User login

6 ‘M’s to keep in mind when you next see a patient with anorexia nervosa

Anorexia nervosa is associated with comorbid psychiatric disorders, severe physical complications, and high mortality. To help you remember important clinical information when working with patients with anorexia, we propose this “6 M” model for screening, treatment, and prognosis.

Monitor closely. Anorexia can go undiagnosed and untreated for years. During your patients’ office visits, ask about body image, exercise habits, and menstrual irregularities, especially when seeing at-risk youth. During physical examination, reluctance to be weighed, vital sign abnormalities (eg, orthostatic hypotension, variability in pulse), skin abnormalities (lanugo hair, dryness), and marks indicating self-harm can serve as diagnostic indicators. Consider hospitalization for patients at <75% of their ideal body weight, who refuse to eat, or who show vital signs and laboratory abnormalities.

Media. By providing information on healthy eating and nutrition, the Internet can be an excellent resource for people with an eating disorder; however, you should also be aware of the impact of so-called pro-ana Web sites. People with anorexia use these Web sites to discuss their illness, but the sites sometimes glorify eating disorders as a lifestyle choice, and can be a place to share tips and tricks on extreme dieting, and might promote what is known as “thinspiration” in popular culture.

Meals. The American Dietetic Association recommends that anorexic patients begin oral intake at no more than 30 to 40 kcal/kg/day, and then gradually increase it, with a weight gain goal of 0.5 to 1 lb per week.

This graduated weight gain is done to prevent refeeding syndrome. After chronic starvation, intracellular phosphate stores are depleted and once carbohydrate intake resumes, insulin release causes phosphate to enter cells, thereby leading to hypophosphatemia. This electrolyte abnormality can result in cardiac failure. As a result, consider regular monitoring of phosphate levels, especially during the first week of reintroducing food.

Multimodal therapy. Despite being notoriously difficult to treat, patients with anorexia might respond to psychotherapy—especially family therapy—with an increased remission rate and faster return to health, compared with other forms of treatment. With a multimodal regimen involving proper refeeding techniques, family therapy, and medications as appropriate, recovery is possible.

Medications might be a helpful adjunct in patients who do not gain weight despite psychotherapy and proper nutritional measures. For example:

• There is some research on medications such as olanzapine and anxiolytics for treating anorexia.

• A low-dose anxiolytic might benefit patients with preprandial anxiety.

• Comorbid psychiatric disorders might improve during treatment of the eating disorder.

• Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and second-generation antipsychotics might help manage severe comorbid psychiatric disorders.

Because of low body weight and altered plasma protein binding, start medications at a low dosage. The risk of adverse effects can increase because more “free” medication is available. Consider avoiding medications such as bupropion and tricyclic antidepressants, because they carry an increased risk of seizures and cardiac effects, respectively.

Morbidity and mortality. Untreated anorexia has the highest mortality among psychiatric disorders: approximately 5.1 deaths for every 1,000 people.1 Recent meta-analyses show that patients with anorexia may have a 5.86 times greater risk of death than the general population.1 Serious sequelae include cardiac complications; osteoporosis; infertility; and comorbid psychiatric conditions such as substance abuse, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.2

1. Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, et al. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011; 68(7):724-731.

2. Yager J, Andersen AE. Clinical practice. Anorexia nervosa. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(14):1481-1488.

Anorexia nervosa is associated with comorbid psychiatric disorders, severe physical complications, and high mortality. To help you remember important clinical information when working with patients with anorexia, we propose this “6 M” model for screening, treatment, and prognosis.

Monitor closely. Anorexia can go undiagnosed and untreated for years. During your patients’ office visits, ask about body image, exercise habits, and menstrual irregularities, especially when seeing at-risk youth. During physical examination, reluctance to be weighed, vital sign abnormalities (eg, orthostatic hypotension, variability in pulse), skin abnormalities (lanugo hair, dryness), and marks indicating self-harm can serve as diagnostic indicators. Consider hospitalization for patients at <75% of their ideal body weight, who refuse to eat, or who show vital signs and laboratory abnormalities.

Media. By providing information on healthy eating and nutrition, the Internet can be an excellent resource for people with an eating disorder; however, you should also be aware of the impact of so-called pro-ana Web sites. People with anorexia use these Web sites to discuss their illness, but the sites sometimes glorify eating disorders as a lifestyle choice, and can be a place to share tips and tricks on extreme dieting, and might promote what is known as “thinspiration” in popular culture.

Meals. The American Dietetic Association recommends that anorexic patients begin oral intake at no more than 30 to 40 kcal/kg/day, and then gradually increase it, with a weight gain goal of 0.5 to 1 lb per week.

This graduated weight gain is done to prevent refeeding syndrome. After chronic starvation, intracellular phosphate stores are depleted and once carbohydrate intake resumes, insulin release causes phosphate to enter cells, thereby leading to hypophosphatemia. This electrolyte abnormality can result in cardiac failure. As a result, consider regular monitoring of phosphate levels, especially during the first week of reintroducing food.

Multimodal therapy. Despite being notoriously difficult to treat, patients with anorexia might respond to psychotherapy—especially family therapy—with an increased remission rate and faster return to health, compared with other forms of treatment. With a multimodal regimen involving proper refeeding techniques, family therapy, and medications as appropriate, recovery is possible.

Medications might be a helpful adjunct in patients who do not gain weight despite psychotherapy and proper nutritional measures. For example:

• There is some research on medications such as olanzapine and anxiolytics for treating anorexia.

• A low-dose anxiolytic might benefit patients with preprandial anxiety.

• Comorbid psychiatric disorders might improve during treatment of the eating disorder.

• Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and second-generation antipsychotics might help manage severe comorbid psychiatric disorders.

Because of low body weight and altered plasma protein binding, start medications at a low dosage. The risk of adverse effects can increase because more “free” medication is available. Consider avoiding medications such as bupropion and tricyclic antidepressants, because they carry an increased risk of seizures and cardiac effects, respectively.

Morbidity and mortality. Untreated anorexia has the highest mortality among psychiatric disorders: approximately 5.1 deaths for every 1,000 people.1 Recent meta-analyses show that patients with anorexia may have a 5.86 times greater risk of death than the general population.1 Serious sequelae include cardiac complications; osteoporosis; infertility; and comorbid psychiatric conditions such as substance abuse, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.2

Anorexia nervosa is associated with comorbid psychiatric disorders, severe physical complications, and high mortality. To help you remember important clinical information when working with patients with anorexia, we propose this “6 M” model for screening, treatment, and prognosis.

Monitor closely. Anorexia can go undiagnosed and untreated for years. During your patients’ office visits, ask about body image, exercise habits, and menstrual irregularities, especially when seeing at-risk youth. During physical examination, reluctance to be weighed, vital sign abnormalities (eg, orthostatic hypotension, variability in pulse), skin abnormalities (lanugo hair, dryness), and marks indicating self-harm can serve as diagnostic indicators. Consider hospitalization for patients at <75% of their ideal body weight, who refuse to eat, or who show vital signs and laboratory abnormalities.

Media. By providing information on healthy eating and nutrition, the Internet can be an excellent resource for people with an eating disorder; however, you should also be aware of the impact of so-called pro-ana Web sites. People with anorexia use these Web sites to discuss their illness, but the sites sometimes glorify eating disorders as a lifestyle choice, and can be a place to share tips and tricks on extreme dieting, and might promote what is known as “thinspiration” in popular culture.

Meals. The American Dietetic Association recommends that anorexic patients begin oral intake at no more than 30 to 40 kcal/kg/day, and then gradually increase it, with a weight gain goal of 0.5 to 1 lb per week.

This graduated weight gain is done to prevent refeeding syndrome. After chronic starvation, intracellular phosphate stores are depleted and once carbohydrate intake resumes, insulin release causes phosphate to enter cells, thereby leading to hypophosphatemia. This electrolyte abnormality can result in cardiac failure. As a result, consider regular monitoring of phosphate levels, especially during the first week of reintroducing food.

Multimodal therapy. Despite being notoriously difficult to treat, patients with anorexia might respond to psychotherapy—especially family therapy—with an increased remission rate and faster return to health, compared with other forms of treatment. With a multimodal regimen involving proper refeeding techniques, family therapy, and medications as appropriate, recovery is possible.

Medications might be a helpful adjunct in patients who do not gain weight despite psychotherapy and proper nutritional measures. For example:

• There is some research on medications such as olanzapine and anxiolytics for treating anorexia.

• A low-dose anxiolytic might benefit patients with preprandial anxiety.

• Comorbid psychiatric disorders might improve during treatment of the eating disorder.

• Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and second-generation antipsychotics might help manage severe comorbid psychiatric disorders.

Because of low body weight and altered plasma protein binding, start medications at a low dosage. The risk of adverse effects can increase because more “free” medication is available. Consider avoiding medications such as bupropion and tricyclic antidepressants, because they carry an increased risk of seizures and cardiac effects, respectively.

Morbidity and mortality. Untreated anorexia has the highest mortality among psychiatric disorders: approximately 5.1 deaths for every 1,000 people.1 Recent meta-analyses show that patients with anorexia may have a 5.86 times greater risk of death than the general population.1 Serious sequelae include cardiac complications; osteoporosis; infertility; and comorbid psychiatric conditions such as substance abuse, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.2

1. Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, et al. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011; 68(7):724-731.

2. Yager J, Andersen AE. Clinical practice. Anorexia nervosa. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(14):1481-1488.

1. Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, et al. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011; 68(7):724-731.

2. Yager J, Andersen AE. Clinical practice. Anorexia nervosa. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(14):1481-1488.

Obtaining informed consent for research in an acute inpatient psychiatric setting

Conducting clinical research with patients in an acute inpatient psychiatric setting raises possible ethical difficulties, in part because of concern about patients’ ability to give informed consent to participate in research.

We propose the acronym CHECK (for capacity, heredity, ethics, coercion-free, and knowledge) to provide researchers with guidance on the process of addressing informed consent in an acute inpatient setting.

Capacity. Ensure that the patient has the decisional capacity to:

• understand disclosed information about proposed research

• appreciate the impact of participation and nonparticipation

• reason about risks and benefits of participation

• communicate a consistent choice.1

The standards for disclosing information to a potential participant are higher for research than in clinical practice, because patients must understand and accept randomization, placebo control, blinding, and possible exposure to non-approved treatment interventions—yet there is a balance regarding how much information is necessary for consent in a given situation.2

Be mindful that the severity of the patient’s psychiatric illness can impair understanding and insight that might preclude giving informed consent (eg, major depression can produce a slowing of intellectual processes; mania can display distractibility; schizophrenia can compromise decisional capacity because of disorganized thinking or delusions; and neurocognitive disorders can affect the ability to process information).

The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research, designed as an aid to assessing capacity, has the most empirical support, although other instruments might be equally or better suited to some situations.1

Heredity. When undertaking human genetic and genomic research, create a precise, robust consent process. Genome sequencing studies can reveal information about the health of patients and their families, provoking discussion about appropriate protections for such data. Informed consent should include:

• how the data will be used now and in the future

• the extent to which patients can control future use of the data

• benefits and risks of participation, including the potential for unknown future risks

• what information, including incidental findings, will be returned to the patient

• what methods will be used to safeguard genetic testing data.3

Ethics. Researchers are bound by a code of ethics:

• Patients have the right to decline participation in research and to withdraw at any stage without prejudice; exclusion recognizes the need to protect those who may be incapable of exercising that right.2 Avoid research with dissenting patients, whether or not they are considered capable.2 Do not routinely invite treatment-refusing patients to participate in research projects, other than in extraordinary circumstances; eg, treatment refusing patients who have been adjudicated as “incompetent,” in which case the court-appointed surrogate decision-maker could be approached for informed consent. You should routinely seek a legal opinion in such a circumstance.

• Unless the research is examining interventions for acute and disabling psychiatric illness, consent should not be sought until patients are well enough to make an informed decision. However, clinical assessment is always needed (despite psychiatric illness category) because it cannot be assumed that psychiatric patients are unable to make such a decision (eg, in some cases, substance abuse should not automatically eliminate a participant, as long as the patient retains adequate cognitive status for informed consent).

• Capacity for consent is not “all-or-nothing,” but is specific to the research paradigm. In cases of impaired decisional capacity, researchers can obtain informed consent by obtaining agreement of family, legal representative, or caregiver; therefore, research with assenting adults, who are nonetheless incapable, is unlikely to be regarded as unethical.2

Coercion-free. Avoid covert pressures:

• Ensure that consent is given freely without coercion or duress. This is important if the participant has a physician-patient relationship with a member of the research team. Exercise caution when research methods involve physical contact. Such contact, in incapable patients—even those who assent— could create a medico-legal conflict (eg, taking a blood sample specific for research purposes without consent could result in a charge of battery).2 When in doubt, seek a legal opinion before enrolling decisionally incapable patients (and/or those adjudicated as incompetent) in research trials.

• Consider that participation be initiated by a third party (eg, an approach from a staff member who is not part of their care team and not involved in the research to ask if the potential participant has made a decision that he wants to have communicated to the researcher4).

• Require that a family member, legal representative, or caregiver be present at the time of consent with decisionally incapacitated patients.

Knowledge. The participant must be given adequate information about the project. Understand consent as an ongoing process occurring within a specific context:

• Give participants a fair explanation of the proposed project, the risks and benefits that might ensue, and, when applicable, what appropriate procedures may be offered if the participant experiences discomfort. If a study is to be blinded, patients must understand and appreciate that they could receive no benefit at all.

• Consider the importance of using appropriate language, repeating information, ensuring adequate time for questions and answers, and providing written material to the patient.2 Avoid leaving the patient alone with an information sheet to avoid coercion, because this risks denying patients the opportunity to participate because they lack the occasion to receive information and ask questions.4 Rather, go over the research consent document item by item with the patient in an iterative process, encouraging questions. Ensure private individual discussion between study team members and the patient to address questions related to the study.4

• Reapproach patients to discuss or revisit consent as needed, because their capacity to provide informed consent may vary over time. This is especially important in CNS illnesses, in which the level of cognitive function is variable. An item such as “consent status” for each encounter can be added to the checklist.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Dunn LB, Nowrangi MA, Palmer BW, et al. Assessing decisional capacity for clinical research or treatment: a review of instruments. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(8): 1323-1334.

2. Fulford KW, Howse K. Ethics of research with psychiatric patients: principles, problems and the primary responsibilities of researchers. J Med Ethics. 1993;19(2):85-91.

3. Kuehn BM. Growing use of genomic data reveals need to improve consent and privacy standards. JAMA. 2013; 309(20):2083-2084.

4. Cameron J, Hart A. Ethical issues in obtaining informed consent for research from those recovering from acute mental health problems: a commentary. Research Ethics Review. 2007;3(4):127-129.

Conducting clinical research with patients in an acute inpatient psychiatric setting raises possible ethical difficulties, in part because of concern about patients’ ability to give informed consent to participate in research.

We propose the acronym CHECK (for capacity, heredity, ethics, coercion-free, and knowledge) to provide researchers with guidance on the process of addressing informed consent in an acute inpatient setting.

Capacity. Ensure that the patient has the decisional capacity to:

• understand disclosed information about proposed research

• appreciate the impact of participation and nonparticipation

• reason about risks and benefits of participation

• communicate a consistent choice.1

The standards for disclosing information to a potential participant are higher for research than in clinical practice, because patients must understand and accept randomization, placebo control, blinding, and possible exposure to non-approved treatment interventions—yet there is a balance regarding how much information is necessary for consent in a given situation.2

Be mindful that the severity of the patient’s psychiatric illness can impair understanding and insight that might preclude giving informed consent (eg, major depression can produce a slowing of intellectual processes; mania can display distractibility; schizophrenia can compromise decisional capacity because of disorganized thinking or delusions; and neurocognitive disorders can affect the ability to process information).

The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research, designed as an aid to assessing capacity, has the most empirical support, although other instruments might be equally or better suited to some situations.1

Heredity. When undertaking human genetic and genomic research, create a precise, robust consent process. Genome sequencing studies can reveal information about the health of patients and their families, provoking discussion about appropriate protections for such data. Informed consent should include:

• how the data will be used now and in the future

• the extent to which patients can control future use of the data

• benefits and risks of participation, including the potential for unknown future risks

• what information, including incidental findings, will be returned to the patient

• what methods will be used to safeguard genetic testing data.3

Ethics. Researchers are bound by a code of ethics:

• Patients have the right to decline participation in research and to withdraw at any stage without prejudice; exclusion recognizes the need to protect those who may be incapable of exercising that right.2 Avoid research with dissenting patients, whether or not they are considered capable.2 Do not routinely invite treatment-refusing patients to participate in research projects, other than in extraordinary circumstances; eg, treatment refusing patients who have been adjudicated as “incompetent,” in which case the court-appointed surrogate decision-maker could be approached for informed consent. You should routinely seek a legal opinion in such a circumstance.

• Unless the research is examining interventions for acute and disabling psychiatric illness, consent should not be sought until patients are well enough to make an informed decision. However, clinical assessment is always needed (despite psychiatric illness category) because it cannot be assumed that psychiatric patients are unable to make such a decision (eg, in some cases, substance abuse should not automatically eliminate a participant, as long as the patient retains adequate cognitive status for informed consent).

• Capacity for consent is not “all-or-nothing,” but is specific to the research paradigm. In cases of impaired decisional capacity, researchers can obtain informed consent by obtaining agreement of family, legal representative, or caregiver; therefore, research with assenting adults, who are nonetheless incapable, is unlikely to be regarded as unethical.2

Coercion-free. Avoid covert pressures:

• Ensure that consent is given freely without coercion or duress. This is important if the participant has a physician-patient relationship with a member of the research team. Exercise caution when research methods involve physical contact. Such contact, in incapable patients—even those who assent— could create a medico-legal conflict (eg, taking a blood sample specific for research purposes without consent could result in a charge of battery).2 When in doubt, seek a legal opinion before enrolling decisionally incapable patients (and/or those adjudicated as incompetent) in research trials.

• Consider that participation be initiated by a third party (eg, an approach from a staff member who is not part of their care team and not involved in the research to ask if the potential participant has made a decision that he wants to have communicated to the researcher4).

• Require that a family member, legal representative, or caregiver be present at the time of consent with decisionally incapacitated patients.

Knowledge. The participant must be given adequate information about the project. Understand consent as an ongoing process occurring within a specific context:

• Give participants a fair explanation of the proposed project, the risks and benefits that might ensue, and, when applicable, what appropriate procedures may be offered if the participant experiences discomfort. If a study is to be blinded, patients must understand and appreciate that they could receive no benefit at all.

• Consider the importance of using appropriate language, repeating information, ensuring adequate time for questions and answers, and providing written material to the patient.2 Avoid leaving the patient alone with an information sheet to avoid coercion, because this risks denying patients the opportunity to participate because they lack the occasion to receive information and ask questions.4 Rather, go over the research consent document item by item with the patient in an iterative process, encouraging questions. Ensure private individual discussion between study team members and the patient to address questions related to the study.4

• Reapproach patients to discuss or revisit consent as needed, because their capacity to provide informed consent may vary over time. This is especially important in CNS illnesses, in which the level of cognitive function is variable. An item such as “consent status” for each encounter can be added to the checklist.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Conducting clinical research with patients in an acute inpatient psychiatric setting raises possible ethical difficulties, in part because of concern about patients’ ability to give informed consent to participate in research.

We propose the acronym CHECK (for capacity, heredity, ethics, coercion-free, and knowledge) to provide researchers with guidance on the process of addressing informed consent in an acute inpatient setting.

Capacity. Ensure that the patient has the decisional capacity to:

• understand disclosed information about proposed research

• appreciate the impact of participation and nonparticipation

• reason about risks and benefits of participation

• communicate a consistent choice.1

The standards for disclosing information to a potential participant are higher for research than in clinical practice, because patients must understand and accept randomization, placebo control, blinding, and possible exposure to non-approved treatment interventions—yet there is a balance regarding how much information is necessary for consent in a given situation.2

Be mindful that the severity of the patient’s psychiatric illness can impair understanding and insight that might preclude giving informed consent (eg, major depression can produce a slowing of intellectual processes; mania can display distractibility; schizophrenia can compromise decisional capacity because of disorganized thinking or delusions; and neurocognitive disorders can affect the ability to process information).

The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research, designed as an aid to assessing capacity, has the most empirical support, although other instruments might be equally or better suited to some situations.1

Heredity. When undertaking human genetic and genomic research, create a precise, robust consent process. Genome sequencing studies can reveal information about the health of patients and their families, provoking discussion about appropriate protections for such data. Informed consent should include:

• how the data will be used now and in the future

• the extent to which patients can control future use of the data

• benefits and risks of participation, including the potential for unknown future risks

• what information, including incidental findings, will be returned to the patient

• what methods will be used to safeguard genetic testing data.3

Ethics. Researchers are bound by a code of ethics:

• Patients have the right to decline participation in research and to withdraw at any stage without prejudice; exclusion recognizes the need to protect those who may be incapable of exercising that right.2 Avoid research with dissenting patients, whether or not they are considered capable.2 Do not routinely invite treatment-refusing patients to participate in research projects, other than in extraordinary circumstances; eg, treatment refusing patients who have been adjudicated as “incompetent,” in which case the court-appointed surrogate decision-maker could be approached for informed consent. You should routinely seek a legal opinion in such a circumstance.

• Unless the research is examining interventions for acute and disabling psychiatric illness, consent should not be sought until patients are well enough to make an informed decision. However, clinical assessment is always needed (despite psychiatric illness category) because it cannot be assumed that psychiatric patients are unable to make such a decision (eg, in some cases, substance abuse should not automatically eliminate a participant, as long as the patient retains adequate cognitive status for informed consent).

• Capacity for consent is not “all-or-nothing,” but is specific to the research paradigm. In cases of impaired decisional capacity, researchers can obtain informed consent by obtaining agreement of family, legal representative, or caregiver; therefore, research with assenting adults, who are nonetheless incapable, is unlikely to be regarded as unethical.2

Coercion-free. Avoid covert pressures:

• Ensure that consent is given freely without coercion or duress. This is important if the participant has a physician-patient relationship with a member of the research team. Exercise caution when research methods involve physical contact. Such contact, in incapable patients—even those who assent— could create a medico-legal conflict (eg, taking a blood sample specific for research purposes without consent could result in a charge of battery).2 When in doubt, seek a legal opinion before enrolling decisionally incapable patients (and/or those adjudicated as incompetent) in research trials.

• Consider that participation be initiated by a third party (eg, an approach from a staff member who is not part of their care team and not involved in the research to ask if the potential participant has made a decision that he wants to have communicated to the researcher4).

• Require that a family member, legal representative, or caregiver be present at the time of consent with decisionally incapacitated patients.

Knowledge. The participant must be given adequate information about the project. Understand consent as an ongoing process occurring within a specific context:

• Give participants a fair explanation of the proposed project, the risks and benefits that might ensue, and, when applicable, what appropriate procedures may be offered if the participant experiences discomfort. If a study is to be blinded, patients must understand and appreciate that they could receive no benefit at all.

• Consider the importance of using appropriate language, repeating information, ensuring adequate time for questions and answers, and providing written material to the patient.2 Avoid leaving the patient alone with an information sheet to avoid coercion, because this risks denying patients the opportunity to participate because they lack the occasion to receive information and ask questions.4 Rather, go over the research consent document item by item with the patient in an iterative process, encouraging questions. Ensure private individual discussion between study team members and the patient to address questions related to the study.4

• Reapproach patients to discuss or revisit consent as needed, because their capacity to provide informed consent may vary over time. This is especially important in CNS illnesses, in which the level of cognitive function is variable. An item such as “consent status” for each encounter can be added to the checklist.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Dunn LB, Nowrangi MA, Palmer BW, et al. Assessing decisional capacity for clinical research or treatment: a review of instruments. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(8): 1323-1334.

2. Fulford KW, Howse K. Ethics of research with psychiatric patients: principles, problems and the primary responsibilities of researchers. J Med Ethics. 1993;19(2):85-91.

3. Kuehn BM. Growing use of genomic data reveals need to improve consent and privacy standards. JAMA. 2013; 309(20):2083-2084.

4. Cameron J, Hart A. Ethical issues in obtaining informed consent for research from those recovering from acute mental health problems: a commentary. Research Ethics Review. 2007;3(4):127-129.

1. Dunn LB, Nowrangi MA, Palmer BW, et al. Assessing decisional capacity for clinical research or treatment: a review of instruments. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(8): 1323-1334.

2. Fulford KW, Howse K. Ethics of research with psychiatric patients: principles, problems and the primary responsibilities of researchers. J Med Ethics. 1993;19(2):85-91.

3. Kuehn BM. Growing use of genomic data reveals need to improve consent and privacy standards. JAMA. 2013; 309(20):2083-2084.

4. Cameron J, Hart A. Ethical issues in obtaining informed consent for research from those recovering from acute mental health problems: a commentary. Research Ethics Review. 2007;3(4):127-129.

Bicytopenia: Adverse effect of risperidone

Hematologic abnormalities, such as leukopenia, agranulocytosis, and thrombocytopenia, can be life-threatening adverse reactions to atypical antipsychotics. Although clozapine has the highest risk of leukopenia and neutropenia, these side effects also have been associated with other atypical antipsychotics, including risperidone, olanzapine, ziprasidone, paliperdione, and quetiapine. Risperdone-induced leukopenia has been reported,1,2 but risperidone-

induced bicytopenia— that is, leukopenia/ thrombocytopenia—is rare.

Case

Mr. A, age 25, is an African American man admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit for management of acute psychotic symptoms. He has been taking risperidone, 4 mg/d, for the past 6 months, although his adherence to the regimen is questionable. Baseline blood count shows a white blood cell (WBC) count of 4,400/μL with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 1,900/μL and a platelet count

160×103/μL. A few days after restarting risperidone, repeat blood count shows a drop in the WBC count to 2,900/μL, with an ANC of 900/μL and a platelet count of 130×103/μL.

Mr. A’s physical examination is normal, he does not have any signs or symptoms of infection, and additional lab tests are negative. Risperidone is considered as a possible cause of bicytopenia and is discontinued. Mr. A agrees to start treatment with aripiprazole, 10 mg/d. In next 10 days, the WBC count increases to 6,000/μL. The ANC at 3,100/μL and platelets at 150×103/μL remain stable throughout hospitalization. The slowly increasing WBC count after stopping risperidone is highly suggestive that this agent caused Mr. A’s bicytopenia.

Differential diagnosis

Bone-marrow suppression is associated with first- and second-generation antipsychotics. Blood dyscrasia is a concern in clinical psychiatry because hematologic abnormalities can be life-threatening, requiring close monitoring of the blood count for patients taking an antipsychotic. It is important, therefore, to consider medication side effects in the differential diagnosis of >1 hematologic abnormalities in these patients.

Precise pathophysiologic understanding of the hematologic side effects of antipsychotics is lacking, although different mechanisms of action have been proposed.3 Possible mechanisms when a patient is taking clozapine or olanzapine include:

• direct toxic effect of the drug on bone marrow

• increased peripheral destruction

• oxidative stress induced by unstable metabolites.

There is not enough evidence, however, to identify risperidone’s mechanism of action on blood cells.

Aripiprazole might be a useful alternative when another antipsychotic causes leukopenia and neutropenia. In addition to regularly monitoring the blood cell count during antipsychotic treatment, the neutrophil and platelet counts should be monitored.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Manfredi G, Solfanelli A, Dimitri G, et al. Risperidone-induced leukopenia: a case report and brief review of literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(1):102.e3-102.e6.

2. Cosar B, Taner ME, Eser HY, et al. Does switching to another antipsychotic in patients with clozapine-associated granulocytopenia solve the problem? Case series of 18 patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(2):169-173.

3. Nooijen PM, Carvalho F, Flanagan RJ. Haematological toxicity of clozapine and some other drugs used in psychiatry. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(2):112-119.

Hematologic abnormalities, such as leukopenia, agranulocytosis, and thrombocytopenia, can be life-threatening adverse reactions to atypical antipsychotics. Although clozapine has the highest risk of leukopenia and neutropenia, these side effects also have been associated with other atypical antipsychotics, including risperidone, olanzapine, ziprasidone, paliperdione, and quetiapine. Risperdone-induced leukopenia has been reported,1,2 but risperidone-

induced bicytopenia— that is, leukopenia/ thrombocytopenia—is rare.

Case

Mr. A, age 25, is an African American man admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit for management of acute psychotic symptoms. He has been taking risperidone, 4 mg/d, for the past 6 months, although his adherence to the regimen is questionable. Baseline blood count shows a white blood cell (WBC) count of 4,400/μL with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 1,900/μL and a platelet count

160×103/μL. A few days after restarting risperidone, repeat blood count shows a drop in the WBC count to 2,900/μL, with an ANC of 900/μL and a platelet count of 130×103/μL.

Mr. A’s physical examination is normal, he does not have any signs or symptoms of infection, and additional lab tests are negative. Risperidone is considered as a possible cause of bicytopenia and is discontinued. Mr. A agrees to start treatment with aripiprazole, 10 mg/d. In next 10 days, the WBC count increases to 6,000/μL. The ANC at 3,100/μL and platelets at 150×103/μL remain stable throughout hospitalization. The slowly increasing WBC count after stopping risperidone is highly suggestive that this agent caused Mr. A’s bicytopenia.

Differential diagnosis

Bone-marrow suppression is associated with first- and second-generation antipsychotics. Blood dyscrasia is a concern in clinical psychiatry because hematologic abnormalities can be life-threatening, requiring close monitoring of the blood count for patients taking an antipsychotic. It is important, therefore, to consider medication side effects in the differential diagnosis of >1 hematologic abnormalities in these patients.

Precise pathophysiologic understanding of the hematologic side effects of antipsychotics is lacking, although different mechanisms of action have been proposed.3 Possible mechanisms when a patient is taking clozapine or olanzapine include:

• direct toxic effect of the drug on bone marrow

• increased peripheral destruction

• oxidative stress induced by unstable metabolites.

There is not enough evidence, however, to identify risperidone’s mechanism of action on blood cells.

Aripiprazole might be a useful alternative when another antipsychotic causes leukopenia and neutropenia. In addition to regularly monitoring the blood cell count during antipsychotic treatment, the neutrophil and platelet counts should be monitored.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Hematologic abnormalities, such as leukopenia, agranulocytosis, and thrombocytopenia, can be life-threatening adverse reactions to atypical antipsychotics. Although clozapine has the highest risk of leukopenia and neutropenia, these side effects also have been associated with other atypical antipsychotics, including risperidone, olanzapine, ziprasidone, paliperdione, and quetiapine. Risperdone-induced leukopenia has been reported,1,2 but risperidone-

induced bicytopenia— that is, leukopenia/ thrombocytopenia—is rare.

Case

Mr. A, age 25, is an African American man admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit for management of acute psychotic symptoms. He has been taking risperidone, 4 mg/d, for the past 6 months, although his adherence to the regimen is questionable. Baseline blood count shows a white blood cell (WBC) count of 4,400/μL with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 1,900/μL and a platelet count

160×103/μL. A few days after restarting risperidone, repeat blood count shows a drop in the WBC count to 2,900/μL, with an ANC of 900/μL and a platelet count of 130×103/μL.

Mr. A’s physical examination is normal, he does not have any signs or symptoms of infection, and additional lab tests are negative. Risperidone is considered as a possible cause of bicytopenia and is discontinued. Mr. A agrees to start treatment with aripiprazole, 10 mg/d. In next 10 days, the WBC count increases to 6,000/μL. The ANC at 3,100/μL and platelets at 150×103/μL remain stable throughout hospitalization. The slowly increasing WBC count after stopping risperidone is highly suggestive that this agent caused Mr. A’s bicytopenia.

Differential diagnosis

Bone-marrow suppression is associated with first- and second-generation antipsychotics. Blood dyscrasia is a concern in clinical psychiatry because hematologic abnormalities can be life-threatening, requiring close monitoring of the blood count for patients taking an antipsychotic. It is important, therefore, to consider medication side effects in the differential diagnosis of >1 hematologic abnormalities in these patients.

Precise pathophysiologic understanding of the hematologic side effects of antipsychotics is lacking, although different mechanisms of action have been proposed.3 Possible mechanisms when a patient is taking clozapine or olanzapine include:

• direct toxic effect of the drug on bone marrow

• increased peripheral destruction

• oxidative stress induced by unstable metabolites.

There is not enough evidence, however, to identify risperidone’s mechanism of action on blood cells.

Aripiprazole might be a useful alternative when another antipsychotic causes leukopenia and neutropenia. In addition to regularly monitoring the blood cell count during antipsychotic treatment, the neutrophil and platelet counts should be monitored.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Manfredi G, Solfanelli A, Dimitri G, et al. Risperidone-induced leukopenia: a case report and brief review of literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(1):102.e3-102.e6.

2. Cosar B, Taner ME, Eser HY, et al. Does switching to another antipsychotic in patients with clozapine-associated granulocytopenia solve the problem? Case series of 18 patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(2):169-173.

3. Nooijen PM, Carvalho F, Flanagan RJ. Haematological toxicity of clozapine and some other drugs used in psychiatry. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(2):112-119.

1. Manfredi G, Solfanelli A, Dimitri G, et al. Risperidone-induced leukopenia: a case report and brief review of literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(1):102.e3-102.e6.

2. Cosar B, Taner ME, Eser HY, et al. Does switching to another antipsychotic in patients with clozapine-associated granulocytopenia solve the problem? Case series of 18 patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(2):169-173.

3. Nooijen PM, Carvalho F, Flanagan RJ. Haematological toxicity of clozapine and some other drugs used in psychiatry. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(2):112-119.

Pseudobulbar affect: No laughing matter

Pathological laughter and crying— pseudobulbar affect (PBA)—is a disorder of emotional expression characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of laughter or crying without an environmental trigger. Persons with PBA are at an increased risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms associated with an inappropriate outburst of emotion1; such emotional acts might be incongruent with their underlying emotional state.

When should you consider PBA?

Consider PBA in patients with new-onset emotional lability in the presence of certain neurologic conditions. PBA is most common in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and stroke, in which an incidence of >50% has been estimated.2 Other conditions associated with PBA include Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, normal pressure hydrocephalus, progressive supranuclear palsy, Wilson disease, and neurosyphilis.3

Avoid PBA misdiagnosis

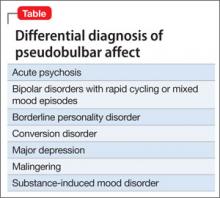

Depression is the most common PBA misdiagnosis (Table). However, many clinical features distinguish PBA episodes from depressive symptoms; the most prominent difference is duration. Depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, typically last weeks to months, but a PBA episode lasts seconds or minutes. In addition, crying, as a symptom of PBA, might be unrelated or exaggerated relative to the patient’s mood, but crying is congruent with subjective mood in depression. Other symptoms of depression—fatigue, anorexia, insomnia, anhedonia, and feelings of hopelessness and guilt— are not associated with pseudobulbar affect.

PBA also can be differentiated from bipolar disorder (BD) with rapid cycling or mixed mood episodes because of PBA’s relatively brief duration of laughing or crying episodes—with no mood disturbance between episodes—compared with the sustained changes in mood, cognition, and behavior seen in BD.

Options for treating PBA

Serotonergic therapies, such as amitriptyline and fluoxetine, may exert effects by increasing serotonin in the synapse; dextromethorphan may act via antiglutamatergic effects at N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors and sigma-1 receptors.4 Dextromethorphan binding is most prominent in the brainstem and cerebellum, brain areas known to be rich in sigma-1 receptors and key sites implicated in the pathophysiology of PBA. Although the precise mechanisms by which dextromethorphan ameliorates PBA are unknown, modulation of excessive glutamatergic transmission within corticopontine-cerebellar circuits may contribute to its benefits.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Tateno A, Jorge RE, Robinson RG. Pathological laughing and crying following traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16(4):426-434.

2. Miller A, Pratt H, Schiffer RB. Pseudobulbar affect: the spectrum of clinical presentations, etiologies and treatments. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(7):1077-1088.

3. Haiman G, Pratt H, Miller A. Brain responses to verbal stimuli among multiple sclerosis patients with pseudobulbar affect. J Neurol Sci. 2008;271(1-2):137-147.

4. Werling LL, Keller A, Frank JG, et al. A comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorder. Exp Neurol. 2007;207(2): 248-257.

Pathological laughter and crying— pseudobulbar affect (PBA)—is a disorder of emotional expression characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of laughter or crying without an environmental trigger. Persons with PBA are at an increased risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms associated with an inappropriate outburst of emotion1; such emotional acts might be incongruent with their underlying emotional state.

When should you consider PBA?

Consider PBA in patients with new-onset emotional lability in the presence of certain neurologic conditions. PBA is most common in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and stroke, in which an incidence of >50% has been estimated.2 Other conditions associated with PBA include Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, normal pressure hydrocephalus, progressive supranuclear palsy, Wilson disease, and neurosyphilis.3

Avoid PBA misdiagnosis

Depression is the most common PBA misdiagnosis (Table). However, many clinical features distinguish PBA episodes from depressive symptoms; the most prominent difference is duration. Depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, typically last weeks to months, but a PBA episode lasts seconds or minutes. In addition, crying, as a symptom of PBA, might be unrelated or exaggerated relative to the patient’s mood, but crying is congruent with subjective mood in depression. Other symptoms of depression—fatigue, anorexia, insomnia, anhedonia, and feelings of hopelessness and guilt— are not associated with pseudobulbar affect.

PBA also can be differentiated from bipolar disorder (BD) with rapid cycling or mixed mood episodes because of PBA’s relatively brief duration of laughing or crying episodes—with no mood disturbance between episodes—compared with the sustained changes in mood, cognition, and behavior seen in BD.

Options for treating PBA

Serotonergic therapies, such as amitriptyline and fluoxetine, may exert effects by increasing serotonin in the synapse; dextromethorphan may act via antiglutamatergic effects at N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors and sigma-1 receptors.4 Dextromethorphan binding is most prominent in the brainstem and cerebellum, brain areas known to be rich in sigma-1 receptors and key sites implicated in the pathophysiology of PBA. Although the precise mechanisms by which dextromethorphan ameliorates PBA are unknown, modulation of excessive glutamatergic transmission within corticopontine-cerebellar circuits may contribute to its benefits.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Pathological laughter and crying— pseudobulbar affect (PBA)—is a disorder of emotional expression characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of laughter or crying without an environmental trigger. Persons with PBA are at an increased risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms associated with an inappropriate outburst of emotion1; such emotional acts might be incongruent with their underlying emotional state.

When should you consider PBA?

Consider PBA in patients with new-onset emotional lability in the presence of certain neurologic conditions. PBA is most common in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and stroke, in which an incidence of >50% has been estimated.2 Other conditions associated with PBA include Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, normal pressure hydrocephalus, progressive supranuclear palsy, Wilson disease, and neurosyphilis.3

Avoid PBA misdiagnosis

Depression is the most common PBA misdiagnosis (Table). However, many clinical features distinguish PBA episodes from depressive symptoms; the most prominent difference is duration. Depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, typically last weeks to months, but a PBA episode lasts seconds or minutes. In addition, crying, as a symptom of PBA, might be unrelated or exaggerated relative to the patient’s mood, but crying is congruent with subjective mood in depression. Other symptoms of depression—fatigue, anorexia, insomnia, anhedonia, and feelings of hopelessness and guilt— are not associated with pseudobulbar affect.

PBA also can be differentiated from bipolar disorder (BD) with rapid cycling or mixed mood episodes because of PBA’s relatively brief duration of laughing or crying episodes—with no mood disturbance between episodes—compared with the sustained changes in mood, cognition, and behavior seen in BD.

Options for treating PBA

Serotonergic therapies, such as amitriptyline and fluoxetine, may exert effects by increasing serotonin in the synapse; dextromethorphan may act via antiglutamatergic effects at N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors and sigma-1 receptors.4 Dextromethorphan binding is most prominent in the brainstem and cerebellum, brain areas known to be rich in sigma-1 receptors and key sites implicated in the pathophysiology of PBA. Although the precise mechanisms by which dextromethorphan ameliorates PBA are unknown, modulation of excessive glutamatergic transmission within corticopontine-cerebellar circuits may contribute to its benefits.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Tateno A, Jorge RE, Robinson RG. Pathological laughing and crying following traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16(4):426-434.

2. Miller A, Pratt H, Schiffer RB. Pseudobulbar affect: the spectrum of clinical presentations, etiologies and treatments. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(7):1077-1088.

3. Haiman G, Pratt H, Miller A. Brain responses to verbal stimuli among multiple sclerosis patients with pseudobulbar affect. J Neurol Sci. 2008;271(1-2):137-147.

4. Werling LL, Keller A, Frank JG, et al. A comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorder. Exp Neurol. 2007;207(2): 248-257.

1. Tateno A, Jorge RE, Robinson RG. Pathological laughing and crying following traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16(4):426-434.

2. Miller A, Pratt H, Schiffer RB. Pseudobulbar affect: the spectrum of clinical presentations, etiologies and treatments. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(7):1077-1088.

3. Haiman G, Pratt H, Miller A. Brain responses to verbal stimuli among multiple sclerosis patients with pseudobulbar affect. J Neurol Sci. 2008;271(1-2):137-147.

4. Werling LL, Keller A, Frank JG, et al. A comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorder. Exp Neurol. 2007;207(2): 248-257.

Strategies to enhance patients’ acceptance of voluntary psychiatric admission

Voluntary psychiatric admission has become more problematic because of managed care authorization policies, restrictive inpatient entry criteria, uninsured

patients, and a decline in hospital beds.

In addition, patients often are ambivalent or resistant to hospitalization. It can be challenging to persuade a patient, as well as his (her) family, of the need for psychiatric admission, even when he acknowledges emotional suffering and impaired functioning.

The strategies offered here can enhance the probability that your patient, and his family, will agree to voluntary admission.

Provide a compelling rationale. Stress the need for immediate, specialized, and intensive services. If the patient is receiving outpatient mental health care, advise him that these services have been unsuccessful in achieving safety and clinical stability, and that it is not possible to quickly establish a modified outpatient plan or a day hospital placement that would meet his needs. For a patient who is not receiving outpatient care, explain that it is not feasible to implement a workable plan “from the ground up” in a timely manner.

Reset the clock. Redefine admission as a way to interrupt a downward spiral and offer a new start with a treatment team that has “fresh eyes.”

Use language of the medical model. Explain to the patient that a person who has a dangerously high, poorly controlled body temperature unquestionably needs to be hospitalized and that, by analogy, he—your patient—is running a “high emotional temperature” that warrants inpatient care.

Consider having the patient complete a brief, self-report rating scale, such as the Beck Depression Inventory-II or the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale.1 Review findings with him and his family to show the frequency, duration, and severity of symptoms.

Dispel misconceptions and myths. These include catastrophic fears—often based on stereotypes—about coercive treatment and indefinite confinement. Clarifying what a patient can expect with voluntary admission with regard to probable length of stay, participation in the milieu, visitation, and discharge planning is helpful for allaying such fears.

Build bridges with significant others. Ally with parties who support voluntary admission, including the patient’s primary care or mental health provider, if appropriate. Getting family members and significant others on board; having them talk with the patient can go a long way toward reaching an agreement to proceed with hospitalization.

Maintain an empathic stance. For many patients, psychiatric admission evokes considerable distress. Remain sensitive to the situational concerns that typically arise, such as disruption to family and job responsibilities, insurance coverage, and whether there will be an outpatient plan in place at discharge.

A psychiatric admission often triggers long-standing psychological vulnerabilities— such as feelings of humiliation or failure, fear of separation and abandonment, worry about being a burden to family, stigma, and anxiety about having a serious mental illness—all of which might require exploration to allay upset and enhance compliance.

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned with this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Blais MA. A guide to applying rating scales in clinical psychiatry. Psychiatr Times. 2011;28:58-62.

Voluntary psychiatric admission has become more problematic because of managed care authorization policies, restrictive inpatient entry criteria, uninsured

patients, and a decline in hospital beds.

In addition, patients often are ambivalent or resistant to hospitalization. It can be challenging to persuade a patient, as well as his (her) family, of the need for psychiatric admission, even when he acknowledges emotional suffering and impaired functioning.

The strategies offered here can enhance the probability that your patient, and his family, will agree to voluntary admission.

Provide a compelling rationale. Stress the need for immediate, specialized, and intensive services. If the patient is receiving outpatient mental health care, advise him that these services have been unsuccessful in achieving safety and clinical stability, and that it is not possible to quickly establish a modified outpatient plan or a day hospital placement that would meet his needs. For a patient who is not receiving outpatient care, explain that it is not feasible to implement a workable plan “from the ground up” in a timely manner.

Reset the clock. Redefine admission as a way to interrupt a downward spiral and offer a new start with a treatment team that has “fresh eyes.”

Use language of the medical model. Explain to the patient that a person who has a dangerously high, poorly controlled body temperature unquestionably needs to be hospitalized and that, by analogy, he—your patient—is running a “high emotional temperature” that warrants inpatient care.

Consider having the patient complete a brief, self-report rating scale, such as the Beck Depression Inventory-II or the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale.1 Review findings with him and his family to show the frequency, duration, and severity of symptoms.

Dispel misconceptions and myths. These include catastrophic fears—often based on stereotypes—about coercive treatment and indefinite confinement. Clarifying what a patient can expect with voluntary admission with regard to probable length of stay, participation in the milieu, visitation, and discharge planning is helpful for allaying such fears.

Build bridges with significant others. Ally with parties who support voluntary admission, including the patient’s primary care or mental health provider, if appropriate. Getting family members and significant others on board; having them talk with the patient can go a long way toward reaching an agreement to proceed with hospitalization.

Maintain an empathic stance. For many patients, psychiatric admission evokes considerable distress. Remain sensitive to the situational concerns that typically arise, such as disruption to family and job responsibilities, insurance coverage, and whether there will be an outpatient plan in place at discharge.

A psychiatric admission often triggers long-standing psychological vulnerabilities— such as feelings of humiliation or failure, fear of separation and abandonment, worry about being a burden to family, stigma, and anxiety about having a serious mental illness—all of which might require exploration to allay upset and enhance compliance.

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned with this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Voluntary psychiatric admission has become more problematic because of managed care authorization policies, restrictive inpatient entry criteria, uninsured

patients, and a decline in hospital beds.

In addition, patients often are ambivalent or resistant to hospitalization. It can be challenging to persuade a patient, as well as his (her) family, of the need for psychiatric admission, even when he acknowledges emotional suffering and impaired functioning.

The strategies offered here can enhance the probability that your patient, and his family, will agree to voluntary admission.

Provide a compelling rationale. Stress the need for immediate, specialized, and intensive services. If the patient is receiving outpatient mental health care, advise him that these services have been unsuccessful in achieving safety and clinical stability, and that it is not possible to quickly establish a modified outpatient plan or a day hospital placement that would meet his needs. For a patient who is not receiving outpatient care, explain that it is not feasible to implement a workable plan “from the ground up” in a timely manner.

Reset the clock. Redefine admission as a way to interrupt a downward spiral and offer a new start with a treatment team that has “fresh eyes.”

Use language of the medical model. Explain to the patient that a person who has a dangerously high, poorly controlled body temperature unquestionably needs to be hospitalized and that, by analogy, he—your patient—is running a “high emotional temperature” that warrants inpatient care.

Consider having the patient complete a brief, self-report rating scale, such as the Beck Depression Inventory-II or the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale.1 Review findings with him and his family to show the frequency, duration, and severity of symptoms.

Dispel misconceptions and myths. These include catastrophic fears—often based on stereotypes—about coercive treatment and indefinite confinement. Clarifying what a patient can expect with voluntary admission with regard to probable length of stay, participation in the milieu, visitation, and discharge planning is helpful for allaying such fears.

Build bridges with significant others. Ally with parties who support voluntary admission, including the patient’s primary care or mental health provider, if appropriate. Getting family members and significant others on board; having them talk with the patient can go a long way toward reaching an agreement to proceed with hospitalization.

Maintain an empathic stance. For many patients, psychiatric admission evokes considerable distress. Remain sensitive to the situational concerns that typically arise, such as disruption to family and job responsibilities, insurance coverage, and whether there will be an outpatient plan in place at discharge.

A psychiatric admission often triggers long-standing psychological vulnerabilities— such as feelings of humiliation or failure, fear of separation and abandonment, worry about being a burden to family, stigma, and anxiety about having a serious mental illness—all of which might require exploration to allay upset and enhance compliance.

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned with this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Blais MA. A guide to applying rating scales in clinical psychiatry. Psychiatr Times. 2011;28:58-62.

Reference

1. Blais MA. A guide to applying rating scales in clinical psychiatry. Psychiatr Times. 2011;28:58-62.

Be aware: Sudden discontinuation of a psychotropic risks a lethal outcome

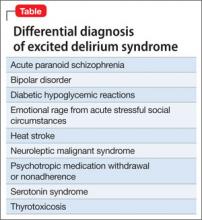

For mentally ill young men, especially, abruptly stopping a psychotropic medication can be lethal.1 Under such circumstances, excited delirium syndrome (EDS), also known as sudden in-custody death syndrome and Bell’s mania, can occur, warranting your careful observation.

Approximately 10% of EDS cases are fatal2; >95% of fatalities occur in men

(mean age, 36 years).3 Most cases involve stimulant abuse—usually cocaine, although cases associated with methamphetamine, phencyclidine, and LSD have been reported. Patients who present with EDS experience a characteristic loss of

the dopamine transporter in the striatum and excessive dopamine stimulation in

the striatum.

What should you watch for?

Other syndromes and disorders can mimic EDS (Table), but there are certain specific symptoms to look for. Patients who have EDS can present with delirium and an excited or agitated state. Other common symptoms include:

• altered sensorium

• aggressive, agitated behavior

• “superhuman” strength (including a tendency to break glass or unwillingness

to yield to overwhelming force)

• diaphoresis

• hyperthermia

• attraction to light.

Patients who have EDS often exhibit constant physical movement. They are likely to be naked or inadequately clothed; to sweat profusely; and to make unintelligible, animal-like noises. They are insensitive to extreme pain. In a small percentage of cases, EDS progresses to sudden cardiopulmonary arrestand death.3

Medication or restraints?

Many clinicians consider aggressive chemical sedation the first-line intervention for

EDS2,3; choice of medication varies from practice to practice. Restraints often are

necessary to ensure the safety of patient and staff, but use them only in conjunction with aggressive chemical sedation. Physical struggle is a greater contributor to catecholamine surge and metabolic acidosis than other types of exertion; methods of physical control should therefore minimize the time a patient spends struggling while safely achieving physical control.

What is the treatment for EDS?

Begin treatment while you are evaluating the patient for precipitating causes or additional pathology. There are cases of death from EDS even with minimal restraint (such as handcuffs),1,2 without the use of an electronic control device or so-called hog-tie restraint.

When providing pharmacotherapy for EDS, consider a benzodiazepine (midazolam, lorazepam, diazepam), an antipsychotic (haloperidol, droperidol, ziprasidone, olanzapine), or ketamine.4 Because these agents can have depressive respiratory and cardiovascular effects, continuously monitor heart and lungs.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Morrison A, Sadler D. Death of a psychiatric patient during physical restraint. Excited delirium—a case report. Med Sci Law. 2001;41(1):46-50.

2. Vilke GM, Debard ML, Chan TC, et al. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): defining based on a review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(5):897-905.

4. Vilke GM, Payne-James J, Karch SB. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): redefining an old diagnosis. J Forensic Leg Med. 2012;19(1):7-11.

4. Hick JL, Ho JD. Ketamine chemical restraint to facilitate rescue of a combative “jumper.” Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005; 9(1):85-89.

For mentally ill young men, especially, abruptly stopping a psychotropic medication can be lethal.1 Under such circumstances, excited delirium syndrome (EDS), also known as sudden in-custody death syndrome and Bell’s mania, can occur, warranting your careful observation.

Approximately 10% of EDS cases are fatal2; >95% of fatalities occur in men

(mean age, 36 years).3 Most cases involve stimulant abuse—usually cocaine, although cases associated with methamphetamine, phencyclidine, and LSD have been reported. Patients who present with EDS experience a characteristic loss of

the dopamine transporter in the striatum and excessive dopamine stimulation in

the striatum.

What should you watch for?

Other syndromes and disorders can mimic EDS (Table), but there are certain specific symptoms to look for. Patients who have EDS can present with delirium and an excited or agitated state. Other common symptoms include:

• altered sensorium

• aggressive, agitated behavior

• “superhuman” strength (including a tendency to break glass or unwillingness

to yield to overwhelming force)

• diaphoresis

• hyperthermia

• attraction to light.

Patients who have EDS often exhibit constant physical movement. They are likely to be naked or inadequately clothed; to sweat profusely; and to make unintelligible, animal-like noises. They are insensitive to extreme pain. In a small percentage of cases, EDS progresses to sudden cardiopulmonary arrestand death.3

Medication or restraints?

Many clinicians consider aggressive chemical sedation the first-line intervention for

EDS2,3; choice of medication varies from practice to practice. Restraints often are

necessary to ensure the safety of patient and staff, but use them only in conjunction with aggressive chemical sedation. Physical struggle is a greater contributor to catecholamine surge and metabolic acidosis than other types of exertion; methods of physical control should therefore minimize the time a patient spends struggling while safely achieving physical control.

What is the treatment for EDS?

Begin treatment while you are evaluating the patient for precipitating causes or additional pathology. There are cases of death from EDS even with minimal restraint (such as handcuffs),1,2 without the use of an electronic control device or so-called hog-tie restraint.

When providing pharmacotherapy for EDS, consider a benzodiazepine (midazolam, lorazepam, diazepam), an antipsychotic (haloperidol, droperidol, ziprasidone, olanzapine), or ketamine.4 Because these agents can have depressive respiratory and cardiovascular effects, continuously monitor heart and lungs.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

For mentally ill young men, especially, abruptly stopping a psychotropic medication can be lethal.1 Under such circumstances, excited delirium syndrome (EDS), also known as sudden in-custody death syndrome and Bell’s mania, can occur, warranting your careful observation.

Approximately 10% of EDS cases are fatal2; >95% of fatalities occur in men

(mean age, 36 years).3 Most cases involve stimulant abuse—usually cocaine, although cases associated with methamphetamine, phencyclidine, and LSD have been reported. Patients who present with EDS experience a characteristic loss of

the dopamine transporter in the striatum and excessive dopamine stimulation in

the striatum.

What should you watch for?

Other syndromes and disorders can mimic EDS (Table), but there are certain specific symptoms to look for. Patients who have EDS can present with delirium and an excited or agitated state. Other common symptoms include:

• altered sensorium

• aggressive, agitated behavior

• “superhuman” strength (including a tendency to break glass or unwillingness

to yield to overwhelming force)

• diaphoresis

• hyperthermia

• attraction to light.

Patients who have EDS often exhibit constant physical movement. They are likely to be naked or inadequately clothed; to sweat profusely; and to make unintelligible, animal-like noises. They are insensitive to extreme pain. In a small percentage of cases, EDS progresses to sudden cardiopulmonary arrestand death.3

Medication or restraints?

Many clinicians consider aggressive chemical sedation the first-line intervention for

EDS2,3; choice of medication varies from practice to practice. Restraints often are

necessary to ensure the safety of patient and staff, but use them only in conjunction with aggressive chemical sedation. Physical struggle is a greater contributor to catecholamine surge and metabolic acidosis than other types of exertion; methods of physical control should therefore minimize the time a patient spends struggling while safely achieving physical control.

What is the treatment for EDS?

Begin treatment while you are evaluating the patient for precipitating causes or additional pathology. There are cases of death from EDS even with minimal restraint (such as handcuffs),1,2 without the use of an electronic control device or so-called hog-tie restraint.

When providing pharmacotherapy for EDS, consider a benzodiazepine (midazolam, lorazepam, diazepam), an antipsychotic (haloperidol, droperidol, ziprasidone, olanzapine), or ketamine.4 Because these agents can have depressive respiratory and cardiovascular effects, continuously monitor heart and lungs.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Morrison A, Sadler D. Death of a psychiatric patient during physical restraint. Excited delirium—a case report. Med Sci Law. 2001;41(1):46-50.

2. Vilke GM, Debard ML, Chan TC, et al. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): defining based on a review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(5):897-905.

4. Vilke GM, Payne-James J, Karch SB. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): redefining an old diagnosis. J Forensic Leg Med. 2012;19(1):7-11.

4. Hick JL, Ho JD. Ketamine chemical restraint to facilitate rescue of a combative “jumper.” Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005; 9(1):85-89.

1. Morrison A, Sadler D. Death of a psychiatric patient during physical restraint. Excited delirium—a case report. Med Sci Law. 2001;41(1):46-50.

2. Vilke GM, Debard ML, Chan TC, et al. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): defining based on a review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(5):897-905.

4. Vilke GM, Payne-James J, Karch SB. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): redefining an old diagnosis. J Forensic Leg Med. 2012;19(1):7-11.

4. Hick JL, Ho JD. Ketamine chemical restraint to facilitate rescue of a combative “jumper.” Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005; 9(1):85-89.

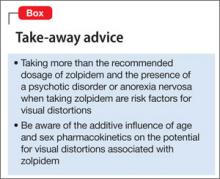

Zolpidem may cause visual distortions and other psychotic symptoms

Zolpidem, an imidazopyridine hypnotic, has been used as an alternative to benzodiazepines for treating short-term insomnia because it has a relatively favorable side effect profile and less potential for abuse.1

However, several cases of zolpidemrelated psychotic symptoms have been reported,2 including a report of an association between zolpidem and hallucinations.1 The case illustrated here describes distortion of visual perception that can occur after ingestion of more than the recommended dosage of zolpidem.

CASE: Terrified and paranoid with distorted vision

Ms. K, age 33, an English-speaking woman from Portugal with a history of schizoaffective disorder, is brought to the emergency department in a terrified state. She describes visual distortion and paranoia because she fears losing her vision. She complains of suicidal ideation, depressed mood, insomnia, auditory

hallucinations, and distortion of visual perception. She reports seeing shadows, recurring movements of the ceiling bearing down on her, and molding or melting walls.

Ms. K reports that the visual distortions began when she started zolpidem, 10 mg/d, 2 months earlier, after her mother in Portugal gave it to her.

Ms. K describes feeling disoriented and disconnected from reality. She reports taking extra doses of zolpidem (40 mg)—recommended maximum dosage is 10 mg3—and clonazepam (1 mg) to address her insomnia.

On examination, Ms. K appears shaky and tremulous, and we note that her eyeballs roll upward. Vital signs are within normal limits, and she is awake, alert, and oriented to person, place, and time.

We diagnose exacerbation of schizoaffective disorder.

Ms. K is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit for observation and treatment. Quetiapine, 100 mg at bedtime, and sertraline, 100 mg/d, are started and zolpidem is discontinued.