User login

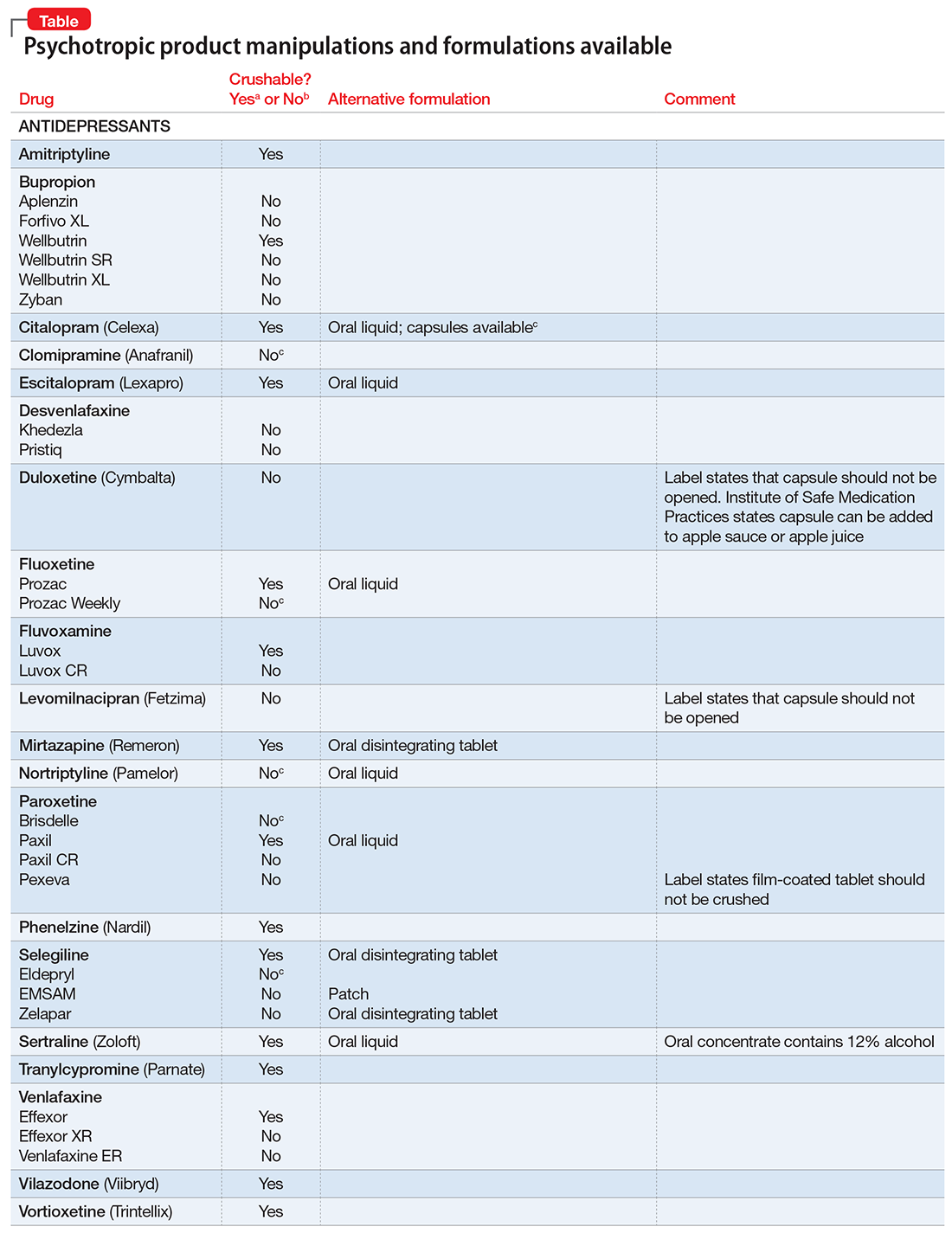

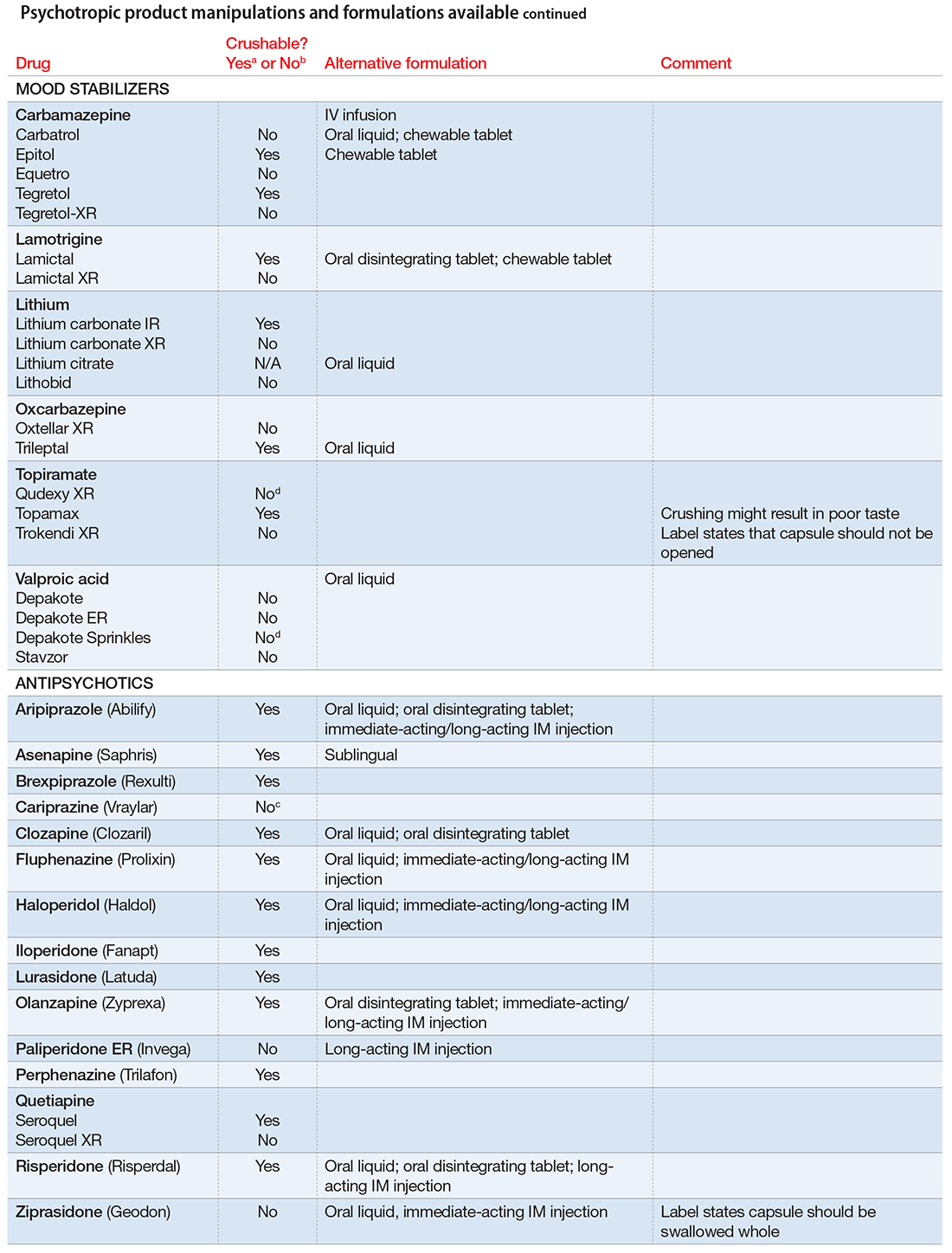

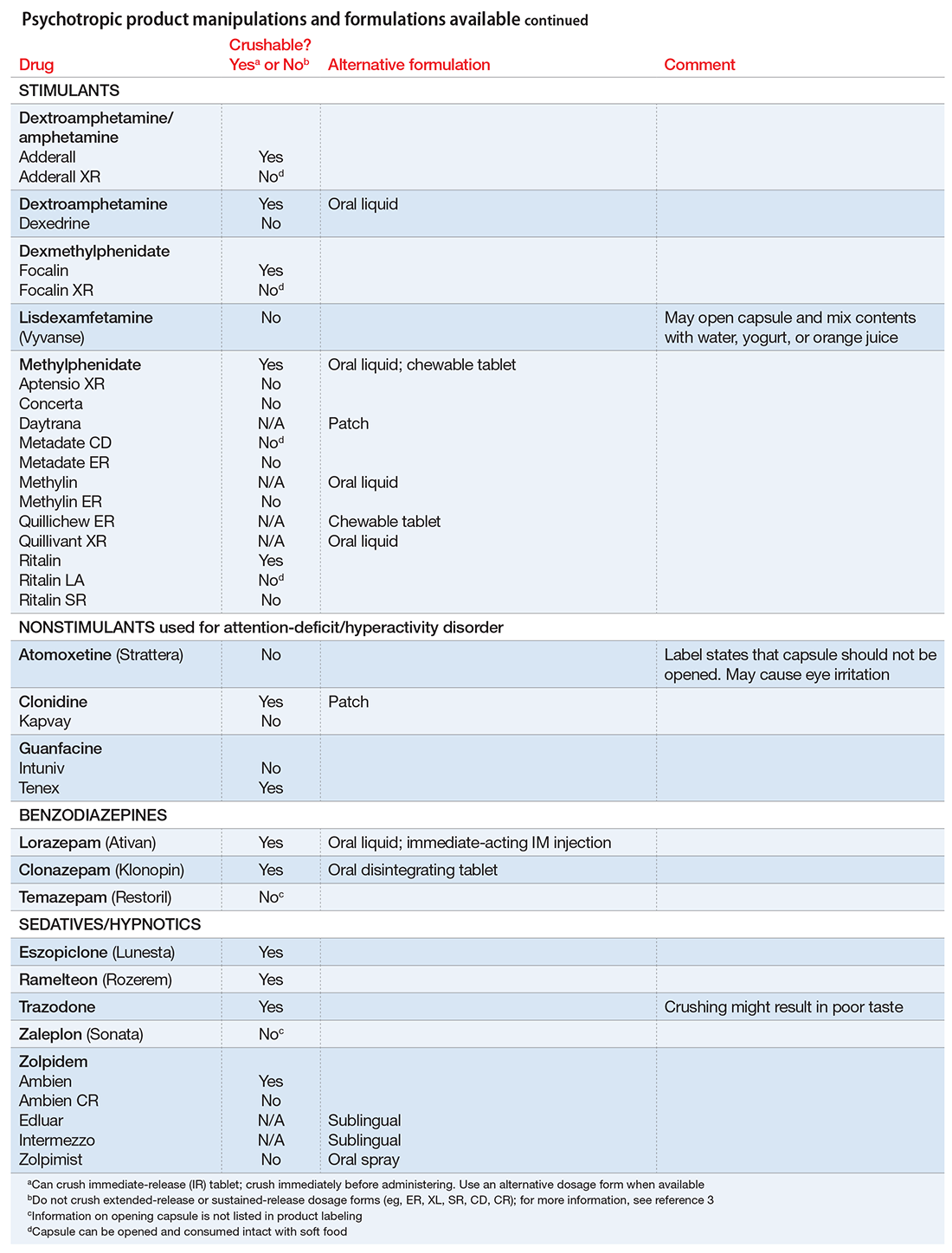

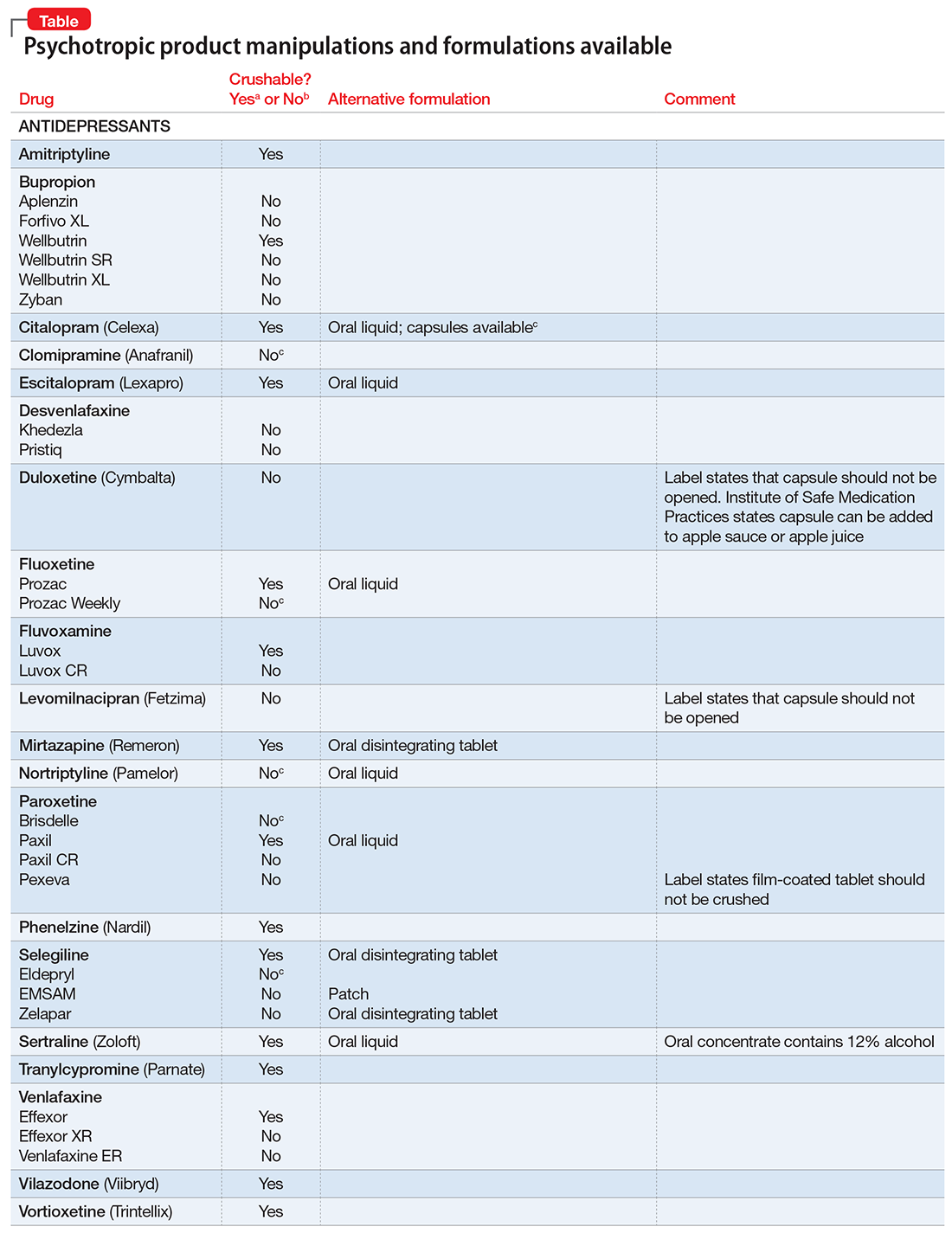

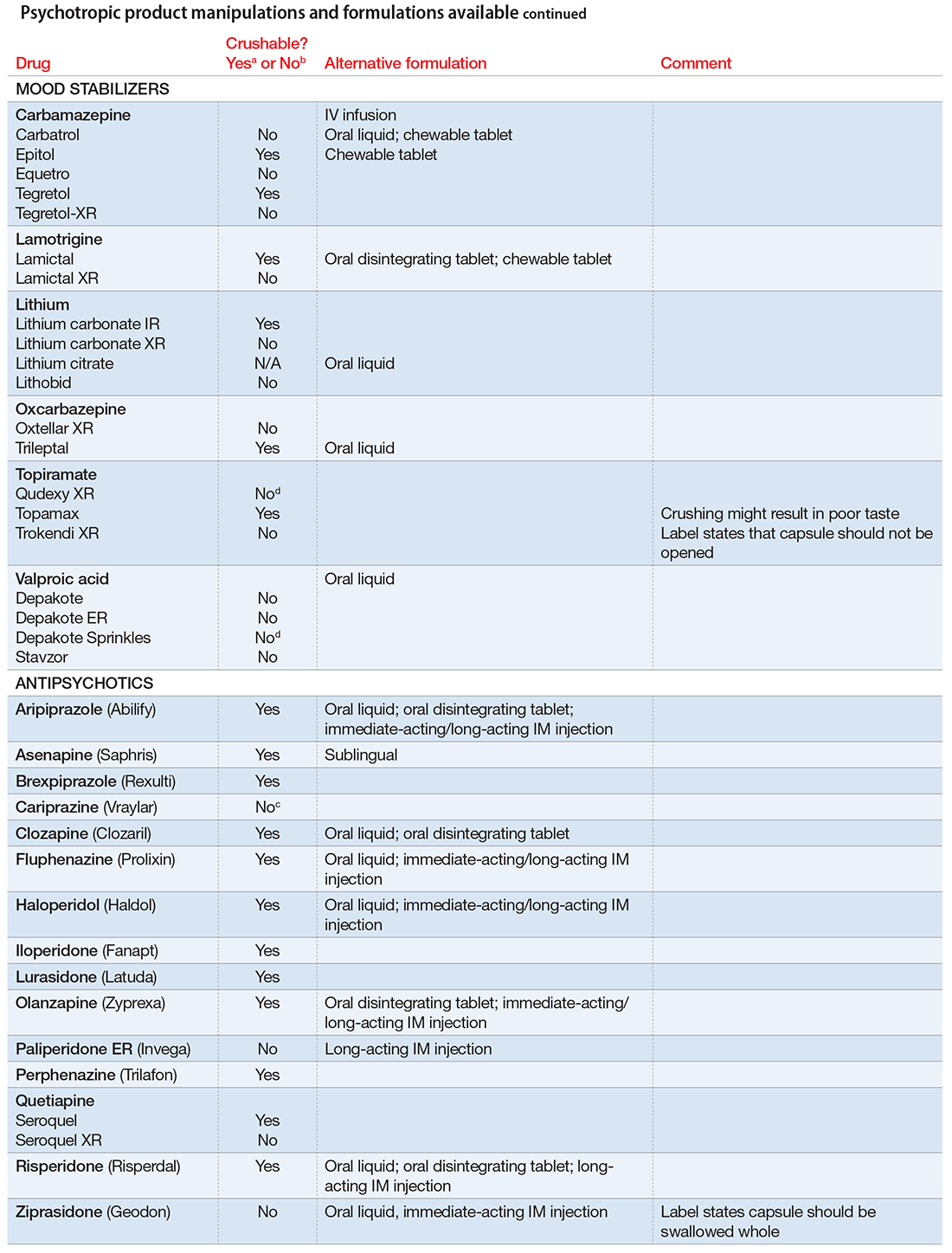

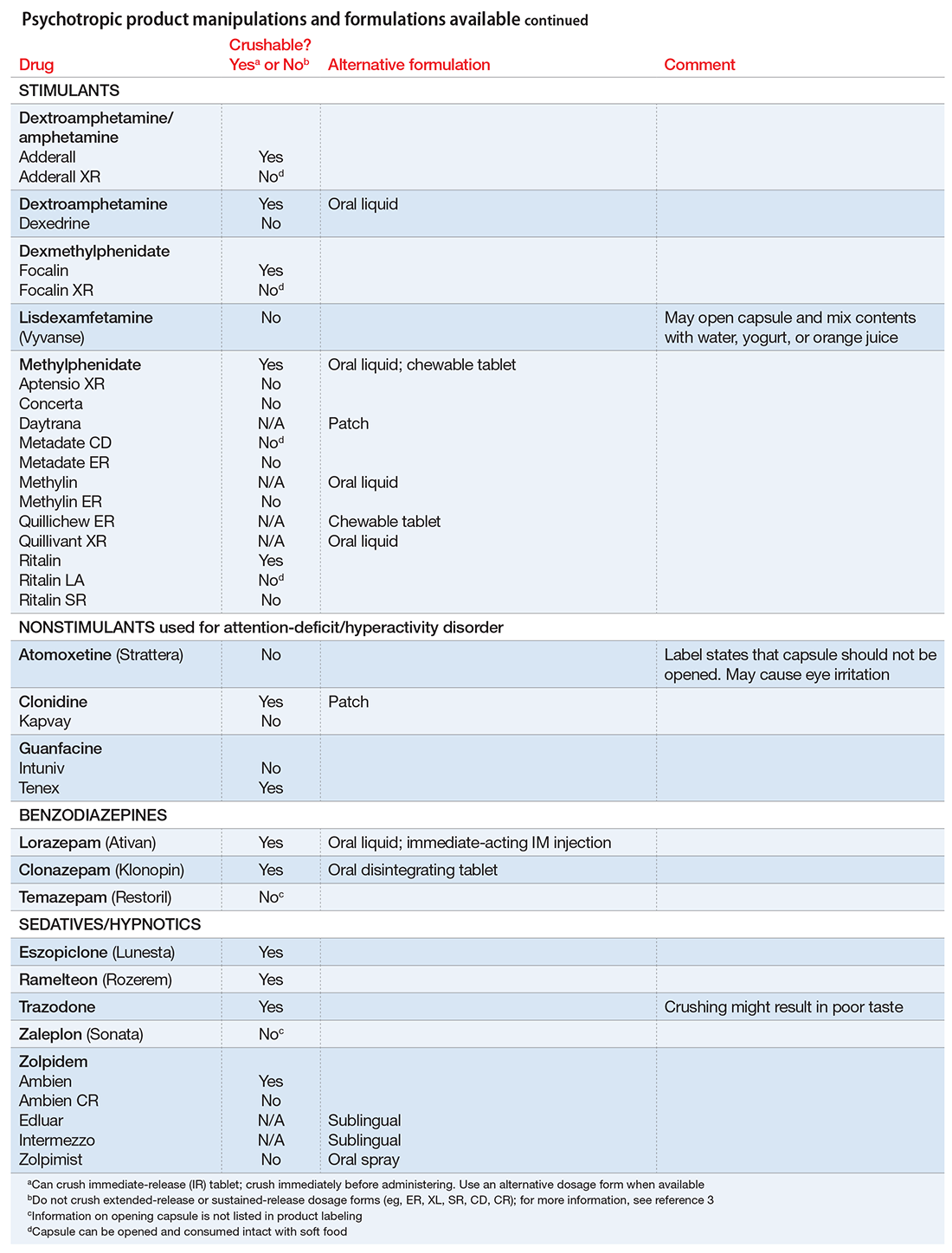

Pills to powder: An updated clinician’s reference for crushable psychotropics

Many patients experience difficulty swallowing pills, for various reasons:

- discomfort (particularly pediatric and geriatric patients)

- postsurgical need for an alternate route of enteral intake (nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, jejunostomy)

- dysphagia due to a neurologic disorder (multiple sclerosis, impaired gag reflex, dementing processes)

- odynophagia (pain upon swallowing) due to gastroesophageal reflux or a structural abnormality

- a structural abnormality of the head or neck that impairs swallowing.1

If these difficulties are not addressed, they can interfere with medication adherence. In those instances, using an alternative dosage form or manipulating an available formulation might be required.

Crushing guidelines

There are limited data on crushed-form products and their impact on efficacy. Therefore, when patients have difficulty taking pills, switching to liquid solution or orally disintegrating forms is recommended. However, most psychotropics are available only as tablets or capsules. Patients can crush their pills immediately before administration for easier intake. The following are some general guidelines for doing so:2

- Scored tablets typically can be crushed.

- Crushing sublingual and buccal tablets can alter their effectiveness.

- Crushing sustained-release medications can eliminate the sustained-release action.3

- Enteric-coated medications should not be crushed, because this can alter drug absorption.

- Capsules generally can be opened to administer powdered contents, unless the capsule has time-release properties or an enteric coating.

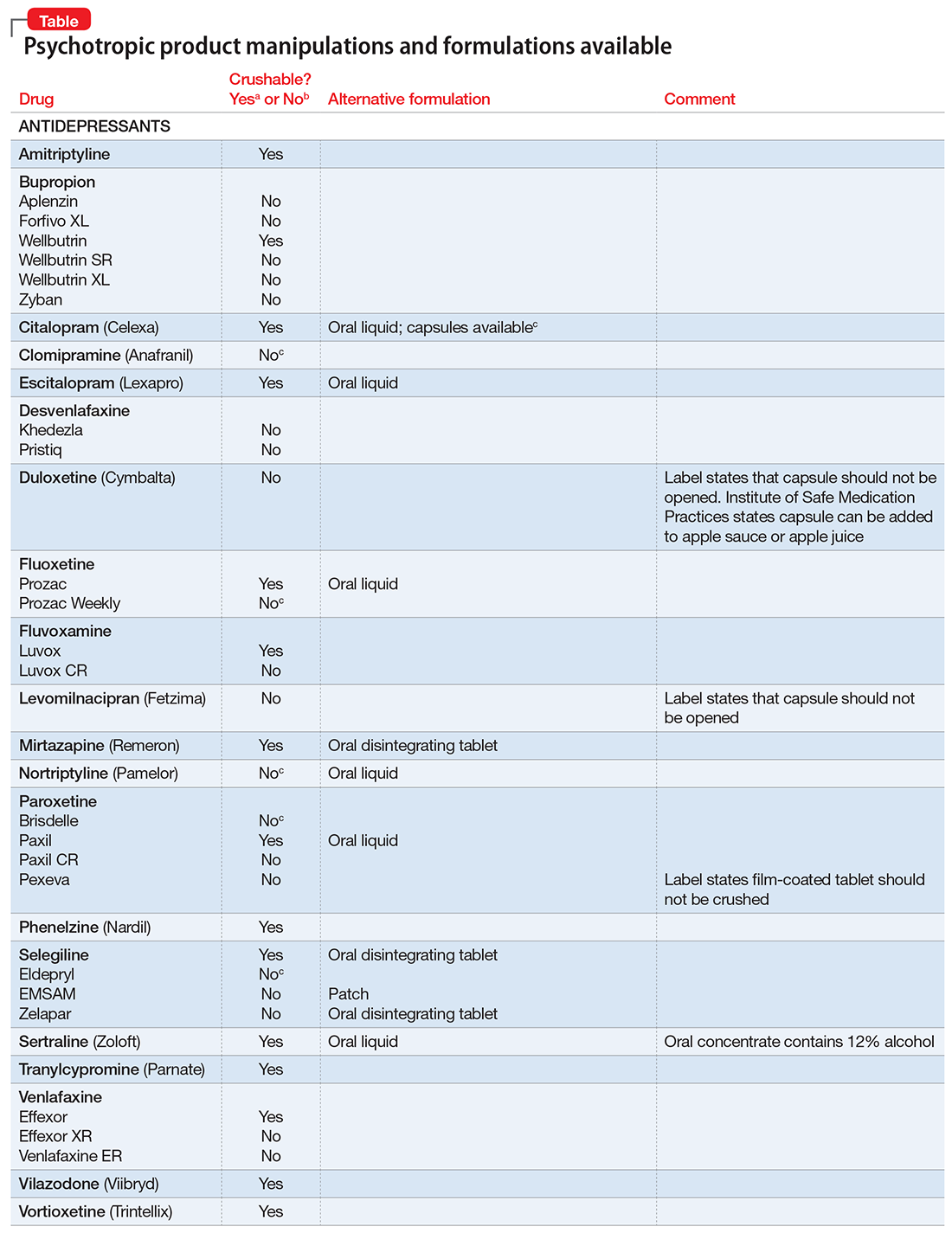

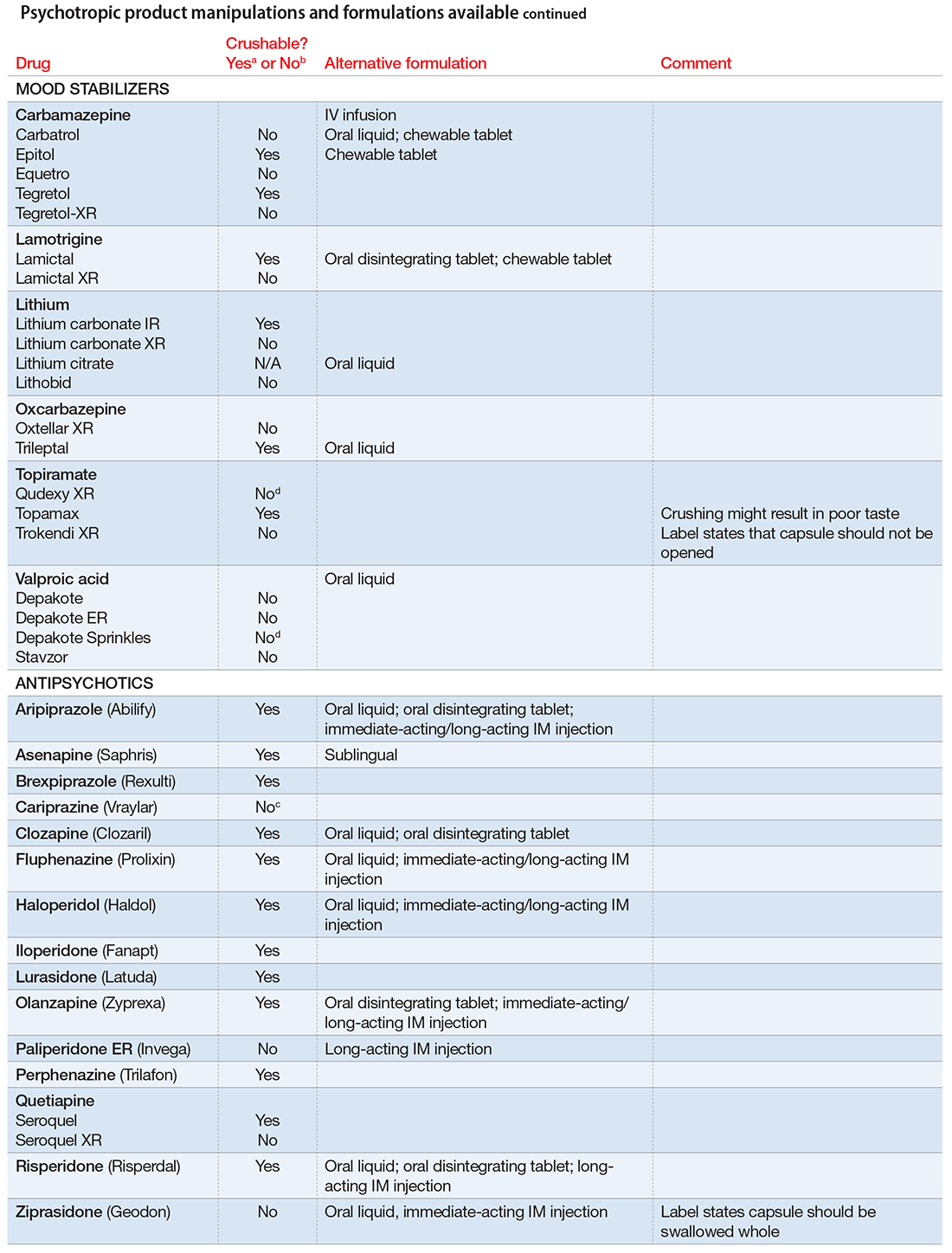

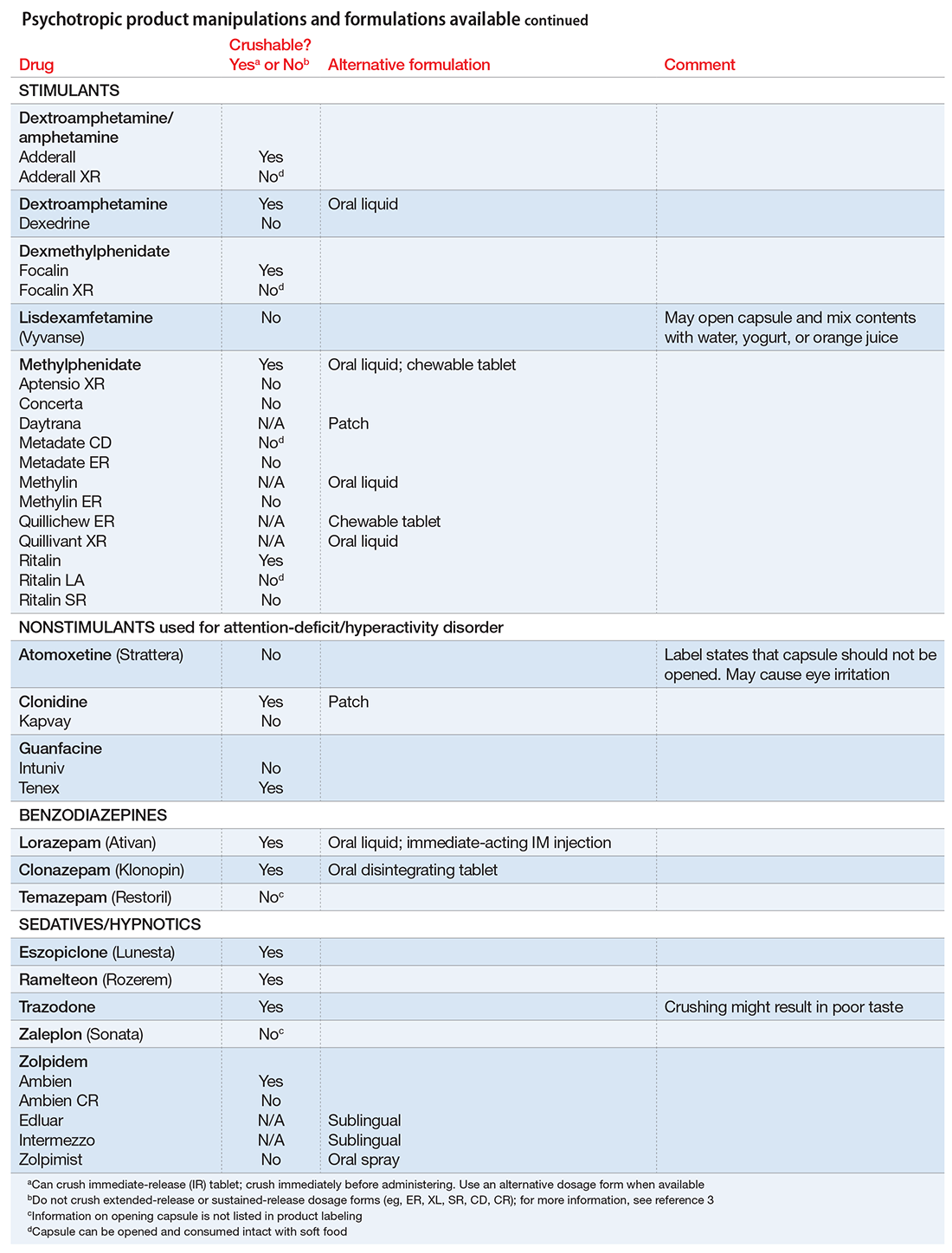

The accompanying Table, organized by drug class, indicates whether a drug can be crushed to a powdered form, which usually is mixed with food or liquid for easier intake. The Table also lists liquid and orally disintegrating forms available, and other routes, including injectable immediate and long-acting formulations. Helping patients find a medication formulation that suits their needs strengthens adherence and the therapeutic relationship.

1. Schiele JT, Quinzler R, Klimm HD, et al. Difficulties swallowing solid oral dosage forms in a general practice population: prevalence, causes, and relationship to dosage forms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4): 937-948.

2. PL Detail-Document, Meds That Should Not Be Crushed. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’sLetter. July 2012.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. http://www.ismp.org/tools/donotcrush.pdf. Updated January 2015. Accessed January 17, 2017.

Many patients experience difficulty swallowing pills, for various reasons:

- discomfort (particularly pediatric and geriatric patients)

- postsurgical need for an alternate route of enteral intake (nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, jejunostomy)

- dysphagia due to a neurologic disorder (multiple sclerosis, impaired gag reflex, dementing processes)

- odynophagia (pain upon swallowing) due to gastroesophageal reflux or a structural abnormality

- a structural abnormality of the head or neck that impairs swallowing.1

If these difficulties are not addressed, they can interfere with medication adherence. In those instances, using an alternative dosage form or manipulating an available formulation might be required.

Crushing guidelines

There are limited data on crushed-form products and their impact on efficacy. Therefore, when patients have difficulty taking pills, switching to liquid solution or orally disintegrating forms is recommended. However, most psychotropics are available only as tablets or capsules. Patients can crush their pills immediately before administration for easier intake. The following are some general guidelines for doing so:2

- Scored tablets typically can be crushed.

- Crushing sublingual and buccal tablets can alter their effectiveness.

- Crushing sustained-release medications can eliminate the sustained-release action.3

- Enteric-coated medications should not be crushed, because this can alter drug absorption.

- Capsules generally can be opened to administer powdered contents, unless the capsule has time-release properties or an enteric coating.

The accompanying Table, organized by drug class, indicates whether a drug can be crushed to a powdered form, which usually is mixed with food or liquid for easier intake. The Table also lists liquid and orally disintegrating forms available, and other routes, including injectable immediate and long-acting formulations. Helping patients find a medication formulation that suits their needs strengthens adherence and the therapeutic relationship.

Many patients experience difficulty swallowing pills, for various reasons:

- discomfort (particularly pediatric and geriatric patients)

- postsurgical need for an alternate route of enteral intake (nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, jejunostomy)

- dysphagia due to a neurologic disorder (multiple sclerosis, impaired gag reflex, dementing processes)

- odynophagia (pain upon swallowing) due to gastroesophageal reflux or a structural abnormality

- a structural abnormality of the head or neck that impairs swallowing.1

If these difficulties are not addressed, they can interfere with medication adherence. In those instances, using an alternative dosage form or manipulating an available formulation might be required.

Crushing guidelines

There are limited data on crushed-form products and their impact on efficacy. Therefore, when patients have difficulty taking pills, switching to liquid solution or orally disintegrating forms is recommended. However, most psychotropics are available only as tablets or capsules. Patients can crush their pills immediately before administration for easier intake. The following are some general guidelines for doing so:2

- Scored tablets typically can be crushed.

- Crushing sublingual and buccal tablets can alter their effectiveness.

- Crushing sustained-release medications can eliminate the sustained-release action.3

- Enteric-coated medications should not be crushed, because this can alter drug absorption.

- Capsules generally can be opened to administer powdered contents, unless the capsule has time-release properties or an enteric coating.

The accompanying Table, organized by drug class, indicates whether a drug can be crushed to a powdered form, which usually is mixed with food or liquid for easier intake. The Table also lists liquid and orally disintegrating forms available, and other routes, including injectable immediate and long-acting formulations. Helping patients find a medication formulation that suits their needs strengthens adherence and the therapeutic relationship.

1. Schiele JT, Quinzler R, Klimm HD, et al. Difficulties swallowing solid oral dosage forms in a general practice population: prevalence, causes, and relationship to dosage forms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4): 937-948.

2. PL Detail-Document, Meds That Should Not Be Crushed. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’sLetter. July 2012.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. http://www.ismp.org/tools/donotcrush.pdf. Updated January 2015. Accessed January 17, 2017.

1. Schiele JT, Quinzler R, Klimm HD, et al. Difficulties swallowing solid oral dosage forms in a general practice population: prevalence, causes, and relationship to dosage forms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4): 937-948.

2. PL Detail-Document, Meds That Should Not Be Crushed. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’sLetter. July 2012.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. http://www.ismp.org/tools/donotcrush.pdf. Updated January 2015. Accessed January 17, 2017.

REIGNITE the desire: Tackle burnout in psychiatry

Burnout among psychiatric clinicians can lead to reduced job satisfaction, poorer quality of patient care, and depression.1 Signs of burnout include a feeling of cynicism (eg, negative attitudes toward patients), overwhelming exhaustion (eg, feeling depleted), and a sense of ineffectiveness (eg, reduced productivity).1 Workplace variables and other factors that could perpetuate burnout among psychiatrists include, but are not limited to:

- too much work

- chronic staff shortages

- working with difficult patients

- inability to meet self-imposed demands

- a lack of meaningful relationships with colleagues and supervisors.1,2

The mnemonic REIGNITE provides strategies to reduce the risk of burnout.1,3

Recognize your limits. Although saying “no” may be difficult for mental health clinicians, saying “yes” too often can be detrimental. Techniques for setting limits without alienating colleagues include:

- declining tasks (“I appreciate you thinking of me to do that, but I can’t complete it right now”)

- delaying an answer (“Let me ponder what you are asking”)

- delegating tasks (“I could really use your help”)

- avoid taking on too much (“I thought that I could do that extra task, but I realize that taking on the additional assignment isn’t going to work out”).

Expand your portfolio. Developing a diverse work portfolio (eg, teaching part-time) could diminish stagnation. Adding regenerative activities (eg, outdoor activities) could be restorative.

Itemize your priorities. Ask yourself what is important to you. Is it work? If so, can work be modified so it continues to be rewarding without resulting in burnout? If it isn’t work, then what is? Money? Family? Evaluating what is important and pursuing those priorities could increase overall life satisfaction.

Go after your passions. What do you like to do aside from work? Do you paint or play a musical instrument? Pursuing hobbies and interests can revitalize your spirit.

Now. We as a profession are notorious for saying to ourselves, “I will get to it (being happy) someday.” We delay happiness until we catch up with work, save enough money, and so on. This approach is unrealistic. It is better to live in the present because there are a finite number of days to seize the day. Focus your energy in the moment.

Interact. Isolating oneself will lead to burnout. If you are in solo practice, connect with other providers or get involved in community activities. If you work with other providers, interact with them in a meaningful manner (eg, don’t complain but rather air your concerns, accept honest feedback, be open to suggestions, and seek assistance; it is acceptable to admit that you can’t do everything).

Take time off and take care of yourself. Although that seems intuitive, psychiatrists, as a group, don’t do a good job of it. Waiting until you are burned out to take a vacation is counterproductive because you will be too drained to enjoy it. Taking care of your physical and mental health is equally important.

Enjoyment in and at work. We make a difference in our patients’ lives throughthe emotional connections we develop with them. By viewing what we do as fulfilling a higher calling, we can learn to enjoy what we do rather than feeling burdened by it. Advocating for better recognition—whether financial, institutional, or social—can create opportunities for personal satisfaction.

1. Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):103-111.

2. Bressi C, Porcellana M, Gambini O, et al. Burnout among psychiatrists in Milan: a multicenter survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(7):985-988.

3. Bohnert P, O’Connell A. How to avoid burnout

Burnout among psychiatric clinicians can lead to reduced job satisfaction, poorer quality of patient care, and depression.1 Signs of burnout include a feeling of cynicism (eg, negative attitudes toward patients), overwhelming exhaustion (eg, feeling depleted), and a sense of ineffectiveness (eg, reduced productivity).1 Workplace variables and other factors that could perpetuate burnout among psychiatrists include, but are not limited to:

- too much work

- chronic staff shortages

- working with difficult patients

- inability to meet self-imposed demands

- a lack of meaningful relationships with colleagues and supervisors.1,2

The mnemonic REIGNITE provides strategies to reduce the risk of burnout.1,3

Recognize your limits. Although saying “no” may be difficult for mental health clinicians, saying “yes” too often can be detrimental. Techniques for setting limits without alienating colleagues include:

- declining tasks (“I appreciate you thinking of me to do that, but I can’t complete it right now”)

- delaying an answer (“Let me ponder what you are asking”)

- delegating tasks (“I could really use your help”)

- avoid taking on too much (“I thought that I could do that extra task, but I realize that taking on the additional assignment isn’t going to work out”).

Expand your portfolio. Developing a diverse work portfolio (eg, teaching part-time) could diminish stagnation. Adding regenerative activities (eg, outdoor activities) could be restorative.

Itemize your priorities. Ask yourself what is important to you. Is it work? If so, can work be modified so it continues to be rewarding without resulting in burnout? If it isn’t work, then what is? Money? Family? Evaluating what is important and pursuing those priorities could increase overall life satisfaction.

Go after your passions. What do you like to do aside from work? Do you paint or play a musical instrument? Pursuing hobbies and interests can revitalize your spirit.

Now. We as a profession are notorious for saying to ourselves, “I will get to it (being happy) someday.” We delay happiness until we catch up with work, save enough money, and so on. This approach is unrealistic. It is better to live in the present because there are a finite number of days to seize the day. Focus your energy in the moment.

Interact. Isolating oneself will lead to burnout. If you are in solo practice, connect with other providers or get involved in community activities. If you work with other providers, interact with them in a meaningful manner (eg, don’t complain but rather air your concerns, accept honest feedback, be open to suggestions, and seek assistance; it is acceptable to admit that you can’t do everything).

Take time off and take care of yourself. Although that seems intuitive, psychiatrists, as a group, don’t do a good job of it. Waiting until you are burned out to take a vacation is counterproductive because you will be too drained to enjoy it. Taking care of your physical and mental health is equally important.

Enjoyment in and at work. We make a difference in our patients’ lives throughthe emotional connections we develop with them. By viewing what we do as fulfilling a higher calling, we can learn to enjoy what we do rather than feeling burdened by it. Advocating for better recognition—whether financial, institutional, or social—can create opportunities for personal satisfaction.

Burnout among psychiatric clinicians can lead to reduced job satisfaction, poorer quality of patient care, and depression.1 Signs of burnout include a feeling of cynicism (eg, negative attitudes toward patients), overwhelming exhaustion (eg, feeling depleted), and a sense of ineffectiveness (eg, reduced productivity).1 Workplace variables and other factors that could perpetuate burnout among psychiatrists include, but are not limited to:

- too much work

- chronic staff shortages

- working with difficult patients

- inability to meet self-imposed demands

- a lack of meaningful relationships with colleagues and supervisors.1,2

The mnemonic REIGNITE provides strategies to reduce the risk of burnout.1,3

Recognize your limits. Although saying “no” may be difficult for mental health clinicians, saying “yes” too often can be detrimental. Techniques for setting limits without alienating colleagues include:

- declining tasks (“I appreciate you thinking of me to do that, but I can’t complete it right now”)

- delaying an answer (“Let me ponder what you are asking”)

- delegating tasks (“I could really use your help”)

- avoid taking on too much (“I thought that I could do that extra task, but I realize that taking on the additional assignment isn’t going to work out”).

Expand your portfolio. Developing a diverse work portfolio (eg, teaching part-time) could diminish stagnation. Adding regenerative activities (eg, outdoor activities) could be restorative.

Itemize your priorities. Ask yourself what is important to you. Is it work? If so, can work be modified so it continues to be rewarding without resulting in burnout? If it isn’t work, then what is? Money? Family? Evaluating what is important and pursuing those priorities could increase overall life satisfaction.

Go after your passions. What do you like to do aside from work? Do you paint or play a musical instrument? Pursuing hobbies and interests can revitalize your spirit.

Now. We as a profession are notorious for saying to ourselves, “I will get to it (being happy) someday.” We delay happiness until we catch up with work, save enough money, and so on. This approach is unrealistic. It is better to live in the present because there are a finite number of days to seize the day. Focus your energy in the moment.

Interact. Isolating oneself will lead to burnout. If you are in solo practice, connect with other providers or get involved in community activities. If you work with other providers, interact with them in a meaningful manner (eg, don’t complain but rather air your concerns, accept honest feedback, be open to suggestions, and seek assistance; it is acceptable to admit that you can’t do everything).

Take time off and take care of yourself. Although that seems intuitive, psychiatrists, as a group, don’t do a good job of it. Waiting until you are burned out to take a vacation is counterproductive because you will be too drained to enjoy it. Taking care of your physical and mental health is equally important.

Enjoyment in and at work. We make a difference in our patients’ lives throughthe emotional connections we develop with them. By viewing what we do as fulfilling a higher calling, we can learn to enjoy what we do rather than feeling burdened by it. Advocating for better recognition—whether financial, institutional, or social—can create opportunities for personal satisfaction.

1. Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):103-111.

2. Bressi C, Porcellana M, Gambini O, et al. Burnout among psychiatrists in Milan: a multicenter survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(7):985-988.

3. Bohnert P, O’Connell A. How to avoid burnout

1. Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):103-111.

2. Bressi C, Porcellana M, Gambini O, et al. Burnout among psychiatrists in Milan: a multicenter survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(7):985-988.

3. Bohnert P, O’Connell A. How to avoid burnout

When to use an anticonvulsant to treat alcohol withdrawal

Alcohol withdrawal is an uncomfortable and potentially life-threatening condition that must be treated before patients can achieve sobriety. Benzodiazepines remain the first-line treatment for alcohol withdrawal; however, these agents could:

- exacerbate agitation

- interact adversely with other medications, particularly opioids

- be unsafe for outpatients at risk of drinking again.

Off-label use of anticonvulsants could reduce these risks. In our emergency department, we routinely use these agents as monotherapy for patients discharging to outpatient detoxification or as adjunctive treatment for patients who require admission for severe withdrawal (Table1,2).

Gabapentin is safe for patients with liver disease and has few drug–drug interactions.1 Dosages of at least 1,200 mg/d seems to be comparable to lorazepam for alcohol withdrawal and could help prevent relapse after the withdrawal period.1 Many patients report that gabapentin helps them sleep. Gabapentin could cause gastrointestinal upset or slight dizziness; patients with severe renal disease might require dosage adjustments.

Carbamazepine. In a randomized double-blind trial, carbamazepine was superior to lorazepam in preventing rebound withdrawal symptoms and reducing post-treatment drinking, although both agents were effective in decreasing withdrawal symptoms.2 Avoid this agent in patients with serum liver enzymes 3 times higher than normal values

Divalproex with as-needed benzodiazepines reduces the duration of withdrawal and risk of medical complications.3 Avoid using divalproex in patients with thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, or severe liver disease.

1. Myrick H, Malcolm R, Randall PK, et al. A double-blind trial of gabapentin versus lorazepam in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(9):1582-1588.

2. Malcom R, Myrick H, Roberts J, et al. The effects of carbamazepine and lorazepam on a single versus multiple previous alcohol withdrawals in an outpatient randomized trial. J Gen Int Med. 2002;17(5):349-355.

3. Eyer F, Schreckenberg M, Adorjan K, et al. Carbamazepine and valproate as adjuncts in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(2):177-184.

Alcohol withdrawal is an uncomfortable and potentially life-threatening condition that must be treated before patients can achieve sobriety. Benzodiazepines remain the first-line treatment for alcohol withdrawal; however, these agents could:

- exacerbate agitation

- interact adversely with other medications, particularly opioids

- be unsafe for outpatients at risk of drinking again.

Off-label use of anticonvulsants could reduce these risks. In our emergency department, we routinely use these agents as monotherapy for patients discharging to outpatient detoxification or as adjunctive treatment for patients who require admission for severe withdrawal (Table1,2).

Gabapentin is safe for patients with liver disease and has few drug–drug interactions.1 Dosages of at least 1,200 mg/d seems to be comparable to lorazepam for alcohol withdrawal and could help prevent relapse after the withdrawal period.1 Many patients report that gabapentin helps them sleep. Gabapentin could cause gastrointestinal upset or slight dizziness; patients with severe renal disease might require dosage adjustments.

Carbamazepine. In a randomized double-blind trial, carbamazepine was superior to lorazepam in preventing rebound withdrawal symptoms and reducing post-treatment drinking, although both agents were effective in decreasing withdrawal symptoms.2 Avoid this agent in patients with serum liver enzymes 3 times higher than normal values

Divalproex with as-needed benzodiazepines reduces the duration of withdrawal and risk of medical complications.3 Avoid using divalproex in patients with thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, or severe liver disease.

Alcohol withdrawal is an uncomfortable and potentially life-threatening condition that must be treated before patients can achieve sobriety. Benzodiazepines remain the first-line treatment for alcohol withdrawal; however, these agents could:

- exacerbate agitation

- interact adversely with other medications, particularly opioids

- be unsafe for outpatients at risk of drinking again.

Off-label use of anticonvulsants could reduce these risks. In our emergency department, we routinely use these agents as monotherapy for patients discharging to outpatient detoxification or as adjunctive treatment for patients who require admission for severe withdrawal (Table1,2).

Gabapentin is safe for patients with liver disease and has few drug–drug interactions.1 Dosages of at least 1,200 mg/d seems to be comparable to lorazepam for alcohol withdrawal and could help prevent relapse after the withdrawal period.1 Many patients report that gabapentin helps them sleep. Gabapentin could cause gastrointestinal upset or slight dizziness; patients with severe renal disease might require dosage adjustments.

Carbamazepine. In a randomized double-blind trial, carbamazepine was superior to lorazepam in preventing rebound withdrawal symptoms and reducing post-treatment drinking, although both agents were effective in decreasing withdrawal symptoms.2 Avoid this agent in patients with serum liver enzymes 3 times higher than normal values

Divalproex with as-needed benzodiazepines reduces the duration of withdrawal and risk of medical complications.3 Avoid using divalproex in patients with thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, or severe liver disease.

1. Myrick H, Malcolm R, Randall PK, et al. A double-blind trial of gabapentin versus lorazepam in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(9):1582-1588.

2. Malcom R, Myrick H, Roberts J, et al. The effects of carbamazepine and lorazepam on a single versus multiple previous alcohol withdrawals in an outpatient randomized trial. J Gen Int Med. 2002;17(5):349-355.

3. Eyer F, Schreckenberg M, Adorjan K, et al. Carbamazepine and valproate as adjuncts in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(2):177-184.

1. Myrick H, Malcolm R, Randall PK, et al. A double-blind trial of gabapentin versus lorazepam in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(9):1582-1588.

2. Malcom R, Myrick H, Roberts J, et al. The effects of carbamazepine and lorazepam on a single versus multiple previous alcohol withdrawals in an outpatient randomized trial. J Gen Int Med. 2002;17(5):349-355.

3. Eyer F, Schreckenberg M, Adorjan K, et al. Carbamazepine and valproate as adjuncts in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(2):177-184.

Never gonna give you up: Intrusive musical imagery as compulsions

Intrusive musical imagery (IMI) is characterized by recalling pieces of music,1 usually repetitions of 15 to 30 seconds,2 without pathology of the ear or nervous system.1 Also known as earworm—ohrwurm in German—or involuntary musical imagery, bits of music can become a constant cause of distress.1

IMI is prevalent in the general population; in an internet survey >85% of respondents reported experiencing IMI at least weekly.2 IMI can be generated by:

- hearing music

- reading song lyrics

- being in contact with an environment or people who are linked to specific song, such as department stores that play holiday music.2,3

IMI also is associated with stressful situations or neurological insult.1

Any song or segment of music can be the basis of IMI. The content of IMI change over time (ie, a new song can become a source of IMI).3 The frequency of experiencing IMI is correlated to how much music a person is exposed to and the importance a person places on music.2 Most episodes are intermittent; however, continuous musical episodes are known to occur.3 Episodes of IMI with obsessive-compulsive features can be classified as musical obsessions (MO).1 MO may be part of obsessive-compulsive symptoms, including washing, checking, aggression, sexual obsessions, and religious obsessions or other obsessions.1

Diagnosing musical obsessions

No current measures are adequate to diagnose MO. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale does not distinguish MO from other intrusive auditory imagery.1

It is important to differentiate MO from:

- Musical preoccupations or recollections in which an individual repeatedly listens or recalls a particular song or part of a song, but does not have the urge to listen or recall music in an obsessive-compulsive pattern.1 These individuals do not display fear and avoidant behaviors that could be seen in patients with MO.1

- Musical hallucinations lack an input stimulus and the patient believes the music comes from an outside source and interprets it as reality. Misdiagnosing MO as a psychotic symptom is common and can result in improper treatment.1

Management

Pharmacotherapy. MO responds to the same medications used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and clomipramine.1 Cognitive-behavioral interventions could help patients address dysfunctional beliefs, without trying to suppress them.1

Distraction. Encourage patients to sing a different song that does not have obsessive quality1 or engage in a task that uses working memory.3

Exposure and response prevention therapy. Some case reports have reported efficacy in treating MO.1

1. Taylor S, McKay D, Miguel EC, et al. Musical obsessions: a comprehensive review of neglected clinical phenomena. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(6):580-589.

Intrusive musical imagery (IMI) is characterized by recalling pieces of music,1 usually repetitions of 15 to 30 seconds,2 without pathology of the ear or nervous system.1 Also known as earworm—ohrwurm in German—or involuntary musical imagery, bits of music can become a constant cause of distress.1

IMI is prevalent in the general population; in an internet survey >85% of respondents reported experiencing IMI at least weekly.2 IMI can be generated by:

- hearing music

- reading song lyrics

- being in contact with an environment or people who are linked to specific song, such as department stores that play holiday music.2,3

IMI also is associated with stressful situations or neurological insult.1

Any song or segment of music can be the basis of IMI. The content of IMI change over time (ie, a new song can become a source of IMI).3 The frequency of experiencing IMI is correlated to how much music a person is exposed to and the importance a person places on music.2 Most episodes are intermittent; however, continuous musical episodes are known to occur.3 Episodes of IMI with obsessive-compulsive features can be classified as musical obsessions (MO).1 MO may be part of obsessive-compulsive symptoms, including washing, checking, aggression, sexual obsessions, and religious obsessions or other obsessions.1

Diagnosing musical obsessions

No current measures are adequate to diagnose MO. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale does not distinguish MO from other intrusive auditory imagery.1

It is important to differentiate MO from:

- Musical preoccupations or recollections in which an individual repeatedly listens or recalls a particular song or part of a song, but does not have the urge to listen or recall music in an obsessive-compulsive pattern.1 These individuals do not display fear and avoidant behaviors that could be seen in patients with MO.1

- Musical hallucinations lack an input stimulus and the patient believes the music comes from an outside source and interprets it as reality. Misdiagnosing MO as a psychotic symptom is common and can result in improper treatment.1

Management

Pharmacotherapy. MO responds to the same medications used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and clomipramine.1 Cognitive-behavioral interventions could help patients address dysfunctional beliefs, without trying to suppress them.1

Distraction. Encourage patients to sing a different song that does not have obsessive quality1 or engage in a task that uses working memory.3

Exposure and response prevention therapy. Some case reports have reported efficacy in treating MO.1

Intrusive musical imagery (IMI) is characterized by recalling pieces of music,1 usually repetitions of 15 to 30 seconds,2 without pathology of the ear or nervous system.1 Also known as earworm—ohrwurm in German—or involuntary musical imagery, bits of music can become a constant cause of distress.1

IMI is prevalent in the general population; in an internet survey >85% of respondents reported experiencing IMI at least weekly.2 IMI can be generated by:

- hearing music

- reading song lyrics

- being in contact with an environment or people who are linked to specific song, such as department stores that play holiday music.2,3

IMI also is associated with stressful situations or neurological insult.1

Any song or segment of music can be the basis of IMI. The content of IMI change over time (ie, a new song can become a source of IMI).3 The frequency of experiencing IMI is correlated to how much music a person is exposed to and the importance a person places on music.2 Most episodes are intermittent; however, continuous musical episodes are known to occur.3 Episodes of IMI with obsessive-compulsive features can be classified as musical obsessions (MO).1 MO may be part of obsessive-compulsive symptoms, including washing, checking, aggression, sexual obsessions, and religious obsessions or other obsessions.1

Diagnosing musical obsessions

No current measures are adequate to diagnose MO. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale does not distinguish MO from other intrusive auditory imagery.1

It is important to differentiate MO from:

- Musical preoccupations or recollections in which an individual repeatedly listens or recalls a particular song or part of a song, but does not have the urge to listen or recall music in an obsessive-compulsive pattern.1 These individuals do not display fear and avoidant behaviors that could be seen in patients with MO.1

- Musical hallucinations lack an input stimulus and the patient believes the music comes from an outside source and interprets it as reality. Misdiagnosing MO as a psychotic symptom is common and can result in improper treatment.1

Management

Pharmacotherapy. MO responds to the same medications used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and clomipramine.1 Cognitive-behavioral interventions could help patients address dysfunctional beliefs, without trying to suppress them.1

Distraction. Encourage patients to sing a different song that does not have obsessive quality1 or engage in a task that uses working memory.3

Exposure and response prevention therapy. Some case reports have reported efficacy in treating MO.1

1. Taylor S, McKay D, Miguel EC, et al. Musical obsessions: a comprehensive review of neglected clinical phenomena. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(6):580-589.

1. Taylor S, McKay D, Miguel EC, et al. Musical obsessions: a comprehensive review of neglected clinical phenomena. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(6):580-589.

Assess and treat catatonia using this systematic approach

Catatonia is a neuropsychiatric condition with varying presentations that involve behavioral, motoric, cognitive, affective, and, occasionally, autonomic disturbances. Underlying causes of the syndrome include:

- mood disorders

- psychotic disorders

- neurologic disease

- general medical conditions

- metabolic abnormalities

- drug intoxication or withdrawal.

- deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- pressure sores or ulcers

- muscle contractures

- nutritional deficiencies and dehydration from decreased oral intake.1

Prompt recognition, assessment, and treatment are vital.

We recommend the following systematic approach to evaluate and treat catatonia (Table).

Assess

Appropriate assessment of catatonia requires recognition of the array of potential underlying causes of the syndrome.

Obtain a complete history, including:

- recent changes in behavior

- past psychiatric illness and hospitalization

- past or current neurologic or medical disease

- prescription and illicit drug use.

Collateral informants, such as family members and caregivers, could provide valuable information. This history could reveal causative factors and identify appropriate targets for treatment.

Physical and mental status examinations can help characterize the type and severity of motoric and behavioral symptoms, such as rigidity, waxy flexibility, negativism, automatic obedience, ambitendency, and perseveration. Monitoring vital signs is crucial because of the risk of medical complications and malignant catatonia, which can be lethal if not treated.

Laboratory testing and imaging might be indicated to rule out medical causes, such as infection, metabolic disturbances, drug intoxication and withdrawal, and acute neurologic etiologies.

Rate

Identify and rate symptom severity. After determining that a patient has catatonia, consider using a standardized instrument, such as the Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS),2 to assess the patient’s type of symptoms and degree of impairment. Scores obtained on such instruments can be tracked as the patient receives treatment. Although the BFCRS is imperfect because of ambiguous symptom descriptions and because symptoms can remain after effective treatment, it is the most widely researched catatonia scale.

Treat and monitor

Although there are no published data from large-scale, randomized, controlled trials, clinical experience shows that the mainstays of treatment still are benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). A benzodiazepine challenge of IV lorazepam, 2 mg, can lead to rapid, substantial symptomatic relief with relatively low risk of harm. An estimated 50% to 70% of patients with catatonia respond within 5 days to IV lorazepam, 2 mg, every 3 to 8 hours.3

When patients do not respond to benzodiazepines, consider ECT. For patients with medical, neurologic, and toxic metabolic causes of catatonia, treat the underlying disturbance first.

1. Clinebell K, Azzam PN, Gopalan P, et al. Guidelines for preventing common medical complications of catatonia: case report and literature review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(6):644-651.

2. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia. I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):129-136.

3. Fink M. Catatonia: syndrome or schizophrenia subtype? Recognition and treatment. J Neural Transmission (Vienna). 2001;108(6):637-644.

Catatonia is a neuropsychiatric condition with varying presentations that involve behavioral, motoric, cognitive, affective, and, occasionally, autonomic disturbances. Underlying causes of the syndrome include:

- mood disorders

- psychotic disorders

- neurologic disease

- general medical conditions

- metabolic abnormalities

- drug intoxication or withdrawal.

- deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- pressure sores or ulcers

- muscle contractures

- nutritional deficiencies and dehydration from decreased oral intake.1

Prompt recognition, assessment, and treatment are vital.

We recommend the following systematic approach to evaluate and treat catatonia (Table).

Assess

Appropriate assessment of catatonia requires recognition of the array of potential underlying causes of the syndrome.

Obtain a complete history, including:

- recent changes in behavior

- past psychiatric illness and hospitalization

- past or current neurologic or medical disease

- prescription and illicit drug use.

Collateral informants, such as family members and caregivers, could provide valuable information. This history could reveal causative factors and identify appropriate targets for treatment.

Physical and mental status examinations can help characterize the type and severity of motoric and behavioral symptoms, such as rigidity, waxy flexibility, negativism, automatic obedience, ambitendency, and perseveration. Monitoring vital signs is crucial because of the risk of medical complications and malignant catatonia, which can be lethal if not treated.

Laboratory testing and imaging might be indicated to rule out medical causes, such as infection, metabolic disturbances, drug intoxication and withdrawal, and acute neurologic etiologies.

Rate

Identify and rate symptom severity. After determining that a patient has catatonia, consider using a standardized instrument, such as the Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS),2 to assess the patient’s type of symptoms and degree of impairment. Scores obtained on such instruments can be tracked as the patient receives treatment. Although the BFCRS is imperfect because of ambiguous symptom descriptions and because symptoms can remain after effective treatment, it is the most widely researched catatonia scale.

Treat and monitor

Although there are no published data from large-scale, randomized, controlled trials, clinical experience shows that the mainstays of treatment still are benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). A benzodiazepine challenge of IV lorazepam, 2 mg, can lead to rapid, substantial symptomatic relief with relatively low risk of harm. An estimated 50% to 70% of patients with catatonia respond within 5 days to IV lorazepam, 2 mg, every 3 to 8 hours.3

When patients do not respond to benzodiazepines, consider ECT. For patients with medical, neurologic, and toxic metabolic causes of catatonia, treat the underlying disturbance first.

Catatonia is a neuropsychiatric condition with varying presentations that involve behavioral, motoric, cognitive, affective, and, occasionally, autonomic disturbances. Underlying causes of the syndrome include:

- mood disorders

- psychotic disorders

- neurologic disease

- general medical conditions

- metabolic abnormalities

- drug intoxication or withdrawal.

- deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- pressure sores or ulcers

- muscle contractures

- nutritional deficiencies and dehydration from decreased oral intake.1

Prompt recognition, assessment, and treatment are vital.

We recommend the following systematic approach to evaluate and treat catatonia (Table).

Assess

Appropriate assessment of catatonia requires recognition of the array of potential underlying causes of the syndrome.

Obtain a complete history, including:

- recent changes in behavior

- past psychiatric illness and hospitalization

- past or current neurologic or medical disease

- prescription and illicit drug use.

Collateral informants, such as family members and caregivers, could provide valuable information. This history could reveal causative factors and identify appropriate targets for treatment.

Physical and mental status examinations can help characterize the type and severity of motoric and behavioral symptoms, such as rigidity, waxy flexibility, negativism, automatic obedience, ambitendency, and perseveration. Monitoring vital signs is crucial because of the risk of medical complications and malignant catatonia, which can be lethal if not treated.

Laboratory testing and imaging might be indicated to rule out medical causes, such as infection, metabolic disturbances, drug intoxication and withdrawal, and acute neurologic etiologies.

Rate

Identify and rate symptom severity. After determining that a patient has catatonia, consider using a standardized instrument, such as the Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS),2 to assess the patient’s type of symptoms and degree of impairment. Scores obtained on such instruments can be tracked as the patient receives treatment. Although the BFCRS is imperfect because of ambiguous symptom descriptions and because symptoms can remain after effective treatment, it is the most widely researched catatonia scale.

Treat and monitor

Although there are no published data from large-scale, randomized, controlled trials, clinical experience shows that the mainstays of treatment still are benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). A benzodiazepine challenge of IV lorazepam, 2 mg, can lead to rapid, substantial symptomatic relief with relatively low risk of harm. An estimated 50% to 70% of patients with catatonia respond within 5 days to IV lorazepam, 2 mg, every 3 to 8 hours.3

When patients do not respond to benzodiazepines, consider ECT. For patients with medical, neurologic, and toxic metabolic causes of catatonia, treat the underlying disturbance first.

1. Clinebell K, Azzam PN, Gopalan P, et al. Guidelines for preventing common medical complications of catatonia: case report and literature review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(6):644-651.

2. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia. I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):129-136.

3. Fink M. Catatonia: syndrome or schizophrenia subtype? Recognition and treatment. J Neural Transmission (Vienna). 2001;108(6):637-644.

1. Clinebell K, Azzam PN, Gopalan P, et al. Guidelines for preventing common medical complications of catatonia: case report and literature review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(6):644-651.

2. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia. I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):129-136.

3. Fink M. Catatonia: syndrome or schizophrenia subtype? Recognition and treatment. J Neural Transmission (Vienna). 2001;108(6):637-644.

Consider Rx metformin to prevent metabolic syndrome

Many atypical antipsychotics, particularly clozapine and olanzapine, are associated with weight gain, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular disease, which are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in persons with severe mental illness.1

Clinicians should take measures to prevent T2DM and weight gain in individuals taking antipsychotics before these conditions develop. Metformin re-sensitizes the body to insulin and is a first-line treatment for T2DM. Adding metformin when patients start metabolically high-risk antipsychotics or shortly after they begin gaining weight is an evidence-based strategy to prevent metabolic syndrome.

Evaluate the evidence

In randomized controlled trials, metformin was associated with modest weight loss and improvement in metabolic parameters (eg, fasting blood glucose, serum triglycerides, and total cholesterol) in patients with schizophrenia receiving antipsychotics.1,2 Metformin is effective for preventing metabolic syndrome and as a treatment intervention; therefore, it may prove most beneficial early in treatment before weight gain or insulin resistance develop.

Importantly, weight gain and metabolic syndrome are risk factors for cardiovascular disease, but the number needed to treat for metformin to prevent cardiovascular outcomes, such as myocardial infarction, is not known. Also, metformin is not FDA-approved for this indication. Clinicians should discuss with the patient the risks and benefits of prophylactic metformin, and consider his (her) treatment preferences.

Tolerability and adverse effects

Metformin generally is well-tolerated. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including nausea and vomiting (14%) and diarrhea (7%), are the most common adverse effects.2 Lactic acidosis is rare and is associated with alcohol use disorders and impaired renal, hepatic, or cardiopulmonary function.3 Because metformin is excreted renally, toxicity could occur in patients with impaired renal function.

Before initiating prophylactic metformin, confirm that the patient does not have T2DM (eg, hemoglobin A1c <6.5%). A thorough medical history, including alcohol use and kidney and liver function tests, are needed to reduce the risk of lactic acidosis.3

Dosing

Although metformin has been studied at many dosages,2 we recommend gradual titration to 1,000 mg, twice daily, taken with meals to reduce the risk of GI effects.

Additional interventions

Metformin alone is not sufficient to mitigate metabolic risk. Providers should address dietary interventions, exercise, and smoking cessation at each visit, and communicate actively with other providers to create a comprehensive treatment plan.

1. Jarskog LF, Hamer RF, Catellier DJ, et al; METS Investigators. Metformin for weight loss and metabolic control in overweight patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1032-1040.

2. Zheng W, Li X-B, Tang Y-L, et al. Metformin for weight gain and metabolic abnormalities associated with antipsychotic treatment: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(5):499-509.

3. Wang M, Tong J-H, Zhu G, et al. Metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):54-57.

Many atypical antipsychotics, particularly clozapine and olanzapine, are associated with weight gain, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular disease, which are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in persons with severe mental illness.1

Clinicians should take measures to prevent T2DM and weight gain in individuals taking antipsychotics before these conditions develop. Metformin re-sensitizes the body to insulin and is a first-line treatment for T2DM. Adding metformin when patients start metabolically high-risk antipsychotics or shortly after they begin gaining weight is an evidence-based strategy to prevent metabolic syndrome.

Evaluate the evidence

In randomized controlled trials, metformin was associated with modest weight loss and improvement in metabolic parameters (eg, fasting blood glucose, serum triglycerides, and total cholesterol) in patients with schizophrenia receiving antipsychotics.1,2 Metformin is effective for preventing metabolic syndrome and as a treatment intervention; therefore, it may prove most beneficial early in treatment before weight gain or insulin resistance develop.

Importantly, weight gain and metabolic syndrome are risk factors for cardiovascular disease, but the number needed to treat for metformin to prevent cardiovascular outcomes, such as myocardial infarction, is not known. Also, metformin is not FDA-approved for this indication. Clinicians should discuss with the patient the risks and benefits of prophylactic metformin, and consider his (her) treatment preferences.

Tolerability and adverse effects

Metformin generally is well-tolerated. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including nausea and vomiting (14%) and diarrhea (7%), are the most common adverse effects.2 Lactic acidosis is rare and is associated with alcohol use disorders and impaired renal, hepatic, or cardiopulmonary function.3 Because metformin is excreted renally, toxicity could occur in patients with impaired renal function.

Before initiating prophylactic metformin, confirm that the patient does not have T2DM (eg, hemoglobin A1c <6.5%). A thorough medical history, including alcohol use and kidney and liver function tests, are needed to reduce the risk of lactic acidosis.3

Dosing

Although metformin has been studied at many dosages,2 we recommend gradual titration to 1,000 mg, twice daily, taken with meals to reduce the risk of GI effects.

Additional interventions

Metformin alone is not sufficient to mitigate metabolic risk. Providers should address dietary interventions, exercise, and smoking cessation at each visit, and communicate actively with other providers to create a comprehensive treatment plan.

Many atypical antipsychotics, particularly clozapine and olanzapine, are associated with weight gain, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular disease, which are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in persons with severe mental illness.1

Clinicians should take measures to prevent T2DM and weight gain in individuals taking antipsychotics before these conditions develop. Metformin re-sensitizes the body to insulin and is a first-line treatment for T2DM. Adding metformin when patients start metabolically high-risk antipsychotics or shortly after they begin gaining weight is an evidence-based strategy to prevent metabolic syndrome.

Evaluate the evidence

In randomized controlled trials, metformin was associated with modest weight loss and improvement in metabolic parameters (eg, fasting blood glucose, serum triglycerides, and total cholesterol) in patients with schizophrenia receiving antipsychotics.1,2 Metformin is effective for preventing metabolic syndrome and as a treatment intervention; therefore, it may prove most beneficial early in treatment before weight gain or insulin resistance develop.

Importantly, weight gain and metabolic syndrome are risk factors for cardiovascular disease, but the number needed to treat for metformin to prevent cardiovascular outcomes, such as myocardial infarction, is not known. Also, metformin is not FDA-approved for this indication. Clinicians should discuss with the patient the risks and benefits of prophylactic metformin, and consider his (her) treatment preferences.

Tolerability and adverse effects

Metformin generally is well-tolerated. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including nausea and vomiting (14%) and diarrhea (7%), are the most common adverse effects.2 Lactic acidosis is rare and is associated with alcohol use disorders and impaired renal, hepatic, or cardiopulmonary function.3 Because metformin is excreted renally, toxicity could occur in patients with impaired renal function.

Before initiating prophylactic metformin, confirm that the patient does not have T2DM (eg, hemoglobin A1c <6.5%). A thorough medical history, including alcohol use and kidney and liver function tests, are needed to reduce the risk of lactic acidosis.3

Dosing

Although metformin has been studied at many dosages,2 we recommend gradual titration to 1,000 mg, twice daily, taken with meals to reduce the risk of GI effects.

Additional interventions

Metformin alone is not sufficient to mitigate metabolic risk. Providers should address dietary interventions, exercise, and smoking cessation at each visit, and communicate actively with other providers to create a comprehensive treatment plan.

1. Jarskog LF, Hamer RF, Catellier DJ, et al; METS Investigators. Metformin for weight loss and metabolic control in overweight patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1032-1040.

2. Zheng W, Li X-B, Tang Y-L, et al. Metformin for weight gain and metabolic abnormalities associated with antipsychotic treatment: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(5):499-509.

3. Wang M, Tong J-H, Zhu G, et al. Metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):54-57.

1. Jarskog LF, Hamer RF, Catellier DJ, et al; METS Investigators. Metformin for weight loss and metabolic control in overweight patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1032-1040.

2. Zheng W, Li X-B, Tang Y-L, et al. Metformin for weight gain and metabolic abnormalities associated with antipsychotic treatment: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(5):499-509.

3. Wang M, Tong J-H, Zhu G, et al. Metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):54-57.

How you can aid your patient’s claim for long-term disability

Neuropsychiatric disorders are associated with high rates of impaired work capacity despite the best efforts of treating clinicians to help their patients stay employed or resume working after symptoms improve.1

In the past, a note from the psychiatrist stating that the patient was unable to work because of a neuropsychiatric condition often was sufficient to approve a disability claim. This is no longer the case in today’s more restrictive climate, and what constitutes prima facie evidence of a patient’s inability to sustain competitive employment secondary to neuropsychiatric illness has significantly changed.

The following practices can help facilitate approval of your patient’s disability claim.

Document as you go. Progress notes should include the type, frequency, context, duration, and severity of symptoms supporting ≥1 psychiatric diagnoses which prevent your patient from holding a job. It also is important to document the parameters of treatment and the patient’s response, including compliance with treatment recommendations. Preferably, progress notes should include quantitative ratings over time that pertain to everyday functioning, highlighting how your patient is coping with the psychosocial, cognitive, and executive functioning demands of his (her) job.

When documented over time, ratings based on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale or a comparable scale are useful in quantifying the nature and degree of impaired functioning related to work capacity. Consider administering rating scales at periodic intervals to show changes over time. When feasible, scales should be based on a patient’s and informant’s report of symptomatic status and everyday functioning, and could include use of instruments such as the World Health Organization’s Disability Assessment Schedule.2,3

Include documentation specific to work capacity. Disability claims often are denied, in part, because the treating psychiatrist’s judgment regarding work capacity seems to “come out of the blue,” appears premature, or lacks discussion of the functional implications of the patient’s clinical status in regards to recent or current job expectations. Therefore, progress notes should include reference to long-standing, emerging, or worsening behaviors or symptoms that have clear implications for your patient’s ability to work.

Outline the functional implications of the patient’s preserved and impaired abilities and skills as they relate to work capacity, vocational history, and recent or current job situation. For example, work requirements that are highly dependent on interaction with the public, supervisors, or coworkers would be significantly affected by recurrent or persistent psychosis, even if the patient adheres to treatment and symptoms are relatively mild. Problems with working memory or anterograde memory could impair work that routinely involves learning and retention of new instructions and procedures.

Provide psychoeducation and support. Educate your patient and their family about the disability claims process, including the high rate that claims are initially denied. Consider retaining an advocate—clinical case manager, family member, or non-family third party—to assist your patient in navigating the disability application process, such as help completing paperwork, setting up appointments, and providing transportation.

Remain responsive to inquiries from disability examiners. Return forms and phone calls from disability examiners, psychiatrists, and other health care professionals reviewing your patient’s claim for long-term disability in a timely manner. Failure to do so can be used to support denial of the claim.

Consider referral for consultations and diagnostics to support the claim of impaired work capacity. Depending on the nature of the case, this could involve additional medical workup (including neuroimaging), a consultation from a vocational rehabilitation specialist, or referral for psychological or neuropsychological testing.

Psychometric assessment is becoming the preferred method for garnering support for impaired work capacity caused by neuropsychiatric factors. Findings from psychometric assessment hold up to scrutiny better if the evaluation includes symptom validity testing to rule out factitious disorder, malingering, or somatization, and results from self-report and informant-based measures of adaptive behavior and functioning.4

1. Gold LH, Shuman DW. Evaluating mental health disability in the workplace: models, process and analysis. New York, NY: Springer; 2009.

2. Traxler J. Mental health disability: a resident’s perspective of problems and solutions. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/residents-corner/mental-health-disability-residents-perspective-problems-and-solutions. Published November 26, 2014. Accessed August 31, 2016.

3. Zimmerman M. The importance of measuring outcomes in clinical practice. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/uspc2014/importance-measuring-outcomes-clinical-practice. Published October 1, 2014. Accessed August 31, 2016.

4. Schwarz L, Roskos PT, Grossberg GT. Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):34-39.

Neuropsychiatric disorders are associated with high rates of impaired work capacity despite the best efforts of treating clinicians to help their patients stay employed or resume working after symptoms improve.1

In the past, a note from the psychiatrist stating that the patient was unable to work because of a neuropsychiatric condition often was sufficient to approve a disability claim. This is no longer the case in today’s more restrictive climate, and what constitutes prima facie evidence of a patient’s inability to sustain competitive employment secondary to neuropsychiatric illness has significantly changed.

The following practices can help facilitate approval of your patient’s disability claim.

Document as you go. Progress notes should include the type, frequency, context, duration, and severity of symptoms supporting ≥1 psychiatric diagnoses which prevent your patient from holding a job. It also is important to document the parameters of treatment and the patient’s response, including compliance with treatment recommendations. Preferably, progress notes should include quantitative ratings over time that pertain to everyday functioning, highlighting how your patient is coping with the psychosocial, cognitive, and executive functioning demands of his (her) job.

When documented over time, ratings based on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale or a comparable scale are useful in quantifying the nature and degree of impaired functioning related to work capacity. Consider administering rating scales at periodic intervals to show changes over time. When feasible, scales should be based on a patient’s and informant’s report of symptomatic status and everyday functioning, and could include use of instruments such as the World Health Organization’s Disability Assessment Schedule.2,3

Include documentation specific to work capacity. Disability claims often are denied, in part, because the treating psychiatrist’s judgment regarding work capacity seems to “come out of the blue,” appears premature, or lacks discussion of the functional implications of the patient’s clinical status in regards to recent or current job expectations. Therefore, progress notes should include reference to long-standing, emerging, or worsening behaviors or symptoms that have clear implications for your patient’s ability to work.

Outline the functional implications of the patient’s preserved and impaired abilities and skills as they relate to work capacity, vocational history, and recent or current job situation. For example, work requirements that are highly dependent on interaction with the public, supervisors, or coworkers would be significantly affected by recurrent or persistent psychosis, even if the patient adheres to treatment and symptoms are relatively mild. Problems with working memory or anterograde memory could impair work that routinely involves learning and retention of new instructions and procedures.

Provide psychoeducation and support. Educate your patient and their family about the disability claims process, including the high rate that claims are initially denied. Consider retaining an advocate—clinical case manager, family member, or non-family third party—to assist your patient in navigating the disability application process, such as help completing paperwork, setting up appointments, and providing transportation.

Remain responsive to inquiries from disability examiners. Return forms and phone calls from disability examiners, psychiatrists, and other health care professionals reviewing your patient’s claim for long-term disability in a timely manner. Failure to do so can be used to support denial of the claim.

Consider referral for consultations and diagnostics to support the claim of impaired work capacity. Depending on the nature of the case, this could involve additional medical workup (including neuroimaging), a consultation from a vocational rehabilitation specialist, or referral for psychological or neuropsychological testing.

Psychometric assessment is becoming the preferred method for garnering support for impaired work capacity caused by neuropsychiatric factors. Findings from psychometric assessment hold up to scrutiny better if the evaluation includes symptom validity testing to rule out factitious disorder, malingering, or somatization, and results from self-report and informant-based measures of adaptive behavior and functioning.4

Neuropsychiatric disorders are associated with high rates of impaired work capacity despite the best efforts of treating clinicians to help their patients stay employed or resume working after symptoms improve.1

In the past, a note from the psychiatrist stating that the patient was unable to work because of a neuropsychiatric condition often was sufficient to approve a disability claim. This is no longer the case in today’s more restrictive climate, and what constitutes prima facie evidence of a patient’s inability to sustain competitive employment secondary to neuropsychiatric illness has significantly changed.

The following practices can help facilitate approval of your patient’s disability claim.

Document as you go. Progress notes should include the type, frequency, context, duration, and severity of symptoms supporting ≥1 psychiatric diagnoses which prevent your patient from holding a job. It also is important to document the parameters of treatment and the patient’s response, including compliance with treatment recommendations. Preferably, progress notes should include quantitative ratings over time that pertain to everyday functioning, highlighting how your patient is coping with the psychosocial, cognitive, and executive functioning demands of his (her) job.

When documented over time, ratings based on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale or a comparable scale are useful in quantifying the nature and degree of impaired functioning related to work capacity. Consider administering rating scales at periodic intervals to show changes over time. When feasible, scales should be based on a patient’s and informant’s report of symptomatic status and everyday functioning, and could include use of instruments such as the World Health Organization’s Disability Assessment Schedule.2,3

Include documentation specific to work capacity. Disability claims often are denied, in part, because the treating psychiatrist’s judgment regarding work capacity seems to “come out of the blue,” appears premature, or lacks discussion of the functional implications of the patient’s clinical status in regards to recent or current job expectations. Therefore, progress notes should include reference to long-standing, emerging, or worsening behaviors or symptoms that have clear implications for your patient’s ability to work.

Outline the functional implications of the patient’s preserved and impaired abilities and skills as they relate to work capacity, vocational history, and recent or current job situation. For example, work requirements that are highly dependent on interaction with the public, supervisors, or coworkers would be significantly affected by recurrent or persistent psychosis, even if the patient adheres to treatment and symptoms are relatively mild. Problems with working memory or anterograde memory could impair work that routinely involves learning and retention of new instructions and procedures.

Provide psychoeducation and support. Educate your patient and their family about the disability claims process, including the high rate that claims are initially denied. Consider retaining an advocate—clinical case manager, family member, or non-family third party—to assist your patient in navigating the disability application process, such as help completing paperwork, setting up appointments, and providing transportation.

Remain responsive to inquiries from disability examiners. Return forms and phone calls from disability examiners, psychiatrists, and other health care professionals reviewing your patient’s claim for long-term disability in a timely manner. Failure to do so can be used to support denial of the claim.

Consider referral for consultations and diagnostics to support the claim of impaired work capacity. Depending on the nature of the case, this could involve additional medical workup (including neuroimaging), a consultation from a vocational rehabilitation specialist, or referral for psychological or neuropsychological testing.

Psychometric assessment is becoming the preferred method for garnering support for impaired work capacity caused by neuropsychiatric factors. Findings from psychometric assessment hold up to scrutiny better if the evaluation includes symptom validity testing to rule out factitious disorder, malingering, or somatization, and results from self-report and informant-based measures of adaptive behavior and functioning.4

1. Gold LH, Shuman DW. Evaluating mental health disability in the workplace: models, process and analysis. New York, NY: Springer; 2009.

2. Traxler J. Mental health disability: a resident’s perspective of problems and solutions. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/residents-corner/mental-health-disability-residents-perspective-problems-and-solutions. Published November 26, 2014. Accessed August 31, 2016.

3. Zimmerman M. The importance of measuring outcomes in clinical practice. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/uspc2014/importance-measuring-outcomes-clinical-practice. Published October 1, 2014. Accessed August 31, 2016.

4. Schwarz L, Roskos PT, Grossberg GT. Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):34-39.

1. Gold LH, Shuman DW. Evaluating mental health disability in the workplace: models, process and analysis. New York, NY: Springer; 2009.

2. Traxler J. Mental health disability: a resident’s perspective of problems and solutions. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/residents-corner/mental-health-disability-residents-perspective-problems-and-solutions. Published November 26, 2014. Accessed August 31, 2016.

3. Zimmerman M. The importance of measuring outcomes in clinical practice. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/uspc2014/importance-measuring-outcomes-clinical-practice. Published October 1, 2014. Accessed August 31, 2016.

4. Schwarz L, Roskos PT, Grossberg GT. Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):34-39.

Where do you draw the line? Caveats for after-hours call coverage

Handling patient emergencies is one of the most challenging parts of clinical care. Not only does the provider have to consider the best care for the patient, he (she) must think through medicolegal considerations, as well as what systems are sustainable in a practice, and then develop a plan that addresses all those interests. Being on-call for emergencies in a solo private practice can be especially complex, because the provider is always, and solely, responsible for handling or redirecting these calls, which is one reason some physicians choose to be part of a group practice or be an employee.

First, let’s define a few different types of “emergencies” that you might encounter:

- A genuine life or death situation. A patient calls during planning, or after attempting, suicide.

- An urgent matter. A patient has run out of medication or she (he) is having discontinuation symptoms or adverse effects. Although there is no imminent danger, the patient may be experiencing significant discomfort.

- A matter of high anxiety. The patient is experiencing situations that provoke high affect, and she needs attention at that moment to lessen the burden.

Of course, you might not know the true extent of the emergency until you talk to the patient, but being able to delineate different procedures for patients based on the types of emergency situations could streamline your workflow.

With this foundation in place, let’s discuss the most common practice policies for dealing with these emergencies.

Instructing patients to call 911 or go to the emergency room (ER)

The pros.

- Meets minimum standards without any additional work.

- Reinforces work-life boundaries.

- Makes private practice tolerable.

The cons.

- Patients might not feel properly cared for.

- The patient might not want to call 911 in some situations (eg, suicidality).

- You might not know if your patient went to the ER unless hospital staff or the patient contacts you afterwards.

Using an answering service

The pros.

- Patients feel reassured that they can get your attention after hours and get a call back from you.

- Patients are familiar with this practice because it is widely used in the medical field.

- Operators are trained to screen for emergencies and can be given a script of questions to ask, and given clear guidelines so they know whether to contact you immediately.

- Establishes a healthy boundary between work and personal life.

The cons.

- Cost.

- Patients still might be frustrated if they can’t directly connect with you.

- Requires training and trusting the answering service staff.

Giving your home or cell number to patients

The pros.

- Patients might feel cared for and reassured that they can reach you directly at any time, which may, itself, be calming and reduce their need to contact you.

- Providers can maintain complete control over their practice at all times.

- Providers can market the practice as a “concierge” service.

- You can give your personal phone number to certain patients at certain times, rather than making it a practice-wide policy.

The cons.

- Providers may feel like they are working all the time. What if you go out of the country, or find yourself in a cell phone dead zone? You’ll need to have a colleague cover for you or refer patients to 911 or the ER.

- Some patients could abuse the privilege.

- Boundaries between work and personal life can crumble.

- Being available 24/7 over a 30-year career could feel onerous.

Be sure to discuss your policies with your patient at the first visit. Choosing the best policies for your practice involves providing good patient care, meeting or exceeding the standard of care, and finding the right fit for you.

Handling patient emergencies is one of the most challenging parts of clinical care. Not only does the provider have to consider the best care for the patient, he (she) must think through medicolegal considerations, as well as what systems are sustainable in a practice, and then develop a plan that addresses all those interests. Being on-call for emergencies in a solo private practice can be especially complex, because the provider is always, and solely, responsible for handling or redirecting these calls, which is one reason some physicians choose to be part of a group practice or be an employee.

First, let’s define a few different types of “emergencies” that you might encounter:

- A genuine life or death situation. A patient calls during planning, or after attempting, suicide.

- An urgent matter. A patient has run out of medication or she (he) is having discontinuation symptoms or adverse effects. Although there is no imminent danger, the patient may be experiencing significant discomfort.

- A matter of high anxiety. The patient is experiencing situations that provoke high affect, and she needs attention at that moment to lessen the burden.

Of course, you might not know the true extent of the emergency until you talk to the patient, but being able to delineate different procedures for patients based on the types of emergency situations could streamline your workflow.

With this foundation in place, let’s discuss the most common practice policies for dealing with these emergencies.

Instructing patients to call 911 or go to the emergency room (ER)

The pros.

- Meets minimum standards without any additional work.

- Reinforces work-life boundaries.

- Makes private practice tolerable.

The cons.

- Patients might not feel properly cared for.

- The patient might not want to call 911 in some situations (eg, suicidality).

- You might not know if your patient went to the ER unless hospital staff or the patient contacts you afterwards.

Using an answering service

The pros.

- Patients feel reassured that they can get your attention after hours and get a call back from you.

- Patients are familiar with this practice because it is widely used in the medical field.

- Operators are trained to screen for emergencies and can be given a script of questions to ask, and given clear guidelines so they know whether to contact you immediately.

- Establishes a healthy boundary between work and personal life.

The cons.

- Cost.

- Patients still might be frustrated if they can’t directly connect with you.

- Requires training and trusting the answering service staff.

Giving your home or cell number to patients

The pros.

- Patients might feel cared for and reassured that they can reach you directly at any time, which may, itself, be calming and reduce their need to contact you.

- Providers can maintain complete control over their practice at all times.

- Providers can market the practice as a “concierge” service.

- You can give your personal phone number to certain patients at certain times, rather than making it a practice-wide policy.

The cons.

- Providers may feel like they are working all the time. What if you go out of the country, or find yourself in a cell phone dead zone? You’ll need to have a colleague cover for you or refer patients to 911 or the ER.

- Some patients could abuse the privilege.