patients.

Citation: STARRT-AKI investigators. Timing of initiation of renal-replacement therapy in acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:240-51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000741.

Dr. Lee is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Lurie Children’s Hospital and assistant professor of medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, all in Chicago.

Hospitalists helped plan COVID-19 field hospitals

‘It’s a great thing to be overprepared’

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic’s terrifying first wave in the spring of 2020, dozens of hospitals in high-incidence areas either planned or opened temporary, emergency field hospitals to cover anticipated demand for beds beyond the capacity of local permanent hospitals.

Chastened by images of overwhelmed health care systems in Northern Italy and other hard-hit areas,1 the planners used available modeling tools and estimates for projecting maximum potential need in worst-case scenarios. Some of these temporary hospitals never opened. Others opened in convention centers, parking garages, or parking lot tents, and ended up being used to a lesser degree than the worst-case scenarios.

But those who participated in the planning – including, in many cases, hospitalists – believe they created alternate care site manuals that could be quickly revived in the event of future COVID surges or other, similar crises. Better to plan for too much, they say, than not plan for enough.

Field hospitals or alternate care sites are defined in a recent journal article in Prehospital Disaster Medicine as “locations that can be converted to provide either inpatient and/or outpatient health services when existing facilities are compromised by a hazard impact or the volume of patients exceeds available capacity and/or capabilities.”2

The lead author of that report, Sue Anne Bell, PhD, FNP-BC, a disaster expert and assistant professor of nursing at the University of Michigan (UM), was one of five members of the leadership team for planning UM’s field hospital. They used an organizational unit structure based on the U.S. military’s staffing structure, with their work organized around six units of planning: personnel and labor, security, clinical operations, logistics and supply, planning and training, and communications. This team planned a 519-bed step-down care facility, the Michigan Medicine Field Hospital, for a 73,000-foot indoor track and performance facility at the university, three miles from UM’s main hospital. The aim was to provide safe care in a resource-limited environment.

“We were prepared, but the need never materialized as the peak of COVID cases started to subside,” Dr. Bell said. The team was ready to open within days using a “T-Minus” framework of days remaining on an official countdown clock. But when the need and deadlines kept getting pushed back, that gave them more time to develop clearer procedures.

Two Michigan Medicine hospitalists, Christopher Smith, MD, and David Paje, MD, MPH, both professors at UM’s medical school, were intimately involved in the process. “I was the medical director for the respiratory care unit that was opened for COVID patients, so I was pulled in to assist in the field hospital planning,” said Dr. Smith.

Dr. Paje was director of the short-stay unit and had been a medical officer in the U.S. Army, with training in how to set up military field hospitals. He credits that background as helpful for UM’s COVID field hospital planning, along with his experience in hospital medicine operations.

“We expected that these patients would need the expertise of hospitalists, who had quickly become familiar with the peculiarities of the new disease. That played a role in the decisions we made. Hospitalists were at the front lines of COVID care and had unique clinical insights about managing those with severe disease,” Dr. Paje added.

“When we started, the projections were dire. You don’t want to believe something like that is going to happen. When COVID started to cool off, it was more of a relief to us than anything else,” Dr. Smith said. “Still, it was a very worthwhile exercise. At the end of the day, we put together a comprehensive guide, which is ready for the next crisis.”

Baltimore builds a convention center hospital

A COVID-19 field hospital was planned and executed at an exhibit hall in the Baltimore Convention Center, starting in March 2020 under the leadership of Johns Hopkins Bayview hospitalist Eric Howell, MD, MHM, who eventually handed over responsibilities as chief medical officer when he assumed the position of CEO for the Society of Hospital Medicine in July of that year.

Hopkins collaborated with the University of Maryland health system and state leaders, including the Secretary of Health, to open a 252-bed temporary facility, which at its peak carried a census of 48 patients, with no on-site mortality or cardiac arrests, before it was closed in June 2021 – ready to reopen if necessary. It also served as Baltimore’s major site for polymerase chain reaction COVID-19 testing, vaccinations, and monoclonal antibody infusions, along with medical research.

“My belief at the time we started was that my entire 20-year career as a hospitalist had prepared me for the challenge of opening a COVID field hospital,” Dr. Howell said. “I had learned how to build clinical programs. The difference was that instead of months and years to build a program, we only had a few weeks.”

His first request was to bring on an associate medical director for the field hospital, Melinda E. Kantsiper, MD, a hospitalist and director of clinical operations in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview. She became the field hospital’s CMO when Dr. Howell moved to SHM. “As hospitalists, we are trained to care for the patient in front of us while at the same time creating systems that can adjust to rapidly changing circumstances,” Dr. Kantsiper said. “We did what was asked and set up a field hospital that cared for a total of 1,500 COVID patients.”

Hospitalists have the tools that are needed for this work, and shouldn’t be reluctant to contribute to field hospital planning, she said. “This was a real eye-opener for me. Eric explained to me that hospitalists really practice acute care medicine, which doesn’t have to be within the four walls of a hospital.”

The Baltimore field hospital has been a fantastic experience, Dr. Kantsiper added. “But it’s not a building designed for health care delivery.” For the right group of providers, the experience of working in a temporary facility such as this can be positive and exhilarating. “But we need to make sure we take care of our staff. It takes a toll. How we keep them safe – physically and emotionally – has to be top of mind,” she said.

The leaders at Hopkins Medicine and their collaborators truly engaged with the field hospital’s mission, Dr. Howell added.

“They gave us a lot of autonomy and helped us break down barriers. They gave us the political capital to say proper PPE was absolutely essential. As hard and devastating as the pandemic has been, one take-away is that we showed that we can be more flexible and elastic in response to actual needs than we used to think.”

Range of challenges

Among the questions that need to be answered by a field hospital’s planners, the first is ‘where to put it?’ The answer is, hopefully, someplace not too far away, large enough, with ready access to supplies and intake. The next question is ‘who is the patient?’ Clinicians must determine who goes to the field hospital versus who stays at the standing hospital. How sick should these patients be? And when do they need to go back to the permanent hospital? Can staff be trained to recognize when patients in the field hospital are starting to decompensate? The EPIC Deterioration Index3 is a proprietary prediction model that was used by more than a hundred hospitals during the pandemic.

The hospitalist team may develop specific inclusion and exclusion criteria – for example, don’t admit patients who are receiving oxygen therapy above a certain threshold or who are hemodynamically unstable. These criteria should reflect the capacity of the field hospital and the needs of the permanent hospital. At Michigan, as at other field hospital sites, the goal was to offer a step-down or postacute setting for patients with COVID-19 who were too sick to return home but didn’t need acute or ICU-level care, thereby freeing up beds at the permanent hospital for patients who were sicker.

Other questions: What is the process for admissions and discharges? How will patients be transported? What kind of staffing is needed, and what levels of care will be provided? What about rehabilitation services, or palliative care? What about patients with substance abuse or psychiatric comorbidities?

“Are we going to do paper charting? How will that work out for long-term documentation and billing?” Dr. Bell said. A clear reporting structure and communication pathways are essential. Among the other operational processes to address, outlined in Dr. Bell’s article, are orientation and training, PPE donning and doffing procedures, the code or rapid response team, patient and staff food and nutrition, infection control protocols, pharmacy services, access to radiology, rounding procedures, staff support, and the morgue.

One other issue that shouldn’t be overlooked is health equity in the field hospital. “Providing safe and equitable care should be the focus. Thinking who goes to the field hospital should be done within a health equity framework,” Dr. Bell said.4 She also wonders if field hospital planners are sharing their experience with colleagues across the country and developing more collaborative relationships with other hospitals in their communities.

“Field hospitals can be different things,” Dr. Bell said. “The important take-home is it doesn’t have to be in a tent or a parking garage, which can be suboptimal.” In many cases, it may be better to focus on finding unused space within the hospital – whether a lobby, staff lounge, or unoccupied unit – closer to personnel, supplies, pharmacy, and the like. “I think the pandemic showed us how unprepared we were as a health care system, and how much more we need to do in preparation for future crises.”

Limits to the temporary hospital

In New York City, which had the country’s worst COVID-19 outbreak during the first surge in the spring of 2020, a 1,000-bed field hospital was opened at the Jacob Javits Center in March 2020 and closed that June. “I was in the field hospital early, in March and April, when our hospitals were temporarily overrun,” said hospitalist Mona Krouss, MD, FACP, CPPS, NYC Health + Hospitals’ director of patient safety. “My role was to figure out how to get patients on our medical floors into these field hospitals, with responsibility for helping to revise admission criteria,” she said.

“No one knew how horrible it would become. This was so unanticipated, so difficult to operationalize. What they were able to create was amazing, but there were just too many barriers to have it work smoothly,” Dr. Krouss said.

“The military stepped in, and they helped us so much. We wouldn’t have been able to survive without their help.” But there is only so much a field hospital can do to provide acute medical care. Later, military medical teams shifted to roles in temporary units inside the permanent hospitals. “They came to the hospital wanting to be deployed,” she said.

“We could only send patients [to the field hospital] who were fairly stable, and choosing the right ones was difficult.” Dr. Krouss said. In the end, not a lot of COVID-19 patients from NYC Health + Hospitals ended up going to the Javits Center, in part because the paperwork and logistics of getting someone in was a barrier, Dr. Krouss said. A process was established for referring doctors to call a phone number and speak with a New York City Department of Health employee to go through the criteria for admission to the field hospital.

“That could take up to 30 minutes before getting approval. Then you had to go through the same process all over again for sign-out to another physician, and then register the patient with a special bar code. Then you had to arrange ambulance transfer. Doctors didn’t want to go through all of that – everybody was too busy,” she explained. Hospitalists have since worked on streamlining the criteria. “Now we have a good process for the future. We made it more seamless,” she noted.

Susan Lee, DO, MBA, hospitalist and chief medical officer for Renown Regional Medical Center in Reno, Nev., helped to plan an alternate care site in anticipation of up to a thousand COVID patients in her community – far beyond the scope of the existing hospitals. Hospitalists were involved the entire time in planning, design of the unit, design of staffing models, care protocols, and the like, working through an evidence-based medical committee and a COVID-19 provider task force for the Renown Health System.

“Because of a history of fires and earthquakes in this region, we had an emergency planning infrastructure in place. We put the field hospital on the first and second floors of a parking garage, with built-in negative pressure capacity. We also built space for staff break rooms and desk space. It took 10 days to build the hospital, thanks to some very talented people in management and facility design,” Dr. Lee said.

Then, the hospital was locked up and sat empty for 7 months, until the surge in December 2020, when Reno was hit by a bigger wave – this time exceeding the hospitals’ capacity. Through mid-January of 2021, clinicians cared for approximately 240 COVID-19 patients, up to 47 at a time, in the field hospital. A third wave in the autumn of 2021 plateaued at a level lower than the previous fall, so the field hospital is not currently needed.

Replicating hospital work flows

“We ensured that everybody who needed to be within the walls of the permanent hospitals was able to stay there,” said Dr. Lee’s colleague, hospitalist Adnan (Eddy) Akbar, MD. “The postacute system we ordinarily rely on was no longer accepting patients. Other hospitals in the area were able to manage within their capacity because Renown’s field hospital could admit excess patients. We tried to replicate in the field hospital, as much as possible, the work flows and systems of our main hospital.”

When the field hospital finally opened, Dr. Akbar said, “we had a good feeling. We were ready. If something more catastrophic had come down, we were ready to care for more patients. In the field hospital you have to keep monitoring your work flow – almost on a daily basis. But we felt privileged to be working for a system where you knew you can go and care for everyone who needed care.”

One upside of the field hospital experience for participating clinicians, Dr. Lee added, is the opportunity to practice creatively. “The downside is it’s extremely expensive, and has consequences for the mental health of staff. Like so many of these things, it wore on people over time – such as all the time spent donning and doffing protective equipment. And recently the patients have become a lot less gracious.”