User login

Planning for future college expenses with 529 accounts

Financial planning for families can involve multiple investment goals. The big ones usually are investing for retirement and for your children’s college expenses. With any investment strategy, once you have identified an investment goal, you will want to utilize the right investment account to achieve that goal. If investing for future college expenses is your goal, then one of the investment accounts you will want to utilize is called a 529 plan.

What is a 529 plan?

A 529 plan is a tax-favored account authorized by Section 529 of the Internal Revenue Code and sponsored by a state or educational institution. These plans have specific tax-saving features to them, compared with other taxable accounts, which are listed below. To begin with, there are two types of 529 plans: prepaid tuition plans and education savings plans. Every state has at least one type of 529 plan. Additionally, some private colleges sponsor a prepaid tuition plan.

Prepaid tuition plan

The first type of 529 account is a prepaid tuition plan. These let an account owner purchase college credits (or units) for participating colleges or universities at today’s prices to be used for the student’s future tuition charges. The states that sponsor prepaid plans do so primarily for the benefit of their in-state public colleges and universities. Things to know about the prepaid plans: States may or may not guarantee that the prepaid units keep up with increases in tuition charges. The plan also may have a state residency requirement. If the student decides not to attend one of the eligible schools, the equivalent payout may be less than had the student attended one of the participating institutions. There are no federal guarantees on the state prepaid plans and they are not available for private elementary and high school programs.

Education savings plan

The second type of 529 account is an education savings plan, an investment account into which you can invest your after-tax dollars. The intent with these accounts is to grow the balance for use at a future date. These are tax-deferred accounts, which means each year the interest, dividends, and capital gains created within the account do not show up on your tax return. If the funds are used for a “qualified” higher-education expense, then gains on the account are not taxed upon withdrawal.

As with most investments, the longer your money is invested, the more time it has to grow via accumulated interest, dividends, and appreciation. The larger the growth, the larger the tax benefits. This offers a tremendous advantage for a high-income and high-tax bracket household to invest for future goals (such as private school tuition or college expenses). By contrast, if you had invested in a fully taxable account, you would be subject to taxes each year on the interest, dividends, and capital gain distributions. Also, with taxable accounts, your investments would be subject to capital gains tax on the growth when they are sold to pay for those future expenses.

An account owner may choose among a range of investment options that the 529 plan provides. These are typically individual mutual funds or preformed mutual fund portfolios. The portfolios may have a fixed allocation percentage that stays the same over time or come “age-weighted,” meaning the investment allocation becomes more conservative the closer the student gets to college age when withdrawals would occur. This is a similar approach to the “target retirement date” offerings one sees in retirement accounts.

If one is using the 529 account for the student’s elementary or high school years, the investment time frame may be shorter and necessitate a more conservative approach, as the time for withdrawals would be nearer than the college years. As with most investments, the account can lose value based on investment performance.

Owner versus beneficiary

There are two parties to any 529 plan account: The account owner, who has control over the account and can name the beneficiary to the account, and the beneficiary (the student). The account owner can change beneficiaries on the account and can even name themselves as the beneficiary. One can name anyone as the beneficiary (e.g., child, friend, relative, yourself). You can be proactive by creating an account and naming yourself the beneficiary now, before switching to your child in the future. The account owner can live in one state with the beneficiary in another and invest in the 529 from a third state, and the student may eventually go to an educational institution in a fourth state. The 529 education savings account is not limited to any specific college, as a prepaid plan may be.

Withdrawals from 529s

If a 529 account withdrawal is for qualified higher education expenses or tuition for elementary or secondary schools, earnings are not subject to federal income tax or, in many cases, state income tax. Qualified withdrawals need to take place in the same tax year as the qualified expense.

Withdrawals not used for qualified higher education expenses in that year are considered “nonqualified” and would be subject to tax and 10% penalty on the earnings. State and local taxes may apply as well.

You can use the proceeds from the account free of taxes for the following qualified higher-education expenses:

- Tuition and school fees for both full and part time students at an eligible college, university, trade, or vocational institution.

- Room and board if the student is enrolled at more than half-time status. The amount up to the school’s room and board charges are eligible if paid directly to the school or to a landlord if living in nonschool housing. If actual charges to the landlord exceed the schools’ charges, then the amount above the school’s charges would be considered an excess withdrawal.

- Required books, supplies, and equipment for the academic program. Computer and technology equipment, printers, and required software, and such related services as Internet access also are qualified expenses.

- Private elementary or secondary school tuition up to $10,000 annually also is a qualified expense for 529 withdrawals.

Health insurance for the student and transportation-related costs to and from the school are not qualified expenses.

Contributions and fees

Like all investments, the fees associated with a 529 account need to be considered, as excess fees lower the investment returns. Prepaid tuition plans may charge initial application, transaction, and ongoing administrative fees. Investment 529 accounts may also have administrative costs such as program management fees, per-transaction fees, and the underlying investment expense ratios. Some states have broker-sold plans as well as direct-sold plans. Broker-sold plans can be purchased only through a broker and have the additional expenses associated with that either in the form of a load (sales charge) or higher expense ratio.

Contributions to a 529 plan can only be made in cash. If you currently have other investments, they need to be liquidated first (with the associated tax consequence) and then the proceeds invested into the 529 plan. Establishing the account and ongoing contributions are subject to gift tax limits ($15,000 for 2019). A married couple may make a “joint gift” to the account to double the limit. The 529 plans also allow the owner to front-load the account in 1 year with up to 5 years’ worth of gift limit contributions all at once. This lump sum is treated for tax reasons as a pro-rata 5 consecutive years of contributions all at once. Any additional gifts to that beneficiary during that year and the remaining four would be subject to gift tax issues if it means the annual gift limits were exceeded. Contributions are considered a “completed gift” for gift- and estate-tax purposes even though the account owner retains an element of control. The up-front 5-year gift election is available only on 529 accounts and is a great way for parents and grandparents (hint-hint) to reduce their estates and get a significant initial balance into the account. This can come in handy for those who may have procrastinated working toward this investment goal and need to catch up.

If the beneficiary does not need all or some of the funds for qualified higher education expenses, the account owner has options: One can change beneficiary to another relative who may need the funds or keep the account going and eventually add a grandchild as a beneficiary. Graduate school expenses also are eligible. A student can have multiple 529 accounts set up in their name.

Additional tax considerations

Education Tax Credits like the American Opportunity Tax Credit and the Lifetime Learning Credit have income phase-outs that you may or may not be eligible for based on your income. Education expenses used to qualify for the tax-free withdrawal from a 529 plan cannot be used to claim these tax credits. Several states offer state income tax deductions for contributions to a 529 plan but may have eligibility limited to the in-state plan only. It is wise to look to your own state’s plan first to see if that is the case and consider that as a factor when you choose a plan right for you. Refer to your tax professional for your eligibility.

In conclusion, 529 savings plans represent a tax-free way to grow your investments for future education expenses down the road, even if you don’t have a child yet. Speak to your financial adviser to learn about plans and contribution schedules that work with your current and future investing goals.

Good sources for further information include:

- www.savingforcollege.com.

- www.irs.gov/forms-pubs/about-publication-970.

- www.finra.org/investors/saving-college.

Mr. Clancy is director of financial planning, Drexel University College of Medicine.

Financial planning for families can involve multiple investment goals. The big ones usually are investing for retirement and for your children’s college expenses. With any investment strategy, once you have identified an investment goal, you will want to utilize the right investment account to achieve that goal. If investing for future college expenses is your goal, then one of the investment accounts you will want to utilize is called a 529 plan.

What is a 529 plan?

A 529 plan is a tax-favored account authorized by Section 529 of the Internal Revenue Code and sponsored by a state or educational institution. These plans have specific tax-saving features to them, compared with other taxable accounts, which are listed below. To begin with, there are two types of 529 plans: prepaid tuition plans and education savings plans. Every state has at least one type of 529 plan. Additionally, some private colleges sponsor a prepaid tuition plan.

Prepaid tuition plan

The first type of 529 account is a prepaid tuition plan. These let an account owner purchase college credits (or units) for participating colleges or universities at today’s prices to be used for the student’s future tuition charges. The states that sponsor prepaid plans do so primarily for the benefit of their in-state public colleges and universities. Things to know about the prepaid plans: States may or may not guarantee that the prepaid units keep up with increases in tuition charges. The plan also may have a state residency requirement. If the student decides not to attend one of the eligible schools, the equivalent payout may be less than had the student attended one of the participating institutions. There are no federal guarantees on the state prepaid plans and they are not available for private elementary and high school programs.

Education savings plan

The second type of 529 account is an education savings plan, an investment account into which you can invest your after-tax dollars. The intent with these accounts is to grow the balance for use at a future date. These are tax-deferred accounts, which means each year the interest, dividends, and capital gains created within the account do not show up on your tax return. If the funds are used for a “qualified” higher-education expense, then gains on the account are not taxed upon withdrawal.

As with most investments, the longer your money is invested, the more time it has to grow via accumulated interest, dividends, and appreciation. The larger the growth, the larger the tax benefits. This offers a tremendous advantage for a high-income and high-tax bracket household to invest for future goals (such as private school tuition or college expenses). By contrast, if you had invested in a fully taxable account, you would be subject to taxes each year on the interest, dividends, and capital gain distributions. Also, with taxable accounts, your investments would be subject to capital gains tax on the growth when they are sold to pay for those future expenses.

An account owner may choose among a range of investment options that the 529 plan provides. These are typically individual mutual funds or preformed mutual fund portfolios. The portfolios may have a fixed allocation percentage that stays the same over time or come “age-weighted,” meaning the investment allocation becomes more conservative the closer the student gets to college age when withdrawals would occur. This is a similar approach to the “target retirement date” offerings one sees in retirement accounts.

If one is using the 529 account for the student’s elementary or high school years, the investment time frame may be shorter and necessitate a more conservative approach, as the time for withdrawals would be nearer than the college years. As with most investments, the account can lose value based on investment performance.

Owner versus beneficiary

There are two parties to any 529 plan account: The account owner, who has control over the account and can name the beneficiary to the account, and the beneficiary (the student). The account owner can change beneficiaries on the account and can even name themselves as the beneficiary. One can name anyone as the beneficiary (e.g., child, friend, relative, yourself). You can be proactive by creating an account and naming yourself the beneficiary now, before switching to your child in the future. The account owner can live in one state with the beneficiary in another and invest in the 529 from a third state, and the student may eventually go to an educational institution in a fourth state. The 529 education savings account is not limited to any specific college, as a prepaid plan may be.

Withdrawals from 529s

If a 529 account withdrawal is for qualified higher education expenses or tuition for elementary or secondary schools, earnings are not subject to federal income tax or, in many cases, state income tax. Qualified withdrawals need to take place in the same tax year as the qualified expense.

Withdrawals not used for qualified higher education expenses in that year are considered “nonqualified” and would be subject to tax and 10% penalty on the earnings. State and local taxes may apply as well.

You can use the proceeds from the account free of taxes for the following qualified higher-education expenses:

- Tuition and school fees for both full and part time students at an eligible college, university, trade, or vocational institution.

- Room and board if the student is enrolled at more than half-time status. The amount up to the school’s room and board charges are eligible if paid directly to the school or to a landlord if living in nonschool housing. If actual charges to the landlord exceed the schools’ charges, then the amount above the school’s charges would be considered an excess withdrawal.

- Required books, supplies, and equipment for the academic program. Computer and technology equipment, printers, and required software, and such related services as Internet access also are qualified expenses.

- Private elementary or secondary school tuition up to $10,000 annually also is a qualified expense for 529 withdrawals.

Health insurance for the student and transportation-related costs to and from the school are not qualified expenses.

Contributions and fees

Like all investments, the fees associated with a 529 account need to be considered, as excess fees lower the investment returns. Prepaid tuition plans may charge initial application, transaction, and ongoing administrative fees. Investment 529 accounts may also have administrative costs such as program management fees, per-transaction fees, and the underlying investment expense ratios. Some states have broker-sold plans as well as direct-sold plans. Broker-sold plans can be purchased only through a broker and have the additional expenses associated with that either in the form of a load (sales charge) or higher expense ratio.

Contributions to a 529 plan can only be made in cash. If you currently have other investments, they need to be liquidated first (with the associated tax consequence) and then the proceeds invested into the 529 plan. Establishing the account and ongoing contributions are subject to gift tax limits ($15,000 for 2019). A married couple may make a “joint gift” to the account to double the limit. The 529 plans also allow the owner to front-load the account in 1 year with up to 5 years’ worth of gift limit contributions all at once. This lump sum is treated for tax reasons as a pro-rata 5 consecutive years of contributions all at once. Any additional gifts to that beneficiary during that year and the remaining four would be subject to gift tax issues if it means the annual gift limits were exceeded. Contributions are considered a “completed gift” for gift- and estate-tax purposes even though the account owner retains an element of control. The up-front 5-year gift election is available only on 529 accounts and is a great way for parents and grandparents (hint-hint) to reduce their estates and get a significant initial balance into the account. This can come in handy for those who may have procrastinated working toward this investment goal and need to catch up.

If the beneficiary does not need all or some of the funds for qualified higher education expenses, the account owner has options: One can change beneficiary to another relative who may need the funds or keep the account going and eventually add a grandchild as a beneficiary. Graduate school expenses also are eligible. A student can have multiple 529 accounts set up in their name.

Additional tax considerations

Education Tax Credits like the American Opportunity Tax Credit and the Lifetime Learning Credit have income phase-outs that you may or may not be eligible for based on your income. Education expenses used to qualify for the tax-free withdrawal from a 529 plan cannot be used to claim these tax credits. Several states offer state income tax deductions for contributions to a 529 plan but may have eligibility limited to the in-state plan only. It is wise to look to your own state’s plan first to see if that is the case and consider that as a factor when you choose a plan right for you. Refer to your tax professional for your eligibility.

In conclusion, 529 savings plans represent a tax-free way to grow your investments for future education expenses down the road, even if you don’t have a child yet. Speak to your financial adviser to learn about plans and contribution schedules that work with your current and future investing goals.

Good sources for further information include:

- www.savingforcollege.com.

- www.irs.gov/forms-pubs/about-publication-970.

- www.finra.org/investors/saving-college.

Mr. Clancy is director of financial planning, Drexel University College of Medicine.

Financial planning for families can involve multiple investment goals. The big ones usually are investing for retirement and for your children’s college expenses. With any investment strategy, once you have identified an investment goal, you will want to utilize the right investment account to achieve that goal. If investing for future college expenses is your goal, then one of the investment accounts you will want to utilize is called a 529 plan.

What is a 529 plan?

A 529 plan is a tax-favored account authorized by Section 529 of the Internal Revenue Code and sponsored by a state or educational institution. These plans have specific tax-saving features to them, compared with other taxable accounts, which are listed below. To begin with, there are two types of 529 plans: prepaid tuition plans and education savings plans. Every state has at least one type of 529 plan. Additionally, some private colleges sponsor a prepaid tuition plan.

Prepaid tuition plan

The first type of 529 account is a prepaid tuition plan. These let an account owner purchase college credits (or units) for participating colleges or universities at today’s prices to be used for the student’s future tuition charges. The states that sponsor prepaid plans do so primarily for the benefit of their in-state public colleges and universities. Things to know about the prepaid plans: States may or may not guarantee that the prepaid units keep up with increases in tuition charges. The plan also may have a state residency requirement. If the student decides not to attend one of the eligible schools, the equivalent payout may be less than had the student attended one of the participating institutions. There are no federal guarantees on the state prepaid plans and they are not available for private elementary and high school programs.

Education savings plan

The second type of 529 account is an education savings plan, an investment account into which you can invest your after-tax dollars. The intent with these accounts is to grow the balance for use at a future date. These are tax-deferred accounts, which means each year the interest, dividends, and capital gains created within the account do not show up on your tax return. If the funds are used for a “qualified” higher-education expense, then gains on the account are not taxed upon withdrawal.

As with most investments, the longer your money is invested, the more time it has to grow via accumulated interest, dividends, and appreciation. The larger the growth, the larger the tax benefits. This offers a tremendous advantage for a high-income and high-tax bracket household to invest for future goals (such as private school tuition or college expenses). By contrast, if you had invested in a fully taxable account, you would be subject to taxes each year on the interest, dividends, and capital gain distributions. Also, with taxable accounts, your investments would be subject to capital gains tax on the growth when they are sold to pay for those future expenses.

An account owner may choose among a range of investment options that the 529 plan provides. These are typically individual mutual funds or preformed mutual fund portfolios. The portfolios may have a fixed allocation percentage that stays the same over time or come “age-weighted,” meaning the investment allocation becomes more conservative the closer the student gets to college age when withdrawals would occur. This is a similar approach to the “target retirement date” offerings one sees in retirement accounts.

If one is using the 529 account for the student’s elementary or high school years, the investment time frame may be shorter and necessitate a more conservative approach, as the time for withdrawals would be nearer than the college years. As with most investments, the account can lose value based on investment performance.

Owner versus beneficiary

There are two parties to any 529 plan account: The account owner, who has control over the account and can name the beneficiary to the account, and the beneficiary (the student). The account owner can change beneficiaries on the account and can even name themselves as the beneficiary. One can name anyone as the beneficiary (e.g., child, friend, relative, yourself). You can be proactive by creating an account and naming yourself the beneficiary now, before switching to your child in the future. The account owner can live in one state with the beneficiary in another and invest in the 529 from a third state, and the student may eventually go to an educational institution in a fourth state. The 529 education savings account is not limited to any specific college, as a prepaid plan may be.

Withdrawals from 529s

If a 529 account withdrawal is for qualified higher education expenses or tuition for elementary or secondary schools, earnings are not subject to federal income tax or, in many cases, state income tax. Qualified withdrawals need to take place in the same tax year as the qualified expense.

Withdrawals not used for qualified higher education expenses in that year are considered “nonqualified” and would be subject to tax and 10% penalty on the earnings. State and local taxes may apply as well.

You can use the proceeds from the account free of taxes for the following qualified higher-education expenses:

- Tuition and school fees for both full and part time students at an eligible college, university, trade, or vocational institution.

- Room and board if the student is enrolled at more than half-time status. The amount up to the school’s room and board charges are eligible if paid directly to the school or to a landlord if living in nonschool housing. If actual charges to the landlord exceed the schools’ charges, then the amount above the school’s charges would be considered an excess withdrawal.

- Required books, supplies, and equipment for the academic program. Computer and technology equipment, printers, and required software, and such related services as Internet access also are qualified expenses.

- Private elementary or secondary school tuition up to $10,000 annually also is a qualified expense for 529 withdrawals.

Health insurance for the student and transportation-related costs to and from the school are not qualified expenses.

Contributions and fees

Like all investments, the fees associated with a 529 account need to be considered, as excess fees lower the investment returns. Prepaid tuition plans may charge initial application, transaction, and ongoing administrative fees. Investment 529 accounts may also have administrative costs such as program management fees, per-transaction fees, and the underlying investment expense ratios. Some states have broker-sold plans as well as direct-sold plans. Broker-sold plans can be purchased only through a broker and have the additional expenses associated with that either in the form of a load (sales charge) or higher expense ratio.

Contributions to a 529 plan can only be made in cash. If you currently have other investments, they need to be liquidated first (with the associated tax consequence) and then the proceeds invested into the 529 plan. Establishing the account and ongoing contributions are subject to gift tax limits ($15,000 for 2019). A married couple may make a “joint gift” to the account to double the limit. The 529 plans also allow the owner to front-load the account in 1 year with up to 5 years’ worth of gift limit contributions all at once. This lump sum is treated for tax reasons as a pro-rata 5 consecutive years of contributions all at once. Any additional gifts to that beneficiary during that year and the remaining four would be subject to gift tax issues if it means the annual gift limits were exceeded. Contributions are considered a “completed gift” for gift- and estate-tax purposes even though the account owner retains an element of control. The up-front 5-year gift election is available only on 529 accounts and is a great way for parents and grandparents (hint-hint) to reduce their estates and get a significant initial balance into the account. This can come in handy for those who may have procrastinated working toward this investment goal and need to catch up.

If the beneficiary does not need all or some of the funds for qualified higher education expenses, the account owner has options: One can change beneficiary to another relative who may need the funds or keep the account going and eventually add a grandchild as a beneficiary. Graduate school expenses also are eligible. A student can have multiple 529 accounts set up in their name.

Additional tax considerations

Education Tax Credits like the American Opportunity Tax Credit and the Lifetime Learning Credit have income phase-outs that you may or may not be eligible for based on your income. Education expenses used to qualify for the tax-free withdrawal from a 529 plan cannot be used to claim these tax credits. Several states offer state income tax deductions for contributions to a 529 plan but may have eligibility limited to the in-state plan only. It is wise to look to your own state’s plan first to see if that is the case and consider that as a factor when you choose a plan right for you. Refer to your tax professional for your eligibility.

In conclusion, 529 savings plans represent a tax-free way to grow your investments for future education expenses down the road, even if you don’t have a child yet. Speak to your financial adviser to learn about plans and contribution schedules that work with your current and future investing goals.

Good sources for further information include:

- www.savingforcollege.com.

- www.irs.gov/forms-pubs/about-publication-970.

- www.finra.org/investors/saving-college.

Mr. Clancy is director of financial planning, Drexel University College of Medicine.

New feature debuts, how to address reviewer criticism, and more!

Dear Colleagues,

The November issue of The New Gastroenterologist is packed with some great articles! First, this issue’s In Focus article addresses the increasingly important topic of endoscopic management of obesity. In the article, the authors, Pichamol Jirapinyo and Christopher Thompson (Brigham and Women’s Hospital), provide an outstanding overview of the approved and up-and-coming endoscopic therapies that can be used to help treat the obesity epidemic. This is an area that we will inevitably see more of in our practices.

A new feature in this issue of The New Gastroenterologist is a column focused on early career gastroenterologists who are going into private practice, which was curated in conjunction with the Digestive Health Physicians Association. This month’s article by Fred Rosenberg (North Shore Endoscopy Center) provides an overview of private practice gastroenterology models. I look forward to making this column a recurring feature of future issues.

Additionally, using their wealth of experience, former CGH editor in chief Hashem El-Serag and current CGH editor in chief Fasiha Kanwal (Baylor) provide an enlightening piece on how to address reviewer criticism, which will no doubt be very helpful for those of us looking to publish. There is also a helpful article about grant writing tips authored by two successfully funded early career basic scientists, Arthur Beyder (Mayo) and Christina Twyman-Saint Victor (University of Pennsylvania).

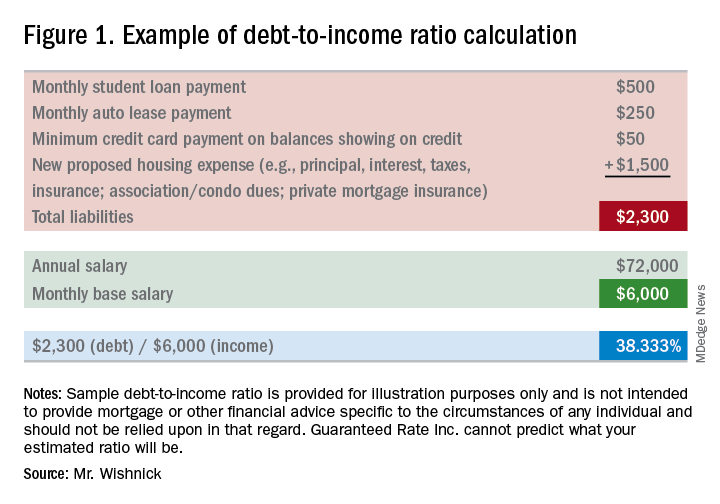

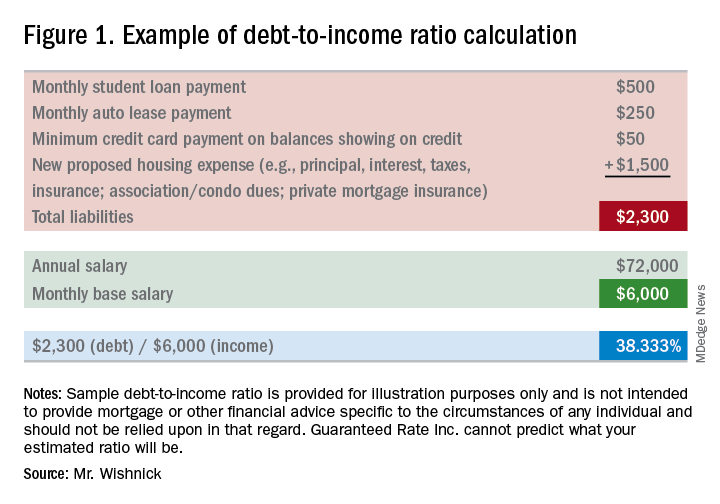

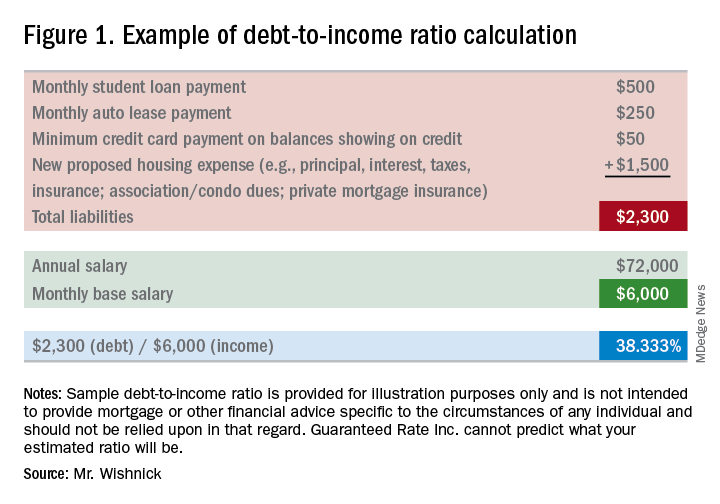

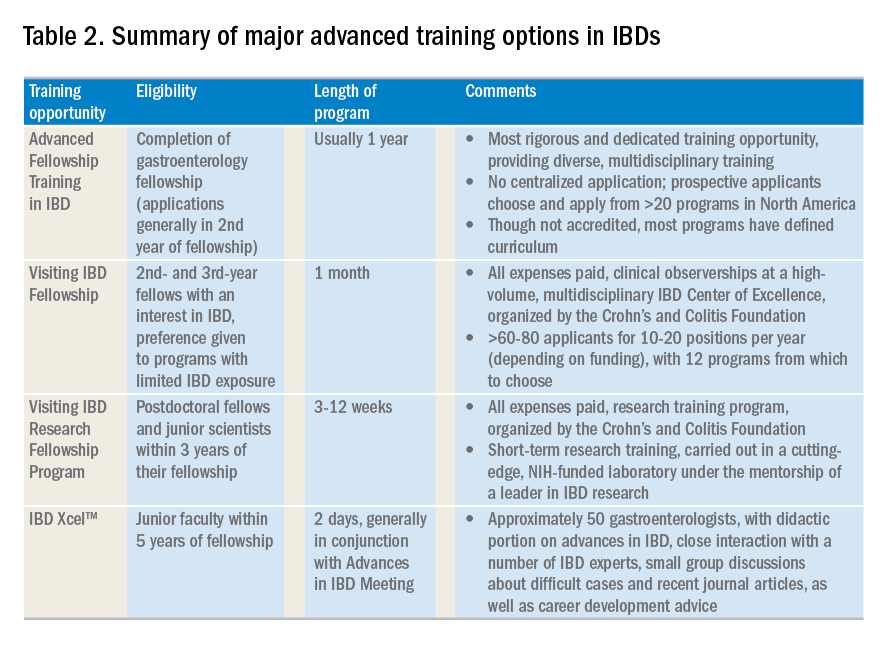

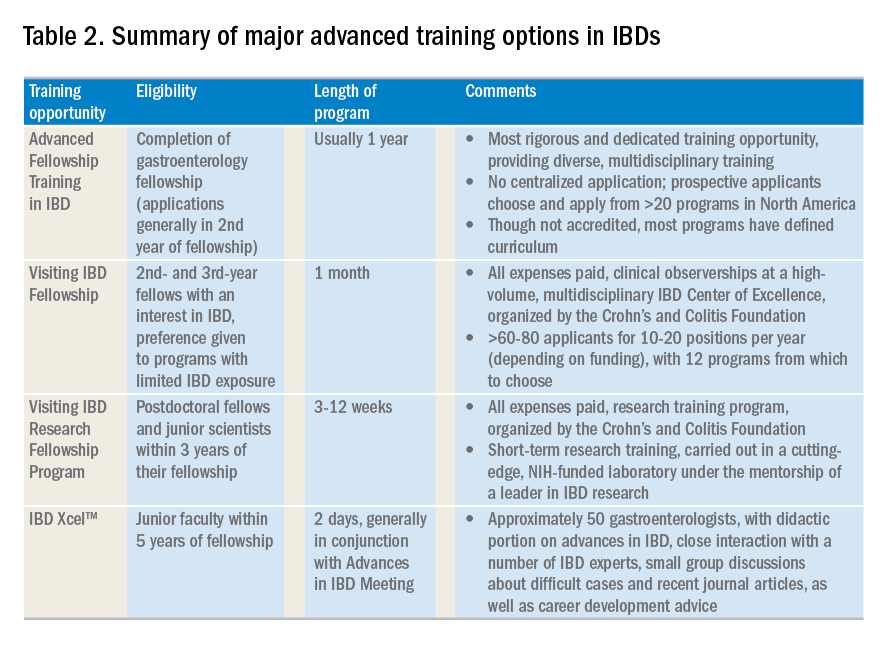

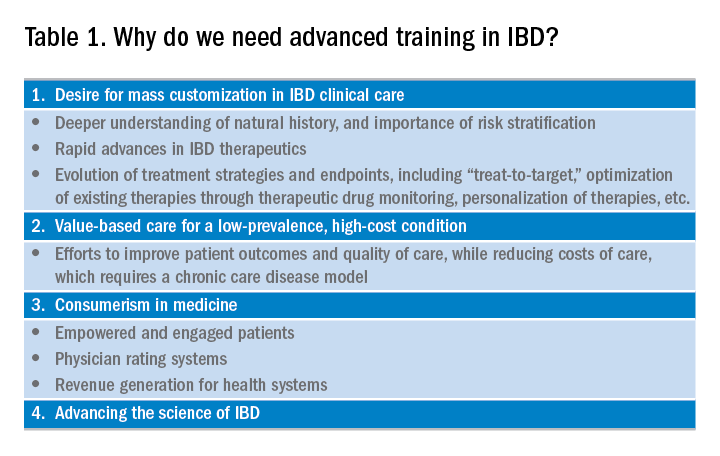

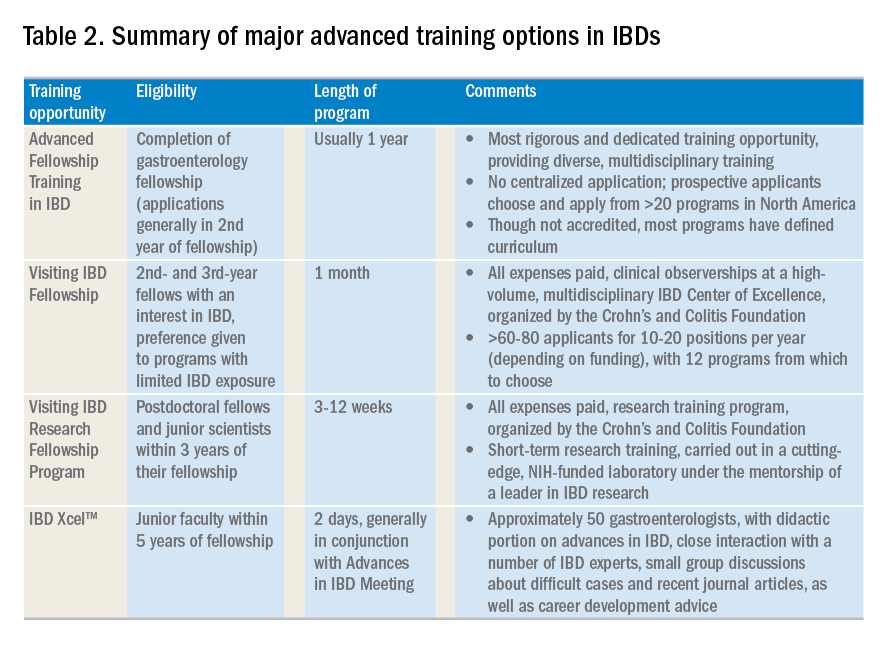

For those considering pursuing extra training in IBD either during or after GI fellowship, Siddharth Singh (UCSD) goes through the different advanced training options that are now available in IBD. And finally, as many are laying down roots in new places, buying a house will almost inevitably be on the horizon. To help guide you through the mortgage preapproval process, Rob Wishnick (Guaranteed Rate) provides some useful insights from his many years of experience in the home loan industry.

Please check out “In Case You Missed It” to see other articles from the last quarter in AGA publications that may be of interest to you. And, if you have any ideas or want to contribute to The New Gastroenterologist, please contact me at [email protected] or the managing editor, Ryan Farrell, at [email protected].

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Dr. Katona is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Dear Colleagues,

The November issue of The New Gastroenterologist is packed with some great articles! First, this issue’s In Focus article addresses the increasingly important topic of endoscopic management of obesity. In the article, the authors, Pichamol Jirapinyo and Christopher Thompson (Brigham and Women’s Hospital), provide an outstanding overview of the approved and up-and-coming endoscopic therapies that can be used to help treat the obesity epidemic. This is an area that we will inevitably see more of in our practices.

A new feature in this issue of The New Gastroenterologist is a column focused on early career gastroenterologists who are going into private practice, which was curated in conjunction with the Digestive Health Physicians Association. This month’s article by Fred Rosenberg (North Shore Endoscopy Center) provides an overview of private practice gastroenterology models. I look forward to making this column a recurring feature of future issues.

Additionally, using their wealth of experience, former CGH editor in chief Hashem El-Serag and current CGH editor in chief Fasiha Kanwal (Baylor) provide an enlightening piece on how to address reviewer criticism, which will no doubt be very helpful for those of us looking to publish. There is also a helpful article about grant writing tips authored by two successfully funded early career basic scientists, Arthur Beyder (Mayo) and Christina Twyman-Saint Victor (University of Pennsylvania).

For those considering pursuing extra training in IBD either during or after GI fellowship, Siddharth Singh (UCSD) goes through the different advanced training options that are now available in IBD. And finally, as many are laying down roots in new places, buying a house will almost inevitably be on the horizon. To help guide you through the mortgage preapproval process, Rob Wishnick (Guaranteed Rate) provides some useful insights from his many years of experience in the home loan industry.

Please check out “In Case You Missed It” to see other articles from the last quarter in AGA publications that may be of interest to you. And, if you have any ideas or want to contribute to The New Gastroenterologist, please contact me at [email protected] or the managing editor, Ryan Farrell, at [email protected].

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Dr. Katona is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Dear Colleagues,

The November issue of The New Gastroenterologist is packed with some great articles! First, this issue’s In Focus article addresses the increasingly important topic of endoscopic management of obesity. In the article, the authors, Pichamol Jirapinyo and Christopher Thompson (Brigham and Women’s Hospital), provide an outstanding overview of the approved and up-and-coming endoscopic therapies that can be used to help treat the obesity epidemic. This is an area that we will inevitably see more of in our practices.

A new feature in this issue of The New Gastroenterologist is a column focused on early career gastroenterologists who are going into private practice, which was curated in conjunction with the Digestive Health Physicians Association. This month’s article by Fred Rosenberg (North Shore Endoscopy Center) provides an overview of private practice gastroenterology models. I look forward to making this column a recurring feature of future issues.

Additionally, using their wealth of experience, former CGH editor in chief Hashem El-Serag and current CGH editor in chief Fasiha Kanwal (Baylor) provide an enlightening piece on how to address reviewer criticism, which will no doubt be very helpful for those of us looking to publish. There is also a helpful article about grant writing tips authored by two successfully funded early career basic scientists, Arthur Beyder (Mayo) and Christina Twyman-Saint Victor (University of Pennsylvania).

For those considering pursuing extra training in IBD either during or after GI fellowship, Siddharth Singh (UCSD) goes through the different advanced training options that are now available in IBD. And finally, as many are laying down roots in new places, buying a house will almost inevitably be on the horizon. To help guide you through the mortgage preapproval process, Rob Wishnick (Guaranteed Rate) provides some useful insights from his many years of experience in the home loan industry.

Please check out “In Case You Missed It” to see other articles from the last quarter in AGA publications that may be of interest to you. And, if you have any ideas or want to contribute to The New Gastroenterologist, please contact me at [email protected] or the managing editor, Ryan Farrell, at [email protected].

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Dr. Katona is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Endoscopic management of obesity

Editor's Note

Gastroenterologists are becoming increasingly involved in the management of obesity. While prior therapy for obesity was mainly based on lifestyle changes, medication, or surgery, the new and exciting field of endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies has recently garnered incredible attention and momentum.

In this quarter’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, Pichamol Jirapinyo and Christopher Thompson (Brigham and Women’s Hospital) provide an outstanding overview of the gastric and small bowel endoscopic interventions that are either already approved for use in obesity or currently being studied. This field is moving incredibly fast, and knowledge and understanding of these endoscopic therapies for obesity will undoubtedly be important for our field.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Introduction

Obesity is a rising pandemic. As of 2016, 93.3 million U.S. adults had obesity, representing 39.8% of our adult population.1 It is estimated that approximately $147 billion is spent annually on caring for patients with obesity. Traditionally, the management of obesity includes lifestyle therapy (diet and exercise), pharmacotherapy (six Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for obesity), and bariatric surgery (sleeve gastrectomy [SG] and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass [RYGB]). Nevertheless, intensive lifestyle intervention and pharmacotherapy are associated with approximately 3.1%-6.6% total weight loss (TWL),2-7 and bariatric surgery is associated with 20%-33.3% TWL.8 However, less than 2% of patients who are eligible for bariatric surgery elect to undergo surgery, leaving a large proportion of patients with obesity untreated or undertreated.9

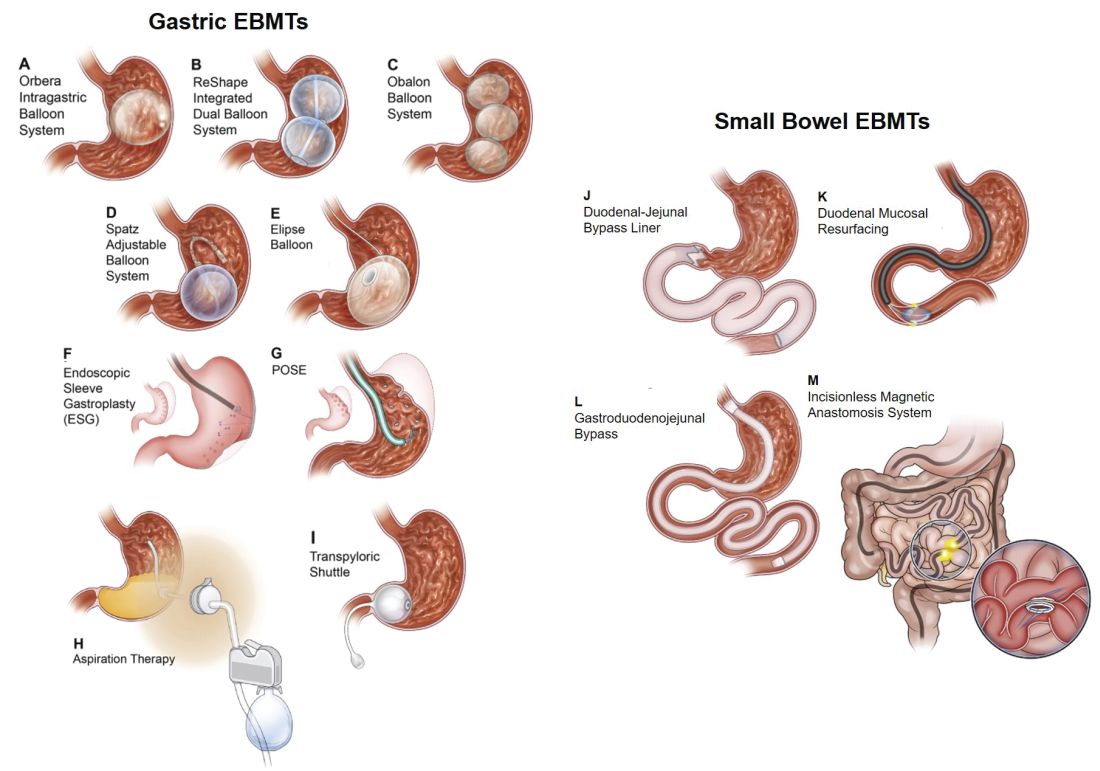

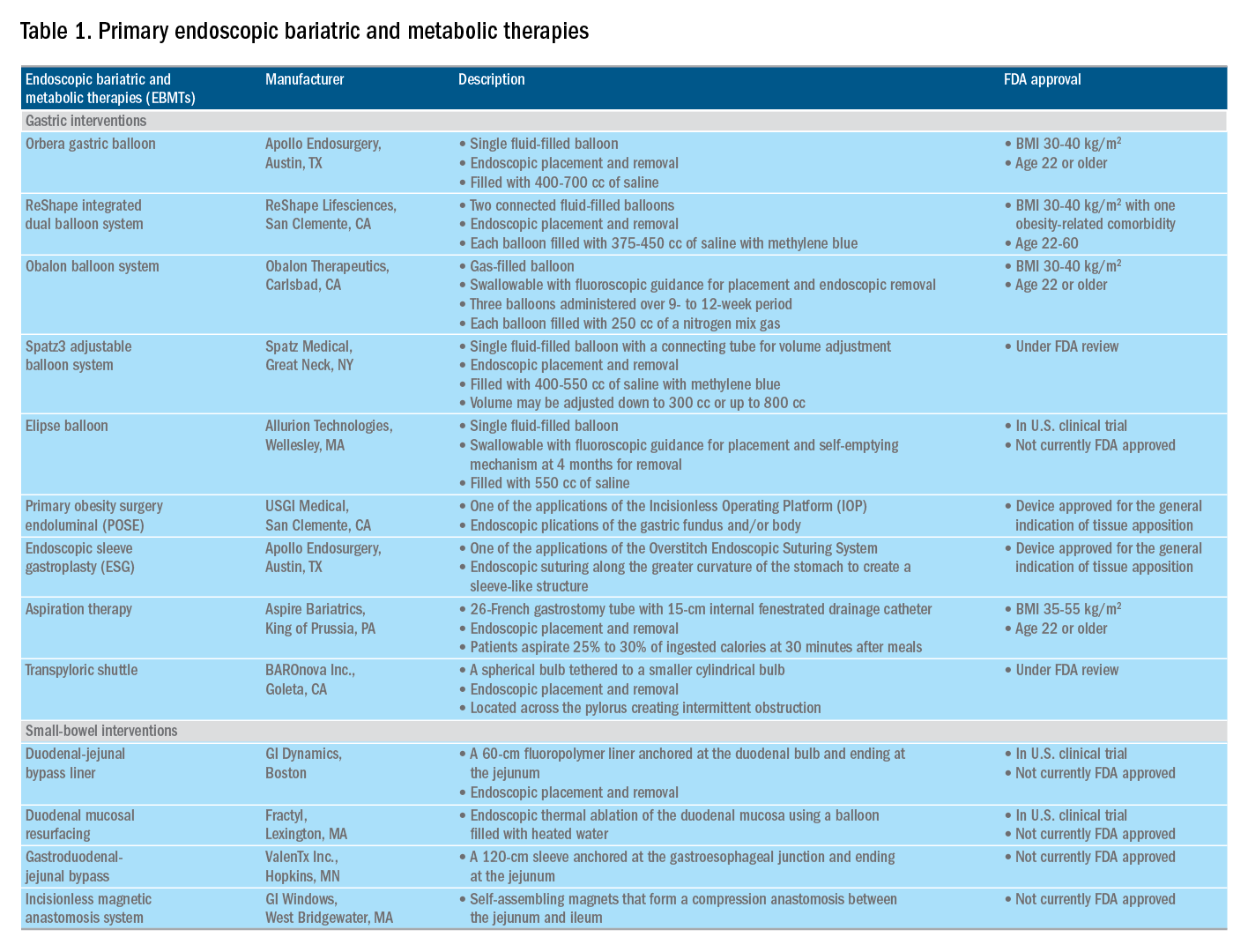

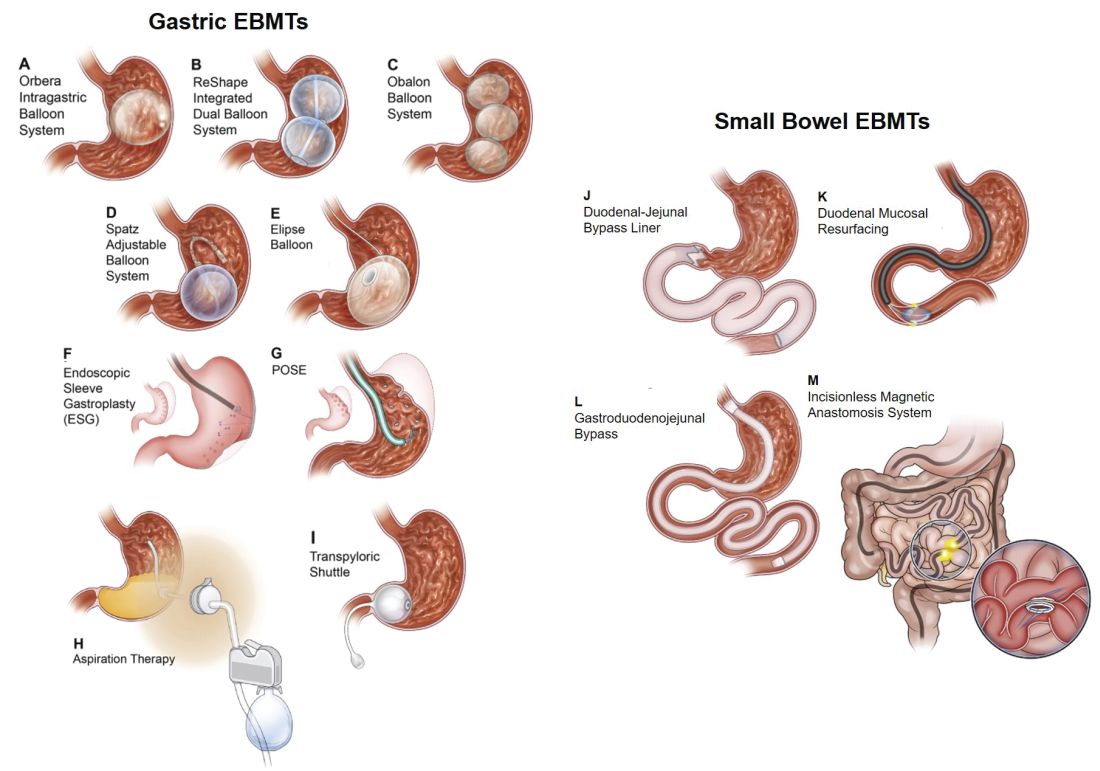

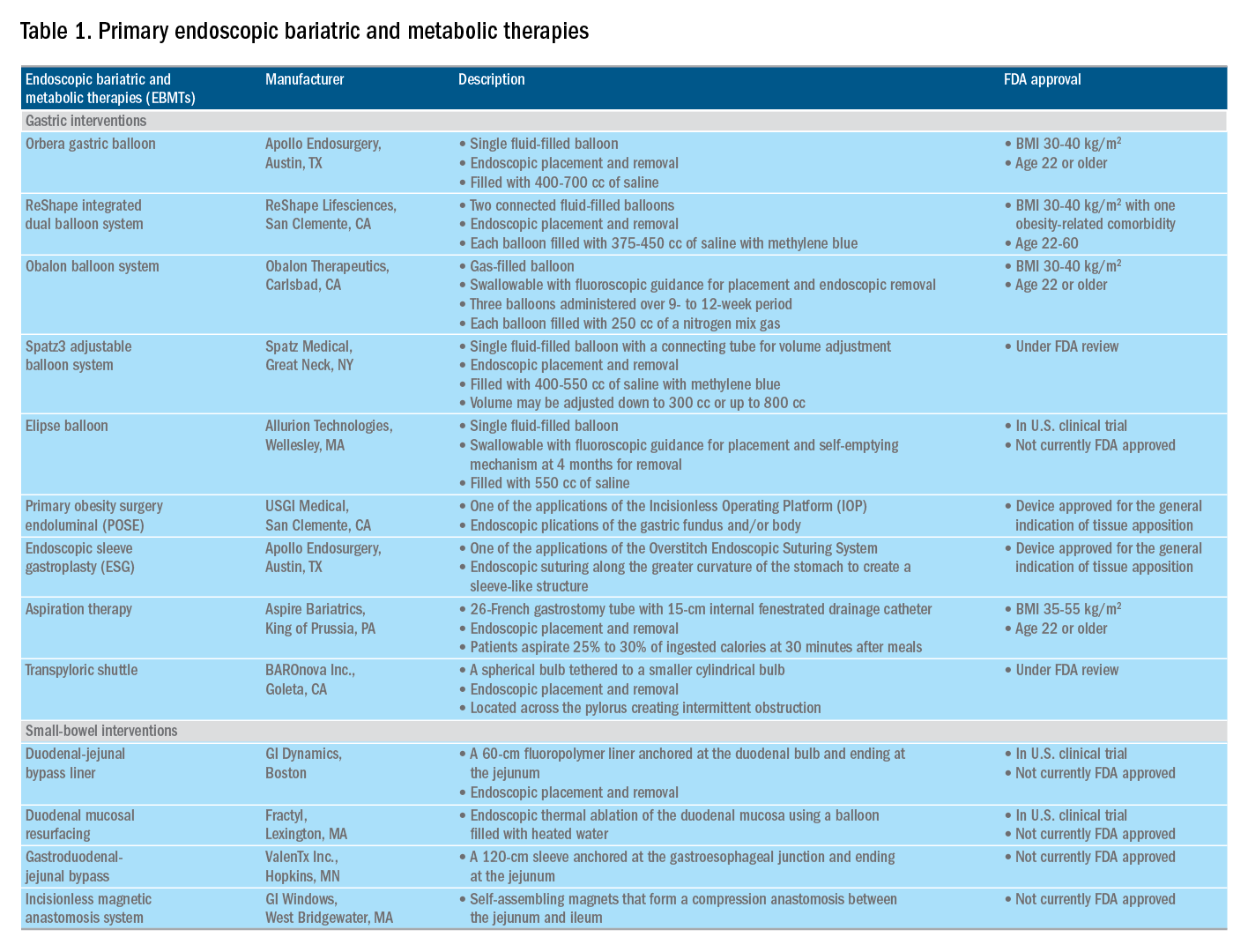

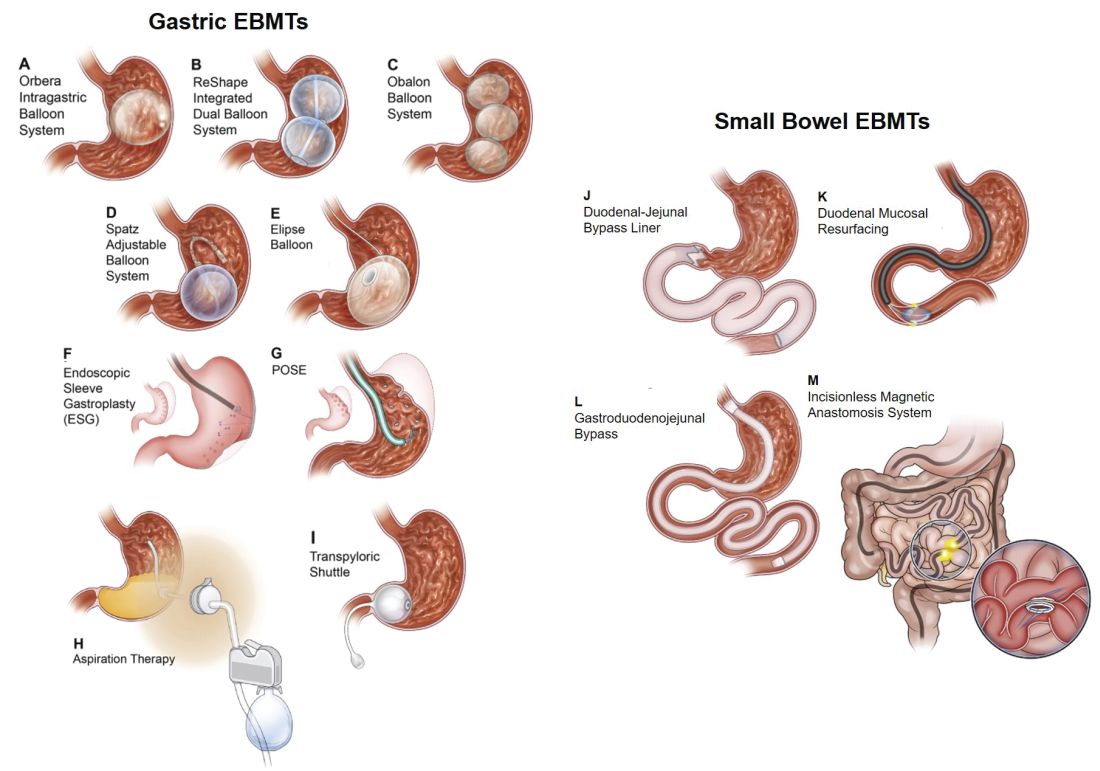

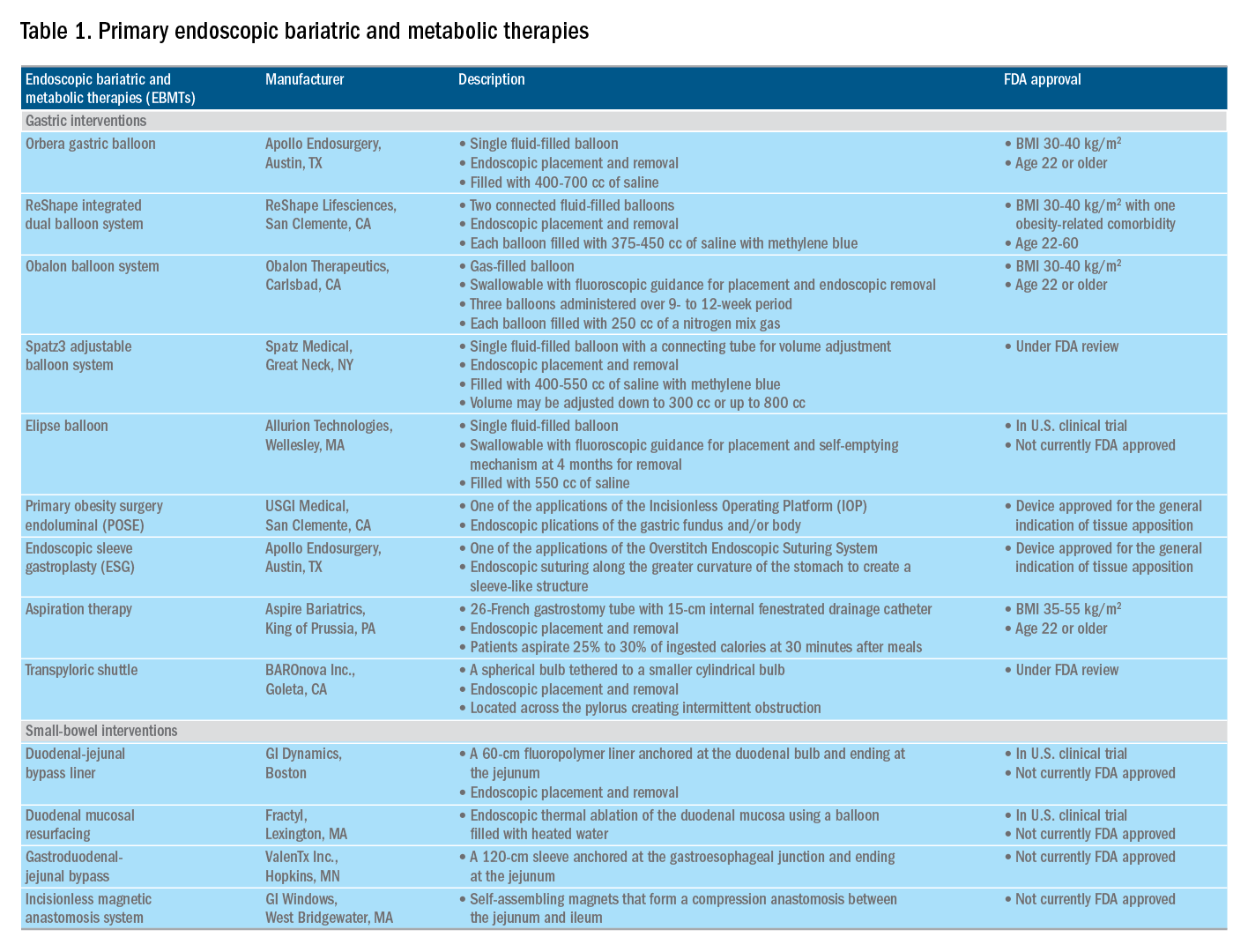

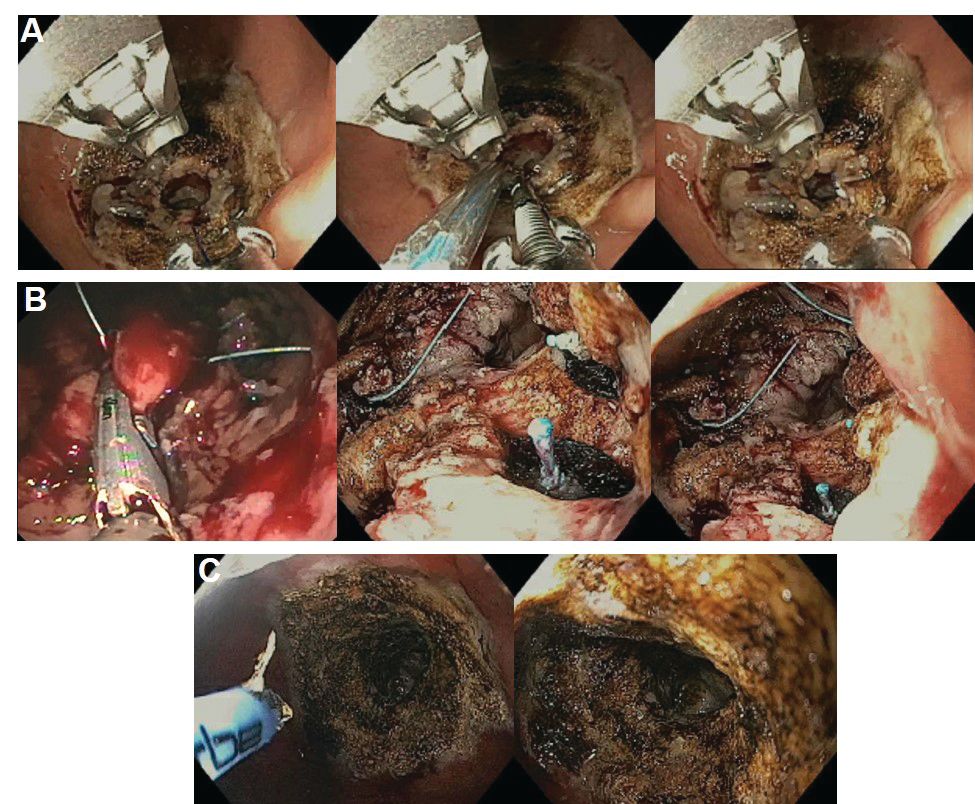

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs) encompass an emerging field for the treatment of obesity. In general, EBMTs are associated with greater weight loss than are lifestyle intervention and pharmacotherapy, but with a less- invasive risk profile than bariatric surgery. EBMTs may be divided into two general categories – gastric and small bowel interventions (Figure 1 and Table 1). Gastric EBMTs are effective at treating obesity, while small bowel EBMTs are effective at treating metabolic diseases with a variable weight loss profile depending on the device.10,11

Of note, a variety of study designs (including retrospective series, prospective series, and randomized trials with and without shams) have been employed, which can affect outcomes. Therefore, weight loss comparisons among studies are challenging and should be considered in this context.

Gastric interventions

Currently, there are three types of EBMTs that are FDA approved and used for the treatment of obesity. These include intragastric balloons (IGBs), plications and suturing, and aspiration therapy (AT). Other technologies that are under investigation also will be briefly covered.

Intragastric balloons

An intragastric balloon is a space-occupying device that is placed in the stomach. The mechanism of action of IGBs involves delaying gastric emptying, which leads to increased satiety.12 There are several types of IGBs available worldwide differing in techniques of placement and removal (endoscopic versus fluoroscopic versus swallowable), materials used to fill the balloon (fluid-filled versus air-filled), and the number of balloons placed (single versus duo versus three-balloon). At the time of this writing, three IGBs are approved by the FDA (Orbera, ReShape, and Obalon), all for patients with body mass indexes of 30-40 kg/m2, and two others are in the process of obtaining FDA approval (Spatz and Elipse).

Orbera gastric balloon (Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, Tex.) is a single fluid-filled IGB that is endoscopically placed and removed at 6 months. The balloon is filled with 400-700 cc of saline with or without methylene blue (to identify leakage or rupture). Recently, Orbera365, which allows the balloon to stay for 12 months instead of 6 months, has become available in Europe; however, it is yet to be approved in the United States. The U.S. pivotal trial (Orbera trial) including 255 subjects (125 Orbera arm versus 130 non-sham control arm) demonstrated 10.2% TWL in the Orbera group compared with 3.3% TWL in the control group at 6 months based on intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. This difference persisted at 12 months (6 months after explantation) with 7.6% TWL for the Orbera group versus 3.1% TWL for the control group.13,14

ReShape integrated dual balloon system (ReShape Lifesciences, San Clemente, Calif.) consists of two connected fluid-filled balloons that are endoscopically placed and removed at 6 months. Each balloon is filled with 375-450 cc of saline mixed with methylene blue. The U.S. pivotal trial (REDUCE trial) including 326 subjects (187 ReShape arm versus 139 sham arm) demonstrated 6.8% TWL in the ReShape group compared with 3.3% TWL in the sham group at 6 months based on ITT analysis.15,16

Obalon balloon system (Obalon Therapeutics, Carlsbad, Calif.) is a swallowable, gas-filled balloon system that requires endoscopy only for removal. During placement, a capsule is swallowed under fluoroscopic guidance. The balloon is then inflated with 250 cc of nitrogen mix gas prior to tube detachment. Up to three balloons may be swallowed sequentially at 1-month intervals. At 6 months from the first balloon placement, all balloons are removed endoscopically. The U.S. pivotal trial (SMART trial) including 366 subjects (185 Obalon arm versus 181 sham capsule arm) demonstrated 6.6% TWL in the Obalon group compared with 3.4% TWL in the sham group at 6 months based on ITT analysis.17,18

Two other balloons that are currently under investigation in the United States are the Spatz3 adjustable balloon system (Spatz Medical, Great Neck, N.Y.) and Elipse balloon (Allurion Technologies, Wellesley, Mass.). The Spatz3 is a fluid-filled balloon that is placed and removed endoscopically. It consists of a single balloon and a connecting tube that allows volume adjustment for control of symptoms and possible augmentation of weight loss. The U.S. pivotal trial was recently completed and the data are being reviewed by the FDA. The Elipse is a swallowable fluid-filled balloon that does not require endoscopy for placement or removal. At 4 months, the balloon releases fluid allowing it to empty and pass naturally. The U.S. pivotal trial (ENLIGHTEN trial) is currently underway.

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials revealed improvement in most metabolic parameters (diastolic blood pressure, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and waist circumference) following IGB compared with controls.19 Nausea and vomiting are seen in approximately 30% and should be addressed appropriately. Pooled serious adverse event (SAE) rate was 1.5%, which included migration, perforation, and death. Since 2016, 14 deaths have been reported according to the FDA MAUDE database. Corporate response was that over 295,000 balloons had been distributed worldwide with a mortality rate of less than 0.01%.20

Plication and suturing

Currently, there are two endoscopic devices that are approved for the general indication of tissue apposition. These include the Incisionless Operating Platform (IOP) (USGI Medical, San Clemente, Calif.) and the Overstitch endoscopic suturing system (Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, Tex.). These devices are used to remodel the stomach to create a sleeve-like structure to induce weight loss.

The IOP system consists of a transport, which is a 54-Fr flexible endoscope. It consists of four working channels that accommodate a G-Prox (for tissue approximation), a G-Lix (for tissue grasping), and an ultrathin endoscope (for visualization). In April 2008, Horgan performed the first-in-human primary obesity surgery endoluminal (POSE) procedure in Argentina. The procedure involves the use of the IOP system to place plications primarily in the fundus to modify gastric accommodation.21 The U.S. pivotal trial (ESSENTIAL trial) including 332 subjects (221 POSE arm versus 111 sham arm) demonstrated 5.0% TWL in the POSE group compared with 1.4% in the sham group at 12 months based on ITT analysis.22 A European multicenter randomized controlled trial (MILEPOST trial) including 44 subjects (34 POSE arm versus 10 non-sham control arm) demonstrated 13.0% TWL in the POSE group compared with 5.3% TWL in the control group at 12 months.23 A recent meta-analysis including five studies with 586 subjects showed pooled weight loss of 13.2% at 12-15 months following POSE with a pooled serious adverse event rate of 3.2%.24 These included extraluminal bleeding, minor bleeding at the suture site, hepatic abscess, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. A distal POSE procedure with a new plication pattern focusing on the gastric body to augment the effect on gastric emptying has also been described.25

The Overstitch is an endoscopic suturing device that is mounted on a double-channel endoscope. At the tip of the scope, there is a curved suture arm and an anchor exchange that allow the needle to pass back and forth to perform full-thickness bites. The tissue helix may also be placed through the second channel to grasp tissue. In April 2012, Thompson performed the first-in-human endoscopic sutured/sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) procedure in India, which was published together with cases performed in Panama and the Dominican Republic.26-28 This procedure involves the use of the Overstitch device to place several sets of running sutures along the greater curvature of the stomach to create a sleeve-like structure. It is thought to delay gastric emptying and therefore increase satiety.29 The largest multicenter retrospective study including 248 patients demonstrated 18.6% TWL at 2 years with 2% SAE rate including perigastric fluid collections, extraluminal hemorrhage, pulmonary embolism, pneumoperitoneum, and pneumothorax.30

Aspiration therapy

Aspiration therapy (AT; Aspire Bariatrics, King of Prussia, Pa.) allows patients to remove 25%-30% of ingested calories at approximately 30 minutes after meals. AT consists of an A-tube, which is a 26-Fr gastrostomy tube with a 15-cm fenestrated drainage catheter placed endoscopically via a standard pull technique. At 1-2 weeks after A-tube placement, the tube is cut down to the skin and connected to the port prior to aspiration. AT is approved for patients with a BMI of 35-55 kg/m2.31 The U.S. pivotal trial (PATHWAY trial) including 207 subjects (137 AT arm versus 70 non-sham control arm) demonstrated 12.1% TWL in the AT group compared to 3.5% in the control group at 12 months based on ITT analysis. The SAE rate was 3.6% including severe abdominal pain, peritonitis, prepyloric ulcer, and A-tube replacement due to skin-port malfunction.32

Transpyloric shuttle

The transpyloric shuttle (TPS; BAROnova, Goleta, Calif.) consists of a spherical bulb that is attached to a smaller cylindrical bulb by a flexible tether. It is placed and removed endoscopically at 6 months. TPS resides across the pylorus creating intermittent obstruction that may result in delayed gastric emptying. A pilot study including 20 patients demonstrated 14.5% TWL at 6 months.33 The U.S. pivotal trial (ENDObesity II trial) was recently completed and the data are being reviewed by the FDA.

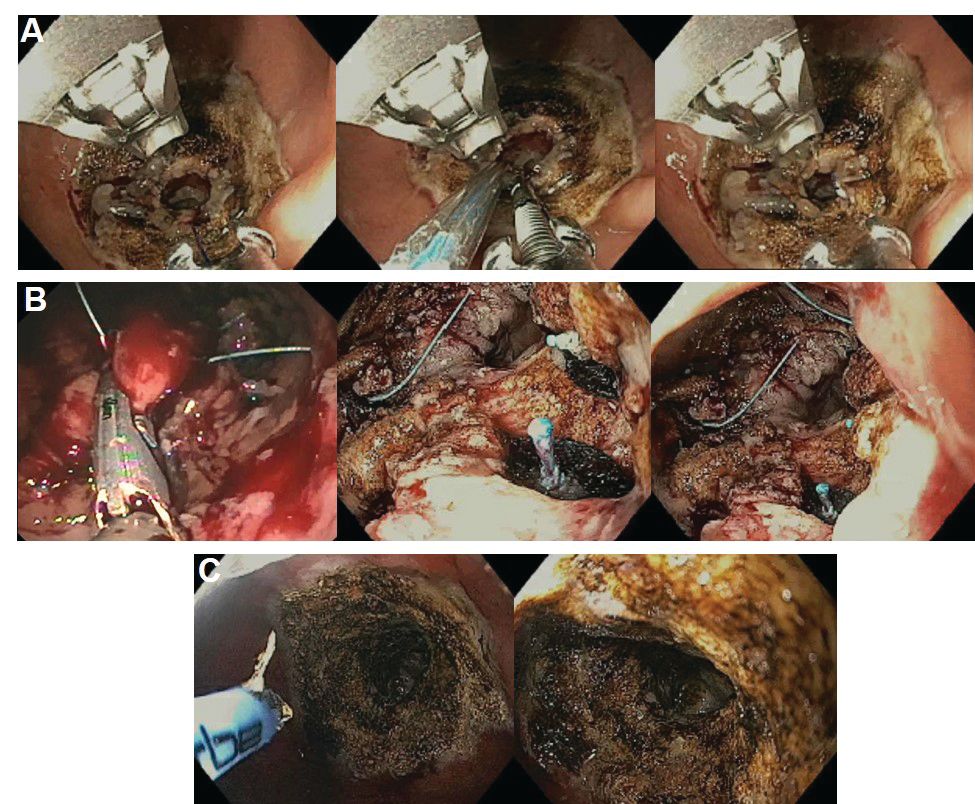

Revision for weight regain following bariatric surgery

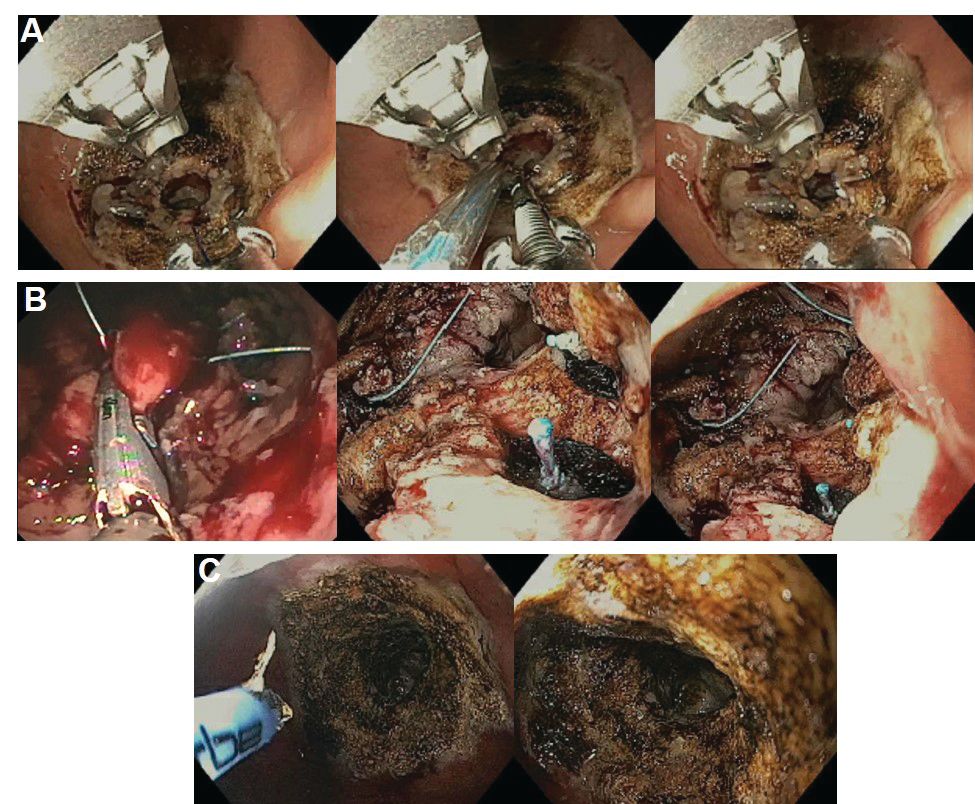

Weight regain is common following RYGB34,35 and can be associated with dilation of the gastrojejunal anastomosis (GJA).36 Several procedures have been developed to treat this condition by focusing on reduction of GJA size and are available in the United States (Figure 2). These procedures have level I evidence supporting their use and include transoral outlet reduction (TORe) and restorative obesity surgery endoluminal (ROSE).37 TORe involves the use of the Overstitch to place sutures at the GJA. At 1 year, patients had 8.4% TWL with improvement in comorbidities.38 Weight loss remained significant up to 3-5 years.39,40 The modern ROSE procedure utilizes the IOP system to place plications at the GJA and distal gastric pouch following argon plasma coagulation (APC). A small series showed 12.4% TWL at 6 months.41 APC is also currently being investigated as a standalone therapy for weight regain in this population.

Small bowel interventions

There are several small bowel interventions, with different mechanisms of action, available internationally. Many of these are under investigation in the United States; however, none are currently FDA approved.

Duodenal-jejunal bypass liner

Duodenal-jejunal bypass liner (DJBL; GI Dynamics, Boston, Mass.) is a 60-cm fluoropolymer liner that is endoscopically placed and removed at 12 months. It is anchored at the duodenal bulb and ends at the jejunum. By excluding direct contact between chyme and the proximal small bowel, DJBL is thought to work via foregut mechanism where there is less inhibition of the incretin effect (greater increase in insulin secretion following oral glucose administration compared to intravenous glucose administration due to gut-derived factors that enhance insulin secretion) leading to improved insulin resistance. In addition, the enteral transit of chyme and bile is altered suggesting the possible role of the hindgut mechanism. The previous U.S. pivotal trial (ENDO trial) met efficacy endpoints. However, the study was stopped early by the company because of a hepatic abscess rate of 3.5%, all of which were treated conservatively.42 A new U.S. pivotal study is currently planned. A meta-analysis of 17 published studies, all of which were from outside the United States, demonstrated a significant decrease in hemoglobin A1c of 1.3% and 18.9% TWL at 1 year following implantation in patients with obesity with concomitant diabetes.43

Duodenal mucosal resurfacing

Duodenal mucosal resurfacing (Fractyl, Lexington, Mass.) involves saline lifting of the duodenal mucosa circumferentially prior to thermal ablation using an inflated balloon filled with heated water. It is hypothesized that this may reset the diseased duodenal enteroendocrine cells leading to restoration of the incretin effect. A pilot study including 39 patients with poorly controlled diabetes demonstrated a decrease in hemoglobin A1c of 1.2%. The SAE rate was 7.7% including duodenal stenosis, all of which were treated with balloon dilation.44 The U.S. pivotal trial is currently planned.

Gastroduodenal-jejunal bypass

Gastroduodenal-jejunal bypass (ValenTx., Hopkins, Minn.) is a 120-cm sleeve that is anchored at the gastroesophageal junction to create the anatomic changes of RYGB. It is placed and removed endoscopically with laparoscopic assistance. A pilot study including 12 patients demonstrated 35.9% excess weight loss at 12 months. Two out of 12 patients had early device removal due to intolerance and they were not included in the weight loss analysis.45

Incisionless magnetic anastomosis system

The incisionless magnetic anastomosis system (GI Windows, West Bridgewater, Mass.) consists of self-assembling magnets that are deployed under fluoroscopic guidance through the working channel of colonoscopes to form magnetic octagons in the jejunum and ileum. After a week, a compression anastomosis is formed and the coupled magnets pass spontaneously. A pilot study including 10 patients showed 14.6% TWL and a decrease in hemoglobin A1c of 1.9% (for patients with diabetes) at 1 year.46 A randomized study outside the United States is currently underway.

Summary

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies are emerging as first-line treatments for obesity in many populations. They can serve as a gap therapy for patients who do not qualify for surgery, but also may have a specific role in the treatment of metabolic comorbidities. This field will continue to develop and improve with the introduction of personalized medicine leading to better patient selection, and newer combination therapies. It is time for gastroenterologists to become more involved in the management of this challenging condition.

Dr. Jirapinyo is an advanced and bariatric endoscopy fellow, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston; Dr. Thompson is director of therapeutic endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and associate professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School. Dr. Jirapinyo has served as a consultant for GI Dynamics and holds royalties for Endosim. Dr. Thompson has contracted research for Aspire Bariatrics, USGI Medical, Spatz, and Apollo Endosurgery; has served as a consultant for Boston Scientific, Covidien, USGI Medical, Olympus, and Fractyl; holds stocks and royalties for GI Windows and Endosim, and has served as an expert reviewer for GI Dynamics.

References

1. CDC. From https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html. Accessed on 11 September 2018.

2. Aronne LJ et al. Obesity. 2013;21:2163-71.

3. Torgerson JS et al. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:155-61.

4. Allison DB et al. Obesity. 2012;20:330-42.

5. Smith SR et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:245-56.

6. Apovian CM et al. Obesity. 2013;21:935-43.

7. Pi-Sunyer X et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:11-22.

8. Colguitt JL et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;8(8):CD003641.

9. Ponce J et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(6):1199-200.

10. Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(5):619-30.

11. Sullivan S et al.Gastroenterology. 2017;152(7):1791-801.

12. Gomez V et al. Obesity. 2016;24(9):1849-53.

13. Food and Drug Administration. Summary of safety and effectiveness data (SSED) ORBERA Intragastric Balloon System. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf14/P140008b.pdf. 2015:1-32.

14. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:AB147.

15. Food and Drug Administration. Summary of safety and effectiveness data (SSED) ReShape Integrated Dual Balloon System. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf14/P140012b.pdf. 2015:1-43.

16. Ponce J et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:874-81.

17. Food and Drug Administration. Summary and effectiveness data (SSED): Obalon Balloon System. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf16/P160001b.pdf. 2016:1-46.

18. Sullivan S et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:S1267.

19. Popov VB et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:429-39.

20. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(3):425-38.

21. Espinos JC et al. Obes Surg. 2013;23(9):1375-83.

22. Sullivan S et al. Obesity. 2017;25:294-301.

23. Miller K et al. Obesity Surg. 2017;27(2):310-22.

24. Jirapinyo P et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87(6):AB604-AB605.

25. Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC. Video GIE. 2018;3(10):296-300.

26. Campos J et al. SAGES 2013 Presentation. Baltimore, MD. 19 April 2013.

27. Kumar N et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):S571-2.

28. Kumar N et al. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(4):2159-64.

29. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:37-43.

30. Lopez-Nava G et al. Obes Surg. 2017;27(10):2649-55.

31. Food and Drug Administration. Summary of safety and effectiveness (SSED): AspireAssist. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf15/p150024b.pdf. FDA,ed,2016:1-36.

32. Thompson CC et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:447-57.

33. SAGES abstract archives. SAGES. Available from: http://www.sages.org/meetings/annual-meeting/abstracts-archive/first-clinical-experience-with-the-transpyloric-shuttle-tpsr-device-a-non-surgical-endoscopic treatment-for-obesity-results-from-a-3-month-and-6-month-study. Accessed Sept. 12, 2018.

34. Sjostrom L et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741-52.

35. Adams TD et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1143-55.

36. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:228-33.

37. Thompson CC et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):129-37.

38. Jirapinyo P et al. Endoscopy. 2018;50(4):371-7.

39. Kumar N, Thompson CC. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(4):776-9.

40. Jirapinyo P et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(5):AB93-94.

41. Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC et al. Comparison of a novel plication technique to suturing for endoscopic outlet reduction for the treatment of weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obesity Week 2018. Poster presentation.

42. Kaplan LM et al. EndoBarrier therapy is associated with glycemic improvement, weight loss and safety issues in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes on oral anti-hyperglycemic agents (The ENDO Trial). In: Oral Presentation at the 76th American Diabetes Association (ADA) Annual Meeting: 2016 June 10-14: New Orleans. Abstract number 362-LB.

43. Jirapinyo P et al. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):1106-15.

44. Rajagopalan H et al. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(12):2254-61.

45. Sandler BJ et al. Surgical Endosc. 2015;29:3298-303.

46. Machytka E et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86(5):904-12.

Editor's Note

Gastroenterologists are becoming increasingly involved in the management of obesity. While prior therapy for obesity was mainly based on lifestyle changes, medication, or surgery, the new and exciting field of endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies has recently garnered incredible attention and momentum.

In this quarter’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, Pichamol Jirapinyo and Christopher Thompson (Brigham and Women’s Hospital) provide an outstanding overview of the gastric and small bowel endoscopic interventions that are either already approved for use in obesity or currently being studied. This field is moving incredibly fast, and knowledge and understanding of these endoscopic therapies for obesity will undoubtedly be important for our field.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Introduction

Obesity is a rising pandemic. As of 2016, 93.3 million U.S. adults had obesity, representing 39.8% of our adult population.1 It is estimated that approximately $147 billion is spent annually on caring for patients with obesity. Traditionally, the management of obesity includes lifestyle therapy (diet and exercise), pharmacotherapy (six Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for obesity), and bariatric surgery (sleeve gastrectomy [SG] and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass [RYGB]). Nevertheless, intensive lifestyle intervention and pharmacotherapy are associated with approximately 3.1%-6.6% total weight loss (TWL),2-7 and bariatric surgery is associated with 20%-33.3% TWL.8 However, less than 2% of patients who are eligible for bariatric surgery elect to undergo surgery, leaving a large proportion of patients with obesity untreated or undertreated.9

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs) encompass an emerging field for the treatment of obesity. In general, EBMTs are associated with greater weight loss than are lifestyle intervention and pharmacotherapy, but with a less- invasive risk profile than bariatric surgery. EBMTs may be divided into two general categories – gastric and small bowel interventions (Figure 1 and Table 1). Gastric EBMTs are effective at treating obesity, while small bowel EBMTs are effective at treating metabolic diseases with a variable weight loss profile depending on the device.10,11

Of note, a variety of study designs (including retrospective series, prospective series, and randomized trials with and without shams) have been employed, which can affect outcomes. Therefore, weight loss comparisons among studies are challenging and should be considered in this context.

Gastric interventions

Currently, there are three types of EBMTs that are FDA approved and used for the treatment of obesity. These include intragastric balloons (IGBs), plications and suturing, and aspiration therapy (AT). Other technologies that are under investigation also will be briefly covered.

Intragastric balloons

An intragastric balloon is a space-occupying device that is placed in the stomach. The mechanism of action of IGBs involves delaying gastric emptying, which leads to increased satiety.12 There are several types of IGBs available worldwide differing in techniques of placement and removal (endoscopic versus fluoroscopic versus swallowable), materials used to fill the balloon (fluid-filled versus air-filled), and the number of balloons placed (single versus duo versus three-balloon). At the time of this writing, three IGBs are approved by the FDA (Orbera, ReShape, and Obalon), all for patients with body mass indexes of 30-40 kg/m2, and two others are in the process of obtaining FDA approval (Spatz and Elipse).

Orbera gastric balloon (Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, Tex.) is a single fluid-filled IGB that is endoscopically placed and removed at 6 months. The balloon is filled with 400-700 cc of saline with or without methylene blue (to identify leakage or rupture). Recently, Orbera365, which allows the balloon to stay for 12 months instead of 6 months, has become available in Europe; however, it is yet to be approved in the United States. The U.S. pivotal trial (Orbera trial) including 255 subjects (125 Orbera arm versus 130 non-sham control arm) demonstrated 10.2% TWL in the Orbera group compared with 3.3% TWL in the control group at 6 months based on intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. This difference persisted at 12 months (6 months after explantation) with 7.6% TWL for the Orbera group versus 3.1% TWL for the control group.13,14

ReShape integrated dual balloon system (ReShape Lifesciences, San Clemente, Calif.) consists of two connected fluid-filled balloons that are endoscopically placed and removed at 6 months. Each balloon is filled with 375-450 cc of saline mixed with methylene blue. The U.S. pivotal trial (REDUCE trial) including 326 subjects (187 ReShape arm versus 139 sham arm) demonstrated 6.8% TWL in the ReShape group compared with 3.3% TWL in the sham group at 6 months based on ITT analysis.15,16

Obalon balloon system (Obalon Therapeutics, Carlsbad, Calif.) is a swallowable, gas-filled balloon system that requires endoscopy only for removal. During placement, a capsule is swallowed under fluoroscopic guidance. The balloon is then inflated with 250 cc of nitrogen mix gas prior to tube detachment. Up to three balloons may be swallowed sequentially at 1-month intervals. At 6 months from the first balloon placement, all balloons are removed endoscopically. The U.S. pivotal trial (SMART trial) including 366 subjects (185 Obalon arm versus 181 sham capsule arm) demonstrated 6.6% TWL in the Obalon group compared with 3.4% TWL in the sham group at 6 months based on ITT analysis.17,18

Two other balloons that are currently under investigation in the United States are the Spatz3 adjustable balloon system (Spatz Medical, Great Neck, N.Y.) and Elipse balloon (Allurion Technologies, Wellesley, Mass.). The Spatz3 is a fluid-filled balloon that is placed and removed endoscopically. It consists of a single balloon and a connecting tube that allows volume adjustment for control of symptoms and possible augmentation of weight loss. The U.S. pivotal trial was recently completed and the data are being reviewed by the FDA. The Elipse is a swallowable fluid-filled balloon that does not require endoscopy for placement or removal. At 4 months, the balloon releases fluid allowing it to empty and pass naturally. The U.S. pivotal trial (ENLIGHTEN trial) is currently underway.

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials revealed improvement in most metabolic parameters (diastolic blood pressure, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and waist circumference) following IGB compared with controls.19 Nausea and vomiting are seen in approximately 30% and should be addressed appropriately. Pooled serious adverse event (SAE) rate was 1.5%, which included migration, perforation, and death. Since 2016, 14 deaths have been reported according to the FDA MAUDE database. Corporate response was that over 295,000 balloons had been distributed worldwide with a mortality rate of less than 0.01%.20

Plication and suturing

Currently, there are two endoscopic devices that are approved for the general indication of tissue apposition. These include the Incisionless Operating Platform (IOP) (USGI Medical, San Clemente, Calif.) and the Overstitch endoscopic suturing system (Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, Tex.). These devices are used to remodel the stomach to create a sleeve-like structure to induce weight loss.

The IOP system consists of a transport, which is a 54-Fr flexible endoscope. It consists of four working channels that accommodate a G-Prox (for tissue approximation), a G-Lix (for tissue grasping), and an ultrathin endoscope (for visualization). In April 2008, Horgan performed the first-in-human primary obesity surgery endoluminal (POSE) procedure in Argentina. The procedure involves the use of the IOP system to place plications primarily in the fundus to modify gastric accommodation.21 The U.S. pivotal trial (ESSENTIAL trial) including 332 subjects (221 POSE arm versus 111 sham arm) demonstrated 5.0% TWL in the POSE group compared with 1.4% in the sham group at 12 months based on ITT analysis.22 A European multicenter randomized controlled trial (MILEPOST trial) including 44 subjects (34 POSE arm versus 10 non-sham control arm) demonstrated 13.0% TWL in the POSE group compared with 5.3% TWL in the control group at 12 months.23 A recent meta-analysis including five studies with 586 subjects showed pooled weight loss of 13.2% at 12-15 months following POSE with a pooled serious adverse event rate of 3.2%.24 These included extraluminal bleeding, minor bleeding at the suture site, hepatic abscess, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. A distal POSE procedure with a new plication pattern focusing on the gastric body to augment the effect on gastric emptying has also been described.25

The Overstitch is an endoscopic suturing device that is mounted on a double-channel endoscope. At the tip of the scope, there is a curved suture arm and an anchor exchange that allow the needle to pass back and forth to perform full-thickness bites. The tissue helix may also be placed through the second channel to grasp tissue. In April 2012, Thompson performed the first-in-human endoscopic sutured/sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) procedure in India, which was published together with cases performed in Panama and the Dominican Republic.26-28 This procedure involves the use of the Overstitch device to place several sets of running sutures along the greater curvature of the stomach to create a sleeve-like structure. It is thought to delay gastric emptying and therefore increase satiety.29 The largest multicenter retrospective study including 248 patients demonstrated 18.6% TWL at 2 years with 2% SAE rate including perigastric fluid collections, extraluminal hemorrhage, pulmonary embolism, pneumoperitoneum, and pneumothorax.30

Aspiration therapy

Aspiration therapy (AT; Aspire Bariatrics, King of Prussia, Pa.) allows patients to remove 25%-30% of ingested calories at approximately 30 minutes after meals. AT consists of an A-tube, which is a 26-Fr gastrostomy tube with a 15-cm fenestrated drainage catheter placed endoscopically via a standard pull technique. At 1-2 weeks after A-tube placement, the tube is cut down to the skin and connected to the port prior to aspiration. AT is approved for patients with a BMI of 35-55 kg/m2.31 The U.S. pivotal trial (PATHWAY trial) including 207 subjects (137 AT arm versus 70 non-sham control arm) demonstrated 12.1% TWL in the AT group compared to 3.5% in the control group at 12 months based on ITT analysis. The SAE rate was 3.6% including severe abdominal pain, peritonitis, prepyloric ulcer, and A-tube replacement due to skin-port malfunction.32

Transpyloric shuttle

The transpyloric shuttle (TPS; BAROnova, Goleta, Calif.) consists of a spherical bulb that is attached to a smaller cylindrical bulb by a flexible tether. It is placed and removed endoscopically at 6 months. TPS resides across the pylorus creating intermittent obstruction that may result in delayed gastric emptying. A pilot study including 20 patients demonstrated 14.5% TWL at 6 months.33 The U.S. pivotal trial (ENDObesity II trial) was recently completed and the data are being reviewed by the FDA.

Revision for weight regain following bariatric surgery

Weight regain is common following RYGB34,35 and can be associated with dilation of the gastrojejunal anastomosis (GJA).36 Several procedures have been developed to treat this condition by focusing on reduction of GJA size and are available in the United States (Figure 2). These procedures have level I evidence supporting their use and include transoral outlet reduction (TORe) and restorative obesity surgery endoluminal (ROSE).37 TORe involves the use of the Overstitch to place sutures at the GJA. At 1 year, patients had 8.4% TWL with improvement in comorbidities.38 Weight loss remained significant up to 3-5 years.39,40 The modern ROSE procedure utilizes the IOP system to place plications at the GJA and distal gastric pouch following argon plasma coagulation (APC). A small series showed 12.4% TWL at 6 months.41 APC is also currently being investigated as a standalone therapy for weight regain in this population.

Small bowel interventions

There are several small bowel interventions, with different mechanisms of action, available internationally. Many of these are under investigation in the United States; however, none are currently FDA approved.

Duodenal-jejunal bypass liner

Duodenal-jejunal bypass liner (DJBL; GI Dynamics, Boston, Mass.) is a 60-cm fluoropolymer liner that is endoscopically placed and removed at 12 months. It is anchored at the duodenal bulb and ends at the jejunum. By excluding direct contact between chyme and the proximal small bowel, DJBL is thought to work via foregut mechanism where there is less inhibition of the incretin effect (greater increase in insulin secretion following oral glucose administration compared to intravenous glucose administration due to gut-derived factors that enhance insulin secretion) leading to improved insulin resistance. In addition, the enteral transit of chyme and bile is altered suggesting the possible role of the hindgut mechanism. The previous U.S. pivotal trial (ENDO trial) met efficacy endpoints. However, the study was stopped early by the company because of a hepatic abscess rate of 3.5%, all of which were treated conservatively.42 A new U.S. pivotal study is currently planned. A meta-analysis of 17 published studies, all of which were from outside the United States, demonstrated a significant decrease in hemoglobin A1c of 1.3% and 18.9% TWL at 1 year following implantation in patients with obesity with concomitant diabetes.43

Duodenal mucosal resurfacing

Duodenal mucosal resurfacing (Fractyl, Lexington, Mass.) involves saline lifting of the duodenal mucosa circumferentially prior to thermal ablation using an inflated balloon filled with heated water. It is hypothesized that this may reset the diseased duodenal enteroendocrine cells leading to restoration of the incretin effect. A pilot study including 39 patients with poorly controlled diabetes demonstrated a decrease in hemoglobin A1c of 1.2%. The SAE rate was 7.7% including duodenal stenosis, all of which were treated with balloon dilation.44 The U.S. pivotal trial is currently planned.

Gastroduodenal-jejunal bypass

Gastroduodenal-jejunal bypass (ValenTx., Hopkins, Minn.) is a 120-cm sleeve that is anchored at the gastroesophageal junction to create the anatomic changes of RYGB. It is placed and removed endoscopically with laparoscopic assistance. A pilot study including 12 patients demonstrated 35.9% excess weight loss at 12 months. Two out of 12 patients had early device removal due to intolerance and they were not included in the weight loss analysis.45

Incisionless magnetic anastomosis system

The incisionless magnetic anastomosis system (GI Windows, West Bridgewater, Mass.) consists of self-assembling magnets that are deployed under fluoroscopic guidance through the working channel of colonoscopes to form magnetic octagons in the jejunum and ileum. After a week, a compression anastomosis is formed and the coupled magnets pass spontaneously. A pilot study including 10 patients showed 14.6% TWL and a decrease in hemoglobin A1c of 1.9% (for patients with diabetes) at 1 year.46 A randomized study outside the United States is currently underway.

Summary

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies are emerging as first-line treatments for obesity in many populations. They can serve as a gap therapy for patients who do not qualify for surgery, but also may have a specific role in the treatment of metabolic comorbidities. This field will continue to develop and improve with the introduction of personalized medicine leading to better patient selection, and newer combination therapies. It is time for gastroenterologists to become more involved in the management of this challenging condition.

Dr. Jirapinyo is an advanced and bariatric endoscopy fellow, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston; Dr. Thompson is director of therapeutic endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and associate professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School. Dr. Jirapinyo has served as a consultant for GI Dynamics and holds royalties for Endosim. Dr. Thompson has contracted research for Aspire Bariatrics, USGI Medical, Spatz, and Apollo Endosurgery; has served as a consultant for Boston Scientific, Covidien, USGI Medical, Olympus, and Fractyl; holds stocks and royalties for GI Windows and Endosim, and has served as an expert reviewer for GI Dynamics.

References

1. CDC. From https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html. Accessed on 11 September 2018.

2. Aronne LJ et al. Obesity. 2013;21:2163-71.

3. Torgerson JS et al. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:155-61.

4. Allison DB et al. Obesity. 2012;20:330-42.

5. Smith SR et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:245-56.

6. Apovian CM et al. Obesity. 2013;21:935-43.

7. Pi-Sunyer X et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:11-22.

8. Colguitt JL et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;8(8):CD003641.

9. Ponce J et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(6):1199-200.

10. Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(5):619-30.

11. Sullivan S et al.Gastroenterology. 2017;152(7):1791-801.

12. Gomez V et al. Obesity. 2016;24(9):1849-53.

13. Food and Drug Administration. Summary of safety and effectiveness data (SSED) ORBERA Intragastric Balloon System. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf14/P140008b.pdf. 2015:1-32.

14. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:AB147.

15. Food and Drug Administration. Summary of safety and effectiveness data (SSED) ReShape Integrated Dual Balloon System. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf14/P140012b.pdf. 2015:1-43.

16. Ponce J et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:874-81.

17. Food and Drug Administration. Summary and effectiveness data (SSED): Obalon Balloon System. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf16/P160001b.pdf. 2016:1-46.

18. Sullivan S et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:S1267.

19. Popov VB et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:429-39.

20. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(3):425-38.

21. Espinos JC et al. Obes Surg. 2013;23(9):1375-83.

22. Sullivan S et al. Obesity. 2017;25:294-301.

23. Miller K et al. Obesity Surg. 2017;27(2):310-22.

24. Jirapinyo P et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87(6):AB604-AB605.

25. Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC. Video GIE. 2018;3(10):296-300.

26. Campos J et al. SAGES 2013 Presentation. Baltimore, MD. 19 April 2013.

27. Kumar N et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):S571-2.

28. Kumar N et al. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(4):2159-64.

29. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:37-43.

30. Lopez-Nava G et al. Obes Surg. 2017;27(10):2649-55.

31. Food and Drug Administration. Summary of safety and effectiveness (SSED): AspireAssist. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf15/p150024b.pdf. FDA,ed,2016:1-36.

32. Thompson CC et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:447-57.

33. SAGES abstract archives. SAGES. Available from: http://www.sages.org/meetings/annual-meeting/abstracts-archive/first-clinical-experience-with-the-transpyloric-shuttle-tpsr-device-a-non-surgical-endoscopic treatment-for-obesity-results-from-a-3-month-and-6-month-study. Accessed Sept. 12, 2018.

34. Sjostrom L et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741-52.

35. Adams TD et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1143-55.

36. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:228-33.

37. Thompson CC et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):129-37.

38. Jirapinyo P et al. Endoscopy. 2018;50(4):371-7.

39. Kumar N, Thompson CC. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(4):776-9.

40. Jirapinyo P et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(5):AB93-94.

41. Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC et al. Comparison of a novel plication technique to suturing for endoscopic outlet reduction for the treatment of weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obesity Week 2018. Poster presentation.

42. Kaplan LM et al. EndoBarrier therapy is associated with glycemic improvement, weight loss and safety issues in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes on oral anti-hyperglycemic agents (The ENDO Trial). In: Oral Presentation at the 76th American Diabetes Association (ADA) Annual Meeting: 2016 June 10-14: New Orleans. Abstract number 362-LB.

43. Jirapinyo P et al. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):1106-15.

44. Rajagopalan H et al. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(12):2254-61.