User login

Subjected to sexually inappropriate behavior? Set LIMITS

Everyone needs love, companionship, and intimacy. Unfortunately, mental illness often results in interpersonal dysfunction, thereby frustrating these desires. Patients might exhibit sexually inappropriate behavior (SIB), consisting of comments, requests, or actions. The causes of SIB include confusion, predation, loneliness, psychosis, social impairment, character pathology, and/or mania.

Such attention poses an issue for mental health providers; trainees could be particularly vulnerable. The impact can be disheartening and cause practitioners to withdraw from patients or question their work, which could be detrimental to both providers and patients. While maintaining their personal safety, it is important that clinicians approach patients with compassion. To help clinicians manage SIB, we propose setting LIMITS.

Look after personal safety. Clinicians are trained to care for all patients, but situations can arise where it is no longer safe to work with an individual. A clinician who feels threatened is less likely to help the patient, especially if real danger is posed. Such situations could necessitate transferring the patient’s care to another provider. Clinicians also can choose to interact with a patient exhibiting SIB while colleagues are present.

Identify the etiology. SIB arises from a variety of underlying states, and the clinician’s response can vary depending on the cause. Questions to consider before reacting include:

- What is the origin of the behavior?

- What form is the behavior taking?

- In what context is it occurring?

- How frequent is it occurring?

- What factors are contributing?

- What are the risks to all parties?1

Maintain a professional role. Although SIB can undermine the provider–patient relationship, the behavior could be unintended. To remain professional, practitioners should pause before reacting and consider how to respond. A particular concern is countertransference, meaning that the provider might react to a patient’s behavior based on personal bias. This could result in amorous, hateful, or angry responses from the provider, which could put the treatment relationship at risk, harm the patient, or result in medical–legal repercussions.

Implement appropriate boundaries. In man

Talk with a Supervisor. These scenarios often produce many emotions. Residents could be experiencing them for the first time, but even seasoned clinicians can find them challenging. When in doubt, seek guidance from colleagues, supervisors, or mentors to help you clarify the situation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristina Zdanys, MD, David Schmidt, DO, Joanna Chaurette, MD, PhD, and Shilpa Lad, MD, for their input.

1. Series H, Dégano P. Hypersexuality in dementia. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2005; 11(6):424-431.

Everyone needs love, companionship, and intimacy. Unfortunately, mental illness often results in interpersonal dysfunction, thereby frustrating these desires. Patients might exhibit sexually inappropriate behavior (SIB), consisting of comments, requests, or actions. The causes of SIB include confusion, predation, loneliness, psychosis, social impairment, character pathology, and/or mania.

Such attention poses an issue for mental health providers; trainees could be particularly vulnerable. The impact can be disheartening and cause practitioners to withdraw from patients or question their work, which could be detrimental to both providers and patients. While maintaining their personal safety, it is important that clinicians approach patients with compassion. To help clinicians manage SIB, we propose setting LIMITS.

Look after personal safety. Clinicians are trained to care for all patients, but situations can arise where it is no longer safe to work with an individual. A clinician who feels threatened is less likely to help the patient, especially if real danger is posed. Such situations could necessitate transferring the patient’s care to another provider. Clinicians also can choose to interact with a patient exhibiting SIB while colleagues are present.

Identify the etiology. SIB arises from a variety of underlying states, and the clinician’s response can vary depending on the cause. Questions to consider before reacting include:

- What is the origin of the behavior?

- What form is the behavior taking?

- In what context is it occurring?

- How frequent is it occurring?

- What factors are contributing?

- What are the risks to all parties?1

Maintain a professional role. Although SIB can undermine the provider–patient relationship, the behavior could be unintended. To remain professional, practitioners should pause before reacting and consider how to respond. A particular concern is countertransference, meaning that the provider might react to a patient’s behavior based on personal bias. This could result in amorous, hateful, or angry responses from the provider, which could put the treatment relationship at risk, harm the patient, or result in medical–legal repercussions.

Implement appropriate boundaries. In man

Talk with a Supervisor. These scenarios often produce many emotions. Residents could be experiencing them for the first time, but even seasoned clinicians can find them challenging. When in doubt, seek guidance from colleagues, supervisors, or mentors to help you clarify the situation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristina Zdanys, MD, David Schmidt, DO, Joanna Chaurette, MD, PhD, and Shilpa Lad, MD, for their input.

Everyone needs love, companionship, and intimacy. Unfortunately, mental illness often results in interpersonal dysfunction, thereby frustrating these desires. Patients might exhibit sexually inappropriate behavior (SIB), consisting of comments, requests, or actions. The causes of SIB include confusion, predation, loneliness, psychosis, social impairment, character pathology, and/or mania.

Such attention poses an issue for mental health providers; trainees could be particularly vulnerable. The impact can be disheartening and cause practitioners to withdraw from patients or question their work, which could be detrimental to both providers and patients. While maintaining their personal safety, it is important that clinicians approach patients with compassion. To help clinicians manage SIB, we propose setting LIMITS.

Look after personal safety. Clinicians are trained to care for all patients, but situations can arise where it is no longer safe to work with an individual. A clinician who feels threatened is less likely to help the patient, especially if real danger is posed. Such situations could necessitate transferring the patient’s care to another provider. Clinicians also can choose to interact with a patient exhibiting SIB while colleagues are present.

Identify the etiology. SIB arises from a variety of underlying states, and the clinician’s response can vary depending on the cause. Questions to consider before reacting include:

- What is the origin of the behavior?

- What form is the behavior taking?

- In what context is it occurring?

- How frequent is it occurring?

- What factors are contributing?

- What are the risks to all parties?1

Maintain a professional role. Although SIB can undermine the provider–patient relationship, the behavior could be unintended. To remain professional, practitioners should pause before reacting and consider how to respond. A particular concern is countertransference, meaning that the provider might react to a patient’s behavior based on personal bias. This could result in amorous, hateful, or angry responses from the provider, which could put the treatment relationship at risk, harm the patient, or result in medical–legal repercussions.

Implement appropriate boundaries. In man

Talk with a Supervisor. These scenarios often produce many emotions. Residents could be experiencing them for the first time, but even seasoned clinicians can find them challenging. When in doubt, seek guidance from colleagues, supervisors, or mentors to help you clarify the situation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristina Zdanys, MD, David Schmidt, DO, Joanna Chaurette, MD, PhD, and Shilpa Lad, MD, for their input.

1. Series H, Dégano P. Hypersexuality in dementia. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2005; 11(6):424-431.

1. Series H, Dégano P. Hypersexuality in dementia. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2005; 11(6):424-431.

Benefits and costs of accepting credit cards in your practice

Are you tired of waiting for checks in the mail? Do patients leave without paying their balance? Streamlining revenue collection by taking credit cards is a tantalizing antidote to these ills, but it has downsides. Weighing the value for you and your patients is necessary before you decide on this important practice management policy.

Clinical and practical advantages

Many patients prefer that their health care practitioners take credit cards, because it simplifies their busy lives—and who carries a checkbook anymore? Patients can put the whole session to good use without sacrificing time taking care of payment. They also can receive credit card rewards for their payment, or use health savings accounts, health reimbursement accounts, or flexible spending debit cards, making treatment more affordable.

Benefits of credit cards

Accepting credit cards has many benefits:

- Allows more time in a session to focus on clinical matters because you do not have to allocate time to collect payment, which might include dealing with a forgotten checkbook or a request for a change in your payment policies.

- Easier to collect payment for no-shows. This could result in a reduced no-show rate, because a patient might feel more accountable to show up knowing that his (her) credit card is on file.

- Saves time recording and depositing checks.

- Avoids bounced checks and collection agencies.

Money doesn’t grow on trees

Although there are advantages to accepting credit cards, several costs should be considered. Some practitioners feel that accepting credit cards makes their practice seem like a commercial business. There also is an expense of accepting credit cards, and understanding these costs can be confusing because there are different processing systems of rates. Whether the rate is flat, tiered, or wholesale, you always will pay a percentage of the transaction, plus a transaction fee.

Here are some general guidelines on rates:

- Debit cards are the least expensive to process but often have low spending limits.

- Rewards cards, such as frequent flyer cards, are the most expensive to process. Have you ever wondered who foots the bill for those frequent flyer miles? It’s not the airline; it’s the merchant (you).

- For tiered rates, swiping cards is typically cheaper than typing in the credit card info. Tiered rates often have low rates, known as “teaser” rates, because they are applicable in far fewer cases.

- For flat or wholesale rates, securely saving credit card numbers is not any more expensive than swiping a card, and saves time in the long run and potential awkwardness at the end of a session.

- A higher volume of processed credit cards might allow you to negotiate your rates.

- Check if your bank offers a less expensive option. Some banks offer preferred rates for their customers.

Also consider the time and possible expense of ensuring that you are Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard compliant (information security standards that aim to keep cardholder data secure).

Different methods of processing transactions have varying levels of requirements:

- A swiping reader with a terminal connected to a telephone line is more secure than through the Internet and carries fewer compliance burdens. Use a reader that can handle chip-cards, because you could be liable for fraudulent transactions.

- Do not save or store credit card numbers you typed yourself. Compliance is less burdensome if patients input credit card data into a secure portal.

- Store credit card data securely via your credit card processing partner, although the partner is still at risk of a data breach. Practitioners should weigh the value of convenience vs security.

- If there is a data breach and you are found negligent you could be fined $5,000 to $100,000 per month, depending on whether you are a large company or solo practice.

Bottom dollar

Credit card processing has significant advantages from both a practice management and clinical standpoint. Because prices for services vary, shop around to find the best rates and educate yourself about security requirements. Taking the time to research these matters can pay off in the long term.

Are you tired of waiting for checks in the mail? Do patients leave without paying their balance? Streamlining revenue collection by taking credit cards is a tantalizing antidote to these ills, but it has downsides. Weighing the value for you and your patients is necessary before you decide on this important practice management policy.

Clinical and practical advantages

Many patients prefer that their health care practitioners take credit cards, because it simplifies their busy lives—and who carries a checkbook anymore? Patients can put the whole session to good use without sacrificing time taking care of payment. They also can receive credit card rewards for their payment, or use health savings accounts, health reimbursement accounts, or flexible spending debit cards, making treatment more affordable.

Benefits of credit cards

Accepting credit cards has many benefits:

- Allows more time in a session to focus on clinical matters because you do not have to allocate time to collect payment, which might include dealing with a forgotten checkbook or a request for a change in your payment policies.

- Easier to collect payment for no-shows. This could result in a reduced no-show rate, because a patient might feel more accountable to show up knowing that his (her) credit card is on file.

- Saves time recording and depositing checks.

- Avoids bounced checks and collection agencies.

Money doesn’t grow on trees

Although there are advantages to accepting credit cards, several costs should be considered. Some practitioners feel that accepting credit cards makes their practice seem like a commercial business. There also is an expense of accepting credit cards, and understanding these costs can be confusing because there are different processing systems of rates. Whether the rate is flat, tiered, or wholesale, you always will pay a percentage of the transaction, plus a transaction fee.

Here are some general guidelines on rates:

- Debit cards are the least expensive to process but often have low spending limits.

- Rewards cards, such as frequent flyer cards, are the most expensive to process. Have you ever wondered who foots the bill for those frequent flyer miles? It’s not the airline; it’s the merchant (you).

- For tiered rates, swiping cards is typically cheaper than typing in the credit card info. Tiered rates often have low rates, known as “teaser” rates, because they are applicable in far fewer cases.

- For flat or wholesale rates, securely saving credit card numbers is not any more expensive than swiping a card, and saves time in the long run and potential awkwardness at the end of a session.

- A higher volume of processed credit cards might allow you to negotiate your rates.

- Check if your bank offers a less expensive option. Some banks offer preferred rates for their customers.

Also consider the time and possible expense of ensuring that you are Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard compliant (information security standards that aim to keep cardholder data secure).

Different methods of processing transactions have varying levels of requirements:

- A swiping reader with a terminal connected to a telephone line is more secure than through the Internet and carries fewer compliance burdens. Use a reader that can handle chip-cards, because you could be liable for fraudulent transactions.

- Do not save or store credit card numbers you typed yourself. Compliance is less burdensome if patients input credit card data into a secure portal.

- Store credit card data securely via your credit card processing partner, although the partner is still at risk of a data breach. Practitioners should weigh the value of convenience vs security.

- If there is a data breach and you are found negligent you could be fined $5,000 to $100,000 per month, depending on whether you are a large company or solo practice.

Bottom dollar

Credit card processing has significant advantages from both a practice management and clinical standpoint. Because prices for services vary, shop around to find the best rates and educate yourself about security requirements. Taking the time to research these matters can pay off in the long term.

Are you tired of waiting for checks in the mail? Do patients leave without paying their balance? Streamlining revenue collection by taking credit cards is a tantalizing antidote to these ills, but it has downsides. Weighing the value for you and your patients is necessary before you decide on this important practice management policy.

Clinical and practical advantages

Many patients prefer that their health care practitioners take credit cards, because it simplifies their busy lives—and who carries a checkbook anymore? Patients can put the whole session to good use without sacrificing time taking care of payment. They also can receive credit card rewards for their payment, or use health savings accounts, health reimbursement accounts, or flexible spending debit cards, making treatment more affordable.

Benefits of credit cards

Accepting credit cards has many benefits:

- Allows more time in a session to focus on clinical matters because you do not have to allocate time to collect payment, which might include dealing with a forgotten checkbook or a request for a change in your payment policies.

- Easier to collect payment for no-shows. This could result in a reduced no-show rate, because a patient might feel more accountable to show up knowing that his (her) credit card is on file.

- Saves time recording and depositing checks.

- Avoids bounced checks and collection agencies.

Money doesn’t grow on trees

Although there are advantages to accepting credit cards, several costs should be considered. Some practitioners feel that accepting credit cards makes their practice seem like a commercial business. There also is an expense of accepting credit cards, and understanding these costs can be confusing because there are different processing systems of rates. Whether the rate is flat, tiered, or wholesale, you always will pay a percentage of the transaction, plus a transaction fee.

Here are some general guidelines on rates:

- Debit cards are the least expensive to process but often have low spending limits.

- Rewards cards, such as frequent flyer cards, are the most expensive to process. Have you ever wondered who foots the bill for those frequent flyer miles? It’s not the airline; it’s the merchant (you).

- For tiered rates, swiping cards is typically cheaper than typing in the credit card info. Tiered rates often have low rates, known as “teaser” rates, because they are applicable in far fewer cases.

- For flat or wholesale rates, securely saving credit card numbers is not any more expensive than swiping a card, and saves time in the long run and potential awkwardness at the end of a session.

- A higher volume of processed credit cards might allow you to negotiate your rates.

- Check if your bank offers a less expensive option. Some banks offer preferred rates for their customers.

Also consider the time and possible expense of ensuring that you are Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard compliant (information security standards that aim to keep cardholder data secure).

Different methods of processing transactions have varying levels of requirements:

- A swiping reader with a terminal connected to a telephone line is more secure than through the Internet and carries fewer compliance burdens. Use a reader that can handle chip-cards, because you could be liable for fraudulent transactions.

- Do not save or store credit card numbers you typed yourself. Compliance is less burdensome if patients input credit card data into a secure portal.

- Store credit card data securely via your credit card processing partner, although the partner is still at risk of a data breach. Practitioners should weigh the value of convenience vs security.

- If there is a data breach and you are found negligent you could be fined $5,000 to $100,000 per month, depending on whether you are a large company or solo practice.

Bottom dollar

Credit card processing has significant advantages from both a practice management and clinical standpoint. Because prices for services vary, shop around to find the best rates and educate yourself about security requirements. Taking the time to research these matters can pay off in the long term.

Is your patient’s valproic acid dosage too low or high? Adjust it with this equation

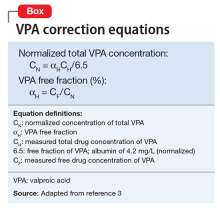

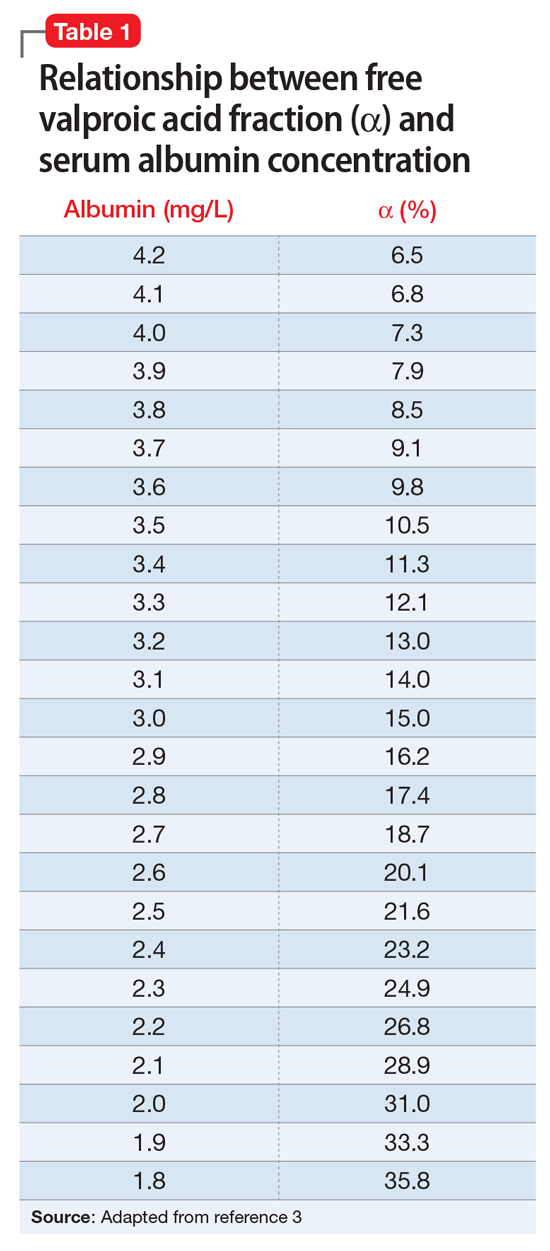

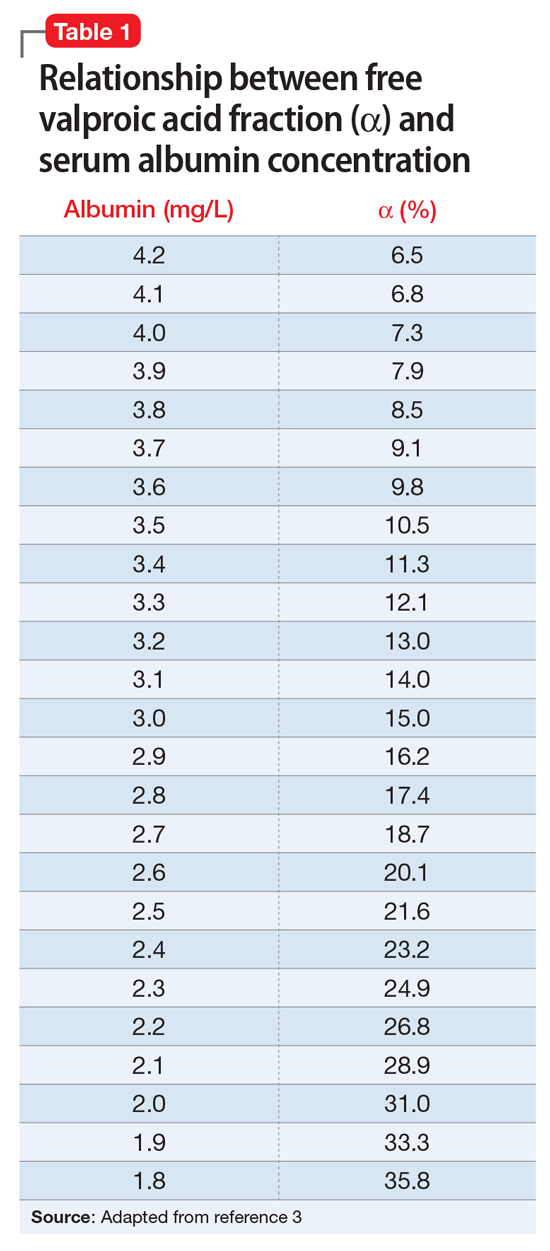

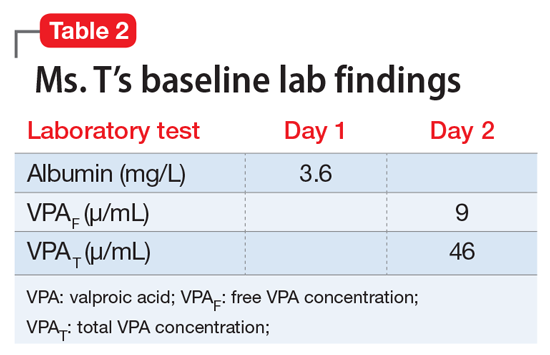

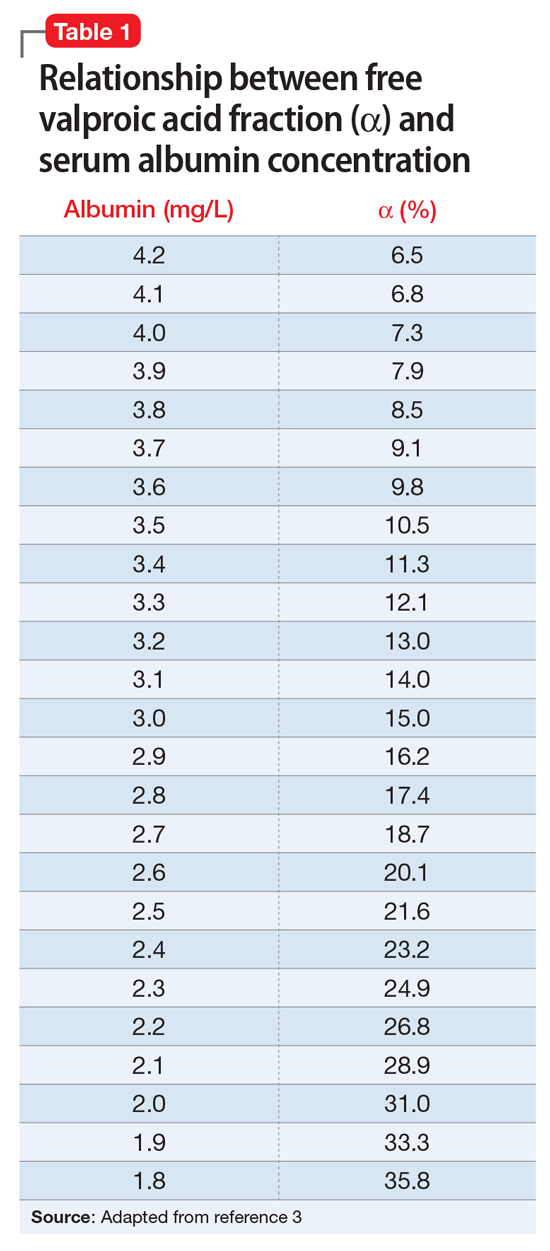

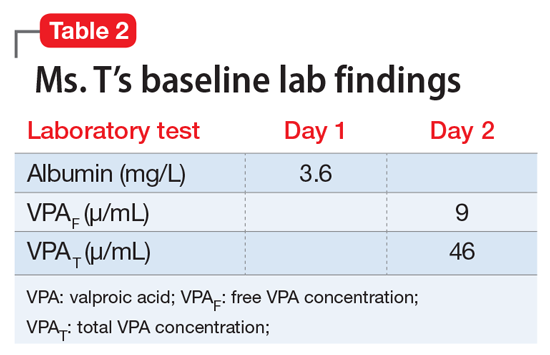

Valproic acid (VPA) often is used to treat mania in bipolar disorder, and it has a therapeutic range of 50 to 125 µg/mL of total serum concentration.1 VPA binds highly to albumin, resulting in free drug concentrations (5 to 15 mg/L) that are responsible for its therapeutic effect.2 Monitoring total VPA levels in patients with hypoalbuminemia could reveal seemingly subtherapeutic VPA levels, which could lead to unnecessary dosage adjustments or drug toxicity. Hermida et al3 devised a correction equation to normalize total VPA serum concentrations <75 µg/mL in patients with hypoalbuminemia (Table 1, Box).

We present a case employing this equation in a patient

Case

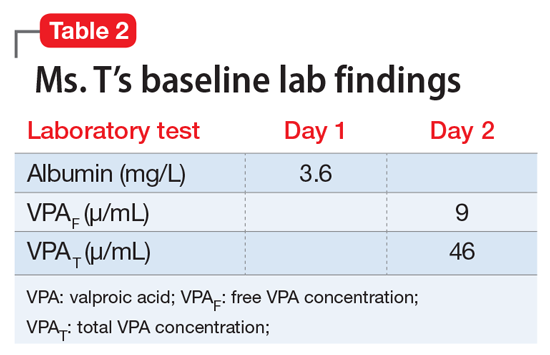

Ms. T, age 75, is admitted to the hospital with delusional, paranoid, assaultive, and combative behavior. By applying Ms. T’s baseline lab findings (Table 2) to the equation, a normalized total VPA level and estimated free VPA level of 70 µg/mL and 7 µg/mL, respectively, can be approximated. These estimates fall within the therapeutic range and are validated by the measured free VPA level of 9 µg/mL.

VPA serum levels should be assessed 2 to 4 days after initiation or dosage adjustments.1 Also, consider patient-specific goals and intended clinical effect when adjusting VPA dosage. In practice settings, where free VPA levels are not routinely monitored or are cost prohibitive, this equation can guide clinical decision-making.3

1. Depakote [divalproex sodium]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2016.

2. DeVane CL. Pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, and tolerability of valproate. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2003;37(suppl 2):25-42.

3. Hermida J, Tutor JC. A theoretical method for normalizing total serum valproic acid concentration in hypoalbuminemic patients. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;97(4):489-493.

Valproic acid (VPA) often is used to treat mania in bipolar disorder, and it has a therapeutic range of 50 to 125 µg/mL of total serum concentration.1 VPA binds highly to albumin, resulting in free drug concentrations (5 to 15 mg/L) that are responsible for its therapeutic effect.2 Monitoring total VPA levels in patients with hypoalbuminemia could reveal seemingly subtherapeutic VPA levels, which could lead to unnecessary dosage adjustments or drug toxicity. Hermida et al3 devised a correction equation to normalize total VPA serum concentrations <75 µg/mL in patients with hypoalbuminemia (Table 1, Box).

We present a case employing this equation in a patient

Case

Ms. T, age 75, is admitted to the hospital with delusional, paranoid, assaultive, and combative behavior. By applying Ms. T’s baseline lab findings (Table 2) to the equation, a normalized total VPA level and estimated free VPA level of 70 µg/mL and 7 µg/mL, respectively, can be approximated. These estimates fall within the therapeutic range and are validated by the measured free VPA level of 9 µg/mL.

VPA serum levels should be assessed 2 to 4 days after initiation or dosage adjustments.1 Also, consider patient-specific goals and intended clinical effect when adjusting VPA dosage. In practice settings, where free VPA levels are not routinely monitored or are cost prohibitive, this equation can guide clinical decision-making.3

Valproic acid (VPA) often is used to treat mania in bipolar disorder, and it has a therapeutic range of 50 to 125 µg/mL of total serum concentration.1 VPA binds highly to albumin, resulting in free drug concentrations (5 to 15 mg/L) that are responsible for its therapeutic effect.2 Monitoring total VPA levels in patients with hypoalbuminemia could reveal seemingly subtherapeutic VPA levels, which could lead to unnecessary dosage adjustments or drug toxicity. Hermida et al3 devised a correction equation to normalize total VPA serum concentrations <75 µg/mL in patients with hypoalbuminemia (Table 1, Box).

We present a case employing this equation in a patient

Case

Ms. T, age 75, is admitted to the hospital with delusional, paranoid, assaultive, and combative behavior. By applying Ms. T’s baseline lab findings (Table 2) to the equation, a normalized total VPA level and estimated free VPA level of 70 µg/mL and 7 µg/mL, respectively, can be approximated. These estimates fall within the therapeutic range and are validated by the measured free VPA level of 9 µg/mL.

VPA serum levels should be assessed 2 to 4 days after initiation or dosage adjustments.1 Also, consider patient-specific goals and intended clinical effect when adjusting VPA dosage. In practice settings, where free VPA levels are not routinely monitored or are cost prohibitive, this equation can guide clinical decision-making.3

1. Depakote [divalproex sodium]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2016.

2. DeVane CL. Pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, and tolerability of valproate. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2003;37(suppl 2):25-42.

3. Hermida J, Tutor JC. A theoretical method for normalizing total serum valproic acid concentration in hypoalbuminemic patients. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;97(4):489-493.

1. Depakote [divalproex sodium]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2016.

2. DeVane CL. Pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, and tolerability of valproate. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2003;37(suppl 2):25-42.

3. Hermida J, Tutor JC. A theoretical method for normalizing total serum valproic acid concentration in hypoalbuminemic patients. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;97(4):489-493.

Understanding the brexpiprazole therapeutic window: Why more isn’t always better

Dosage windows could be difficult to understand pharmacologically, but for a partial agonist the presumed mechanism could be more evident. Clinicians should be aware that more is not always better, meaning that with partial agonist drugs a higher dosage might not lead to greater patient response. With brexpiprazole, a dopamine D2 partial agonist FDA-approved for schizophrenia and an adjunct for major depressive disorder (MDD),1 moderation is best because of

Recommended dosage

Two placebo-controlled studies2,3 examined brexpiprazole dosages of 1, 2, and 3 mg/d. The recommended dosage of 2 mg/d for MDD was determined by changes in Montgomery-Åsburg Depression Rating Scale scores (Figure).4 Lower dosages of 1 mg/d did not reach statistical significance, and 3 mg/d were less effective than the intermediate dosage of 2 mg/d. This result suggests a window of efficacy for brexpiprazole for MDD. This therapeutic window likely applies to most patients; however, patient-specific variables could alter the optimum dosage.

Dosage window

Brexpiprazole has high affinity for dopamine D2, D3, serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, norepinephrine α1B, and α2 Creceptors. At relatively low drug concentrations, brexpiprazole achieves high receptor occupancy. At receptors for which brexpiprazole is a partial agonist (5-HT1A, D2, D3) the drug blocks the receptor and stimulates it at a fraction of the endogenous neurotransmitter. With a very high affinity agent, the endogenous neurotransmitter could be completely excluded from interacting with these receptors if brexpiprazole occupancy is high. At lower dosages, the drug occupies only a fraction of the receptors, allowing the endogenous neurotransmitters to continue interacting with their receptors, thereby magnifying the signal of that receptor above baseline.

1. FDA approves Rexulti (brexpiprazole) as adjunctive treatment for adults with major depressive disorder and as a treatment for adults with schizophrenia [news release]. Valby, Denmark; Tokyo, Japan: H. Lundbeck A/S (Lundbeck); Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd; July 11, 2015. http://investor.lundbeck.com/ releasedetail.cfm?Release ID=921621. Accessed October 3, 2015.

2. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Adjunctive brexpiprazole 1 and 3 mg for patients with major depressive disorder following inadequate response to antidepressants: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9): 1232-1240.

3. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive brexpiprazole 2 mg in major depressive disorder: a phase 3, randomized, placebocontrolled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9):1224-1231.

4. Rexulti [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Otsuka; 2015.

Dosage windows could be difficult to understand pharmacologically, but for a partial agonist the presumed mechanism could be more evident. Clinicians should be aware that more is not always better, meaning that with partial agonist drugs a higher dosage might not lead to greater patient response. With brexpiprazole, a dopamine D2 partial agonist FDA-approved for schizophrenia and an adjunct for major depressive disorder (MDD),1 moderation is best because of

Recommended dosage

Two placebo-controlled studies2,3 examined brexpiprazole dosages of 1, 2, and 3 mg/d. The recommended dosage of 2 mg/d for MDD was determined by changes in Montgomery-Åsburg Depression Rating Scale scores (Figure).4 Lower dosages of 1 mg/d did not reach statistical significance, and 3 mg/d were less effective than the intermediate dosage of 2 mg/d. This result suggests a window of efficacy for brexpiprazole for MDD. This therapeutic window likely applies to most patients; however, patient-specific variables could alter the optimum dosage.

Dosage window

Brexpiprazole has high affinity for dopamine D2, D3, serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, norepinephrine α1B, and α2 Creceptors. At relatively low drug concentrations, brexpiprazole achieves high receptor occupancy. At receptors for which brexpiprazole is a partial agonist (5-HT1A, D2, D3) the drug blocks the receptor and stimulates it at a fraction of the endogenous neurotransmitter. With a very high affinity agent, the endogenous neurotransmitter could be completely excluded from interacting with these receptors if brexpiprazole occupancy is high. At lower dosages, the drug occupies only a fraction of the receptors, allowing the endogenous neurotransmitters to continue interacting with their receptors, thereby magnifying the signal of that receptor above baseline.

Dosage windows could be difficult to understand pharmacologically, but for a partial agonist the presumed mechanism could be more evident. Clinicians should be aware that more is not always better, meaning that with partial agonist drugs a higher dosage might not lead to greater patient response. With brexpiprazole, a dopamine D2 partial agonist FDA-approved for schizophrenia and an adjunct for major depressive disorder (MDD),1 moderation is best because of

Recommended dosage

Two placebo-controlled studies2,3 examined brexpiprazole dosages of 1, 2, and 3 mg/d. The recommended dosage of 2 mg/d for MDD was determined by changes in Montgomery-Åsburg Depression Rating Scale scores (Figure).4 Lower dosages of 1 mg/d did not reach statistical significance, and 3 mg/d were less effective than the intermediate dosage of 2 mg/d. This result suggests a window of efficacy for brexpiprazole for MDD. This therapeutic window likely applies to most patients; however, patient-specific variables could alter the optimum dosage.

Dosage window

Brexpiprazole has high affinity for dopamine D2, D3, serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, norepinephrine α1B, and α2 Creceptors. At relatively low drug concentrations, brexpiprazole achieves high receptor occupancy. At receptors for which brexpiprazole is a partial agonist (5-HT1A, D2, D3) the drug blocks the receptor and stimulates it at a fraction of the endogenous neurotransmitter. With a very high affinity agent, the endogenous neurotransmitter could be completely excluded from interacting with these receptors if brexpiprazole occupancy is high. At lower dosages, the drug occupies only a fraction of the receptors, allowing the endogenous neurotransmitters to continue interacting with their receptors, thereby magnifying the signal of that receptor above baseline.

1. FDA approves Rexulti (brexpiprazole) as adjunctive treatment for adults with major depressive disorder and as a treatment for adults with schizophrenia [news release]. Valby, Denmark; Tokyo, Japan: H. Lundbeck A/S (Lundbeck); Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd; July 11, 2015. http://investor.lundbeck.com/ releasedetail.cfm?Release ID=921621. Accessed October 3, 2015.

2. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Adjunctive brexpiprazole 1 and 3 mg for patients with major depressive disorder following inadequate response to antidepressants: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9): 1232-1240.

3. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive brexpiprazole 2 mg in major depressive disorder: a phase 3, randomized, placebocontrolled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9):1224-1231.

4. Rexulti [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Otsuka; 2015.

1. FDA approves Rexulti (brexpiprazole) as adjunctive treatment for adults with major depressive disorder and as a treatment for adults with schizophrenia [news release]. Valby, Denmark; Tokyo, Japan: H. Lundbeck A/S (Lundbeck); Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd; July 11, 2015. http://investor.lundbeck.com/ releasedetail.cfm?Release ID=921621. Accessed October 3, 2015.

2. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Adjunctive brexpiprazole 1 and 3 mg for patients with major depressive disorder following inadequate response to antidepressants: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9): 1232-1240.

3. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive brexpiprazole 2 mg in major depressive disorder: a phase 3, randomized, placebocontrolled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9):1224-1231.

4. Rexulti [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Otsuka; 2015.

When to consider cranial electrotherapy stimulation for patients with PTSD

Individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often report cognitive and sleep disturbances, such as insomnia and poor concentration. Although many patients report improvement with traditional evidence-based treatments, such as pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, it might be valuable to consider complementary or alternative therapies. Many patients seek treatments that they can self-administer as needed, at their convenience, particularly during symptom exacerbation. One treatment option is cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES).

As a medical device, CES has been cleared—rather than approved, as is the case for medications—by the FDA to treat depression, insomnia, and anxiety.1 In the United States, CES devices require a prescription from a licensed health care practitioner, but they are available without a prescription in other countries. Cost for devices range from $600 to $1,200 and $10 to $20 for electrodes and contact solution. However, insurance companies that provide coverage for durable medical equipment might cover some or all of this expense.

How CES works

After applying contact solution, depending on the device used, the user attaches electrodes to the earlobes, mastoid processes, or other parts of the head that deliver a pulsed current, usually from AA batteries for 20 to 60 minutes.1 The current causes cortical deactivation and could affect emotional regulation by influencing neurotransmission in the thalamus, hypothalamus, and limbic system.1,2 CES increases cerebrospinal fluid levels of beta-endorphin, adrenocorticotropic hormone, and serotonin, which play a role in depression and anxiety.3

There are no known contraindications for CES. Adverse effects are rare, temporary, and mild; skin irritation, vertigo, or headache are the most common.1

Evidence of efficacy

There are no double-blind placebo-controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of CES for PTSD. However, there is a case series and a large survey of patients supporting its use.

- In a case series, 2 patients reported improved occupational functioning and reduced PTSD symptoms after using CES, 100 to 500 mA, 20 to 60 minutes a day, 3 to 5 days per week.4

- In an online survey of 145 veterans and active-duty military personnel, 60% of individuals used CES for PTSD, and 20% of those individuals were not receiving pharmacotherapy.5 Participants reported at least a 25% reduction in symptoms using CES for at least 20 minutes, once or twice daily, with a current of 100 to 600 mA.5

- In an expert opinion, patients noted improved sleep quality and reduced alcohol and drug withdrawal symptoms after 20-minute treatments, twice a day, with a current of 2 mA. Currents could be increased to 4 mA, if there was no improvement after 2 weeks.6

Some patients experiencing exacerbation of PTSD symptoms could benefit from using the device for 1 hour several times a day until symptoms subside.5

Optimal strength, frequency, and duration of treatment vary among patients, and further studies are needed to assess these parameters as well as efficacy because definitive studies are currently lacking. CES has not always shown efficacy, such as in some patients with depression.7 Despite the limited evidence base, it is reasonable to consider CES for patients with PTSD. This modality might be helpful for patients who have comorbid pain, anxiety, and insomnia, or for those who seek a complementary, convenient, safe, self-administered treatment.

1. Kirsch DL, Nichols F. Cranial electrotherapy stimulation for treatment of anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36(1):169-176.

2. Feusner JD, Madsen S, Moody TD, et al. Effects of cranial electrotherapy stimulation on resting state brain activity. Brain Behav. 2012;2(3):211-220.

3. Shealy CN, Cady RK, Culver-Veehoff D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma neurochemicals: response to cranial electrical stimulation. J Neuro Orthop Med Surg. 1998;18(2):94-97.

4. Bracciano AG, Chang WP, Kokesh S, et al. Cranial electrotherapy stimulation in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study of two military veterans. J Neurother. 2012;16(1):60-69.

5. Kirsch DL, Price LR, Nichols F, et al. Military service member and veteran self reports of efficacy of cranial electrotherapy stimulation for anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, insomnia, and depression. US Army Med Dep J. 2014:46-54.

6. Xenakis SN. The rise of cranial electrotherapy. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/electroconvulsive-therapy/rise-cranial-electrotherapy. Published July 24, 2014. Accessed December 20, 2016.

7. Mischoulon D, De Jong MF, Vitolo OV, et al. Efficacy and safety of a form of cranial electrical stimulation (CES) as an add-on intervention for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder: a three week double blind pilot study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;70:98-105.

Individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often report cognitive and sleep disturbances, such as insomnia and poor concentration. Although many patients report improvement with traditional evidence-based treatments, such as pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, it might be valuable to consider complementary or alternative therapies. Many patients seek treatments that they can self-administer as needed, at their convenience, particularly during symptom exacerbation. One treatment option is cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES).

As a medical device, CES has been cleared—rather than approved, as is the case for medications—by the FDA to treat depression, insomnia, and anxiety.1 In the United States, CES devices require a prescription from a licensed health care practitioner, but they are available without a prescription in other countries. Cost for devices range from $600 to $1,200 and $10 to $20 for electrodes and contact solution. However, insurance companies that provide coverage for durable medical equipment might cover some or all of this expense.

How CES works

After applying contact solution, depending on the device used, the user attaches electrodes to the earlobes, mastoid processes, or other parts of the head that deliver a pulsed current, usually from AA batteries for 20 to 60 minutes.1 The current causes cortical deactivation and could affect emotional regulation by influencing neurotransmission in the thalamus, hypothalamus, and limbic system.1,2 CES increases cerebrospinal fluid levels of beta-endorphin, adrenocorticotropic hormone, and serotonin, which play a role in depression and anxiety.3

There are no known contraindications for CES. Adverse effects are rare, temporary, and mild; skin irritation, vertigo, or headache are the most common.1

Evidence of efficacy

There are no double-blind placebo-controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of CES for PTSD. However, there is a case series and a large survey of patients supporting its use.

- In a case series, 2 patients reported improved occupational functioning and reduced PTSD symptoms after using CES, 100 to 500 mA, 20 to 60 minutes a day, 3 to 5 days per week.4

- In an online survey of 145 veterans and active-duty military personnel, 60% of individuals used CES for PTSD, and 20% of those individuals were not receiving pharmacotherapy.5 Participants reported at least a 25% reduction in symptoms using CES for at least 20 minutes, once or twice daily, with a current of 100 to 600 mA.5

- In an expert opinion, patients noted improved sleep quality and reduced alcohol and drug withdrawal symptoms after 20-minute treatments, twice a day, with a current of 2 mA. Currents could be increased to 4 mA, if there was no improvement after 2 weeks.6

Some patients experiencing exacerbation of PTSD symptoms could benefit from using the device for 1 hour several times a day until symptoms subside.5

Optimal strength, frequency, and duration of treatment vary among patients, and further studies are needed to assess these parameters as well as efficacy because definitive studies are currently lacking. CES has not always shown efficacy, such as in some patients with depression.7 Despite the limited evidence base, it is reasonable to consider CES for patients with PTSD. This modality might be helpful for patients who have comorbid pain, anxiety, and insomnia, or for those who seek a complementary, convenient, safe, self-administered treatment.

Individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often report cognitive and sleep disturbances, such as insomnia and poor concentration. Although many patients report improvement with traditional evidence-based treatments, such as pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, it might be valuable to consider complementary or alternative therapies. Many patients seek treatments that they can self-administer as needed, at their convenience, particularly during symptom exacerbation. One treatment option is cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES).

As a medical device, CES has been cleared—rather than approved, as is the case for medications—by the FDA to treat depression, insomnia, and anxiety.1 In the United States, CES devices require a prescription from a licensed health care practitioner, but they are available without a prescription in other countries. Cost for devices range from $600 to $1,200 and $10 to $20 for electrodes and contact solution. However, insurance companies that provide coverage for durable medical equipment might cover some or all of this expense.

How CES works

After applying contact solution, depending on the device used, the user attaches electrodes to the earlobes, mastoid processes, or other parts of the head that deliver a pulsed current, usually from AA batteries for 20 to 60 minutes.1 The current causes cortical deactivation and could affect emotional regulation by influencing neurotransmission in the thalamus, hypothalamus, and limbic system.1,2 CES increases cerebrospinal fluid levels of beta-endorphin, adrenocorticotropic hormone, and serotonin, which play a role in depression and anxiety.3

There are no known contraindications for CES. Adverse effects are rare, temporary, and mild; skin irritation, vertigo, or headache are the most common.1

Evidence of efficacy

There are no double-blind placebo-controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of CES for PTSD. However, there is a case series and a large survey of patients supporting its use.

- In a case series, 2 patients reported improved occupational functioning and reduced PTSD symptoms after using CES, 100 to 500 mA, 20 to 60 minutes a day, 3 to 5 days per week.4

- In an online survey of 145 veterans and active-duty military personnel, 60% of individuals used CES for PTSD, and 20% of those individuals were not receiving pharmacotherapy.5 Participants reported at least a 25% reduction in symptoms using CES for at least 20 minutes, once or twice daily, with a current of 100 to 600 mA.5

- In an expert opinion, patients noted improved sleep quality and reduced alcohol and drug withdrawal symptoms after 20-minute treatments, twice a day, with a current of 2 mA. Currents could be increased to 4 mA, if there was no improvement after 2 weeks.6

Some patients experiencing exacerbation of PTSD symptoms could benefit from using the device for 1 hour several times a day until symptoms subside.5

Optimal strength, frequency, and duration of treatment vary among patients, and further studies are needed to assess these parameters as well as efficacy because definitive studies are currently lacking. CES has not always shown efficacy, such as in some patients with depression.7 Despite the limited evidence base, it is reasonable to consider CES for patients with PTSD. This modality might be helpful for patients who have comorbid pain, anxiety, and insomnia, or for those who seek a complementary, convenient, safe, self-administered treatment.

1. Kirsch DL, Nichols F. Cranial electrotherapy stimulation for treatment of anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36(1):169-176.

2. Feusner JD, Madsen S, Moody TD, et al. Effects of cranial electrotherapy stimulation on resting state brain activity. Brain Behav. 2012;2(3):211-220.

3. Shealy CN, Cady RK, Culver-Veehoff D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma neurochemicals: response to cranial electrical stimulation. J Neuro Orthop Med Surg. 1998;18(2):94-97.

4. Bracciano AG, Chang WP, Kokesh S, et al. Cranial electrotherapy stimulation in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study of two military veterans. J Neurother. 2012;16(1):60-69.

5. Kirsch DL, Price LR, Nichols F, et al. Military service member and veteran self reports of efficacy of cranial electrotherapy stimulation for anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, insomnia, and depression. US Army Med Dep J. 2014:46-54.

6. Xenakis SN. The rise of cranial electrotherapy. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/electroconvulsive-therapy/rise-cranial-electrotherapy. Published July 24, 2014. Accessed December 20, 2016.

7. Mischoulon D, De Jong MF, Vitolo OV, et al. Efficacy and safety of a form of cranial electrical stimulation (CES) as an add-on intervention for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder: a three week double blind pilot study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;70:98-105.

1. Kirsch DL, Nichols F. Cranial electrotherapy stimulation for treatment of anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36(1):169-176.

2. Feusner JD, Madsen S, Moody TD, et al. Effects of cranial electrotherapy stimulation on resting state brain activity. Brain Behav. 2012;2(3):211-220.

3. Shealy CN, Cady RK, Culver-Veehoff D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma neurochemicals: response to cranial electrical stimulation. J Neuro Orthop Med Surg. 1998;18(2):94-97.

4. Bracciano AG, Chang WP, Kokesh S, et al. Cranial electrotherapy stimulation in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study of two military veterans. J Neurother. 2012;16(1):60-69.

5. Kirsch DL, Price LR, Nichols F, et al. Military service member and veteran self reports of efficacy of cranial electrotherapy stimulation for anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, insomnia, and depression. US Army Med Dep J. 2014:46-54.

6. Xenakis SN. The rise of cranial electrotherapy. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/electroconvulsive-therapy/rise-cranial-electrotherapy. Published July 24, 2014. Accessed December 20, 2016.

7. Mischoulon D, De Jong MF, Vitolo OV, et al. Efficacy and safety of a form of cranial electrical stimulation (CES) as an add-on intervention for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder: a three week double blind pilot study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;70:98-105.

CORRECT: Insights into working at correctional facilities

Providing care in a correctional facility is inherent with danger, complexities, and risks. The mnemonic CORRECT strives to shed light on some of these factors and to provide a window of understanding on the needs and experiences of patients and staff in correctional facilities.

Challenges. The inherently coercive environment of a correctional facility affects all those confined within—staff and inmates. Staff members have varied background and experience (ie, custody, medical services, and mental health services). A large percentage of incarcerated individuals have been diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder, substance use disorder, psychosis, or medical illnesses. Many of these individuals have received little, if any, treatment, and are monitored most of the time by custody staff, who have limited training in mental health care.

Inmates also have considerable interaction with medical services. The goals of medical and psychiatric providers differ from that of corrections: to diagnose and treat vs to confine, deter, and punish.1 Disagreements and friction may be inevitable and require ongoing diplomacy.

Opportunity. Many inmates have a history of homelessness and arrive with untreated medical conditions; hypertension, impaired liver function, tuberculosis, and hepatitis C are common. Correctional facilities often become primary care providers for the physically and mentally ill. Inmates might have never received any form of patient education, and could respond well to patience, education, and compassion. Challenges can become opportunities to help this neglected, underserved, and underprivileged population.

Reflection. The need to continually assess a patient and provide a treatment plan is not unique to corrections. However, the patient caseload, the day-to-day continuum, and the need to complete patient care within time restrictions, can become a mundane process that could invite a sense of conditioned familiarity and boredom over the years, despite the predictable unpredictability of a correctional setting. The need to periodically stop and reflect is crucial, which can be done independently or with ongoing staff education.

Risks. A heightened level of risk starts from the time the incarcerated individual enters the correctional facility to the moment he (she) is released. This involves many facets, including physical, psychological, and medical exposure. Individuals could arrive in a state of drug withdrawal, and often in a state of delirium, which can complicate the presentation.

Potential inmate–inmate conflicts are a constant risk. Trading and swapping medications for sedative purposes or to get “high” is common in most correctional facilities, which has prompted many institutions to remove select medications from their formulary. Some individuals might prey on the novice, weak, or elderly inmates if they are taking sought-after medications. The suicide rate is high in correctional facilities. Because of these increased risks, the psychiatrist needs to be mindful of prescribing practices.

Experience. Despite years of education in medical school, residency, and fellowships, there is no substitute for clinical experience for novice correctional psychiatrists. Becoming competent can take years, and requires face-to-face evaluations, immersion, presence, and movement within a facility, and on-call responsibilities. Telepsychiatry is no replacement for the experience of being “in the trenches.” Despite a position of apparent power and superiority, physicians are human. Learning from mistakes is crucial to evolve and improve patient rapport.

Confidentiality. Lack of confidentiality often is the norm. Custody staff might be present during evaluations because of the potentially dangerous environment. Because certain areas of the facility require further caution, such as single cells or solitary confinement (as a result of unpredictability, dangerousness, specific charges, behavioral problems, etc.), the psychiatrist might be required to perform assessments at the front of the cell, in the presence of adjacent cells and other inmates and often an entire group. This might be unavoidable and requires a higher level of sensitivity. The need for correctional employees to maintain a sense of confidentiality has been well demonstrated in media events regarding serious boundary violations or sexual contact.

Treatment. Psychiatrists “confined” in corrections could feel isolated from the “outside” world and from their professional colleagues. Therefore, clinicians employed in corrections could develop a specific variety of burnout. Avoiding burnout requires a mindful discipline in self-care, efforts in healthy socialization, recreation, and outdoor activities. It’s crucial to maintain and update one’s knowledge base in order to provide treatment within the standard of care.

1. Dubler N. Ethical dilemmas in prison and jail health care. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/03/10/ethical-dilemmas-in-prison-and-jail-health-care. Published March 10, 2014. Accessed December 14, 2016.

Providing care in a correctional facility is inherent with danger, complexities, and risks. The mnemonic CORRECT strives to shed light on some of these factors and to provide a window of understanding on the needs and experiences of patients and staff in correctional facilities.

Challenges. The inherently coercive environment of a correctional facility affects all those confined within—staff and inmates. Staff members have varied background and experience (ie, custody, medical services, and mental health services). A large percentage of incarcerated individuals have been diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder, substance use disorder, psychosis, or medical illnesses. Many of these individuals have received little, if any, treatment, and are monitored most of the time by custody staff, who have limited training in mental health care.

Inmates also have considerable interaction with medical services. The goals of medical and psychiatric providers differ from that of corrections: to diagnose and treat vs to confine, deter, and punish.1 Disagreements and friction may be inevitable and require ongoing diplomacy.

Opportunity. Many inmates have a history of homelessness and arrive with untreated medical conditions; hypertension, impaired liver function, tuberculosis, and hepatitis C are common. Correctional facilities often become primary care providers for the physically and mentally ill. Inmates might have never received any form of patient education, and could respond well to patience, education, and compassion. Challenges can become opportunities to help this neglected, underserved, and underprivileged population.

Reflection. The need to continually assess a patient and provide a treatment plan is not unique to corrections. However, the patient caseload, the day-to-day continuum, and the need to complete patient care within time restrictions, can become a mundane process that could invite a sense of conditioned familiarity and boredom over the years, despite the predictable unpredictability of a correctional setting. The need to periodically stop and reflect is crucial, which can be done independently or with ongoing staff education.

Risks. A heightened level of risk starts from the time the incarcerated individual enters the correctional facility to the moment he (she) is released. This involves many facets, including physical, psychological, and medical exposure. Individuals could arrive in a state of drug withdrawal, and often in a state of delirium, which can complicate the presentation.

Potential inmate–inmate conflicts are a constant risk. Trading and swapping medications for sedative purposes or to get “high” is common in most correctional facilities, which has prompted many institutions to remove select medications from their formulary. Some individuals might prey on the novice, weak, or elderly inmates if they are taking sought-after medications. The suicide rate is high in correctional facilities. Because of these increased risks, the psychiatrist needs to be mindful of prescribing practices.

Experience. Despite years of education in medical school, residency, and fellowships, there is no substitute for clinical experience for novice correctional psychiatrists. Becoming competent can take years, and requires face-to-face evaluations, immersion, presence, and movement within a facility, and on-call responsibilities. Telepsychiatry is no replacement for the experience of being “in the trenches.” Despite a position of apparent power and superiority, physicians are human. Learning from mistakes is crucial to evolve and improve patient rapport.

Confidentiality. Lack of confidentiality often is the norm. Custody staff might be present during evaluations because of the potentially dangerous environment. Because certain areas of the facility require further caution, such as single cells or solitary confinement (as a result of unpredictability, dangerousness, specific charges, behavioral problems, etc.), the psychiatrist might be required to perform assessments at the front of the cell, in the presence of adjacent cells and other inmates and often an entire group. This might be unavoidable and requires a higher level of sensitivity. The need for correctional employees to maintain a sense of confidentiality has been well demonstrated in media events regarding serious boundary violations or sexual contact.

Treatment. Psychiatrists “confined” in corrections could feel isolated from the “outside” world and from their professional colleagues. Therefore, clinicians employed in corrections could develop a specific variety of burnout. Avoiding burnout requires a mindful discipline in self-care, efforts in healthy socialization, recreation, and outdoor activities. It’s crucial to maintain and update one’s knowledge base in order to provide treatment within the standard of care.

Providing care in a correctional facility is inherent with danger, complexities, and risks. The mnemonic CORRECT strives to shed light on some of these factors and to provide a window of understanding on the needs and experiences of patients and staff in correctional facilities.

Challenges. The inherently coercive environment of a correctional facility affects all those confined within—staff and inmates. Staff members have varied background and experience (ie, custody, medical services, and mental health services). A large percentage of incarcerated individuals have been diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder, substance use disorder, psychosis, or medical illnesses. Many of these individuals have received little, if any, treatment, and are monitored most of the time by custody staff, who have limited training in mental health care.

Inmates also have considerable interaction with medical services. The goals of medical and psychiatric providers differ from that of corrections: to diagnose and treat vs to confine, deter, and punish.1 Disagreements and friction may be inevitable and require ongoing diplomacy.

Opportunity. Many inmates have a history of homelessness and arrive with untreated medical conditions; hypertension, impaired liver function, tuberculosis, and hepatitis C are common. Correctional facilities often become primary care providers for the physically and mentally ill. Inmates might have never received any form of patient education, and could respond well to patience, education, and compassion. Challenges can become opportunities to help this neglected, underserved, and underprivileged population.

Reflection. The need to continually assess a patient and provide a treatment plan is not unique to corrections. However, the patient caseload, the day-to-day continuum, and the need to complete patient care within time restrictions, can become a mundane process that could invite a sense of conditioned familiarity and boredom over the years, despite the predictable unpredictability of a correctional setting. The need to periodically stop and reflect is crucial, which can be done independently or with ongoing staff education.

Risks. A heightened level of risk starts from the time the incarcerated individual enters the correctional facility to the moment he (she) is released. This involves many facets, including physical, psychological, and medical exposure. Individuals could arrive in a state of drug withdrawal, and often in a state of delirium, which can complicate the presentation.

Potential inmate–inmate conflicts are a constant risk. Trading and swapping medications for sedative purposes or to get “high” is common in most correctional facilities, which has prompted many institutions to remove select medications from their formulary. Some individuals might prey on the novice, weak, or elderly inmates if they are taking sought-after medications. The suicide rate is high in correctional facilities. Because of these increased risks, the psychiatrist needs to be mindful of prescribing practices.

Experience. Despite years of education in medical school, residency, and fellowships, there is no substitute for clinical experience for novice correctional psychiatrists. Becoming competent can take years, and requires face-to-face evaluations, immersion, presence, and movement within a facility, and on-call responsibilities. Telepsychiatry is no replacement for the experience of being “in the trenches.” Despite a position of apparent power and superiority, physicians are human. Learning from mistakes is crucial to evolve and improve patient rapport.

Confidentiality. Lack of confidentiality often is the norm. Custody staff might be present during evaluations because of the potentially dangerous environment. Because certain areas of the facility require further caution, such as single cells or solitary confinement (as a result of unpredictability, dangerousness, specific charges, behavioral problems, etc.), the psychiatrist might be required to perform assessments at the front of the cell, in the presence of adjacent cells and other inmates and often an entire group. This might be unavoidable and requires a higher level of sensitivity. The need for correctional employees to maintain a sense of confidentiality has been well demonstrated in media events regarding serious boundary violations or sexual contact.

Treatment. Psychiatrists “confined” in corrections could feel isolated from the “outside” world and from their professional colleagues. Therefore, clinicians employed in corrections could develop a specific variety of burnout. Avoiding burnout requires a mindful discipline in self-care, efforts in healthy socialization, recreation, and outdoor activities. It’s crucial to maintain and update one’s knowledge base in order to provide treatment within the standard of care.

1. Dubler N. Ethical dilemmas in prison and jail health care. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/03/10/ethical-dilemmas-in-prison-and-jail-health-care. Published March 10, 2014. Accessed December 14, 2016.

1. Dubler N. Ethical dilemmas in prison and jail health care. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/03/10/ethical-dilemmas-in-prison-and-jail-health-care. Published March 10, 2014. Accessed December 14, 2016.