User login

Nodule on the left cheek

An 85-year-old man with a history of skin cancer presented to my dermatology practice (NT) for evaluation of a “pimple” on his left cheek that failed to resolve after 2 months (FIGURE). The patient noted that the lesion had grown, but that he otherwise felt well.

On examination, the lesion was plum colored, and the area was firm and nontender to palpation. The patient was referred to a plastic surgeon for an excisional biopsy to clarify the nature of the lesion.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Merkel cell carcinoma

A biopsy performed 2 weeks after the initial visit confirmed the clinical suspicion for Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

MCC is a cutaneous neuroendocrine malignancy. Although its name acknowledges similarities between the tumor cells and Merkel cells, it is now considered unlikely that Merkel cells are the actual cells of origin.1

The majority of MCCs are asymptomatic despite rapid growth and are typically red or pink and occur on UV-exposed areas, as in our patient.2 A cyst or acneiform lesion is the single most common diagnosis given at the time of biopsy.2

The incidence of MCC is greatest in people of advanced age and in those who are immunosuppressed. In the United States, the estimated annual incidence rate rose from 0.5 cases per 100,000 people in 2000 to 0.7 cases per 100,000 people in 2013.3 MCC increases exponentially with advancing age, from 0.1 (per 100,000) in those ages 40 to 44 years to 9.8 in those older than 85 years.3 The growing cohort of ageing baby boomers and the increased number of immunosuppressed individuals in the community suggest that clinicians are now more likely to encounter MCC than in the past.

While UV radiation is highly associated with MCC, the major causative factor is considered to be Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV).1 In fact, MCPyV has been linked to 80% of MCC cases.1,3 Most people have positive serology for MCPyV in early childhood, but the association between MCC and old age highlights the impact of immunosuppression on MCPyV activity and MCC development.1

Clinical suspicion is the first step in diagnosing MCC

The mnemonic AEIOU highlights the key clinical features of this aggressive tumor2,4:

- Asymptomatic

- Expanding rapidly (often grows in less than 3 months)

- Immune suppression (eg, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, solid organ transplant patient)

- Older than 50

- UV exposure on fair skin.

If a lesion is suspected to be MCC, the next step includes biopsy so that a definitive diagnosis can be made. A firm, nontender nodule that lacks fluctuance should raise suspicion for a neoplastic process.

Continue to: The differential is broad, ranging from cysts to melanoma

The differential is broad, ranging from cysts to melanoma

The differential diagnosis for an enlarging, plum-colored nodule on sun-exposed skin includes an abscess, a ruptured or inflamed epidermoid cyst, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.

An abscess is typically tender and expands within a matter of days rather than months.

A cyst can be ruled out by the clinical appearance and lack of an overlying pore.

Basal cell carcinoma can be characterized by a rolled border and central ulceration.

Squamous cell carcinomas often exhibit a verrucous surface with marked hyperkeratosis.

Continue to: Melanoma

Melanoma manifests with brown or irregular pigmentation and may be associated with a precursor lesion.

Tx includes excision and consistent follow-up

Complete excision is the critical first step to successful therapy. Sentinel lymph node studies are typically performed because of the high incidence of lymph node metastasis. Frequent follow-up is required because of the high risk of recurrent or persistent disease.

Local recurrence usually occurs within 1 year of diagnosis in more than 40% of patients.5 Distant metastasis can be treated with a programmed cell death ligand 1 blocking agent (avelumab) or a programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitor (nivolumab or pembrolizumab).6

Our patient was referred to a regional cancer center for sentinel lymph node evaluation, where he was found to have nodal disease. The patient was put on pembrolizumab and received radiation therapy but showed only limited response. Seven months after diagnosis, he passed away from metastatic MCC.

1. Pietropaolo V, Prezioso C, Moens U. Merkel cell polyomavirus and Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:1774. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071774

2. Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.020

3. Paulson KG, Park SY, Vandeven NA, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:457-463.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.028

4. Voelker R. Why Merkel cell cancer is garnering more attention. JAMA. 2018;320:18-20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7042

5. Allen PJ, Browne WB, Jacques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.329

6. D’Angelo SP, Russell J, Lebbé C, et al. Efficacy and safety of first-line avelumab treatment in patients with stage IV metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a preplanned interim analysis of a clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:e180077. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0077

An 85-year-old man with a history of skin cancer presented to my dermatology practice (NT) for evaluation of a “pimple” on his left cheek that failed to resolve after 2 months (FIGURE). The patient noted that the lesion had grown, but that he otherwise felt well.

On examination, the lesion was plum colored, and the area was firm and nontender to palpation. The patient was referred to a plastic surgeon for an excisional biopsy to clarify the nature of the lesion.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Merkel cell carcinoma

A biopsy performed 2 weeks after the initial visit confirmed the clinical suspicion for Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

MCC is a cutaneous neuroendocrine malignancy. Although its name acknowledges similarities between the tumor cells and Merkel cells, it is now considered unlikely that Merkel cells are the actual cells of origin.1

The majority of MCCs are asymptomatic despite rapid growth and are typically red or pink and occur on UV-exposed areas, as in our patient.2 A cyst or acneiform lesion is the single most common diagnosis given at the time of biopsy.2

The incidence of MCC is greatest in people of advanced age and in those who are immunosuppressed. In the United States, the estimated annual incidence rate rose from 0.5 cases per 100,000 people in 2000 to 0.7 cases per 100,000 people in 2013.3 MCC increases exponentially with advancing age, from 0.1 (per 100,000) in those ages 40 to 44 years to 9.8 in those older than 85 years.3 The growing cohort of ageing baby boomers and the increased number of immunosuppressed individuals in the community suggest that clinicians are now more likely to encounter MCC than in the past.

While UV radiation is highly associated with MCC, the major causative factor is considered to be Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV).1 In fact, MCPyV has been linked to 80% of MCC cases.1,3 Most people have positive serology for MCPyV in early childhood, but the association between MCC and old age highlights the impact of immunosuppression on MCPyV activity and MCC development.1

Clinical suspicion is the first step in diagnosing MCC

The mnemonic AEIOU highlights the key clinical features of this aggressive tumor2,4:

- Asymptomatic

- Expanding rapidly (often grows in less than 3 months)

- Immune suppression (eg, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, solid organ transplant patient)

- Older than 50

- UV exposure on fair skin.

If a lesion is suspected to be MCC, the next step includes biopsy so that a definitive diagnosis can be made. A firm, nontender nodule that lacks fluctuance should raise suspicion for a neoplastic process.

Continue to: The differential is broad, ranging from cysts to melanoma

The differential is broad, ranging from cysts to melanoma

The differential diagnosis for an enlarging, plum-colored nodule on sun-exposed skin includes an abscess, a ruptured or inflamed epidermoid cyst, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.

An abscess is typically tender and expands within a matter of days rather than months.

A cyst can be ruled out by the clinical appearance and lack of an overlying pore.

Basal cell carcinoma can be characterized by a rolled border and central ulceration.

Squamous cell carcinomas often exhibit a verrucous surface with marked hyperkeratosis.

Continue to: Melanoma

Melanoma manifests with brown or irregular pigmentation and may be associated with a precursor lesion.

Tx includes excision and consistent follow-up

Complete excision is the critical first step to successful therapy. Sentinel lymph node studies are typically performed because of the high incidence of lymph node metastasis. Frequent follow-up is required because of the high risk of recurrent or persistent disease.

Local recurrence usually occurs within 1 year of diagnosis in more than 40% of patients.5 Distant metastasis can be treated with a programmed cell death ligand 1 blocking agent (avelumab) or a programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitor (nivolumab or pembrolizumab).6

Our patient was referred to a regional cancer center for sentinel lymph node evaluation, where he was found to have nodal disease. The patient was put on pembrolizumab and received radiation therapy but showed only limited response. Seven months after diagnosis, he passed away from metastatic MCC.

An 85-year-old man with a history of skin cancer presented to my dermatology practice (NT) for evaluation of a “pimple” on his left cheek that failed to resolve after 2 months (FIGURE). The patient noted that the lesion had grown, but that he otherwise felt well.

On examination, the lesion was plum colored, and the area was firm and nontender to palpation. The patient was referred to a plastic surgeon for an excisional biopsy to clarify the nature of the lesion.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Merkel cell carcinoma

A biopsy performed 2 weeks after the initial visit confirmed the clinical suspicion for Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

MCC is a cutaneous neuroendocrine malignancy. Although its name acknowledges similarities between the tumor cells and Merkel cells, it is now considered unlikely that Merkel cells are the actual cells of origin.1

The majority of MCCs are asymptomatic despite rapid growth and are typically red or pink and occur on UV-exposed areas, as in our patient.2 A cyst or acneiform lesion is the single most common diagnosis given at the time of biopsy.2

The incidence of MCC is greatest in people of advanced age and in those who are immunosuppressed. In the United States, the estimated annual incidence rate rose from 0.5 cases per 100,000 people in 2000 to 0.7 cases per 100,000 people in 2013.3 MCC increases exponentially with advancing age, from 0.1 (per 100,000) in those ages 40 to 44 years to 9.8 in those older than 85 years.3 The growing cohort of ageing baby boomers and the increased number of immunosuppressed individuals in the community suggest that clinicians are now more likely to encounter MCC than in the past.

While UV radiation is highly associated with MCC, the major causative factor is considered to be Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV).1 In fact, MCPyV has been linked to 80% of MCC cases.1,3 Most people have positive serology for MCPyV in early childhood, but the association between MCC and old age highlights the impact of immunosuppression on MCPyV activity and MCC development.1

Clinical suspicion is the first step in diagnosing MCC

The mnemonic AEIOU highlights the key clinical features of this aggressive tumor2,4:

- Asymptomatic

- Expanding rapidly (often grows in less than 3 months)

- Immune suppression (eg, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, solid organ transplant patient)

- Older than 50

- UV exposure on fair skin.

If a lesion is suspected to be MCC, the next step includes biopsy so that a definitive diagnosis can be made. A firm, nontender nodule that lacks fluctuance should raise suspicion for a neoplastic process.

Continue to: The differential is broad, ranging from cysts to melanoma

The differential is broad, ranging from cysts to melanoma

The differential diagnosis for an enlarging, plum-colored nodule on sun-exposed skin includes an abscess, a ruptured or inflamed epidermoid cyst, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.

An abscess is typically tender and expands within a matter of days rather than months.

A cyst can be ruled out by the clinical appearance and lack of an overlying pore.

Basal cell carcinoma can be characterized by a rolled border and central ulceration.

Squamous cell carcinomas often exhibit a verrucous surface with marked hyperkeratosis.

Continue to: Melanoma

Melanoma manifests with brown or irregular pigmentation and may be associated with a precursor lesion.

Tx includes excision and consistent follow-up

Complete excision is the critical first step to successful therapy. Sentinel lymph node studies are typically performed because of the high incidence of lymph node metastasis. Frequent follow-up is required because of the high risk of recurrent or persistent disease.

Local recurrence usually occurs within 1 year of diagnosis in more than 40% of patients.5 Distant metastasis can be treated with a programmed cell death ligand 1 blocking agent (avelumab) or a programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitor (nivolumab or pembrolizumab).6

Our patient was referred to a regional cancer center for sentinel lymph node evaluation, where he was found to have nodal disease. The patient was put on pembrolizumab and received radiation therapy but showed only limited response. Seven months after diagnosis, he passed away from metastatic MCC.

1. Pietropaolo V, Prezioso C, Moens U. Merkel cell polyomavirus and Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:1774. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071774

2. Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.020

3. Paulson KG, Park SY, Vandeven NA, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:457-463.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.028

4. Voelker R. Why Merkel cell cancer is garnering more attention. JAMA. 2018;320:18-20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7042

5. Allen PJ, Browne WB, Jacques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.329

6. D’Angelo SP, Russell J, Lebbé C, et al. Efficacy and safety of first-line avelumab treatment in patients with stage IV metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a preplanned interim analysis of a clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:e180077. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0077

1. Pietropaolo V, Prezioso C, Moens U. Merkel cell polyomavirus and Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:1774. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071774

2. Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.020

3. Paulson KG, Park SY, Vandeven NA, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:457-463.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.028

4. Voelker R. Why Merkel cell cancer is garnering more attention. JAMA. 2018;320:18-20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7042

5. Allen PJ, Browne WB, Jacques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.329

6. D’Angelo SP, Russell J, Lebbé C, et al. Efficacy and safety of first-line avelumab treatment in patients with stage IV metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a preplanned interim analysis of a clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:e180077. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0077

Dark plaque on back of ear

Dermoscopic findings were consistent with a melanocytic lesion and a scoop shave biopsy revealed a 2.7 mm thick nodular melanoma.

Melanoma is the most lethal skin cancer in the United States. The likelihood of metastatic spread to lymph nodes statistically increases beyond a probability of 5% when patients have primary lesions thicker than 0.8 mm.1 Thus, for patients with tumors thicker than 0.8 mm, or some other high-risk features such as high mitotic index, a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is recommended. This patient underwent wide local excision and reconstruction of his ear. An SLNB was also performed and the results were negative.

The patient returned for a complete skin exam every 3 months. Ten months after the excision, he presented with episodes of headache and confusion. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed metastasis to the brain; a biopsy confirmed that it was melanoma. Two months later, after attempts at resection of the brain metastasis, the patient died.

This case demonstrates that patients with thick melanoma are at continued risk for recurrence and poor outcomes; they benefit from close surveillance and work-up of unusual symptoms that might suggest metastases. Phase 3 trials are currently underway to consider the use of adjuvant therapy in patients with advanced stage II melanoma who, on average, have worse outcomes than patients with early-stage III disease.2

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2022 Melanoma: Cutaneous. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. December 3, 2021. Accessed January 4, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cutaneous_melanoma.pdf

2. Poklepovic AS, Luke JJ. Considering adjuvant therapy for stage II melanoma. Cancer. 2020;126:1166-1174. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32585

Dermoscopic findings were consistent with a melanocytic lesion and a scoop shave biopsy revealed a 2.7 mm thick nodular melanoma.

Melanoma is the most lethal skin cancer in the United States. The likelihood of metastatic spread to lymph nodes statistically increases beyond a probability of 5% when patients have primary lesions thicker than 0.8 mm.1 Thus, for patients with tumors thicker than 0.8 mm, or some other high-risk features such as high mitotic index, a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is recommended. This patient underwent wide local excision and reconstruction of his ear. An SLNB was also performed and the results were negative.

The patient returned for a complete skin exam every 3 months. Ten months after the excision, he presented with episodes of headache and confusion. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed metastasis to the brain; a biopsy confirmed that it was melanoma. Two months later, after attempts at resection of the brain metastasis, the patient died.

This case demonstrates that patients with thick melanoma are at continued risk for recurrence and poor outcomes; they benefit from close surveillance and work-up of unusual symptoms that might suggest metastases. Phase 3 trials are currently underway to consider the use of adjuvant therapy in patients with advanced stage II melanoma who, on average, have worse outcomes than patients with early-stage III disease.2

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Dermoscopic findings were consistent with a melanocytic lesion and a scoop shave biopsy revealed a 2.7 mm thick nodular melanoma.

Melanoma is the most lethal skin cancer in the United States. The likelihood of metastatic spread to lymph nodes statistically increases beyond a probability of 5% when patients have primary lesions thicker than 0.8 mm.1 Thus, for patients with tumors thicker than 0.8 mm, or some other high-risk features such as high mitotic index, a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is recommended. This patient underwent wide local excision and reconstruction of his ear. An SLNB was also performed and the results were negative.

The patient returned for a complete skin exam every 3 months. Ten months after the excision, he presented with episodes of headache and confusion. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed metastasis to the brain; a biopsy confirmed that it was melanoma. Two months later, after attempts at resection of the brain metastasis, the patient died.

This case demonstrates that patients with thick melanoma are at continued risk for recurrence and poor outcomes; they benefit from close surveillance and work-up of unusual symptoms that might suggest metastases. Phase 3 trials are currently underway to consider the use of adjuvant therapy in patients with advanced stage II melanoma who, on average, have worse outcomes than patients with early-stage III disease.2

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2022 Melanoma: Cutaneous. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. December 3, 2021. Accessed January 4, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cutaneous_melanoma.pdf

2. Poklepovic AS, Luke JJ. Considering adjuvant therapy for stage II melanoma. Cancer. 2020;126:1166-1174. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32585

1. NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2022 Melanoma: Cutaneous. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. December 3, 2021. Accessed January 4, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cutaneous_melanoma.pdf

2. Poklepovic AS, Luke JJ. Considering adjuvant therapy for stage II melanoma. Cancer. 2020;126:1166-1174. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32585

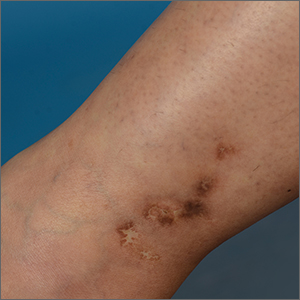

Plaque on heel

Physical exam revealed a plaque with multiple verrucous projections and clusters of smaller circular papules, all with associated thrombosed vessels. The plaque interrupted normal skin lines, consistent with a large, benign, plantar wart, also termed a mosaic wart when clusters of individual plantar warts form a single plaque.

Mosaic warts are caused by infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). They begin as individual papules or macules with a rough surface and small pinpoint capillaries. Plantar warts can be painful if located over a weight-bearing area of the foot. Plantar warts spread by autoinoculation from microtrauma to the foot. Picking at the wart, having it rub against a shoe insert, or exposing it to contaminated surfaces (such as a shower floor) can lead to the wart’s spread. Usually, the diagnosis of a plantar wart is based on clinical examination, with the main differential including a corn or callus. However, rare instances of squamous cell carcinoma or arsenical keratoses can mimic a plantar wart.

Although plantar warts can resolve spontaneously over months or years, patients often seek treatment. Warts may require multiple treatments and various therapies. Common first-line therapies include over-the-counter (OTC) salicylic acid and cryotherapy. The list of other therapies is lengthy, with no single agent credited with high cure rates in well-controlled trials. These therapies include intralesional candida antigen, topical 5 fluorouracil, and topical imiquimod, among many others.

Salicylic acid is available in several forms including 40% acid pads that may be cut to size and applied daily to affected areas. These pads may need to be reinforced with tape to improve adherence. Salicylic acid is also available as a 17% paint-on formulation that can be applied daily, with or without occlusion. This treatment usually requires 2 to 3 months of daily application.

When treated in the office, cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen (LN2) is a first-line therapy, with a cure rate of approximately 65%—similar to that of OTC salicylic acid.1 Application of LN2 via a spray cannister every 2 to 4 weeks until clear is a common strategy. Freezing the area, letting it thaw, and repeating the freeze again in 1 sitting improves clearance. Pain from LN2 can be significant and not all patients can tolerate it. However, for a motivated patient, this can be more convenient than home treatments or a good option when home treatment has failed.

This patient chose cryotherapy, and his foot cleared completely after several rounds of in-office treatments.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Lipke MM. An armamentarium of wart treatments. Clin Med Res. 2006;4:273-293. doi: 10.3121/cmr.4.4.273

Physical exam revealed a plaque with multiple verrucous projections and clusters of smaller circular papules, all with associated thrombosed vessels. The plaque interrupted normal skin lines, consistent with a large, benign, plantar wart, also termed a mosaic wart when clusters of individual plantar warts form a single plaque.

Mosaic warts are caused by infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). They begin as individual papules or macules with a rough surface and small pinpoint capillaries. Plantar warts can be painful if located over a weight-bearing area of the foot. Plantar warts spread by autoinoculation from microtrauma to the foot. Picking at the wart, having it rub against a shoe insert, or exposing it to contaminated surfaces (such as a shower floor) can lead to the wart’s spread. Usually, the diagnosis of a plantar wart is based on clinical examination, with the main differential including a corn or callus. However, rare instances of squamous cell carcinoma or arsenical keratoses can mimic a plantar wart.

Although plantar warts can resolve spontaneously over months or years, patients often seek treatment. Warts may require multiple treatments and various therapies. Common first-line therapies include over-the-counter (OTC) salicylic acid and cryotherapy. The list of other therapies is lengthy, with no single agent credited with high cure rates in well-controlled trials. These therapies include intralesional candida antigen, topical 5 fluorouracil, and topical imiquimod, among many others.

Salicylic acid is available in several forms including 40% acid pads that may be cut to size and applied daily to affected areas. These pads may need to be reinforced with tape to improve adherence. Salicylic acid is also available as a 17% paint-on formulation that can be applied daily, with or without occlusion. This treatment usually requires 2 to 3 months of daily application.

When treated in the office, cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen (LN2) is a first-line therapy, with a cure rate of approximately 65%—similar to that of OTC salicylic acid.1 Application of LN2 via a spray cannister every 2 to 4 weeks until clear is a common strategy. Freezing the area, letting it thaw, and repeating the freeze again in 1 sitting improves clearance. Pain from LN2 can be significant and not all patients can tolerate it. However, for a motivated patient, this can be more convenient than home treatments or a good option when home treatment has failed.

This patient chose cryotherapy, and his foot cleared completely after several rounds of in-office treatments.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Physical exam revealed a plaque with multiple verrucous projections and clusters of smaller circular papules, all with associated thrombosed vessels. The plaque interrupted normal skin lines, consistent with a large, benign, plantar wart, also termed a mosaic wart when clusters of individual plantar warts form a single plaque.

Mosaic warts are caused by infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). They begin as individual papules or macules with a rough surface and small pinpoint capillaries. Plantar warts can be painful if located over a weight-bearing area of the foot. Plantar warts spread by autoinoculation from microtrauma to the foot. Picking at the wart, having it rub against a shoe insert, or exposing it to contaminated surfaces (such as a shower floor) can lead to the wart’s spread. Usually, the diagnosis of a plantar wart is based on clinical examination, with the main differential including a corn or callus. However, rare instances of squamous cell carcinoma or arsenical keratoses can mimic a plantar wart.

Although plantar warts can resolve spontaneously over months or years, patients often seek treatment. Warts may require multiple treatments and various therapies. Common first-line therapies include over-the-counter (OTC) salicylic acid and cryotherapy. The list of other therapies is lengthy, with no single agent credited with high cure rates in well-controlled trials. These therapies include intralesional candida antigen, topical 5 fluorouracil, and topical imiquimod, among many others.

Salicylic acid is available in several forms including 40% acid pads that may be cut to size and applied daily to affected areas. These pads may need to be reinforced with tape to improve adherence. Salicylic acid is also available as a 17% paint-on formulation that can be applied daily, with or without occlusion. This treatment usually requires 2 to 3 months of daily application.

When treated in the office, cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen (LN2) is a first-line therapy, with a cure rate of approximately 65%—similar to that of OTC salicylic acid.1 Application of LN2 via a spray cannister every 2 to 4 weeks until clear is a common strategy. Freezing the area, letting it thaw, and repeating the freeze again in 1 sitting improves clearance. Pain from LN2 can be significant and not all patients can tolerate it. However, for a motivated patient, this can be more convenient than home treatments or a good option when home treatment has failed.

This patient chose cryotherapy, and his foot cleared completely after several rounds of in-office treatments.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Lipke MM. An armamentarium of wart treatments. Clin Med Res. 2006;4:273-293. doi: 10.3121/cmr.4.4.273

1. Lipke MM. An armamentarium of wart treatments. Clin Med Res. 2006;4:273-293. doi: 10.3121/cmr.4.4.273

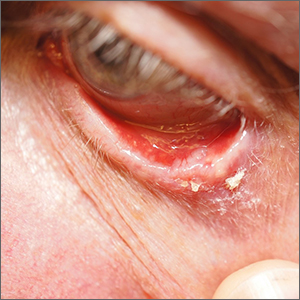

Growth on eyelid

A shave biopsy (performed carefully to avoid caustic hemostatic agents irritating the conjunctiva) confirmed the diagnosis of a micronodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

BCC is a common tumor occurring on the eyelids and in the periocular region. Any new growing papule on the eyelids, history of focal bleeding, irritation, or focal loss of eyelashes should cause suspicion for BCC. Patients are often unaware of any symptoms when lesions begin, highlighting the importance of close inspection of the eyelids when skin or eye exams are performed. The differential diagnosis includes benign lesions such as hidrocystomas and nevi, as well as malignancies, including sebaceous carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.1

Factors that come into play when exploring eyelid BCC treatment options include tumor removal, eyelid function, and appearance. The potential morbidity associated with tumor spread in the periorbital region highlights the importance of early detection of eyelid cancers. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a first choice for tumor removal of an eyelid BCC and offers a high cure rate with minimal tissue removal.

Removal of an eyelid BCC may be a multidisciplinary endeavor with MMS achieving a clear margin, and Ophthalmology or Oculoplastics following with repair and closure soon after. Patients who can’t tolerate surgery should consider vismodegib, a targeted chemotherapy, or radiotherapy.

The patient in this case opted for a single staged excision and repair with Oculoplastics and has had no recurrence. He subsequently underwent a revision procedure to improve ectropion.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Shi Y, Jia R, Fan X. Ocular basal cell carcinoma: a brief literature review of clinical diagnosis and treatment. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:2483-2489. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S130371

A shave biopsy (performed carefully to avoid caustic hemostatic agents irritating the conjunctiva) confirmed the diagnosis of a micronodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

BCC is a common tumor occurring on the eyelids and in the periocular region. Any new growing papule on the eyelids, history of focal bleeding, irritation, or focal loss of eyelashes should cause suspicion for BCC. Patients are often unaware of any symptoms when lesions begin, highlighting the importance of close inspection of the eyelids when skin or eye exams are performed. The differential diagnosis includes benign lesions such as hidrocystomas and nevi, as well as malignancies, including sebaceous carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.1

Factors that come into play when exploring eyelid BCC treatment options include tumor removal, eyelid function, and appearance. The potential morbidity associated with tumor spread in the periorbital region highlights the importance of early detection of eyelid cancers. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a first choice for tumor removal of an eyelid BCC and offers a high cure rate with minimal tissue removal.

Removal of an eyelid BCC may be a multidisciplinary endeavor with MMS achieving a clear margin, and Ophthalmology or Oculoplastics following with repair and closure soon after. Patients who can’t tolerate surgery should consider vismodegib, a targeted chemotherapy, or radiotherapy.

The patient in this case opted for a single staged excision and repair with Oculoplastics and has had no recurrence. He subsequently underwent a revision procedure to improve ectropion.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

A shave biopsy (performed carefully to avoid caustic hemostatic agents irritating the conjunctiva) confirmed the diagnosis of a micronodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

BCC is a common tumor occurring on the eyelids and in the periocular region. Any new growing papule on the eyelids, history of focal bleeding, irritation, or focal loss of eyelashes should cause suspicion for BCC. Patients are often unaware of any symptoms when lesions begin, highlighting the importance of close inspection of the eyelids when skin or eye exams are performed. The differential diagnosis includes benign lesions such as hidrocystomas and nevi, as well as malignancies, including sebaceous carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.1

Factors that come into play when exploring eyelid BCC treatment options include tumor removal, eyelid function, and appearance. The potential morbidity associated with tumor spread in the periorbital region highlights the importance of early detection of eyelid cancers. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a first choice for tumor removal of an eyelid BCC and offers a high cure rate with minimal tissue removal.

Removal of an eyelid BCC may be a multidisciplinary endeavor with MMS achieving a clear margin, and Ophthalmology or Oculoplastics following with repair and closure soon after. Patients who can’t tolerate surgery should consider vismodegib, a targeted chemotherapy, or radiotherapy.

The patient in this case opted for a single staged excision and repair with Oculoplastics and has had no recurrence. He subsequently underwent a revision procedure to improve ectropion.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Shi Y, Jia R, Fan X. Ocular basal cell carcinoma: a brief literature review of clinical diagnosis and treatment. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:2483-2489. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S130371

1. Shi Y, Jia R, Fan X. Ocular basal cell carcinoma: a brief literature review of clinical diagnosis and treatment. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:2483-2489. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S130371

Wrist pain and swelling

Bilateral wrist pain with associated swelling consistent with synovitis pointed to an inflammatory arthritis confirmed by x-ray imaging. An elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (109 mm/hr), rheumatoid factor (314 IU/mL), and cyclic citrullinated peptide (34.5 EU/mL) confirmed the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Hepatitis and tuberculosis screens were negative and uric acid was normal.

The patient’s radiographic imaging of the wrists revealed mild-to-moderate narrowing of the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints, multiple scattered cyst-like and erosive changes throughout, and mild-to-moderate soft tissue edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of RA. Additionally, the radiographs showed cortical irregularity of the proximal ulnar aspect of the lunate, consistent with ulnar abutment syndrome, a degenerative condition in which the ulnar head abuts the triangular fibrocartilage complex and ulnar-sided carpal bones.

Some of the first changes that can be observed radiographically in RA include soft tissue swelling and periarticular osteopenia.1 As the disease progresses, bony erosions, especially in the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, can be observed. Additional findings with active disease include joint space narrowing and deformities, such as joint subluxation. Erosions of cartilage and bone can also occur in some other forms of inflammatory and gouty arthropathies, so it is important to consider differential diagnoses in the case of ambiguous laboratory findings.

The primary disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) used for treatment of RA is methotrexate.2 DMARDs take weeks to months before there is noticeable improvement and should be used in combination with anti-inflammatory agents such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or glucocorticoids. Response rates to DMARDs decrease over time. In the case of drug resistance, combination therapy (eg, methotrexate plus sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine, or methotrexate plus a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor) can be used. For acute flares, patients can undergo intra-articular glucocorticoid injections if a limited number of joints are affected. Widespread flares can be treated with oral glucocorticoids. Severe flares can be treated with pulse intravenous methylprednisolone.

Our patient was referred to Rheumatology for prompt treatment. He was started on DMARD therapy (methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly) with daily folic acid and a plan to increase the methotrexate to 25 mg after the third week of therapy. He was also prescribed oral prednisone to have on hand for flares, and azithromycin to treat possible future infections. Additionally, the patient underwent bilateral steroid wrist injections at the clinic.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Rachel Ruckman, BS, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. van der Heijde DM, van Leeuwen MA, van Riel PL, et al. Biannual radiographic assessments of hands and feet in a three-year prospective followup of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:26-34. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350105

2. Lee DM, Weinblatt ME. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2001;358:903-911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06075-5

Bilateral wrist pain with associated swelling consistent with synovitis pointed to an inflammatory arthritis confirmed by x-ray imaging. An elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (109 mm/hr), rheumatoid factor (314 IU/mL), and cyclic citrullinated peptide (34.5 EU/mL) confirmed the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Hepatitis and tuberculosis screens were negative and uric acid was normal.

The patient’s radiographic imaging of the wrists revealed mild-to-moderate narrowing of the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints, multiple scattered cyst-like and erosive changes throughout, and mild-to-moderate soft tissue edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of RA. Additionally, the radiographs showed cortical irregularity of the proximal ulnar aspect of the lunate, consistent with ulnar abutment syndrome, a degenerative condition in which the ulnar head abuts the triangular fibrocartilage complex and ulnar-sided carpal bones.

Some of the first changes that can be observed radiographically in RA include soft tissue swelling and periarticular osteopenia.1 As the disease progresses, bony erosions, especially in the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, can be observed. Additional findings with active disease include joint space narrowing and deformities, such as joint subluxation. Erosions of cartilage and bone can also occur in some other forms of inflammatory and gouty arthropathies, so it is important to consider differential diagnoses in the case of ambiguous laboratory findings.

The primary disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) used for treatment of RA is methotrexate.2 DMARDs take weeks to months before there is noticeable improvement and should be used in combination with anti-inflammatory agents such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or glucocorticoids. Response rates to DMARDs decrease over time. In the case of drug resistance, combination therapy (eg, methotrexate plus sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine, or methotrexate plus a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor) can be used. For acute flares, patients can undergo intra-articular glucocorticoid injections if a limited number of joints are affected. Widespread flares can be treated with oral glucocorticoids. Severe flares can be treated with pulse intravenous methylprednisolone.

Our patient was referred to Rheumatology for prompt treatment. He was started on DMARD therapy (methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly) with daily folic acid and a plan to increase the methotrexate to 25 mg after the third week of therapy. He was also prescribed oral prednisone to have on hand for flares, and azithromycin to treat possible future infections. Additionally, the patient underwent bilateral steroid wrist injections at the clinic.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Rachel Ruckman, BS, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Bilateral wrist pain with associated swelling consistent with synovitis pointed to an inflammatory arthritis confirmed by x-ray imaging. An elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (109 mm/hr), rheumatoid factor (314 IU/mL), and cyclic citrullinated peptide (34.5 EU/mL) confirmed the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Hepatitis and tuberculosis screens were negative and uric acid was normal.

The patient’s radiographic imaging of the wrists revealed mild-to-moderate narrowing of the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints, multiple scattered cyst-like and erosive changes throughout, and mild-to-moderate soft tissue edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of RA. Additionally, the radiographs showed cortical irregularity of the proximal ulnar aspect of the lunate, consistent with ulnar abutment syndrome, a degenerative condition in which the ulnar head abuts the triangular fibrocartilage complex and ulnar-sided carpal bones.

Some of the first changes that can be observed radiographically in RA include soft tissue swelling and periarticular osteopenia.1 As the disease progresses, bony erosions, especially in the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, can be observed. Additional findings with active disease include joint space narrowing and deformities, such as joint subluxation. Erosions of cartilage and bone can also occur in some other forms of inflammatory and gouty arthropathies, so it is important to consider differential diagnoses in the case of ambiguous laboratory findings.

The primary disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) used for treatment of RA is methotrexate.2 DMARDs take weeks to months before there is noticeable improvement and should be used in combination with anti-inflammatory agents such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or glucocorticoids. Response rates to DMARDs decrease over time. In the case of drug resistance, combination therapy (eg, methotrexate plus sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine, or methotrexate plus a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor) can be used. For acute flares, patients can undergo intra-articular glucocorticoid injections if a limited number of joints are affected. Widespread flares can be treated with oral glucocorticoids. Severe flares can be treated with pulse intravenous methylprednisolone.

Our patient was referred to Rheumatology for prompt treatment. He was started on DMARD therapy (methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly) with daily folic acid and a plan to increase the methotrexate to 25 mg after the third week of therapy. He was also prescribed oral prednisone to have on hand for flares, and azithromycin to treat possible future infections. Additionally, the patient underwent bilateral steroid wrist injections at the clinic.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Rachel Ruckman, BS, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. van der Heijde DM, van Leeuwen MA, van Riel PL, et al. Biannual radiographic assessments of hands and feet in a three-year prospective followup of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:26-34. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350105

2. Lee DM, Weinblatt ME. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2001;358:903-911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06075-5

1. van der Heijde DM, van Leeuwen MA, van Riel PL, et al. Biannual radiographic assessments of hands and feet in a three-year prospective followup of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:26-34. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350105

2. Lee DM, Weinblatt ME. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2001;358:903-911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06075-5

Wrist rash

The gradual development of a rash in an area of frequent direct contact between metal and skin is pathognomonic for allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). Contact dermatitis often results from exposure to metals. Stainless steel is a group of ferrous alloys composed of a variety of elements including nickel, which is added to increase corrosion resistance. Unfortunately, nickel is a metal commonly known to induce a delayed hypersensitivity response. In the upper left corner of the image shown here, one can see the metal plate of the watch band.

ACD is a T-cell mediated, delayed, type IV hypersensitivity response to foreign materials.1 These reactions typically occur around 48 to 72 hours following contact with the metal but can take weeks to appear, depending on the amount of T-cell activation. Symptoms may appear more rapidly on repeat exposures. Lesions manifest as erythematous, scaly plaques, which may include vesicles and bullae in severe cases.

The mainstay of treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is avoidance of the allergen once it has been identified. Nickel is commonly found in metal parts on clothing and in jewelry. One method of protection from nickel in these cases is to cover the metal that touches the skin with a clear nail polish or another clear barrier (commercial options are available). Duct tape or fabric can also be used to cover the metal.

Topical corticosteroids are the first-line therapy to treat lesions. Topical calcineurin inhibitors are an alternative. Systemic corticosteroids may be indicated if there is extensive body surface area involvement. Phototherapy or systemic immunosuppression may be considered in severe refractory cases.

Our patient was counseled on the nature of the disease process and educated on strategies to avoid future exposures. Treatment was initiated with topical triamcinolone 0.1% ointment with follow-up as needed.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Spenser Squire, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1029-1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

The gradual development of a rash in an area of frequent direct contact between metal and skin is pathognomonic for allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). Contact dermatitis often results from exposure to metals. Stainless steel is a group of ferrous alloys composed of a variety of elements including nickel, which is added to increase corrosion resistance. Unfortunately, nickel is a metal commonly known to induce a delayed hypersensitivity response. In the upper left corner of the image shown here, one can see the metal plate of the watch band.

ACD is a T-cell mediated, delayed, type IV hypersensitivity response to foreign materials.1 These reactions typically occur around 48 to 72 hours following contact with the metal but can take weeks to appear, depending on the amount of T-cell activation. Symptoms may appear more rapidly on repeat exposures. Lesions manifest as erythematous, scaly plaques, which may include vesicles and bullae in severe cases.

The mainstay of treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is avoidance of the allergen once it has been identified. Nickel is commonly found in metal parts on clothing and in jewelry. One method of protection from nickel in these cases is to cover the metal that touches the skin with a clear nail polish or another clear barrier (commercial options are available). Duct tape or fabric can also be used to cover the metal.

Topical corticosteroids are the first-line therapy to treat lesions. Topical calcineurin inhibitors are an alternative. Systemic corticosteroids may be indicated if there is extensive body surface area involvement. Phototherapy or systemic immunosuppression may be considered in severe refractory cases.

Our patient was counseled on the nature of the disease process and educated on strategies to avoid future exposures. Treatment was initiated with topical triamcinolone 0.1% ointment with follow-up as needed.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Spenser Squire, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The gradual development of a rash in an area of frequent direct contact between metal and skin is pathognomonic for allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). Contact dermatitis often results from exposure to metals. Stainless steel is a group of ferrous alloys composed of a variety of elements including nickel, which is added to increase corrosion resistance. Unfortunately, nickel is a metal commonly known to induce a delayed hypersensitivity response. In the upper left corner of the image shown here, one can see the metal plate of the watch band.

ACD is a T-cell mediated, delayed, type IV hypersensitivity response to foreign materials.1 These reactions typically occur around 48 to 72 hours following contact with the metal but can take weeks to appear, depending on the amount of T-cell activation. Symptoms may appear more rapidly on repeat exposures. Lesions manifest as erythematous, scaly plaques, which may include vesicles and bullae in severe cases.

The mainstay of treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is avoidance of the allergen once it has been identified. Nickel is commonly found in metal parts on clothing and in jewelry. One method of protection from nickel in these cases is to cover the metal that touches the skin with a clear nail polish or another clear barrier (commercial options are available). Duct tape or fabric can also be used to cover the metal.

Topical corticosteroids are the first-line therapy to treat lesions. Topical calcineurin inhibitors are an alternative. Systemic corticosteroids may be indicated if there is extensive body surface area involvement. Phototherapy or systemic immunosuppression may be considered in severe refractory cases.

Our patient was counseled on the nature of the disease process and educated on strategies to avoid future exposures. Treatment was initiated with topical triamcinolone 0.1% ointment with follow-up as needed.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Spenser Squire, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1029-1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

1. Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1029-1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

A mass on the ear

Pathology indicated a proliferation of basaloid cells with matrical differentiation in transition and “shadow” cells, pointing to a diagnosis of pilomatricoma.

Pilomatricoma, also known as pilomatrixoma, is a benign skin tumor associated with hair follicles. The lesions are most often found on the neck or head area but can occur on the arms, legs, or torso. They are usually slow growing, solitary, and painless. The frequency of occurrence is rare, accounting for less than 1% of all benign skin tumors.1

A mutation in the Catenin beta-1 (CTNNB1) gene is the most common cause of isolated pilomatricoma and is a somatic defect, meaning it is acquired, not inherited. The mutation of the CTNNB1 gene causes disruption of normal function and maturation of the hair follicle. This leads to rapid cell growth and uncontrolled division, resulting in the formation of the pilomatricoma.1

A comprehensive review performed in 2018 noted that only 16% of pilomatricomas were accurately diagnosed on clinical exam.1 Clues that point to the diagnosis of pilomatricoma are the irregular, whitish yellow spots just under the skin. In contrast, epidermoid cysts usually have a central pore and a ballotable feel. The expression of calcification and gritty material from the lesion in this case ruled out a diagnosis of an epidermoid cyst. The most common method of treatment is surgical removal.1

This patient was counseled regarding her diagnosis and given the option of a plastic surgery referral to excise the affected tissue in its entirety. She opted to wait and see if the growth would scar down and not return.

Image courtesy of Edward A. Jackson, MD. Text courtesy of Edward A. Jackson, MD, FAAFP, Advent Health Medical Group Family Medicine at East Orlando, FL, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, et al. Pilomatrixoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:631-641. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000001118

Pathology indicated a proliferation of basaloid cells with matrical differentiation in transition and “shadow” cells, pointing to a diagnosis of pilomatricoma.

Pilomatricoma, also known as pilomatrixoma, is a benign skin tumor associated with hair follicles. The lesions are most often found on the neck or head area but can occur on the arms, legs, or torso. They are usually slow growing, solitary, and painless. The frequency of occurrence is rare, accounting for less than 1% of all benign skin tumors.1

A mutation in the Catenin beta-1 (CTNNB1) gene is the most common cause of isolated pilomatricoma and is a somatic defect, meaning it is acquired, not inherited. The mutation of the CTNNB1 gene causes disruption of normal function and maturation of the hair follicle. This leads to rapid cell growth and uncontrolled division, resulting in the formation of the pilomatricoma.1

A comprehensive review performed in 2018 noted that only 16% of pilomatricomas were accurately diagnosed on clinical exam.1 Clues that point to the diagnosis of pilomatricoma are the irregular, whitish yellow spots just under the skin. In contrast, epidermoid cysts usually have a central pore and a ballotable feel. The expression of calcification and gritty material from the lesion in this case ruled out a diagnosis of an epidermoid cyst. The most common method of treatment is surgical removal.1

This patient was counseled regarding her diagnosis and given the option of a plastic surgery referral to excise the affected tissue in its entirety. She opted to wait and see if the growth would scar down and not return.

Image courtesy of Edward A. Jackson, MD. Text courtesy of Edward A. Jackson, MD, FAAFP, Advent Health Medical Group Family Medicine at East Orlando, FL, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Pathology indicated a proliferation of basaloid cells with matrical differentiation in transition and “shadow” cells, pointing to a diagnosis of pilomatricoma.

Pilomatricoma, also known as pilomatrixoma, is a benign skin tumor associated with hair follicles. The lesions are most often found on the neck or head area but can occur on the arms, legs, or torso. They are usually slow growing, solitary, and painless. The frequency of occurrence is rare, accounting for less than 1% of all benign skin tumors.1

A mutation in the Catenin beta-1 (CTNNB1) gene is the most common cause of isolated pilomatricoma and is a somatic defect, meaning it is acquired, not inherited. The mutation of the CTNNB1 gene causes disruption of normal function and maturation of the hair follicle. This leads to rapid cell growth and uncontrolled division, resulting in the formation of the pilomatricoma.1

A comprehensive review performed in 2018 noted that only 16% of pilomatricomas were accurately diagnosed on clinical exam.1 Clues that point to the diagnosis of pilomatricoma are the irregular, whitish yellow spots just under the skin. In contrast, epidermoid cysts usually have a central pore and a ballotable feel. The expression of calcification and gritty material from the lesion in this case ruled out a diagnosis of an epidermoid cyst. The most common method of treatment is surgical removal.1

This patient was counseled regarding her diagnosis and given the option of a plastic surgery referral to excise the affected tissue in its entirety. She opted to wait and see if the growth would scar down and not return.

Image courtesy of Edward A. Jackson, MD. Text courtesy of Edward A. Jackson, MD, FAAFP, Advent Health Medical Group Family Medicine at East Orlando, FL, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, et al. Pilomatrixoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:631-641. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000001118

1. Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, et al. Pilomatrixoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:631-641. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000001118

A sun distributed rash

The photo distribution and annular quality of this patient’s rash, combined with his positive autoimmune work-up, led to a diagnosis of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), a nonscarring subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

SCLE is a chronic and relapsing condition that may manifest as either a papulosquamous or annular eruption.1 It most commonly affects areas of sun exposure such as the shoulders, upper back, and extensor surfaces of the arms. This disorder typically affects young or middle-aged women between the ages of 30 and 40 years.

The differential diagnosis of this eruption includes dermatomyositis, polymorphous light eruption, psoriasis, tinea corporis, and other photodermatoses. The etiology of SCLE is multifactorial and may include a genetic susceptibility in combination with environmental triggers that provoke an autoimmune response to sunlight.1 There is strong evidence linking drug-induced SCLE with proton pump inhibitors, anticonvulsants, beta-blockers, terbinafine, and immune modulators.2

As many as 70% of patients with SCLE have positive anti-Ro/SSA autoantibodies, and this is most often associated with Sjogren syndrome.1 Interestingly, SCLE patients often exhibit symptoms that overlap with Sjogren syndrome. Systemic involvement is rare in SCLE, and if present, these symptoms are usually limited to arthritis and myalgia.

Treatment of SCLE includes photo-protective behaviors, topical corticosteroids/calcineurin inhibitors, and systemic therapies such as hydroxychloroquine (first-line), methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil (second-line).2

Our patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg orally bid, with complete resolution of the lesions at his 2 month–follow-up appointment. This case emphasizes the importance of distinguishing SCLE from other subtypes of lupus erythematosus as the prognostic course and treatment varies between these conditions.

Photos courtesy of Kriti Mishra, MD. Text courtesy of Jaimie Lin, BS, Kriti Mishra, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2013.07.008

2. Jatwani S, Hearth Holmes MP. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. 2021. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

The photo distribution and annular quality of this patient’s rash, combined with his positive autoimmune work-up, led to a diagnosis of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), a nonscarring subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

SCLE is a chronic and relapsing condition that may manifest as either a papulosquamous or annular eruption.1 It most commonly affects areas of sun exposure such as the shoulders, upper back, and extensor surfaces of the arms. This disorder typically affects young or middle-aged women between the ages of 30 and 40 years.

The differential diagnosis of this eruption includes dermatomyositis, polymorphous light eruption, psoriasis, tinea corporis, and other photodermatoses. The etiology of SCLE is multifactorial and may include a genetic susceptibility in combination with environmental triggers that provoke an autoimmune response to sunlight.1 There is strong evidence linking drug-induced SCLE with proton pump inhibitors, anticonvulsants, beta-blockers, terbinafine, and immune modulators.2

As many as 70% of patients with SCLE have positive anti-Ro/SSA autoantibodies, and this is most often associated with Sjogren syndrome.1 Interestingly, SCLE patients often exhibit symptoms that overlap with Sjogren syndrome. Systemic involvement is rare in SCLE, and if present, these symptoms are usually limited to arthritis and myalgia.

Treatment of SCLE includes photo-protective behaviors, topical corticosteroids/calcineurin inhibitors, and systemic therapies such as hydroxychloroquine (first-line), methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil (second-line).2

Our patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg orally bid, with complete resolution of the lesions at his 2 month–follow-up appointment. This case emphasizes the importance of distinguishing SCLE from other subtypes of lupus erythematosus as the prognostic course and treatment varies between these conditions.

Photos courtesy of Kriti Mishra, MD. Text courtesy of Jaimie Lin, BS, Kriti Mishra, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The photo distribution and annular quality of this patient’s rash, combined with his positive autoimmune work-up, led to a diagnosis of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), a nonscarring subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

SCLE is a chronic and relapsing condition that may manifest as either a papulosquamous or annular eruption.1 It most commonly affects areas of sun exposure such as the shoulders, upper back, and extensor surfaces of the arms. This disorder typically affects young or middle-aged women between the ages of 30 and 40 years.

The differential diagnosis of this eruption includes dermatomyositis, polymorphous light eruption, psoriasis, tinea corporis, and other photodermatoses. The etiology of SCLE is multifactorial and may include a genetic susceptibility in combination with environmental triggers that provoke an autoimmune response to sunlight.1 There is strong evidence linking drug-induced SCLE with proton pump inhibitors, anticonvulsants, beta-blockers, terbinafine, and immune modulators.2

As many as 70% of patients with SCLE have positive anti-Ro/SSA autoantibodies, and this is most often associated with Sjogren syndrome.1 Interestingly, SCLE patients often exhibit symptoms that overlap with Sjogren syndrome. Systemic involvement is rare in SCLE, and if present, these symptoms are usually limited to arthritis and myalgia.

Treatment of SCLE includes photo-protective behaviors, topical corticosteroids/calcineurin inhibitors, and systemic therapies such as hydroxychloroquine (first-line), methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil (second-line).2

Our patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg orally bid, with complete resolution of the lesions at his 2 month–follow-up appointment. This case emphasizes the importance of distinguishing SCLE from other subtypes of lupus erythematosus as the prognostic course and treatment varies between these conditions.

Photos courtesy of Kriti Mishra, MD. Text courtesy of Jaimie Lin, BS, Kriti Mishra, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2013.07.008

2. Jatwani S, Hearth Holmes MP. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. 2021. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

1. Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2013.07.008

2. Jatwani S, Hearth Holmes MP. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. 2021. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

White ankle scars

A 42-year-old woman presented to our dermatology center with white scars on both of her ankles. She first noticed the lesions 2 years prior; they were initially erythematous and painful, even when she was at rest. Her past medical history included 3 spontaneous term miscarriages. She denied any prolonged standing or trauma.

On examination, atrophic porcelain-white stellate scars were visible with surrounding hyperpigmentation on the medial aspect of both ankles (FIGURE 1A & 1B). There were no tender erythematous nodules,

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Atrophie blanche

Atrophie blanche is a morphologic feature described as porcelain-white stellate scars with surrounding telangiectasia and hyperpigmentation. The lesions are typically found over the peri-malleolar region and are sequelae of healed erythematous and painful ulcers. The lesions arise from upper dermal, small vessel, thrombotic vasculopathy leading to ischemic rest pain; if left untreated, atrophic white scars eventually develop.

A sign of venous insufficiency or thrombotic vasculopathy

Atrophie blanche may develop following healing of an ulcer due to venous insufficiency or small vessel thrombotic vasculopathy.1 The incidence of thrombotic vasculopathy is 1:100,000 with a female predominance, and up to 50% of cases are associated with procoagulant conditions.2 Thrombotic vasculopathy can be due to an inherited or acquired thrombophilia.1

Causes of hereditary thrombophilia include Factor V Leiden/prothrombin mutations, anti-thrombin III/protein C/protein S deficiencies, dysfibrinogenemia, and hyperhomocysteinemia.

Acquired thrombophilia arises from underlying prothrombotic states associated with the Virchow triad: hypercoagulability, blood flow stasis, and endothelial injury. The use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy, presence of malignancy, and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) are causes of acquired thrombophilia.2

Obtaining a careful history is crucial

Thorough history-taking and physical examination are required to determine the underlying cause of atrophie blanche.

Continue to: Chronic venous insufficiency

Chronic venous insufficiency is more likely in patients with a history of prolonged standing, obesity, or previous injury/surgery to leg veins. Physical examination would reveal hyperpigmentation, telangiectasia, varicose veins, pedal edema, and venous ulcers.3

Inherited thrombophilia may be at work in patients with a family history of arterial and venous thrombosis (eg, stroke, acute coronary syndrome, or deep vein thromboses).

Acquired thrombophilia should be suspected if there is a history of recurrent miscarriages or malignancy.4 Given our patient’s history of miscarriages, we ordered further lab work and found that she had elevated anticardiolipin levels (> 40 U/mL) fulfilling the revised Sapporo criteria5 for APS.

Thrombophilia or chronic venous insufficiency? In a patient with a history suggestive of thrombophilia, further work-up should be done before attributing atrophie blanche to healed venous ulcers from chronic venous insufficiency. A skin lesion biopsy could reveal classic changes of thrombotic vasculopathy subjacent to the ulcer, including intraluminal thrombosis, endothelial proliferation, and subintimal hyaline degeneration, as opposed to dermal changes consistent with venous stasis, such as increased siderophages, hemosiderin deposition, erythrocyte extravasation, dermal fibrosis, and adipocytic damage.

Differential diagnosis includes atrophic scarring

The differential diagnosis for hypopigmented atrophic macules and plaques over the lower limbs include atrophic scarring from previous trauma, guttate morphea, extra-genital lichen sclerosus, and tuberculoid leprosy.

Continue to: Atrophic scarring

Atrophic scarring occurs only after trauma.

Guttate morphea lesions are sclerotic and may be depressed.

Extra-genital lichen sclerosus is characterized by polygonal, shiny, ivory-white sclerotic lesions with or without follicular plugging.

Tuberculoid leprosy involves loss of nociception, hypotrichosis, and palpable thickened regional nerves (eg, great auricular, sural, or ulnar nerve).

Treatment requires long-term anticoagulation

Our patient had APS and the mainstay of treatment is long-term systemic anticoagulation along with attentive wound care.6 Warfarin is preferred over a direct oral anticoagulant as it is more effective in the prevention of recurrent thrombosis in patients with APS.7

Our patient was started on warfarin. Since APS may occur as a primary condition or in the setting of a systemic disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, she was referred to a rheumatologist.

1. Alavi A, Hafner J, Dutz JP, et al. Atrophie blanche: is it associated with venous disease or livedoid vasculopathy? Adv Skin Wound Care. 2014;27:518-24. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000455098.98684.95

2. Di Giacomo TB, Hussein TP, Souza DG, et al. Frequency of thrombophilia determinant factors in patients with livedoid vasculopathy and treatment with anticoagulant drugs—a prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1340-1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03646.x

3. Millan SB, Gan R, Townsend PE. Venous ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:298-305.

4. Armstrong EM, Bellone JM, Hornsby LB, et al. Acquired thrombophilia. J Pharm Pract. 2014;27:234-242. doi: 10.1177/0897190014530424

5. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

6. Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:154-164. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1316-1

7. Cohen H, Hunt BJ, Efthymiou M, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin to treat patients with thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome, with or without systemic lupus erythematosus (RAPS): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 2/3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3:e426-e436. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30079-5

A 42-year-old woman presented to our dermatology center with white scars on both of her ankles. She first noticed the lesions 2 years prior; they were initially erythematous and painful, even when she was at rest. Her past medical history included 3 spontaneous term miscarriages. She denied any prolonged standing or trauma.

On examination, atrophic porcelain-white stellate scars were visible with surrounding hyperpigmentation on the medial aspect of both ankles (FIGURE 1A & 1B). There were no tender erythematous nodules,

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Atrophie blanche

Atrophie blanche is a morphologic feature described as porcelain-white stellate scars with surrounding telangiectasia and hyperpigmentation. The lesions are typically found over the peri-malleolar region and are sequelae of healed erythematous and painful ulcers. The lesions arise from upper dermal, small vessel, thrombotic vasculopathy leading to ischemic rest pain; if left untreated, atrophic white scars eventually develop.

A sign of venous insufficiency or thrombotic vasculopathy

Atrophie blanche may develop following healing of an ulcer due to venous insufficiency or small vessel thrombotic vasculopathy.1 The incidence of thrombotic vasculopathy is 1:100,000 with a female predominance, and up to 50% of cases are associated with procoagulant conditions.2 Thrombotic vasculopathy can be due to an inherited or acquired thrombophilia.1

Causes of hereditary thrombophilia include Factor V Leiden/prothrombin mutations, anti-thrombin III/protein C/protein S deficiencies, dysfibrinogenemia, and hyperhomocysteinemia.

Acquired thrombophilia arises from underlying prothrombotic states associated with the Virchow triad: hypercoagulability, blood flow stasis, and endothelial injury. The use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy, presence of malignancy, and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) are causes of acquired thrombophilia.2

Obtaining a careful history is crucial

Thorough history-taking and physical examination are required to determine the underlying cause of atrophie blanche.

Continue to: Chronic venous insufficiency

Chronic venous insufficiency is more likely in patients with a history of prolonged standing, obesity, or previous injury/surgery to leg veins. Physical examination would reveal hyperpigmentation, telangiectasia, varicose veins, pedal edema, and venous ulcers.3

Inherited thrombophilia may be at work in patients with a family history of arterial and venous thrombosis (eg, stroke, acute coronary syndrome, or deep vein thromboses).

Acquired thrombophilia should be suspected if there is a history of recurrent miscarriages or malignancy.4 Given our patient’s history of miscarriages, we ordered further lab work and found that she had elevated anticardiolipin levels (> 40 U/mL) fulfilling the revised Sapporo criteria5 for APS.

Thrombophilia or chronic venous insufficiency? In a patient with a history suggestive of thrombophilia, further work-up should be done before attributing atrophie blanche to healed venous ulcers from chronic venous insufficiency. A skin lesion biopsy could reveal classic changes of thrombotic vasculopathy subjacent to the ulcer, including intraluminal thrombosis, endothelial proliferation, and subintimal hyaline degeneration, as opposed to dermal changes consistent with venous stasis, such as increased siderophages, hemosiderin deposition, erythrocyte extravasation, dermal fibrosis, and adipocytic damage.

Differential diagnosis includes atrophic scarring

The differential diagnosis for hypopigmented atrophic macules and plaques over the lower limbs include atrophic scarring from previous trauma, guttate morphea, extra-genital lichen sclerosus, and tuberculoid leprosy.

Continue to: Atrophic scarring

Atrophic scarring occurs only after trauma.

Guttate morphea lesions are sclerotic and may be depressed.

Extra-genital lichen sclerosus is characterized by polygonal, shiny, ivory-white sclerotic lesions with or without follicular plugging.

Tuberculoid leprosy involves loss of nociception, hypotrichosis, and palpable thickened regional nerves (eg, great auricular, sural, or ulnar nerve).

Treatment requires long-term anticoagulation

Our patient had APS and the mainstay of treatment is long-term systemic anticoagulation along with attentive wound care.6 Warfarin is preferred over a direct oral anticoagulant as it is more effective in the prevention of recurrent thrombosis in patients with APS.7

Our patient was started on warfarin. Since APS may occur as a primary condition or in the setting of a systemic disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, she was referred to a rheumatologist.