User login

Coaching in medicine: A perspective

Coaching is a new topic in medicine. I first heard about coaching several years ago and met the term with skepticism. I was unsure how coaching was different than mentoring or advising and I wondered about its usefulness. However, the reason that I even started to learn about coaching was because I was struggling. I had finally arrived in my career, I had my dream job with two healthy kids, a perfect house, and good marriage. I kept hearing the refrain in my head: “Is this all there is?” I had this arrival fallacy that after all this striving and straining that I would finally be content. I felt unfulfilled and was dissatisfied with where I was that was affecting all parts of my life.

As I was wrestling with these thoughts, I had an opportunity to become a coach to residents around the country through the Association of Women Surgeons. I discussed with them what fills them up, what gets them down, how to set goals, and what their goals were for the year, as well as imposter syndrome. Impostor syndrome is defined as a pattern in which an individual doubts their accomplishments or talents and has a persistent internalized fear of being exposed as a “fraud.” Despite external evidence of their competence, those experiencing this phenomenon remain convinced that they are fooling everyone around them and do not deserve all they have achieved. Individuals incorrectly attribute their success to luck or interpret it as a result of deceiving others into thinking they are more intelligent than they perceive themselves to be. Imposter syndrome is prevalent and deep in medicine. As perfectionists, we are especially vulnerable to imposter syndrome as we set unrealistic ideals for ourselves. When we fail to reach these ideals, we feel like frauds, setting up this cycle of self-doubt that is toxic. When we feel that we can’t achieve the goals that we are striving for we will always find ourselves lacking. There is a slow, insidious erosion of self over the years. Imposter syndrome is well documented in medicine and is even felt as early as medical school.1,2

When I began coaching these residents the most profound thing that came out of these sessions was that my life was getting better – I knew what filled me up, what got me down, what my goals were for the year, and how I still deal with imposter syndrome. Coaching gave me a framework for helping determine what I wanted for the rest of my life. As I began coaching, I started learning all the ways in which I could figure out my values, my personal and professional goals, and perhaps most importantly, my relationships with myself and others.

Another perspective on coaching is to look at a professional athlete such as Tom Brady, one of the greatest quarterbacks of all time. He has a quarterback coach. No coach is going to be a better quarterback than Tom Brady. A coach for him is to be there as an advocate, break his fundamentals down technically, and help him improve upon what he already knows. A coach also identifies strengths and weaknesses, and helps him capitalize on both by bringing awareness, reflection, accountability, and support. If world-class athletes still want and benefit from coaching in a sport they have already mastered, coaching for physicians is just another tool to help us improve our abilities in and out of medicine.

Coaching is more encompassing than advising or mentoring. It is about examining deeply held beliefs to see if they are really serving us, if they are in line with our values and how we want to live our lives.

Coaching has also been validated in medicine in several papers. In an article by Dyrbye et al. in JAMA Internal Medicine, measures of emotional exhaustion and burnout decreased in physicians who were coached and increased in those who were not.3 In another study from this year by McGonagle et al., a randomized, controlled trial showed that primary care physicians who had sessions (as short as 6 weeks) to address burnout, psychological capital, and job satisfaction experienced an improvement in measures which persisted for 6 months after intervention.4 Numerous other articles in medicine also exist to demonstrate the effect of coaching on mitigating burnout at an institutional level.

Physicians are inherently driven by their love of learning. As physicians, we love getting to the root cause of any problem and coming up with creative solutions. Any challenge we have, or just wanting to improve the quality of our lives, can be addressed with coaching. As perpetual students we can use coaching to truly master ourselves.

Dr. Shah is associate professor of surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. Instagram: ami.shahmdcoaching.

References

1. Gottlieb M et al. Med Educ. 2020 Feb;54(2):116-24.

2. Villwock JA et al. Int J Med Educ. 2016 Oct 31;7:364-9.

3. Dyrbye LN et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5;179(10):1406-14.

4. McGonagle AK et al. J Occup Health Psychol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000180.

Coaching is a new topic in medicine. I first heard about coaching several years ago and met the term with skepticism. I was unsure how coaching was different than mentoring or advising and I wondered about its usefulness. However, the reason that I even started to learn about coaching was because I was struggling. I had finally arrived in my career, I had my dream job with two healthy kids, a perfect house, and good marriage. I kept hearing the refrain in my head: “Is this all there is?” I had this arrival fallacy that after all this striving and straining that I would finally be content. I felt unfulfilled and was dissatisfied with where I was that was affecting all parts of my life.

As I was wrestling with these thoughts, I had an opportunity to become a coach to residents around the country through the Association of Women Surgeons. I discussed with them what fills them up, what gets them down, how to set goals, and what their goals were for the year, as well as imposter syndrome. Impostor syndrome is defined as a pattern in which an individual doubts their accomplishments or talents and has a persistent internalized fear of being exposed as a “fraud.” Despite external evidence of their competence, those experiencing this phenomenon remain convinced that they are fooling everyone around them and do not deserve all they have achieved. Individuals incorrectly attribute their success to luck or interpret it as a result of deceiving others into thinking they are more intelligent than they perceive themselves to be. Imposter syndrome is prevalent and deep in medicine. As perfectionists, we are especially vulnerable to imposter syndrome as we set unrealistic ideals for ourselves. When we fail to reach these ideals, we feel like frauds, setting up this cycle of self-doubt that is toxic. When we feel that we can’t achieve the goals that we are striving for we will always find ourselves lacking. There is a slow, insidious erosion of self over the years. Imposter syndrome is well documented in medicine and is even felt as early as medical school.1,2

When I began coaching these residents the most profound thing that came out of these sessions was that my life was getting better – I knew what filled me up, what got me down, what my goals were for the year, and how I still deal with imposter syndrome. Coaching gave me a framework for helping determine what I wanted for the rest of my life. As I began coaching, I started learning all the ways in which I could figure out my values, my personal and professional goals, and perhaps most importantly, my relationships with myself and others.

Another perspective on coaching is to look at a professional athlete such as Tom Brady, one of the greatest quarterbacks of all time. He has a quarterback coach. No coach is going to be a better quarterback than Tom Brady. A coach for him is to be there as an advocate, break his fundamentals down technically, and help him improve upon what he already knows. A coach also identifies strengths and weaknesses, and helps him capitalize on both by bringing awareness, reflection, accountability, and support. If world-class athletes still want and benefit from coaching in a sport they have already mastered, coaching for physicians is just another tool to help us improve our abilities in and out of medicine.

Coaching is more encompassing than advising or mentoring. It is about examining deeply held beliefs to see if they are really serving us, if they are in line with our values and how we want to live our lives.

Coaching has also been validated in medicine in several papers. In an article by Dyrbye et al. in JAMA Internal Medicine, measures of emotional exhaustion and burnout decreased in physicians who were coached and increased in those who were not.3 In another study from this year by McGonagle et al., a randomized, controlled trial showed that primary care physicians who had sessions (as short as 6 weeks) to address burnout, psychological capital, and job satisfaction experienced an improvement in measures which persisted for 6 months after intervention.4 Numerous other articles in medicine also exist to demonstrate the effect of coaching on mitigating burnout at an institutional level.

Physicians are inherently driven by their love of learning. As physicians, we love getting to the root cause of any problem and coming up with creative solutions. Any challenge we have, or just wanting to improve the quality of our lives, can be addressed with coaching. As perpetual students we can use coaching to truly master ourselves.

Dr. Shah is associate professor of surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. Instagram: ami.shahmdcoaching.

References

1. Gottlieb M et al. Med Educ. 2020 Feb;54(2):116-24.

2. Villwock JA et al. Int J Med Educ. 2016 Oct 31;7:364-9.

3. Dyrbye LN et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5;179(10):1406-14.

4. McGonagle AK et al. J Occup Health Psychol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000180.

Coaching is a new topic in medicine. I first heard about coaching several years ago and met the term with skepticism. I was unsure how coaching was different than mentoring or advising and I wondered about its usefulness. However, the reason that I even started to learn about coaching was because I was struggling. I had finally arrived in my career, I had my dream job with two healthy kids, a perfect house, and good marriage. I kept hearing the refrain in my head: “Is this all there is?” I had this arrival fallacy that after all this striving and straining that I would finally be content. I felt unfulfilled and was dissatisfied with where I was that was affecting all parts of my life.

As I was wrestling with these thoughts, I had an opportunity to become a coach to residents around the country through the Association of Women Surgeons. I discussed with them what fills them up, what gets them down, how to set goals, and what their goals were for the year, as well as imposter syndrome. Impostor syndrome is defined as a pattern in which an individual doubts their accomplishments or talents and has a persistent internalized fear of being exposed as a “fraud.” Despite external evidence of their competence, those experiencing this phenomenon remain convinced that they are fooling everyone around them and do not deserve all they have achieved. Individuals incorrectly attribute their success to luck or interpret it as a result of deceiving others into thinking they are more intelligent than they perceive themselves to be. Imposter syndrome is prevalent and deep in medicine. As perfectionists, we are especially vulnerable to imposter syndrome as we set unrealistic ideals for ourselves. When we fail to reach these ideals, we feel like frauds, setting up this cycle of self-doubt that is toxic. When we feel that we can’t achieve the goals that we are striving for we will always find ourselves lacking. There is a slow, insidious erosion of self over the years. Imposter syndrome is well documented in medicine and is even felt as early as medical school.1,2

When I began coaching these residents the most profound thing that came out of these sessions was that my life was getting better – I knew what filled me up, what got me down, what my goals were for the year, and how I still deal with imposter syndrome. Coaching gave me a framework for helping determine what I wanted for the rest of my life. As I began coaching, I started learning all the ways in which I could figure out my values, my personal and professional goals, and perhaps most importantly, my relationships with myself and others.

Another perspective on coaching is to look at a professional athlete such as Tom Brady, one of the greatest quarterbacks of all time. He has a quarterback coach. No coach is going to be a better quarterback than Tom Brady. A coach for him is to be there as an advocate, break his fundamentals down technically, and help him improve upon what he already knows. A coach also identifies strengths and weaknesses, and helps him capitalize on both by bringing awareness, reflection, accountability, and support. If world-class athletes still want and benefit from coaching in a sport they have already mastered, coaching for physicians is just another tool to help us improve our abilities in and out of medicine.

Coaching is more encompassing than advising or mentoring. It is about examining deeply held beliefs to see if they are really serving us, if they are in line with our values and how we want to live our lives.

Coaching has also been validated in medicine in several papers. In an article by Dyrbye et al. in JAMA Internal Medicine, measures of emotional exhaustion and burnout decreased in physicians who were coached and increased in those who were not.3 In another study from this year by McGonagle et al., a randomized, controlled trial showed that primary care physicians who had sessions (as short as 6 weeks) to address burnout, psychological capital, and job satisfaction experienced an improvement in measures which persisted for 6 months after intervention.4 Numerous other articles in medicine also exist to demonstrate the effect of coaching on mitigating burnout at an institutional level.

Physicians are inherently driven by their love of learning. As physicians, we love getting to the root cause of any problem and coming up with creative solutions. Any challenge we have, or just wanting to improve the quality of our lives, can be addressed with coaching. As perpetual students we can use coaching to truly master ourselves.

Dr. Shah is associate professor of surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. Instagram: ami.shahmdcoaching.

References

1. Gottlieb M et al. Med Educ. 2020 Feb;54(2):116-24.

2. Villwock JA et al. Int J Med Educ. 2016 Oct 31;7:364-9.

3. Dyrbye LN et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5;179(10):1406-14.

4. McGonagle AK et al. J Occup Health Psychol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000180.

Understand the legal implications of telehealth medicine

Telehealth has been steadily gaining mainstream use throughout the last decade, but the practice was recently shoved, almost overnight, into the forefront of the health care profession. Telehealth is now used more frequently by medical groups and physicians than ever before. General reports before the COVID-19 pandemic approximated 90% of health care organizations used or planned to use telehealth in the future. This future may already be a reality, with a McKinsey & Company report estimating that physicians saw 50-175 times more patients over telehealth platforms since the pandemic’s start.1

In general, telehealth includes use of electronic communication and information technologies to deliver long-distance or remote health care. A physician’s use of telemedicine (clinical services) is one of the most common uses, but the industry also includes other professionals, such as pharmacists and nurses.

Telehealth platforms can be used to monitor, diagnose, treat, and counsel patients successfully. It works best for reading images, follow-up care, outpatient care, and long-term care. However, telemedicine is inappropriate for urgent issues, diagnosing underlying health conditions, or any practice where the standard of care would require a physical exam. There is potential liability for decision making without a proper physical exam.

There are many advantages to telehealth over more traditional health care options. Some of these advantages include:

- Increased access to health care.

- Increased access to medical specialists in small and rural communities.

- Improved long-term care from the comfort of patients’ homes.

- Improved platforms to document patient care outside regular business hours.

But along with these benefits, telehealth carries the disadvantage of potential increased liability. This increased liability could stem from:

- Breached standards of care.

- Inadequate or improper licensing.

- Limited care options.

- Decision making without a proper physical exam.

- Increased informed consent requirements.

- Restricted prescription access.

Before expanding any practice into telemedicine, awareness of potential legal issues is crucial.

Standard of care

Currently, telehealth laws and regulations vary significantly from state to state. But one rule is consistent across the board – that the standard of care for practicing medicine through telemedicine is identical to the standard of care required for practicing medicine during physical practice. It still requires the appropriate examination, testing, labs, imaging, and consultations that any in-person diagnosis needs. For physicians, it also includes supervising nonphysician clinicians, where state law requires supervision.

The American Telemedicine Association currently determines the primary governing standards and guidelines for telemedicine. These can help physicians understand best practices in meeting the standard of care through telemedicine. The American Gastroenterological Association provides coding guidelines and other resources to help physicians with telehealth and e-visits. Other professional societies, such as the American College of Radiology and the American Academy of Dermatology, offer guidelines specific to their medical specialties’ standards of care. These standards still vary from state to state, so medical professionals must be aware of any differences before treating patients in multiple states.

Licensing

Licensing is one of telemedicine’s most confusing legal issues. All states require a license to practice medicine (traditional or telehealth) within their borders. Without that license, practicing medicine in the state is a crime. On top of being criminal, unlicensed practice can affect insurance, liability, billing, and malpractice coverage. When in a brick-and-mortar clinic, a physician’s confidence in practicing within the licensed jurisdiction is easy. Now, the distinction is not so clear. Patients and physicians no longer have to be in the same room, city, or even state, meaning there could be unknown conflicting laws between the two locations. With rare exceptions, standards of care are based on the patient’s location, not the physician’s location. This increases the risk of practicing without being correctly licensed to higher than ever.

Because licensing is a significant roadblock in providing telemedicine, efforts are underway to make the process simpler and more streamlined. The Federation of State Medical Boards developed the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC).2 This can qualify physicians to practice medicine across state lines within the compact so long as they meet specific eligibility requirements. The IMLC creates a fast-track option for physicians to fill out one application and receive licenses from multiple states at once. Currently, the compact includes 32 states, the District of Columbia, and Guam.3

Informed consent

Telemedicine health care still requires informed consent from patients. In fact, in some states, the requirements for care provided through telehealth are actually stricter than requirements for informed consent obtained in person.

Most informed consent laws require physicians to cover the risks and benefits of a recommended course of treatment and all feasible and reasonable material alternatives. On top of this traditional informed consent, physicians must get additional consent to receive care over a telehealth platform. This unique requirement explains what telehealth is, possible risks and expected benefits, and security measures used to protect patient information. States vary regarding when verbal consent is sufficient, and when written consent is required.

Prescriptions

Telemedicine is still a relatively new industry, and few legal opinions specifically address telemedicine malpractice. However, prescribing medication based on telemedicine information is among the few issues the courts have addressed. A 2008 decision found that a physician review of patient questionnaires submitted over the Internet was insufficient to prescribe medication without a physical examination determining patient health.4 This cautious approach stemmed from telehealth’s early concern about the absence of patient-physician relationships and potential online pharmacy abuse. Since this decision, many states require an “in-person” visit with a patient before prescribing medication. The definition of what qualifies as an in-person visit varies from state to state – some still consider the use of real-time, audiovisual conferencing sufficient.

The law is still evolving for prescriptions. Some states don’t allow any prescriptions, while others allow physicians to prescribe their patients’ medications as part of an appropriate treatment plan according to their professional discretion. Almost every state prohibits the prescription of controlled substances based on telemedicine.

Conclusion

Telemedicine is becoming an increasingly significant part of both physician-patient relationships and the broader health care industry. Used appropriately, it can be an incredibly effective method of care for physicians and patients. Physicians should learn the laws governing telemedicine in every state they want to practice and continue to stay current on any changes. The Center for Connected Health Policy offers a report, updated semiannually, to help physicians stay up to date on their state laws. These efforts will help prevent physicians from exposure to liability and medical malpractice claims.

Mr. Hyde is a partner at Younker Hyde Macfarlane, a law firm that focuses on prosecuting medical malpractice claims on behalf of injured patients. Ms. Johnson is an associate attorney with the firm. You can find them at YHMLaw.com.

References

1. Bestsennyy O, Harris A, Rost J. Telehealth: A quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? Mckinsey & Company, May 29, 2020.

2. FSMB: Draft Interstate Compact for Physician Licensure Nears Completion, 2014.

3. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact: U.S. State Participation in the Compact.

4. See, Low Cost Pharm., Inc. v. Ariz. State Bd. Of Pharm, 2008 Ariz. App. Unpub. LEXIS 790, referencing conclusion of Arizona Medical Board.

Telehealth has been steadily gaining mainstream use throughout the last decade, but the practice was recently shoved, almost overnight, into the forefront of the health care profession. Telehealth is now used more frequently by medical groups and physicians than ever before. General reports before the COVID-19 pandemic approximated 90% of health care organizations used or planned to use telehealth in the future. This future may already be a reality, with a McKinsey & Company report estimating that physicians saw 50-175 times more patients over telehealth platforms since the pandemic’s start.1

In general, telehealth includes use of electronic communication and information technologies to deliver long-distance or remote health care. A physician’s use of telemedicine (clinical services) is one of the most common uses, but the industry also includes other professionals, such as pharmacists and nurses.

Telehealth platforms can be used to monitor, diagnose, treat, and counsel patients successfully. It works best for reading images, follow-up care, outpatient care, and long-term care. However, telemedicine is inappropriate for urgent issues, diagnosing underlying health conditions, or any practice where the standard of care would require a physical exam. There is potential liability for decision making without a proper physical exam.

There are many advantages to telehealth over more traditional health care options. Some of these advantages include:

- Increased access to health care.

- Increased access to medical specialists in small and rural communities.

- Improved long-term care from the comfort of patients’ homes.

- Improved platforms to document patient care outside regular business hours.

But along with these benefits, telehealth carries the disadvantage of potential increased liability. This increased liability could stem from:

- Breached standards of care.

- Inadequate or improper licensing.

- Limited care options.

- Decision making without a proper physical exam.

- Increased informed consent requirements.

- Restricted prescription access.

Before expanding any practice into telemedicine, awareness of potential legal issues is crucial.

Standard of care

Currently, telehealth laws and regulations vary significantly from state to state. But one rule is consistent across the board – that the standard of care for practicing medicine through telemedicine is identical to the standard of care required for practicing medicine during physical practice. It still requires the appropriate examination, testing, labs, imaging, and consultations that any in-person diagnosis needs. For physicians, it also includes supervising nonphysician clinicians, where state law requires supervision.

The American Telemedicine Association currently determines the primary governing standards and guidelines for telemedicine. These can help physicians understand best practices in meeting the standard of care through telemedicine. The American Gastroenterological Association provides coding guidelines and other resources to help physicians with telehealth and e-visits. Other professional societies, such as the American College of Radiology and the American Academy of Dermatology, offer guidelines specific to their medical specialties’ standards of care. These standards still vary from state to state, so medical professionals must be aware of any differences before treating patients in multiple states.

Licensing

Licensing is one of telemedicine’s most confusing legal issues. All states require a license to practice medicine (traditional or telehealth) within their borders. Without that license, practicing medicine in the state is a crime. On top of being criminal, unlicensed practice can affect insurance, liability, billing, and malpractice coverage. When in a brick-and-mortar clinic, a physician’s confidence in practicing within the licensed jurisdiction is easy. Now, the distinction is not so clear. Patients and physicians no longer have to be in the same room, city, or even state, meaning there could be unknown conflicting laws between the two locations. With rare exceptions, standards of care are based on the patient’s location, not the physician’s location. This increases the risk of practicing without being correctly licensed to higher than ever.

Because licensing is a significant roadblock in providing telemedicine, efforts are underway to make the process simpler and more streamlined. The Federation of State Medical Boards developed the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC).2 This can qualify physicians to practice medicine across state lines within the compact so long as they meet specific eligibility requirements. The IMLC creates a fast-track option for physicians to fill out one application and receive licenses from multiple states at once. Currently, the compact includes 32 states, the District of Columbia, and Guam.3

Informed consent

Telemedicine health care still requires informed consent from patients. In fact, in some states, the requirements for care provided through telehealth are actually stricter than requirements for informed consent obtained in person.

Most informed consent laws require physicians to cover the risks and benefits of a recommended course of treatment and all feasible and reasonable material alternatives. On top of this traditional informed consent, physicians must get additional consent to receive care over a telehealth platform. This unique requirement explains what telehealth is, possible risks and expected benefits, and security measures used to protect patient information. States vary regarding when verbal consent is sufficient, and when written consent is required.

Prescriptions

Telemedicine is still a relatively new industry, and few legal opinions specifically address telemedicine malpractice. However, prescribing medication based on telemedicine information is among the few issues the courts have addressed. A 2008 decision found that a physician review of patient questionnaires submitted over the Internet was insufficient to prescribe medication without a physical examination determining patient health.4 This cautious approach stemmed from telehealth’s early concern about the absence of patient-physician relationships and potential online pharmacy abuse. Since this decision, many states require an “in-person” visit with a patient before prescribing medication. The definition of what qualifies as an in-person visit varies from state to state – some still consider the use of real-time, audiovisual conferencing sufficient.

The law is still evolving for prescriptions. Some states don’t allow any prescriptions, while others allow physicians to prescribe their patients’ medications as part of an appropriate treatment plan according to their professional discretion. Almost every state prohibits the prescription of controlled substances based on telemedicine.

Conclusion

Telemedicine is becoming an increasingly significant part of both physician-patient relationships and the broader health care industry. Used appropriately, it can be an incredibly effective method of care for physicians and patients. Physicians should learn the laws governing telemedicine in every state they want to practice and continue to stay current on any changes. The Center for Connected Health Policy offers a report, updated semiannually, to help physicians stay up to date on their state laws. These efforts will help prevent physicians from exposure to liability and medical malpractice claims.

Mr. Hyde is a partner at Younker Hyde Macfarlane, a law firm that focuses on prosecuting medical malpractice claims on behalf of injured patients. Ms. Johnson is an associate attorney with the firm. You can find them at YHMLaw.com.

References

1. Bestsennyy O, Harris A, Rost J. Telehealth: A quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? Mckinsey & Company, May 29, 2020.

2. FSMB: Draft Interstate Compact for Physician Licensure Nears Completion, 2014.

3. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact: U.S. State Participation in the Compact.

4. See, Low Cost Pharm., Inc. v. Ariz. State Bd. Of Pharm, 2008 Ariz. App. Unpub. LEXIS 790, referencing conclusion of Arizona Medical Board.

Telehealth has been steadily gaining mainstream use throughout the last decade, but the practice was recently shoved, almost overnight, into the forefront of the health care profession. Telehealth is now used more frequently by medical groups and physicians than ever before. General reports before the COVID-19 pandemic approximated 90% of health care organizations used or planned to use telehealth in the future. This future may already be a reality, with a McKinsey & Company report estimating that physicians saw 50-175 times more patients over telehealth platforms since the pandemic’s start.1

In general, telehealth includes use of electronic communication and information technologies to deliver long-distance or remote health care. A physician’s use of telemedicine (clinical services) is one of the most common uses, but the industry also includes other professionals, such as pharmacists and nurses.

Telehealth platforms can be used to monitor, diagnose, treat, and counsel patients successfully. It works best for reading images, follow-up care, outpatient care, and long-term care. However, telemedicine is inappropriate for urgent issues, diagnosing underlying health conditions, or any practice where the standard of care would require a physical exam. There is potential liability for decision making without a proper physical exam.

There are many advantages to telehealth over more traditional health care options. Some of these advantages include:

- Increased access to health care.

- Increased access to medical specialists in small and rural communities.

- Improved long-term care from the comfort of patients’ homes.

- Improved platforms to document patient care outside regular business hours.

But along with these benefits, telehealth carries the disadvantage of potential increased liability. This increased liability could stem from:

- Breached standards of care.

- Inadequate or improper licensing.

- Limited care options.

- Decision making without a proper physical exam.

- Increased informed consent requirements.

- Restricted prescription access.

Before expanding any practice into telemedicine, awareness of potential legal issues is crucial.

Standard of care

Currently, telehealth laws and regulations vary significantly from state to state. But one rule is consistent across the board – that the standard of care for practicing medicine through telemedicine is identical to the standard of care required for practicing medicine during physical practice. It still requires the appropriate examination, testing, labs, imaging, and consultations that any in-person diagnosis needs. For physicians, it also includes supervising nonphysician clinicians, where state law requires supervision.

The American Telemedicine Association currently determines the primary governing standards and guidelines for telemedicine. These can help physicians understand best practices in meeting the standard of care through telemedicine. The American Gastroenterological Association provides coding guidelines and other resources to help physicians with telehealth and e-visits. Other professional societies, such as the American College of Radiology and the American Academy of Dermatology, offer guidelines specific to their medical specialties’ standards of care. These standards still vary from state to state, so medical professionals must be aware of any differences before treating patients in multiple states.

Licensing

Licensing is one of telemedicine’s most confusing legal issues. All states require a license to practice medicine (traditional or telehealth) within their borders. Without that license, practicing medicine in the state is a crime. On top of being criminal, unlicensed practice can affect insurance, liability, billing, and malpractice coverage. When in a brick-and-mortar clinic, a physician’s confidence in practicing within the licensed jurisdiction is easy. Now, the distinction is not so clear. Patients and physicians no longer have to be in the same room, city, or even state, meaning there could be unknown conflicting laws between the two locations. With rare exceptions, standards of care are based on the patient’s location, not the physician’s location. This increases the risk of practicing without being correctly licensed to higher than ever.

Because licensing is a significant roadblock in providing telemedicine, efforts are underway to make the process simpler and more streamlined. The Federation of State Medical Boards developed the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC).2 This can qualify physicians to practice medicine across state lines within the compact so long as they meet specific eligibility requirements. The IMLC creates a fast-track option for physicians to fill out one application and receive licenses from multiple states at once. Currently, the compact includes 32 states, the District of Columbia, and Guam.3

Informed consent

Telemedicine health care still requires informed consent from patients. In fact, in some states, the requirements for care provided through telehealth are actually stricter than requirements for informed consent obtained in person.

Most informed consent laws require physicians to cover the risks and benefits of a recommended course of treatment and all feasible and reasonable material alternatives. On top of this traditional informed consent, physicians must get additional consent to receive care over a telehealth platform. This unique requirement explains what telehealth is, possible risks and expected benefits, and security measures used to protect patient information. States vary regarding when verbal consent is sufficient, and when written consent is required.

Prescriptions

Telemedicine is still a relatively new industry, and few legal opinions specifically address telemedicine malpractice. However, prescribing medication based on telemedicine information is among the few issues the courts have addressed. A 2008 decision found that a physician review of patient questionnaires submitted over the Internet was insufficient to prescribe medication without a physical examination determining patient health.4 This cautious approach stemmed from telehealth’s early concern about the absence of patient-physician relationships and potential online pharmacy abuse. Since this decision, many states require an “in-person” visit with a patient before prescribing medication. The definition of what qualifies as an in-person visit varies from state to state – some still consider the use of real-time, audiovisual conferencing sufficient.

The law is still evolving for prescriptions. Some states don’t allow any prescriptions, while others allow physicians to prescribe their patients’ medications as part of an appropriate treatment plan according to their professional discretion. Almost every state prohibits the prescription of controlled substances based on telemedicine.

Conclusion

Telemedicine is becoming an increasingly significant part of both physician-patient relationships and the broader health care industry. Used appropriately, it can be an incredibly effective method of care for physicians and patients. Physicians should learn the laws governing telemedicine in every state they want to practice and continue to stay current on any changes. The Center for Connected Health Policy offers a report, updated semiannually, to help physicians stay up to date on their state laws. These efforts will help prevent physicians from exposure to liability and medical malpractice claims.

Mr. Hyde is a partner at Younker Hyde Macfarlane, a law firm that focuses on prosecuting medical malpractice claims on behalf of injured patients. Ms. Johnson is an associate attorney with the firm. You can find them at YHMLaw.com.

References

1. Bestsennyy O, Harris A, Rost J. Telehealth: A quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? Mckinsey & Company, May 29, 2020.

2. FSMB: Draft Interstate Compact for Physician Licensure Nears Completion, 2014.

3. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact: U.S. State Participation in the Compact.

4. See, Low Cost Pharm., Inc. v. Ariz. State Bd. Of Pharm, 2008 Ariz. App. Unpub. LEXIS 790, referencing conclusion of Arizona Medical Board.

Web-based interviews, financial planning in a pandemic, and more

Dear colleagues,

I’m excited to introduce the November issue of The New Gastroenterologist – the last edition of 2020 features a fantastic line-up of articles! As the year comes to a close, we reflect on what has certainly been an interesting year, defined by a set of unique challenges we have faced as a nation and as a specialty.

The fellowship recruitment season is one that has looked starkly different as interviews have converted to a virtual format. Dr. Wissam Khan, Dr. Nada Al Masalmeh, Dr. Stephanie Judd, and Dr. Diane Levine (Wayne State University) compile a helpful list of tips and tricks on proper interview etiquette in the new era of web-based interviews.

Financial planning in the face of a pandemic is a formidable task – Jonathan Tudor (Fidelity Investments) offers valuable advice for gastroenterologists on how to remain secure in your finances even in uncertain circumstances.

This quarter’s “In Focus” feature, written by Dr. Yutaka Tomizawa (University of Washington), is a comprehensive piece elucidating the role of gastroenterologists in the management of gastric cancer. The article reviews the individual risk factors that exist for gastric cancer and provides guidance on how to stratify patients accordingly, which is critical in the ethnically diverse population of the United States.

Keeping a procedure log during fellowship can seem daunting and cumbersome, but it is important. Dr. Houman Rezaizadeh (University of Connecticut) shares his program’s experience with the AGA Procedure Log, a convenient online tracking tool, which can provide accurate and secure documentation of endoscopic procedures performed throughout fellowship.

Dr. Nazia Hasan (North Bay Health Care) and Dr. Allison Schulman (University of Michigan) broach an incredibly important topic: the paucity of women in interventional endoscopy. Dr. Hasan and Dr. Shulman candidly discuss the barriers women face in pursuing this subspecialty and offer practical solutions on how to approach these challenges – a piece that will surely resonate with many young gastroenterologists.

We wrap up our first year of TNG’s ethics series with two cases discussing the utilization of cannabis therapy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Dr. Jami Kinnucan (University of Michigan) and Dr. Arun Swaminath (Lenox Hill Hospital) systematically review existing data on the efficacy of cannabis use in IBD, the risks associated with therapy, and legal implications for both physicians and patients.

Also in this issue is a high-yield clinical review on the endoscopic drainage of pancreatic fluid collections by Dr. Robert Moran and Dr. Joseph Elmunzer (Medical University of South Carolina). Dr. Manol Jovani (Johns Hopkins) teaches us about confounding – a critical concept to keep in mind when evaluating any manuscript. Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. Mehul Lalani (US Digestive), reviews how quality measures and initiatives are tracked and implemented in private practice.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Dear colleagues,

I’m excited to introduce the November issue of The New Gastroenterologist – the last edition of 2020 features a fantastic line-up of articles! As the year comes to a close, we reflect on what has certainly been an interesting year, defined by a set of unique challenges we have faced as a nation and as a specialty.

The fellowship recruitment season is one that has looked starkly different as interviews have converted to a virtual format. Dr. Wissam Khan, Dr. Nada Al Masalmeh, Dr. Stephanie Judd, and Dr. Diane Levine (Wayne State University) compile a helpful list of tips and tricks on proper interview etiquette in the new era of web-based interviews.

Financial planning in the face of a pandemic is a formidable task – Jonathan Tudor (Fidelity Investments) offers valuable advice for gastroenterologists on how to remain secure in your finances even in uncertain circumstances.

This quarter’s “In Focus” feature, written by Dr. Yutaka Tomizawa (University of Washington), is a comprehensive piece elucidating the role of gastroenterologists in the management of gastric cancer. The article reviews the individual risk factors that exist for gastric cancer and provides guidance on how to stratify patients accordingly, which is critical in the ethnically diverse population of the United States.

Keeping a procedure log during fellowship can seem daunting and cumbersome, but it is important. Dr. Houman Rezaizadeh (University of Connecticut) shares his program’s experience with the AGA Procedure Log, a convenient online tracking tool, which can provide accurate and secure documentation of endoscopic procedures performed throughout fellowship.

Dr. Nazia Hasan (North Bay Health Care) and Dr. Allison Schulman (University of Michigan) broach an incredibly important topic: the paucity of women in interventional endoscopy. Dr. Hasan and Dr. Shulman candidly discuss the barriers women face in pursuing this subspecialty and offer practical solutions on how to approach these challenges – a piece that will surely resonate with many young gastroenterologists.

We wrap up our first year of TNG’s ethics series with two cases discussing the utilization of cannabis therapy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Dr. Jami Kinnucan (University of Michigan) and Dr. Arun Swaminath (Lenox Hill Hospital) systematically review existing data on the efficacy of cannabis use in IBD, the risks associated with therapy, and legal implications for both physicians and patients.

Also in this issue is a high-yield clinical review on the endoscopic drainage of pancreatic fluid collections by Dr. Robert Moran and Dr. Joseph Elmunzer (Medical University of South Carolina). Dr. Manol Jovani (Johns Hopkins) teaches us about confounding – a critical concept to keep in mind when evaluating any manuscript. Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. Mehul Lalani (US Digestive), reviews how quality measures and initiatives are tracked and implemented in private practice.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Dear colleagues,

I’m excited to introduce the November issue of The New Gastroenterologist – the last edition of 2020 features a fantastic line-up of articles! As the year comes to a close, we reflect on what has certainly been an interesting year, defined by a set of unique challenges we have faced as a nation and as a specialty.

The fellowship recruitment season is one that has looked starkly different as interviews have converted to a virtual format. Dr. Wissam Khan, Dr. Nada Al Masalmeh, Dr. Stephanie Judd, and Dr. Diane Levine (Wayne State University) compile a helpful list of tips and tricks on proper interview etiquette in the new era of web-based interviews.

Financial planning in the face of a pandemic is a formidable task – Jonathan Tudor (Fidelity Investments) offers valuable advice for gastroenterologists on how to remain secure in your finances even in uncertain circumstances.

This quarter’s “In Focus” feature, written by Dr. Yutaka Tomizawa (University of Washington), is a comprehensive piece elucidating the role of gastroenterologists in the management of gastric cancer. The article reviews the individual risk factors that exist for gastric cancer and provides guidance on how to stratify patients accordingly, which is critical in the ethnically diverse population of the United States.

Keeping a procedure log during fellowship can seem daunting and cumbersome, but it is important. Dr. Houman Rezaizadeh (University of Connecticut) shares his program’s experience with the AGA Procedure Log, a convenient online tracking tool, which can provide accurate and secure documentation of endoscopic procedures performed throughout fellowship.

Dr. Nazia Hasan (North Bay Health Care) and Dr. Allison Schulman (University of Michigan) broach an incredibly important topic: the paucity of women in interventional endoscopy. Dr. Hasan and Dr. Shulman candidly discuss the barriers women face in pursuing this subspecialty and offer practical solutions on how to approach these challenges – a piece that will surely resonate with many young gastroenterologists.

We wrap up our first year of TNG’s ethics series with two cases discussing the utilization of cannabis therapy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Dr. Jami Kinnucan (University of Michigan) and Dr. Arun Swaminath (Lenox Hill Hospital) systematically review existing data on the efficacy of cannabis use in IBD, the risks associated with therapy, and legal implications for both physicians and patients.

Also in this issue is a high-yield clinical review on the endoscopic drainage of pancreatic fluid collections by Dr. Robert Moran and Dr. Joseph Elmunzer (Medical University of South Carolina). Dr. Manol Jovani (Johns Hopkins) teaches us about confounding – a critical concept to keep in mind when evaluating any manuscript. Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. Mehul Lalani (US Digestive), reviews how quality measures and initiatives are tracked and implemented in private practice.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Role of gastroenterologists in the U.S. in the management of gastric cancer

Introduction

Although gastric cancer is one of the most common causes of cancer death in the world, the burden of gastric cancer in the United States tends to be underestimated relative to that of other cancers of the digestive system. In fact, the 5-year survival rate from gastric cancer remains poor (~32%)1 in the United States, and this is largely because gastric cancers are not diagnosed at an early stage when curative therapeutic options are available. Cumulative epidemiologic data consistently demonstrate that the incidence of gastric cancer in the United States varies according to ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin. It is important for practicing gastroenterologists in the United States to recognize individual risk profiles and identify people at higher risk for gastric cancer. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer is an inherited form of diffuse-type gastric cancer and has pathogenic variants in the E-cadherin gene that are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. The lifetime risk of gastric cancer in individuals with HDGC is very high, and prophylactic total gastrectomy is usually advised. This article focuses on intestinal type cancer.

Epidemiology

Gastric cancer (proximal and distal gastric cancer combined) is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the third most common cause of cancer death worldwide, with 1,033,701 new cases and 782,685 deaths in 2018.2 Gastric cancer is subcategorized based on location (proximal [i.e., esophagogastric junctional, gastric cardia] and distal) and histology (intestinal and diffuse type), and each subtype is considered to have a distinct pathogenesis. Distal intestinal type gastric cancer is most commonly encountered in clinical practice. In this article, gastric cancer will signify distal intestinal type gastric cancer unless it is otherwise noted. In general, incidence rates are about twofold higher in men than in women. There is marked geographic variation in incidence rates, and the age-standardized incidence rates in eastern Asia (32.1 and 13.2, per 100,000) are approximately six times higher than those in northern America (5.6 and 2.8, per 100,000) in both men and women, respectively.2 Recent studies evaluating global trends in the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer have demonstrated decreases worldwide.3-5 However, the degree of decrease in the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer varies substantially across geographic regions, reflecting the heterogeneous distribution of risk profiles. A comprehensive analysis of a U.S. population registry demonstrated a linear decrease in the incidence of gastric cancer in the United States (0.94% decrease per year between 2001 and 2015),6 though the annual percent change in the gastric cancer mortality in the United States was lower (around 2% decrease per year between 1980 and 2011) than in other countries.3Several population-based studies conducted in the United States have demonstrated that the incidence of gastric cancer varied by ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin, and the highest incidence was observed among Asian immigrants.7,8 A comprehensive meta-analysis examining the risk of gastric cancer in immigrants from high-incidence regions to low-incidence regions found a persistently higher risk of gastric cancer and related mortality among immigrants.9 These results indicate that there are important risk factors such as environmental and dietary factors in addition to the traditionally considered risk factors including male gender, age, family history, and tobacco use. A survey conducted in an ethnically and culturally diverse U.S. city showed that gastroenterology providers demonstrated knowledge deficiencies in identifying and managing patients with increased risk of gastric cancer.10 Recognizing individualized risk profiles in higher-risk groups (e.g., immigrants from higher-incidence/prevalence regions) is important for optimizing management of gastric cancer in the United States.

Assessment and management of modifiable risk factors

Helicobacter pylori, a group 1 carcinogen, is the most well-recognized risk factor for gastric cancer, particularly noncardia gastric cancer.11 Since a landmark longitudinal follow-up study in Japan demonstrated that people with H. pylori infection are more likely to develop gastric cancer than those without H. pylori infection,12 accumulating evidence largely from Asian countries has shown that eradication of H. pylori is associated with a reduced incidence of gastric cancer regardless of baseline risk.13 There are also data on the protective effect for gastric cancer of H. pylori eradication in asymptomatic individuals. Another meta-analysis of six international randomized control trials demonstrated a 34% relative risk reduction of gastric cancer occurrence in asymptomatic people (relative risk of developing gastric cancer was 0.66 in those who received eradication therapy compared with those with placebo or no treatment, 95% CI, 0.46-0.95).14 A U.S. practice guideline published after these meta-analyses recommends that all patients with a positive test indicating active infection with H. pylori should be offered treatment and testing to prove eradication,15 though the recommendation was not purely intended to reduce the gastric cancer risk in U.S. population. Subsequently, a Department of Veterans Affairs cohort study added valuable insights from a U.S. experience to the body of evidence from other countries with higher prevalence. In this study of more than 370,000 patients with a history of H. pylori infection, the detection and successful eradication of H. pylori was associated with a 76% lower incidence of gastric cancer compared with people without H. pylori treatment.16 This study also provided insight into H. pylori treatment practice patterns. Of patients with a positive H. pylori test result (stool antigen, urea breath test, or pathology), approximately 75% were prescribed an eradication regimen and only 21% of those underwent eradication tests. A low rate (24%) of eradication testing was subsequently reported by the same group among U.S. patients regardless of gastric cancer risk profiles.17 The lesson from the aforementioned study is that treatment and eradication of H. pylori even among asymptomatic U.S. patients reduces the risk of subsequent gastric cancer. However, it may be difficult to generalize the results of this study given the nature of the Veterans Affairs cohort, and more data are required to justify the implementation of nationwide preventive H. pylori screening in the general U.S. population.

Smoking has been recognized as the other important risk factor. A study from the European prospective multicenter cohort demonstrated a significant association of cigarette smoking and gastric cancer risk (HR for ever-smokers 1.45 [95% CI, 1.08-1.94], current-smokers in males 1.73 [95% CI, 1.06-2.83], and current smokers in females 1.87 [95% CI, 1.12-3.12], respectively) after adjustment for educational level, dietary consumption profiles, alcohol intake, and body mass index (BMI).18 A subsequent meta-analysis provided solid evidence of smoking as the important behavioral risk factor for gastric cancer.19 Smoking also predisposed to the development of proximal gastric cancer.20 Along with other cancers in the digestive system such as in the esophagus, colon and rectum, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas, a significant association of BMI and the risk of proximal gastric cancer (RR of the highest BMI category compared with normal BMI, 1.8 [95% CI, 1.3-2.5]) was reported, with positive dose-response relationships; however, the association was not sufficient for distal gastric cancer.21 There is also evidence to show a trend of greater alcohol consumption (>45 grams per day [about 3 drinks a day]) associated with the increased risk of gastric cancer.21 It has been thought that salt and salt-preserved food increase the risk of gastric cancer. It should be noted that the observational studies showing the associations were published from Asian countries where such foods were a substantial part of traditional diets (e.g., salted vegetables in Japan) and the incidence of gastric cancer is high. There is also a speculation that preserved foods may have been eaten in more underserved, low socioeconomic regions where refrigeration was not available and prevalence of H. pylori infection was higher. Except for documented inherited form of gastric cancer (e.g., HDGC or hereditary cancer syndromes), most gastric cancers are considered sporadic. A recent randomized study published from South Korea investigated a cohort of higher-risk asymptomatic patients with family history significant for gastric cancer. This study of 1,676 subjects with a median follow-up of 9.2 years showed that successful eradication of H. pylori in the first-degree relatives of those with gastric cancer significantly reduced the risk (HR 0.45 [95% CI, 0.21-0.94]) of developing gastric cancer.22 As previously discussed, in the United States where the prevalence of H. pylori and the incidence of gastric cancer are both lower than in some Asian countries, routine screening of asymptomatic individuals for H. pylori is not justified yet. There may be a role for screening individuals who are first-generation immigrants from areas of high gastric cancer incidence and also have a first-degree relative with gastric cancer.

Who should we consider high risk and offer screening EGD?

With available evidence to date, screening for gastric cancer in a general U.S. population is not recommended. However, it is important to acknowledge the aforementioned varying incidence of gastric cancer in the United States among ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin. Immigrants from high-incidence regions maintain a higher risk of gastric cancer and related mortality even after migration to lower-incidence regions. The latter comprehensive study estimated that as many as 12.7 million people (29.4% of total U.S. immigrant population) have emigrated from higher-incidence regions including East Asian and some Central American countries.9 Indeed, an opportunistic nationwide gastric cancer screening program has been implemented in South Korea (beginning at age 40, biannually)23 and Japan (beginning at age 50, biannually).24 Two decision-analytic simulation studies have provided insight into the uncertainty about the cost effectiveness for potential targeted gastric cancer screening in higher-risk populations in the United States. One study demonstrated that esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) screening for otherwise asymptomatic Asian American people (as well as Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks) at the time of screening colonoscopy at 50 years of age with continued endoscopic surveillance every 3 years was cost effective, only if gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM) or more advanced lesions were diagnosed at the index screening EGD.25 Previous studies analyzing the cost effectiveness for gastric cancer screening in the United States had the limitation of not stratifying according to race or ethnicity, or accounting for patients diagnosed with GIM. Subsequently, the same research group extended this model analysis and has published additional findings that this strategy is cost effective for each of the most prevalent Asian American ethnicities (Chinese, Filipino, Southeast Asian, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese Americans) in the United States irrespective of sex.26 Although the authors raised a limitation that additional risk factors such as family history, tobacco use, or persistent H. pylori infection were not considered in the model because data regarding differentiated noncardia gastric cancer risk among Asian American ethnicities based on these risk factors are not available.

These two model analytic studies added valuable insights to the body of evidence that subsequent EGDs after the one-time bundled EGD is cost effective for higher-risk asymptomatic people in the United States, if the index screening EGD with gastric mucosal biopsies demonstrates at least GIM. Further population-based research to elucidate risk stratification among higher-risk people will provide a schema that could standardize management and resource allocation as well as increase the cost effectiveness of a gastric cancer screening program in the United States. The degree of risk of developing gastric cancer in autoimmune gastritis varies among the reported studies.27-29 Although the benefit of endoscopic screening in patients with autoimmune gastritis has not been established, a single endoscopic evaluation should be recommended soon after the diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis in order to identify prevalent neoplastic lesions.30

Practical consideration when we perform EGD for early gastric cancer screening

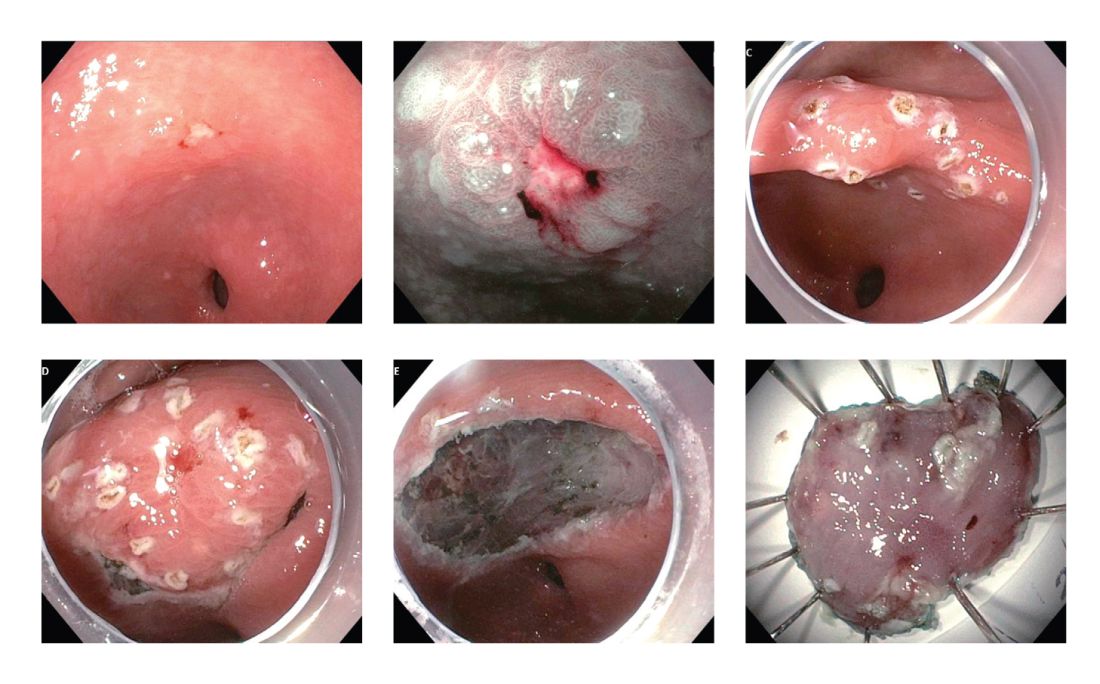

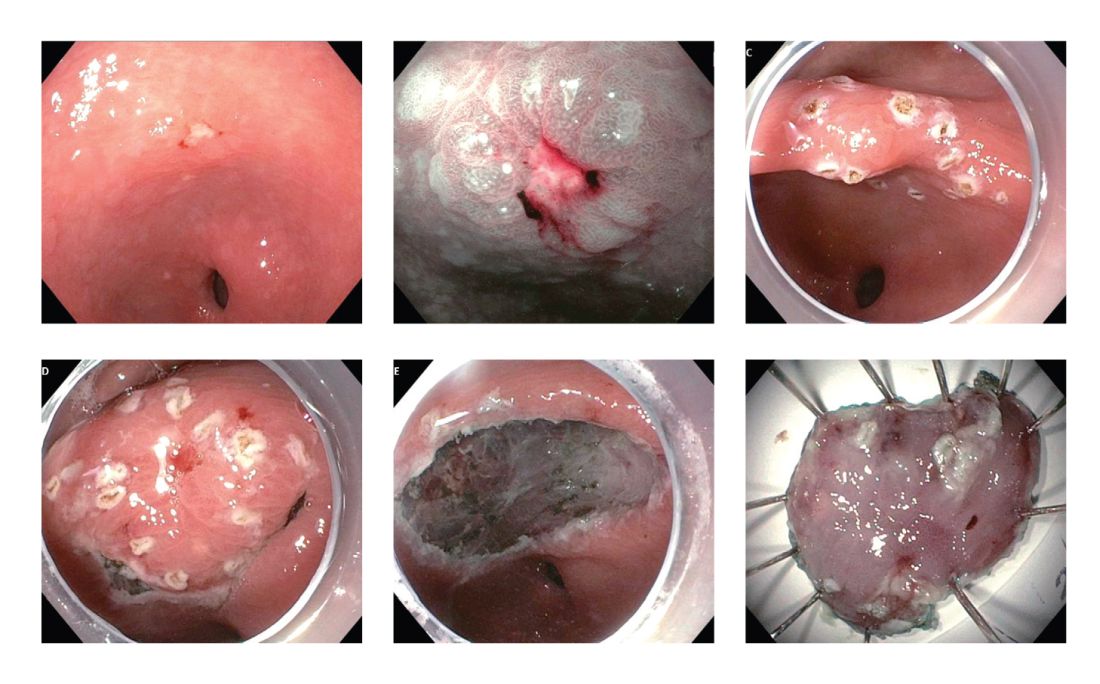

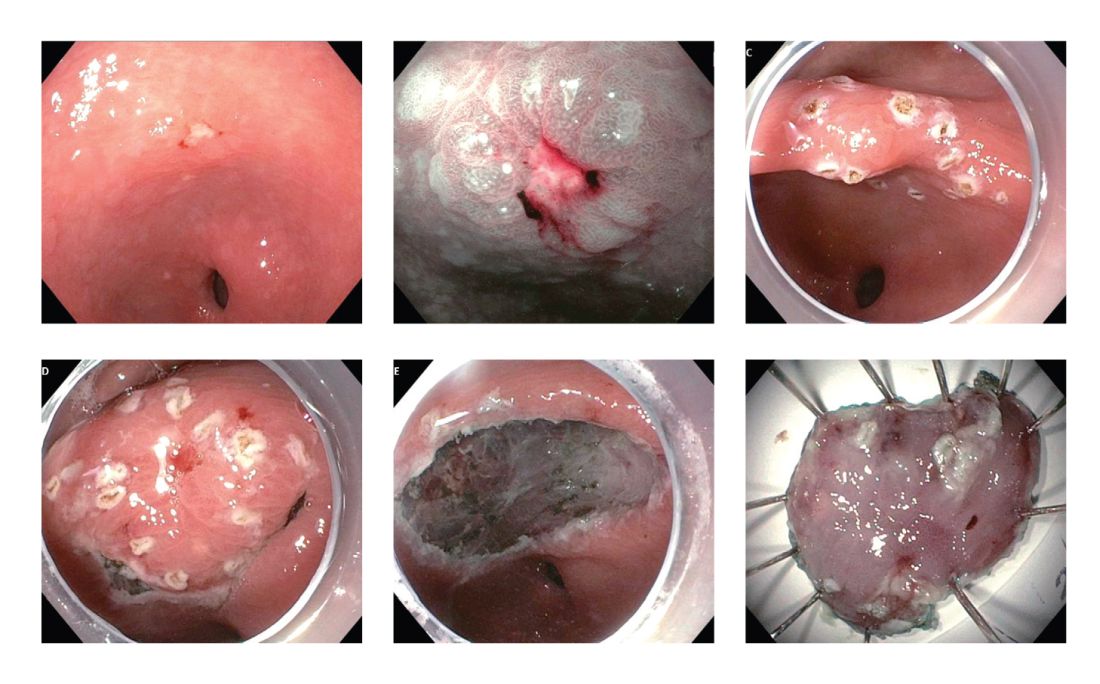

Identification of higher-risk patients should alert an endoscopist to observe mucosa with greater care with a lower threshold to biopsy any suspicious lesions. Preprocedural risk stratification for each individual before performing diagnostic EGD will improve early gastric cancer detection. While we perform EGD, detecting precursor lesions (atrophic gastritis and GIM) is as important as diagnosing an early gastric cancer. Screening and management of patients with precursor lesions (i.e., atrophic gastritis and GIM) is beyond the scope of this article, and this was published in a previous issue of the New Gastroenterologist. It is important to first grossly survey the entire gastric mucosa using high-definition while light (HDWL) endoscopy and screen for any focal irregular (raised or depressed) mucosal lesions. These lesions are often erythematous and should be examined carefully. Use of mucolytic and/or deforming agents (e.g., N-acetylcysteine or simethicone) is recommended for the improvement of visual clarity of gastric mucosa.31 Simethicone is widely used in the United States for colonoscopy and should also be available at the time of EGD for better gastric mucosal visibility. If irregular mucosal lesions are noted, this area should also be examined under narrowband imaging (NBI) in addition to HDWL. According to a simplified classification consisting of mucosal and vascular irregularity, NBI provides better mucosal surface morphology for diagnosis of early gastric cancer compared with HDWL, and a thorough examination of the surface characteristics is a prerequisite.32 This classification was further validated in a randomized control trial, and NBI increased sensitivity for the diagnosis of neoplasia compared with HDWL (92 % vs. 74 %).33 The majority of institutions in the United States have a newer-generation NBI (Olympus America, EVIS EXERA III video system, GIF-HQ190), which provides brighter endoscopic images to better characterize gastric neoplastic lesions. Once we recognize an area suspicious for neoplasia, we should describe the macroscopic features according to a classification system.

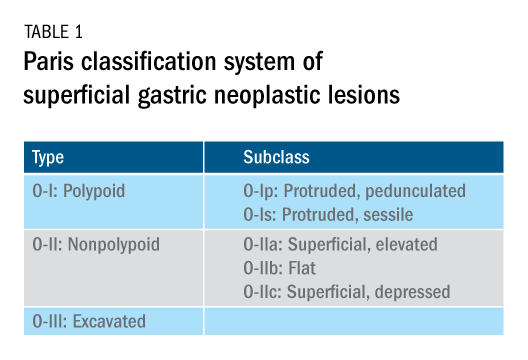

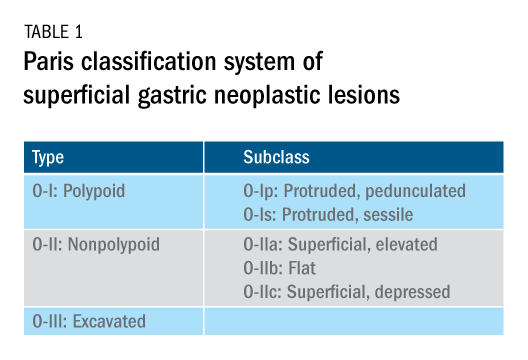

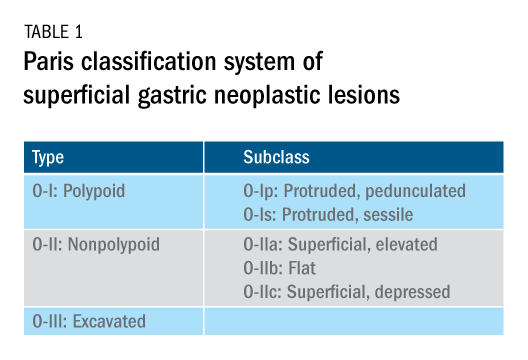

The Paris classification, one of the most widely recognized classification systems among U.S. gastroenterologists, is recommended for gastric neoplastic lesions.34Gastric neoplastic lesions with a “superficial” endoscopic appearance are classified as subtypes of “type 0.” The term “type 0” was chosen to distinguish the classification of “superficial” lesions from the Borrmann classification for “advanced” gastric tumors, which includes types 1 to 4. In the classification, a neoplastic lesion is called “superficial” when its endoscopic appearance suggests that the depth of penetration in the digestive wall is not more than into the submucosa (i.e., there is no infiltration of the muscularis propria). The distinctive characters of polypoid and nonpolypoid lesions are summarized in Table 1. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has steadily gained acceptance for the treatment of early gastric cancer in the United States. The American Gastroenterological Association recommended in the 2019 institutional updated clinical practice guideline that ESD should be considered the first-line therapy for visible, endoscopically resectable, superficial gastric neoplasia.35 This recommendation is further supported by the published data on efficacy and safety of ESD for early gastric neoplasia in a large multicenter cohort in the United States.36 For all suspicious lesions, irrespective of pathological neoplastic confirmation, referral to an experienced center for further evaluation and endoscopic management should be considered. Lastly, all patients with early gastric cancer should be evaluated for H. pylori infection and treated if the test is positive. Eradication of H. pylori is associated with a lower rate of metachronous gastric cancer,37 and treatment of H. pylori as secondary prevention is also recommended.

Conclusion

As summarized above, cumulative epidemiologic data consistently demonstrate that the incidence of gastric cancer in the U.S. varies according to ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin. New gastroenterologists will need to recognize individual risk profiles and identify people at higher risk for gastric cancer. Risk stratification before performing endoscopic evaluation will improve early gastric cancer detection and make noninvasive, effective therapies an option.

References

1. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program cancer statistics. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/stomach.html.

2. Bray F et al. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424.

3. Ferro A et al. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1330-44.

4. Luo G et al. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:1333-44.

5. Arnold M et al. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1164-87.

6. Thrift AP, El-Serag HB. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:534-42.

7. Kim Y et al. Epidemiol Health. 2015;37:e2015066.

8. Kamineni A et al. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:77-83.

9. Pabla BS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:347-59.

10. Shah SC et al. Knowledge Gaps among Physicians Caring for Multiethnic Populations at Increased Gastric Cancer Risk. Gut Liver. 2018 Jan 15;12(1):38-45.

11. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. IARC. July 7, 2019. 12. Uemura N et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-9.

13. Lee YC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1113-24.

14. Ford AC et al. BMJ. 2014;348:g3174.

15. Chey W et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212-39.

16. Kumar S et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:527-36.

17. Kumar S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr 6;S1542-3565(20)30436-5.

18. González CA et al. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:629-34.

19. Ladeiras-Lopes R et al. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:689-701.

20. Cavaleiro-Pinto M et al. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:375-87.

21. Lauby-Secretan B et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:794-8.

22. Choi IJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:427-36.

23. Kim BJ et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:736-41.

24. Hamashima C. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48:278–86.

25. Saumoy M et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:648-60.

26. Shah SC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jul 21:S1542-3565(20)30993-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.031.

27. Brinton LA et al. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:810-3.

28. Hsing AW et al. Cancer. 1993;71:745-50.

29. Schafer LW et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60:444-8.

30. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Standards of Practice Committee. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1-8.

31. Chiu PWY et al. Gut. 2019;68:186-97.

32. Pimentel-Nunes P et al. Endoscopy. 2012;44:236-46.

33. Pimentel-Nunes P et al. Endoscopy. 2016;48:723-30.

34. Participants in the Paris Workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43.

35. Draganov PV et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:16-25.

36. Ngamruengphong S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun 18;S1542-3565(20)30834-X. Online ahead of print.

37. Choi IJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1085-95.

Dr. Tomizawa is a clinical assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, University of Washington, Seattle.

Introduction

Although gastric cancer is one of the most common causes of cancer death in the world, the burden of gastric cancer in the United States tends to be underestimated relative to that of other cancers of the digestive system. In fact, the 5-year survival rate from gastric cancer remains poor (~32%)1 in the United States, and this is largely because gastric cancers are not diagnosed at an early stage when curative therapeutic options are available. Cumulative epidemiologic data consistently demonstrate that the incidence of gastric cancer in the United States varies according to ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin. It is important for practicing gastroenterologists in the United States to recognize individual risk profiles and identify people at higher risk for gastric cancer. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer is an inherited form of diffuse-type gastric cancer and has pathogenic variants in the E-cadherin gene that are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. The lifetime risk of gastric cancer in individuals with HDGC is very high, and prophylactic total gastrectomy is usually advised. This article focuses on intestinal type cancer.

Epidemiology

Gastric cancer (proximal and distal gastric cancer combined) is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the third most common cause of cancer death worldwide, with 1,033,701 new cases and 782,685 deaths in 2018.2 Gastric cancer is subcategorized based on location (proximal [i.e., esophagogastric junctional, gastric cardia] and distal) and histology (intestinal and diffuse type), and each subtype is considered to have a distinct pathogenesis. Distal intestinal type gastric cancer is most commonly encountered in clinical practice. In this article, gastric cancer will signify distal intestinal type gastric cancer unless it is otherwise noted. In general, incidence rates are about twofold higher in men than in women. There is marked geographic variation in incidence rates, and the age-standardized incidence rates in eastern Asia (32.1 and 13.2, per 100,000) are approximately six times higher than those in northern America (5.6 and 2.8, per 100,000) in both men and women, respectively.2 Recent studies evaluating global trends in the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer have demonstrated decreases worldwide.3-5 However, the degree of decrease in the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer varies substantially across geographic regions, reflecting the heterogeneous distribution of risk profiles. A comprehensive analysis of a U.S. population registry demonstrated a linear decrease in the incidence of gastric cancer in the United States (0.94% decrease per year between 2001 and 2015),6 though the annual percent change in the gastric cancer mortality in the United States was lower (around 2% decrease per year between 1980 and 2011) than in other countries.3Several population-based studies conducted in the United States have demonstrated that the incidence of gastric cancer varied by ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin, and the highest incidence was observed among Asian immigrants.7,8 A comprehensive meta-analysis examining the risk of gastric cancer in immigrants from high-incidence regions to low-incidence regions found a persistently higher risk of gastric cancer and related mortality among immigrants.9 These results indicate that there are important risk factors such as environmental and dietary factors in addition to the traditionally considered risk factors including male gender, age, family history, and tobacco use. A survey conducted in an ethnically and culturally diverse U.S. city showed that gastroenterology providers demonstrated knowledge deficiencies in identifying and managing patients with increased risk of gastric cancer.10 Recognizing individualized risk profiles in higher-risk groups (e.g., immigrants from higher-incidence/prevalence regions) is important for optimizing management of gastric cancer in the United States.

Assessment and management of modifiable risk factors

Helicobacter pylori, a group 1 carcinogen, is the most well-recognized risk factor for gastric cancer, particularly noncardia gastric cancer.11 Since a landmark longitudinal follow-up study in Japan demonstrated that people with H. pylori infection are more likely to develop gastric cancer than those without H. pylori infection,12 accumulating evidence largely from Asian countries has shown that eradication of H. pylori is associated with a reduced incidence of gastric cancer regardless of baseline risk.13 There are also data on the protective effect for gastric cancer of H. pylori eradication in asymptomatic individuals. Another meta-analysis of six international randomized control trials demonstrated a 34% relative risk reduction of gastric cancer occurrence in asymptomatic people (relative risk of developing gastric cancer was 0.66 in those who received eradication therapy compared with those with placebo or no treatment, 95% CI, 0.46-0.95).14 A U.S. practice guideline published after these meta-analyses recommends that all patients with a positive test indicating active infection with H. pylori should be offered treatment and testing to prove eradication,15 though the recommendation was not purely intended to reduce the gastric cancer risk in U.S. population. Subsequently, a Department of Veterans Affairs cohort study added valuable insights from a U.S. experience to the body of evidence from other countries with higher prevalence. In this study of more than 370,000 patients with a history of H. pylori infection, the detection and successful eradication of H. pylori was associated with a 76% lower incidence of gastric cancer compared with people without H. pylori treatment.16 This study also provided insight into H. pylori treatment practice patterns. Of patients with a positive H. pylori test result (stool antigen, urea breath test, or pathology), approximately 75% were prescribed an eradication regimen and only 21% of those underwent eradication tests. A low rate (24%) of eradication testing was subsequently reported by the same group among U.S. patients regardless of gastric cancer risk profiles.17 The lesson from the aforementioned study is that treatment and eradication of H. pylori even among asymptomatic U.S. patients reduces the risk of subsequent gastric cancer. However, it may be difficult to generalize the results of this study given the nature of the Veterans Affairs cohort, and more data are required to justify the implementation of nationwide preventive H. pylori screening in the general U.S. population.