User login

Acute pancreatitis, dealing with difficult people, and more

I’m very excited about the first issue of The New Gastroenterologist in 2019, which has some fantastic articles that I hope you will find interesting and useful. The In Focus feature this month covers acute pancreatitis, which is an incredibly important topic for all in our field. Amar Mandalia and Matthew DiMagno (University of Michigan) provide a comprehensive overview of the management of acute pancreatitis, including a review of the recent AGA guideline on this topic. This article can be found online, as well as in print in the February issue of GI & Hepatology News.

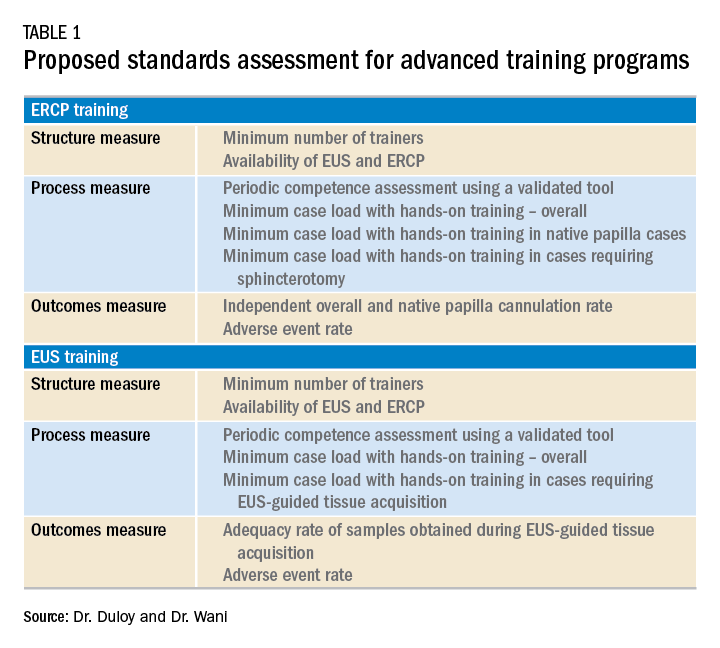

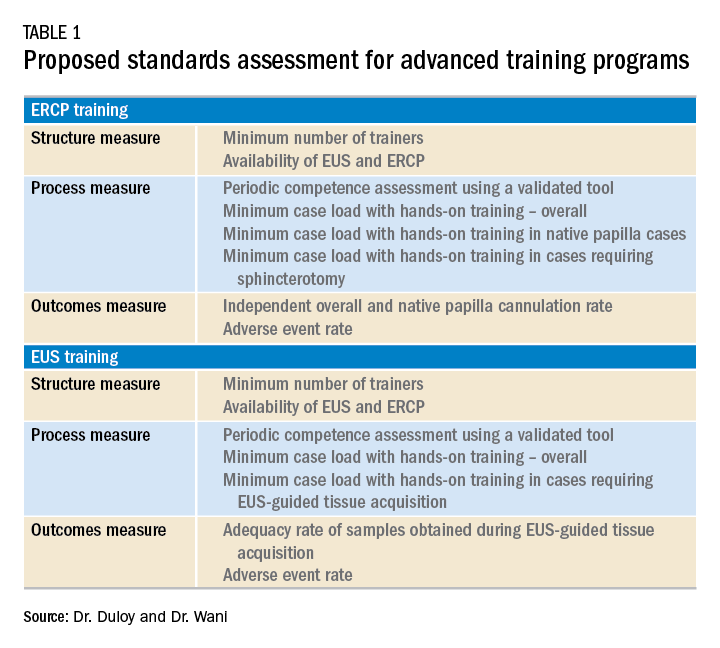

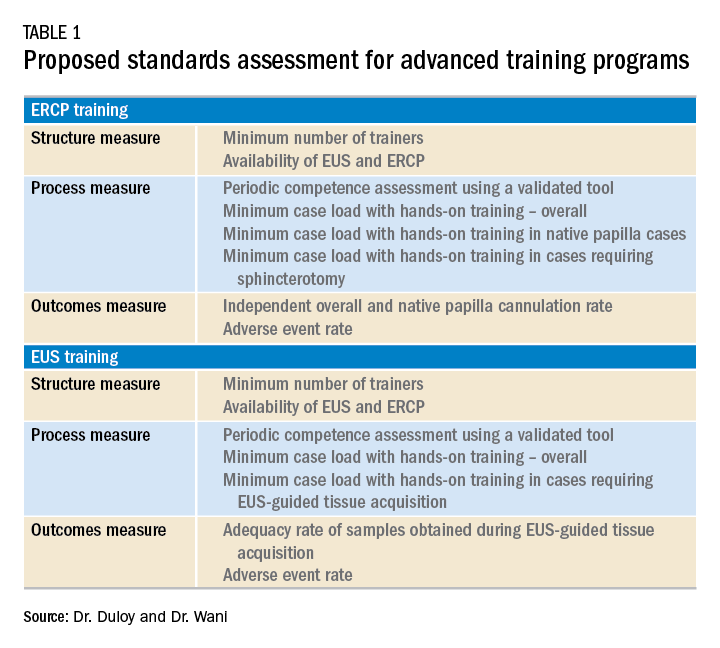

Rhonda Cole (Michael E. DeBakey VAMC/Baylor) addresses the important topic of how to deal with difficult people, and she provides some useful tips for situations that many of us struggle with. Also in this issue, Rishi Naik (Vanderbilt) and current Associate Editor of Gastroenterology John Inadomi (University of Washington) provide some tips on how to write an effective cover letter for a journal submission. Anna Duloy and Sachin Wani (University of Colorado) provide an overview of the current state of training in advanced endoscopy, which will be very helpful for all those considering a fellowship or incorporation of these procedures into their practices.

For those looking to pick the right private practice position, David Ramsay (Digestive Health Specialists, Winston-Salem, N.C.) provides some useful tips to help you find the job that will be the best fit. In prior issues of The New Gastroenterologist, there have been several articles discussing saving for retirement, but how about how to effectively save for your children’s education? To address that topic, Michael Clancy (Drexel) provides an informative overview of 529 college savings accounts.

Finally, Gyanprakash Ketwaroo (Baylor), Peter Liang (NYU Langone), Carol Brown, and Celena NuQuay (AGA) provide an overview of one of the most important and impactful initiatives from the AGA for the early career community – the AGA Regional Practice Skills Workshops. These workshops are a tremendous resource for early career GIs, and I would recommend that you check one out if you have not already had the opportunity.

If you’re interested in browsing older articles from The New Gastroenterologist, articles from previous issues can be found on our webpage. Also, we are always looking for new ideas and new contributors. If you have suggestions or are interested, please contact me at [email protected] or the managing editor, Ryan Farrell, at [email protected]

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Dr. Katona is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

I’m very excited about the first issue of The New Gastroenterologist in 2019, which has some fantastic articles that I hope you will find interesting and useful. The In Focus feature this month covers acute pancreatitis, which is an incredibly important topic for all in our field. Amar Mandalia and Matthew DiMagno (University of Michigan) provide a comprehensive overview of the management of acute pancreatitis, including a review of the recent AGA guideline on this topic. This article can be found online, as well as in print in the February issue of GI & Hepatology News.

Rhonda Cole (Michael E. DeBakey VAMC/Baylor) addresses the important topic of how to deal with difficult people, and she provides some useful tips for situations that many of us struggle with. Also in this issue, Rishi Naik (Vanderbilt) and current Associate Editor of Gastroenterology John Inadomi (University of Washington) provide some tips on how to write an effective cover letter for a journal submission. Anna Duloy and Sachin Wani (University of Colorado) provide an overview of the current state of training in advanced endoscopy, which will be very helpful for all those considering a fellowship or incorporation of these procedures into their practices.

For those looking to pick the right private practice position, David Ramsay (Digestive Health Specialists, Winston-Salem, N.C.) provides some useful tips to help you find the job that will be the best fit. In prior issues of The New Gastroenterologist, there have been several articles discussing saving for retirement, but how about how to effectively save for your children’s education? To address that topic, Michael Clancy (Drexel) provides an informative overview of 529 college savings accounts.

Finally, Gyanprakash Ketwaroo (Baylor), Peter Liang (NYU Langone), Carol Brown, and Celena NuQuay (AGA) provide an overview of one of the most important and impactful initiatives from the AGA for the early career community – the AGA Regional Practice Skills Workshops. These workshops are a tremendous resource for early career GIs, and I would recommend that you check one out if you have not already had the opportunity.

If you’re interested in browsing older articles from The New Gastroenterologist, articles from previous issues can be found on our webpage. Also, we are always looking for new ideas and new contributors. If you have suggestions or are interested, please contact me at [email protected] or the managing editor, Ryan Farrell, at [email protected]

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Dr. Katona is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

I’m very excited about the first issue of The New Gastroenterologist in 2019, which has some fantastic articles that I hope you will find interesting and useful. The In Focus feature this month covers acute pancreatitis, which is an incredibly important topic for all in our field. Amar Mandalia and Matthew DiMagno (University of Michigan) provide a comprehensive overview of the management of acute pancreatitis, including a review of the recent AGA guideline on this topic. This article can be found online, as well as in print in the February issue of GI & Hepatology News.

Rhonda Cole (Michael E. DeBakey VAMC/Baylor) addresses the important topic of how to deal with difficult people, and she provides some useful tips for situations that many of us struggle with. Also in this issue, Rishi Naik (Vanderbilt) and current Associate Editor of Gastroenterology John Inadomi (University of Washington) provide some tips on how to write an effective cover letter for a journal submission. Anna Duloy and Sachin Wani (University of Colorado) provide an overview of the current state of training in advanced endoscopy, which will be very helpful for all those considering a fellowship or incorporation of these procedures into their practices.

For those looking to pick the right private practice position, David Ramsay (Digestive Health Specialists, Winston-Salem, N.C.) provides some useful tips to help you find the job that will be the best fit. In prior issues of The New Gastroenterologist, there have been several articles discussing saving for retirement, but how about how to effectively save for your children’s education? To address that topic, Michael Clancy (Drexel) provides an informative overview of 529 college savings accounts.

Finally, Gyanprakash Ketwaroo (Baylor), Peter Liang (NYU Langone), Carol Brown, and Celena NuQuay (AGA) provide an overview of one of the most important and impactful initiatives from the AGA for the early career community – the AGA Regional Practice Skills Workshops. These workshops are a tremendous resource for early career GIs, and I would recommend that you check one out if you have not already had the opportunity.

If you’re interested in browsing older articles from The New Gastroenterologist, articles from previous issues can be found on our webpage. Also, we are always looking for new ideas and new contributors. If you have suggestions or are interested, please contact me at [email protected] or the managing editor, Ryan Farrell, at [email protected]

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Dr. Katona is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

New concepts in the management of acute pancreatitis

Introduction

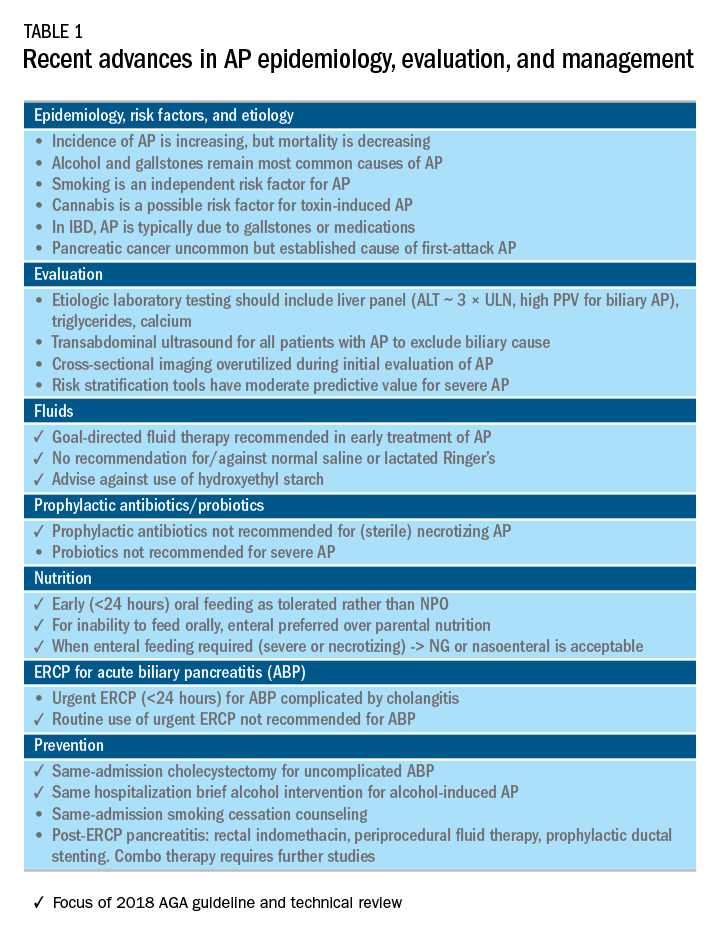

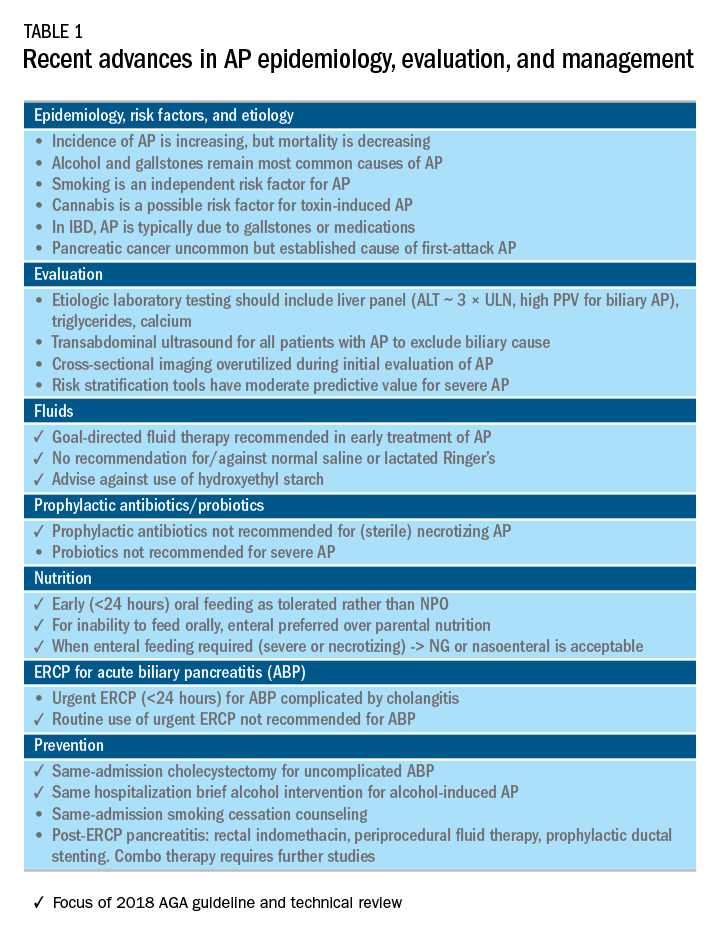

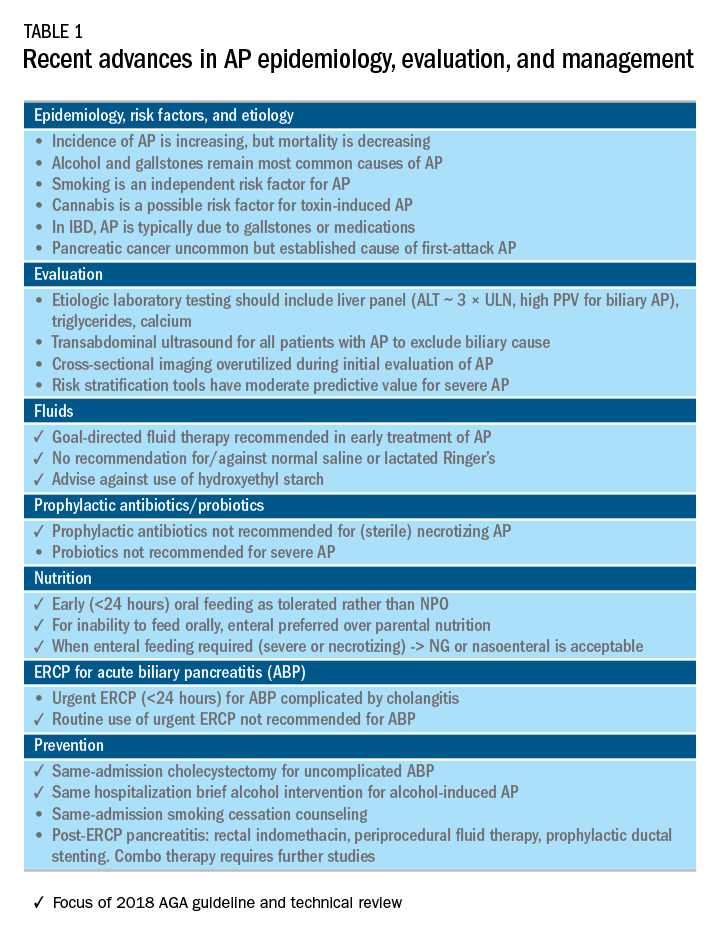

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a major clinical and financial burden in the United States. Several major clinical guidelines provide evidence-based recommendations for the clinical management decisions in AP, including those from the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG; 2013),1 and the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP; 2013).2 More recently, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) released their own set of guidelines.3,4 In this update on AP, we review these guidelines and reference recent literature focused on epidemiology, risk factors, etiology, diagnosis, risk stratification, and recent advances in the early medical management of AP. Regarding the latter, we review six treatment interventions (pain management, intravenous fluid resuscitation, feeding, prophylactic antibiotics, probiotics, and timing of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in acute biliary pancreatitis) and four preventive interventions (alcohol and smoking cessation, same-admission cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis, and chemoprevention and fluid administration for post-ERCP pancreatitis [PEP]). Updates on multidisciplinary management of (infected) pancreatic necrosis is beyond the scope of this review. Table 1 summarizes the concepts discussed in this article.

Recent advances in epidemiology and evaluation of AP

Epidemiology

AP is the third most common cause of gastrointestinal-related hospitalizations and fourth most common cause of readmission in 2014.5 Recent epidemiologic studies show conflicting trends for the incidence of AP, both increasing6 and decreasing,7 likely attributable to significant differences in study designs. Importantly, multiple studies have demonstrated that hospital length of stay, costs, and mortality have declined since 2009.6,8-10

Persistent organ failure (POF), defined as organ failure lasting more than 48 hours, is the major cause of death in AP. POF, if only a single organ during AP, is associated with 27%-36% mortality; if it is multiorgan, it is associated with 47% mortality.1,11 Other factors associated with increased hospital mortality include infected pancreatic necrosis,12-14 diabetes mellitus,15 hospital-acquired infection,16 advanced age (70 years and older),17 and obesity.18 Predictive factors of 1-year mortality include readmission within 30 days, higher Charlson Comorbidity Index, and longer hospitalization.19

Risk factors

We briefly highlight recent insights into risk factors for AP (Table 1) and refer to a recent review for further discussion.20 Current and former tobacco use are independent risk factors for AP.21 The dose-response relationship of alcohol to the risk of pancreatitis is complex,22 but five standard drinks per day for 5 years is a commonly used cut-off.1,23 New evidence suggests that the relationship between the dose of alcohol and risk of AP differs by sex, linearly in men but nonlinearly (J-shaped) in women.24 Risk of AP in women was decreased with alcohol consumption of up to 40 g/day (one standard drink contains 14 g of alcohol) and increased above this amount. Cannabis is a possible risk factor for toxin-induced AP and abstinence appears to abolish risk of recurrent attacks.25

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have a 2.9-fold higher risk for AP versus non-IBD cohorts26 with the most common etiologies are from gallstones and medications.27 In patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), the risk of AP is higher in those who receive peritoneal dialysis, compared with hemodialysis28-33 and who are women, older, or have cholelithiasis or liver disease.34As recently reviewed,35 pancreatic cancer appears to be associated with first-attack pancreatitis with few exceptions.36 In this setting, the overall incidence of pancreatic cancer is low (1.5%). The risk is greatest within the first year of the attack of AP, negligible below age 40 years but steadily rising through the fifth to eighth decades.37 Pancreatic cancer screening is a conditional recommendation of the ACG guidelines in patients with unexplained AP, particularly those aged 40 years or older.1

Etiology and diagnosis

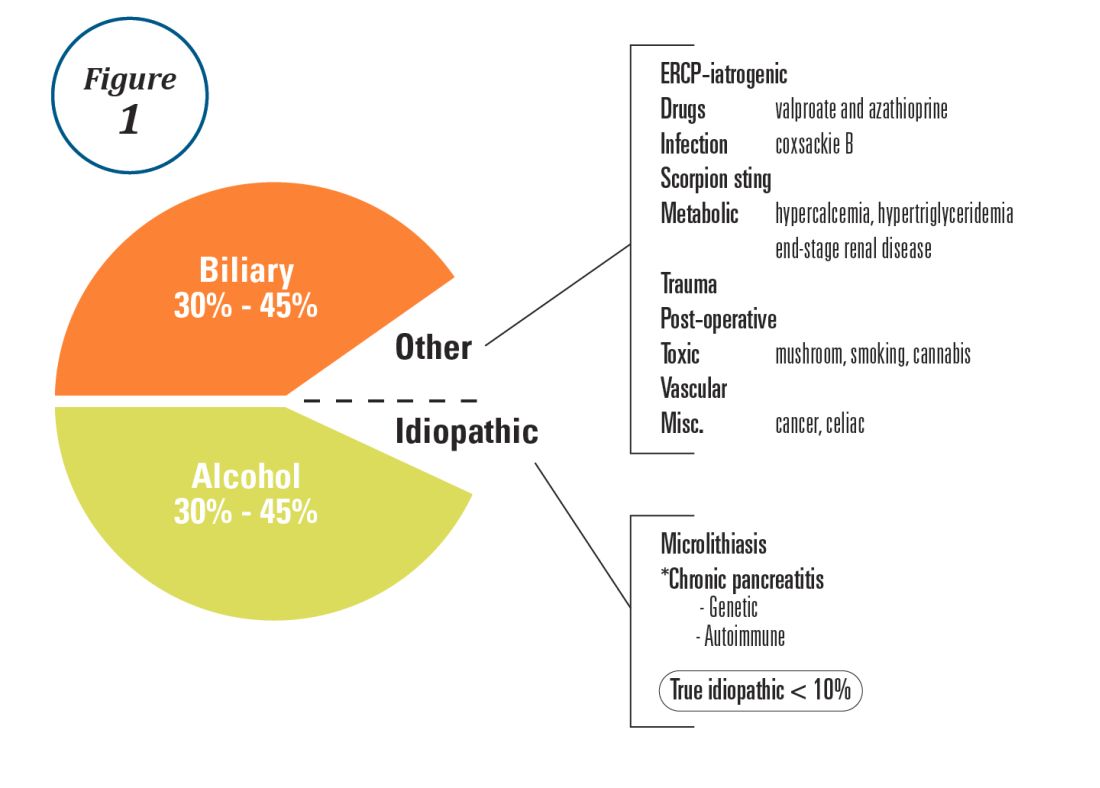

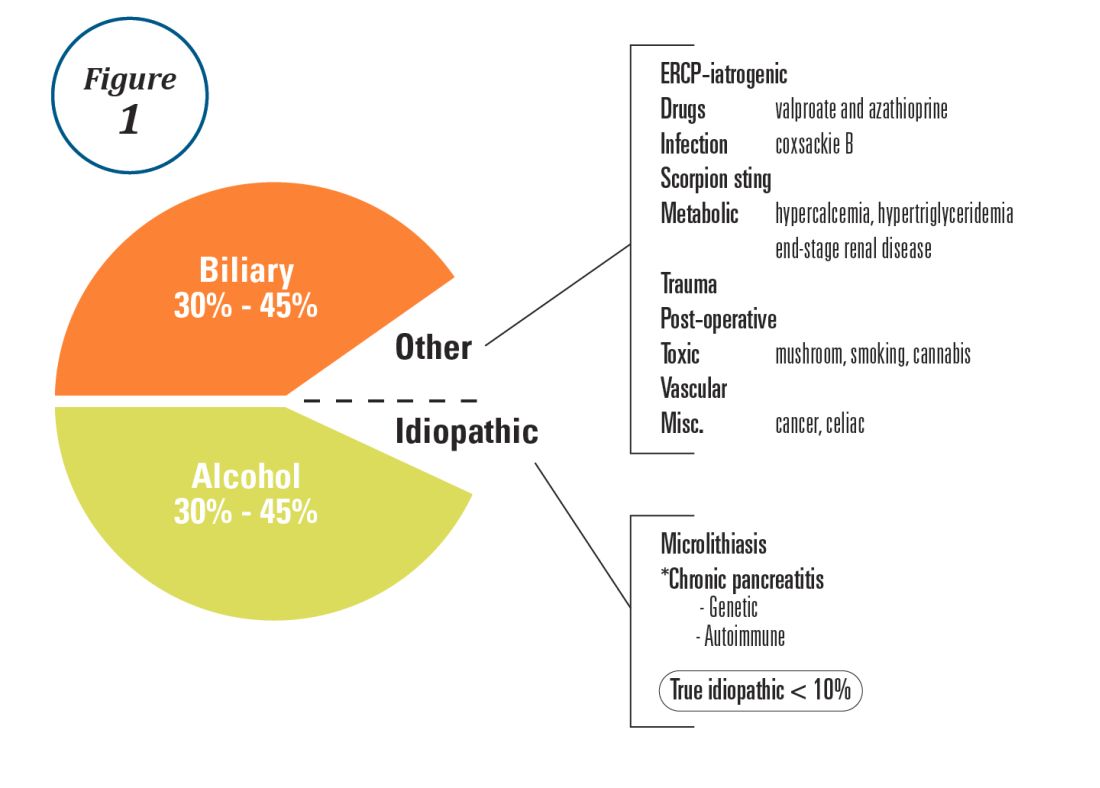

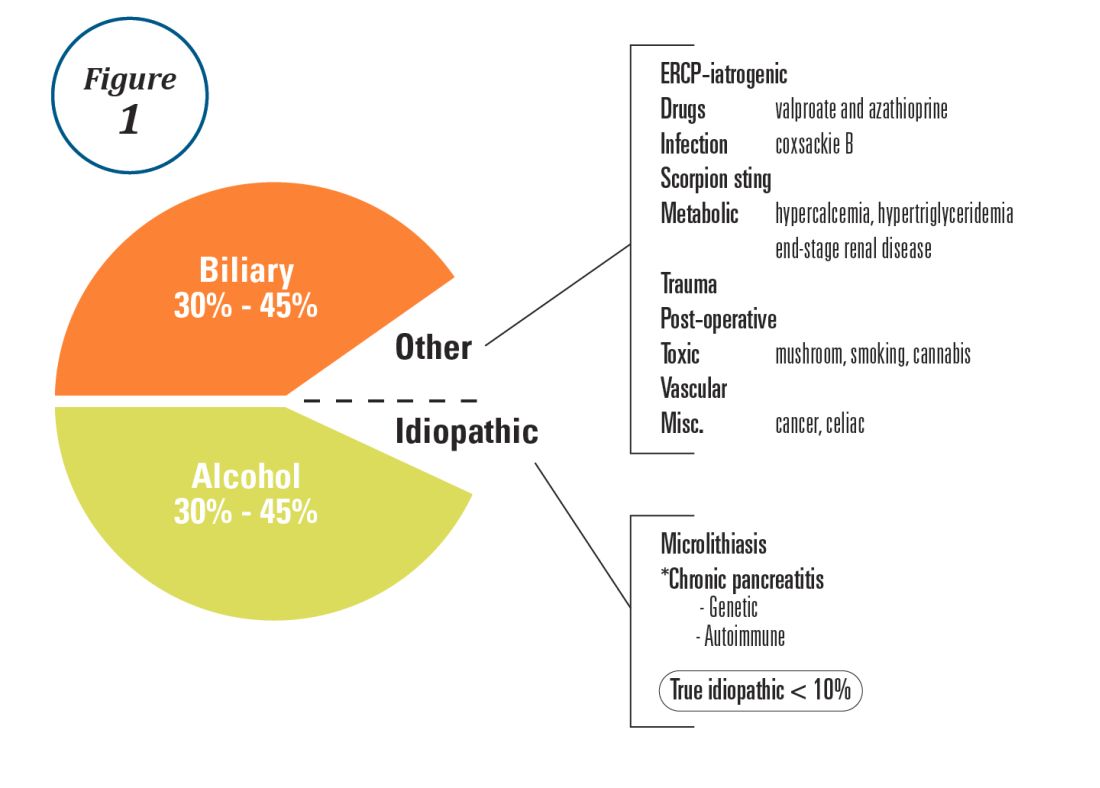

Alcohol and gallstones remain the most prevalent etiologies for AP.1 While hypertriglyceridemia accounted for 9% of AP in a systematic review of acute pancreatitis in 15 different countries,38 it is the second most common cause of acute pancreatitis in Asia (especially China).39 Figure 1 provides a breakdown of the etiologies and risk factors of pancreatitis. Importantly, it remains challenging to assign several toxic-metabolic etiologies as either a cause or risk factor for AP, particularly with regards to alcohol, smoking, and cannabis to name a few.

Guidelines and recent studies of AP raise questions about the threshold above which hypertriglyceridemia causes or poses as an important cofactor for AP. American and European societies define the threshold for triglycerides at 885-1,000 mg/dL.1,42,43 Pedersen et al. provide evidence of a graded risk of AP with hypertriglyceridemia: In multivariable analysis, adjusted hazard ratios for AP were much higher with nonfasting mild to moderately elevated plasma triglycerides (177-885 mg/dL), compared with normal values (below 89 mg/dL).44 Moreover, the risk of severe AP (developing POF) increases in proportion to triglyceride value, independent of the underlying cause of AP.45

Diagnosis of AP is derived from the revised Atlanta classification.46 The recommended timing and indications for offering cross-sectional imaging are after 48-72 hours in patients with no improvement to initial care.1 Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has better diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity, compared with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) for choledocholithiasis, and has comparable specificity.47,48 Among noninvasive imaging modalities, MRCP is more sensitive than computed tomography (CT) for diagnosing choledocholithiasis.49 Despite guideline recommendations for more selective use of pancreatic imaging in the early assessment of AP, utilization of early CT or MRCP imaging (within the first 24 hours of care) remained high during 2014-2015, compared with 2006-2007.50

ERCP is not recommended as a pure diagnostic tool, owing to the availability of other diagnostic tests and a complication rate of 5%-10% with risks involving PEP, cholangitis, perforation, and hemorrhage.51 A recent systematic review of EUS and ERCP in acute biliary pancreatitis concluded that EUS had lower failure rates and had no complications, and the use of EUS avoided ERCP in 71.2% of cases.52

Risk stratification

The goals of using risk stratification tools in AP are to identify patients at risk for developing major outcomes, including POF, infected pancreatic necrosis, and death, and to ensure timely triaging of patients to an appropriate level of care. Existing prediction models have only moderate predictive value.53,54 Examples include simple risk stratification tools such as blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and hemoconcentration,55,56 disease-modifying patient variables (age, obesity, etc.), biomarkers (i.e., angiopoietin 2),57 and more complex clinical scoring systems such as Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II), BISAP (BUN, impaired mental status, SIRS criteria, age, pleural effusion) score, early warning system (EWS), Glasgow-Imrie score, Japanese severity score, and recently the Pancreatitis Activity Scoring System (PASS).58 Two recent guidelines affirmed the importance of predicting the severity of AP, using one or more predictive tools.1,2 The recent 2018 AGA technical review does not debate this commonsense approach, but does highlight that there is no published observational study or randomized, controlled trial (RCT) investigating whether prediction tools affect clinical outcomes.4

Recent advances in early treatment of AP

Literature review and definitions

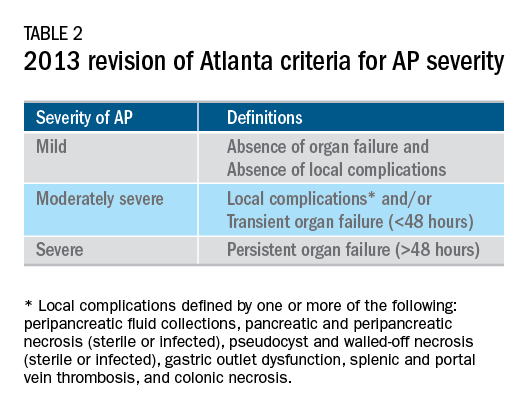

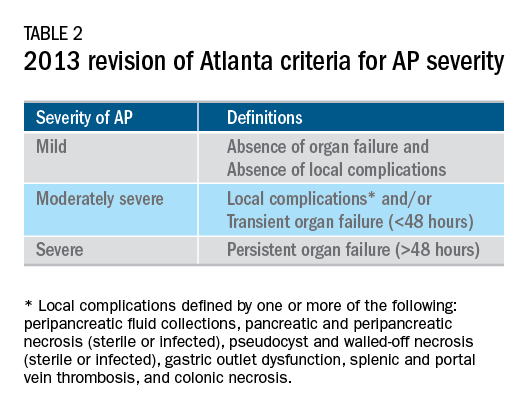

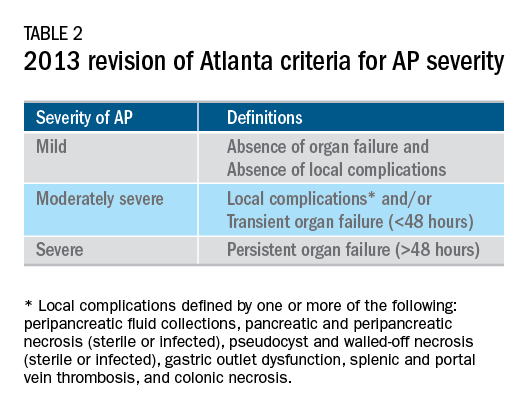

The AP literature contains heterogeneous definitions of severe AP and of what constitutes a major outcome in AP. Based on definitions of the 2013 revised Atlanta Criteria, the 2018 AGA technical review and clinical guidelines emphasized precise definitions of primary outcomes of clinical importance in AP, including death, persistent single organ failure, or persistent multiple organ failure, each requiring a duration of more than 48 hours, and infected pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis or both (Table 2).3,4

Pain management

Management of pain in AP is complex and requires a detailed discussion beyond the scope of this review, but recent clinical and translational studies raise questions about the current practice of using opioids for pain management in AP. A provocative, multicenter, retrospective cohort study reported lower 30-day mortality among critically ill patients who received epidural analgesia versus standard care without epidural analgesia.59 The possible mechanism of protection and the drugs administered are unclear. An interesting hypothesis is that the epidural cohort may have received lower exposure to morphine, which may increase gut permeability, the risk of infectious complications, and severity of AP, based on a translational study in mice.60

Intravenous fluid administration

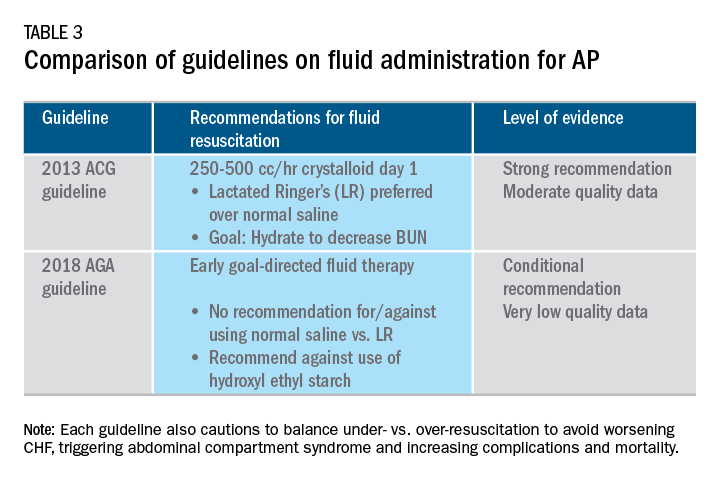

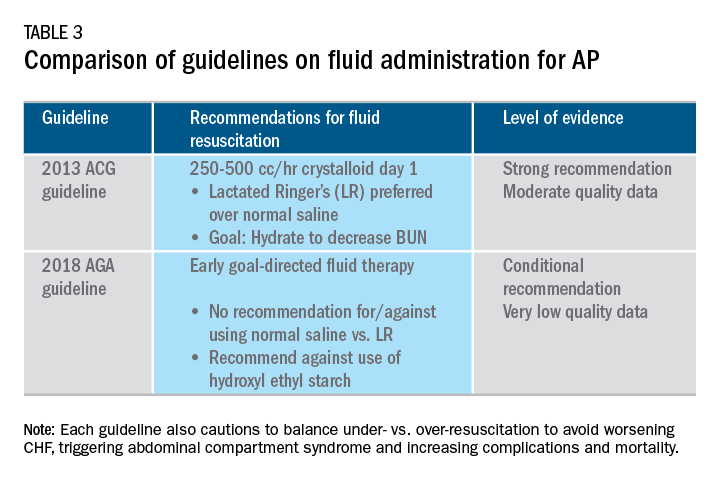

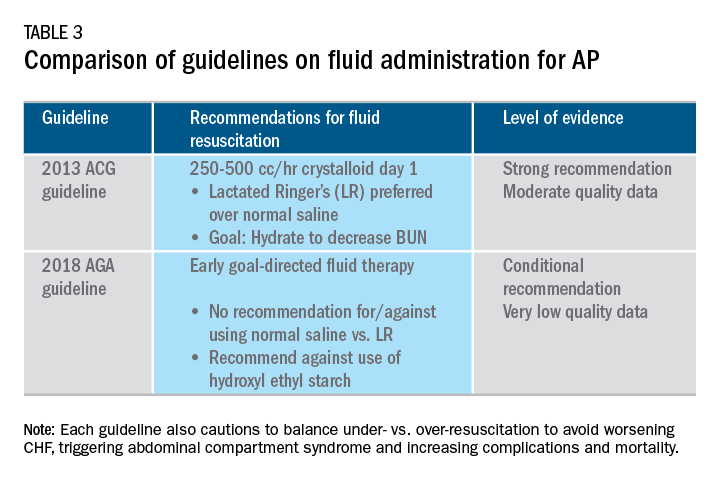

Supportive care with the use of IV fluid hydration is a mainstay of treatment for AP in the first 12-24 hours. Table 3 summarizes the guidelines in regards to IV fluid administration as delineated by the ACG and AGA guidelines on the management of pancreatitis.1,3 Guidelines advocate for early fluid resuscitation to correct intravascular depletion in order to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with AP.1,2,4 The 2018 AGA guidelines endorse a conditional recommendation for using goal-directed therapy for initial fluid management,3 do not recommend for or against normal saline versus lactated Ringer’s (LR), but do advise against the use of hydroxyethyl starch fluids.3 Consistent with these recommendations, two recent RCTs published subsequent to the prespecified time periods of the AGA technical review and guideline, observed no significant differences between LR and normal saline on clinically meaningful outcomes.61,62 The AGA guidelines acknowledge that evidence was of very-low quality in support of goal-directed therapy,3,4 which has not been shown to have a significant reduction in persistent multiple organ failure, mortality, or pancreatic necrosis, compared with usual care. As the authors noted, interpretation of the data was limited by the absence of other critical outcomes in these trials (infected pancreatic necrosis), lack of uniformity of specific outcomes and definitions of transient and POF, few trials, and risk of bias. There is a clear need for a large RCT to provide evidence to guide decision making with fluid resuscitation in AP, particularly in regard to fluid type, volume, rate, duration, endpoints, and clinical outcomes.

Feeding

More recently, the focus of nutrition in the management of AP has shifted away from patients remaining nil per os (NPO). Current guidelines advocate for early oral feeding (within 24 hours) in mild AP,3,4 in order to protect the gut-mucosal barrier. Remaining NPO when compared with early oral feeding has a 2.5-fold higher risk for interventions for necrosis.4 The recently published AGA technical review identified no significant impact on outcomes of early versus delayed oral feeding, which is consistent with observations of a landmark Dutch PYTHON trial entitled “Early versus on-demand nasoenteric tube feeding in acute pancreatitis.”4,63 There is no clear cutoff point for initiating feeding for those with severe AP. A suggested practical approach is to initiate feeding within 24-72 hours and offer enteral nutrition for those intolerant to oral feeds. In severe AP and moderately severe AP, enteral nutrition is recommended over parenteral nutrition.3,4 Enteral nutrition significantly reduces the risk of infected peripancreatic necrosis, single organ failure, and multiorgan failure.4 Finally, the AGA guidelines provide a conditional recommendation for providing enteral nutrition support through either the nasogastric or nasoenteric route.3 Further studies are required to determine the optimal timing, rate, and formulation of enteral nutrition in severe AP.

Antibiotics and probiotics

Current guidelines do not support the use of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infection in necrotizing AP and severe AP.1-3 The AGA technical review reported that prophylactic antibiotics did not reduce infected pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis, persistent single organ failure, or mortality.4 Guidelines advocate against the use of probiotics for severe AP, because of increased mortality risk.1

Timing of ERCP in acute biliary pancreatitis

There is universal agreement for offering urgent ERCP (within 24 hours) in biliary AP complicated by cholangitis.1-3,64 Figure 2 demonstrates an example of a cholangiogram completed within 24 hours of presentation of biliary AP complicated by cholangitis.

In the absence of cholangitis, the timing of ERCP for AP with persistent biliary obstruction is less clear.1-3 In line with recent guidelines, the 2018 AGA guidelines advocate against routine use of urgent ERCP for biliary AP without cholangitis,3 a conditional recommendation with overall low quality of data.4 The AGA technical review found that urgent ERCP, compared with conservative management in acute biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis had no significant effect on mortality, organ failure, infected pancreatic necrosis, and total necrotizing pancreatitis, but did significantly shorten hospital length of stay.4 There are limited data to guide decision making of when nonurgent ERCP should be performed in hospitalized patients with biliary AP with persistent obstruction and no cholangitis.3,64

Alcohol and smoking cessation

The AGA technical review advocates for brief alcohol intervention during hospitalization for alcohol-induced AP on the basis of one RCT that addresses the impact of alcohol counseling on recurrent bouts of AP4 plus evidence from a Cochrane review of alcohol-reduction strategies in primary care populations.65 Cessation of smoking – an established independent risk factor of AP – recurrent AP and chronic pancreatitis, should also be recommended as part of the management of AP.

Cholecystectomy

Evidence supports same-admission cholecystectomy for mild gallstone AP, a strong recommendation of published AGA guidelines.3 When compared with delayed cholecystectomy, same-admission cholecystectomy significantly reduced gallstone-related complications, readmissions for recurrent pancreatitis, and pancreaticobiliary complications, without having a significant impact on mortality during a 6-month follow-up period.66 Delaying cholecystectomy 6 weeks in patients with moderate-severe gallstone AP appears to reduce morbidity, including the development of infected collections, and mortality.4 An ongoing RCT, the APEC trial, aims to determine whether early ERCP with biliary sphincterotomy reduces major complications or death when compared with no intervention for biliary AP in patients at high risk of complications.67

Chemoprevention and IV fluid management of post-ERCP pancreatitis

Accumulating data support the effectiveness of chemoprevention, pancreatic stent placement, and fluid administration to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. Multiple RCTs, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews indicate that rectal NSAIDs) reduce post-ERCP pancreatitis onset68-71 and moderate-severe post-ERCP pancreatitis. Additionally, placement of a pancreatic duct stent may decrease the risk of severe post-ERCP pancreatitis in high-risk patients.3 Guidelines do not comment on fluid administrations for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis, but studies have shown that greater periprocedural IV fluid was an independent protective factor against moderate to severe PEP72 and was associated with shorter hospital length of stay.73 Recent meta-analyses and RCTs support using LR prior to ERCP to prevent PEP.74-77 Interestingly, a recent RCT shows that the combination of rectal indomethacin and LR, compared with combination placebo and normal saline reduced the risk of PEP in high-risk patients.78

Two ongoing multicenter RCTs will clarify the role of combination therapy. The Dutch FLUYT RCT aims to determine the optimal combination of rectal NSAIDs and periprocedural infusion of IV fluids to reduce the incidence of PEP and moderate-severe PEP79 and the Stent vs. Indomethacin (SVI) trial aims to determine the whether combination pancreatic stent placement plus rectal indomethacin is superior to monotherapy indomethacin for preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis in high-risk cases.80

Implications for clinical practice

The diagnosis and optimal management of AP require a systematic approach with multidisciplinary decision making. Morbidity and mortality in AP are driven by early or late POF, and the latter often is triggered by infected necrosis. Risk stratification of these patients at the point of contact is a commonsense approach to enable triaging of patients to the appropriate level of care. Regardless of pancreatitis severity, recommended treatment interventions include goal-directed IV fluid resuscitation, early feeding by mouth or enteral tube when necessary, avoidance of prophylactic antibiotics, avoidance of probiotics, and urgent ERCP for patients with acute biliary pancreatitis complicated by cholangitis. Key measures for preventing hospital readmission and pancreatitis include same-admission cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis and alcohol and smoking cessation. Preventive measures for post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients undergoing ERCP include rectal indomethacin, prophylactic pancreatic duct stent placement, and periprocedural fluid resuscitation.

Dr. Mandalia is a fellow, gastroenterology, department of internal medicine, division of gastroenterology, Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor; Dr. DiMagno is associate professor of medicine, director, comprehensive pancreas program, department of internal medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Dr. Mandalia reports no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Tenner S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1400.

2. Besseline M et al. Pancreatology. 2013;13(4, Supplement 2):e1-15.

3. Crockett SD et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):1096-101.

4. Vege SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):1103-39.

5. Peery AF et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jan;156(1):254-72.e11.

6. Krishna SG et al. Pancreas. 2017;46(4):482-8.

7. Sellers ZM et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):469-78.e1.

8. Brown A et al. JOP. 2008;9(4):408-14.

9. Fagenholz PJ et al. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(7):491.e1-.e8.

10. McNabb-Baltar J et al. Pancreas. 2014;43(5):687-91.

11. Johnson CD et al. Gut. 2004;53(9):1340-4.

12. Dellinger EP et al. Ann Surg. 2012;256(6):875-80.

13. Petrov MS et al. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(3):813-20.

14. Sternby H et al. Ann Surg. Apr 18. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002766.

15. Huh JH et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(2):178-83.

16. Wu BU et al. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(3):816-20.

17. Gardner TB et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(10):1070-6.

18. Krishna SG et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(11):1608-19.

19. Lee PJ et al. Pancreas. 2016;45(4):561-4.

20. Mandalia A et al. F1000Research. 2018 Jun 28;7.

21. Majumder S et al. Pancreas. 2015;44(4):540-6.

22. DiMagno MJ. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(11):920-2.

23. Yadav D, Whitcomb DC. Nature Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(3):131-45.

24. Samokhvalov AV et al. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(12):1996-2002.

25. Barkin JA et al. Pancreas. 2017;46(8):1035-8.

26. Chen Y-T et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(4):782-7.

27. Ramos LR et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(1):95-104.

28. Avram MM. Nephron. 1977;18(1):68-71.

29. Lankisch PG et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(4):1401-5.

30. Owyang C et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 1979;54(12):769-73.

31. Owyang Cet al. Gut. 1982;23(5):357-61.

32. Quraishi ER et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2288.

33. Vaziri ND et al. Nephron. 1987;46(4):347-9.

34. Chen HJ et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(10):1731-6.

35. Kirkegard J et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;May;154(6):1729-36.

36. Karlson BM, et al. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(2):587-92.

37. Munigala S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(7):1143-50.e1.

38. Carr RA et al. Pancreatology. 2016;16(4):469-76.

39. Li X et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18(1):89.

40. Ahmed AU et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(5):738-46.

41. Sankaran SJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1490-500.e1.

42. Berglund L et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):2969-89.

43. Catapano AL et al. Atherosclerosis. 2011;217(1):3-46.

44. Pedersen SB et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(12):1834-42.

45. Nawaz H et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(10):1497-503.

46. Banks PA et al. Gut. 2013;62(1):102-11.

47. Kondo S et al. Eur J Radiol. 2005;54(2):271-5.

48. Meeralam Y et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86(6):986-93.

49. Stimac D et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(5):997-1004.

50. Jin DX et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(10):2894-9.

51. Freeman ML. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2012;22(3):567-86.

52. De Lisi S et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23(5):367-74.

53. Di MY et al. Ann Int Med. 2016;165(7):482-90.

54. Mounzer R et al. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(7):1476-82; quiz e15-6.

55. Koutroumpakis E et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(12):1707-16.

56. Wu BU et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(1):129-35.

57. Buddingh KT et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(1):26-32.

58. Buxbaum J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(5):755-64.

59. Jabaudon M et al. Crit Car Med. 2018;46(3):e198-e205.

60. Barlass U et al. Gut. 2018;67(4):600-2.

61. Buxbaum JL et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(5):797-803.

62. de-Madaria E et al. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(1):63-72.

63. Bakker OJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(21):1983-93.

64. Tse F et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(5):Cd009779.

65. Kaner EFS et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(2):Cd004148.

66. da Costa DW et al. Lancet. 2015;386(10000):1261-8.

67. Schepers NJ et al. Trials. 2016;17:5.

68. Vadala di Prampero SF et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(12):1415-24.

69. Kubiliun NM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(7):1231-9; quiz e70-1.

70. Wan J et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17(1):43.

71. Yang C et al. Pancreatology. 2017;17(5):681-8.

72. DiMagno MJ et al. Pancreas. 2014;43(4):642-7.

73. Sagi SV et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(6):1316-20.

74. Choi JH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(1):86-92.e1.

75. Wu D et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(8):e68-e76.

76. Zhang ZF et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(3):e17-e26.

77. Park CH et al. Endoscopy 2018 Apr;50(4):378-85.

78. Mok SRS et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(5):1005-13.

79. Smeets XJN et al. Trials. 2018;19(1):207.

80. Elmunzer BJ et al. Trials. 2016;17(1):120.

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a major clinical and financial burden in the United States. Several major clinical guidelines provide evidence-based recommendations for the clinical management decisions in AP, including those from the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG; 2013),1 and the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP; 2013).2 More recently, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) released their own set of guidelines.3,4 In this update on AP, we review these guidelines and reference recent literature focused on epidemiology, risk factors, etiology, diagnosis, risk stratification, and recent advances in the early medical management of AP. Regarding the latter, we review six treatment interventions (pain management, intravenous fluid resuscitation, feeding, prophylactic antibiotics, probiotics, and timing of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in acute biliary pancreatitis) and four preventive interventions (alcohol and smoking cessation, same-admission cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis, and chemoprevention and fluid administration for post-ERCP pancreatitis [PEP]). Updates on multidisciplinary management of (infected) pancreatic necrosis is beyond the scope of this review. Table 1 summarizes the concepts discussed in this article.

Recent advances in epidemiology and evaluation of AP

Epidemiology

AP is the third most common cause of gastrointestinal-related hospitalizations and fourth most common cause of readmission in 2014.5 Recent epidemiologic studies show conflicting trends for the incidence of AP, both increasing6 and decreasing,7 likely attributable to significant differences in study designs. Importantly, multiple studies have demonstrated that hospital length of stay, costs, and mortality have declined since 2009.6,8-10

Persistent organ failure (POF), defined as organ failure lasting more than 48 hours, is the major cause of death in AP. POF, if only a single organ during AP, is associated with 27%-36% mortality; if it is multiorgan, it is associated with 47% mortality.1,11 Other factors associated with increased hospital mortality include infected pancreatic necrosis,12-14 diabetes mellitus,15 hospital-acquired infection,16 advanced age (70 years and older),17 and obesity.18 Predictive factors of 1-year mortality include readmission within 30 days, higher Charlson Comorbidity Index, and longer hospitalization.19

Risk factors

We briefly highlight recent insights into risk factors for AP (Table 1) and refer to a recent review for further discussion.20 Current and former tobacco use are independent risk factors for AP.21 The dose-response relationship of alcohol to the risk of pancreatitis is complex,22 but five standard drinks per day for 5 years is a commonly used cut-off.1,23 New evidence suggests that the relationship between the dose of alcohol and risk of AP differs by sex, linearly in men but nonlinearly (J-shaped) in women.24 Risk of AP in women was decreased with alcohol consumption of up to 40 g/day (one standard drink contains 14 g of alcohol) and increased above this amount. Cannabis is a possible risk factor for toxin-induced AP and abstinence appears to abolish risk of recurrent attacks.25

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have a 2.9-fold higher risk for AP versus non-IBD cohorts26 with the most common etiologies are from gallstones and medications.27 In patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), the risk of AP is higher in those who receive peritoneal dialysis, compared with hemodialysis28-33 and who are women, older, or have cholelithiasis or liver disease.34As recently reviewed,35 pancreatic cancer appears to be associated with first-attack pancreatitis with few exceptions.36 In this setting, the overall incidence of pancreatic cancer is low (1.5%). The risk is greatest within the first year of the attack of AP, negligible below age 40 years but steadily rising through the fifth to eighth decades.37 Pancreatic cancer screening is a conditional recommendation of the ACG guidelines in patients with unexplained AP, particularly those aged 40 years or older.1

Etiology and diagnosis

Alcohol and gallstones remain the most prevalent etiologies for AP.1 While hypertriglyceridemia accounted for 9% of AP in a systematic review of acute pancreatitis in 15 different countries,38 it is the second most common cause of acute pancreatitis in Asia (especially China).39 Figure 1 provides a breakdown of the etiologies and risk factors of pancreatitis. Importantly, it remains challenging to assign several toxic-metabolic etiologies as either a cause or risk factor for AP, particularly with regards to alcohol, smoking, and cannabis to name a few.

Guidelines and recent studies of AP raise questions about the threshold above which hypertriglyceridemia causes or poses as an important cofactor for AP. American and European societies define the threshold for triglycerides at 885-1,000 mg/dL.1,42,43 Pedersen et al. provide evidence of a graded risk of AP with hypertriglyceridemia: In multivariable analysis, adjusted hazard ratios for AP were much higher with nonfasting mild to moderately elevated plasma triglycerides (177-885 mg/dL), compared with normal values (below 89 mg/dL).44 Moreover, the risk of severe AP (developing POF) increases in proportion to triglyceride value, independent of the underlying cause of AP.45

Diagnosis of AP is derived from the revised Atlanta classification.46 The recommended timing and indications for offering cross-sectional imaging are after 48-72 hours in patients with no improvement to initial care.1 Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has better diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity, compared with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) for choledocholithiasis, and has comparable specificity.47,48 Among noninvasive imaging modalities, MRCP is more sensitive than computed tomography (CT) for diagnosing choledocholithiasis.49 Despite guideline recommendations for more selective use of pancreatic imaging in the early assessment of AP, utilization of early CT or MRCP imaging (within the first 24 hours of care) remained high during 2014-2015, compared with 2006-2007.50

ERCP is not recommended as a pure diagnostic tool, owing to the availability of other diagnostic tests and a complication rate of 5%-10% with risks involving PEP, cholangitis, perforation, and hemorrhage.51 A recent systematic review of EUS and ERCP in acute biliary pancreatitis concluded that EUS had lower failure rates and had no complications, and the use of EUS avoided ERCP in 71.2% of cases.52

Risk stratification

The goals of using risk stratification tools in AP are to identify patients at risk for developing major outcomes, including POF, infected pancreatic necrosis, and death, and to ensure timely triaging of patients to an appropriate level of care. Existing prediction models have only moderate predictive value.53,54 Examples include simple risk stratification tools such as blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and hemoconcentration,55,56 disease-modifying patient variables (age, obesity, etc.), biomarkers (i.e., angiopoietin 2),57 and more complex clinical scoring systems such as Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II), BISAP (BUN, impaired mental status, SIRS criteria, age, pleural effusion) score, early warning system (EWS), Glasgow-Imrie score, Japanese severity score, and recently the Pancreatitis Activity Scoring System (PASS).58 Two recent guidelines affirmed the importance of predicting the severity of AP, using one or more predictive tools.1,2 The recent 2018 AGA technical review does not debate this commonsense approach, but does highlight that there is no published observational study or randomized, controlled trial (RCT) investigating whether prediction tools affect clinical outcomes.4

Recent advances in early treatment of AP

Literature review and definitions

The AP literature contains heterogeneous definitions of severe AP and of what constitutes a major outcome in AP. Based on definitions of the 2013 revised Atlanta Criteria, the 2018 AGA technical review and clinical guidelines emphasized precise definitions of primary outcomes of clinical importance in AP, including death, persistent single organ failure, or persistent multiple organ failure, each requiring a duration of more than 48 hours, and infected pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis or both (Table 2).3,4

Pain management

Management of pain in AP is complex and requires a detailed discussion beyond the scope of this review, but recent clinical and translational studies raise questions about the current practice of using opioids for pain management in AP. A provocative, multicenter, retrospective cohort study reported lower 30-day mortality among critically ill patients who received epidural analgesia versus standard care without epidural analgesia.59 The possible mechanism of protection and the drugs administered are unclear. An interesting hypothesis is that the epidural cohort may have received lower exposure to morphine, which may increase gut permeability, the risk of infectious complications, and severity of AP, based on a translational study in mice.60

Intravenous fluid administration

Supportive care with the use of IV fluid hydration is a mainstay of treatment for AP in the first 12-24 hours. Table 3 summarizes the guidelines in regards to IV fluid administration as delineated by the ACG and AGA guidelines on the management of pancreatitis.1,3 Guidelines advocate for early fluid resuscitation to correct intravascular depletion in order to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with AP.1,2,4 The 2018 AGA guidelines endorse a conditional recommendation for using goal-directed therapy for initial fluid management,3 do not recommend for or against normal saline versus lactated Ringer’s (LR), but do advise against the use of hydroxyethyl starch fluids.3 Consistent with these recommendations, two recent RCTs published subsequent to the prespecified time periods of the AGA technical review and guideline, observed no significant differences between LR and normal saline on clinically meaningful outcomes.61,62 The AGA guidelines acknowledge that evidence was of very-low quality in support of goal-directed therapy,3,4 which has not been shown to have a significant reduction in persistent multiple organ failure, mortality, or pancreatic necrosis, compared with usual care. As the authors noted, interpretation of the data was limited by the absence of other critical outcomes in these trials (infected pancreatic necrosis), lack of uniformity of specific outcomes and definitions of transient and POF, few trials, and risk of bias. There is a clear need for a large RCT to provide evidence to guide decision making with fluid resuscitation in AP, particularly in regard to fluid type, volume, rate, duration, endpoints, and clinical outcomes.

Feeding

More recently, the focus of nutrition in the management of AP has shifted away from patients remaining nil per os (NPO). Current guidelines advocate for early oral feeding (within 24 hours) in mild AP,3,4 in order to protect the gut-mucosal barrier. Remaining NPO when compared with early oral feeding has a 2.5-fold higher risk for interventions for necrosis.4 The recently published AGA technical review identified no significant impact on outcomes of early versus delayed oral feeding, which is consistent with observations of a landmark Dutch PYTHON trial entitled “Early versus on-demand nasoenteric tube feeding in acute pancreatitis.”4,63 There is no clear cutoff point for initiating feeding for those with severe AP. A suggested practical approach is to initiate feeding within 24-72 hours and offer enteral nutrition for those intolerant to oral feeds. In severe AP and moderately severe AP, enteral nutrition is recommended over parenteral nutrition.3,4 Enteral nutrition significantly reduces the risk of infected peripancreatic necrosis, single organ failure, and multiorgan failure.4 Finally, the AGA guidelines provide a conditional recommendation for providing enteral nutrition support through either the nasogastric or nasoenteric route.3 Further studies are required to determine the optimal timing, rate, and formulation of enteral nutrition in severe AP.

Antibiotics and probiotics

Current guidelines do not support the use of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infection in necrotizing AP and severe AP.1-3 The AGA technical review reported that prophylactic antibiotics did not reduce infected pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis, persistent single organ failure, or mortality.4 Guidelines advocate against the use of probiotics for severe AP, because of increased mortality risk.1

Timing of ERCP in acute biliary pancreatitis

There is universal agreement for offering urgent ERCP (within 24 hours) in biliary AP complicated by cholangitis.1-3,64 Figure 2 demonstrates an example of a cholangiogram completed within 24 hours of presentation of biliary AP complicated by cholangitis.

In the absence of cholangitis, the timing of ERCP for AP with persistent biliary obstruction is less clear.1-3 In line with recent guidelines, the 2018 AGA guidelines advocate against routine use of urgent ERCP for biliary AP without cholangitis,3 a conditional recommendation with overall low quality of data.4 The AGA technical review found that urgent ERCP, compared with conservative management in acute biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis had no significant effect on mortality, organ failure, infected pancreatic necrosis, and total necrotizing pancreatitis, but did significantly shorten hospital length of stay.4 There are limited data to guide decision making of when nonurgent ERCP should be performed in hospitalized patients with biliary AP with persistent obstruction and no cholangitis.3,64

Alcohol and smoking cessation

The AGA technical review advocates for brief alcohol intervention during hospitalization for alcohol-induced AP on the basis of one RCT that addresses the impact of alcohol counseling on recurrent bouts of AP4 plus evidence from a Cochrane review of alcohol-reduction strategies in primary care populations.65 Cessation of smoking – an established independent risk factor of AP – recurrent AP and chronic pancreatitis, should also be recommended as part of the management of AP.

Cholecystectomy

Evidence supports same-admission cholecystectomy for mild gallstone AP, a strong recommendation of published AGA guidelines.3 When compared with delayed cholecystectomy, same-admission cholecystectomy significantly reduced gallstone-related complications, readmissions for recurrent pancreatitis, and pancreaticobiliary complications, without having a significant impact on mortality during a 6-month follow-up period.66 Delaying cholecystectomy 6 weeks in patients with moderate-severe gallstone AP appears to reduce morbidity, including the development of infected collections, and mortality.4 An ongoing RCT, the APEC trial, aims to determine whether early ERCP with biliary sphincterotomy reduces major complications or death when compared with no intervention for biliary AP in patients at high risk of complications.67

Chemoprevention and IV fluid management of post-ERCP pancreatitis

Accumulating data support the effectiveness of chemoprevention, pancreatic stent placement, and fluid administration to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. Multiple RCTs, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews indicate that rectal NSAIDs) reduce post-ERCP pancreatitis onset68-71 and moderate-severe post-ERCP pancreatitis. Additionally, placement of a pancreatic duct stent may decrease the risk of severe post-ERCP pancreatitis in high-risk patients.3 Guidelines do not comment on fluid administrations for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis, but studies have shown that greater periprocedural IV fluid was an independent protective factor against moderate to severe PEP72 and was associated with shorter hospital length of stay.73 Recent meta-analyses and RCTs support using LR prior to ERCP to prevent PEP.74-77 Interestingly, a recent RCT shows that the combination of rectal indomethacin and LR, compared with combination placebo and normal saline reduced the risk of PEP in high-risk patients.78

Two ongoing multicenter RCTs will clarify the role of combination therapy. The Dutch FLUYT RCT aims to determine the optimal combination of rectal NSAIDs and periprocedural infusion of IV fluids to reduce the incidence of PEP and moderate-severe PEP79 and the Stent vs. Indomethacin (SVI) trial aims to determine the whether combination pancreatic stent placement plus rectal indomethacin is superior to monotherapy indomethacin for preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis in high-risk cases.80

Implications for clinical practice

The diagnosis and optimal management of AP require a systematic approach with multidisciplinary decision making. Morbidity and mortality in AP are driven by early or late POF, and the latter often is triggered by infected necrosis. Risk stratification of these patients at the point of contact is a commonsense approach to enable triaging of patients to the appropriate level of care. Regardless of pancreatitis severity, recommended treatment interventions include goal-directed IV fluid resuscitation, early feeding by mouth or enteral tube when necessary, avoidance of prophylactic antibiotics, avoidance of probiotics, and urgent ERCP for patients with acute biliary pancreatitis complicated by cholangitis. Key measures for preventing hospital readmission and pancreatitis include same-admission cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis and alcohol and smoking cessation. Preventive measures for post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients undergoing ERCP include rectal indomethacin, prophylactic pancreatic duct stent placement, and periprocedural fluid resuscitation.

Dr. Mandalia is a fellow, gastroenterology, department of internal medicine, division of gastroenterology, Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor; Dr. DiMagno is associate professor of medicine, director, comprehensive pancreas program, department of internal medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Dr. Mandalia reports no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Tenner S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1400.

2. Besseline M et al. Pancreatology. 2013;13(4, Supplement 2):e1-15.

3. Crockett SD et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):1096-101.

4. Vege SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):1103-39.

5. Peery AF et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jan;156(1):254-72.e11.

6. Krishna SG et al. Pancreas. 2017;46(4):482-8.

7. Sellers ZM et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):469-78.e1.

8. Brown A et al. JOP. 2008;9(4):408-14.

9. Fagenholz PJ et al. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(7):491.e1-.e8.

10. McNabb-Baltar J et al. Pancreas. 2014;43(5):687-91.

11. Johnson CD et al. Gut. 2004;53(9):1340-4.

12. Dellinger EP et al. Ann Surg. 2012;256(6):875-80.

13. Petrov MS et al. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(3):813-20.

14. Sternby H et al. Ann Surg. Apr 18. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002766.

15. Huh JH et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(2):178-83.

16. Wu BU et al. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(3):816-20.

17. Gardner TB et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(10):1070-6.

18. Krishna SG et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(11):1608-19.

19. Lee PJ et al. Pancreas. 2016;45(4):561-4.

20. Mandalia A et al. F1000Research. 2018 Jun 28;7.

21. Majumder S et al. Pancreas. 2015;44(4):540-6.

22. DiMagno MJ. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(11):920-2.

23. Yadav D, Whitcomb DC. Nature Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(3):131-45.

24. Samokhvalov AV et al. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(12):1996-2002.

25. Barkin JA et al. Pancreas. 2017;46(8):1035-8.

26. Chen Y-T et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(4):782-7.

27. Ramos LR et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(1):95-104.

28. Avram MM. Nephron. 1977;18(1):68-71.

29. Lankisch PG et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(4):1401-5.

30. Owyang C et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 1979;54(12):769-73.

31. Owyang Cet al. Gut. 1982;23(5):357-61.

32. Quraishi ER et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2288.

33. Vaziri ND et al. Nephron. 1987;46(4):347-9.

34. Chen HJ et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(10):1731-6.

35. Kirkegard J et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;May;154(6):1729-36.

36. Karlson BM, et al. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(2):587-92.

37. Munigala S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(7):1143-50.e1.

38. Carr RA et al. Pancreatology. 2016;16(4):469-76.

39. Li X et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18(1):89.

40. Ahmed AU et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(5):738-46.

41. Sankaran SJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1490-500.e1.

42. Berglund L et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):2969-89.

43. Catapano AL et al. Atherosclerosis. 2011;217(1):3-46.

44. Pedersen SB et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(12):1834-42.

45. Nawaz H et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(10):1497-503.

46. Banks PA et al. Gut. 2013;62(1):102-11.

47. Kondo S et al. Eur J Radiol. 2005;54(2):271-5.

48. Meeralam Y et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86(6):986-93.

49. Stimac D et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(5):997-1004.

50. Jin DX et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(10):2894-9.

51. Freeman ML. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2012;22(3):567-86.

52. De Lisi S et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23(5):367-74.

53. Di MY et al. Ann Int Med. 2016;165(7):482-90.

54. Mounzer R et al. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(7):1476-82; quiz e15-6.

55. Koutroumpakis E et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(12):1707-16.

56. Wu BU et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(1):129-35.

57. Buddingh KT et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(1):26-32.

58. Buxbaum J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(5):755-64.

59. Jabaudon M et al. Crit Car Med. 2018;46(3):e198-e205.

60. Barlass U et al. Gut. 2018;67(4):600-2.

61. Buxbaum JL et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(5):797-803.

62. de-Madaria E et al. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(1):63-72.

63. Bakker OJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(21):1983-93.

64. Tse F et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(5):Cd009779.

65. Kaner EFS et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(2):Cd004148.

66. da Costa DW et al. Lancet. 2015;386(10000):1261-8.

67. Schepers NJ et al. Trials. 2016;17:5.

68. Vadala di Prampero SF et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(12):1415-24.

69. Kubiliun NM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(7):1231-9; quiz e70-1.

70. Wan J et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17(1):43.

71. Yang C et al. Pancreatology. 2017;17(5):681-8.

72. DiMagno MJ et al. Pancreas. 2014;43(4):642-7.

73. Sagi SV et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(6):1316-20.

74. Choi JH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(1):86-92.e1.

75. Wu D et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(8):e68-e76.

76. Zhang ZF et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(3):e17-e26.

77. Park CH et al. Endoscopy 2018 Apr;50(4):378-85.

78. Mok SRS et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(5):1005-13.

79. Smeets XJN et al. Trials. 2018;19(1):207.

80. Elmunzer BJ et al. Trials. 2016;17(1):120.

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a major clinical and financial burden in the United States. Several major clinical guidelines provide evidence-based recommendations for the clinical management decisions in AP, including those from the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG; 2013),1 and the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP; 2013).2 More recently, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) released their own set of guidelines.3,4 In this update on AP, we review these guidelines and reference recent literature focused on epidemiology, risk factors, etiology, diagnosis, risk stratification, and recent advances in the early medical management of AP. Regarding the latter, we review six treatment interventions (pain management, intravenous fluid resuscitation, feeding, prophylactic antibiotics, probiotics, and timing of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in acute biliary pancreatitis) and four preventive interventions (alcohol and smoking cessation, same-admission cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis, and chemoprevention and fluid administration for post-ERCP pancreatitis [PEP]). Updates on multidisciplinary management of (infected) pancreatic necrosis is beyond the scope of this review. Table 1 summarizes the concepts discussed in this article.

Recent advances in epidemiology and evaluation of AP

Epidemiology

AP is the third most common cause of gastrointestinal-related hospitalizations and fourth most common cause of readmission in 2014.5 Recent epidemiologic studies show conflicting trends for the incidence of AP, both increasing6 and decreasing,7 likely attributable to significant differences in study designs. Importantly, multiple studies have demonstrated that hospital length of stay, costs, and mortality have declined since 2009.6,8-10

Persistent organ failure (POF), defined as organ failure lasting more than 48 hours, is the major cause of death in AP. POF, if only a single organ during AP, is associated with 27%-36% mortality; if it is multiorgan, it is associated with 47% mortality.1,11 Other factors associated with increased hospital mortality include infected pancreatic necrosis,12-14 diabetes mellitus,15 hospital-acquired infection,16 advanced age (70 years and older),17 and obesity.18 Predictive factors of 1-year mortality include readmission within 30 days, higher Charlson Comorbidity Index, and longer hospitalization.19

Risk factors

We briefly highlight recent insights into risk factors for AP (Table 1) and refer to a recent review for further discussion.20 Current and former tobacco use are independent risk factors for AP.21 The dose-response relationship of alcohol to the risk of pancreatitis is complex,22 but five standard drinks per day for 5 years is a commonly used cut-off.1,23 New evidence suggests that the relationship between the dose of alcohol and risk of AP differs by sex, linearly in men but nonlinearly (J-shaped) in women.24 Risk of AP in women was decreased with alcohol consumption of up to 40 g/day (one standard drink contains 14 g of alcohol) and increased above this amount. Cannabis is a possible risk factor for toxin-induced AP and abstinence appears to abolish risk of recurrent attacks.25

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have a 2.9-fold higher risk for AP versus non-IBD cohorts26 with the most common etiologies are from gallstones and medications.27 In patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), the risk of AP is higher in those who receive peritoneal dialysis, compared with hemodialysis28-33 and who are women, older, or have cholelithiasis or liver disease.34As recently reviewed,35 pancreatic cancer appears to be associated with first-attack pancreatitis with few exceptions.36 In this setting, the overall incidence of pancreatic cancer is low (1.5%). The risk is greatest within the first year of the attack of AP, negligible below age 40 years but steadily rising through the fifth to eighth decades.37 Pancreatic cancer screening is a conditional recommendation of the ACG guidelines in patients with unexplained AP, particularly those aged 40 years or older.1

Etiology and diagnosis

Alcohol and gallstones remain the most prevalent etiologies for AP.1 While hypertriglyceridemia accounted for 9% of AP in a systematic review of acute pancreatitis in 15 different countries,38 it is the second most common cause of acute pancreatitis in Asia (especially China).39 Figure 1 provides a breakdown of the etiologies and risk factors of pancreatitis. Importantly, it remains challenging to assign several toxic-metabolic etiologies as either a cause or risk factor for AP, particularly with regards to alcohol, smoking, and cannabis to name a few.

Guidelines and recent studies of AP raise questions about the threshold above which hypertriglyceridemia causes or poses as an important cofactor for AP. American and European societies define the threshold for triglycerides at 885-1,000 mg/dL.1,42,43 Pedersen et al. provide evidence of a graded risk of AP with hypertriglyceridemia: In multivariable analysis, adjusted hazard ratios for AP were much higher with nonfasting mild to moderately elevated plasma triglycerides (177-885 mg/dL), compared with normal values (below 89 mg/dL).44 Moreover, the risk of severe AP (developing POF) increases in proportion to triglyceride value, independent of the underlying cause of AP.45

Diagnosis of AP is derived from the revised Atlanta classification.46 The recommended timing and indications for offering cross-sectional imaging are after 48-72 hours in patients with no improvement to initial care.1 Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has better diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity, compared with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) for choledocholithiasis, and has comparable specificity.47,48 Among noninvasive imaging modalities, MRCP is more sensitive than computed tomography (CT) for diagnosing choledocholithiasis.49 Despite guideline recommendations for more selective use of pancreatic imaging in the early assessment of AP, utilization of early CT or MRCP imaging (within the first 24 hours of care) remained high during 2014-2015, compared with 2006-2007.50

ERCP is not recommended as a pure diagnostic tool, owing to the availability of other diagnostic tests and a complication rate of 5%-10% with risks involving PEP, cholangitis, perforation, and hemorrhage.51 A recent systematic review of EUS and ERCP in acute biliary pancreatitis concluded that EUS had lower failure rates and had no complications, and the use of EUS avoided ERCP in 71.2% of cases.52

Risk stratification

The goals of using risk stratification tools in AP are to identify patients at risk for developing major outcomes, including POF, infected pancreatic necrosis, and death, and to ensure timely triaging of patients to an appropriate level of care. Existing prediction models have only moderate predictive value.53,54 Examples include simple risk stratification tools such as blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and hemoconcentration,55,56 disease-modifying patient variables (age, obesity, etc.), biomarkers (i.e., angiopoietin 2),57 and more complex clinical scoring systems such as Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II), BISAP (BUN, impaired mental status, SIRS criteria, age, pleural effusion) score, early warning system (EWS), Glasgow-Imrie score, Japanese severity score, and recently the Pancreatitis Activity Scoring System (PASS).58 Two recent guidelines affirmed the importance of predicting the severity of AP, using one or more predictive tools.1,2 The recent 2018 AGA technical review does not debate this commonsense approach, but does highlight that there is no published observational study or randomized, controlled trial (RCT) investigating whether prediction tools affect clinical outcomes.4

Recent advances in early treatment of AP

Literature review and definitions

The AP literature contains heterogeneous definitions of severe AP and of what constitutes a major outcome in AP. Based on definitions of the 2013 revised Atlanta Criteria, the 2018 AGA technical review and clinical guidelines emphasized precise definitions of primary outcomes of clinical importance in AP, including death, persistent single organ failure, or persistent multiple organ failure, each requiring a duration of more than 48 hours, and infected pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis or both (Table 2).3,4

Pain management

Management of pain in AP is complex and requires a detailed discussion beyond the scope of this review, but recent clinical and translational studies raise questions about the current practice of using opioids for pain management in AP. A provocative, multicenter, retrospective cohort study reported lower 30-day mortality among critically ill patients who received epidural analgesia versus standard care without epidural analgesia.59 The possible mechanism of protection and the drugs administered are unclear. An interesting hypothesis is that the epidural cohort may have received lower exposure to morphine, which may increase gut permeability, the risk of infectious complications, and severity of AP, based on a translational study in mice.60

Intravenous fluid administration

Supportive care with the use of IV fluid hydration is a mainstay of treatment for AP in the first 12-24 hours. Table 3 summarizes the guidelines in regards to IV fluid administration as delineated by the ACG and AGA guidelines on the management of pancreatitis.1,3 Guidelines advocate for early fluid resuscitation to correct intravascular depletion in order to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with AP.1,2,4 The 2018 AGA guidelines endorse a conditional recommendation for using goal-directed therapy for initial fluid management,3 do not recommend for or against normal saline versus lactated Ringer’s (LR), but do advise against the use of hydroxyethyl starch fluids.3 Consistent with these recommendations, two recent RCTs published subsequent to the prespecified time periods of the AGA technical review and guideline, observed no significant differences between LR and normal saline on clinically meaningful outcomes.61,62 The AGA guidelines acknowledge that evidence was of very-low quality in support of goal-directed therapy,3,4 which has not been shown to have a significant reduction in persistent multiple organ failure, mortality, or pancreatic necrosis, compared with usual care. As the authors noted, interpretation of the data was limited by the absence of other critical outcomes in these trials (infected pancreatic necrosis), lack of uniformity of specific outcomes and definitions of transient and POF, few trials, and risk of bias. There is a clear need for a large RCT to provide evidence to guide decision making with fluid resuscitation in AP, particularly in regard to fluid type, volume, rate, duration, endpoints, and clinical outcomes.

Feeding

More recently, the focus of nutrition in the management of AP has shifted away from patients remaining nil per os (NPO). Current guidelines advocate for early oral feeding (within 24 hours) in mild AP,3,4 in order to protect the gut-mucosal barrier. Remaining NPO when compared with early oral feeding has a 2.5-fold higher risk for interventions for necrosis.4 The recently published AGA technical review identified no significant impact on outcomes of early versus delayed oral feeding, which is consistent with observations of a landmark Dutch PYTHON trial entitled “Early versus on-demand nasoenteric tube feeding in acute pancreatitis.”4,63 There is no clear cutoff point for initiating feeding for those with severe AP. A suggested practical approach is to initiate feeding within 24-72 hours and offer enteral nutrition for those intolerant to oral feeds. In severe AP and moderately severe AP, enteral nutrition is recommended over parenteral nutrition.3,4 Enteral nutrition significantly reduces the risk of infected peripancreatic necrosis, single organ failure, and multiorgan failure.4 Finally, the AGA guidelines provide a conditional recommendation for providing enteral nutrition support through either the nasogastric or nasoenteric route.3 Further studies are required to determine the optimal timing, rate, and formulation of enteral nutrition in severe AP.

Antibiotics and probiotics

Current guidelines do not support the use of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infection in necrotizing AP and severe AP.1-3 The AGA technical review reported that prophylactic antibiotics did not reduce infected pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis, persistent single organ failure, or mortality.4 Guidelines advocate against the use of probiotics for severe AP, because of increased mortality risk.1

Timing of ERCP in acute biliary pancreatitis

There is universal agreement for offering urgent ERCP (within 24 hours) in biliary AP complicated by cholangitis.1-3,64 Figure 2 demonstrates an example of a cholangiogram completed within 24 hours of presentation of biliary AP complicated by cholangitis.

In the absence of cholangitis, the timing of ERCP for AP with persistent biliary obstruction is less clear.1-3 In line with recent guidelines, the 2018 AGA guidelines advocate against routine use of urgent ERCP for biliary AP without cholangitis,3 a conditional recommendation with overall low quality of data.4 The AGA technical review found that urgent ERCP, compared with conservative management in acute biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis had no significant effect on mortality, organ failure, infected pancreatic necrosis, and total necrotizing pancreatitis, but did significantly shorten hospital length of stay.4 There are limited data to guide decision making of when nonurgent ERCP should be performed in hospitalized patients with biliary AP with persistent obstruction and no cholangitis.3,64

Alcohol and smoking cessation

The AGA technical review advocates for brief alcohol intervention during hospitalization for alcohol-induced AP on the basis of one RCT that addresses the impact of alcohol counseling on recurrent bouts of AP4 plus evidence from a Cochrane review of alcohol-reduction strategies in primary care populations.65 Cessation of smoking – an established independent risk factor of AP – recurrent AP and chronic pancreatitis, should also be recommended as part of the management of AP.

Cholecystectomy

Evidence supports same-admission cholecystectomy for mild gallstone AP, a strong recommendation of published AGA guidelines.3 When compared with delayed cholecystectomy, same-admission cholecystectomy significantly reduced gallstone-related complications, readmissions for recurrent pancreatitis, and pancreaticobiliary complications, without having a significant impact on mortality during a 6-month follow-up period.66 Delaying cholecystectomy 6 weeks in patients with moderate-severe gallstone AP appears to reduce morbidity, including the development of infected collections, and mortality.4 An ongoing RCT, the APEC trial, aims to determine whether early ERCP with biliary sphincterotomy reduces major complications or death when compared with no intervention for biliary AP in patients at high risk of complications.67

Chemoprevention and IV fluid management of post-ERCP pancreatitis

Accumulating data support the effectiveness of chemoprevention, pancreatic stent placement, and fluid administration to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. Multiple RCTs, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews indicate that rectal NSAIDs) reduce post-ERCP pancreatitis onset68-71 and moderate-severe post-ERCP pancreatitis. Additionally, placement of a pancreatic duct stent may decrease the risk of severe post-ERCP pancreatitis in high-risk patients.3 Guidelines do not comment on fluid administrations for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis, but studies have shown that greater periprocedural IV fluid was an independent protective factor against moderate to severe PEP72 and was associated with shorter hospital length of stay.73 Recent meta-analyses and RCTs support using LR prior to ERCP to prevent PEP.74-77 Interestingly, a recent RCT shows that the combination of rectal indomethacin and LR, compared with combination placebo and normal saline reduced the risk of PEP in high-risk patients.78

Two ongoing multicenter RCTs will clarify the role of combination therapy. The Dutch FLUYT RCT aims to determine the optimal combination of rectal NSAIDs and periprocedural infusion of IV fluids to reduce the incidence of PEP and moderate-severe PEP79 and the Stent vs. Indomethacin (SVI) trial aims to determine the whether combination pancreatic stent placement plus rectal indomethacin is superior to monotherapy indomethacin for preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis in high-risk cases.80

Implications for clinical practice

The diagnosis and optimal management of AP require a systematic approach with multidisciplinary decision making. Morbidity and mortality in AP are driven by early or late POF, and the latter often is triggered by infected necrosis. Risk stratification of these patients at the point of contact is a commonsense approach to enable triaging of patients to the appropriate level of care. Regardless of pancreatitis severity, recommended treatment interventions include goal-directed IV fluid resuscitation, early feeding by mouth or enteral tube when necessary, avoidance of prophylactic antibiotics, avoidance of probiotics, and urgent ERCP for patients with acute biliary pancreatitis complicated by cholangitis. Key measures for preventing hospital readmission and pancreatitis include same-admission cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis and alcohol and smoking cessation. Preventive measures for post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients undergoing ERCP include rectal indomethacin, prophylactic pancreatic duct stent placement, and periprocedural fluid resuscitation.

Dr. Mandalia is a fellow, gastroenterology, department of internal medicine, division of gastroenterology, Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor; Dr. DiMagno is associate professor of medicine, director, comprehensive pancreas program, department of internal medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Dr. Mandalia reports no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Tenner S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1400.

2. Besseline M et al. Pancreatology. 2013;13(4, Supplement 2):e1-15.

3. Crockett SD et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):1096-101.

4. Vege SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):1103-39.

5. Peery AF et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jan;156(1):254-72.e11.

6. Krishna SG et al. Pancreas. 2017;46(4):482-8.

7. Sellers ZM et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):469-78.e1.

8. Brown A et al. JOP. 2008;9(4):408-14.

9. Fagenholz PJ et al. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(7):491.e1-.e8.

10. McNabb-Baltar J et al. Pancreas. 2014;43(5):687-91.

11. Johnson CD et al. Gut. 2004;53(9):1340-4.

12. Dellinger EP et al. Ann Surg. 2012;256(6):875-80.

13. Petrov MS et al. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(3):813-20.

14. Sternby H et al. Ann Surg. Apr 18. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002766.

15. Huh JH et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(2):178-83.

16. Wu BU et al. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(3):816-20.

17. Gardner TB et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(10):1070-6.

18. Krishna SG et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(11):1608-19.

19. Lee PJ et al. Pancreas. 2016;45(4):561-4.

20. Mandalia A et al. F1000Research. 2018 Jun 28;7.

21. Majumder S et al. Pancreas. 2015;44(4):540-6.

22. DiMagno MJ. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(11):920-2.

23. Yadav D, Whitcomb DC. Nature Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(3):131-45.

24. Samokhvalov AV et al. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(12):1996-2002.

25. Barkin JA et al. Pancreas. 2017;46(8):1035-8.

26. Chen Y-T et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(4):782-7.

27. Ramos LR et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(1):95-104.

28. Avram MM. Nephron. 1977;18(1):68-71.

29. Lankisch PG et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(4):1401-5.

30. Owyang C et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 1979;54(12):769-73.

31. Owyang Cet al. Gut. 1982;23(5):357-61.

32. Quraishi ER et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2288.

33. Vaziri ND et al. Nephron. 1987;46(4):347-9.

34. Chen HJ et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(10):1731-6.

35. Kirkegard J et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;May;154(6):1729-36.

36. Karlson BM, et al. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(2):587-92.

37. Munigala S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(7):1143-50.e1.

38. Carr RA et al. Pancreatology. 2016;16(4):469-76.

39. Li X et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18(1):89.

40. Ahmed AU et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(5):738-46.

41. Sankaran SJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1490-500.e1.

42. Berglund L et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):2969-89.

43. Catapano AL et al. Atherosclerosis. 2011;217(1):3-46.

44. Pedersen SB et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(12):1834-42.

45. Nawaz H et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(10):1497-503.

46. Banks PA et al. Gut. 2013;62(1):102-11.

47. Kondo S et al. Eur J Radiol. 2005;54(2):271-5.

48. Meeralam Y et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86(6):986-93.

49. Stimac D et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(5):997-1004.

50. Jin DX et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(10):2894-9.

51. Freeman ML. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2012;22(3):567-86.

52. De Lisi S et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23(5):367-74.

53. Di MY et al. Ann Int Med. 2016;165(7):482-90.

54. Mounzer R et al. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(7):1476-82; quiz e15-6.

55. Koutroumpakis E et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(12):1707-16.

56. Wu BU et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(1):129-35.

57. Buddingh KT et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(1):26-32.

58. Buxbaum J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(5):755-64.

59. Jabaudon M et al. Crit Car Med. 2018;46(3):e198-e205.

60. Barlass U et al. Gut. 2018;67(4):600-2.

61. Buxbaum JL et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(5):797-803.

62. de-Madaria E et al. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(1):63-72.

63. Bakker OJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(21):1983-93.

64. Tse F et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(5):Cd009779.

65. Kaner EFS et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(2):Cd004148.

66. da Costa DW et al. Lancet. 2015;386(10000):1261-8.

67. Schepers NJ et al. Trials. 2016;17:5.

68. Vadala di Prampero SF et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(12):1415-24.

69. Kubiliun NM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(7):1231-9; quiz e70-1.

70. Wan J et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17(1):43.

71. Yang C et al. Pancreatology. 2017;17(5):681-8.

72. DiMagno MJ et al. Pancreas. 2014;43(4):642-7.

73. Sagi SV et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(6):1316-20.

74. Choi JH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(1):86-92.e1.

75. Wu D et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(8):e68-e76.

76. Zhang ZF et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(3):e17-e26.

77. Park CH et al. Endoscopy 2018 Apr;50(4):378-85.

78. Mok SRS et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(5):1005-13.

79. Smeets XJN et al. Trials. 2018;19(1):207.

80. Elmunzer BJ et al. Trials. 2016;17(1):120.

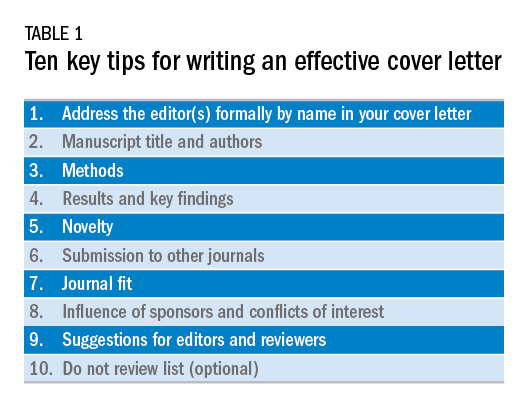

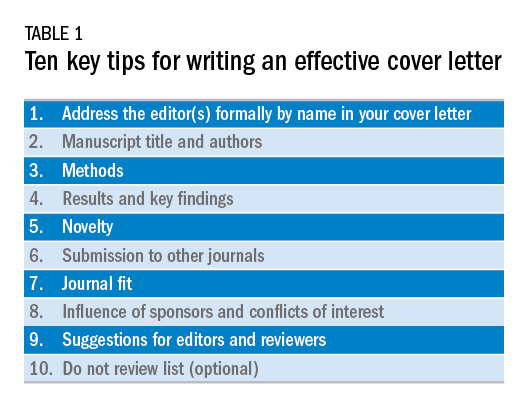

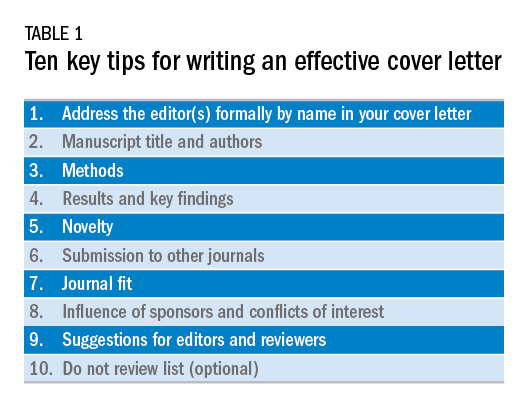

Writing an effective cover letter

You have run your experiments, analyzed your data, and finished your manuscript, but now you are asked to write a cover letter for journal submission. How do you effectively convey your message in a cover letter? To understand how to gain the editors’ support for your paper, let us first discuss the role of this letter.