User login

Breaking the glass ceiling in interventional endoscopy: Practical considerations for women

Subspecialty training in advanced endoscopy has become increasingly appealing to GI fellows. The allure of an ever-evolving and innovative field is demonstrated by a substantial increase in the number of training programs over the last 2 decades, from 10 in the year 2000 to over 100 currently.1 Despite its increasing popularity, women interventionalists have been a glaring absence in this phenomenon.

For the 2018-2019 academic year, women represented only 12% of incoming advanced endoscopy fellows who matched through the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) match program. Perhaps more concerning, studies have found that the percentage of female trainees interested in advanced endoscopy diminishes as general GI fellowship progresses.2

Several potential contributors have been cited that elucidate this disparity including work-life balance, radiation exposure, and lack of mentorship.2 Implicit bias also undoubtedly plays a role.

Choosing a career path: Academia vs. private practice

The decision to pursue academia versus private practice in the field of advanced endoscopy is not always straightforward. For a relatively saturated subspecialty, geographic constraints and availability of positions may limit one path or another. Although an interventional practice is best supported by a tertiary care center, there is a known opportunity conflict between the number of advanced endoscopy trainees and the availability of academic positions.3

Although private practice may offer more autonomy in scheduling and fewer nonclinical responsibilities, there may be increased pressure to retain high clinical volumes with direct financial consequences, as well as limitations in overall career advancement. Pursuing an academic path, however, may lead to less flexibility in scheduling, more travel involved with speaking engagements, and teaching and/or research responsibilities disrupting a favorable work-life balance.3 Regardless of career path, the best environment to thrive as an advanced endoscopist and a mother is one in which there is recognition and support of the challenging early family years.

Family planning

Given the long and arduous training, along with the pressures of the early faculty/clinical years, there is no perfect time for a pregnancy. Even when a pregnancy is planned, there is no certainty it will follow the intended course. The challenges specific to a career in advanced endoscopy are not well described.

Considerations during a pregnancy

When to divulge

For female interventionalists, determining when to divulge a pregnancy and the duration of maternity leave can be elusive. There is a fine balance between revealing prematurely given the risk of miscarriage and waiting so long that appropriate precautions are forsaken. One might consider disclosing the pregnancy to a few key personnel in the endoscopy unit and/or a radiation safety officer to optimize early measures to prevent occupational hazards.

Maternity leave

Every institution and practice differ in the details of maternity leave policies. These details should be reviewed and negotiated in advance. At a minimum, they are guided by the federal Family and Medical Leave Act, which entitles employees to 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave.4 Each pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum period is unique and unpredictable. While early planning and consideration of coverage are crucial, it is imperative to be realistic and fluid about the postpartum journey. The unpredictable need for an extended leave has the potential to lead to career stagnancy. It is important to remember that this is a small fraction of time in the context of an entire career.

Fluoroscopy exposure

The exposure to fluoroscopy and potential adverse effects on a pregnancy has been cited frequently by women as a barrier to pursuing advanced endoscopy.2 Given the paucity of women in this field, there has yet to be definitive data on the management of fluoroscopy risk while pregnant. The ASGE Quality Assurance Endoscopy Committee has acknowledged the importance of such data and is currently preparing guidelines for radiation safety that will address the risks for pregnant endoscopists and strategies to minimize fetal exposure. The use of a fetal monitor and an early discussion with the institution’s radiation safety officer are essential to minimize fetal exposure.

Optimizing ergonomics

There have been several publications demonstrating the deleterious musculoskeletal impacts of poor ergonomics while performing endoscopy, with women being at greater risk.5The New Gastroenterologist has also published a primer on this topic. In addition to inadequate education on biomechanics and inconsistent implementation of preventative safeguards, poor endoscope design has been shown to contribute. This can be accentuated for women in advanced endoscopy who perform complex procedures with therapeutic endoscopes equipped with suboptimal handle size and dial placement.

The potential for musculoskeletal injury increases during pregnancy. The standard measures to optimize biomechanics include screen at eye level, bed at hip height, a cushioned mat, and an athletic stance.6 In addition, back injury during pregnancy in advanced endoscopy is not uncommon. Several considerations should be entertained including use of double lead versus standard two-piece 0.5-mm lead with shielding curtains and walls, sitting during procedures when possible, and incorporating short breaks in the endoscopy schedule. Furthermore, more focus and innovation are required from endoscope manufacturers to tailor toward female hand anatomy. Until then, these small but meaningful measures may help to ensure optimal biomechanics to prevent injury.

Breastfeeding/pumping

Breastfeeding in the field of advanced endoscopy has traditionally been challenging. Navigating the collection and storage of breast milk during a busy day of interventional cases can be overwhelming. The previously stagnant industry of electric breast pumps has recently been revolutionized by the innovation of wearable breast pumps. Women are no longer required to find private space to connect to a loud, wired, contraption at least 30 minutes at a time, several times a day. In the context of a busy endoscopy schedule, this antiquated ritual is nearly incompatible with the continuation of breast feeding after returning to work. With relatively silent, wearable breast pumps, it is now possible to continue patient care whether in the clinic or in the endoscopy suite with minimal disruption to a productive day.

Resources

Although there continues to be a void for dedicated mentorship for female interventionalists, there have been many organizational initiatives to unite female gastroenterologists and promote the advancement of women. Several specific initiatives have been particularly effective. Women in Endoscopy (WIE) is a global organization that champions the advancement of women in GI through education, professional growth, and leadership development. In collaboration with the American Gastroenterological Association, they have recently held a virtual event focused on career advancement in the context of unique challenges for women, “Cross Your T’s to Success: How to Deliver a Great Talk, Get Your New Title and Seize Your Next Career Twist.” WIE has also recently launched a webinar series, “Women in Advanced Endoscopy: Fellows Educational Series,” that highlights practicing female interventionalists and illuminating the path to entering the field for trainees. In addition, the ASGE Leadership Education and Development (LEAD) Program has had longstanding success in providing young female gastroenterologists an opportunity to enhance their career advancement skills and facilitate the path to leadership positions. The popularity and success of the LEAD program has led the ASGE to create a special interest group known as ASGE Women in Endoscopy (AWE) with a mission to develop resources for career development during the first 5 years after fellowship. The American College of Gastroenterology also has a unique networking platform for women known as the Women in GI Circle. Furthermore, social media platforms such as Facebook’s Physician Moms Group (PMG) and Ladies of the Gut (LOG; group accessible by invitation only) have proved powerful in connecting female endoscopists and providing a great resource for quick guidance, encouragement, and commiseration. There are also multiple Facebook groups for breastfeeding physicians including Dr. Milk and other pump-specific groups. These online communities have facilitated the dissemination of high-quality resources for troubleshooting and general camaraderie.

Conclusion

Women remain a minority in GI, and especially in advanced endoscopy. Compared with surgical subspecialties that have witnessed substantial progress in the recruitment of women over the past decade, advanced endoscopy seems to be lagging far behind. Recent studies have shown that unified efforts from the surgical societies, such as establishing mentorship programs for trainees, have managed to increase the rates of women in general surgery programs from 14% in 2001 to 40% in 2017.7,8 As the barriers for women entering advanced endoscopy are further understood, the underlying concern of reconciling a challenging field and motherhood has emerged as a common thread. While the practical information presented here cannot overcome the cultural constructs and implicit biases in which women practice advanced endoscopy, the hope is to provide a pragmatic approach to the perceived barriers and promote dialogue among women so that they, too, can pursue and thrive in the field of advanced endoscopy.

References

1. Trindade AJ et al. Characteristics, goals, and motivations of applicants pursuing a fourth-year advanced endoscopy fellowship. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(5):939-44.

2. Pollack MJ et al. Gender disparities and gastroenterology trainee attitudes toward advanced endoscopic training. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(5):1111.

3. Granato CM et al. Career prospects and professional landscape after advanced endoscopy fellowship training: a survey assessing graduates from 2009 to 2013. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84(2):266-71.

4. Family and Medical Leave Act. US Department of Labor. Accessed May 15, 2020. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fmla.

5. Pedrosa MC et al. Minimizing occupational hazards in endoscopy: Personal protective equipment, radiation safety, and ergonomics. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(2):227-35.

6. Singla M et al. Training the endo-athlete: An update in ergonomics in endoscopy. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2018;16(7):1003-6.

7. Aziz HB et al. 2018 ACS Governors Survey: Gender inequality and harassment remain a challenge in surgery. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons. Accessed August 22, 2020. https://bulletin.facs.org/2019/09/2018-acs-governors-survey-gender-inequality-and-harassment-remain-a-challenge-in-surgery/

8. Abelson JS et al. The climb to break the glass ceiling in surgery: trends in women progressing from medical school to surgical training and academic leadership from 1994 to 2015. Am J Surg. 2016;212(4):566-72.e1.

Dr. Hasan is director of interventional endoscopy, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, NorthBay Healthcare Group; Dr. Schulman is an assistant professor, director of bariatric endoscopy, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Subspecialty training in advanced endoscopy has become increasingly appealing to GI fellows. The allure of an ever-evolving and innovative field is demonstrated by a substantial increase in the number of training programs over the last 2 decades, from 10 in the year 2000 to over 100 currently.1 Despite its increasing popularity, women interventionalists have been a glaring absence in this phenomenon.

For the 2018-2019 academic year, women represented only 12% of incoming advanced endoscopy fellows who matched through the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) match program. Perhaps more concerning, studies have found that the percentage of female trainees interested in advanced endoscopy diminishes as general GI fellowship progresses.2

Several potential contributors have been cited that elucidate this disparity including work-life balance, radiation exposure, and lack of mentorship.2 Implicit bias also undoubtedly plays a role.

Choosing a career path: Academia vs. private practice

The decision to pursue academia versus private practice in the field of advanced endoscopy is not always straightforward. For a relatively saturated subspecialty, geographic constraints and availability of positions may limit one path or another. Although an interventional practice is best supported by a tertiary care center, there is a known opportunity conflict between the number of advanced endoscopy trainees and the availability of academic positions.3

Although private practice may offer more autonomy in scheduling and fewer nonclinical responsibilities, there may be increased pressure to retain high clinical volumes with direct financial consequences, as well as limitations in overall career advancement. Pursuing an academic path, however, may lead to less flexibility in scheduling, more travel involved with speaking engagements, and teaching and/or research responsibilities disrupting a favorable work-life balance.3 Regardless of career path, the best environment to thrive as an advanced endoscopist and a mother is one in which there is recognition and support of the challenging early family years.

Family planning

Given the long and arduous training, along with the pressures of the early faculty/clinical years, there is no perfect time for a pregnancy. Even when a pregnancy is planned, there is no certainty it will follow the intended course. The challenges specific to a career in advanced endoscopy are not well described.

Considerations during a pregnancy

When to divulge

For female interventionalists, determining when to divulge a pregnancy and the duration of maternity leave can be elusive. There is a fine balance between revealing prematurely given the risk of miscarriage and waiting so long that appropriate precautions are forsaken. One might consider disclosing the pregnancy to a few key personnel in the endoscopy unit and/or a radiation safety officer to optimize early measures to prevent occupational hazards.

Maternity leave

Every institution and practice differ in the details of maternity leave policies. These details should be reviewed and negotiated in advance. At a minimum, they are guided by the federal Family and Medical Leave Act, which entitles employees to 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave.4 Each pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum period is unique and unpredictable. While early planning and consideration of coverage are crucial, it is imperative to be realistic and fluid about the postpartum journey. The unpredictable need for an extended leave has the potential to lead to career stagnancy. It is important to remember that this is a small fraction of time in the context of an entire career.

Fluoroscopy exposure

The exposure to fluoroscopy and potential adverse effects on a pregnancy has been cited frequently by women as a barrier to pursuing advanced endoscopy.2 Given the paucity of women in this field, there has yet to be definitive data on the management of fluoroscopy risk while pregnant. The ASGE Quality Assurance Endoscopy Committee has acknowledged the importance of such data and is currently preparing guidelines for radiation safety that will address the risks for pregnant endoscopists and strategies to minimize fetal exposure. The use of a fetal monitor and an early discussion with the institution’s radiation safety officer are essential to minimize fetal exposure.

Optimizing ergonomics

There have been several publications demonstrating the deleterious musculoskeletal impacts of poor ergonomics while performing endoscopy, with women being at greater risk.5The New Gastroenterologist has also published a primer on this topic. In addition to inadequate education on biomechanics and inconsistent implementation of preventative safeguards, poor endoscope design has been shown to contribute. This can be accentuated for women in advanced endoscopy who perform complex procedures with therapeutic endoscopes equipped with suboptimal handle size and dial placement.

The potential for musculoskeletal injury increases during pregnancy. The standard measures to optimize biomechanics include screen at eye level, bed at hip height, a cushioned mat, and an athletic stance.6 In addition, back injury during pregnancy in advanced endoscopy is not uncommon. Several considerations should be entertained including use of double lead versus standard two-piece 0.5-mm lead with shielding curtains and walls, sitting during procedures when possible, and incorporating short breaks in the endoscopy schedule. Furthermore, more focus and innovation are required from endoscope manufacturers to tailor toward female hand anatomy. Until then, these small but meaningful measures may help to ensure optimal biomechanics to prevent injury.

Breastfeeding/pumping

Breastfeeding in the field of advanced endoscopy has traditionally been challenging. Navigating the collection and storage of breast milk during a busy day of interventional cases can be overwhelming. The previously stagnant industry of electric breast pumps has recently been revolutionized by the innovation of wearable breast pumps. Women are no longer required to find private space to connect to a loud, wired, contraption at least 30 minutes at a time, several times a day. In the context of a busy endoscopy schedule, this antiquated ritual is nearly incompatible with the continuation of breast feeding after returning to work. With relatively silent, wearable breast pumps, it is now possible to continue patient care whether in the clinic or in the endoscopy suite with minimal disruption to a productive day.

Resources

Although there continues to be a void for dedicated mentorship for female interventionalists, there have been many organizational initiatives to unite female gastroenterologists and promote the advancement of women. Several specific initiatives have been particularly effective. Women in Endoscopy (WIE) is a global organization that champions the advancement of women in GI through education, professional growth, and leadership development. In collaboration with the American Gastroenterological Association, they have recently held a virtual event focused on career advancement in the context of unique challenges for women, “Cross Your T’s to Success: How to Deliver a Great Talk, Get Your New Title and Seize Your Next Career Twist.” WIE has also recently launched a webinar series, “Women in Advanced Endoscopy: Fellows Educational Series,” that highlights practicing female interventionalists and illuminating the path to entering the field for trainees. In addition, the ASGE Leadership Education and Development (LEAD) Program has had longstanding success in providing young female gastroenterologists an opportunity to enhance their career advancement skills and facilitate the path to leadership positions. The popularity and success of the LEAD program has led the ASGE to create a special interest group known as ASGE Women in Endoscopy (AWE) with a mission to develop resources for career development during the first 5 years after fellowship. The American College of Gastroenterology also has a unique networking platform for women known as the Women in GI Circle. Furthermore, social media platforms such as Facebook’s Physician Moms Group (PMG) and Ladies of the Gut (LOG; group accessible by invitation only) have proved powerful in connecting female endoscopists and providing a great resource for quick guidance, encouragement, and commiseration. There are also multiple Facebook groups for breastfeeding physicians including Dr. Milk and other pump-specific groups. These online communities have facilitated the dissemination of high-quality resources for troubleshooting and general camaraderie.

Conclusion

Women remain a minority in GI, and especially in advanced endoscopy. Compared with surgical subspecialties that have witnessed substantial progress in the recruitment of women over the past decade, advanced endoscopy seems to be lagging far behind. Recent studies have shown that unified efforts from the surgical societies, such as establishing mentorship programs for trainees, have managed to increase the rates of women in general surgery programs from 14% in 2001 to 40% in 2017.7,8 As the barriers for women entering advanced endoscopy are further understood, the underlying concern of reconciling a challenging field and motherhood has emerged as a common thread. While the practical information presented here cannot overcome the cultural constructs and implicit biases in which women practice advanced endoscopy, the hope is to provide a pragmatic approach to the perceived barriers and promote dialogue among women so that they, too, can pursue and thrive in the field of advanced endoscopy.

References

1. Trindade AJ et al. Characteristics, goals, and motivations of applicants pursuing a fourth-year advanced endoscopy fellowship. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(5):939-44.

2. Pollack MJ et al. Gender disparities and gastroenterology trainee attitudes toward advanced endoscopic training. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(5):1111.

3. Granato CM et al. Career prospects and professional landscape after advanced endoscopy fellowship training: a survey assessing graduates from 2009 to 2013. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84(2):266-71.

4. Family and Medical Leave Act. US Department of Labor. Accessed May 15, 2020. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fmla.

5. Pedrosa MC et al. Minimizing occupational hazards in endoscopy: Personal protective equipment, radiation safety, and ergonomics. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(2):227-35.

6. Singla M et al. Training the endo-athlete: An update in ergonomics in endoscopy. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2018;16(7):1003-6.

7. Aziz HB et al. 2018 ACS Governors Survey: Gender inequality and harassment remain a challenge in surgery. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons. Accessed August 22, 2020. https://bulletin.facs.org/2019/09/2018-acs-governors-survey-gender-inequality-and-harassment-remain-a-challenge-in-surgery/

8. Abelson JS et al. The climb to break the glass ceiling in surgery: trends in women progressing from medical school to surgical training and academic leadership from 1994 to 2015. Am J Surg. 2016;212(4):566-72.e1.

Dr. Hasan is director of interventional endoscopy, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, NorthBay Healthcare Group; Dr. Schulman is an assistant professor, director of bariatric endoscopy, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Subspecialty training in advanced endoscopy has become increasingly appealing to GI fellows. The allure of an ever-evolving and innovative field is demonstrated by a substantial increase in the number of training programs over the last 2 decades, from 10 in the year 2000 to over 100 currently.1 Despite its increasing popularity, women interventionalists have been a glaring absence in this phenomenon.

For the 2018-2019 academic year, women represented only 12% of incoming advanced endoscopy fellows who matched through the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) match program. Perhaps more concerning, studies have found that the percentage of female trainees interested in advanced endoscopy diminishes as general GI fellowship progresses.2

Several potential contributors have been cited that elucidate this disparity including work-life balance, radiation exposure, and lack of mentorship.2 Implicit bias also undoubtedly plays a role.

Choosing a career path: Academia vs. private practice

The decision to pursue academia versus private practice in the field of advanced endoscopy is not always straightforward. For a relatively saturated subspecialty, geographic constraints and availability of positions may limit one path or another. Although an interventional practice is best supported by a tertiary care center, there is a known opportunity conflict between the number of advanced endoscopy trainees and the availability of academic positions.3

Although private practice may offer more autonomy in scheduling and fewer nonclinical responsibilities, there may be increased pressure to retain high clinical volumes with direct financial consequences, as well as limitations in overall career advancement. Pursuing an academic path, however, may lead to less flexibility in scheduling, more travel involved with speaking engagements, and teaching and/or research responsibilities disrupting a favorable work-life balance.3 Regardless of career path, the best environment to thrive as an advanced endoscopist and a mother is one in which there is recognition and support of the challenging early family years.

Family planning

Given the long and arduous training, along with the pressures of the early faculty/clinical years, there is no perfect time for a pregnancy. Even when a pregnancy is planned, there is no certainty it will follow the intended course. The challenges specific to a career in advanced endoscopy are not well described.

Considerations during a pregnancy

When to divulge

For female interventionalists, determining when to divulge a pregnancy and the duration of maternity leave can be elusive. There is a fine balance between revealing prematurely given the risk of miscarriage and waiting so long that appropriate precautions are forsaken. One might consider disclosing the pregnancy to a few key personnel in the endoscopy unit and/or a radiation safety officer to optimize early measures to prevent occupational hazards.

Maternity leave

Every institution and practice differ in the details of maternity leave policies. These details should be reviewed and negotiated in advance. At a minimum, they are guided by the federal Family and Medical Leave Act, which entitles employees to 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave.4 Each pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum period is unique and unpredictable. While early planning and consideration of coverage are crucial, it is imperative to be realistic and fluid about the postpartum journey. The unpredictable need for an extended leave has the potential to lead to career stagnancy. It is important to remember that this is a small fraction of time in the context of an entire career.

Fluoroscopy exposure

The exposure to fluoroscopy and potential adverse effects on a pregnancy has been cited frequently by women as a barrier to pursuing advanced endoscopy.2 Given the paucity of women in this field, there has yet to be definitive data on the management of fluoroscopy risk while pregnant. The ASGE Quality Assurance Endoscopy Committee has acknowledged the importance of such data and is currently preparing guidelines for radiation safety that will address the risks for pregnant endoscopists and strategies to minimize fetal exposure. The use of a fetal monitor and an early discussion with the institution’s radiation safety officer are essential to minimize fetal exposure.

Optimizing ergonomics

There have been several publications demonstrating the deleterious musculoskeletal impacts of poor ergonomics while performing endoscopy, with women being at greater risk.5The New Gastroenterologist has also published a primer on this topic. In addition to inadequate education on biomechanics and inconsistent implementation of preventative safeguards, poor endoscope design has been shown to contribute. This can be accentuated for women in advanced endoscopy who perform complex procedures with therapeutic endoscopes equipped with suboptimal handle size and dial placement.

The potential for musculoskeletal injury increases during pregnancy. The standard measures to optimize biomechanics include screen at eye level, bed at hip height, a cushioned mat, and an athletic stance.6 In addition, back injury during pregnancy in advanced endoscopy is not uncommon. Several considerations should be entertained including use of double lead versus standard two-piece 0.5-mm lead with shielding curtains and walls, sitting during procedures when possible, and incorporating short breaks in the endoscopy schedule. Furthermore, more focus and innovation are required from endoscope manufacturers to tailor toward female hand anatomy. Until then, these small but meaningful measures may help to ensure optimal biomechanics to prevent injury.

Breastfeeding/pumping

Breastfeeding in the field of advanced endoscopy has traditionally been challenging. Navigating the collection and storage of breast milk during a busy day of interventional cases can be overwhelming. The previously stagnant industry of electric breast pumps has recently been revolutionized by the innovation of wearable breast pumps. Women are no longer required to find private space to connect to a loud, wired, contraption at least 30 minutes at a time, several times a day. In the context of a busy endoscopy schedule, this antiquated ritual is nearly incompatible with the continuation of breast feeding after returning to work. With relatively silent, wearable breast pumps, it is now possible to continue patient care whether in the clinic or in the endoscopy suite with minimal disruption to a productive day.

Resources

Although there continues to be a void for dedicated mentorship for female interventionalists, there have been many organizational initiatives to unite female gastroenterologists and promote the advancement of women. Several specific initiatives have been particularly effective. Women in Endoscopy (WIE) is a global organization that champions the advancement of women in GI through education, professional growth, and leadership development. In collaboration with the American Gastroenterological Association, they have recently held a virtual event focused on career advancement in the context of unique challenges for women, “Cross Your T’s to Success: How to Deliver a Great Talk, Get Your New Title and Seize Your Next Career Twist.” WIE has also recently launched a webinar series, “Women in Advanced Endoscopy: Fellows Educational Series,” that highlights practicing female interventionalists and illuminating the path to entering the field for trainees. In addition, the ASGE Leadership Education and Development (LEAD) Program has had longstanding success in providing young female gastroenterologists an opportunity to enhance their career advancement skills and facilitate the path to leadership positions. The popularity and success of the LEAD program has led the ASGE to create a special interest group known as ASGE Women in Endoscopy (AWE) with a mission to develop resources for career development during the first 5 years after fellowship. The American College of Gastroenterology also has a unique networking platform for women known as the Women in GI Circle. Furthermore, social media platforms such as Facebook’s Physician Moms Group (PMG) and Ladies of the Gut (LOG; group accessible by invitation only) have proved powerful in connecting female endoscopists and providing a great resource for quick guidance, encouragement, and commiseration. There are also multiple Facebook groups for breastfeeding physicians including Dr. Milk and other pump-specific groups. These online communities have facilitated the dissemination of high-quality resources for troubleshooting and general camaraderie.

Conclusion

Women remain a minority in GI, and especially in advanced endoscopy. Compared with surgical subspecialties that have witnessed substantial progress in the recruitment of women over the past decade, advanced endoscopy seems to be lagging far behind. Recent studies have shown that unified efforts from the surgical societies, such as establishing mentorship programs for trainees, have managed to increase the rates of women in general surgery programs from 14% in 2001 to 40% in 2017.7,8 As the barriers for women entering advanced endoscopy are further understood, the underlying concern of reconciling a challenging field and motherhood has emerged as a common thread. While the practical information presented here cannot overcome the cultural constructs and implicit biases in which women practice advanced endoscopy, the hope is to provide a pragmatic approach to the perceived barriers and promote dialogue among women so that they, too, can pursue and thrive in the field of advanced endoscopy.

References

1. Trindade AJ et al. Characteristics, goals, and motivations of applicants pursuing a fourth-year advanced endoscopy fellowship. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(5):939-44.

2. Pollack MJ et al. Gender disparities and gastroenterology trainee attitudes toward advanced endoscopic training. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(5):1111.

3. Granato CM et al. Career prospects and professional landscape after advanced endoscopy fellowship training: a survey assessing graduates from 2009 to 2013. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84(2):266-71.

4. Family and Medical Leave Act. US Department of Labor. Accessed May 15, 2020. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fmla.

5. Pedrosa MC et al. Minimizing occupational hazards in endoscopy: Personal protective equipment, radiation safety, and ergonomics. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(2):227-35.

6. Singla M et al. Training the endo-athlete: An update in ergonomics in endoscopy. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2018;16(7):1003-6.

7. Aziz HB et al. 2018 ACS Governors Survey: Gender inequality and harassment remain a challenge in surgery. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons. Accessed August 22, 2020. https://bulletin.facs.org/2019/09/2018-acs-governors-survey-gender-inequality-and-harassment-remain-a-challenge-in-surgery/

8. Abelson JS et al. The climb to break the glass ceiling in surgery: trends in women progressing from medical school to surgical training and academic leadership from 1994 to 2015. Am J Surg. 2016;212(4):566-72.e1.

Dr. Hasan is director of interventional endoscopy, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, NorthBay Healthcare Group; Dr. Schulman is an assistant professor, director of bariatric endoscopy, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Evaluating a paper: Take care not to be confounded

In an earlier article, we looked at the meaning of the P value.1 This time we will look at another crucial statistical concept: that of confounding.

Confounding, as the name implies, is the recognition that crude associations may not reflect reality, but may instead be the result of outside factors. To illustrate, imagine that you want to study whether smoking increases the risk of death (in statistical terms, smoking is the exposure, and death is the outcome). You follow 5,000 people who smoke and 5,000 people who do not smoke for 10 years. At the end of the follow-up you find that about 40% of nonsmokers died, compared with only 10% of smokers. What do you conclude? At face value it would seem that smoking prevents death. However, before reaching this conclusion you might want to look at other factors. A look at the dataset shows that the average baseline age among nonsmokers was 60 years, whereas among smokers was 40 years. Could this be the cause of the results? You repeat the analysis based on strata of age (i.e., you compare smokers who were aged 60-70 years at baseline with nonsmokers who were aged 60-70 years, smokers who were aged 50-60 years with nonsmokers who were aged 50-60 years, and so on). What you find is that, for each category of age, the percentage of death among smokers was higher. Hence, you now reach the opposite conclusion, namely that smoking does increase the risk of death.

What happened? Why the different result? The answer is that, in this case, age was a confounder. What we initially thought was the effect of smoking was, in reality, at least in part, the effect of age. Overall, more deaths occurred among nonsmokers in the first analysis because they were older at baseline. When we compare people with similar age but who differ on smoking status, then the difference in mortality between them is not because of age (they have the same age) but smoking. Thus, in the second analysis we took age into account, or, in statistical terms, we adjusted for age, whereas the first analysis was, in statistical terms, an unadjusted or crude analysis. We should always be aware of studies with only crude results, because they might be biased/misleading.2

In the example above, age is not the only factor that might influence mortality. Alcohol or drug use, cancer or heart disease, body mass index, or physical activity can also influence death, independently of smoking. How to adjust for all these factors? We cannot do stratified analyses as we did above, because the strata would be too many. The solution is to do a multivariable regression analysis. This is a statistical tool to adjust for multiple factors (or variables) at the same time. When we adjust for all these factors, we are comparing the effect of smoking in people who are the same with regard to all these factors but who differ on smoking status. In statistical terms, we study the effect of smoking, keeping everything else constant. In this way we “isolate” the effect of smoking on death by taking into account all other factors, or, in statistical terms, we study the effect of smoking independently of other factors.

How many factors should be included in a multivariable analysis? As a general rule, the more the better, to reduce confounding. However, the number of variables to include in a regression model is limited by the sample size. The general rule of thumb is that, for every 10 events (for dichotomous outcomes) or 10 people (for continuous outcomes), we can add one variable in the model. If we add more variables than that, then in statistical terms the model becomes overfitted (i.e., it gives results that are specific to that dataset, but may not be applicable to other datasets). Overfitted models can be as biased/misleading as crude models.3

What are we to do about other factors that may affect mortality independently of smoking (e.g., diet), but which are not found in our dataset? Unfortunately, nothing. Since we do not have that information, we cannot adjust for it. In this case, diet is in statistical terms an unmeasured confounder. Unfortunately, in all observational studies there is always at least some degree of unmeasured confounding, because there may be many factors that can influence the outcome (and the exposure) which are not part of the dataset. While some statistical tools have been developed to estimate unmeasured confounding, and therefore interpret the results in its light, unmeasured confounding remains one of the major limitations of observational studies.4

Randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) on the other side do not have this problem in theory. With properly designed RCTs, all confounders, both measured and unmeasured, will be balanced between the two groups. For example, imagine an RCT where some patients are randomized to take drug A or drug B. Because patients are randomly allocated to one group or the other, it is assumed that all other factors are also randomly distributed. Hence, the two groups should be equal to each other with respect to all other factors except our active intervention, namely the type of drug they are taking (A or B). For this reason, in RCTs there is no need to adjust for multiple factors with a multivariable regression analysis, and crude unadjusted results can be presented as unbiased.

There is however a caveat. What happens if one patient who was randomized to take drug A takes drug B instead? Should she still be counted in analysis under drug A (as randomized) or under drug B (as she took it)? The usual practice is to do this and present both. In the first case, we will have the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, and in the second case, the per-protocol analysis (PPA). The advantage of the ITT is that it keeps the strength of randomization, namely the balancing of confounders, and therefore can present unbiased results. The advantage of the PPA is that it measures what was actually done in reality. However, in this case there is a departure from the original randomization, and hence there is the possibility of introducing confounding, because now patients are not randomly allocated to one treatment or the other. The larger the departure from randomization, the more probable the introduction of bias/confounding. For example, what if patients with more severe disease took drug A, even though they were randomized to take drug B? That will have an influence the outcome. For this reason, outcomes of the ITT analysis are considered the main results of RCTs, because PPA results can be confounded.

In summary, when reading studies, do not simply accept the results as they are presented, but rather ask yourself: “Could they be confounded by other factors, and therefore be unreliable? What steps did the authors take to reduce confounding? If they presented only crude analyses, and this was not justified by a RCT design, do they recognize it as a major limitation?” There are many nuances in every paper that can be appreciated only through a careful reading of the methods section. Hopefully, this article can shed some light on these issues and help the readers to not be confounded.

References

1. The P value: What to make of it? A simple guide for the uninitiated. GI and Hepatology News. 2019 Sep 23. https://www.mdedge.com/gihepnews/article/208601/mixed-topics/p-value-what-make-it-simple-guide-uninitiated

2. VanderWeele TJ et al. Ann Stat. 2013 Feb;41(1):196-220.

3. Concato J et al. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Feb 1;118(3):201-10.

4. VanderWeele TJ et al. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Aug 15;167(4):268-74.

Dr. Jovani is a therapeutic endoscopy fellow in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore.

In an earlier article, we looked at the meaning of the P value.1 This time we will look at another crucial statistical concept: that of confounding.

Confounding, as the name implies, is the recognition that crude associations may not reflect reality, but may instead be the result of outside factors. To illustrate, imagine that you want to study whether smoking increases the risk of death (in statistical terms, smoking is the exposure, and death is the outcome). You follow 5,000 people who smoke and 5,000 people who do not smoke for 10 years. At the end of the follow-up you find that about 40% of nonsmokers died, compared with only 10% of smokers. What do you conclude? At face value it would seem that smoking prevents death. However, before reaching this conclusion you might want to look at other factors. A look at the dataset shows that the average baseline age among nonsmokers was 60 years, whereas among smokers was 40 years. Could this be the cause of the results? You repeat the analysis based on strata of age (i.e., you compare smokers who were aged 60-70 years at baseline with nonsmokers who were aged 60-70 years, smokers who were aged 50-60 years with nonsmokers who were aged 50-60 years, and so on). What you find is that, for each category of age, the percentage of death among smokers was higher. Hence, you now reach the opposite conclusion, namely that smoking does increase the risk of death.

What happened? Why the different result? The answer is that, in this case, age was a confounder. What we initially thought was the effect of smoking was, in reality, at least in part, the effect of age. Overall, more deaths occurred among nonsmokers in the first analysis because they were older at baseline. When we compare people with similar age but who differ on smoking status, then the difference in mortality between them is not because of age (they have the same age) but smoking. Thus, in the second analysis we took age into account, or, in statistical terms, we adjusted for age, whereas the first analysis was, in statistical terms, an unadjusted or crude analysis. We should always be aware of studies with only crude results, because they might be biased/misleading.2

In the example above, age is not the only factor that might influence mortality. Alcohol or drug use, cancer or heart disease, body mass index, or physical activity can also influence death, independently of smoking. How to adjust for all these factors? We cannot do stratified analyses as we did above, because the strata would be too many. The solution is to do a multivariable regression analysis. This is a statistical tool to adjust for multiple factors (or variables) at the same time. When we adjust for all these factors, we are comparing the effect of smoking in people who are the same with regard to all these factors but who differ on smoking status. In statistical terms, we study the effect of smoking, keeping everything else constant. In this way we “isolate” the effect of smoking on death by taking into account all other factors, or, in statistical terms, we study the effect of smoking independently of other factors.

How many factors should be included in a multivariable analysis? As a general rule, the more the better, to reduce confounding. However, the number of variables to include in a regression model is limited by the sample size. The general rule of thumb is that, for every 10 events (for dichotomous outcomes) or 10 people (for continuous outcomes), we can add one variable in the model. If we add more variables than that, then in statistical terms the model becomes overfitted (i.e., it gives results that are specific to that dataset, but may not be applicable to other datasets). Overfitted models can be as biased/misleading as crude models.3

What are we to do about other factors that may affect mortality independently of smoking (e.g., diet), but which are not found in our dataset? Unfortunately, nothing. Since we do not have that information, we cannot adjust for it. In this case, diet is in statistical terms an unmeasured confounder. Unfortunately, in all observational studies there is always at least some degree of unmeasured confounding, because there may be many factors that can influence the outcome (and the exposure) which are not part of the dataset. While some statistical tools have been developed to estimate unmeasured confounding, and therefore interpret the results in its light, unmeasured confounding remains one of the major limitations of observational studies.4

Randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) on the other side do not have this problem in theory. With properly designed RCTs, all confounders, both measured and unmeasured, will be balanced between the two groups. For example, imagine an RCT where some patients are randomized to take drug A or drug B. Because patients are randomly allocated to one group or the other, it is assumed that all other factors are also randomly distributed. Hence, the two groups should be equal to each other with respect to all other factors except our active intervention, namely the type of drug they are taking (A or B). For this reason, in RCTs there is no need to adjust for multiple factors with a multivariable regression analysis, and crude unadjusted results can be presented as unbiased.

There is however a caveat. What happens if one patient who was randomized to take drug A takes drug B instead? Should she still be counted in analysis under drug A (as randomized) or under drug B (as she took it)? The usual practice is to do this and present both. In the first case, we will have the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, and in the second case, the per-protocol analysis (PPA). The advantage of the ITT is that it keeps the strength of randomization, namely the balancing of confounders, and therefore can present unbiased results. The advantage of the PPA is that it measures what was actually done in reality. However, in this case there is a departure from the original randomization, and hence there is the possibility of introducing confounding, because now patients are not randomly allocated to one treatment or the other. The larger the departure from randomization, the more probable the introduction of bias/confounding. For example, what if patients with more severe disease took drug A, even though they were randomized to take drug B? That will have an influence the outcome. For this reason, outcomes of the ITT analysis are considered the main results of RCTs, because PPA results can be confounded.

In summary, when reading studies, do not simply accept the results as they are presented, but rather ask yourself: “Could they be confounded by other factors, and therefore be unreliable? What steps did the authors take to reduce confounding? If they presented only crude analyses, and this was not justified by a RCT design, do they recognize it as a major limitation?” There are many nuances in every paper that can be appreciated only through a careful reading of the methods section. Hopefully, this article can shed some light on these issues and help the readers to not be confounded.

References

1. The P value: What to make of it? A simple guide for the uninitiated. GI and Hepatology News. 2019 Sep 23. https://www.mdedge.com/gihepnews/article/208601/mixed-topics/p-value-what-make-it-simple-guide-uninitiated

2. VanderWeele TJ et al. Ann Stat. 2013 Feb;41(1):196-220.

3. Concato J et al. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Feb 1;118(3):201-10.

4. VanderWeele TJ et al. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Aug 15;167(4):268-74.

Dr. Jovani is a therapeutic endoscopy fellow in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore.

In an earlier article, we looked at the meaning of the P value.1 This time we will look at another crucial statistical concept: that of confounding.

Confounding, as the name implies, is the recognition that crude associations may not reflect reality, but may instead be the result of outside factors. To illustrate, imagine that you want to study whether smoking increases the risk of death (in statistical terms, smoking is the exposure, and death is the outcome). You follow 5,000 people who smoke and 5,000 people who do not smoke for 10 years. At the end of the follow-up you find that about 40% of nonsmokers died, compared with only 10% of smokers. What do you conclude? At face value it would seem that smoking prevents death. However, before reaching this conclusion you might want to look at other factors. A look at the dataset shows that the average baseline age among nonsmokers was 60 years, whereas among smokers was 40 years. Could this be the cause of the results? You repeat the analysis based on strata of age (i.e., you compare smokers who were aged 60-70 years at baseline with nonsmokers who were aged 60-70 years, smokers who were aged 50-60 years with nonsmokers who were aged 50-60 years, and so on). What you find is that, for each category of age, the percentage of death among smokers was higher. Hence, you now reach the opposite conclusion, namely that smoking does increase the risk of death.

What happened? Why the different result? The answer is that, in this case, age was a confounder. What we initially thought was the effect of smoking was, in reality, at least in part, the effect of age. Overall, more deaths occurred among nonsmokers in the first analysis because they were older at baseline. When we compare people with similar age but who differ on smoking status, then the difference in mortality between them is not because of age (they have the same age) but smoking. Thus, in the second analysis we took age into account, or, in statistical terms, we adjusted for age, whereas the first analysis was, in statistical terms, an unadjusted or crude analysis. We should always be aware of studies with only crude results, because they might be biased/misleading.2

In the example above, age is not the only factor that might influence mortality. Alcohol or drug use, cancer or heart disease, body mass index, or physical activity can also influence death, independently of smoking. How to adjust for all these factors? We cannot do stratified analyses as we did above, because the strata would be too many. The solution is to do a multivariable regression analysis. This is a statistical tool to adjust for multiple factors (or variables) at the same time. When we adjust for all these factors, we are comparing the effect of smoking in people who are the same with regard to all these factors but who differ on smoking status. In statistical terms, we study the effect of smoking, keeping everything else constant. In this way we “isolate” the effect of smoking on death by taking into account all other factors, or, in statistical terms, we study the effect of smoking independently of other factors.

How many factors should be included in a multivariable analysis? As a general rule, the more the better, to reduce confounding. However, the number of variables to include in a regression model is limited by the sample size. The general rule of thumb is that, for every 10 events (for dichotomous outcomes) or 10 people (for continuous outcomes), we can add one variable in the model. If we add more variables than that, then in statistical terms the model becomes overfitted (i.e., it gives results that are specific to that dataset, but may not be applicable to other datasets). Overfitted models can be as biased/misleading as crude models.3

What are we to do about other factors that may affect mortality independently of smoking (e.g., diet), but which are not found in our dataset? Unfortunately, nothing. Since we do not have that information, we cannot adjust for it. In this case, diet is in statistical terms an unmeasured confounder. Unfortunately, in all observational studies there is always at least some degree of unmeasured confounding, because there may be many factors that can influence the outcome (and the exposure) which are not part of the dataset. While some statistical tools have been developed to estimate unmeasured confounding, and therefore interpret the results in its light, unmeasured confounding remains one of the major limitations of observational studies.4

Randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) on the other side do not have this problem in theory. With properly designed RCTs, all confounders, both measured and unmeasured, will be balanced between the two groups. For example, imagine an RCT where some patients are randomized to take drug A or drug B. Because patients are randomly allocated to one group or the other, it is assumed that all other factors are also randomly distributed. Hence, the two groups should be equal to each other with respect to all other factors except our active intervention, namely the type of drug they are taking (A or B). For this reason, in RCTs there is no need to adjust for multiple factors with a multivariable regression analysis, and crude unadjusted results can be presented as unbiased.

There is however a caveat. What happens if one patient who was randomized to take drug A takes drug B instead? Should she still be counted in analysis under drug A (as randomized) or under drug B (as she took it)? The usual practice is to do this and present both. In the first case, we will have the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, and in the second case, the per-protocol analysis (PPA). The advantage of the ITT is that it keeps the strength of randomization, namely the balancing of confounders, and therefore can present unbiased results. The advantage of the PPA is that it measures what was actually done in reality. However, in this case there is a departure from the original randomization, and hence there is the possibility of introducing confounding, because now patients are not randomly allocated to one treatment or the other. The larger the departure from randomization, the more probable the introduction of bias/confounding. For example, what if patients with more severe disease took drug A, even though they were randomized to take drug B? That will have an influence the outcome. For this reason, outcomes of the ITT analysis are considered the main results of RCTs, because PPA results can be confounded.

In summary, when reading studies, do not simply accept the results as they are presented, but rather ask yourself: “Could they be confounded by other factors, and therefore be unreliable? What steps did the authors take to reduce confounding? If they presented only crude analyses, and this was not justified by a RCT design, do they recognize it as a major limitation?” There are many nuances in every paper that can be appreciated only through a careful reading of the methods section. Hopefully, this article can shed some light on these issues and help the readers to not be confounded.

References

1. The P value: What to make of it? A simple guide for the uninitiated. GI and Hepatology News. 2019 Sep 23. https://www.mdedge.com/gihepnews/article/208601/mixed-topics/p-value-what-make-it-simple-guide-uninitiated

2. VanderWeele TJ et al. Ann Stat. 2013 Feb;41(1):196-220.

3. Concato J et al. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Feb 1;118(3):201-10.

4. VanderWeele TJ et al. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Aug 15;167(4):268-74.

Dr. Jovani is a therapeutic endoscopy fellow in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore.

A practical approach to utilizing cannabis as adjuvant therapy in inflammatory bowel disease

Case 1

A 30 year-old female with longstanding ulcerative colitis who has a history of medically refractory steroid-dependent disease and was able to achieve remission with vedolizumab for the last 5 years. Most recent objective assessment showed histologic remission. She has been using daily cannabis medicinally for the last year (high CBD:THC [cannabidiol:delta-9-tetracannabidol] concentration). She notes that she has felt better in the last year since introducing cannabis (improved stool frequency/formation, sleep quality). She inquires about discontinuing her biologic therapy in the hope of using cannabis alone to maintain remission.

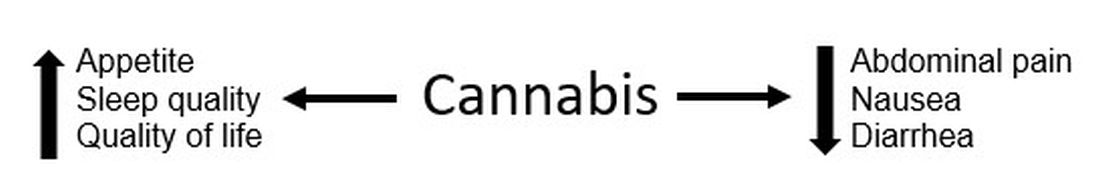

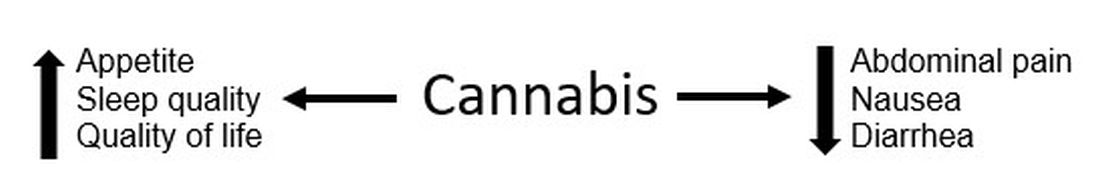

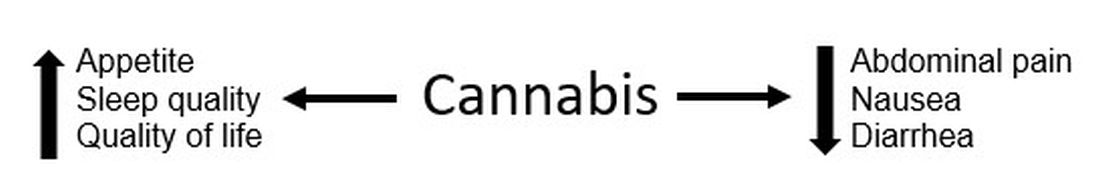

Figure 1.

Case 2

A 22-year-old male with ileocolonic inflammatory Crohn’s disease escalated to adalimumab requiring an intensification of therapy to weekly dosing to normalize C-reactive protein (CRP). A recent colonoscopy showed endoscopic improvement (colonic normalization and rare aphthae in ileum). He notes clear clinical improvement, but he continues to experience diarrhea and abdominal cramping (no relationship to meals). Declines addition of immunomodulator (nervous about returning to college during the COVID-19 pandemic). He wonders whether cannabis could be effective in controlling his symptoms as he has had improvement in symptoms during his sporadic recreational cannabis exposure.

Discussion

These cases outline the challenges that providers face when managing patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) when a patient would like to either substitute or incorporate cannabis into their treatment plan. Studies have shown a high prevalence of cannabis use among patients with IBD. With the restrictions surrounding the use of cannabis – either medically or recreationally – being liberalized in many states, these conversations are likely to become more frequent in your practice. However, one of the first challenges that providers face surrounding cannabis is that many patients who use cannabis do not disclose use to their health care team for fear of being judged negatively. In addition, many providers do not routinely ask about cannabis use during office visits. This might be directly related to being unprepared to have a knowledge-based discussion on the risks and benefits of cannabis use in IBD, with the same confidence present during discussion of biologic therapies.

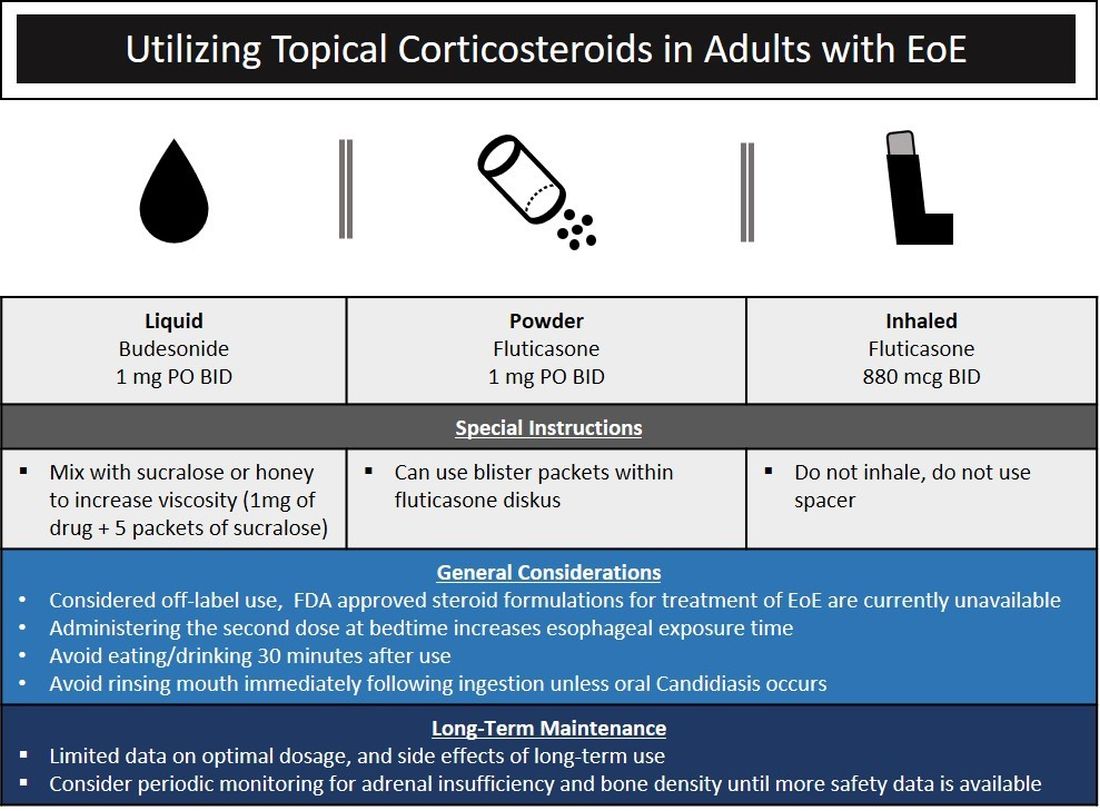

For background, Cannabis sativa (cannabis) is composed of hundreds of phytocannabinoids, the two most common are THC and CBD. These cannabinoids act at the endocannabinoid receptors, which are expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems and immune cells/tissues, and help explain the clinical changes experienced by cannabis users. Both THC and CBD have been studied in varying doses and routes of administration in patients with IBD, making it challenging to translate into real-world recommendations for patients. Some of the most common reported benefits of cannabis use (particularly in an IBD population) are improvement in pain, diarrhea, nausea, and joint pain. Some studies have shown overall improvement in quality of life (Figure 1).

Some common questions that arise surrounding cannabis use in IBD patients include:

1. Is it possible to stop traditional medical therapy and replace it with cannabis therapy?

No studies have directly addressed this exact question. The small studies, both randomized controlled trials and retrospective ones, have studied the effects of cannabis as adjuvant therapy only. None of the data available to date suggest that cannabis has any anti-inflammatory properties with absence of improvement in biomarkers or endoscopic measures of inflammation. In effect, any attempt to discontinue standard therapy with substitution of cannabis-based therapy should be seen as no different than simply discontinuing standard therapy. There exists the argument that – among those with moderate to severe disease – cannabis might suppress the investigation of mild symptoms which may herald a flare of disease, thus lulling the patient into a state of false stability. We do not advocate the substitution of cannabis products in place of standard medical therapy.

2. Is there a role for cannabis as adjuvant therapy in patients with IBD?

Studies to date have included only symptomatic patients with objective evidence of inflammation and assessed clinical, biochemical, or endoscopic endpoints. In Crohn’s disease, two studies showed no improvement in clinical remission rates but showed improvement in clinical response; a third study showed both improvement in clinical remission/response as well as improved quality of life. No study showed a change in disease markers of activity including CRP, fecal calprotectin, or endoscopic scoring. In one study, all patients relapsed shortly after cannabis discontinuation suggesting that, while there was benefit in symptom control, there was no improvement of the underlying chronic inflammation.

In patients with ulcerative colitis, there were two studies. One study showed no improvement and high rates of intolerance in the treatment group, while the other study reported improved disease activity but no objective improvement. The variation in results between disease states and between studies might be because of cannabis formulations. In patients with persistent symptoms despite current medical therapy, there might be a role in those patients for adjuvant therapy for improvement symptom control but not disease control. Optimization of medical therapy would still be indicated.

3. What dose and formulation of cannabis should I recommend to a patient as adjuvant therapy?

This is an excellent question and one that unfortunately we do not have the answer to. As mentioned previously, the studies have looked at varying formulations (THC alone, CBD:THC with varying percentages of THC, CBD alone) and varying routes of administration (sublingual, oral, inhalation). The IBD studies looking at CBD-alone formulations lacked clinical efficacy. In states where cannabis products have been accessible to IBD patients, no data on the product type (THC:CBD), method of administration, or prescriber preferences have been published.

4. What risks should I advise my patients about with cannabis use?

The challenge is that we don’t have large population-based studies in IBD looking at long-term risks of cannabis use. However, in the small RCT studies there were minimal reported side effects and no major adverse events over 8-10 weeks. Larger IBD population-based studies have shown that cannabis users were more likely to discontinue traditional medical therapy, and there is an increased risk for surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. Larger studies in non-IBD patients have shown risk for addiction to other substances, diminished life achievement, increased motor vehicle accidents, chronic bronchitis, psychiatric disturbances and cannabis dependence, and cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (with an uncanny presentation resembling Crohn’s disease flare with partial small bowel obstruction). Patients should also be advised about legal implications of use (given its continued classification as a federal schedule 1 drug), possible drug interactions, and special considerations in pediatric patients (increased risk of addiction), elderly patients (increased risk of neuropsychological effects), and during pregnancy (with national obstetric society guidelines warning against use because of fetal exposure and increased risk of stillbirth).

5. What are the legal implications for providers? Patients?

As of July 2020, cannabis is available for recreational use in 12 states, for medicinal use in 28 states, and illegal in 11 states. So the answer really depends on what state the patient lives in. As a provider who might certify patients (in some medicinal states) or recommend cannabis to patients, you should consider legal and licensing implications. Again, this might vary state to state, and you should also take into account federal status. Providers acting in compliance with state laws are unlikely to have federal consequences. However, remember that malpractice insurance only covers FDA-approved medical therapies. Patients should be advised to consider the potential (although highly unlikely) to face federal prosecution and implications of use for employment, school, camp, or travel, and driving restrictions.

Take home points

- Inquire about cannabis to start the conversation.

- Know your state’s legalization status surrounding cannabis.

- Patients with IBD report improvement in symptoms and quality of life with adjuvant cannabis use; however, there is no change in disease activity.

- Encourage your patients to continue and optimize their maintenance therapy.

- Educate your patients about the legal considerations and known risks.

In conclusion, the use of cannabis in IBD patients has increased in recent years. It is important to be able to discuss the risks and benefits of use with your IBD patients. Focus on the lack of data showing that cannabis improves disease activity, and has shown benefit only in improving IBD-associated symptoms. In some patients there might be a role for adjuvant cannabis therapy to improve overall symptom control and quality of life.

Dr. Kinnucan is an assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Dr. Swaminath is an associate professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Lenox Hill Hospital, Northwell Health, New York.

Case 1

A 30 year-old female with longstanding ulcerative colitis who has a history of medically refractory steroid-dependent disease and was able to achieve remission with vedolizumab for the last 5 years. Most recent objective assessment showed histologic remission. She has been using daily cannabis medicinally for the last year (high CBD:THC [cannabidiol:delta-9-tetracannabidol] concentration). She notes that she has felt better in the last year since introducing cannabis (improved stool frequency/formation, sleep quality). She inquires about discontinuing her biologic therapy in the hope of using cannabis alone to maintain remission.

Figure 1.

Case 2

A 22-year-old male with ileocolonic inflammatory Crohn’s disease escalated to adalimumab requiring an intensification of therapy to weekly dosing to normalize C-reactive protein (CRP). A recent colonoscopy showed endoscopic improvement (colonic normalization and rare aphthae in ileum). He notes clear clinical improvement, but he continues to experience diarrhea and abdominal cramping (no relationship to meals). Declines addition of immunomodulator (nervous about returning to college during the COVID-19 pandemic). He wonders whether cannabis could be effective in controlling his symptoms as he has had improvement in symptoms during his sporadic recreational cannabis exposure.

Discussion

These cases outline the challenges that providers face when managing patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) when a patient would like to either substitute or incorporate cannabis into their treatment plan. Studies have shown a high prevalence of cannabis use among patients with IBD. With the restrictions surrounding the use of cannabis – either medically or recreationally – being liberalized in many states, these conversations are likely to become more frequent in your practice. However, one of the first challenges that providers face surrounding cannabis is that many patients who use cannabis do not disclose use to their health care team for fear of being judged negatively. In addition, many providers do not routinely ask about cannabis use during office visits. This might be directly related to being unprepared to have a knowledge-based discussion on the risks and benefits of cannabis use in IBD, with the same confidence present during discussion of biologic therapies.

For background, Cannabis sativa (cannabis) is composed of hundreds of phytocannabinoids, the two most common are THC and CBD. These cannabinoids act at the endocannabinoid receptors, which are expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems and immune cells/tissues, and help explain the clinical changes experienced by cannabis users. Both THC and CBD have been studied in varying doses and routes of administration in patients with IBD, making it challenging to translate into real-world recommendations for patients. Some of the most common reported benefits of cannabis use (particularly in an IBD population) are improvement in pain, diarrhea, nausea, and joint pain. Some studies have shown overall improvement in quality of life (Figure 1).

Some common questions that arise surrounding cannabis use in IBD patients include:

1. Is it possible to stop traditional medical therapy and replace it with cannabis therapy?

No studies have directly addressed this exact question. The small studies, both randomized controlled trials and retrospective ones, have studied the effects of cannabis as adjuvant therapy only. None of the data available to date suggest that cannabis has any anti-inflammatory properties with absence of improvement in biomarkers or endoscopic measures of inflammation. In effect, any attempt to discontinue standard therapy with substitution of cannabis-based therapy should be seen as no different than simply discontinuing standard therapy. There exists the argument that – among those with moderate to severe disease – cannabis might suppress the investigation of mild symptoms which may herald a flare of disease, thus lulling the patient into a state of false stability. We do not advocate the substitution of cannabis products in place of standard medical therapy.

2. Is there a role for cannabis as adjuvant therapy in patients with IBD?

Studies to date have included only symptomatic patients with objective evidence of inflammation and assessed clinical, biochemical, or endoscopic endpoints. In Crohn’s disease, two studies showed no improvement in clinical remission rates but showed improvement in clinical response; a third study showed both improvement in clinical remission/response as well as improved quality of life. No study showed a change in disease markers of activity including CRP, fecal calprotectin, or endoscopic scoring. In one study, all patients relapsed shortly after cannabis discontinuation suggesting that, while there was benefit in symptom control, there was no improvement of the underlying chronic inflammation.

In patients with ulcerative colitis, there were two studies. One study showed no improvement and high rates of intolerance in the treatment group, while the other study reported improved disease activity but no objective improvement. The variation in results between disease states and between studies might be because of cannabis formulations. In patients with persistent symptoms despite current medical therapy, there might be a role in those patients for adjuvant therapy for improvement symptom control but not disease control. Optimization of medical therapy would still be indicated.

3. What dose and formulation of cannabis should I recommend to a patient as adjuvant therapy?

This is an excellent question and one that unfortunately we do not have the answer to. As mentioned previously, the studies have looked at varying formulations (THC alone, CBD:THC with varying percentages of THC, CBD alone) and varying routes of administration (sublingual, oral, inhalation). The IBD studies looking at CBD-alone formulations lacked clinical efficacy. In states where cannabis products have been accessible to IBD patients, no data on the product type (THC:CBD), method of administration, or prescriber preferences have been published.

4. What risks should I advise my patients about with cannabis use?

The challenge is that we don’t have large population-based studies in IBD looking at long-term risks of cannabis use. However, in the small RCT studies there were minimal reported side effects and no major adverse events over 8-10 weeks. Larger IBD population-based studies have shown that cannabis users were more likely to discontinue traditional medical therapy, and there is an increased risk for surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. Larger studies in non-IBD patients have shown risk for addiction to other substances, diminished life achievement, increased motor vehicle accidents, chronic bronchitis, psychiatric disturbances and cannabis dependence, and cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (with an uncanny presentation resembling Crohn’s disease flare with partial small bowel obstruction). Patients should also be advised about legal implications of use (given its continued classification as a federal schedule 1 drug), possible drug interactions, and special considerations in pediatric patients (increased risk of addiction), elderly patients (increased risk of neuropsychological effects), and during pregnancy (with national obstetric society guidelines warning against use because of fetal exposure and increased risk of stillbirth).

5. What are the legal implications for providers? Patients?

As of July 2020, cannabis is available for recreational use in 12 states, for medicinal use in 28 states, and illegal in 11 states. So the answer really depends on what state the patient lives in. As a provider who might certify patients (in some medicinal states) or recommend cannabis to patients, you should consider legal and licensing implications. Again, this might vary state to state, and you should also take into account federal status. Providers acting in compliance with state laws are unlikely to have federal consequences. However, remember that malpractice insurance only covers FDA-approved medical therapies. Patients should be advised to consider the potential (although highly unlikely) to face federal prosecution and implications of use for employment, school, camp, or travel, and driving restrictions.

Take home points

- Inquire about cannabis to start the conversation.

- Know your state’s legalization status surrounding cannabis.

- Patients with IBD report improvement in symptoms and quality of life with adjuvant cannabis use; however, there is no change in disease activity.

- Encourage your patients to continue and optimize their maintenance therapy.

- Educate your patients about the legal considerations and known risks.

In conclusion, the use of cannabis in IBD patients has increased in recent years. It is important to be able to discuss the risks and benefits of use with your IBD patients. Focus on the lack of data showing that cannabis improves disease activity, and has shown benefit only in improving IBD-associated symptoms. In some patients there might be a role for adjuvant cannabis therapy to improve overall symptom control and quality of life.

Dr. Kinnucan is an assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Dr. Swaminath is an associate professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Lenox Hill Hospital, Northwell Health, New York.

Case 1

A 30 year-old female with longstanding ulcerative colitis who has a history of medically refractory steroid-dependent disease and was able to achieve remission with vedolizumab for the last 5 years. Most recent objective assessment showed histologic remission. She has been using daily cannabis medicinally for the last year (high CBD:THC [cannabidiol:delta-9-tetracannabidol] concentration). She notes that she has felt better in the last year since introducing cannabis (improved stool frequency/formation, sleep quality). She inquires about discontinuing her biologic therapy in the hope of using cannabis alone to maintain remission.

Figure 1.

Case 2

A 22-year-old male with ileocolonic inflammatory Crohn’s disease escalated to adalimumab requiring an intensification of therapy to weekly dosing to normalize C-reactive protein (CRP). A recent colonoscopy showed endoscopic improvement (colonic normalization and rare aphthae in ileum). He notes clear clinical improvement, but he continues to experience diarrhea and abdominal cramping (no relationship to meals). Declines addition of immunomodulator (nervous about returning to college during the COVID-19 pandemic). He wonders whether cannabis could be effective in controlling his symptoms as he has had improvement in symptoms during his sporadic recreational cannabis exposure.

Discussion