User login

Is your depressed postpartum patient bipolar?

Many individuals think of postpartum depression as an episode of major depressive disorder within 4 weeks of delivery; however, postpartum depressive symptoms also can occur in the context of bipolar I disorder (BD I) or bipolar II disorder (BD II). Despite the high prevalence of postpartum hypomania (9% to 20%), clinicians often fail to screen for symptoms of mania or hypomania.1 Determining if your patient’s postpartum depressive episode is caused by BD is essential when formulating an appropriate treatment plan that protects the mother and child.

Postpartum depression literature offers little guidance on the recognition and management of postpartum bipolar disorder.2 For example, there is scant evidence on pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic treatment of postpartum bipolar depression, and no studies have evaluated the use of screening instruments such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to detect bipolar disorder.

Misdiagnosis of postpartum depression is more likely in cases of subtle bipolarity—BD II and BD not otherwise specified—than in BD I because:3

- physicians often fail to ask postpartum patients about hypomanic symptoms such as feelings of elation, being overly talkative, racing thoughts, and decreased need for sleep

- DSM-IV-TR does not recognize hypomania with a postpartum onset specifier

- hypomania symptoms overlap normal feelings of elation and sleep disturbance following childbirth.

Clues to postpartum bipolar disorder include:

- hypomania: persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood

- depression onset immediately after delivery

- atypical features such as hypersomnia, leaden paralysis, and increased appetite

- racing thoughts

- concomitant psychotic symptoms

- history of BD in a first-degree relative

- antidepressants “misadventures” (rapid response; loss of response; induction of mania, hypomania, or depressive mixed episodes; and poor response).

Treatment strategies

Avoid antidepressants. Bipolar depression does not respond to antidepressants as well as unipolar depression. Moreover, antidepressants can induce mania, hypomania, or mixed states, and can increase mood cycle frequency.

Administer mood stabilizers such as lithium or lamotrigine, or atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine.

In breast-feeding women the benefits of treatment should be balanced carefully against the risk of infant exposure to medications. Lamotrigine should be used cautiously because of concerns of skin rash and higher-than-expected drug levels in the infant. In light of recent data showing no significant adverse clinical or behavioral effects in infants, breast-feeding while taking lithium should be considered in carefully selected women. The preliminary evidence supporting the use of quetiapine during breast-feeding appears promising; however, data on the safety of atypical antipsychotics in lactating women are limited.

Promote sleep. Sleep disruption can be a symptom of as well as a trigger for postpartum bipolar depression. In women with BD, the benefits of breast-feeding should be balanced carefully against the potential for the deleterious effects of sleep deprivation in triggering mood episodes. Women should consider using a breast pump allowing others to assist with feeding or supplementing breast milk with formula to help get uninterrupted sleep.3

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Heron J, Craddock N, Jones I. Postnatal euphoria: are ‘the highs’ an indicator of bipolarity? Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:103-110.

2. Sharma V, Khan M, Corpse C, et al. Missed bipolarity and psychiatric comorbidity in women with postpartum depression. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:742-747.

3. Sharma V, Burt VK, Ritchie, HL. Bipolar II postpartum depression: detection, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1217-1221.

Many individuals think of postpartum depression as an episode of major depressive disorder within 4 weeks of delivery; however, postpartum depressive symptoms also can occur in the context of bipolar I disorder (BD I) or bipolar II disorder (BD II). Despite the high prevalence of postpartum hypomania (9% to 20%), clinicians often fail to screen for symptoms of mania or hypomania.1 Determining if your patient’s postpartum depressive episode is caused by BD is essential when formulating an appropriate treatment plan that protects the mother and child.

Postpartum depression literature offers little guidance on the recognition and management of postpartum bipolar disorder.2 For example, there is scant evidence on pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic treatment of postpartum bipolar depression, and no studies have evaluated the use of screening instruments such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to detect bipolar disorder.

Misdiagnosis of postpartum depression is more likely in cases of subtle bipolarity—BD II and BD not otherwise specified—than in BD I because:3

- physicians often fail to ask postpartum patients about hypomanic symptoms such as feelings of elation, being overly talkative, racing thoughts, and decreased need for sleep

- DSM-IV-TR does not recognize hypomania with a postpartum onset specifier

- hypomania symptoms overlap normal feelings of elation and sleep disturbance following childbirth.

Clues to postpartum bipolar disorder include:

- hypomania: persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood

- depression onset immediately after delivery

- atypical features such as hypersomnia, leaden paralysis, and increased appetite

- racing thoughts

- concomitant psychotic symptoms

- history of BD in a first-degree relative

- antidepressants “misadventures” (rapid response; loss of response; induction of mania, hypomania, or depressive mixed episodes; and poor response).

Treatment strategies

Avoid antidepressants. Bipolar depression does not respond to antidepressants as well as unipolar depression. Moreover, antidepressants can induce mania, hypomania, or mixed states, and can increase mood cycle frequency.

Administer mood stabilizers such as lithium or lamotrigine, or atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine.

In breast-feeding women the benefits of treatment should be balanced carefully against the risk of infant exposure to medications. Lamotrigine should be used cautiously because of concerns of skin rash and higher-than-expected drug levels in the infant. In light of recent data showing no significant adverse clinical or behavioral effects in infants, breast-feeding while taking lithium should be considered in carefully selected women. The preliminary evidence supporting the use of quetiapine during breast-feeding appears promising; however, data on the safety of atypical antipsychotics in lactating women are limited.

Promote sleep. Sleep disruption can be a symptom of as well as a trigger for postpartum bipolar depression. In women with BD, the benefits of breast-feeding should be balanced carefully against the potential for the deleterious effects of sleep deprivation in triggering mood episodes. Women should consider using a breast pump allowing others to assist with feeding or supplementing breast milk with formula to help get uninterrupted sleep.3

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Many individuals think of postpartum depression as an episode of major depressive disorder within 4 weeks of delivery; however, postpartum depressive symptoms also can occur in the context of bipolar I disorder (BD I) or bipolar II disorder (BD II). Despite the high prevalence of postpartum hypomania (9% to 20%), clinicians often fail to screen for symptoms of mania or hypomania.1 Determining if your patient’s postpartum depressive episode is caused by BD is essential when formulating an appropriate treatment plan that protects the mother and child.

Postpartum depression literature offers little guidance on the recognition and management of postpartum bipolar disorder.2 For example, there is scant evidence on pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic treatment of postpartum bipolar depression, and no studies have evaluated the use of screening instruments such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to detect bipolar disorder.

Misdiagnosis of postpartum depression is more likely in cases of subtle bipolarity—BD II and BD not otherwise specified—than in BD I because:3

- physicians often fail to ask postpartum patients about hypomanic symptoms such as feelings of elation, being overly talkative, racing thoughts, and decreased need for sleep

- DSM-IV-TR does not recognize hypomania with a postpartum onset specifier

- hypomania symptoms overlap normal feelings of elation and sleep disturbance following childbirth.

Clues to postpartum bipolar disorder include:

- hypomania: persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood

- depression onset immediately after delivery

- atypical features such as hypersomnia, leaden paralysis, and increased appetite

- racing thoughts

- concomitant psychotic symptoms

- history of BD in a first-degree relative

- antidepressants “misadventures” (rapid response; loss of response; induction of mania, hypomania, or depressive mixed episodes; and poor response).

Treatment strategies

Avoid antidepressants. Bipolar depression does not respond to antidepressants as well as unipolar depression. Moreover, antidepressants can induce mania, hypomania, or mixed states, and can increase mood cycle frequency.

Administer mood stabilizers such as lithium or lamotrigine, or atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine.

In breast-feeding women the benefits of treatment should be balanced carefully against the risk of infant exposure to medications. Lamotrigine should be used cautiously because of concerns of skin rash and higher-than-expected drug levels in the infant. In light of recent data showing no significant adverse clinical or behavioral effects in infants, breast-feeding while taking lithium should be considered in carefully selected women. The preliminary evidence supporting the use of quetiapine during breast-feeding appears promising; however, data on the safety of atypical antipsychotics in lactating women are limited.

Promote sleep. Sleep disruption can be a symptom of as well as a trigger for postpartum bipolar depression. In women with BD, the benefits of breast-feeding should be balanced carefully against the potential for the deleterious effects of sleep deprivation in triggering mood episodes. Women should consider using a breast pump allowing others to assist with feeding or supplementing breast milk with formula to help get uninterrupted sleep.3

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Heron J, Craddock N, Jones I. Postnatal euphoria: are ‘the highs’ an indicator of bipolarity? Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:103-110.

2. Sharma V, Khan M, Corpse C, et al. Missed bipolarity and psychiatric comorbidity in women with postpartum depression. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:742-747.

3. Sharma V, Burt VK, Ritchie, HL. Bipolar II postpartum depression: detection, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1217-1221.

1. Heron J, Craddock N, Jones I. Postnatal euphoria: are ‘the highs’ an indicator of bipolarity? Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:103-110.

2. Sharma V, Khan M, Corpse C, et al. Missed bipolarity and psychiatric comorbidity in women with postpartum depression. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:742-747.

3. Sharma V, Burt VK, Ritchie, HL. Bipolar II postpartum depression: detection, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1217-1221.

The ABCs of estimating adherence to antipsychotics

Adequate adherence to antipsychotics is critical for most patients with a chronic psychotic disorder. Therefore, appraisal of medication adherence—also called compliance in the older literature—is crucial at all visits.

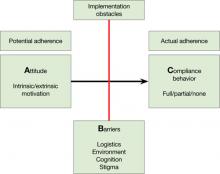

Medication adherence is both an attitude and a behavior,1 and you need to assess both. Without some motivation to take medications (ie, a positive drug attitude), adherence is unlikely. On the other hand, motivation alone does not guarantee compliance behavior, and you need to assess barriers to adherence even in motivated patients.

To arrive at a clinical estimate of adherence to antipsychotics, ask yourself:

A What is my patient’s Attitude toward antipsychotics?

Expect a positive drug attitude if the medication is perceived as warranted, potentially effective, and tolerable. Inquire about prior experience with medications and psychiatrists, including unpleasant somatic experiences, periods of coercion, specific benefits, and fears. Remember that the perceived harm from—vs the perceived need for—medications is judged from the patient’s point of view, not the clinician’s. For example, some patients are motivated to take an antipsychotic because it helps them sleep. Make note if motivation is intrinsic or extrinsic. You might start by asking, “Why do you think taking this medication is a good idea?”

Figure: Attitude, Barriers, and Compliance behavior

B Are there Barriers for a motivated patient to implement optimal adherence?

Ask, “What gets in the way of taking your medication?” Identifying barriers for the motivated patient forces you to look at the individual’s real-life situation. Can the patient afford the co-pay? Is the family against the patient taking an antipsychotic? Does the patient lack a routine that would help him or her remember to take pills? Is the patient too ashamed of the stigma of taking psychiatric medications? Does the patient have cognitive impairment that leads to forgetting to take pills?

C What is my best quantitative estimate of Compliance behavior?

Ask your patient, “In the last 7 days, how many pills have you missed?” Inquire also about names of pills and dosages, number of pills prescribed, and how they are taken to get a sense of your patient’s routines and cognitive competence. This is the time to get collateral information, such as when the last prescription was filled. After collecting this information, you should be able to estimate a patient’s level of adherence (eg, almost 100%, partial 50% to 75%, none). Be aware that both clinicians and patients overestimate actual adherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Kontos and Querques report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Freudenreich receives grant/research support from Pfizer Inc. He is a consultant to Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Beacon Health Strategies, LLC and a speaker for Reed Medical Education.

1. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1-46.

Adequate adherence to antipsychotics is critical for most patients with a chronic psychotic disorder. Therefore, appraisal of medication adherence—also called compliance in the older literature—is crucial at all visits.

Medication adherence is both an attitude and a behavior,1 and you need to assess both. Without some motivation to take medications (ie, a positive drug attitude), adherence is unlikely. On the other hand, motivation alone does not guarantee compliance behavior, and you need to assess barriers to adherence even in motivated patients.

To arrive at a clinical estimate of adherence to antipsychotics, ask yourself:

A What is my patient’s Attitude toward antipsychotics?

Expect a positive drug attitude if the medication is perceived as warranted, potentially effective, and tolerable. Inquire about prior experience with medications and psychiatrists, including unpleasant somatic experiences, periods of coercion, specific benefits, and fears. Remember that the perceived harm from—vs the perceived need for—medications is judged from the patient’s point of view, not the clinician’s. For example, some patients are motivated to take an antipsychotic because it helps them sleep. Make note if motivation is intrinsic or extrinsic. You might start by asking, “Why do you think taking this medication is a good idea?”

Figure: Attitude, Barriers, and Compliance behavior

B Are there Barriers for a motivated patient to implement optimal adherence?

Ask, “What gets in the way of taking your medication?” Identifying barriers for the motivated patient forces you to look at the individual’s real-life situation. Can the patient afford the co-pay? Is the family against the patient taking an antipsychotic? Does the patient lack a routine that would help him or her remember to take pills? Is the patient too ashamed of the stigma of taking psychiatric medications? Does the patient have cognitive impairment that leads to forgetting to take pills?

C What is my best quantitative estimate of Compliance behavior?

Ask your patient, “In the last 7 days, how many pills have you missed?” Inquire also about names of pills and dosages, number of pills prescribed, and how they are taken to get a sense of your patient’s routines and cognitive competence. This is the time to get collateral information, such as when the last prescription was filled. After collecting this information, you should be able to estimate a patient’s level of adherence (eg, almost 100%, partial 50% to 75%, none). Be aware that both clinicians and patients overestimate actual adherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Kontos and Querques report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Freudenreich receives grant/research support from Pfizer Inc. He is a consultant to Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Beacon Health Strategies, LLC and a speaker for Reed Medical Education.

Adequate adherence to antipsychotics is critical for most patients with a chronic psychotic disorder. Therefore, appraisal of medication adherence—also called compliance in the older literature—is crucial at all visits.

Medication adherence is both an attitude and a behavior,1 and you need to assess both. Without some motivation to take medications (ie, a positive drug attitude), adherence is unlikely. On the other hand, motivation alone does not guarantee compliance behavior, and you need to assess barriers to adherence even in motivated patients.

To arrive at a clinical estimate of adherence to antipsychotics, ask yourself:

A What is my patient’s Attitude toward antipsychotics?

Expect a positive drug attitude if the medication is perceived as warranted, potentially effective, and tolerable. Inquire about prior experience with medications and psychiatrists, including unpleasant somatic experiences, periods of coercion, specific benefits, and fears. Remember that the perceived harm from—vs the perceived need for—medications is judged from the patient’s point of view, not the clinician’s. For example, some patients are motivated to take an antipsychotic because it helps them sleep. Make note if motivation is intrinsic or extrinsic. You might start by asking, “Why do you think taking this medication is a good idea?”

Figure: Attitude, Barriers, and Compliance behavior

B Are there Barriers for a motivated patient to implement optimal adherence?

Ask, “What gets in the way of taking your medication?” Identifying barriers for the motivated patient forces you to look at the individual’s real-life situation. Can the patient afford the co-pay? Is the family against the patient taking an antipsychotic? Does the patient lack a routine that would help him or her remember to take pills? Is the patient too ashamed of the stigma of taking psychiatric medications? Does the patient have cognitive impairment that leads to forgetting to take pills?

C What is my best quantitative estimate of Compliance behavior?

Ask your patient, “In the last 7 days, how many pills have you missed?” Inquire also about names of pills and dosages, number of pills prescribed, and how they are taken to get a sense of your patient’s routines and cognitive competence. This is the time to get collateral information, such as when the last prescription was filled. After collecting this information, you should be able to estimate a patient’s level of adherence (eg, almost 100%, partial 50% to 75%, none). Be aware that both clinicians and patients overestimate actual adherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Kontos and Querques report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Freudenreich receives grant/research support from Pfizer Inc. He is a consultant to Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Beacon Health Strategies, LLC and a speaker for Reed Medical Education.

1. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1-46.

1. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1-46.

Help patients SLEEP without medication

Some of patients’ most common complaints involve sleep: too little, too late, never enough. Although sleep disruptions often are related to the psychiatric disorder for which the person seeks treatment, cognitive and behavioral factors play significant roles.1 Unfortunately, quite often patients expect to be given “something” to foster sleep.

Before writing a prescription, be prepared to evaluate sleep disturbances and educate patients about sleep and how it can be facilitated without medication. The mnemonic SLEEP can help you readily access a basic set of nonpharmacologic aids to assess and treat uncomplicated sleep disturbances.

Schedule. Ask patients about their sleep-wake schedule. Is their pattern routine and regular, or unpredictable? Are they “in synch” with the sleep/activity patterns of those with whom they live, or is their schedule “off track” and disrupted by household noise and activities? Consistency is key to normalizing sleep.

Limit. Sensible limits on caffeinated beverages need to be addressed. Strongly encourage patients to limit nicotine and alcohol in-take. Assess the amount as well as timing of their use of these substances. Remind your patient that alcohol and smoking have a direct impact on sleep initiation and can disrupt sleep because of nocturnal withdrawal.

Eliminate. Removing noxious environmental stimuli is critical. Ask patients about the level of nighttime noise, excessive light, and ventilation and temperature of their sleeping area (cooler is better). Eliminate factors that create a “hostile” sleep environment.

Exercise. Regular exercise performed during the day (but not immediately before going to bed) may be an effective antidote to the psychic stress and physical tension that often contribute to insomnia.2 A several-times-per-week routine of brisk walking, riding a bicycle, swimming, or yoga can reduce sleep-onset latency and improve sleep maintenance. An exercise routine can enhance a patient’s overall health and knock out a daytime sleep habit.

Psychotherapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia has demonstrated efficacy in treating sleep disorders.3 Learning how to “catch, check, and change” distorted and negative cognitions regarding sleep onset can be a valuable tool for persons who are motivated to alter their thoughts and behaviors that contribute to sleep complaints, and may simultaneously improve associated anxiety and/or depression.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, et al. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: update of the recent evidence (1998-2004). Sleep. 2006;9:1398-1414.

2. Passos GS, Povares D, Santana MG, et al. Effect of acute physical exercise on patients with chronic primary insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6:270-275.

3. Edinger JD, Olsen MK, Stechuchak KM, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with primary insomnia or insomnia associated predominantly with mixed psychiatric disorders: a randomized clinical trial. Sleep. 2009;32:499-510.

Some of patients’ most common complaints involve sleep: too little, too late, never enough. Although sleep disruptions often are related to the psychiatric disorder for which the person seeks treatment, cognitive and behavioral factors play significant roles.1 Unfortunately, quite often patients expect to be given “something” to foster sleep.

Before writing a prescription, be prepared to evaluate sleep disturbances and educate patients about sleep and how it can be facilitated without medication. The mnemonic SLEEP can help you readily access a basic set of nonpharmacologic aids to assess and treat uncomplicated sleep disturbances.

Schedule. Ask patients about their sleep-wake schedule. Is their pattern routine and regular, or unpredictable? Are they “in synch” with the sleep/activity patterns of those with whom they live, or is their schedule “off track” and disrupted by household noise and activities? Consistency is key to normalizing sleep.

Limit. Sensible limits on caffeinated beverages need to be addressed. Strongly encourage patients to limit nicotine and alcohol in-take. Assess the amount as well as timing of their use of these substances. Remind your patient that alcohol and smoking have a direct impact on sleep initiation and can disrupt sleep because of nocturnal withdrawal.

Eliminate. Removing noxious environmental stimuli is critical. Ask patients about the level of nighttime noise, excessive light, and ventilation and temperature of their sleeping area (cooler is better). Eliminate factors that create a “hostile” sleep environment.

Exercise. Regular exercise performed during the day (but not immediately before going to bed) may be an effective antidote to the psychic stress and physical tension that often contribute to insomnia.2 A several-times-per-week routine of brisk walking, riding a bicycle, swimming, or yoga can reduce sleep-onset latency and improve sleep maintenance. An exercise routine can enhance a patient’s overall health and knock out a daytime sleep habit.

Psychotherapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia has demonstrated efficacy in treating sleep disorders.3 Learning how to “catch, check, and change” distorted and negative cognitions regarding sleep onset can be a valuable tool for persons who are motivated to alter their thoughts and behaviors that contribute to sleep complaints, and may simultaneously improve associated anxiety and/or depression.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Some of patients’ most common complaints involve sleep: too little, too late, never enough. Although sleep disruptions often are related to the psychiatric disorder for which the person seeks treatment, cognitive and behavioral factors play significant roles.1 Unfortunately, quite often patients expect to be given “something” to foster sleep.

Before writing a prescription, be prepared to evaluate sleep disturbances and educate patients about sleep and how it can be facilitated without medication. The mnemonic SLEEP can help you readily access a basic set of nonpharmacologic aids to assess and treat uncomplicated sleep disturbances.

Schedule. Ask patients about their sleep-wake schedule. Is their pattern routine and regular, or unpredictable? Are they “in synch” with the sleep/activity patterns of those with whom they live, or is their schedule “off track” and disrupted by household noise and activities? Consistency is key to normalizing sleep.

Limit. Sensible limits on caffeinated beverages need to be addressed. Strongly encourage patients to limit nicotine and alcohol in-take. Assess the amount as well as timing of their use of these substances. Remind your patient that alcohol and smoking have a direct impact on sleep initiation and can disrupt sleep because of nocturnal withdrawal.

Eliminate. Removing noxious environmental stimuli is critical. Ask patients about the level of nighttime noise, excessive light, and ventilation and temperature of their sleeping area (cooler is better). Eliminate factors that create a “hostile” sleep environment.

Exercise. Regular exercise performed during the day (but not immediately before going to bed) may be an effective antidote to the psychic stress and physical tension that often contribute to insomnia.2 A several-times-per-week routine of brisk walking, riding a bicycle, swimming, or yoga can reduce sleep-onset latency and improve sleep maintenance. An exercise routine can enhance a patient’s overall health and knock out a daytime sleep habit.

Psychotherapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia has demonstrated efficacy in treating sleep disorders.3 Learning how to “catch, check, and change” distorted and negative cognitions regarding sleep onset can be a valuable tool for persons who are motivated to alter their thoughts and behaviors that contribute to sleep complaints, and may simultaneously improve associated anxiety and/or depression.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, et al. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: update of the recent evidence (1998-2004). Sleep. 2006;9:1398-1414.

2. Passos GS, Povares D, Santana MG, et al. Effect of acute physical exercise on patients with chronic primary insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6:270-275.

3. Edinger JD, Olsen MK, Stechuchak KM, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with primary insomnia or insomnia associated predominantly with mixed psychiatric disorders: a randomized clinical trial. Sleep. 2009;32:499-510.

1. Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, et al. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: update of the recent evidence (1998-2004). Sleep. 2006;9:1398-1414.

2. Passos GS, Povares D, Santana MG, et al. Effect of acute physical exercise on patients with chronic primary insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6:270-275.

3. Edinger JD, Olsen MK, Stechuchak KM, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with primary insomnia or insomnia associated predominantly with mixed psychiatric disorders: a randomized clinical trial. Sleep. 2009;32:499-510.

Reduce inpatient violence: 6 strategies

The least effective, most costly method of reducing patient violence is to attempt to contain it after it has occurred. If containment includes using restraints, staff and patients are at additional risk for injury.

Our facility, a 315-bed, medium-security forensic program and a 75-bed civil program, is in its 16th year of violence and restraint reduction.1 We have reduced restraint usage by >95%, and our hospital is one of the safest in our state. In March 2010, we were 1 of 10 institutions recognized by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration for our efforts in reducing and preventing use of seclusion and restraints. If your facility is interested in such efforts, we recommend becoming familiar with the Six Core Strategies Planning Tool.2

Leadership toward organizational change. Any restraint reduction program is likely to encounter resistance. Active and visible presence of hospital leadership is essential to success. According to LeBel, 3 “Advancing seclusion and restraint standards is in the hands of administrators. The knowledge… is available, but it takes leadership, courage, and effort.”

Using data to inform practice. Leadership’s most effective tool is data. When we began our efforts in 1995 by doing nothing more than telling staff we would be tracking restraint usage, usage decreased by 36%. Next, leadership reduced the maximum time for a restraint order from 4 to 2 hours. Eventually, we reduced the maximum time to 1 hour. Restraint orders seldom required renewal.

One of the most useful pieces of data we developed established that on average, our well-trained staff incurred injuries severe enough to require medical treatment in 1 of every 4 instances of applying mechanical restraints. All staff could appreciate that as restraint usage was reduced, the number of associated staff injuries also would fall.

Workforce development. Leadership’s most valuable resource is its workforce. Experience showed that a substantial number of restraint episodes started with rigid enforcement of unit rules. We provide staff with the tools necessary to make clinically based decisions, rather than relying on strict adherence to rules. Staff should never get the impression that patients are being empowered but staff are not.

Initially, we relied on a “champion” or “train the trainer” model. This proved nonproductive because our message often was distorted by the time it reached direct care staff. We developed a half-day training program in which our hospital administrator and medical directors participated. In 16 sessions over 9 months we trained 590 clinical staff, security officers, and other support personnel. Training included interactive education in the public health prevention model, principles of recovery, trauma informed care, and conflict resolution. Recovery specialists and patients were among the presenters. We acted out and analyzed conflict scenarios based on actual experiences on the units with varying approaches. We learned that a number of our direct care staff had informally developed various techniques for successfully resolving problematic situations in a noncoercive manner. We celebrated these staff members and incorporated their ideas into our training sessions.

Ongoing efforts include sessions for direct care staff on subjects such as relaxation techniques, verbal de-escalation, and fundamentals of a mental status evaluation. These are conducted primarily by staff psychologists or incorporated into required annual staff training.

Use of seclusion and restraint reduction tools. Our psychiatric evaluation, which included a thorough assessment for violence risk, was revised to include assessment of risk factors for restraint use. Nursing assessments were revised to include history of restraint or seclusion use, options for early intervention, and patient preferences for anger management and interventions. Intake areas and common rooms were repainted and amenities added to create a more pleasant, less institutional atmosphere. For a description of comfort rooms, visit www.power2u.org/downloads/ComfortRooms4-23-09.pdf Where there wasn’t space for a comfort room, we created comfort kits, which include items such as stress balls, word games, and soothing pictures. These kits are for patients’ benefit and patients should have a role in designing them. Use is voluntary. Comfort kits are not a substitute for therapeutic involvement or necessary seclusion or restraint to prevent imminent injury.

Consumer roles in inpatient settings. Patients are an often-overlooked resource. They too have a vested interest in hospital safety. We involved patients in staff training sessions. Consumer councils were consulted on relevant hospital policy changes and participated in revising the hospital’s Patient/ Family Handbooks. Patient/staff work-groups were asked to replace ad hoc unit rules with expectations for civil behavior that apply to patients and staff. Patients were trained to co-lead groups dealing with accepting responsibility for their own recovery.

Debriefing techniques. The patient and staff are debriefed after every restraint and seclusion episode. A nurse and psychologist debrief the patient, focusing on what the staff and patient could have done to avoid the incident. A recovery specialist and a medical administrator attend each debriefing. The focus initially was to justify restraint and seclusion use, but quickly broadened to include exploring early signs that if recognized and addressed could prevent a repeat incidence.

Different hospitals may place different emphasis on each core strategy. In our experience, the 2 strategies most important to positive results were:

- active, unwavering, and visible commitment of hospital leadership to reducing violence and restraints, and

- timely analysis of relevant data, and the determination to address the results of such analysis in a coherent and collegial manner.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Hardy DW, Patel M, et al. Violence and restraint reduction: one hospital’s experience. Psychiatrist Administrator. 2005;5(1):10-13.

2. National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning. Six core strategies to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint planning tool. Available at: http:// www.nasmhpd.org/general_files/publications/ntac_pubs/SR%20Plan%20Template%20with%20cover%207-05.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2011.

3. LeBel J. Regulatory change: a pathway to eliminating seclusion and restraint or “regulatory scotoma?” Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:194-196.

The least effective, most costly method of reducing patient violence is to attempt to contain it after it has occurred. If containment includes using restraints, staff and patients are at additional risk for injury.

Our facility, a 315-bed, medium-security forensic program and a 75-bed civil program, is in its 16th year of violence and restraint reduction.1 We have reduced restraint usage by >95%, and our hospital is one of the safest in our state. In March 2010, we were 1 of 10 institutions recognized by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration for our efforts in reducing and preventing use of seclusion and restraints. If your facility is interested in such efforts, we recommend becoming familiar with the Six Core Strategies Planning Tool.2

Leadership toward organizational change. Any restraint reduction program is likely to encounter resistance. Active and visible presence of hospital leadership is essential to success. According to LeBel, 3 “Advancing seclusion and restraint standards is in the hands of administrators. The knowledge… is available, but it takes leadership, courage, and effort.”

Using data to inform practice. Leadership’s most effective tool is data. When we began our efforts in 1995 by doing nothing more than telling staff we would be tracking restraint usage, usage decreased by 36%. Next, leadership reduced the maximum time for a restraint order from 4 to 2 hours. Eventually, we reduced the maximum time to 1 hour. Restraint orders seldom required renewal.

One of the most useful pieces of data we developed established that on average, our well-trained staff incurred injuries severe enough to require medical treatment in 1 of every 4 instances of applying mechanical restraints. All staff could appreciate that as restraint usage was reduced, the number of associated staff injuries also would fall.

Workforce development. Leadership’s most valuable resource is its workforce. Experience showed that a substantial number of restraint episodes started with rigid enforcement of unit rules. We provide staff with the tools necessary to make clinically based decisions, rather than relying on strict adherence to rules. Staff should never get the impression that patients are being empowered but staff are not.

Initially, we relied on a “champion” or “train the trainer” model. This proved nonproductive because our message often was distorted by the time it reached direct care staff. We developed a half-day training program in which our hospital administrator and medical directors participated. In 16 sessions over 9 months we trained 590 clinical staff, security officers, and other support personnel. Training included interactive education in the public health prevention model, principles of recovery, trauma informed care, and conflict resolution. Recovery specialists and patients were among the presenters. We acted out and analyzed conflict scenarios based on actual experiences on the units with varying approaches. We learned that a number of our direct care staff had informally developed various techniques for successfully resolving problematic situations in a noncoercive manner. We celebrated these staff members and incorporated their ideas into our training sessions.

Ongoing efforts include sessions for direct care staff on subjects such as relaxation techniques, verbal de-escalation, and fundamentals of a mental status evaluation. These are conducted primarily by staff psychologists or incorporated into required annual staff training.

Use of seclusion and restraint reduction tools. Our psychiatric evaluation, which included a thorough assessment for violence risk, was revised to include assessment of risk factors for restraint use. Nursing assessments were revised to include history of restraint or seclusion use, options for early intervention, and patient preferences for anger management and interventions. Intake areas and common rooms were repainted and amenities added to create a more pleasant, less institutional atmosphere. For a description of comfort rooms, visit www.power2u.org/downloads/ComfortRooms4-23-09.pdf Where there wasn’t space for a comfort room, we created comfort kits, which include items such as stress balls, word games, and soothing pictures. These kits are for patients’ benefit and patients should have a role in designing them. Use is voluntary. Comfort kits are not a substitute for therapeutic involvement or necessary seclusion or restraint to prevent imminent injury.

Consumer roles in inpatient settings. Patients are an often-overlooked resource. They too have a vested interest in hospital safety. We involved patients in staff training sessions. Consumer councils were consulted on relevant hospital policy changes and participated in revising the hospital’s Patient/ Family Handbooks. Patient/staff work-groups were asked to replace ad hoc unit rules with expectations for civil behavior that apply to patients and staff. Patients were trained to co-lead groups dealing with accepting responsibility for their own recovery.

Debriefing techniques. The patient and staff are debriefed after every restraint and seclusion episode. A nurse and psychologist debrief the patient, focusing on what the staff and patient could have done to avoid the incident. A recovery specialist and a medical administrator attend each debriefing. The focus initially was to justify restraint and seclusion use, but quickly broadened to include exploring early signs that if recognized and addressed could prevent a repeat incidence.

Different hospitals may place different emphasis on each core strategy. In our experience, the 2 strategies most important to positive results were:

- active, unwavering, and visible commitment of hospital leadership to reducing violence and restraints, and

- timely analysis of relevant data, and the determination to address the results of such analysis in a coherent and collegial manner.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The least effective, most costly method of reducing patient violence is to attempt to contain it after it has occurred. If containment includes using restraints, staff and patients are at additional risk for injury.

Our facility, a 315-bed, medium-security forensic program and a 75-bed civil program, is in its 16th year of violence and restraint reduction.1 We have reduced restraint usage by >95%, and our hospital is one of the safest in our state. In March 2010, we were 1 of 10 institutions recognized by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration for our efforts in reducing and preventing use of seclusion and restraints. If your facility is interested in such efforts, we recommend becoming familiar with the Six Core Strategies Planning Tool.2

Leadership toward organizational change. Any restraint reduction program is likely to encounter resistance. Active and visible presence of hospital leadership is essential to success. According to LeBel, 3 “Advancing seclusion and restraint standards is in the hands of administrators. The knowledge… is available, but it takes leadership, courage, and effort.”

Using data to inform practice. Leadership’s most effective tool is data. When we began our efforts in 1995 by doing nothing more than telling staff we would be tracking restraint usage, usage decreased by 36%. Next, leadership reduced the maximum time for a restraint order from 4 to 2 hours. Eventually, we reduced the maximum time to 1 hour. Restraint orders seldom required renewal.

One of the most useful pieces of data we developed established that on average, our well-trained staff incurred injuries severe enough to require medical treatment in 1 of every 4 instances of applying mechanical restraints. All staff could appreciate that as restraint usage was reduced, the number of associated staff injuries also would fall.

Workforce development. Leadership’s most valuable resource is its workforce. Experience showed that a substantial number of restraint episodes started with rigid enforcement of unit rules. We provide staff with the tools necessary to make clinically based decisions, rather than relying on strict adherence to rules. Staff should never get the impression that patients are being empowered but staff are not.

Initially, we relied on a “champion” or “train the trainer” model. This proved nonproductive because our message often was distorted by the time it reached direct care staff. We developed a half-day training program in which our hospital administrator and medical directors participated. In 16 sessions over 9 months we trained 590 clinical staff, security officers, and other support personnel. Training included interactive education in the public health prevention model, principles of recovery, trauma informed care, and conflict resolution. Recovery specialists and patients were among the presenters. We acted out and analyzed conflict scenarios based on actual experiences on the units with varying approaches. We learned that a number of our direct care staff had informally developed various techniques for successfully resolving problematic situations in a noncoercive manner. We celebrated these staff members and incorporated their ideas into our training sessions.

Ongoing efforts include sessions for direct care staff on subjects such as relaxation techniques, verbal de-escalation, and fundamentals of a mental status evaluation. These are conducted primarily by staff psychologists or incorporated into required annual staff training.

Use of seclusion and restraint reduction tools. Our psychiatric evaluation, which included a thorough assessment for violence risk, was revised to include assessment of risk factors for restraint use. Nursing assessments were revised to include history of restraint or seclusion use, options for early intervention, and patient preferences for anger management and interventions. Intake areas and common rooms were repainted and amenities added to create a more pleasant, less institutional atmosphere. For a description of comfort rooms, visit www.power2u.org/downloads/ComfortRooms4-23-09.pdf Where there wasn’t space for a comfort room, we created comfort kits, which include items such as stress balls, word games, and soothing pictures. These kits are for patients’ benefit and patients should have a role in designing them. Use is voluntary. Comfort kits are not a substitute for therapeutic involvement or necessary seclusion or restraint to prevent imminent injury.

Consumer roles in inpatient settings. Patients are an often-overlooked resource. They too have a vested interest in hospital safety. We involved patients in staff training sessions. Consumer councils were consulted on relevant hospital policy changes and participated in revising the hospital’s Patient/ Family Handbooks. Patient/staff work-groups were asked to replace ad hoc unit rules with expectations for civil behavior that apply to patients and staff. Patients were trained to co-lead groups dealing with accepting responsibility for their own recovery.

Debriefing techniques. The patient and staff are debriefed after every restraint and seclusion episode. A nurse and psychologist debrief the patient, focusing on what the staff and patient could have done to avoid the incident. A recovery specialist and a medical administrator attend each debriefing. The focus initially was to justify restraint and seclusion use, but quickly broadened to include exploring early signs that if recognized and addressed could prevent a repeat incidence.

Different hospitals may place different emphasis on each core strategy. In our experience, the 2 strategies most important to positive results were:

- active, unwavering, and visible commitment of hospital leadership to reducing violence and restraints, and

- timely analysis of relevant data, and the determination to address the results of such analysis in a coherent and collegial manner.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Hardy DW, Patel M, et al. Violence and restraint reduction: one hospital’s experience. Psychiatrist Administrator. 2005;5(1):10-13.

2. National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning. Six core strategies to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint planning tool. Available at: http:// www.nasmhpd.org/general_files/publications/ntac_pubs/SR%20Plan%20Template%20with%20cover%207-05.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2011.

3. LeBel J. Regulatory change: a pathway to eliminating seclusion and restraint or “regulatory scotoma?” Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:194-196.

1. Hardy DW, Patel M, et al. Violence and restraint reduction: one hospital’s experience. Psychiatrist Administrator. 2005;5(1):10-13.

2. National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning. Six core strategies to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint planning tool. Available at: http:// www.nasmhpd.org/general_files/publications/ntac_pubs/SR%20Plan%20Template%20with%20cover%207-05.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2011.

3. LeBel J. Regulatory change: a pathway to eliminating seclusion and restraint or “regulatory scotoma?” Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:194-196.

New-onset psychosis: Consider epilepsy

Interictal psychosis of epilepsy (IPE) is schizophrenia-like psychosis associated with epilepsy that cannot be directly linked to an ictus. IPE often is indistinguishable from primary schizophrenia. This phenomenon commonly occurs in patients with a history of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE); in those with frequent seizures; and in patients with a long history of epilepsy (>10 years).1 Interictal psychosis rarely precedes seizure activity2 and few cases have been reported. The epidemiology and clinical characteristics of IPE are poorly defined.3 We recently treated a patient with suspected IPE.

Mr. R, age 18, presented to our emergency department with his mother, who stated that her son was behaving strangely and had slow speech for 4 days. He had decreased social interaction, reduced appetite, poor hygiene, decreased sleep, and auditory hallucinations. Mr. R demonstrated hypervigilance and paranoia. He repeatedly checked rooms in his house for intruders. Mr. R also expressed suicidal ideation and exhibited cognitive decline of memory, attention, and fund of knowledge. His physical exam, routine laboratory investigations, CT, and MRI were within normal limits. Urine drug screen was positive for marijuana. We made a clinical diagnosis of acute psychosis.

Mr. R was admitted and started on ziprasidone, titrated to 160 mg/d; however, he could not tolerate this medication because of orthostatic hypotension. We discontinued ziprasidone and started risperidone, titrated to 4 mg/d. By day 4 Mr. R remained psychotic and marijuana intoxication was ruled out. EEG demonstrated rare intermittent left temporal sharp slow wave discharges and sharply contoured slow waves. This suggested an underlying seizure disorder, although Mr. R had no history of seizure.

The psychosis resolved 3 weeks later with risperidone, 2 mg/d, risperidone long-acting injection, 25 mg every 2 weeks, and carbamazepine, 400 mg/d. Mr. R was discharged home on these medications. He was noncompliant with treatment and continued to smoke marijuana. Four months later, Mr. R was rehospitalized for strange behavior. When seen in the outpatient clinic for follow-up, Mr. R admitted that he had his first witnessed seizure before his last hospitalization. Mr. R was restarted on risperidone, 4 mg/d, and risperidone long-acting injection, 25 mg every 2 weeks. To increase compliance, we switched carbamazepine to divalproex sodium extended-release, 500 mg/d. He remains stable, but continues to smoke marijuana.

Our case illustrates that IPE may be a presenting feature of TLE. Because IPE may occur in patients who do not have a history of TLE, EEG monitoring should be considered in the workup of new-onset psychosis.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Elliott B, Joyce E, Shorvon S. Delusions, illusions and hallucinations in epilepsy: 2. complex phenomena and psychosis. Epilepsy Res. 2009;85(2-3):172-186.

2. Norton A, Massano J, Timóteo S, et al. "Full moon fits": focal temporal epilepsy presenting as first episode psychosis. Euro Psychiatry. 2009;24(suppl 1):1180.-

3. Cascella NG, Schretlen DJ, Sawa A. Schizophrenia and epilepsy: is there a shared susceptibility? Neurosci Res. 2009;63(4):227-235.

Interictal psychosis of epilepsy (IPE) is schizophrenia-like psychosis associated with epilepsy that cannot be directly linked to an ictus. IPE often is indistinguishable from primary schizophrenia. This phenomenon commonly occurs in patients with a history of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE); in those with frequent seizures; and in patients with a long history of epilepsy (>10 years).1 Interictal psychosis rarely precedes seizure activity2 and few cases have been reported. The epidemiology and clinical characteristics of IPE are poorly defined.3 We recently treated a patient with suspected IPE.

Mr. R, age 18, presented to our emergency department with his mother, who stated that her son was behaving strangely and had slow speech for 4 days. He had decreased social interaction, reduced appetite, poor hygiene, decreased sleep, and auditory hallucinations. Mr. R demonstrated hypervigilance and paranoia. He repeatedly checked rooms in his house for intruders. Mr. R also expressed suicidal ideation and exhibited cognitive decline of memory, attention, and fund of knowledge. His physical exam, routine laboratory investigations, CT, and MRI were within normal limits. Urine drug screen was positive for marijuana. We made a clinical diagnosis of acute psychosis.

Mr. R was admitted and started on ziprasidone, titrated to 160 mg/d; however, he could not tolerate this medication because of orthostatic hypotension. We discontinued ziprasidone and started risperidone, titrated to 4 mg/d. By day 4 Mr. R remained psychotic and marijuana intoxication was ruled out. EEG demonstrated rare intermittent left temporal sharp slow wave discharges and sharply contoured slow waves. This suggested an underlying seizure disorder, although Mr. R had no history of seizure.

The psychosis resolved 3 weeks later with risperidone, 2 mg/d, risperidone long-acting injection, 25 mg every 2 weeks, and carbamazepine, 400 mg/d. Mr. R was discharged home on these medications. He was noncompliant with treatment and continued to smoke marijuana. Four months later, Mr. R was rehospitalized for strange behavior. When seen in the outpatient clinic for follow-up, Mr. R admitted that he had his first witnessed seizure before his last hospitalization. Mr. R was restarted on risperidone, 4 mg/d, and risperidone long-acting injection, 25 mg every 2 weeks. To increase compliance, we switched carbamazepine to divalproex sodium extended-release, 500 mg/d. He remains stable, but continues to smoke marijuana.

Our case illustrates that IPE may be a presenting feature of TLE. Because IPE may occur in patients who do not have a history of TLE, EEG monitoring should be considered in the workup of new-onset psychosis.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Interictal psychosis of epilepsy (IPE) is schizophrenia-like psychosis associated with epilepsy that cannot be directly linked to an ictus. IPE often is indistinguishable from primary schizophrenia. This phenomenon commonly occurs in patients with a history of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE); in those with frequent seizures; and in patients with a long history of epilepsy (>10 years).1 Interictal psychosis rarely precedes seizure activity2 and few cases have been reported. The epidemiology and clinical characteristics of IPE are poorly defined.3 We recently treated a patient with suspected IPE.

Mr. R, age 18, presented to our emergency department with his mother, who stated that her son was behaving strangely and had slow speech for 4 days. He had decreased social interaction, reduced appetite, poor hygiene, decreased sleep, and auditory hallucinations. Mr. R demonstrated hypervigilance and paranoia. He repeatedly checked rooms in his house for intruders. Mr. R also expressed suicidal ideation and exhibited cognitive decline of memory, attention, and fund of knowledge. His physical exam, routine laboratory investigations, CT, and MRI were within normal limits. Urine drug screen was positive for marijuana. We made a clinical diagnosis of acute psychosis.

Mr. R was admitted and started on ziprasidone, titrated to 160 mg/d; however, he could not tolerate this medication because of orthostatic hypotension. We discontinued ziprasidone and started risperidone, titrated to 4 mg/d. By day 4 Mr. R remained psychotic and marijuana intoxication was ruled out. EEG demonstrated rare intermittent left temporal sharp slow wave discharges and sharply contoured slow waves. This suggested an underlying seizure disorder, although Mr. R had no history of seizure.

The psychosis resolved 3 weeks later with risperidone, 2 mg/d, risperidone long-acting injection, 25 mg every 2 weeks, and carbamazepine, 400 mg/d. Mr. R was discharged home on these medications. He was noncompliant with treatment and continued to smoke marijuana. Four months later, Mr. R was rehospitalized for strange behavior. When seen in the outpatient clinic for follow-up, Mr. R admitted that he had his first witnessed seizure before his last hospitalization. Mr. R was restarted on risperidone, 4 mg/d, and risperidone long-acting injection, 25 mg every 2 weeks. To increase compliance, we switched carbamazepine to divalproex sodium extended-release, 500 mg/d. He remains stable, but continues to smoke marijuana.

Our case illustrates that IPE may be a presenting feature of TLE. Because IPE may occur in patients who do not have a history of TLE, EEG monitoring should be considered in the workup of new-onset psychosis.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Elliott B, Joyce E, Shorvon S. Delusions, illusions and hallucinations in epilepsy: 2. complex phenomena and psychosis. Epilepsy Res. 2009;85(2-3):172-186.

2. Norton A, Massano J, Timóteo S, et al. "Full moon fits": focal temporal epilepsy presenting as first episode psychosis. Euro Psychiatry. 2009;24(suppl 1):1180.-

3. Cascella NG, Schretlen DJ, Sawa A. Schizophrenia and epilepsy: is there a shared susceptibility? Neurosci Res. 2009;63(4):227-235.

1. Elliott B, Joyce E, Shorvon S. Delusions, illusions and hallucinations in epilepsy: 2. complex phenomena and psychosis. Epilepsy Res. 2009;85(2-3):172-186.

2. Norton A, Massano J, Timóteo S, et al. "Full moon fits": focal temporal epilepsy presenting as first episode psychosis. Euro Psychiatry. 2009;24(suppl 1):1180.-

3. Cascella NG, Schretlen DJ, Sawa A. Schizophrenia and epilepsy: is there a shared susceptibility? Neurosci Res. 2009;63(4):227-235.

Treating depression in medical residents

Residents in psychiatry and other specialties experience depressive illness at rates similar to or higher than the general population. Residency training is a major psychosocial stressor.1 Having to master a large body of medical knowledge while facing feared inadequacy or failure creates a demanding emotional climate for physicians in training. When added to other mood disorder risk factors, such as genetic vulnerability and fatigue, continuous performance demands can lead to the onset of a major depressive episode. Assisting the newest members of our profession by providing needed mental health treatment can be challenging but rewarding.

Are residents ‘special’ patients?

Some residents who realize they are depressed are tempted to self-diagnose and self-prescribe or obtain informal consultation from peers or family members who are physicians. The best treatment for depressed residents is to provide the same meticulous, excellent, and thoughtful care that you provide for your nonphysician patients. Many depressed residents who seek psychiatric treatment are relieved to share their symptoms and stresses with a professional who is there to treat, not teach, them.2

Residents from nonpsychiatric specialties may be assessed and treated by psychiatry faculty at their home institutions or by providers in the community. For psychiatrists who supervise residents, establishing liaisons with private practice clinicians who can offer rapid treatment access for physicians in training can be effective. To avoid conflicts of interest, it is crucial that psychiatry residents are treated by providers other than their own faculty.

Factors that may lead residents to avoid seeking treatment include:

- The culture of medicine reinforces the stereotype that physicians are “strong” and “tough,” implying that the need for depression treatment is a weakness.

- Fear of stigma can extend to fear of receiving negative evaluations by supervisors if depression is acknowledged.

- Residents have logistic difficulties participating in treatment—a busy and inflexible schedule makes it hard to attend appointments.

- Altruism can hinder some residents from obtaining self-care. These residents may perceive a “good doctor” as one who is self-sacrificing for his or her patients.

Treatment

The same collaborative approach to establishing a healthy therapeutic relationship with nonphysician patients is equally effective with physicians in training. Residents usually are open to using evidence-based combined modalities, eg, pharmacotherapy and specific structured psychotherapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or interpersonal psychotherapy.

Occasionally a resident will lobby for special treatment. For example, a resident may insist that the psychiatrist rearrange other patients’ appointments to accommodate the resident’s schedule. Also, residents may be unwilling or unable to see themselves in the patient role. They may attempt to define their treatment in singular and distinctive ways, setting themselves apart from nonphysician patients. These barriers can be overcome by setting appropriate boundaries with patients early in treatment. It is the psychiatrist’s responsibility to gently but firmly set limits with residents so that treatment can be effective.

Disclosure

Dr. Gay reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Residents in psychiatry and other specialties experience depressive illness at rates similar to or higher than the general population. Residency training is a major psychosocial stressor.1 Having to master a large body of medical knowledge while facing feared inadequacy or failure creates a demanding emotional climate for physicians in training. When added to other mood disorder risk factors, such as genetic vulnerability and fatigue, continuous performance demands can lead to the onset of a major depressive episode. Assisting the newest members of our profession by providing needed mental health treatment can be challenging but rewarding.

Are residents ‘special’ patients?

Some residents who realize they are depressed are tempted to self-diagnose and self-prescribe or obtain informal consultation from peers or family members who are physicians. The best treatment for depressed residents is to provide the same meticulous, excellent, and thoughtful care that you provide for your nonphysician patients. Many depressed residents who seek psychiatric treatment are relieved to share their symptoms and stresses with a professional who is there to treat, not teach, them.2

Residents from nonpsychiatric specialties may be assessed and treated by psychiatry faculty at their home institutions or by providers in the community. For psychiatrists who supervise residents, establishing liaisons with private practice clinicians who can offer rapid treatment access for physicians in training can be effective. To avoid conflicts of interest, it is crucial that psychiatry residents are treated by providers other than their own faculty.

Factors that may lead residents to avoid seeking treatment include:

- The culture of medicine reinforces the stereotype that physicians are “strong” and “tough,” implying that the need for depression treatment is a weakness.

- Fear of stigma can extend to fear of receiving negative evaluations by supervisors if depression is acknowledged.

- Residents have logistic difficulties participating in treatment—a busy and inflexible schedule makes it hard to attend appointments.

- Altruism can hinder some residents from obtaining self-care. These residents may perceive a “good doctor” as one who is self-sacrificing for his or her patients.

Treatment

The same collaborative approach to establishing a healthy therapeutic relationship with nonphysician patients is equally effective with physicians in training. Residents usually are open to using evidence-based combined modalities, eg, pharmacotherapy and specific structured psychotherapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or interpersonal psychotherapy.

Occasionally a resident will lobby for special treatment. For example, a resident may insist that the psychiatrist rearrange other patients’ appointments to accommodate the resident’s schedule. Also, residents may be unwilling or unable to see themselves in the patient role. They may attempt to define their treatment in singular and distinctive ways, setting themselves apart from nonphysician patients. These barriers can be overcome by setting appropriate boundaries with patients early in treatment. It is the psychiatrist’s responsibility to gently but firmly set limits with residents so that treatment can be effective.

Disclosure

Dr. Gay reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Residents in psychiatry and other specialties experience depressive illness at rates similar to or higher than the general population. Residency training is a major psychosocial stressor.1 Having to master a large body of medical knowledge while facing feared inadequacy or failure creates a demanding emotional climate for physicians in training. When added to other mood disorder risk factors, such as genetic vulnerability and fatigue, continuous performance demands can lead to the onset of a major depressive episode. Assisting the newest members of our profession by providing needed mental health treatment can be challenging but rewarding.

Are residents ‘special’ patients?

Some residents who realize they are depressed are tempted to self-diagnose and self-prescribe or obtain informal consultation from peers or family members who are physicians. The best treatment for depressed residents is to provide the same meticulous, excellent, and thoughtful care that you provide for your nonphysician patients. Many depressed residents who seek psychiatric treatment are relieved to share their symptoms and stresses with a professional who is there to treat, not teach, them.2

Residents from nonpsychiatric specialties may be assessed and treated by psychiatry faculty at their home institutions or by providers in the community. For psychiatrists who supervise residents, establishing liaisons with private practice clinicians who can offer rapid treatment access for physicians in training can be effective. To avoid conflicts of interest, it is crucial that psychiatry residents are treated by providers other than their own faculty.

Factors that may lead residents to avoid seeking treatment include:

- The culture of medicine reinforces the stereotype that physicians are “strong” and “tough,” implying that the need for depression treatment is a weakness.

- Fear of stigma can extend to fear of receiving negative evaluations by supervisors if depression is acknowledged.

- Residents have logistic difficulties participating in treatment—a busy and inflexible schedule makes it hard to attend appointments.

- Altruism can hinder some residents from obtaining self-care. These residents may perceive a “good doctor” as one who is self-sacrificing for his or her patients.

Treatment

The same collaborative approach to establishing a healthy therapeutic relationship with nonphysician patients is equally effective with physicians in training. Residents usually are open to using evidence-based combined modalities, eg, pharmacotherapy and specific structured psychotherapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or interpersonal psychotherapy.

Occasionally a resident will lobby for special treatment. For example, a resident may insist that the psychiatrist rearrange other patients’ appointments to accommodate the resident’s schedule. Also, residents may be unwilling or unable to see themselves in the patient role. They may attempt to define their treatment in singular and distinctive ways, setting themselves apart from nonphysician patients. These barriers can be overcome by setting appropriate boundaries with patients early in treatment. It is the psychiatrist’s responsibility to gently but firmly set limits with residents so that treatment can be effective.

Disclosure

Dr. Gay reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Temporary tattoos: Alternative to adolescent self-harm?

Although self-harm behaviors such as burning or cutting are common among adolescents, they are a source of concern for parents and friends, and challenging to treat. Treatments have focused on distracting stimuli such as ice or the sting of a rubber band snapped on the wrist. Tattooing may be an alternative somatic strategy that can decrease self-harm and counter negative body image.1,2

In a study of 423 individuals with body modification (tattoos and piercings), 27% admitted to cutting themselves during childhood.3 This study’s authors concluded that these practices became a substitute for self-harm, helped patients overcome traumatic experiences, and improved satisfaction with body image.

In line with these observations, we decided to offer temporary tattooing to residents in our 60-bed child and adolescent treatment center. Patients were age 6 to 20 and 70% were female. We received consent from all patients’ guardians after explaining the temporary, nontoxic nature of the ink or decals.

Our first trials were with adolescent females with a history of cutting, but we offered temporary tattooing to all patients within a few months. Overall, 7 females and 3 males, all of whom had an axis I mood disorder, participated in temporary tattooing as an alternative to self-harm. We noted borderline personality traits in female patients who engaged in severe self-harm. Patients either drew on themselves or, with therapist supervision, “tattooed” other patients using self-selected designs.

One older teenage girl used cutting to manage flashbacks of sexual abuse from a family member. She had multiple scars from the cutting despite outpatient, hospital, and residential treatment over several years without symptom improvement. After 1 year of tattooing, her cutting episodes decreased from several times per month to once every 3 months. She also reported an improvement in positive perception of her body image from 0 on a 1-to-10 scale on admission to 5 at 1 year.

A younger teenage female without visible scars used cutting to manage feelings of being ugly associated with memories of sexual abuse. She reported that over 3 months, drawing tattoos improved her feelings about her body from 0/10 to 4/10, and she no longer reported thoughts of cutting or self-harm. Over 3 months, a male teenager without scars who cut himself when distressed about female relationships instead used tattoos to draw his conflicted feelings on his arm.

Tattoo designs included:

- flowers, vines, and roses

- patients’ psychological issues

- 2 faces for a patient dealing with internal and external relationship conflicts

- 2 flags to represent melding different cultures

- 2 hearts fused to represent issues with the intensities of love

- foreign words to indicate secrecy and alienation

- fantasy daydreams reflected as unicorns and dolphins.

Patients’ conversations with their therapists about the tattoos enabled detailed discussions about abuse, body image, and relationships.

Parents and some of our staff initially were concerned that temporary tattoos would increase self-harm or high-risk behaviors. This did not occur, perhaps because patients felt the designs helped them visually express feelings and conflicts.

Our clinical experience indicates that temporary tattooing may be a method of discussing and altering self-harm behaviors and negative body image in adolescent inpatients. Further evaluation of this strategy is warranted.

Disclosure

Dr. Masters reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Muehlenkamp JJ, Swanson DJ, Brausch AM. Self-objectification risk taking and self-harm in college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:24-32.

2. Carroll L, Anderson R. Body piercing tattooing, self-esteem, and body investment in adolescent girls. Adolescence. 2002;37:627-637.

3. Stirm A, Hinz A. Tattoos body piercings, and self injury: is there a connection? Investigations on a core group of participants practicing body modification. Psychother Res. 2008;18:326-333.

Although self-harm behaviors such as burning or cutting are common among adolescents, they are a source of concern for parents and friends, and challenging to treat. Treatments have focused on distracting stimuli such as ice or the sting of a rubber band snapped on the wrist. Tattooing may be an alternative somatic strategy that can decrease self-harm and counter negative body image.1,2

In a study of 423 individuals with body modification (tattoos and piercings), 27% admitted to cutting themselves during childhood.3 This study’s authors concluded that these practices became a substitute for self-harm, helped patients overcome traumatic experiences, and improved satisfaction with body image.

In line with these observations, we decided to offer temporary tattooing to residents in our 60-bed child and adolescent treatment center. Patients were age 6 to 20 and 70% were female. We received consent from all patients’ guardians after explaining the temporary, nontoxic nature of the ink or decals.

Our first trials were with adolescent females with a history of cutting, but we offered temporary tattooing to all patients within a few months. Overall, 7 females and 3 males, all of whom had an axis I mood disorder, participated in temporary tattooing as an alternative to self-harm. We noted borderline personality traits in female patients who engaged in severe self-harm. Patients either drew on themselves or, with therapist supervision, “tattooed” other patients using self-selected designs.

One older teenage girl used cutting to manage flashbacks of sexual abuse from a family member. She had multiple scars from the cutting despite outpatient, hospital, and residential treatment over several years without symptom improvement. After 1 year of tattooing, her cutting episodes decreased from several times per month to once every 3 months. She also reported an improvement in positive perception of her body image from 0 on a 1-to-10 scale on admission to 5 at 1 year.

A younger teenage female without visible scars used cutting to manage feelings of being ugly associated with memories of sexual abuse. She reported that over 3 months, drawing tattoos improved her feelings about her body from 0/10 to 4/10, and she no longer reported thoughts of cutting or self-harm. Over 3 months, a male teenager without scars who cut himself when distressed about female relationships instead used tattoos to draw his conflicted feelings on his arm.

Tattoo designs included:

- flowers, vines, and roses

- patients’ psychological issues

- 2 faces for a patient dealing with internal and external relationship conflicts

- 2 flags to represent melding different cultures

- 2 hearts fused to represent issues with the intensities of love