User login

Is your patient’s poor recall more than just a ‘senior moment’?

Memory and other cognitive complaints are common among the general population and become more prevalent with age.1 People who have significant emotional investment in their cognitive competence, mood disturbance, somatic symptoms, and anxiety or related disorders are likely to worry more about their cognitive functioning as they age.

Common complaints

Age-related complaints, typically beginning by age 50, often include problems retaining or retrieving names, difficulty recalling details of conversations and written materials, and hazy recollection of remote events and the time frame of recent life events. Common complaints involve difficulties with mental calculations, multi-tasking (including vulnerability to distraction), and problems keeping track of and organizing information. The most common complaint is difficulty with remembering the reason for entering a room.

More concerning are complaints involving recurrent lapses in judgment or forgetfulness with significant implications for everyday living (eg, physical safety, job performance, travel, and finances), especially when validated by friends or family members and coupled with decline in at least 1 activity of daily living, and poor insight.

Helping your forgetful patient

Office evaluation with brief cognitive screening instruments—namely, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the recent revision of the Mini-Mental State Examination—might help clarify the clinical presentation. Proceed with caution: Screening tests tap a limited number of neurocognitive functions and can generate a false-negative result among brighter and better educated patients and a false-positive result among the less intelligent and less educated.2 Applying age- and education-corrected norms can reduce misclassification but does not eliminate it.

Screening measures can facilitate decision-making regarding the need for more comprehensive psychometric assessment. Such evaluations sample a broader range of neurobehavioral domains, in greater depth, and provide a more nuanced picture of a patient’s neurocognition.

Findings on a battery of psychological and neuropsychological tests that might evoke concern include problems with incidental, anterograde, and recent memory that are not satisfactorily explained by: age and education or vocational training; estimated premorbid intelligence; residual neurodevelopmental disorders (attention, learning, and autistic-spectrum disorders); situational, sociocultural, and psychiatric factors; and motivational influences—notably, malingering.

Some difficulties with memory are highly associated with mild cognitive impairment or early dementia:

• anterograde memory (involving a reduced rate of verbal and nonverbal learning over repeated trials)

• poor retention

• accelerated forgetting of newly learned information

• failure to benefit from recognition and other mnemonic cues

• so-called source error confusion—a misattribution that involves difficulty differentiating target information from competing information, as reflected in confabulation errors and an elevated rate of intrusion errors.

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Weiner MF, Garrett R, Bret ME. Neuropsychiatric assessment and diagnosis. In: Weiner MF, Lipton AM, eds. Clinical manual of Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2012: 3-46.

2. Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms and commentary: third edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Memory and other cognitive complaints are common among the general population and become more prevalent with age.1 People who have significant emotional investment in their cognitive competence, mood disturbance, somatic symptoms, and anxiety or related disorders are likely to worry more about their cognitive functioning as they age.

Common complaints

Age-related complaints, typically beginning by age 50, often include problems retaining or retrieving names, difficulty recalling details of conversations and written materials, and hazy recollection of remote events and the time frame of recent life events. Common complaints involve difficulties with mental calculations, multi-tasking (including vulnerability to distraction), and problems keeping track of and organizing information. The most common complaint is difficulty with remembering the reason for entering a room.

More concerning are complaints involving recurrent lapses in judgment or forgetfulness with significant implications for everyday living (eg, physical safety, job performance, travel, and finances), especially when validated by friends or family members and coupled with decline in at least 1 activity of daily living, and poor insight.

Helping your forgetful patient

Office evaluation with brief cognitive screening instruments—namely, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the recent revision of the Mini-Mental State Examination—might help clarify the clinical presentation. Proceed with caution: Screening tests tap a limited number of neurocognitive functions and can generate a false-negative result among brighter and better educated patients and a false-positive result among the less intelligent and less educated.2 Applying age- and education-corrected norms can reduce misclassification but does not eliminate it.

Screening measures can facilitate decision-making regarding the need for more comprehensive psychometric assessment. Such evaluations sample a broader range of neurobehavioral domains, in greater depth, and provide a more nuanced picture of a patient’s neurocognition.

Findings on a battery of psychological and neuropsychological tests that might evoke concern include problems with incidental, anterograde, and recent memory that are not satisfactorily explained by: age and education or vocational training; estimated premorbid intelligence; residual neurodevelopmental disorders (attention, learning, and autistic-spectrum disorders); situational, sociocultural, and psychiatric factors; and motivational influences—notably, malingering.

Some difficulties with memory are highly associated with mild cognitive impairment or early dementia:

• anterograde memory (involving a reduced rate of verbal and nonverbal learning over repeated trials)

• poor retention

• accelerated forgetting of newly learned information

• failure to benefit from recognition and other mnemonic cues

• so-called source error confusion—a misattribution that involves difficulty differentiating target information from competing information, as reflected in confabulation errors and an elevated rate of intrusion errors.

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Memory and other cognitive complaints are common among the general population and become more prevalent with age.1 People who have significant emotional investment in their cognitive competence, mood disturbance, somatic symptoms, and anxiety or related disorders are likely to worry more about their cognitive functioning as they age.

Common complaints

Age-related complaints, typically beginning by age 50, often include problems retaining or retrieving names, difficulty recalling details of conversations and written materials, and hazy recollection of remote events and the time frame of recent life events. Common complaints involve difficulties with mental calculations, multi-tasking (including vulnerability to distraction), and problems keeping track of and organizing information. The most common complaint is difficulty with remembering the reason for entering a room.

More concerning are complaints involving recurrent lapses in judgment or forgetfulness with significant implications for everyday living (eg, physical safety, job performance, travel, and finances), especially when validated by friends or family members and coupled with decline in at least 1 activity of daily living, and poor insight.

Helping your forgetful patient

Office evaluation with brief cognitive screening instruments—namely, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the recent revision of the Mini-Mental State Examination—might help clarify the clinical presentation. Proceed with caution: Screening tests tap a limited number of neurocognitive functions and can generate a false-negative result among brighter and better educated patients and a false-positive result among the less intelligent and less educated.2 Applying age- and education-corrected norms can reduce misclassification but does not eliminate it.

Screening measures can facilitate decision-making regarding the need for more comprehensive psychometric assessment. Such evaluations sample a broader range of neurobehavioral domains, in greater depth, and provide a more nuanced picture of a patient’s neurocognition.

Findings on a battery of psychological and neuropsychological tests that might evoke concern include problems with incidental, anterograde, and recent memory that are not satisfactorily explained by: age and education or vocational training; estimated premorbid intelligence; residual neurodevelopmental disorders (attention, learning, and autistic-spectrum disorders); situational, sociocultural, and psychiatric factors; and motivational influences—notably, malingering.

Some difficulties with memory are highly associated with mild cognitive impairment or early dementia:

• anterograde memory (involving a reduced rate of verbal and nonverbal learning over repeated trials)

• poor retention

• accelerated forgetting of newly learned information

• failure to benefit from recognition and other mnemonic cues

• so-called source error confusion—a misattribution that involves difficulty differentiating target information from competing information, as reflected in confabulation errors and an elevated rate of intrusion errors.

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Weiner MF, Garrett R, Bret ME. Neuropsychiatric assessment and diagnosis. In: Weiner MF, Lipton AM, eds. Clinical manual of Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2012: 3-46.

2. Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms and commentary: third edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

1. Weiner MF, Garrett R, Bret ME. Neuropsychiatric assessment and diagnosis. In: Weiner MF, Lipton AM, eds. Clinical manual of Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2012: 3-46.

2. Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms and commentary: third edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Discharging your patients who display contingency-based suicidality: 6 steps

Discharging patients from a hospital or emergency department despite his (her) ongoing suicidal ideation is a clinical dilemma. Typically, these patients do not respond to hospital care and do not follow up after discharge. They often have a poorly treated illness and many unmet psychosocial and interpersonal needs.1 These patients may communicate their suicidality as conditional, aimed at satisfying unmet needs; secondary gain; dependency needs; or remaining in the sick role. Faced with impending discharge, such a patient might increase the intensity of his suicidal statements or engage in behaviors that subvert discharge. Some go as far as to engage in behaviors with apparent suicidal intent soon after discharge.

A complicated decision

Such patients often are at a chronically elevated risk for suicide because of mood disorders, personality pathology, substance use disorder, or a history of serious suicide attempt.2 Do not dismiss a patient’s suicidal statements; he is ill and may end his own life.

Managing these situations can put you under a variety of pressures: your own negative emotional and psychological reactions to the patient; pressure from staff to avoid admission or expedite discharge of the patient; and administrative pressure to efficiently manage resources.3 You’re faced with a difficult decision: Discharge a patient who might self-harm or commit suicide, or continue care that may be counterproductive.

We propose 6 steps that have helped us promote good clinical care while documenting the necessary information to manage risk in these complex situations.

1. Define and document the clinical situation. Summarize the clinical dilemma.

2. Assess and document current suicide risk.4 Conduct a formal suicide risk assessment; if necessary, reassess throughout care. Focus on dynamic risk factors; protective risk factors (static and dynamic); acute stressors (or lack thereof) that would increase their risk of suicide above their chronically elevated baseline; and access to lethal means—firearms, stockpiled medication, etc.

3. Document modified dynamic or protective factors. Review the dynamic risk and protective factors you have identified and how they have been modified by treatment to date. If dynamic factors have not been modified, indicate why and document the recommended plan to address these matters. You might not be able to provide relief, but you should be able to outline a plan for eventual relief.

4. Document the reasons continued care in the acute setting is not indicated. Reasons might include: the patient isn’t participating in recommended care or treatment; the patient isn’t improving, or is becoming worse, in the care environment; continued care is preventing or interfering with access to more effective care options; is counterproductive to the patient’s stated goals; or compromising the safety benefit of the structured care environment because the patient is not collaborating with his care team.

5. Document your discussion of discharge with the patient. Highlight attempts to engage the patient in adaptive problem solving. Work out a crisis or suicide safety plan and give the patient a copy and keep a copy in his (her) chart.

If the patient refuses to engage in safety planning, document it in the chart. Note the absence of any conditions that might impair the patient’s volitional capacity to not end their life—intoxication, delirium, acute psychosis, etc. Explicitly frame the patient’s responsibility for his life. Discuss and document a follow-up plan and make direct contact with providers and social supports, documenting whether contacting these providers was successful.

6. Consult with a colleague. An informal non-visit consultation with a colleague demonstrates your recognition of the complexity of the situation and your due diligence in arriving at a discharge decision. Consultation often will result in useful additional strategies for managing or engaging the patient. A colleague’s agreement helps demonstrate that “average practitioner” and “prudent practitioner” standards of care have been met with respect to clinical decision-making.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Lambert MT, Bonner J. Characteristics and six-month outcome of patients who use suicide threats to seek hospital admission. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(8):871-873.

2. Zaheer J, Links PS, Liu E. Assessment and emergency management of suicidality in personality disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(3):527-543, viii-ix.

3. Gutheil TG, Schetky D. A date with death: management of time-based and contingent suicidal intent. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1502-1507.

4. Haney EM, O’Neil ME, Carson S, et al. Suicide risk factors and risk assessment tools: a systematic review. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012.

Discharging patients from a hospital or emergency department despite his (her) ongoing suicidal ideation is a clinical dilemma. Typically, these patients do not respond to hospital care and do not follow up after discharge. They often have a poorly treated illness and many unmet psychosocial and interpersonal needs.1 These patients may communicate their suicidality as conditional, aimed at satisfying unmet needs; secondary gain; dependency needs; or remaining in the sick role. Faced with impending discharge, such a patient might increase the intensity of his suicidal statements or engage in behaviors that subvert discharge. Some go as far as to engage in behaviors with apparent suicidal intent soon after discharge.

A complicated decision

Such patients often are at a chronically elevated risk for suicide because of mood disorders, personality pathology, substance use disorder, or a history of serious suicide attempt.2 Do not dismiss a patient’s suicidal statements; he is ill and may end his own life.

Managing these situations can put you under a variety of pressures: your own negative emotional and psychological reactions to the patient; pressure from staff to avoid admission or expedite discharge of the patient; and administrative pressure to efficiently manage resources.3 You’re faced with a difficult decision: Discharge a patient who might self-harm or commit suicide, or continue care that may be counterproductive.

We propose 6 steps that have helped us promote good clinical care while documenting the necessary information to manage risk in these complex situations.

1. Define and document the clinical situation. Summarize the clinical dilemma.

2. Assess and document current suicide risk.4 Conduct a formal suicide risk assessment; if necessary, reassess throughout care. Focus on dynamic risk factors; protective risk factors (static and dynamic); acute stressors (or lack thereof) that would increase their risk of suicide above their chronically elevated baseline; and access to lethal means—firearms, stockpiled medication, etc.

3. Document modified dynamic or protective factors. Review the dynamic risk and protective factors you have identified and how they have been modified by treatment to date. If dynamic factors have not been modified, indicate why and document the recommended plan to address these matters. You might not be able to provide relief, but you should be able to outline a plan for eventual relief.

4. Document the reasons continued care in the acute setting is not indicated. Reasons might include: the patient isn’t participating in recommended care or treatment; the patient isn’t improving, or is becoming worse, in the care environment; continued care is preventing or interfering with access to more effective care options; is counterproductive to the patient’s stated goals; or compromising the safety benefit of the structured care environment because the patient is not collaborating with his care team.

5. Document your discussion of discharge with the patient. Highlight attempts to engage the patient in adaptive problem solving. Work out a crisis or suicide safety plan and give the patient a copy and keep a copy in his (her) chart.

If the patient refuses to engage in safety planning, document it in the chart. Note the absence of any conditions that might impair the patient’s volitional capacity to not end their life—intoxication, delirium, acute psychosis, etc. Explicitly frame the patient’s responsibility for his life. Discuss and document a follow-up plan and make direct contact with providers and social supports, documenting whether contacting these providers was successful.

6. Consult with a colleague. An informal non-visit consultation with a colleague demonstrates your recognition of the complexity of the situation and your due diligence in arriving at a discharge decision. Consultation often will result in useful additional strategies for managing or engaging the patient. A colleague’s agreement helps demonstrate that “average practitioner” and “prudent practitioner” standards of care have been met with respect to clinical decision-making.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Discharging patients from a hospital or emergency department despite his (her) ongoing suicidal ideation is a clinical dilemma. Typically, these patients do not respond to hospital care and do not follow up after discharge. They often have a poorly treated illness and many unmet psychosocial and interpersonal needs.1 These patients may communicate their suicidality as conditional, aimed at satisfying unmet needs; secondary gain; dependency needs; or remaining in the sick role. Faced with impending discharge, such a patient might increase the intensity of his suicidal statements or engage in behaviors that subvert discharge. Some go as far as to engage in behaviors with apparent suicidal intent soon after discharge.

A complicated decision

Such patients often are at a chronically elevated risk for suicide because of mood disorders, personality pathology, substance use disorder, or a history of serious suicide attempt.2 Do not dismiss a patient’s suicidal statements; he is ill and may end his own life.

Managing these situations can put you under a variety of pressures: your own negative emotional and psychological reactions to the patient; pressure from staff to avoid admission or expedite discharge of the patient; and administrative pressure to efficiently manage resources.3 You’re faced with a difficult decision: Discharge a patient who might self-harm or commit suicide, or continue care that may be counterproductive.

We propose 6 steps that have helped us promote good clinical care while documenting the necessary information to manage risk in these complex situations.

1. Define and document the clinical situation. Summarize the clinical dilemma.

2. Assess and document current suicide risk.4 Conduct a formal suicide risk assessment; if necessary, reassess throughout care. Focus on dynamic risk factors; protective risk factors (static and dynamic); acute stressors (or lack thereof) that would increase their risk of suicide above their chronically elevated baseline; and access to lethal means—firearms, stockpiled medication, etc.

3. Document modified dynamic or protective factors. Review the dynamic risk and protective factors you have identified and how they have been modified by treatment to date. If dynamic factors have not been modified, indicate why and document the recommended plan to address these matters. You might not be able to provide relief, but you should be able to outline a plan for eventual relief.

4. Document the reasons continued care in the acute setting is not indicated. Reasons might include: the patient isn’t participating in recommended care or treatment; the patient isn’t improving, or is becoming worse, in the care environment; continued care is preventing or interfering with access to more effective care options; is counterproductive to the patient’s stated goals; or compromising the safety benefit of the structured care environment because the patient is not collaborating with his care team.

5. Document your discussion of discharge with the patient. Highlight attempts to engage the patient in adaptive problem solving. Work out a crisis or suicide safety plan and give the patient a copy and keep a copy in his (her) chart.

If the patient refuses to engage in safety planning, document it in the chart. Note the absence of any conditions that might impair the patient’s volitional capacity to not end their life—intoxication, delirium, acute psychosis, etc. Explicitly frame the patient’s responsibility for his life. Discuss and document a follow-up plan and make direct contact with providers and social supports, documenting whether contacting these providers was successful.

6. Consult with a colleague. An informal non-visit consultation with a colleague demonstrates your recognition of the complexity of the situation and your due diligence in arriving at a discharge decision. Consultation often will result in useful additional strategies for managing or engaging the patient. A colleague’s agreement helps demonstrate that “average practitioner” and “prudent practitioner” standards of care have been met with respect to clinical decision-making.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Lambert MT, Bonner J. Characteristics and six-month outcome of patients who use suicide threats to seek hospital admission. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(8):871-873.

2. Zaheer J, Links PS, Liu E. Assessment and emergency management of suicidality in personality disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(3):527-543, viii-ix.

3. Gutheil TG, Schetky D. A date with death: management of time-based and contingent suicidal intent. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1502-1507.

4. Haney EM, O’Neil ME, Carson S, et al. Suicide risk factors and risk assessment tools: a systematic review. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012.

1. Lambert MT, Bonner J. Characteristics and six-month outcome of patients who use suicide threats to seek hospital admission. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(8):871-873.

2. Zaheer J, Links PS, Liu E. Assessment and emergency management of suicidality in personality disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(3):527-543, viii-ix.

3. Gutheil TG, Schetky D. A date with death: management of time-based and contingent suicidal intent. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1502-1507.

4. Haney EM, O’Neil ME, Carson S, et al. Suicide risk factors and risk assessment tools: a systematic review. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012.

Is he DISTRACTED? Considerations when diagnosing ADHD in an adult

Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can be challenging to assess accurately. Adult ADHD differs significantly from childhood ADHD, in that hyperactivity often is absent or greatly diminished, comorbid disorders (depression or substance use) are common, and previously compensated attention deficits in school can manifest in the patient’s personal and professional life.1

The mnemonic DISTRACTED can help when recalling key components in assessing adult ADHD.2 Because ADHD is a developmental disorder—there are signs of onset in childhood—it is important to maintain a longitudinal view when asking about patterns of behavior or thinking.

Distractibility. Is there a pattern of getting “off track” in conversations or in school or work situations because of straying thoughts or daydreams? Is there a tendency to over-respond to extraneous stimuli (eg, cell phones, computers, television) that impedes the patient’s ability to converse, receive information, or follow directions?

Impulsivity. Does the patient have a history of saying things “off the cuff,” interrupting others, or “walking on” someone else’s words in a conversation? Is impulsivity evident in the person’s substance use or spending patterns?

School history. This domain is important in diagnosing ADHD in adults because there needs to be evidence that the disorder was present from an early age. How did the patient perform in school (ie, grades, organization, completion of homework assignments)? Was there a behavioral pattern that reflected hyperactivity (could not stay seated) or emotional dysregulation (frequent outbursts)?

Task completion. Does the patient have trouble finishing assignments at work, staying focused on a project that is considered boring, or completing a home project (eg, fixing a leaky faucet) in a timely fashion?

Rating scales. Rating scales should be used to help support the diagnosis, based on the patient’s history and life story. There are >12 scales that can be utilized in a

clinical setting3; the ADHD/Hyperactivity Disorder Self-Report Scale is a brief and easy measure of core ADHD symptoms.

Accidents. Adults with ADHD often are accident-prone because of inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity. Does the patient have a history of unintentionally hurting himself because he “wasn’t paying attention” (falls, burns), or was too impatient (traffic accidents or citations)?

Commitments. Does the patient fail to fulfill verbal obligations (by arriving late, forgetting to run errands)? Has this difficulty to commit created problems in relationships over time?

Time management. How difficult is it for the patient to stay organized while balancing work expectations, social obligations, and family needs? Is there a pattern of chaotic scheduling with regard to meals, work, or sleeping?

Employment. Has the patient changed jobs because the work becomes “too boring” or “uninteresting”? Is there a pattern of being terminated because of poor work quality based on time management or job performance?

Decisions. Adults with ADHD often make hasty, ill-informed choices or procrastinate so that they do not have to make a decision. Does the patient’s decision-making reveal a pattern of being too distracted to hear the information needed, or too impatient to consider all the details?

Remember: No single component of this mnemonic alone suffices to make a diagnosis of adult ADHD. However, these considerations will help clarify what lies behind your DISTRACTED patient’s search for self-understanding and appropriate medical care.

Disclosure

Dr. Christensen reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Barkley RA, Brown TE. Unrecognized attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults presenting with other psychiatric disorders. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(11):977-984.

2. Barkley R. Taking charge of adult ADHD. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010.

3. Attwell C. ADHD, rating scales, and your practice today. The Carlat Psychiatry Report. 2012;10(12):1,3,5-8.

Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can be challenging to assess accurately. Adult ADHD differs significantly from childhood ADHD, in that hyperactivity often is absent or greatly diminished, comorbid disorders (depression or substance use) are common, and previously compensated attention deficits in school can manifest in the patient’s personal and professional life.1

The mnemonic DISTRACTED can help when recalling key components in assessing adult ADHD.2 Because ADHD is a developmental disorder—there are signs of onset in childhood—it is important to maintain a longitudinal view when asking about patterns of behavior or thinking.

Distractibility. Is there a pattern of getting “off track” in conversations or in school or work situations because of straying thoughts or daydreams? Is there a tendency to over-respond to extraneous stimuli (eg, cell phones, computers, television) that impedes the patient’s ability to converse, receive information, or follow directions?

Impulsivity. Does the patient have a history of saying things “off the cuff,” interrupting others, or “walking on” someone else’s words in a conversation? Is impulsivity evident in the person’s substance use or spending patterns?

School history. This domain is important in diagnosing ADHD in adults because there needs to be evidence that the disorder was present from an early age. How did the patient perform in school (ie, grades, organization, completion of homework assignments)? Was there a behavioral pattern that reflected hyperactivity (could not stay seated) or emotional dysregulation (frequent outbursts)?

Task completion. Does the patient have trouble finishing assignments at work, staying focused on a project that is considered boring, or completing a home project (eg, fixing a leaky faucet) in a timely fashion?

Rating scales. Rating scales should be used to help support the diagnosis, based on the patient’s history and life story. There are >12 scales that can be utilized in a

clinical setting3; the ADHD/Hyperactivity Disorder Self-Report Scale is a brief and easy measure of core ADHD symptoms.

Accidents. Adults with ADHD often are accident-prone because of inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity. Does the patient have a history of unintentionally hurting himself because he “wasn’t paying attention” (falls, burns), or was too impatient (traffic accidents or citations)?

Commitments. Does the patient fail to fulfill verbal obligations (by arriving late, forgetting to run errands)? Has this difficulty to commit created problems in relationships over time?

Time management. How difficult is it for the patient to stay organized while balancing work expectations, social obligations, and family needs? Is there a pattern of chaotic scheduling with regard to meals, work, or sleeping?

Employment. Has the patient changed jobs because the work becomes “too boring” or “uninteresting”? Is there a pattern of being terminated because of poor work quality based on time management or job performance?

Decisions. Adults with ADHD often make hasty, ill-informed choices or procrastinate so that they do not have to make a decision. Does the patient’s decision-making reveal a pattern of being too distracted to hear the information needed, or too impatient to consider all the details?

Remember: No single component of this mnemonic alone suffices to make a diagnosis of adult ADHD. However, these considerations will help clarify what lies behind your DISTRACTED patient’s search for self-understanding and appropriate medical care.

Disclosure

Dr. Christensen reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can be challenging to assess accurately. Adult ADHD differs significantly from childhood ADHD, in that hyperactivity often is absent or greatly diminished, comorbid disorders (depression or substance use) are common, and previously compensated attention deficits in school can manifest in the patient’s personal and professional life.1

The mnemonic DISTRACTED can help when recalling key components in assessing adult ADHD.2 Because ADHD is a developmental disorder—there are signs of onset in childhood—it is important to maintain a longitudinal view when asking about patterns of behavior or thinking.

Distractibility. Is there a pattern of getting “off track” in conversations or in school or work situations because of straying thoughts or daydreams? Is there a tendency to over-respond to extraneous stimuli (eg, cell phones, computers, television) that impedes the patient’s ability to converse, receive information, or follow directions?

Impulsivity. Does the patient have a history of saying things “off the cuff,” interrupting others, or “walking on” someone else’s words in a conversation? Is impulsivity evident in the person’s substance use or spending patterns?

School history. This domain is important in diagnosing ADHD in adults because there needs to be evidence that the disorder was present from an early age. How did the patient perform in school (ie, grades, organization, completion of homework assignments)? Was there a behavioral pattern that reflected hyperactivity (could not stay seated) or emotional dysregulation (frequent outbursts)?

Task completion. Does the patient have trouble finishing assignments at work, staying focused on a project that is considered boring, or completing a home project (eg, fixing a leaky faucet) in a timely fashion?

Rating scales. Rating scales should be used to help support the diagnosis, based on the patient’s history and life story. There are >12 scales that can be utilized in a

clinical setting3; the ADHD/Hyperactivity Disorder Self-Report Scale is a brief and easy measure of core ADHD symptoms.

Accidents. Adults with ADHD often are accident-prone because of inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity. Does the patient have a history of unintentionally hurting himself because he “wasn’t paying attention” (falls, burns), or was too impatient (traffic accidents or citations)?

Commitments. Does the patient fail to fulfill verbal obligations (by arriving late, forgetting to run errands)? Has this difficulty to commit created problems in relationships over time?

Time management. How difficult is it for the patient to stay organized while balancing work expectations, social obligations, and family needs? Is there a pattern of chaotic scheduling with regard to meals, work, or sleeping?

Employment. Has the patient changed jobs because the work becomes “too boring” or “uninteresting”? Is there a pattern of being terminated because of poor work quality based on time management or job performance?

Decisions. Adults with ADHD often make hasty, ill-informed choices or procrastinate so that they do not have to make a decision. Does the patient’s decision-making reveal a pattern of being too distracted to hear the information needed, or too impatient to consider all the details?

Remember: No single component of this mnemonic alone suffices to make a diagnosis of adult ADHD. However, these considerations will help clarify what lies behind your DISTRACTED patient’s search for self-understanding and appropriate medical care.

Disclosure

Dr. Christensen reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Barkley RA, Brown TE. Unrecognized attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults presenting with other psychiatric disorders. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(11):977-984.

2. Barkley R. Taking charge of adult ADHD. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010.

3. Attwell C. ADHD, rating scales, and your practice today. The Carlat Psychiatry Report. 2012;10(12):1,3,5-8.

1. Barkley RA, Brown TE. Unrecognized attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults presenting with other psychiatric disorders. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(11):977-984.

2. Barkley R. Taking charge of adult ADHD. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010.

3. Attwell C. ADHD, rating scales, and your practice today. The Carlat Psychiatry Report. 2012;10(12):1,3,5-8.

Out of the cupboard and into the clinic: Nutmeg-induced mood disorder

Clinicians often are unaware of a patient’s misuse or abuse of easily accessible substances such as spices, herbs, and natural supplements. This can lead to misdiagnosed severe psychiatric disorders and, more alarmingly, unnecessary use of long-term psychotropics and psychiatric services.

Excessive ingestion of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) can produce psychiatric symptoms because it contains myristicin, a psychoactive substance, in its aromatic oil.1 It is structurally similar to other hallucinogenic compounds such as mescaline. The effects of nutmeg could be attributed to metabolic formation of amphetamine derivatives from its core ingredients: elemicin, myristicin, and safrole.1-3 However, neither amphetamine derivatives nor core ingredients are detected in the urine of patients suspected of abusing nutmeg, which makes diagnosis challenging.

We present a case of nutmeg abuse leading to psychotic depression.

Nutmeg and depression

Mr. D, age 50, is admitted to our inpatient psychiatric unit with severe dysphoria, hopelessness, persecutory delusions, suicidal ideation, and a sense of impending doom for the third time in 2 years. At previous admissions, he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

During his first admission, Mr. D reported an intentional overdose by water intoxication; laboratory studies revealed hyponatremia, liver dysfunction, abnormal cardiac markers, increased creatine kinase, and leukocytosis with neutrophilia. With supportive treatment, all parameters returned to the normal range within 7 days.

At his third admission, Mr. D describes an extensive history of nutmeg abuse. He reports achieving desirable psychoactive effects such as excitement, euphoria, enhanced sensory perceptions, and racing thoughts within a half hour of ingesting 1 teaspoon (5 g) of nutmeg; effects lasted for 6 hours. He reports that consuming 2 teaspoons (10 g) produced a “stronger” effect, and that 1 tablespoon (15 g) was associated with severe dysphoria, fear, psychosis, suicidal ideation, and behavior, which led to his psychiatric admissions. He denies any other substance use.

Urine drug screen and other routine laboratory investigations are negative. Symptoms resolve spontaneously within 3 days and he is managed without pharmacotherapy. The diagnosis is revised to substance-induced mood disorder with psychotic features. We provide psychoeducation about nutmeg’s psychoactive effects, and Mr. D is motivated to stop abusing nutmeg. Three years later he remains in good health.

Effects of nutmeg

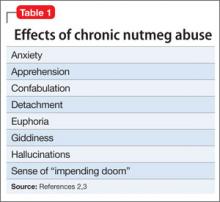

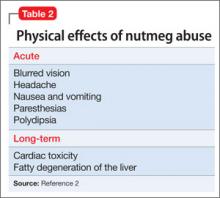

Acute nutmeg intoxication produces anxiety, fear, and hallucinations, and generally is self-limited, with most symptoms resolving within 24 hours.2 Chronic effects of nutmeg abuse resemble those of marijuana abuse (Table 1). Acute and long-term physical effects are listed in Table 2.

Be alert for presentations of a ‘natural high’

Nutmeg, other spices, and herbs can be used by persons looking for a ”natural high”; as we saw with Mr. D, nutmeg abuse can present as a mood disorder resembling bipolar disorder. An acute, atypical presentation of mood changes or suicidal ideation should prompt you to investigate causes other than primary mood or psychotic disorders, and should include consideration of the effects of atypical drugs—and spices—of abuse.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Weiss G. Hallucinogenic and narcotic-like effects of powdered Myristica (nutmeg). Psychiatr Q. 1960;34:346-356.

2. McKenna A, Nordt SP, Ryan J. Acute nutmeg poisoning. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11(4):240-241.

3. Brenner N, Frank OS, Knight E. Chronic nutmeg psychosis. J R Soc Med. 1993;86(3):179-180.

Clinicians often are unaware of a patient’s misuse or abuse of easily accessible substances such as spices, herbs, and natural supplements. This can lead to misdiagnosed severe psychiatric disorders and, more alarmingly, unnecessary use of long-term psychotropics and psychiatric services.

Excessive ingestion of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) can produce psychiatric symptoms because it contains myristicin, a psychoactive substance, in its aromatic oil.1 It is structurally similar to other hallucinogenic compounds such as mescaline. The effects of nutmeg could be attributed to metabolic formation of amphetamine derivatives from its core ingredients: elemicin, myristicin, and safrole.1-3 However, neither amphetamine derivatives nor core ingredients are detected in the urine of patients suspected of abusing nutmeg, which makes diagnosis challenging.

We present a case of nutmeg abuse leading to psychotic depression.

Nutmeg and depression

Mr. D, age 50, is admitted to our inpatient psychiatric unit with severe dysphoria, hopelessness, persecutory delusions, suicidal ideation, and a sense of impending doom for the third time in 2 years. At previous admissions, he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

During his first admission, Mr. D reported an intentional overdose by water intoxication; laboratory studies revealed hyponatremia, liver dysfunction, abnormal cardiac markers, increased creatine kinase, and leukocytosis with neutrophilia. With supportive treatment, all parameters returned to the normal range within 7 days.

At his third admission, Mr. D describes an extensive history of nutmeg abuse. He reports achieving desirable psychoactive effects such as excitement, euphoria, enhanced sensory perceptions, and racing thoughts within a half hour of ingesting 1 teaspoon (5 g) of nutmeg; effects lasted for 6 hours. He reports that consuming 2 teaspoons (10 g) produced a “stronger” effect, and that 1 tablespoon (15 g) was associated with severe dysphoria, fear, psychosis, suicidal ideation, and behavior, which led to his psychiatric admissions. He denies any other substance use.

Urine drug screen and other routine laboratory investigations are negative. Symptoms resolve spontaneously within 3 days and he is managed without pharmacotherapy. The diagnosis is revised to substance-induced mood disorder with psychotic features. We provide psychoeducation about nutmeg’s psychoactive effects, and Mr. D is motivated to stop abusing nutmeg. Three years later he remains in good health.

Effects of nutmeg

Acute nutmeg intoxication produces anxiety, fear, and hallucinations, and generally is self-limited, with most symptoms resolving within 24 hours.2 Chronic effects of nutmeg abuse resemble those of marijuana abuse (Table 1). Acute and long-term physical effects are listed in Table 2.

Be alert for presentations of a ‘natural high’

Nutmeg, other spices, and herbs can be used by persons looking for a ”natural high”; as we saw with Mr. D, nutmeg abuse can present as a mood disorder resembling bipolar disorder. An acute, atypical presentation of mood changes or suicidal ideation should prompt you to investigate causes other than primary mood or psychotic disorders, and should include consideration of the effects of atypical drugs—and spices—of abuse.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Clinicians often are unaware of a patient’s misuse or abuse of easily accessible substances such as spices, herbs, and natural supplements. This can lead to misdiagnosed severe psychiatric disorders and, more alarmingly, unnecessary use of long-term psychotropics and psychiatric services.

Excessive ingestion of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) can produce psychiatric symptoms because it contains myristicin, a psychoactive substance, in its aromatic oil.1 It is structurally similar to other hallucinogenic compounds such as mescaline. The effects of nutmeg could be attributed to metabolic formation of amphetamine derivatives from its core ingredients: elemicin, myristicin, and safrole.1-3 However, neither amphetamine derivatives nor core ingredients are detected in the urine of patients suspected of abusing nutmeg, which makes diagnosis challenging.

We present a case of nutmeg abuse leading to psychotic depression.

Nutmeg and depression

Mr. D, age 50, is admitted to our inpatient psychiatric unit with severe dysphoria, hopelessness, persecutory delusions, suicidal ideation, and a sense of impending doom for the third time in 2 years. At previous admissions, he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

During his first admission, Mr. D reported an intentional overdose by water intoxication; laboratory studies revealed hyponatremia, liver dysfunction, abnormal cardiac markers, increased creatine kinase, and leukocytosis with neutrophilia. With supportive treatment, all parameters returned to the normal range within 7 days.

At his third admission, Mr. D describes an extensive history of nutmeg abuse. He reports achieving desirable psychoactive effects such as excitement, euphoria, enhanced sensory perceptions, and racing thoughts within a half hour of ingesting 1 teaspoon (5 g) of nutmeg; effects lasted for 6 hours. He reports that consuming 2 teaspoons (10 g) produced a “stronger” effect, and that 1 tablespoon (15 g) was associated with severe dysphoria, fear, psychosis, suicidal ideation, and behavior, which led to his psychiatric admissions. He denies any other substance use.

Urine drug screen and other routine laboratory investigations are negative. Symptoms resolve spontaneously within 3 days and he is managed without pharmacotherapy. The diagnosis is revised to substance-induced mood disorder with psychotic features. We provide psychoeducation about nutmeg’s psychoactive effects, and Mr. D is motivated to stop abusing nutmeg. Three years later he remains in good health.

Effects of nutmeg

Acute nutmeg intoxication produces anxiety, fear, and hallucinations, and generally is self-limited, with most symptoms resolving within 24 hours.2 Chronic effects of nutmeg abuse resemble those of marijuana abuse (Table 1). Acute and long-term physical effects are listed in Table 2.

Be alert for presentations of a ‘natural high’

Nutmeg, other spices, and herbs can be used by persons looking for a ”natural high”; as we saw with Mr. D, nutmeg abuse can present as a mood disorder resembling bipolar disorder. An acute, atypical presentation of mood changes or suicidal ideation should prompt you to investigate causes other than primary mood or psychotic disorders, and should include consideration of the effects of atypical drugs—and spices—of abuse.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Weiss G. Hallucinogenic and narcotic-like effects of powdered Myristica (nutmeg). Psychiatr Q. 1960;34:346-356.

2. McKenna A, Nordt SP, Ryan J. Acute nutmeg poisoning. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11(4):240-241.

3. Brenner N, Frank OS, Knight E. Chronic nutmeg psychosis. J R Soc Med. 1993;86(3):179-180.

1. Weiss G. Hallucinogenic and narcotic-like effects of powdered Myristica (nutmeg). Psychiatr Q. 1960;34:346-356.

2. McKenna A, Nordt SP, Ryan J. Acute nutmeg poisoning. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11(4):240-241.

3. Brenner N, Frank OS, Knight E. Chronic nutmeg psychosis. J R Soc Med. 1993;86(3):179-180.

Head banging: Cause for worry, or normal childhood development?

Most children who head bang—rhythmic movement of the head against a solid object, marked by compulsive repetitiveness1—usually are normal, healthy, well-cared-for children, in whom no cause for this activity can be determined. More common in boys than in girls, childhood head banging usually starts when the child is age 18 months, but he (she) should grow out of it by age 4.1,2 Nevertheless, you should be prepared to provide careful, targeted evaluation when presented with a child who head bangs, and discuss with parents or caregivers the possibility of a nonphysiologic cause, such as disruptions or discord in the home.

First concern: Is this normal?

Although head banging is seen in 5% to 15% of healthy children,1 children who are mentally retarded, blind, deaf, or autistic are more likely to participate in head banging.1 There also may be a familial predisposition; head banging is more frequent among cousins of children who bang their heads.1 Some studies have found that socioeconomic status, birth order, response to music, and motor development are correlated with head banging.1

Leung and colleagues1 propose that head banging is an integral part of normal development; a tension-releasing maneuver; an attention-seeking device; and a form of pain relief in response to acute illnesses. Fatigue, hunger, teething, or discomfort from a wet diaper can increase the tendency to head bang.

How does it happen?

Head banging generally occurs before sleep. The child will repeatedly bang his head—usually the frontal-parietal region—against a pillow, headboard, or railing of a crib 60 to 80 times per minute.1 This repetitive motion may continue for a few minutes or as long as an hour. While head banging, the child does not seem to experience pain or discomfort, but may appear relaxed or happy. Although this habit appears alarming (calluses, bruises, abrasions, and contusions may occur—especially in children with mental retardation)1,2, there rarely is significant head damage.

Talking to concerned parents

Head banging can be confused with typical temper tantrums, spasmus nutans (triad of pendular nystagmus, head nodding, and torticollis), and infantile myoclonic seizures (sudden dropping of the head and flexion of the arms).1 Take a detailed history and careful evaluation of the parent-child relationship to uncover any underlying causes, such as an unhappy home environment (eg, divorce or neglect). A complete physical examination may reveal an ear infection, visual problems, deafness, cerebral palsy, mental retardation, or evidence of abuse.

Psychotropic medication is not recommended. Treatment options include:1

• treating underlying abnormalities, such as otitis media

• padding the sides of the crib

• providing auditory stimulation, including allowing the child to participate in rhythmic actions during the day3

• fitting the child for a protective helmet.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Leung AK, Robson WL. Head banging. J Singapore Paediatr Soc. 1990;32(1-2):14-17.

2. Kravitz H, Rosenthal V, Teplitz Z, et al. A study of head-banging in infants and children. Dis Nerv Syst. 1960;21:203-208.

3. Ryan NM. Body rocking, head banging, and head rolling: an analysis of rhythmic motor activities in normal infants. Pediatr Nurs. 1983;9(4):281-285, 296.

Most children who head bang—rhythmic movement of the head against a solid object, marked by compulsive repetitiveness1—usually are normal, healthy, well-cared-for children, in whom no cause for this activity can be determined. More common in boys than in girls, childhood head banging usually starts when the child is age 18 months, but he (she) should grow out of it by age 4.1,2 Nevertheless, you should be prepared to provide careful, targeted evaluation when presented with a child who head bangs, and discuss with parents or caregivers the possibility of a nonphysiologic cause, such as disruptions or discord in the home.

First concern: Is this normal?

Although head banging is seen in 5% to 15% of healthy children,1 children who are mentally retarded, blind, deaf, or autistic are more likely to participate in head banging.1 There also may be a familial predisposition; head banging is more frequent among cousins of children who bang their heads.1 Some studies have found that socioeconomic status, birth order, response to music, and motor development are correlated with head banging.1

Leung and colleagues1 propose that head banging is an integral part of normal development; a tension-releasing maneuver; an attention-seeking device; and a form of pain relief in response to acute illnesses. Fatigue, hunger, teething, or discomfort from a wet diaper can increase the tendency to head bang.

How does it happen?

Head banging generally occurs before sleep. The child will repeatedly bang his head—usually the frontal-parietal region—against a pillow, headboard, or railing of a crib 60 to 80 times per minute.1 This repetitive motion may continue for a few minutes or as long as an hour. While head banging, the child does not seem to experience pain or discomfort, but may appear relaxed or happy. Although this habit appears alarming (calluses, bruises, abrasions, and contusions may occur—especially in children with mental retardation)1,2, there rarely is significant head damage.

Talking to concerned parents

Head banging can be confused with typical temper tantrums, spasmus nutans (triad of pendular nystagmus, head nodding, and torticollis), and infantile myoclonic seizures (sudden dropping of the head and flexion of the arms).1 Take a detailed history and careful evaluation of the parent-child relationship to uncover any underlying causes, such as an unhappy home environment (eg, divorce or neglect). A complete physical examination may reveal an ear infection, visual problems, deafness, cerebral palsy, mental retardation, or evidence of abuse.

Psychotropic medication is not recommended. Treatment options include:1

• treating underlying abnormalities, such as otitis media

• padding the sides of the crib

• providing auditory stimulation, including allowing the child to participate in rhythmic actions during the day3

• fitting the child for a protective helmet.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Most children who head bang—rhythmic movement of the head against a solid object, marked by compulsive repetitiveness1—usually are normal, healthy, well-cared-for children, in whom no cause for this activity can be determined. More common in boys than in girls, childhood head banging usually starts when the child is age 18 months, but he (she) should grow out of it by age 4.1,2 Nevertheless, you should be prepared to provide careful, targeted evaluation when presented with a child who head bangs, and discuss with parents or caregivers the possibility of a nonphysiologic cause, such as disruptions or discord in the home.

First concern: Is this normal?

Although head banging is seen in 5% to 15% of healthy children,1 children who are mentally retarded, blind, deaf, or autistic are more likely to participate in head banging.1 There also may be a familial predisposition; head banging is more frequent among cousins of children who bang their heads.1 Some studies have found that socioeconomic status, birth order, response to music, and motor development are correlated with head banging.1

Leung and colleagues1 propose that head banging is an integral part of normal development; a tension-releasing maneuver; an attention-seeking device; and a form of pain relief in response to acute illnesses. Fatigue, hunger, teething, or discomfort from a wet diaper can increase the tendency to head bang.

How does it happen?

Head banging generally occurs before sleep. The child will repeatedly bang his head—usually the frontal-parietal region—against a pillow, headboard, or railing of a crib 60 to 80 times per minute.1 This repetitive motion may continue for a few minutes or as long as an hour. While head banging, the child does not seem to experience pain or discomfort, but may appear relaxed or happy. Although this habit appears alarming (calluses, bruises, abrasions, and contusions may occur—especially in children with mental retardation)1,2, there rarely is significant head damage.

Talking to concerned parents

Head banging can be confused with typical temper tantrums, spasmus nutans (triad of pendular nystagmus, head nodding, and torticollis), and infantile myoclonic seizures (sudden dropping of the head and flexion of the arms).1 Take a detailed history and careful evaluation of the parent-child relationship to uncover any underlying causes, such as an unhappy home environment (eg, divorce or neglect). A complete physical examination may reveal an ear infection, visual problems, deafness, cerebral palsy, mental retardation, or evidence of abuse.

Psychotropic medication is not recommended. Treatment options include:1

• treating underlying abnormalities, such as otitis media

• padding the sides of the crib

• providing auditory stimulation, including allowing the child to participate in rhythmic actions during the day3

• fitting the child for a protective helmet.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Leung AK, Robson WL. Head banging. J Singapore Paediatr Soc. 1990;32(1-2):14-17.

2. Kravitz H, Rosenthal V, Teplitz Z, et al. A study of head-banging in infants and children. Dis Nerv Syst. 1960;21:203-208.

3. Ryan NM. Body rocking, head banging, and head rolling: an analysis of rhythmic motor activities in normal infants. Pediatr Nurs. 1983;9(4):281-285, 296.

1. Leung AK, Robson WL. Head banging. J Singapore Paediatr Soc. 1990;32(1-2):14-17.

2. Kravitz H, Rosenthal V, Teplitz Z, et al. A study of head-banging in infants and children. Dis Nerv Syst. 1960;21:203-208.

3. Ryan NM. Body rocking, head banging, and head rolling: an analysis of rhythmic motor activities in normal infants. Pediatr Nurs. 1983;9(4):281-285, 296.

6 ‘D’s: Next steps after an insufficient antipsychotic response

There are a lack of research on, and strategies for dealing with, an insufficient response to antipsychotics. Treatment often is guided by what is described in published case reports or anecdotal evidence, rather than the findings of systematic studies.

We propose that a patient be considered “difficult-to-treat” or “treatment-resistant” after experiencing limited or negative responses to 3 different antipsychotics—with ≥1 being a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA)—that the patient has taken for at least 6 to 8 weeks at the maximum recommended dosage. Furthermore, switching to clozapine is an important strategy; do not consider it solely a last resort.

These 6 ‘D’s can remind you of other problems to consider when evaluating a treatment-resistant patient.

Diagnosis. Is the diagnosis, including the presence of comorbid conditions, accurate? Are significant psychosocial stressors undermining treatment response? Treat any comorbid conditions and consider instituting adjunctive psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

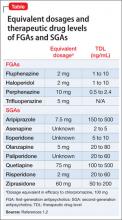

Dosage. Have the patient try the maximum recommended dosage if he (she) can tolerate it. Equivalent dosages of antipsychotics are shown in the Table,1,2 and can guide off-label use of higher dosages. Research does not support use of chlorpromazine equivalents >1,000 mg/d, and usually should not be employed. If using a higher than normal dosage, perform an ECG before the increase.3

Beneficial and adverse effects should be monitored carefully. Reduce the dosage after 3 months if the risk-benefit ratio does not justify the higher dosage.3

Duration. Try a treatment for at least 6 weeks at the maximum tolerated

dosage—even extending it to 12 weeks—before considering abandoning it because of insufficient response.

Drug interactions. Use a drug interaction tool to ensure drug-drug interactions are not reducing antipsychotic levels. A recent increase in smoking or decrease in caffeine intake can reduce the blood level of olanzapine and clozapine.4 Ultra-rapid metabolizers of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes may have a lower blood level of antipsychotic.

Consider pharmacogenetic testing in patients in whom you observe an unexpected lack of efficacy or adverse effects at customary dosages.

Double up. You might need to add another medication to the antipsychotic. Symptoms might help determine which medication to add:

- a combination of an SGA and a first-generation antipsychotic may be more effective than antipsychotic monotherapy5

- for prominent negative symptoms, consider using 2 SGAs of different potency together. Use caution when prescribing ziprasidone with another antipsychotic because this could prolong the QTc interval

- if a mood stabilizer is appropriate, consider lamotrigine because of its possible potentiating effect on SGAs6

- benzodiazepines can be used to reduce agitation or anxiety but are ineffective for psychosis.7

Drug levels. Measurement of the blood level of the drug is most useful when administering clozapine; focus on the clozapine, not on the norclozapine level that also is reported. Ensure a clozapine level of 350 to 600 ng/mL.

Therapeutic levels have been established for most antipsychotics (Table).1,2 Occasionally, knowing these levels can be helpful in evaluating patients for potential problems with absorption and metabolism of the drug, and with nonadherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Faden and Pinninti report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Mago receives grant/research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Institute, Genomind, and Shire.

1. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, et al. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686-693.

2. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

3. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus statement on high-dose antipsychotic medication. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/CR138.pdf. Published May 2006. Accessed March 26, 2013.

4. Pinninti NR, Mago R, de Leon J. Coffee, cigarettes and meds: what are the metabolic effects? Psychiatric Times. 2005;22(6):20-23.

5. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

6. Citrome L. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: what can we do about it? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(6):52-58.

7. Volz A, Khorsand V, Gillies D, et al. Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1): CD006391.

There are a lack of research on, and strategies for dealing with, an insufficient response to antipsychotics. Treatment often is guided by what is described in published case reports or anecdotal evidence, rather than the findings of systematic studies.

We propose that a patient be considered “difficult-to-treat” or “treatment-resistant” after experiencing limited or negative responses to 3 different antipsychotics—with ≥1 being a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA)—that the patient has taken for at least 6 to 8 weeks at the maximum recommended dosage. Furthermore, switching to clozapine is an important strategy; do not consider it solely a last resort.

These 6 ‘D’s can remind you of other problems to consider when evaluating a treatment-resistant patient.

Diagnosis. Is the diagnosis, including the presence of comorbid conditions, accurate? Are significant psychosocial stressors undermining treatment response? Treat any comorbid conditions and consider instituting adjunctive psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Dosage. Have the patient try the maximum recommended dosage if he (she) can tolerate it. Equivalent dosages of antipsychotics are shown in the Table,1,2 and can guide off-label use of higher dosages. Research does not support use of chlorpromazine equivalents >1,000 mg/d, and usually should not be employed. If using a higher than normal dosage, perform an ECG before the increase.3

Beneficial and adverse effects should be monitored carefully. Reduce the dosage after 3 months if the risk-benefit ratio does not justify the higher dosage.3

Duration. Try a treatment for at least 6 weeks at the maximum tolerated

dosage—even extending it to 12 weeks—before considering abandoning it because of insufficient response.

Drug interactions. Use a drug interaction tool to ensure drug-drug interactions are not reducing antipsychotic levels. A recent increase in smoking or decrease in caffeine intake can reduce the blood level of olanzapine and clozapine.4 Ultra-rapid metabolizers of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes may have a lower blood level of antipsychotic.

Consider pharmacogenetic testing in patients in whom you observe an unexpected lack of efficacy or adverse effects at customary dosages.

Double up. You might need to add another medication to the antipsychotic. Symptoms might help determine which medication to add:

- a combination of an SGA and a first-generation antipsychotic may be more effective than antipsychotic monotherapy5

- for prominent negative symptoms, consider using 2 SGAs of different potency together. Use caution when prescribing ziprasidone with another antipsychotic because this could prolong the QTc interval

- if a mood stabilizer is appropriate, consider lamotrigine because of its possible potentiating effect on SGAs6

- benzodiazepines can be used to reduce agitation or anxiety but are ineffective for psychosis.7

Drug levels. Measurement of the blood level of the drug is most useful when administering clozapine; focus on the clozapine, not on the norclozapine level that also is reported. Ensure a clozapine level of 350 to 600 ng/mL.

Therapeutic levels have been established for most antipsychotics (Table).1,2 Occasionally, knowing these levels can be helpful in evaluating patients for potential problems with absorption and metabolism of the drug, and with nonadherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Faden and Pinninti report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Mago receives grant/research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Institute, Genomind, and Shire.

There are a lack of research on, and strategies for dealing with, an insufficient response to antipsychotics. Treatment often is guided by what is described in published case reports or anecdotal evidence, rather than the findings of systematic studies.

We propose that a patient be considered “difficult-to-treat” or “treatment-resistant” after experiencing limited or negative responses to 3 different antipsychotics—with ≥1 being a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA)—that the patient has taken for at least 6 to 8 weeks at the maximum recommended dosage. Furthermore, switching to clozapine is an important strategy; do not consider it solely a last resort.

These 6 ‘D’s can remind you of other problems to consider when evaluating a treatment-resistant patient.

Diagnosis. Is the diagnosis, including the presence of comorbid conditions, accurate? Are significant psychosocial stressors undermining treatment response? Treat any comorbid conditions and consider instituting adjunctive psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Dosage. Have the patient try the maximum recommended dosage if he (she) can tolerate it. Equivalent dosages of antipsychotics are shown in the Table,1,2 and can guide off-label use of higher dosages. Research does not support use of chlorpromazine equivalents >1,000 mg/d, and usually should not be employed. If using a higher than normal dosage, perform an ECG before the increase.3

Beneficial and adverse effects should be monitored carefully. Reduce the dosage after 3 months if the risk-benefit ratio does not justify the higher dosage.3

Duration. Try a treatment for at least 6 weeks at the maximum tolerated

dosage—even extending it to 12 weeks—before considering abandoning it because of insufficient response.

Drug interactions. Use a drug interaction tool to ensure drug-drug interactions are not reducing antipsychotic levels. A recent increase in smoking or decrease in caffeine intake can reduce the blood level of olanzapine and clozapine.4 Ultra-rapid metabolizers of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes may have a lower blood level of antipsychotic.

Consider pharmacogenetic testing in patients in whom you observe an unexpected lack of efficacy or adverse effects at customary dosages.

Double up. You might need to add another medication to the antipsychotic. Symptoms might help determine which medication to add:

- a combination of an SGA and a first-generation antipsychotic may be more effective than antipsychotic monotherapy5

- for prominent negative symptoms, consider using 2 SGAs of different potency together. Use caution when prescribing ziprasidone with another antipsychotic because this could prolong the QTc interval

- if a mood stabilizer is appropriate, consider lamotrigine because of its possible potentiating effect on SGAs6

- benzodiazepines can be used to reduce agitation or anxiety but are ineffective for psychosis.7

Drug levels. Measurement of the blood level of the drug is most useful when administering clozapine; focus on the clozapine, not on the norclozapine level that also is reported. Ensure a clozapine level of 350 to 600 ng/mL.

Therapeutic levels have been established for most antipsychotics (Table).1,2 Occasionally, knowing these levels can be helpful in evaluating patients for potential problems with absorption and metabolism of the drug, and with nonadherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Faden and Pinninti report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Mago receives grant/research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Institute, Genomind, and Shire.

1. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, et al. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686-693.

2. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

3. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus statement on high-dose antipsychotic medication. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/CR138.pdf. Published May 2006. Accessed March 26, 2013.

4. Pinninti NR, Mago R, de Leon J. Coffee, cigarettes and meds: what are the metabolic effects? Psychiatric Times. 2005;22(6):20-23.

5. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

6. Citrome L. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: what can we do about it? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(6):52-58.

7. Volz A, Khorsand V, Gillies D, et al. Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1): CD006391.

1. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, et al. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686-693.

2. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

3. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus statement on high-dose antipsychotic medication. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/CR138.pdf. Published May 2006. Accessed March 26, 2013.

4. Pinninti NR, Mago R, de Leon J. Coffee, cigarettes and meds: what are the metabolic effects? Psychiatric Times. 2005;22(6):20-23.

5. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

6. Citrome L. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: what can we do about it? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(6):52-58.

7. Volz A, Khorsand V, Gillies D, et al. Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1): CD006391.

Auditory musical hallucinations: When a patient complains, ‘I hear a symphony!’

Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations—hearing singing voices, musical tones, song lyrics, or instrumental music—occur in >20% of outpatients who have a diagnosis of an anxiety, affective, or schizophrenic disorder, with the highest prevalence (41%) in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).1 OCD comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders increases the frequency of auditory musical hallucinations. Auditory musical hallucinations mainly affect older (mean age, 61.5 years) females who have tinnitus and severe, high-frequency, sensorineural hearing loss.1 Auditory musical hallucinations occur in psychiatric diseases, ictal states of complex partial seizures, abnormalities of the auditory cortex, thalamic infarcts, subarachnoid hemorrhage, tumors of the brain stem, intoxication, and progressive deafness.1,2

What patients report hearing

Some patients identify 1 musical instrument that dominates others. The musical tones are reported to have a vibrating quality, similar to the sound produced by blowing air through a paper-covered comb. Some patients hear singing voices, predominantly deep in tone, although the words usually are not clear.

Patients with auditory musical hallucinations associated with deafness may not have dementia or psychosis. Both sensorineural and conductive involvement indicates a mixed type of deafness. Pure tone audiograms show a bilateral loss of >30 decibels, affecting the higher and lower ranges.2,3 Cerebral atrophy and microangiopathic changes are common co-occurring findings on MRI.

Treatment options

Reassure your patient that the experience is not necessarily associated with a psychotic disorder. Perform a complete history, physical, and neurologic examination. Rule out unilateral symptoms, tinnitus, and hearing loss. If she (he) is experiencing unilateral symptoms, pulsatile tinnitus, unilateral hearing loss, and a constant feeling of unsteadiness, further evaluation is necessary to exclude underlying pathology. Treating concurrent insomnia, depression, or anxiety might resolve the hallucinations.4

Nonpharmacotherapeutic treatments include hearing amplification, and masking tinnitus with a hearing aid emitting low-volume music or sounds of nature (ie, rainfall).4 Two cases have reported successful carbamazepine therapy; 2 other cases demonstrated success with clomipramine.5 Frequently, symptoms spontaneously remit.

Consider electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with musical hallucinations that are refractory to medical treatment and cause distress; 3 patients with concurrent major depressive disorder showed improvement after ECT.6 Antipsychotics are not recommended as first-line treatment.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Hermesh H, Konas S, Shiloh R, et al. Musical hallucinations: prevalence in psychotic and nonpsychotic outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):191-197.

2. Schakenraad SM, Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MG. Musical hallucinations in psychiatric patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(4):394-397.

3. Evers S, Ellger T. The clinical spectrum of musical hallucinations. J Neurol Sci. 2004;227(1):55-65.

4. Zegarra NM, Cuetter AC, Briones DF, et al. Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations in elderly persons with progressive deafness. Clin Geriatr. 2007;15(11):33-37.

5. Mahendran R. The psychopathology of musical hallucinations. Singapore Med J. 2007;48(2):e68-e70.