User login

Pink nose lesion

The punch biopsy revealed dense lymphoid hyperplasia consistent with pseudolymphoma. The punch biopsy sample underwent notable immunohistochemical analysis to exclude lymphoma and was remarkable for a polyclonal set of B and T lymphocytes in a benign ratio, without epidermotropism.

Pseudolymphoma is an inflammatory response often induced by an arthropod bite, or occasionally, medication. Both T cell predominant and B cell predominant pseudolymphoma occur. Most present as a 5- to 30-mm pink papule on the head. They are rare below the waist and more common in young adults.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is such a common diagnosis for a novel pink neoplasm on the face of an older adult that it is easy to forget the many other rare tumors and benign lesions (such as this one) present this way. An expanded differential diagnosis included cutaneous lymphoma, amelanotic melanoma, and granulomatous rosacea.

In this case, dermoscopy of the lesion (shown above) also was of limited help because BCC features of arborized vessels and shiny white lines were evident. There was a lack of more specific dermoscopic features such as spoke wheel–like structures, leaflike structures, or blue clods. This lack of more specific features might be the subtle clue to think beyond BCC when approaching the diagnosis. The history of rapid change was somewhat atypical for a BCC, which tends to grow more slowly. Patient history about the timing of facial lesions can be poor, but this patient’s history fit the ultimate diagnosis well.

This patient was treated with a superpotent topical steroid, clobetasol ointment 0.05% bid for 3 weeks. As a general rule, use of such a strong steroid is avoided on the face because of the risk of steroid atrophy, but in the case of pseudolymphoma or lymphoma, an exception is allowed. An alternative would be intralesional triamcinolone at a 5 to 10 mg/mL concentration. At follow-up 6 weeks later, the lesion was completely resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Miguel D, Peckruhn M, Elsner P. Treatment of cutaneous pseudolymphoma: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:310-317.

The punch biopsy revealed dense lymphoid hyperplasia consistent with pseudolymphoma. The punch biopsy sample underwent notable immunohistochemical analysis to exclude lymphoma and was remarkable for a polyclonal set of B and T lymphocytes in a benign ratio, without epidermotropism.

Pseudolymphoma is an inflammatory response often induced by an arthropod bite, or occasionally, medication. Both T cell predominant and B cell predominant pseudolymphoma occur. Most present as a 5- to 30-mm pink papule on the head. They are rare below the waist and more common in young adults.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is such a common diagnosis for a novel pink neoplasm on the face of an older adult that it is easy to forget the many other rare tumors and benign lesions (such as this one) present this way. An expanded differential diagnosis included cutaneous lymphoma, amelanotic melanoma, and granulomatous rosacea.

In this case, dermoscopy of the lesion (shown above) also was of limited help because BCC features of arborized vessels and shiny white lines were evident. There was a lack of more specific dermoscopic features such as spoke wheel–like structures, leaflike structures, or blue clods. This lack of more specific features might be the subtle clue to think beyond BCC when approaching the diagnosis. The history of rapid change was somewhat atypical for a BCC, which tends to grow more slowly. Patient history about the timing of facial lesions can be poor, but this patient’s history fit the ultimate diagnosis well.

This patient was treated with a superpotent topical steroid, clobetasol ointment 0.05% bid for 3 weeks. As a general rule, use of such a strong steroid is avoided on the face because of the risk of steroid atrophy, but in the case of pseudolymphoma or lymphoma, an exception is allowed. An alternative would be intralesional triamcinolone at a 5 to 10 mg/mL concentration. At follow-up 6 weeks later, the lesion was completely resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

The punch biopsy revealed dense lymphoid hyperplasia consistent with pseudolymphoma. The punch biopsy sample underwent notable immunohistochemical analysis to exclude lymphoma and was remarkable for a polyclonal set of B and T lymphocytes in a benign ratio, without epidermotropism.

Pseudolymphoma is an inflammatory response often induced by an arthropod bite, or occasionally, medication. Both T cell predominant and B cell predominant pseudolymphoma occur. Most present as a 5- to 30-mm pink papule on the head. They are rare below the waist and more common in young adults.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is such a common diagnosis for a novel pink neoplasm on the face of an older adult that it is easy to forget the many other rare tumors and benign lesions (such as this one) present this way. An expanded differential diagnosis included cutaneous lymphoma, amelanotic melanoma, and granulomatous rosacea.

In this case, dermoscopy of the lesion (shown above) also was of limited help because BCC features of arborized vessels and shiny white lines were evident. There was a lack of more specific dermoscopic features such as spoke wheel–like structures, leaflike structures, or blue clods. This lack of more specific features might be the subtle clue to think beyond BCC when approaching the diagnosis. The history of rapid change was somewhat atypical for a BCC, which tends to grow more slowly. Patient history about the timing of facial lesions can be poor, but this patient’s history fit the ultimate diagnosis well.

This patient was treated with a superpotent topical steroid, clobetasol ointment 0.05% bid for 3 weeks. As a general rule, use of such a strong steroid is avoided on the face because of the risk of steroid atrophy, but in the case of pseudolymphoma or lymphoma, an exception is allowed. An alternative would be intralesional triamcinolone at a 5 to 10 mg/mL concentration. At follow-up 6 weeks later, the lesion was completely resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Miguel D, Peckruhn M, Elsner P. Treatment of cutaneous pseudolymphoma: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:310-317.

Miguel D, Peckruhn M, Elsner P. Treatment of cutaneous pseudolymphoma: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:310-317.

Itchy leg papules

Punch biopsy revealed collagen extravasation consistent with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis, an uncommon acquired disease that is seen in patients with longstanding renal disease or diabetes mellitus. The patient’s history of end-stage renal disease, paired with the eruptive nature of the pink papules with central firm plugs, pointed to the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for lesions like these includes prurigo nodularis and eruptive keratoacanthomas. Prurigo nodules would itch but likely lack a central plug. Eruptive keratoacanthomas would have a central keratinaceous plug but would be less likely to itch. A biopsy can help distinguish these entities.

Reactive perforating collagenosis can affect up to 10% of hemodialysis patients. It also can be associated with human immunodeficiency virus, hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, liver disease, and sclerosing cholangitis. One theory of the etiology is that underlying disease causes skin itching and the subsequent trauma from scratching causes reactivity.

The work-up consists of a punch biopsy of the entire lesion or central plug. A biopsy limited to the edge of the lesion, or one that is shallow, may fail to connect altered dermal collagen with its follicular elimination and be misread as dermatitis.

Lesions often resolve spontaneously, but disease can be widespread. Topical steroids and antihistamines may reduce itching. Narrowband UVB, topical or systemic retinoids, tetracyclines, and cryotherapy all have had reported success. Narrowband UVB is especially helpful for uremic pruritus and, if available, may be the treatment of choice.

This patient was treated with topical steroids, oral cetirizine 10 mg/d, and cryotherapy to the most stubborn lesions. Over 3 months, the number of lesions and severity of symptoms improved. She continued hemodialysis and awaits a renal transplant.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritis! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660.

Punch biopsy revealed collagen extravasation consistent with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis, an uncommon acquired disease that is seen in patients with longstanding renal disease or diabetes mellitus. The patient’s history of end-stage renal disease, paired with the eruptive nature of the pink papules with central firm plugs, pointed to the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for lesions like these includes prurigo nodularis and eruptive keratoacanthomas. Prurigo nodules would itch but likely lack a central plug. Eruptive keratoacanthomas would have a central keratinaceous plug but would be less likely to itch. A biopsy can help distinguish these entities.

Reactive perforating collagenosis can affect up to 10% of hemodialysis patients. It also can be associated with human immunodeficiency virus, hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, liver disease, and sclerosing cholangitis. One theory of the etiology is that underlying disease causes skin itching and the subsequent trauma from scratching causes reactivity.

The work-up consists of a punch biopsy of the entire lesion or central plug. A biopsy limited to the edge of the lesion, or one that is shallow, may fail to connect altered dermal collagen with its follicular elimination and be misread as dermatitis.

Lesions often resolve spontaneously, but disease can be widespread. Topical steroids and antihistamines may reduce itching. Narrowband UVB, topical or systemic retinoids, tetracyclines, and cryotherapy all have had reported success. Narrowband UVB is especially helpful for uremic pruritus and, if available, may be the treatment of choice.

This patient was treated with topical steroids, oral cetirizine 10 mg/d, and cryotherapy to the most stubborn lesions. Over 3 months, the number of lesions and severity of symptoms improved. She continued hemodialysis and awaits a renal transplant.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Punch biopsy revealed collagen extravasation consistent with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis, an uncommon acquired disease that is seen in patients with longstanding renal disease or diabetes mellitus. The patient’s history of end-stage renal disease, paired with the eruptive nature of the pink papules with central firm plugs, pointed to the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for lesions like these includes prurigo nodularis and eruptive keratoacanthomas. Prurigo nodules would itch but likely lack a central plug. Eruptive keratoacanthomas would have a central keratinaceous plug but would be less likely to itch. A biopsy can help distinguish these entities.

Reactive perforating collagenosis can affect up to 10% of hemodialysis patients. It also can be associated with human immunodeficiency virus, hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, liver disease, and sclerosing cholangitis. One theory of the etiology is that underlying disease causes skin itching and the subsequent trauma from scratching causes reactivity.

The work-up consists of a punch biopsy of the entire lesion or central plug. A biopsy limited to the edge of the lesion, or one that is shallow, may fail to connect altered dermal collagen with its follicular elimination and be misread as dermatitis.

Lesions often resolve spontaneously, but disease can be widespread. Topical steroids and antihistamines may reduce itching. Narrowband UVB, topical or systemic retinoids, tetracyclines, and cryotherapy all have had reported success. Narrowband UVB is especially helpful for uremic pruritus and, if available, may be the treatment of choice.

This patient was treated with topical steroids, oral cetirizine 10 mg/d, and cryotherapy to the most stubborn lesions. Over 3 months, the number of lesions and severity of symptoms improved. She continued hemodialysis and awaits a renal transplant.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritis! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660.

Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritis! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660.

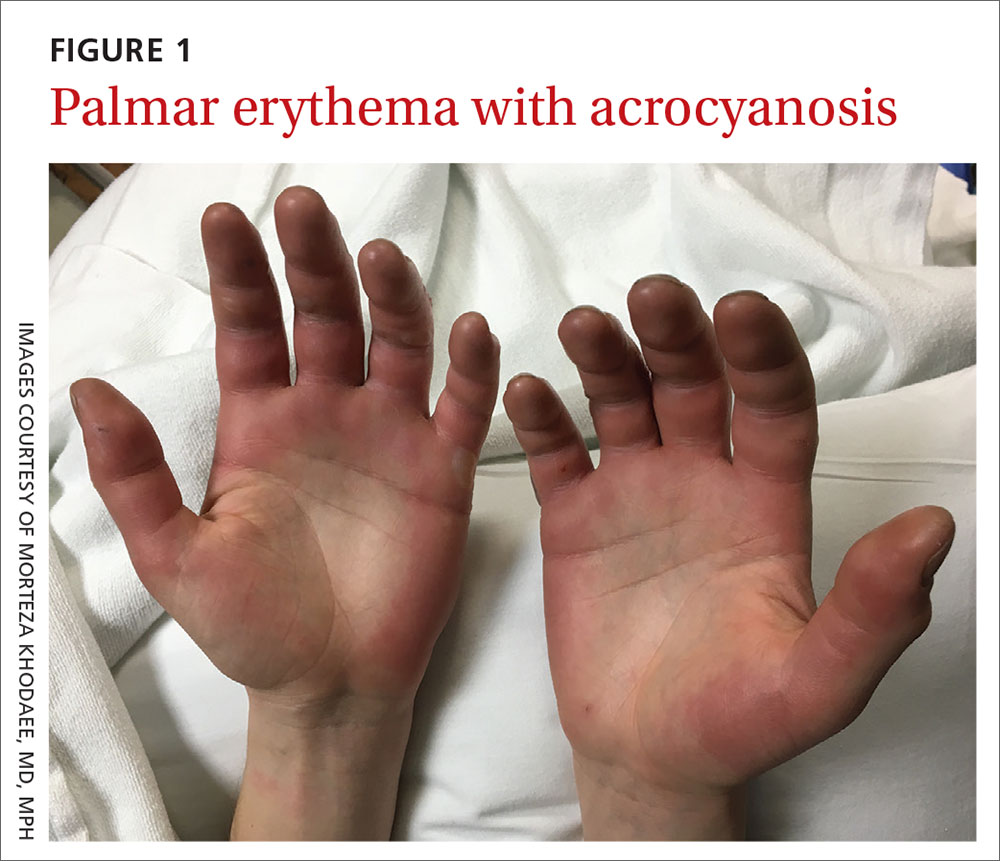

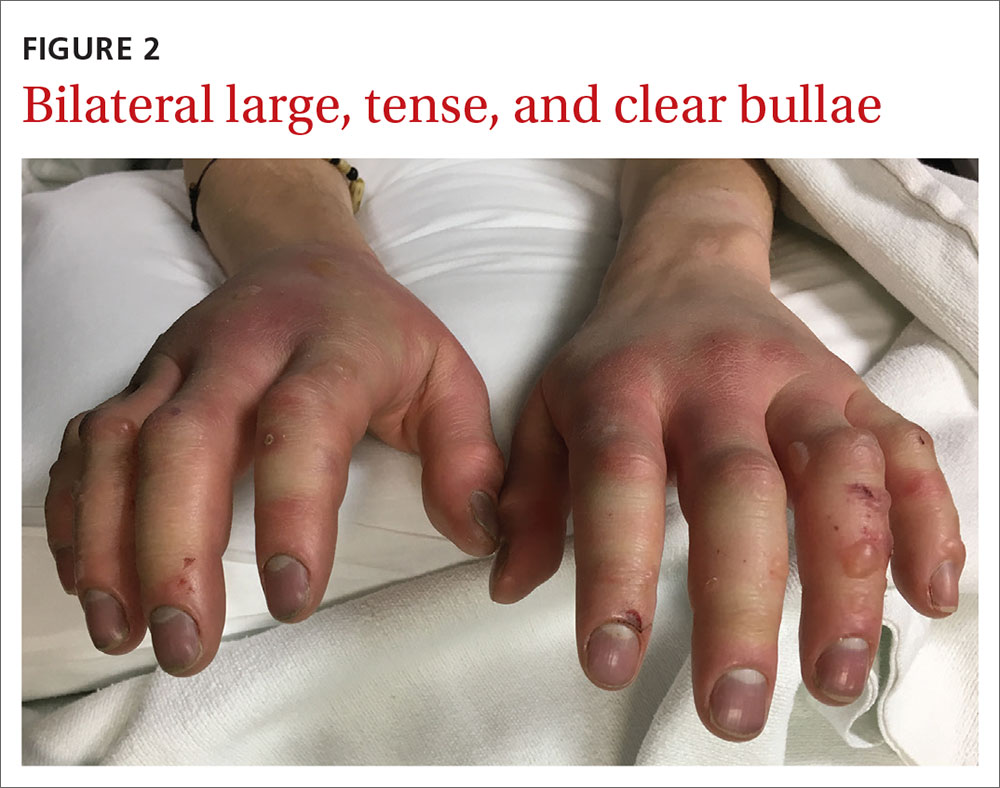

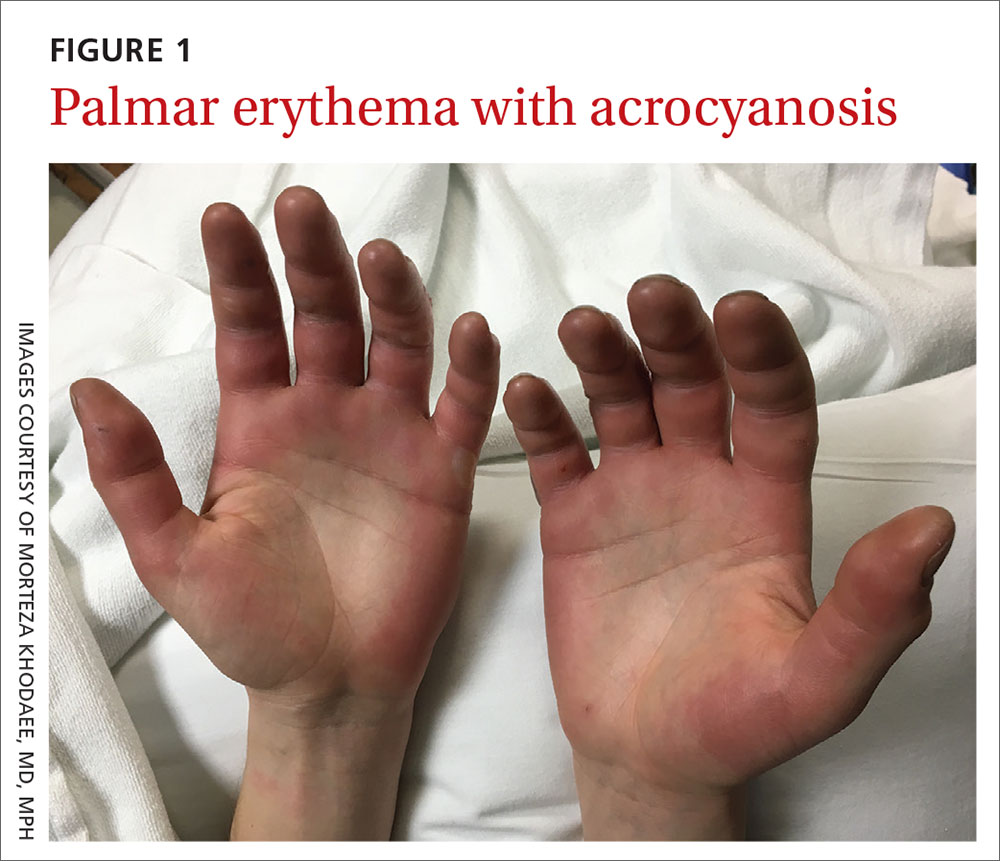

Acute bilateral hand edema and vesiculation

A 27-year-old man presented to the urgent care clinic with acute bilateral hand swelling, blisters, numbness, and pain. History taking revealed that these symptoms developed after he was locked outside of his apartment for 45 minutes in –22°C (–8°F) weather following a night of heavy drinking.

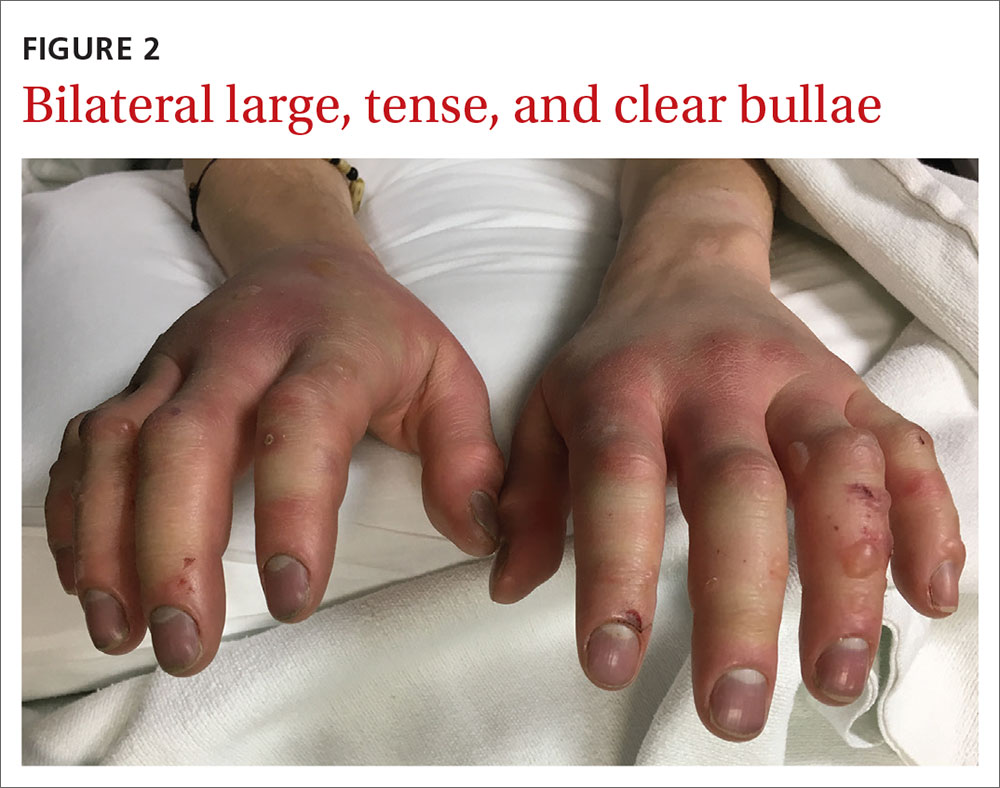

On physical examination, the patient had a temperature of 36.2°C (97.2°F) and a heart rate of 116 beats/min. He had

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Second-degree frostbite

Frostbite is the result of tissue freezing, which generally occurs after prolonged exposure to freezing temperatures (typically –4°C or below).1,2 The majority (~90%) of frostbite injuries occur in the hands and feet; however, frostbite has also been observed in the face, perineum, buttocks, and male genitalia.3

Frostbite is a clinical diagnosis based on a history of sustained exposure to freezing temperatures, paresthesia of affected areas, and typical skin changes. Evidence is lacking regarding the epidemiology of frostbite within the general population.2

Pathophysiology. Intra- and extracellular ice crystal formation causes fluid and electrolyte disturbances, cell dehydration, lipid denaturation, and subsequent cell death.1 After thawing, progressive tissue ischemia can occur as a result of endothelial damage and dysfunction, intravascular sludging, increased inflammatory markers, an influx of free radicals, and microvascular thrombosis.1

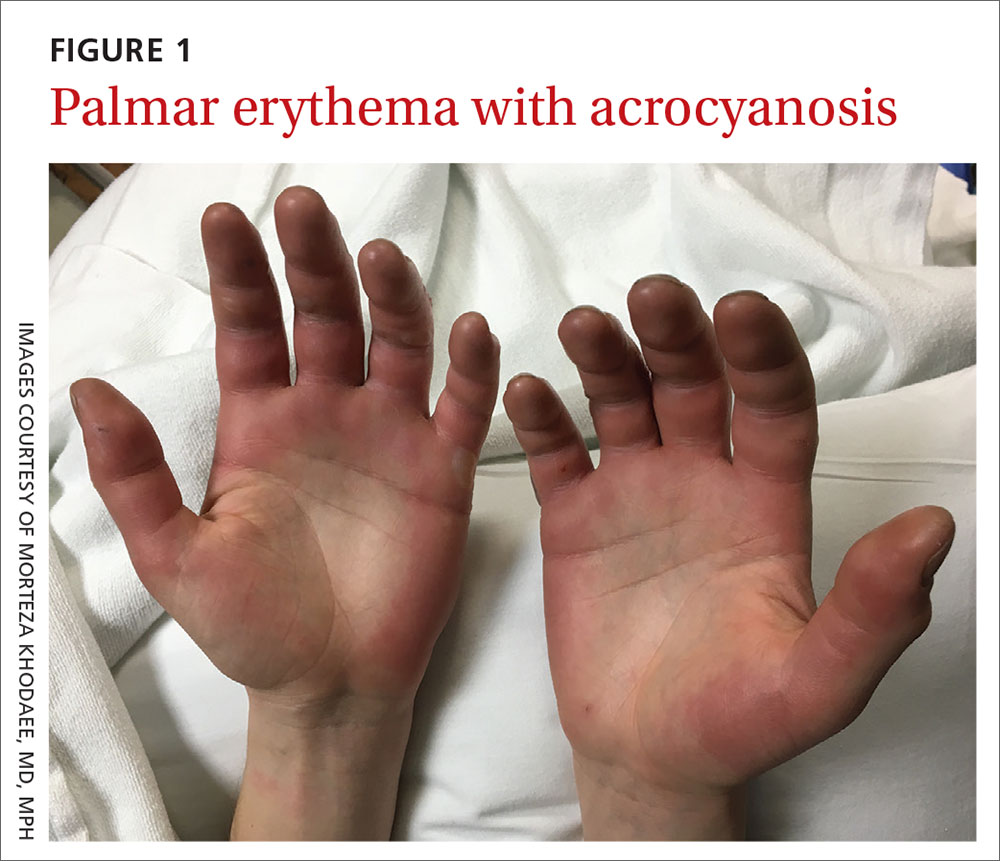

Classification. Traditionally, frostbite has been classified according to a 4-tiered system based on tissue appearance after rewarming.2 First-degree frostbite is characterized by white plaques with surrounding erythema; second degree by edema and clear or cloudy vesicles; third degree by hemorrhagic bullae; and fourth degree by cold and hard tissue that eventually progresses to gangrene.2

A simpler scheme designates frostbite as either superficial (corresponding to first- or second-degree frostbite) or deep (corresponding to third- or fourth-degree frostbite) with presumed muscle and bone involvement.2

Continue to: Risk factors

Risk factors. Frostbite is often associated with risk factors such as alcohol or drug intoxication, vehicular failure or trauma, immobilizing trauma, psychiatric illness, homelessness, Raynaud phenomenon, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, inadequate clothing, previous cold-weather injury, outdoor winter recreation, and the use of certain medications (eg, beta-blockers).1-3 Apart from environmental exposure, frostbite can also occur by direct contact with freezing materials, such as ice packs or industrial refrigerants.3

Differential includes nonfreezing injuries

Frostnip, pernio, and trench foot are other cold-weather injuries distinguished by the absence of tissue freezing.4 Raynaud phenomenon is a condition that is triggered by either cold temperatures or emotional stress.5

Frostnip is characterized by pallor and paresthesia of exposed areas. It may precede frostbite, but it quickly resolves after rewarming.2

Pernio occurs when skin is exposed to damp, cold, nonfreezing environments.6 It results in edematous and inflammatory skin lesions that may be painful, pruritic, violaceous, or erythematous.6 These lesions are typically found over the fingers, toes, nose, ears, buttocks, or thighs.4,6 Pernio may be classified as either primary or secondary disease.5 Primary pernio is considered idiopathic.6 Secondary pernio is thought to be either drug induced or due to underlying autoimmune diseases, such as hepatitis or cryopathy.6

Trench foot develops under similar conditions to pernio but requires exposure to a wet environment for at least 10 to 14 hours.7 It is characterized by foot pain, paresthesia, pruritus, edema, erythema, cyanosis, blisters, and even gangrene if left untreated.7

Continue to: Raynaud phenomenon

Raynaud phenomenon results from transient, acral vasocontraction and manifests as well-demarcated pallor, cyanosis, and then erythema as the affected body part reperfuses.5 Similar to pernio, it can be categorized as either primary or secondary.5 Primary phenomenon is idiopathic. Secondary phenomenon is thought to be a result of autoimmune disease, use of certain medications, occupational vibratory exposure, obstructive vascular disease, or infection

In the absence of a history of exposure to subfreezing temperatures, frostbite can be excluded from the differential diagnosis.

Treatment entails rewarming

The aim of frostbite treatment is to save injured cells and minimize tissue loss.1 This is accomplished through rapid rewarming and—in severe cases—reperfusion techniques.

Tissue should be rewarmed in a 37°C to 39°C water bath with povidone iodine or chlorhexidine added for antiseptic effect.1 All efforts should be made to avoid refreezing or trauma, as this could worsen the initial injury.2 Oral or intravenous hydration may be offered to optimize fluid status.1 Supplemental oxygen may be administered to maintain saturations above 90%.1 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are helpful for analgesia and anti-inflammatory effect, and opioids can be used for breakthrough pain.1 It is recommended that blisters be drained in a sterile fashion and that all affected tissue be covered with topical aloe vera and a loose dressing.1,2,4

Treatment of severe frostbite. Angiography should be performed on all patients with third- or fourth-degree frostbite.3 If imaging shows evidence of vascular occlusion, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and heparin can be initiated within 24 hours to reduce the risk for amputation.8-10

Continue to: Iloprost is another...

Iloprost is another proposed treatment for severe frostbite. It is a prostacyclin analog that may lower the amputation rate in patients with at least third-degree frostbite.11 Unlike tPA, iloprost may be given to trauma patients, and it can be used more than 24 hours after injury.2

In cases of fourth-degree frostbite that is not successfully reperfused, amputation is delayed until dry gangrene develops. This often takes weeks to months.12

Our patient underwent rewarming and was orally rehydrated. He was discharged home with ibuprofen, oxycodone-acetaminophen, topical aloe vera, and loose dressings. His bullae enlarged the next day (FIGURE 3). One week later, his blisters were debrided and dressed with silver sulfadiazine at his plastic surgery follow-up. He experienced sensory deficits for a few months, but eventually made a full recovery after 6 months with no remaining sequelae.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Lisa Kim, MD, for her clinical care of this patient.

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; morteza.khodaee@ cuanschutz.edu

1. Handford C, Thomas O, Imray CHE. Frostbite. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:281-299.

2. Heil K, Thomas R, Robertson G, et al. Freezing and non-freezing cold weather injuries: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2016;117:79-93.

3. Millet JD, Brown RK, Levi B, et al. Frostbite: spectrum of imaging findings and guidelines for management. Radiographics. 2016;36:2154-2169.

4. Long WB 3rd, Edlich RF, Winters KL, et al. Cold injuries. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2005;15:67-78.

5. Baker JS, Miranpuri S. Perniosis: a case report with literature review. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2016;106:138-140.

6. Bush JS, Watson S. Trench foot. Updated February 3, 2020. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482364/. Accessed April 22, 2020.

7. Musa R, Qurie A. Raynaud disease (Raynaud phenomenon, Raynaud syndrome). Updated February 14, 2019. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499833/. Accessed April 22, 2020.

8. Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, et al. Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg. 2007;142:546-551; discussion 551-553.

9. Gonzaga T, Jenabzadeh K, Anderson CP, et al. Use of intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy for acute treatment of frostbite in 62 patients with review of thrombolytic therapy in frostbite. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:e323-e334.

10. Twomey JA, Peltier GL, Zera RT. An open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator in treatment of severe frostbite. J Trauma. 2005;59:1350-1354; discussion 1354-1355.

11. Cauchy E, Cheguillaume B, Chetaille E. A controlled trial of a prostacyclin and rt-PA in the treatment of severe frostbite. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:189-190.

12. McIntosh SE, Opacic M, Freer L, et al; Wilderness Medical Society. Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of frostbite: 2014 update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2014;25(4 suppl):S43-S54.

A 27-year-old man presented to the urgent care clinic with acute bilateral hand swelling, blisters, numbness, and pain. History taking revealed that these symptoms developed after he was locked outside of his apartment for 45 minutes in –22°C (–8°F) weather following a night of heavy drinking.

On physical examination, the patient had a temperature of 36.2°C (97.2°F) and a heart rate of 116 beats/min. He had

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Second-degree frostbite

Frostbite is the result of tissue freezing, which generally occurs after prolonged exposure to freezing temperatures (typically –4°C or below).1,2 The majority (~90%) of frostbite injuries occur in the hands and feet; however, frostbite has also been observed in the face, perineum, buttocks, and male genitalia.3

Frostbite is a clinical diagnosis based on a history of sustained exposure to freezing temperatures, paresthesia of affected areas, and typical skin changes. Evidence is lacking regarding the epidemiology of frostbite within the general population.2

Pathophysiology. Intra- and extracellular ice crystal formation causes fluid and electrolyte disturbances, cell dehydration, lipid denaturation, and subsequent cell death.1 After thawing, progressive tissue ischemia can occur as a result of endothelial damage and dysfunction, intravascular sludging, increased inflammatory markers, an influx of free radicals, and microvascular thrombosis.1

Classification. Traditionally, frostbite has been classified according to a 4-tiered system based on tissue appearance after rewarming.2 First-degree frostbite is characterized by white plaques with surrounding erythema; second degree by edema and clear or cloudy vesicles; third degree by hemorrhagic bullae; and fourth degree by cold and hard tissue that eventually progresses to gangrene.2

A simpler scheme designates frostbite as either superficial (corresponding to first- or second-degree frostbite) or deep (corresponding to third- or fourth-degree frostbite) with presumed muscle and bone involvement.2

Continue to: Risk factors

Risk factors. Frostbite is often associated with risk factors such as alcohol or drug intoxication, vehicular failure or trauma, immobilizing trauma, psychiatric illness, homelessness, Raynaud phenomenon, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, inadequate clothing, previous cold-weather injury, outdoor winter recreation, and the use of certain medications (eg, beta-blockers).1-3 Apart from environmental exposure, frostbite can also occur by direct contact with freezing materials, such as ice packs or industrial refrigerants.3

Differential includes nonfreezing injuries

Frostnip, pernio, and trench foot are other cold-weather injuries distinguished by the absence of tissue freezing.4 Raynaud phenomenon is a condition that is triggered by either cold temperatures or emotional stress.5

Frostnip is characterized by pallor and paresthesia of exposed areas. It may precede frostbite, but it quickly resolves after rewarming.2

Pernio occurs when skin is exposed to damp, cold, nonfreezing environments.6 It results in edematous and inflammatory skin lesions that may be painful, pruritic, violaceous, or erythematous.6 These lesions are typically found over the fingers, toes, nose, ears, buttocks, or thighs.4,6 Pernio may be classified as either primary or secondary disease.5 Primary pernio is considered idiopathic.6 Secondary pernio is thought to be either drug induced or due to underlying autoimmune diseases, such as hepatitis or cryopathy.6

Trench foot develops under similar conditions to pernio but requires exposure to a wet environment for at least 10 to 14 hours.7 It is characterized by foot pain, paresthesia, pruritus, edema, erythema, cyanosis, blisters, and even gangrene if left untreated.7

Continue to: Raynaud phenomenon

Raynaud phenomenon results from transient, acral vasocontraction and manifests as well-demarcated pallor, cyanosis, and then erythema as the affected body part reperfuses.5 Similar to pernio, it can be categorized as either primary or secondary.5 Primary phenomenon is idiopathic. Secondary phenomenon is thought to be a result of autoimmune disease, use of certain medications, occupational vibratory exposure, obstructive vascular disease, or infection

In the absence of a history of exposure to subfreezing temperatures, frostbite can be excluded from the differential diagnosis.

Treatment entails rewarming

The aim of frostbite treatment is to save injured cells and minimize tissue loss.1 This is accomplished through rapid rewarming and—in severe cases—reperfusion techniques.

Tissue should be rewarmed in a 37°C to 39°C water bath with povidone iodine or chlorhexidine added for antiseptic effect.1 All efforts should be made to avoid refreezing or trauma, as this could worsen the initial injury.2 Oral or intravenous hydration may be offered to optimize fluid status.1 Supplemental oxygen may be administered to maintain saturations above 90%.1 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are helpful for analgesia and anti-inflammatory effect, and opioids can be used for breakthrough pain.1 It is recommended that blisters be drained in a sterile fashion and that all affected tissue be covered with topical aloe vera and a loose dressing.1,2,4

Treatment of severe frostbite. Angiography should be performed on all patients with third- or fourth-degree frostbite.3 If imaging shows evidence of vascular occlusion, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and heparin can be initiated within 24 hours to reduce the risk for amputation.8-10

Continue to: Iloprost is another...

Iloprost is another proposed treatment for severe frostbite. It is a prostacyclin analog that may lower the amputation rate in patients with at least third-degree frostbite.11 Unlike tPA, iloprost may be given to trauma patients, and it can be used more than 24 hours after injury.2

In cases of fourth-degree frostbite that is not successfully reperfused, amputation is delayed until dry gangrene develops. This often takes weeks to months.12

Our patient underwent rewarming and was orally rehydrated. He was discharged home with ibuprofen, oxycodone-acetaminophen, topical aloe vera, and loose dressings. His bullae enlarged the next day (FIGURE 3). One week later, his blisters were debrided and dressed with silver sulfadiazine at his plastic surgery follow-up. He experienced sensory deficits for a few months, but eventually made a full recovery after 6 months with no remaining sequelae.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Lisa Kim, MD, for her clinical care of this patient.

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; morteza.khodaee@ cuanschutz.edu

A 27-year-old man presented to the urgent care clinic with acute bilateral hand swelling, blisters, numbness, and pain. History taking revealed that these symptoms developed after he was locked outside of his apartment for 45 minutes in –22°C (–8°F) weather following a night of heavy drinking.

On physical examination, the patient had a temperature of 36.2°C (97.2°F) and a heart rate of 116 beats/min. He had

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Second-degree frostbite

Frostbite is the result of tissue freezing, which generally occurs after prolonged exposure to freezing temperatures (typically –4°C or below).1,2 The majority (~90%) of frostbite injuries occur in the hands and feet; however, frostbite has also been observed in the face, perineum, buttocks, and male genitalia.3

Frostbite is a clinical diagnosis based on a history of sustained exposure to freezing temperatures, paresthesia of affected areas, and typical skin changes. Evidence is lacking regarding the epidemiology of frostbite within the general population.2

Pathophysiology. Intra- and extracellular ice crystal formation causes fluid and electrolyte disturbances, cell dehydration, lipid denaturation, and subsequent cell death.1 After thawing, progressive tissue ischemia can occur as a result of endothelial damage and dysfunction, intravascular sludging, increased inflammatory markers, an influx of free radicals, and microvascular thrombosis.1

Classification. Traditionally, frostbite has been classified according to a 4-tiered system based on tissue appearance after rewarming.2 First-degree frostbite is characterized by white plaques with surrounding erythema; second degree by edema and clear or cloudy vesicles; third degree by hemorrhagic bullae; and fourth degree by cold and hard tissue that eventually progresses to gangrene.2

A simpler scheme designates frostbite as either superficial (corresponding to first- or second-degree frostbite) or deep (corresponding to third- or fourth-degree frostbite) with presumed muscle and bone involvement.2

Continue to: Risk factors

Risk factors. Frostbite is often associated with risk factors such as alcohol or drug intoxication, vehicular failure or trauma, immobilizing trauma, psychiatric illness, homelessness, Raynaud phenomenon, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, inadequate clothing, previous cold-weather injury, outdoor winter recreation, and the use of certain medications (eg, beta-blockers).1-3 Apart from environmental exposure, frostbite can also occur by direct contact with freezing materials, such as ice packs or industrial refrigerants.3

Differential includes nonfreezing injuries

Frostnip, pernio, and trench foot are other cold-weather injuries distinguished by the absence of tissue freezing.4 Raynaud phenomenon is a condition that is triggered by either cold temperatures or emotional stress.5

Frostnip is characterized by pallor and paresthesia of exposed areas. It may precede frostbite, but it quickly resolves after rewarming.2

Pernio occurs when skin is exposed to damp, cold, nonfreezing environments.6 It results in edematous and inflammatory skin lesions that may be painful, pruritic, violaceous, or erythematous.6 These lesions are typically found over the fingers, toes, nose, ears, buttocks, or thighs.4,6 Pernio may be classified as either primary or secondary disease.5 Primary pernio is considered idiopathic.6 Secondary pernio is thought to be either drug induced or due to underlying autoimmune diseases, such as hepatitis or cryopathy.6

Trench foot develops under similar conditions to pernio but requires exposure to a wet environment for at least 10 to 14 hours.7 It is characterized by foot pain, paresthesia, pruritus, edema, erythema, cyanosis, blisters, and even gangrene if left untreated.7

Continue to: Raynaud phenomenon

Raynaud phenomenon results from transient, acral vasocontraction and manifests as well-demarcated pallor, cyanosis, and then erythema as the affected body part reperfuses.5 Similar to pernio, it can be categorized as either primary or secondary.5 Primary phenomenon is idiopathic. Secondary phenomenon is thought to be a result of autoimmune disease, use of certain medications, occupational vibratory exposure, obstructive vascular disease, or infection

In the absence of a history of exposure to subfreezing temperatures, frostbite can be excluded from the differential diagnosis.

Treatment entails rewarming

The aim of frostbite treatment is to save injured cells and minimize tissue loss.1 This is accomplished through rapid rewarming and—in severe cases—reperfusion techniques.

Tissue should be rewarmed in a 37°C to 39°C water bath with povidone iodine or chlorhexidine added for antiseptic effect.1 All efforts should be made to avoid refreezing or trauma, as this could worsen the initial injury.2 Oral or intravenous hydration may be offered to optimize fluid status.1 Supplemental oxygen may be administered to maintain saturations above 90%.1 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are helpful for analgesia and anti-inflammatory effect, and opioids can be used for breakthrough pain.1 It is recommended that blisters be drained in a sterile fashion and that all affected tissue be covered with topical aloe vera and a loose dressing.1,2,4

Treatment of severe frostbite. Angiography should be performed on all patients with third- or fourth-degree frostbite.3 If imaging shows evidence of vascular occlusion, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and heparin can be initiated within 24 hours to reduce the risk for amputation.8-10

Continue to: Iloprost is another...

Iloprost is another proposed treatment for severe frostbite. It is a prostacyclin analog that may lower the amputation rate in patients with at least third-degree frostbite.11 Unlike tPA, iloprost may be given to trauma patients, and it can be used more than 24 hours after injury.2

In cases of fourth-degree frostbite that is not successfully reperfused, amputation is delayed until dry gangrene develops. This often takes weeks to months.12

Our patient underwent rewarming and was orally rehydrated. He was discharged home with ibuprofen, oxycodone-acetaminophen, topical aloe vera, and loose dressings. His bullae enlarged the next day (FIGURE 3). One week later, his blisters were debrided and dressed with silver sulfadiazine at his plastic surgery follow-up. He experienced sensory deficits for a few months, but eventually made a full recovery after 6 months with no remaining sequelae.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Lisa Kim, MD, for her clinical care of this patient.

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; morteza.khodaee@ cuanschutz.edu

1. Handford C, Thomas O, Imray CHE. Frostbite. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:281-299.

2. Heil K, Thomas R, Robertson G, et al. Freezing and non-freezing cold weather injuries: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2016;117:79-93.

3. Millet JD, Brown RK, Levi B, et al. Frostbite: spectrum of imaging findings and guidelines for management. Radiographics. 2016;36:2154-2169.

4. Long WB 3rd, Edlich RF, Winters KL, et al. Cold injuries. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2005;15:67-78.

5. Baker JS, Miranpuri S. Perniosis: a case report with literature review. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2016;106:138-140.

6. Bush JS, Watson S. Trench foot. Updated February 3, 2020. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482364/. Accessed April 22, 2020.

7. Musa R, Qurie A. Raynaud disease (Raynaud phenomenon, Raynaud syndrome). Updated February 14, 2019. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499833/. Accessed April 22, 2020.

8. Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, et al. Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg. 2007;142:546-551; discussion 551-553.

9. Gonzaga T, Jenabzadeh K, Anderson CP, et al. Use of intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy for acute treatment of frostbite in 62 patients with review of thrombolytic therapy in frostbite. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:e323-e334.

10. Twomey JA, Peltier GL, Zera RT. An open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator in treatment of severe frostbite. J Trauma. 2005;59:1350-1354; discussion 1354-1355.

11. Cauchy E, Cheguillaume B, Chetaille E. A controlled trial of a prostacyclin and rt-PA in the treatment of severe frostbite. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:189-190.

12. McIntosh SE, Opacic M, Freer L, et al; Wilderness Medical Society. Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of frostbite: 2014 update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2014;25(4 suppl):S43-S54.

1. Handford C, Thomas O, Imray CHE. Frostbite. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:281-299.

2. Heil K, Thomas R, Robertson G, et al. Freezing and non-freezing cold weather injuries: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2016;117:79-93.

3. Millet JD, Brown RK, Levi B, et al. Frostbite: spectrum of imaging findings and guidelines for management. Radiographics. 2016;36:2154-2169.

4. Long WB 3rd, Edlich RF, Winters KL, et al. Cold injuries. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2005;15:67-78.

5. Baker JS, Miranpuri S. Perniosis: a case report with literature review. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2016;106:138-140.

6. Bush JS, Watson S. Trench foot. Updated February 3, 2020. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482364/. Accessed April 22, 2020.

7. Musa R, Qurie A. Raynaud disease (Raynaud phenomenon, Raynaud syndrome). Updated February 14, 2019. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499833/. Accessed April 22, 2020.

8. Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, et al. Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg. 2007;142:546-551; discussion 551-553.

9. Gonzaga T, Jenabzadeh K, Anderson CP, et al. Use of intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy for acute treatment of frostbite in 62 patients with review of thrombolytic therapy in frostbite. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:e323-e334.

10. Twomey JA, Peltier GL, Zera RT. An open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator in treatment of severe frostbite. J Trauma. 2005;59:1350-1354; discussion 1354-1355.

11. Cauchy E, Cheguillaume B, Chetaille E. A controlled trial of a prostacyclin and rt-PA in the treatment of severe frostbite. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:189-190.

12. McIntosh SE, Opacic M, Freer L, et al; Wilderness Medical Society. Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of frostbite: 2014 update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2014;25(4 suppl):S43-S54.

Recent-onset bloody nodule

A 45-year-old man presented to the Dermatology Clinic with a 4-month history of a bump on his left upper back. The lesion was tender and had been draining clear fluid and intermittent blood; he denied any preceding trauma. He had been seen both by his primary care physician and by a physician at an urgent care clinic, where he was told to use an antibiotic ointment and benzoyl peroxide daily on the area and advised to seek a dermatology consult should it not resolve. He did not see any improvement from these measures.

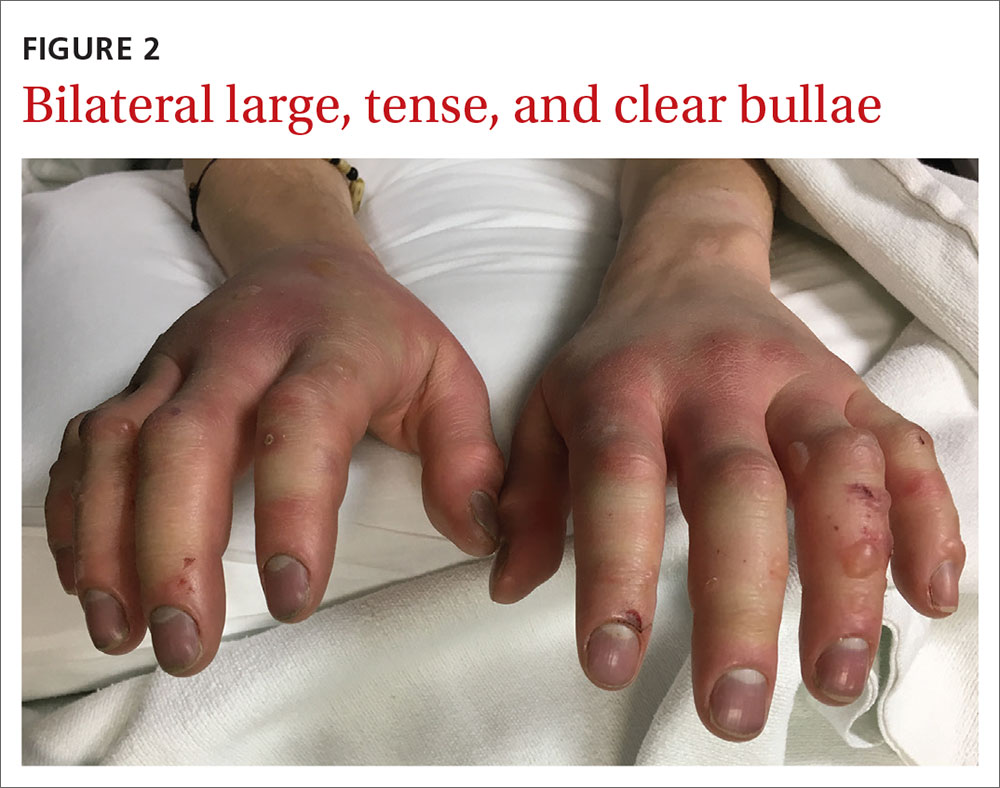

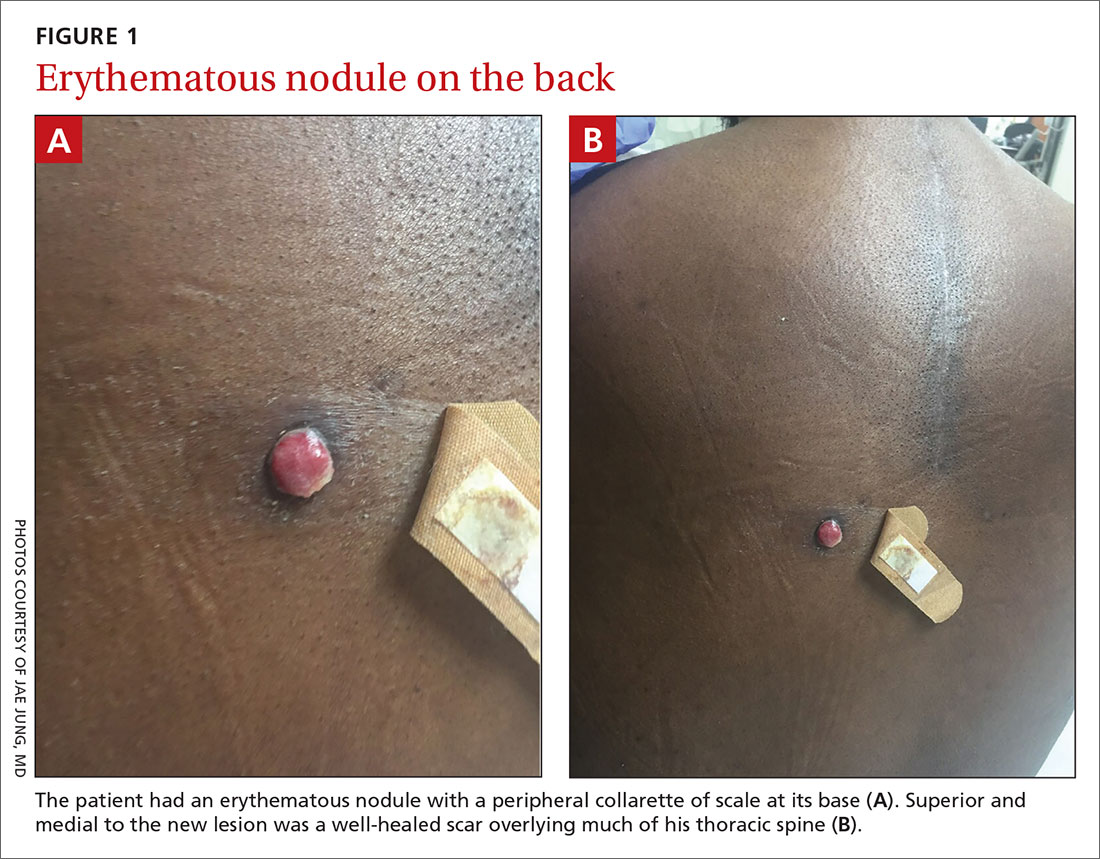

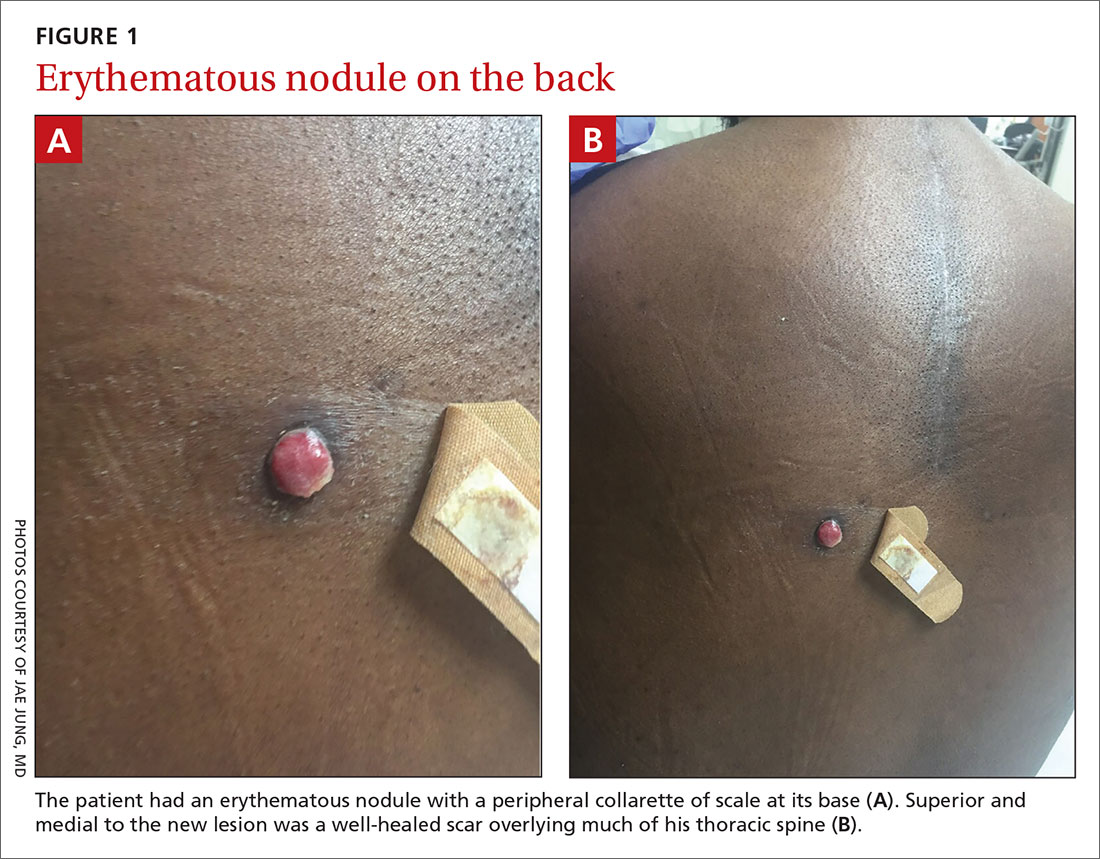

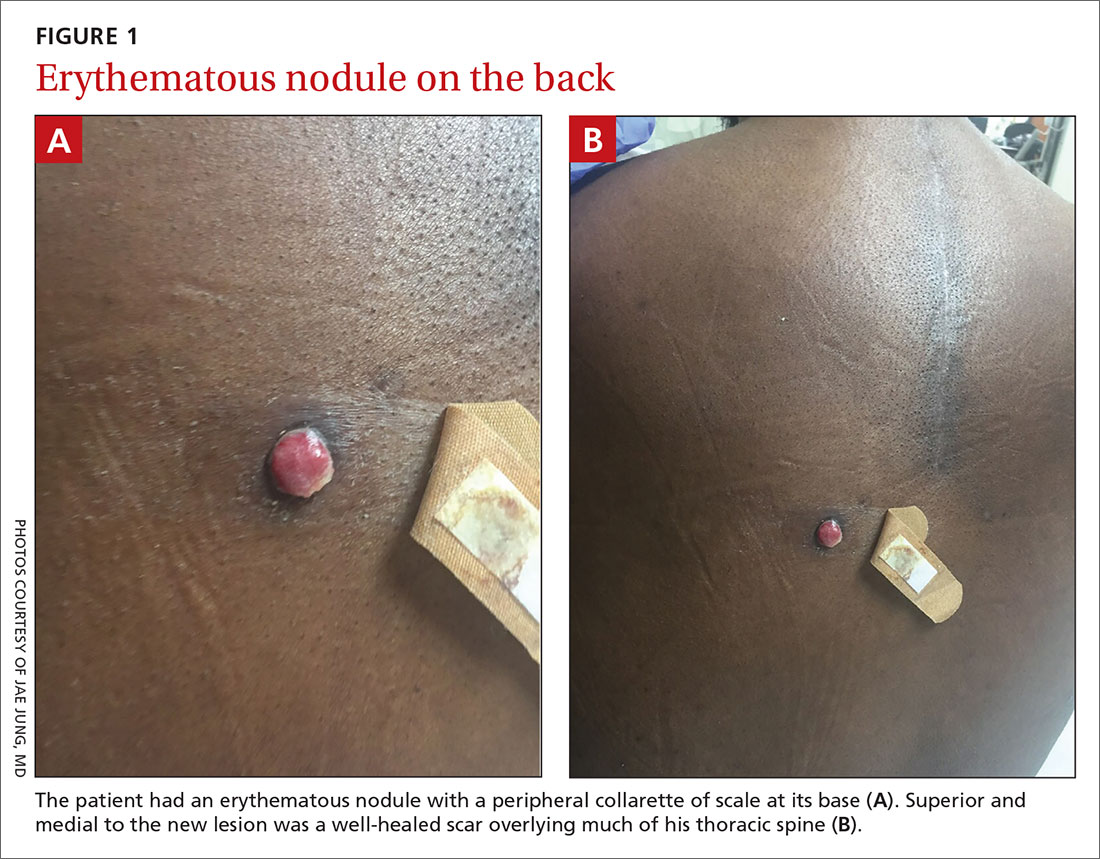

Physical exam revealed a 0.8-cm erythematous nodule with a peripheral collarette of scale at its base. The bandage used to cover the nodule was stained with hemorrhagic crust (FIGURE 1A). Superior and medial to the new lesion was a well-healed scar overlying much of the patient’s thoracic spine (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Metastatic renal cell carcinoma

The nodule initially appeared to be a benign pyogenic granuloma. In fact, a biopsy of the nodule showed a profile similar to that of a pyogenic granuloma and it exhibited granulation tissue. However, further questioning revealed that the patient had a history of metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma. (The scar was from a prior unrelated orthopedic surgery.) Immunohistochemical stains showed positive staining in the cells of interest for PAX8 and CK8, 2 markers for renal cell lineage.

Cutaneous metastasis to the skin is a rare event, representing roughly 2% of all skin tumors.1 Anatomically, lesions tend to appear on the head and neck in men and anterior chest and abdomen in women.2 Eruptions on the back, as seen in our patient, are relatively rare. The primary source of the metastasis also is gender dependent. Melanoma is the most common source overall; but in women, breast cancer represents the large majority of cutaneous metastases3 while in men lung, large intestine, and oral cavity tumors are the most common origin.3 Renal metastases are the fourth most common cause in men.3

The clinical morphology of cutaneous metastases is protean; the most common manifestations are nodules, papules, plaques, tumors, and ulcers.2 Rare manifestations include alopecia plaques, erysipelas, herpes zoster–like eruptions,4 and pyogenic granuloma–like manifestations, as in our case. Pyogenic granuloma–like manifestations have been described in renal cell carcinoma, breast carcinoma, acute myelogenous leukemia,5 and hepatocellular carcinoma.6

Differential includes an array of erythematous nodules

The differential diagnosis of a lesion with the appearance of a pyogenic granuloma is variable.

Pyogenic granulomas tend to arise over a short period of time. They are more common in children and pregnant women. Pyogenic granulomas can manifest anywhere but often are reported on the digits and extremities. Clinical history is important to ensure no history of internal malignancy.

Continue to: Bartonella henselae

Bartonella henselae, known as “cat scratch disease,” also can present as a friable, erythematous nodule reminiscent of a pyogenic granuloma. Patients with bartonella henselae usually are immunocompromised and/or have had close contact with a cat.7

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular tumor that may manifest as erythematous papules or nodules. Erythematous or violaceous patches or plaques may be present before a nodule arises. Kaposi sarcoma may manifest on the legs of elderly patients or anywhere on immunocompromised patients. Immunohistochemical stains for human herpesvirus-8 can clinch the diagnosis.8

Amelanotic melanoma may be impossible to discern clinically from a pyogenic granuloma. It appears as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored nodules. Histologic evaluation is paramount in the diagnosis.9

Clinical suspicion should prompt a biopsy

The diagnosis of metastatic renal cell carcinoma is made on clinical suspicion and skin biopsy. Dermoscopy is an important tool in the evaluation of primary cutaneous tumors. Due to the rarity of cutaneous metastases, studies on dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases are limited to case series. One series showed a vascular dermoscopy pattern in 15 of 17 cases (88%).10

In light of this nonspecific pattern, it’s wise to consider biopsy of a pyogenic granuloma–like lesion or one with a vascular pattern on dermoscopy in any patient with a history of malignancy. Any lesion suspected of being a pyogenic granuloma that does not respond to conservative measures also would warrant a biopsy. Definitive diagnosis is made based upon histologic evaluation.

Continue to: Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment

Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment

Upon diagnosis, immediate referral for further local and systemic control is recommended. Treatment may consist of any combination of surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or radiation.11

In this case, our patient was referred to Oncology for further treatment. Unfortunately, cutaneous metastases portend a very poor prognosis, with approximate survival times of 7.5 months.12

CORRESPONDENCE

M. Tye Haeberle, MD, 3810 Springhurst Boulevard, Ste 200, Louisville, KY 40241; [email protected]

1. Nashan D, Meiss F, Braun-Flaco M, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:567-580.

2. Alcaraz IM, Cerroni LM, Rütten AM, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

3. Lookingbill D, Spangler N, Helm K. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

4. Hussein MR. Skin metastases: a pathologist’s perspective. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:E1-E20.

5. Hager C, Cohen P. Cutaneous lesions of metastatic visceral malignancy mimicking pyogenic granuloma. Cancer Invest. 1999;17:385-390.

6. Kubota Y, Koga T, Nakayama J. Cutaneous metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma resembling pyogenic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:78-80.

7. Anderson BE, Neuman MA. Bartonella spp. as emerging human pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:203-219.

8. Patel RM, Goldblum JR, Hsi ED. Immunohistochemical detection of human herpes virus-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 is useful in the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:456-460.

9. Wee E, Wolfe R, Mclean C, et al. Clinically amelanotic or hypomelanotic melanoma: anatomic distribution, risk factors, and survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:645-651.

10. Chernoff K, Marghoob A, Lacouture M, et al. Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;4:429-433.

11. Adibi M, Thomas AZ, Borregales LD, et al. Surgical considerations for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:528-537.

12. Saeed S, Keehm C, Morgan M. Cutaneous metastases: a clinical, pathological and immunohistochemical appraisal. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;31:419-430.

A 45-year-old man presented to the Dermatology Clinic with a 4-month history of a bump on his left upper back. The lesion was tender and had been draining clear fluid and intermittent blood; he denied any preceding trauma. He had been seen both by his primary care physician and by a physician at an urgent care clinic, where he was told to use an antibiotic ointment and benzoyl peroxide daily on the area and advised to seek a dermatology consult should it not resolve. He did not see any improvement from these measures.

Physical exam revealed a 0.8-cm erythematous nodule with a peripheral collarette of scale at its base. The bandage used to cover the nodule was stained with hemorrhagic crust (FIGURE 1A). Superior and medial to the new lesion was a well-healed scar overlying much of the patient’s thoracic spine (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Metastatic renal cell carcinoma

The nodule initially appeared to be a benign pyogenic granuloma. In fact, a biopsy of the nodule showed a profile similar to that of a pyogenic granuloma and it exhibited granulation tissue. However, further questioning revealed that the patient had a history of metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma. (The scar was from a prior unrelated orthopedic surgery.) Immunohistochemical stains showed positive staining in the cells of interest for PAX8 and CK8, 2 markers for renal cell lineage.

Cutaneous metastasis to the skin is a rare event, representing roughly 2% of all skin tumors.1 Anatomically, lesions tend to appear on the head and neck in men and anterior chest and abdomen in women.2 Eruptions on the back, as seen in our patient, are relatively rare. The primary source of the metastasis also is gender dependent. Melanoma is the most common source overall; but in women, breast cancer represents the large majority of cutaneous metastases3 while in men lung, large intestine, and oral cavity tumors are the most common origin.3 Renal metastases are the fourth most common cause in men.3

The clinical morphology of cutaneous metastases is protean; the most common manifestations are nodules, papules, plaques, tumors, and ulcers.2 Rare manifestations include alopecia plaques, erysipelas, herpes zoster–like eruptions,4 and pyogenic granuloma–like manifestations, as in our case. Pyogenic granuloma–like manifestations have been described in renal cell carcinoma, breast carcinoma, acute myelogenous leukemia,5 and hepatocellular carcinoma.6

Differential includes an array of erythematous nodules

The differential diagnosis of a lesion with the appearance of a pyogenic granuloma is variable.

Pyogenic granulomas tend to arise over a short period of time. They are more common in children and pregnant women. Pyogenic granulomas can manifest anywhere but often are reported on the digits and extremities. Clinical history is important to ensure no history of internal malignancy.

Continue to: Bartonella henselae

Bartonella henselae, known as “cat scratch disease,” also can present as a friable, erythematous nodule reminiscent of a pyogenic granuloma. Patients with bartonella henselae usually are immunocompromised and/or have had close contact with a cat.7

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular tumor that may manifest as erythematous papules or nodules. Erythematous or violaceous patches or plaques may be present before a nodule arises. Kaposi sarcoma may manifest on the legs of elderly patients or anywhere on immunocompromised patients. Immunohistochemical stains for human herpesvirus-8 can clinch the diagnosis.8

Amelanotic melanoma may be impossible to discern clinically from a pyogenic granuloma. It appears as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored nodules. Histologic evaluation is paramount in the diagnosis.9

Clinical suspicion should prompt a biopsy

The diagnosis of metastatic renal cell carcinoma is made on clinical suspicion and skin biopsy. Dermoscopy is an important tool in the evaluation of primary cutaneous tumors. Due to the rarity of cutaneous metastases, studies on dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases are limited to case series. One series showed a vascular dermoscopy pattern in 15 of 17 cases (88%).10

In light of this nonspecific pattern, it’s wise to consider biopsy of a pyogenic granuloma–like lesion or one with a vascular pattern on dermoscopy in any patient with a history of malignancy. Any lesion suspected of being a pyogenic granuloma that does not respond to conservative measures also would warrant a biopsy. Definitive diagnosis is made based upon histologic evaluation.

Continue to: Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment

Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment

Upon diagnosis, immediate referral for further local and systemic control is recommended. Treatment may consist of any combination of surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or radiation.11

In this case, our patient was referred to Oncology for further treatment. Unfortunately, cutaneous metastases portend a very poor prognosis, with approximate survival times of 7.5 months.12

CORRESPONDENCE

M. Tye Haeberle, MD, 3810 Springhurst Boulevard, Ste 200, Louisville, KY 40241; [email protected]

A 45-year-old man presented to the Dermatology Clinic with a 4-month history of a bump on his left upper back. The lesion was tender and had been draining clear fluid and intermittent blood; he denied any preceding trauma. He had been seen both by his primary care physician and by a physician at an urgent care clinic, where he was told to use an antibiotic ointment and benzoyl peroxide daily on the area and advised to seek a dermatology consult should it not resolve. He did not see any improvement from these measures.

Physical exam revealed a 0.8-cm erythematous nodule with a peripheral collarette of scale at its base. The bandage used to cover the nodule was stained with hemorrhagic crust (FIGURE 1A). Superior and medial to the new lesion was a well-healed scar overlying much of the patient’s thoracic spine (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Metastatic renal cell carcinoma

The nodule initially appeared to be a benign pyogenic granuloma. In fact, a biopsy of the nodule showed a profile similar to that of a pyogenic granuloma and it exhibited granulation tissue. However, further questioning revealed that the patient had a history of metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma. (The scar was from a prior unrelated orthopedic surgery.) Immunohistochemical stains showed positive staining in the cells of interest for PAX8 and CK8, 2 markers for renal cell lineage.

Cutaneous metastasis to the skin is a rare event, representing roughly 2% of all skin tumors.1 Anatomically, lesions tend to appear on the head and neck in men and anterior chest and abdomen in women.2 Eruptions on the back, as seen in our patient, are relatively rare. The primary source of the metastasis also is gender dependent. Melanoma is the most common source overall; but in women, breast cancer represents the large majority of cutaneous metastases3 while in men lung, large intestine, and oral cavity tumors are the most common origin.3 Renal metastases are the fourth most common cause in men.3

The clinical morphology of cutaneous metastases is protean; the most common manifestations are nodules, papules, plaques, tumors, and ulcers.2 Rare manifestations include alopecia plaques, erysipelas, herpes zoster–like eruptions,4 and pyogenic granuloma–like manifestations, as in our case. Pyogenic granuloma–like manifestations have been described in renal cell carcinoma, breast carcinoma, acute myelogenous leukemia,5 and hepatocellular carcinoma.6

Differential includes an array of erythematous nodules

The differential diagnosis of a lesion with the appearance of a pyogenic granuloma is variable.

Pyogenic granulomas tend to arise over a short period of time. They are more common in children and pregnant women. Pyogenic granulomas can manifest anywhere but often are reported on the digits and extremities. Clinical history is important to ensure no history of internal malignancy.

Continue to: Bartonella henselae

Bartonella henselae, known as “cat scratch disease,” also can present as a friable, erythematous nodule reminiscent of a pyogenic granuloma. Patients with bartonella henselae usually are immunocompromised and/or have had close contact with a cat.7

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular tumor that may manifest as erythematous papules or nodules. Erythematous or violaceous patches or plaques may be present before a nodule arises. Kaposi sarcoma may manifest on the legs of elderly patients or anywhere on immunocompromised patients. Immunohistochemical stains for human herpesvirus-8 can clinch the diagnosis.8

Amelanotic melanoma may be impossible to discern clinically from a pyogenic granuloma. It appears as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored nodules. Histologic evaluation is paramount in the diagnosis.9

Clinical suspicion should prompt a biopsy

The diagnosis of metastatic renal cell carcinoma is made on clinical suspicion and skin biopsy. Dermoscopy is an important tool in the evaluation of primary cutaneous tumors. Due to the rarity of cutaneous metastases, studies on dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases are limited to case series. One series showed a vascular dermoscopy pattern in 15 of 17 cases (88%).10

In light of this nonspecific pattern, it’s wise to consider biopsy of a pyogenic granuloma–like lesion or one with a vascular pattern on dermoscopy in any patient with a history of malignancy. Any lesion suspected of being a pyogenic granuloma that does not respond to conservative measures also would warrant a biopsy. Definitive diagnosis is made based upon histologic evaluation.

Continue to: Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment

Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment

Upon diagnosis, immediate referral for further local and systemic control is recommended. Treatment may consist of any combination of surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or radiation.11

In this case, our patient was referred to Oncology for further treatment. Unfortunately, cutaneous metastases portend a very poor prognosis, with approximate survival times of 7.5 months.12

CORRESPONDENCE

M. Tye Haeberle, MD, 3810 Springhurst Boulevard, Ste 200, Louisville, KY 40241; [email protected]

1. Nashan D, Meiss F, Braun-Flaco M, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:567-580.

2. Alcaraz IM, Cerroni LM, Rütten AM, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

3. Lookingbill D, Spangler N, Helm K. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

4. Hussein MR. Skin metastases: a pathologist’s perspective. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:E1-E20.

5. Hager C, Cohen P. Cutaneous lesions of metastatic visceral malignancy mimicking pyogenic granuloma. Cancer Invest. 1999;17:385-390.

6. Kubota Y, Koga T, Nakayama J. Cutaneous metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma resembling pyogenic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:78-80.

7. Anderson BE, Neuman MA. Bartonella spp. as emerging human pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:203-219.

8. Patel RM, Goldblum JR, Hsi ED. Immunohistochemical detection of human herpes virus-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 is useful in the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:456-460.

9. Wee E, Wolfe R, Mclean C, et al. Clinically amelanotic or hypomelanotic melanoma: anatomic distribution, risk factors, and survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:645-651.

10. Chernoff K, Marghoob A, Lacouture M, et al. Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;4:429-433.

11. Adibi M, Thomas AZ, Borregales LD, et al. Surgical considerations for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:528-537.

12. Saeed S, Keehm C, Morgan M. Cutaneous metastases: a clinical, pathological and immunohistochemical appraisal. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;31:419-430.

1. Nashan D, Meiss F, Braun-Flaco M, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:567-580.

2. Alcaraz IM, Cerroni LM, Rütten AM, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

3. Lookingbill D, Spangler N, Helm K. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

4. Hussein MR. Skin metastases: a pathologist’s perspective. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:E1-E20.

5. Hager C, Cohen P. Cutaneous lesions of metastatic visceral malignancy mimicking pyogenic granuloma. Cancer Invest. 1999;17:385-390.

6. Kubota Y, Koga T, Nakayama J. Cutaneous metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma resembling pyogenic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:78-80.

7. Anderson BE, Neuman MA. Bartonella spp. as emerging human pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:203-219.

8. Patel RM, Goldblum JR, Hsi ED. Immunohistochemical detection of human herpes virus-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 is useful in the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:456-460.

9. Wee E, Wolfe R, Mclean C, et al. Clinically amelanotic or hypomelanotic melanoma: anatomic distribution, risk factors, and survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:645-651.

10. Chernoff K, Marghoob A, Lacouture M, et al. Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;4:429-433.

11. Adibi M, Thomas AZ, Borregales LD, et al. Surgical considerations for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:528-537.

12. Saeed S, Keehm C, Morgan M. Cutaneous metastases: a clinical, pathological and immunohistochemical appraisal. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;31:419-430.

Ear and nose plaques

Based on the clinical appearance of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented scaly plaques in sun-exposed facial areas (with associated scarring and follicular plugging in affected lesions), the patient was given a diagnosis of discoid lupus erythematosus. The diagnosis was confirmed with a punch biopsy that showed characteristic interface dermatitis with superficial and deep perivascular and peri-adnexal lymphocytes. Direct immunofluorescence showed a band of C3 at the dermo-epidermal junction, consistent with various forms of cutaneous lupus.

A review of systems was negative for signs of systemic disease, including a lack of weakness, joint pain/swelling, fever, or known blood clots. An antinuclear antibody panel was also negative, largely excluding systemic disease.

Discoid lupus erythematosus is a form of cutaneous lupus. Patients often are genetically predisposed to autoimmune disease, and disease may be triggered by sun exposure. Up to 80% of patients develop lesions that are limited to the head and neck. Up to 25% of patients develop systemic lupus erythematosus that may occur months—or even decades—after the initial diagnosis. Lesions may lead to longstanding scars; this cannot always be prevented.

Two- to 3-week trials of topical potent or superpotent steroids applied to affected plaques may lead to clearance. Additionally, lesions may be treated with intralesional triamcinolone 3 mg/mL to 10 mg/mL and repeated every 3 to 4 weeks. Systemic therapies include hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, retinoids, steroid sparing immunomodulators, and rarely prednisone.

This patient tolerated topical therapy well and though some scars remained, he was able to control flares with 2- to 3-week courses of clobetasol 0.05% twice daily. He is followed 2 to 3 times annually and has not developed signs or serologic findings of systemic disease over several years.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Jessop S, Whitelaw DA, Grainge MJ, et al. Drugs for discoid lupus erythematosus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD002954.

Based on the clinical appearance of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented scaly plaques in sun-exposed facial areas (with associated scarring and follicular plugging in affected lesions), the patient was given a diagnosis of discoid lupus erythematosus. The diagnosis was confirmed with a punch biopsy that showed characteristic interface dermatitis with superficial and deep perivascular and peri-adnexal lymphocytes. Direct immunofluorescence showed a band of C3 at the dermo-epidermal junction, consistent with various forms of cutaneous lupus.

A review of systems was negative for signs of systemic disease, including a lack of weakness, joint pain/swelling, fever, or known blood clots. An antinuclear antibody panel was also negative, largely excluding systemic disease.

Discoid lupus erythematosus is a form of cutaneous lupus. Patients often are genetically predisposed to autoimmune disease, and disease may be triggered by sun exposure. Up to 80% of patients develop lesions that are limited to the head and neck. Up to 25% of patients develop systemic lupus erythematosus that may occur months—or even decades—after the initial diagnosis. Lesions may lead to longstanding scars; this cannot always be prevented.

Two- to 3-week trials of topical potent or superpotent steroids applied to affected plaques may lead to clearance. Additionally, lesions may be treated with intralesional triamcinolone 3 mg/mL to 10 mg/mL and repeated every 3 to 4 weeks. Systemic therapies include hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, retinoids, steroid sparing immunomodulators, and rarely prednisone.

This patient tolerated topical therapy well and though some scars remained, he was able to control flares with 2- to 3-week courses of clobetasol 0.05% twice daily. He is followed 2 to 3 times annually and has not developed signs or serologic findings of systemic disease over several years.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Based on the clinical appearance of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented scaly plaques in sun-exposed facial areas (with associated scarring and follicular plugging in affected lesions), the patient was given a diagnosis of discoid lupus erythematosus. The diagnosis was confirmed with a punch biopsy that showed characteristic interface dermatitis with superficial and deep perivascular and peri-adnexal lymphocytes. Direct immunofluorescence showed a band of C3 at the dermo-epidermal junction, consistent with various forms of cutaneous lupus.

A review of systems was negative for signs of systemic disease, including a lack of weakness, joint pain/swelling, fever, or known blood clots. An antinuclear antibody panel was also negative, largely excluding systemic disease.

Discoid lupus erythematosus is a form of cutaneous lupus. Patients often are genetically predisposed to autoimmune disease, and disease may be triggered by sun exposure. Up to 80% of patients develop lesions that are limited to the head and neck. Up to 25% of patients develop systemic lupus erythematosus that may occur months—or even decades—after the initial diagnosis. Lesions may lead to longstanding scars; this cannot always be prevented.

Two- to 3-week trials of topical potent or superpotent steroids applied to affected plaques may lead to clearance. Additionally, lesions may be treated with intralesional triamcinolone 3 mg/mL to 10 mg/mL and repeated every 3 to 4 weeks. Systemic therapies include hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, retinoids, steroid sparing immunomodulators, and rarely prednisone.

This patient tolerated topical therapy well and though some scars remained, he was able to control flares with 2- to 3-week courses of clobetasol 0.05% twice daily. He is followed 2 to 3 times annually and has not developed signs or serologic findings of systemic disease over several years.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Jessop S, Whitelaw DA, Grainge MJ, et al. Drugs for discoid lupus erythematosus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD002954.

Jessop S, Whitelaw DA, Grainge MJ, et al. Drugs for discoid lupus erythematosus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD002954.

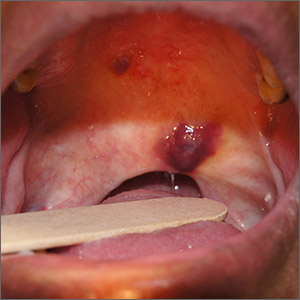

Purple oral plaques

The papules were clinically consistent with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and confirmed with a biopsy from the buccal mucosa. The patient had not been given a diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prior to this presentation. However, the physician confirmed the diagnosis with RNA titers. A CD4 count < 40 cells/mm3 (reference range, 500-1200 cells/mm3) pointed to her progression to AIDS. A chest X-ray revealed multiple nodules; a subsequent biopsy indicated that they were consistent with KS.

KS is a low-grade tumor of vascular origin associated with human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8). It most often presents on the skin as flat to raised pink to deep purple lesions. It can manifest in the oral mucosa, viscera, and other organs, which can portend a worse prognosis because of the risks associated with bleeding and organ perforation.

There are 4 types of KS.

- Classic KS occurs most often in elderly men of Mediterranean descent.

- HIV-associated KS can occur at any time during HIV infection but is more common as CD4 counts fall. HIV-associated KS increased in frequency dramatically in the United States during the early years of the HIV pandemic prior to effective antiretroviral therapy (ART).

- Endemic KS occurs in equatorial Africa, where there is a natural increased transmission rate of HHV-8.

- Iatrogenic KS can occur following treatment with immunosuppressive therapies.

Our patient was admitted to the Infectious Disease Service and given ART. Chemotherapy was discussed (and sometimes is warranted in extensive visceral disease) but the patient and her specialists opted for ART alone. In addition to ART, she was started on daily trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for pneumocystis prophylaxis.

At 6 months’ follow-up with Infectious Disease, the patient’s oral lesions resolved, CD4 count increased above 200 cells/mm3, and HIV RNA titers fell.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Thariat J, Kirova Y, Sio T, et al. Mucosal Kaposi sarcoma, a Rare Cancer Network study. Rare Tumors. 2012;4:E49.

The papules were clinically consistent with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and confirmed with a biopsy from the buccal mucosa. The patient had not been given a diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prior to this presentation. However, the physician confirmed the diagnosis with RNA titers. A CD4 count < 40 cells/mm3 (reference range, 500-1200 cells/mm3) pointed to her progression to AIDS. A chest X-ray revealed multiple nodules; a subsequent biopsy indicated that they were consistent with KS.

KS is a low-grade tumor of vascular origin associated with human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8). It most often presents on the skin as flat to raised pink to deep purple lesions. It can manifest in the oral mucosa, viscera, and other organs, which can portend a worse prognosis because of the risks associated with bleeding and organ perforation.

There are 4 types of KS.

- Classic KS occurs most often in elderly men of Mediterranean descent.

- HIV-associated KS can occur at any time during HIV infection but is more common as CD4 counts fall. HIV-associated KS increased in frequency dramatically in the United States during the early years of the HIV pandemic prior to effective antiretroviral therapy (ART).

- Endemic KS occurs in equatorial Africa, where there is a natural increased transmission rate of HHV-8.

- Iatrogenic KS can occur following treatment with immunosuppressive therapies.

Our patient was admitted to the Infectious Disease Service and given ART. Chemotherapy was discussed (and sometimes is warranted in extensive visceral disease) but the patient and her specialists opted for ART alone. In addition to ART, she was started on daily trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for pneumocystis prophylaxis.

At 6 months’ follow-up with Infectious Disease, the patient’s oral lesions resolved, CD4 count increased above 200 cells/mm3, and HIV RNA titers fell.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

The papules were clinically consistent with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and confirmed with a biopsy from the buccal mucosa. The patient had not been given a diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prior to this presentation. However, the physician confirmed the diagnosis with RNA titers. A CD4 count < 40 cells/mm3 (reference range, 500-1200 cells/mm3) pointed to her progression to AIDS. A chest X-ray revealed multiple nodules; a subsequent biopsy indicated that they were consistent with KS.

KS is a low-grade tumor of vascular origin associated with human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8). It most often presents on the skin as flat to raised pink to deep purple lesions. It can manifest in the oral mucosa, viscera, and other organs, which can portend a worse prognosis because of the risks associated with bleeding and organ perforation.

There are 4 types of KS.

- Classic KS occurs most often in elderly men of Mediterranean descent.

- HIV-associated KS can occur at any time during HIV infection but is more common as CD4 counts fall. HIV-associated KS increased in frequency dramatically in the United States during the early years of the HIV pandemic prior to effective antiretroviral therapy (ART).

- Endemic KS occurs in equatorial Africa, where there is a natural increased transmission rate of HHV-8.

- Iatrogenic KS can occur following treatment with immunosuppressive therapies.

Our patient was admitted to the Infectious Disease Service and given ART. Chemotherapy was discussed (and sometimes is warranted in extensive visceral disease) but the patient and her specialists opted for ART alone. In addition to ART, she was started on daily trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for pneumocystis prophylaxis.

At 6 months’ follow-up with Infectious Disease, the patient’s oral lesions resolved, CD4 count increased above 200 cells/mm3, and HIV RNA titers fell.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Thariat J, Kirova Y, Sio T, et al. Mucosal Kaposi sarcoma, a Rare Cancer Network study. Rare Tumors. 2012;4:E49.

Thariat J, Kirova Y, Sio T, et al. Mucosal Kaposi sarcoma, a Rare Cancer Network study. Rare Tumors. 2012;4:E49.

Itchy bumps on back

This patient had prurigo nodularis (PN). The diagnosis usually is made clinically by the appearance of the lesions and the cycle of severe pruritus and scratching. In this case, the patient had acutely excoriated lesions in addition to more chronic lesions that had become hyperpigmented nodules. The distribution pattern on his back was typical and highlighted the clinical course of PN. There were no lesions present where the patient was unable to scratch; however, lesions were present where he could reach, hence the term Picker’s nodules. Often, these patients have a history of atopic dermatitis, and anxiety may play a role in patients nervously scratching the lesions.

Biopsy is indicated if there is suspicion of bullous pemphigoid or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Pathology of PN shows increased density of nerve fibers in the dermis along with an increased number of T cells, mast cells, and eosinophilic granulocytes. Most patients do not require biopsy unless the diagnosis is in doubt.

Treatment can be difficult due to the severe pruritis and subsequent scratching that appears to prolong the chronic cycle of inflammation. Daily use of nonsedating antihistamines (eg, loratadine, cetirizine) may help reduce pruritus and break the cycle. Sedating antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine) can be used cautiously at bedtime; cotton gloves worn while sleeping may reduce nocturnal scratching and excoriations.

Topical steroids (eg, triamcinolone, betamethasone) can reduce the itching and local inflammation. Emollients can help with associated dyshidrosis and eczema, if present.

Second line therapies include topical calcineurin inhibitors (eg, tacrolimus, pimecrolimus), calcipotriene, and narrow beam UVB therapy.

This patient had done reasonably well with cetirizine and triamcinolone in the past, so treatment was restarted. He was counseled regarding the nature and chronicity of his PN and told that if he could achieve symptom control and stop scratching the lesions, his condition might resolve.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Zeidler C, Yosipovitch G, Ständer S. Prurigo nodularis and its management. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:189-197.

This patient had prurigo nodularis (PN). The diagnosis usually is made clinically by the appearance of the lesions and the cycle of severe pruritus and scratching. In this case, the patient had acutely excoriated lesions in addition to more chronic lesions that had become hyperpigmented nodules. The distribution pattern on his back was typical and highlighted the clinical course of PN. There were no lesions present where the patient was unable to scratch; however, lesions were present where he could reach, hence the term Picker’s nodules. Often, these patients have a history of atopic dermatitis, and anxiety may play a role in patients nervously scratching the lesions.

Biopsy is indicated if there is suspicion of bullous pemphigoid or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Pathology of PN shows increased density of nerve fibers in the dermis along with an increased number of T cells, mast cells, and eosinophilic granulocytes. Most patients do not require biopsy unless the diagnosis is in doubt.

Treatment can be difficult due to the severe pruritis and subsequent scratching that appears to prolong the chronic cycle of inflammation. Daily use of nonsedating antihistamines (eg, loratadine, cetirizine) may help reduce pruritus and break the cycle. Sedating antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine) can be used cautiously at bedtime; cotton gloves worn while sleeping may reduce nocturnal scratching and excoriations.

Topical steroids (eg, triamcinolone, betamethasone) can reduce the itching and local inflammation. Emollients can help with associated dyshidrosis and eczema, if present.

Second line therapies include topical calcineurin inhibitors (eg, tacrolimus, pimecrolimus), calcipotriene, and narrow beam UVB therapy.